The TwoBody Problem The twobody problem The twobody

The Two-Body Problem

The two-body problem • The two-body problem: two point objects in 3 D interacting with each other (closed system) • Interaction between the objects depends only on the distance between them • The number of degrees of freedom: 6 • Phase space dimensions: 12 3. 1

The two-body problem • The Lagrangian of the system in Cartesian coordinates: • It is a very non-trivial problem if we try to deal with the Lagrangian in this format: all the 6 independent coordinates are entangled in the potential function • Let us look for a different configuration space 3. 1

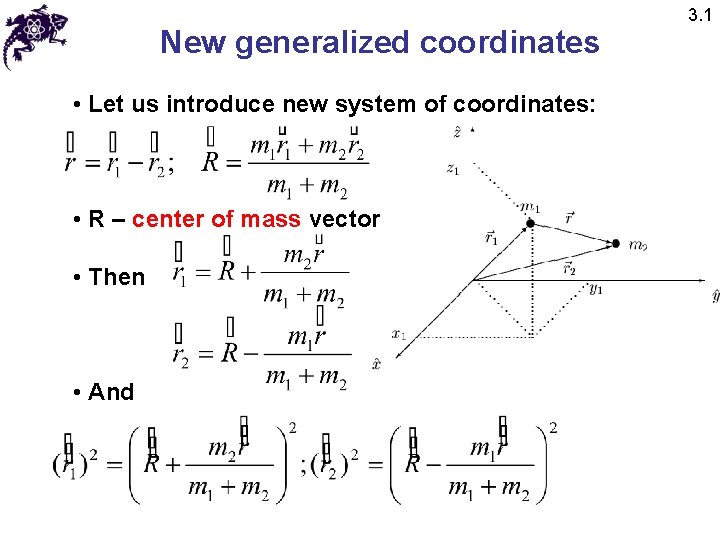

New generalized coordinates • Let us introduce new system of coordinates: • R – center of mass vector • Then • And 3. 1

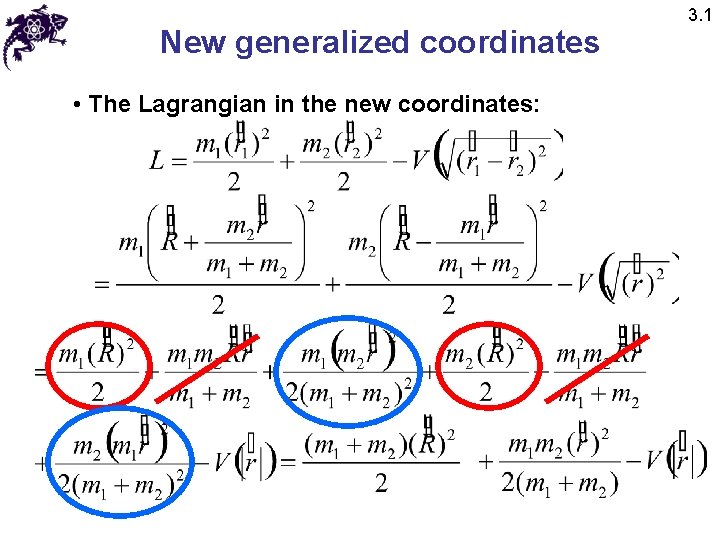

New generalized coordinates • The Lagrangian in the new coordinates: 3. 1

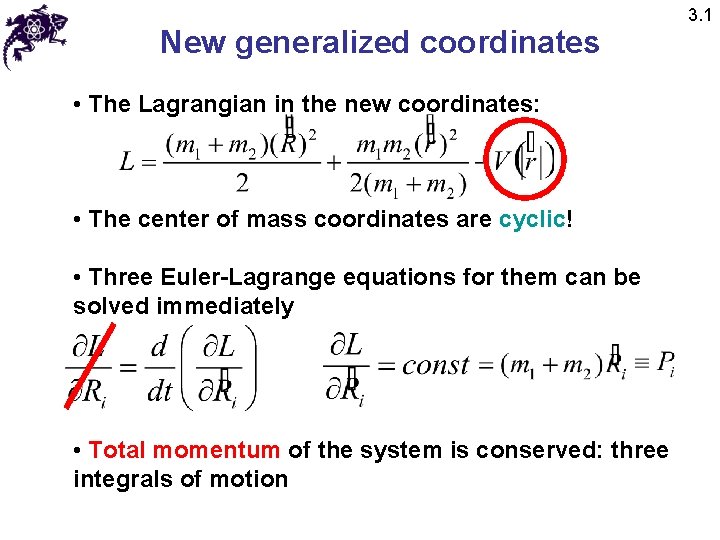

New generalized coordinates • The Lagrangian in the new coordinates: • The center of mass coordinates are cyclic! • Three Euler-Lagrange equations for them can be solved immediately • Total momentum of the system is conserved: three integrals of motion 3. 1

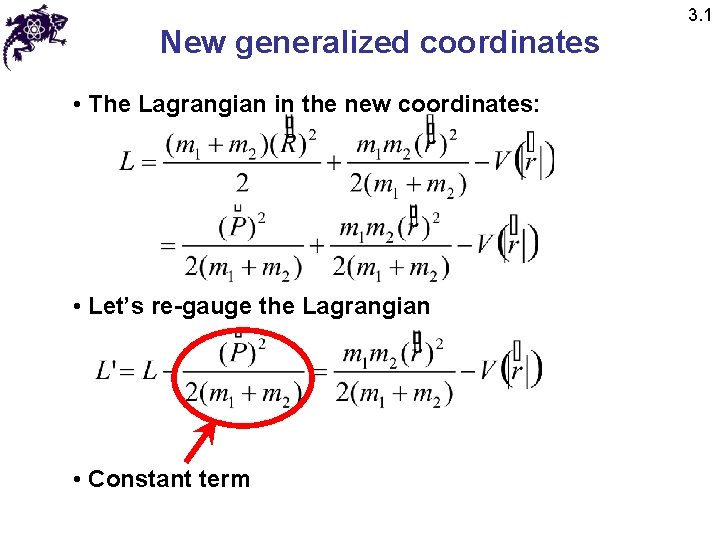

New generalized coordinates • The Lagrangian in the new coordinates: • Let’s re-gauge the Lagrangian • Constant term 3. 1

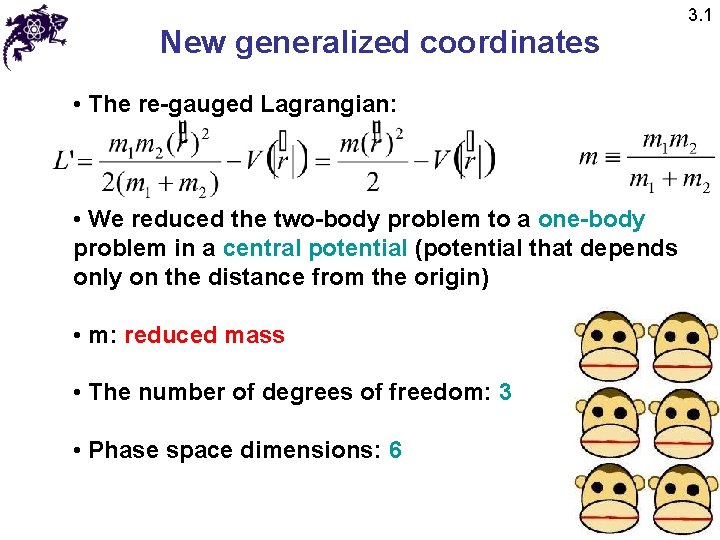

New generalized coordinates • The re-gauged Lagrangian: • We reduced the two-body problem to a one-body problem in a central potential (potential that depends only on the distance from the origin) • m: reduced mass • The number of degrees of freedom: 3 • Phase space dimensions: 6 3. 1

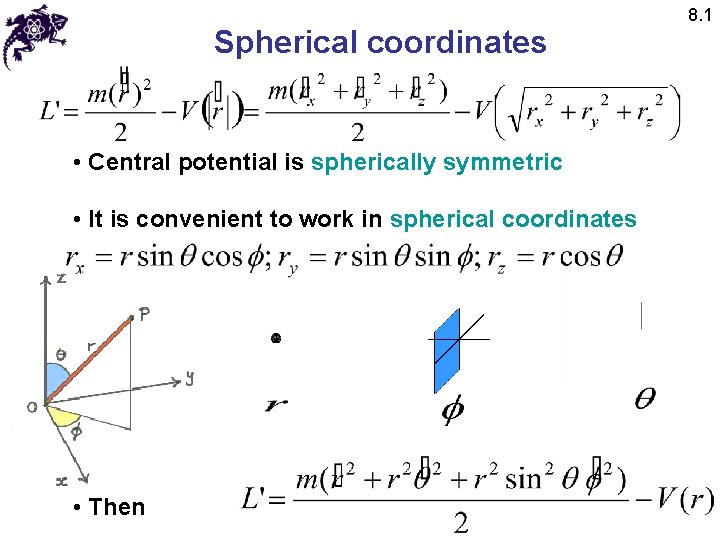

Spherical coordinates • Central potential is spherically symmetric • It is convenient to work in spherical coordinates • Then 8. 1

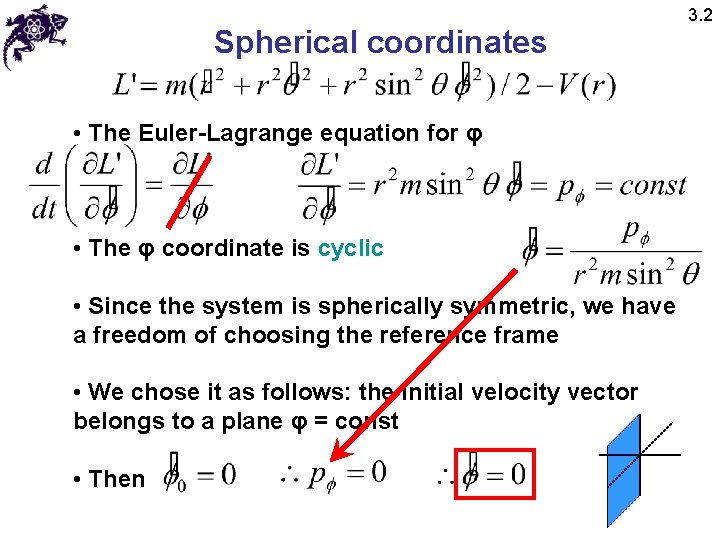

Spherical coordinates • The Euler-Lagrange equation for φ • The φ coordinate is cyclic • Since the system is spherically symmetric, we have a freedom of choosing the reference frame • We chose it as follows: the initial velocity vector belongs to a plane φ = const • Then 3. 2

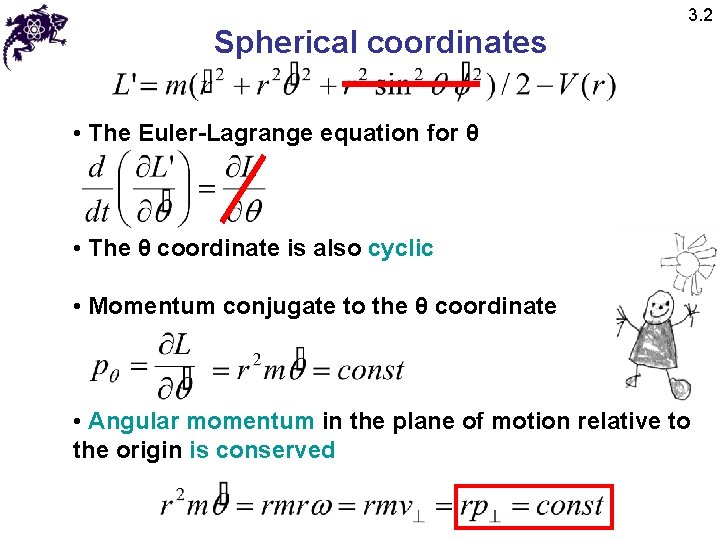

Spherical coordinates 3. 2 • The Euler-Lagrange equation for θ • The θ coordinate is also cyclic • Momentum conjugate to the θ coordinate • Angular momentum in the plane of motion relative to the origin is conserved

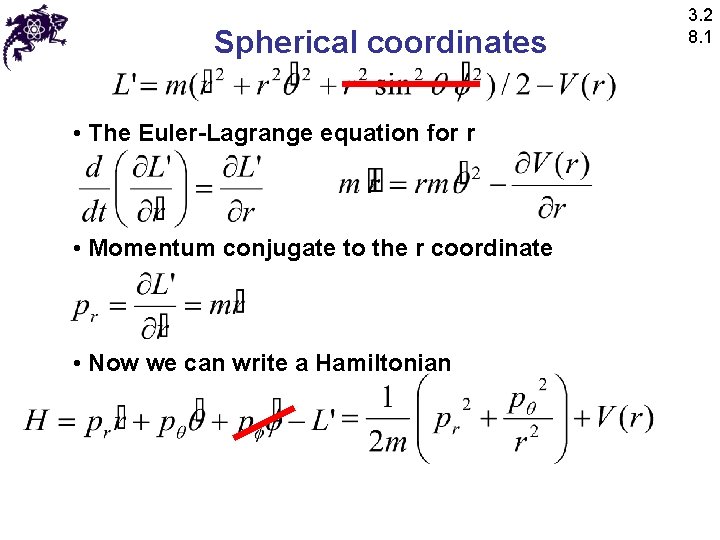

Spherical coordinates • The Euler-Lagrange equation for r • Momentum conjugate to the r coordinate • Now we can write a Hamiltonian 3. 2 8. 1

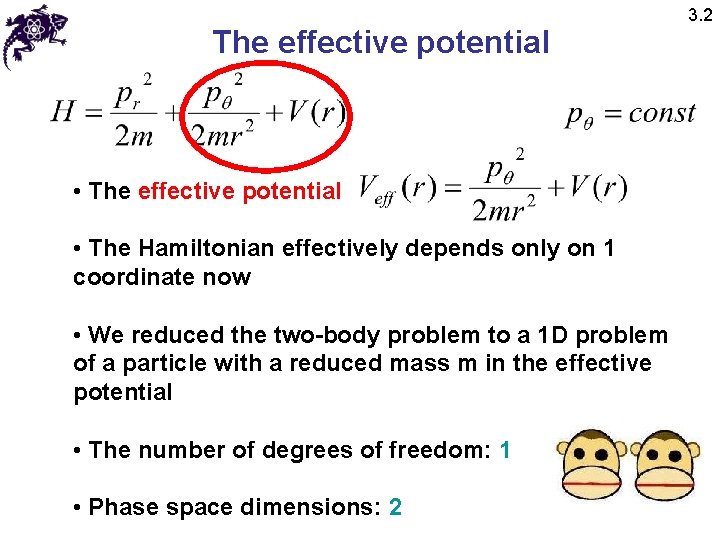

The effective potential • The effective potential • The Hamiltonian effectively depends only on 1 coordinate now • We reduced the two-body problem to a 1 D problem of a particle with a reduced mass m in the effective potential • The number of degrees of freedom: 1 • Phase space dimensions: 2 3. 2

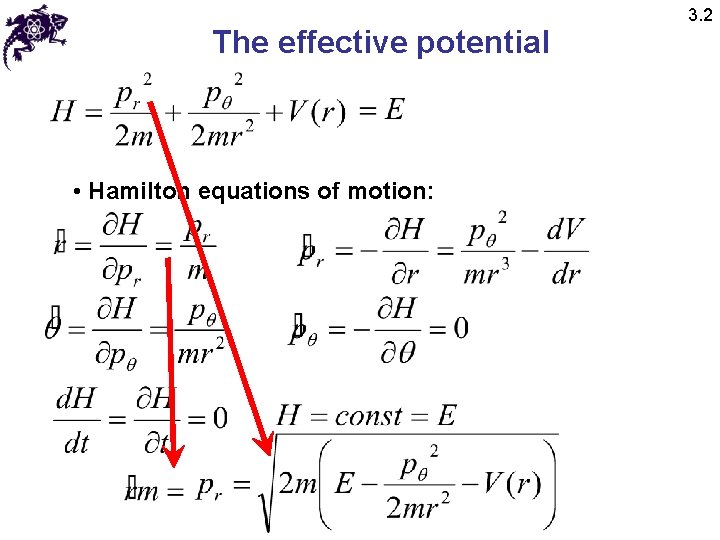

The effective potential • Hamilton equations of motion: 3. 2

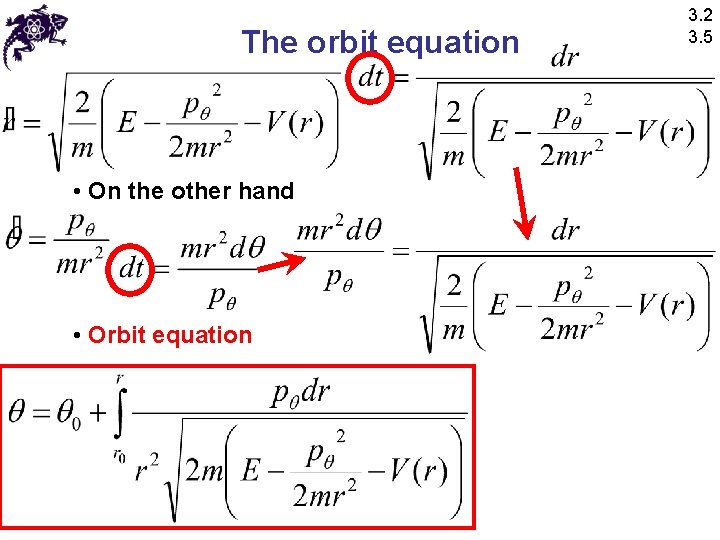

The orbit equation • On the other hand • Orbit equation 3. 2 3. 5

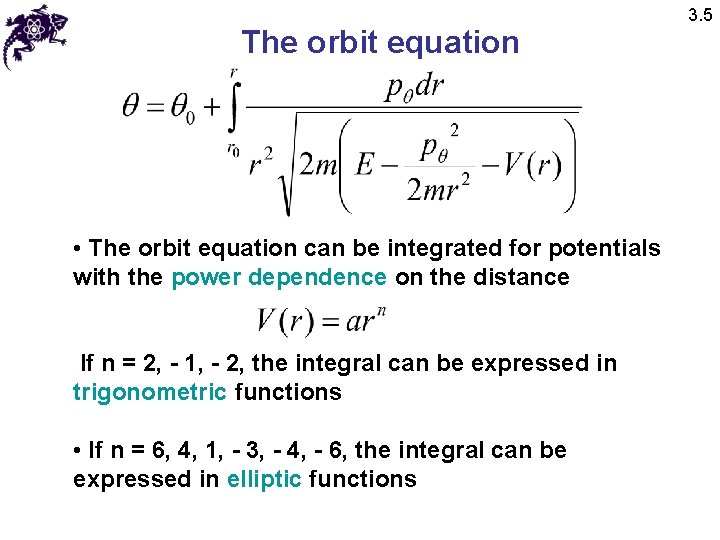

The orbit equation • The orbit equation can be integrated for potentials with the power dependence on the distance If n = 2, - 1, - 2, the integral can be expressed in trigonometric functions • If n = 6, 4, 1, - 3, - 4, - 6, the integral can be expressed in elliptic functions 3. 5

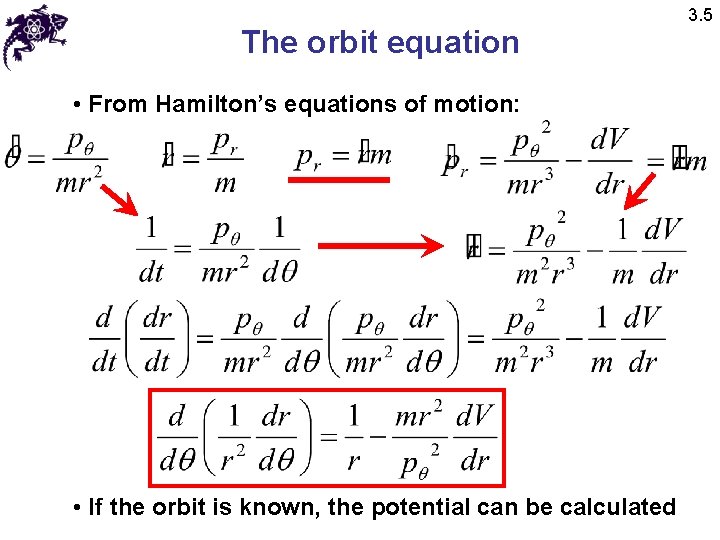

The orbit equation • From Hamilton’s equations of motion: • If the orbit is known, the potential can be calculated 3. 5

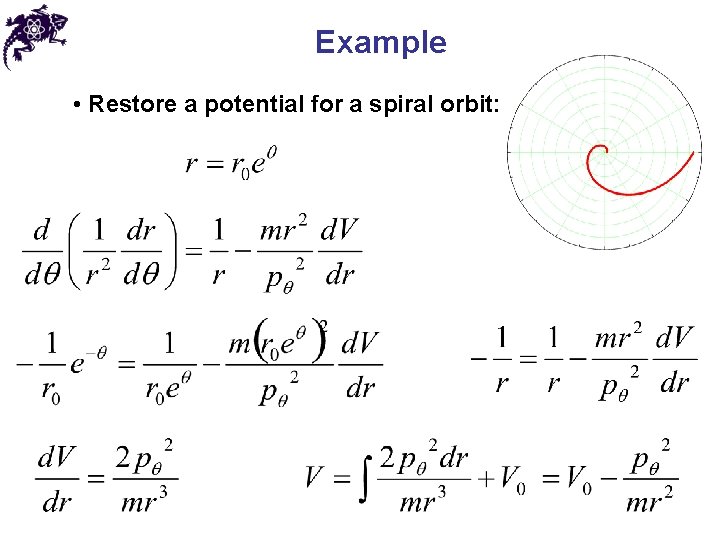

Example • Restore a potential for a spiral orbit:

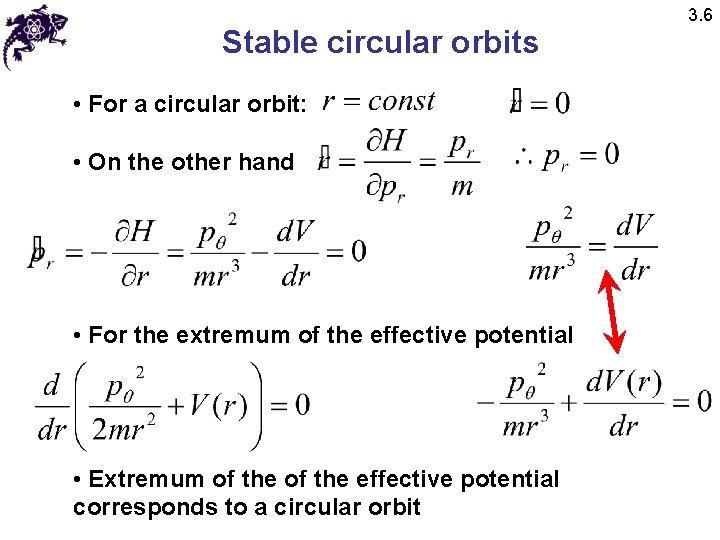

Stable circular orbits • For a circular orbit: • On the other hand • For the extremum of the effective potential • Extremum of the effective potential corresponds to a circular orbit 3. 6

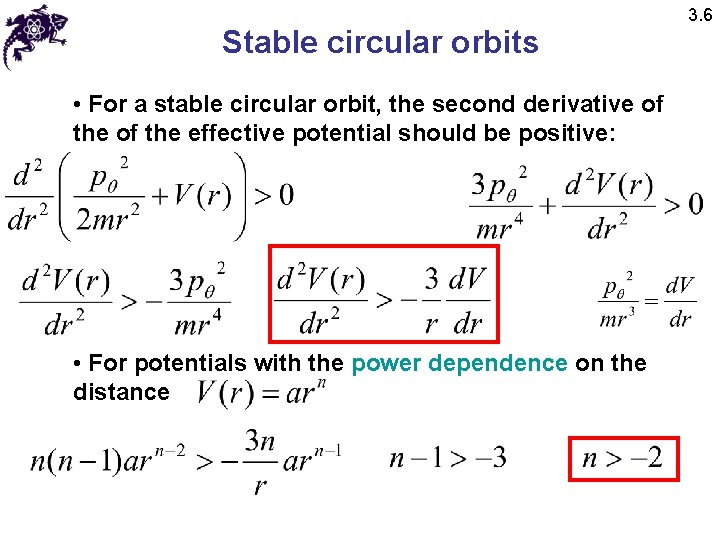

Stable circular orbits • For a stable circular orbit, the second derivative of the effective potential should be positive: • For potentials with the power dependence on the distance 3. 6

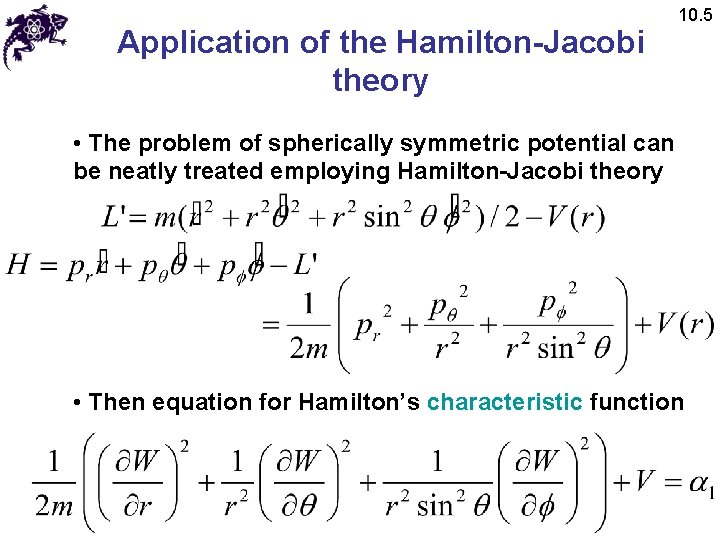

Application of the Hamilton-Jacobi theory 10. 5 • The problem of spherically symmetric potential can be neatly treated employing Hamilton-Jacobi theory • Then equation for Hamilton’s characteristic function

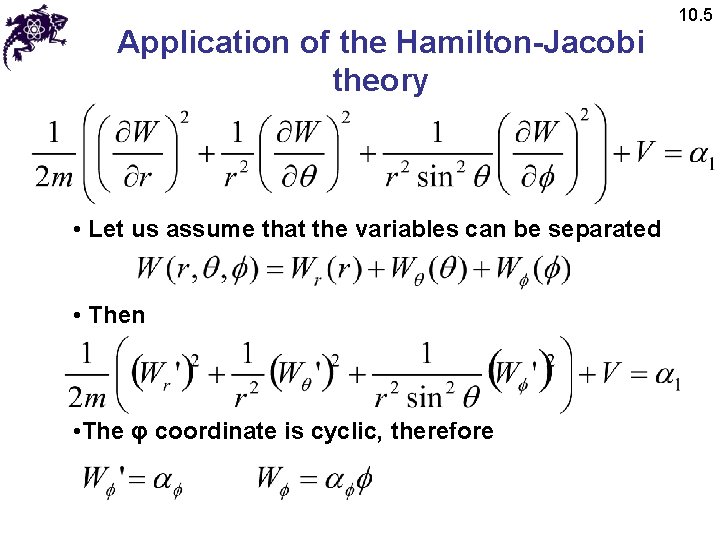

Application of the Hamilton-Jacobi theory • Let us assume that the variables can be separated • Then • The φ coordinate is cyclic, therefore 10. 5

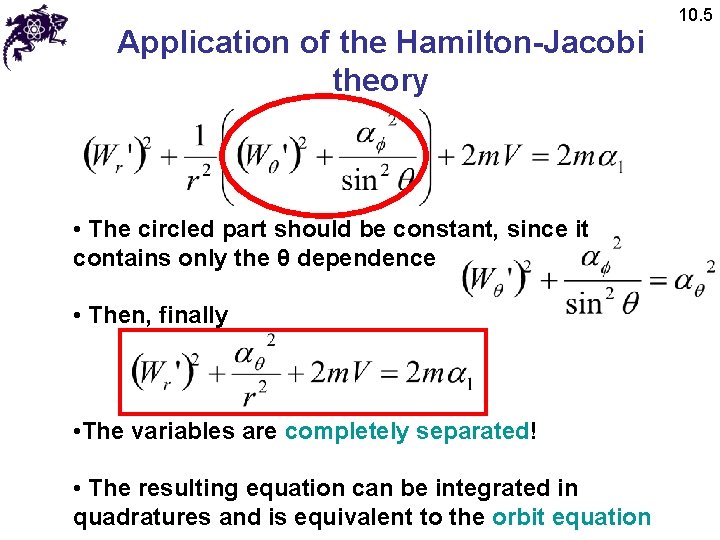

Application of the Hamilton-Jacobi theory • The circled part should be constant, since it contains only the θ dependence • Then, finally • The variables are completely separated! • The resulting equation can be integrated in quadratures and is equivalent to the orbit equation 10. 5

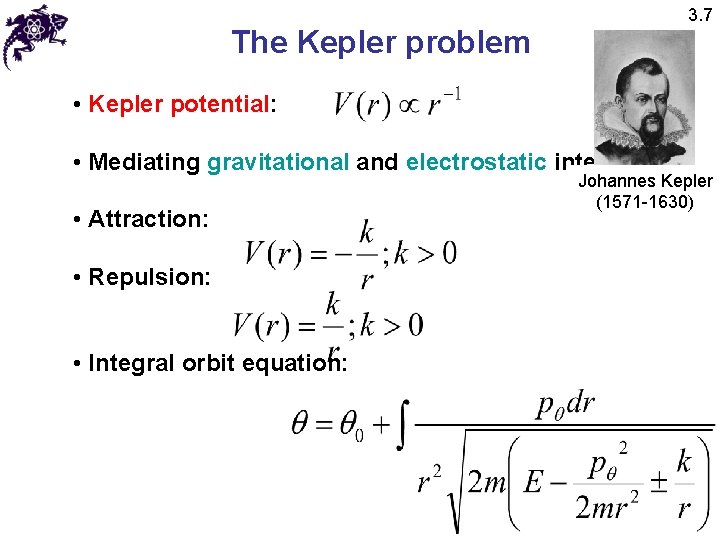

The Kepler problem 3. 7 • Kepler potential: • Mediating gravitational and electrostatic interactions • Attraction: • Repulsion: • Integral orbit equation: Johannes Kepler (1571 -1630)

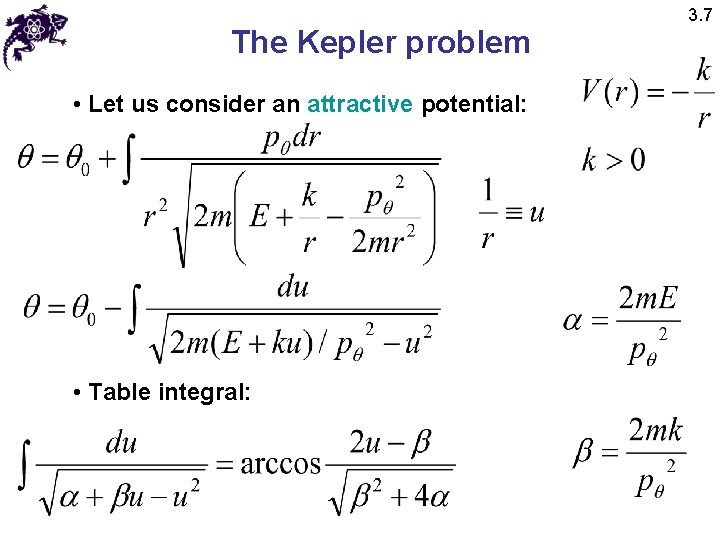

The Kepler problem • Let us consider an attractive potential: • Table integral: 3. 7

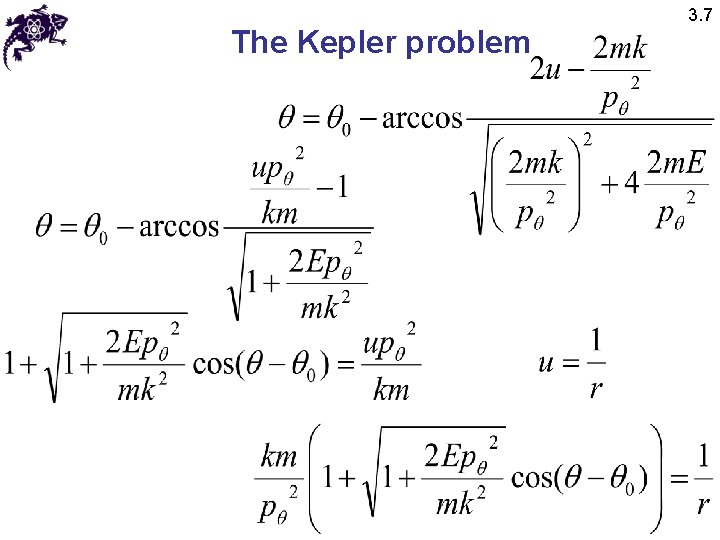

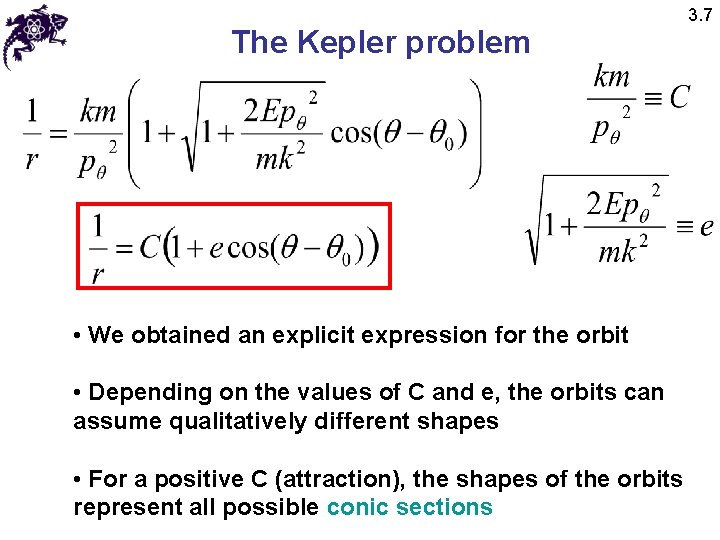

The Kepler problem 3. 7

The Kepler problem • We obtained an explicit expression for the orbit • Depending on the values of C and e, the orbits can assume qualitatively different shapes • For a positive C (attraction), the shapes of the orbits represent all possible conic sections 3. 7

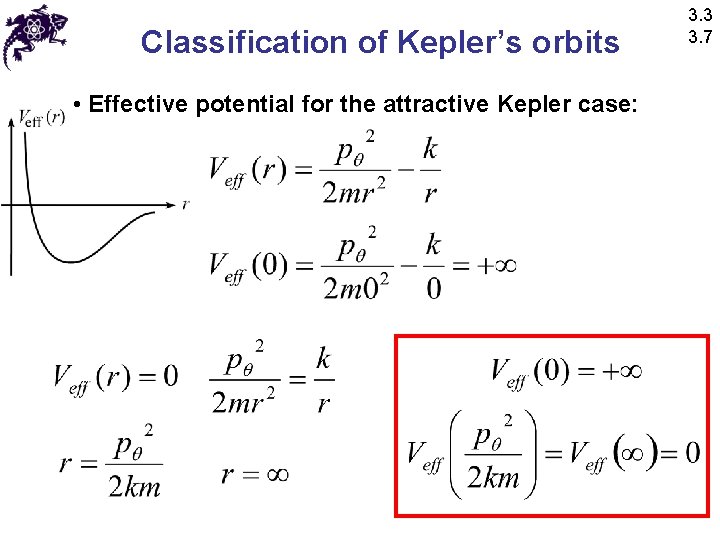

Classification of Kepler’s orbits • Effective potential for the attractive Kepler case: 3. 3 3. 7

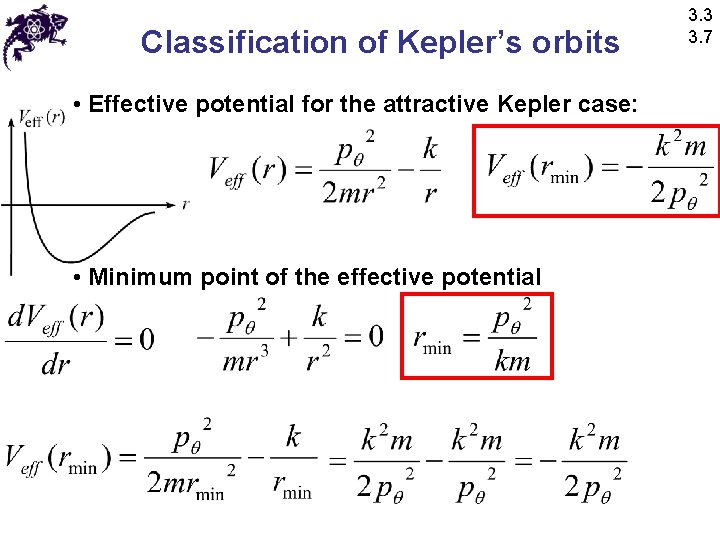

Classification of Kepler’s orbits • Effective potential for the attractive Kepler case: • Minimum point of the effective potential 3. 3 3. 7

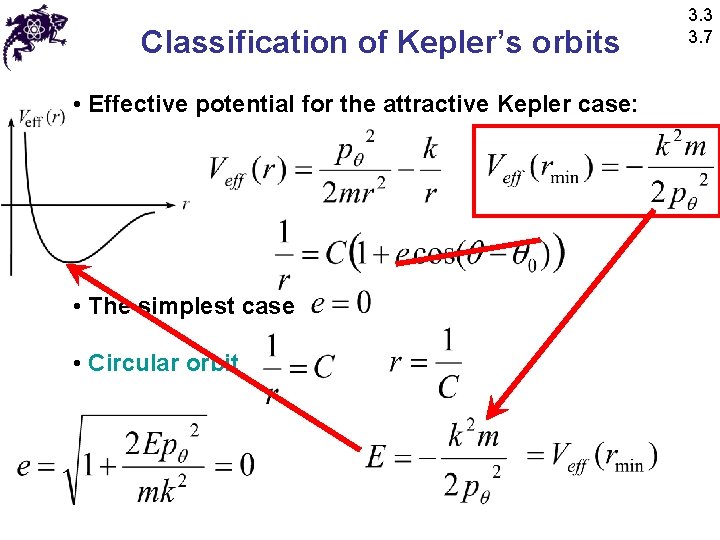

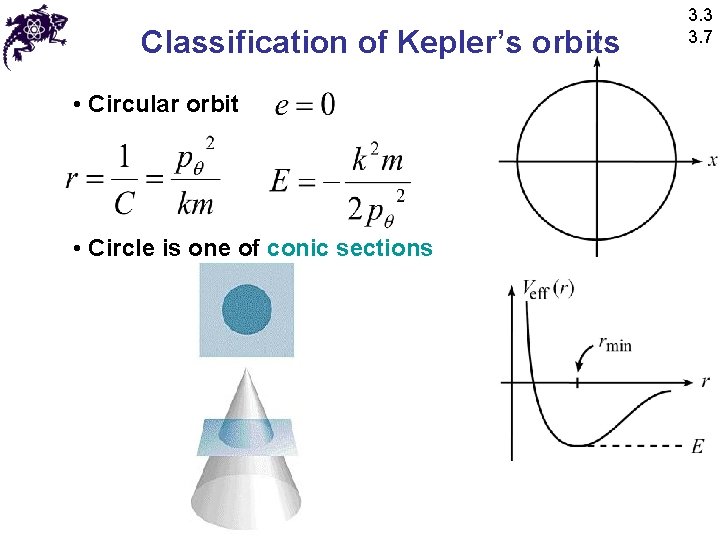

Classification of Kepler’s orbits • Effective potential for the attractive Kepler case: • The simplest case • Circular orbit 3. 3 3. 7

Classification of Kepler’s orbits • Circular orbit • Circle is one of conic sections 3. 3 3. 7

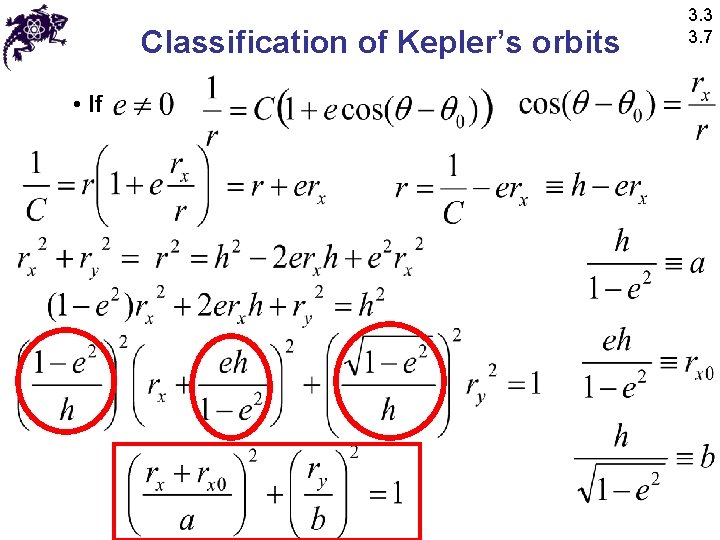

Classification of Kepler’s orbits • If 3. 3 3. 7

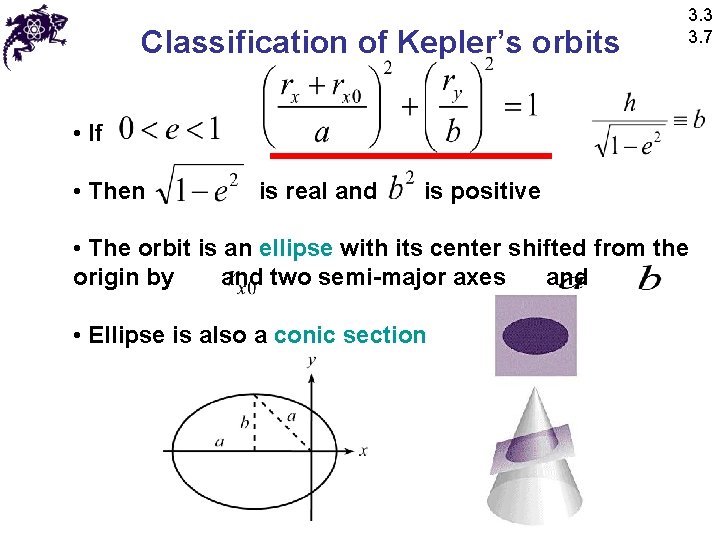

Classification of Kepler’s orbits 3. 3 3. 7 • If • Then is real and is positive • The orbit is an ellipse with its center shifted from the origin by and two semi-major axes and • Ellipse is also a conic section

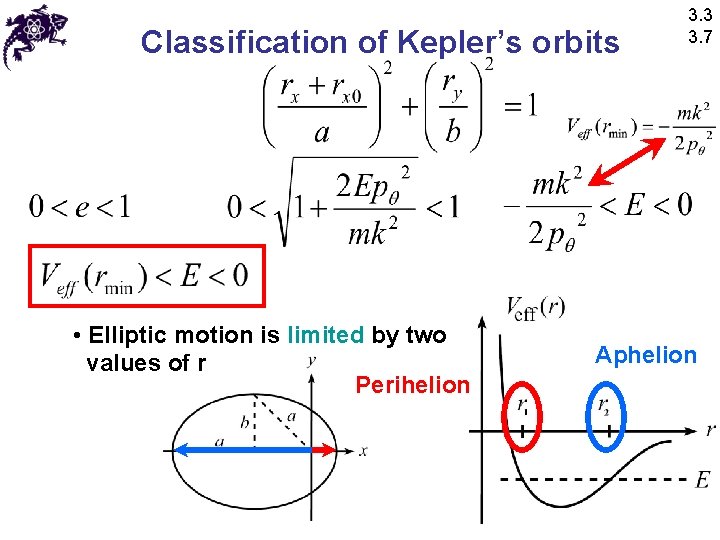

Classification of Kepler’s orbits • Elliptic motion is limited by two values of r Perihelion 3. 3 3. 7 Aphelion

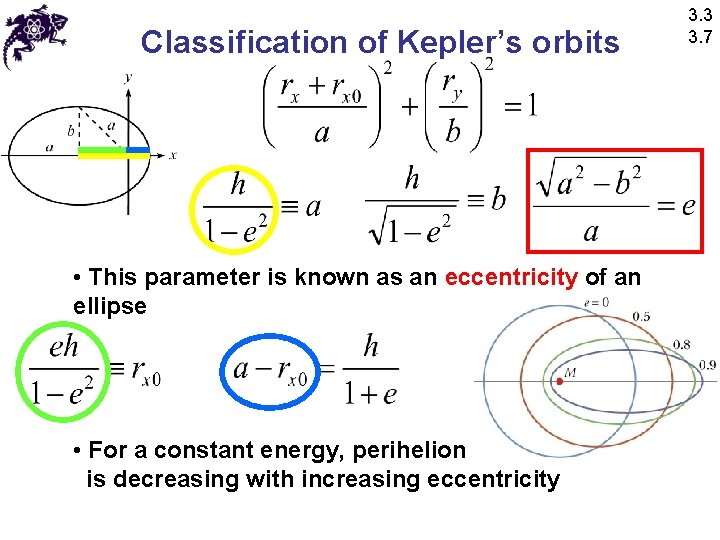

Classification of Kepler’s orbits • This parameter is known as an eccentricity of an ellipse • For a constant energy, perihelion is decreasing with increasing eccentricity 3. 3 3. 7

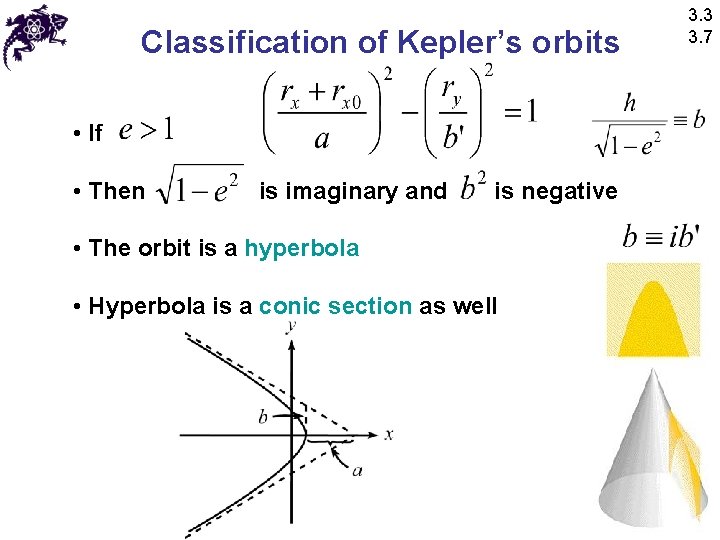

Classification of Kepler’s orbits • If • Then is imaginary and is negative • The orbit is a hyperbola • Hyperbola is a conic section as well 3. 3 3. 7

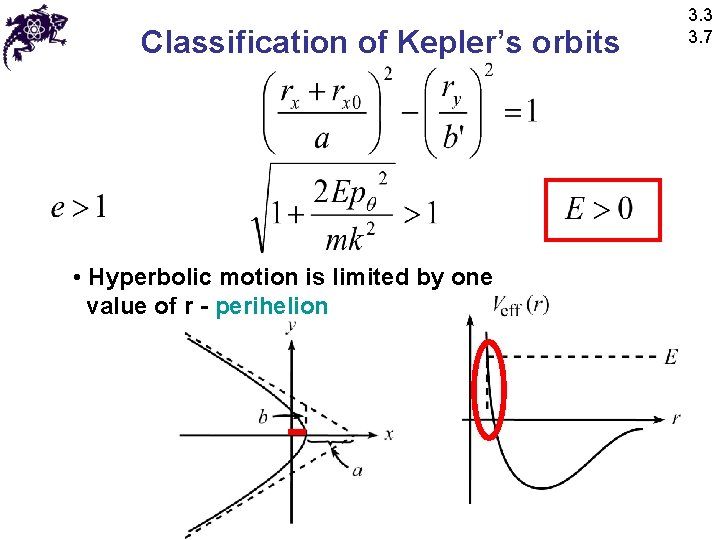

Classification of Kepler’s orbits • Hyperbolic motion is limited by one value of r - perihelion 3. 3 3. 7

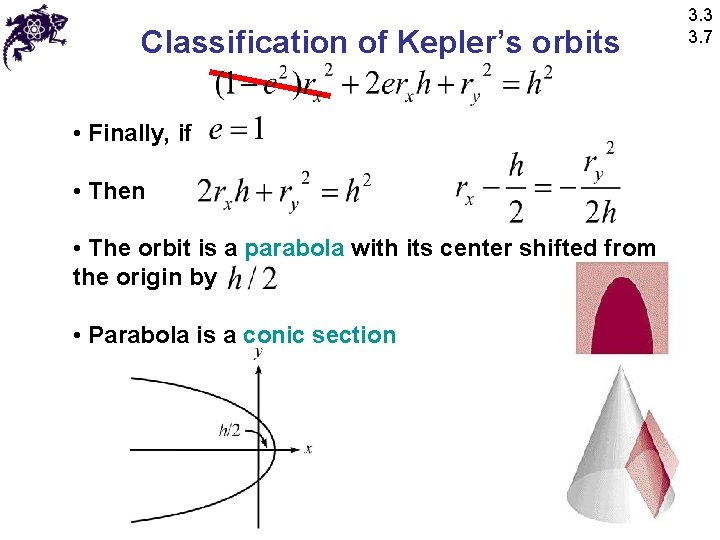

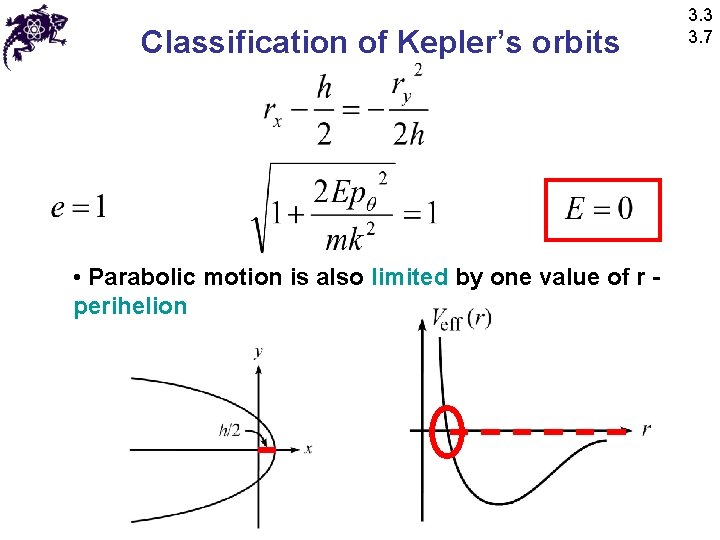

Classification of Kepler’s orbits • Finally, if • Then • The orbit is a parabola with its center shifted from the origin by • Parabola is a conic section 3. 3 3. 7

Classification of Kepler’s orbits • Parabolic motion is also limited by one value of r perihelion 3. 3 3. 7

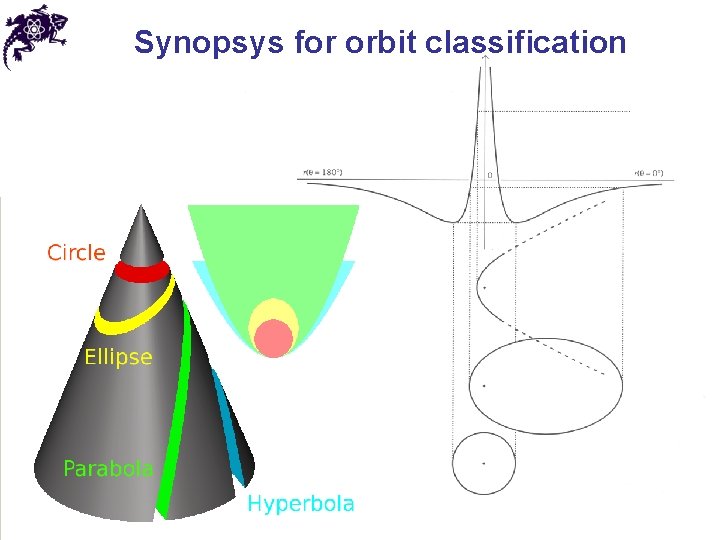

Synopsys for orbit classification

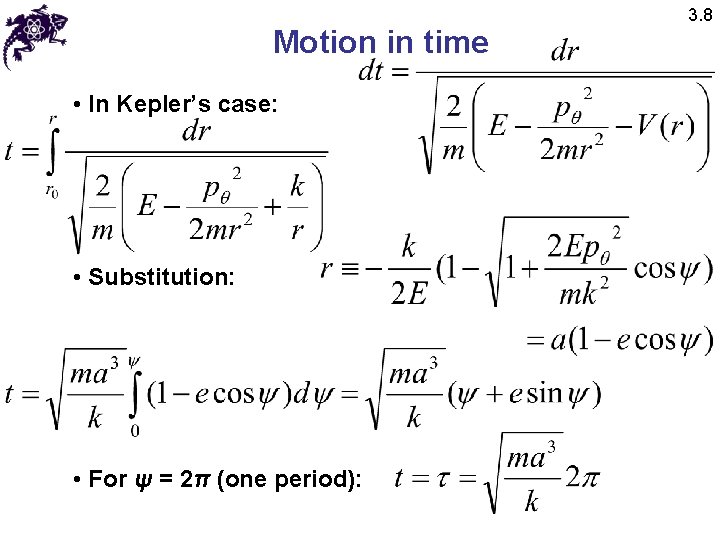

Motion in time • In Kepler’s case: • Substitution: • For ψ = 2π (one period): 3. 8

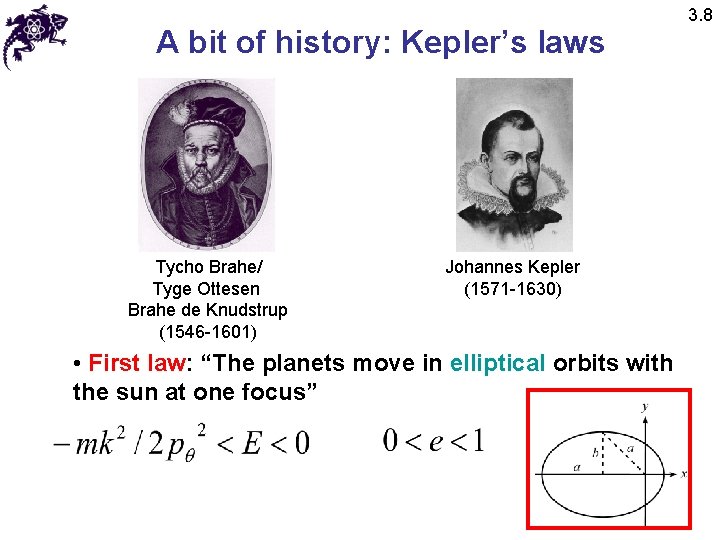

A bit of history: Kepler’s laws Tycho Brahe/ Tyge Ottesen Brahe de Knudstrup (1546 -1601) Johannes Kepler (1571 -1630) • First law: “The planets move in elliptical orbits with the sun at one focus” 3. 8

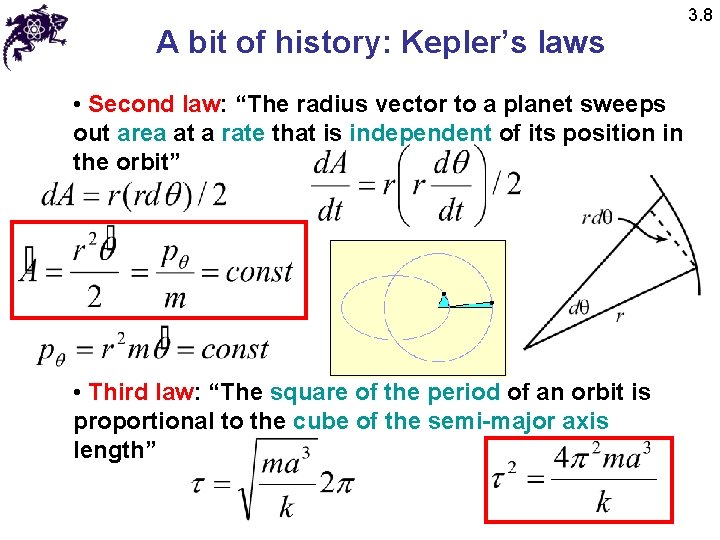

A bit of history: Kepler’s laws • Second law: “The radius vector to a planet sweeps out area at a rate that is independent of its position in the orbit” • Third law: “The square of the period of an orbit is proportional to the cube of the semi-major axis length” 3. 8

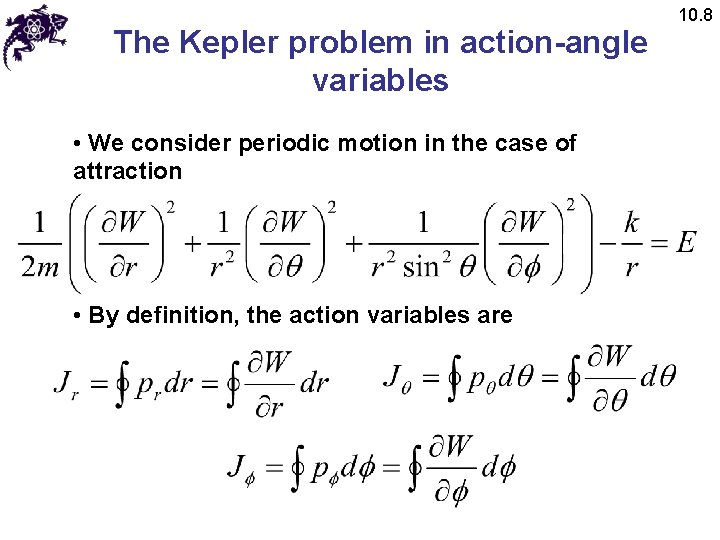

The Kepler problem in action-angle variables • We consider periodic motion in the case of attraction • By definition, the action variables are 10. 8

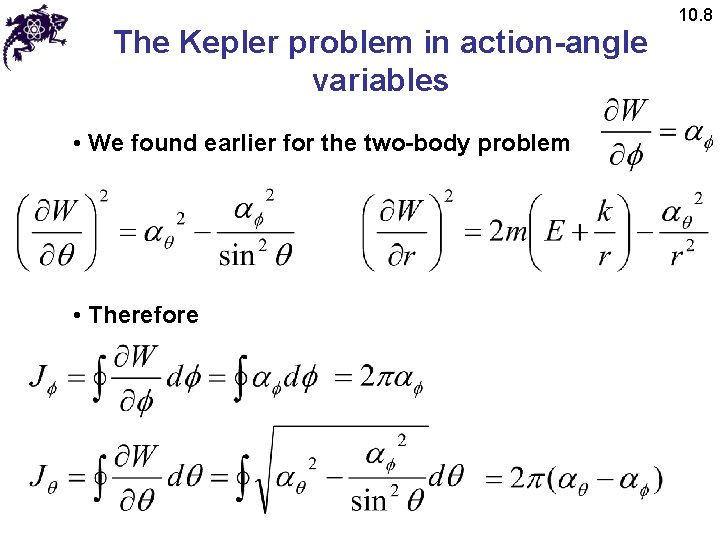

The Kepler problem in action-angle variables • We found earlier for the two-body problem • Therefore 10. 8

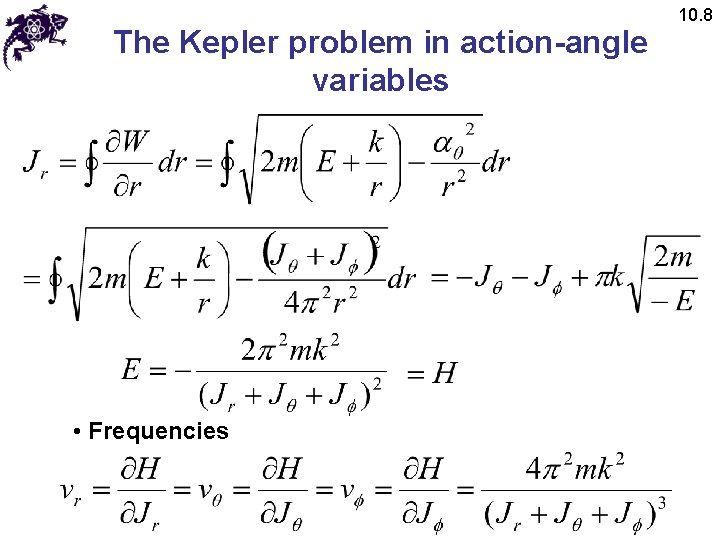

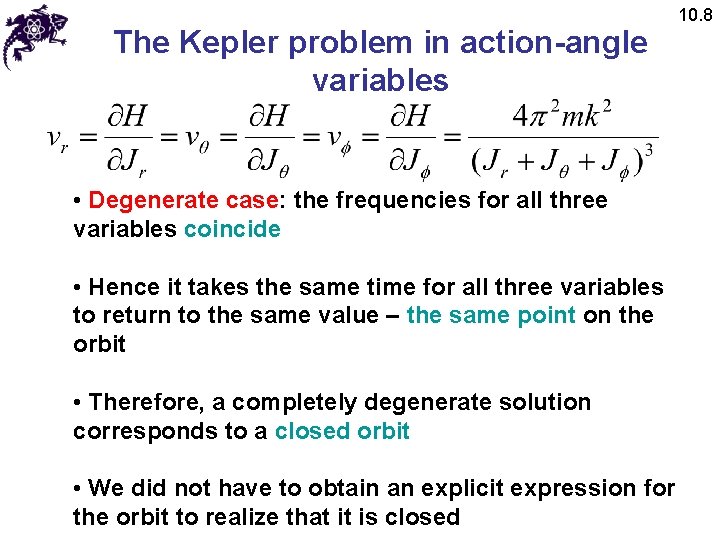

The Kepler problem in action-angle variables • Frequencies 10. 8

The Kepler problem in action-angle variables • Degenerate case: the frequencies for all three variables coincide • Hence it takes the same time for all three variables to return to the same value – the same point on the orbit • Therefore, a completely degenerate solution corresponds to a closed orbit • We did not have to obtain an explicit expression for the orbit to realize that it is closed 10. 8

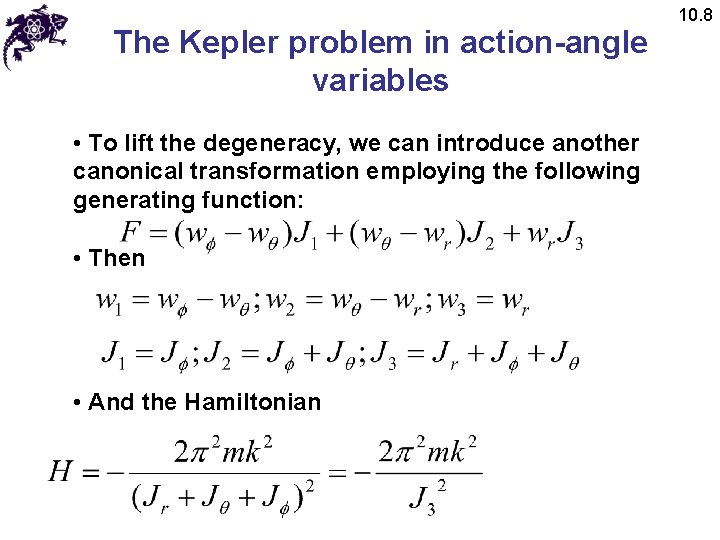

The Kepler problem in action-angle variables • To lift the degeneracy, we can introduce another canonical transformation employing the following generating function: • Then • And the Hamiltonian 10. 8

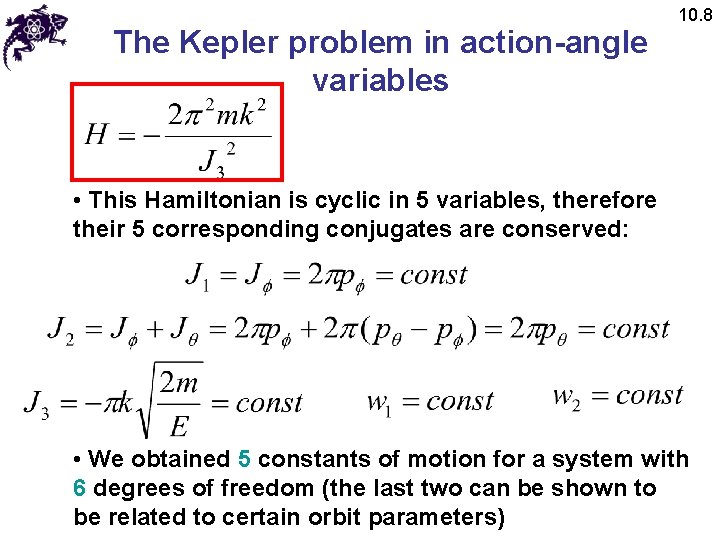

The Kepler problem in action-angle variables 10. 8 • This Hamiltonian is cyclic in 5 variables, therefore their 5 corresponding conjugates are conserved: • We obtained 5 constants of motion for a system with 6 degrees of freedom (the last two can be shown to be related to certain orbit parameters)

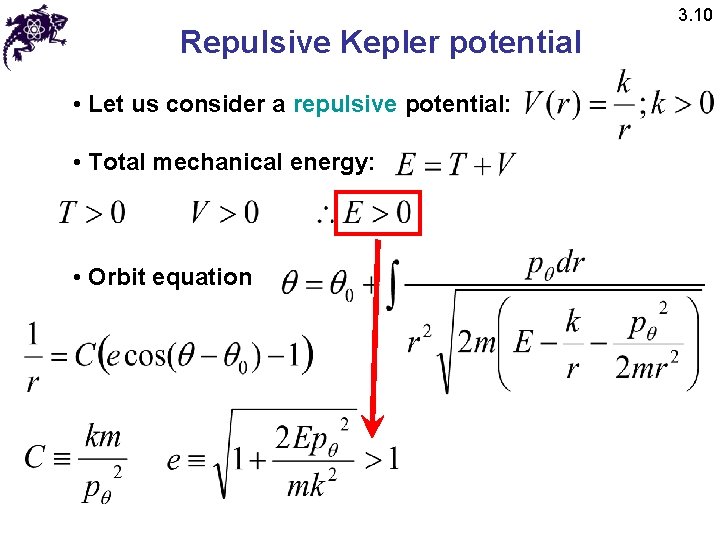

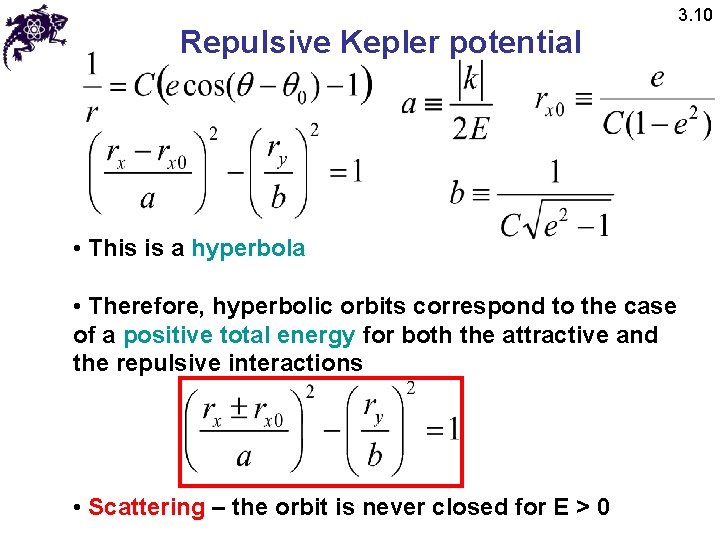

Repulsive Kepler potential • Let us consider a repulsive potential: • Total mechanical energy: • Orbit equation 3. 10

Repulsive Kepler potential • This is a hyperbola • Therefore, hyperbolic orbits correspond to the case of a positive total energy for both the attractive and the repulsive interactions • Scattering – the orbit is never closed for E > 0 3. 10

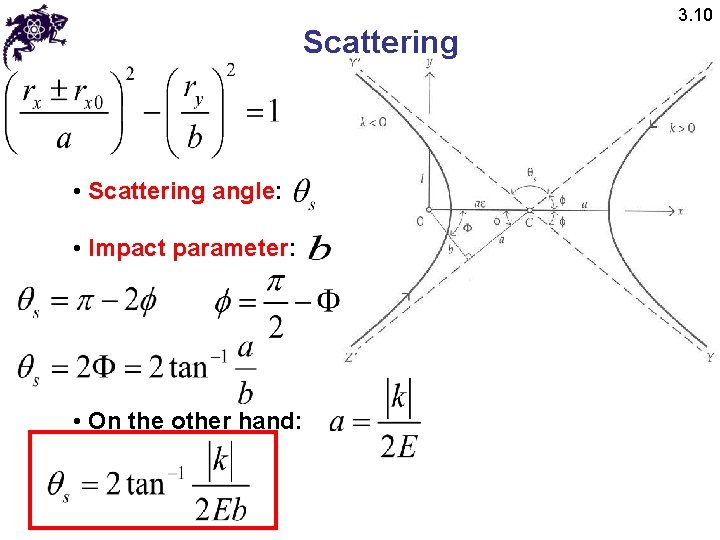

Scattering • Scattering angle: • Impact parameter: • On the other hand: 3. 10

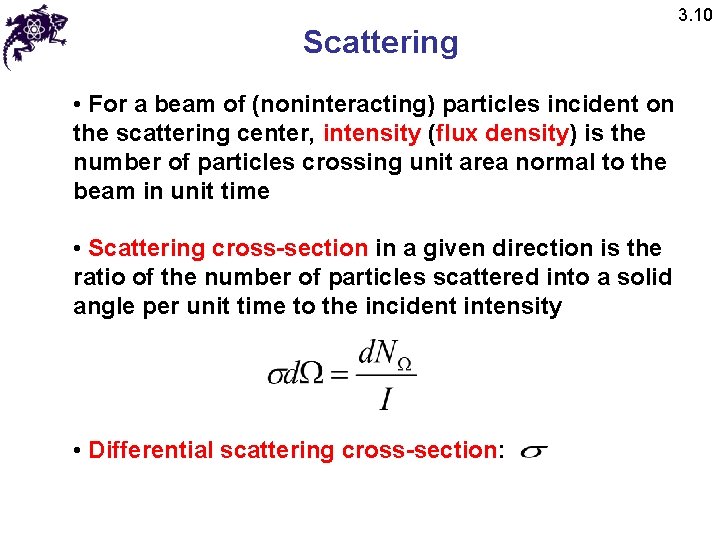

Scattering • For a beam of (noninteracting) particles incident on the scattering center, intensity (flux density) is the number of particles crossing unit area normal to the beam in unit time • Scattering cross-section in a given direction is the ratio of the number of particles scattered into a solid angle per unit time to the incident intensity • Differential scattering cross-section: 3. 10

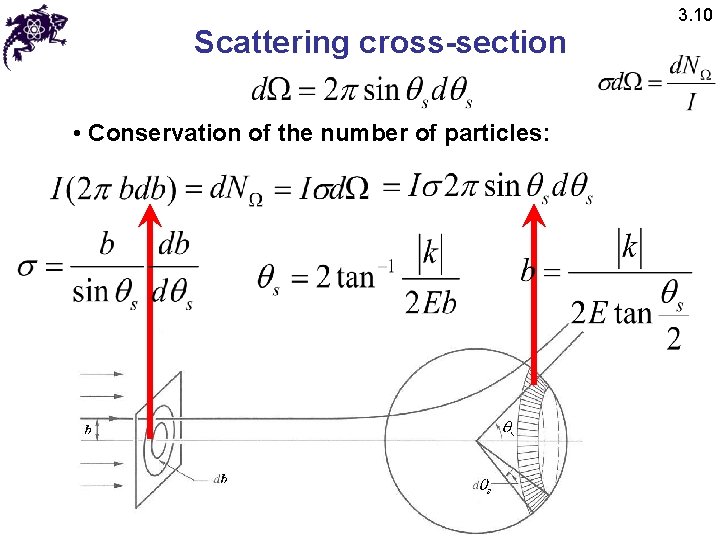

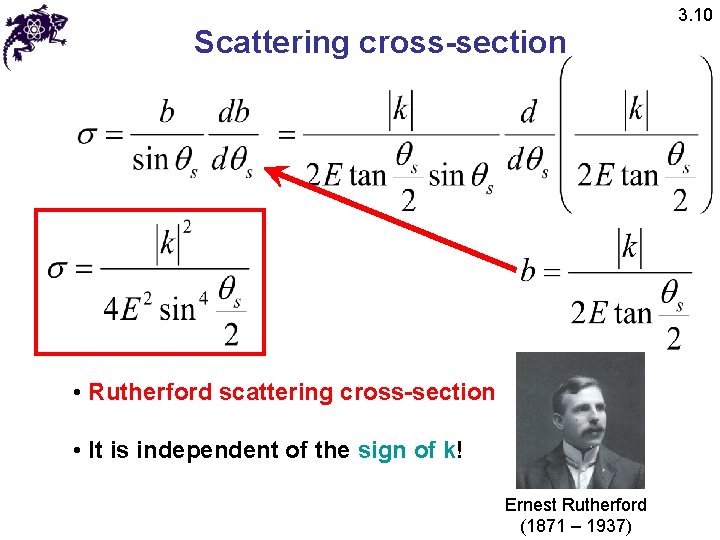

Scattering cross-section • Conservation of the number of particles: 3. 10

Scattering cross-section • Rutherford scattering cross-section • It is independent of the sign of k! Ernest Rutherford (1871 – 1937) 3. 10

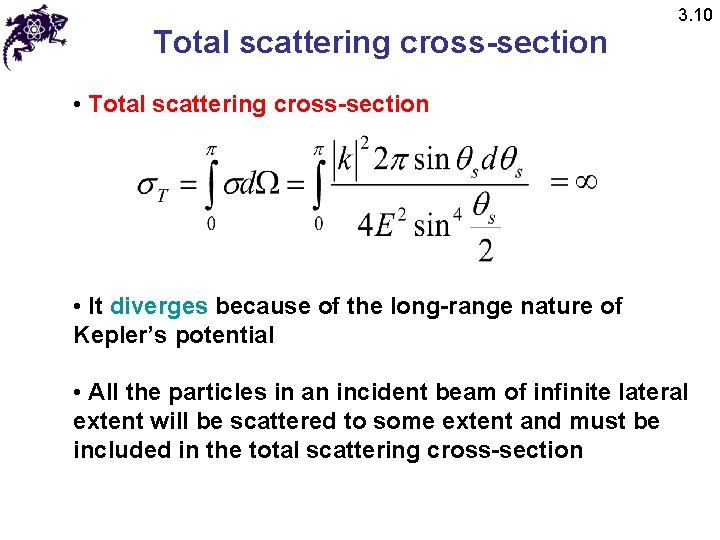

Total scattering cross-section 3. 10 • Total scattering cross-section • It diverges because of the long-range nature of Kepler’s potential • All the particles in an incident beam of infinite lateral extent will be scattered to some extent and must be included in the total scattering cross-section

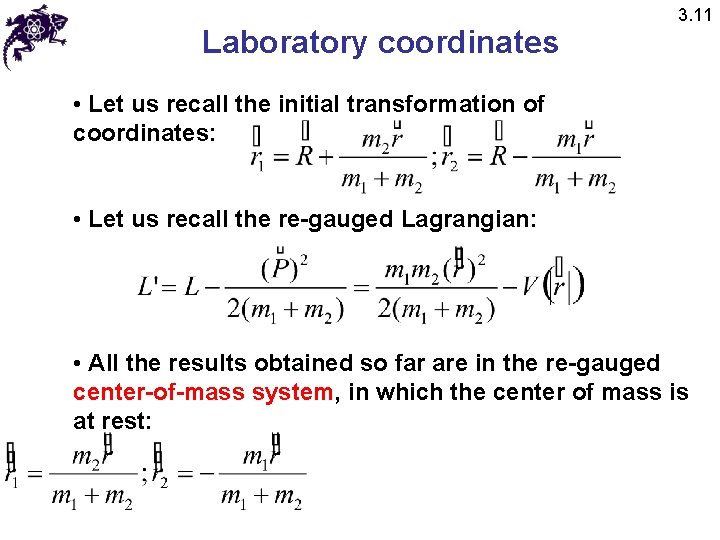

Laboratory coordinates 3. 11 • Let us recall the initial transformation of coordinates: • Let us recall the re-gauged Lagrangian: • All the results obtained so far are in the re-gauged center-of-mass system, in which the center of mass is at rest:

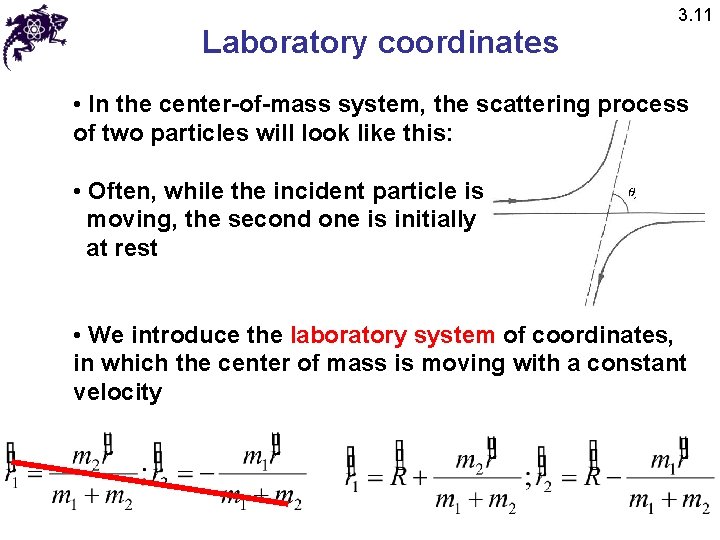

Laboratory coordinates 3. 11 • In the center-of-mass system, the scattering process of two particles will look like this: • Often, while the incident particle is moving, the second one is initially at rest • We introduce the laboratory system of coordinates, in which the center of mass is moving with a constant velocity

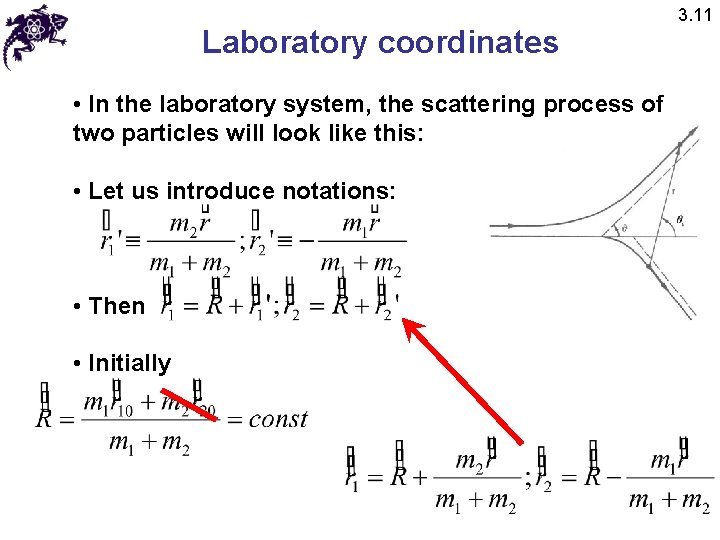

Laboratory coordinates • In the laboratory system, the scattering process of two particles will look like this: • Let us introduce notations: • Then • Initially 3. 11

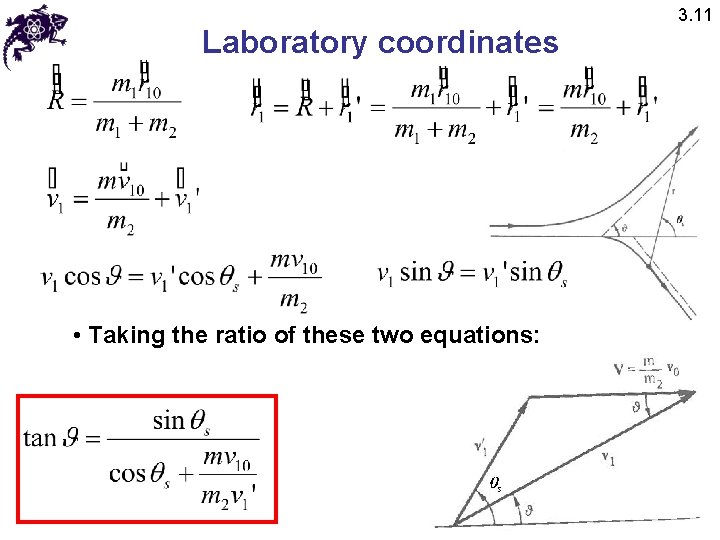

Laboratory coordinates • Taking the ratio of these two equations: 3. 11

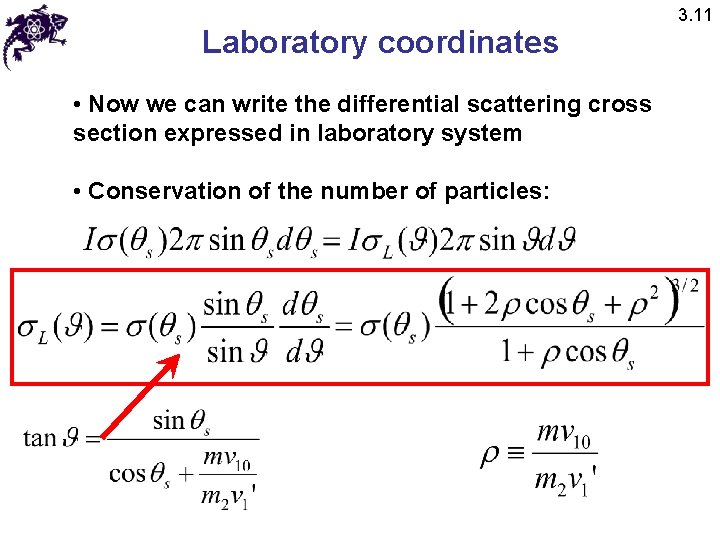

Laboratory coordinates • Now we can write the differential scattering cross section expressed in laboratory system • Conservation of the number of particles: 3. 11

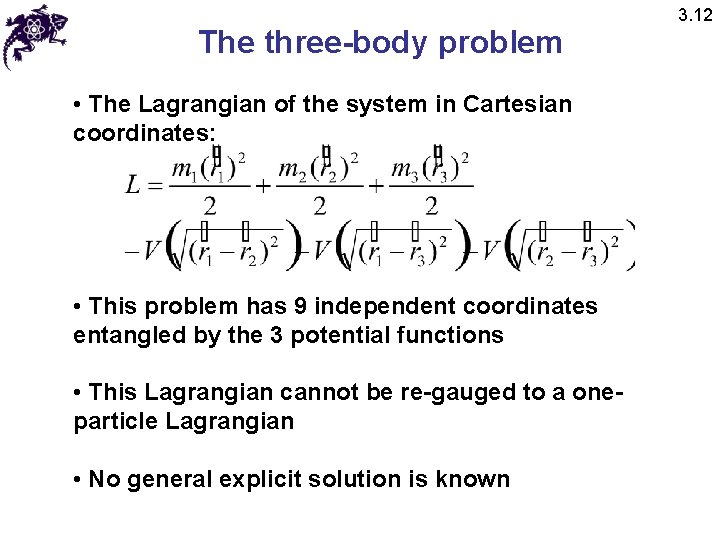

The three-body problem • The Lagrangian of the system in Cartesian coordinates: • This problem has 9 independent coordinates entangled by the 3 potential functions • This Lagrangian cannot be re-gauged to a oneparticle Lagrangian • No general explicit solution is known 3. 12

The three-body problem 3. 12 • Constants of motion (not independent): total energy, three components of the center of mass linear and angular momenta • If the three objects are allowed to move freely in 3 D the orbits become very complex and sensitive to initial conditions • Even after fixing positions of two particles and letting the third particle move in a plane, the orbit still can not be found explicitly

- Slides: 63