Tragedy From Aristotles Poetics and Sophocles Oedipus Rex

- Slides: 35

Tragedy From Aristotle’s Poetics and Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex to Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus & Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet

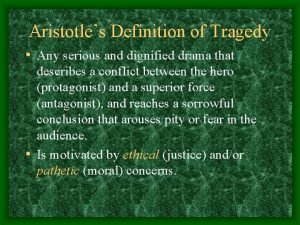

Classical Tragedy 5 th c BCE • Chorus (15 men) • Tragic hero (hamartia, hubris; high station and moral worth) • Catastrophe/reversal; unities • Loses material things but has epiphany/anagnorisis • Catharsis; audiences experience pity & relief

Senecan Tragedy Roman 4 th c BCE-65 • • • Knew in Medieval 5 acts Revenge; bloody No catharsis Fortuna turns wheel to bring high low

Miracle & Mystery Plays (10 th – 14 th centuries) • Miracle plays: lives of saints • Mystery plays: stories from Old and New Testaments • Performed in church as part of holy days • Moved outside onto wagons; guilds performed

Morality Plays (15 th c) • 1 plot • About common people; characters often allegories • Dramatized allegories representing a Christian’s life and his quest for salvation • Show audience that fortune is unpredictable

Medieval Staging • Plays performed in church then moved to courtyard • Mobile, no stage • Used wagons, move episodes from one location to another • Guilds put them on • Symbolic props

Renaissance & Restoration Tragedy • Hero starts good/turns evil • Hero usually important if not ruler • Fall from grace marked by reversals and discoveries • Audience experiences fear and pity; catharsis • Added comic relief and subplots

Traits from Morality Plays in Doctor Faustus • Good and Bad Angel • 7 Deadly Sins • Presence of Lucifer and his cohorts • Vision of Hell • Chorus (1 person) to open the play • Allegory

Origins of Story • Johann Faust (1488) bragged he’d sold his soul to the devil for magical powers. • Wandered Germany until death in 1541 • 1587 story about him appeared in Germany: The History of the Damnable Life and Deserved Death of Doctor John Faustus • Translation in English 1592 • 1592 first performance of Doctor Faustus

Influences on Authorship • Written between 1588 -1592? • Perkins, don at Cambridge, preached about witchcraft because of popular interest in discovery and detection of witches; witchcraft is like “desiring to become a god, longing to win reputation, dissatisfaction with inward gifts received such as knowledge, wit, understanding, memory, and suchlike. ”

Problems with Authorship • Faustus entered official records in 1601 but not as new work. • In 1602 at least 2 others paid for work on Faustus • First published in 1604 • 1616 another version printed • Today’s version based on work of Sir Walter Gregg

Problems with Authorship, cont. • Quality not consistent. • Most believe that Marlowe wrote tragic beginning and end; some that he did most of Acts 1, 3 & 5. • Collaborators wrote much of comical middle sections.

Renaissance authorship • • Patrons; sold to printer or bookseller No royalties; no copyright; pay poor Censored by government and church Printing legal only in London, Cambridge & Oxford UP after passed censorship • 1579 John Stubbs lost his right hand as penalty for attempting to publish pamphlet against proposed French marriage

Patronage • First professional writers; University wits tried to make a living with their writing • Who will be offended? Who will pay? • Theatrical manager Philip Henslowe’s diary is full of entry after entry about university graduates in prison for debt or eking out a miserable existence writing plays.

Authorship/Ownership • 60 % literacy by 1530 • Writing passed by hand, copied pieces they liked in their own commonbooks, often no original author given. • Plays belonged to acting companies, not the playwright. Text changed with actors and situation; dramatists collaborated/changed. • Plays evolved with no printed copy to stabilize the correct text. Ben Jonson first to print play texts--after Marlowe’s death.

Additions to Faust Legend • Connections to witchcraft and Perkins’s motivations for witchcraft from sermons • Ambivalence of Faustus • Thematic elements

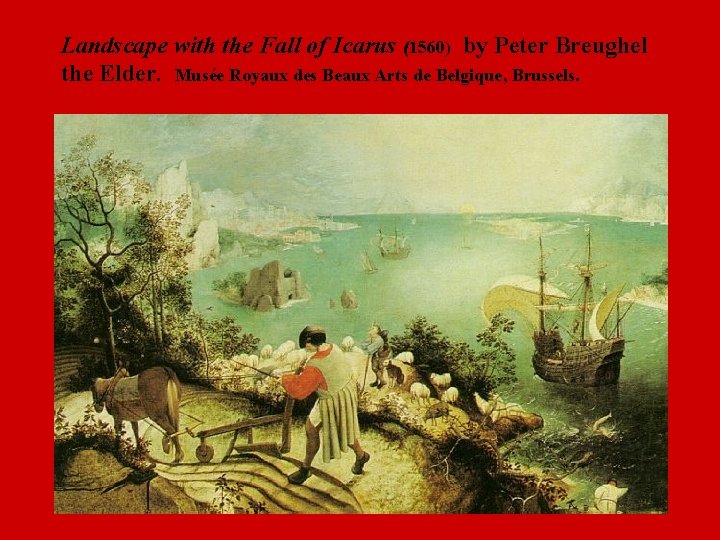

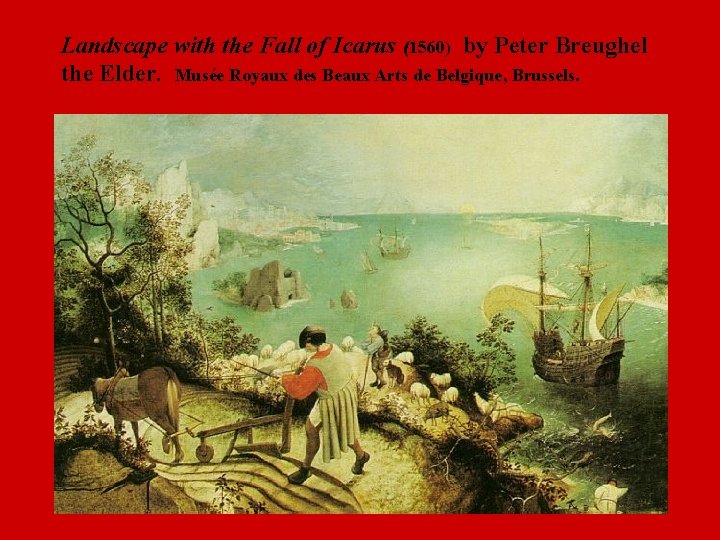

Allusions • References to literature, art, music, historical events and people • Why put Faustus in Wittenberg? What famous medieval person is connected with the university in Wittenberg? • Burning chair in Hell; Hungarian peasant rebel Gyorgy Dozsa (1514) • Icarus and Daedalus

Landscape with the Fall of Icarus (1560) by Peter Breughel the Elder. Musée Royaux des Beaux Arts de Belgique, Brussels.

Allegory • Form of extended metaphor • Characters in a narrative have symbolic meaning as well as literal meaning • Personification of abstract qualities • Example: Everyman is the name of a character in a medieval narrative who goes through the conflicts of the plot, but he also is a symbol for all Christians who struggle through life to find salvation.

Why authors use allegory § To teach moral lessons § To explain universal truths § Marlowe uses these allegorical characters in Faustus: the Good Angel and the Bad Angel. Why? § What function do they serve? § Are they symbols? Of what? § How would they have been presented on stage then? Now?

Another Allegory: The 7 Deadly Sins • • Pride Covetousness Envy Wrath Gluttony Sloth Lechery Which sins does Faustus commit? Why does Marlowe include the 7 Deadlies? Which characters possess these traits?

Why Faustus abandons learning • Philosophy: “…though it has attained that end” (I. i. 10). • Medicine: “Could’st thou make men to live eternally / Or being dead raise them to life again” (I. i. 22 -24). • Law: “Too servile and illiberal for me” (I. i. 34).

Why give up on religion just as he gets his doctorate in theology? • “. . . we must sin, and so consequently die. / Ay, we must die an everlasting death” (I. i. 4043). • Syllogism: 2 statements which, if true, make a 3 rd statement true. • Example: Socrates is a man; all men are mortal; therefore, Socrates is mortal.

Faustus’s Syllogism • He has created a syllogism. Is it logical? • “. . . we must sin, and so consequently die. / Ay, we must die an everlasting death” (I. i. 40 -43). • What is wrong with his thinking? Why is it ironic?

Logical Fallacy? • Faustus has taken the quote out of context and ignores the rest of the quote which promises mercy for those sinners willing to repent. • The world’s greatest scholar comes to ruin because of faulty research and reasoning; he misreads an important quote from an untrustworthy source.

What to look for as you read § Chorus: What functions does it serve? Appears 4 times: to introduce heroic nature of the play, to foreshadow, to provide exposition, and to identify the setting. § Irony: Look at Faustus’s arguments and thinking. What logical mistakes does the great scholar make?

What else to look for • • Allegory Allusions Comic relief; parallel subplots Ideals/beliefs from Reformation, Medieval Period, and Renaissance; • Beliefs about witchcraft and the devil • Antithesis/contrast

Ask yourself • Is Faustus’s fate predestined or does he have free will? • What is knowledge? • Does Faustus ever find knowledge? • What does Faustus really want? • Can Faustus be both hero and villain? Bad and good? What evidence can you find in the play?

Sources Barnet, Sylvan, ed. “Introduction. ” Doctor Faustus. Christopher Marlowe. New York: Signet Books, 1969. vii-xix. Bevington, David. “General Introduction. ” The Complete Works of Shakespeare. New York: Harper. Collins, 1992. Rpt. in Doctor Faustus: Divine in Show. Ed. Mc. Alindon, T. Twayne’s Masterworks Studies. New York: Twayne, 1994. 152 -170. Duncan-Jones, Katherine. “Devil May Care. ” New Statesman 131 (1996): 42 -44. Mc. Alindon, T. Doctor Faustus: Divine in Show. Twayne’s Masterworks Studies. New York: Twayne, 994. “The Sixteenth Century I 1485 -1603): Introduction. ” The Norton Anthology of English Literature. 6 th ed. Ed. M. H. Abrams. New York: W. W. Norton, 1996. 253 -273. Stenning, Rodney. “The ‘Burning Chair’ in the B-text of Doctor Faustus. ” Notes and Queries 43 (1996): 144 -145. Stumpf, Thomas A. “Images and Music. ” Freshman Seminar: Visits to Hell. (2001). 29 Sept. 2004. <http: //www. unc. edu/courses/2001 fall/engl/006 m/005/thumbnails. html. > Walton, Brenda. Lessons for Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus. Orlando, FL: Network for Instructional TV, 1998. 12 Oct. 2004. <http: //www. teachersfirst. com/lessons/marl. htm>.

Oedipus rex episode 2 summary

Oedipus rex episode 2 summary Sophocles oedipus rex summary

Sophocles oedipus rex summary Oedipus rex episode 3 summary

Oedipus rex episode 3 summary Sophocles oedipus rex summary

Sophocles oedipus rex summary Synopsis of oedipus rex

Synopsis of oedipus rex Oedipus family tree

Oedipus family tree Megalopsychia tragedy definition

Megalopsychia tragedy definition Aristotelian tragedy definition

Aristotelian tragedy definition Antigone overview

Antigone overview Poetics of culture

Poetics of culture Conclusion of aristotle

Conclusion of aristotle New criticism definition

New criticism definition What is cognitive poetics

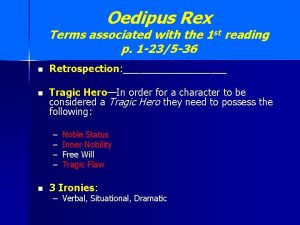

What is cognitive poetics 6 traits of a tragic hero

6 traits of a tragic hero Aristotle poetics mla citation

Aristotle poetics mla citation Symbols for oedipus

Symbols for oedipus Oedipus rex blindness

Oedipus rex blindness Oedipus prologue

Oedipus prologue On misunderstanding the oedipus rex

On misunderstanding the oedipus rex Oedipus the king study guide

Oedipus the king study guide Prologue of oedipus rex

Prologue of oedipus rex Background of oedipus rex

Background of oedipus rex Dramatic structure of oedipus rex

Dramatic structure of oedipus rex Oedipus rex practice multiple choice questions answers

Oedipus rex practice multiple choice questions answers Lascom welding

Lascom welding Verbal irony example

Verbal irony example Situational irony in oedipus rex

Situational irony in oedipus rex Oedipus rex riddle

Oedipus rex riddle Setting of oedipus rex

Setting of oedipus rex Questions about oedipus

Questions about oedipus Asophocles

Asophocles Oedipus the king quotes

Oedipus the king quotes Costume of oedipus rex

Costume of oedipus rex Oedipus rex background

Oedipus rex background Symbols in oedipus rex

Symbols in oedipus rex Why is the priest doing this

Why is the priest doing this