Treating simple and complex trauma What to do

- Slides: 47

Treating simple and complex trauma: What to do and when Martin Dorahy Department of Psychology University of Canterbury

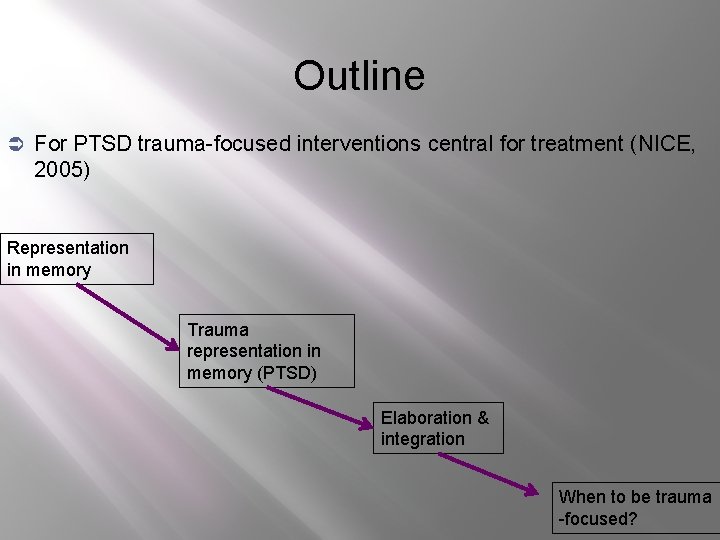

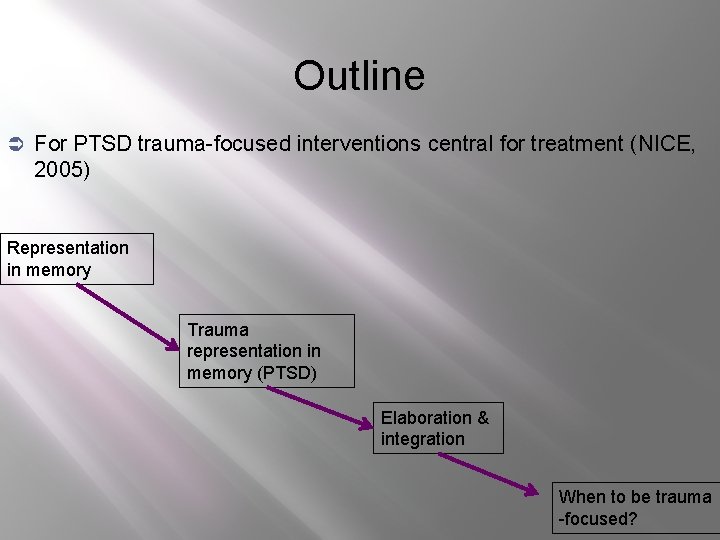

Outline Ü For PTSD trauma-focused interventions central for treatment (NICE, 2005) Representation in memory Trauma representation in memory (PTSD) Elaboration & integration When to be trauma -focused?

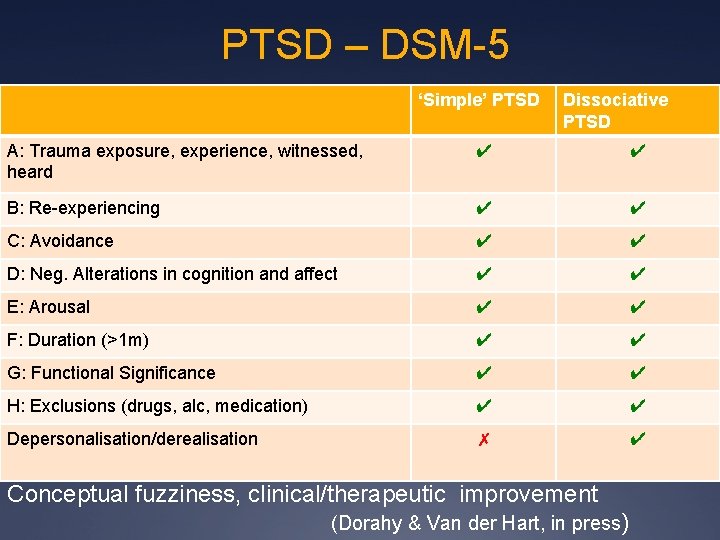

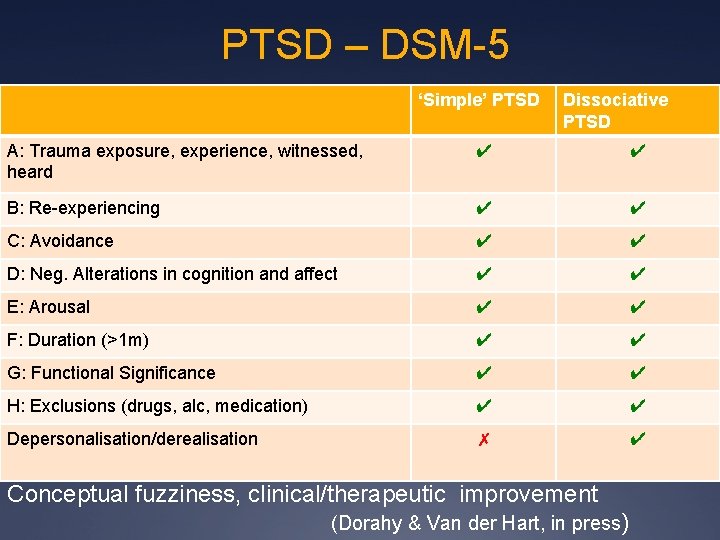

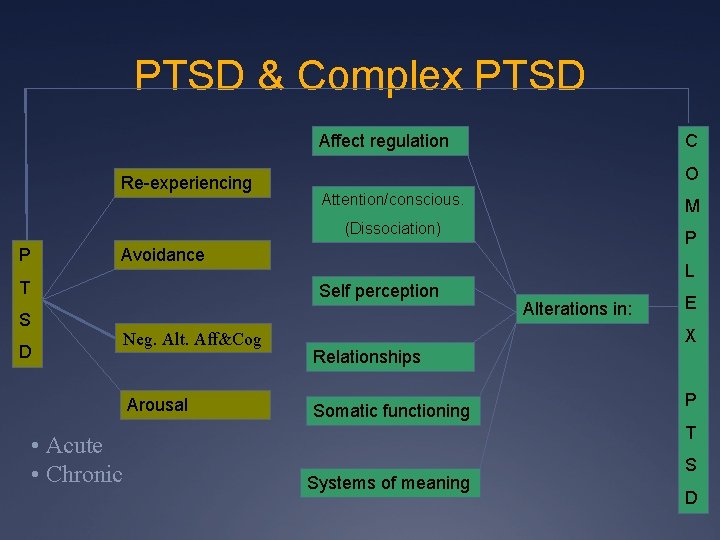

PTSD – DSM-5 ‘Simple’ PTSD Dissociative PTSD A: Trauma exposure, experience, witnessed, heard ✔ ✔ B: Re-experiencing ✔ ✔ C: Avoidance ✔ ✔ D: Neg. Alterations in cognition and affect ✔ ✔ E: Arousal ✔ ✔ F: Duration (>1 m) ✔ ✔ G: Functional Significance ✔ ✔ H: Exclusions (drugs, alc, medication) ✔ ✔ Depersonalisation/derealisation ✗ ✔ Conceptual fuzziness, clinical/therapeutic improvement (Dorahy & Van der Hart, in press)

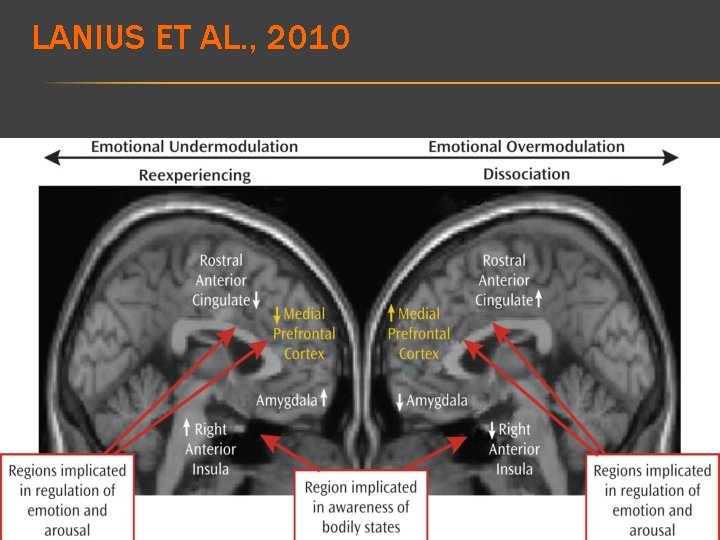

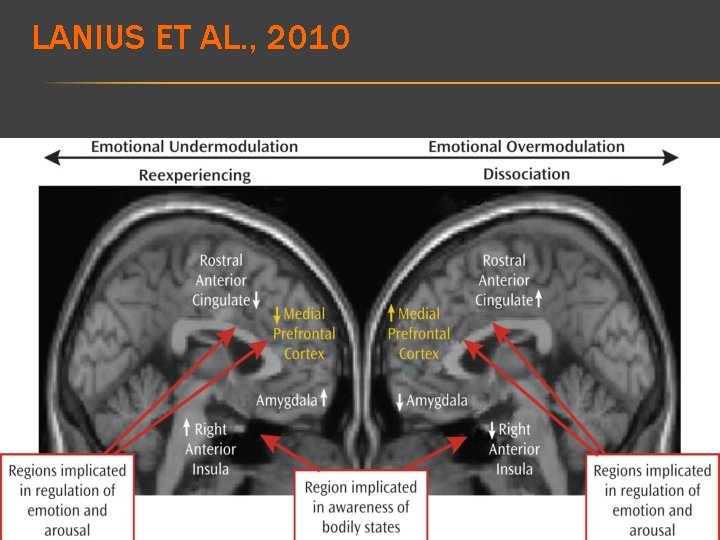

Modulation: Over or under Type of PTSD Ü 2 types of PTSD as found in neuroimaging Ü Arousal/reliving (undermodulated) Ü Dissociative (overmodulated)

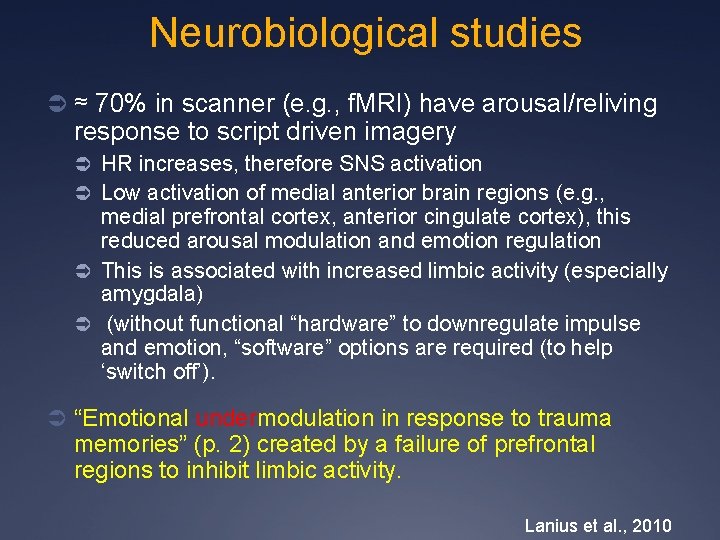

Neurobiological studies Ü ≈ 70% in scanner (e. g. , f. MRI) have arousal/reliving response to script driven imagery Ü HR increases, therefore SNS activation Ü Low activation of medial anterior brain regions (e. g. , medial prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex), this reduced arousal modulation and emotion regulation Ü This is associated with increased limbic activity (especially amygdala) Ü (without functional “hardware” to downregulate impulse and emotion, “software” options are required (to help ‘switch off’). Ü “Emotional undermodulation in response to trauma memories” (p. 2) created by a failure of prefrontal regions to inhibit limbic activity. Lanius et al. , 2010

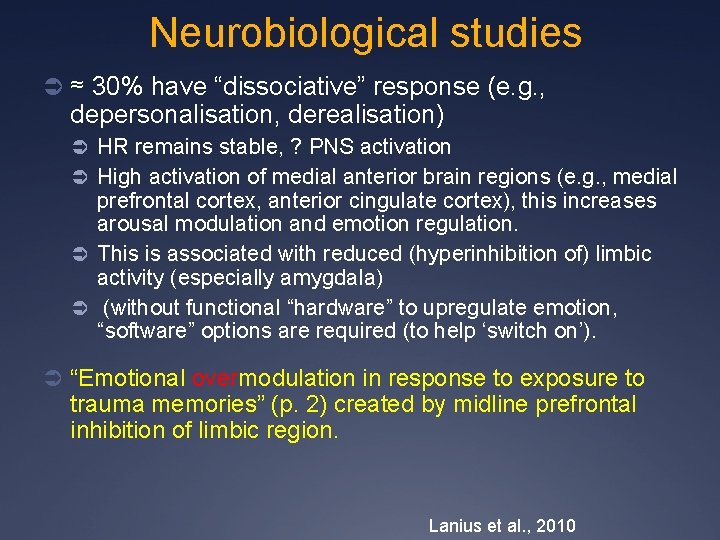

Neurobiological studies Ü ≈ 30% have “dissociative” response (e. g. , depersonalisation, derealisation) Ü HR remains stable, ? PNS activation Ü High activation of medial anterior brain regions (e. g. , medial prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex), this increases arousal modulation and emotion regulation. Ü This is associated with reduced (hyperinhibition of) limbic activity (especially amygdala) Ü (without functional “hardware” to upregulate emotion, “software” options are required (to help ‘switch on’). Ü “Emotional overmodulation in response to exposure to trauma memories” (p. 2) created by midline prefrontal inhibition of limbic region. Lanius et al. , 2010

LANIUS ET AL. , 2010

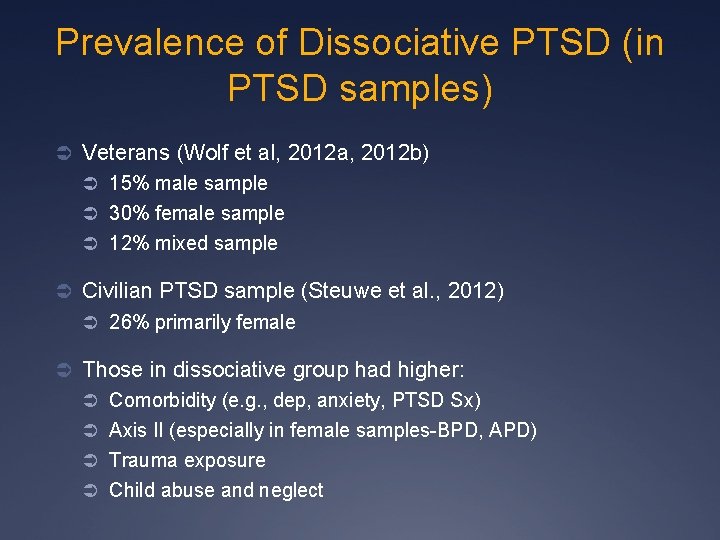

Prevalence of Dissociative PTSD (in PTSD samples) Ü Veterans (Wolf et al, 2012 a, 2012 b) Ü 15% male sample Ü 30% female sample Ü 12% mixed sample Ü Civilian PTSD sample (Steuwe et al. , 2012) Ü 26% primarily female Ü Those in dissociative group had higher: Ü Comorbidity (e. g. , dep, anxiety, PTSD Sx) Ü Axis II (especially in female samples-BPD, APD) Ü Trauma exposure Ü Child abuse and neglect

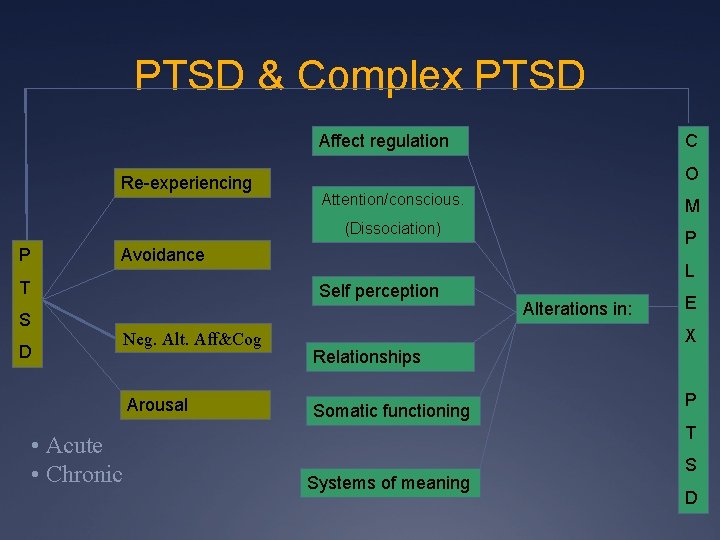

PTSD & Complex PTSD Affect regulation Re-experiencing C O Attention/conscious. M (Dissociation) P P Avoidance T L Self perception S D Neg. Alt. Aff&Cog Arousal • Acute • Chronic Alterations in: E X Relationships Somatic functioning P T Systems of meaning S D

PTSD: Event or memory? Ü According to DSM-5 PTSD is the result of an event that has the following characteristics: Ü The person was exposed to: death, threatened death, actual or threatened serious injury, or actual or threatened sexual violence, as follows Ü Direct exposure. Ü Witnessing, in person. Ü Indirectly, by learning that a close relative or close friend was exposed to trauma Ü Repeated or extreme indirect exposure to aversive details of the event(s), usually in the course of professional duties Ü But we know PTSD isn’t result of event, but rather is the result of an internal representation of that event (i. e. , memory). Ü Thus, PTSD is a disorder of memory • Brewin (2011, 2014); Rubin et al. (2008)

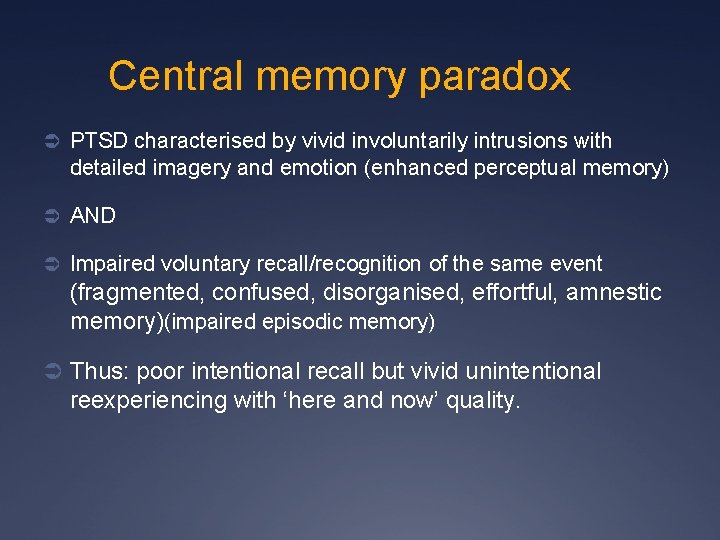

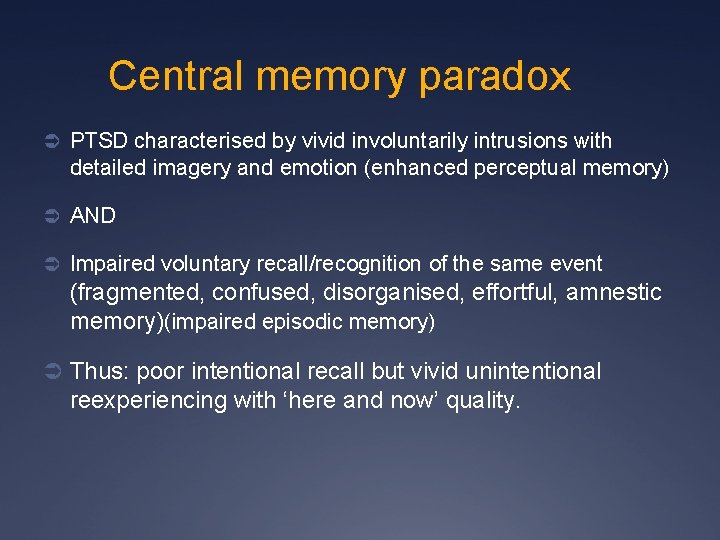

Central memory paradox Ü PTSD characterised by vivid involuntarily intrusions with detailed imagery and emotion (enhanced perceptual memory) Ü AND Ü Impaired voluntary recall/recognition of the same event (fragmented, confused, disorganised, effortful, amnestic memory)(impaired episodic memory) Ü Thus: poor intentional recall but vivid unintentional reexperiencing with ‘here and now’ quality.

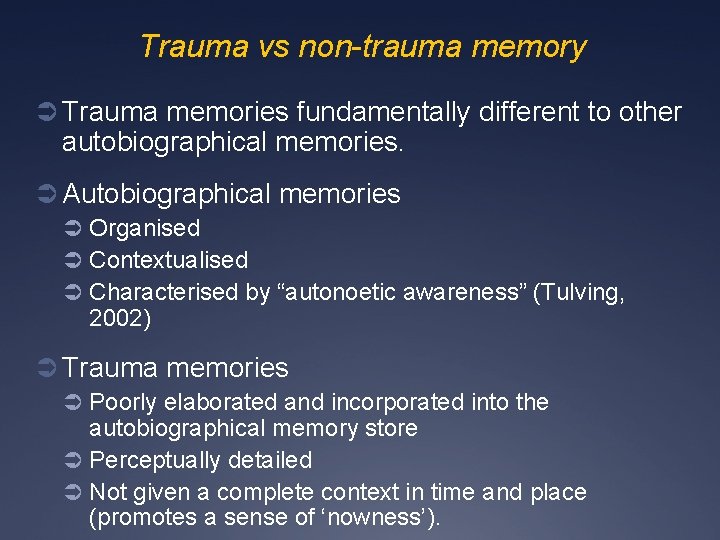

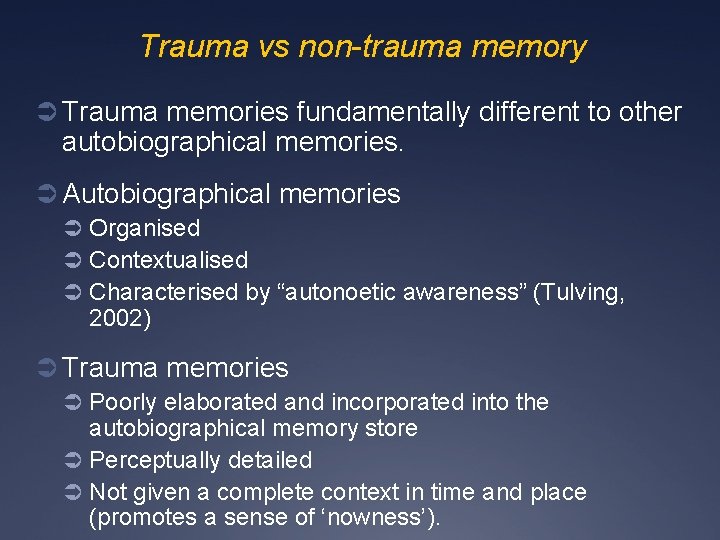

Trauma vs non-trauma memory Ü Trauma memories fundamentally different to other autobiographical memories. Ü Autobiographical memories Ü Organised Ü Contextualised Ü Characterised by “autonoetic awareness” (Tulving, 2002) Ü Trauma memories Ü Poorly elaborated and incorporated into the autobiographical memory store Ü Perceptually detailed Ü Not given a complete context in time and place (promotes a sense of ‘nowness’).

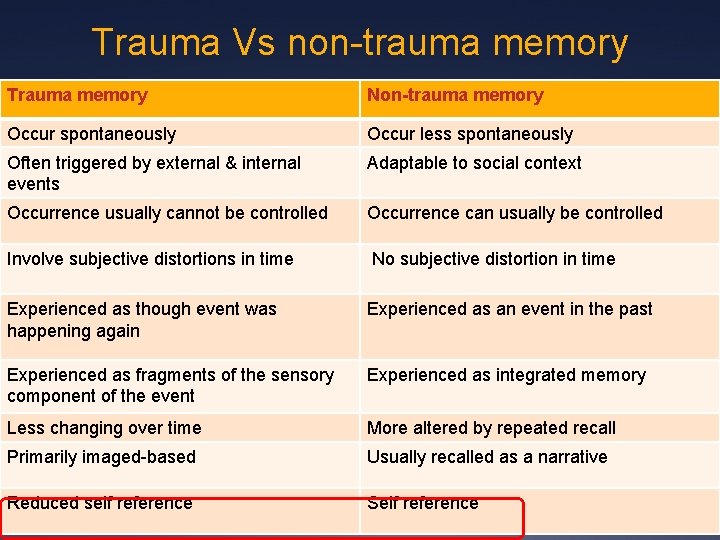

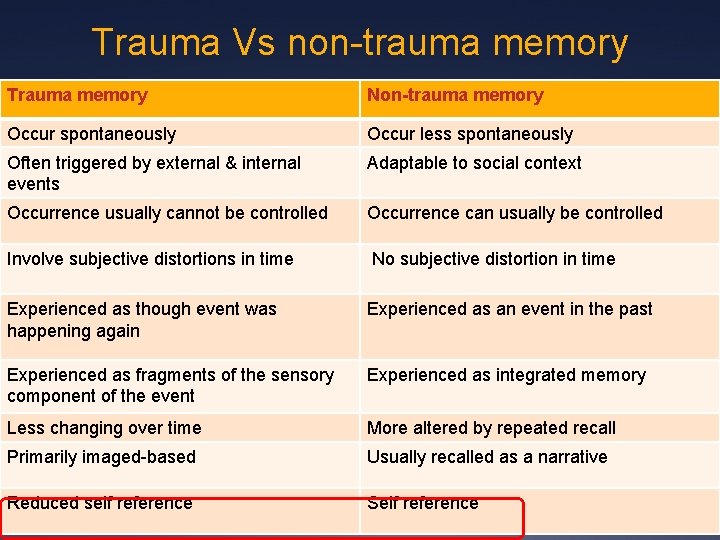

Trauma Vs non-trauma memory Trauma memory Non-trauma memory Occur spontaneously Occur less spontaneously Often triggered by external & internal events Adaptable to social context Occurrence usually cannot be controlled Occurrence can usually be controlled Involve subjective distortions in time No subjective distortion in time Experienced as though event was happening again Experienced as an event in the past Experienced as fragments of the sensory component of the event Experienced as integrated memory Less changing over time More altered by repeated recall Primarily imaged-based Usually recalled as a narrative Reduced self reference Self reference

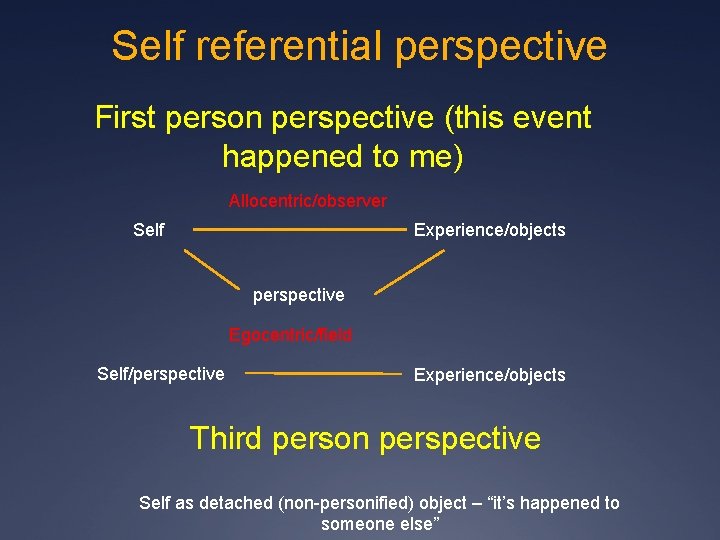

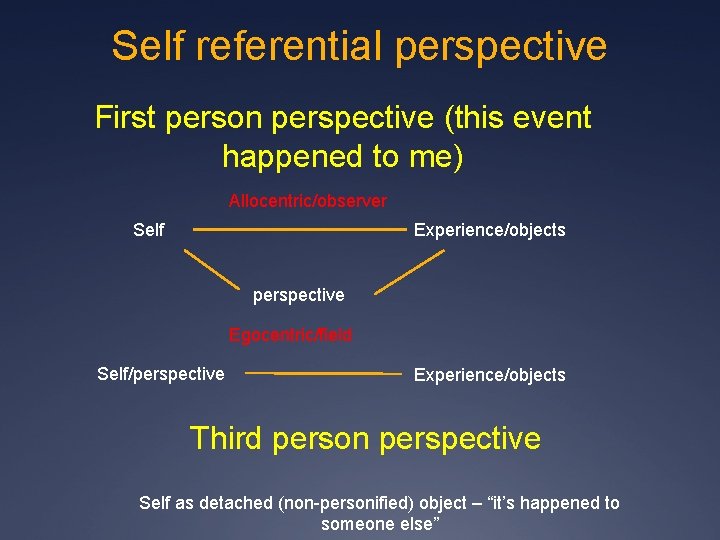

Self referential perspective First person perspective (this event happened to me) Allocentric/observer Self Experience/objects perspective Egocentric/field Self/perspective Experience/objects Third person perspective Self as detached (non-personified) object – “it’s happened to someone else”

Ü “Acute trauma may simultaneously diminish neural activity in anatomical structures serving conscious processing and enhance activity in structures serving perception” (Brewin, 2014, p. 70) Ü But how do we understand this psychologically?

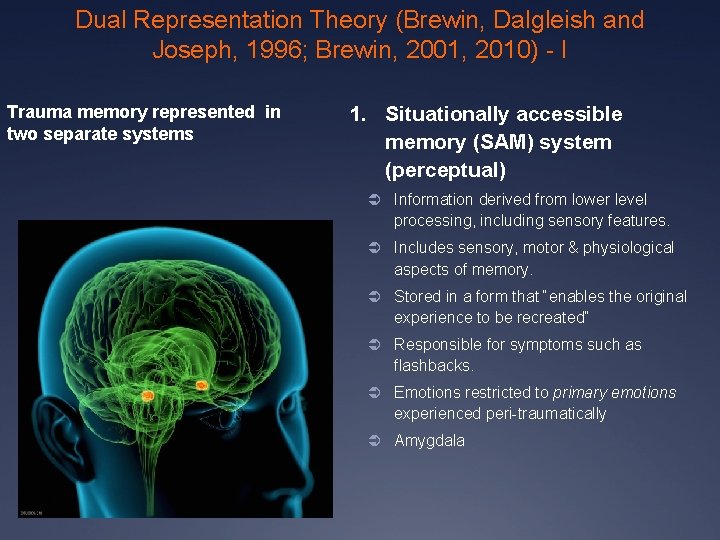

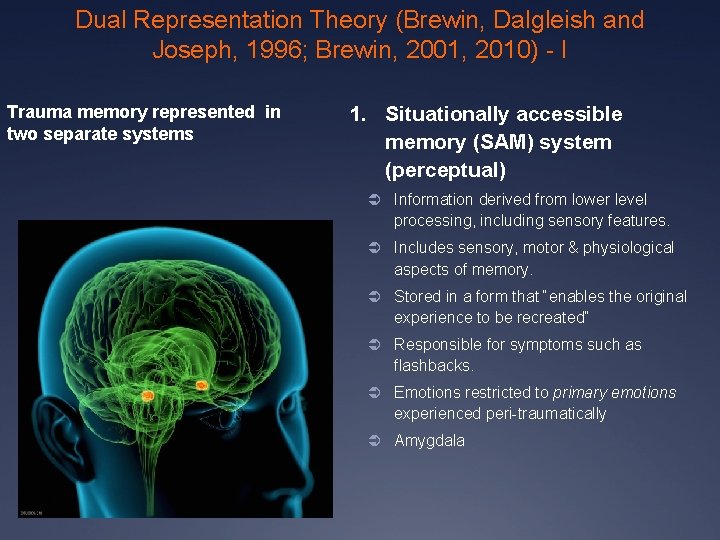

Dual Representation Theory (Brewin, Dalgleish and Joseph, 1996; Brewin, 2001, 2010) - I Trauma memory represented in two separate systems 1. Situationally accessible memory (SAM) system (perceptual) Ü Information derived from lower level processing, including sensory features. Ü Includes sensory, motor & physiological aspects of memory. Ü Stored in a form that “enables the original experience to be recreated” Ü Responsible for symptoms such as flashbacks. Ü Emotions restricted to primary emotions experienced peri-traumatically Ü Amygdala

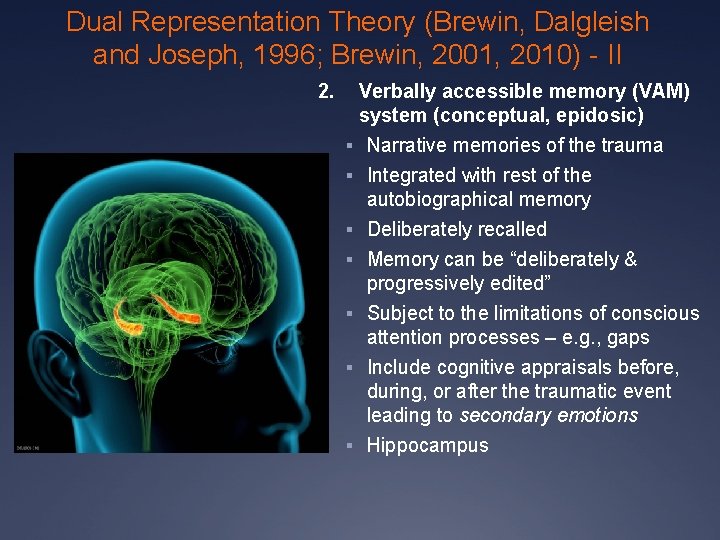

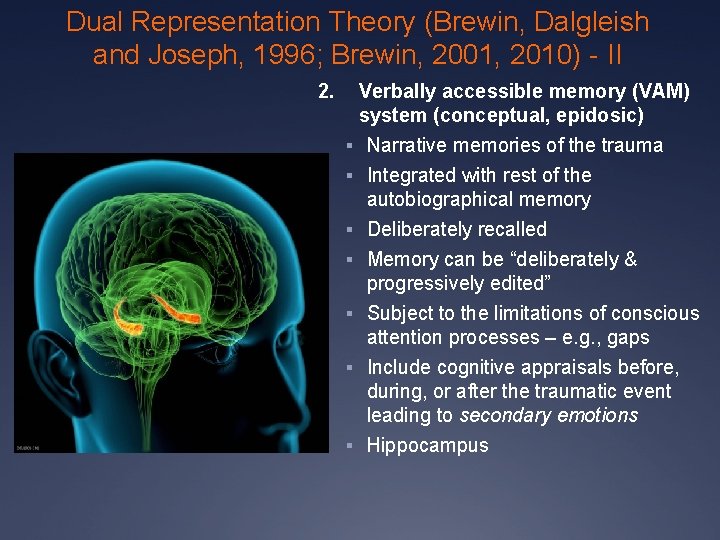

Dual Representation Theory (Brewin, Dalgleish and Joseph, 1996; Brewin, 2001, 2010) - II 2. Verbally accessible memory (VAM) system (conceptual, epidosic) Narrative memories of the trauma Integrated with rest of the autobiographical memory Deliberately recalled Memory can be “deliberately & progressively edited” Subject to the limitations of conscious attention processes – e. g. , gaps Include cognitive appraisals before, during, or after the traumatic event leading to secondary emotions Hippocampus

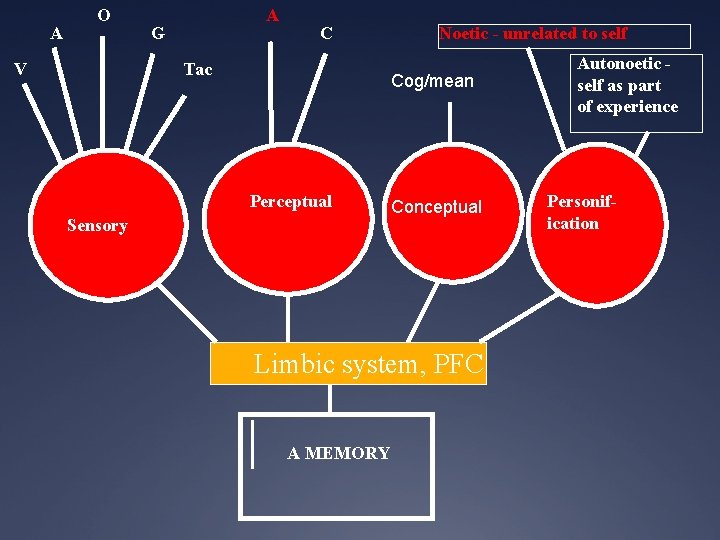

What do you see (perceive) & understand (conceive)?

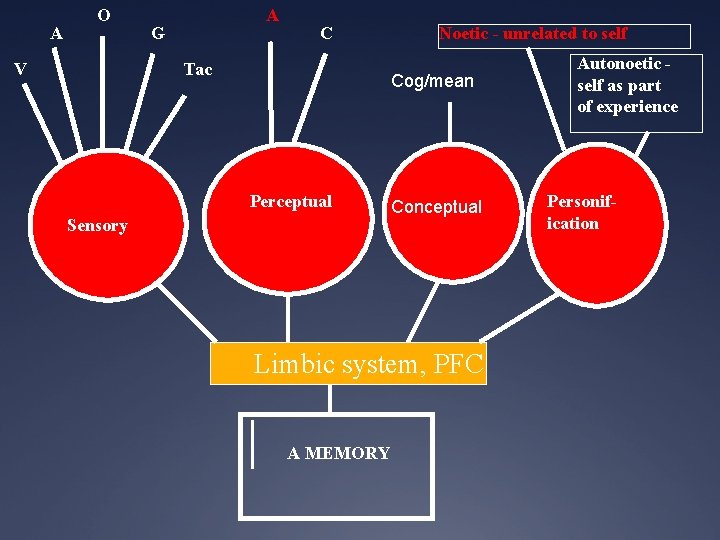

A O A G C Tac V Noetic - unrelated to self Cog/mean Perceptual Sensory Conceptual Limbic system, PFC A MEMORY Autonoetic self as part of experience Personification

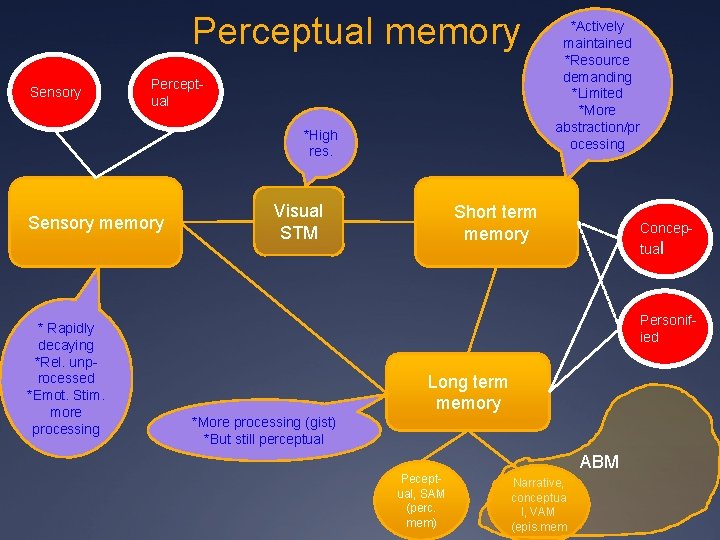

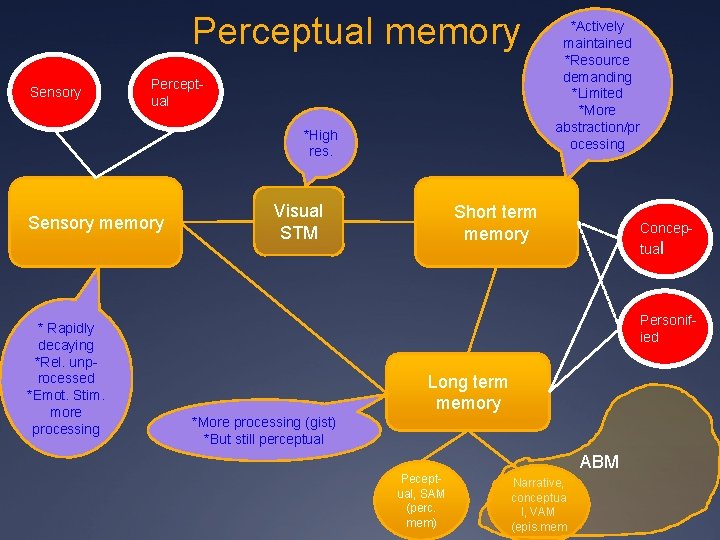

Perceptual memory Sensory Perceptual *High res. Sensory memory * Rapidly decaying *Rel. unprocessed *Emot. Stim. more processing Visual STM *Actively maintained *Resource demanding *Limited *More abstraction/pr ocessing Short term memory Conceptual Personified Long term memory *More processing (gist) *But still perceptual ABM Peceptual, SAM (perc. mem) Narrative, conceptua l, VAM (epis. mem

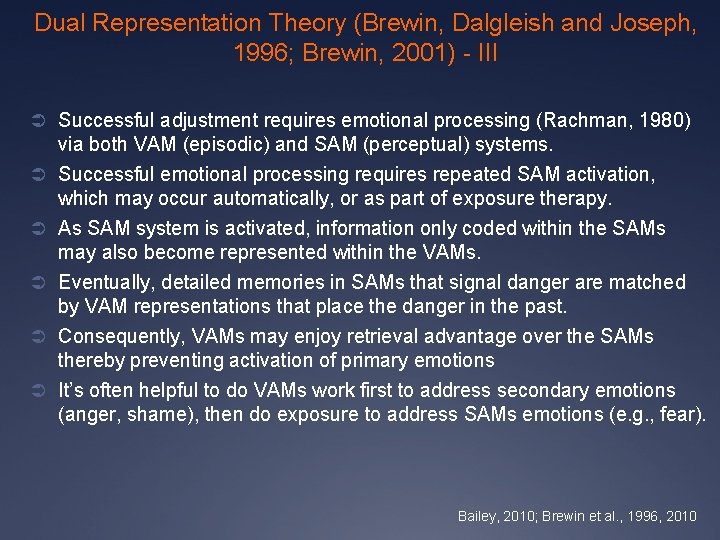

Dual Representation Theory (Brewin, Dalgleish and Joseph, 1996; Brewin, 2001) - III Ü Successful adjustment requires emotional processing (Rachman, 1980) via both VAM (episodic) and SAM (perceptual) systems. Ü Successful emotional processing requires repeated SAM activation, Ü Ü which may occur automatically, or as part of exposure therapy. As SAM system is activated, information only coded within the SAMs may also become represented within the VAMs. Eventually, detailed memories in SAMs that signal danger are matched by VAM representations that place the danger in the past. Consequently, VAMs may enjoy retrieval advantage over the SAMs thereby preventing activation of primary emotions It’s often helpful to do VAMs work first to address secondary emotions (anger, shame), then do exposure to address SAMs emotions (e. g. , fear). Bailey, 2010; Brewin et al. , 1996, 2010

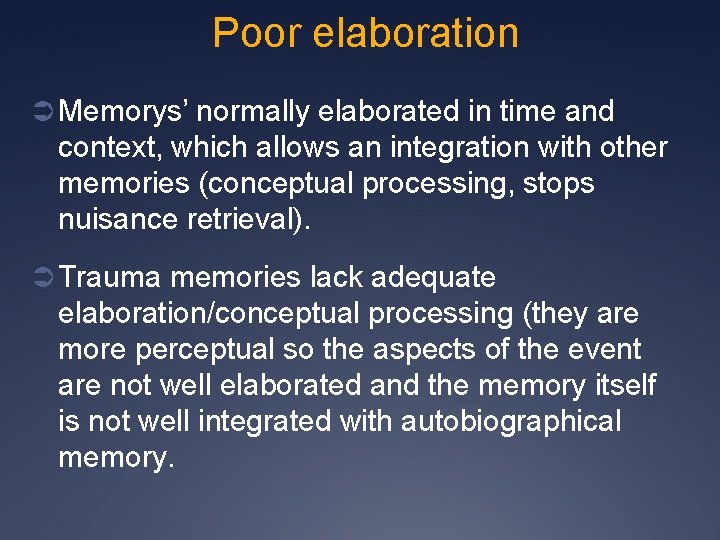

Poor elaboration Ü Memorys’ normally elaborated in time and context, which allows an integration with other memories (conceptual processing, stops nuisance retrieval). Ü Trauma memories lack adequate elaboration/conceptual processing (they are more perceptual so the aspects of the event are not well elaborated and the memory itself is not well integrated with autobiographical memory.

Influences on memory Ü Dissociation assoc with more perc. and less self reference (e. g. , Lyttle, Dorahy, Hanna, & Huntjens, 2010 ; Van der Hart et al. , 2006)

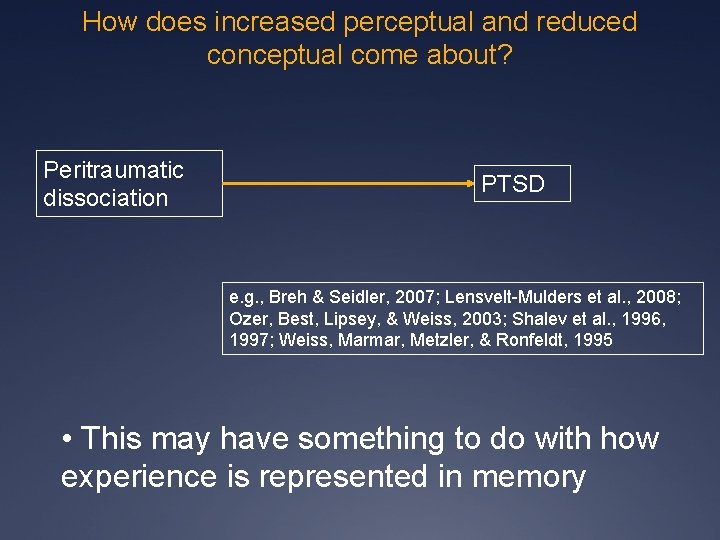

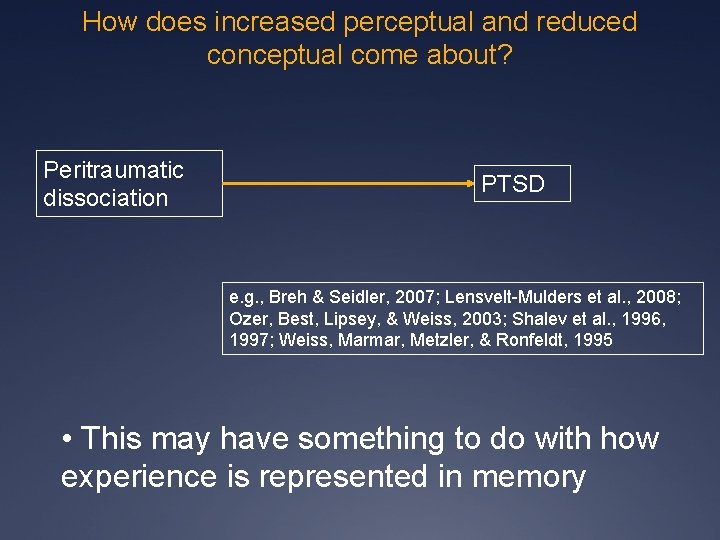

How does increased perceptual and reduced conceptual come about? Peritraumatic dissociation PTSD e. g. , Breh & Seidler, 2007; Lensvelt-Mulders et al. , 2008; Ozer, Best, Lipsey, & Weiss, 2003; Shalev et al. , 1996, 1997; Weiss, Marmar, Metzler, & Ronfeldt, 1995 • This may have something to do with how experience is represented in memory

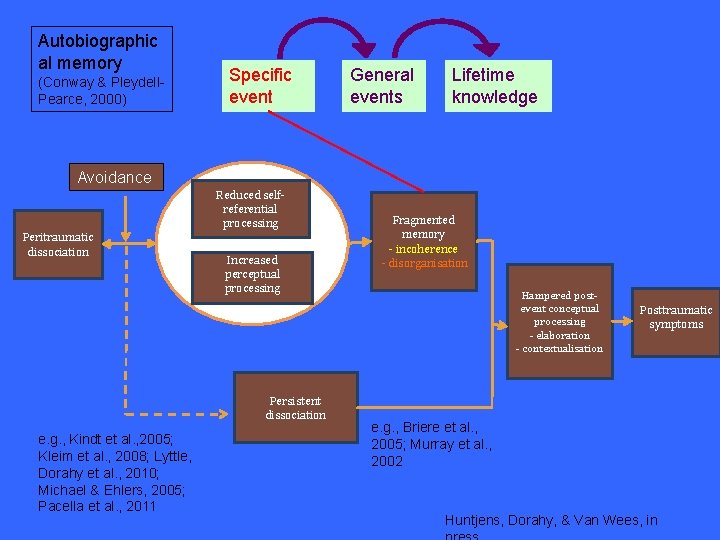

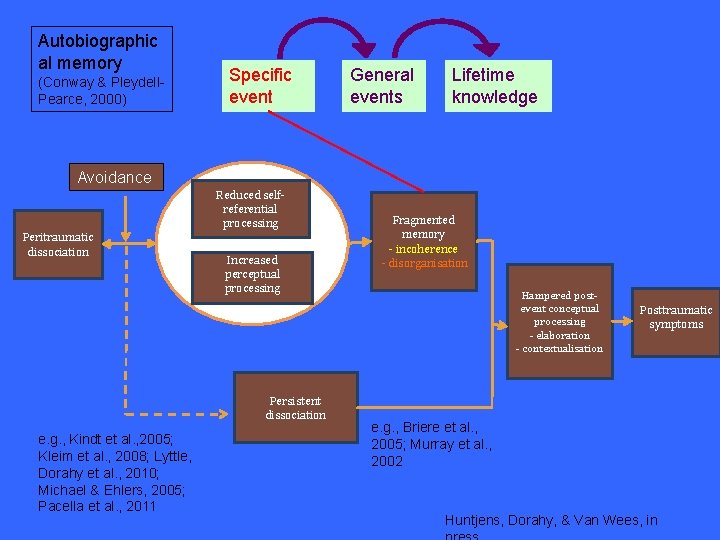

Autobiographic al memory (Conway & Pleydell. Pearce, 2000) Specific event General events Lifetime knowledge Avoidance Peritraumatic dissociation Reduced selfreferential processing Increased perceptual processing Persistent dissociation e. g. , Kindt et al. , 2005; Kleim et al. , 2008; Lyttle, Dorahy et al. , 2010; Michael & Ehlers, 2005; Pacella et al. , 2011 Fragmented memory - incoherence - disorganisation Hampered postevent conceptual processing - elaboration - contextualisation Posttraumatic symptoms e. g. , Briere et al. , 2005; Murray et al. , 2002 Huntjens, Dorahy, & Van Wees, in

Putting everything together

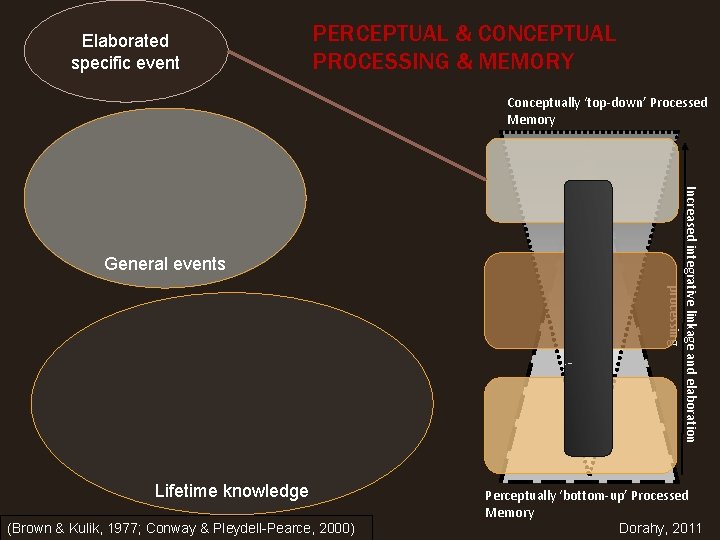

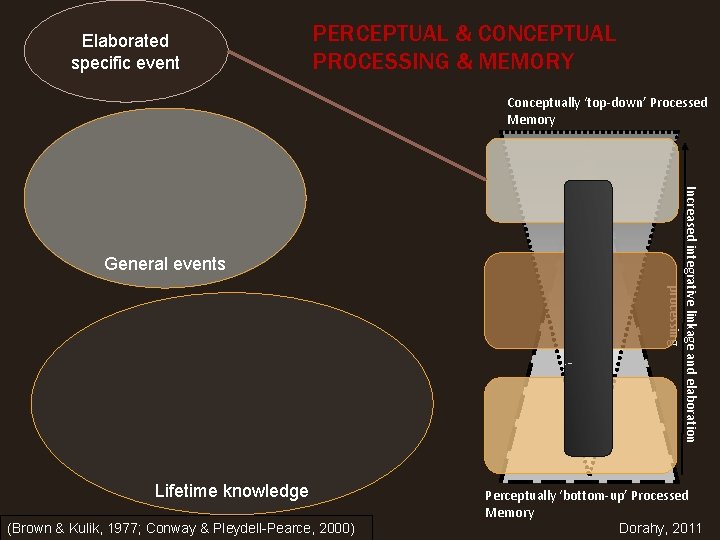

Elaborated specific event PERCEPTUAL & CONCEPTUAL PROCESSING & MEMORY Conceptually ‘top-down’ Processed Memory Lifetime knowledge (Brown & Kulik, 1977; Conway & Pleydell-Pearce, 2000) Increased integrative linkage and elaboration processing General events Perceptually ‘bottom-up’ Processed Memory Dorahy, 2011

2 principles of intervention Ü Elaboration of memory Ü Integration of memory Ü In that order, integration (connecting memory with other memories, autobiographical history and sense of self will be unsuccessful if memory unelaborated Ü But when do we engage in elaboration (trauma-focused) work?

Assessment (memory) Ü Characterise nature of trauma memory and spontaneous intrusions. Ü Detailed (crisp) percep. reps. Ü Rel. unchanged over time Ü Activate strong negative feelings Ü Gaps in memory Ü Where in sequence events are muddled, confused. Ü Extent to which memories have ‘here and now’ quality, and strong sensory & motor components. Ü Memory has field/egocentric perspective

Memory work Ü Identify hot spots Ü Challenge appraisals that thinking about T is unsafe, dangerous. Ü Facilitates elaboration and contextualisation of trauma memory

Memory work Ü Imaginal reliving: reliving experience in presence of therapist and putting into words Ü Relive experience in minds eye (images, thoughts, feelings, narrative Ü Present tense Ü ‘What do you see, hear, feel’, ‘where do you feel that’, ‘what’s going through your mind’ Ü After whole event narrated, further reliving of ‘hot spots’ or problematic aspects of memory

Memory work Ü With progressive reliving, narrative becomes more coherent, and sensory (e. g. , smells, tastes) and motor (e. g. , involuntary movements) components become elaborated and less pure (thereby fading)

Memory work Ü In vivo exposure can be used with therapist or as homework ÜMake sure past and present are differentiated Ü Imagery techniques to re-script trauma memory or facilitate grieving

When more complex symptoms, characterological issues and relational dynamics prevail. What then?

Move from Trauma focused to phase-oriented therapy

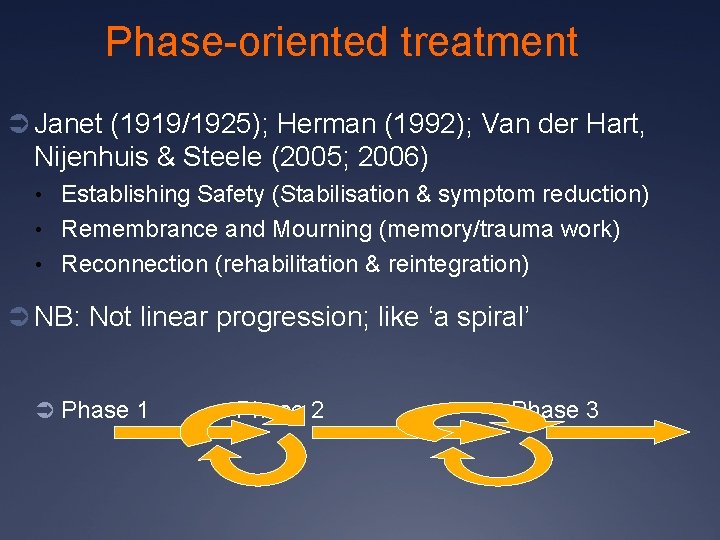

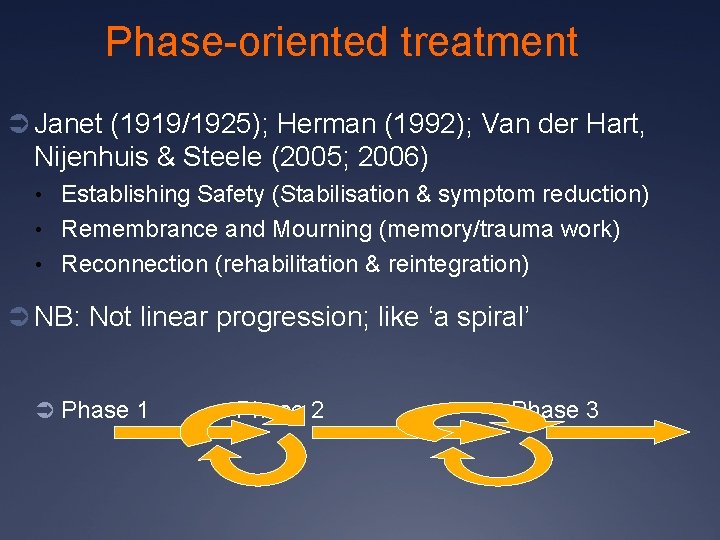

Phase-oriented treatment Ü Janet (1919/1925); Herman (1992); Van der Hart, Nijenhuis & Steele (2005; 2006) • Establishing Safety (Stabilisation & symptom reduction) • Remembrance and Mourning (memory/trauma work) • Reconnection (rehabilitation & reintegration) Ü NB: Not linear progression; like ‘a spiral’ Ü Phase 1 Phase 2 Phase 3

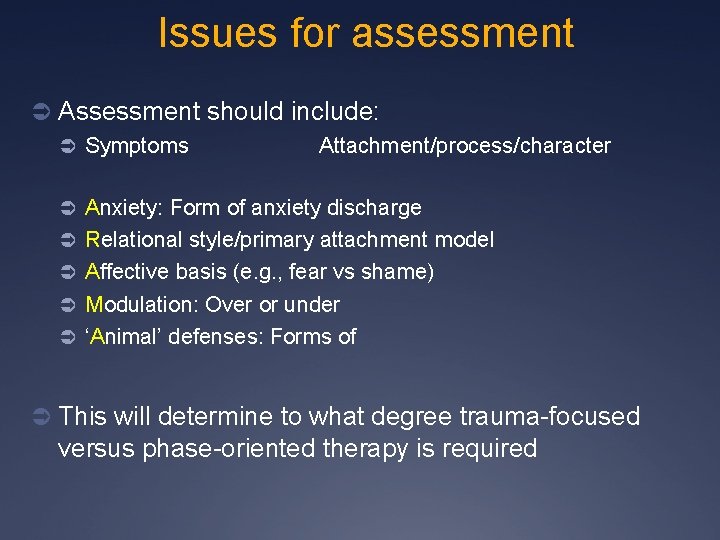

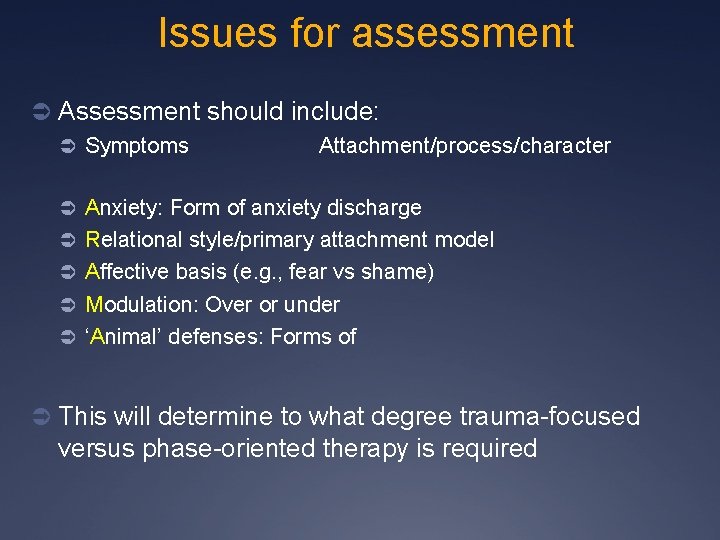

Issues for assessment Ü Assessment should include: Ü Symptoms Attachment/process/character Ü Anxiety: Form of anxiety discharge Ü Relational style/primary attachment model Ü Affective basis (e. g. , fear vs shame) Ü Modulation: Over or under Ü ‘Animal’ defenses: Forms of Ü This will determine to what degree trauma-focused versus phase-oriented therapy is required

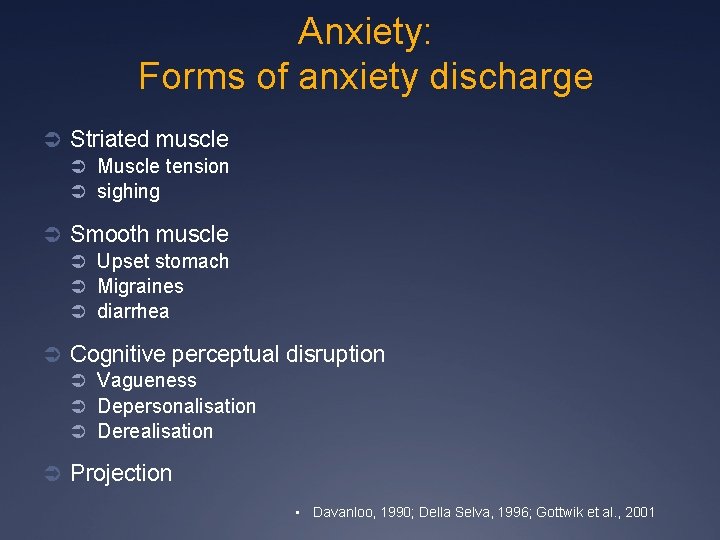

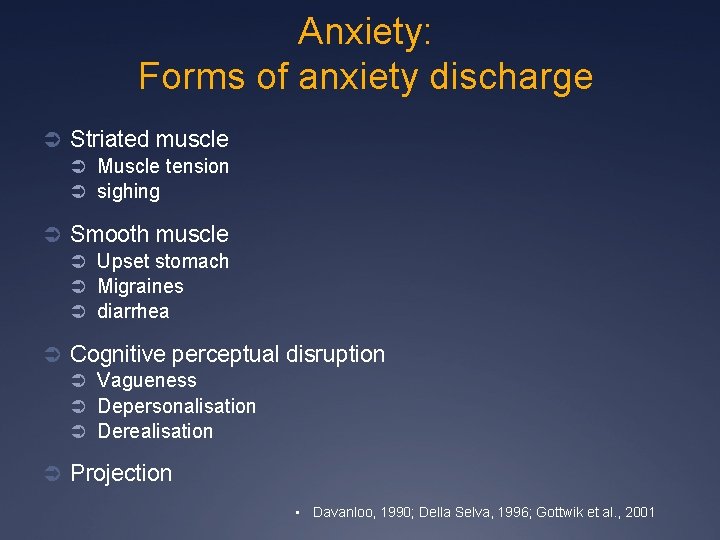

Anxiety: Forms of anxiety discharge Ü Striated muscle Ü Muscle tension Ü sighing Ü Smooth muscle Ü Upset stomach Ü Migraines Ü diarrhea Ü Cognitive perceptual disruption Ü Vagueness Ü Depersonalisation Ü Derealisation Ü Projection • Davanloo, 1990; Della Selva, 1996; Gottwik et al. , 2001

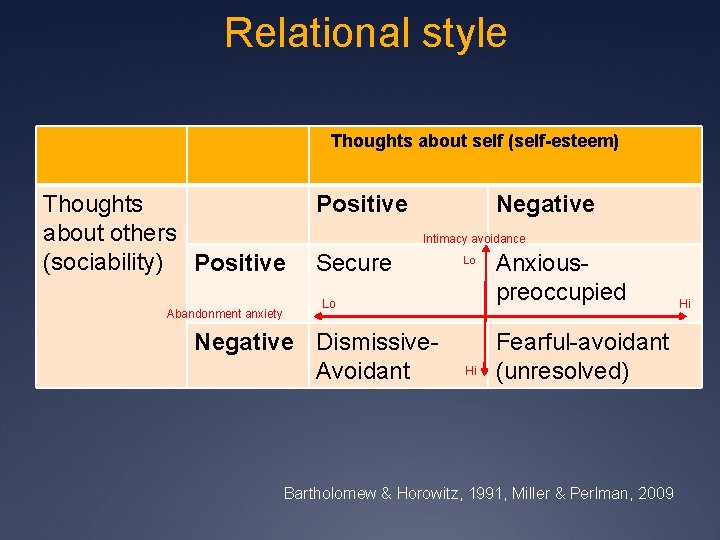

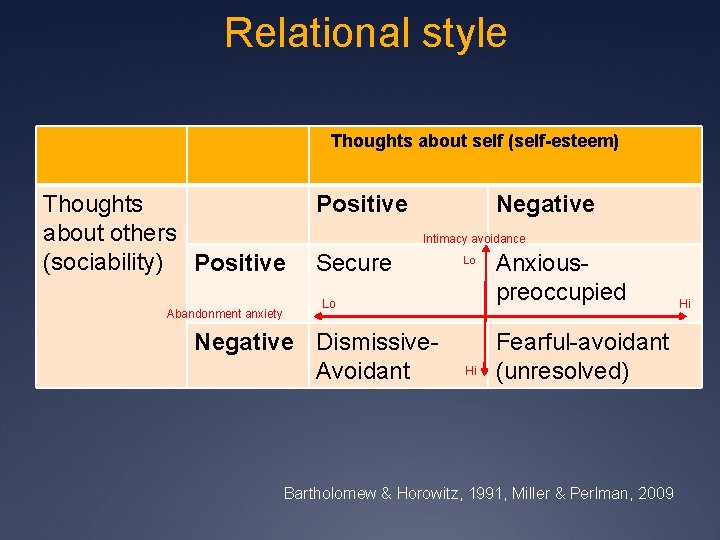

Relational style Thoughts about self (self-esteem) Thoughts about others (sociability) Positive Abandonment anxiety Positive Negative Intimacy avoidance Secure Lo Lo Negative Dismissive. Avoidant Hi Anxiouspreoccupied Fearful-avoidant (unresolved) Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991, Miller & Perlman, 2009 Hi

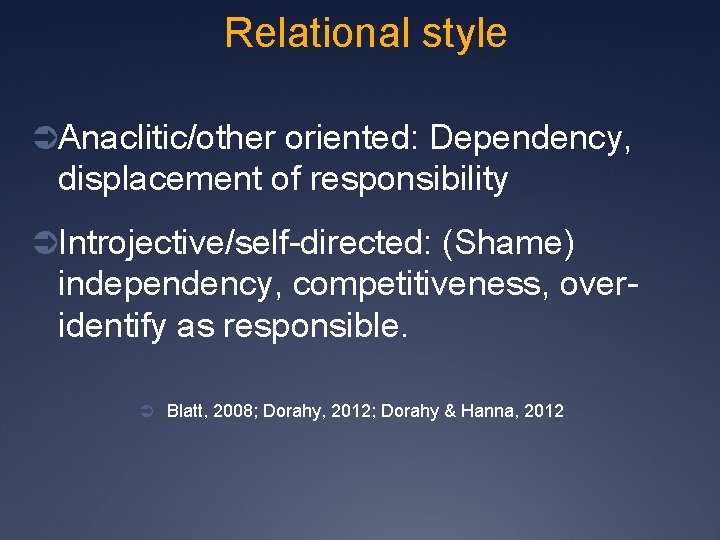

Relational style ÜAnaclitic/other oriented: Dependency, displacement of responsibility ÜIntrojective/self-directed: (Shame) independency, competitiveness, overidentify as responsible. Ü Blatt, 2008; Dorahy, 2012; Dorahy & Hanna, 2012

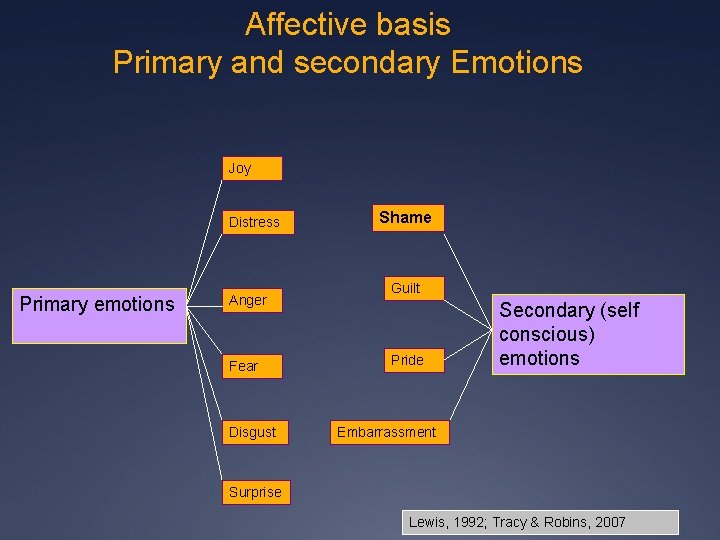

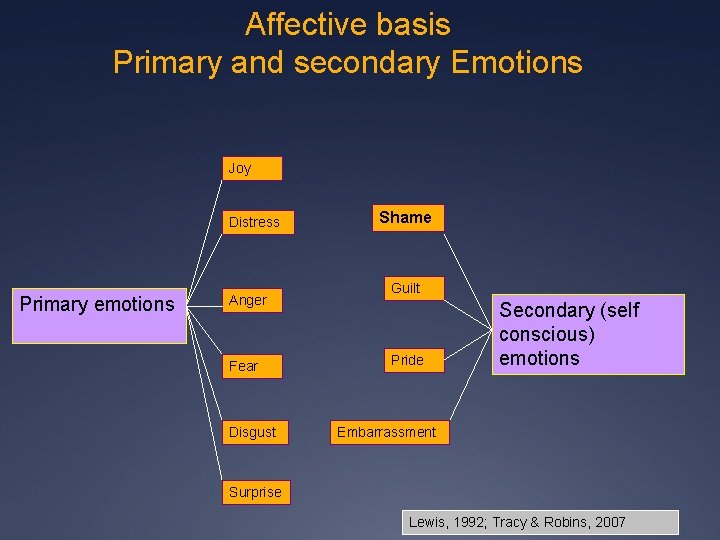

Affective basis Primary and secondary Emotions Joy Distress Primary emotions Anger Fear Disgust Shame Guilt Pride Secondary (self conscious) emotions Embarrassment Surprise Lewis, 1992; Tracy & Robins, 2007

Factors That Impede Emotional Processing Ü Lee, Scragg and Turner (2001) Ü Shame Ü Guilt Ü Humiliation

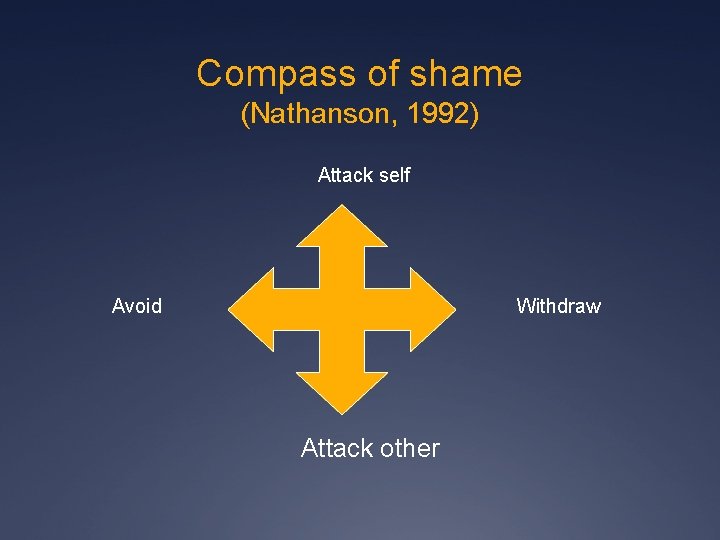

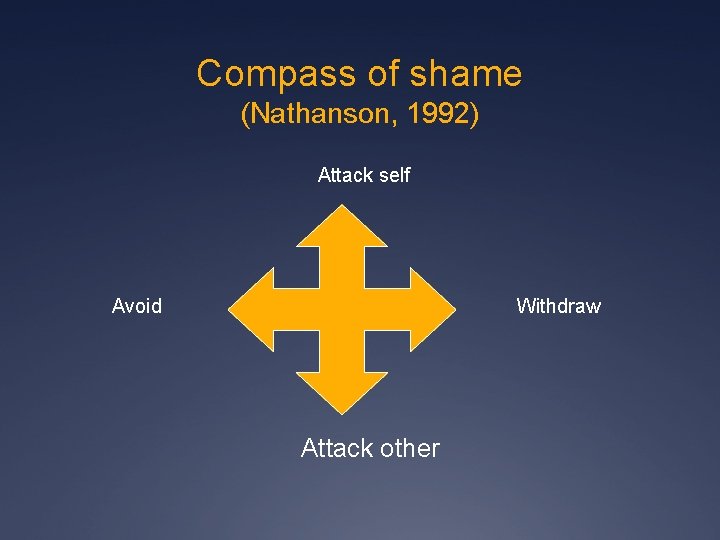

Compass of shame (Nathanson, 1992) Attack self Avoid Withdraw Attack other

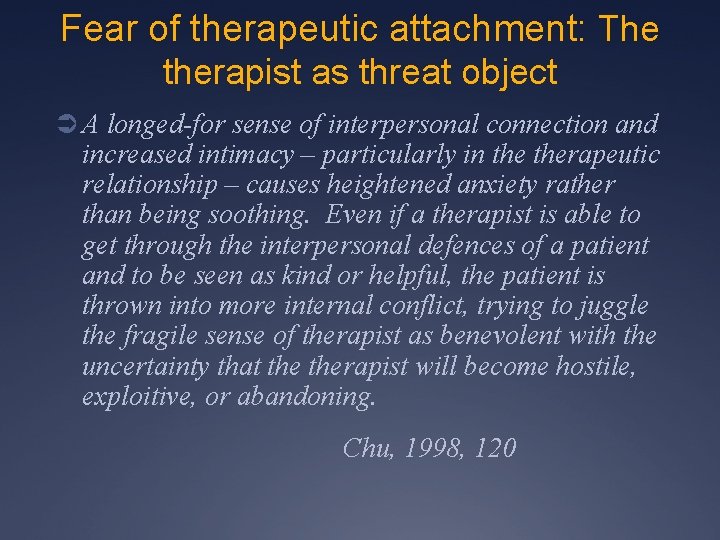

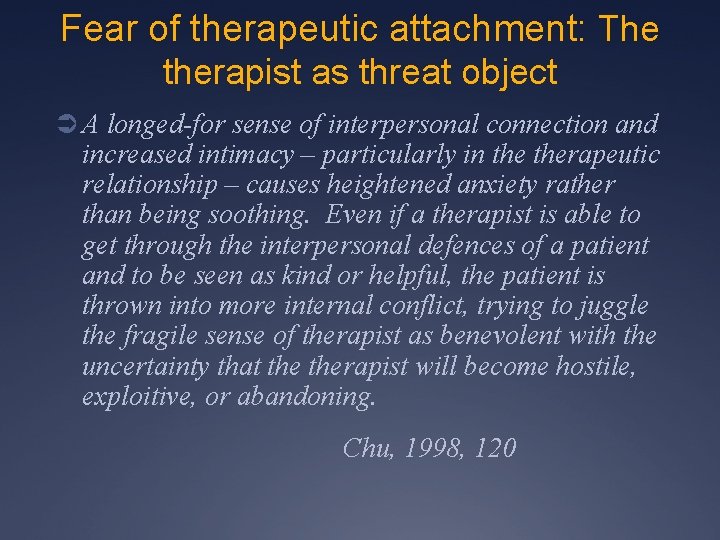

Fear of therapeutic attachment: The therapist as threat object Ü A longed-for sense of interpersonal connection and increased intimacy – particularly in therapeutic relationship – causes heightened anxiety rather than being soothing. Even if a therapist is able to get through the interpersonal defences of a patient and to be seen as kind or helpful, the patient is thrown into more internal conflict, trying to juggle the fragile sense of therapist as benevolent with the uncertainty that therapist will become hostile, exploitive, or abandoning. Chu, 1998, 120

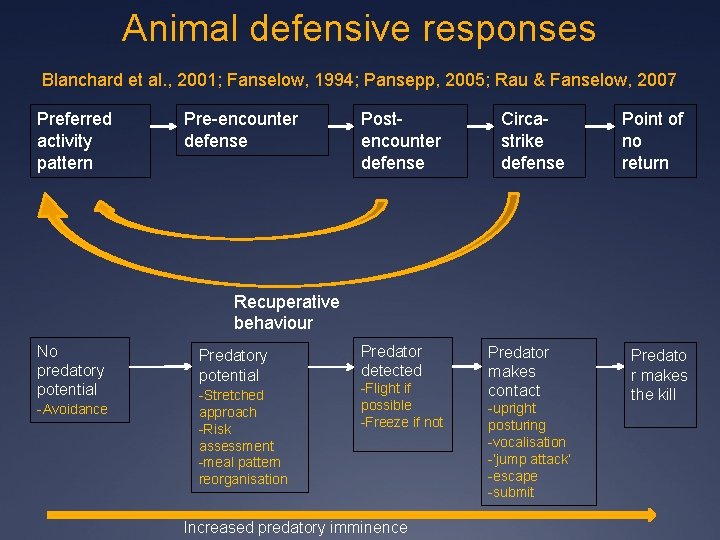

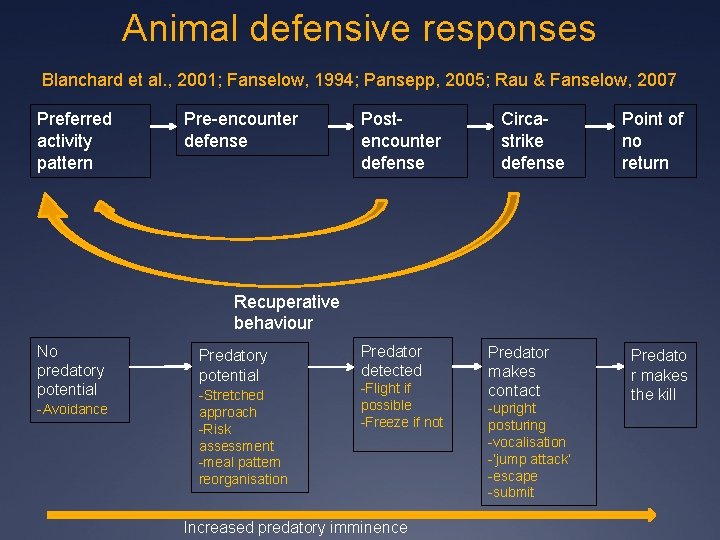

Animal defensive responses Blanchard et al. , 2001; Fanselow, 1994; Pansepp, 2005; Rau & Fanselow, 2007 Preferred activity pattern Pre-encounter defense Postencounter defense Circastrike defense Point of no return Recuperative behaviour No predatory potential -Avoidance Predatory potential -Stretched approach -Risk assessment -meal pattern reorganisation Predator detected -Flight if possible -Freeze if not Increased predatory imminence Predator makes contact -upright posturing -vocalisation -’jump attack’ -escape -submit Predato r makes the kill

Dissociation of animal defenses Secondary structural dissociation Dividedness amongst dissociative self-aware systems Trauma Emotional part of the personality (EP): e. g. , Submit Fight Freeze flight Apparently normal part of the personality (ANP) Driven by psychobiological systems of daily functioning • Attachment • Play • Seeking • self definition Van der Hart et al. , 2006; Nijenhuis, Van der Hart & Steele, 2002

Martin. dorahy@canterbury. ac. nz