Unit 5 Nonverbal Communication Objectives 1 The definition

Unit 5 Nonverbal Communication

Objectives教学内容 1 The definition 2 The 3 The Status 4 Study Area 5 Function Cultural Differences in NC 2

Introductory Case 3 3

Warm Cases: Case 1 Personal Space Question: Why did that woman suddenly stop talking with Mark and turned to another man? 5

Comment: This is a typical case of misunderstanding caused by different perceptions about body distance. In Denmark, people prefer intimate space which is between 20 -30 centimeters while in Australia, the body distance of 40 -50 centimeters is more acceptable. Obviously she felt somewhat threatened and lost her sense of comfort. 6

Case 3 Left in the Cold How would you explain the Director’s behavior toward Katherine? How would you make the Director understand why Katherine felt frustrated angry? 7

Comment: This is a typical cultural clash between Chinese and Westerners. There is a great difference in the concept of appointment and its behavior pattern in different cultures. To Americans: An appointment is a confirmation to meet at a precise time. If it is scheduled, both parties should respect the appointment time. And it should not be interrupted by other things or people. They are good time-keepers. 8

To Chinese: They view appointments in a more flexible manner and they are more casual about commitments. The Director should have tried to avoid any interruption since he made an ten o’clock appointment. What’s more, he was still talking with another teacher when K arrived on time and when their meeting finally began, it was interrupted again. No wonder K became frustrated angry. 9

Case 4 She Is Not Supposed to Be Wearing Trousers Comment: In Korea, a woman with social status will generally wear dress or skirt. Women wearing trousers are generally common citizens of low social status. The Korean interpreter assumed that the Chinese female college teachers held high social status and should therefore wear skirts. 10

Case 7 A misunderstanding of Seating Culture Comment: One can control one’s verbal language to disguise himself consciously. But unconsciously his physical behavior can give him away. e. g. Putting one’s feet with leather shoes onto the desk ----Americans Talking and eating with a squatting posture--Shanxi, the Yellow Plateau of China. 11

1. The definition of Nonverbal Communication Narrowly speaking, nonverbal communication (非 言 语 交 际 ) refers to intentional use of nonspoken symbol to communicate a specific message. 12

How often have we listened to someone speak and wondered what the speaker really was saying? We may even come to the conclusion that the speaker means the opposite of what he says. 13

14 14

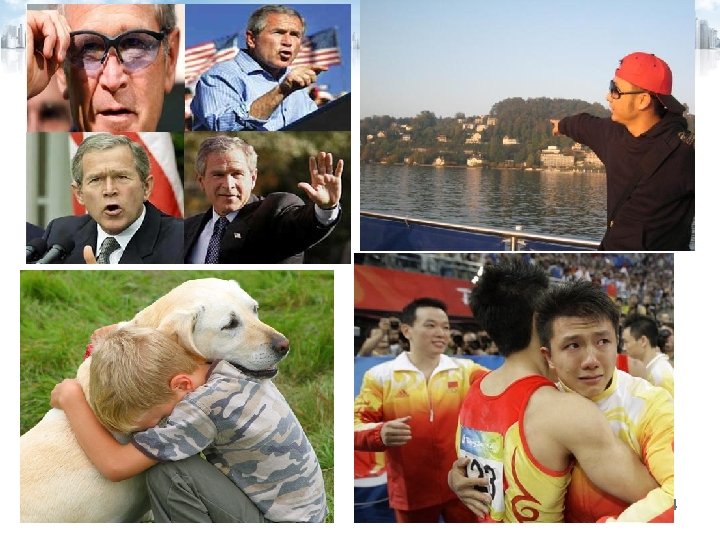

We may base our judgment on an evaluation of tone, intonation, emphasis, facial expressions, gestures and hand movements, distance, and eye contact—in short, nonverbal signals or the silent language. 15

Status of Nonverbal Behavior accounts for 65% - 93% of the total meaning of communication NV behavior accounts for much of the meaning we derive from conversations. 16

When nonverbal and verbal messages appear inconsistent, most of us tend to believe the nonverbal messages. NV behavior spontaneously reflects the speaker’s sub-consciousness. 17

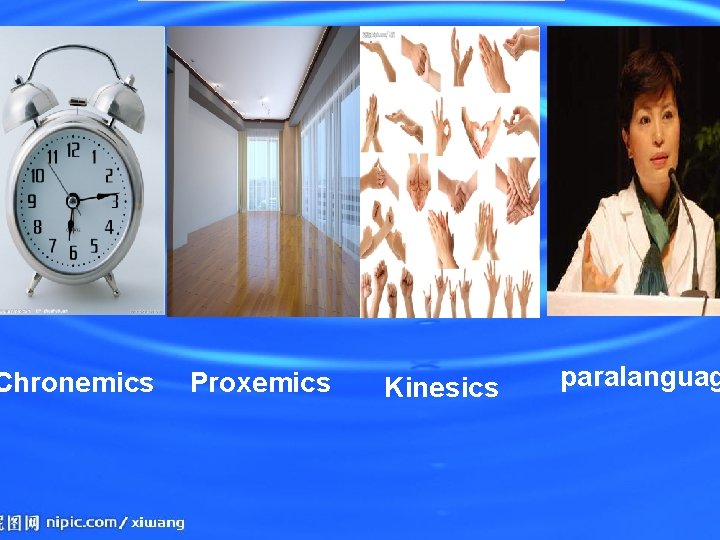

Chronemics Proxemics Kinesics paralanguag

1. Body Language Kinesics身势学 is the non-verbal behavior related to movement, either of any part of the body, or the body as a whole. In short all communicative body movements are generally classified as kinesics. 19

Facial expressions Eye contact Posture and stance Gesture 20

(1)Postures The way we sit, stand, and walk sends a nonverbal message. In Western culture to stand tall conveys confidence. The confident person stands erect with shoulders back and head up. The posture signals, "I am not afraid of anything. " 21

Appropriate posture is related to a person's status in society. For example, the manager may stand erect when talking to subordinates, but the subordinates may drop their shoulders when talking to the manager. 22

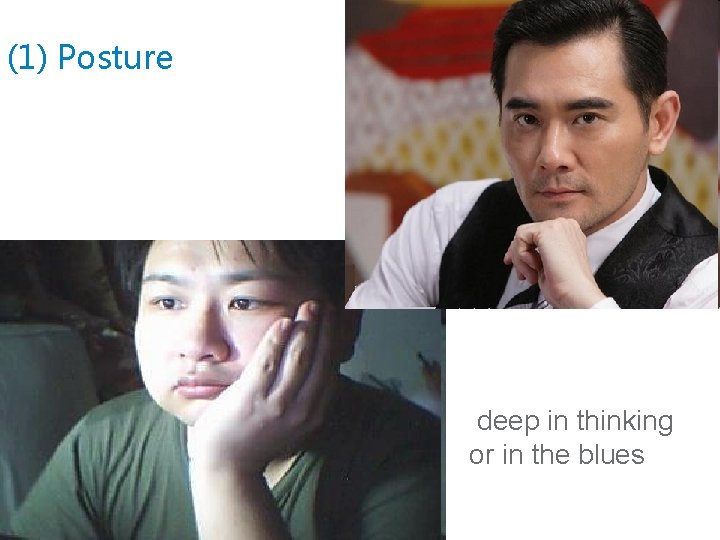

(1) Posture deep in thinking or in the blues

attentive and interested absent-minded or lacking interest

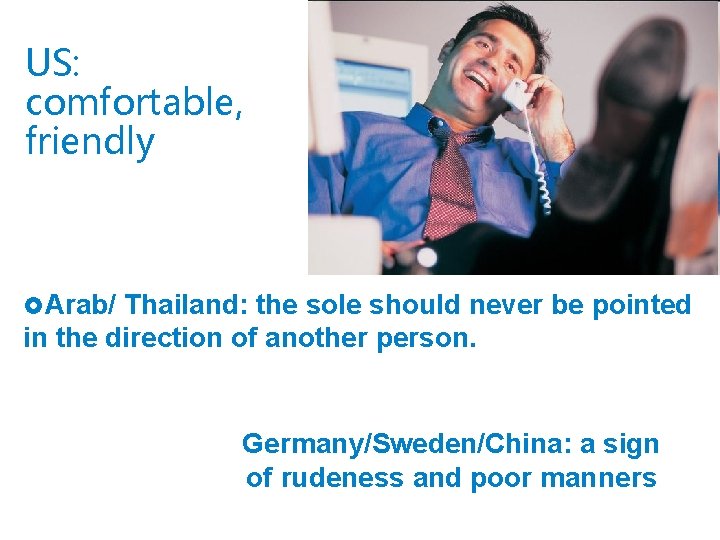

US: comfortable, friendly £Arab/ Thailand: the sole should never be pointed in the direction of another person. Germany/Sweden/China: a sign of rudeness and poor manners

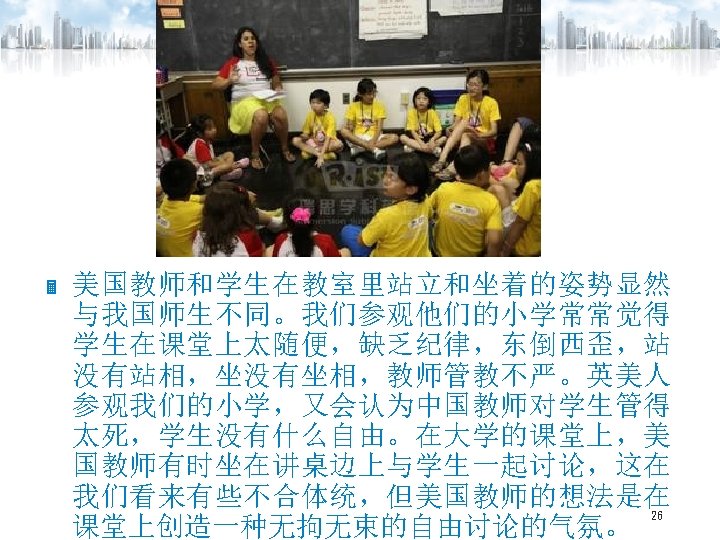

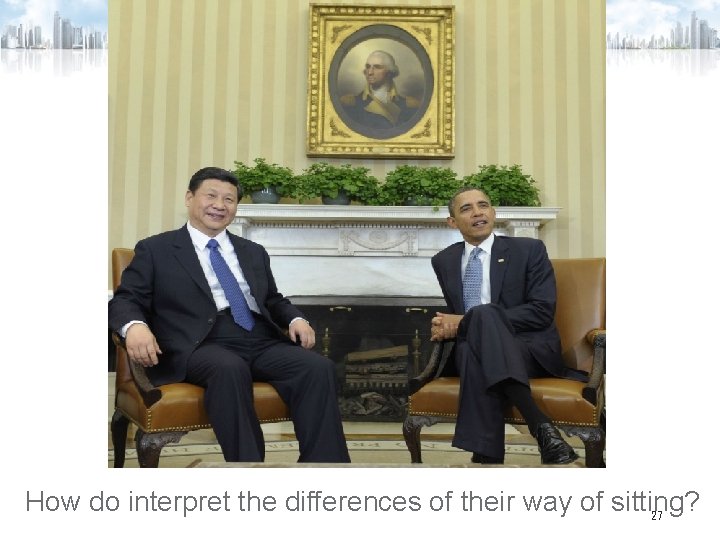

How do interpret the differences of their way of sitting? 27

Formality vs. Informality Chinese people tend to be formal in their address, postures. When introducing the Chinese, the surname comes first and the given name last, with titles. Americans assume that informality is very important. In the U. S. first names are used almost immediately; Titles are used infrequently. 28

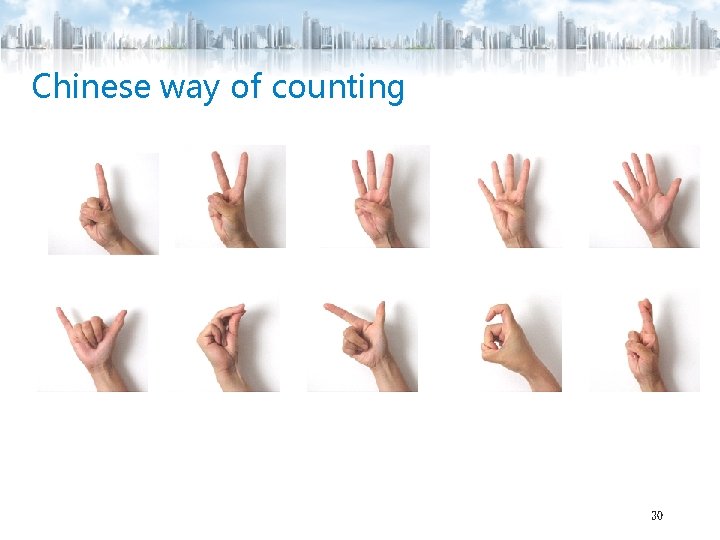

Chinese way of counting 30

The Chinese point to the tip of their nose, and ask “Me”? But the westerners point to their chest. Me? 31

The index finger pressed against the lips is a silent suggestion to stop talking, for someone may overhear us. Most often used by people to warn the others who are speaking loudly in class or at theater. Sometimes it means a sign to tell others that a special man is coming or entering. Be quiet, please! 32

(2) Gestures– point to objects and people US: ok Asia: rude German Janpanese

US : OK Tuni sian : Fool n a an y p Ja one m o K d : a re s e i tr n u o c n a c i r e m y: A n a n i t m La Ger d e n n a ce s ob Ara bs: (a b extr arin eme g of hos teet tility h)

Thumbs-up Great ! 35

This characteristically American gesture remains well understood in most places for its American-ness. Except in a few places, that is, where it could land you in serious trouble - namely Australia and Nigeria. In these countries, it means, something like "up yours. " Do not use it. 36

V-sign 40

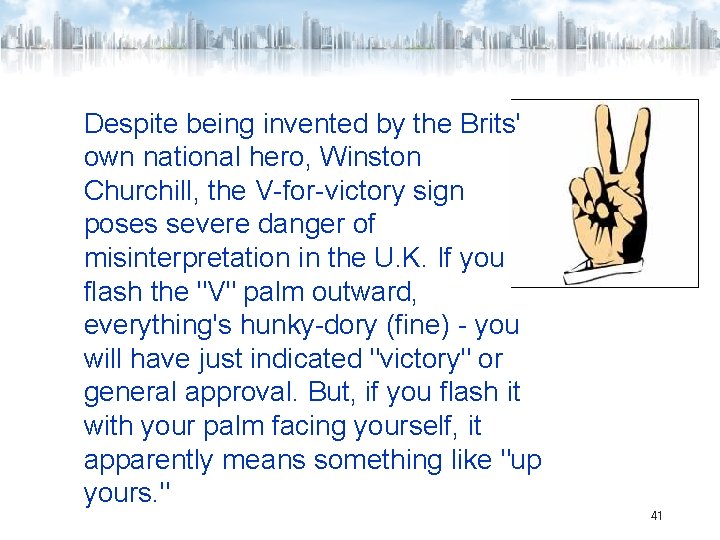

Despite being invented by the Brits' own national hero, Winston Churchill, the V-for-victory sign poses severe danger of misinterpretation in the U. K. If you flash the "V" palm outward, everything's hunky-dory (fine) - you will have just indicated "victory" or general approval. But, if you flash it with your palm facing yourself, it apparently means something like "up yours. " 41

Up yours 42

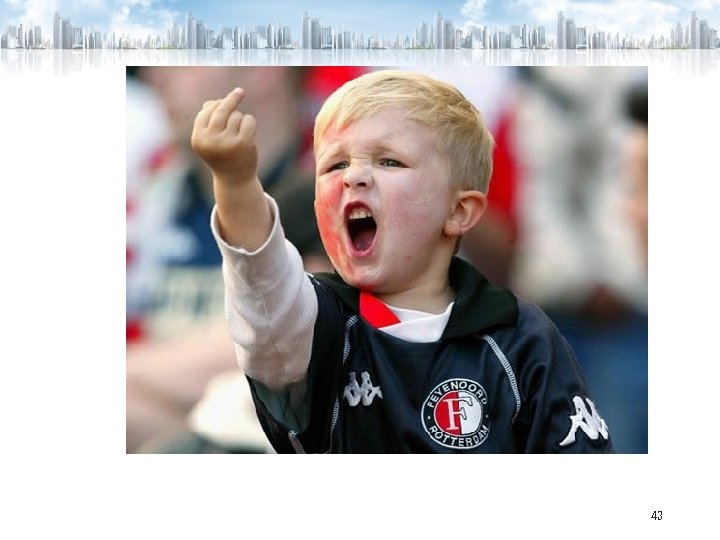

43

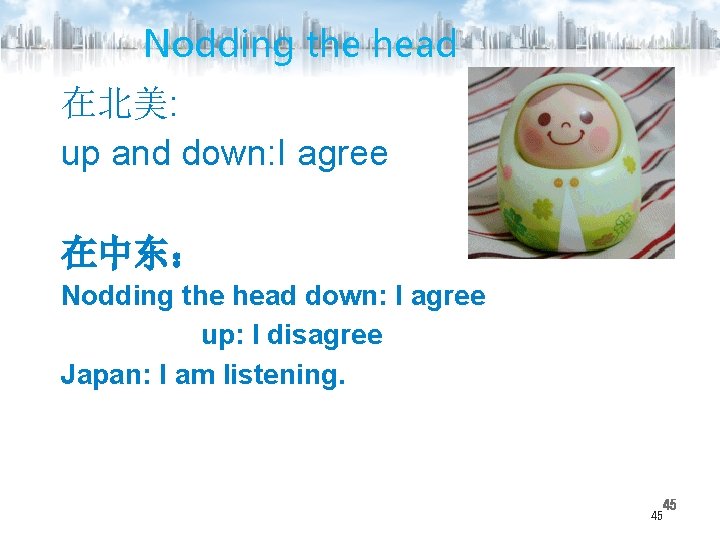

Nodding the head 在北美: up and down: I agree 在中东: Nodding the head down: I agree up: I disagree Japan: I am listening. 45 45

Shaking the head most countries: refusal or disapproval Sri. Lanks, Nepal, and India: agreement

(3) Facial expressions Sadness Anger Surprise Fear Enjoyment Disgust Contempt

(3)Facial Expressions While many facial expressions carry similar meanings in a variety of cultures, the frequency and intensity of their use may vary. Latin and Arab cultures use more intense facial expressions, whereas East Asian cultures use more subdued facial expressions. 美国人的面部表情比亚洲人多,但比拉丁美洲人、 南欧人少。实际上,在亚洲人中面部表情仍有很 大的区别。在日本人看来,中国人的感情比日本 人外露。 48

sadness Mediterranean cultures: exaggerate signs of grief or sadness—men crying in public American: suppress the emotions Japanese: hide expressions of anger, sorrow, or disappointment—laughing or smiling Chinese: control emotions—saving face

smile American: a sign of happiness or friendly affirmation Japanese: mask an emotion or avoid answering a question Korean: too much smiling a shallow person Thailand: the land of Smiles 52

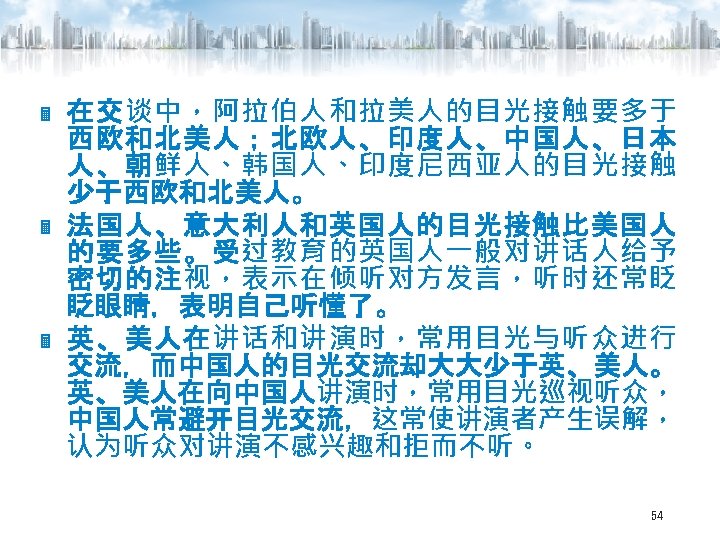

(4) Eye contact North Americans: direct eye contact a sign of honesty. If not, a sign of untruthfulness, shame or embarrassment Chinese: avoid long direct eye contact to show politeness, or respect, or obedience Japanese people: avoid prolonged eye contact is considered rude, threatening and disrespectful. Latin American and Caribbean : a sign of respect 53

(5)Haptics (touch) Haptics is the study of our use of touch to communicate. Touching and being touched are essential to a healthy life. Touch can communicate power and status. Women tend to touch to show liking, while men often use touch to exert power. 55

If you are talking with a friend in a coffee shop, you may touch each other once or twice in an hour in the U. S. have no London. touch a hundred times in an hour in a French or a Parisian café. touch at all in 56

Rude or Not Rude? In Thailand Laos, it is rude for a stranger or acquaintance to touch a child on the top of the head. 57

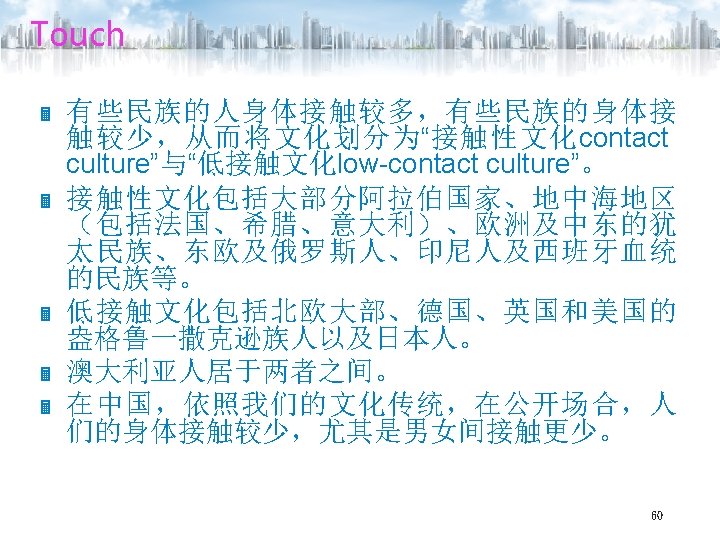

Cultural Variations in Touch Don’t touch Japan Middle touch Australia United States Estonia Canada France Scandinavia China Other Northern European countries Ireland India Touch Latin American countries Italy Greece Spain Middle East Portugal Russia countries 59

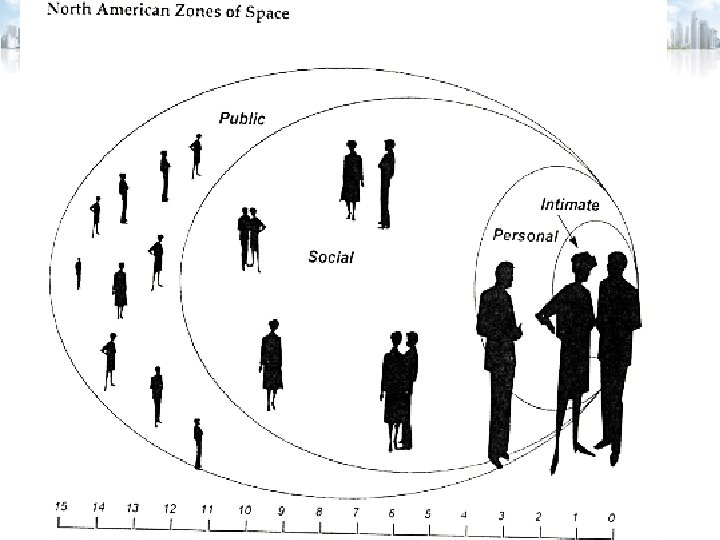

2. Space lanage Every culture has norms for using space. In India, there are elaborate rules about how closely members of each caste may approach other castes. Arabs of the same sex do stand much closer than North Americans in an elevator maintain personal space if the physical space permits while an Arab entering the elevator may stand next to another person and be touching even though no one else is in the elevator. 62

Space The language of space is powerful. How close can we get to people; how distant should we be? Most of us never think about space; we intuitively know what the right distance is. The problem is that the acceptable use of space varies widely between cultures. What feels right for us may be totally offensive to someone else. 63

Our private space is sacred, and we feel violated if someone invades that personal bubble. In the United States that bubble is about the length of an arm. That bubble is a little bit smaller in France but larger in the Netherlands and Germany. It is even larger in Japan but much smaller in Latin countries and the Middle East. 64

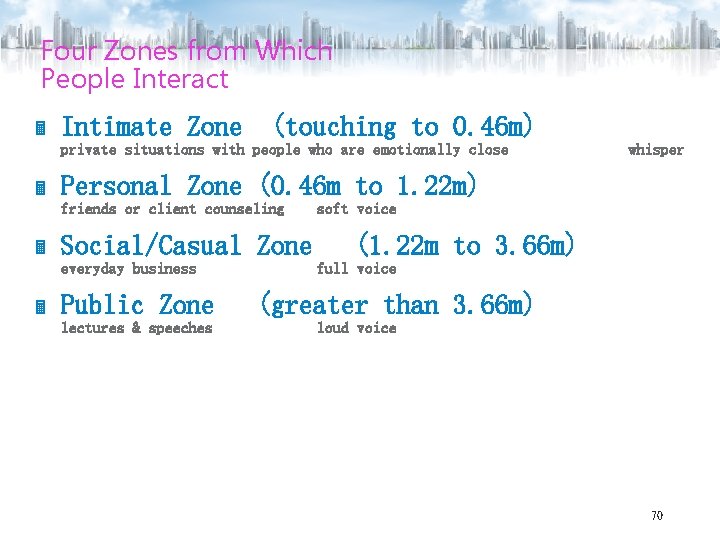

Four Zones from Which People Interact Intimate Zone (touching to 0. 46 m) private situations with people who are emotionally close Personal Zone (0. 46 m to 1. 22 m) friends or client counseling Social/Casual Zone everyday business whisper Public Zone lectures & speeches soft voice (1. 22 m to 3. 66 m) full voice (greater than 3. 66 m) loud voice 70

INTIMATE 71

PERSONAL 72

SOCIAL 73

PUBLIC 74

75

Restaurants can arrange seating to encourage people to spend time or to eat quickly and leave. 76

3. Time Language Attitudes toward time vary from culture to culture. Countries that follow monochronic time perform only one major activity at a time (U. S. , England, Switzerland, Germany). Countries that follow polychromic time work on several activities simultaneously (Latin America, the Mediterranean, the Arabs). 77

U. S. persons are very time conscious and value punctuality. Being late for meetings is viewed as rude and insensitive behavior; tardiness also conveys that the person is not well organized. Germans and Swiss people are even more time conscious; People of Singapore and Hong Kong also value punctuality. In Algeria, on the other hand, punctuality is not widely regarded. Latin American countries have a manana attitude; People in Arab cultures have a casual attitude toward time. 80

Time in general Cultures differ widely in the perception of time. Promptness, for example, is highly valued by Americans, who become insulted when kept waiting for an appointment or a visitor’s overdue arrival. 82

The Japanese are extremely prompt, often to the second, in meeting with someone at an appointed time. 83

In contrast, individuals in Latin America and Middle East are extremely relaxed about punctuality. 84

Americans and others in the Western world are said to live in the present and the near future and hence plan carefully. 85

To the Hindu and Buddhist this life is only one among countless lives yet to come, merely one dot in an endless serious of dots. 86

American View of Time Americans look upon time as a present, tangible commodity, something to be used, something to be held accountable for. They spend it, waste it, save it, divide it, and are stewards of it, just as if they were handling some tangible object. 87

In order to use time well, they schedule the day and week and month carefully, set up timetables, and establish precise priorities. 88

They prepare carefully for business conferences, for personal interviews, for group meetings of all types. This they assume to be an elementary aspect of efficiency. 89

Americans expect an invitation to a dinner or a request for a date or for any other social event to be offered reasonably far in advance. 90

In fact, often the last minute invitations, no matter how enticing, will be turned down basically because the recipient refuses to permit himself to be “secured” at the last minute. 91

But in the Arab and Asian world, many simply forget appointments and arrangements if they are planned too far in advance, and their last minute invitations are sincere, and certainly not to be interpreted as insults. 92

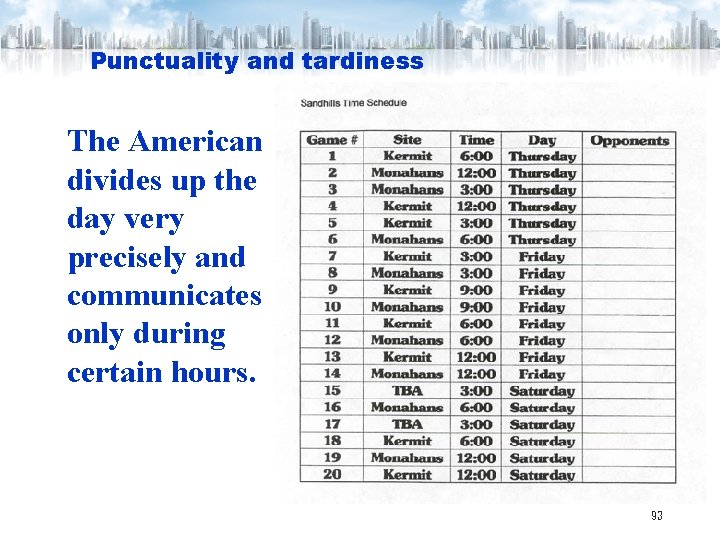

Punctuality and tardiness The American divides up the day very precisely and communicates only during certain hours. 93

He withholds communication during other hours, such as late at night or early in the morning, at which times only some emergency would initiate a telephone call, or a visit, to someone. 94

But people of some other cultures do not divide the day too rigidly and are more liable to call at any time without being prompted by an emergency. 95

For many situations Americans would consider tardiness of five minutes to be relatively serious and improper 96

Other cultures would consider such an attitude to be a rather neurotic slavery to time. 97

In some cultures it is assumed that a busy important person should come late. Hence, coming on time would only lower his prestige. 98

Paralanguage Voice modulation tempo silence 99

- Slides: 100