Trauma informed practice Nancy Poole BC Centre of

Trauma informed practice Nancy Poole, BC Centre of Excellence for Women’s Health

1. Agenda 2. 3. 4. 5. Foundations TIP principles and key practices TIP in action in various settings, with specific groups TIP at the organisational/system level Reflection

Will draw on: � System change work with a BC MHSU system towards trauma informed practice, and the ideas of contributors to the book Becoming Trauma Informed �Current work on trauma informed practice for child and youth mental health, child protection, youth justice and children with special needs services �Thinking of many contributors to the field from neurobiology, psychology, systems thinking, indigenous studies, violence against women. . .

"We found that the big issues that kept coming up – addictions, FASD, domestic violence and residential schools – were all related to trauma. “ Interview excerpt from an environmental scan of traumainformed approaches in Canada, 2010 -2011

A problem without a home � Intervention is not a specialist problem but a broad social responsibility that should be shared by many public and private sectors Carroll & Miller, 2006 Rethinking substance abuse: what the science shows, and what we should do about it.

FOUNDATIONS

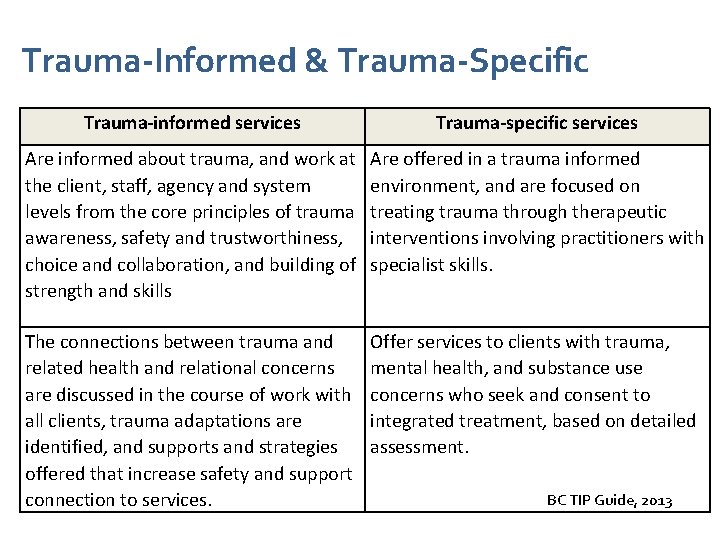

Trauma-Informed & Trauma-Specific Trauma-informed services Trauma-specific services Are informed about trauma, and work at the client, staff, agency and system levels from the core principles of trauma awareness, safety and trustworthiness, choice and collaboration, and building of strength and skills Are offered in a trauma informed environment, and are focused on treating trauma through therapeutic interventions involving practitioners with specialist skills. The connections between trauma and related health and relational concerns are discussed in the course of work with all clients, trauma adaptations are identified, and supports and strategies offered that increase safety and support connection to services. Offer services to clients with trauma, mental health, and substance use concerns who seek and consent to integrated treatment, based on detailed assessment. BC TIP Guide, 2013

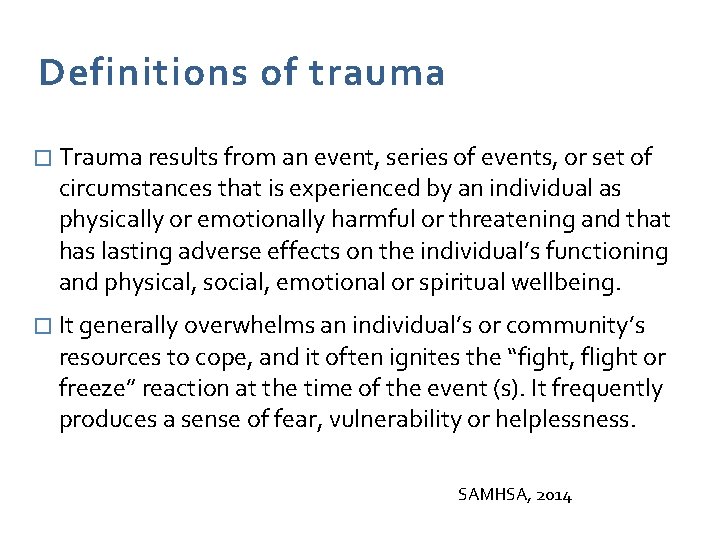

Definitions of trauma � Trauma results from an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and physical, social, emotional or spiritual wellbeing. � It generally overwhelms an individual’s or community’s resources to cope, and it often ignites the “fight, flight or freeze” reaction at the time of the event (s). It frequently produces a sense of fear, vulnerability or helplessness. SAMHSA, 2014

Definitions of trauma � Interpersonal trauma will be defined as experiences involving disruption in trusted relationships as the result of violence, abuse, war or other forms of political oppression, or forced uprooting and dislocation from one’s family, community, heritage, and/or culture. (Berman, Mason et al. , 2010)

Trauma and PTSD � The terms violence, trauma, abuse, and post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) often are used interchangeably. One way to clarify these terms is to think of trauma as a response to violence or some other overwhelmingly negative experience (e. g. , abuse). � Trauma is both an event and a particular response to an event. � PTSD is one type of disorder that can result from trauma. (Covington, 2003)

Trauma examples � Caused naturally – wildfire, flood, tornado, tree falling � Caused by people through accidents and technological catastrophes – train derailment, oil spill � Caused by people via intentional acts - sexual assault, warfare, domestic violence, mob violence, home invasion, bank robbery, school shooting, terrorism, genocide. . � Can be individual, group, community or mass trauma � Can be interpersonal, developmental, political, or system-oriented (retraumatization) SAMHSA 2014

Historical trauma • Recognition of trauma caused by colonization & racism – Historical trauma (Indian Residential Schools, Indian Hospitals, 60’s scoop) – Intergenerational trauma – Efforts to redress trauma related to residential schools Maria Yellow Horse Brave Heart (1998), Michael Yellow Bird (2013), Deborah Chansonneuve (2007)

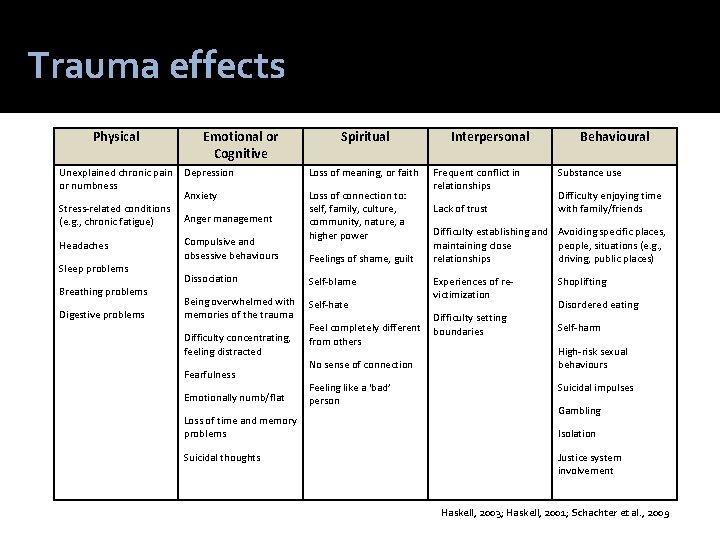

Trauma effects Physical Unexplained chronic pain or numbness Stress-related conditions (e. g. , chronic fatigue) Headaches Sleep problems Breathing problems Digestive problems Emotional or Cognitive Spiritual Depression Loss of meaning, or faith Anxiety Loss of connection to: self, family, culture, community, nature, a higher power Anger management Compulsive and obsessive behaviours Feelings of shame, guilt Dissociation Self-blame Being overwhelmed with memories of the trauma Self-hate Difficulty concentrating, feeling distracted Fearfulness Emotionally numb/flat Loss of time and memory problems Suicidal thoughts Feel completely different from others No sense of connection Feeling like a ‘bad’ person Interpersonal Frequent conflict in relationships Lack of trust Behavioural Substance use Difficulty enjoying time with family/friends Difficulty establishing and Avoiding specific places, maintaining close people, situations (e. g. , relationships driving, public places) Experiences of revictimization Difficulty setting boundaries Shoplifting Disordered eating Self-harm High-risk sexual behaviours Suicidal impulses Gambling Isolation Justice system involvement Haskell, 2003; Haskell, 2001; Schachter et al. , 2009

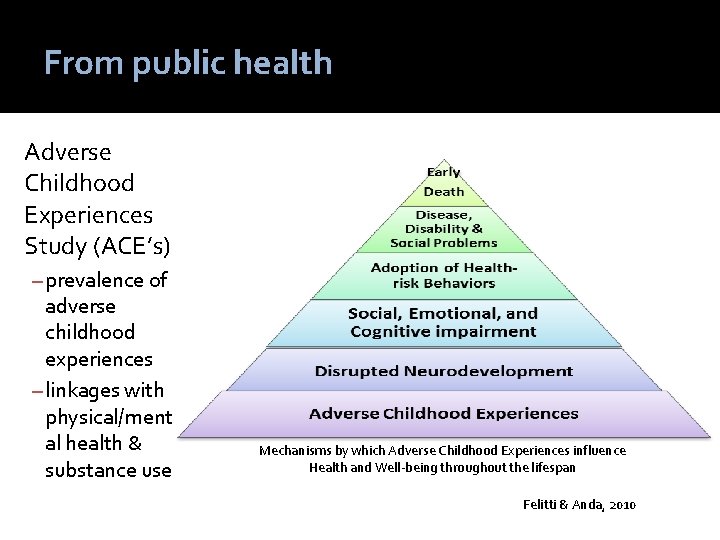

From public health Adverse Childhood Experiences Study (ACE’s) – prevalence of adverse childhood experiences – linkages with physical/ment al health & substance use Mechanisms by which Adverse Childhood Experiences influence Health and Well-being throughout the lifespan Felitti & Anda, 2010

From neurobiology Neurobiological explanations and interventions

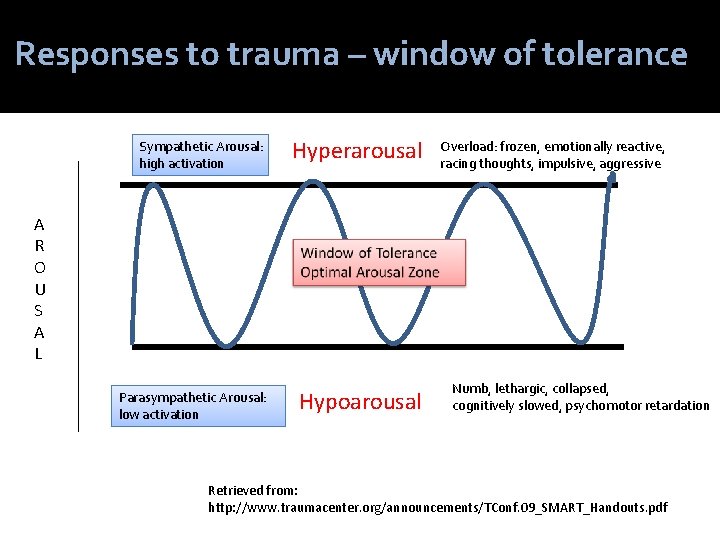

Responses to trauma – window of tolerance Sympathetic Arousal: high activation Hyperarousal Overload: frozen, emotionally reactive, racing thoughts, impulsive, aggressive A R O U S A L Parasympathetic Arousal: low activation Hypoarousal Numb, lethargic, collapsed, cognitively slowed, psychomotor retardation Retrieved from: http: //www. traumacenter. org/announcements/TConf. 09_SMART_Handouts. pdf

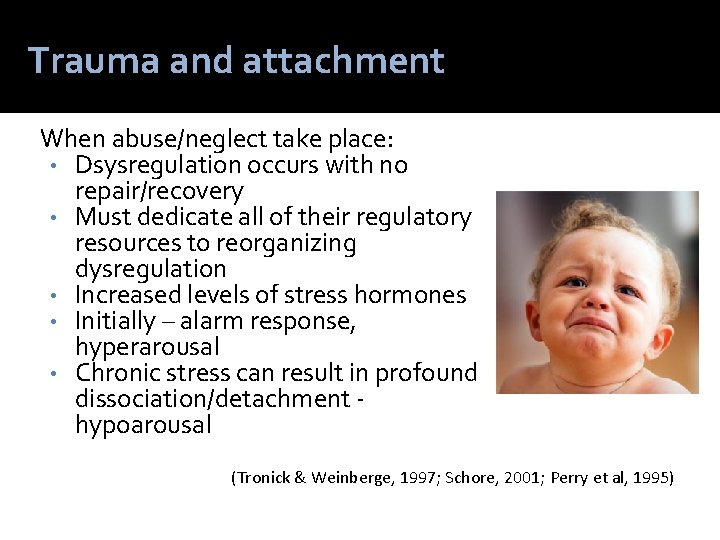

Trauma and attachment When abuse/neglect take place: • Dsysregulation occurs with no repair/recovery • Must dedicate all of their regulatory resources to reorganizing dysregulation • Increased levels of stress hormones • Initially – alarm response, hyperarousal • Chronic stress can result in profound dissociation/detachment hypoarousal (Tronick & Weinberge, 1997; Schore, 2001; Perry et al, 1995)

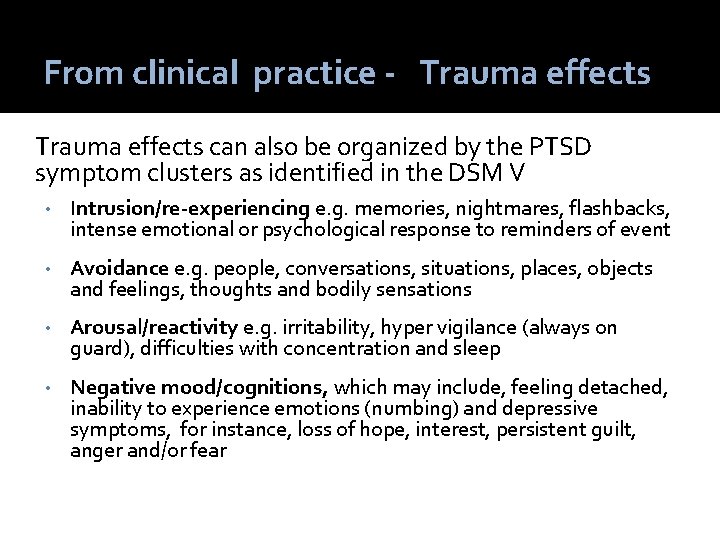

From clinical practice - Trauma effects can also be organized by the PTSD symptom clusters as identified in the DSM V • Intrusion/re-experiencing e. g. memories, nightmares, flashbacks, intense emotional or psychological response to reminders of event • Avoidance e. g. people, conversations, situations, places, objects and feelings, thoughts and bodily sensations • Arousal/reactivity e. g. irritability, hyper vigilance (always on guard), difficulties with concentration and sleep • Negative mood/cognitions, which may include, feeling detached, inability to experience emotions (numbing) and depressive symptoms, for instance, loss of hope, interest, persistent guilt, anger and/or fear

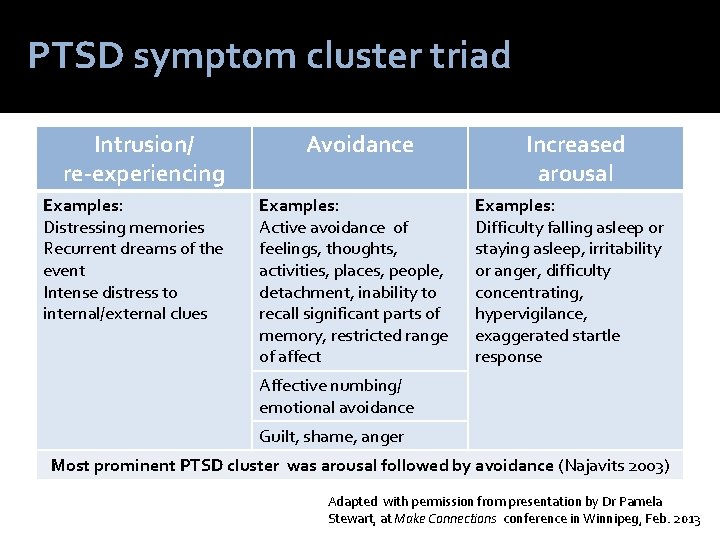

PTSD symptom cluster triad Intrusion/ re-experiencing Examples: Distressing memories Recurrent dreams of the event Intense distress to internal/external clues Avoidance Examples: Active avoidance of feelings, thoughts, activities, places, people, detachment, inability to recall significant parts of memory, restricted range of affect Increased arousal Examples: Difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep, irritability or anger, difficulty concentrating, hypervigilance, exaggerated startle response Affective numbing/ emotional avoidance Guilt, shame, anger Most prominent PTSD cluster was arousal followed by avoidance (Najavits 2003) Adapted with permission from presentation by Dr Pamela Stewart, at Make Connections conference in Winnipeg, Feb. 2013

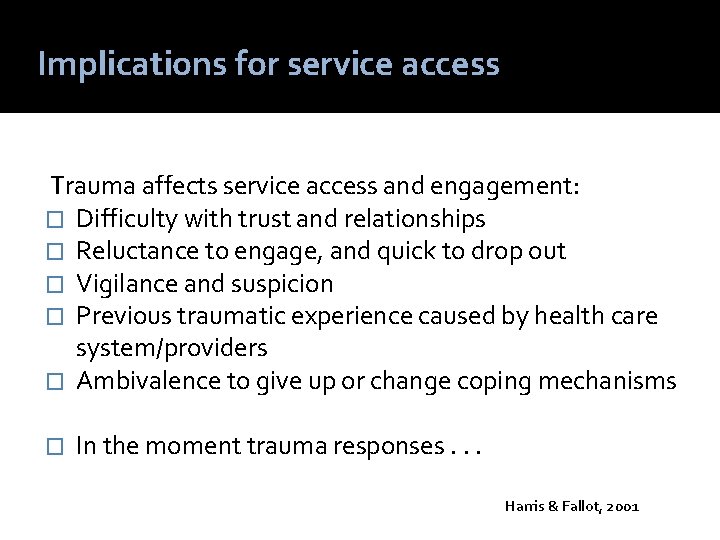

Implications for service access Trauma affects service access and engagement: � Difficulty with trust and relationships � Reluctance to engage, and quick to drop out � Vigilance and suspicion � Previous traumatic experience caused by health care system/providers � Ambivalence to give up or change coping mechanisms � In the moment trauma responses. . . Harris & Fallot, 2001

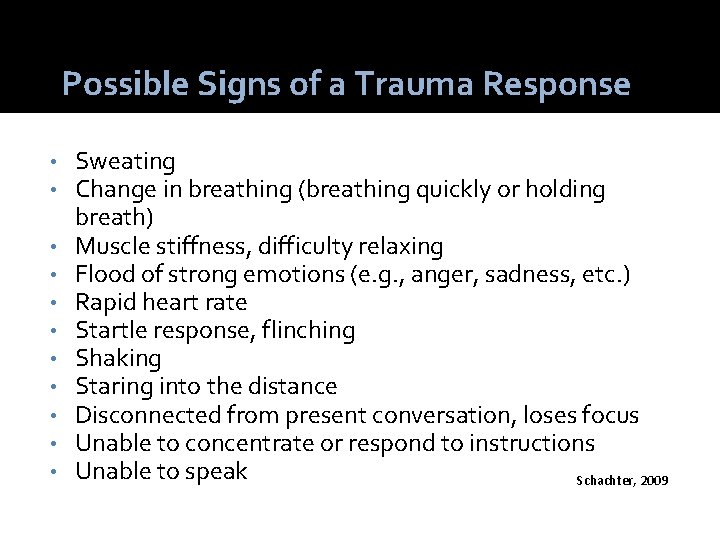

Possible Signs of a Trauma Response • • • Sweating Change in breathing (breathing quickly or holding breath) Muscle stiffness, difficulty relaxing Flood of strong emotions (e. g. , anger, sadness, etc. ) Rapid heart rate Startle response, flinching Shaking Staring into the distance Disconnected from present conversation, loses focus Unable to concentrate or respond to instructions Unable to speak Schachter, 2009

Potential for “misdiagnosis” � Without applying a trauma lens, coping mechanisms such as selfharming may be given diagnoses such as bipolar disorder, and treated exclusively with drugs and behaviour management. � Borderline Personality Disorder is a diagnosis that can be inaccurately applied, to those who have experienced trauma. � People with complex PTSD do not have symptoms that constitute separate, “dual” or comorbid diagnoses, but the complex somatic, cognitive, affective, and behavioral effects of trauma. The lens of complex trauma can provide an empirically based, conceptually coherent view of symptoms as a basis for effective treatment planning. Sources: van der Kolk( 2006) Haskell, L. (2012).

PRINCIPLES

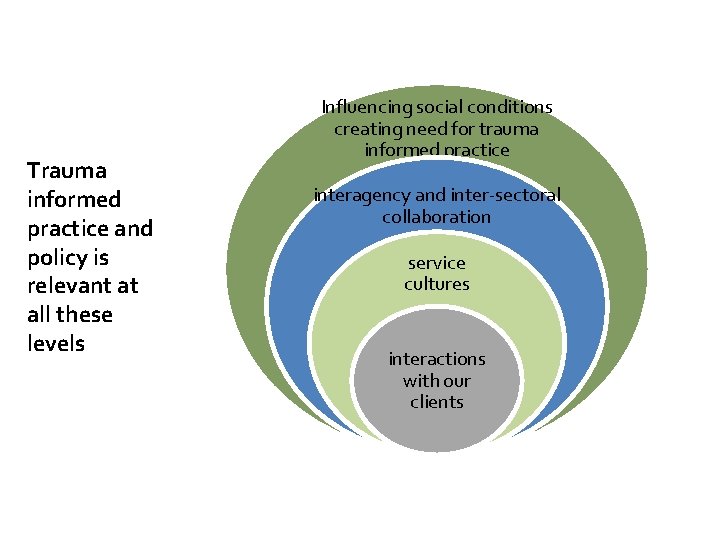

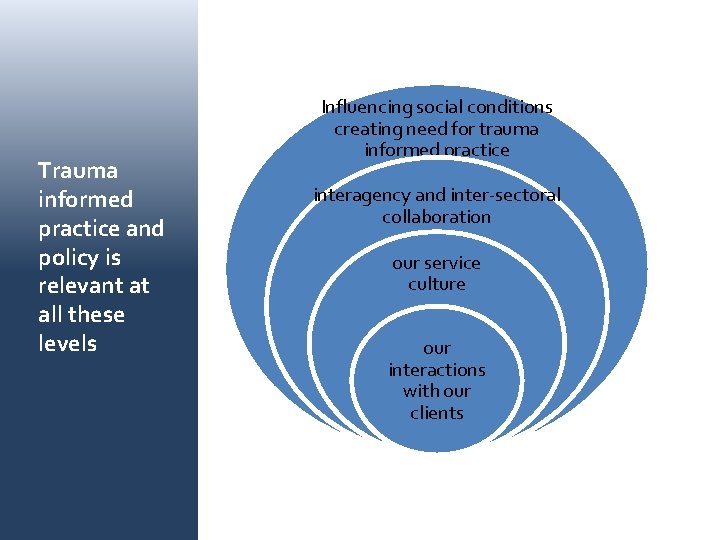

Trauma informed practice and policy is relevant at all these levels Influencing social conditions creating need for trauma informed practice interagency and inter-sectoral collaboration service cultures interactions with our clients

All services taking a trauma-informed approach begin with building awareness among staff and clients of: The high prevalence of trauma How the impact of trauma can be central to one’s development The wide range of adaptations people make to cope and survive The relationship of trauma with substance use, physical health and mental health concerns. This knowledge is the foundation of an organizational culture of trauma-informed care 4 Key Principles 1. Trauma Awareness

Trauma Survivors: Likely have experienced boundary violations and abuse of power Need to feel physically and emotionally safe May currently be in unsafe relationships Safety and trustworthiness are established through: Welcoming intake procedures Adapting the physical space Providing clear information and predictable expectations about programming Ensuring informed consent Creating safety plans 4 Key Principles 2. Emphasis on safety and trustworthiness

Service Providers: The safety and health/wellness needs of service providers are also considered within a trauma-informed service approach. Key component of service provider safety and wellness: Education and support related to vicarious or secondary trauma. 4 Key Principles 2. Emphasis on safety and trustworthiness

Trauma-informed services create safe environments that foster a client’s sense of efficacy, selfdetermination, dignity, and personal control. Service providers are encouraged to: Communicate openly Allow the expression of feelings without fear of judgment Provide choices as to treatment and support preferences Work collaboratively 4 Key Principles 3. Opportunity for choice collaboration and connection

Service providers: Help clients identify their strengths Further/develop resiliency and coping skills Teach and model skills for recognizing triggers, calming, centering and staying present Support an organizational culture of ‘emotional intelligence’ and ‘social learning’ Maintain competency-based skills, knowledge, and values that are trauma informed 4 Key Principles 4. Strengths based and skill building

TIP Application: Trauma awareness � Acknowledge common connections between substance use and trauma � Recognize range of responses people can have � Recognize that because of trauma responses, developing trusting relationships can be difficult � Disclosure of trauma is not required � Recognize when someone is triggered or experiencing the effects of trauma & support BC TIP Guide, 2013 Gender Matters, 2013

TIP can be seen how we view clients who experience difficulty accessing services Shift from: “What is wrong with her” to “What happened to her” Change in language away from: • Controlling • Manipulative • Uncooperative • Untreatable • Masochistic • Attention seeking • Drug seeking • Bad mother • Not believable, etc. (Williams & Paul, 2008)

TIP can be seen in flexible intake practices Trauma informed intake practices - TIP can be seen in flexible intake and assessment processes that: Create safety (including cultural safety) Engage – establish a relationship Do not “press for compliance. ” Screen for present concerns Normalize client experience(s) Set boundaries Identify symptoms 2011 focus groups of BC addictions and mental providers

TIP in early interactions All staff collaborate with clients to: � Provide clear, practical information at initial contacts about what to expect, choices for being contacted and rationale for processes � Provide opportunities for questions � Respond to people who arrive in distress • • T-I Organizational Assessment for programs serving families experiencing homelessness, Guarino et al 2003 Creating Cultures of Trauma-informed Care, Fallot 2009 Trauma Matters, 2013 (Jean Tweed Centre) The Trauma Toolkit 2 nd Edition 2013 (Klinic)

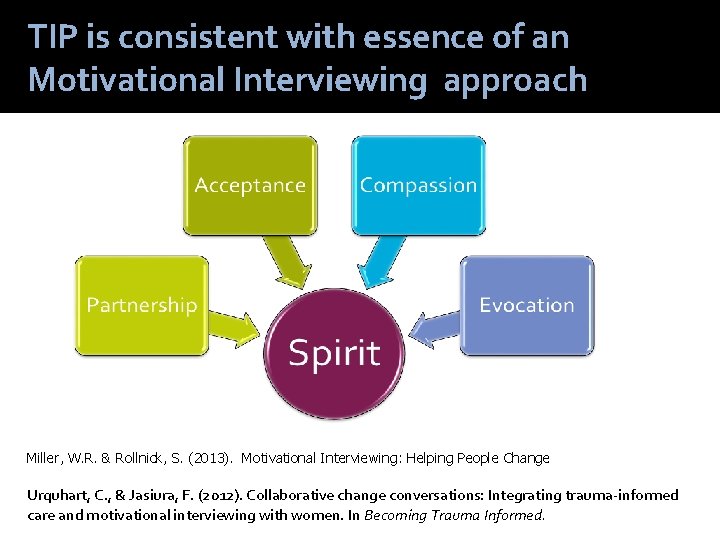

TIP is consistent with essence of an Motivational Interviewing approach Miller, W. R. & Rollnick, S. (2013). Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change Urquhart, C. , & Jasiura, F. (2012). Collaborative change conversations: Integrating trauma-informed care and motivational interviewing with women. In Becoming Trauma Informed.

TIP application: Physical environment Consider: � Signage with welcoming messages, avoiding “do not” messages � Waiting areas - comfortable and inviting � Lighting in outside spaces � Accessibility and safety of washrooms � In counseling rooms – choice about whether door is open or closed Fallot & Harris (2009), Jean Tweed Centre (2013), and BC service learning

TIP as client involvement in articulating their rights The CAMH Bill of Clients Rights and the client-run Empowerment Council exemplify the need for providers of trauma informed care to lead by example. . . In the simplest terms, rights are about not imposing one’s will on another person. Trauma survivors cannot learn the essential ability of defending their own boundaries if people who are supposed to care for them, trample them. Client rights are about being treated as full citizens in the mental health and addictions treatment systems. Creating an environment in which these rights flourish is the first step to making a space where real healing can happen Jennifer Chambers (2012) What do client rights have to do with trauma-informed care? in Becoming Trauma-Informed. Toronto: CAMH

SETTINGS

TIP in primary care settings – referring into MHSU services This handbook presents information that will help health care practitioners practise in a manner that is sensitive to the needs of adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse and other types of interpersonal violence. It is intended for health care practitioners and students of all health disciplines who have no specialized training in mental health, psychiatry, or psychotherapy and have limited experience working with adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse. Schachter, C. A. Stalker, et al. (2008). Handbook on Sensitive Practice for Health Care Practitioners: Lessons from Adult Survivors of Childhood Sexual Abuse. Ottawa, ON, National Clearinghouse on Family Violence.

TIP in homeless shelters Trauma-informed programming was implemented in Boston metropolitan homeless shelters Evaluation results indicated positive outcomes: high levels of support for the organizational shift to trauma-informed programming, increased staff confidence, fewer resident conflicts, better relationships among staff and residents, and fewer resident terminations Guarino, K. , Soares, P. , Konnath, K. , Clervil, R. , and Bassuk, E. (2009). Trauma. Informed Organizational Toolkit. Hopper, E. K. , Bassuk, E. L. , & Olivet, J. (2010). Shelter from the storm: Trauma-informed care in homelessness services settings. The Open Health Services and Policy Journal, 3, 80 -100.

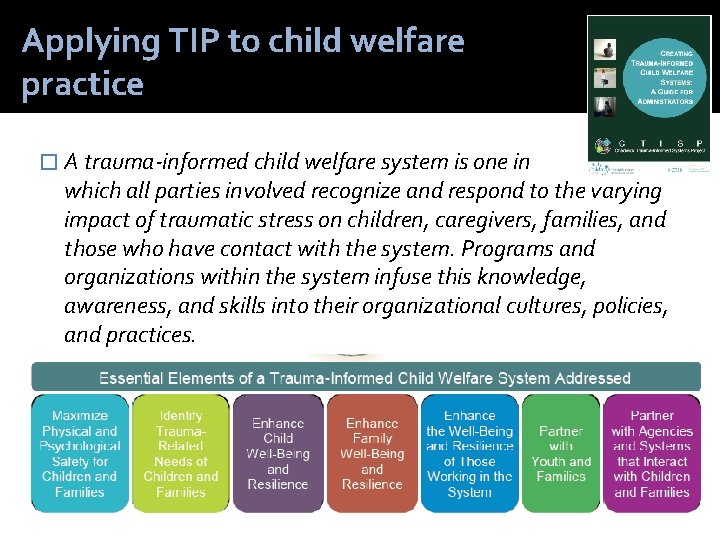

Applying TIP to child welfare practice � A trauma-informed child welfare system is one in which all parties involved recognize and respond to the varying impact of traumatic stress on children, caregivers, families, and those who have contact with the system. Programs and organizations within the system infuse this knowledge, awareness, and skills into their organizational cultures, policies, and practices.

TIP in interventions on specific substances -Trauma informed tobacco interventions

TIP as prevention of seclusion and restraint

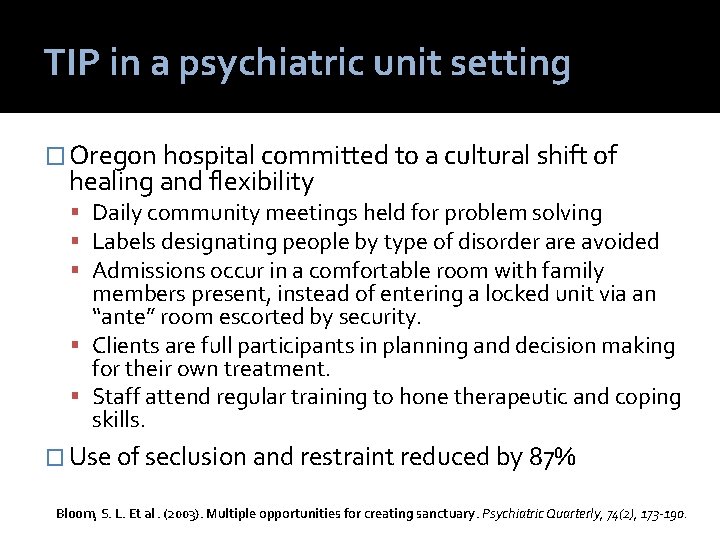

TIP in a psychiatric unit setting � Oregon hospital committed to a cultural shift of healing and flexibility Daily community meetings held for problem solving Labels designating people by type of disorder are avoided Admissions occur in a comfortable room with family members present, instead of entering a locked unit via an “ante” room escorted by security. Clients are full participants in planning and decision making for their own treatment. Staff attend regular training to hone therapeutic and coping skills. � Use of seclusion and restraint reduced by 87% Bloom, S. L. Et al. (2003). Multiple opportunities for creating sanctuary. Psychiatric Quarterly, 74(2), 173 -190.

TIP in youth residential treatment � Systematic debriefing following restraint & seclusion – prevention focus (safety) � Policies & procedures to ensure awareness of program expectations, staff roles & boundaries i. e. avoid favoritism (trust) � Choice of staff to provide support with coping during escalation (choice & control) Hummer, et al (2010). Innovations in implementation of trauma-informed care practices in youth residential treatment: a curriculum for organizational change.

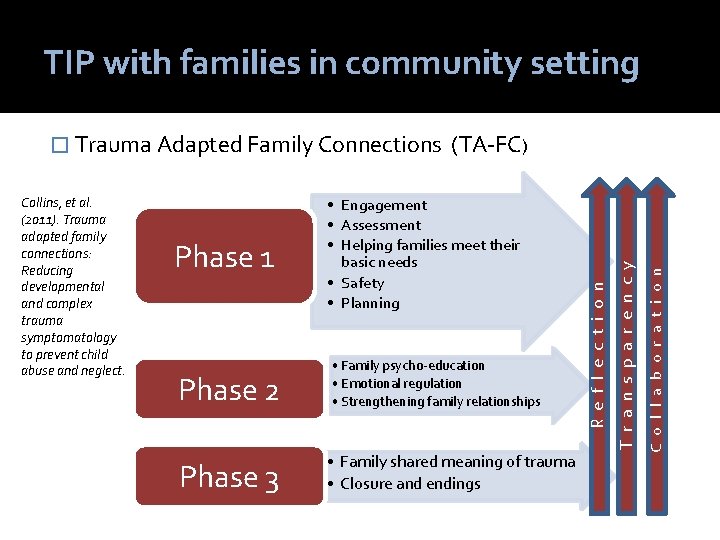

TIP with families in community setting Phase 2 Phase 3 • Family psycho-education • Emotional regulation • Strengthening family relationships • Family shared meaning of trauma • Closure and endings C o l l a b o r a t i o n Phase 1 • Engagement • Assessment • Helping families meet their basic needs • Safety • Planning T r a n s p a r e n c y Collins, et al. (2011). Trauma adapted family connections: Reducing developmental and complex trauma symptomatology to prevent child abuse and neglect. (TA-FC) R e f l e c t i o n � Trauma Adapted Family Connections

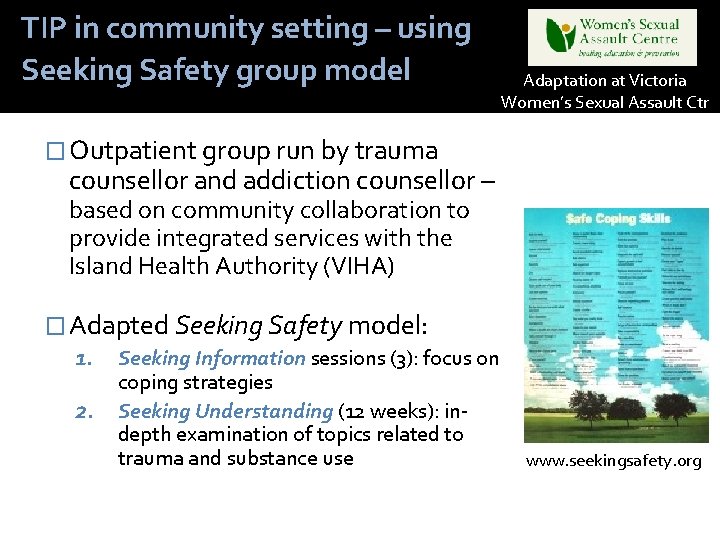

TIP in community setting – using Seeking Safety group model Adaptation at Victoria Women’s Sexual Assault Ctr � Outpatient group run by trauma counsellor and addiction counsellor – based on community collaboration to provide integrated services with the Island Health Authority (VIHA) � Adapted Seeking Safety model: 1. Seeking Information sessions (3): focus on coping strategies 2. Seeking Understanding (12 weeks): indepth examination of topics related to trauma and substance use www. seekingsafety. org

Conclusions from the Women and Co-occurring Disorders and Violence Study � Women in integrated care experience significantly more reductions in symptoms of mental illness, alcohol and drug use compared to women in traditional services � Service costs remain the same Domino, M. , Morrissey, J. P. , Nadlicki-Patterson, T. , & Chung, S. (2005). Service costs for women with co-occurring disorders and trauma. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 28(2), 135 -143.

GENDER AND CULTURE

Trauma informed, gender responsive work with men Safety and trustworthiness - Empathize with the ‘disconnection dilemma’, i. e. the conflict between their identity as men and their experience of powerlessness � Skill building - A key trauma recovery skill for men is developing a broader range of options for expressing emotions � Collaboration and connection – Men who have been sensitized to abuse of power in relationships may need to hear offers of collaboration repeatedly. � Strengths based – acknowledgement of relational strengths may be ‘water in the desert’ for male survivors � Fallot, R. , & Bebout, R. (2012). Acknowledging and Embracing "the Boy inside the Man": Trauma-informed Work with Men. In N. Poole & L. Greaves (Eds. ), Becoming Trauma Informed (pp. 165174). Toronto, ON: Centre for Addiction and Mental Health

Crime & Justice Institute. (January 26, 2006). Interventions for High-Risk Youth: Applying Evidence-Based Theory and Practice to the Work of Roca (pp. 26). Boston, MA: Crime & Justice Institute. Roca’s core strategies include outreach and street work, transformational relationships, peacemaking circles, and engaged institutions. Rich, J. A. , Corbin, T. J. , Bloom, S. L. , Rich, L. J. , Evans, S. , & Wilson, A. S. (2009). Healing the Hurt: Trauma-Informed Approaches to the Health of Boys and Young Men of Color (pp. 86). Drexel University: The Center for Nonviolence and Social Justice.

Strengths and Opportunities: Port of Entry – TIP provides a safe space with which to hold challenging conversations about colonization, oppression, intergenerational trauma, racism, etc. • Informs general services about Indigenous-specific history in Canada. • Potential to broaden perspectives and strengthen relationships. TIP provides a common language and is driven by principles that are aligned with Indigenous values and beliefs – gaining huge momentum in Aboriginal communities. Source: Kat Hinter – Aboriginal Knowledge Exchange Lead, IH BC

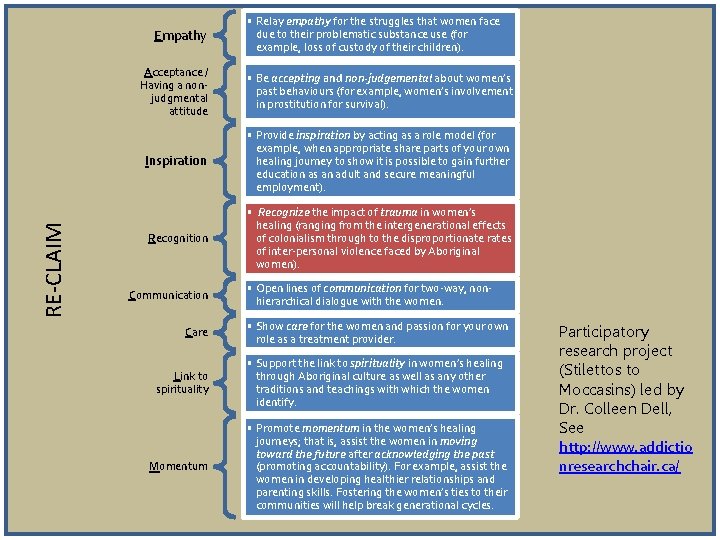

Trauma informed practice within treatment for Indigenous women Collaborative research project (2005) led by Dr. Colleen Dell, between the National Native Addictions Partnership Foundation, the Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse and the University of Saskatchewan. http: //www. addictionresearchchair. ca/creatingknowledge/national/aboriginal-women-drug-users-in-conflict-withthe-law/present-our-findings-by-delivering-a-workshop/

RE-CLAIM Empathy • Relay empathy for the struggles that women face due to their problematic substance use (for example, loss of custody of their children). Acceptance / Having a nonjudgmental attitude • Be accepting and non-judgemental about women’s past behaviours (for example, women’s involvement in prostitution for survival). Inspiration • Provide inspiration by acting as a role model (for example, when appropriate share parts of your own healing journey to show it is possible to gain further education as an adult and secure meaningful employment). Recognition • Recognize the impact of trauma in women’s healing (ranging from the intergenerational effects of colonialism through to the disproportionate rates of inter-personal violence faced by Aboriginal women). Communication Care • Open lines of communication for two-way, nonhierarchical dialogue with the women. • Show care for the women and passion for your own role as a treatment provider. Link to spirituality • Support the link to spirituality in women’s healing through Aboriginal culture as well as any other traditions and teachings with which the women identify. Momentum • Promote momentum in the women’s healing journeys; that is, assist the women in moving toward the future after acknowledging the past (promoting accountability). For example, assist the women in developing healthier relationships and parenting skills. Fostering the women’s ties to their communities will help break generational cycles. Participatory research project (Stilettos to Moccasins) led by Dr. Colleen Dell, See http: //www. addictio nresearchchair. ca/

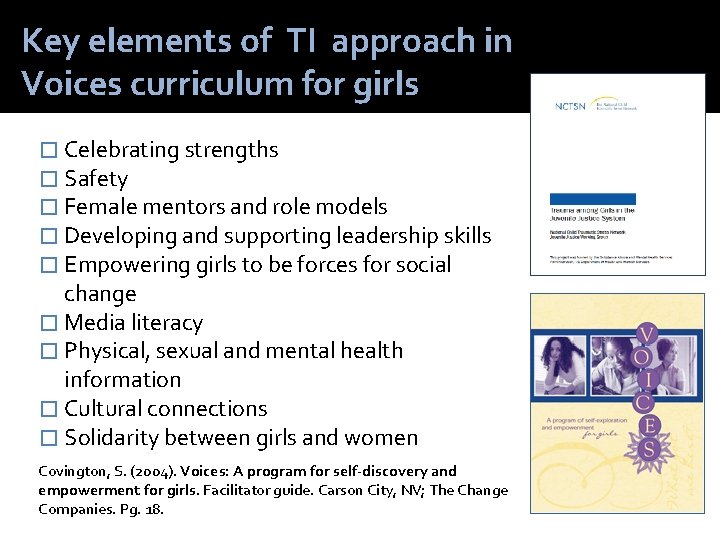

Key elements of TI approach in Voices curriculum for girls � Celebrating strengths � Safety � Female mentors and role models � Developing and supporting leadership skills � Empowering girls to be forces for social change � Media literacy � Physical, sexual and mental health information � Cultural connections � Solidarity between girls and women Covington, S. (2004). Voices: A program for self-discovery and empowerment for girls. Facilitator guide. Carson City, NV; The Change Companies. Pg. 18.

TIP AT THE ORGANIZATIONAL LEVEL

Trauma informed practice and policy is relevant at all these levels Influencing social conditions creating need for trauma informed practice interagency and inter-sectoral collaboration our service culture our interactions with our clients

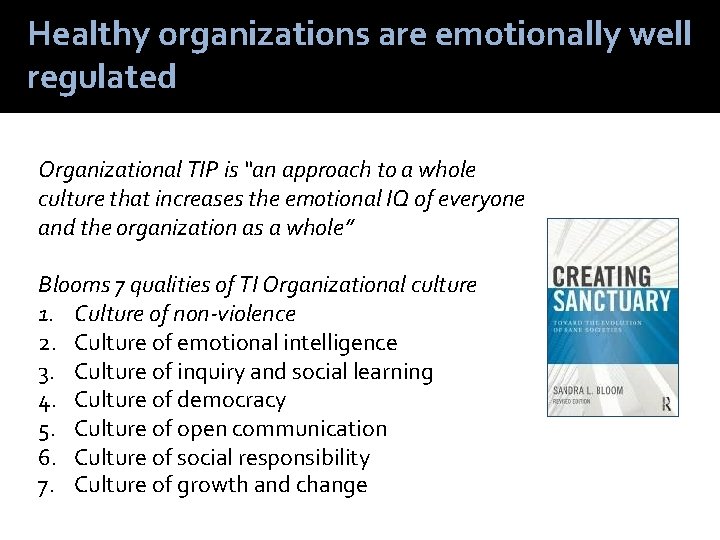

Healthy organizations are emotionally well regulated Organizational TIP is “an approach to a whole culture that increases the emotional IQ of everyone and the organization as a whole” Blooms 7 qualities of TI Organizational culture 1. Culture of non-violence 2. Culture of emotional intelligence 3. Culture of inquiry and social learning 4. Culture of democracy 5. Culture of open communication 6. Culture of social responsibility 7. Culture of growth and change

Walk through assessment tools and checklists Service Policies Section Are policies regarding confidentiality clear and do they provide adequate protection for the privacy of consumers? 2. Does the program avoid involuntary or potentially coercive aspects of treatment, whenever possible? 3. Has the program developed a de-escalation policy that minimizes the possibility of re-traumatization? 4. Are staff sensitive to the potential of re-traumatization of the clients during certain procedures (e. g. , urine testing, searching belongings, administration of medications)? 1. Brown, V. B. , Harris, M. , & Fallot, R. (2013). Moving toward trauma-informed practice in addiction treatment: A collaborative model of agency assessment. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 45(5), 386 -393

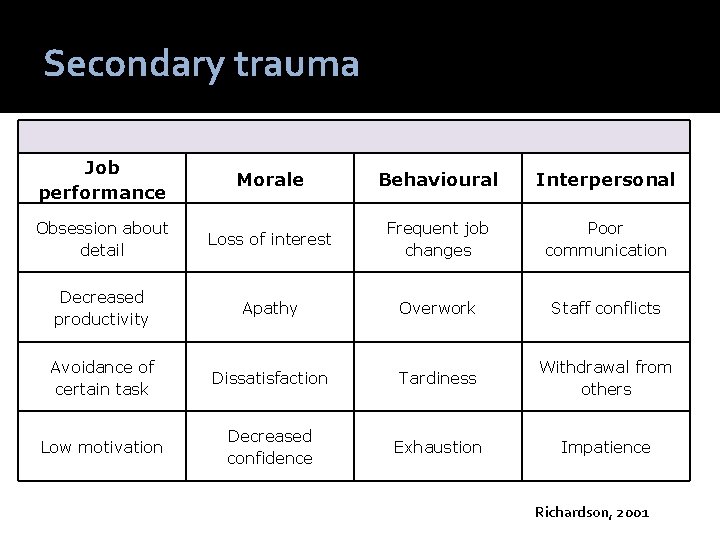

Secondary trauma Job performance Morale Behavioural Interpersonal Obsession about detail Loss of interest Frequent job changes Poor communication Decreased productivity Apathy Overwork Staff conflicts Avoidance of certain task Dissatisfaction Tardiness Withdrawal from others Low motivation Decreased confidence Exhaustion Impatience Richardson, 2001

Addressing secondary trauma Resilience Alliance Intervention Who new and veteran staff at all levels of the organizational structure (child protective specialists, supervisors, managers and deputy directors). What 3 core concepts – optimism, mastery and collaboration Teaches / helps staff apply emotion regulation and other resilience related skills Outcome: increasing self-reported resilience and perceived coworker and supervisor support decreasing negative emotions and perceptions of themselves and their work. ACS-NYU Children’s Trauma Institute. (ND). Addressing Secondary Traumatic Stress Among Child Welfare Staff (pp. 5). New York, NY: NYU.

TRAUMA INFORMED PRACTICE: A SYSTEM-WIDE QUALITY IMPROVEMENT STRATEGY

Becoming trauma informed � Becoming trauma informed requires a range of adjustments in practice and system designs, supported by research, innovative change and inspired leadership. This is a tall order, and requires complex thinking. � Becoming trauma informed benefits from collaboration and cooperation between all levels of service delivery. � Becoming trauma informed is an ongoing process of system change and quality improvement, requiring constant adaptations and ongoing monitoring. Poole, N. , & Greaves, L. (Eds. ). (2012). Becoming Trauma Informed. Toronto, ON: Centre for Addiction and Mental Health

Reflection questions What are my underlying assumptions about the experience of those with trauma and how people recover? How might our agencies and systems of care: 1. Unintentionally contribute to trauma responses 2. Minimize the effects of trauma or potential for re- traumatization What might I contribute (along with my colleagues) as we work on TIP together?

Nancy Poole www. bccewh. bc. ca www. coalescing-vc. org Blog: fasdprevention. wordpress. com

References Acoose, S. , Blunderfield, D. , Dell, C. , & Desjarlais, V. (2009). Beginning with our voices: How the experiential stories of First Nations women contribute to a national research project. Journal of Aboriginal Health, 35 -43. ACS-NYU Children’s Trauma Institute. (ND). Addressing Secondary Traumatic Stress Among Child Welfare Staff (pp. 5). New York, NY: NYU Azeem, M. W. , Aujla, A. , Rammerth, M. , Binsfeld, G. , Jones, R. B. (2011). Effectiveness of Six Core Strategies Based on Trauma Informed Care in Reducing Seclusions and Restraints at a Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Hospital. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 24, 11– 15 Bloom, S. L. , & Farragher, B. (2013). Restoring Sanctuary: A new operating system for trauma-informed systems of care New York, NY: Oxford University Press Brave Heart, M. Y. H. (1998). The return to the sacred path: Healing the historical trauma response among the Lakota. Smoth College Studies in Social Work, 68(3), 287 -305. Briere, J. A. S. (2006). Principles of trauma therapy: A guide to symptoms, evaluation, and treatment. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. Brown, V. B. , Harris, M. , & Fallot, R. (2013). Moving toward trauma-informed practice in addiction treatment: A collaborative model of agency assessmen t. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 45(5), 386 -393 CAMH. (May 2008). Restraint Minimalization Taskforce Final Report. Toronto, ON: Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. Chadwick Trauma-Informed Systems Project. (2013). Creating trauma-informed child welfare systems: A guide for administrators (2 nd ed. , pp. 131). San Diego, CA: Chadwick Center for Children and Families. Carroll, K. M. & Miller, W. R, eds. (2006) Rethinking substance abuse: what the science shows, and what we should do about it. New York: Guilford Press Chambers, J. (2012). What do client rights have to do with trauma-informed care? In N. Poole & L. Greaves (Eds. ), Becoming Trauma Informed (pp. 317 -325). Toronto, ON: Centre for Addiction and Mental Health Chansonneuve, D. (2007). Reclaiming Connections: Understanding Residential School Trauma among Aboriginal People. Ottawa, ON: Aboriginal Healing Foundation Cohen, J. A. , & Mannarino, A. P. (2008). Trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy for children and parents. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 13(4), 158162. doi: 10. 1111/j. 1475 -3588. 2008. 00502. x Collins, K. S. , Strieder, F. H. , De. Panfilis, D. , Tabor, M. , Clarkson-Freeman, P. A. , Linde, L. , & Greenberg, P. (2011). Trauma Adapted Family Connections: Reducing Developmental and Complex Trauma Symptomatology to Prevent Child Abuse and Neglect. [Article]. Child Welfare, 90(6), 29 -47. Covington, S. S. (2003). Beyond Trauma: A Healing Journey for Women. Center City, MN: Hazeldon. Covington, S. (2004). Voices: A program for self-discovery and empowerment for girls. Facilitator guide. Carson City, NV; The Change Companies. Pg. 18. Clark, H. W. , & Power, A. K. (2005). Women, co-occurring disorders, and violence study: A case for trauma-informed care. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 28(2), 145 -146.

References (Part 2) Crime & Justice Institute. (January 26, 2006). Interventions for High-Risk Youth: Applying Evidence-Based Theory and Practice to the Work of Roca. Boston, MA: Crime & Justice Institute. Dell, C. A. , & Clark, S. (2009). The role of the treatment provider in Aboriginal women's healing from illicit drug abuse. Available from: www. coalescingvc. org/virtual. Learning/community 5/documents/Cmty 5_Info. Sheet 2. pdf, (cited 2009 May 30). Felitti, V. , Anda, R. , Nordenberg, D. , Williamson, D. , Spitz, A. , Edwards, V. , . . . Marks, J. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: the adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14, 245– 258. Fallot, R. , & Harris, M. (2009). Creating cultures of trauma-informed care (CCTIC): A self-assessment and planning protocol. 2. 2(7), 1 -18. Retrieved from http: //www. trauma-informed. ca/traumafiles/Trauma-informed_Toolkit. pdf Fallot, R. , & Bebout, R. (2012). Acknowledging and Embracing "the Boy inside the Man": Trauma-informed Work with Men. In N. Poole & L. Greaves (Eds. ), Becoming Trauma Informed (pp. 165 -174). Toronto, ON: Centre for Addiction and Mental Health Guarino, K. , Soares, P. , Konnath, K. , Clervil, R. , and Bassuk, E. (2009). Trauma-Informed Organizational Toolkit. Rockville, MD: Center for Mental Health Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, and the Daniels Fund, the National Child Traumatic Stress Network, and the W. K. Kellogg Foundation. Harris, M. , & Fallot, R. , D. (2001). Using Trauma Theory to Design Service Systems. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass Harrison, R. L. , & Westwood, M. J. (2009). Preventing vicarious traumatization of mental health therapists: Identifying protective practices. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 46(2), 203 -219. Haskell, L. (2003). First Stage Trauma Treatment: A guide for mental health professionals working with women. Toronto, ON: Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. Haskell, L. (2012). A developmental understanding of complex trauma In N. Poole & L. Greaves (Eds. ), Becoming Trauma Informed (pp. 9 -27). Toronto: Centre for Addiction and Mental Health Haskell, L. , & Randall, M. (2009). Disrupted Attachments: A social context complex trauma framework and the lives of Aboriginal Peoples in Canada. Journal of Aboriginal Health, 5(3), 48 -99. Herman, J. L. (1992). Trauma and Recovery. New York: Harper Collins Hopper, E. K. , Bassuk, E. L. , & Olivet, J. (2010). Shelter from the storm: Trauma-informed care in homelessness services settings. The Open Health Services and Policy Journal, 3, 80 -100. Jean Tweed Centre. (March 2013). Trauma Matters: Guidelines for Trauma-Informed Services in Women's Substance Use Services Toronto, ON. Klinic Community Health Centre. (2013). Trauma-informed: The Trauma Toolkit Retrieved from http: //trauma-informed. ca/about-us/resources Markoff, L. S. , Reed, B. G. , Fallot, R. D. , Elliott, D. E. , & Bjelajac, P. (2005). Implementing trauma-informed alcohol and other drug and mental health services for women: Lessons learned in a multisite demonstration project. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 75(4), 525 -39 Miller, W. R. & Rollnick, S. (2013). Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change, 3 rd Ed. New York: Guilford Press.

References (Part 3) Najavits, L. M. (2002). Seeking Safety: A Treatment Manual for PSTD and Substance Abuse. New York, NY: Guilford Press. Najavits, L. M. , Runkel, R. , Neuner, C. , Frank, A. F. , Thase, M. E. , Crits-Christoph, P. , & Elaine, J. (2003). Rates and symptoms of PTSD among cocainedependent patients. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 64(5), 601 -606. Ogden, P. , Minton, K. , & Pain, C. (2006). Trauma and the Body: a Sensorimotor Approach to Psychotherapy. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. Perry, J. C. , Herman, J. L. , Van der Kolk, B. A. , & Hoke, L. A. (1990). Psychotherapy and psychological trauma in borderline personality disorder. Psychiatric Annals, 20(1), 33 -43. Poole, N. , & Greaves, L. (Eds. ). (2012). Becoming Trauma Informed. Toronto, ON: Centre for Addiction and Mental Health Poole, N. , Urquhart, C. , Jasiura, F. , Smylie, D. , & Schmidt, R. (May 2013). Trauma Informed Practice Guide Victoria, BC: British Columbia Centre of Excellence for Women's Health and Ministry of Health, Government of British Columbia. Prescott, L. , Soares, P. , Konnath, K. , & Bassuk, E. (2008). A Long Journey Home: A guide for generating trauma-informed services for mothers and children experiencing homelessness. Rockville, MD: Center for Mental Health Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; and the Daniels Fund; National Child Traumatic Stress Network; and the W. K. Kellogg Foundation. Rich, J. , Corbin, T. , Bloom, S. L. , Rich, L. , Evan, S. , & Wilson, A. (2009). Healing the Hurt: Trauma-Informed Approaches to the Health of Boys and Young Men of Color. Philadelphia, PA: Drexell University School of Public Health, Drexel University College of Medicine, The California Endowment. SAMHSA. (2014). Treatment Improvement Protocol 57 Saakvitne, K. W. , & Pearlman, L. (1996). Transforming the pain: A workbook for vicarious traumatization. New York: Norton. Schachter, C. , Stalker, C. A. , Teram, E. , Lasiuk, G. C. , & Danilkewich, A. (2008). Handbook on Sensitive Practice for Health Care Practitioners: Lessons from Adult Survivors of Childhood Sexual Abuse. Ottawa, ON: National Clearinghouse on Family Violence. Siegel, D. J. (1999). The Developing Mind: Toward a Neurobiology of Interpersonal Experience. New York: Guilford Press. Urquhart, C. , & Jasiura, F. (2012). Collaborative change conversations: Integrating trauma-informed care and motivational interviewing with women. In N. Poole & L. Greaves (Eds. ), Becoming Trauma Informed (pp. 59 -70). Toronto, ON: Centre for Addiction and Mental Health Van der Kolk, Mc. Farlane & Weisaeth (Eds. ) (1996/2006). Traumatic Stress: the effects of overwhelming experience on mind, body, and society. Williams, J. , Paul, J. (2008). Informed Gender Practice: Mental health Yellow Bird, M. (2013). Neurodecolonization: Applying mindfullness research to decolonizing social work In M. Gray, J. Coates, M. Yellow Bird & T. Heatherington (Eds. ), Decolonizing Social Work. Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing.

- Slides: 67