UNCTAD The role of finance for development Penelope

- Slides: 19

UNCTAD The role of finance for development Penelope Hawkins Senior Economic Affairs Officer Debt and Financial Analysis branch Division on Globalisation and Development Strategies 19 February 2019 penelope. hawkins@un. org

Overview • Finance for development – mantra since 2015 • Net negative resource flows out of developing countries • Official finance and ODA failed to keep up with promises or need • Is Blended finance the solution? • Space for regional options?

The financing gap Mind the gap : Addis Ababa and Agenda 2030 • Current public and private initiatives to implement the Addis Ababa Action Agenda and to fulfil the SDGs are insufficient. • UNCTAD estimates of financing gap sets the annual financing gap of $2. 5 trillion a year for developing countries UNCTAD 2014 a • To meet only the first of the Sustainable Development Goals (‘no poverty’) by 2030, and assuming that savings, FDI and ODA stay at current levels, Africa alone would have to grow at double digit rates of over 15% per year. • How to mind the gap: • Identifying new and additional sources of finance • Plug the holes IFF profit-shifting • Design and implementation of viable nation and regional long-term financing and debt strategies linked to sustainable and productive investment and development.

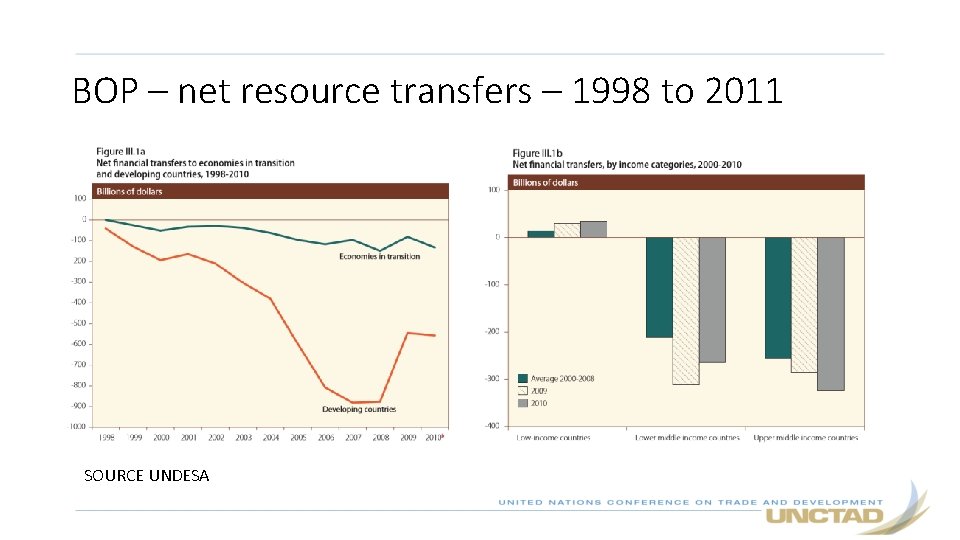

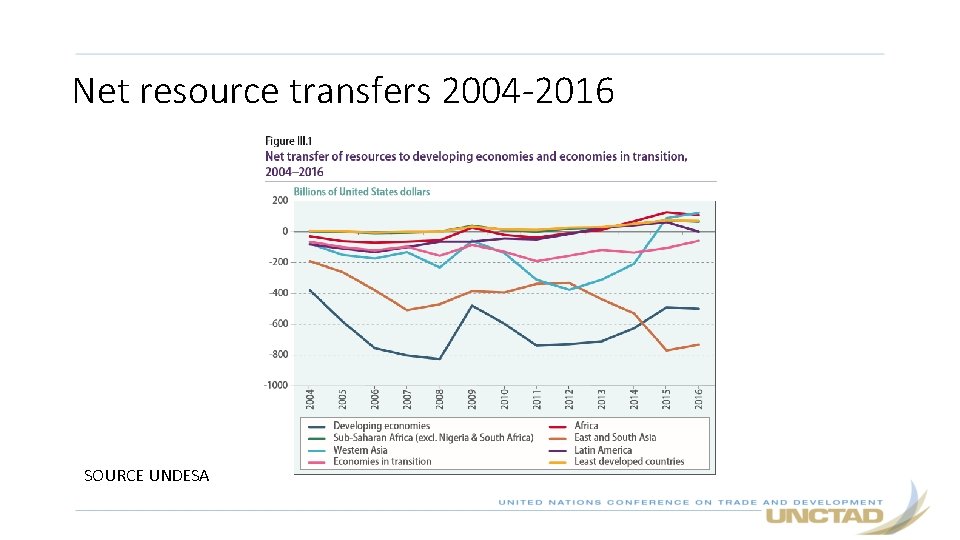

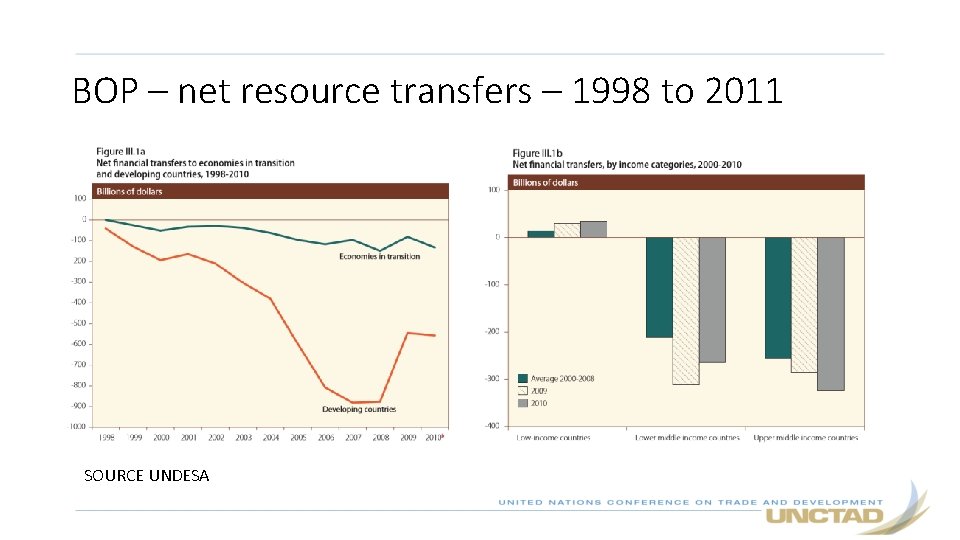

BOP – net resource transfers – 1998 to 2011 SOURCE UNDESA

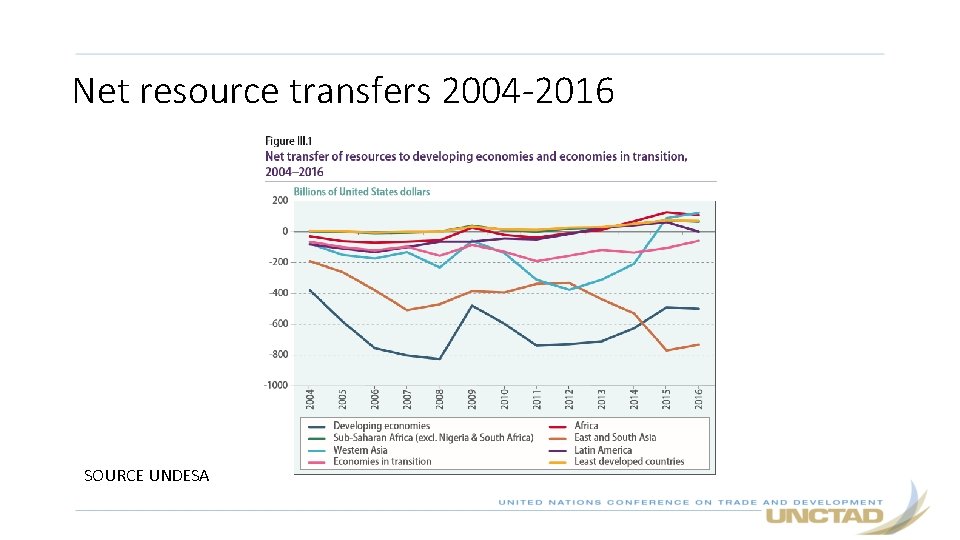

Net resource transfers 2004 -2016 SOURCE UNDESA

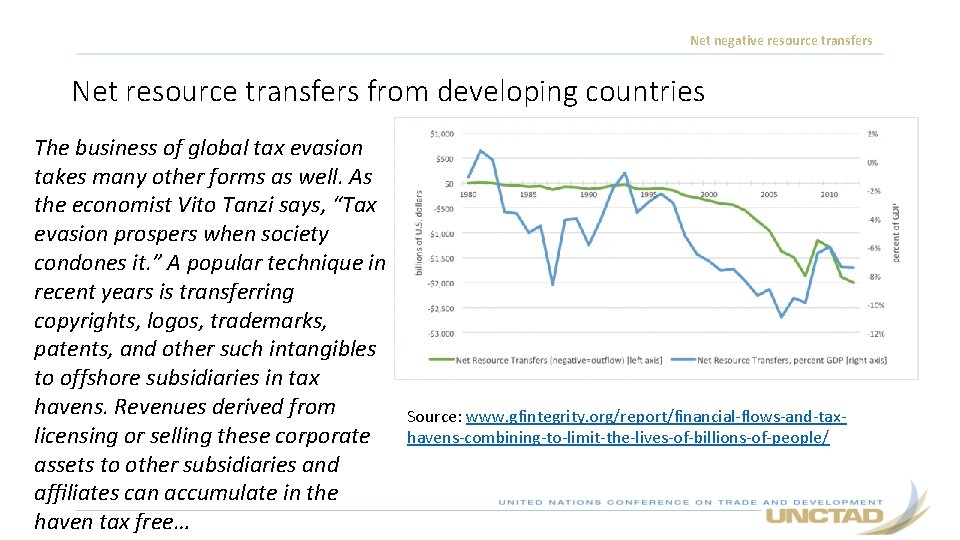

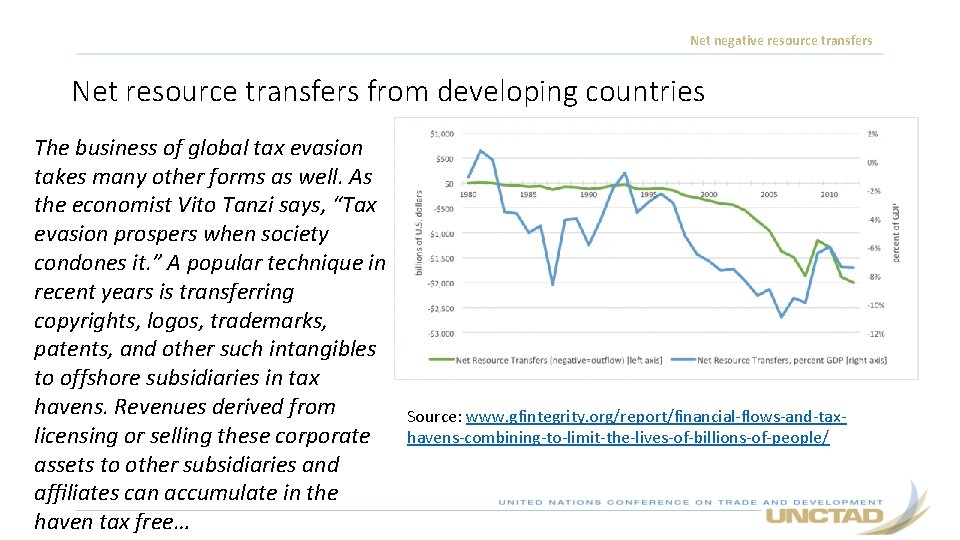

Net negative resource transfers Net resource transfers from developing countries The business of global tax evasion takes many other forms as well. As the economist Vito Tanzi says, “Tax evasion prospers when society condones it. ” A popular technique in recent years is transferring copyrights, logos, trademarks, patents, and other such intangibles to offshore subsidiaries in tax havens. Revenues derived from licensing or selling these corporate assets to other subsidiaries and affiliates can accumulate in the haven tax free… Source: www. gfintegrity. org/report/financial-flows-and-taxhavens-combining-to-limit-the-lives-of-billions-of-people/

ODA • ODA has been the primary quantitative measure of international development cooperation since 1969, ix with a target for developed countries to provide 0. 7 percent of their income as ODA established in 1970. However, only a small number of countries have ever reached the target, and in 2016, ODA represented only 0. 32 percent of donors’ GNI, despite consistent increases in real terms over the past 20 years. Figures for south-south cooperation are also being developed, showing it to be a smaller but important resource. The usefulness of the ODA figures as a measure of international development cooperation resources available to developing countries is weakened by the inclusion of several categories of in-donor costs, particularly refugee costs. Finally, additional commitments to debt relief, and to provide US$100 billion annually in climate finance are not being reliably measured due to double counting, with the same resources also being counted as ODA.

Broken promises and alternatives • Over recent years, the most important common denominator of rising debt vulnerabilities across developing countries has been their ad-hoc exposure to the volatility of international financial markets. • With international public finance flows falling short of commitments and limited access to concessional resources, developing countries have increasingly raised development finance on commercial terms in developed country financial markets, have opened their domestic financial markets to non-resident investors, and have allowed their citizens to borrow and invest abroad. • While increased access to international financial markets can make it easier for capital-scarce developing countries to raise much needed finance quickly, it also exposes them to the short-term and speculative logic of private investor expectations, associated sudden reversals of cross-border private capital flows and to a range of market risks they may be ill-equipped to manage appropriately. • In conjunction with other exogenous shocks, such as natural disasters or a sudden downturn of commodity prices – themselves at least partially determined by financial speculation - debt burdens that seemed reasonable under favorable conditions can quickly become unsustainable.

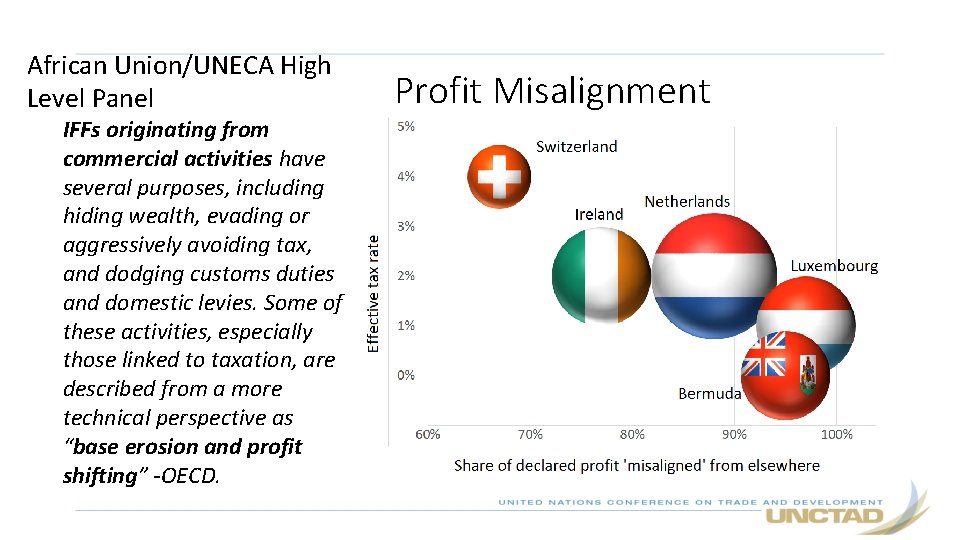

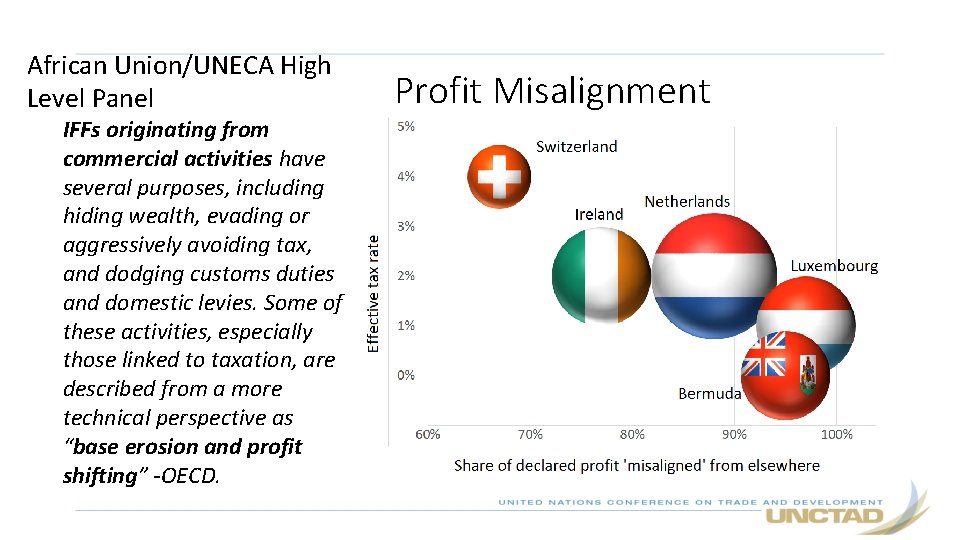

African Union/UNECA High Level Panel IFFs originating from commercial activities have several purposes, including hiding wealth, evading or aggressively avoiding tax, and dodging customs duties and domestic levies. Some of these activities, especially those linked to taxation, are described from a more technical perspective as “base erosion and profit shifting” -OECD. Profit Misalignment

Impact of profit shifting Company components § Work with existing quasi country-by-country reporting published by some tax transparency leaders, e. g. Vodafone, reveals significant variability at firm level. § Vodafone, 2016 -17 data: sum of positive, declared profits at the jurisdiction level is € 4. 128 bn. Misaligned profit is € 3. 574 bn, or 191% intensity of profit misalignment – e. g. of nearly € 1. 5 bn declared in Luxembourg, more than 99. 5% is not aligned with the real economic activity taking place there (as captured by employment and sales). The effective tax rate on these profits, according to Vodafone’s data, is around 0. 3%.

Passive stance can no longer be afforded • A core challenge to overcoming critical debt and financial vulnerabilities in developing countries is therefore to find ways of better matching long-term borrowing and re-financing needs with appropriate lending facilities and conditionalities to ensure long-term debt sustainability and avoid damaging debt traps. • This requires careful management of domestic credit and liquidity creation, and fine-tuned coordination with the use and conditionalities of external financing sources. • Having adopted a largely passive approach to the long-term management of diverse financial obligations and commitments in recent decades, many developing countries lack institutional and technical capacities to effectively design and implement long-term sustainable debt and financial policies and strategies.

BRI – exposure of capacity constraints • This constraint has become apparent also in the context of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). While the BRI, provides its partner developing countries with access to alternative external financing to short-term private capital flows from advanced economies, the transformative potential of the BRI has been hampered by difficulties in matching BRI financing with sound national and regional debt financing policies and strategies. • In some cases, this has deepened episodes of debt and financial distress, threatening to undermine prematurely the promise of the BRI to unlock structural transformation potential in its partner countries. • To be effective, it is essential that BRI financing needs are systematically paired with sound regional and national policies, not only in the key areas of infrastructure and industrial investment, trade and technology, but also in regard to ensuring viable longterm paths to financing productive investment. A core element of any such sustainable financing strategy are policies to prevent and mitigate episodes of debt distress in participant countries.

The way forward • Must roll back some of the destructive outcomes of global financialisation and corporate rentierism. • Strengthening domestic public policy spaces and capacities in developing countries to raise domestic public funds and ensuring both domestic and foreign private capital are reliably channelled into developmental investment projects whose short-to-medium term private profitability is uncertain is crucial (Blankenburg, 2018) • In the absence of an international monetary and financial system supportive of developing countries’ attempts to mobilise development finance, developing countries will have to prioritise South-South financial and economic cooperation and ensure that local, national and regional policy initiatives are connected and co-ordinated to limit the counterproductive influence of global financialisation. • Aim is to force international economic governance reform back onto the multilateral agenda • The two essential pillars of a viable financing for development agenda are domestic resource mobilisation and a system of international trade that prioritises, or at least facilitates, catching-up development (Ocampo et al, 2017)

‘Leveraging’ private finance for development – Is Blended finance the solution • There is no disagreement over the fact that private capital should be mobilised to co-finance development. The relevant question is how best this is to be achieved. • Beginning with the creation of structured mechanisms or blending platforms by the EU ‘blended’ development financing, has become the flavour of the month -the Addis Ababa Action Agenda (§ 48). • Blended finance refers to the use of international public finance, including official development assistance, to ‘leverage’ (primarily) private finance for developmental projects. Private sector instruments (PSIs), such as public loan guarantees, public-private partnerships, investment grants, technical assistance, equity investment and first-loss-for-public-sector-entities policies, are subsidies meant to promote fair risk- and cost-sharing.

‘Leveraging’ private finance for development • While foreign corporate capital may need to be mobilised, the essential task of developmental ‘financial risk management’ is to ensure that this capital can be reliably tied into long-term developmental projects, for example, through ‘blended’ financing instruments that include enforceable contractual obligations for multinational enterprises to reinvest (at least a substantial share of) their profits in these projects over long periods.

Regional solutions- payment and clearing systems • Regional monetary integration can make use of several arrangements and policies to strengthen macroeconomic stability in the region, buffer (monetary) exogenous shocks, provide access to countercyclical liquidity and promote intra-regional trade outside the dollar hegemony. • In practice, regional payment systems and clearing unions have a long history of facilitating financial resource mobilisation for catching-up development, if only temporarily. The most advanced forms of regional payment unions and clearing houses flourished in Western Europe after the Second World War to ensure rapid recovery of future US allies from war destruction, through the European Payment Union (EPU, 1950– 58) and for the recipients of the US Marshall Plan under the Economic Cooperation Administration (Kregel, 2018: 73, 89– 93, UNCTAD, 2011: 34– 37).

Regional payment systems and clearing unions: harnessing the power of credit creation • Provide some respite from exposure to destabilising global – capital flow and trade – shocks largely emanating from policy decisions in advanced economies. . • But for regional clearing unions to function properly in the interest of freeing up their own financial resources and policy space to pursue national development strategies, there also has to be the political will and insight, among developing country governments, to put regional before national developmental interests, in the understanding that reverse priorities will, ultimately, undermine isolated national development strategies in a hyper-globalised world economy that puts corporate rentierism before development.

Not all bleak… • Regional and inter-regional monetary and financial cooperation between developing countries is the most realistic way forward, at present, to stem the corrosive influence of corporate profiteering and financialisation on development financing and hence debt sustainability. • Unless a new path is found for developing countries, debt sustainability will remain a burden and millstone weighing on balanced growth and development. • Creating a dense and flexible network of local, national and regional state-led financial institutions in developing countries that can deliver credit and finance for development under public control offers an alternative agenda to address the challenges of debt sustainability.