Tony Morrison Sula 1975 Tony Morrison The novels

![Tony Morrison Ø“He [the bargeman] shook his head in disgust at the kind of Tony Morrison Ø“He [the bargeman] shook his head in disgust at the kind of](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/6d1d7d51319396f641c4ad3df072a7d2/image-22.jpg)

- Slides: 35

Tony Morrison ØSula, 1975

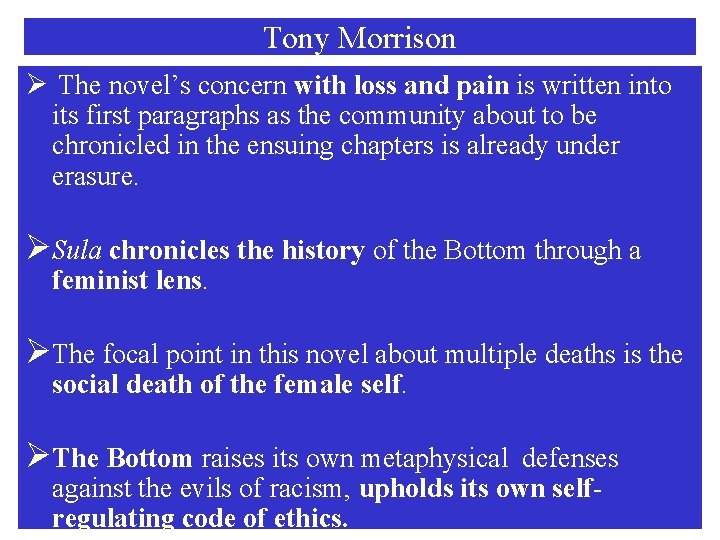

Tony Morrison Ø The novel’s concern with loss and pain is written into its first paragraphs as the community about to be chronicled in the ensuing chapters is already under erasure. ØSula chronicles the history of the Bottom through a feminist lens. ØThe focal point in this novel about multiple deaths is the social death of the female self. ØThe Bottom raises its own metaphysical defenses against the evils of racism, upholds its own selfregulating code of ethics.

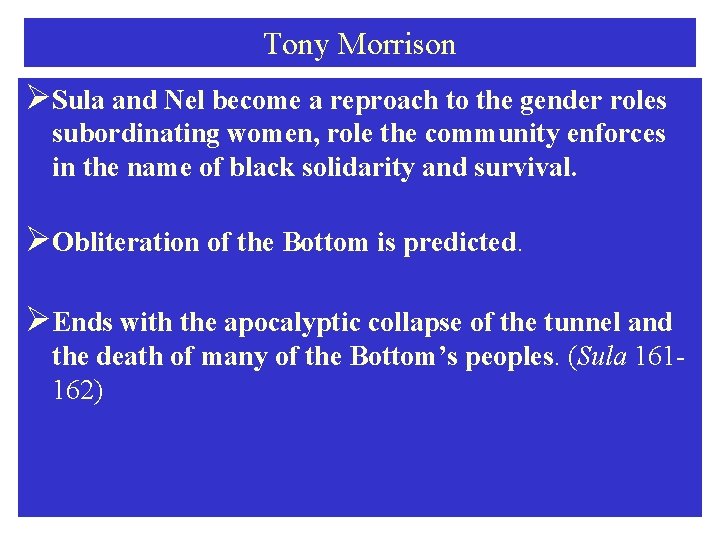

Tony Morrison ØSula and Nel become a reproach to the gender roles subordinating women, role the community enforces in the name of black solidarity and survival. ØObliteration of the Bottom is predicted. ØEnds with the apocalyptic collapse of the tunnel and the death of many of the Bottom’s peoples. (Sula 161162)

Tony Morrison Ø It portraits the victimization that continues beyond slavery and the founding of the Bottom, the destruction of the tunnel and the demise of the community so that a golf course can be built. (3) ØBoth the origin and the ending of the Bottom reflect the primacy of white interests and the concomitant marginalisation of black ones.

Tony Morrison ØAt first glance, Sula appears to be the only one in the novel who can look upon trauma and pain with distance. ØIn the creation of Sula, Morrison experiments with the anti-conventionalism – the woman who will not nurture or take her place in the heterosexual social order that defines women like Helene Wright and her daughter Nel.

Tony Morrison Ø She is in part a feminist experiment in that Morrison tries to imagine a self-creation, rebelling from, and at odds with, all previous prescriptions. ØIn Sula, Morrison imagines a woman who, intent on opening up all parts of herself rather than folding them away, flouts conventions and received morality. Ø In cutting Sula loose from the responsibilities, pieties and proprieties of conventional womanhood, Morrison appears also to cut her loose from feeling, to give her a detachment and distance and to make her in many ways apparently shockingly evil.

Tony Morrison ØSula is a site of projection, but through her own glorious defiance and self-isolation: “Hellfire don’t need lighting and it’s already burning in you…” “Whatever’s burning in me is mine”; “You sold your life for twenty-three dollars a month. ” “You throwed yours away. ” (93); “It’s mine to throw. ”; ‘My lonely is mine’. (143) Ø Community and Identity ØThe question of the individual’s relationship to community is compelling in all Morison’s works.

Tony Morrison ØDetachment and isolation versus connection and involvement is a subject that has long interested her. ØSula, too, is an assessment of isolation and connection, and the search for her own identity. ØSula’s assertion of female selfhood – claiming freedom from structural roles of gender- is seen as divisive, as a centrifugal force to react against. ØHer early and unexplained death reveals the absence of a viable feminist space within black collectivity.

Tony Morrison ØOne of the paradoxes of identity is that we can only know ourselves as selves if we have a sense of separateness, but at the same time we can only know ourselves in relation to others. ØJust as Sula needs to be isolated from the Medallion community in order to create and contemplate herself, so she also needs to know herself in relation to it.

Tony Morrison ØSula’s identity depends on he defiant alienation from the community; yet that identity also depends, as does the community’s sense of itself, on comparison and relationship. ØIf Sula is a dead girl, she also represents the female self sabotaged by the community’s “good woman”, Nel.

Tony Morrison ØThe other side of the coin ØNel’s early assimilation of her self –her “me” – into her husband Jude’s self, can be read as the project of a masculinist chauvinism assimilating and erasing the claims of feminism. Ø “The two of them together would make one Jude” (Sula 83). Such assimilation is emphatically refused by Sula. ØSula has a negative view of how mothers raise their daughters: “Under Helen’s hand the girl became obedient and polite. Any enthusiasms that little Nel showed were calmed by the mother until she drove he daughter’s imagination underground. ” (18)

Tony Morrison Ø“Those with husbands had folded themselves into starched coffins, their sides bursting with other people’s skinned dreams and bony regrets”. (122) ØSula’s female heritage is an unbroken line of “manloving” women who exist as sexually desiring subjects rather than as objects of male desire. ØNel’s sexuality is not expressed in itself and for her own pleasure, but rather, for the pleasure of her husband”. (Sula 139)

Tony Morrison ØBecause Nel’s sexuality is harnessed to and only enacted within the institutions that sanction sexuality for women –marriage and family- she does not own it. ØIt is impossible for her to imagine sex without Jude. After she finds him and Sula in the sex act she describes her thighs – the metaphor for her sexuality- as “empty and dead”… and it was Sula who had taken the life from them …” She concludes that “the both of them… left her with no thighs and no heart just her brain raveling away” (Sula 110 -111)

Tony Morrison Ø Sula’s stance costs her dearly; she lives and dies in isolation. ØWhen questioned by Nel about why did she take her husband away from her, Sula replies: Ø“And you didn’t love me enough to leave him alone. To let him love me. You had to take him away. ” “What you mean take him away? I didn’t kill him. I just fucked him. If we were such good friends, how come you couldn’t get over it? ” (145)

Tony Morrison ØSula never achieves completeness of being. She dies in the fetal position welcoming this “sleep water, ” in a passage that clearly suggests, she is dying yet aborting (Sula 149). ØShe has not avoided pain or denied feeling, but refused merely to school or order her feelings to suit conventional practices.

Tony Morrison ØBut she lives and dies in her own terms: Ø“I sure lived in this world. Ø“Really? What do you have to show for it? ” Ø “Show? To who? Girl, I got my mind. And what goes on in it. Which is to say, I got me. ” Ø“Lonely, ain’t it? ØYes, but my lonely is mine. Now your lonely is somebody else’s. Made by somebody else and handed to you. Ain’t that something? A second hand lonely. ” 141.

Tony Morrison ØThus, to escape, Sula has only two options: to become a “man” or to die. She chooses death. (Sula 142) ØMorrison has stated that: “If they were one woman [Nel and Sula], they would be complete. ”

Tony Morrison ØThe Community ØThe community sees Sula ultimately as betraying and alienating family, friends, and neighbors, thereby causing her own death. ØThus, in their eyes she becomes a pariah, living outside the laws and mores of the community.

Tony Morrison ØWhen Sula returns to the Bottom after a ten-year absence, she is accompanied by plague of robins that shit all over the community and then die. ØSula too shits on the Bottom community and dies. ØShe is prepared for burial by white people, since no one in the community would “do” for her. (Sula 173)

Tony Morrison ØThe community, rather than focusing is attention on the pervasive evils of racism and poverty that continually threatened it, the community expends its energy on outlasting the evil Sula. ØHowever, as always, in Morrison, racism is clear in many places in the novel, for instance when Chicken Little drowns:

![Tony Morrison ØHe the bargeman shook his head in disgust at the kind of Tony Morrison Ø“He [the bargeman] shook his head in disgust at the kind of](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/6d1d7d51319396f641c4ad3df072a7d2/image-22.jpg)

Tony Morrison Ø“He [the bargeman] shook his head in disgust at the kind of parents who would drown their own children. When, he wondered, will those people ever be anything but animals, fit for nothing but substitutes for mules, only mules didn’t kill each other the way niggers did”. (63)

Tony Morrison ØThe narrative strongly suggests that one cannot belong to the community and preserve the imagination, for the orthodox vocations for women – marriage and motherhood- restrict if not preclude imaginative expression. ØThe community by presenting no viable solution for the individual African’s struggle for freedom – Sula can neither survive without the community nor fly way and leave it.

Tony Morrison ØThe Form of the Novel Ø While the chapter headings promise chronological linearity, the text demonstrates that lived time is anything but continuous, that things don’t happen when they happen, that neither intentionality nor reaction can naturalize trauma into consecutive narrative. ØSula is divided precisely into two equal parts (I and II and contain almost the same number of pages) and characters introduced and developed in part I are brought back in part II. ØThe novel begins in memory and concludes with Nel’s crucial remembrance of Sula.

Tony Morrison ØBy ending Sula in 1965, some years before the time of the beginning passage of the novel, Morrison invites readers to come full circle and begin again, to reexperience the narrative in terms of Nel’s final question about whether the Bottom and in particular the “black people” in general had ever been a community at all. (Sula 166) ØAlthough Sula is structured by linear, chronological time, with each chapter headed by year, these allusive, broadly referential dates serve as public markers for the narratives of private loves and griefs.

Tony Morrison ØHere, as in all Morrison’s novels, historic time is best understood through the duration of private lives, where personal experience in turn acquires its significance only within a historical process. ØAn episodic narrative marked by skips und jumps in time from 1919 to 1965, the novel proceeds with flashbacks and tantalizing gaps, privileging a circular mnemonic time. ØThe narrator provides certain facts, but the drawing of connections is left to the reader.

Tony Morrison ØBearing her name, the narrative suggests that SULA e is the protagonist, the privileged center, but her presence is constantly deferred. ØWe are first introduced to a caravan of characters: Shadrack, Nel, Helene, Evan, the Deweys, Tar Baby, Hannah, and Plumb before we get any sustained treatment of Sula. … the novel is roughly one-third over when Sula is introduced and it continues almost that long after her death. (49)

Tony Morrison ØNot only does the narrative deny the reader a “central” character, but it also denies the whole notion of character as static essence, replacing it with the idea of character as process.

Tony Morrison ØWhereas the former is based on the assumption that the self is knowable, centered, and unified, the latter is based on the assumption that the self is multiple, fluid, relational, and in a perpetual state of becoming. ØSula threatens the reader’s assumptions and disappoints their expectations at every turn. ØIt begins by disappointing the reader’s expectations of a “realistic” and unified narrative documenting black/white confrontation.

Tony Morrison ØAlthough the novel’s prologue, which describes a community’s destruction by white greed and deception, gestures toward “realistic” documentation, leads the reader to expect “realistic” documentation of a black community’ confrontation with a white oppressive world, the familiar and expected plot is in the background. ØThe narrative retreats from linearity privileged in the realistic mode.

Tony Morrison ØThough dates entitled the novel’s chapters, they relate only indirectly to its central concerns and do not permit the reader to use chronology in order to interpret its events in any cause/effect fashion. ØIn other words, the story’s forward movement in time is deliberately nonsequential and without explicit reference to “real” time. ØThe reader never knows quite what to think of characters and events in Sula.

Tony Morrison ØWhether they applaud Eva’ self-sacrifice or deplore her tyranny, whether to admire Sula’s freedom or condemn her heartlessness. ØThe narrative is neither an apology for Sula’s destruction nor an unsympathetic critique of Nel’s smug conformity. ØIt does not reduce a complex set of dynamics opposition o choice between two “pure” alternatives.

Tony Morrison ØThe reader must fill in the narrative’s many gaps, for instance: ØWhy is there no funeral for either Plum o Hannah? ØWhat happens to Jude? ØWhere was Eva during her eighteen-month absence from the Bottom? What really happened to her leg? ØWhere was Sula for ten years? How does Sula support herself after she returns from her ten-year absence?

Tony Morrison ØThe novel’s fragmentary, episodic, elliptical quality helps to thwart textual unity, to prevent a totalized interpretation. ØThe text as a series of scenes and glimpses, each written from scratch. Ø Since none has anything to do with the ones that preceded them, we can never piece the glimpses into a coherent picture. ØWhatever coherence and meaning resides in the narrative, the reader must struggle to create.

Tony Morrison ØThe gaps in the text allow for the reader’s participation in the creation of meaning in the text. ØMorrison has commented on the importance of the “affective and participatory relationship between the artist and the audience, ” and her desire “to have the reader work with the author in the construction of the book”. ØShe adds, “What is left out is as important as what is there”. END

Morrison & morrison ltd

Morrison & morrison ltd Tony cragg « stack » 1975

Tony cragg « stack » 1975 Nnnn aesthetic

Nnnn aesthetic Kierkegaard

Kierkegaard Arctocefali

Arctocefali Peedu sula

Peedu sula Muhammad syakir sula

Muhammad syakir sula Universidad pedagógica san pedro sula

Universidad pedagógica san pedro sula Peedu sula

Peedu sula Sula literary devices

Sula literary devices Classic southern novels

Classic southern novels What is the definition of gothic literature

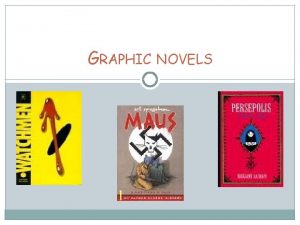

What is the definition of gothic literature Bleed graphic novel definition

Bleed graphic novel definition Hard-boiled detective characteristics

Hard-boiled detective characteristics French gothic novels

French gothic novels Dystopian definition

Dystopian definition Modern american gothic

Modern american gothic What is a splash page in a graphic novel

What is a splash page in a graphic novel Fictional character

Fictional character Dystopian world definition

Dystopian world definition Characteristics of the victorian novel

Characteristics of the victorian novel American modernism characteristics

American modernism characteristics Gothic literature description

Gothic literature description Do you underline titles of articles

Do you underline titles of articles 1962-1975

1962-1975 1975-1958

1975-1958 1975-1959

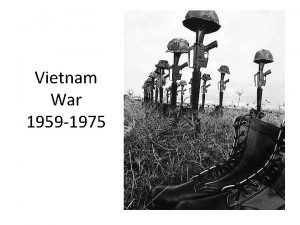

1975-1959 La industria española entre 1855 y 1975

La industria española entre 1855 y 1975 Vietnam 1954

Vietnam 1954 Wood and middleton (1975)

Wood and middleton (1975) Cometa west

Cometa west Family with blue skin

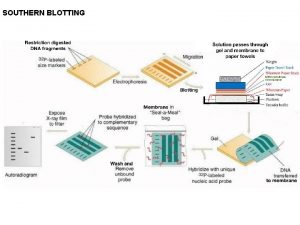

Family with blue skin Blotting

Blotting Saigon 1975

Saigon 1975 Modèle de shapero

Modèle de shapero Fishbein ajzen 1975

Fishbein ajzen 1975