Tom Stoppard I Introduction to Tom Stoppard Sir

- Slides: 39

Tom Stoppard

I. Introduction to Tom Stoppard Sir Tom Stoppard (born 3 July 1937) is a British screenwriter and playwright. He has written plays such as The Coast of Utopia, Arcadia, Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead, and Rock 'n' Roll. . THEATRE: STOPPARD‘S PLAYS DEAL WITH PHILOSOPHICAL ISSUES WHILE PRESENTING VERBAL WIT AND VISUAL HUMOUR. THE LINGUISTIC COMPLEXITY OF HIS WORKS, WITH THEIR PUNS, JOKES, INNUENDO, AND OTHER WORDPLAY, IS A CHIEF CHARACTERISTIC OF HIS WORK. MANY ALSO FEATURE MULTIPLE TIMELINES.

Analysis of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, Tom Stoppard's best-known and first major play, appeared initially as an amateur production in Edinburgh, Scotland, in August of 1966. Subsequent professional productions in London and New York in 1967 made Stoppard an international sensation and three decades and a number of major plays later Stoppard is now considered one of the most important playwrights in the latter half of the twentieth century.

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead By Tom Stoppard l Background Information l Plot Summary l Character Analysis l Themes and Motifs l Lines and Speeches l Bibliography

Background Information About Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead

Background Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead is an absurdist, existentialist tragic comedy by Tom Stoppard. The play expands upon the exploits of two minor characters from Shakespeare's Hamlet, the courtiers Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. The action of Stoppard's play takes place mainly 'in the wings' of Shakespeare's, with brief appearances of major characters from Hamlet who enact fragments of the original's scenes. Between these episodes the two protagonists voice their confusion at the progress of events of which—occurring onstage without them in Hamlet—they have no direct knowledge.

A Summary of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead

Plot Summary Specific plot is hard to decipher Two minor characters (from Hamlet) are turned into major characters Based on the same period of time as Hamlet

Plot Analysis Randomness Chance Foreshadowing

The Characters of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead

Major Characters Rosencrantz A gentleman and childhood friend of Hamlet. Along with his companion, Guildenstern, Rosencrantz seeks to uncover the cause of Hamlet’s strange behavior but finds himself confused by his role in the action of the play. Rosencrantz has a carefree and artless personality that masks deep dread about his fate. Guildenstern A gentleman and childhood friend of Hamlet. Accompanied by Rosencrantz, Guildenstern tries to discover what is plaguing Hamlet as well as his own purpose in the world. Although frequently disconcerted by the world around him, Guildenstern is a meditative man who believes that he can understand his life.

Major Characters The Player The leader of the traveling actors known as the Tragedians. The Player is an enigmatic figure. His cunning wit and confident air suggest that he knows more than he is letting on. The impoverished state of his acting troupe makes him eager to please others, but only on his own terms. Hamlet The prince of Denmark and a childhood friend of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. Hamlet is thrown into a deep personal crisis when his father dies and his uncle takes the throne and marries Hamlet’s mother. Hamlet’s strange behavior confuses the other characters, especially Rosencrantz and Guildenstern.

Minor Characters The Tragedians A group of traveling male actors. The Tragedians specialize in melodramatic and sensationalistic performances, and they are willing to engage in sexual entertainments if the price is right. Claudius Hamlet’s uncle and the new king of Denmark. Claudius is a sinister character who tries to exploit the friendship between Rosencrantz, and Guildenstern and Hamlet to learn what Hamlet believes about the king’s marriage to Gertrude.

Minor Characters Gertrude Hamlet’s mother and the queen of Denmark. Although she has disgraced herself by marrying Claudius so soon after husband’s death, Gertrude does seem to care for Hamlet’s well-being and sincerely hopes that Rosencrantz and Guildenstern can help her son. Polonius A member of the Danish court and adviser to Claudius. Polonius is a shifty man, willing to interrogate Hamlet and even spy on him to learn what he wants to know.

Minor Characters Ophelia The daughter of Polonius and Hamlet’s former beloved. Ophelia spends the play in a state of shock and anguish as a result of Hamlet’s bizarre conduct. Laertes The son of Polonius and brother of Ophelia. Laertes does not appear in the action of the play, but his corpse appears in the final scene.

Themes and Motifs in Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead

Themes and Motifs in Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead l. Absurdity l. Existentialism l. Fatalism l. Insignificance

Absurdity “Heads. ” Characters are unable to recognize laws that regulate nature Character’s language is an obstacle to expressing thoughts Nothing in life has meaning, except the meaning we give to it

Existentialism: “Nothing is more real than Nothing” Existence precedes essence Traditional storyline replaced with fleeting, abstract images The world is incomprehensible Rejection of Determinism

Fatalism Characters are unable to change course of events Stoppard differs from existentialists in his use of determinism Schrödinger's cat Death is inescapable

Insignificance “Who’d have thought we were so important? ” Plot of Hamlet continues, regardless of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern’s actions Differs from nihilism (particularly Beckett) in that, rather than having no role in universe, men are trapped in unfathomable roles Expendable pawns in uncontrollable universe

Language and Communication In Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, the two title characters often play with words. They pun off of each other's words without much intention of moving their dialogue toward a set purpose. Instead, they are simply goofing around, like two kids throwing a ball back and forth. At the same time, however, the consistently poor communication in the play seems to hint at a broader breakdown in understanding between the characters that may help send the play into its tragic spiral. Language is sometimes seen as an empowering way of writing one's own fate, but for Ros and Guil it often seems like an impotent tool, best suited for idle speculation.

Isolation In Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, main characters Ros and Guil, when left alone in the play, often suffer from feelings of isolation. In the opening and closing scenes of the play, it is just Ros and Guil alone on stage. One wonders if it is the degree to which these two are isolated that has led to their constant idleness and passivity, or if things worked the other way around. From the very start of the play, however, it does seem as if Ros and Guil are marked, as if they are moving toward their deaths, simply passing through the action of the play. The sense of isolation reaches its highest pitch, perhaps, when it is just the two of them in the dark on the boat in the last act. It is, in a sense, a premonition of death, or a fear of what death might be: bodiless nothingness, with only the mind working.

Manipulation People use each other quite a bit in Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, and part of the reason the main characters, Ros and Guil, are never in control of their situation is because they seem naively incapable of using the people around them. Manipulation, in many ways, is compared the act of directing a play – it's the ability to control the course of events. A play is explored as something that manipulates the audience: something that attempts to affect the way that they think and feel.

Fear In the opening of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, there is a long string of coin flips that come up heads, which frightens Guil, one of the main characters. He later attempts to reason through how the laws of probability could seemingly be suspended, and at one point concludes, "The scientific approach to the examination of phenomena is a defence against the pure emotion of fear" (1. 73). What Guil means is that we fear the unknown (such as death). Science, by trying to make things comprehensible, attempts to reduce this fear. By coming to know things about our world and the laws by which it works, we try to feel more at home in it, more like we have a handle on what is happening. The alternative – recognizing just how little we know about the world around us – causes fear.

Foolishness and Folly In many ways, in Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead it is the title characters' fault that they die. They are easily, and, at times, willingly manipulated. Not to mention, Ros and Guil spend a good portion of the play messing around – swapping names, misunderstanding each other, playing at games of their own devising. Their foolishness is, in part, a source of comedy, but it also seems a natural way to stay entertained when one has as little to do.

Passivity Ros and Guil may be at the center of the action in Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, but they certainly don't drive it. It can be seen most clearly in Act II how they are just left to sit around and wait unless someone else crosses the stage or tells them what to do. Another main character, the Player, seems to suggest that they should be more active and that Guil shouldn't waste so much time questioning things, but Guil is less concerned with action than with freedom of action. Yet, in the end, the fact that Ros and Guil betray their friend Hamlet makes their passivity morally significant; their failure to act may play a role in their own fates.

Versions of Reality In Shakespeare's Hamlet, the play-within-a-play is packed within a clear context and is used by Hamlet to send a message to Claudius. For us as the audience of Stoppard's play, however, the distinctions between a play and reality get totally jumbled. First, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern is nothing but a play on the stage. Secondly, it is a play that interacts with the action of an earlier play, Shakespeare's Hamlet. Third, it is unclear to what extent the Player and his Tragedians are driving the action of the play and to what extent the "real" characters are in control of what is happening. The difference between drama and reality is called into question, most explicitly in the arguments between Guil and the Player.

The Lines and Speeches of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead

Lines and Speeches “Do you remember the first thing that happened today? ” - Guildenstern (pg 19) “My name is Guildenstern, and this is Rosencrantz. ” –Rosencrantz (pg 22) “Give us this day our daily mask. ” – Guildenstern (pg 39) “To be taken in hand led, like a child again, even without the innocence, a child- it’s like being given a prize, an extra slice of childhood when you least expect it…” – Guildenstern (pg 40)

Lines and Speeches “What are you playing at? ”… “Words, words. They’re all we have to go on. ” – Rosencrantz and Guildenstern (pg 41) “He murdered us. ”… “Half of what he said meant something else, and the other half didn’t mean anything at all. ” – Rosencrantz (pg 57) “ Each move is dictated by the previous one- that is the meaning of order. ” – Guildenstern (pg 60) “Uncertainty is the normal state. You’re nobody special. ” – Player (pg 66)

Lines and Speeches “A man talking sense to himself is no madder than a man talking nonsense not to himself. ” – Guildenstern (pg 68) “… for all the compasses in the world, there’s only one direction, and time is its measure. ” – Rosencrantz (pg 72) “The play” – Player (pg 81 -82)

Lines and Speeches “ I like to know where I am. Even if I don’t know where I am, I like to know that. If we go there’s no knowing. ” – Guildenstern (pg 95) “ Life is a gamble , at terrible odds- if it was a bet you wouldn’t take it. Did you know that any number doubled is even? ” – Player (pg 115) “ There must have been a moment, at the beginning, where we could have said-no. But somehow we missed it. ” – Guildenstern (pg 125)

Discussion Questions for Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead Act I l Act III l

Act I Discussion Questions Why do you believe that Tom Stoppard chose to display Rosencrantz and Guildenstern as two characters that don’t exactly know where they are, what is going on, or even why they are in the position they are? Why do Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, at the end of the first act, use role play to practice asking questions of one another? Why is it that Rosencrantz is always expecting people to appear? Why did Rosencrantz put his hand under the player’s foot? What is the significance of Guildenstern’s repetition of “Give us this day our daily…”?

Act II Discussion Questions G: "You'll never be able to. . . taste your tears" R: "Your breakfast. " G: "You won't know the difference. " R: "There won't be any. " When Rosencrantz says that there will be no difference between the flavor of tears and breakfast because you can't taste any, is he right? How does perspective affect the truth? Is there a difference between perspective and truth? How do individuals reconcile their own perspectives with "accepted" truths in society, such as the belief that tears and breakfast taste dissimilar? Why does Stoppard choose to incorporate exact dialogue and characters from Shakespeare’s Hamlet?

Act III Discussion Questions At what point did Rosencrantz and Guildenstern lose control of their destiny? How do individuals decide whether they control fate, or whether fate controls them? What is the relationship between fate and God? A modern audience laughs at Guildenstern's proclamation that he "never believed in England anyway", yet people are, more or less, hardwired to be doubting Thomases. A modern audience also laughs at individuals who, on the other end of the spectrum, are considered gullible. How do we find middle ground? How do we decide who or what we trust? How does a disbelief in England from an average Dane in Hamlet's day compare to a disbelief in the galaxy Andromeda or quantum mechanics today?

Act III Discussion Questions Why do you think the author chose to write about Rosencrantz and Guildenstern over any other minor characters in history? Why do you think Hamlet switched the letters? Why couldn’t he just go back? Could he have worked around getting Rosencrantz and Guildenstern killed? Do you believe that they were in a parallel universe? What happened when they died?

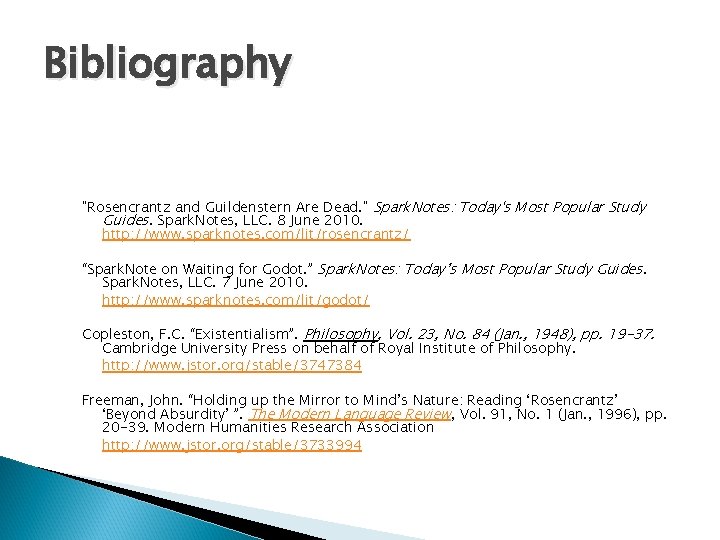

Bibliography "Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead. " Spark. Notes: Today's Most Popular Study Guides. Spark. Notes, LLC. 8 June 2010. http: //www. sparknotes. com/lit/rosencrantz/ “Spark. Note on Waiting for Godot. ” Spark. Notes: Today’s Most Popular Study Guides. Spark. Notes, LLC. 7 June 2010. http: //www. sparknotes. com/lit/godot/ Copleston, F. C. “Existentialism”. Philosophy, Vol. 23, No. 84 (Jan. , 1948), pp. 19 -37. Cambridge University Press on behalf of Royal Institute of Philosophy. http: //www. jstor. org/stable/3747384 Freeman, John. “Holding up the Mirror to Mind’s Nature: Reading ‘Rosencrantz’ ‘Beyond Absurdity’ ”. The Modern Language Review, Vol. 91, No. 1 (Jan. , 1996), pp. 20 -39. Modern Humanities Research Association http: //www. jstor. org/stable/3733994

Tom stoppard absurdism

Tom stoppard absurdism Tomtom go 910 update

Tomtom go 910 update The devil and tom walker symbols

The devil and tom walker symbols Yip sir

Yip sir Sir edmond halley

Sir edmond halley Where is jessica going answer

Where is jessica going answer Risala asbab-i-baghawat-i-hind

Risala asbab-i-baghawat-i-hind Inertia in everyday life

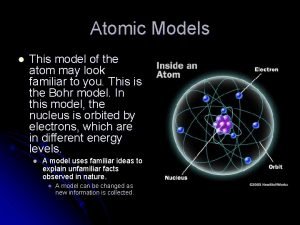

Inertia in everyday lifeHenry moseley atomic theory timeline

Sistema de interconexión de registros

Sistema de interconexión de registros Where was sir william alexander smith born

Where was sir william alexander smith born United indian patriotic association in hindi

United indian patriotic association in hindi Sir robert moray

Sir robert moray Kako napraviti masni sir od kravljeg mlijeka

Kako napraviti masni sir od kravljeg mlijeka Sir philis

Sir philis Sir john cornforth

Sir john cornforth Sir john cornforth

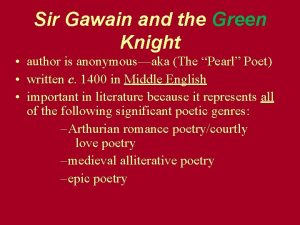

Sir john cornforth Gawain and the green knight hero's journey

Gawain and the green knight hero's journey Sir gawain fitt 3

Sir gawain fitt 3 Symbology

Symbology Sir calculation

Sir calculation Sir

Sir Sir pronoun

Sir pronoun Farewell love and all thy laws forever analysis

Farewell love and all thy laws forever analysis Yip sir

Yip sir Of revenge by bacon

Of revenge by bacon The law of motion

The law of motion How to pronounce sir gawain

How to pronounce sir gawain Tindakan orang melayu menentang malayan union

Tindakan orang melayu menentang malayan union Sir john dunford

Sir john dunford Modified ward's incision

Modified ward's incision What is ideology of pakistan

What is ideology of pakistan Gday math

Gday math Sir launcelot du lake

Sir launcelot du lake Sir walter raleigh's goal

Sir walter raleigh's goal Sir thomas more fruitopia

Sir thomas more fruitopia Sir james chadwick atomic theory

Sir james chadwick atomic theory They flee from me analysis

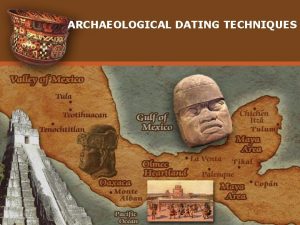

They flee from me analysis Sir mortimer wheeler scientific and soil layer method

Sir mortimer wheeler scientific and soil layer method Kommunikatsiya deganda nimani tushunasiz

Kommunikatsiya deganda nimani tushunasiz