UNIT 3 WEATHERING AND ASSOCIATED LANDFORMS Geomorphology GEO

- Slides: 27

UNIT – 3 WEATHERING AND ASSOCIATED LANDFORMS Geomorphology (GEO 301) Geology and Geophysics Department College of Science King Saud University

WEATHERING PROCESSES • Weathering is the breakdown of rocks by mechanical disintegration and chemical decomposition. • Many rocks form under high temperatures and pressures deep in the Earth’s crust. • When exposed to the lower temperatures and pressures at the Earth’s surface and brought into contact with air, water, and organisms, they start to decay. • Weathering weakens the rocks and makes them more permeable, so making them more vulnerable to removal by agents of erosion, and the removal of weathered products exposes more rock to weathering. • The different types of weathering has already been discussed in Unit 2 • In this Unit we will take about soils and various landforms associated with weathering.

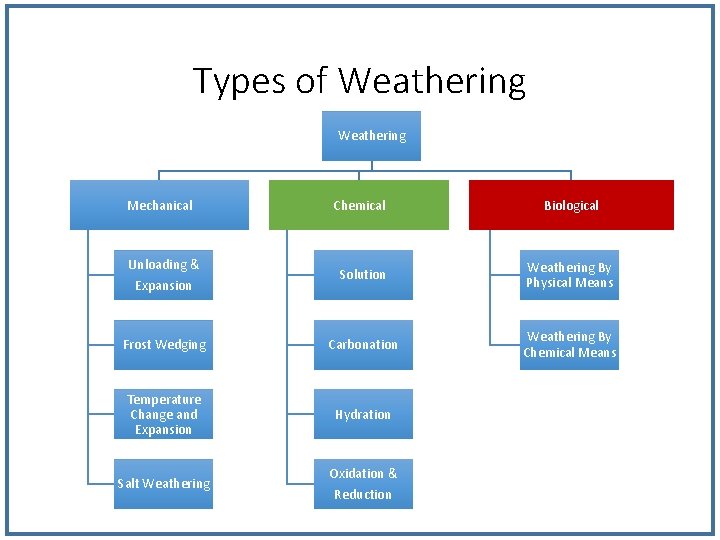

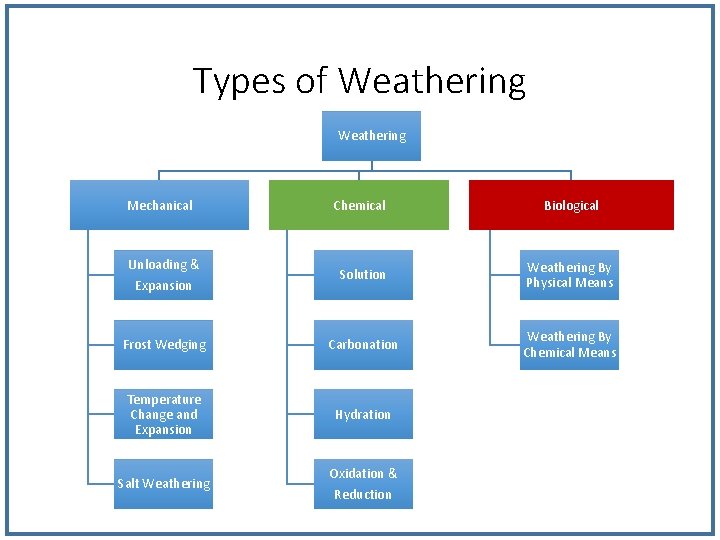

Types of Weathering Mechanical Chemical Biological Unloading & Expansion Solution Weathering By Physical Means Frost Wedging Carbonation Weathering By Chemical Means Temperature Change and Expansion Hydration Salt Weathering Oxidation & Reduction

WEATHERING PRODUCTS • There are two chief weathering environments with different types of product – weathering limited environments and transport-limited environments. • In weathering-limited environments, transport processes rates are more dominant as compared to weathering processes rates. • Therefore, any material released by weathering is removed and a regolith or soil is unable to develop and the rock composition and structure largely determine the resulting surface forms. • In transport-limited environments, weathering rates run faster than transport rates, so that regolith or soil is able to develop. • Mass movements then dominate surface forms, and forms fashioned directly by weathering are confined to the interface between regolith or soil and unweathered rock.

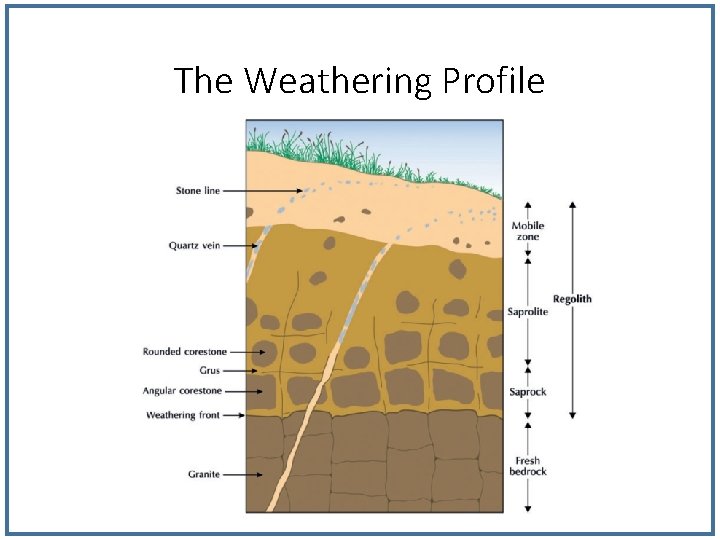

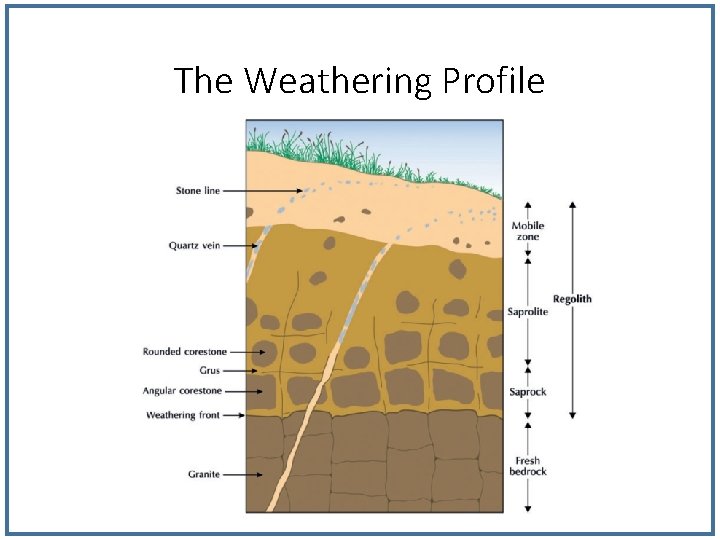

REGOLITH (Transport Limited Environment) • The weathered mantle or regolith is all the weathered material lying above the unaltered or fresh bedrock. • It may include lumps of fresh bedrock. • Often the weathered mantle or crust is differentiated into visible horizons and is called a weathering profile. • The weathering front is the boundary between fresh and weathered rock. • The layer immediately above the weathering front is sometimes called saprock, which represents the first stages of weathering. • Above the saprock lies saprolite; this is more weathered than saprock but still retains most of the structures found in the parent bedrock. • Saprolite lies where it was formed, undisturbed by mass movements or other erosive agents. • Deep weathering profiles, saprock, and saprolite are common in the tropics.

The Weathering Profile

Duricrust and hardpans • Under some circumstances, soluble materials precipitate within or on the weathered mantle to form duricrusts and hardpans. • Duricrusts are important in landform development as they act like a band of resistant rock and may cap hills. • They occur as hard nodules or crusts, or simply as hard layers. • The chief types are ferricrete (rich in iron), calcrete (rich in calcium carbonate), silcrete (rich in silica), alcrete (rich in aluminium), gypcrete (rich in gypsum), magnecrete (rich in magnesite), and manganocrete (rich in manganese)

Duricrust and hardpans • Hardpans are also hard layers but, unlike duricrusts, are not enriched in a specific element. • Duricrusts are commonly harder than the materials in which they occur and more resistant to erosion. • In consequence, they act as a shell of armour, protecting land surfaces from denudational agents. • Where duricrusts have been broken up by prolonged erosion, fragments may persist on the surface, carrying on their protective role.

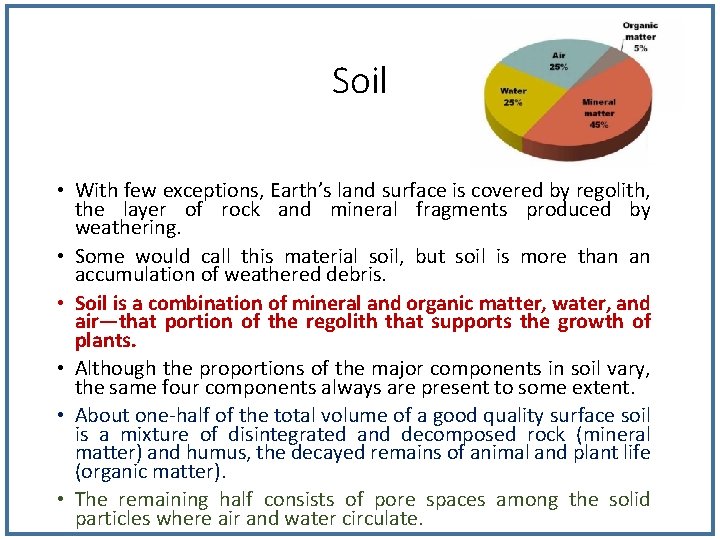

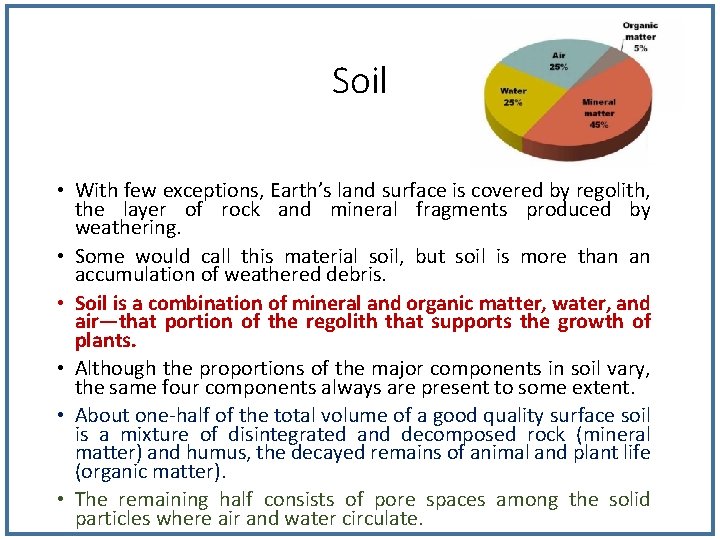

Soil • With few exceptions, Earth’s land surface is covered by regolith, the layer of rock and mineral fragments produced by weathering. • Some would call this material soil, but soil is more than an accumulation of weathered debris. • Soil is a combination of mineral and organic matter, water, and air—that portion of the regolith that supports the growth of plants. • Although the proportions of the major components in soil vary, the same four components always are present to some extent. • About one-half of the total volume of a good quality surface soil is a mixture of disintegrated and decomposed rock (mineral matter) and humus, the decayed remains of animal and plant life (organic matter). • The remaining half consists of pore spaces among the solid particles where air and water circulate.

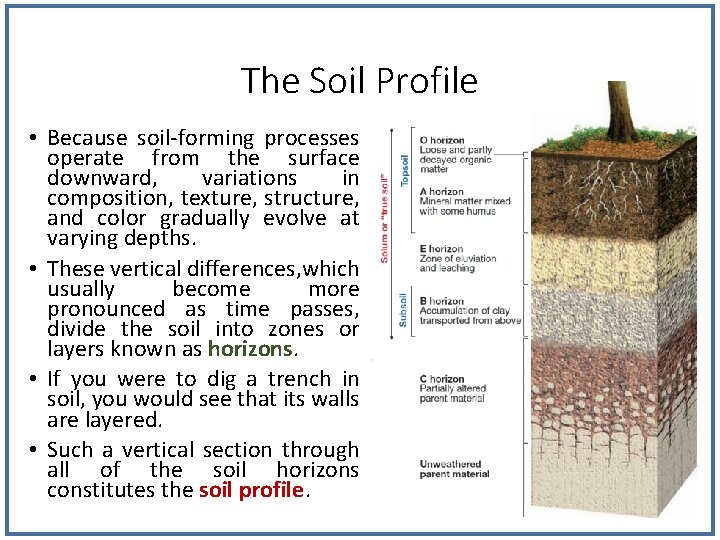

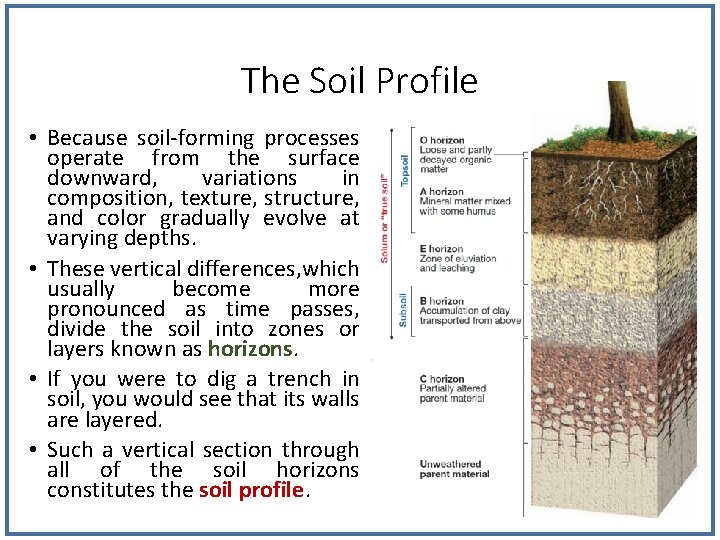

The Soil Profile • Because soil-forming processes operate from the surface downward, variations in composition, texture, structure, and color gradually evolve at varying depths. • These vertical differences, which usually become more pronounced as time passes, divide the soil into zones or layers known as horizons. • If you were to dig a trench in soil, you would see that its walls are layered. • Such a vertical section through all of the soil horizons constitutes the soil profile.

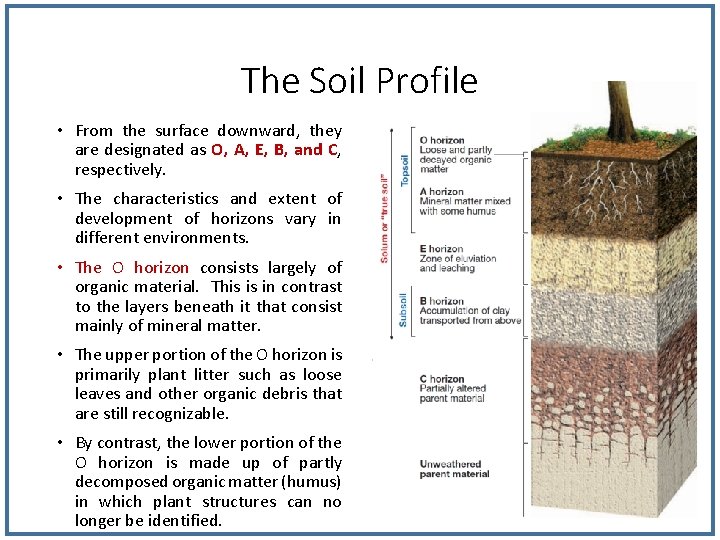

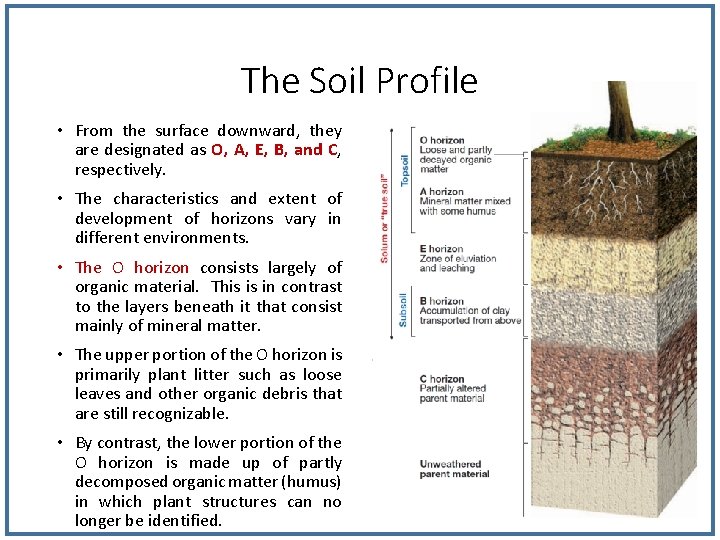

The Soil Profile • From the surface downward, they are designated as O, A, E, B, and C, respectively. • The characteristics and extent of development of horizons vary in different environments. • The O horizon consists largely of organic material. This is in contrast to the layers beneath it that consist mainly of mineral matter. • The upper portion of the O horizon is primarily plant litter such as loose leaves and other organic debris that are still recognizable. • By contrast, the lower portion of the O horizon is made up of partly decomposed organic matter (humus) in which plant structures can no longer be identified.

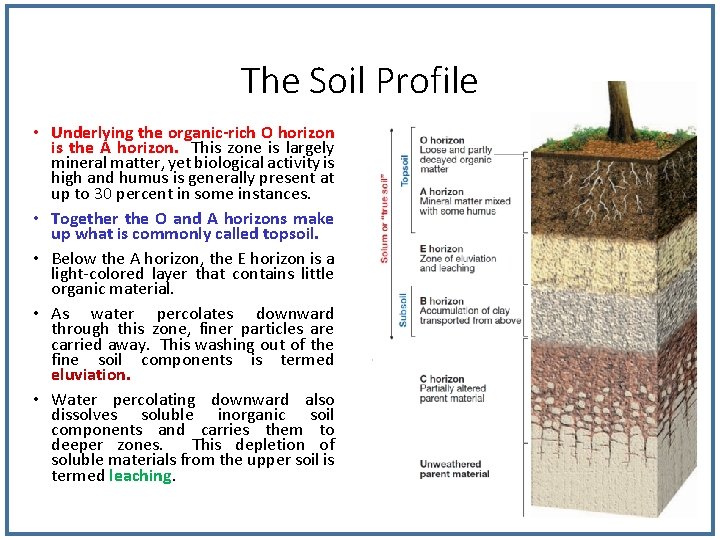

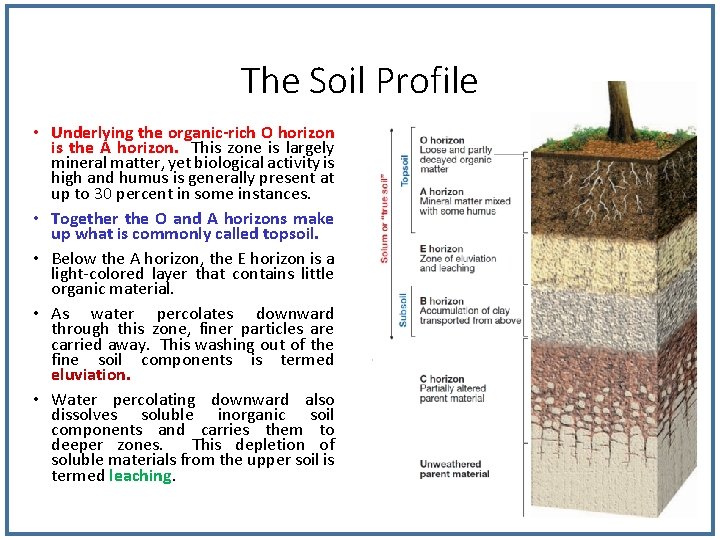

The Soil Profile • Underlying the organic-rich O horizon is the A horizon. This zone is largely mineral matter, yet biological activity is high and humus is generally present at up to 30 percent in some instances. • Together the O and A horizons make up what is commonly called topsoil. • Below the A horizon, the E horizon is a light-colored layer that contains little organic material. • As water percolates downward through this zone, finer particles are carried away. This washing out of the fine soil components is termed eluviation. • Water percolating downward also dissolves soluble inorganic soil components and carries them to deeper zones. This depletion of soluble materials from the upper soil is termed leaching.

The Soil Profile • Immediately below the E horizon is the B horizon, or subsoil. Much of the material removed from the E horizon by eluviation is deposited in the B horizon, which is often referred to as the zone of accumulation. • The O, A, E, and B horizons together constitute the solum, or true soil. • It is in the solum that the soil-forming processes are active and that living roots and other plant and animal life are largely confined. • Below the solum and above the unaltered parent material is the C horizon, a layer characterized by partially altered parent material. • Whereas the O, A, E, and B horizons bear little resemblance to the parent material, it is easily identifiable in the C horizon. • Although this material is undergoing changes that will eventually transform it into soil, it has not yet crossed the threshold that separates regolith from soil.

WEATHERING PRODUCTS: LANDFORMS • Bare rock is exposed in many landscapes. • It results from the differential weathering of bedrock and the removal of weathered debris by slope processes. • Two groups of weathering landforms associated with bare rock in weathering-limited environments are • large-scale cliffs and pillars • smaller-scale rock-basins, tafoni, and honeycombs

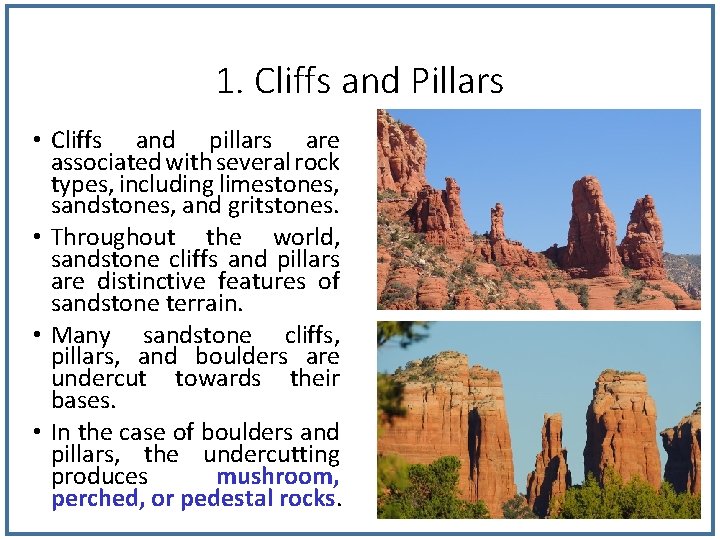

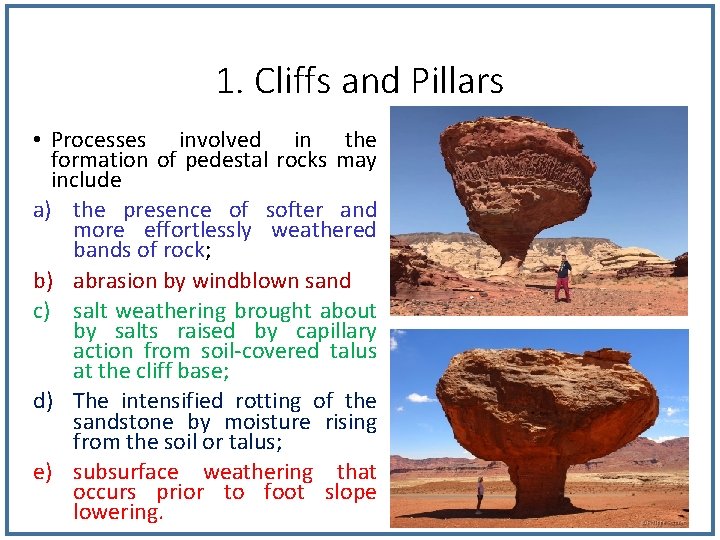

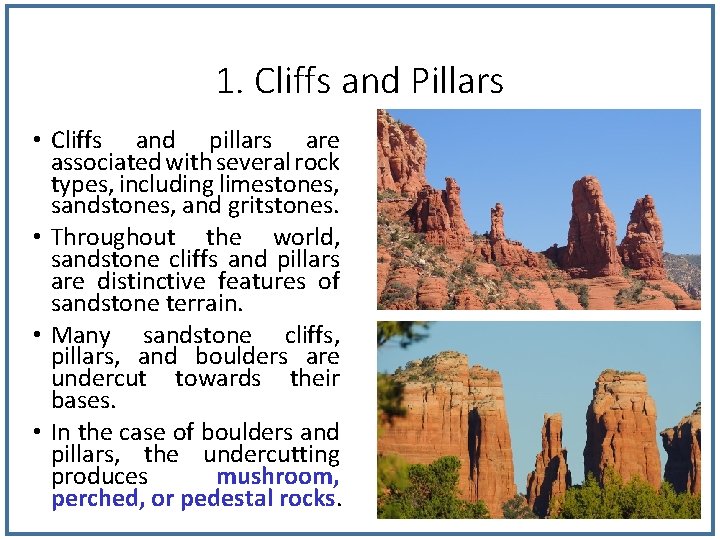

1. Cliffs and Pillars • Cliffs and pillars are associated with several rock types, including limestones, sandstones, and gritstones. • Throughout the world, sandstone cliffs and pillars are distinctive features of sandstone terrain. • Many sandstone cliffs, pillars, and boulders are undercut towards their bases. • In the case of boulders and pillars, the undercutting produces mushroom, perched, or pedestal rocks.

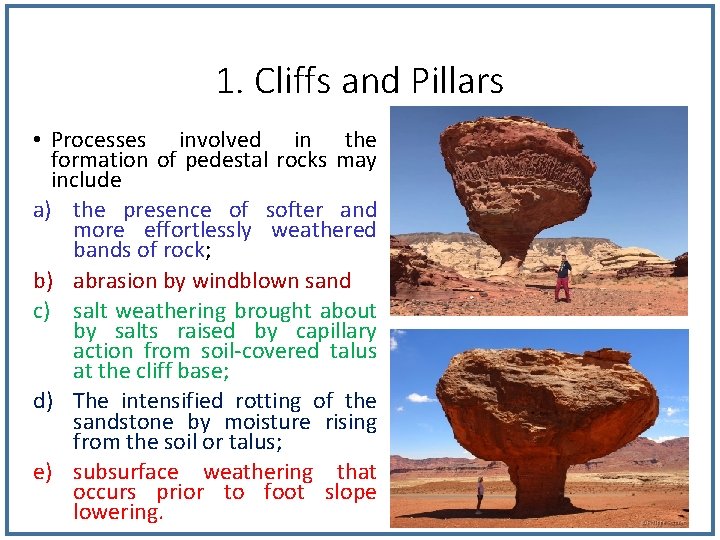

1. Cliffs and Pillars • Processes involved in the formation of pedestal rocks may include a) the presence of softer and more effortlessly weathered bands of rock; b) abrasion by windblown sand c) salt weathering brought about by salts raised by capillary action from soil-covered talus at the cliff base; d) The intensified rotting of the sandstone by moisture rising from the soil or talus; e) subsurface weathering that occurs prior to foot slope lowering.

2. Rock-basins, tafoni, and honeycombs • Virtually all exposed rock outcrops bear irregular surfaces that seem to result from weathering. • Flutes and runnels, pits and cavernous forms are common on all rock types in all climates. • They are most apparent in arid and semi-arid environments, mainly because these environments have a greater area of bare rock surfaces. • They usually find their fullest development on limestone but occur on, for example, granite.

2. Rock-basins, tafoni, and honeycombs • Flutes, rills, runnels, grooves, and gutters, as they are variously styled, form on many rock types in many environments. • They may develop a regularly spaced pattern. • Individual rills can be 5– 30 cm deep and 22– 100 cm wide. • Their development on limestone is striking

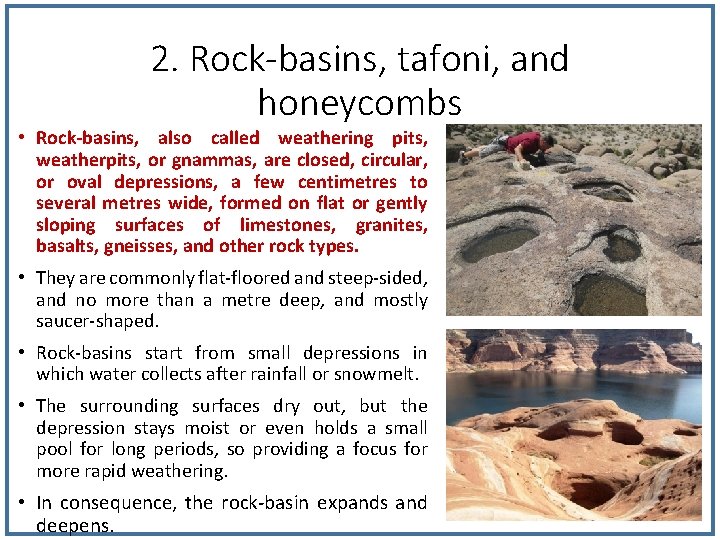

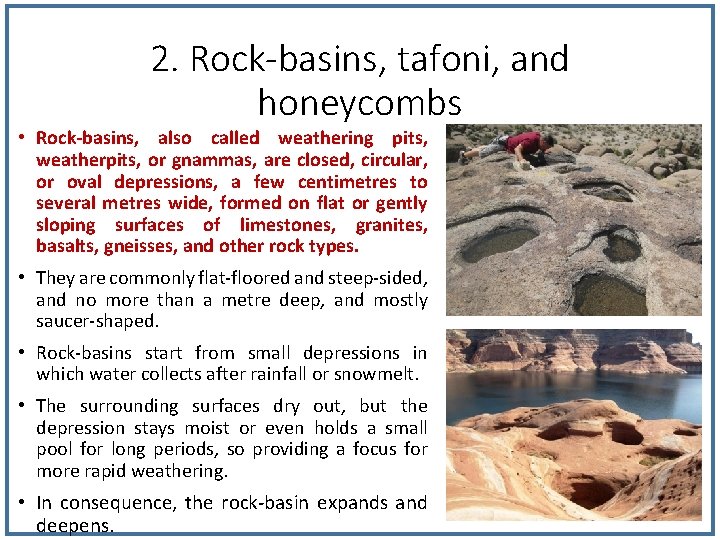

2. Rock-basins, tafoni, and honeycombs • Rock-basins, also called weathering pits, weatherpits, or gnammas, are closed, circular, or oval depressions, a few centimetres to several metres wide, formed on flat or gently sloping surfaces of limestones, granites, basalts, gneisses, and other rock types. • They are commonly flat-floored and steep-sided, and no more than a metre deep, and mostly saucer-shaped. • Rock-basins start from small depressions in which water collects after rainfall or snowmelt. • The surrounding surfaces dry out, but the depression stays moist or even holds a small pool for long periods, so providing a focus for more rapid weathering. • In consequence, the rock-basin expands and deepens.

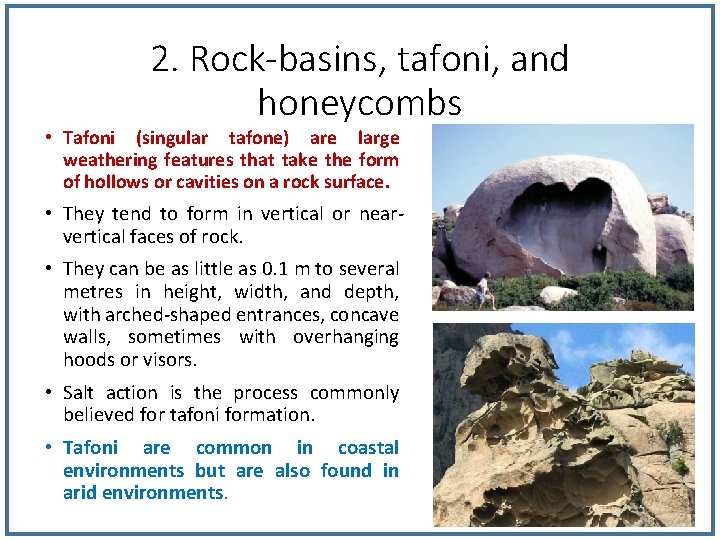

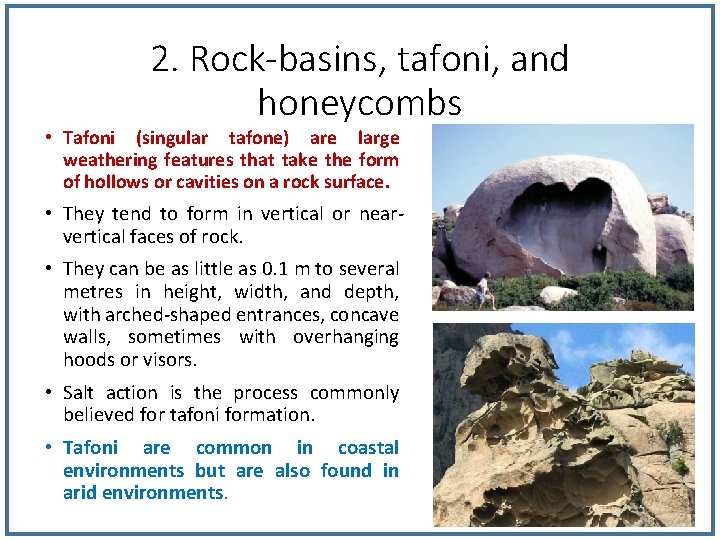

2. Rock-basins, tafoni, and honeycombs • Tafoni (singular tafone) are large weathering features that take the form of hollows or cavities on a rock surface. • They tend to form in vertical or nearvertical faces of rock. • They can be as little as 0. 1 m to several metres in height, width, and depth, with arched-shaped entrances, concave walls, sometimes with overhanging hoods or visors. • Salt action is the process commonly believed for tafoni formation. • Tafoni are common in coastal environments but are also found in arid environments.

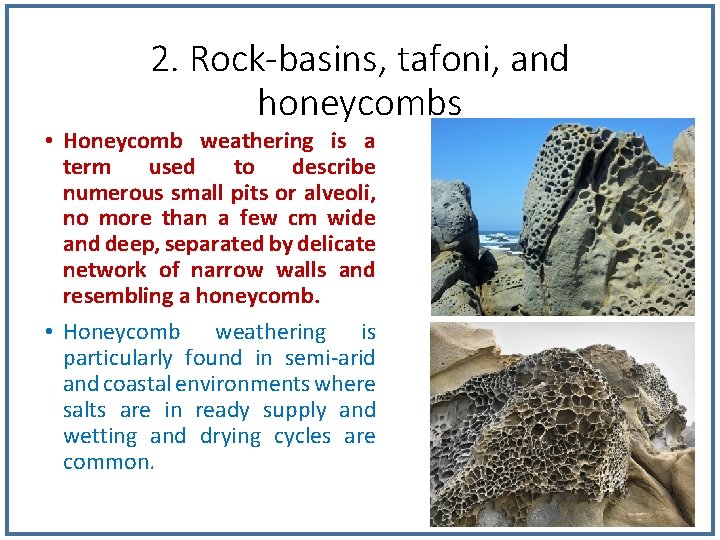

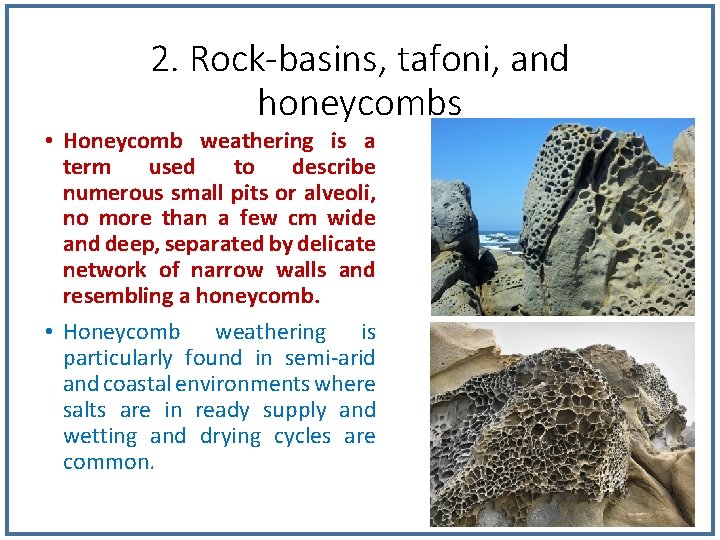

2. Rock-basins, tafoni, and honeycombs • Honeycomb weathering is a term used to describe numerous small pits or alveoli, no more than a few cm wide and deep, separated by delicate network of narrow walls and resembling a honeycomb. • Honeycomb weathering is particularly found in semi-arid and coastal environments where salts are in ready supply and wetting and drying cycles are common.

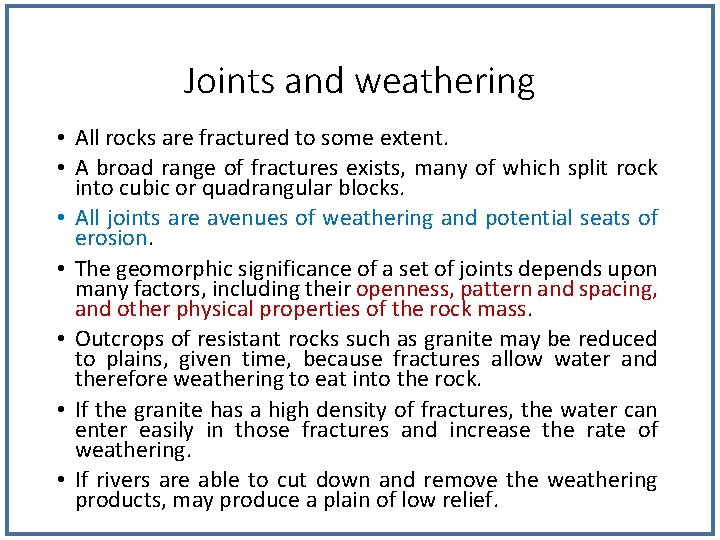

Joints and weathering • All rocks are fractured to some extent. • A broad range of fractures exists, many of which split rock into cubic or quadrangular blocks. • All joints are avenues of weathering and potential seats of erosion. • The geomorphic significance of a set of joints depends upon many factors, including their openness, pattern and spacing, and other physical properties of the rock mass. • Outcrops of resistant rocks such as granite may be reduced to plains, given time, because fractures allow water and therefore weathering to eat into the rock. • If the granite has a high density of fractures, the water can enter easily in those fractures and increase the rate of weathering. • If rivers are able to cut down and remove the weathering products, may produce a plain of low relief.

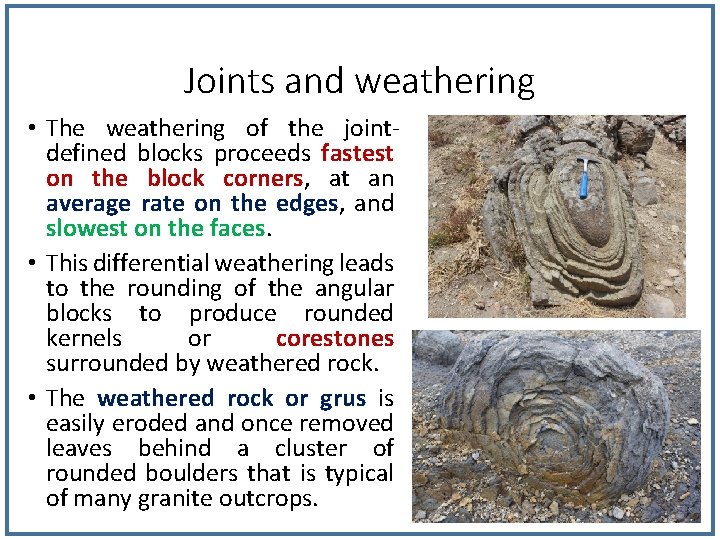

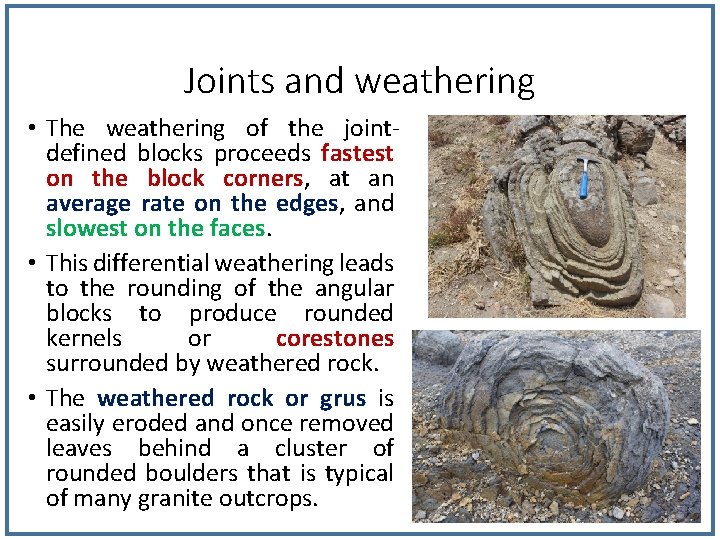

Joints and weathering • The weathering of the jointdefined blocks proceeds fastest on the block corners, at an average rate on the edges, and slowest on the faces. • This differential weathering leads to the rounding of the angular blocks to produce rounded kernels or corestones surrounded by weathered rock. • The weathered rock or grus is easily eroded and once removed leaves behind a cluster of rounded boulders that is typical of many granite outcrops.

Joints and weathering • Tors, which are outcrops of rock that stand out on all sides from the surrounding slopes. • They are common on crystalline rocks, but are known to occur on other resistant rock types, including quartzites and some sandstones. • Some geomorphologists claim that deep weathering is a prerequisite for tor formation.

Rates of Weathering (Rock Characteristics) • Several factors influence the type and rate of rock weathering. • Rock characteristics encompass all of the chemical traits of rocks, including mineral composition and solubility. • In addition, any physical features such as joints (cracks) can be important because they allow water to penetrate rock and start the process of weathering long before the rock is exposed. • The silicates, the most abundant mineral group, weather in essentially the same order as their order of crystallization. • By examining Bowen’s reaction series, you can see that olivine crystallizes first and is therefore the least resistant to chemical weathering, whereas quartz, which crystallizes last, is the most resistant.

Rates of Weathering (Climate) • Climatic factors, particularly temperature and moisture, are crucial to the rate of rock weathering. • One important example from mechanical weathering is that the frequency of freeze–thaw cycles greatly affects the amount of frost wedging. • Temperature and moisture also exert a strong influence on rates of chemical weathering and on the kind amount of vegetation present. • Regions with lush vegetation generally have a thick mantle of soil rich in decayed organic matter from which chemically active fluids such as carbonic and humic acids are derived. • The optimal environment for chemical weathering is a combination of warm temperatures and abundant moisture. • In polar regions chemical weathering is ineffective because frigid temperatures keep the available moisture locked up as ice, whereas in arid regions there is insufficient moisture to foster rapid chemical weathering. • Human activities can influence the composition of the atmosphere, which in turn can impact the rate of chemical weathering. One well-known example is acid rain.

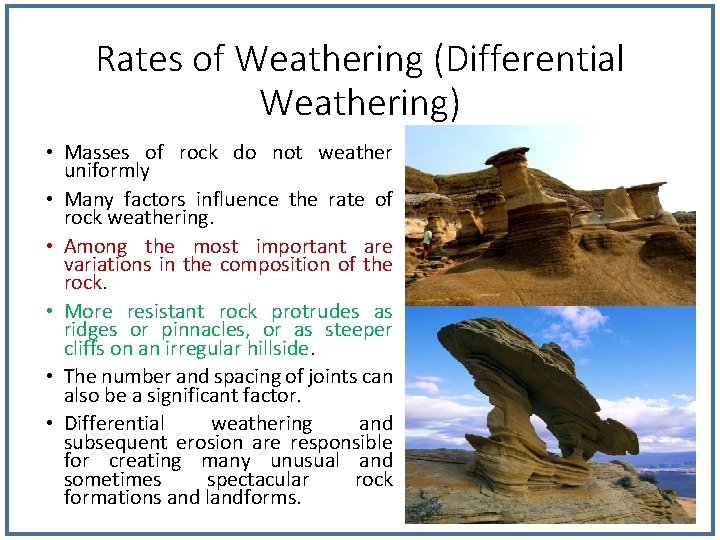

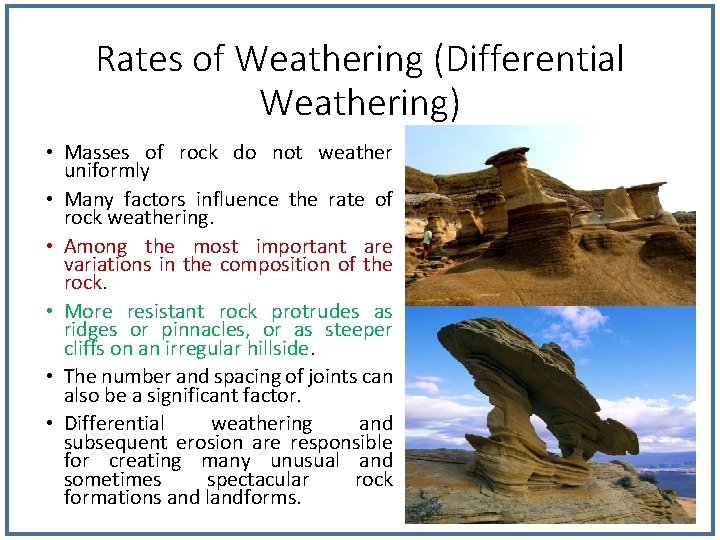

Rates of Weathering (Differential Weathering) • Masses of rock do not weather uniformly • Many factors influence the rate of rock weathering. • Among the most important are variations in the composition of the rock. • More resistant rock protrudes as ridges or pinnacles, or as steeper cliffs on an irregular hillside. • The number and spacing of joints can also be a significant factor. • Differential weathering and subsequent erosion are responsible for creating many unusual and sometimes spectacular rock formations and landforms.