UNIT IV OBJECTORIENTATION CONCURRENCY AND EVENT HANDLING 1

UNIT IV OBJECTORIENTATION, CONCURRENCY, AND EVENT HANDLING 1 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Object-Oriented Programming • Think from the perspectives of data (“things”) and their interactions with the external world – Object • Data • Method: interface and message – Class • The need to handle similar “things” – American, French, Chinese, Korean abstraction – Chinese: northerners, southerners inheritance – Dynamic binding, polymorphism 2 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

What OOP Allows You? • You analyze the objects with which you are working (attributes and tasks on them) • You pass messages to objects, requesting them to take action • The same message works differently when applied to the various objects • A method can work with different types of data, without the need for separate method names • Objects can inherit traits of previously created objects • Information can be hidden better 3 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Abstraction • Two types of abstractions: – Process abstraction: subprograms – Data abstraction • Floating-point data type as data abstraction – The programming language will provide (1) a way of creating variables of the floating-point data type, and (2) a set of operators for manipulating variables – Abstract away and hide the information of how the floating-point number is presented and stored • Need to allow programmers to do the same – Allow them to specify the data and the operators 4 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

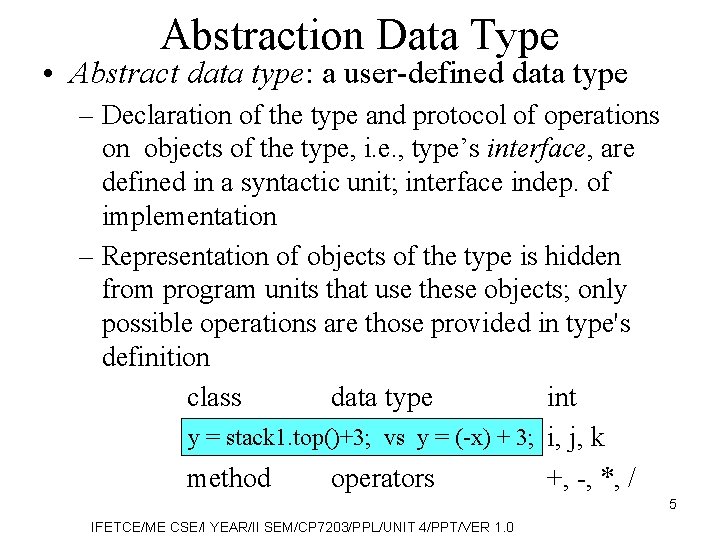

Abstraction Data Type • Abstract data type: a user-defined data type – Declaration of the type and protocol of operations on objects of the type, i. e. , type’s interface, are defined in a syntactic unit; interface indep. of implementation – Representation of objects of the type is hidden from program units that use these objects; only possible operations are those provided in type's definition class data type int y = stack 1. top()+3; vs y = (-x) + 3; i, j, k object variable method operators +, -, *, / 5 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Advantages of Data Abstraction • Advantage of having interface independent of object representation or implementation of operations: – Program organization, modifiability (everything associated with a data structure is together), separate compilation • Advantage of 2 nd condition (info. hiding) – Reliability: By hiding data representations, user code cannot directly access objects of the type or depend on the representation, allowing the representation to be changed without affecting user code 6 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Language Requirements for ADTs • A syntactic unit to encapsulate type definition • A method of making type names and subprogram headers visible to clients, while hiding actual definitions • Some primitive operations that are built into the language processor • Example: an abstract data type for stack – create(stack), destroy(stack), empty(stack), push(stack, element), pop(stack), top(stack) – Stack may be implemented with array, linked list, . . . 7 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Abstract Data Types in C++ • Based on C struct type and Simula 67 classes • The class is the encapsulation device – All of the class instances of a class share a single copy of the member functions – Each instance has own copy of class data members – Instances can be static, stack dynamic, heap dynamic • Information hiding – Private clause for hidden entities – Public clause for interface entities – Protected clause for inheritance (Chapter 12) 8 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

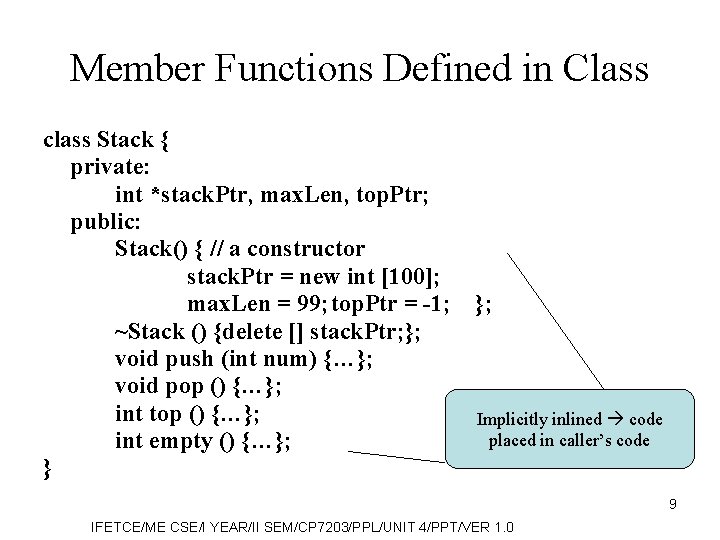

Member Functions Defined in Class class Stack { private: int *stack. Ptr, max. Len, top. Ptr; public: Stack() { // a constructor stack. Ptr = new int [100]; max. Len = 99; top. Ptr = -1; }; ~Stack () {delete [] stack. Ptr; }; void push (int num) {…}; void pop () {…}; int top () {…}; Implicitly inlined code placed in caller’s code int empty () {…}; } 9 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

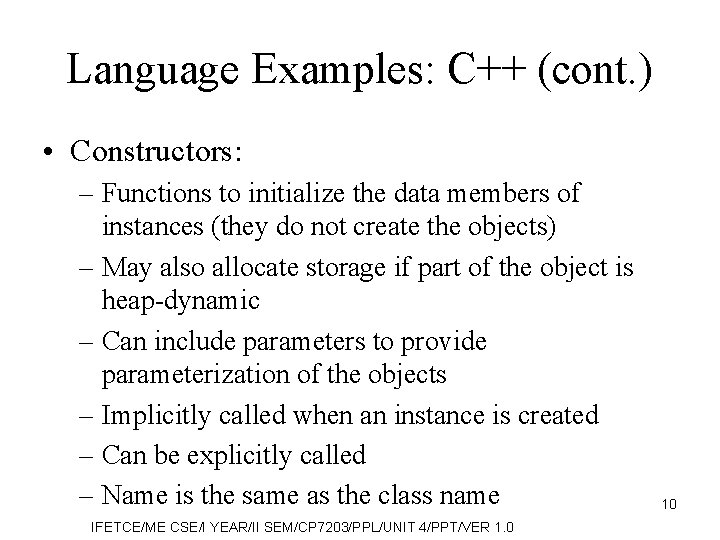

Language Examples: C++ (cont. ) • Constructors: – Functions to initialize the data members of instances (they do not create the objects) – May also allocate storage if part of the object is heap-dynamic – Can include parameters to provide parameterization of the objects – Implicitly called when an instance is created – Can be explicitly called – Name is the same as the class name IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0 10

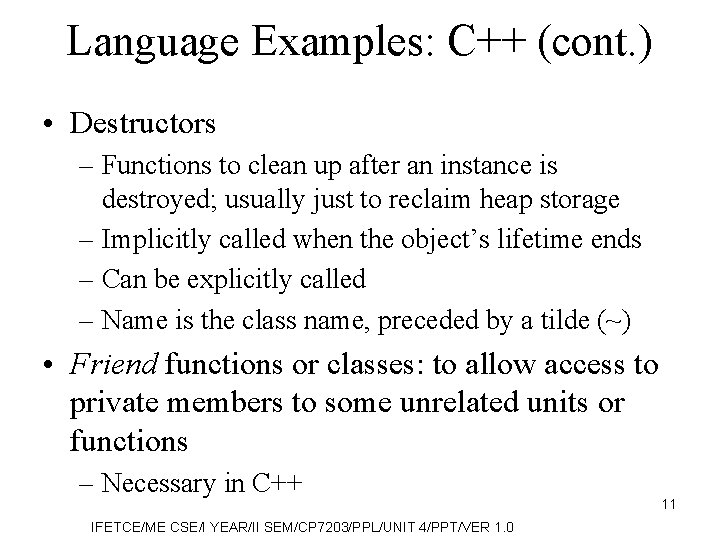

Language Examples: C++ (cont. ) • Destructors – Functions to clean up after an instance is destroyed; usually just to reclaim heap storage – Implicitly called when the object’s lifetime ends – Can be explicitly called – Name is the class name, preceded by a tilde (~) • Friend functions or classes: to allow access to private members to some unrelated units or functions – Necessary in C++ IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0 11

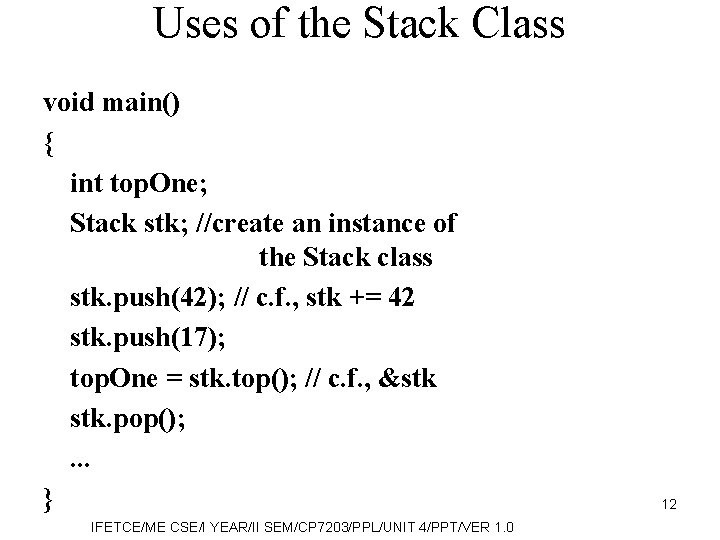

Uses of the Stack Class void main() { int top. One; Stack stk; //create an instance of the Stack class stk. push(42); // c. f. , stk += 42 stk. push(17); top. One = stk. top(); // c. f. , &stk stk. pop(); . . . } IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0 12

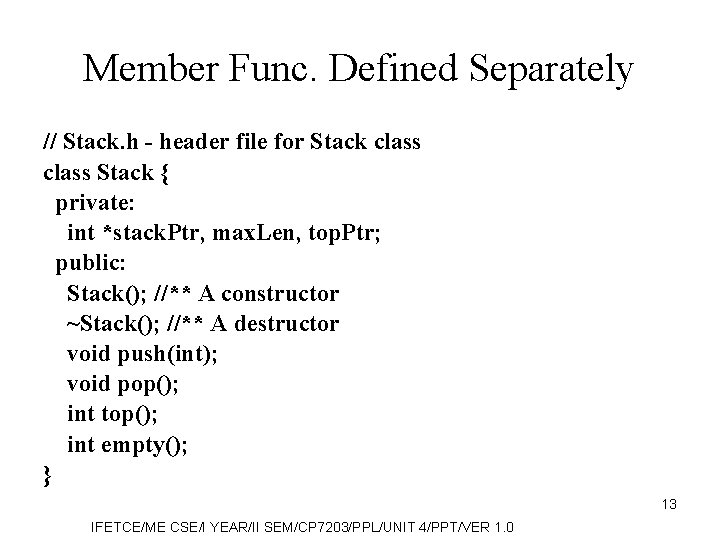

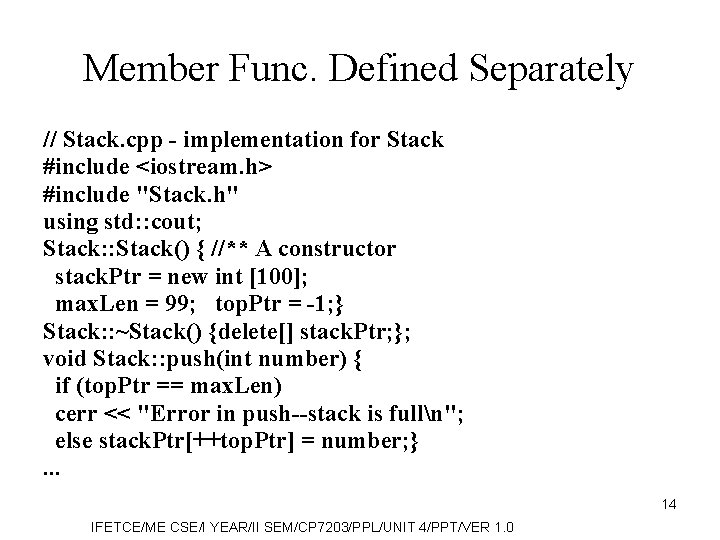

Member Func. Defined Separately // Stack. h - header file for Stack class Stack { private: int *stack. Ptr, max. Len, top. Ptr; public: Stack(); //** A constructor ~Stack(); //** A destructor void push(int); void pop(); int top(); int empty(); } 13 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Member Func. Defined Separately // Stack. cpp - implementation for Stack #include <iostream. h> #include "Stack. h" using std: : cout; Stack: : Stack() { //** A constructor stack. Ptr = new int [100]; max. Len = 99; top. Ptr = -1; } Stack: : ~Stack() {delete[] stack. Ptr; }; void Stack: : push(int number) { if (top. Ptr == max. Len) cerr << "Error in push--stack is fulln"; else stack. Ptr[++top. Ptr] = number; }. . . 14 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

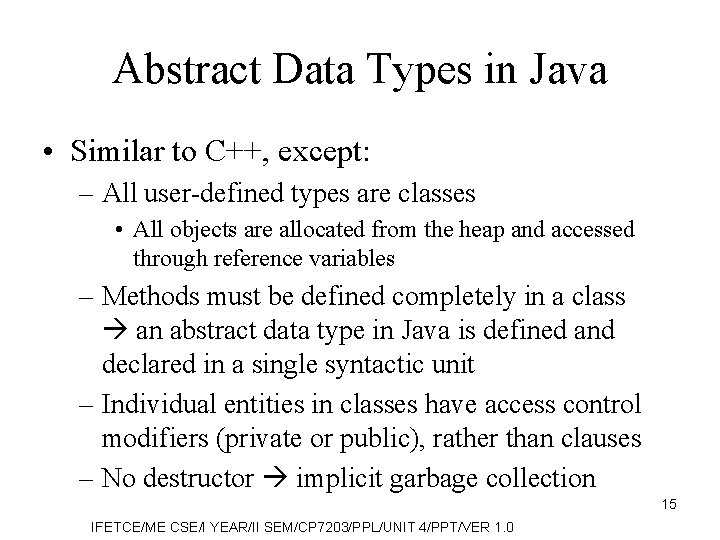

Abstract Data Types in Java • Similar to C++, except: – All user-defined types are classes • All objects are allocated from the heap and accessed through reference variables – Methods must be defined completely in a class an abstract data type in Java is defined and declared in a single syntactic unit – Individual entities in classes have access control modifiers (private or public), rather than clauses – No destructor implicit garbage collection 15 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

![An Example in Java class Stack. Class { private int [] stack. Ref; private An Example in Java class Stack. Class { private int [] stack. Ref; private](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/69038527f3ec05df3defc020b77e8189/image-16.jpg)

An Example in Java class Stack. Class { private int [] stack. Ref; private int max. Len, top. Index; public Stack. Class() { // a constructor stack. Ref = new int [100]; max. Len = 99; top. Ptr = -1; }; public void push (int num) {…}; public void pop () {…}; public int top () {…}; public boolean empty () {…}; } IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0 16

![An Example in Java public class Tst. Stack { public static void main(String[] args) An Example in Java public class Tst. Stack { public static void main(String[] args)](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/69038527f3ec05df3defc020b77e8189/image-17.jpg)

An Example in Java public class Tst. Stack { public static void main(String[] args) { Stack. Class my. Stack = new Stack. Class(); my. Stack. push(42); my. Stack. push(29); System. out. println(“: “+my. Stack. top()); my. Stack. pop(); my. Stack. empty(); } } 17 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

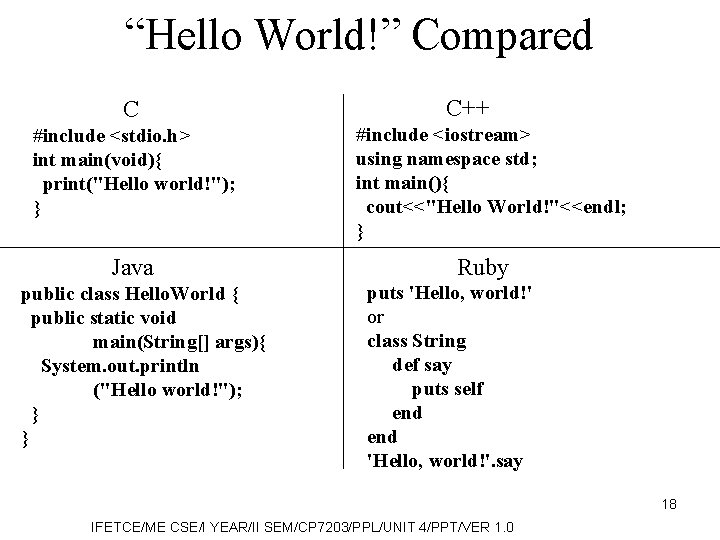

“Hello World!” Compared C #include <stdio. h> int main(void){ print("Hello world!"); } Java public class Hello. World { public static void main(String[] args){ System. out. println ("Hello world!"); } } C++ #include <iostream> using namespace std; int main(){ cout<<"Hello World!"<<endl; } Ruby puts 'Hello, world!' or class String def say puts self end 'Hello, world!'. say 18 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

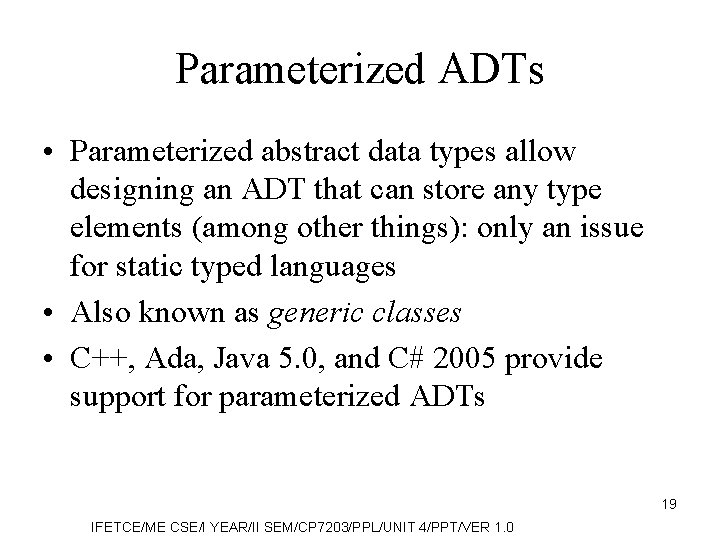

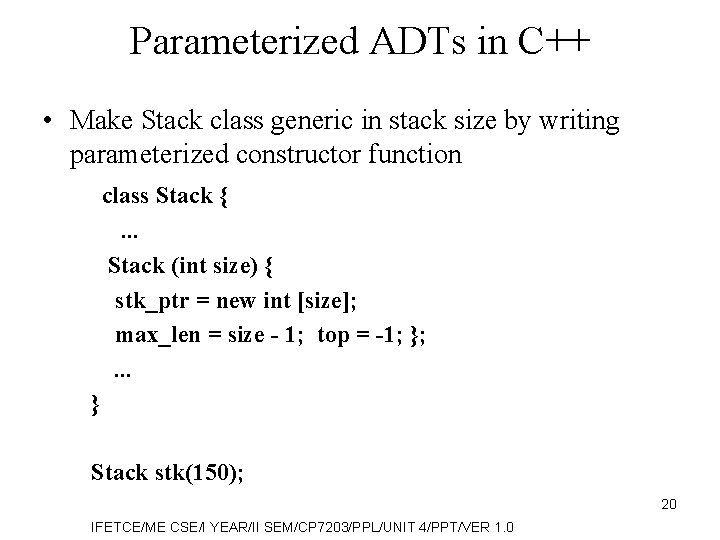

Parameterized ADTs • Parameterized abstract data types allow designing an ADT that can store any type elements (among other things): only an issue for static typed languages • Also known as generic classes • C++, Ada, Java 5. 0, and C# 2005 provide support for parameterized ADTs 19 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Parameterized ADTs in C++ • Make Stack class generic in stack size by writing parameterized constructor function class Stack {. . . Stack (int size) { stk_ptr = new int [size]; max_len = size - 1; top = -1; }; . . . } Stack stk(150); 20 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

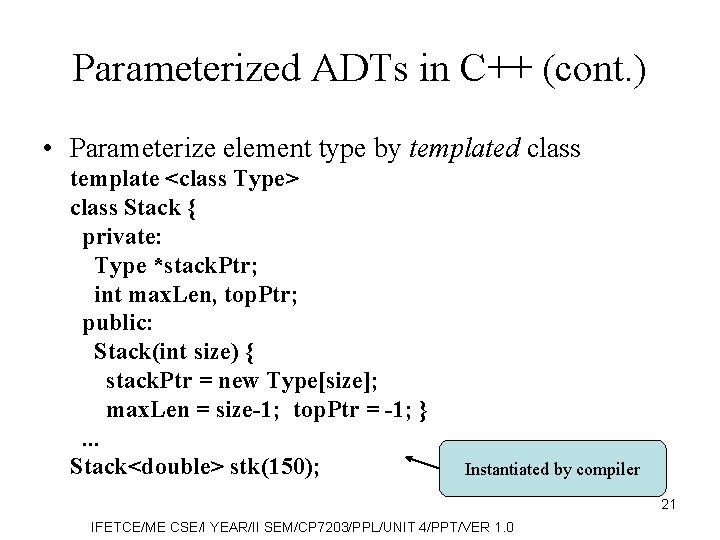

Parameterized ADTs in C++ (cont. ) • Parameterize element type by templated class template <class Type> class Stack { private: Type *stack. Ptr; int max. Len, top. Ptr; public: Stack(int size) { stack. Ptr = new Type[size]; max. Len = size-1; top. Ptr = -1; }. . . Stack<double> stk(150); Instantiated by compiler 21 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Generalized Encapsulation • Enclosure for an abstract data type defines a SINGLE data type and its operations • How about defining a more generalized encapsulation construct that can define any number of entries/types, any of which can be selectively specified to be visible outside the enclosing unit – Abstract data type is thus a special case 22 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Encapsulation Constructs • Large programs have two special needs: – Some means of organization, other than simply division into subprograms – Some means of partial compilation (compilation units that are smaller than the whole program) • Obvious solution: a grouping of logically related code and data into a unit that can be separately compiled (compilation units) • Such collections are called encapsulation – Example: libraries 23 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Means of Encapsulation: Nested Subprograms • Organizing programs by nesting subprogram definitions inside the logically larger subprograms that use them • Nested subprograms are supported in Ada, Fortran 95, Python, and Ruby 24 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Encapsulation in C • Files containing one or more subprograms can be independently compiled • The interface is placed in a header file • Problem: – The linker does not check types between a header and associated implementation • #include preprocessor specification: – Used to include header files in client programs to reference to compiled version of implementation file, which is linked as libraries 25 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Encapsulation in C++ • Can define header and code files, similar to those of C • Or, classes can be used for encapsulation – The class header file has only the prototypes of the member functions – The member definitions are defined in a separate file Separate interface from implementation • Friends provide a way to grant access to private members of a class – Example: vector object multiplied by matrix object 26 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

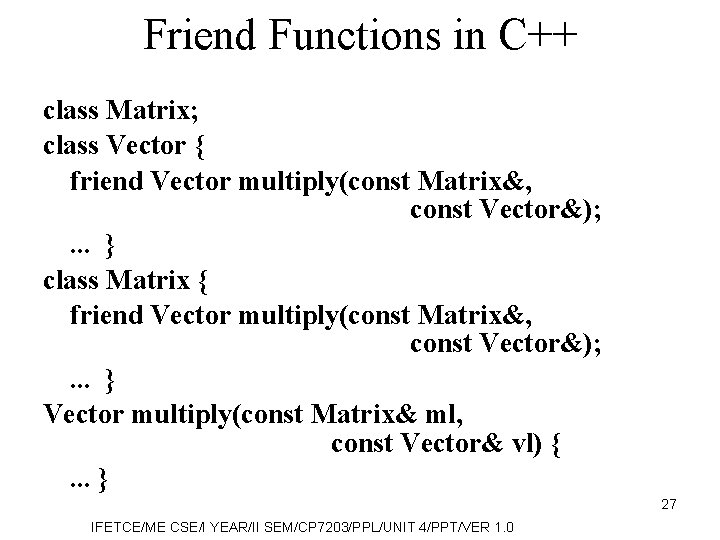

Friend Functions in C++ class Matrix; class Vector { friend Vector multiply(const Matrix&, const Vector&); . . . } class Matrix { friend Vector multiply(const Matrix&, const Vector&); . . . } Vector multiply(const Matrix& ml, const Vector& vl) {. . . } 27 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Naming Encapsulations • Encapsulation discussed so far is to provide a way to organize programs into logical units for separate compilation • On the other hand, large programs define many global names; need a way to avoid name conflicts in libraries and client programs developed by different programmers • A naming encapsulation is used to create a new scope for names 28 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Naming Encapsulations (cont. ) • C++ namespaces – Can place each library in its own namespace and qualify names used outside with the namespace My. Stack {. . . // stack declarations } – Can be referenced in three ways: My. Stack: : top. Ptr using My. Stack: : top. Ptr; p = top. Ptr; using namespace My. Stack; p = top. Ptr; – C# also includes namespaces 29 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Naming Encapsulations (cont. ) • Java Packages – Packages can contain more than one class definition; classes in a package are partial friends – Clients of a package can use fully qualified name, e. g. , my. Stack. top. Ptr, or use import declaration, e. g. , import my. Stack. *; • Ada Packages – Packages are defined in hierarchies which correspond to file hierarchies – Visibility from a program unit is gained with the with clause 30 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

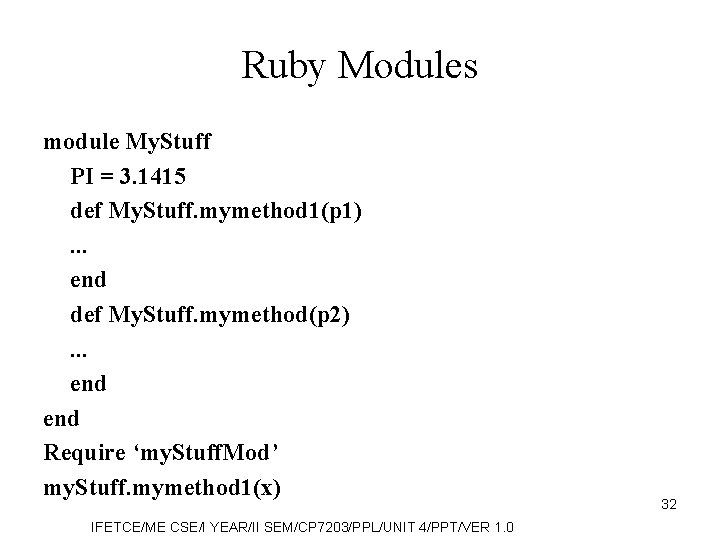

Naming Encapsulations (cont. ) • Ruby classes are name encapsulations, but Ruby also has modules • Module: – Encapsulate libraries of related constants and methods, whose names in a separate namespace – Unlike classes cannot be instantiated or subclassed, and they cannot define variables – Methods defined in a module must include the module’s name – Access to the contents of a module is requested with the require method 31 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Ruby Modules module My. Stuff PI = 3. 1415 def My. Stuff. mymethod 1(p 1). . . end def My. Stuff. mymethod(p 2). . . end Require ‘my. Stuff. Mod’ my. Stuff. mymethod 1(x) IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0 32

Support for Object-Oriented Programming 33 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Software Productivity • Pressure on software productivity vs. continual reduction in hardware cost • Productivity increases can come from reuse • Abstract data types (ADTs) for reuse? • Mere ADTs are not enough – ADTs are difficult to reuse—always need changes for new uses, e. g. , circle, square, rectangle, . . . – All ADTs are independent and at the same level hard to organize program to match problem space • More, in addition to ADTs, are needed 34 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

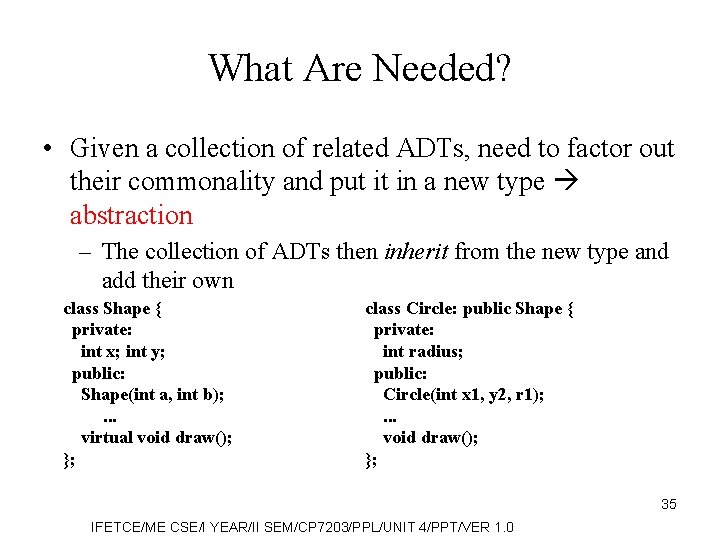

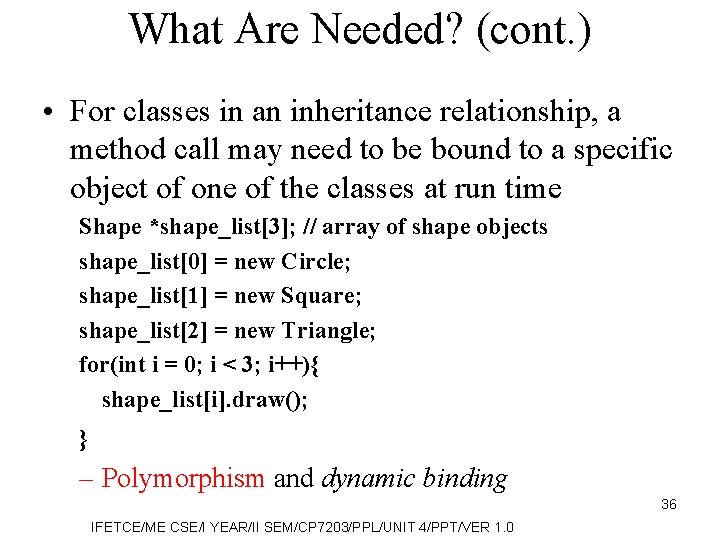

What Are Needed? • Given a collection of related ADTs, need to factor out their commonality and put it in a new type abstraction – The collection of ADTs then inherit from the new type and add their own class Shape { private: int x; int y; public: Shape(int a, int b); . . . virtual void draw(); }; class Circle: public Shape { private: int radius; public: Circle(int x 1, y 2, r 1); . . . void draw(); }; 35 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

What Are Needed? (cont. ) • For classes in an inheritance relationship, a method call may need to be bound to a specific object of one of the classes at run time Shape *shape_list[3]; // array of shape objects shape_list[0] = new Circle; shape_list[1] = new Square; shape_list[2] = new Triangle; for(int i = 0; i < 3; i++){ shape_list[i]. draw(); } – Polymorphism and dynamic binding 36 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Object-Oriented Programming • An object-oriented language must provide supports for three key features: – Abstract data types – Inheritance: the central theme in OOP and languages that support it – Polymorphism and dynamic binding • What does it mean in a pure OO program, where x, y, and 3 are objects? y = x + 3; 37 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Object-Oriented Concepts • ADTs are usually called classes, e. g. Shape • Class instances are called objects, e. g. shape_list[0] • A class that inherits is a derived class or a subclass, e. g. Circle, Square • The class from which another class inherits is a parent class or superclass, e. g. Shape • Subprograms that define operations on objects are called methods, e. g. draw() 38 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

![Object-Oriented Concepts (cont. ) • Calls to methods are called messages, e. g. shape_list[i]. Object-Oriented Concepts (cont. ) • Calls to methods are called messages, e. g. shape_list[i].](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/69038527f3ec05df3defc020b77e8189/image-39.jpg)

Object-Oriented Concepts (cont. ) • Calls to methods are called messages, e. g. shape_list[i]. draw(); • Object that made the method call is the client • The entire collection of methods of an object is called its message protocol or message interface • Messages have two parts--a method name and the destination object • In the simplest case, a class inherits all of the entities of its parent 39 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Inheritance • Allows new classes defined in terms of existing ones, i. e. , by inheriting common parts • Can be complicated by access controls to encapsulated entities – A class can hide entities from its subclasses (private) – A class can hide entities from its clients – A class can also hide entities for its clients while allowing its subclasses to see them • A class can modify an inherited method – The new one overrides the inherited one – The method in the parent is overridden IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0 40

Inheritance (cont. ) • There are two kinds of variables in a class: – Class variables - one/class – Instance variables - one/object, object state • There are two kinds of methods in a class: – Class methods – accept messages to the class – Instance methods – accept messages to objects • Single vs. multiple inheritance • One disadvantage of inheritance for reuse: – Creates interdependencies among classes that complicate maintenance IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0 41

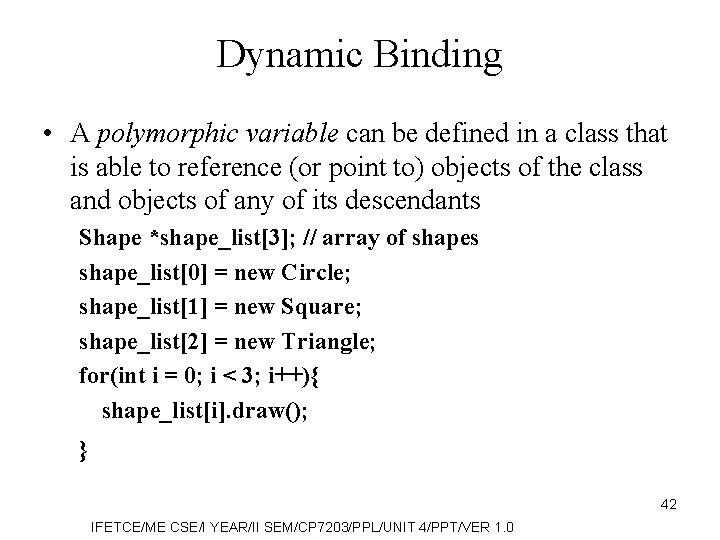

Dynamic Binding • A polymorphic variable can be defined in a class that is able to reference (or point to) objects of the class and objects of any of its descendants Shape *shape_list[3]; // array of shapes shape_list[0] = new Circle; shape_list[1] = new Square; shape_list[2] = new Triangle; for(int i = 0; i < 3; i++){ shape_list[i]. draw(); } 42 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Dynamic Binding • When a class hierarchy includes classes that override methods and such methods are called through a polymorphic variable, the binding to the correct method will be dynamic, e. g. , shape_list[i]. draw(); • Allows software systems to be more easily extended during both development and maintenance, e. g. , new shape classes are defined later 43 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

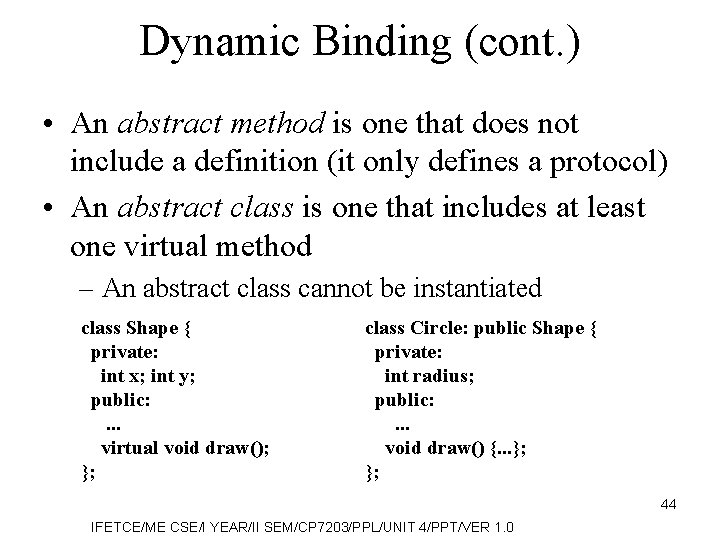

Dynamic Binding (cont. ) • An abstract method is one that does not include a definition (it only defines a protocol) • An abstract class is one that includes at least one virtual method – An abstract class cannot be instantiated class Shape { private: int x; int y; public: . . . virtual void draw(); }; class Circle: public Shape { private: int radius; public: . . . void draw() {. . . }; }; 44 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Design Issues for OOP Languages • • The exclusivity of objects Are subclasses subtypes? Type checking and polymorphism Single and multiple inheritance Object allocation and deallocation Dynamic and static binding Nested classes Initialization of objects 45 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

The Exclusivity of Objects • Option 1: Everything is an object – Advantage: elegance and purity – Disadvantage: slow operations on simple objects • Option 2: Add objects to existing typing system – Advantage: fast operations on simple objects – Disadvantage: confusing typing (2 kinds of entities) • Option 3: Imperative-style typing system for primitives and everything else objects – Advantage: fast operations on simple objects and a relatively small typing system – Disadvantage: still confusing by two type systems IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0 46

Are Subclasses Subtypes? • Does an “is-a” relationship hold between a parent class object and an object of subclass? – If a derived class is-a parent class, then objects of derived class behave same as parent class object subtype small_Int is Integer range 0. . 100; – Every small_Int variable can be used anywhere Integer variables can be used • A derived class is a subtype if methods of subclass that override parent class are type compatible with the overridden parent methods – A call to overriding method can replace any call to overridden method without type errors 47 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Type Checking and Polymorphism • Polymorphism may require dynamic type checking of parameters and the return value – Dynamic type checking is costly and delays error detection • If overriding methods are restricted to having the same parameter types and return type, the checking can be static 48 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Single and Multiple Inheritance • Multiple inheritance allows a new class to inherit from two or more classes • Disadvantages of multiple inheritance: – Language and implementation complexity: if class C needs to reference both draw() methods in parents A and B, how to do? If A and B in turn inherit from Z, which version of Z entry in A or B should be ref. ? – Potential inefficiency: dynamic binding costs more with multiple inheritance (but not much) • Advantage: – Sometimes it is quite convenient and valuable 49 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Object Allocation and Deallocation • From where are objects allocated? – If behave like ADTs, can be allocated from anywhere • Allocated from the run-time stack • Explicitly created on the heap (via new) – If they are all heap-dynamic, references can be uniform thru a pointer or reference variable • Simplifies assignment: dereferencing can be implicit – If objects are stack dynamic, assignment of subclass B’s object to superclass A’s object is value copy, but what if B is larger in space? • Is deallocation explicit or implicit? 50 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Dynamic and Static Binding • Should all binding of messages to methods be dynamic? – If none are, you lose the advantages of dynamic binding – If all are, it is inefficient • Alternative: allow the user to specify 51 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Nested Classes • If a new class is needed by only one class, no reason to define it to be seen by other classes – Can the new class be nested inside the class that uses it? – In some cases, the new class is nested inside a subprogram rather than directly in another class • Other issues: – Which facilities of the nesting class should be visible to the nested class and vice versa 52 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Initialization of Objects • Are objects initialized to values when they are created? – Implicit or explicit initialization • How are parent class members initialized when a subclass object is created? 53 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Inheritance in C++ • Inheritance – A class need not be the subclass of any class – Access controls for members are • Private: accessible only from within other members of the same class or from their friends. • Protected: accessible from members of the same class and from their friends, but also from members of their derived classes. • Public: accessible from anywhere that object is visible • Multiple inheritance is supported – If two inherited members with same name, they can both be referenced using scope resolution operator 54 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Inheritance in C++ (cont. ) • In addition, the subclassing process can be declared with access controls (private or public), which define potential changes in access by subclasses – Private derivation: inherited public and protected members are private in the subclasses members in derived class cannot access to any member of the parent class – Public derivation: public and protected members are also public and protected in subclasses 55 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Inheritance Example in C++ class base_class { private: int a; float x; protected: int b; float y; public: int c; float z; }; class subclass_1 : public base_class {…}; // b, y protected; c, z public class subclass_2 : private base_class {…}; // b, y, c, z private; no access by derived IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0 56

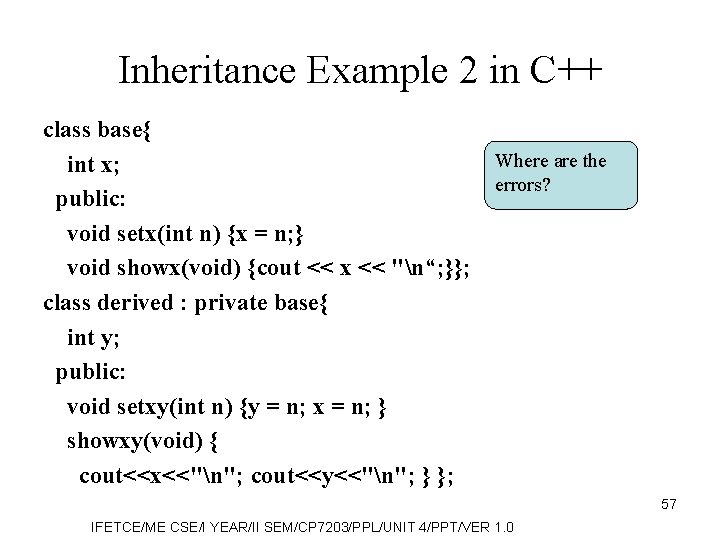

Inheritance Example 2 in C++ class base{ Where are the int x; errors? public: void setx(int n) {x = n; } void showx(void) {cout << x << "n“; }}; class derived : private base{ int y; public: void setxy(int n) {y = n; x = n; } showxy(void) { cout<<x<<"n"; cout<<y<<"n"; } }; 57 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

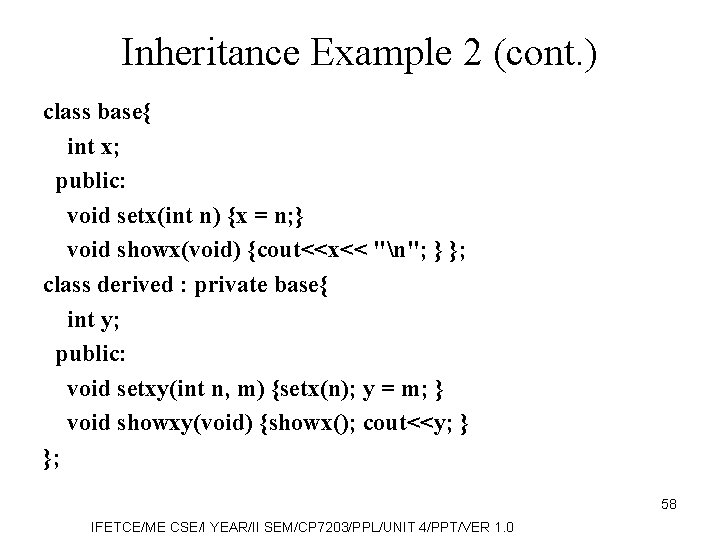

Inheritance Example 2 (cont. ) class base{ int x; public: void setx(int n) {x = n; } void showx(void) {cout<<x<< "n"; } }; class derived : private base{ int y; public: void setxy(int n, m) {setx(n); y = m; } void showxy(void) {showx(); cout<<y; } }; 58 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

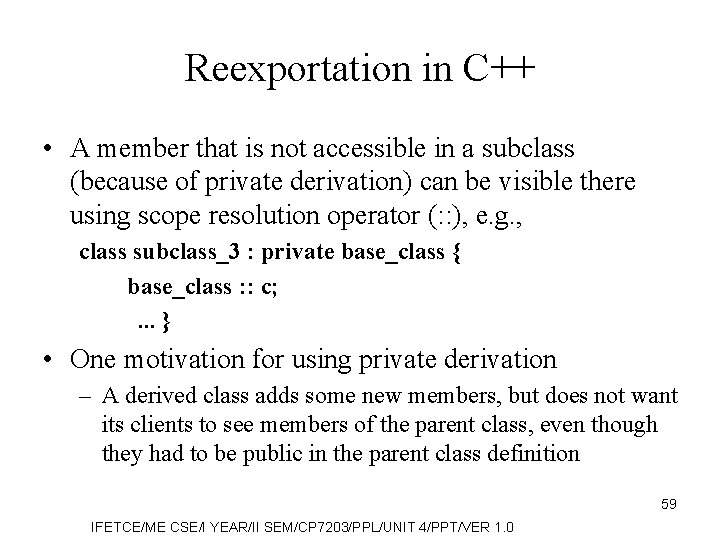

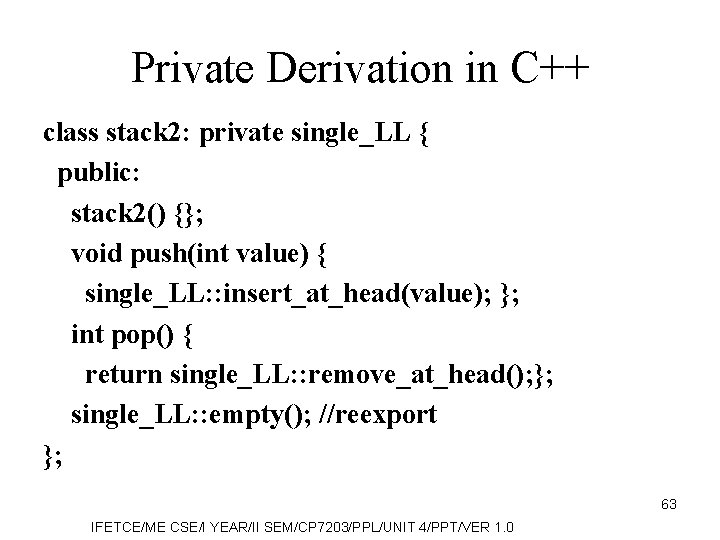

Reexportation in C++ • A member that is not accessible in a subclass (because of private derivation) can be visible there using scope resolution operator (: : ), e. g. , class subclass_3 : private base_class { base_class : : c; . . . } • One motivation for using private derivation – A derived class adds some new members, but does not want its clients to see members of the parent class, even though they had to be public in the parent class definition 59 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

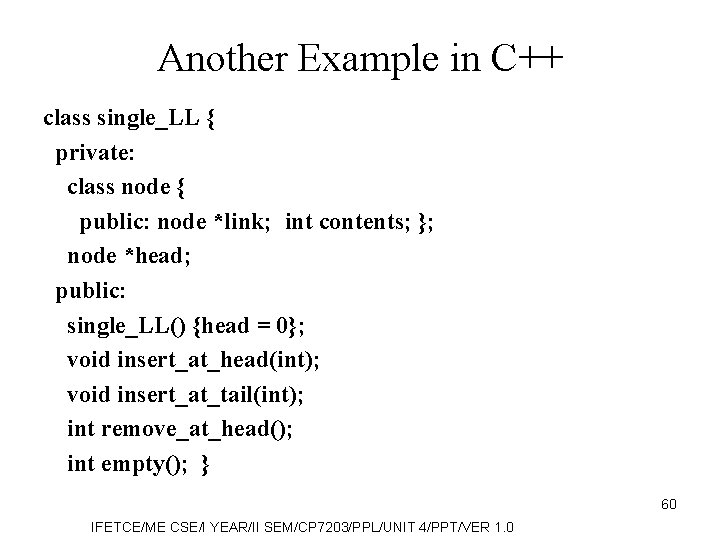

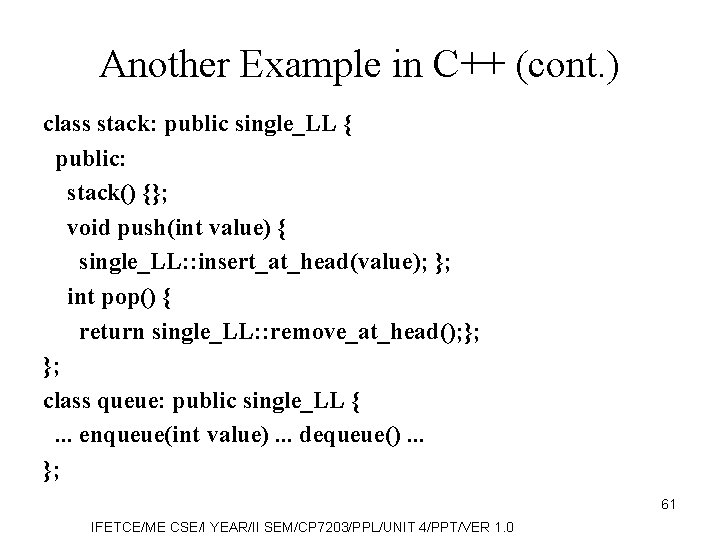

Another Example in C++ class single_LL { private: class node { public: node *link; int contents; }; node *head; public: single_LL() {head = 0}; void insert_at_head(int); void insert_at_tail(int); int remove_at_head(); int empty(); } 60 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Another Example in C++ (cont. ) class stack: public single_LL { public: stack() {}; void push(int value) { single_LL: : insert_at_head(value); }; int pop() { return single_LL: : remove_at_head(); }; }; class queue: public single_LL {. . . enqueue(int value). . . dequeue(). . . }; 61 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

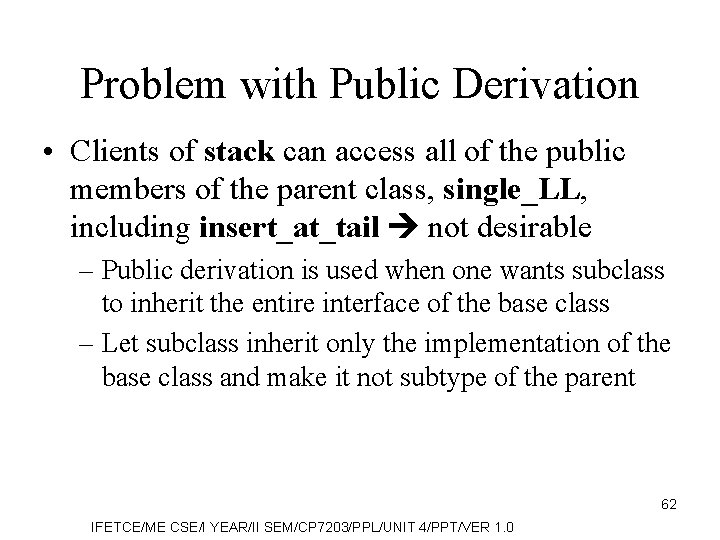

Problem with Public Derivation • Clients of stack can access all of the public members of the parent class, single_LL, including insert_at_tail not desirable – Public derivation is used when one wants subclass to inherit the entire interface of the base class – Let subclass inherit only the implementation of the base class and make it not subtype of the parent 62 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

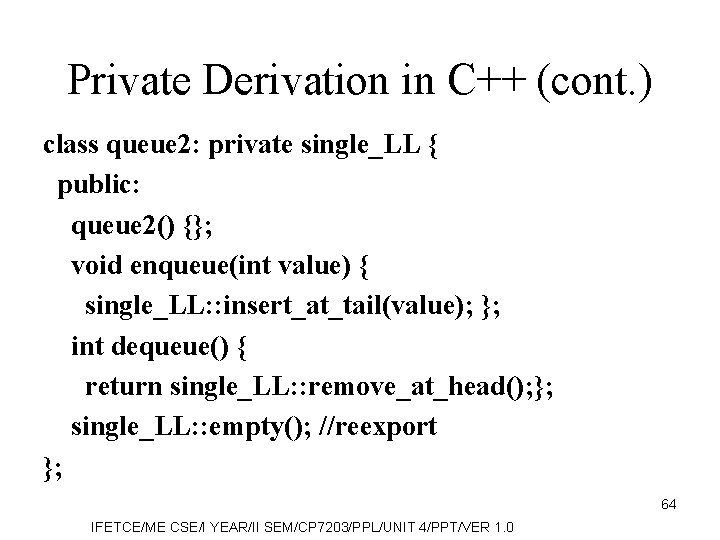

Private Derivation in C++ class stack 2: private single_LL { public: stack 2() {}; void push(int value) { single_LL: : insert_at_head(value); }; int pop() { return single_LL: : remove_at_head(); }; single_LL: : empty(); //reexport }; 63 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Private Derivation in C++ (cont. ) class queue 2: private single_LL { public: queue 2() {}; void enqueue(int value) { single_LL: : insert_at_tail(value); }; int dequeue() { return single_LL: : remove_at_head(); }; single_LL: : empty(); //reexport }; 64 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

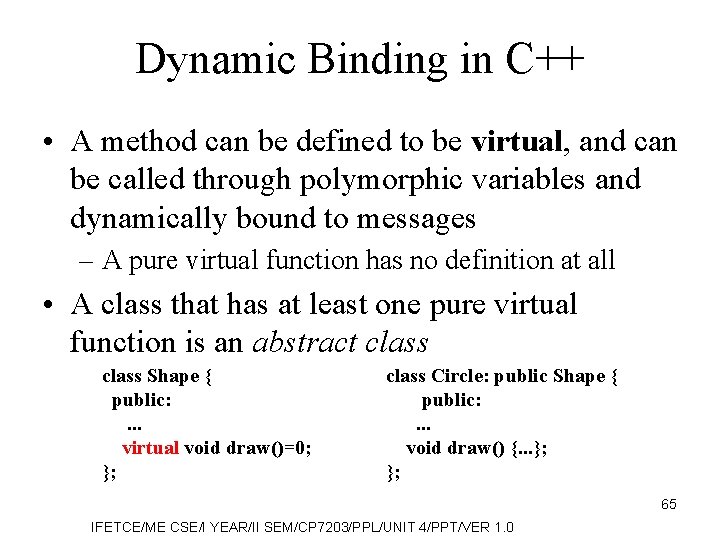

Dynamic Binding in C++ • A method can be defined to be virtual, and can be called through polymorphic variables and dynamically bound to messages – A pure virtual function has no definition at all • A class that has at least one pure virtual function is an abstract class Shape { public: . . . virtual void draw()=0; }; class Circle: public Shape { public: . . . void draw() {. . . }; }; 65 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

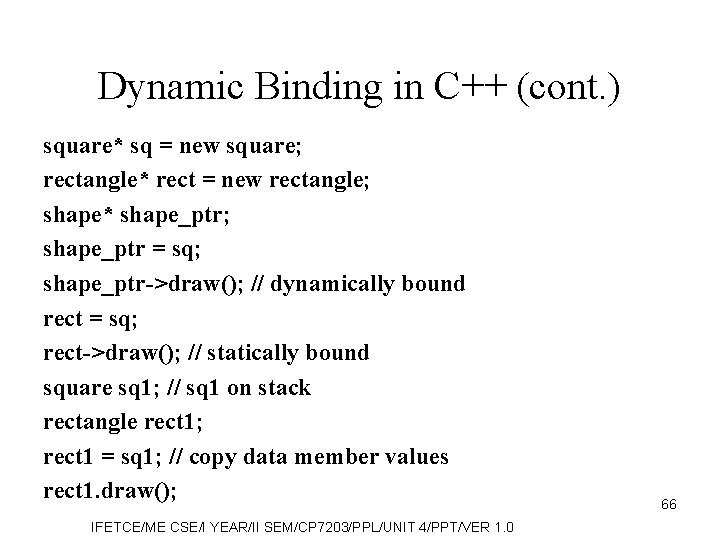

Dynamic Binding in C++ (cont. ) square* sq = new square; rectangle* rect = new rectangle; shape* shape_ptr; shape_ptr = sq; shape_ptr->draw(); // dynamically bound rect = sq; rect->draw(); // statically bound square sq 1; // sq 1 on stack rectangle rect 1; rect 1 = sq 1; // copy data member values rect 1. draw(); IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0 66

Support for OOP in C++ • Evaluation – C++ provides extensive access controls (unlike Smalltalk) – C++ provides multiple inheritance – Programmer must decide at design time which methods will be statically or dynamically bound • Static binding is faster! – Smalltalk type checking is dynamic (flexible, but somewhat unsafe and is ~10 times slower due to interpretation and dynamic binding IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0 67

Support for OOP in Java • Focus on the differences from C++ • General characteristics – All data are objects except the primitive types – All primitive types have wrapper classes to store data value, e. g. , my. Array. add(new Integer(10)); – All classes are descendant of the root class, Object – All objects are heap-dynamic, are referenced through reference variables, and most are allocated with new – No destructor, but a finalize method is implicitly called when garbage collector is about to reclaim the storage occupied by the object, e. g. , to clean locks 68 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Inheritance in Java • Single inheritance only, but interface provides some flavor of multiple inheritance • An interface like a class, but can include only method declarations and named constants, e. g. , public interface Comparable <T> { public int compared. To (T b); } • A class can inherit from another class and “implement” an interface for multiple inheritance • A method can have an interface as formal parameter, that accepts any class that implements the interface a kind of polymorphism • Methods can be final (cannot be overridden) 69 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Dynamic Binding in Java • In Java, all messages are dynamically bound to methods, unless the method is final (i. e. , it cannot be overridden, and thus dynamic binding serves no purpose) • Static binding is also used if the method is static or private, both of which disallow overriding 70 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Nested Classes in Java • Several varieties of nested classes – All are hidden from all classes in their package, except for the nesting class • Nonstatic classes nested directly are called innerclasses – An innerclass can access members of its nesting class, but not a static nested class • Nested classes can be anonymous • A local nested class is defined in a method of its nesting class no access specifier is used 71 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Evaluation of Java • Design decisions to support OOP are similar to C++ • No support for procedural programming • No parentless classes • Dynamic binding is used as “normal” way to bind method calls to method definitions • Uses interfaces to provide a simple form of support for multiple inheritance 72 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Support for OOP in Ruby • General characteristics – Everything is an object and all computation is through message passing – Class definitions are executable, allowing secondary definitions to add members to existing definitions – Method definitions are also executable – All variables are type-less references to objects – Access control is different for data and methods • It is private for all data and cannot be changed • Methods can be either public, private, or protected • Method access is checked at runtime 73 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Implementing OO Constructs • Most OO constructs can be implemented easily by compilers – Abstract data types scope rules – Inheritance • Two interesting and challenging parts: – Storage structures for instance variables – Dynamic binding of messages to methods 74 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

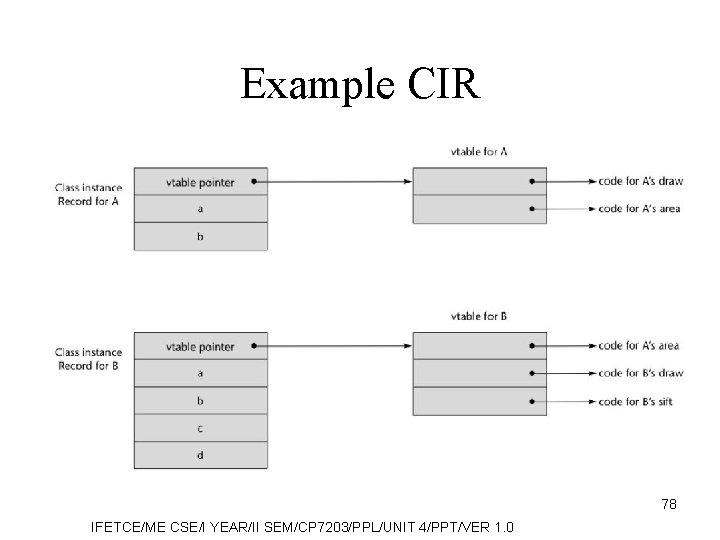

Instance Data Storage • Class instance records (CIRs) store the state of an object – Static (built at compile time and used as a template for the creation of data of class instances) – Every class has its own CIR • CRI for the subclass is a copy of that of the parent class, with entries for the new instance variables added at the end • Because CIR is static, access to all instance variables is done by constant offsets from beginning of CIR 75 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Dynamic Binding of Methods Calls • Methods in a class that are statically bound need not be involved in CIR; methods that are dynamically bound must have entries in the CIR – Calls to dynamically bound methods can be connected to the corresponding code thru a pointer in the CIR – Storage structure for the list of dynamically bound methods is called virtual method tables (vtable) – Method calls can be represented as offsets from the beginning of the vtable 76 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

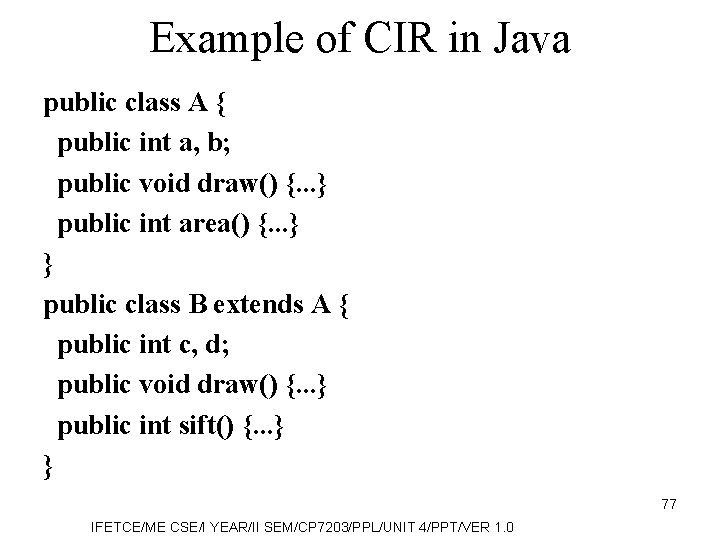

Example of CIR in Java public class A { public int a, b; public void draw() {. . . } public int area() {. . . } } public class B extends A { public int c, d; public void draw() {. . . } public int sift() {. . . } } 77 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Example CIR 78 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Concurrency • Parallel architecture and programming • Language supports for concurrency – Controlling concurrent tasks – Sharing data – Synchronizing tasks 79 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

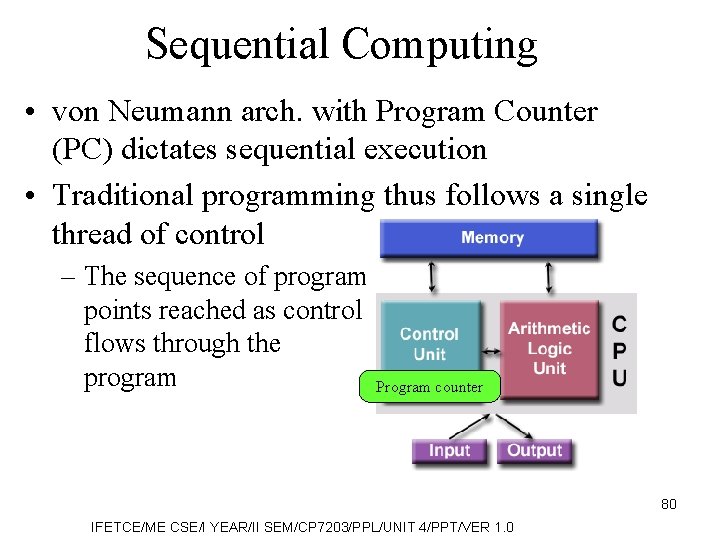

Sequential Computing • von Neumann arch. with Program Counter (PC) dictates sequential execution • Traditional programming thus follows a single thread of control – The sequence of program points reached as control flows through the program Program counter 80 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Sequential Programming Dominates • Sequential programming has dominated throughout computing history • Why? – Why is there no need to change programming style? 81 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

2 Factors Help to Maintain Perf. • IC technology: ever shrinking feature size – Moore’s law, faster switching, more functionalities • Architectural innovations to remove bottlenecks in von Neumann architecture – Memory hierarchy for reducing memory latency: registers, caches, scratchpad memory – Hide or tolerate memory latency: multithreading, prefetching, predication, speculation – Executing multiple instructions in parallel: pipelining, multiple issue (in-/out-of-order, VLIW), SIMD multimedia extensions (inst. -level parallelism, ILP) 82 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

End of Sequential Programming? • Infeasible for continuing improving performance of uniprocessors – Power, clocking, . . . • Multicore architecture prevails (homogeneous or heterogeneous) – Achieve performance gains with simpler processors • Sequential programming still alive! – Why? – Throughput versus execution time • Can we live with sequential prog. forever? 83 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Parallel Programming • A programming style that specify concurrency (control structure) & interaction (communication structure) between concurrent subtasks – Still in imperative language style • Concurrency can be expressed at various levels of granularity – Machine instruction level, high-level language statement level, unit level, program level • Different models assume different architectural support – Look at parallel architectures first 84 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

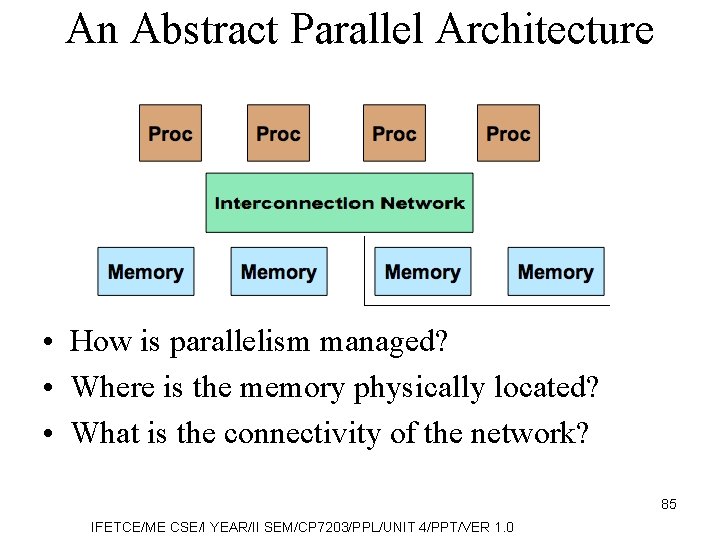

An Abstract Parallel Architecture • How is parallelism managed? • Where is the memory physically located? • What is the connectivity of the network? 85 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

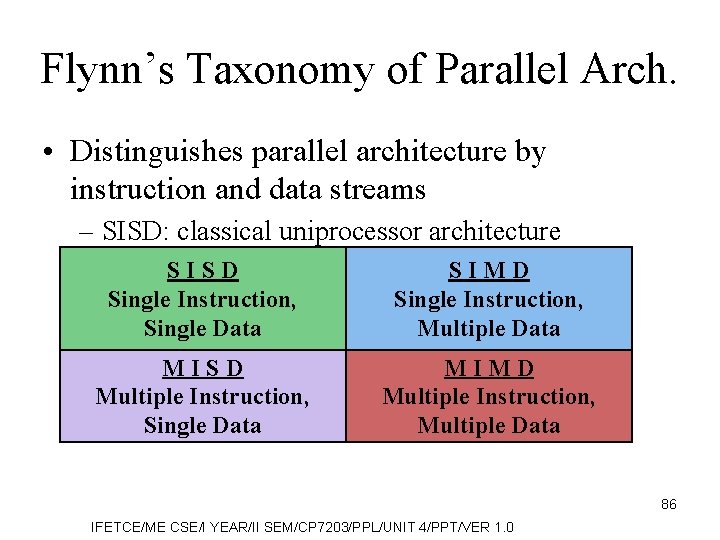

Flynn’s Taxonomy of Parallel Arch. • Distinguishes parallel architecture by instruction and data streams – SISD: classical uniprocessor architecture SISD Single Instruction, Single Data SIMD Single Instruction, Multiple Data MISD Multiple Instruction, Single Data MIMD Multiple Instruction, Multiple Data 86 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

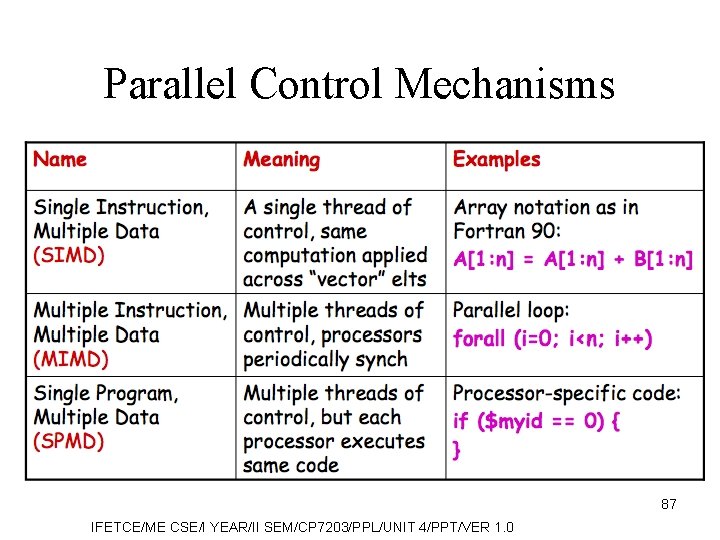

Parallel Control Mechanisms 87 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

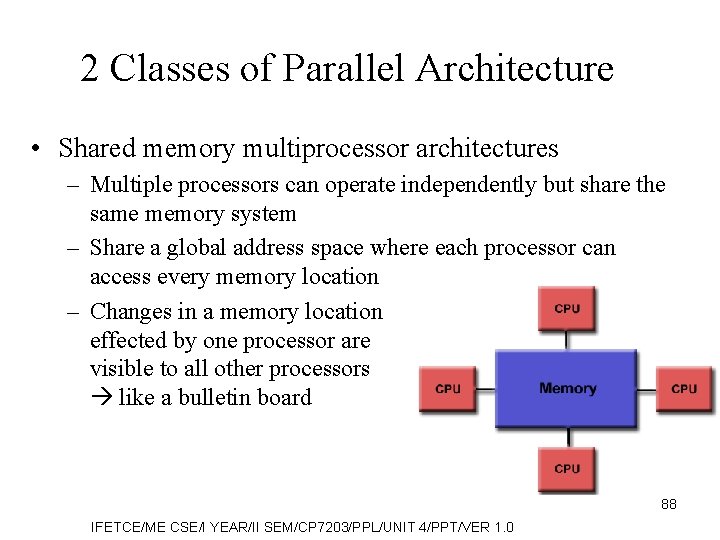

2 Classes of Parallel Architecture • Shared memory multiprocessor architectures – Multiple processors can operate independently but share the same memory system – Share a global address space where each processor can access every memory location – Changes in a memory location effected by one processor are visible to all other processors like a bulletin board 88 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

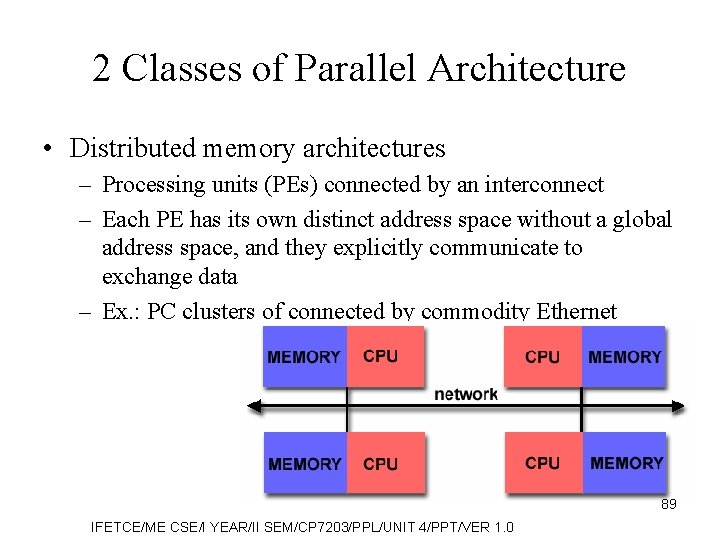

2 Classes of Parallel Architecture • Distributed memory architectures – Processing units (PEs) connected by an interconnect – Each PE has its own distinct address space without a global address space, and they explicitly communicate to exchange data – Ex. : PC clusters of connected by commodity Ethernet 89 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

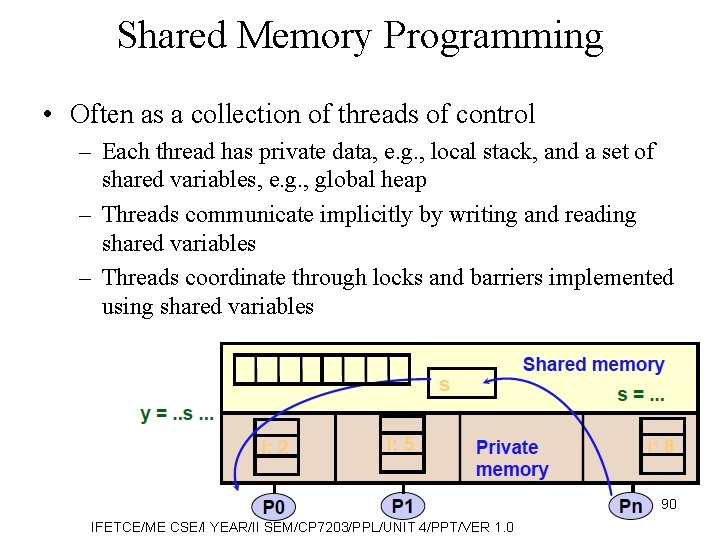

Shared Memory Programming • Often as a collection of threads of control – Each thread has private data, e. g. , local stack, and a set of shared variables, e. g. , global heap – Threads communicate implicitly by writing and reading shared variables – Threads coordinate through locks and barriers implemented using shared variables 90 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

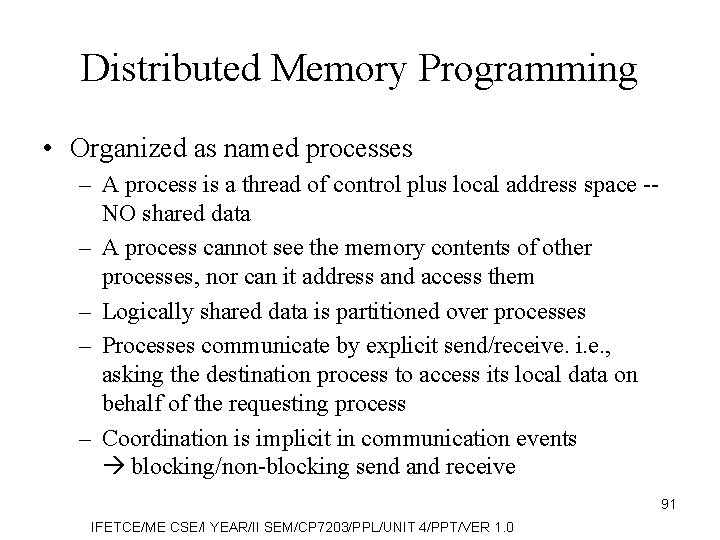

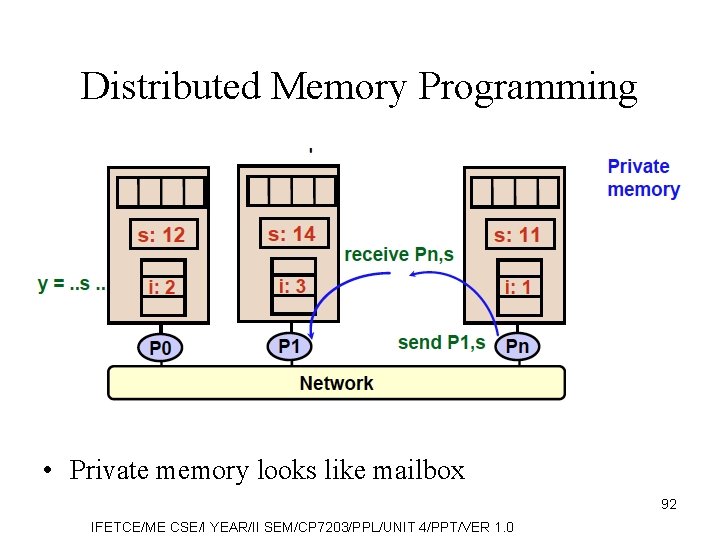

Distributed Memory Programming • Organized as named processes – A process is a thread of control plus local address space -NO shared data – A process cannot see the memory contents of other processes, nor can it address and access them – Logically shared data is partitioned over processes – Processes communicate by explicit send/receive. i. e. , asking the destination process to access its local data on behalf of the requesting process – Coordination is implicit in communication events blocking/non-blocking send and receive 91 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Distributed Memory Programming • Private memory looks like mailbox 92 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Specifying Concurrency What language supports are needed for parallel programming? • Specifying (parallel) control flows – How to create, start, suspend, resume, stop processes/threads? How to let one process/thread explicitly wait for events or another process/thread? • Specifying data flows among parallel flows – How to pass a data generated by one process/thread to another process/thread? – How to let multiple process/thread access common resources, e. g. , counter, with conflicts 93 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Specifying Concurrency • Many parallel programming systems provide libraries and perhaps compiler pre-processors to extend a traditional imperative language, such as C, for parallel programming – Examples: Pthread, Open. MP, MPI, . . . • Some languages have parallel constructs built directly into the language, e. g. , Java, C# • So far, the library approach works fine 94 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Shared Memory Prog. with Threads • Several thread libraries: • PThreads: the POSIX threading interface – POSIX: Portable Operating System Interface for UNIX – Interface to OS utilities – System calls to create and synchronize threads • Open. MP is newer standard – Allow a programmer to separate a program into serial regions and parallel regions – Provide synchronization constructs – Compiler generates thread program & synch. – Extensions to Fortran, C, C++ mainly by directives IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0 95

Thread Basics • A thread is a program unit that can be in concurrent execution with other program units • Threads differ from ordinary subprograms: – When a program unit starts the execution of a thread, it is not necessarily suspended – When a thread’s execution is completed, control may not return to the caller – All threads run in the same address space but have own runtime stacks 96 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

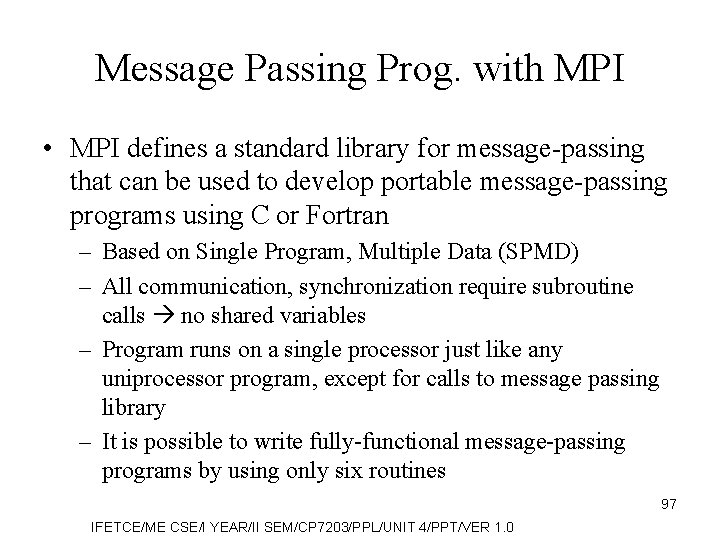

Message Passing Prog. with MPI • MPI defines a standard library for message-passing that can be used to develop portable message-passing programs using C or Fortran – Based on Single Program, Multiple Data (SPMD) – All communication, synchronization require subroutine calls no shared variables – Program runs on a single processor just like any uniprocessor program, except for calls to message passing library – It is possible to write fully-functional message-passing programs by using only six routines 97 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

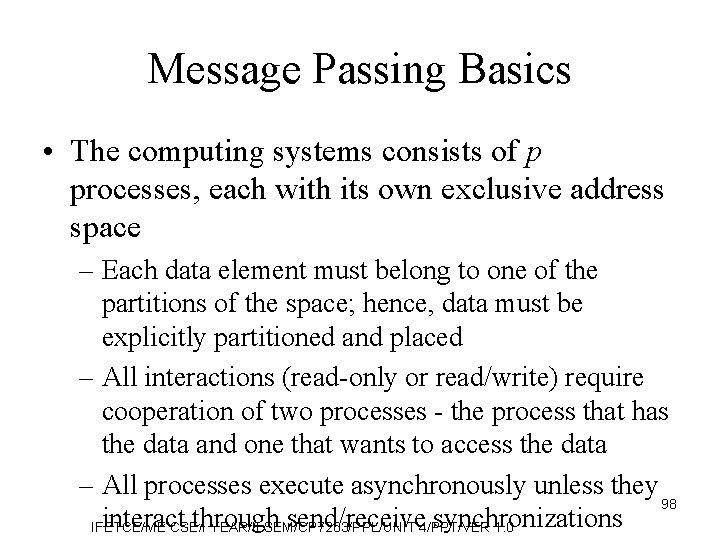

Message Passing Basics • The computing systems consists of p processes, each with its own exclusive address space – Each data element must belong to one of the partitions of the space; hence, data must be explicitly partitioned and placed – All interactions (read-only or read/write) require cooperation of two processes - the process that has the data and one that wants to access the data – All processes execute asynchronously unless they 98 interact through send/receive 4/PPT/VER synchronizations IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 1. 0

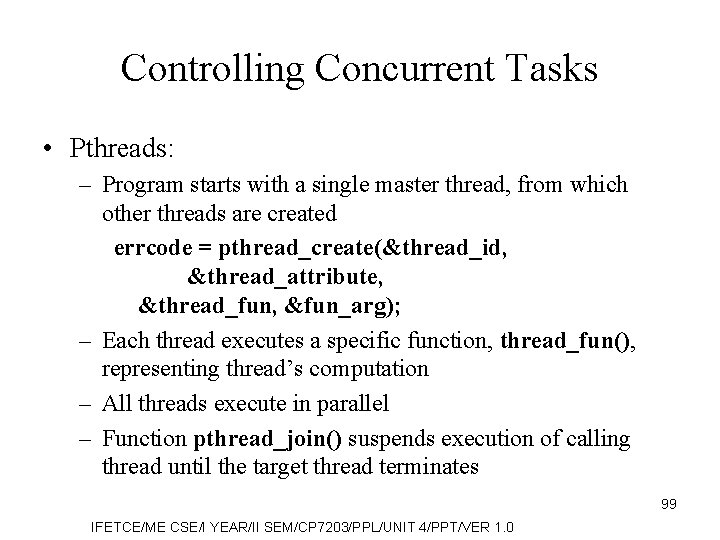

Controlling Concurrent Tasks • Pthreads: – Program starts with a single master thread, from which other threads are created errcode = pthread_create(&thread_id, &thread_attribute, &thread_fun, &fun_arg); – Each thread executes a specific function, thread_fun(), representing thread’s computation – All threads execute in parallel – Function pthread_join() suspends execution of calling thread until the target thread terminates 99 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

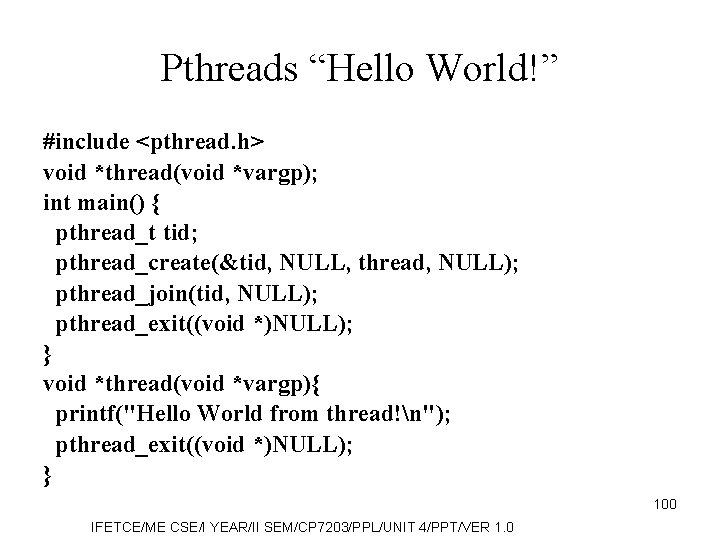

Pthreads “Hello World!” #include <pthread. h> void *thread(void *vargp); int main() { pthread_t tid; pthread_create(&tid, NULL, thread, NULL); pthread_join(tid, NULL); pthread_exit((void *)NULL); } void *thread(void *vargp){ printf("Hello World from thread!n"); pthread_exit((void *)NULL); } 100 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

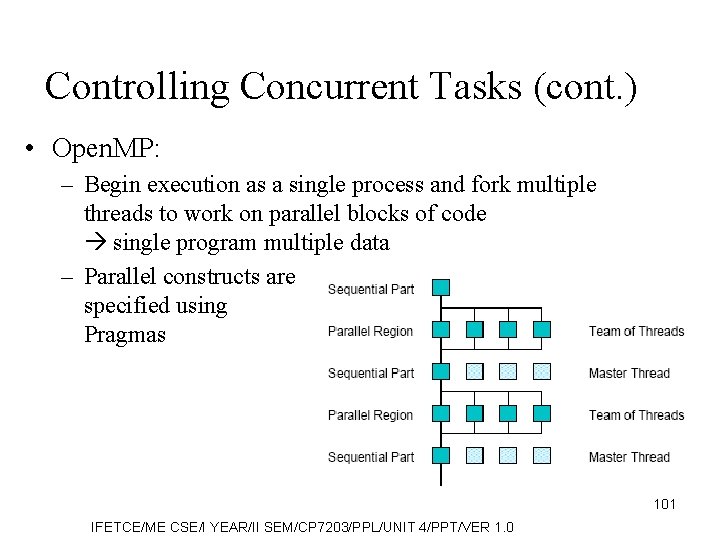

Controlling Concurrent Tasks (cont. ) • Open. MP: – Begin execution as a single process and fork multiple threads to work on parallel blocks of code single program multiple data – Parallel constructs are specified using Pragmas 101 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

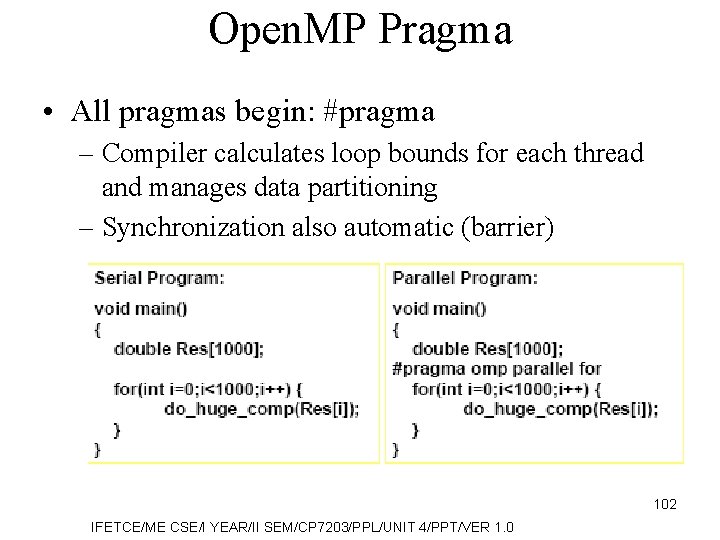

Open. MP Pragma • All pragmas begin: #pragma – Compiler calculates loop bounds for each thread and manages data partitioning – Synchronization also automatic (barrier) 102 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

![Open. MP “Hello World!” #include <omp. h> int main (int argc, char *argv[]) { Open. MP “Hello World!” #include <omp. h> int main (int argc, char *argv[]) {](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/69038527f3ec05df3defc020b77e8189/image-103.jpg)

Open. MP “Hello World!” #include <omp. h> int main (int argc, char *argv[]) { int th_id, nthreads; #pragma omp parallel private(th_id) { th_id = omp_get_thread_num(); printf("Hello World: %dn", th_id); #pragma omp barrier if ( th_id == 0 ) { nthreads = omp_get_num_threads(); printf("%d threadsn", nthreads); } } return EXIT_SUCCESS; } 103 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

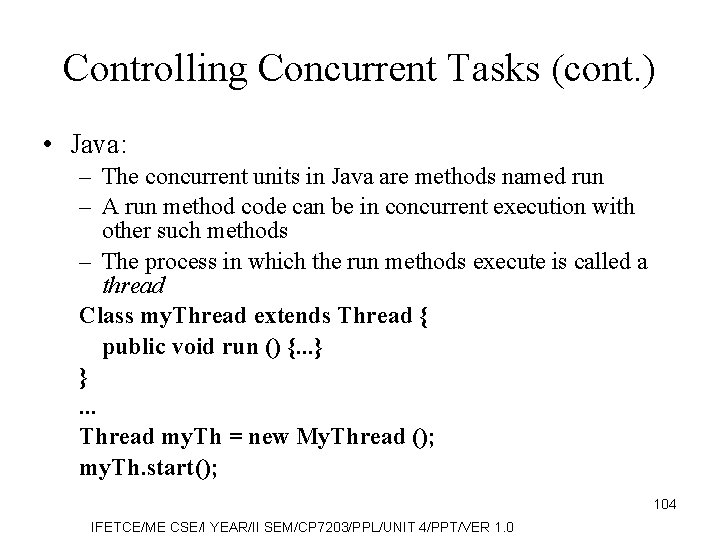

Controlling Concurrent Tasks (cont. ) • Java: – The concurrent units in Java are methods named run – A run method code can be in concurrent execution with other such methods – The process in which the run methods execute is called a thread Class my. Thread extends Thread { public void run () {. . . } }. . . Thread my. Th = new My. Thread (); my. Th. start(); 104 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

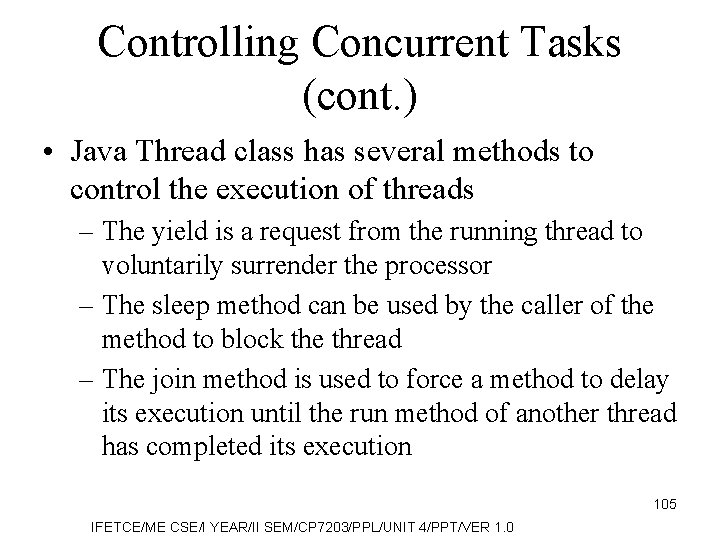

Controlling Concurrent Tasks (cont. ) • Java Thread class has several methods to control the execution of threads – The yield is a request from the running thread to voluntarily surrender the processor – The sleep method can be used by the caller of the method to block the thread – The join method is used to force a method to delay its execution until the run method of another thread has completed its execution 105 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Controlling Concurrent Tasks (cont. ) • Java thread priority: – A thread’s default priority is the same as the thread that create it – If main creates a thread, its default priority is NORM_PRIORITY – Threads defined two other priority constants, MAX_PRIORITY and MIN_PRIORITY – The priority of a thread can be changed with the methods set. Priority 106 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Controlling Concurrent Tasks (cont. ) • MPI: – Programmer writes the code for a single process and the compiler includes necessary libraries mpicc -g -Wall -o mpi_hello. c – The execution environment starts parallel processes mpiexec -n 4. /mpi_hello 107 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

![MPI “Hello World!” #include "mpi. h" int main(int argc, char *argv[]) { int rank, MPI “Hello World!” #include "mpi. h" int main(int argc, char *argv[]) { int rank,](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/69038527f3ec05df3defc020b77e8189/image-108.jpg)

MPI “Hello World!” #include "mpi. h" int main(int argc, char *argv[]) { int rank, size; MPI_Init(&argc, &argv); MPI_Comm_rank(MPI_COMM_WORLD, &rank); MPI_Comm_size(MPI_COMM_WORLD, &size); printf(”Hello World from process %d of %dn", rank, size); MPI_Finalize(); return 0; } 108 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Sharing Data • Pthreads: – Variables declared outside of main are shared – Object allocated on the heap may be shared (if pointer is passed) – Variables on the stack are private: passing pointer to these around to other threads can cause problems – Shared variables can be read and written directly by all threads need synchronization to prevent races – Synchronization primitives, e. g. , semaphores, locks, mutex, barriers, are used to sequence the executions of the threads to indirectly sequence the data passed through shared variables 109 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Sharing Data (cont. ) • Open. MP: – shared variables are shared; default is shared – private variables are private – Loop index is private int bigdata[1024]; void* foo(void* bar) { int tid; #pragma omp parallel shared (bigdata) private (tid) { /* Calc. here */ } } 110 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

![Sharing Data (cont. ) • MPI: int main( int argc, char *argv[]) { int Sharing Data (cont. ) • MPI: int main( int argc, char *argv[]) { int](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/69038527f3ec05df3defc020b77e8189/image-111.jpg)

Sharing Data (cont. ) • MPI: int main( int argc, char *argv[]) { int rank, buf; MPI_Status status; MPI_Init(&argv, &argc); MPI_Comm_rank(MPI_COMM_WORLD, &rank); if (rank == 0) { buf = 123456; MPI_Send(&buf, 1, MPI_INT, 1, 0, MPI_COMM_WORLD); } else if (rank == 1) { MPI_Recv(&buf, 1, MPI_INT, 0, 0, MPI_COMM_WORLD, &status); } MPI_Finalize(); } 111 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

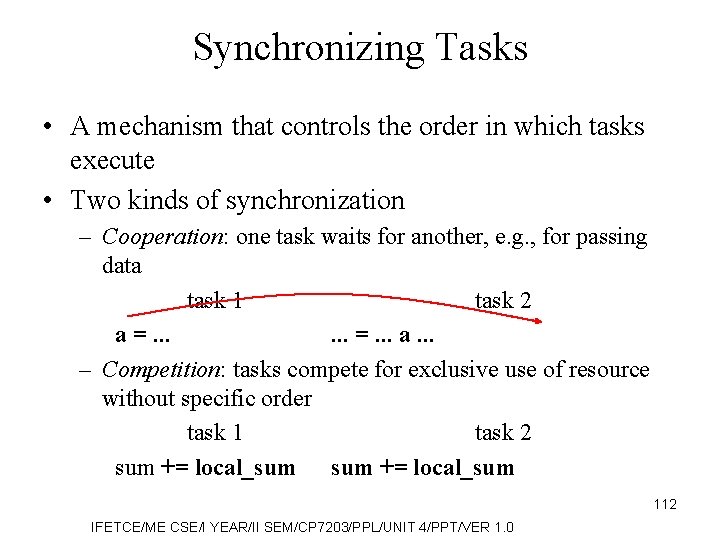

Synchronizing Tasks • A mechanism that controls the order in which tasks execute • Two kinds of synchronization – Cooperation: one task waits for another, e. g. , for passing data task 1 task 2 a =. . . a. . . – Competition: tasks compete for exclusive use of resource without specific order task 1 task 2 sum += local_sum 112 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Synchronizing Tasks (cont. ) • Pthreads: – Provide various synchronization primitives, e. g. , mutex, semaphore, barrier – Mutex: protects critical sections -- segments of code that must be executed by one thread at any time • Protect code to indirectly protect shared data – Semaphore: synchronizes between two threads using sem_post() and sem_wait() – Barrier: synchronizes threads to reach the same point in code before going any further 113 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

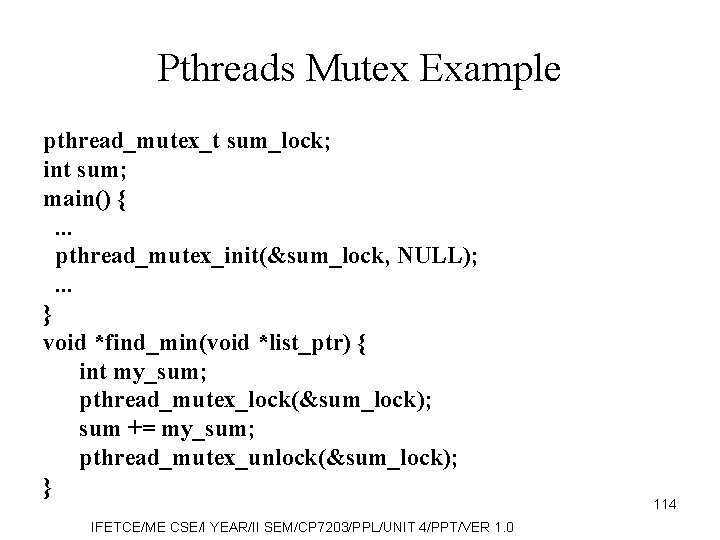

Pthreads Mutex Example pthread_mutex_t sum_lock; int sum; main() {. . . pthread_mutex_init(&sum_lock, NULL); . . . } void *find_min(void *list_ptr) { int my_sum; pthread_mutex_lock(&sum_lock); sum += my_sum; pthread_mutex_unlock(&sum_lock); } IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0 114

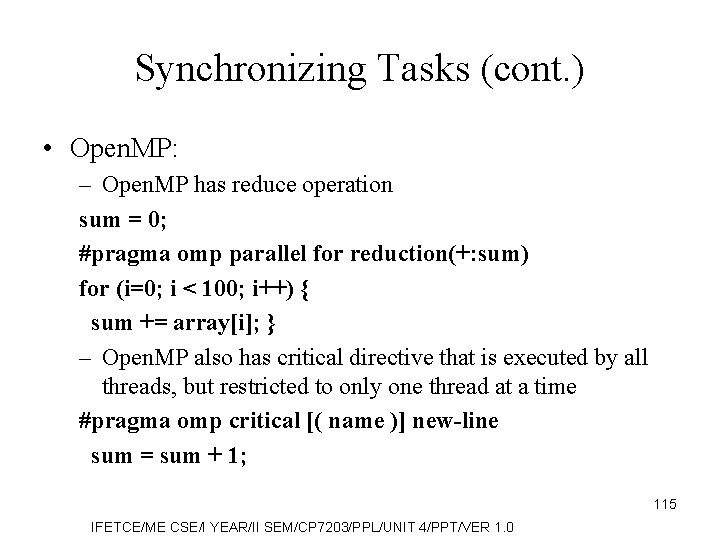

Synchronizing Tasks (cont. ) • Open. MP: – Open. MP has reduce operation sum = 0; #pragma omp parallel for reduction(+: sum) for (i=0; i < 100; i++) { sum += array[i]; } – Open. MP also has critical directive that is executed by all threads, but restricted to only one thread at a time #pragma omp critical [( name )] new-line sum = sum + 1; 115 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Synchronizing Tasks (cont. ) • Java: – A method that includes the synchronized modifier disallows any other method from running on the object while it is in execution public synchronized void deposit(int i) {…} public synchronized int fetch() {…} – The above two methods are synchronized which prevents them from interfering with each other 116 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Synchronizing Tasks (cont. ) • Java: – Cooperation synchronization is achieved via wait, notify, and notify. All methods – All methods are defined in Object, which is the root class in Java, so all objects inherit them – The wait method must be called in a loop – The notify method is called to tell one waiting thread that the event it was waiting has happened – The notify. All method awakens all of the threads on the object’s wait list 117 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

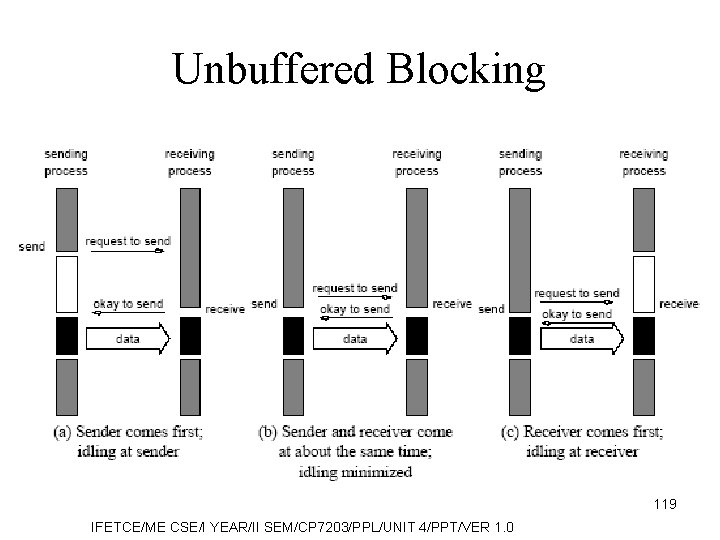

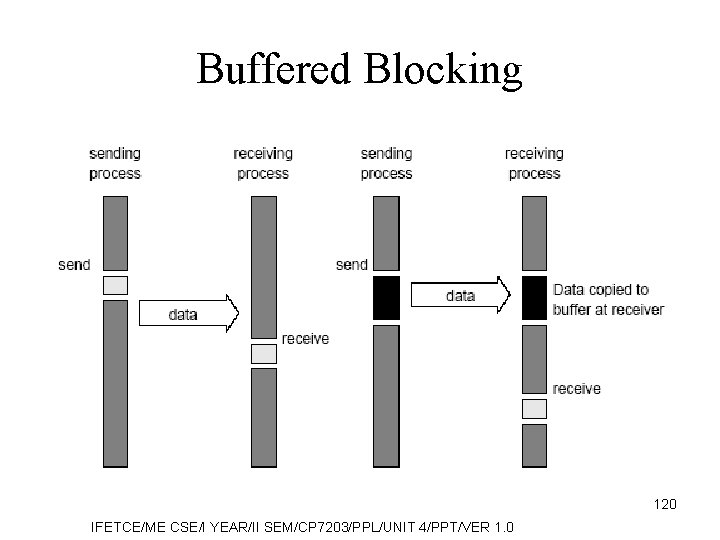

Synchronizing Tasks (cont. ) • MPI: – Use send/receive to complete task synchronizations, but semantics of send/receive have to be specialized – Non-blocking send/receive: • Non-blocking send/receive: send() and receive() calls will return no matter whether data has arrived – Blocking send/receive: • Unbuffered blocking send() does not return until matching receive() is encountered at receiving process • Buffered blocking send() will return after the sender has copied the data into the designated buffer • Blocking receive() forces the receiving process to wait 118 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Unbuffered Blocking 119 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

Buffered Blocking 120 IFETCE/ME CSE/I YEAR/II SEM/CP 7203/PPL/UNIT 4/PPT/VER 1. 0

- Slides: 120