Understanding Ageing Understanding Sleep Capitalising on Understanding Society

- Slides: 54

Understanding Ageing, Understanding Sleep: Capitalising on Understanding Society Sara Arber Centre for Research on Ageing and Gender (CRAG) Department of Sociology, University of Surrey, Guildford, UK Understanding Society Conference, University of Essex, 21 -23 rd July 2015

3 Exemplars of ‘Understanding Society’ 1. Ageing – Impact of policy changes leading to ‘longer working’. Who is in paid employment and self-employed in their late 60 s? What is the likely impact on gender and other bases of inequality? 2. Sleep - Social inequalities in sleep. Is Sleep a potential mediator of the link between marital status and health? 3. Caregiving and sleep - Does care-giving impact on sleep? Does this differ for older caregivers (versus working age caregivers)? Aim: Demonstrate value of USoc – especially large sample size for robust analyses of proportionally small subgroups

Exemplar 1: Policy changes and impact on employment and inequality - in late 60 s 1. Increase in State Pension Age (SPA) for women from 60 to 65 (by 2018). 2. Increase in State Pension Age for men and women from 65 to 66 (in 2020) and 67 (in 2028) - then higher. 3. Removal of compulsory Retirement Age (at 65) – but ageism by employers, especially gendered ageism? Implications of these changes for: - Nature and patterns of employment/self-employment - Inequalities in income in later life - Gender and other bases of inequality

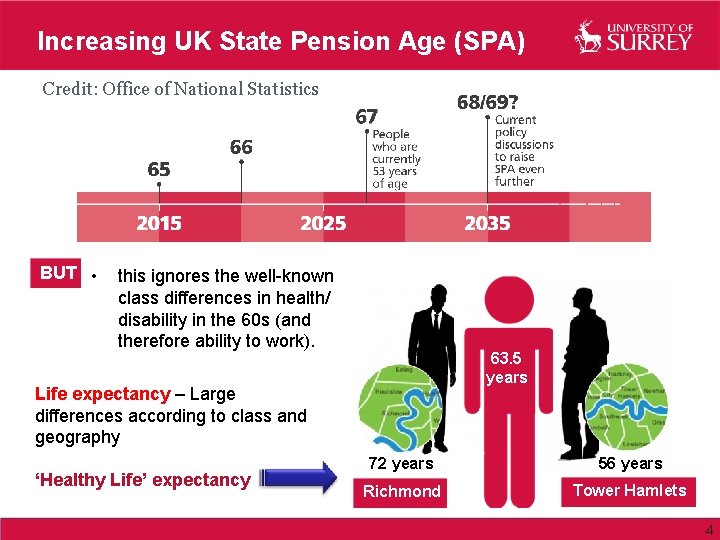

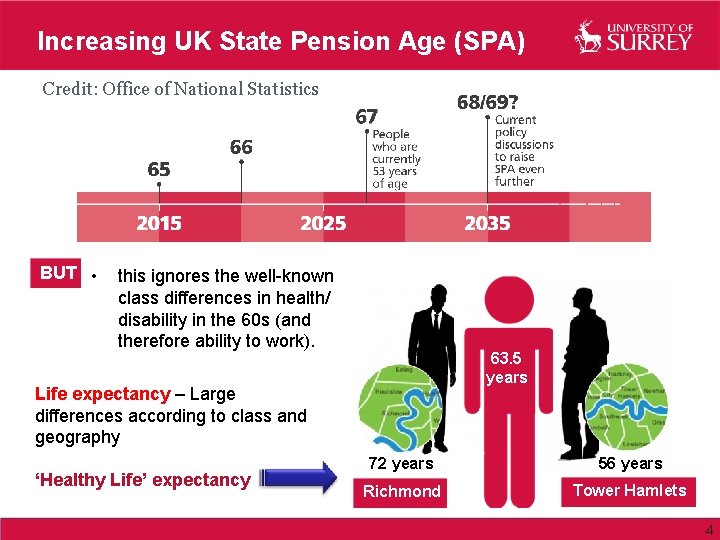

Increasing UK State Pension Age (SPA) Credit: Office of National Statistics BUT • this ignores the well-known class differences in health/ disability in the 60 s (and therefore ability to work). 63. 5 years Life expectancy – Large differences according to class and geography ‘Healthy Life’ expectancy 72 years 56 years Richmond Tower Hamlets 4

Implications of Increase in State Pension Age to 67 for Men and Women in the UK? Key Issue: Can/Will older women and men work beyond 65? Depends on: (i) Their health - class-related health inequalities (ii) Their caring responsibilities – for spouse, ageing parents, grandchildren (especially for women) (iii) Availability of jobs. Ageism (and Gendered ageism) in the labour market? If so, (1) What is the nature of this work and the likely remuneration? (2) Will opportunities to work over age 65 reduce or increase income (and gender) inequalities in later life?

Given these policy and other changes It is important to examine 3 interlocking factors: Employment 1. To what extent do women (and men) work up to and beyond the State Pension Age of 65 (66 by 2020)? 2. What type of jobs are they in? 3. To what extent are they employees or self-employed? Health 1. How is health related to employment/self-employment? Income 1. What are the income consequences of continuing to work – as an employee or as self-employed? 2. What are the levels of inequality related to different sources of income in later life? 3. How do these income inequalities differ by gender?

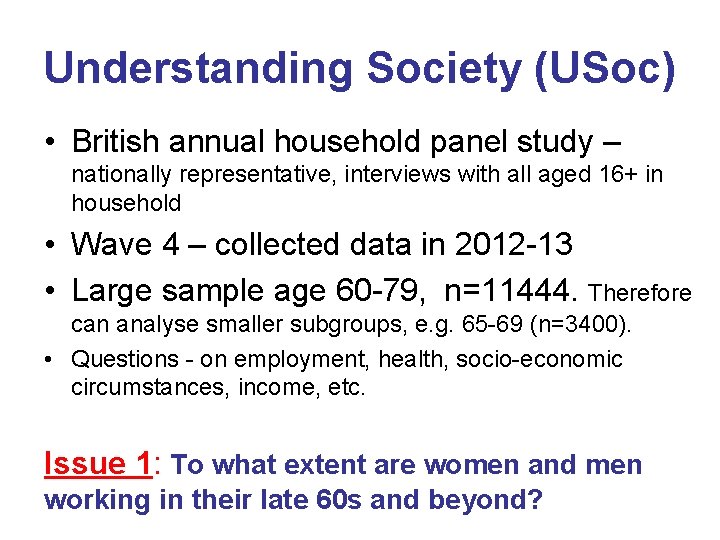

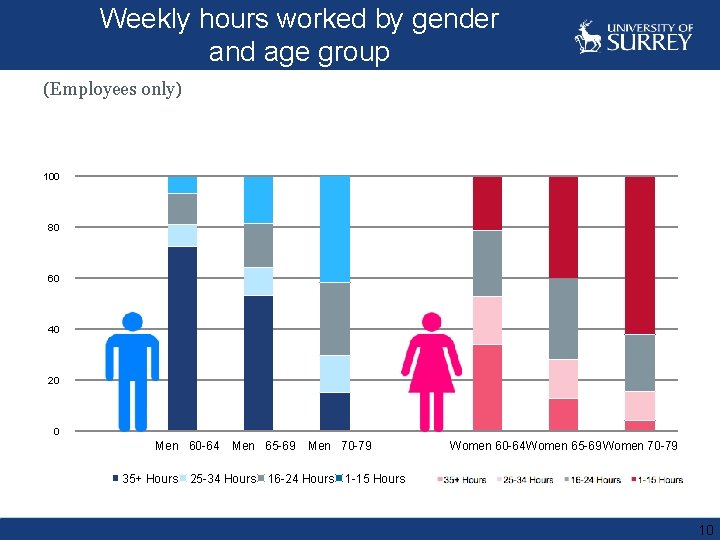

Understanding Society (USoc) • British annual household panel study – nationally representative, interviews with all aged 16+ in household • Wave 4 – collected data in 2012 -13 • Large sample age 60 -79, n=11444. Therefore can analyse smaller subgroups, e. g. 65 -69 (n=3400). • Questions - on employment, health, socio-economic circumstances, income, etc. Issue 1: To what extent are women and men working in their late 60 s and beyond?

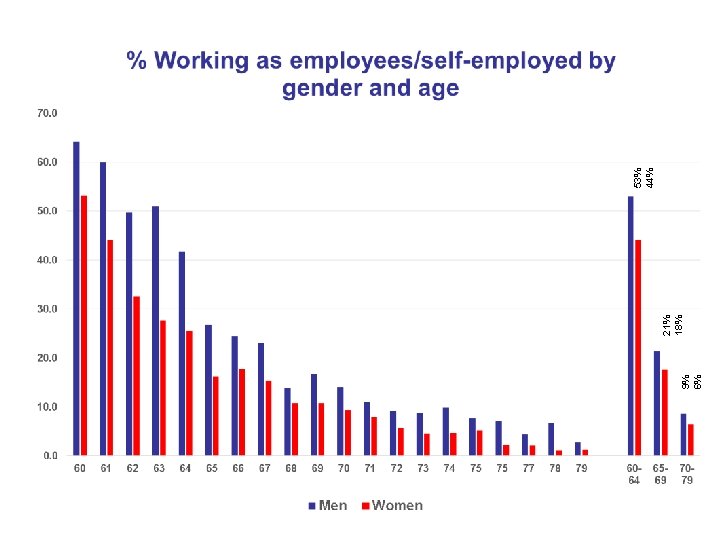

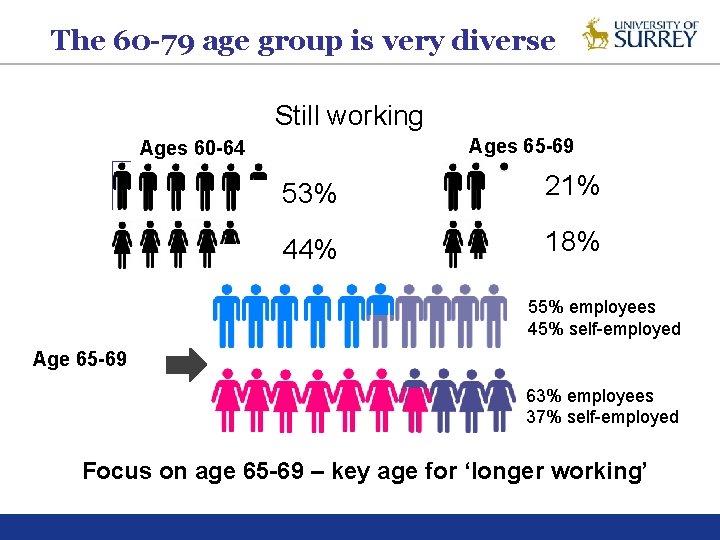

9% 6% 21% 18% 53% 44%

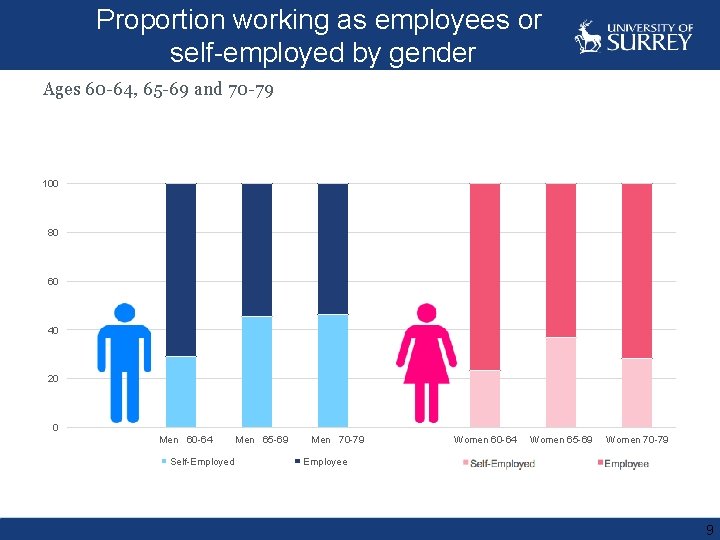

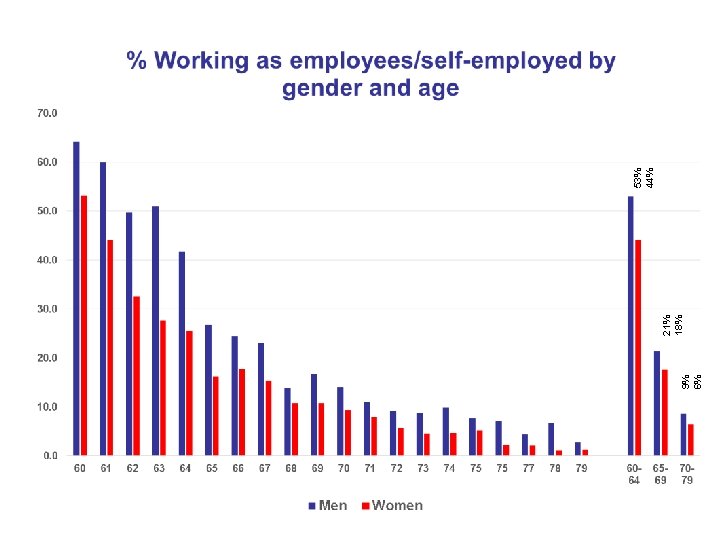

Proportion working as employees or self-employed by gender Ages 60 -64, 65 -69 and 70 -79 120 100 80 60 40 20 0 Men 60 -64 Self-Employed Men 65 -69 Men 70 -79 Women 60 -64 Women 65 -69 Women 70 -79 Employee 9

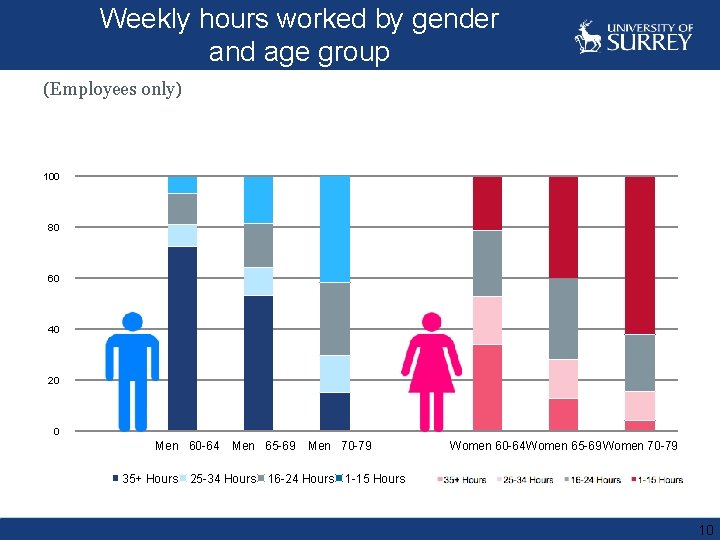

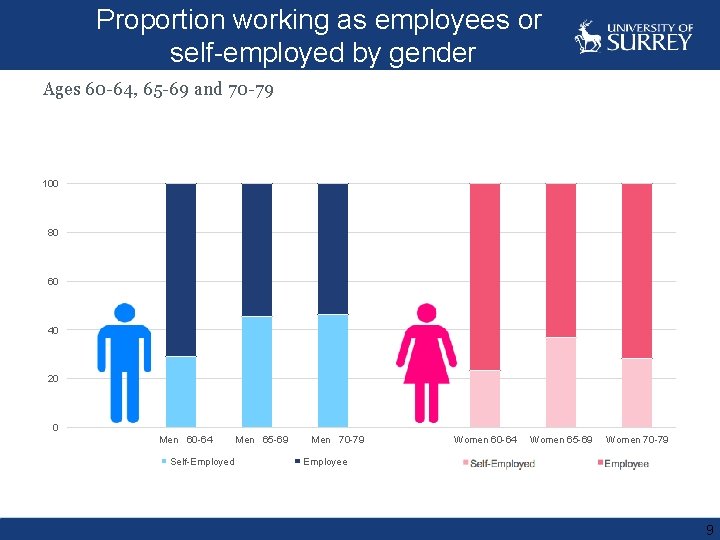

Weekly hours worked by gender and age group (Employees only) 120 100 80 60 40 20 0 Men 60 -64 Men 65 -69 Men 70 -79 Women 60 -64 Women 65 -69 Women 70 -79 35+ Hours 25 -34 Hours 16 -24 Hours 1 -15 Hours 10

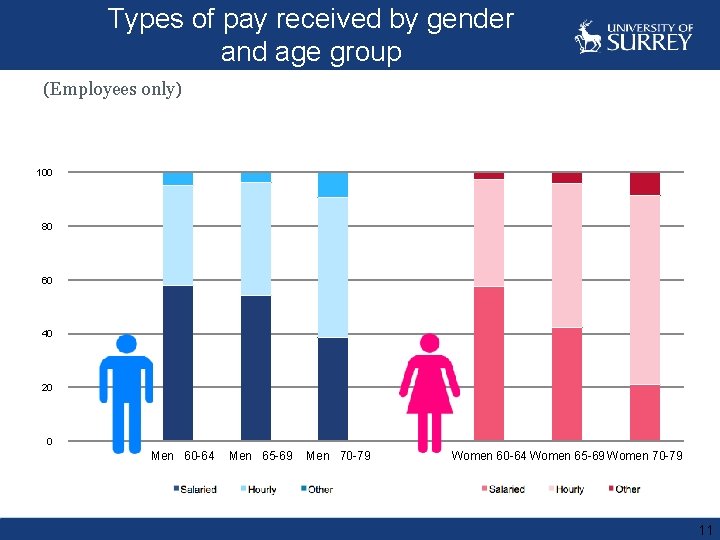

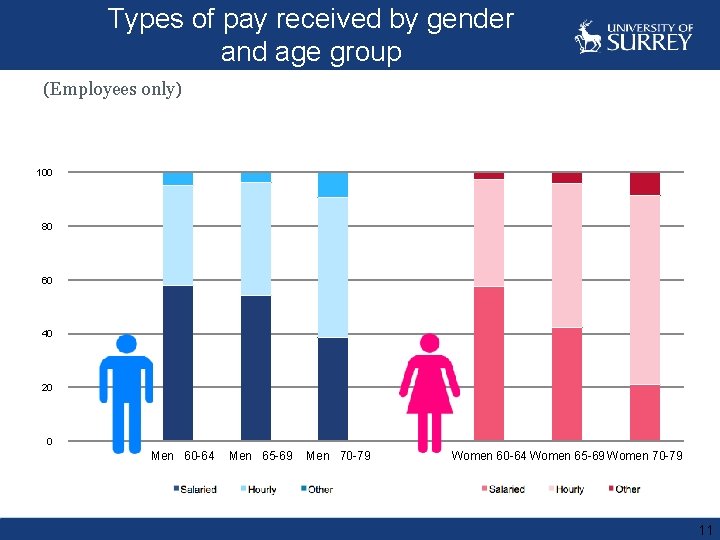

Types of pay received by gender and age group (Employees only) 120 100 80 60 40 20 0 Men 60 -64 Men 65 -69 Men 70 -79 Women 60 -64 Women 65 -69 Women 70 -79 11

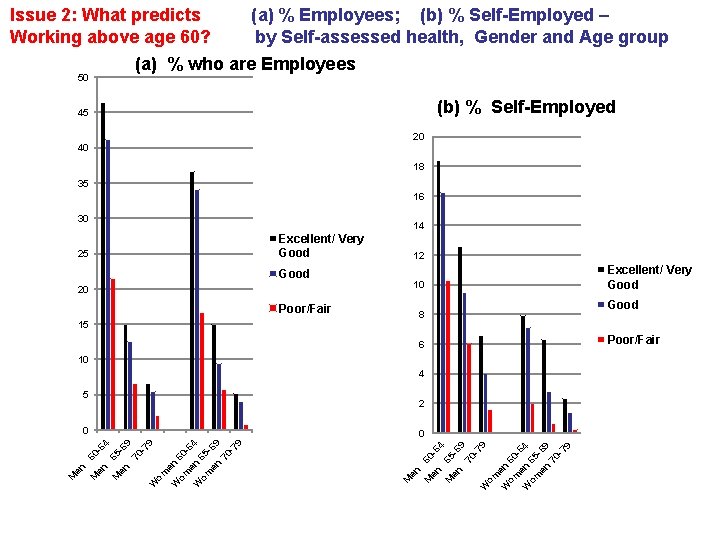

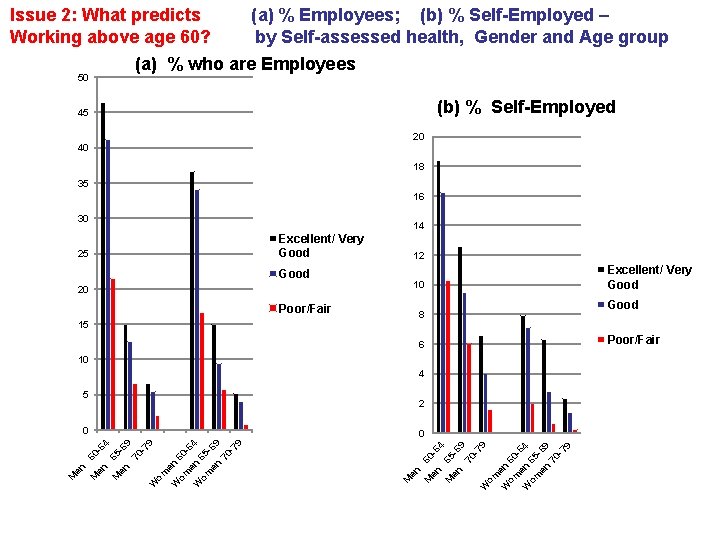

(a) % Employees; (b) % Self-Employed – by Self-assessed health, Gender and Age group (a) % who are Employees Issue 2: What predicts Working above age 60? 50 (b) % Self-Employed 45 20 40 18 35 16 30 25 14 Excellent/ Very Good 12 Good 10 20 Poor/Fair 8 15 6 10 4 5 2 en M 6 en 0 -6 4 M 65 en -6 9 70 -7 9 W om W en om 60 W en 64 om 65 en -69 70 -7 9 0 M M M en 6 en 0 -6 4 M 65 en -6 9 70 -7 9 W om W en om 60 -6 4 W en om 65 en -69 70 -7 9 0 Excellent/ Very Good Poor/Fair

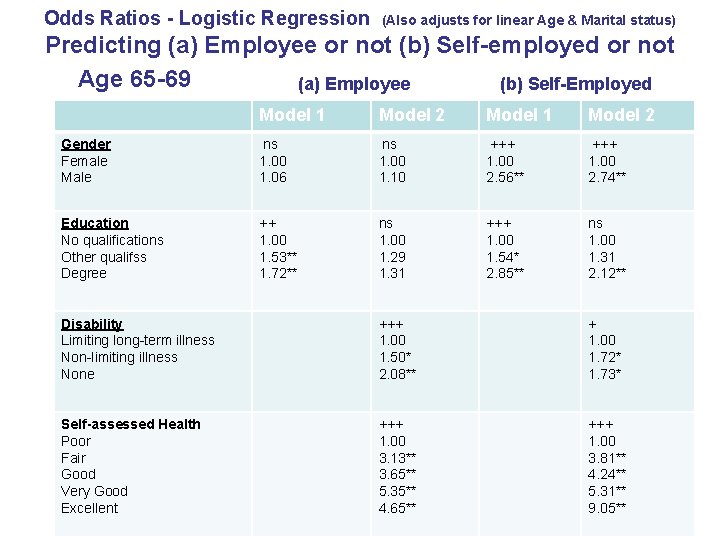

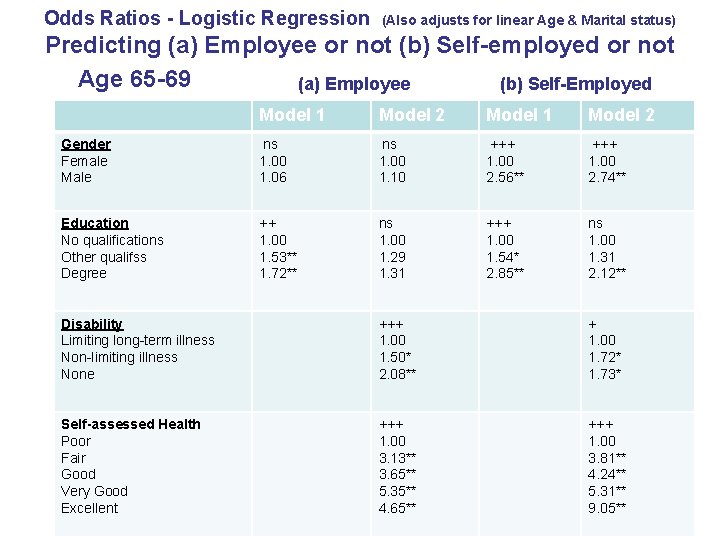

Odds Ratios - Logistic Regression (Also adjusts for linear Age & Marital status) Predicting (a) Employee or not (b) Self-employed or not Age 65 -69 (a) Employee (b) Self-Employed Model 1 Model 2 Gender Female Male ns 1. 00 1. 06 ns 1. 00 1. 10 +++ 1. 00 2. 56** +++ 1. 00 2. 74** Education No qualifications Other qualifss Degree ++ 1. 00 1. 53** 1. 72** ns 1. 00 1. 29 1. 31 +++ 1. 00 1. 54* 2. 85** ns 1. 00 1. 31 2. 12** Disability Limiting long-term illness Non-limiting illness None +++ 1. 00 1. 50* 2. 08** + 1. 00 1. 72* 1. 73* Self-assessed Health Poor Fair Good Very Good Excellent +++ 1. 00 3. 13** 3. 65** 5. 35** 4. 65** +++ 1. 00 3. 81** 4. 24** 5. 31** 9. 05**

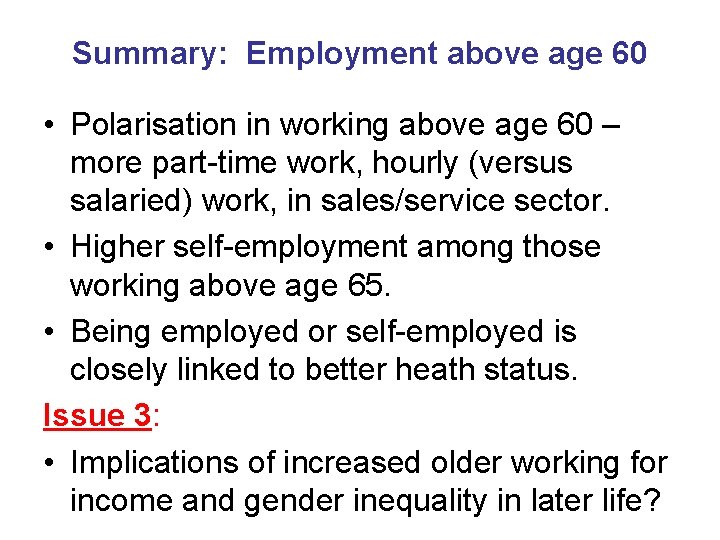

Summary: Employment above age 60 • Polarisation in working above age 60 – more part-time work, hourly (versus salaried) work, in sales/service sector. • Higher self-employment among those working above age 65. • Being employed or self-employed is closely linked to better heath status. Issue 3: • Implications of increased older working for income and gender inequality in later life?

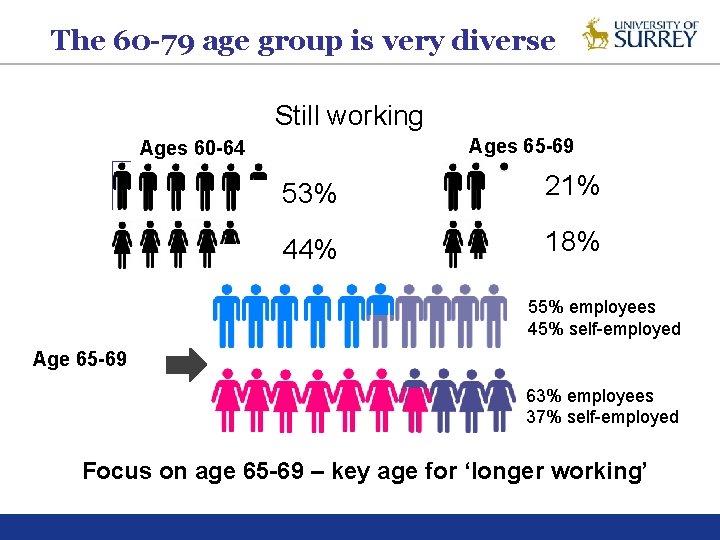

The 60 -79 age group is very diverse Still working Ages 65 -69 Ages 60 -64 53% 21% 44% 18% 55% employees 45% self-employed Age 65 -69 63% employees 37% self-employed Focus on age 65 -69 – key age for ‘longer working’

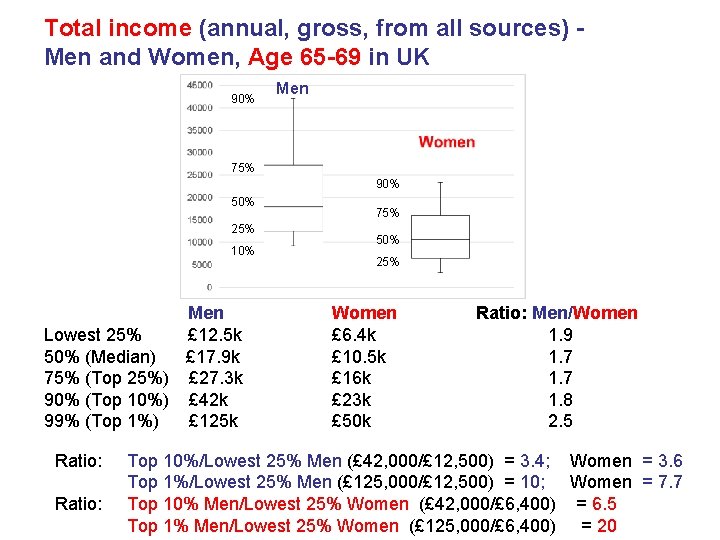

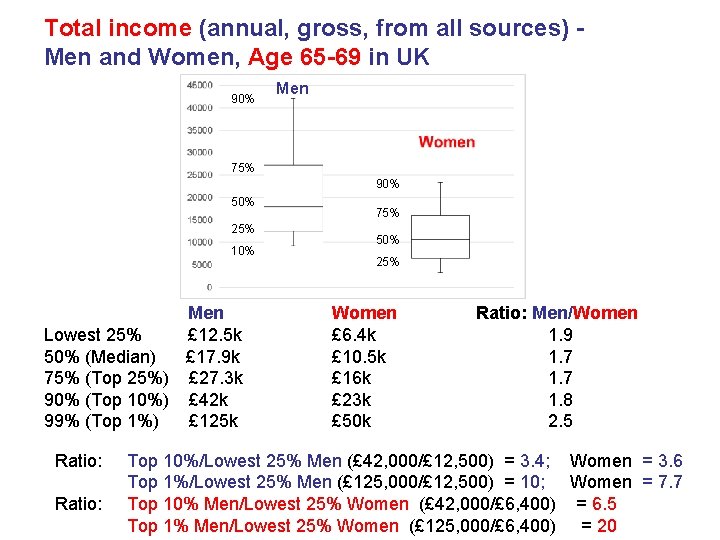

Total income (annual, gross, from all sources) Men and Women, Age 65 -69 in UK 90% Men 75% 90% 50% 25% 10% Men Lowest 25% £ 12. 5 k 50% (Median) £ 17. 9 k 75% (Top 25%) £ 27. 3 k 90% (Top 10%) £ 42 k 99% (Top 1%) £ 125 k Ratio: 75% 50% 25% Women £ 6. 4 k £ 10. 5 k £ 16 k £ 23 k £ 50 k Ratio: Men/Women 1. 9 1. 7 1. 8 2. 5 Top 10%/Lowest 25% Men (£ 42, 000/£ 12, 500) = 3. 4; Women = 3. 6 Top 1%/Lowest 25% Men (£ 125, 000/£ 12, 500) = 10; Women = 7. 7 Top 10% Men/Lowest 25% Women (£ 42, 000/£ 6, 400) = 6. 5 Top 1% Men/Lowest 25% Women (£ 125, 000/£ 6, 400) = 20

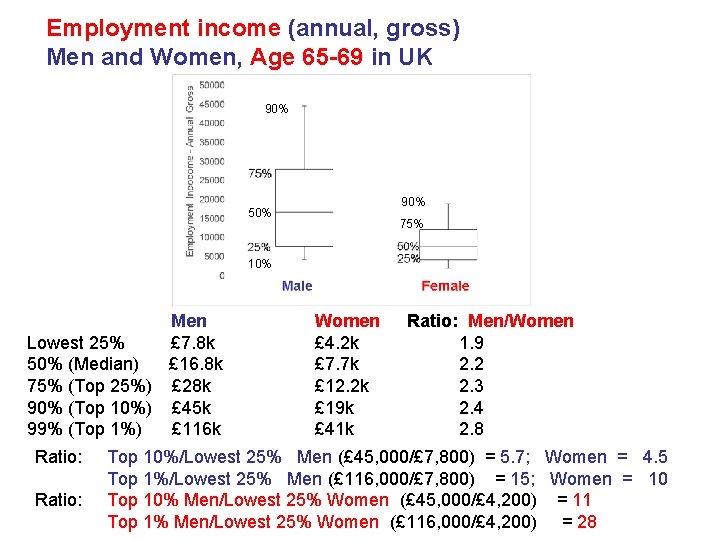

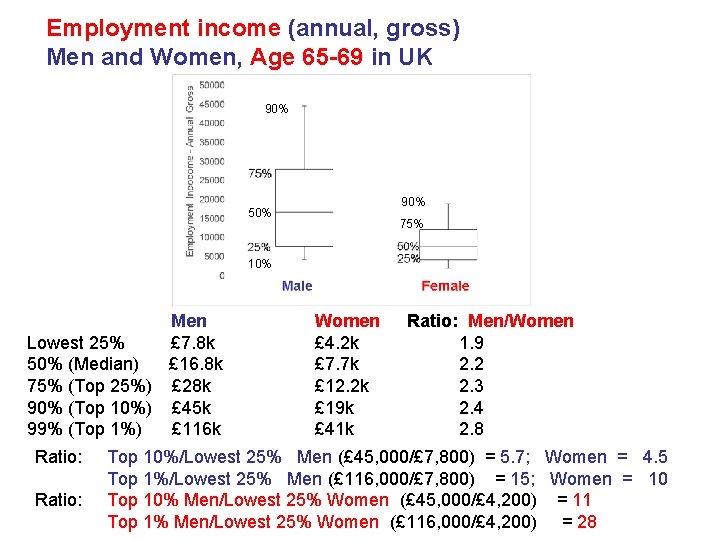

Employment income (annual, gross) Men and Women, Age 65 -69 in UK 90% 50% 75% 10% Men Lowest 25% £ 7. 8 k 50% (Median) £ 16. 8 k 75% (Top 25%) £ 28 k 90% (Top 10%) £ 45 k 99% (Top 1%) £ 116 k Ratio: Women £ 4. 2 k £ 7. 7 k £ 12. 2 k £ 19 k £ 41 k Ratio: Men/Women 1. 9 2. 2 2. 3 2. 4 2. 8 Top 10%/Lowest 25% Men (£ 45, 000/£ 7, 800) = 5. 7; Women = 4. 5 Top 1%/Lowest 25% Men (£ 116, 000/£ 7, 800) = 15; Women = 10 Top 10% Men/Lowest 25% Women (£ 45, 000/£ 4, 200) = 11 Top 1% Men/Lowest 25% Women (£ 116, 000/£ 4, 200) = 28

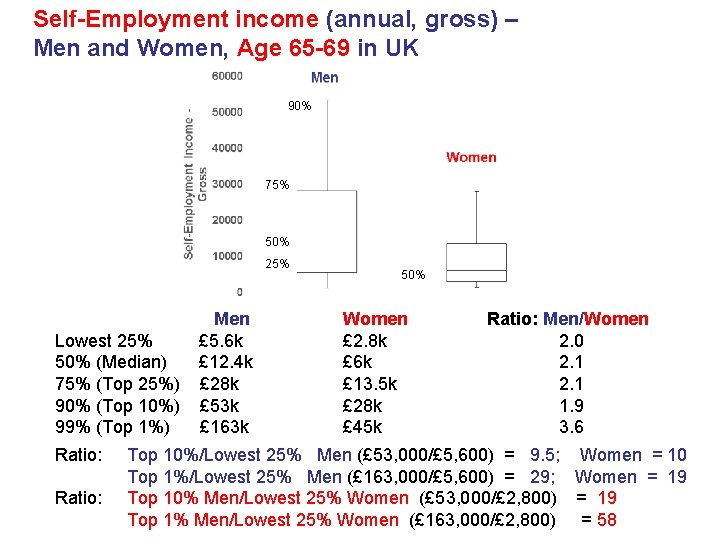

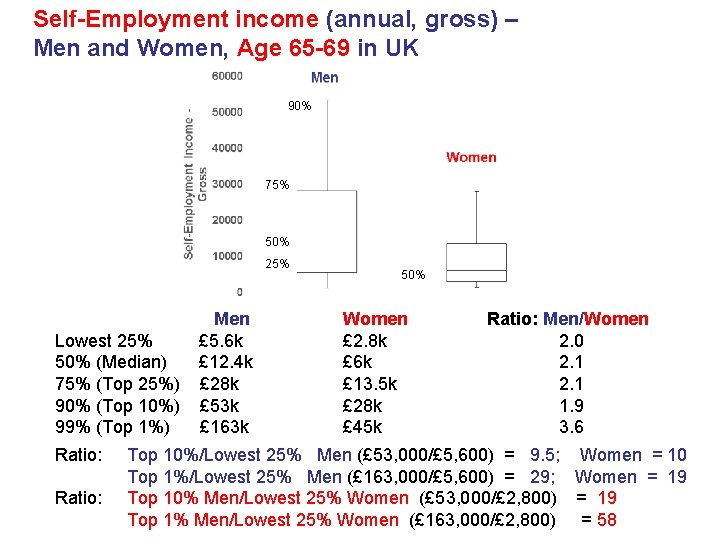

Self-Employment income (annual, gross) – Men and Women, Age 65 -69 in UK 90% 75% 50% 25% Lowest 25% 50% (Median) 75% (Top 25%) 90% (Top 10%) 99% (Top 1%) Ratio: Men £ 5. 6 k £ 12. 4 k £ 28 k £ 53 k £ 163 k 50% Women £ 2. 8 k £ 6 k £ 13. 5 k £ 28 k £ 45 k Ratio: Men/Women 2. 0 2. 1 1. 9 3. 6 Top 10%/Lowest 25% Men (£ 53, 000/£ 5, 600) = 9. 5; Women = 10 Top 1%/Lowest 25% Men (£ 163, 000/£ 5, 600) = 29; Women = 19 Top 10% Men/Lowest 25% Women (£ 53, 000/£ 2, 800) = 19 Top 1% Men/Lowest 25% Women (£ 163, 000/£ 2, 800) = 58

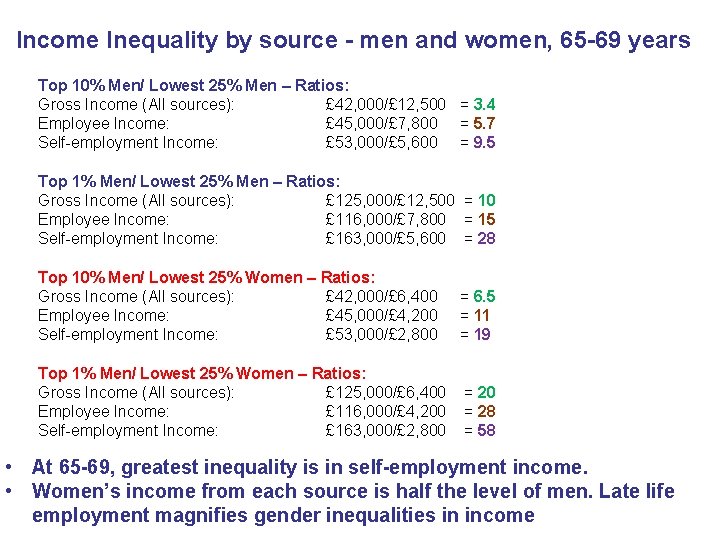

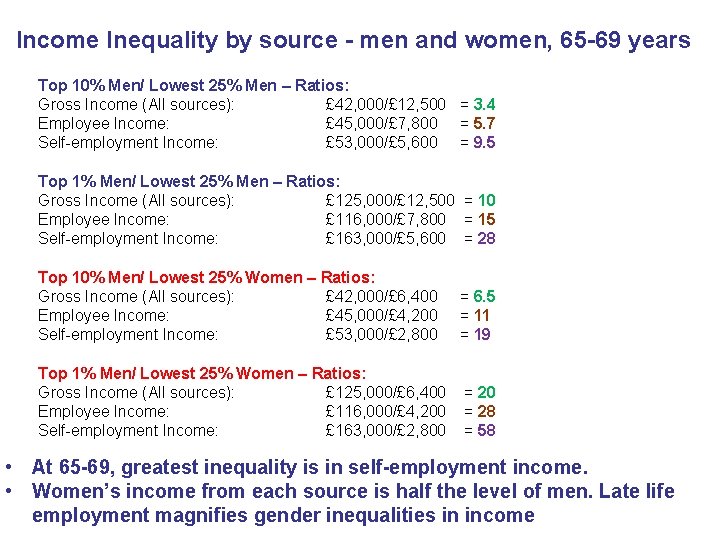

Income Inequality by source - men and women, 65 -69 years Top 10% Men/ Lowest 25% Men – Ratios: Gross Income (All sources): £ 42, 000/£ 12, 500 = 3. 4 Employee Income: £ 45, 000/£ 7, 800 = 5. 7 Self-employment Income: £ 53, 000/£ 5, 600 = 9. 5 Top 1% Men/ Lowest 25% Men – Ratios: Gross Income (All sources): £ 125, 000/£ 12, 500 = 10 Employee Income: £ 116, 000/£ 7, 800 = 15 Self-employment Income: £ 163, 000/£ 5, 600 = 28 Top 10% Men/ Lowest 25% Women – Ratios: Gross Income (All sources): £ 42, 000/£ 6, 400 Employee Income: £ 45, 000/£ 4, 200 Self-employment Income: £ 53, 000/£ 2, 800 = 6. 5 = 11 = 19 Top 1% Men/ Lowest 25% Women – Ratios: Gross Income (All sources): £ 125, 000/£ 6, 400 Employee Income: £ 116, 000/£ 4, 200 Self-employment Income: £ 163, 000/£ 2, 800 = 28 = 58 • At 65 -69, greatest inequality is in self-employment income. • Women’s income from each source is half the level of men. Late life employment magnifies gender inequalities in income

Exemplar 1: Conclusions Working above age 65 • Changes in pension and employment policies require/encourage older people in the UK to work beyond age 65. • BUT nature of employee jobs – often precarious, part -time. • Self-employment is high, but very diverse in nature. • Employment/self-employment – strongly related to health; greater for more educated. • Income inequalities are large in later life. • Self-employment/employment increases inequalities – cumulative disadvantage. • Gender income disadvantages increase with age.

Conclusions - Gender and Generation • Interconnections of inequality between the Generations – • • Greater income inequality in later life – will magnify inequalities earlier in the life course. Financial support of older generation to assist house purchase and education of younger generation is highly income related. • Interconnections of Gender and Generation – • Older generation women - increasingly support daughters’ paid employment (by providing grandchild care), but this may constrain their own ‘active ageing’, and reduce their own pension income. Mid-life women - providing elder care for their parents/inlaw may constrain their own employment, and reduce their own future pension income and financial well-being in later life.

Exemplar 2: Sleep and Health Sleep – is under researched by social scientists • Surprising – because we spend a third of our lives asleep • Sleep is fundamental to well-being and health • Sleep is part of everyday life – therefore may provide a ‘window’ on everyday roles and relationships

Adverse consequences of lack of sleep • A major cause of accidents • Cause of falls among older people • Important for cognitive functioning, and essential for memory consolidation • Sleep problems often predate depression • Impact of lack of sleep (<6 hrs + poor quality) on mortality (especially from CHD) • Physiological link between short sleep and chronic ill-health (liver function, impaired immunity, obesity)

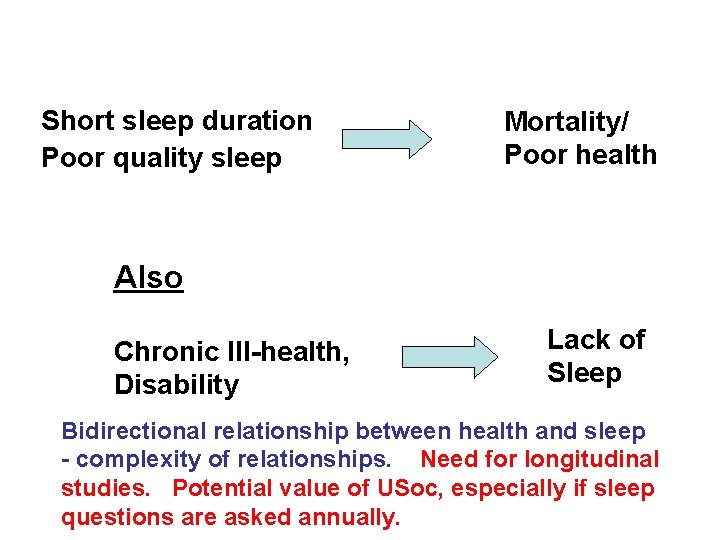

Short sleep duration Poor quality sleep Mortality/ Poor health Also Chronic Ill-health, Disability Lack of Sleep Bidirectional relationship between health and sleep - complexity of relationships. Need for longitudinal studies. Potential value of USoc, especially if sleep questions are asked annually.

Analogy with ‘Inequalities in Health’ research Over the last 25 years – extensive research has analysed Inequalities in Health, e. g. - The magnitude of Inequalities in Health - For which groups are there greater inequalities in health – by class, gender, ethnicity, nature of work/working conditions, etc. - Causes of Inequalities in Health - Ways of reducing Inequalities in Health - Health Policy implications of Inequalities in Health Similarly for Sleep – need to analyse Inequalities in Sleep Quality and Short Sleep Duration (e. g. <6 hours) - can do with USoc

Analysing social determinants of poor sleep would include : Identify the sociological/social factors influencing the quality of sleep/short sleep, e. g. - Age, marital status, who else lives in the household - Socio-economic circumstances, employment status, shiftwork, income, education, housing quality - Impact of partners and children (if any), Sleeping arrangements - Worries about work, family, money, relationships, loneliness, etc. - Environmental factors – noise, light, neighbours, pets - Sleep ‘hygiene’ behaviours – coffee, alcohol, smoking - Physical health status, pain, disability status - Psychological health – depression, stress USoc allows analysis of relative importance of most of these factors in influencing quality/length of sleep

Exemplar: Analysis of Sleep, Health and Marital Status using Understanding Society - Rob Meadows as Lead • Wave 1 in 2009 -10 (Sleep questions also in Wave 4) • Self-completion module includes 7 sleep items • Analysis of data for 37, 253 aged 16+ (who completed sleep module) Arber, S. and Meadows, R. (2011) “Social and Health Patterning of Sleep Quality and Duration”. In S Mc. Fall and C Garrington (eds) Understanding Society: Early Findings from the first wave of the UK’s Household Longitudinal Study, Colchester: ISER, University of Essex. Meadows, R. and Arber, S. (2015) “Marital status, relationship distress and self-rated health: What role for ‘sleep problems’? ” Journal of Health and Social Behaviour, Forthcoming September 2015.

Link between marital status and health Well-known link between marital status and health – married people have better health/ lower mortality than the non-married • Need more understanding of the mechanisms • Including meaning of marital status Research Questions: • How does marital status/relationship quality link to health? • What are the associations between marital status/relationship quality and sleep? • Does sleep mediate the link between marital status/relationship quality and health?

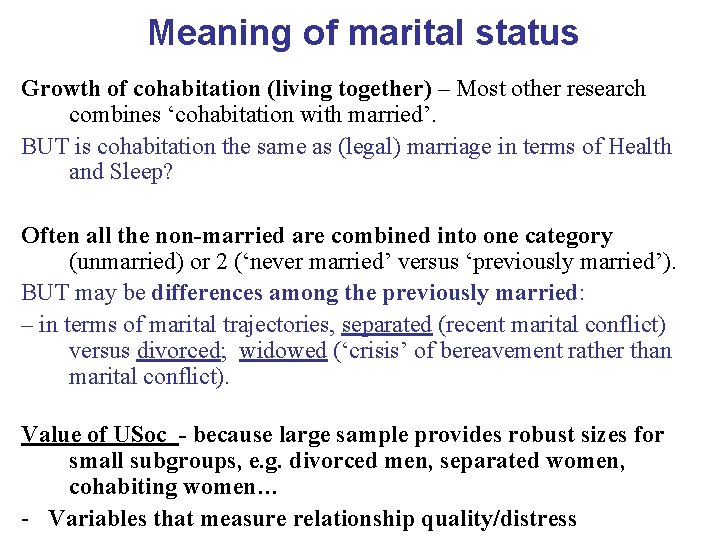

Meaning of marital status Growth of cohabitation (living together) – Most other research combines ‘cohabitation with married’. BUT is cohabitation the same as (legal) marriage in terms of Health and Sleep? Often all the non-married are combined into one category (unmarried) or 2 (‘never married’ versus ‘previously married’). BUT may be differences among the previously married: – in terms of marital trajectories, separated (recent marital conflict) versus divorced; widowed (‘crisis’ of bereavement rather than marital conflict). Value of USoc - because large sample provides robust sizes for small subgroups, e. g. divorced men, separated women, cohabiting women… - Variables that measure relationship quality/distress

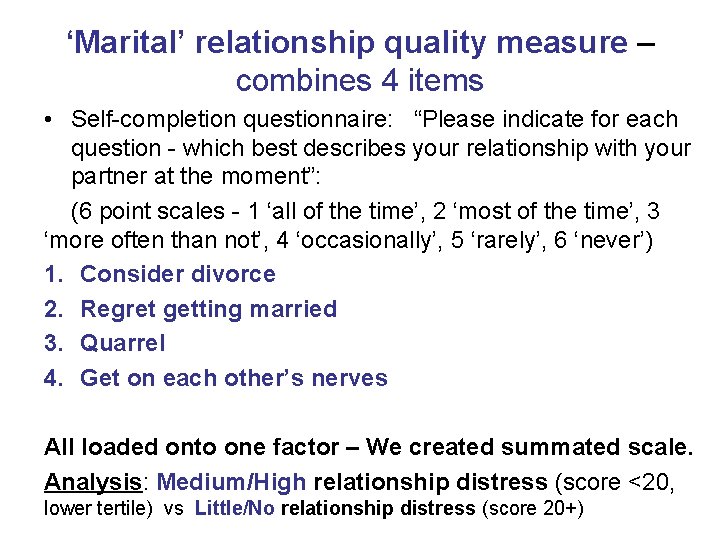

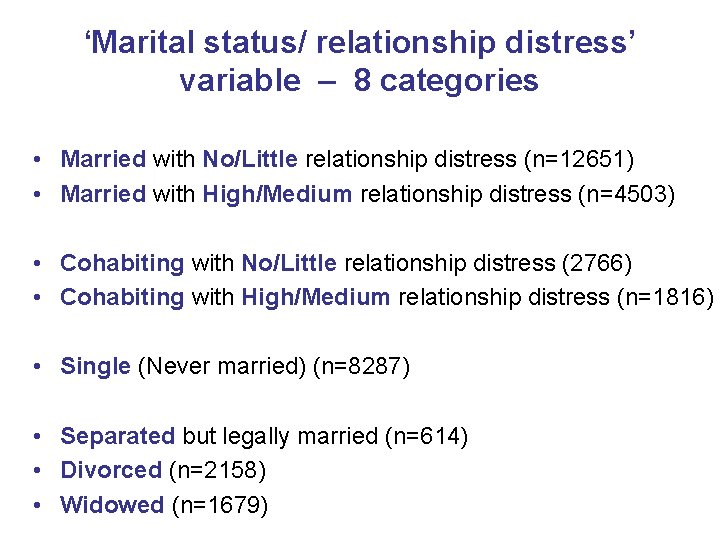

‘Marital’ relationship quality measure – combines 4 items • Self-completion questionnaire: “Please indicate for each question - which best describes your relationship with your partner at the moment”: (6 point scales - 1 ‘all of the time’, 2 ‘most of the time’, 3 ‘more often than not’, 4 ‘occasionally’, 5 ‘rarely’, 6 ‘never’) 1. Consider divorce 2. Regret getting married 3. Quarrel 4. Get on each other’s nerves All loaded onto one factor – We created summated scale. Analysis: Medium/High relationship distress (score <20, lower tertile) vs Little/No relationship distress (score 20+)

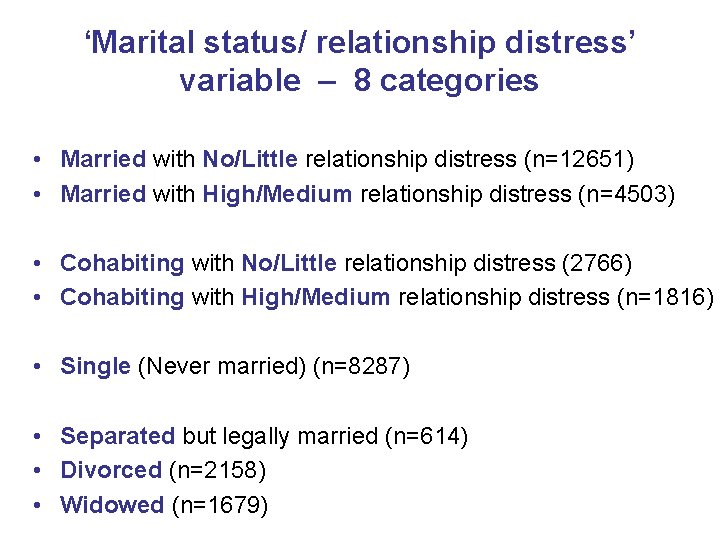

‘Marital status/ relationship distress’ variable – 8 categories • Married with No/Little relationship distress (n=12651) • Married with High/Medium relationship distress (n=4503) • Cohabiting with No/Little relationship distress (2766) • Cohabiting with High/Medium relationship distress (n=1816) • Single (Never married) (n=8287) • Separated but legally married (n=614) • Divorced (n=2158) • Widowed (n=1679)

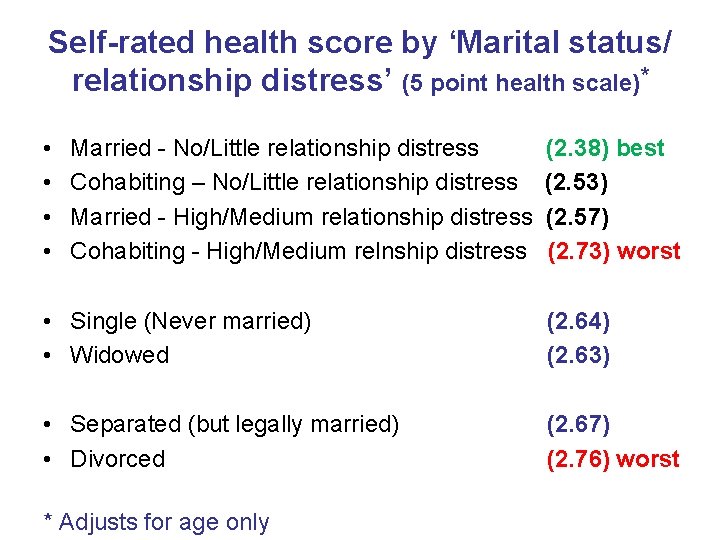

Self-rated Health 5 point Likert scale: 12345 - Excellent Very good Good Fair Poor We analyse as a ‘linear’ scale

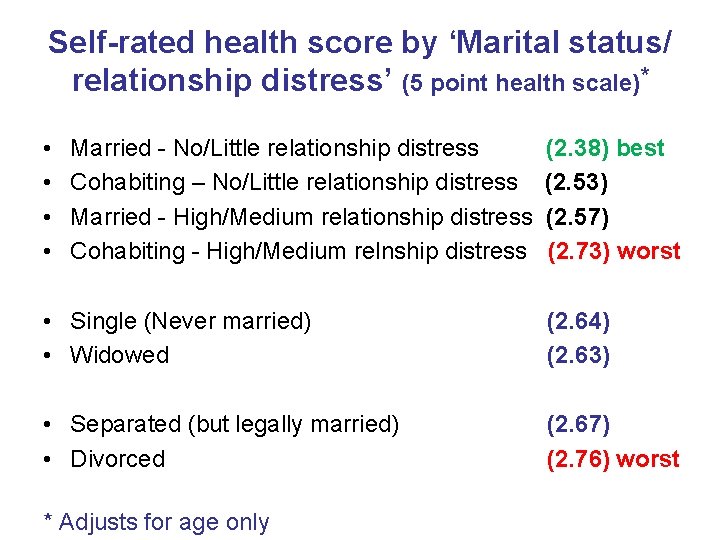

Self-rated health score by ‘Marital status/ relationship distress’ (5 point health scale)* • • Married - No/Little relationship distress Cohabiting – No/Little relationship distress Married - High/Medium relationship distress Cohabiting - High/Medium relnship distress (2. 38) best (2. 53) (2. 57) (2. 73) worst • Single (Never married) • Widowed (2. 64) (2. 63) • Separated (but legally married) • Divorced (2. 67) (2. 76) worst * Adjusts for age only

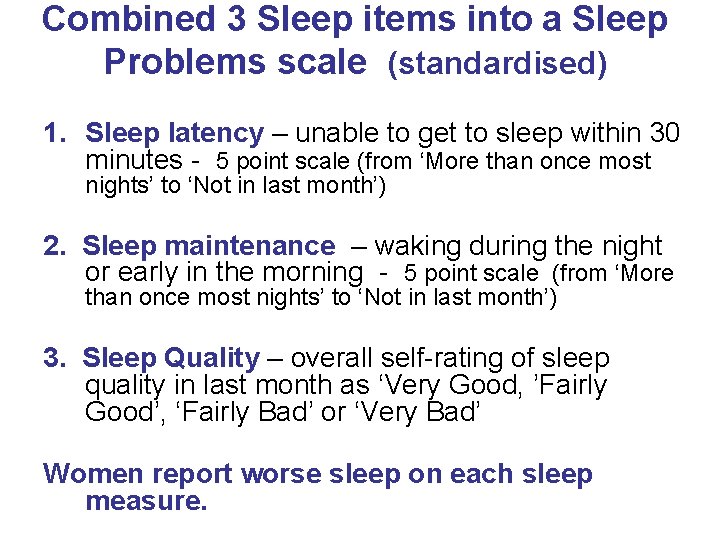

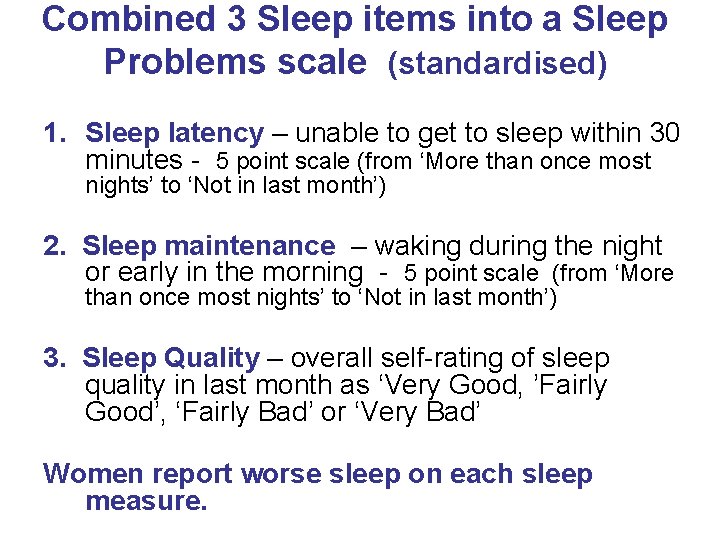

Combined 3 Sleep items into a Sleep Problems scale (standardised) 1. Sleep latency – unable to get to sleep within 30 minutes - 5 point scale (from ‘More than once most nights’ to ‘Not in last month’) 2. Sleep maintenance – waking during the night or early in the morning - 5 point scale (from ‘More than once most nights’ to ‘Not in last month’) 3. Sleep Quality – overall self-rating of sleep quality in last month as ‘Very Good, ’Fairly Good’, ‘Fairly Bad’ or ‘Very Bad’ Women report worse sleep on each sleep measure.

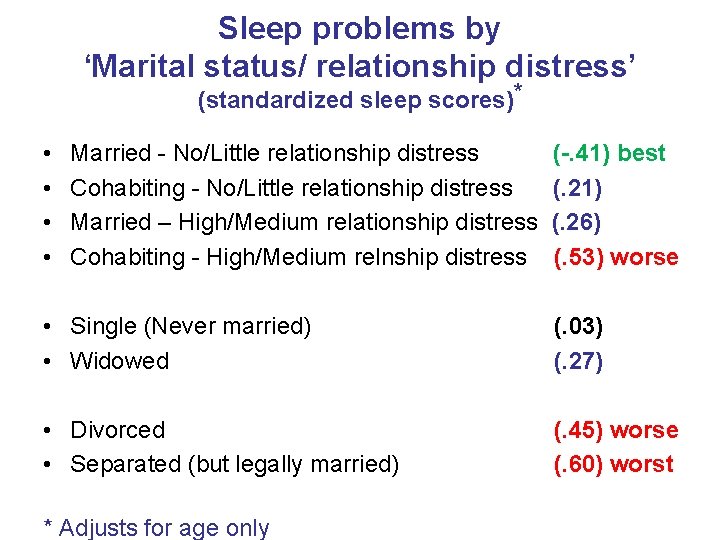

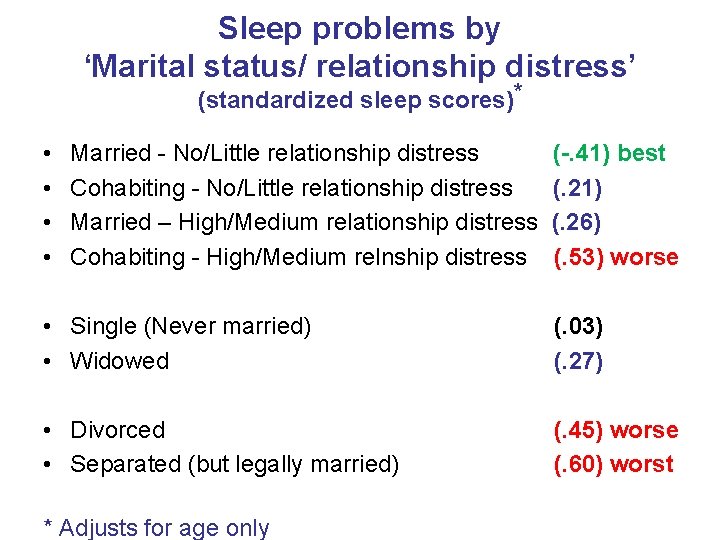

Sleep problems by ‘Marital status/ relationship distress’ (standardized sleep scores)* • • Married - No/Little relationship distress Cohabiting - No/Little relationship distress Married – High/Medium relationship distress Cohabiting - High/Medium relnship distress (-. 41) best (. 21) (. 26) (. 53) worse • Single (Never married) • Widowed (. 03) (. 27) • Divorced • Separated (but legally married) (. 45) worse (. 60) worst * Adjusts for age only

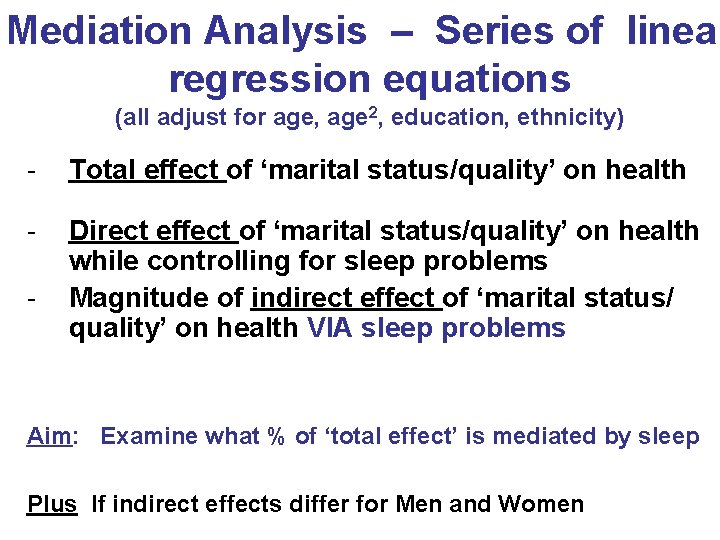

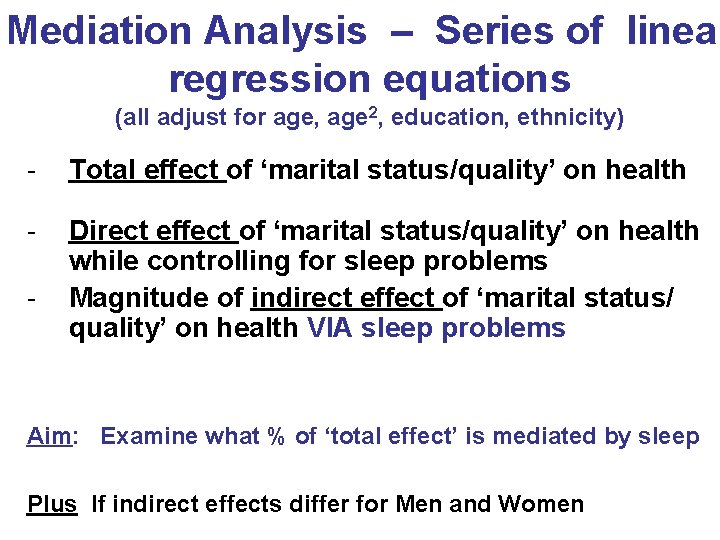

Mediation Analysis – Series of linear regression equations (all adjust for age, age 2, education, ethnicity) - Total effect of ‘marital status/quality’ on health - Direct effect of ‘marital status/quality’ on health while controlling for sleep problems Magnitude of indirect effect of ‘marital status/ quality’ on health VIA sleep problems - Aim: Examine what % of ‘total effect’ is mediated by sleep Plus If indirect effects differ for Men and Women

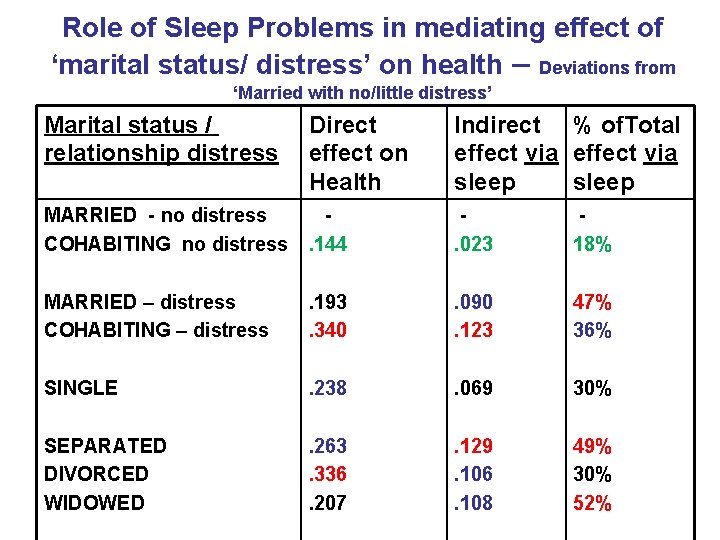

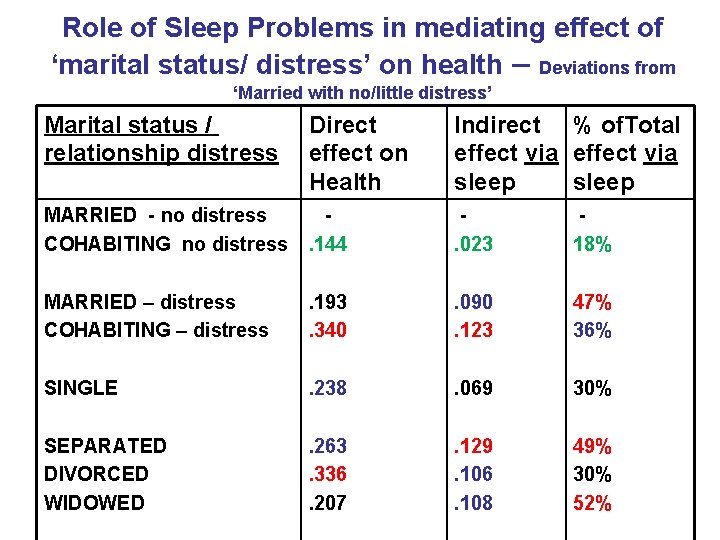

Role of Sleep Problems in mediating effect of ‘marital status/ distress’ on health – Deviations from ‘Married with no/little distress’ Marital status / relationship distress Direct effect on Health Indirect % of. Total effect via sleep MARRIED - no distress COHABITING no distress . 144 . 023 18% MARRIED – distress COHABITING – distress . 193. 340 . 090. 123 47% 36% SINGLE . 238 . 069 30% SEPARATED DIVORCED WIDOWED . 263. 336. 207 . 129. 106. 108 49% 30% 52%

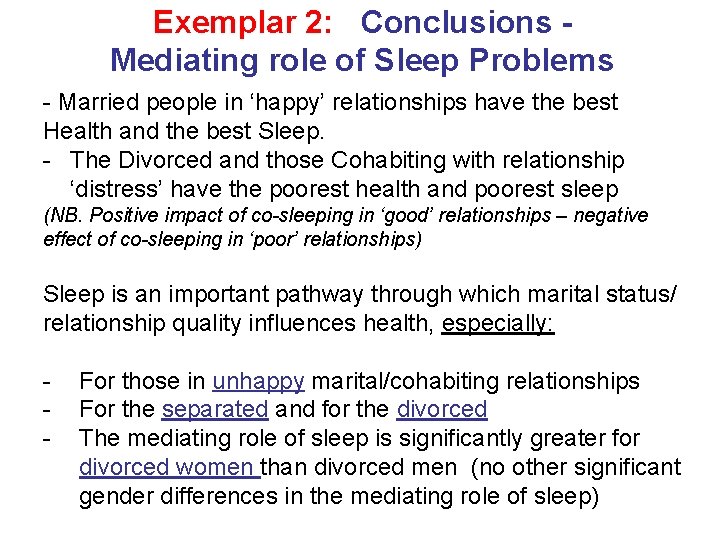

Exemplar 2: Conclusions Mediating role of Sleep Problems - Married people in ‘happy’ relationships have the best Health and the best Sleep. - The Divorced and those Cohabiting with relationship ‘distress’ have the poorest health and poorest sleep (NB. Positive impact of co-sleeping in ‘good’ relationships – negative effect of co-sleeping in ‘poor’ relationships) Sleep is an important pathway through which marital status/ relationship quality influences health, especially: - For those in unhappy marital/cohabiting relationships For the separated and for the divorced The mediating role of sleep is significantly greater for divorced women than divorced men (no other significant gender differences in the mediating role of sleep)

Exemplar 3: Sleep, Care-giving and Ageing Merges – my previous research interests in: - Caregiving, - Ageing, and - Sleep Illustrates power of USoc to combine previously unconnected areas of social scientific research.

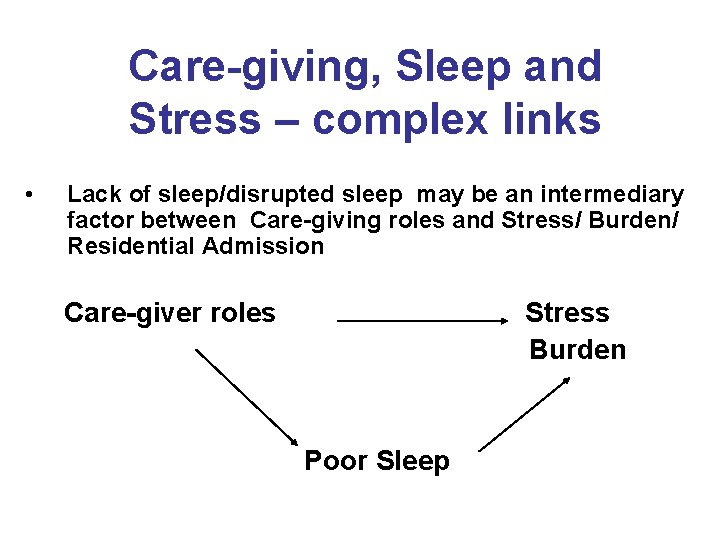

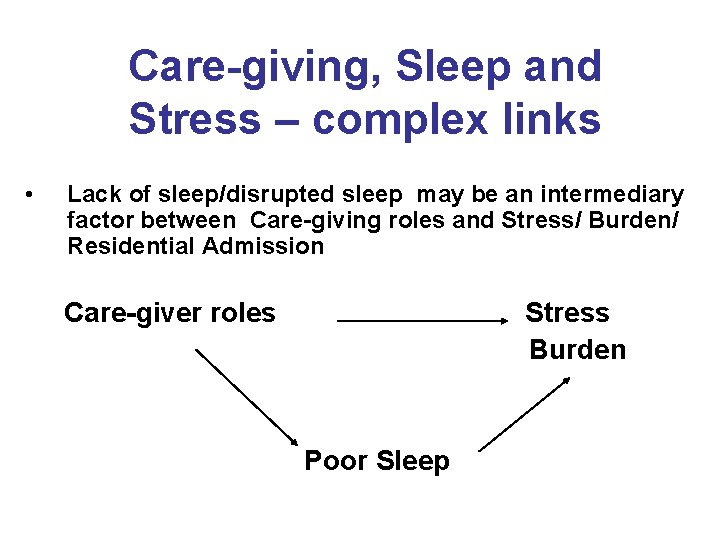

Care-giving, Sleep and Stress – complex links • Lack of sleep/disrupted sleep may be an intermediary factor between Care-giving roles and Stress/ Burden/ Residential Admission Care-giver roles Stress Burden Poor Sleep

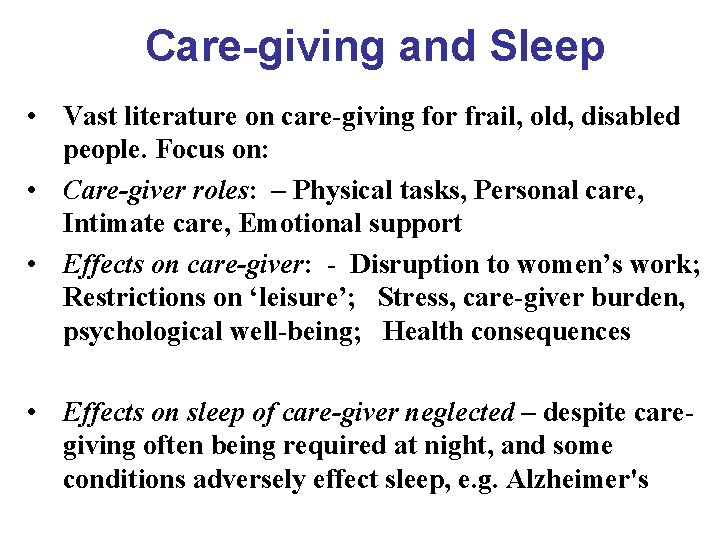

Care-giving and Sleep • Vast literature on care-giving for frail, old, disabled people. Focus on: • Care-giver roles: – Physical tasks, Personal care, Intimate care, Emotional support • Effects on care-giver: - Disruption to women’s work; Restrictions on ‘leisure’; Stress, care-giver burden, psychological well-being; Health consequences • Effects on sleep of care-giver neglected – despite caregiving often being required at night, and some conditions adversely effect sleep, e. g. Alzheimer's

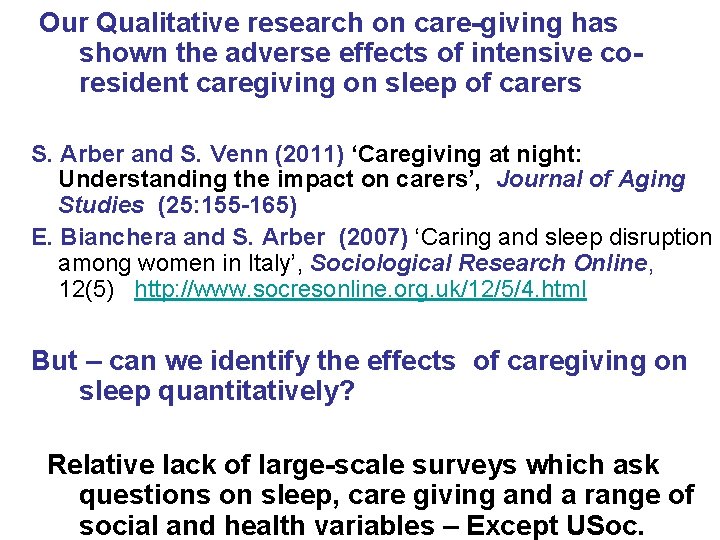

Our Qualitative research on care-giving has shown the adverse effects of intensive coresident caregiving on sleep of carers S. Arber and S. Venn (2011) ‘Caregiving at night: Understanding the impact on carers’, Journal of Aging Studies (25: 155 -165) E. Bianchera and S. Arber (2007) ‘Caring and sleep disruption among women in Italy’, Sociological Research Online, 12(5) http: //www. socresonline. org. uk/12/5/4. html But – can we identify the effects of caregiving on sleep quantitatively? Relative lack of large-scale surveys which ask questions on sleep, care giving and a range of social and health variables – Except USoc.

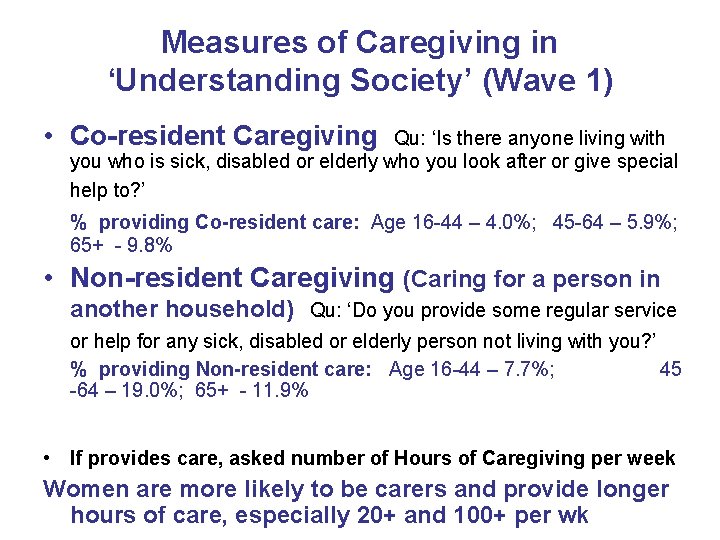

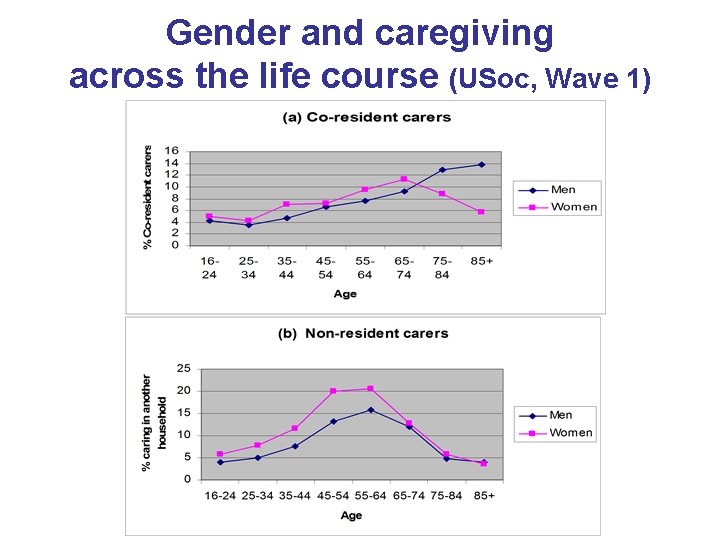

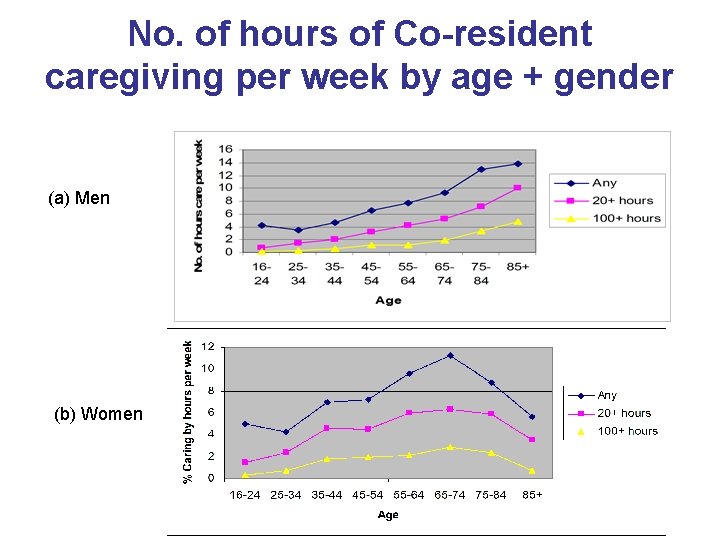

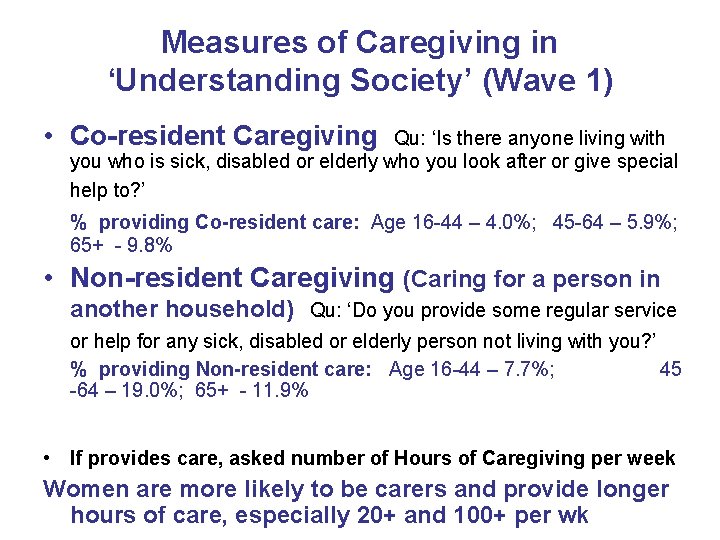

Measures of Caregiving in ‘Understanding Society’ (Wave 1) • Co-resident Caregiving Qu: ‘Is there anyone living with you who is sick, disabled or elderly who you look after or give special help to? ’ % providing Co-resident care: Age 16 -44 – 4. 0%; 45 -64 – 5. 9%; 65+ - 9. 8% • Non-resident Caregiving (Caring for a person in another household) Qu: ‘Do you provide some regular service or help for any sick, disabled or elderly person not living with you? ’ % providing Non-resident care: Age 16 -44 – 7. 7%; 45 -64 – 19. 0%; 65+ - 11. 9% • If provides care, asked number of Hours of Caregiving per week Women are more likely to be carers and provide longer hours of care, especially 20+ and 100+ per wk

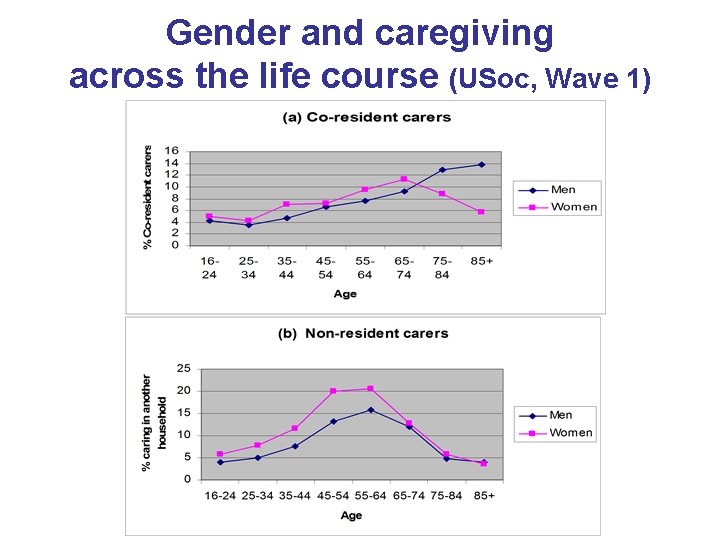

Gender and caregiving across the life course (USoc, Wave 1)

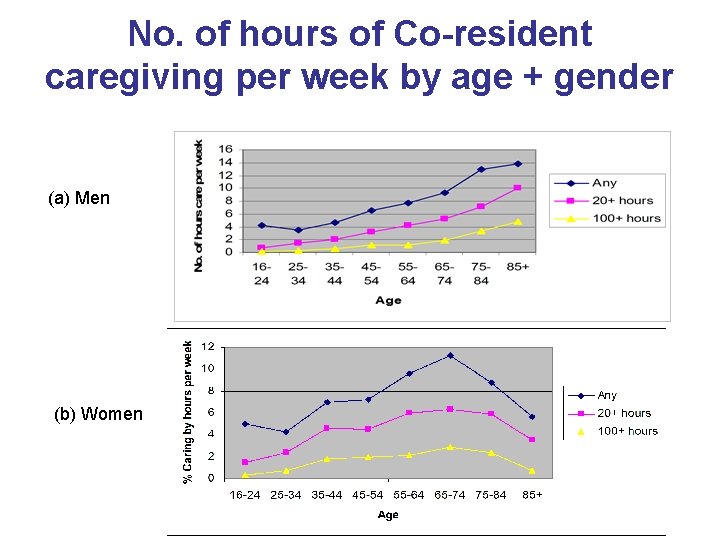

No. of hours of Co-resident caregiving per week by age + gender (a) Men (b) Women

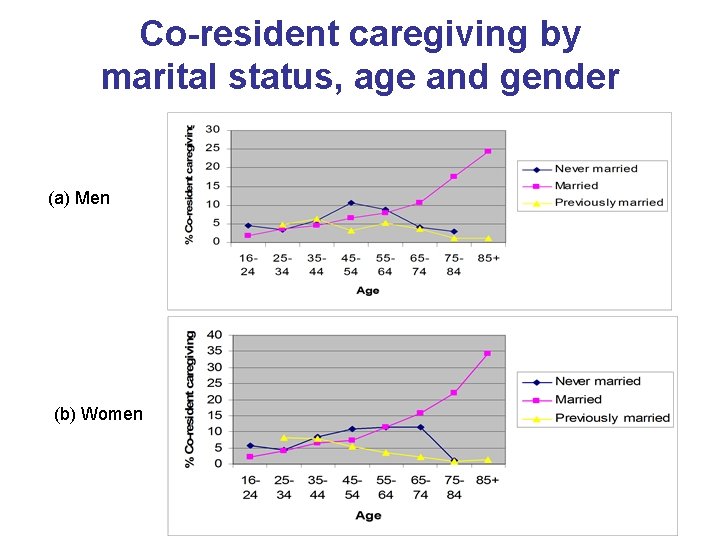

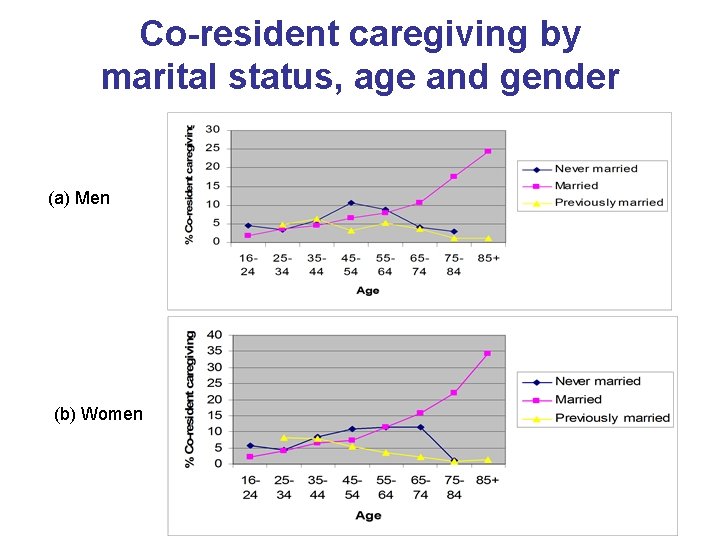

Co-resident caregiving by marital status, age and gender (a) Men (b) Women

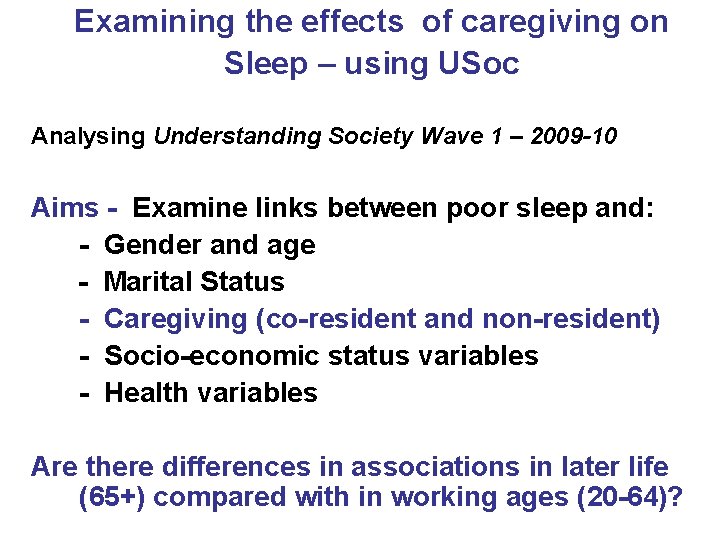

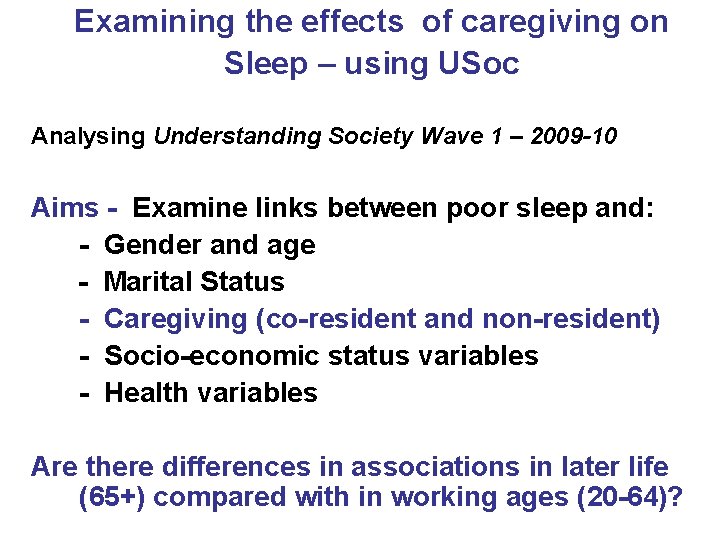

Examining the effects of caregiving on Sleep – using USoc Analysing Understanding Society Wave 1 – 2009 -10 Aims - Examine links between poor sleep and: - Gender and age - Marital Status - Caregiving (co-resident and non-resident) - Socio-economic status variables - Health variables Are there differences in associations in later life (65+) compared with in working ages (20 -64)?

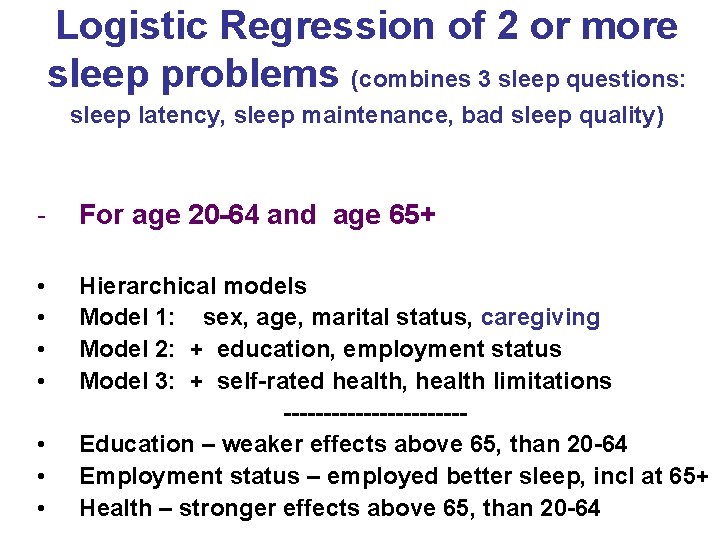

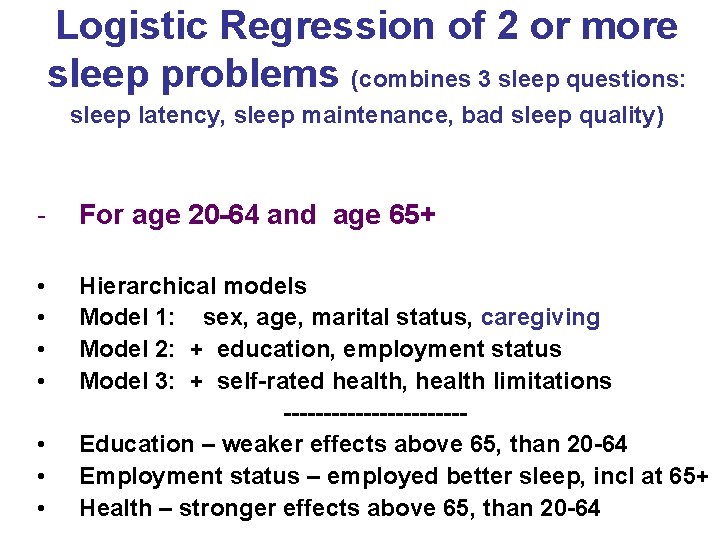

Logistic Regression of 2 or more sleep problems (combines 3 sleep questions: sleep latency, sleep maintenance, bad sleep quality) - For age 20 -64 and age 65+ • • Hierarchical models Model 1: sex, age, marital status, caregiving Model 2: + education, employment status Model 3: + self-rated health, health limitations -----------Education – weaker effects above 65, than 20 -64 Employment status – employed better sleep, incl at 65+ Health – stronger effects above 65, than 20 -64 • • •

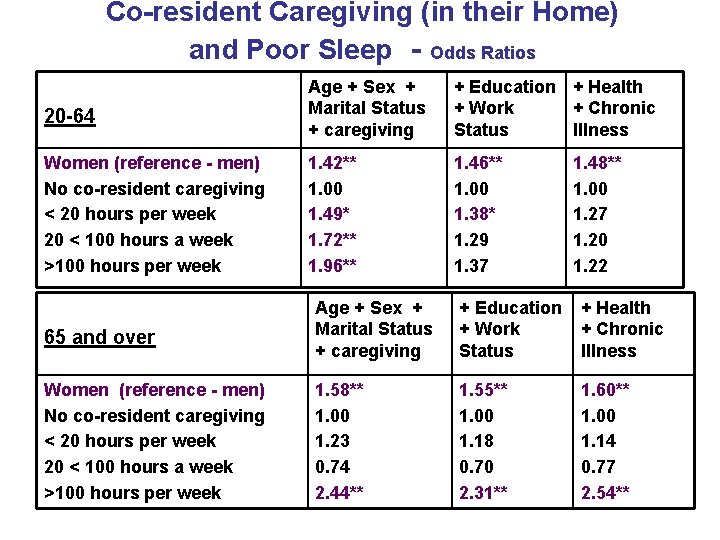

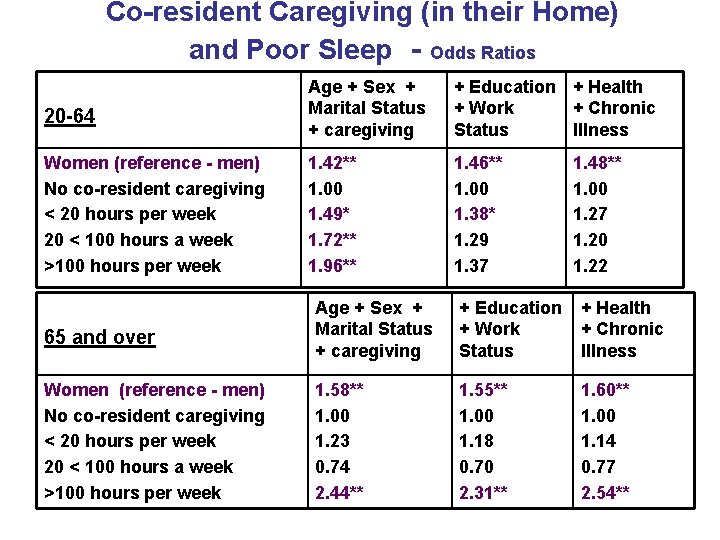

Co-resident Caregiving (in their Home) and Poor Sleep - Odds Ratios 20 -64 Age + Sex + Marital Status + caregiving + Education + Health + Work + Chronic Status Illness Women (reference - men) No co-resident caregiving < 20 hours per week 20 < 100 hours a week >100 hours per week 1. 42** 1. 00 1. 49* 1. 72** 1. 96** 1. 46** 1. 00 1. 38* 1. 29 1. 37 1. 48** 1. 00 1. 27 1. 20 1. 22 65 and over Age + Sex + Marital Status + caregiving + Education + Work Status + Health + Chronic Illness Women (reference - men) No co-resident caregiving < 20 hours per week 20 < 100 hours a week >100 hours per week 1. 58** 1. 00 1. 23 0. 74 2. 44** 1. 55** 1. 00 1. 18 0. 70 2. 31** 1. 60** 1. 00 1. 14 0. 77 2. 54**

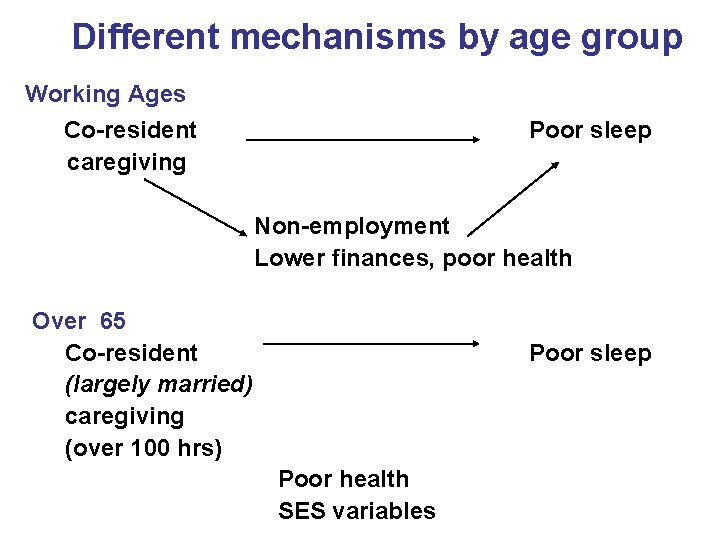

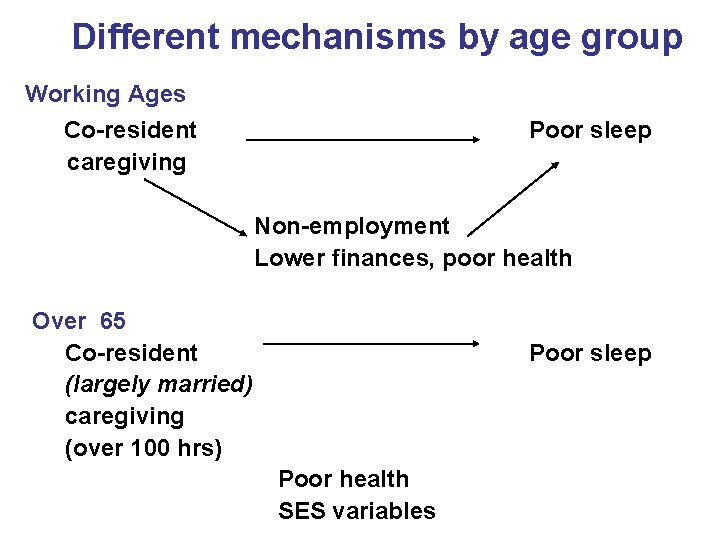

Different mechanisms by age group Working Ages Co-resident caregiving Poor sleep Non-employment Lower finances, poor health Over 65 Co-resident (largely married) caregiving (over 100 hrs) Poor sleep Poor health SES variables

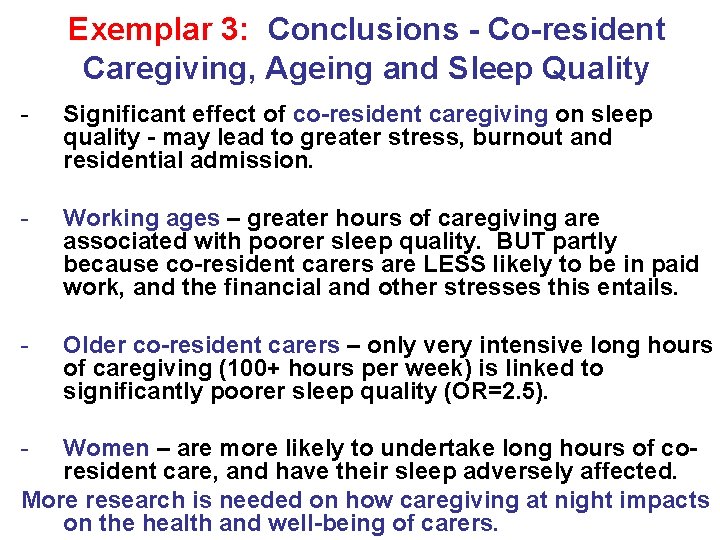

Exemplar 3: Conclusions - Co-resident Caregiving, Ageing and Sleep Quality - Significant effect of co-resident caregiving on sleep quality - may lead to greater stress, burnout and residential admission. - Working ages – greater hours of caregiving are associated with poorer sleep quality. BUT partly because co-resident carers are LESS likely to be in paid work, and the financial and other stresses this entails. - Older co-resident carers – only very intensive long hours of caregiving (100+ hours per week) is linked to significantly poorer sleep quality (OR=2. 5). - Women – are more likely to undertake long hours of coresident care, and have their sleep adversely affected. More research is needed on how caregiving at night impacts on the health and well-being of carers.

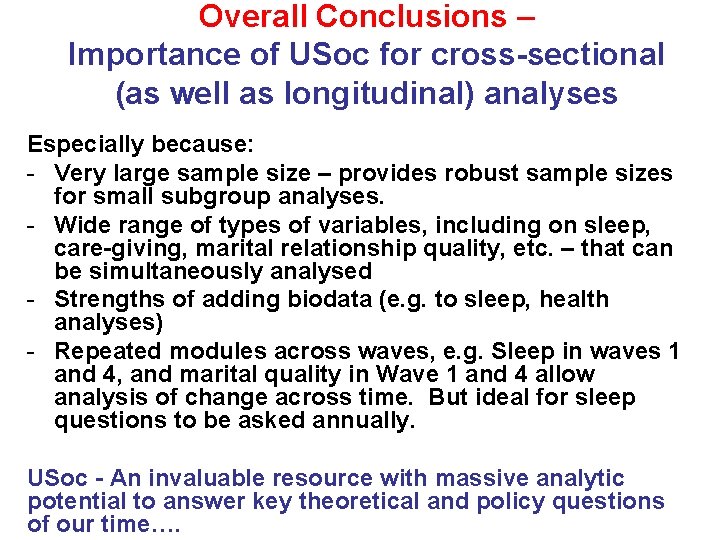

Overall Conclusions – Importance of USoc for cross-sectional (as well as longitudinal) analyses Especially because: - Very large sample size – provides robust sample sizes for small subgroup analyses. - Wide range of types of variables, including on sleep, care-giving, marital relationship quality, etc. – that can be simultaneously analysed - Strengths of adding biodata (e. g. to sleep, health analyses) - Repeated modules across waves, e. g. Sleep in waves 1 and 4, and marital quality in Wave 1 and 4 allow analysis of change across time. But ideal for sleep questions to be asked annually. USoc - An invaluable resource with massive analytic potential to answer key theoretical and policy questions of our time….

Acknowledgements We are grateful to the ISER, University of Essex for permission to analyse the ‘Understanding Society’ Wave 1 and Wave 4 data. The research was supported by the: European Union Marie Curie ‘The biomedical and sociological effects of sleep restriction’, grant MCRTN-CT-2004 -512362 (2005 -09) New Dynamics of Ageing initiative, a multidisciplinary research programme supported by AHRC, BBSRC, EPSRC, ESRC and MRC (RES 339 -25 -0009) (2006 -11) Especial thanks to my co-researchers - Rob Meadows, Sue Venn and Emanuela Bianchera S. Arber@surrey. ac. uk

The End Thank you for your attention Email: S. Arber@surrey. ac. uk