Understanding assistive technology research from different models of

- Slides: 55

Understanding assistive technology research from different models of disabilities 黃宜君 英國里茲大學教育學院 哲學博士

Structure of presentation • Models of disability - The medical model of disability - The social model of disability - The biopsychosocial model of disability • Assistive technology research - The functional approach - The psychosocial approach - Research into device use or non-use - Outcome research • Study: The usability of assistive devices for children with cerebral palsy in Taiwan

英國特教制度 • 1960年代後期 到 1970年代 : - Social model of disability • 1978年 Warnock Report - 家長壓力 - Statement - 不以障礙類別定義服務對象

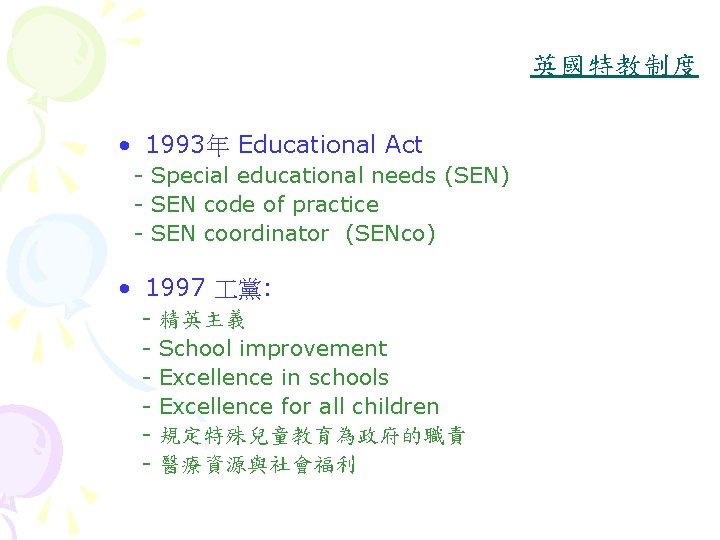

英國特教制度 • 1993年 Educational Act - Special educational needs (SEN) - SEN code of practice - SEN coordinator (SENco) • 1997 黨: - 精英主義 School improvement Excellence in schools Excellence for all children 規定特殊兒童教育為政府的職責 醫療資源與社會福利

Different models of disabilities

Context of the medical model of disability • Disability has traditionally been viewed as unfortunate, stigma or personal tragedy that happens at random to unlucky individuals • Disabled people are perceived as less function, less value and being incapable of achieving a perfect life • Public’s fear of disability and regarding disability as a social deviance

Context of the social model of disability • During the late 1960 s and early 1970 s • Proposed by a group of disabled scholars and activists in the Union of the Physically Impaired Against Segregation (UPIAS), like Vic Finkelstein, Mike Oliver and Colin Barnes • Extended later to the Disabled People’s International

The medical model of disability

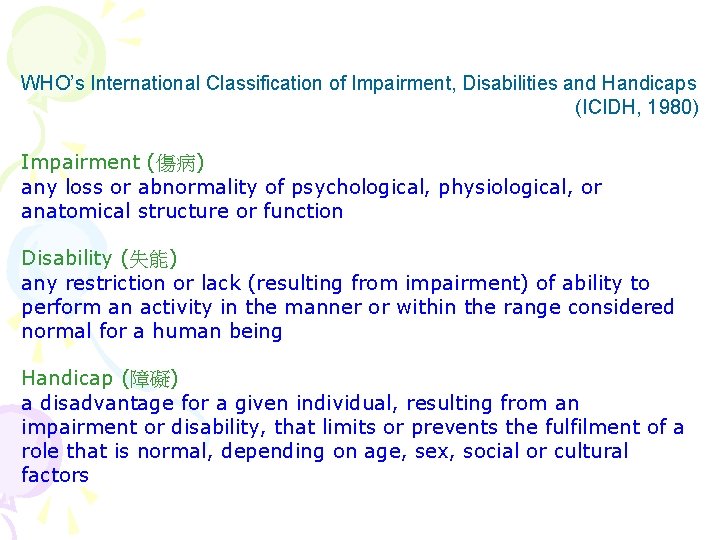

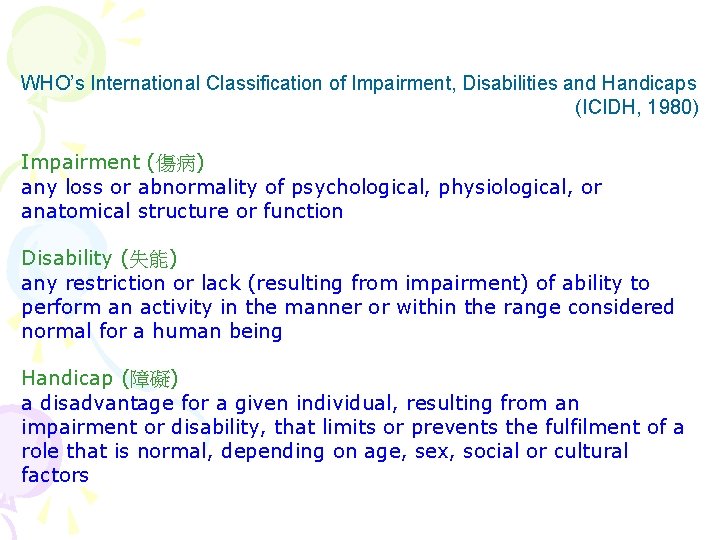

WHO’s International Classification of Impairment, Disabilities and Handicaps (ICIDH, 1980) Impairment (傷病) any loss or abnormality of psychological, physiological, or anatomical structure or function Disability (失能) any restriction or lack (resulting from impairment) of ability to perform an activity in the manner or within the range considered normal for a human being Handicap (障礙) a disadvantage for a given individual, resulting from an impairment or disability, that limits or prevents the fulfilment of a role that is normal, depending on age, sex, social or cultural factors

• Assumes that an abnormality exists in the disabled individual’s body, caused directly by the impairment • In order to effectively resolve the individual’s impairment, medical intervention is important and unavoidable • Adopts an individual approach and emphasises the importance of medical treatment

The limitations of the medical model of disability • The causality between impairment, disability and handicap • Medical intervention has nothing to do with individuals’ social problems, e. g. environmental barriers, unequal opportunities or social oppression • Neglect individuals’ psychological factors and environmental factors • Orientated people with disability in a passive role • Negative terms adopted expand the public’s fear of disability or lead them to a negative impression of disability

The social model of disability

• Define disability in a social context • Although impairment causes the individual’s functional limitations, it is society that makes people with impairment “abnormal” and leads to their “tragedy” • Disability stems from social disadvantages or oppression in which disabled people are marginalised, discriminated against and disempowered

The definitions of impairment and disability defined by the UPIAS (1976): Impairment lacking all or part of a limb, or having a defective limb, organ or mechanism of the body Disability the disadvantage or restriction of activity caused by a contemporary social organization which takes no or little account of people who have physical impairments and thus excludes them from the mainstream of social activities

• Since the problem that causes disability is located within the society, the way to eliminate disability is social change where discrimination and barriers can be removed and disabled people’s rights can be protected • Adopts a social-political perspective • Its ultimate goal is to build a fully integrated society which encompasses all individuals whose diverse needs are all taken into account

The limitations of the social model of disability • Focus too exclusively on socio-structural aspects and ignores the influences caused by impairment. In particular, it neglects how disabled people live with their impairment on a daily basis • The lack of an individual approach may cause this model difficulties in dealing with each person’s different needs • Less consider the psychological issues that disabled people must face

Disability research • Emancipatory research (Influenced by the feminist research) • The adoption of the social model of disability as its theoretical basis for research production • The devolution of control over of research production to ensure full accountability to disabled people and their organisations • The endeavour to break an asymmetric relationship between the researcher and participants

The psychological model of disability

Finkelstein and French, based on the spirit of WHO’s definitions, state psychological aspects of impairment and disability: • Psychological aspects of impairment the ways in which a person responds to and copes with his or her impairment can never be divorced from the individual’s personality, social situation and personal biography • Psychological aspects of disability disabled people may feel negative and depressed about their situation because they have absorbed negative attitude about disability both before and after becoming disabled, and much of the depression and anxiety they feel may be the result of social factors such as people’s attitudes, poor access, non-existent job prospects and poverty

The limitations of the psychological model of disability • Its approach is also directly related to the impairment. The drawbacks of the medical model, such as the causal link and the focus of abnormality, can be seen again here • This standpoint merely discusses the negative feeling of disability, and lacks to offer the positive side of managing and coping with it

The biopsychosocial model of disability

• Is based on an integration of the medical and social models • Is underpinned by the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF), published in 2001 by WHO

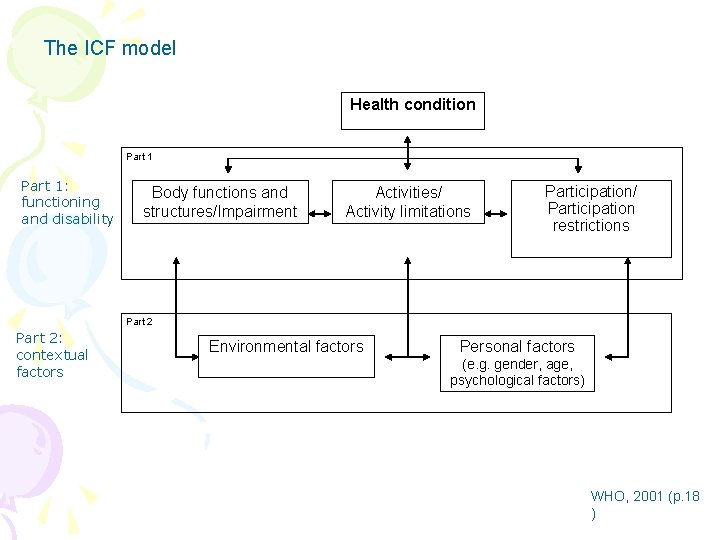

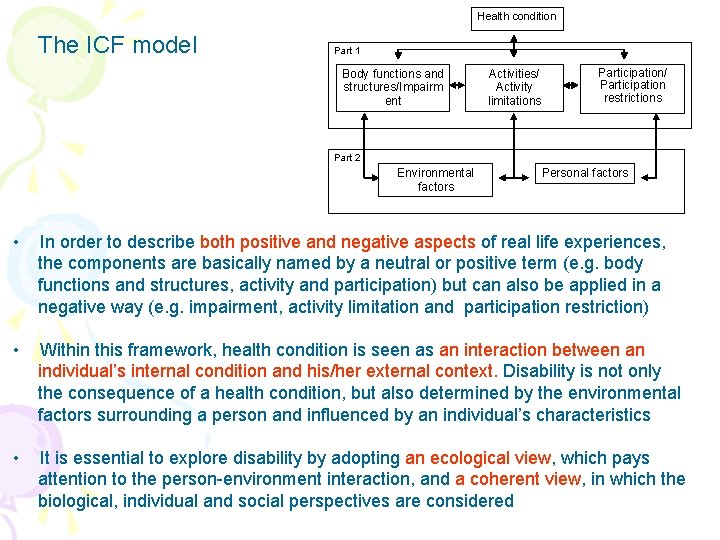

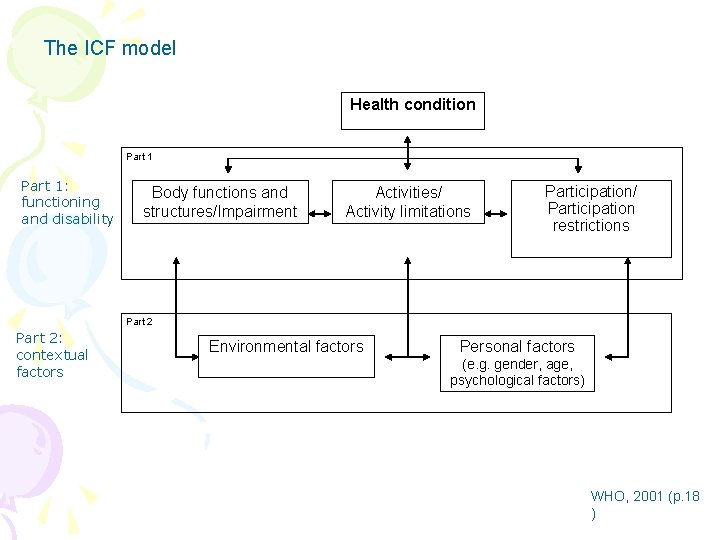

The ICF model Health condition Part 1: functioning and disability Body functions and structures/Impairment Activities/ Activity limitations Participation/ Participation restrictions Part 2: contextual factors Environmental factors Personal factors (e. g. gender, age, psychological factors) WHO, 2001 (p. 18 )

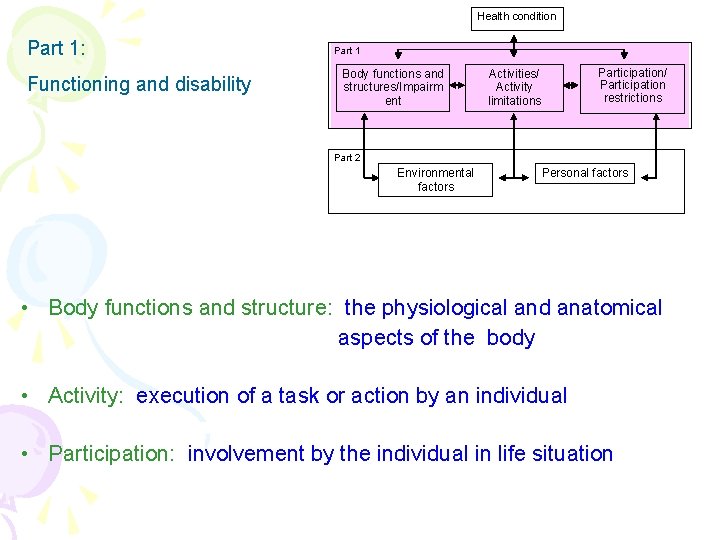

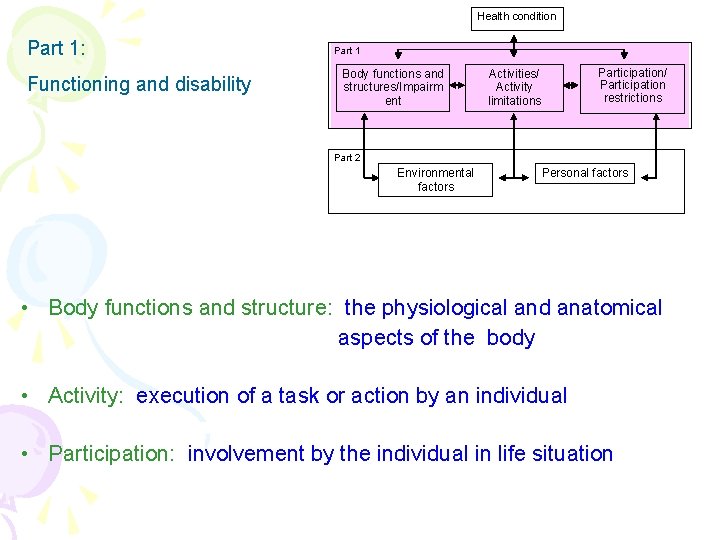

Health condition Part 1: Functioning and disability Part 1 Body functions and structures/Impairm ent Participation/ Participation restrictions Activities/ Activity limitations Part 2 Environmental factors Personal factors • Body functions and structure: the physiological and anatomical aspects of the body • Activity: execution of a task or action by an individual • Participation: involvement by the individual in life situation

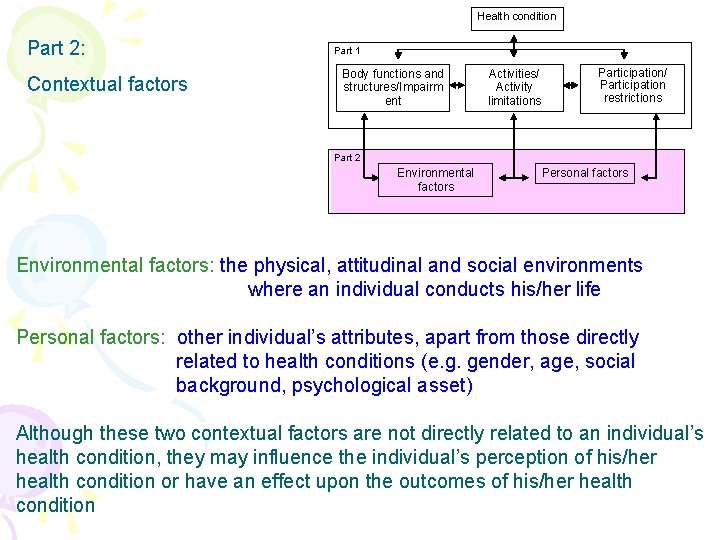

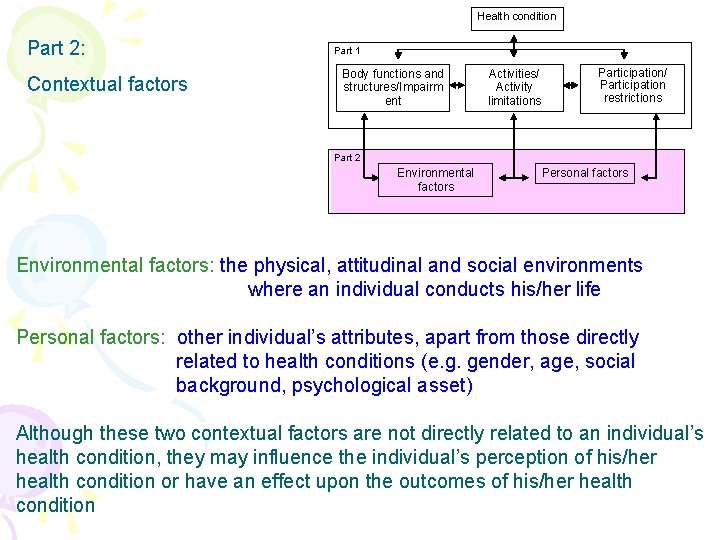

Health condition Part 2: Contextual factors Part 1 Body functions and structures/Impairm ent Activities/ Activity limitations Participation/ Participation restrictions Part 2 Environmental factors Personal factors Environmental factors: the physical, attitudinal and social environments where an individual conducts his/her life Personal factors: other individual’s attributes, apart from those directly related to health conditions (e. g. gender, age, social background, psychological asset) Although these two contextual factors are not directly related to an individual’s health condition, they may influence the individual’s perception of his/her health condition or have an effect upon the outcomes of his/her health condition

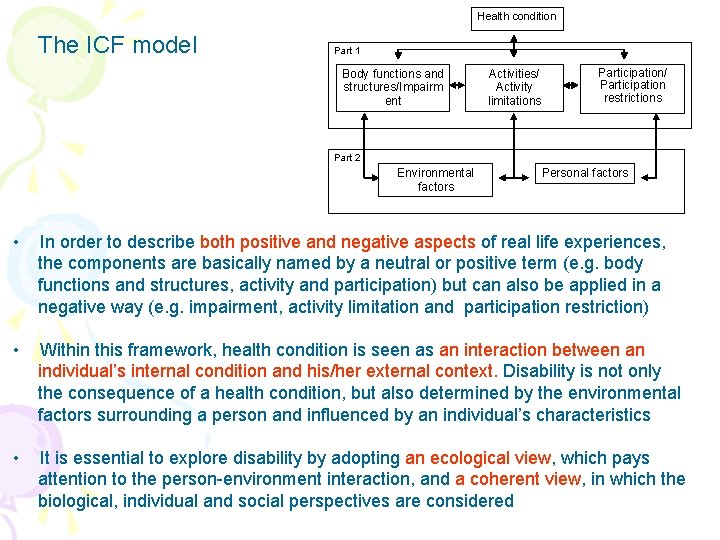

Health condition The ICF model Part 1 Body functions and structures/Impairm ent Activities/ Activity limitations Participation/ Participation restrictions Part 2 Environmental factors Personal factors • In order to describe both positive and negative aspects of real life experiences, the components are basically named by a neutral or positive term (e. g. body functions and structures, activity and participation) but can also be applied in a negative way (e. g. impairment, activity limitation and participation restriction) • Within this framework, health condition is seen as an interaction between an individual’s internal condition and his/her external context. Disability is not only the consequence of a health condition, but also determined by the environmental factors surrounding a person and influenced by an individual’s characteristics • It is essential to explore disability by adopting an ecological view, which pays attention to the person-environment interaction, and a coherent view, in which the biological, individual and social perspectives are considered

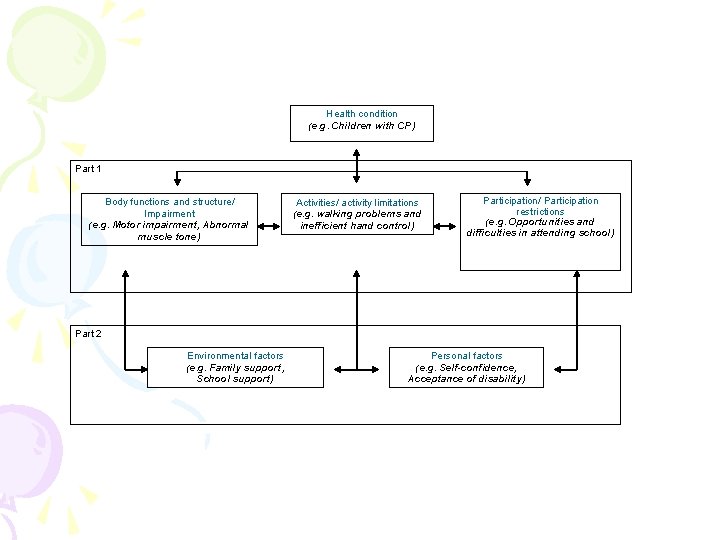

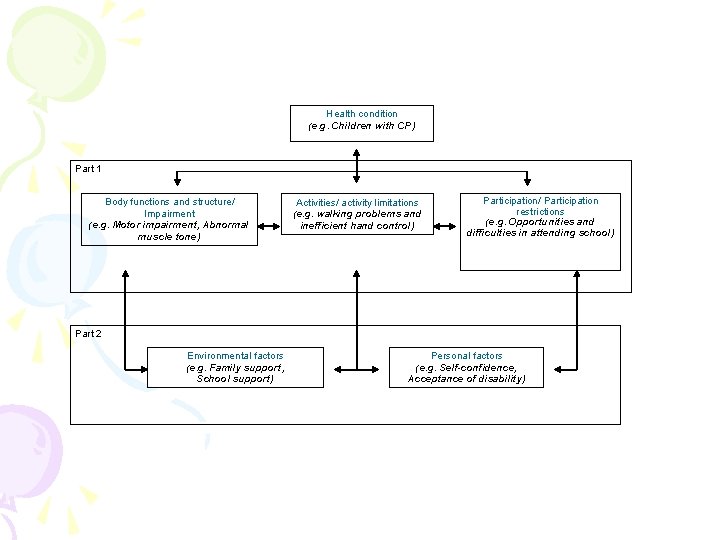

Health condition (e. g. Children with CP) Part 1 Body functions and structure/ Impairment (e. g. Motor impairment, Abnormal muscle tone) Activities/ activity limitations (e. g. walking problems and inefficient hand control) Participation/ Participation restrictions (e. g. Opportunities and difficulties in attending school) Part 2 Environmental factors (e. g. Family support, School support) Personal factors (e. g. Self-confidence, Acceptance of disability)

Assistive technology devices

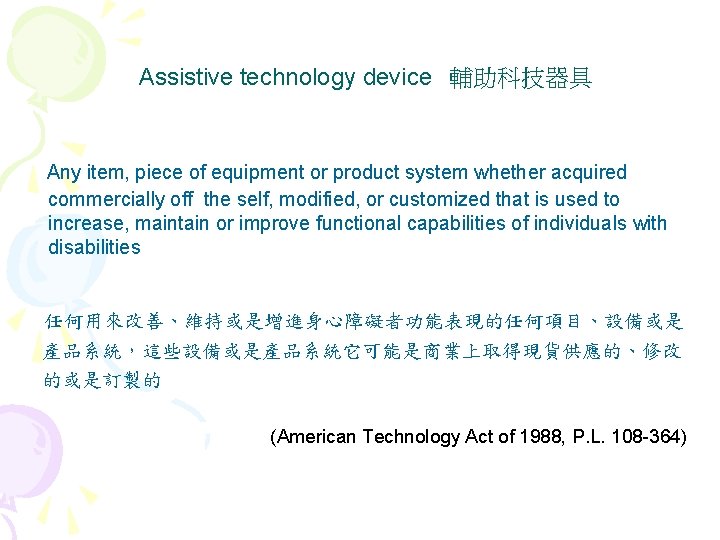

Assistive technology device 輔助科技器具 Any item, piece of equipment or product system whether acquired commercially off the self, modified, or customized that is used to increase, maintain or improve functional capabilities of individuals with disabilities 任何用來改善、維持或是增進身心障礙者功能表現的任何項目、設備或是 產品系統,這些設備或是產品系統它可能是商業上取得現貨供應的、修改 的或是訂製的 (American Technology Act of 1988, P. L. 108 -364)

Assistive technology devices - Tools designed to improve disabled people’s physical functioning or reduce the environmental barriers that impede these people’s achievement, subsequently increasing their independence, participation opportunities and quality of life - Range from low -tech or simple devices (e. g. walkers or pencil grips) to high-tech ones (e. g. power wheelchairs or computerised communication systems) - (Scherer, 2002)

The functional approach • Focus on device effectiveness in improving device users’ functioning • View device function and users’ physical performance as the major concern • Reflect the impairment-treatment orientation of the medical model of disability

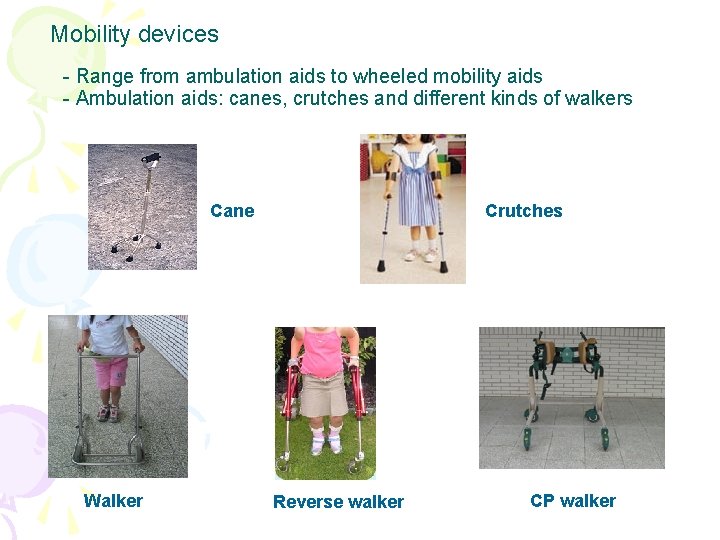

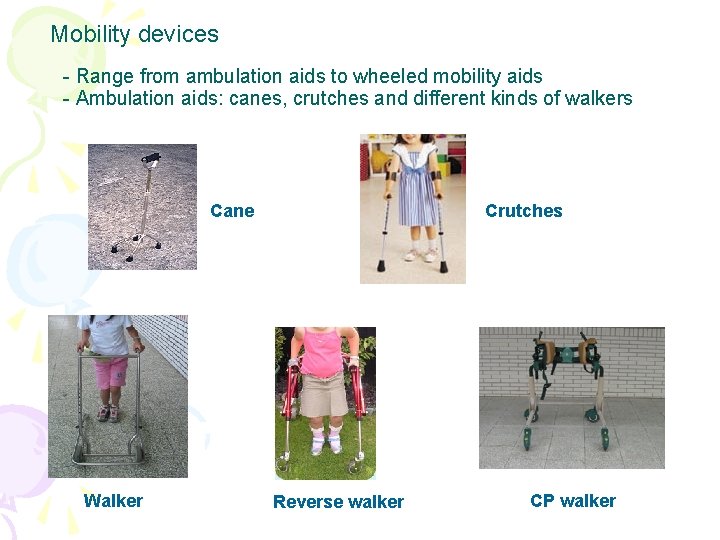

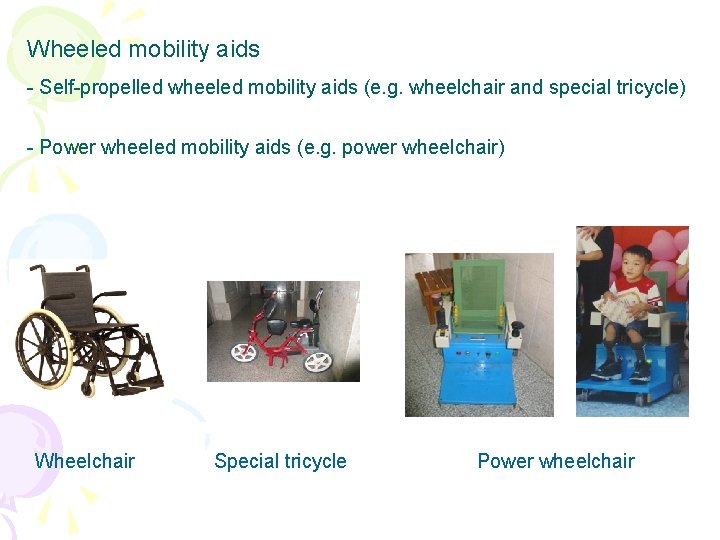

Mobility devices - Range from ambulation aids to wheeled mobility aids - Ambulation aids: canes, crutches and different kinds of walkers Cane Walker Crutches Reverse walker CP walker

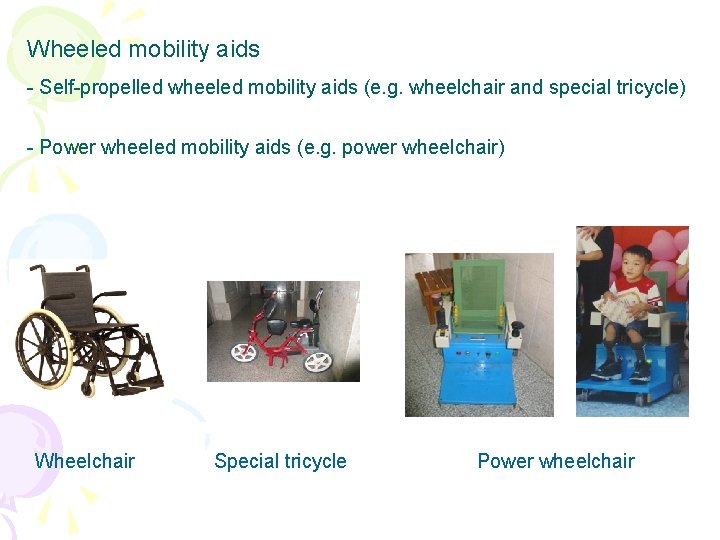

Wheeled mobility aids - Self-propelled wheeled mobility aids (e. g. wheelchair and special tricycle) - Power wheeled mobility aids (e. g. power wheelchair) Wheelchair Special tricycle Power wheelchair

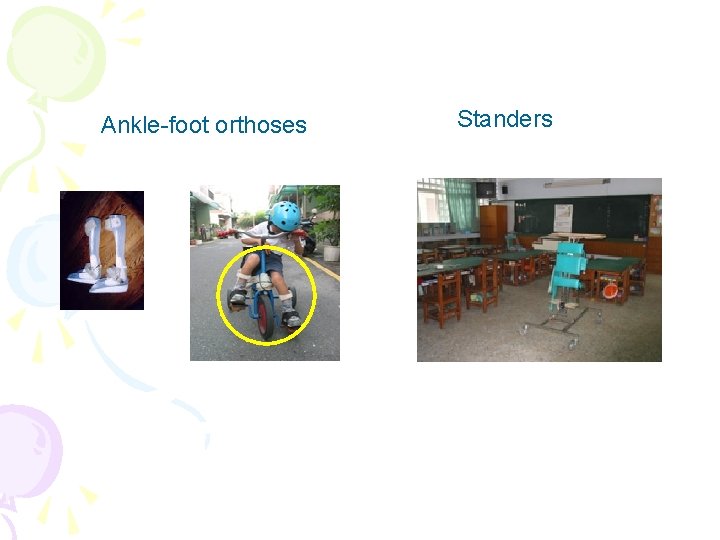

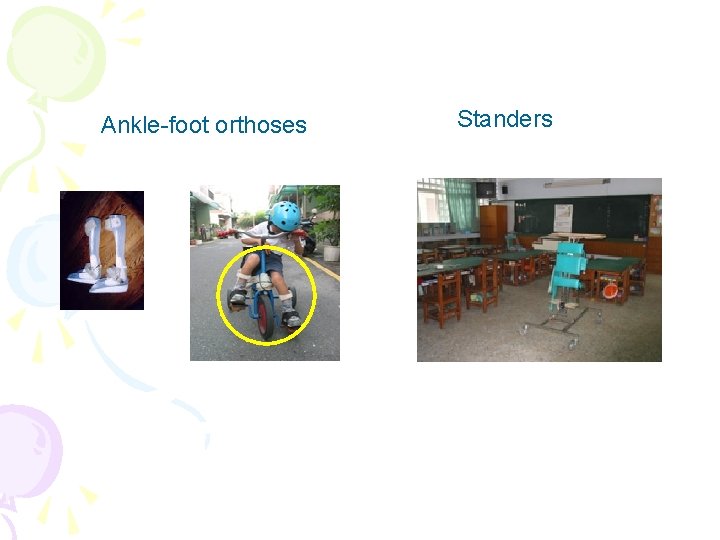

Ankle-foot orthoses Standers

The limitations of the functional approach • View device function as a priority but neglect other issues that also exist in the user-device interaction (e. g. cost, follow-up maintenance or aesthetic concerns) • Lack consideration of the users’ perspectives and overlook the influence of device use from psychological or socio-cultural perspectives (e. g. users’ willingness or others’ acceptance)

The psychosocial approach • Shift focus from assistive devices to device users • Pay attention to the users’ psychosocial consequences of adopting devices

Psychological concerns • See their devices as an extension of their body, not just a mechanical aid • The way users perceive their devices is related to the feelings they have about their disabilities • View assistive devices as a tangible reminder of their disability • The adoption of assistive devices tends to involve the users’ concern for their self-concept or self-identity and accordingly becomes a complicated and sensitive issue for them • Since assistive devices are designed specifically for disability, the stereotype of disability (e. g. symbol of loss, inability) is easily reflected by them (Barber, 1996 ; Covington, 1998; Hocking, 1999)

Social concerns • Owing to the visible nature of assistive devices, device users may have social concerns in their usage • ADs have the function of clarifying the users’ disabilities. It is generally assumed that people who use assistive devices have authentic disabling conditions • Device usage triggers a shared understanding of disability and conveys some information relevant to the users’ impairments (e. g. sunglasses for blindness and crutches for walking problems) • The mass media often carries the message that the use of an AD implies that the entire person is different, not only one aspect of that person’s functioning

Social concerns • Due to the negative and stereotypes of disabilities distorted by the media, the public may misunderstand assistive devices and respond by keeping more physical distance, shorter eye contact and briefer conversation time when interacting with the device users in public • Several studies report that non-disabled people tend to feel fearful, anxious, uncomfortable or embarrassed in the presence of a disabled individual. The visibility of the impairment, indicated by device use, can increase their fear • Since disability has never been desirable to anyone, assistive devices are consequently given the negative stereotype associated with disability, such as stigma, ugly appearance or unpleasant characteristics (Brooks, 1990, 1991 and 1998; Lupton and Seymour, 2000)

The limitations of the psychosocial approach • Focus merely on the negative aspects of device use and lack consideration of the positive experiences that device users may have (e. g. developing confidence as the users’ functioning has been improved with the help of assistive devices) • Mainly include the adult users as participants and scarce attention has been paid to young users

Research into device use or nonuse • Some changes to assistive devices in the last three decades (Scherer 1996, 2000, 2002): 1. With better medical service, more people can survive severe trauma and disease but need assistive devices to help them 2. Advances in technology have made assistive devices more lightweight, portable, flexible and durable 3. The social welfare policy in more and more countries includes providing financial support and helping disabled people to get the devices they need - The types of assistive device and the number of people owning assistive devices have gradually increased - At the same time, however, the phenomenon of device abandonment emerges

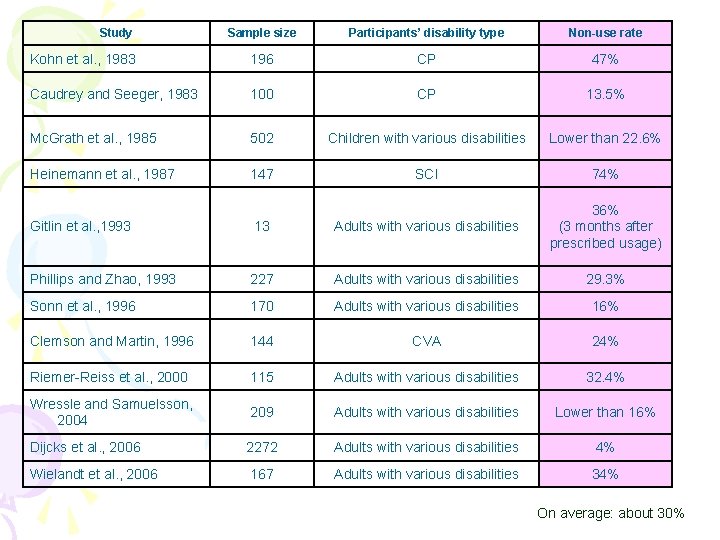

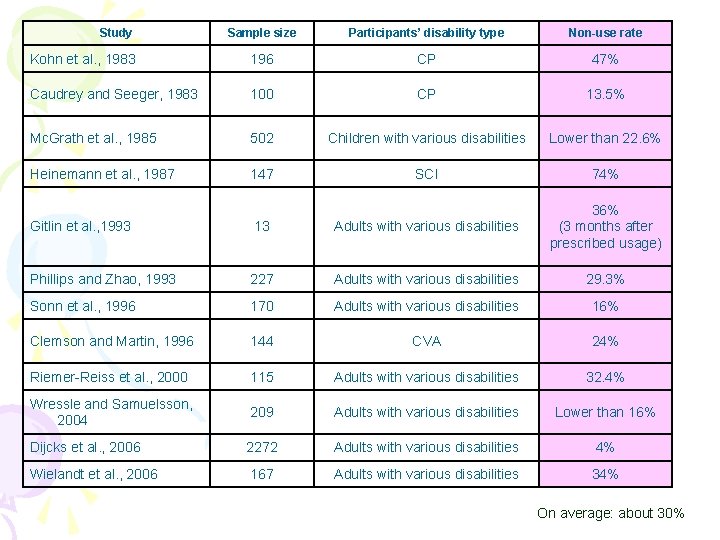

Study Sample size Participants’ disability type Non-use rate Kohn et al. , 1983 196 CP 47% Caudrey and Seeger, 1983 100 CP 13. 5% Mc. Grath et al. , 1985 502 Children with various disabilities Lower than 22. 6% Heinemann et al. , 1987 147 SCI 74% Gitlin et al. , 1993 13 Adults with various disabilities 36% (3 months after prescribed usage) Phillips and Zhao, 1993 227 Adults with various disabilities 29. 3% Sonn et al. , 1996 170 Adults with various disabilities 16% Clemson and Martin, 1996 144 CVA 24% Riemer-Reiss et al. , 2000 115 Adults with various disabilities 32. 4% Wressle and Samuelsson, 2004 209 Adults with various disabilities Lower than 16% Dijcks et al. , 2006 2272 Adults with various disabilities 4% Wielandt et al. , 2006 167 Adults with various disabilities 34% On average: about 30%

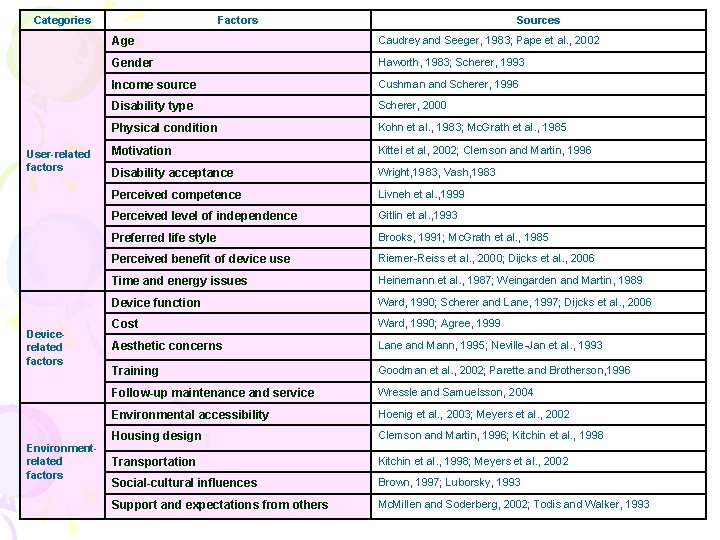

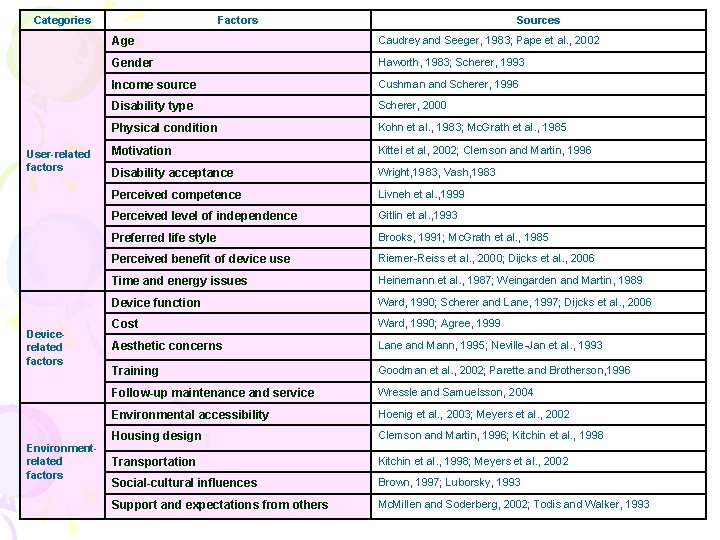

Categories User-related factors Devicerelated factors Environmentrelated factors Factors Sources Age Caudrey and Seeger, 1983; Pape et al. , 2002 Gender Haworth, 1983; Scherer, 1993 Income source Cushman and Scherer, 1996 Disability type Scherer, 2000 Physical condition Kohn et al. , 1983; Mc. Grath et al. , 1985 Motivation Kittel et al, 2002; Clemson and Martin, 1996 Disability acceptance Wright, 1983, Vash, 1983 Perceived competence Livneh et al. , 1999 Perceived level of independence Gitlin et al. , 1993 Preferred life style Brooks, 1991; Mc. Grath et al. , 1985 Perceived benefit of device use Riemer-Reiss et al. , 2000; Dijcks et al. , 2006 Time and energy issues Heinemann et al. , 1987; Weingarden and Martin, 1989 Device function Ward, 1990; Scherer and Lane, 1997; Dijcks et al. , 2006 Cost Ward, 1990; Agree, 1999 Aesthetic concerns Lane and Mann, 1995; Neville-Jan et al. , 1993 Training Goodman et al. , 2002; Parette and Brotherson, 1996 Follow-up maintenance and service Wressle and Samuelsson, 2004 Environmental accessibility Hoenig et al. , 2003; Meyers et al. , 2002 Housing design Clemson and Martin, 1996; Kitchin et al. , 1998 Transportation Kitchin et al. , 1998; Meyers et al. , 2002 Social-cultural influences Brown, 1997; Luborsky, 1993 Support and expectations from others Mc. Millen and Soderberg, 2002; Todis and Walker, 1993

The limitations of research into device use or non-use • Assume that non-use or abandonment is the only outcome when users are dissatisfied with their devices and, accordingly, neglect a consideration of the problems that device users face in their daily lives

Assistive device outcome research • Pay attention to device users’ condition, needs and perspectives • Take an ecological view and explore device usage from the users’ daily situation

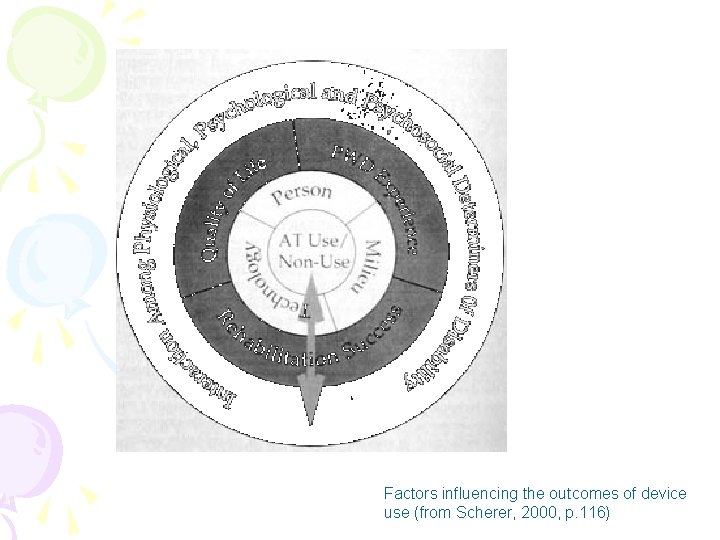

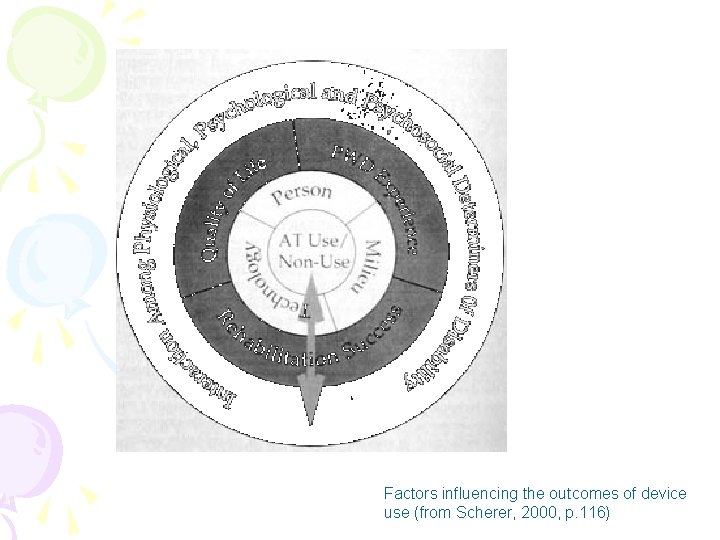

Factors influencing the outcomes of device use (from Scherer, 2000, p. 116)

MPT model (Matching Person and Technology model ) - Scherer (2000) • Three main components influencing the outcome of device use - The characteristics of the environment where the assistive device is used - The features of the user’s personality, temperament, and preference - The attributes of the assistive device itself

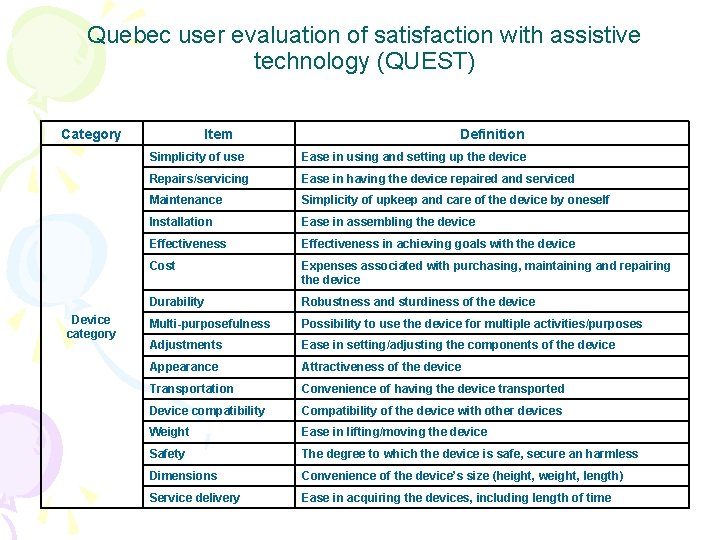

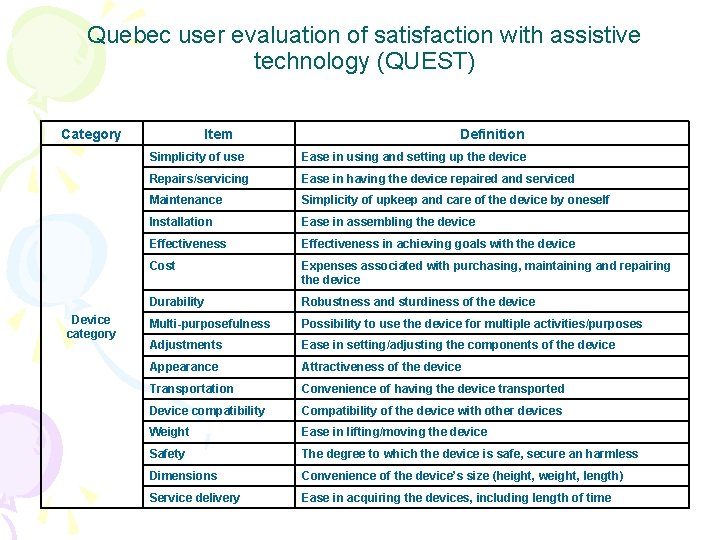

Quebec user evaluation of satisfaction with assistive technology (QUEST) Category Device category Item Definition Simplicity of use Ease in using and setting up the device Repairs/servicing Ease in having the device repaired and serviced Maintenance Simplicity of upkeep and care of the device by oneself Installation Ease in assembling the device Effectiveness in achieving goals with the device Cost Expenses associated with purchasing, maintaining and repairing the device Durability Robustness and sturdiness of the device Multi-purposefulness Possibility to use the device for multiple activities/purposes Adjustments Ease in setting/adjusting the components of the device Appearance Attractiveness of the device Transportation Convenience of having the device transported Device compatibility Compatibility of the device with other devices Weight Ease in lifting/moving the device Safety The degree to which the device is safe, secure an harmless Dimensions Convenience of the device’s size (height, weight, length) Service delivery Ease in acquiring the devices, including length of time

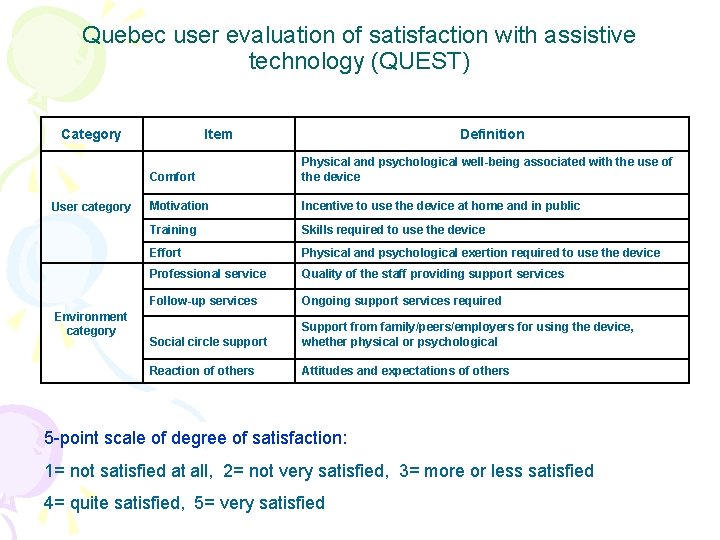

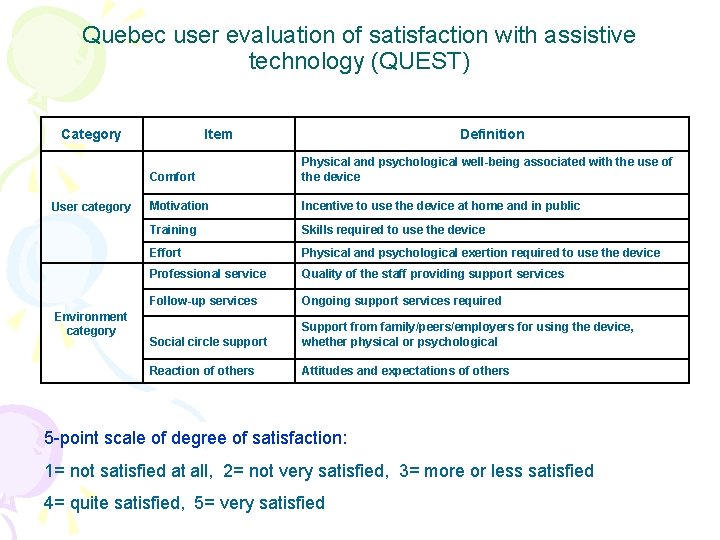

Quebec user evaluation of satisfaction with assistive technology (QUEST) Category User category Environment category Item Definition Comfort Physical and psychological well-being associated with the use of the device Motivation Incentive to use the device at home and in public Training Skills required to use the device Effort Physical and psychological exertion required to use the device Professional service Quality of the staff providing support services Follow-up services Ongoing support services required Social circle support Support from family/peers/employers for using the device, whether physical or psychological Reaction of others Attitudes and expectations of others 5 -point scale of degree of satisfaction: 1= not satisfied at all, 2= not very satisfied, 3= more or less satisfied 4= quite satisfied, 5= very satisfied

Quebec user evaluation of satisfaction with assistive technology (QUEST) • An example of consumer-based and multidimensional instrument that taps domains related to overall impact on the users’ quality of life • The multidimensional nature makes it possible to separate influences of the technology, environment and personal preferences • Is capable to be employed across a wide rage of disabilities and assistive technology types • Has been widely used in the filed of assistive technology

References • • • Bronfenbrenner, U. (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist, 32, 513 -531. Brooks, N. A. (1990). User's perceptions of assistive devices. In R. V. Smith & J. H. J. Leslie (Eds. ), Rehabilitation engineering (pp. 495 -512). Boston: CRC Press. Brooks, N. A. (1991). Users' responses to assistive devices for physical disability. Social Science and Medicine, 32(12), 1417 -1424. Brooks, N. A. (1998). Models for understanding rehabilitation and assistive technology. In D. B. Gray, L. A. Quatrano & M. L. Lieberman (Eds. ), Designing and using assistive technology: the human perspective (pp. 3 -11). Baltimore: Paul H. Brooks. Caudrey, D. J. , & Seeger, B. R. (1983). Rehabilitation engineering service evaluation: a follow-up survey of device effectiveness and patient acceptance. Rehabilitation Literature, 44(3 -4), 80 -84. Clemson, L. , & Martin, R. (1996). Usage and effectiveness of rails, bathing and toileting aids. Occupational Therapy in Health Care, 10(1), 41 -59. Covington, G. A. (1998). Cultural and environmental barriers to assistive technology: why assistive devices don't always assist. In D. B. Gray, L. A. Quatrano & M. L. Lieberman (Eds. ), Designing and using assistive technology: the human perspective (pp. 77 -88). Baltimore: Paul H. Brooks. Dijcks, B. P. J. , De Witte, L. P. , Gelderblom, G. J. , Wessels, R. D. , & Soede, M. (2006). Non-use of assistive technology in The Netherlands: A non-issue? Disability and Rehabilitation: assistive technology, 1(1 -2), 97 -102. Gitlin, L. N. , Levine, R. , & Geiger, C. (1993). Adaptive device use by older adults with mixed disabilities. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 74, 149 -152. Heinemann, A. W. , Magiera-Planey, R. , Schiro-Geist, C. , & Gimines, G. (1987). Mobility for persons with spinal cord injury: an evaluation of two systems. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 68, 90 -93.

References • • • • Kohn, J. , Enders, S. , Preston, J. J. , & Motloch, W. (1983). Provision of assistive equipment for handicapped persons. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitations, 64, 378 -381. Lupton, D. , & Seymour, W. (2000). Technology, selfhood, and physical disability. Social Science and Medicine, 50, 1851 -1862. Mc. Grath, P. J. , Goodman, J. T. , Cunningham, S. J. , Mac. Donald, B. -J. , Nichols, T. A. , & Unruh, A. (1985). Assistive devices: utilization by children. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 66, 430 -432. Phillips, B. , & Zhao, H. (1993). Predictors of assistive technology abandonment. Assistive Technology, 5(1), 36 -45. Riemer-Reiss, M. L. , & Wacker, R. R. (2000). Factors associated with assistive technology discontinuance among individuals with disabilities. Journal of Rehabilitation, 66(3), 44 -50. Scherer, M. J. (1996). Outcomes of assistive technology use on quality of life. Disability and Rehabilitation, 18(9), 439 -448. Scherer, M. J. (1998). The impact of assistive technology on the lives of people with disabilities. In D. B. Gray, L. A. Quatrano & M. L. Lieberman (Eds. ), Designing and using assistive technology: the human perspective (pp. 99 -115). Baltimore: Paul H. Brooks. Scherer, M. J. (2000). Living in the state of stuck: how technology impacts the lives of people with disabilities (3 rd ed. ). Cambridge, MA: Brookline Books. Scherer, M. J. (2002). The change in emphasis from people to person: introduction to the special issue on Assistive Technology. Disability and Rehabilitation, 24(1/2/3), 1 -4. Sonn, U. , Davegardh, H. , Lindskog, A. C. , & Steen, B. (1996). The use and effectiveness of assistive devices in an elderly urban population. Aging, 8(3), 176 -183. Wielandt, T. , Mckenna, K. , Tooth, L. , & Strong, J. (2006). Factors that predict the post-discharge use of recommended assistive technology (AT). Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 1(1/2), 29 -40. World Health Organisation. (2001). International classification of functioning, disability, and health. Geneva: World Health Organization. Wressle, E. , & Samuelsson, K. (2004). User satisfaction with mobility assistive devices. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 11(3), 143 -150.