Tonal complexity in Shilluk and its diachronic development

![Null hypothesis: tonal alignment not contrastive in contour tones “[I]t might be that in Null hypothesis: tonal alignment not contrastive in contour tones “[I]t might be that in](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/77463f6ab5e8eb948d4df04442387e2f/image-10.jpg)

![Null hypothesis: tonal alignment not contrastive in contour tones “[T]here is no possible opposition Null hypothesis: tonal alignment not contrastive in contour tones “[T]here is no possible opposition](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/77463f6ab5e8eb948d4df04442387e2f/image-11.jpg)

- Slides: 63

Tonal complexity in Shilluk and its diachronic development Bert Remijsen Otto Gwado Ayoker University of Edinburgh 1

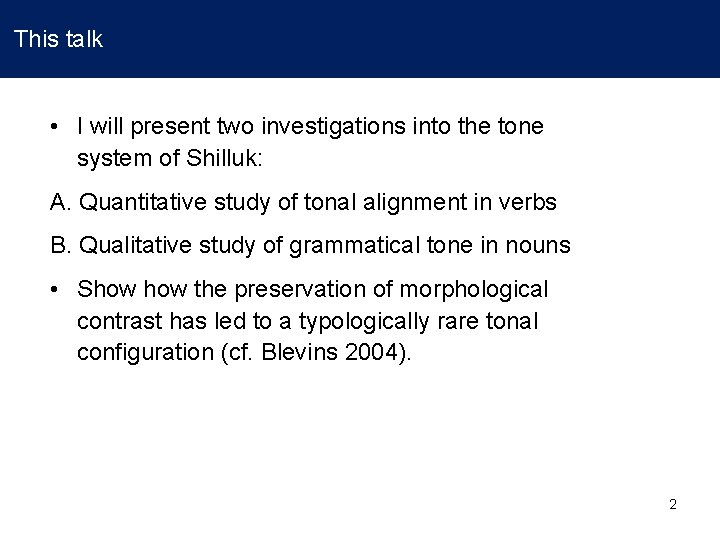

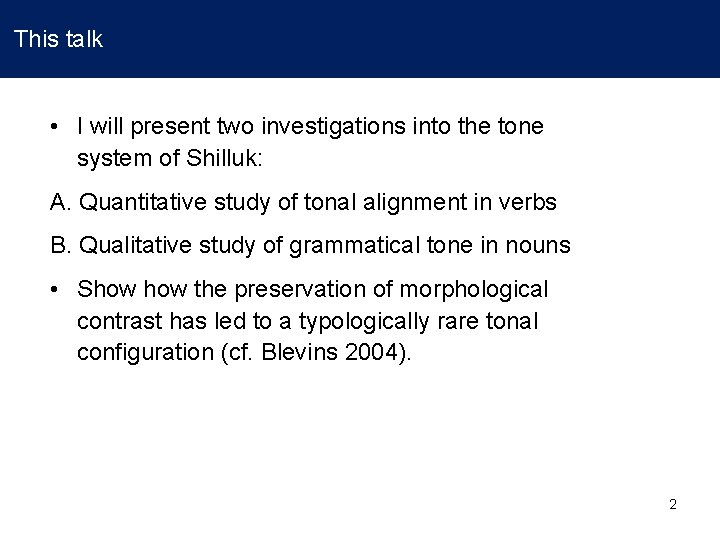

This talk • I will present two investigations into the tone system of Shilluk: A. Quantitative study of tonal alignment in verbs B. Qualitative study of grammatical tone in nouns • Show the preservation of morphological contrast has led to a typologically rare tonal configuration (cf. Blevins 2004). 2

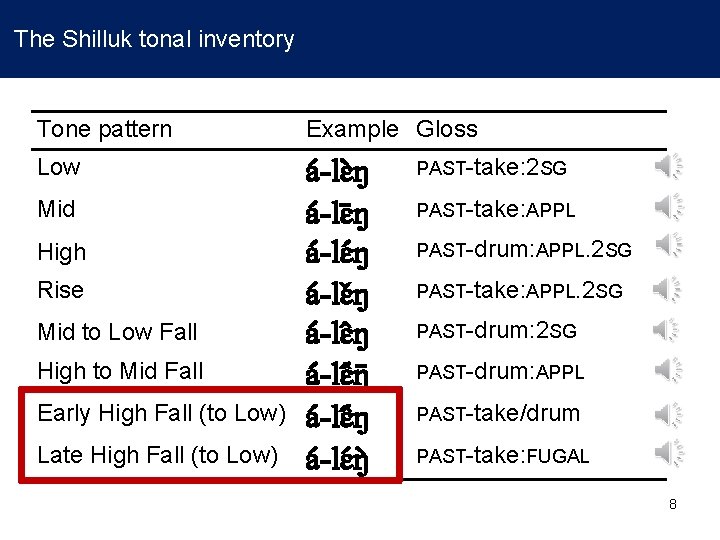

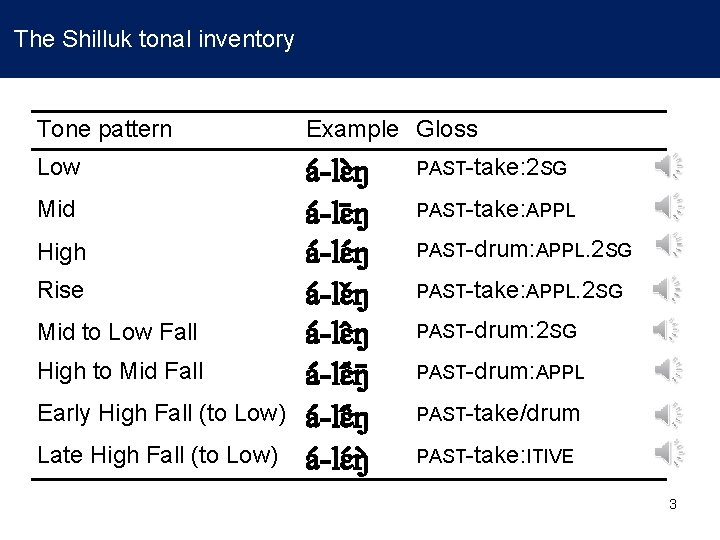

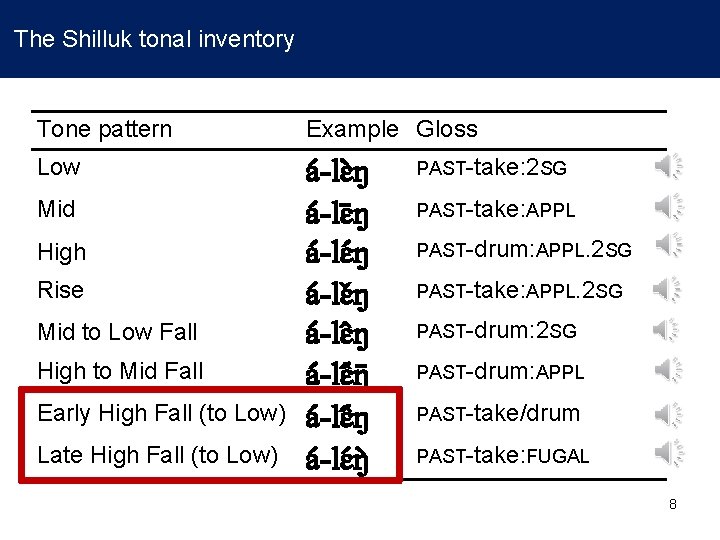

The Shilluk tonal inventory Tone pattern Example Gloss Low a -lɛ ŋ a -lɛ ŋ Mid High Rise Mid to Low Fall High to Mid Fall Early High Fall (to Low) Late High Fall (to Low) PAST-take: 2 SG PAST-take: APPL PAST-drum: APPL. 2 SG PAST-take: APPL. 2 SG PAST-drum: APPL PAST-take/drum PAST-take: ITIVE 3

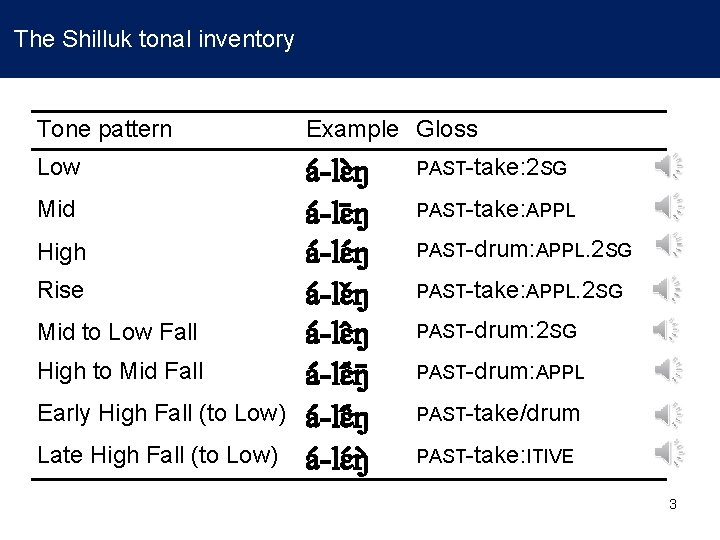

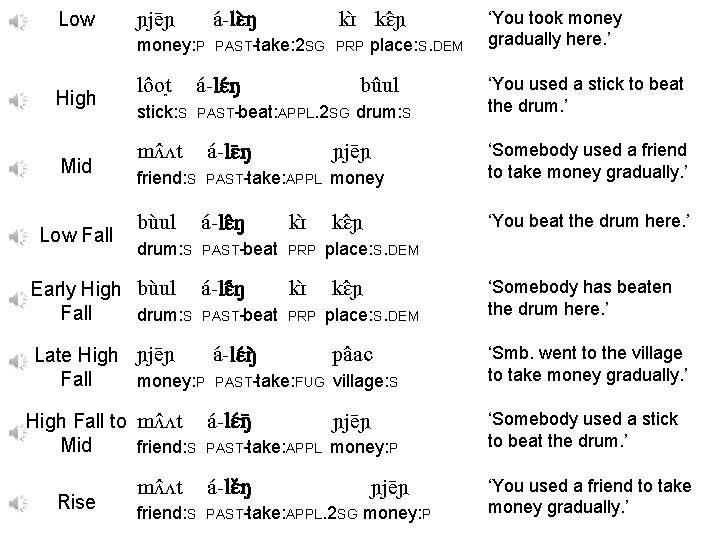

Low High Mid Low Fall ɲje ɲ a -lɛ ŋ kɪ kɛ ɲ money: P PAST-take: 2 SG PRP lo ot a -lɛ ŋ stick: S PAST-beat: APPL. 2 SG place: S. DEM bu ul drum: S ‘You took money gradually here. ’ ‘You used a stick to beat the drum. ’ mʌ ʌt a -lɛ ŋ ɲje ɲ friend: S PAST-take: APPL money ‘Somebody used a friend to take money gradually. ’ kɛ ɲ ‘You beat the drum here. ’ bu ul a -lɛ ŋ kɪ drum: S PAST-beat PRP place: S. DEM kɪ kɛ ɲ Early High bu ul a -lɛ ŋ Fall drum: S PAST-beat PRP place: S. DEM ‘Somebody has beaten the drum here. ’ a -lɛ ŋ pa ac Late High ɲje ɲ Fall money: P PAST-take: FUG village: S ‘Smb. went to the village to take money gradually. ’ ɲje ɲ High Fall to mʌ ʌt a -lɛ ŋ Mid friend: S PAST-take: APPL money: P ‘Somebody used a stick to beat the drum. ’ Rise mʌ ʌt a -lɛ ŋ friend: S PAST-take: APPL. 2 SG ɲje ɲ money: P ‘You used a friend to take money gradually. ’

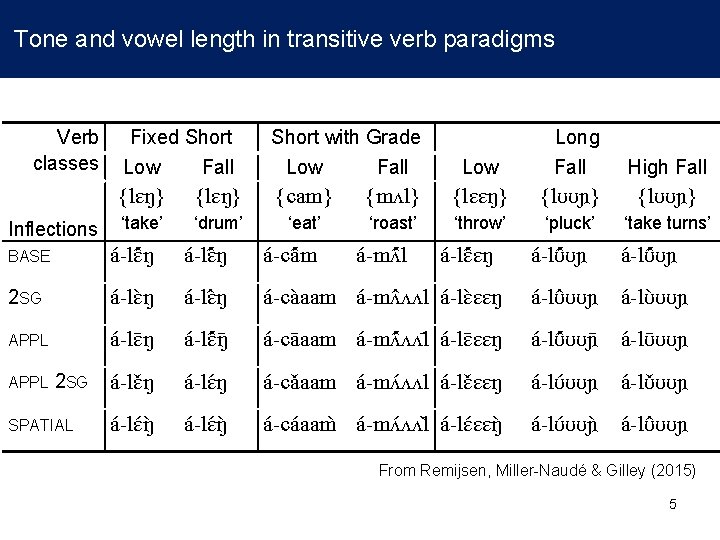

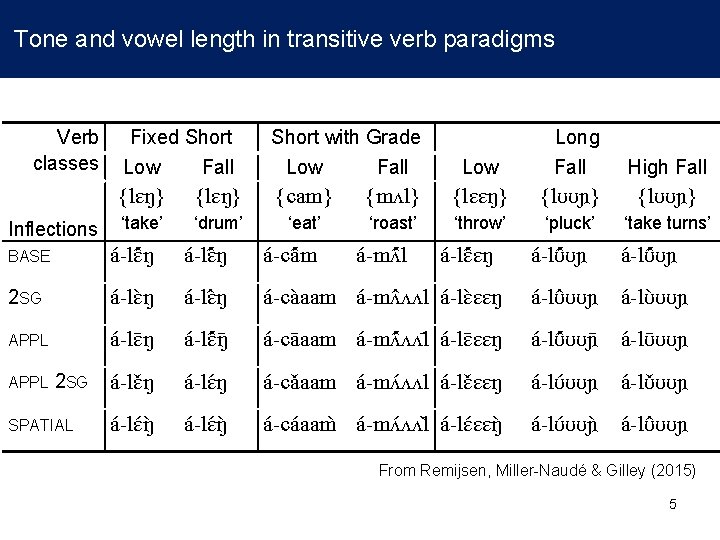

Tone and vowel length in transitive verb paradigms Verb classes Inflections Fixed Short Low Fall Short with Grade Low High Fall ‘take turns’ {cam} {mʌl} {lɛɛŋ} {lʊʊɲ} ‘take’ ‘drum’ ‘eat’ ‘roast’ ‘throw’ ‘pluck’ a -lɛ ŋ a -ca m 2 SG a -lɛ ŋ APPL a -lɛ ŋ SPATIAL Fall {lɛŋ} a -lɛ ŋ 2 SG Low {lɛŋ} BASE APPL Fall Long a -mʌ l a -lɛ ɛŋ {lʊʊɲ} a -lʊ ʊɲ a -ca aam a -mʌ ʌʌl a -lɛ ɛɛŋ a -lʊ ʊʊɲ a -lɛ ŋ a -ca aam a -mʌ ʌʌl a -lɛ ɛɛŋ a -lʊ ʊʊɲ a -lɛ ŋ a -ca aam a -mʌ ʌʌl a -lɛ ɛɛŋ a -lʊ ʊʊɲ From Remijsen, Miller-Naudé & Gilley (2015) 5

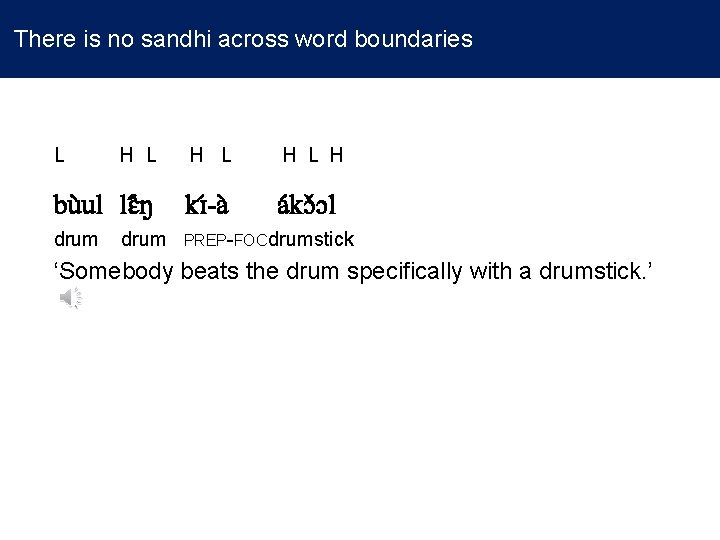

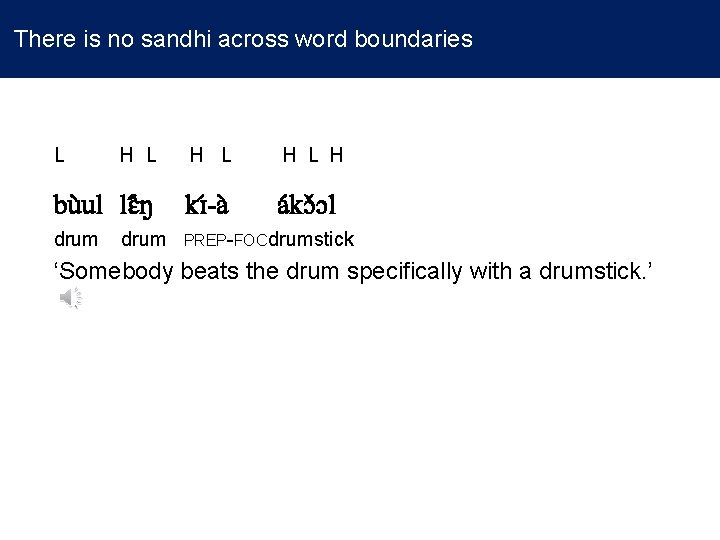

There is no sandhi across word boundaries L H L H bu ul lɛ ŋ kɪ -a a kɔ ɔl drum PREP-FOC drumstick drum ‘Somebody beats the drum specifically with a drumstick. ’

Contrastive tonal alignment (Remijsen & Ayoker 2014)

The Shilluk tonal inventory Tone pattern Example Gloss Low a -lɛ ŋ a -lɛ ŋ Mid High Rise Mid to Low Fall High to Mid Fall Early High Fall (to Low) Late High Fall (to Low) PAST-take: 2 SG PAST-take: APPL PAST-drum: APPL. 2 SG PAST-take: APPL. 2 SG PAST-drum: APPL PAST-take/drum PAST-take: FUGAL 8

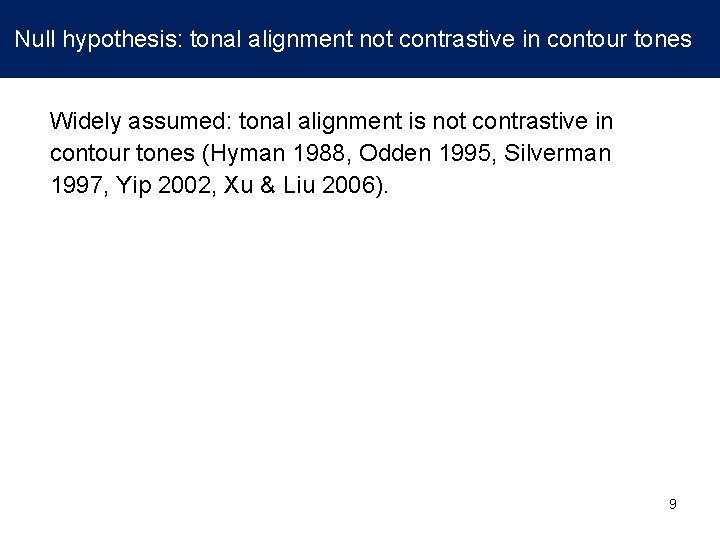

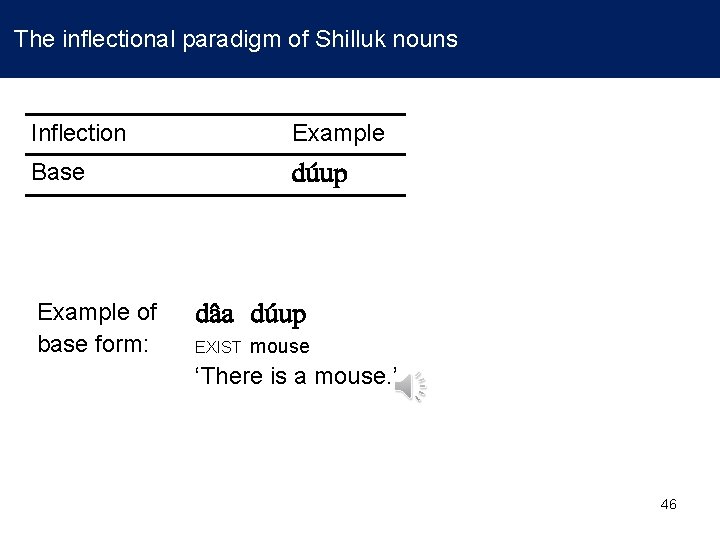

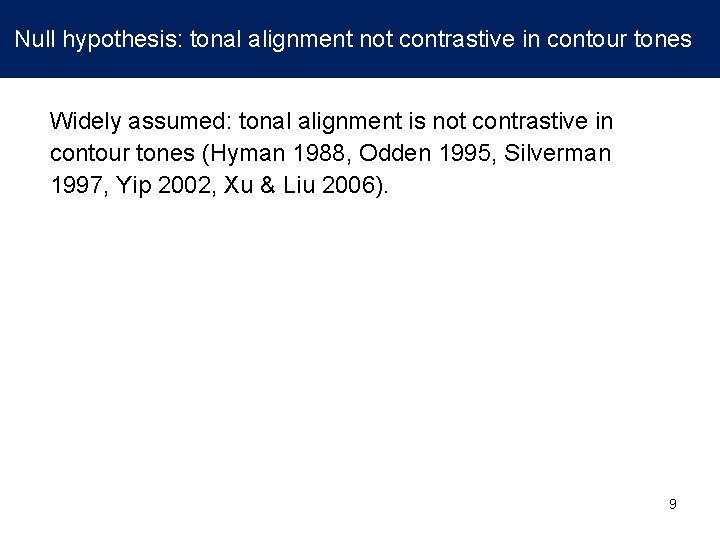

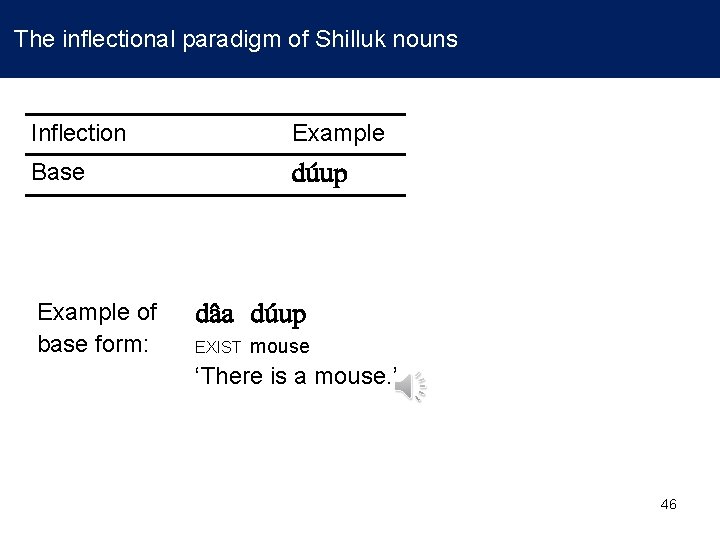

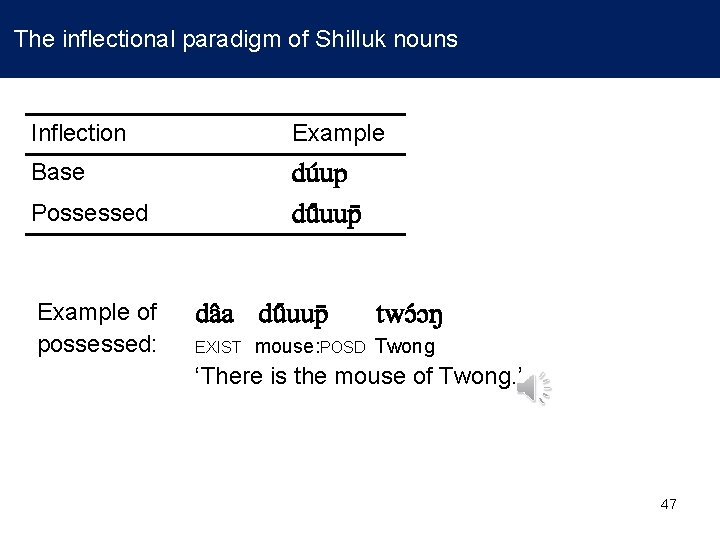

Null hypothesis: tonal alignment not contrastive in contour tones Widely assumed: tonal alignment is not contrastive in contour tones (Hyman 1988, Odden 1995, Silverman 1997, Yip 2002, Xu & Liu 2006). 9

![Null hypothesis tonal alignment not contrastive in contour tones It might be that in Null hypothesis: tonal alignment not contrastive in contour tones “[I]t might be that in](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/77463f6ab5e8eb948d4df04442387e2f/image-10.jpg)

Null hypothesis: tonal alignment not contrastive in contour tones “[I]t might be that in some languages pitch changes are timed relatively early in the syllable, and in other languages they are timed relatively late. Such control would only be phonetic, never phonological. ” [Odden 1995: 450] 10

![Null hypothesis tonal alignment not contrastive in contour tones There is no possible opposition Null hypothesis: tonal alignment not contrastive in contour tones “[T]here is no possible opposition](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/77463f6ab5e8eb948d4df04442387e2f/image-11.jpg)

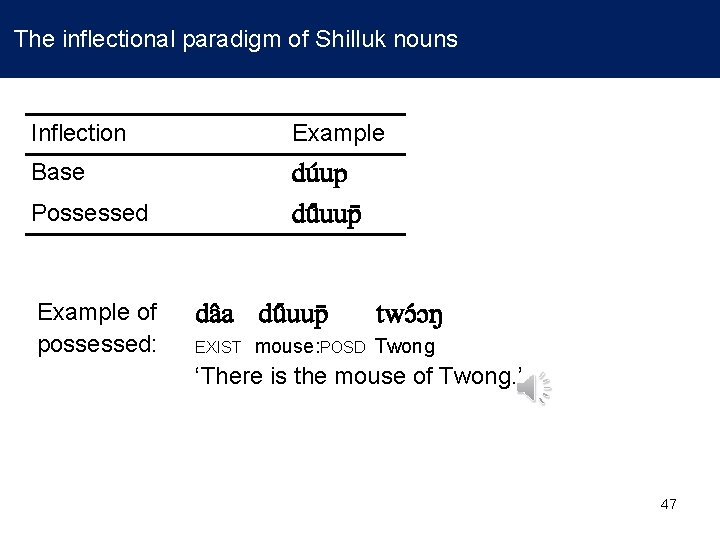

Null hypothesis: tonal alignment not contrastive in contour tones “[T]here is no possible opposition between two HL or two LH contours where the two tones are synchronized differently within the syllable. ” [Hyman 1988: 51] 11

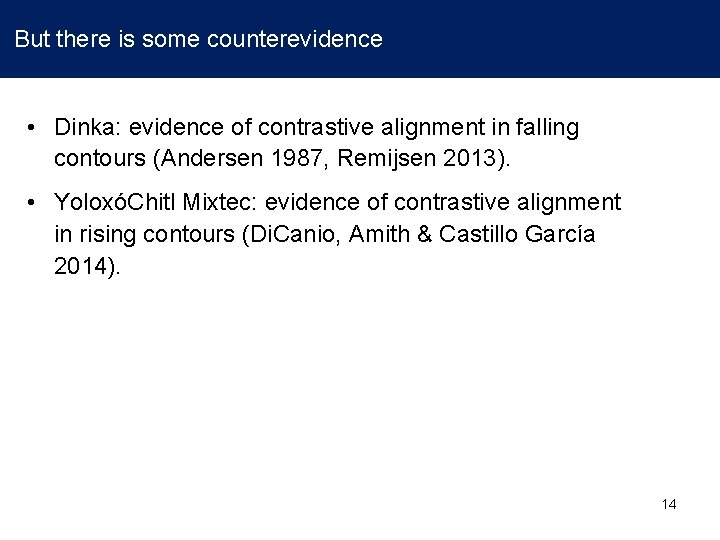

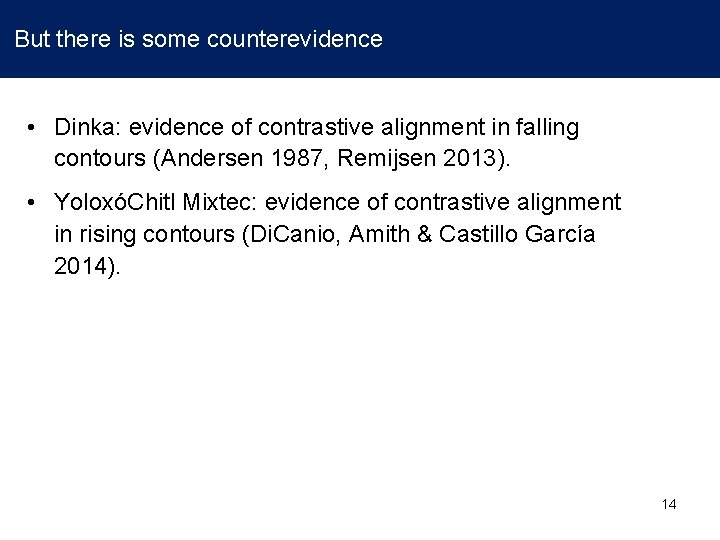

Null hypothesis: tonal alignment not contrastive in contour tones This configuration is assumed not to occur: Figure. Schematic representations of two falling contours distinguished by tonal alignment. 12

Null hypothesis: tonal alignment not contrastive in contour tones The null hypothesis makes good sense: • Production – F 0 changes are implemented slowly, because speed is low at turning points (Xu & Sun 2002) • Perception – when time domain is small, an F 0 change has to be greater, to be perceived as a pitch change (‘t Hart, Collier & Cohen 1990) • Typology – contour tones tend to be restricted to environments that offer extra time (Zhang 2001) 13

But there is some counterevidence • Dinka: evidence of contrastive alignment in falling contours (Andersen 1987, Remijsen 2013). • YoloxóChitl Mixtec: evidence of contrastive alignment in rising contours (Di. Canio, Amith & Castillo García 2014). 14

The next step • If we were to make the case that /e/ vs. /ɛ/ is contrastive in a given language, we would want to see: 1. Evidence of substantial and significant differences in F 1, F 2 in hypothesized (minimal) sets of these two vowels; 2. Evidence that /e/ is substantially and significantly different in F 1 and F 2 from /i/, and likewise /ɛ/ from /a/. 15

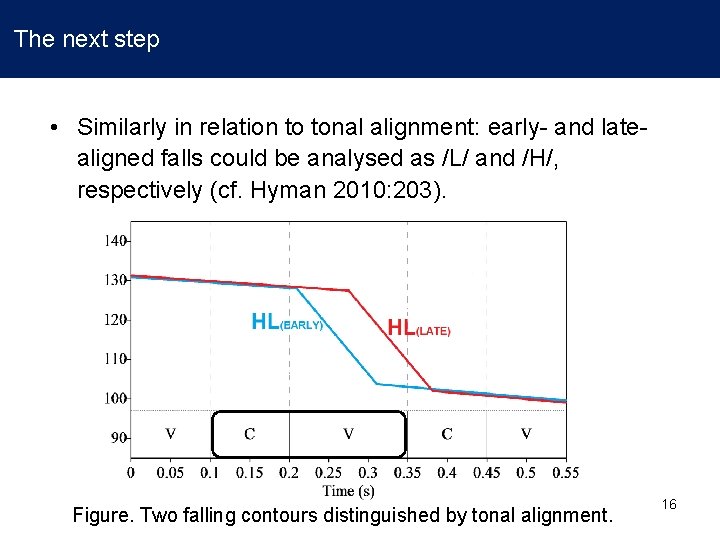

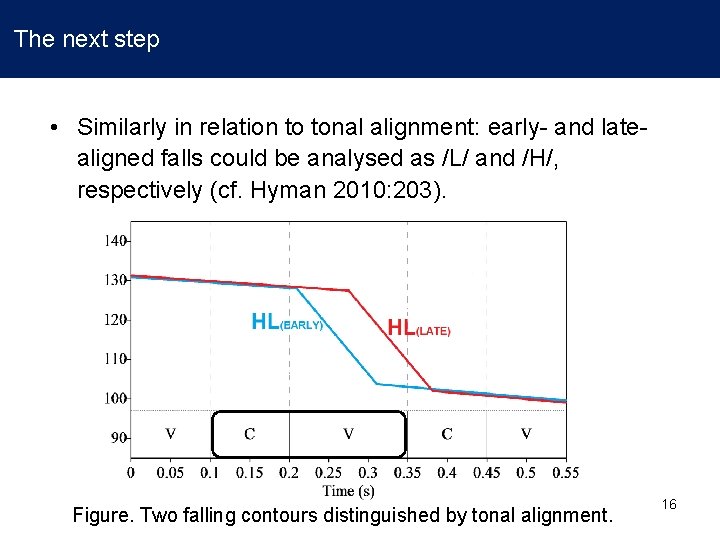

The next step • Similarly in relation to tonal alignment: early- and latealigned falls could be analysed as /L/ and /H/, respectively (cf. Hyman 2010: 203). Figure. Two falling contours distinguished by tonal alignment. 16

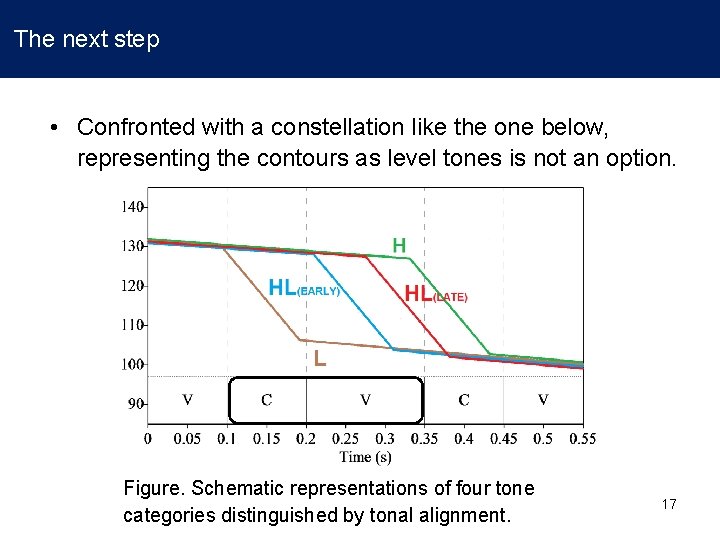

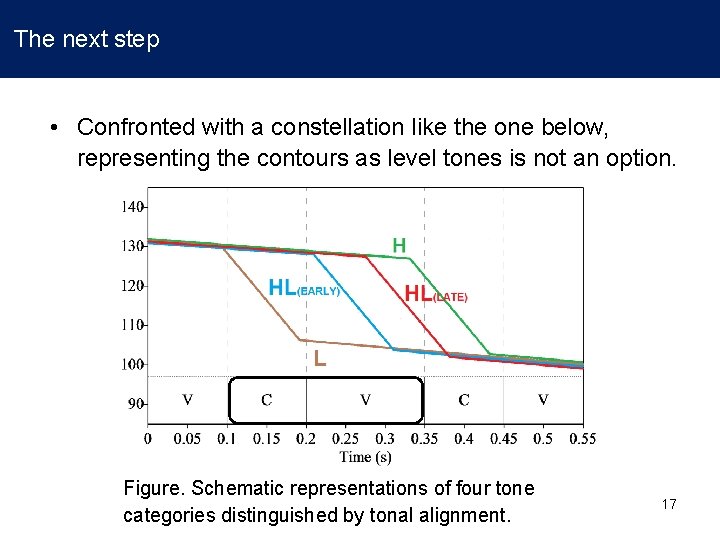

The next step • Confronted with a constellation like the one below, representing the contours as level tones is not an option. Figure. Schematic representations of four tone categories distinguished by tonal alignment. 17

The next step • This study: report on a production study on such a four-way configuration in phonetic tonal alignment. Question: is tonal alignment contrastive in falling contour tone categories? Null hypothesis: no Alternative hypothesis: yes 18

Methods / Design • Manipulation of the factor Tone, with factor levels: - Low - Early High Fall - Late High Fall - High 19

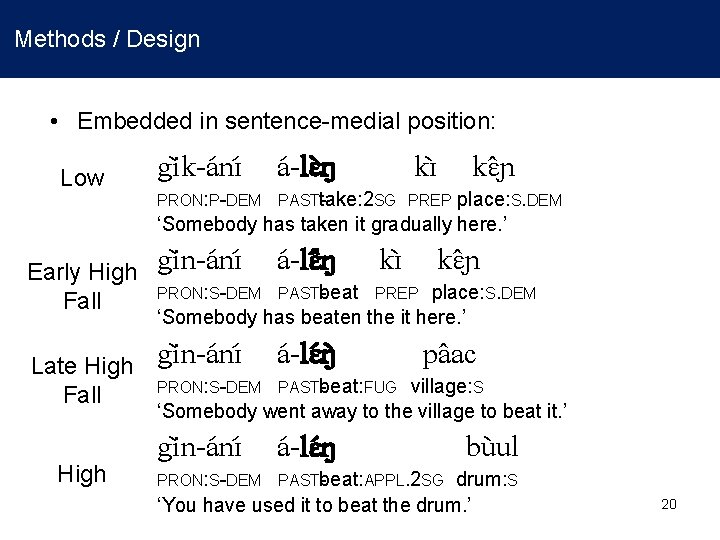

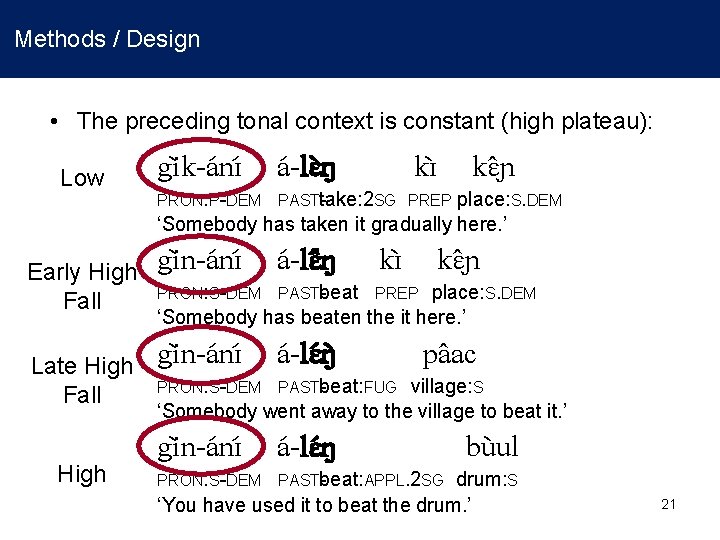

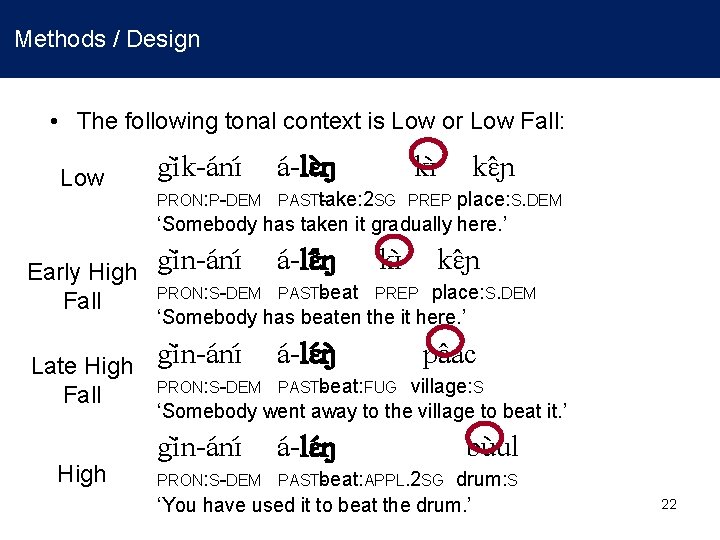

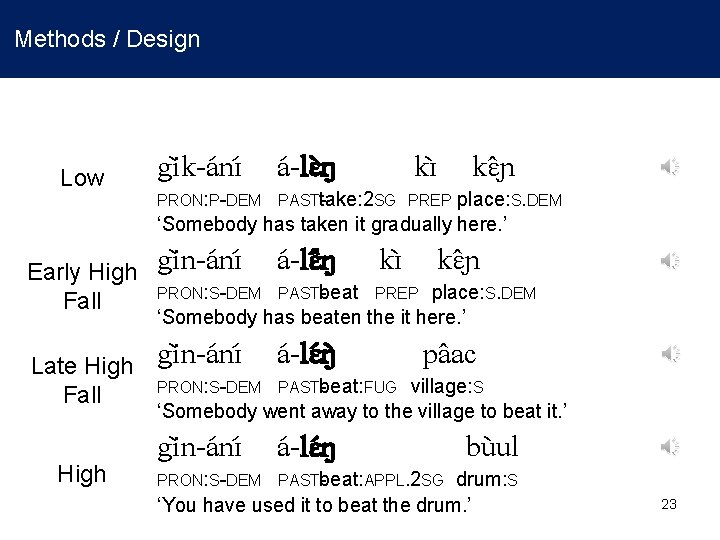

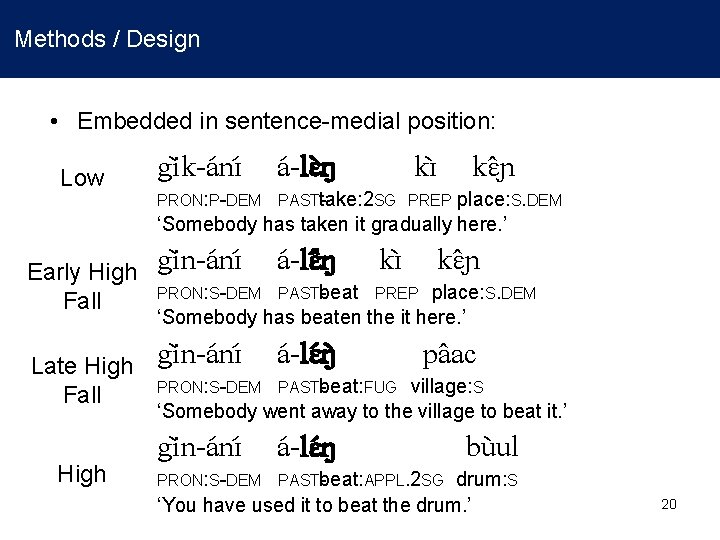

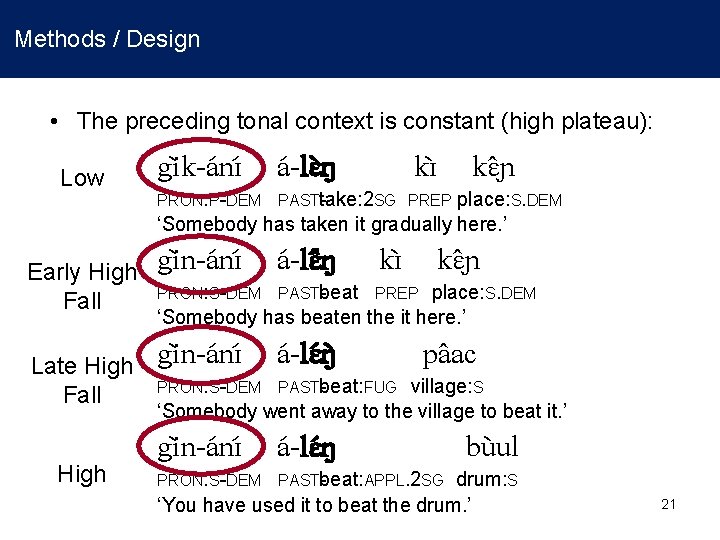

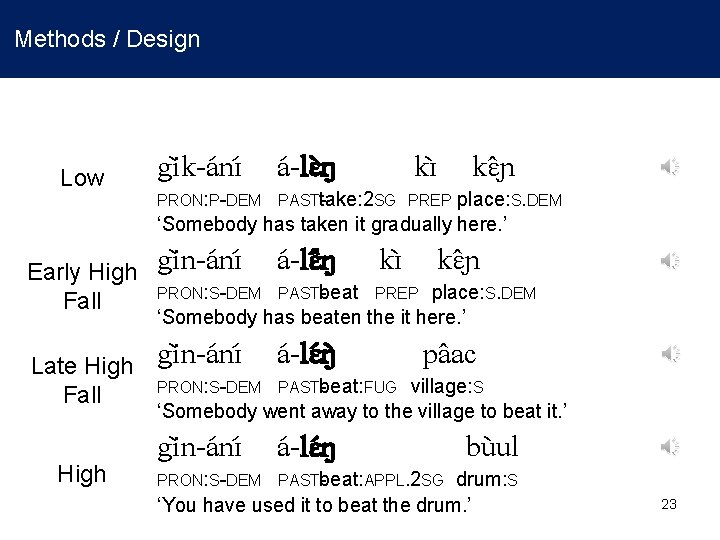

Methods / Design • Embedded in sentence-medial position: Low Early High Fall Late High Fall High gi k-a nɪ a -lɛ ŋ kɪ kɛ ɲ PRON: P-DEM PASTt-ake: 2 SG PREP gi n-a nɪ a -lɛ ŋ kɪ PRON: S-DEM PASTb - eat PREP gi n-a nɪ a -lɛ ŋ PRON: S-DEM PASTb - eat: FUG gi n-a nɪ a -lɛ ŋ PRON: S-DEM PASTb - eat: APPL. 2 SG place: S. DEM ‘Somebody has taken it gradually here. ’ kɛ ɲ place: S. DEM ‘Somebody has beaten the it here. ’ pa ac village: S ‘Somebody went away to the village to beat it. ’ bu ul drum: S ‘You have used it to beat the drum. ’ 20

Methods / Design • The preceding tonal context is constant (high plateau): Low Early High Fall Late High Fall High gi k-a nɪ a -lɛ ŋ kɪ kɛ ɲ PRON: P-DEM PASTt-ake: 2 SG PREP gi n-a nɪ a -lɛ ŋ kɪ PRON: S-DEM PASTb - eat PREP gi n-a nɪ a -lɛ ŋ PRON: S-DEM PASTb - eat: FUG gi n-a nɪ a -lɛ ŋ PRON: S-DEM PASTb - eat: APPL. 2 SG place: S. DEM ‘Somebody has taken it gradually here. ’ kɛ ɲ place: S. DEM ‘Somebody has beaten the it here. ’ pa ac village: S ‘Somebody went away to the village to beat it. ’ bu ul drum: S ‘You have used it to beat the drum. ’ 21

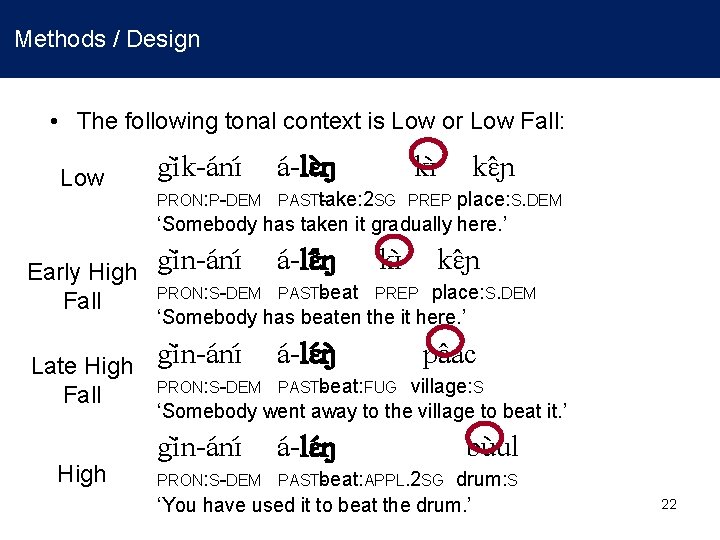

Methods / Design • The following tonal context is Low or Low Fall: Low Early High Fall Late High Fall High gi k-a nɪ a -lɛ ŋ kɪ kɛ ɲ PRON: P-DEM PASTt-ake: 2 SG PREP gi n-a nɪ a -lɛ ŋ kɪ PRON: S-DEM PASTb - eat PREP gi n-a nɪ a -lɛ ŋ PRON: S-DEM PASTb - eat: FUG gi n-a nɪ a -lɛ ŋ PRON: S-DEM PASTb - eat: APPL. 2 SG place: S. DEM ‘Somebody has taken it gradually here. ’ kɛ ɲ place: S. DEM ‘Somebody has beaten the it here. ’ pa ac village: S ‘Somebody went away to the village to beat it. ’ bu ul drum: S ‘You have used it to beat the drum. ’ 22

Methods / Design Low Early High Fall Late High Fall High gi k-a nɪ a -lɛ ŋ kɪ kɛ ɲ PRON: P-DEM PASTt-ake: 2 SG PREP gi n-a nɪ a -lɛ ŋ kɪ PRON: S-DEM PASTb - eat PREP gi n-a nɪ a -lɛ ŋ PRON: S-DEM PASTb - eat: FUG gi n-a nɪ a -lɛ ŋ PRON: S-DEM PASTb - eat: APPL. 2 SG place: S. DEM ‘Somebody has taken it gradually here. ’ kɛ ɲ place: S. DEM ‘Somebody has beaten the it here. ’ pa ac village: S ‘Somebody went away to the village to beat it. ’ bu ul drum: S ‘You have used it to beat the drum. ’ 23

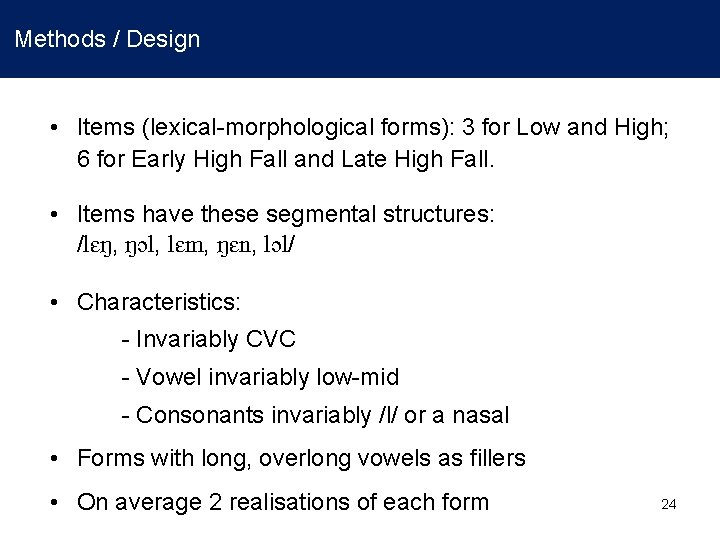

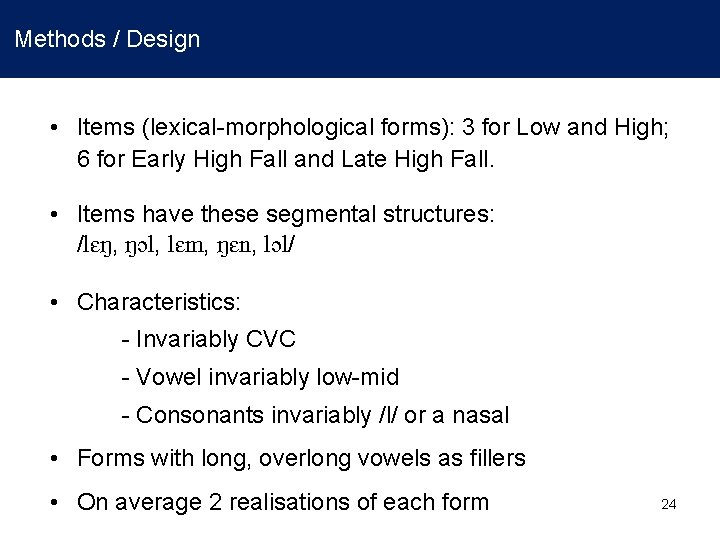

Methods / Design • Items (lexical-morphological forms): 3 for Low and High; 6 for Early High Fall and Late High Fall. • Items have these segmental structures: /lɛŋ, ŋɔl, lɛm, ŋɛn, lɔl/ • Characteristics: - Invariably CVC - Vowel invariably low-mid - Consonants invariably /l/ or a nasal • Forms with long, overlong vowels as fillers • On average 2 realisations of each form 24

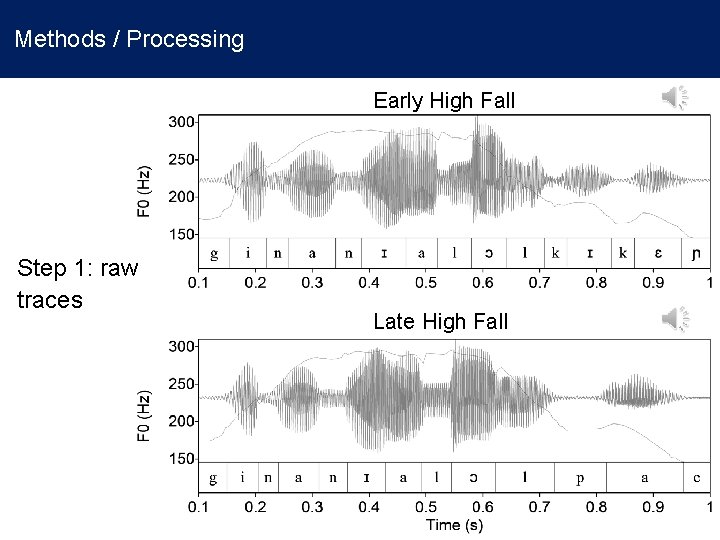

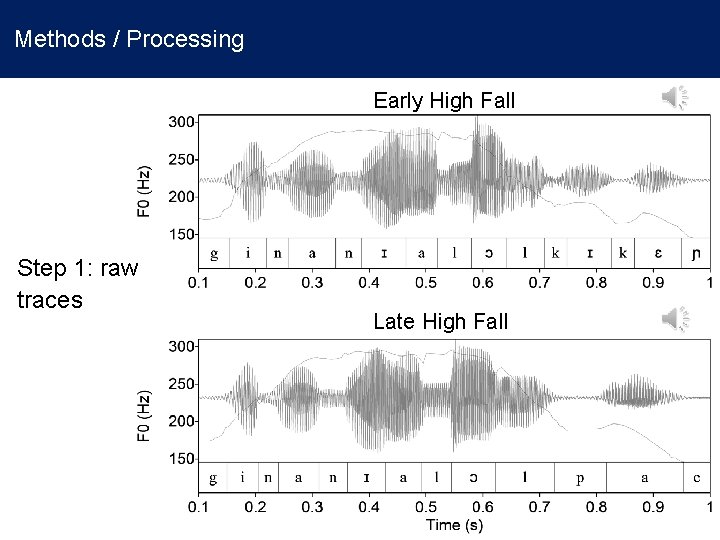

Methods / Processing Early High Fall Step 1: raw traces Late High Fall

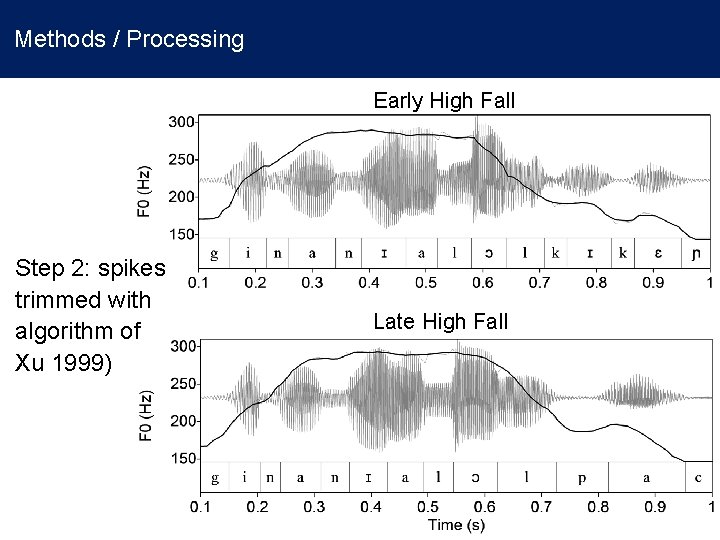

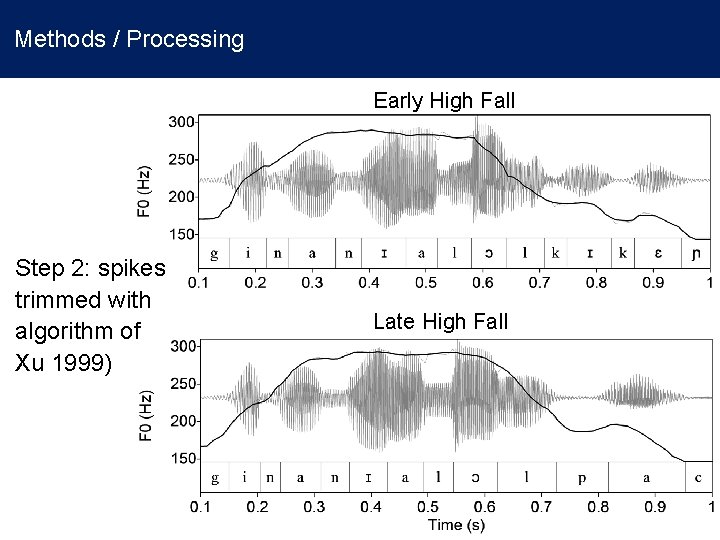

Methods / Processing Early High Fall Step 2: spikes trimmed with algorithm of Xu 1999) Late High Fall

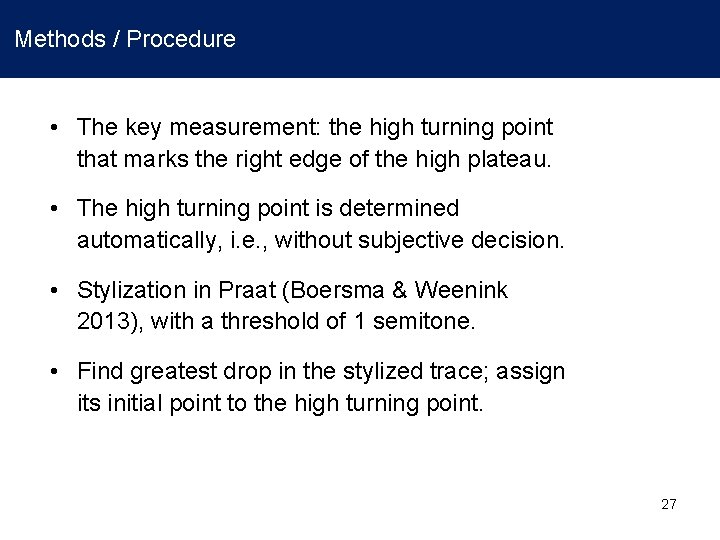

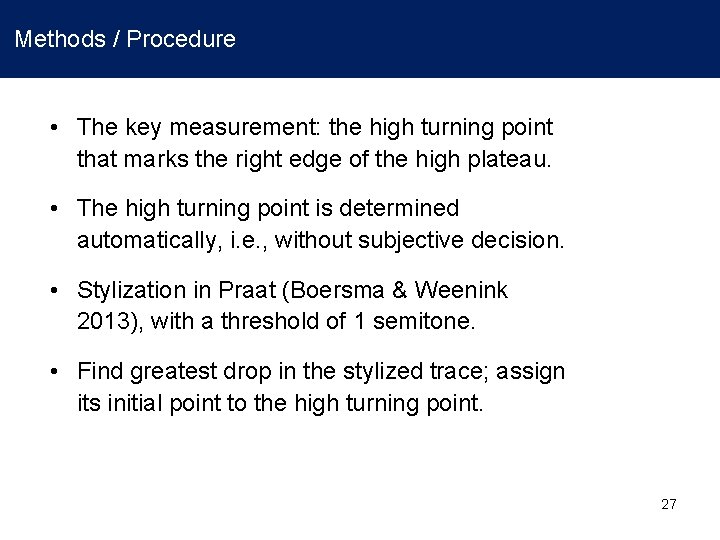

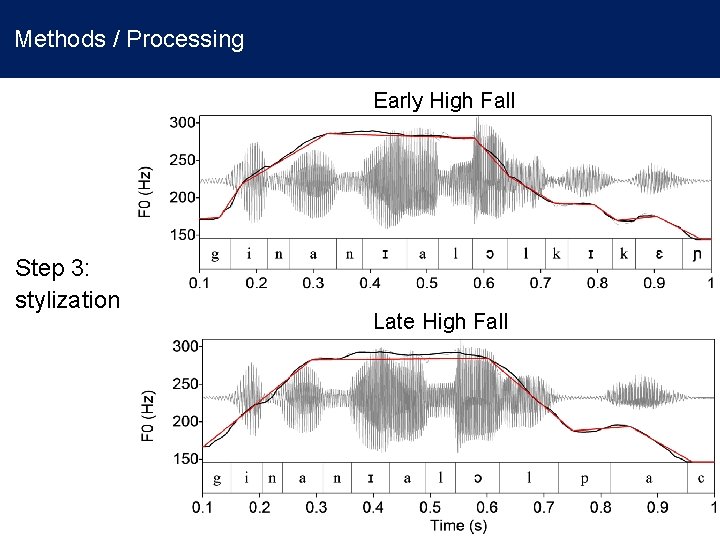

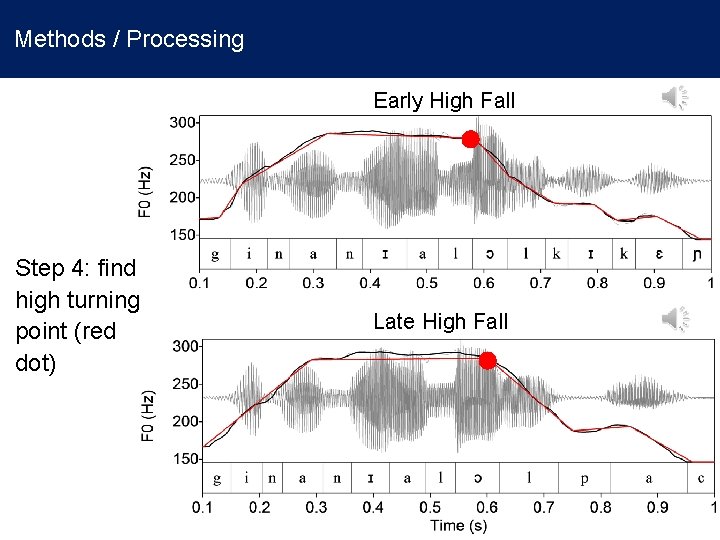

Methods / Procedure • The key measurement: the high turning point that marks the right edge of the high plateau. • The high turning point is determined automatically, i. e. , without subjective decision. • Stylization in Praat (Boersma & Weenink 2013), with a threshold of 1 semitone. • Find greatest drop in the stylized trace; assign its initial point to the high turning point. 27

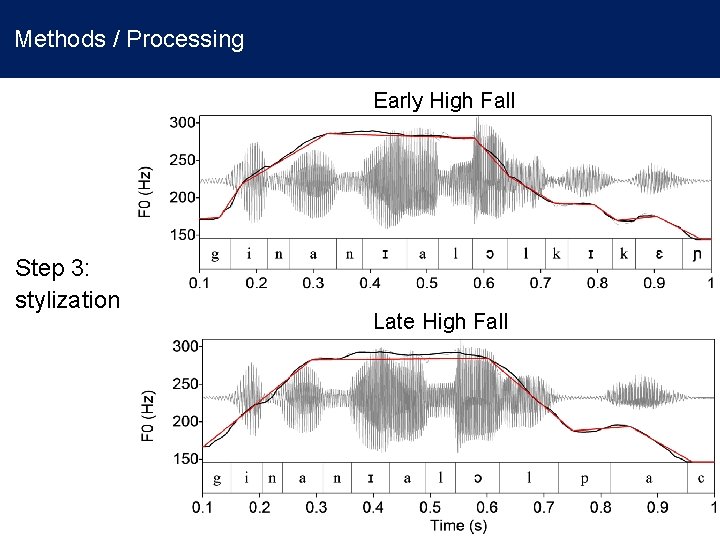

Methods / Processing Early High Fall Step 3: stylization Late High Fall

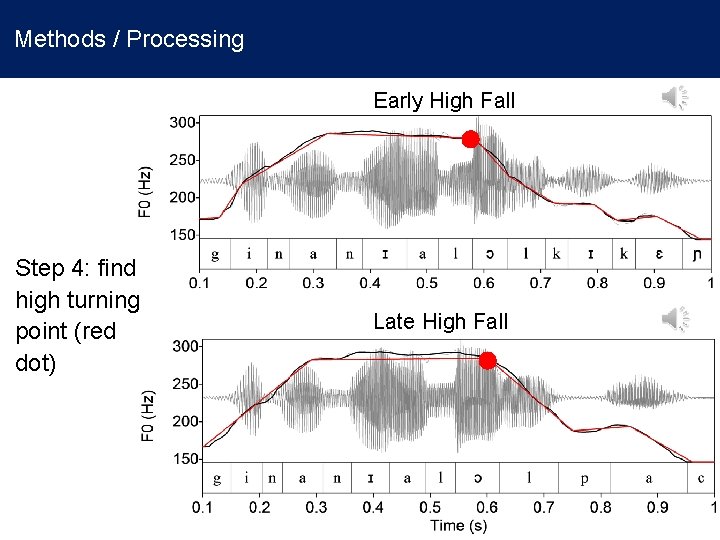

Methods / Processing Early High Fall Step 4: find high turning point (red dot) Late High Fall

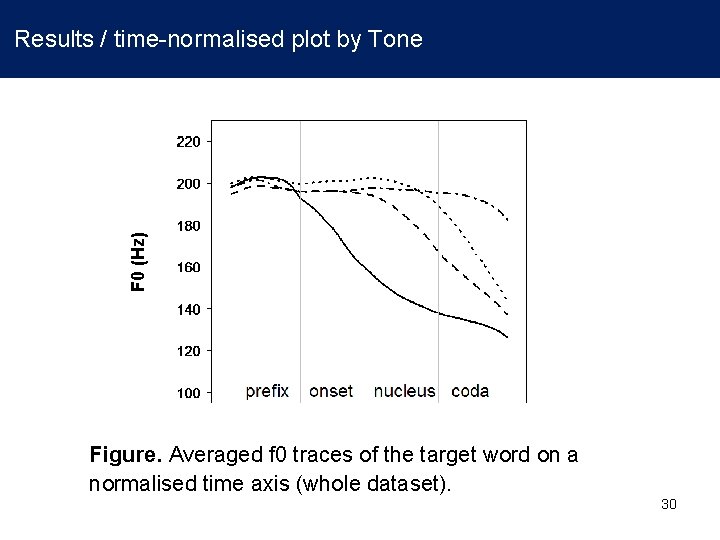

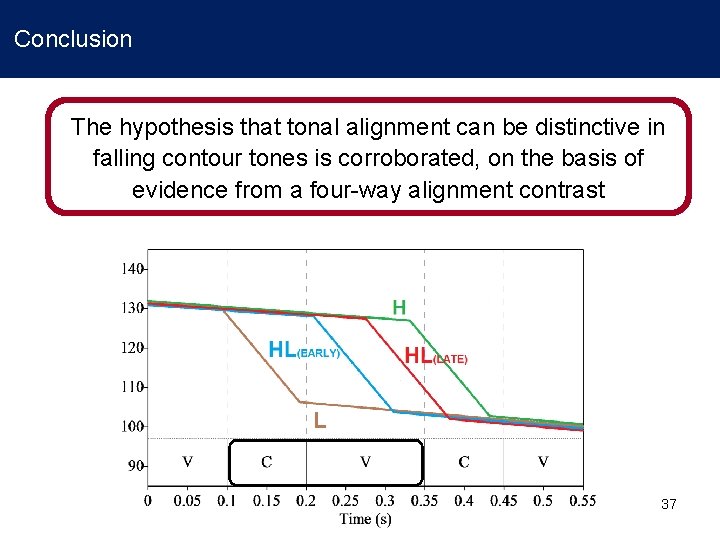

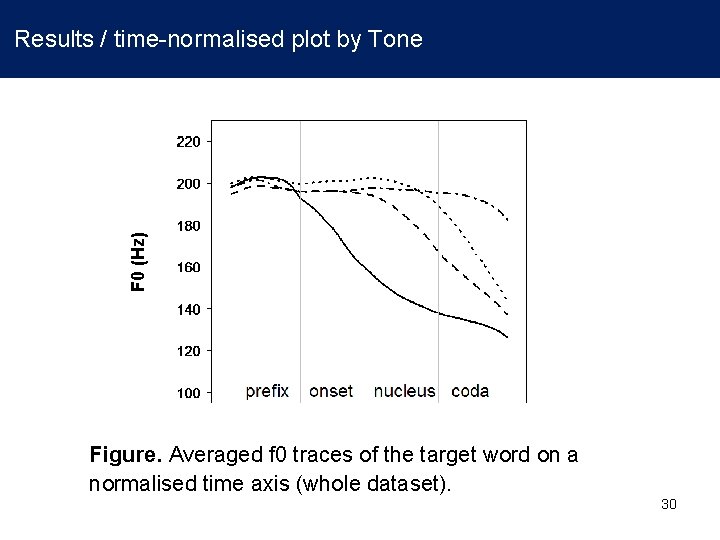

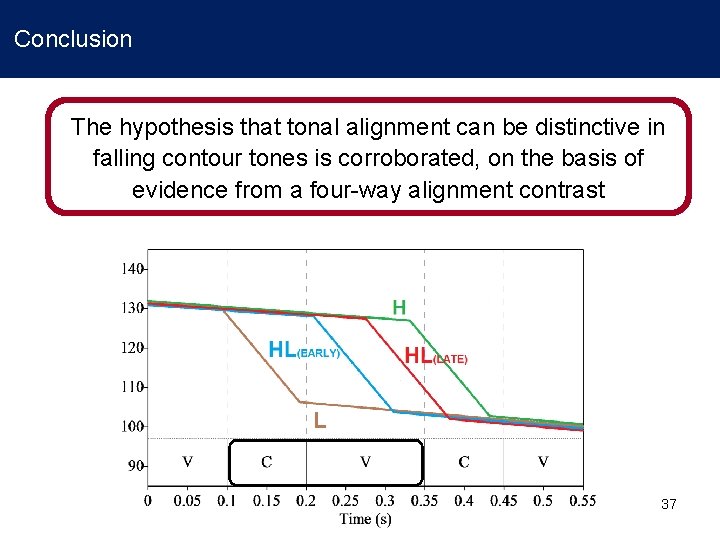

F 0 (Hz) Results / time-normalised plot by Tone Figure. Averaged f 0 traces of the target word on a normalised time axis (whole dataset). 30

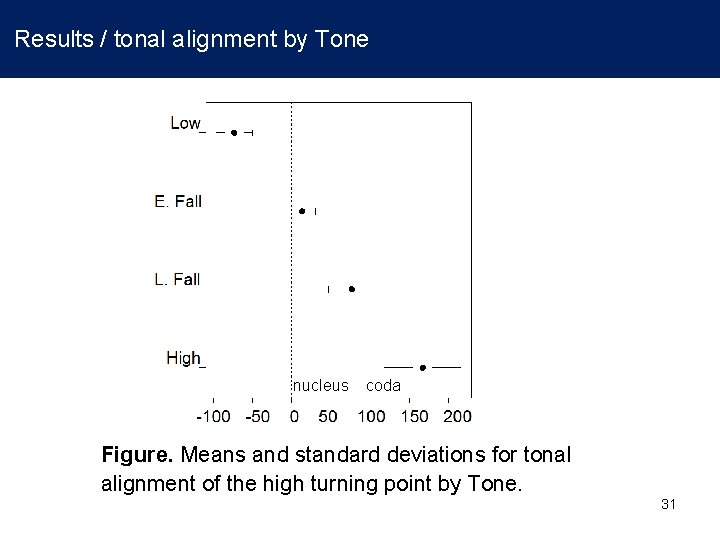

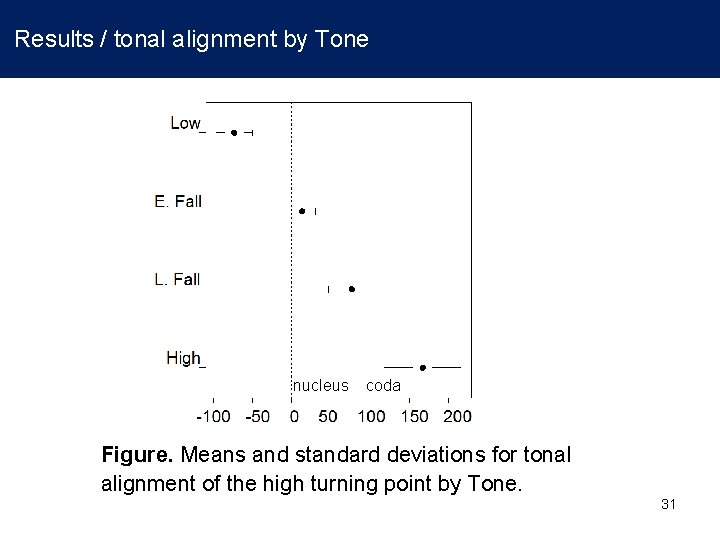

Results / tonal alignment by Tone nucleus coda Figure. Means and standard deviations for tonal alignment of the high turning point by Tone. 31

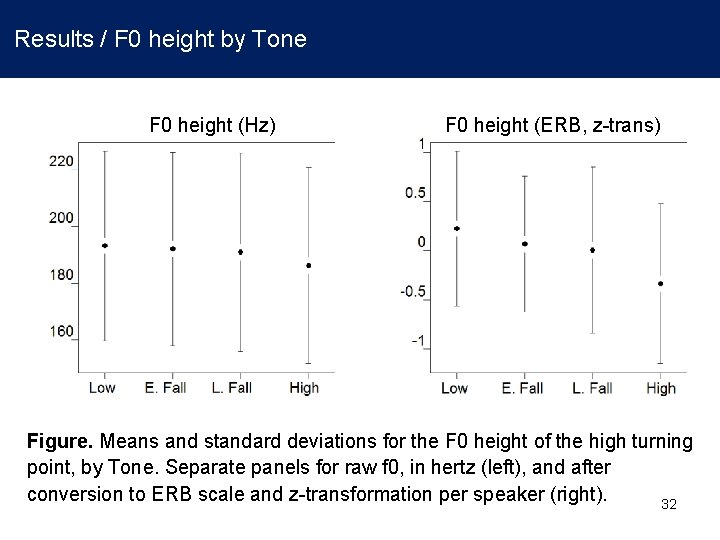

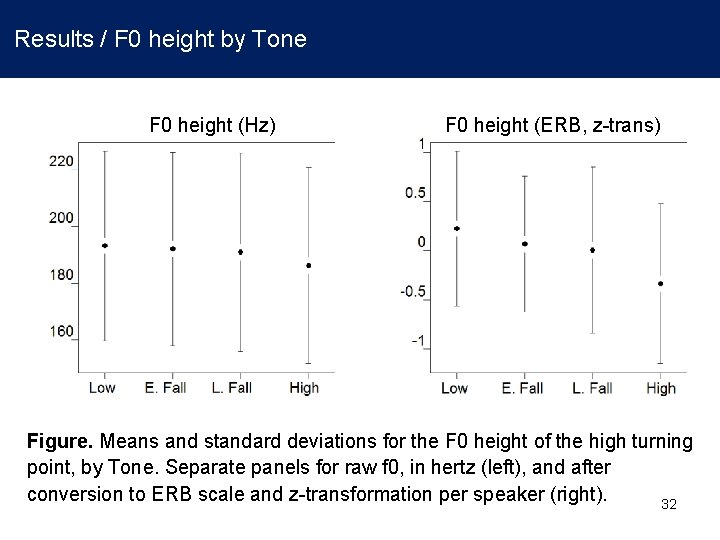

Results / F 0 height by Tone F 0 height (Hz) F 0 height (ERB, z-trans) Figure. Means and standard deviations for the F 0 height of the high turning point, by Tone. Separate panels for raw f 0, in hertz (left), and after conversion to ERB scale and z-transformation per speaker (right). 32

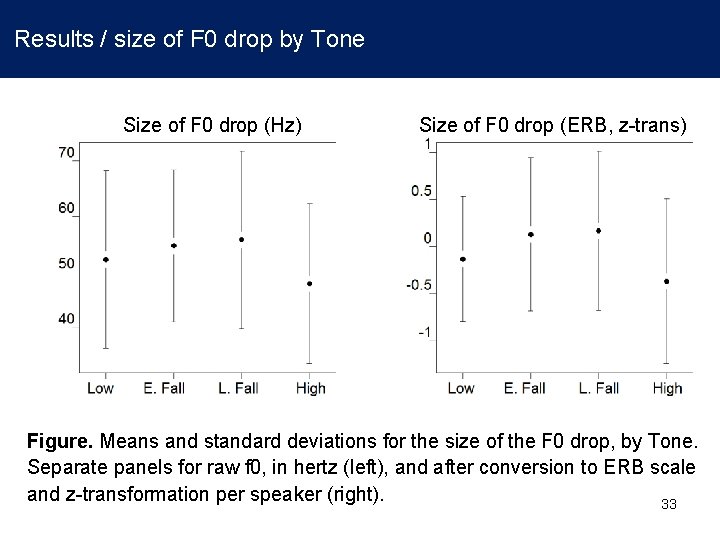

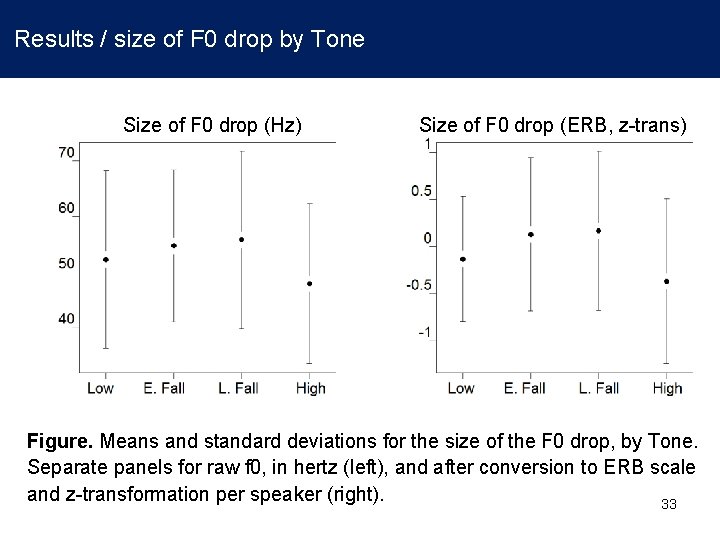

Results / size of F 0 drop by Tone Size of F 0 drop (Hz) Size of F 0 drop (ERB, z-trans) Figure. Means and standard deviations for the size of the F 0 drop, by Tone. Separate panels for raw f 0, in hertz (left), and after conversion to ERB scale and z-transformation per speaker (right). 33

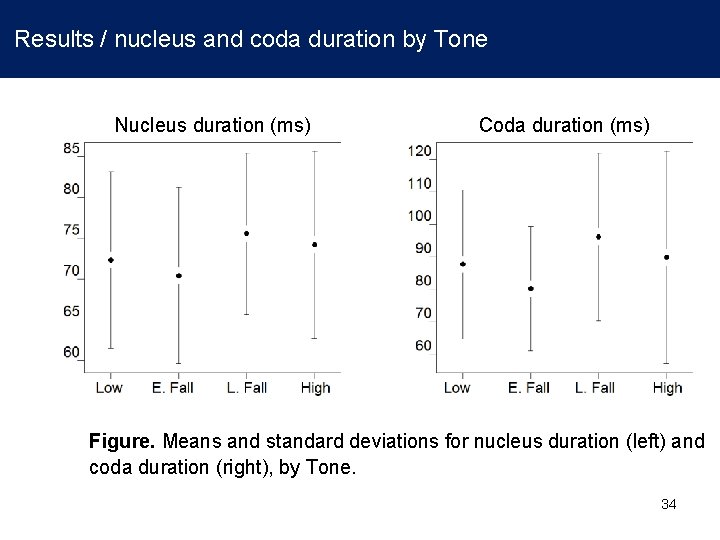

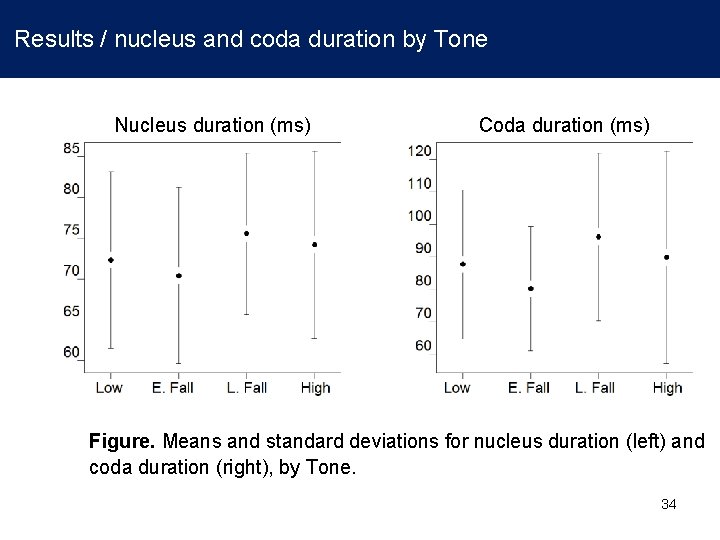

Results / nucleus and coda duration by Tone Nucleus duration (ms) Coda duration (ms) Figure. Means and standard deviations for nucleus duration (left) and coda duration (right), by Tone. 34

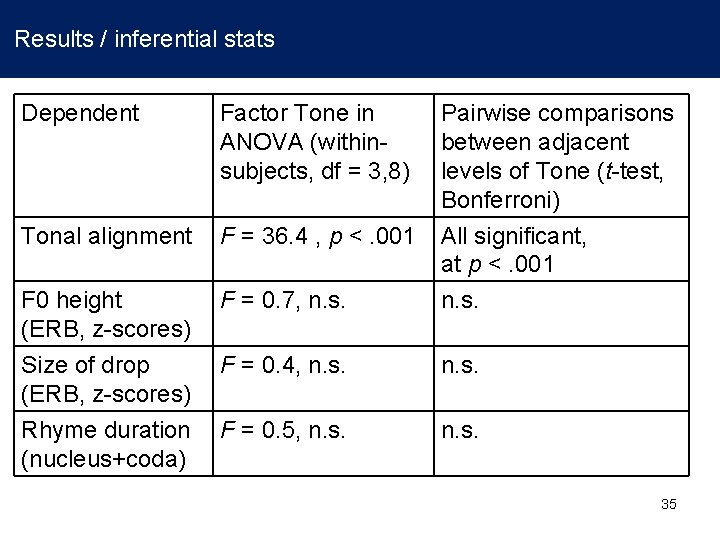

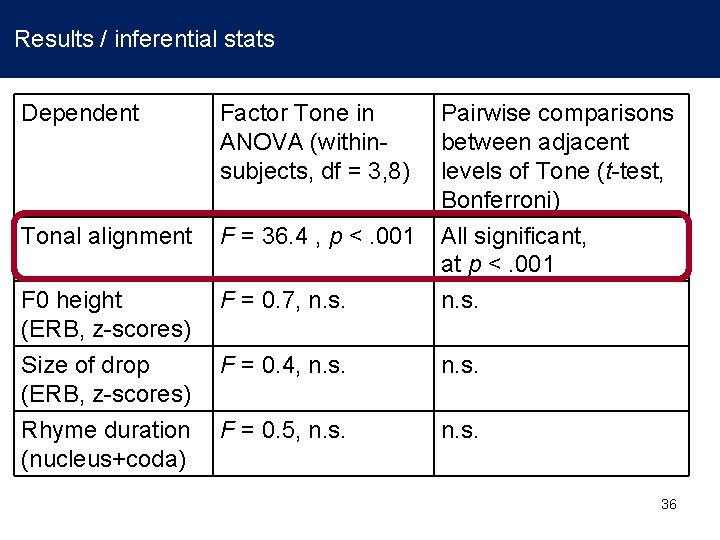

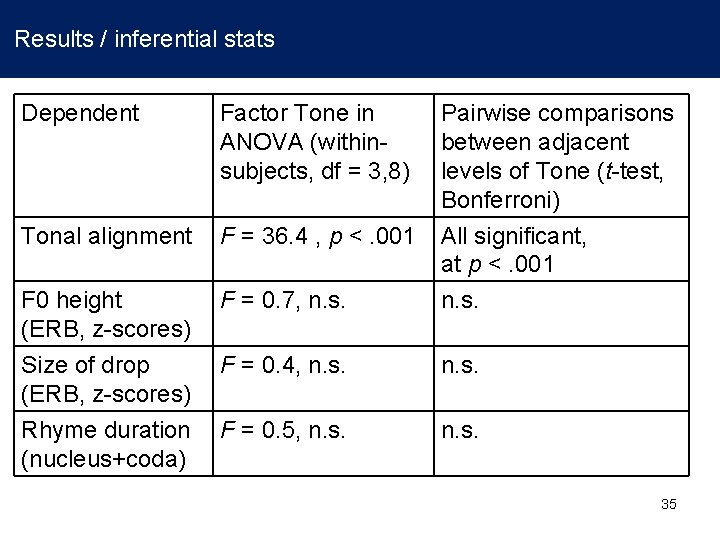

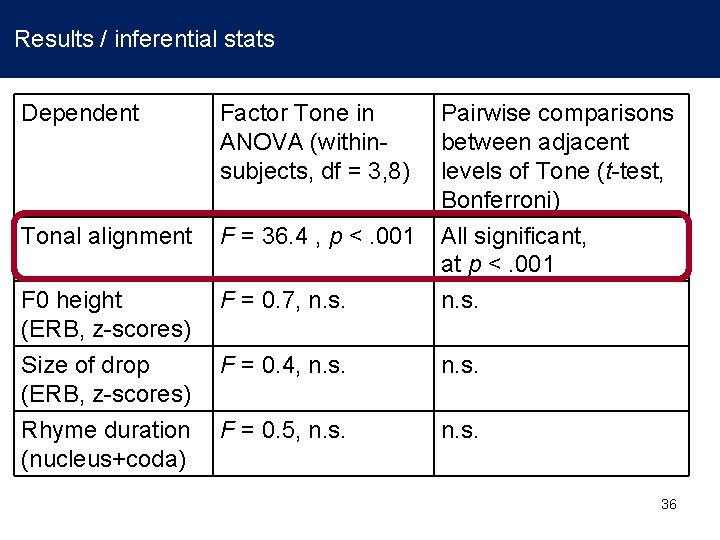

Results / inferential stats Dependent Factor Tone in ANOVA (withinsubjects, df = 3, 8) Pairwise comparisons between adjacent levels of Tone (t-test, Bonferroni) All significant, at p <. 001 Tonal alignment F = 36. 4 , p <. 001 F 0 height (ERB, z-scores) Size of drop (ERB, z-scores) Rhyme duration (nucleus+coda) F = 0. 7, n. s. F = 0. 4, n. s. F = 0. 5, n. s. 35

Results / inferential stats Dependent Factor Tone in ANOVA (withinsubjects, df = 3, 8) Pairwise comparisons between adjacent levels of Tone (t-test, Bonferroni) All significant, at p <. 001 Tonal alignment F = 36. 4 , p <. 001 F 0 height (ERB, z-scores) Size of drop (ERB, z-scores) Rhyme duration (nucleus+coda) F = 0. 7, n. s. F = 0. 4, n. s. F = 0. 5, n. s. 36

Conclusion The hypothesis that tonal alignment can be distinctive in falling contour tones is corroborated, on the basis of evidence from a four-way alignment contrast 37

The development of falling contour tones out of affixes

Evolutionary Phonology (Blevins 2004) Contrasts that are difficult to produce or perceive are more likely to be maintained if they mark morphological contrasts (see also Blevins & Wedel 2009, Baerman 2011). 39

Evolutionary Phonology (Blevins 2004) Contrasts that are difficult to produce or perceive are more likely to be maintained if they mark morphological contrasts (see also Blevins & Wedel 2009, Baerman 2011). Example: compensatory lengthening in Dinka (Andersen 1987, 1990) *CVVC-V > CVVVC 40

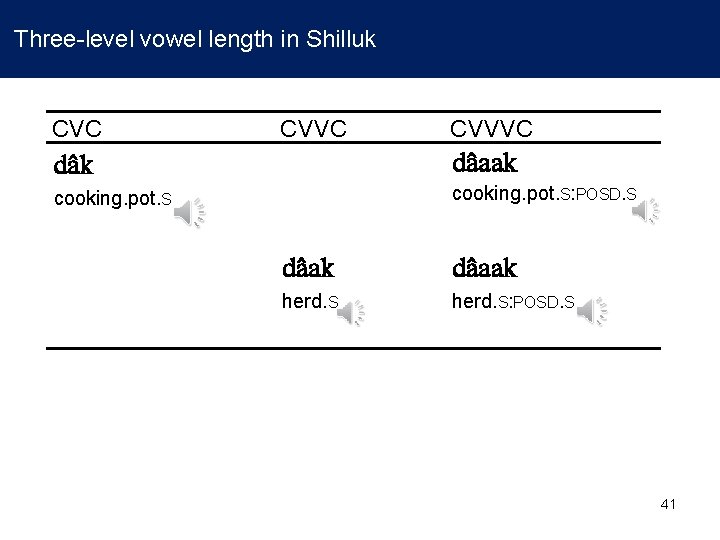

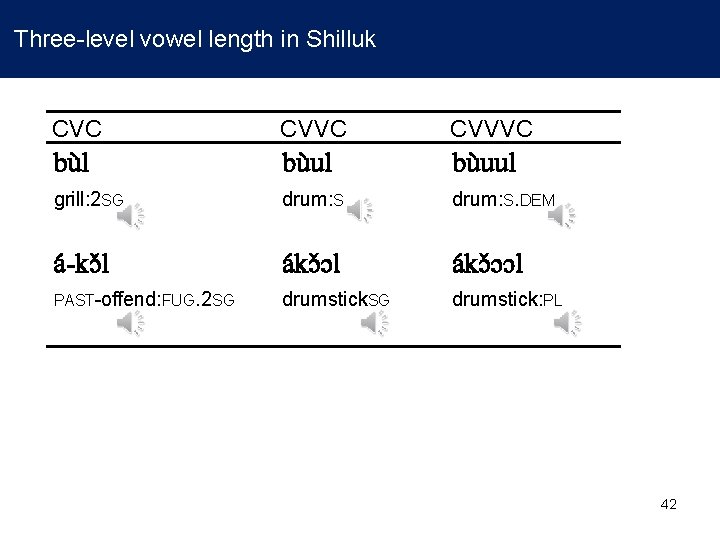

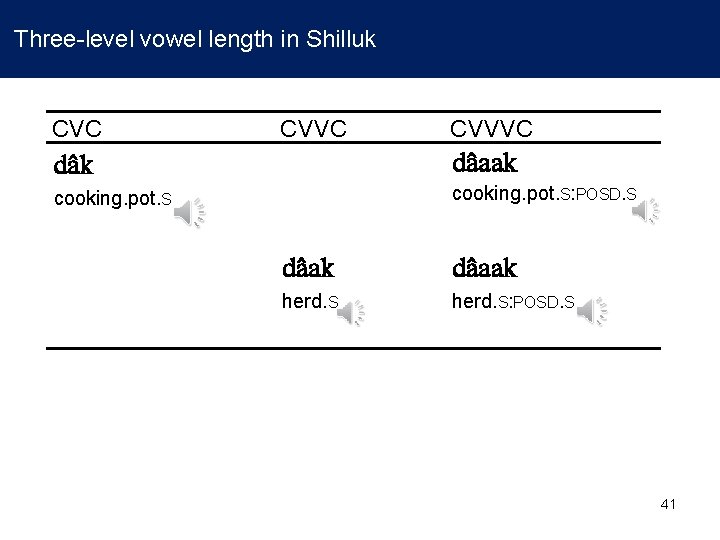

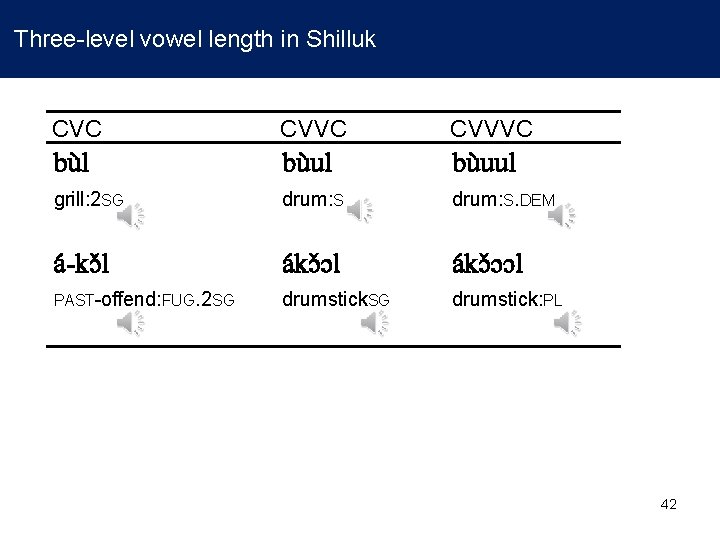

Three-level vowel length in Shilluk CVC CVVC da k CVVVC da aak cooking. pot. S: POSD. S cooking. pot. S da ak da aak herd. S: POSD. S 41

Three-level vowel length in Shilluk CVC CVVVC grill: 2 SG drum: S. DEM a -kɔ l a kɔ ɔɔl PAST-offend: FUG. 2 SG drumstick: PL bu l bu uul 42

Now on to tones 43

Now on to tones… and to head-marking noun morphology (cf. Creissels 2009) 44

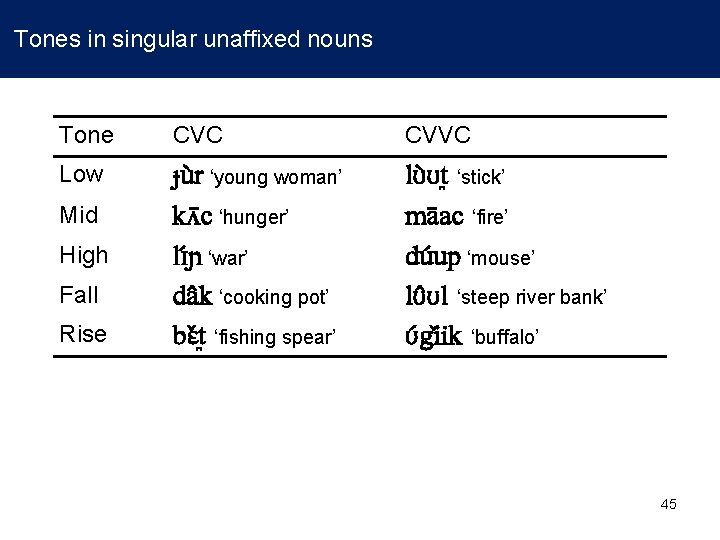

Tones in singular unaffixed nouns Tone CVC CVVC Low ɟu r ‘young woman’ kʌ c ‘hunger’ lɪ ɲ ‘war’ da k ‘cooking pot’ bɛ t ‘fishing spear’ lʊ ʊt ‘stick’ ma ac ‘fire’ du up ‘mouse’ lʊ ʊl ‘steep river bank’ ʊ gi ik ‘buffalo’ Mid High Fall Rise 45

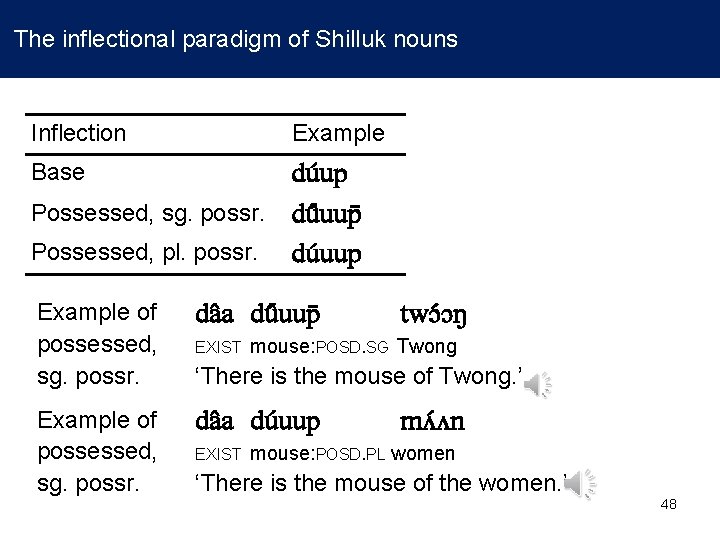

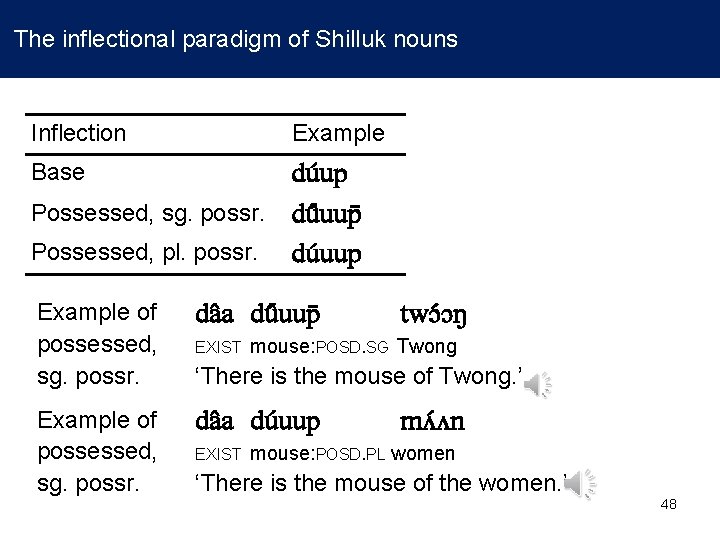

The inflectional paradigm of Shilluk nouns Inflection Example Base du up Example of base form: da a du up EXIST mouse ‘There is a mouse. ’ 46

The inflectional paradigm of Shilluk nouns Inflection Example Base du up du uup Possessed Example of possessed: da a du uup EXIST twɔ ɔŋ mouse: POSD Twong ‘There is the mouse of Twong. ’ 47

The inflectional paradigm of Shilluk nouns Inflection Example du up Possessed, sg. possr. du uup Possessed, pl. possr. du uup Base Example of possessed, sg. possr. da a du uup EXIST twɔ ɔŋ mouse: POSD. SG Twong ‘There is the mouse of Twong. ’ EXIST mʌ ʌn mouse: POSD. PL women ‘There is the mouse of the women. ’ 48

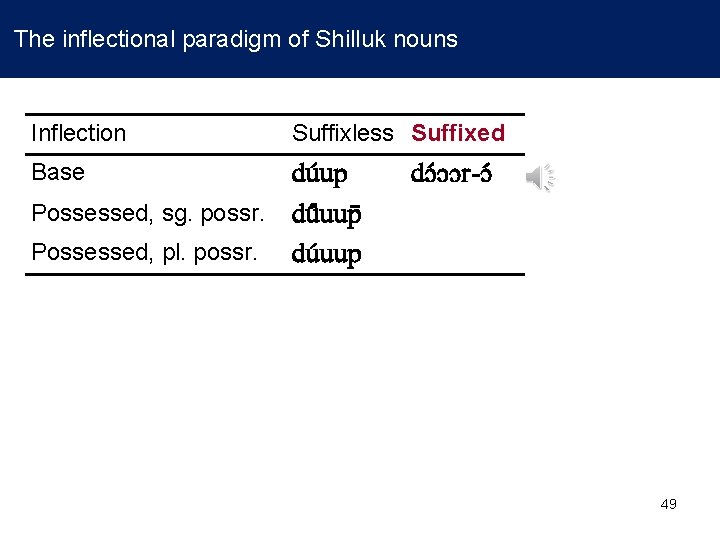

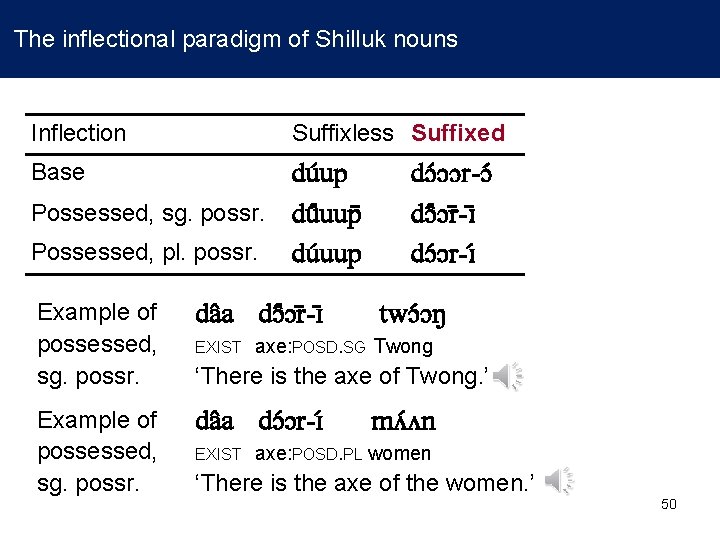

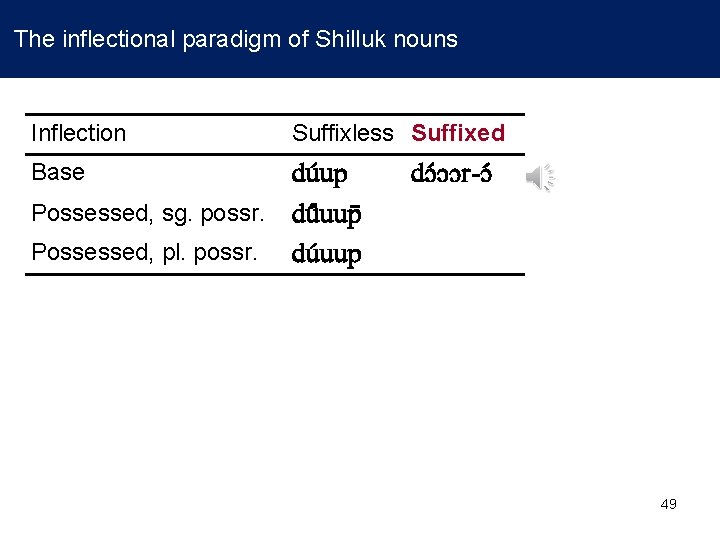

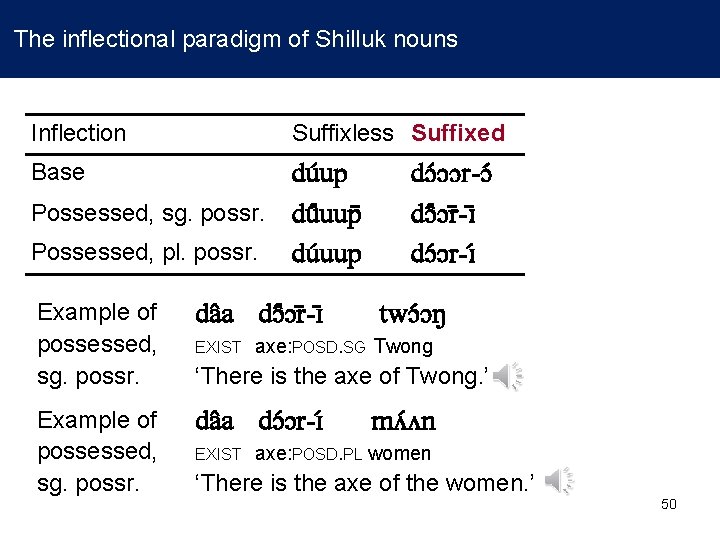

The inflectional paradigm of Shilluk nouns Inflection Suffixless Suffixed du up Possessed, sg. possr. du uup Possessed, pl. possr. du uup Base dɔ ɔɔr-ɔ 49

The inflectional paradigm of Shilluk nouns Inflection Suffixless Suffixed du up Possessed, sg. possr. du uup Possessed, pl. possr. du uup Base Example of possessed, sg. possr. da a dɔ ɔr -ɪ Example of possessed, sg. possr. da a dɔ ɔr-ɪ EXIST dɔ ɔɔr-ɔ dɔ ɔr -ɪ dɔ ɔr-ɪ twɔ ɔŋ axe: POSD. SG Twong ‘There is the axe of Twong. ’ EXIST mʌ ʌn axe: POSD. PL women ‘There is the axe of the women. ’ 50

The inflectional paradigm of Shilluk nouns Inflection Example Base du up du uum Construct state Example of construct state: da a du uum dwɔ ɔŋ EXIST mouse: CS big. S ‘There is a big mouse. ’ 51

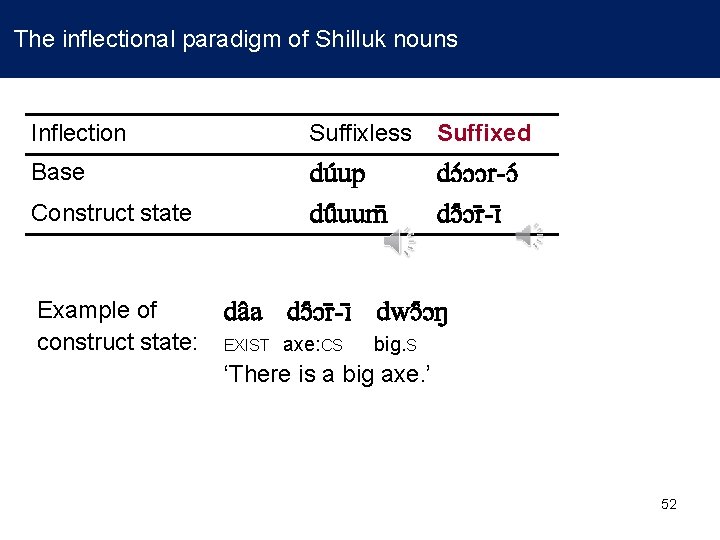

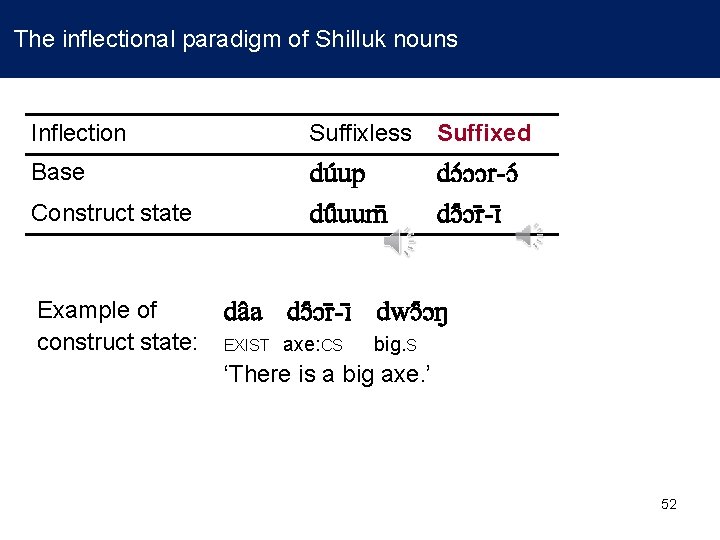

The inflectional paradigm of Shilluk nouns Inflection Suffixless Suffixed Base du up du uum dɔ ɔɔr-ɔ dɔ ɔr -ɪ Construct state Example of construct state: da a dɔ ɔr -ɪ dwɔ ɔŋ EXIST axe: CS big. S ‘There is a big axe. ’ 52

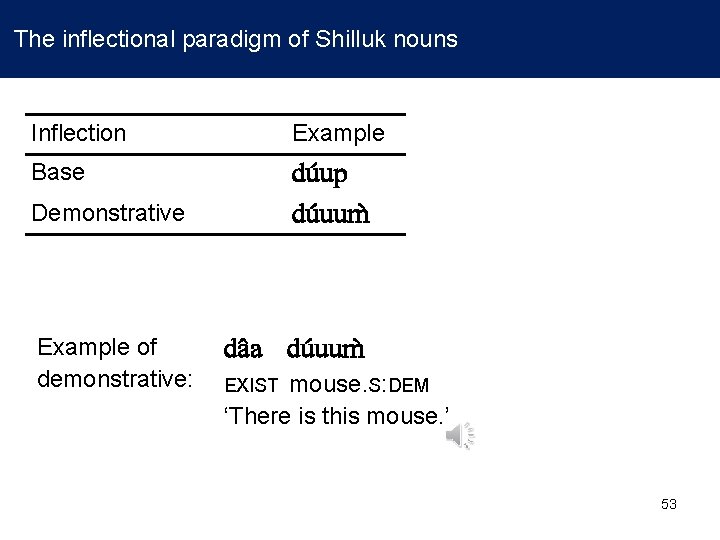

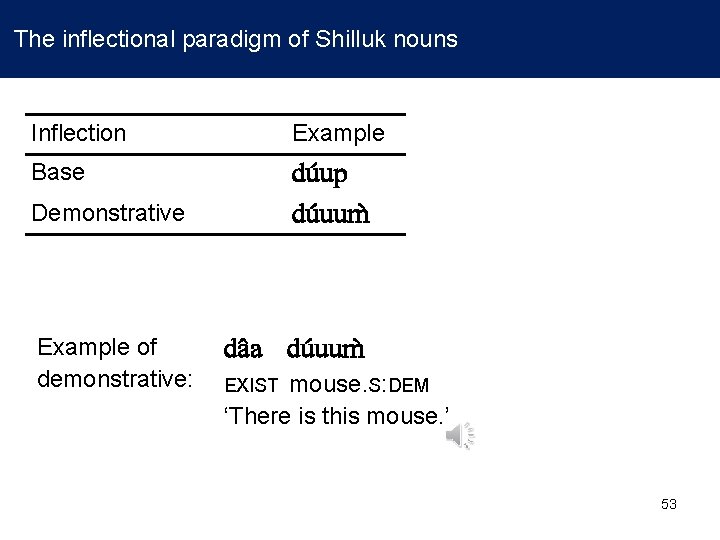

The inflectional paradigm of Shilluk nouns Inflection Example Base du up du uum Demonstrative Example of demonstrative: da a du uum mouse. S: DEM ‘There is this mouse. ’ EXIST 53

The inflectional paradigm of Shilluk nouns Inflection Suffixless Suffixed Base du up du uum Demonstrative Example of demonstrative: dɔ ɔɔr-ɔ dɔ ɔr-ɪ da a dɔ ɔr-ɪ EXIST axe-DEM ‘There is this axe. ’ 54

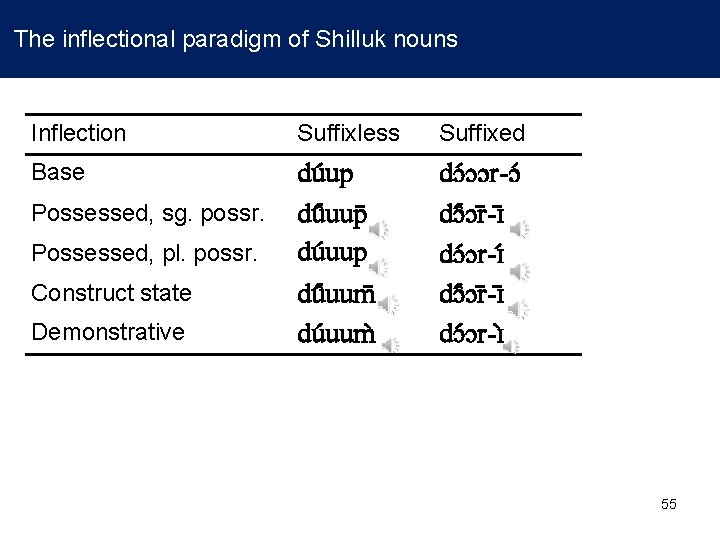

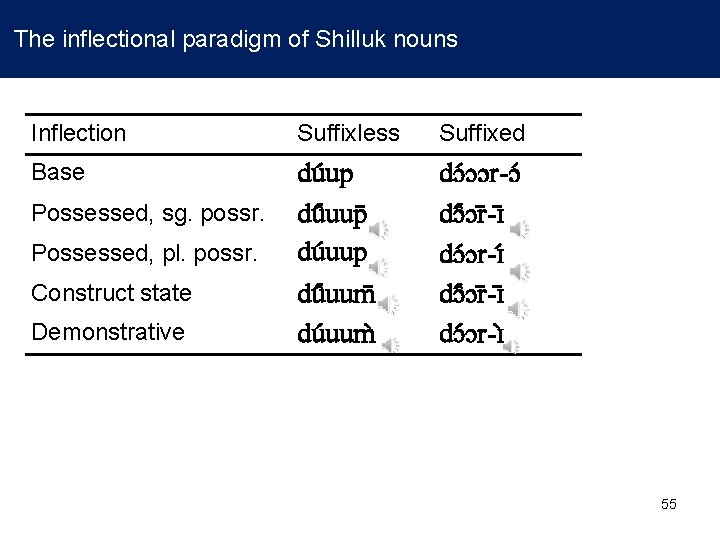

The inflectional paradigm of Shilluk nouns Inflection Suffixless Suffixed Base du up du uup dɔ ɔɔr-ɔ dɔ ɔr -ɪ dɔ ɔr-ɪ Possessed, sg. possr. Possessed, pl. possr. Construct state Demonstrative du uum 55

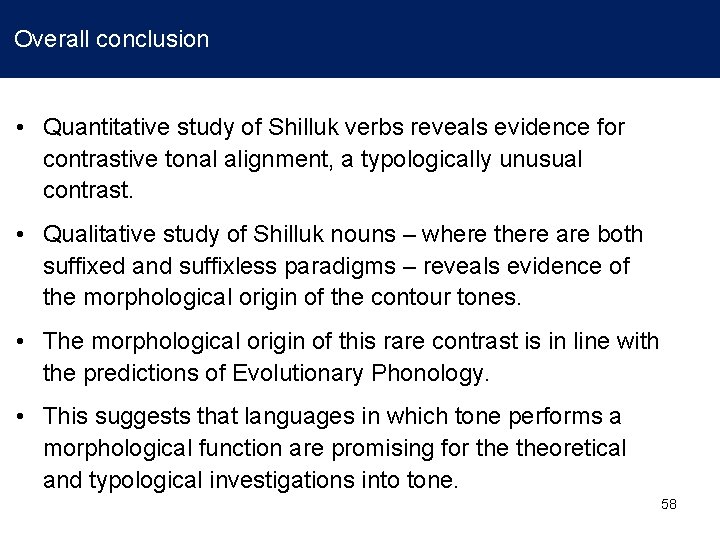

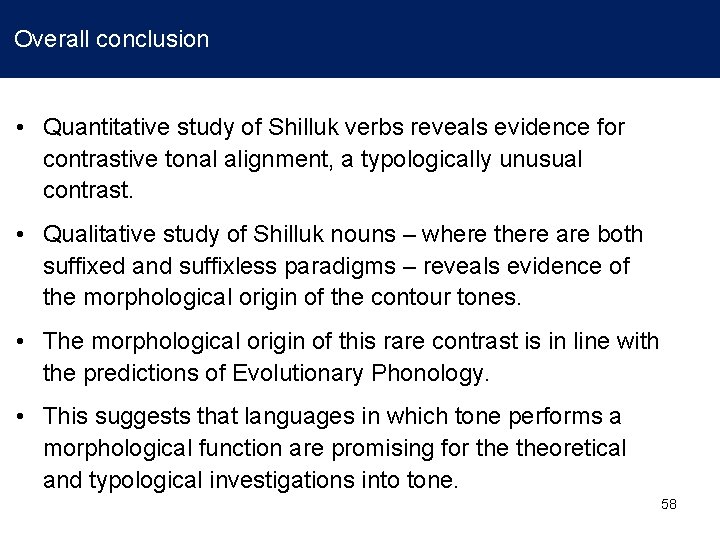

The inflectional paradigm of Shilluk nouns Inflection Suffixless Base du up du uup Possessed, sg. possr. Possessed, pl. possr. Construct state Demonstrative du uum High Fall to Mid Late Fall 56

Late Fall also on short vowels Nouns: ‘mouse’ du up Demonstrative du uum Base ‘mouth’ d ɔ k d ɔ ŋ 57

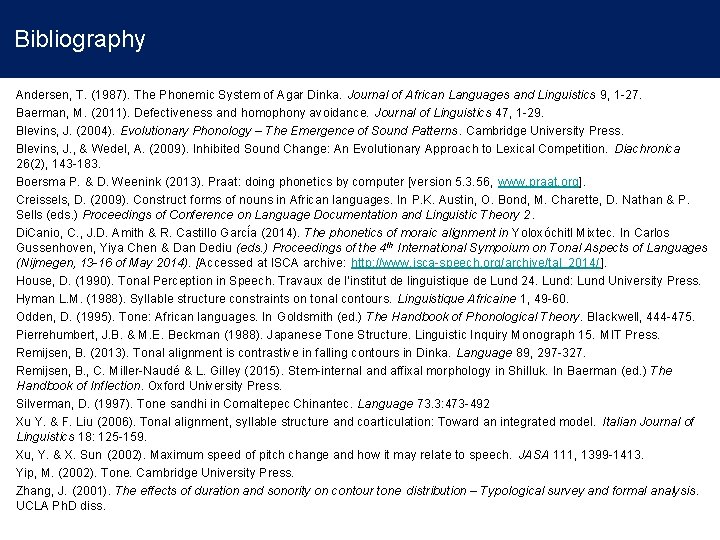

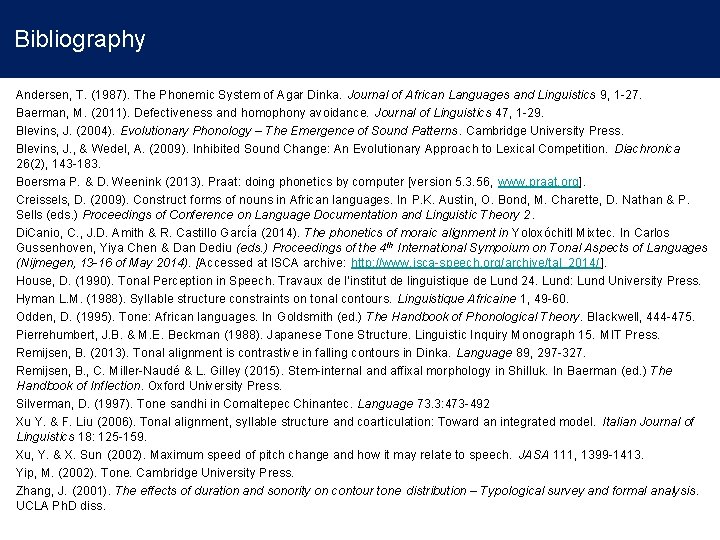

Overall conclusion • Quantitative study of Shilluk verbs reveals evidence for contrastive tonal alignment, a typologically unusual contrast. • Qualitative study of Shilluk nouns – where there are both suffixed and suffixless paradigms – reveals evidence of the morphological origin of the contour tones. • The morphological origin of this rare contrast is in line with the predictions of Evolutionary Phonology. • This suggests that languages in which tone performs a morphological function are promising for theoretical and typological investigations into tone. 58

Bibliography Andersen, T. (1987). The Phonemic System of Agar Dinka. Journal of African Languages and Linguistics 9, 1 -27. Baerman, M. (2011). Defectiveness and homophony avoidance. Journal of Linguistics 47, 1 -29. Blevins, J. (2004). Evolutionary Phonology – The Emergence of Sound Patterns. Cambridge University Press. Blevins, J. , & Wedel, A. (2009). Inhibited Sound Change: An Evolutionary Approach to Lexical Competition. Diachronica 26(2), 143 -183. Boersma P. & D. Weenink (2013). Praat: doing phonetics by computer [version 5. 3. 56, www. praat. org]. Creissels, D. (2009). Construct forms of nouns in African languages. In P. K. Austin, O. Bond, M. Charette, D. Nathan & P. Sells (eds. ) Proceedings of Conference on Language Documentation and Linguistic Theory 2. Di. Canio, C. , J. D. Amith & R. Castillo Garci a (2014). The phonetics of moraic alignment in Yoloxóchitl Mixtec. In Carlos Gussenhoven, Yiya Chen & Dan Dediu (eds. ) Proceedings of the 4 th International Sympoium on Tonal Aspects of Languages (Nijmegen, 13 -16 of May 2014). [Accessed at ISCA archive: http: //www. isca-speech. org/archive/tal_2014/]. House, D. (1990). Tonal Perception in Speech. Travaux de l’institut de linguistique de Lund 24. Lund: Lund University Press. Hyman L. M. (1988). Syllable structure constraints on tonal contours. Linguistique Africaine 1, 49 -60. Odden, D. (1995). Tone: African languages. In Goldsmith (ed. ) The Handbook of Phonological Theory. Blackwell, 444 -475. Pierrehumbert, J. B. & M. E. Beckman (1988). Japanese Tone Structure. Linguistic Inquiry Monograph 15. MIT Press. Remijsen, B. (2013). Tonal alignment is contrastive in falling contours in Dinka. Language 89, 297 -327. Remijsen, B. , C. Miller-Naudé & L. Gilley (2015). Stem-internal and affixal morphology in Shilluk. In Baerman (ed. ) The Handbook of Inflection. Oxford University Press. Silverman, D. (1997). Tone sandhi in Comaltepec Chinantec. Language 73. 3: 473 -492 Xu Y. & F. Liu (2006). Tonal alignment, syllable structure and coarticulation: Toward an integrated model. Italian Journal of Linguistics 18: 125 -159. Xu, Y. & X. Sun (2002). Maximum speed of pitch change and how it may relate to speech. JASA 111, 1399 -1413. Yip, M. (2002). Tone. Cambridge University Press. Zhang, J. (2001). The effects of duration and sonority on contour tone distribution – Typological survey and formal analysis. UCLA Ph. D diss.

Acknowledgements: • The Shilluk speakers: James Peter Othol, Paulino Okan Chol, Anesa Nyacam, Musa Kuku Jago, Emmanuel Antony Deng, Emmanuel John Adung, Alexander Otwongo Ajak, Francis Boywomo Opiti, Tupac Laa Wol, William Amum Onwar, Amum Obwony, and Elia Otham Wan. • The British Council and SIL International, for enabling fieldwork research in South Sudan. • Carlos Gussenhoven and Vincent van Heuven, for valuable feedback. • The Volkswagen Foundation, for research funding through the project “Tonal Placement: Interaction of Qualitative and Quantitative Factors”, coordinated by Martine Grice and Anne Hermes. • The Leverhulme Trust, for research funding through the project “A descriptive analysis of the Shilluk language” (RPG-2015 -055). 60

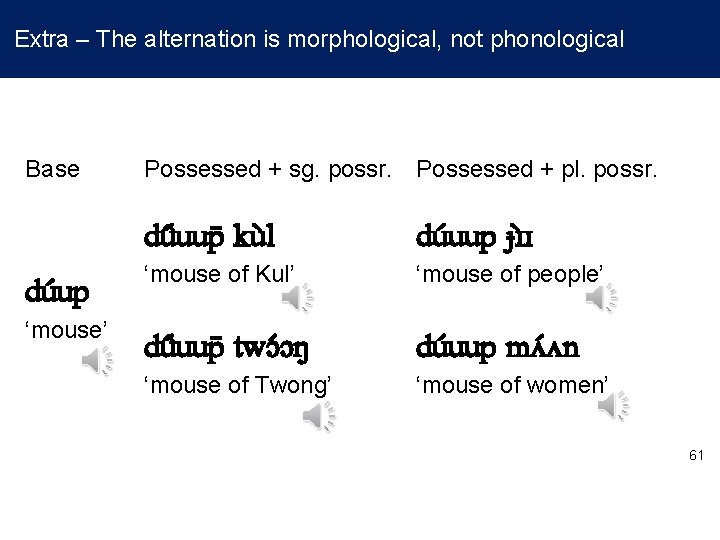

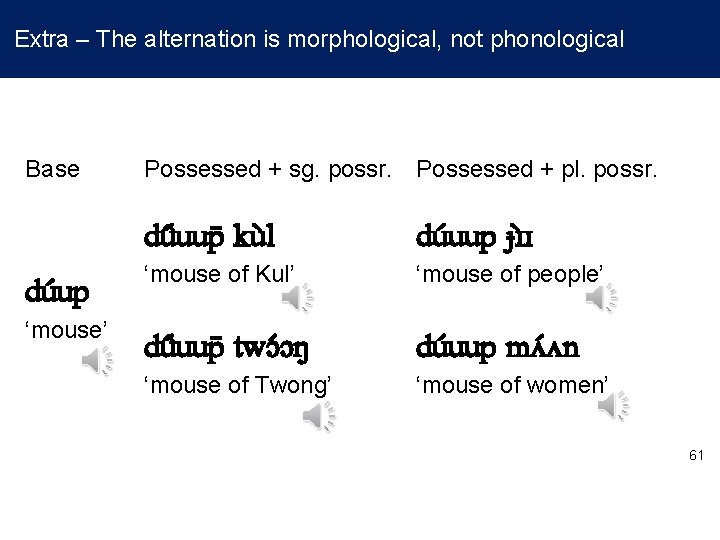

Extra – The alternation is morphological, not phonological Base Possessed + sg. possr. Possessed + pl. possr. du uup ku l du uup ɟɪ ɪ du up ‘mouse of Kul’ ‘mouse of people’ ‘mouse’ du uup twɔ ɔŋ du uup mʌ ʌn ‘mouse of Twong’ ‘mouse of women’ 61

Extra – Counts in the acoustic study • Number of utterance tokens: 293 • Aggregated over repetitions, ahead of quantitative analyses: 154 types. So there are 8 missing values, given a logical total of 162 (18 items x 9 speakers). • ANOVAs are based on balanced dataset, with 105 types. So there are 3 missing values, given a logical total of 108 (12 items [3 for each level of Tone] x 9 speakers). 62

Extra – The question of representation “If further research uncovers cases where the alignment is contrastive within a language, these might be handled by the use of an alignment feature on the prosodic nodes or on the substantive elements” [Pierrehumbert & Beckman 1988: 159] In other words, we can enrich the specification on the tonal tier, or on the prosodic constituents with which the tones are linked. 63