TRAUMA Trauma is the psychological response to these

- Slides: 43

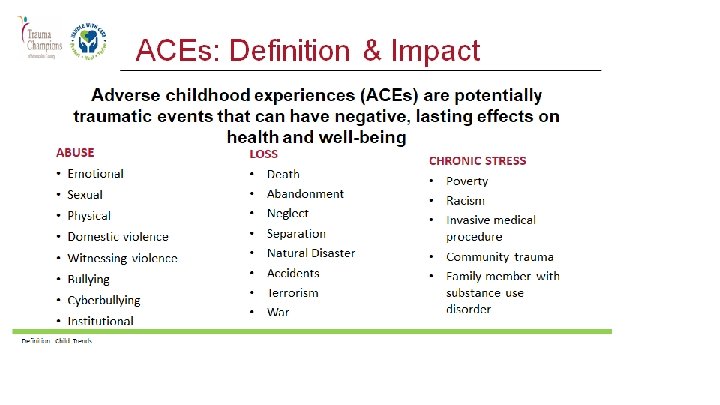

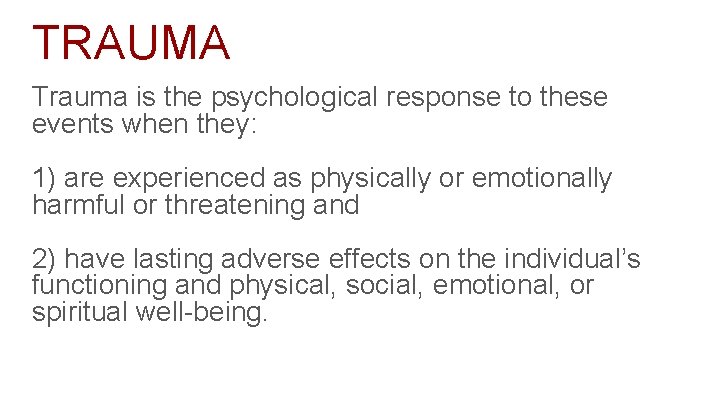

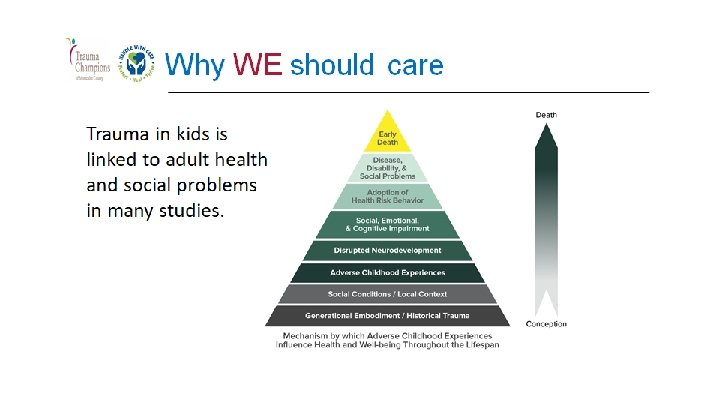

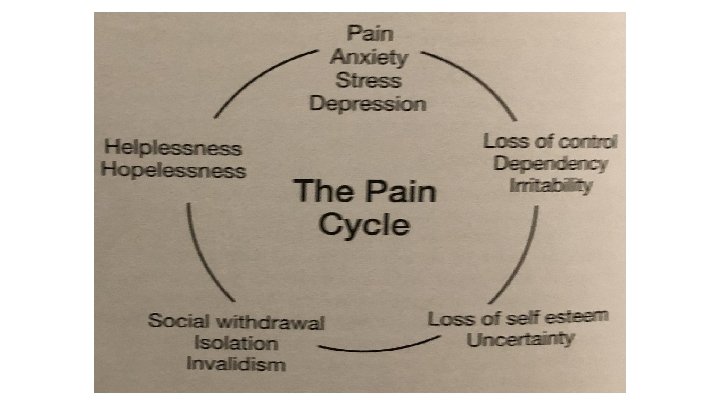

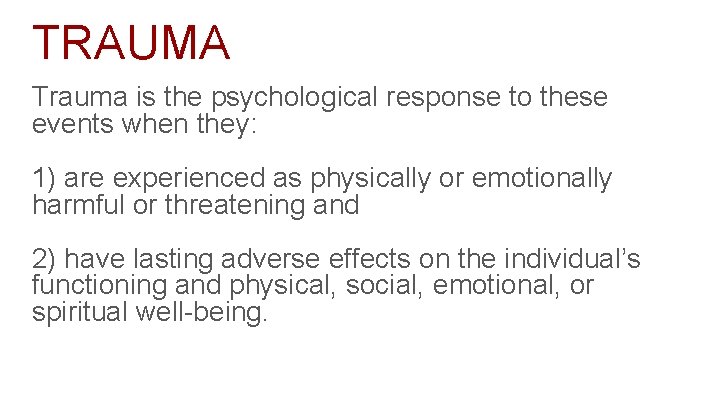

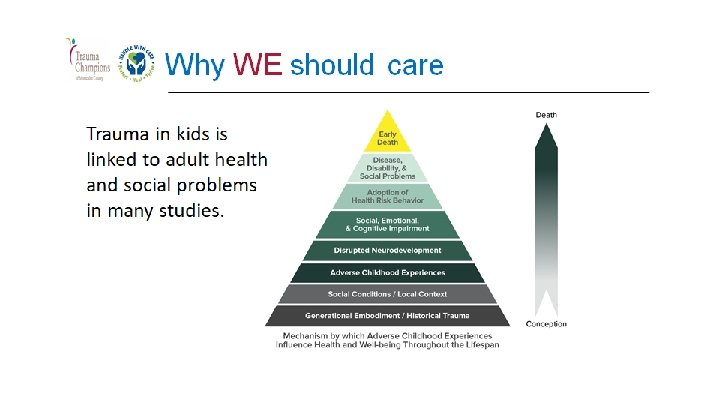

TRAUMA Trauma is the psychological response to these events when they: 1) are experienced as physically or emotionally harmful or threatening and 2) have lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being.

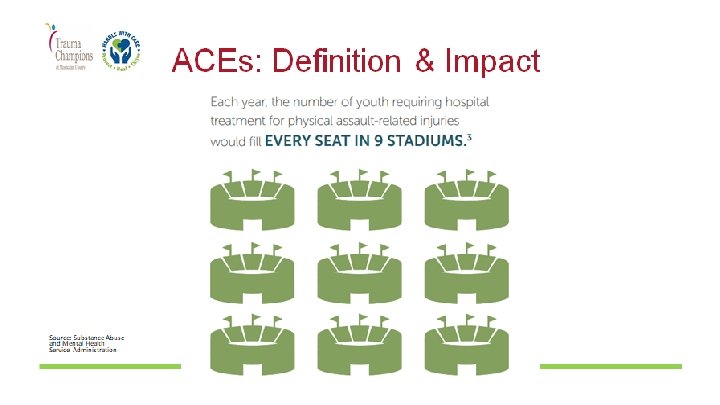

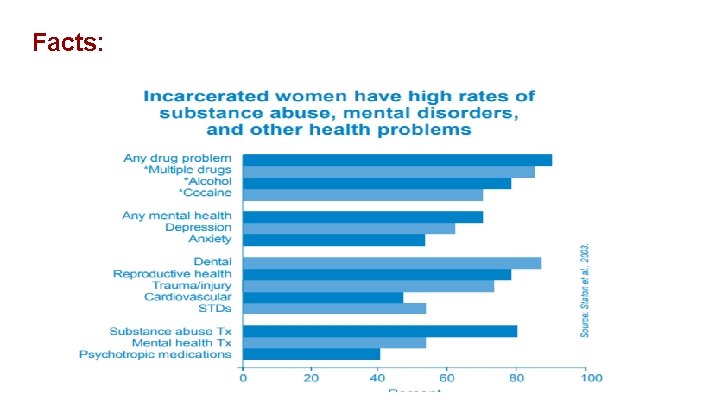

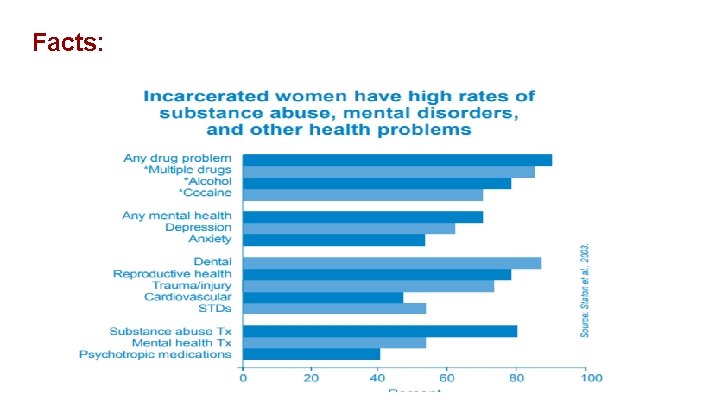

Facts:

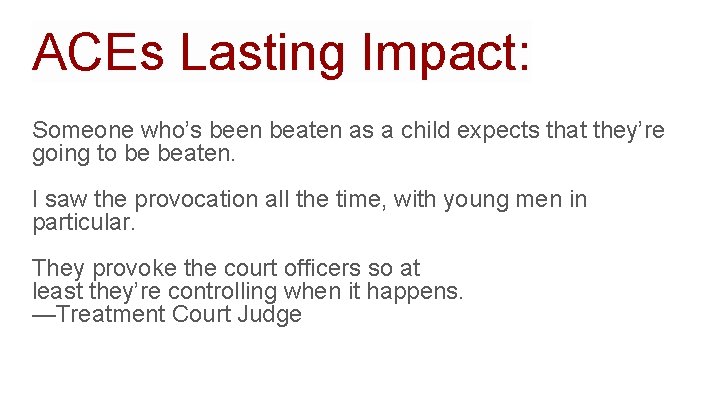

ACEs Lasting Impact: Someone who’s been beaten as a child expects that they’re going to be beaten. I saw the provocation all the time, with young men in particular. They provoke the court officers so at least they’re controlling when it happens. —Treatment Court Judge

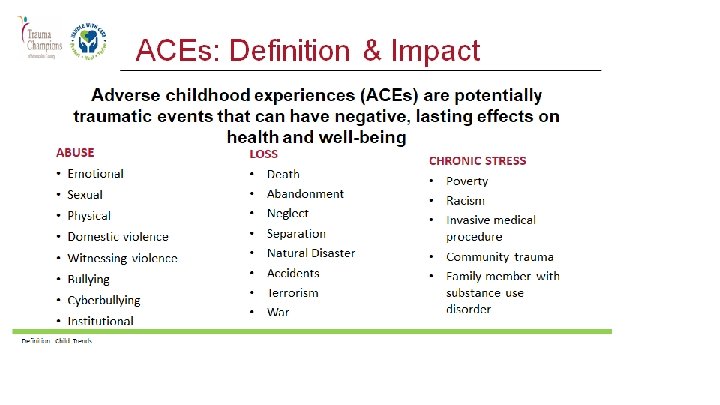

ACEs Trauma Informed GOAL: Fully engage participants by minimizing perceived threats, avoiding re-traumatization, and supporting recovery.

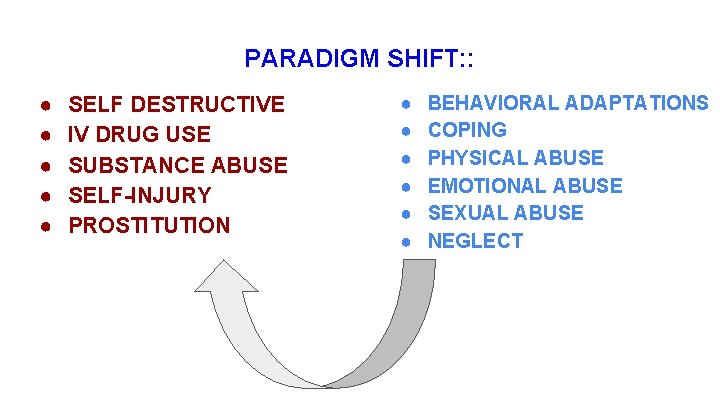

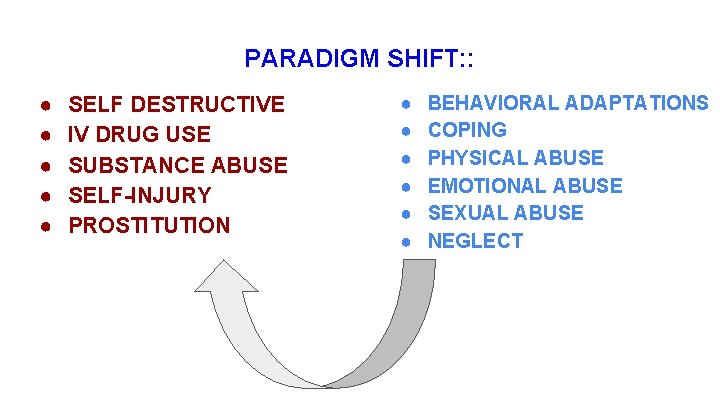

PARADIGM SHIFT: : ● ● ● SELF DESTRUCTIVE IV DRUG USE SUBSTANCE ABUSE SELF-INJURY PROSTITUTION ● ● ● BEHAVIORAL ADAPTATIONS COPING PHYSICAL ABUSE EMOTIONAL ABUSE SEXUAL ABUSE NEGLECT

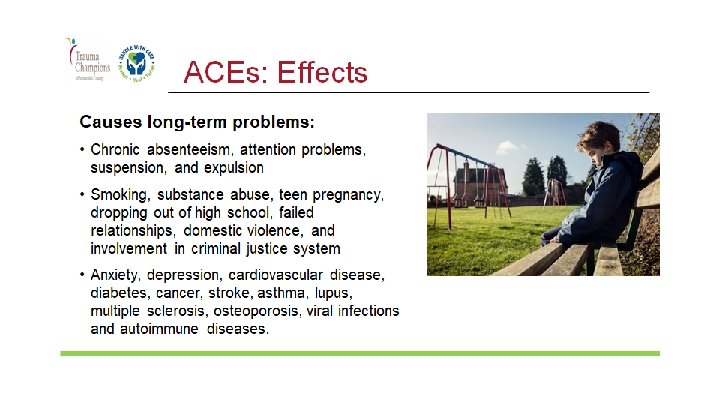

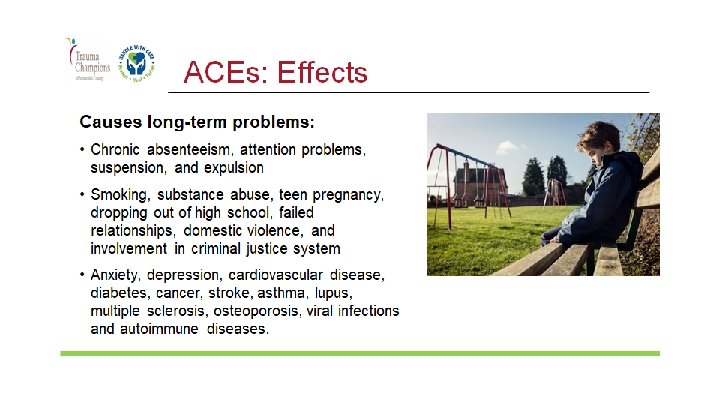

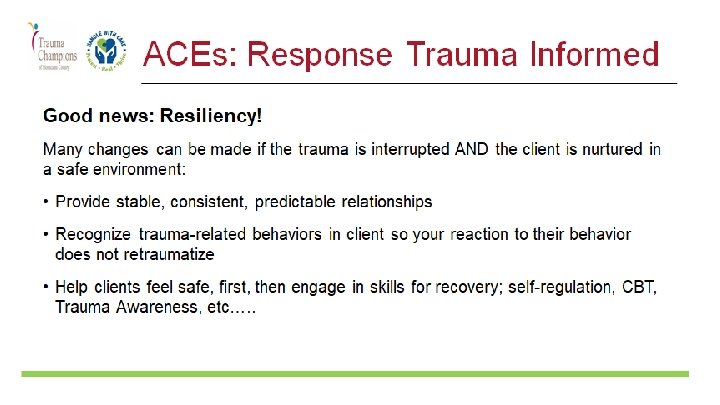

ACE’s Response: Trauma Awareness Mental health crises and suicidality often are rooted in trauma. These crises are compounded when crisis care involves loss of freedom, noisy and crowded environments and/or the use of force. These situations can actually re-traumatize individuals at the worst possible time, leading to worsened symptoms and a genuine reluctance to seek help in the future.

ACE’s Response: Trauma Awareness Many judges have come to recognize that acknowledging and understanding the impact of trauma on court participants may lead to more successful interactions and outcomes Recognizing the impact of past trauma on treatment court participants does not mean that you must be both judge and treatment provider. Rather, trauma awareness is an opportunity to make small adjustments that improve judicial outcomes while minimizing avoidable challenges and conflict during and after hearings.

Trauma-Specific Services & Interventions: Designed to help individuals understand how their past experiences shape their behavior and responses to current events. Trauma-specific services often help individuals develop more effective coping strategies to address the impact of trauma.

Safety Maintaining a predictable schedule of weekly or twice weekly court appearances enhances the effect of treatment on improving the life skills of attendance, promptness, and planning ahead (Peters & Osher, 2004).

Flexibility: No matter which type of court you have, the key to treating participants with co-occurring disorders is flexibility. People with difficulty thinking, concentrating, or controlling emotions are not able to successfully participate in standard therapeutic groups or 12 -step programs (Mueser et al. , 2003).

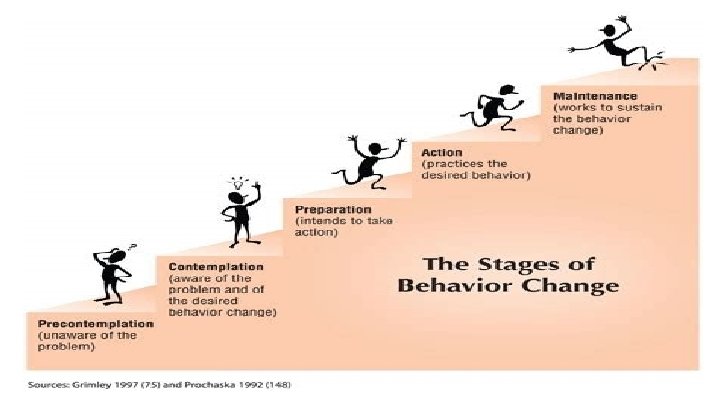

Goal Setting

Individualized ● ● ● Resources Support Time Attendance Timeliness Stability

Individualized Education • Educate people about their challenges, including its biological nature and their increased sensitivity to substances • Teach more effective strategies for coping with symptoms and distress

Individualized Education • Improve social skills and identify alternative social outlets to meet social needs • Help people develop meaningful roles in life, such as student, worker, or parent

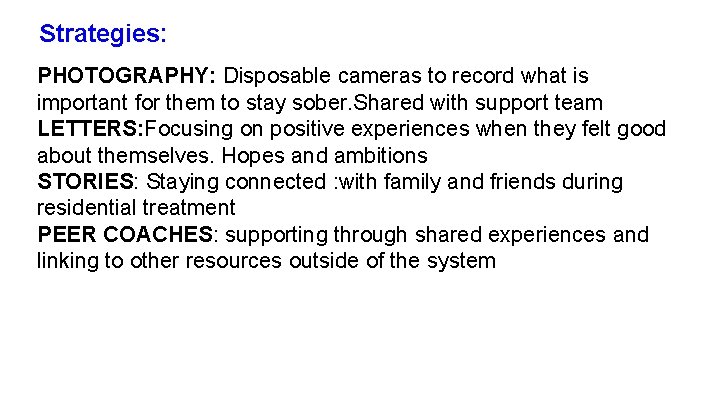

Strategies: PHOTOGRAPHY: Disposable cameras to record what is important for them to stay sober. Shared with support team LETTERS: Focusing on positive experiences when they felt good about themselves. Hopes and ambitions STORIES: Staying connected : with family and friends during residential treatment PEER COACHES: supporting through shared experiences and linking to other resources outside of the system

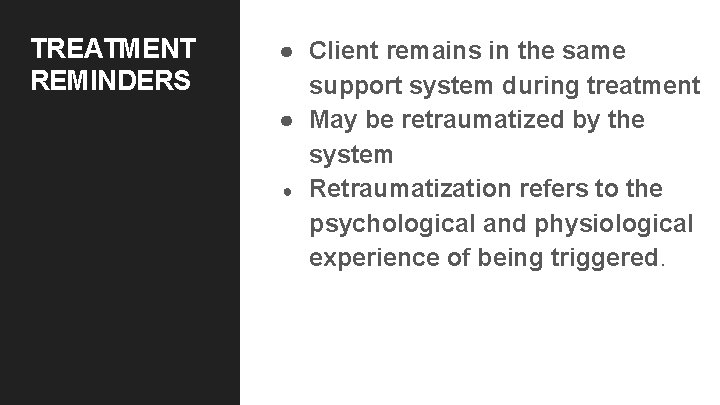

TREATMENT REMINDERS ● Client remains in the same support system during treatment ● May be retraumatized by the system ● Retraumatization refers to the psychological and physiological experience of being triggered.

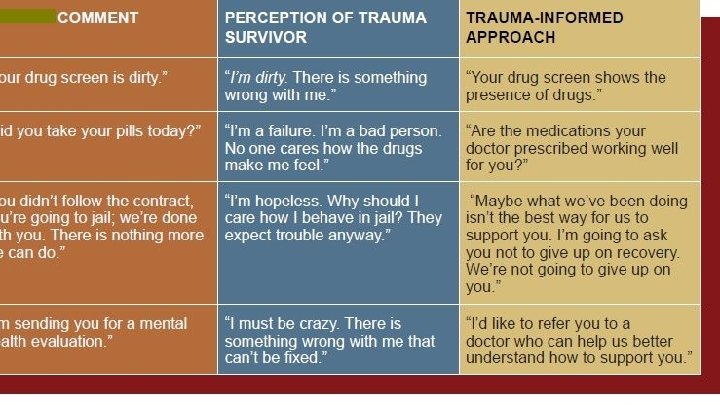

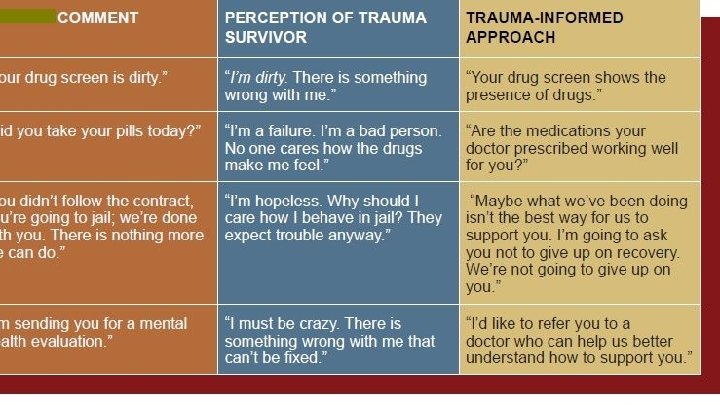

What You Say: Communication Counts Words can be hurtful or potentially healing

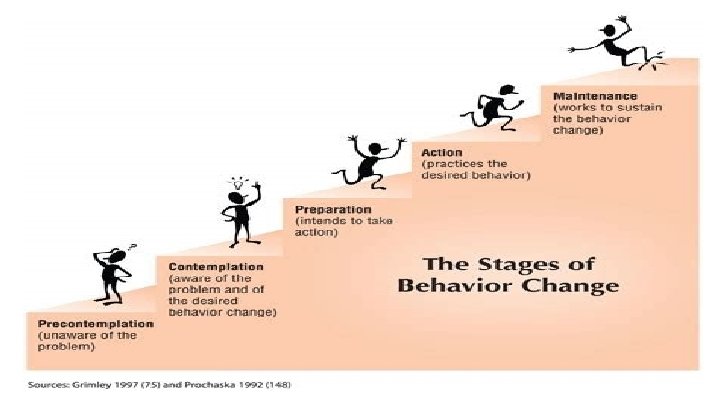

Motivational Interviewing “MI is a collaborative, goal-oriented style of communication with particular attention to the language of change. It is designed to strengthen personal motivation for and commitment to a specific goal by eliciting and exploring the person’s own reasons for change within an atmosphere of acceptance and compassion. ” (Miller & Rollnick, 2013, p. 29

MOTIVATIONAL INTERVIEWING (MI) ● MI is a guiding style of communication, that sits between following (good listening) and directing (giving information and advice). ● MI is designed to empower people to change by drawing out their own meaning, importance and capacity for change. ● MI is based on a respectful and curious way of being with people that facilitates the natural process of change and honors client autonomy.

MI; Success Ambivalence is high Confidence is low Desire is low Importance is low

MI has core skills of OARS, attending to the language of change and the artful exchange of information ● Open questions draw out and explore the person’s experiences, perspectives, and ideas. Evocative questions guide the client to reflect on how change may be meaningful or possible. Information is often offered within a structure of open questions (Elicit-Provide-Elicit) that first explores what the person already knows, then seeks permission to offer what the practitioner knows and then explores the person’s response. ● Affirmation of strengths, efforts, and past successes help to build the person’s hope and confidence in their ability to change. ● Reflections are based on careful listening and trying to understand what the person is saying, by repeating, rephrasing or offering a deeper guess about what the person is trying to communicate. This is a foundational skill of MI and how we express empathy. ● Summarizing ensures shared understanding and reinforces key points made by the client. ● Attending to the language of change identifies what is being said against change (sustain talk) and in favor of change (change talk) and, where appropriate, encouraging a movement away from sustain talk toward change talk.

MI has four fundamental processes. These processes describe the “flow” of the conversation although we may move back and forth among processes as needed ● Engaging: This is the foundation of MI. The goal is to establish a productive working relationship through careful listening to understand accurately reflect the person’s experience and perspective while affirming strengths and supporting autonomy. ● Focusing: In this process an agenda is negotiated that draws on both the client and practitioner expertise to agree on a shared purpose, which gives the clinician permission to move into a directional conversation about change. ● Evoking: In this process the clinician gently explores and helps the person to build their own “why” of change through eliciting the client’s ideas and motivations. Ambivalence is normalized, explored without judgement and, as a result, may be resolved. This process requires skillful attention to the person’s talk about change. ● Planning: Planning explores the “how” of change where the MI practitioner supports the person to consolidate commitment to change and develop a plan based on the person’s own insights and expertise. This process is optional and may not be required, but if it is the timing and readiness of the client for planning is important.

MI is practiced with an underlying spirit or way of being with people: ● Partnership. MI is a collaborative process. The MI practitioner is an expert in helping people change; people are the experts of their own lives. ● Evocation. People have within themselves resources and skills needed for change. MI draws out the person’s priorities, values, and wisdom to explore reasons for change and support success. ● Acceptance. The MI practitioner takes a nonjudgmental stance, seeks to understand the person’s perspectives and experiences, expresses empathy, highlights strengths, and respects a person’s right to make informed choices about changing or not changing. ● Compassion. The MI practitioner actively promotes and prioritizes clients’ welfare and wellbeing in a selfless manner.

ACE’s Response: Trauma Informed It wasn’t until I finally entered a recovery oriented, trauma-informed treatment program, where I felt safe and respected, that I could begin to heal…Someone finally asked me “What happened to you? ” instead of “What’s wrong with you? ” — Tonier Cain, Team Leader, SAMHSA’s National Center for Trauma-Informed Care

RESOURCES: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, SAMHSA’s National Center on Trauma-Informed Care and SAMHSA’s National GAINS Center for Behavioral Health and Justice: Essential Components of Trauma. Informed Judicial Practice. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2013.

RESOURCES cont: http: //www. cdc. gov/ace/ 2 Specifically, participants were asked whether they had experienced one or more of the following events during childhood: emotional, physical, or sexual abuse; domestic violence; substance abuse, mental illness, or incarceration of a household member; and parental separation. You can access the current version of the ACE study questionnaire at http: //acestudy. org/ace_score.

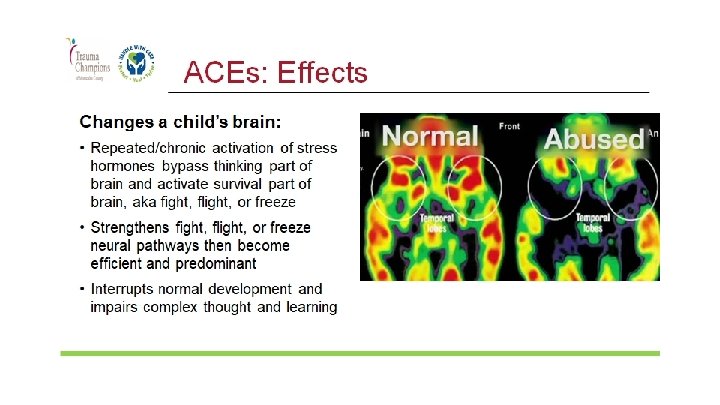

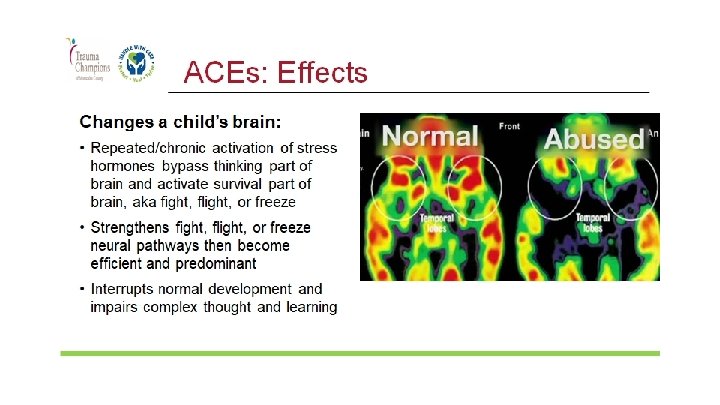

RESOURCES cont: Administration for Children and Families. (2009). Understanding the effects of maltreatment on brain development. Available online at https: //www. childwelfare. gov/pubs/issue_ briefs/brain_development. pdf.