The structure of the Shilluk verb paradigm Bert

The structure of the Shilluk verb paradigm Bert Remijsen Otto Gwado Ayoker University of Edinburgh 1

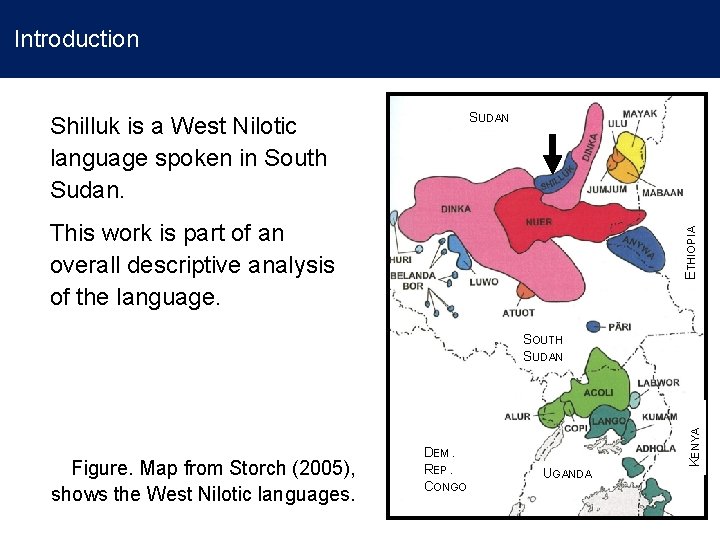

Introduction SUDAN Shilluk is a West Nilotic language spoken in South Sudan. ETHIOPIA This work is part of an overall descriptive analysis of the language. Figure. Map from Storch (2005), shows the West Nilotic languages. DEM. REP. CONGO KENYA SOUTH SUDAN UGANDA 2

Introduction The question: What is the morphological structure of Shilluk transitive verbs, and how does it interact with the syntax of the clause? Challenge / opportunity: Lots of stem-internal morphology, especially in terms of tone: 3

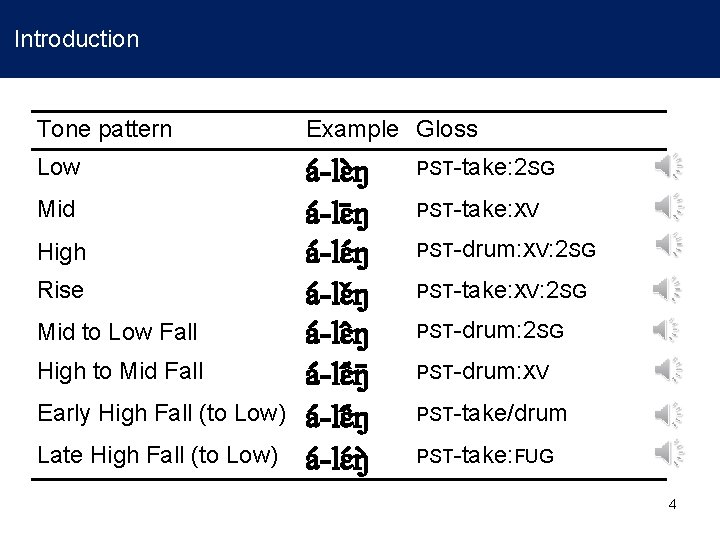

Introduction Tone pattern Example Gloss Low a -lɛ ŋ a -lɛ ŋ Mid High Rise Mid to Low Fall High to Mid Fall Early High Fall (to Low) Late High Fall (to Low) PST-take: 2 SG PST-take: XV PST-drum: XV: 2 SG PST-take: XV: 2 SG PST-drum: XV PST-take/drum PST-take: FUG 4

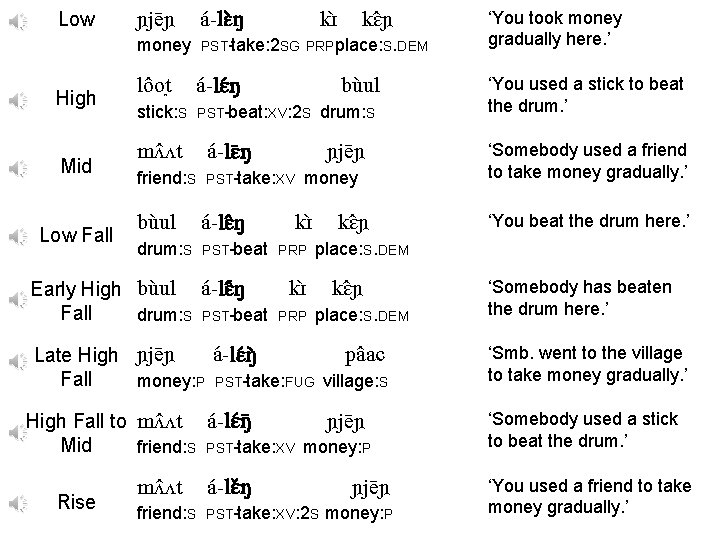

Low High Mid Low Fall ɲje ɲ a -lɛ ŋ kɪ money PST-take: 2 SG PRPplace: S. DEM lo ot a -lɛ ŋ stick: S PST-beat: XV: 2 S bu ul mʌ ʌt a -lɛ ŋ friend: S PST-take: XV drum: S ɲje ɲ money bu ul a -lɛ ŋ drum: S PST-beat PRP Early High bu ul a -lɛ ŋ Fall drum: S PST-beat kɛ ɲ kɪ kɛ ɲ place: S. DEM a -lɛ ŋ pa ac Late High ɲje ɲ Fall money: P PST-take: FUG village: S ɲje ɲ High Fall to mʌ ʌt a -lɛ ŋ Mid friend: S PST-take: XV money: P Rise ‘You used a stick to beat the drum. ’ ‘Somebody used a friend to take money gradually. ’ ‘You beat the drum here. ’ place: S. DEM kɪ PRP ‘You took money gradually here. ’ mʌ ʌt a -lɛ ŋ friend: S PST-take: XV: 2 S ɲje ɲ money: P ‘Somebody has beaten the drum here. ’ ‘Smb. went to the village to take money gradually. ’ ‘Somebody used a stick to beat the drum. ’ ‘You used a friend to take money gradually. ’

Shilluk verbs presents many morphological operations marking voice (semantic role of core arguments) and valency (number of core arguments) 6

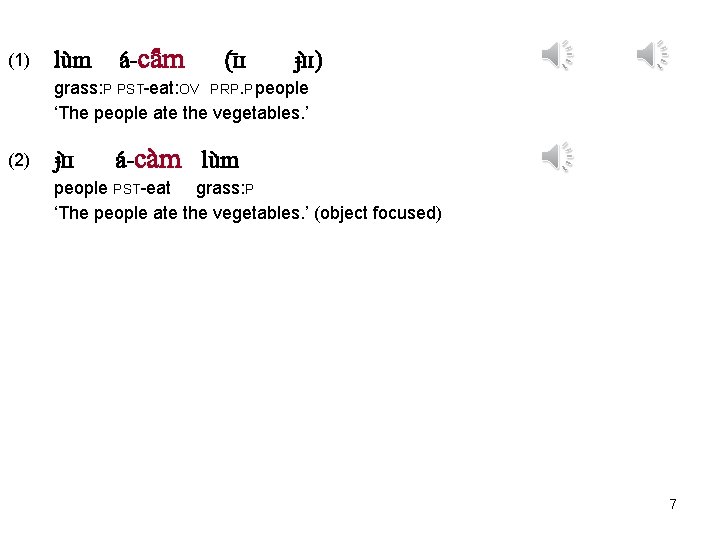

(1) lu m a -ca m (ɪ ɪ ɟɪ ɪ) grass: P PST-eat: OV PRP. P people ‘The people ate the vegetables. ’ (2) ɟɪ ɪ a -ca m lu m people PST-eat grass: P ‘The people ate the vegetables. ’ (object focused) 7

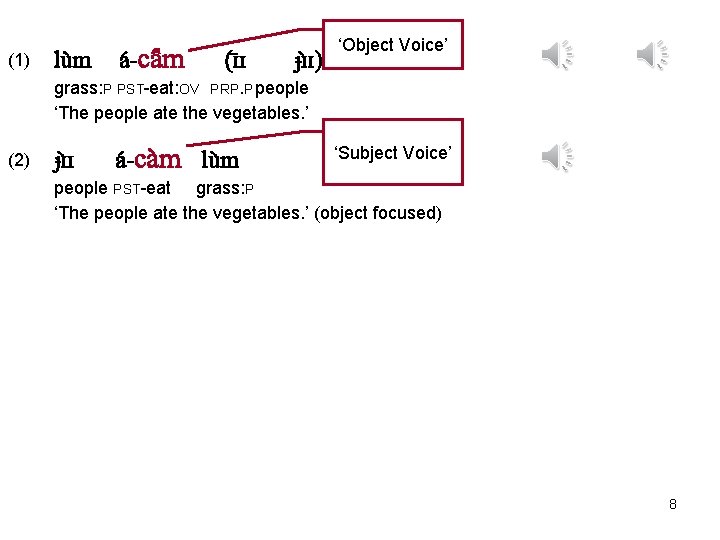

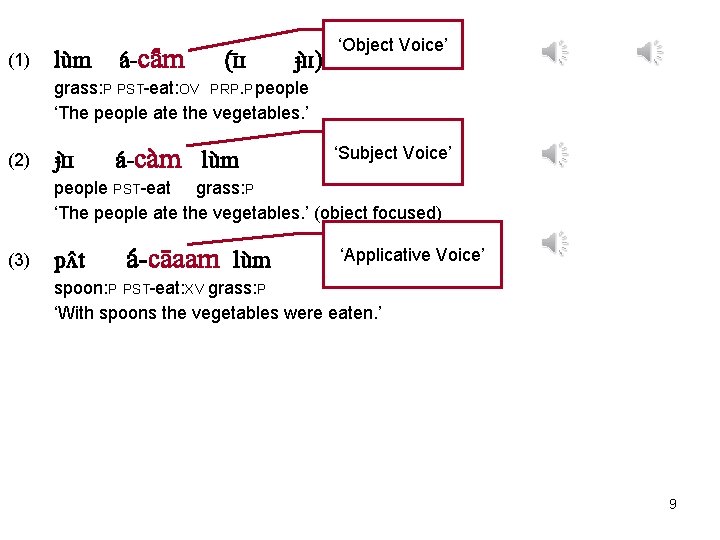

(1) lu m a -ca m (ɪ ɪ ɟɪ ɪ) ‘Object Voice’ grass: P PST-eat: OV PRP. P people ‘The people ate the vegetables. ’ (2) ɟɪ ɪ a -ca m lu m ‘Subject Voice’ people PST-eat grass: P ‘The people ate the vegetables. ’ (object focused) 8

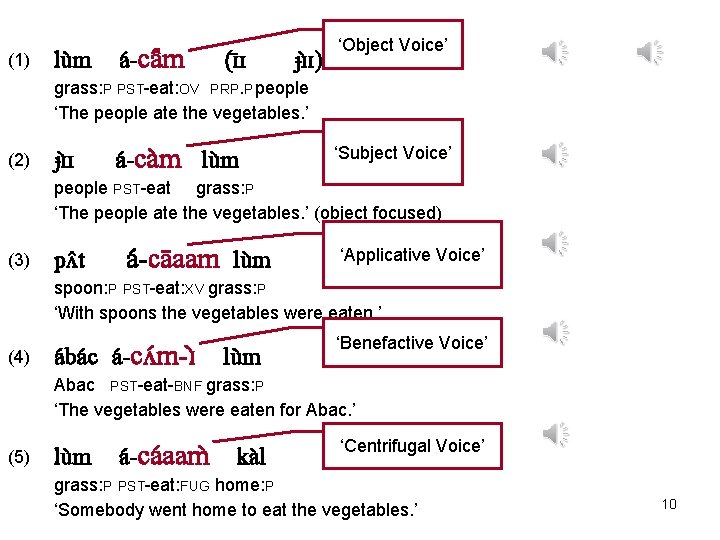

(1) lu m a -ca m (ɪ ɪ ɟɪ ɪ) ‘Object Voice’ grass: P PST-eat: OV PRP. P people ‘The people ate the vegetables. ’ (2) ɟɪ ɪ a -ca m lu m ‘Subject Voice’ people PST-eat grass: P ‘The people ate the vegetables. ’ (object focused) (3) pʌ t a -ca aam lu m ‘Applicative Voice’ spoon: P PST-eat: XV grass: P ‘With spoons the vegetables were eaten. ’ 9

(1) lu m a -ca m (ɪ ɪ ɟɪ ɪ) ‘Object Voice’ grass: P PST-eat: OV PRP. P people ‘The people ate the vegetables. ’ (2) ɟɪ ɪ a -ca m lu m ‘Subject Voice’ people PST-eat grass: P ‘The people ate the vegetables. ’ (object focused) (3) pʌ t a -ca aam lu m ‘Applicative Voice’ spoon: P PST-eat: XV grass: P ‘With spoons the vegetables were eaten. ’ (4) a ba c a -cʌ m-ɪ lu m ‘Benefactive Voice’ Abac PST-eat-BNF grass: P ‘The vegetables were eaten for Abac. ’ (5) lu m a -ca aam ka l ‘Centrifugal Voice’ grass: P PST-eat: FUG home: P ‘Somebody went home to eat the vegetables. ’ 10

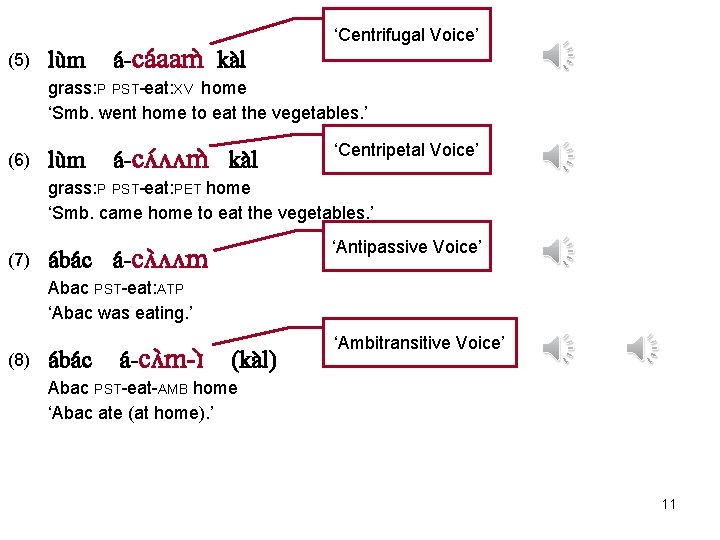

(5) lu m a -ca aam ka l ‘Centrifugal Voice’ grass: P PST-eat: XV home ‘Smb. went home to eat the vegetables. ’ (6) lu m a -cʌ ʌʌm ka l ‘Centripetal Voice’ grass: P PST-eat: PET home ‘Smb. came home to eat the vegetables. ’ (7) a ba c a -cʌ ʌʌm ‘Antipassive Voice’ Abac PST-eat: ATP ‘Abac was eating. ’ (8) a ba c a -cʌ m-ɪ (ka l) ‘Ambitransitive Voice’ Abac PST-eat-AMB home ‘Abac ate (at home). ’ 11

Morphological operations on Shilluk transitive verbs • Shilluk verbs have many morphological operations marking voice and valency. • The system is characterised by head-marking: the relation between the head of the predicate is marked on the verb, not on the noun-phrase arguments. • How is the paradigm structured? • This question is left open in earlier work (Remijsen, Miller-Naudé & Gilley 2016), which focused on establishing the patterns of morphological exponence. 12

How is the paradigm structured? 13

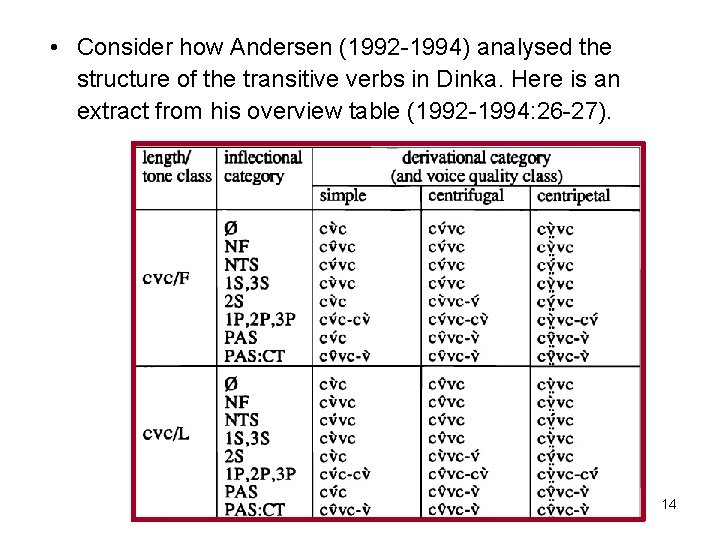

• Consider how Andersen (1992 -1994) analysed the structure of the transitive verbs in Dinka. Here is an extract from his overview table (1992 -1994: 26 -27). 14

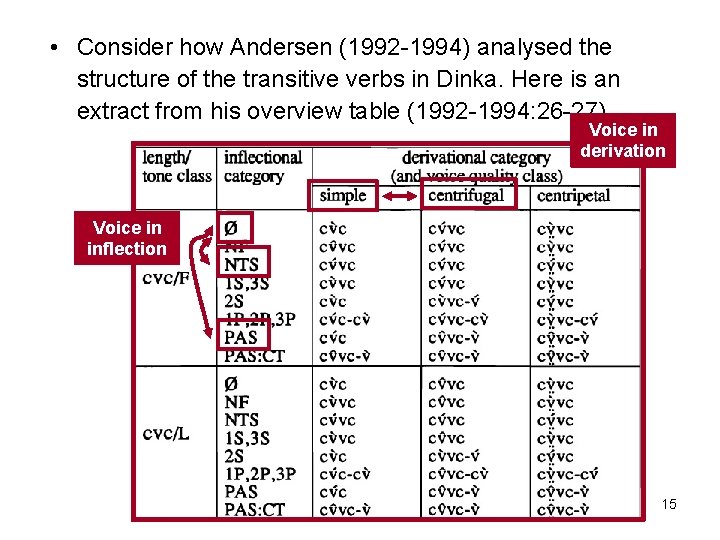

• Consider how Andersen (1992 -1994) analysed the structure of the transitive verbs in Dinka. Here is an extract from his overview table (1992 -1994: 26 -27). Voice in derivation Voice in inflection 15

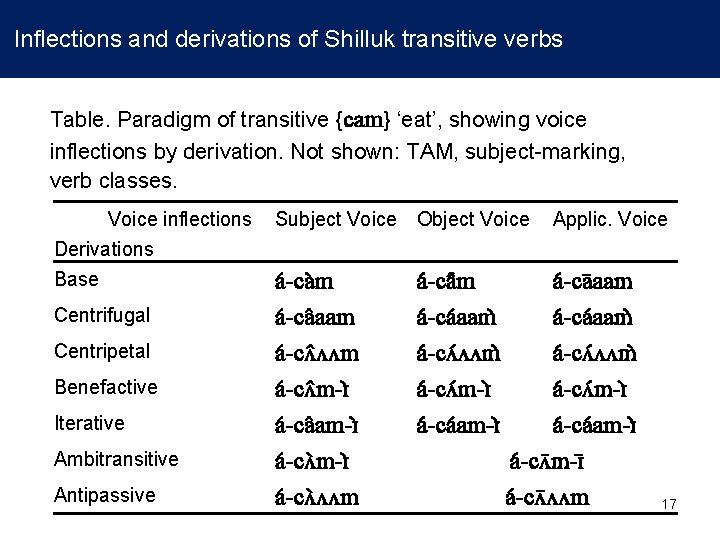

Inflections and derivations of Shilluk transitive verbs • Important insight from Andersen (1992 -1994): operations that recur across derivations are inflectional. • For example, the operation NTS (non-topical subject) is to be interpreted as inflectional, because it combines with centrifugal and benefactive, just as it is found in the base paradigm. • In contrast, the operations of centrifugal and benefactive are best interpreted as derivations, because they come in a full set of inflections. • Applying this approach to Shilluk we get the following: 16

Inflections and derivations of Shilluk transitive verbs Table. Paradigm of transitive {cam} ‘eat’, showing voice inflections by derivation. Not shown: TAM, subject-marking, verb classes. Voice inflections Derivations Subject Voice Object Voice Base a -ca m a -ca aam a -cʌ ʌʌm a -cʌ m-ɪ a -ca am-ɪ a -cʌ ʌʌm Centrifugal Centripetal Benefactive Iterative Ambitransitive Antipassive a -ca m a -ca aam a -cʌ ʌʌm a -cʌ m-ɪ a -ca am-ɪ Applic. Voice a -ca aam a -cʌ ʌʌm a -cʌ m-ɪ a -ca am-ɪ a -cʌ ʌʌm 17

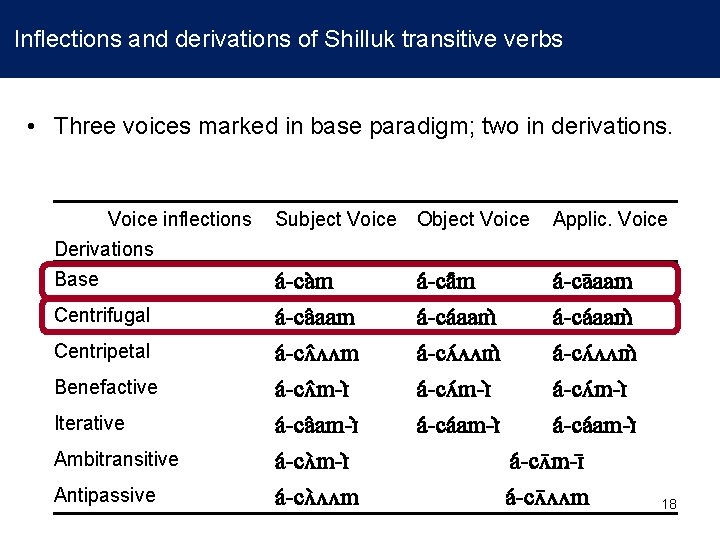

Inflections and derivations of Shilluk transitive verbs • Three voices marked in base paradigm; two in derivations. Voice inflections Derivations Subject Voice Object Voice Base a -ca m a -ca aam a -cʌ ʌʌm a -cʌ m-ɪ a -ca am-ɪ a -cʌ ʌʌm Centrifugal Centripetal Benefactive Iterative Ambitransitive Antipassive a -ca m a -ca aam a -cʌ ʌʌm a -cʌ m-ɪ a -ca am-ɪ Applic. Voice a -ca aam a -cʌ ʌʌm a -cʌ m-ɪ a -ca am-ɪ a -cʌ ʌʌm 18

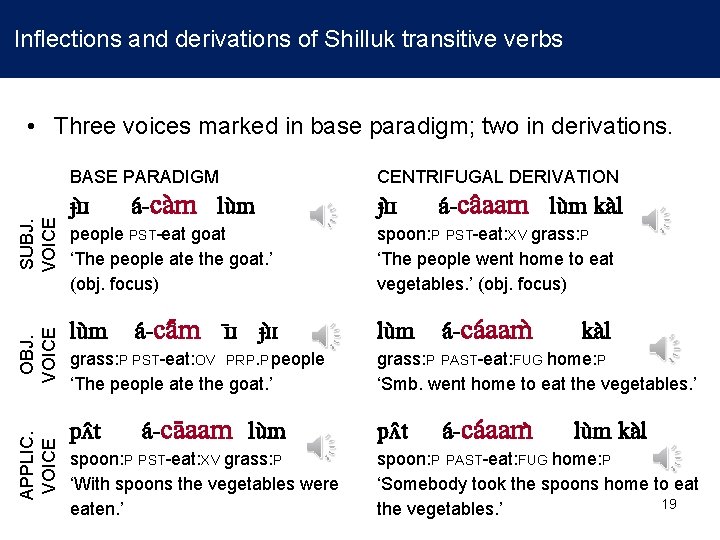

Inflections and derivations of Shilluk transitive verbs APPLIC. VOICE OBJ. VOICE SUBJ. VOICE • Three voices marked in base paradigm; two in derivations. BASE PARADIGM CENTRIFUGAL DERIVATION people PST-eat goat ‘The people ate the goat. ’ (obj. focus) spoon: P PST-eat: XV grass: P ‘The people went home to eat vegetables. ’ (obj. focus) ɟɪ ɪ lu m a -ca m ɪ ɪ ɟɪ ɪ grass: P PST-eat: OV PRP. P people ‘The people ate the goat. ’ pʌ t a -ca aam lu m spoon: P PST-eat: XV grass: P ‘With spoons the vegetables were eaten. ’ ɟɪ ɪ lu m a -ca aam lu m ka l a -ca aam ka l grass: P PAST-eat: FUG home: P ‘Smb. went home to eat the vegetables. ’ pʌ t a -ca aam lu m ka l spoon: P PAST-eat: FUG home: P ‘Somebody took the spoons home to eat 19 the vegetables. ’

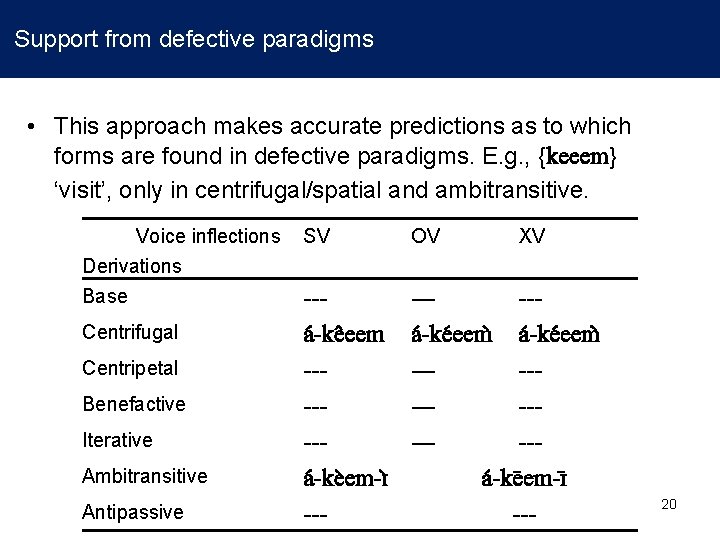

Support from defective paradigms • This approach makes accurate predictions as to which forms are found in defective paradigms. E. g. , {keeem} ‘visit’, only in centrifugal/spatial and ambitransitive. Voice inflections Derivations SV OV Base --a -ke eem ------a -ke em-ɪ ----a -ke eem ------a -ke em-ɪ --- Centrifugal Centripetal Benefactive Iterative Ambitransitive Antipassive XV 20

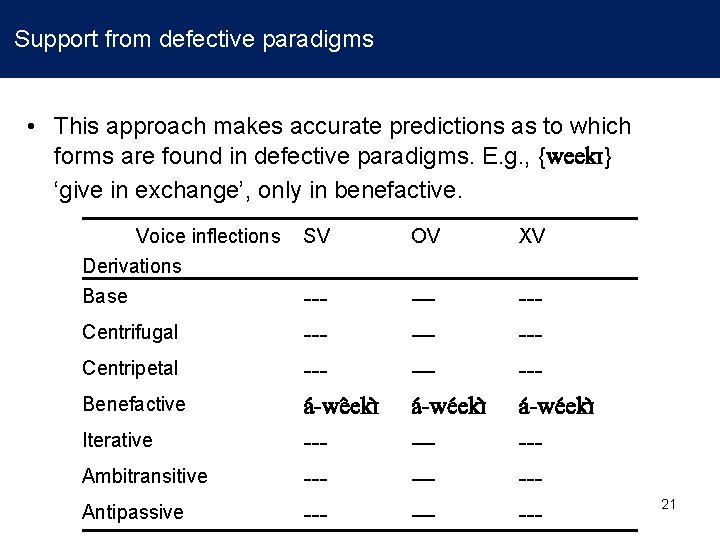

Support from defective paradigms • This approach makes accurate predictions as to which forms are found in defective paradigms. E. g. , {weekɪ} ‘give in exchange’, only in benefactive. Voice inflections Derivations SV OV XV Base ------a -we ekɪ ------- Centrifugal Centripetal Benefactive Iterative Ambitransitive Antipassive 21

Layering stem-internal morphology 22

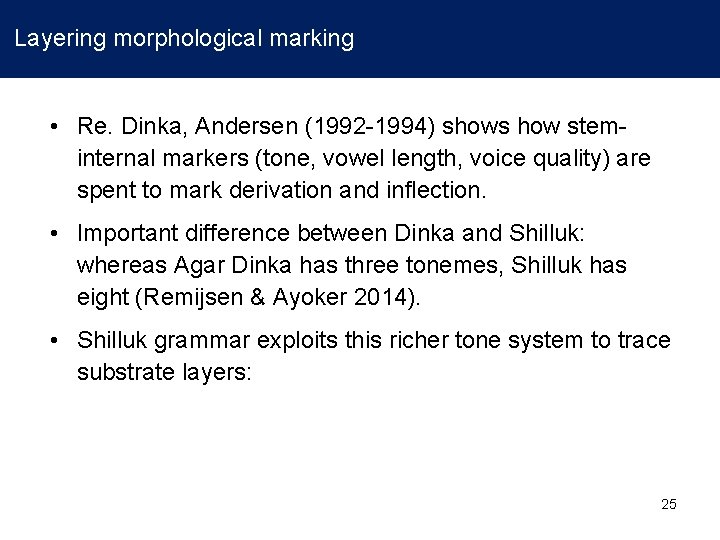

Layering morphological marking • Re. Dinka, Andersen (1992 -1994) shows how steminternal markers (tone, vowel length, voice quality) are spent to mark derivation and inflection: 23

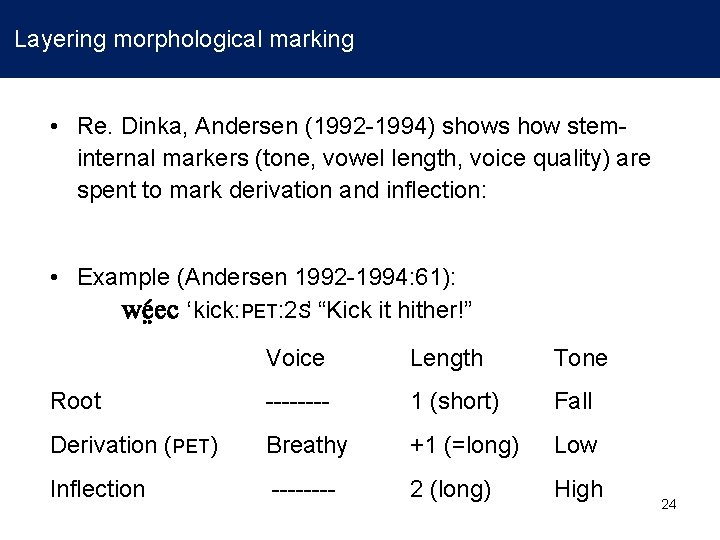

Layering morphological marking • Re. Dinka, Andersen (1992 -1994) shows how steminternal markers (tone, vowel length, voice quality) are spent to mark derivation and inflection: • Example (Andersen 1992 -1994: 61): we ec ‘kick: PET: 2 S’ “Kick it hither!” Voice Length Tone Root ---- 1 (short) Fall Derivation (PET) Breathy +1 (=long) Low Inflection ---- 2 (long) High 24

Layering morphological marking • Re. Dinka, Andersen (1992 -1994) shows how steminternal markers (tone, vowel length, voice quality) are spent to mark derivation and inflection. • Important difference between Dinka and Shilluk: whereas Agar Dinka has three tonemes, Shilluk has eight (Remijsen & Ayoker 2014). • Shilluk grammar exploits this richer tone system to trace substrate layers: 25

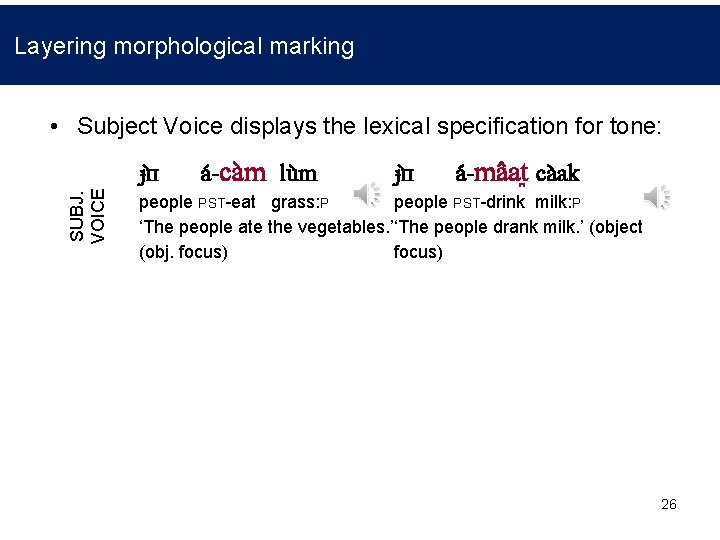

Layering morphological marking SUBJ. VOICE • Subject Voice displays the lexical specification for tone: ɟɪ ɪ a -ca m lu m ɟɪ ɪ a -ma at ca ak people PST-eat grass: P people PST-drink milk: P ‘The people ate the vegetables. ’‘The people drank milk. ’ (object (obj. focus) 26

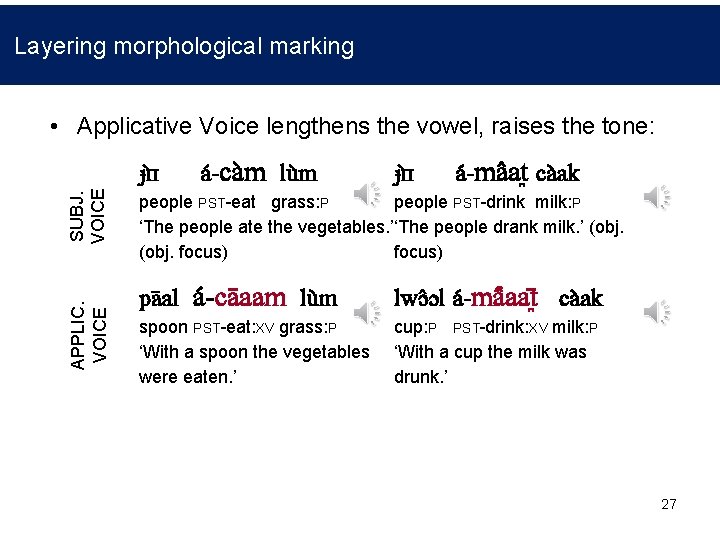

Layering morphological marking APPLIC. VOICE SUBJ. VOICE • Applicative Voice lengthens the vowel, raises the tone: ɟɪ ɪ a -ca m lu m ɟɪ ɪ a -ma at ca ak people PST-eat grass: P people PST-drink milk: P ‘The people ate the vegetables. ’‘The people drank milk. ’ (obj. focus) pa al a -ca aam lu m spoon PST-eat: XV grass: P ‘With a spoon the vegetables were eaten. ’ lwɔ ɔl a -ma aat ca ak cup: P PST-drink: XV milk: P ‘With a cup the milk was drunk. ’ 27

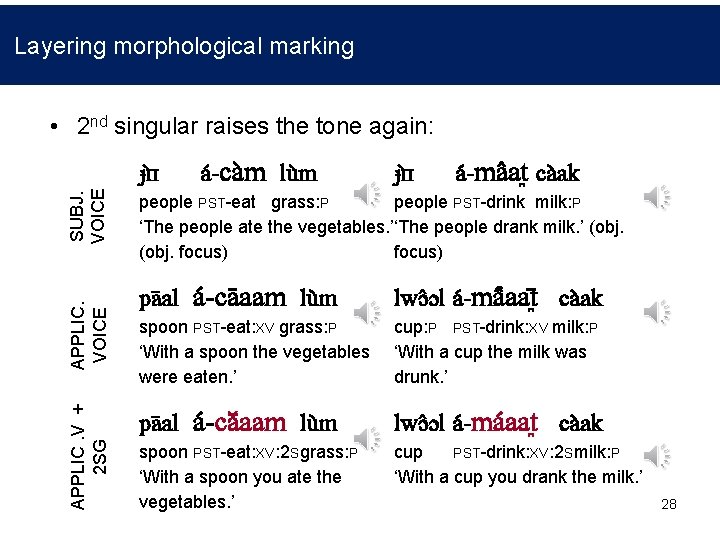

Layering morphological marking APPLIC. V + 2 SG APPLIC. VOICE SUBJ. VOICE • 2 nd singular raises the tone again: ɟɪ ɪ a -ca m lu m ɟɪ ɪ a -ma at ca ak people PST-eat grass: P people PST-drink milk: P ‘The people ate the vegetables. ’‘The people drank milk. ’ (obj. focus) pa al a -ca aam lu m lwɔ ɔl a -ma aat ca ak pa al a -ca aam lu m lwɔ ɔl a -ma aat ca ak spoon PST-eat: XV grass: P ‘With a spoon the vegetables were eaten. ’ spoon PST-eat: XV: 2 S grass: P ‘With a spoon you ate the vegetables. ’ cup: P PST-drink: XV milk: P ‘With a cup the milk was drunk. ’ cup PST-drink: XV: 2 S milk: P ‘With a cup you drank the milk. ’ 28

Layering morphological marking • Tonal exponence does not just overwrite the tonal exponence of layer(s) below, it combines with the substrate specifications in a compositional way. 29

Layering morphological marking • Tonal exponence does not just overwrite the tonal exponence of layer(s) below, it combines with the substrate specifications in a compositional way. • The high functional load of tone in the morphology is a key factor in the development of an timing contrast in high-falling contours (Remijsen & Ayoker 2014; cf. Blevins 2004). 30

The alignment of thematic subject and thematic object 31

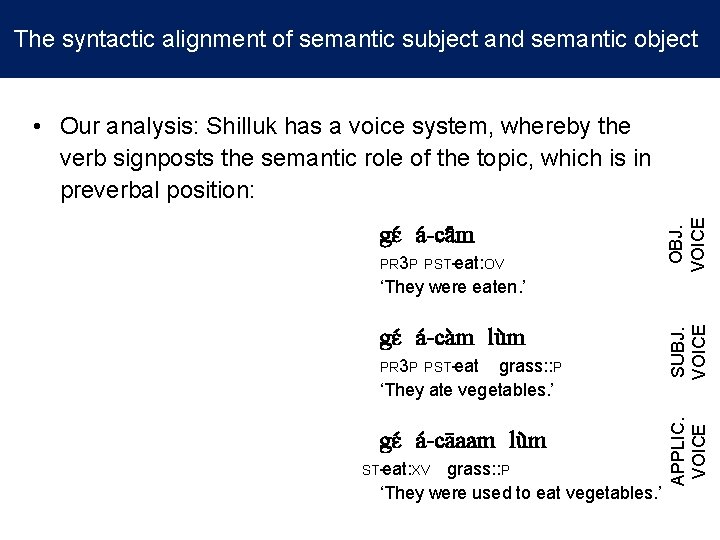

The syntactic alignment of semantic subject and semantic object • Our analysis: Shilluk has a voice system, whereby the verb signposts the semantic role of the topic, which is in preverbal position:

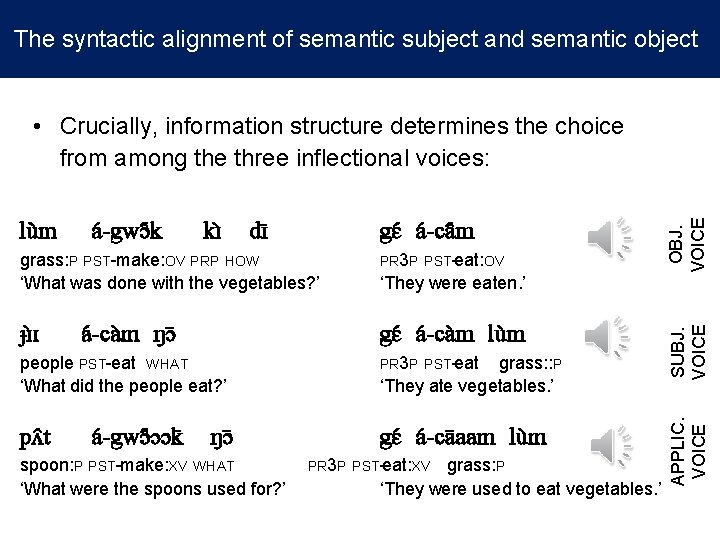

The syntactic alignment of semantic subject and semantic object kɪ dɪ gɛ a -ca m grass: P PST-make: OV PRP HOW ‘What was done with the vegetables? ’ PR 3 P PST-eat: OV ɟɪ ɪ gɛ a -ca m lu m a -ca m ŋɔ ‘They were eaten. ’ people PST-eat WHAT ‘What did the people eat? ’ PR 3 P PST-eat pʌ t gɛ a -ca aam lu m a -gwɔ ɔɔk ŋɔ spoon: P PST-make: XV WHAT ‘What were the spoons used for? ’ grass: : P ‘They ate vegetables. ’ PR 3 P PST-eat: XV grass: : P ‘They were used to eat vegetables. ’ SUBJ. VOICE a -gwɔ k APPLIC. VOICE lu m OBJ. VOICE • Our analysis: Shilluk has a voice system, whereby the verb signposts the semantic role of the topic, which is in preverbal position:

The syntactic alignment of semantic subject and semantic object kɪ dɪ gɛ a -ca m grass: P PST-make: OV PRP HOW ‘What was done with the vegetables? ’ PR 3 P PST-eat: OV ɟɪ ɪ gɛ a -ca m lu m a -ca m ŋɔ ‘They were eaten. ’ people PST-eat WHAT ‘What did the people eat? ’ PR 3 P PST-eat pʌ t gɛ a -ca aam lu m a -gwɔ ɔɔk ŋɔ spoon: P PST-make: XV WHAT ‘What were the spoons used for? ’ grass: : P ‘They ate vegetables. ’ PR 3 P PST-eat: XV grass: P ‘They were used to eat vegetables. ’ SUBJ. VOICE a -gwɔ k APPLIC. VOICE lu m OBJ. VOICE • Crucially, information structure determines the choice from among the three inflectional voices:

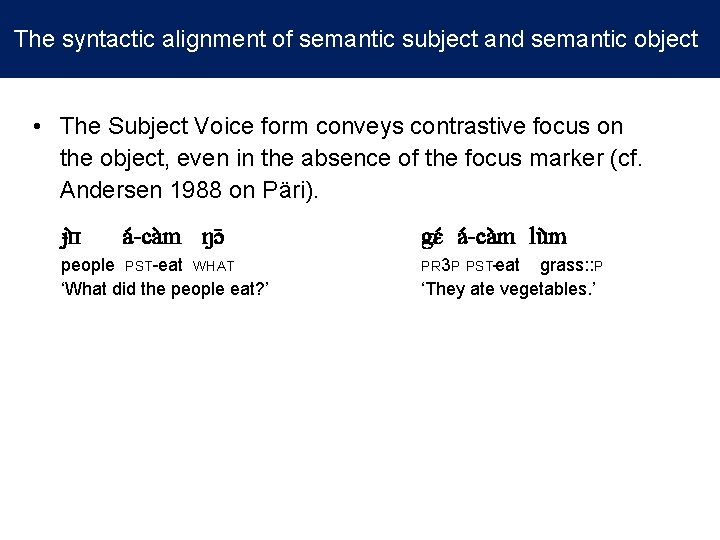

The syntactic alignment of semantic subject and semantic object • The Subject Voice form conveys contrastive focus on the object, even in the absence of the focus marker (cf. Andersen 1988 on Päri). ɟɪ ɪ a -ca m ŋɔ people PST-eat WHAT ‘What did the people eat? ’ gɛ a -ca m lu m PR 3 P PST-eat grass: : P ‘They ate vegetables. ’

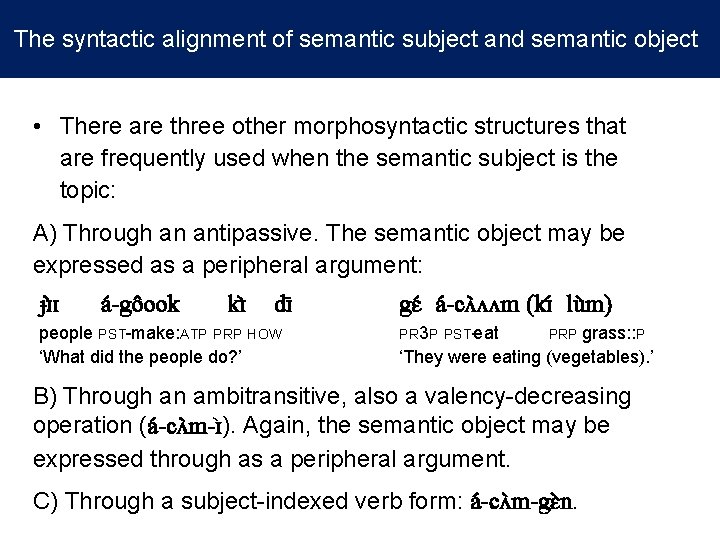

The syntactic alignment of semantic subject and semantic object • There are three other morphosyntactic structures that are frequently used when the semantic subject is the topic: A) Through an antipassive. The semantic object may be expressed as a peripheral argument: ɟɪ ɪ a -go ook kɪ dɪ people PST-make: ATP PRP HOW ‘What did the people do? ’ gɛ a -cʌ ʌʌm (kɪ lu m) PR 3 P PST-eat PRP grass: : P ‘They were eating (vegetables). ’ B) Through an ambitransitive, also a valency-decreasing operation (a -cʌ m-ɪ ). Again, the semantic object may be expressed through as a peripheral argument. C) Through a subject-indexed verb form: a -cʌ m-gɛ n.

Discussion 37

Discussion • Shilluk presents a voice system, whereby the verb signposts the semantic role of the topic, which is in preverbal position – cf. Dinka (Andersen 1991). • The notion of topic explains how discourse structure determines the choice between Object Voice, Subject Voice and Applicative Voice.

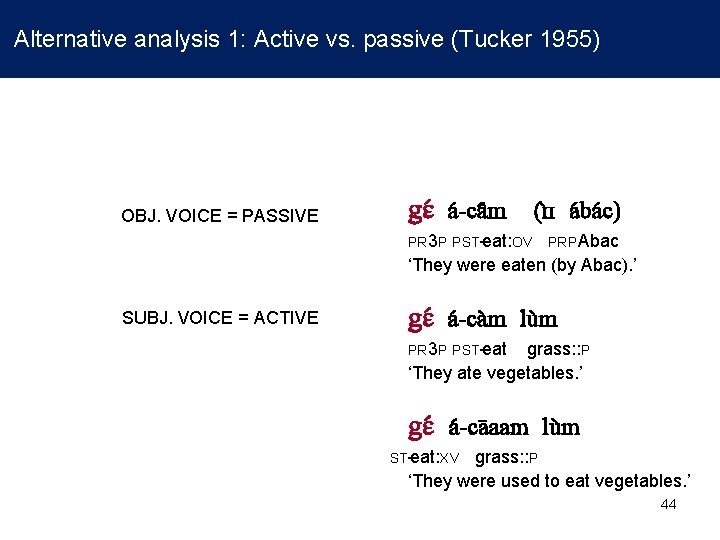

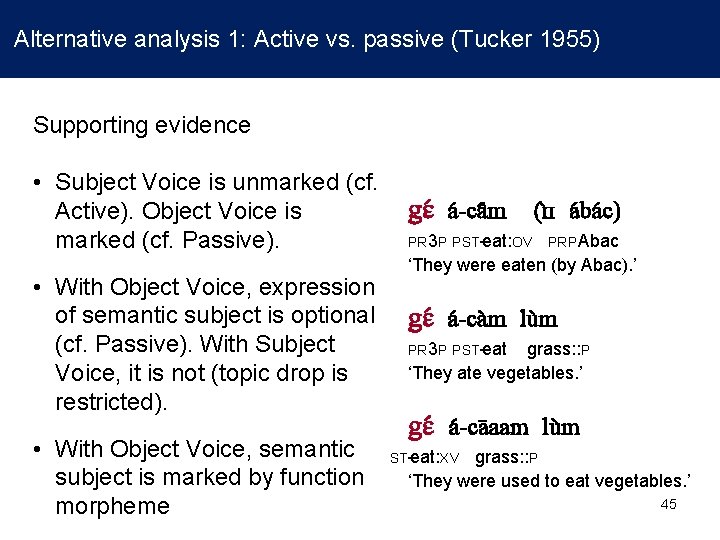

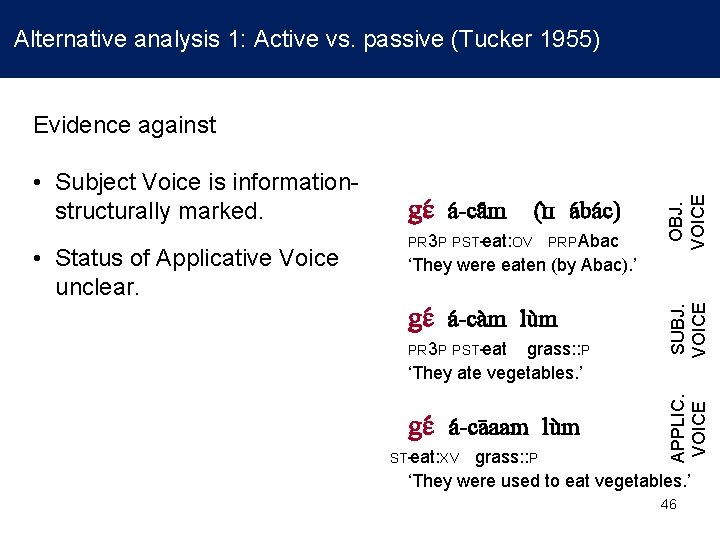

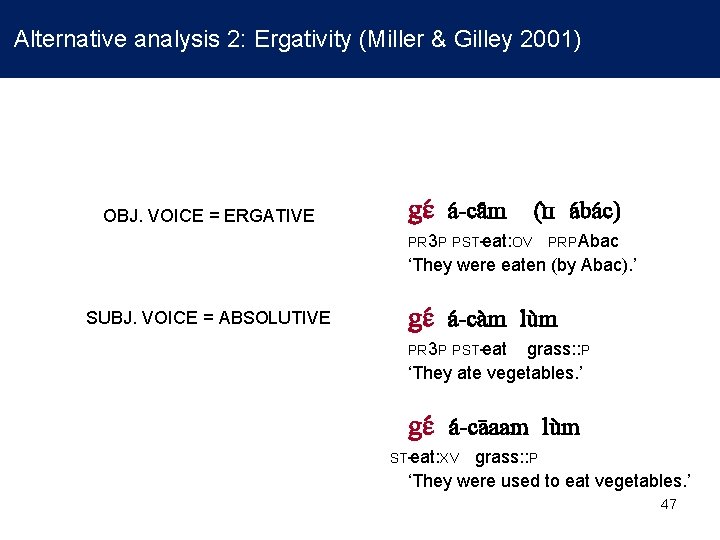

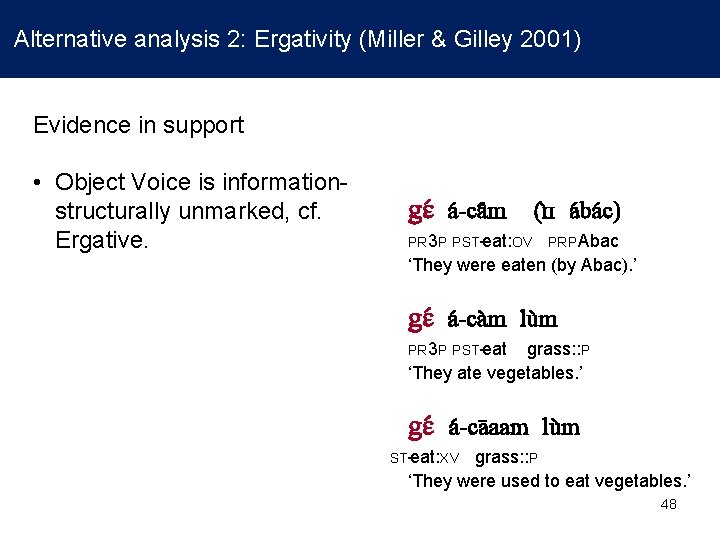

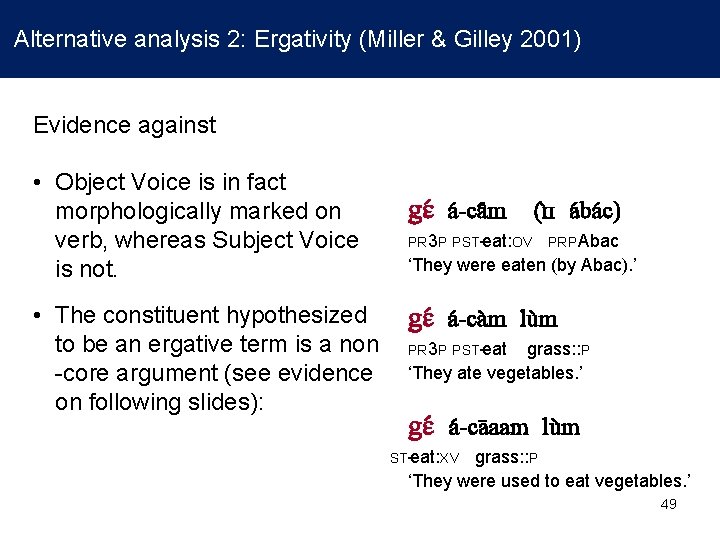

Discussion In earlier work the Object Voice has been analysed as passive (Tucker 1955) and as ergative (Miller & Gilley 2001). Neither of these interpretations fit with the phenomena: • The passive analysis of Object Voice predicts that this form of the verb is marked in terms of information structure. However, it is functionally unmarked. • The ergative analysis of the Object Voice predicts that this form of the verb is morphologically unmarked. However, it is instead the Subject Voice form that is formally unmarked, while the Object Voice is formally marked.

Acknowledgements • The Shilluk Language Council, and SIL South Sudan, for enabling our research in South Sudan. • The Leverhulme Trust, for research funding through the project “A descriptive analysis of the Shilluk language” (RPG-2015 -055). 40

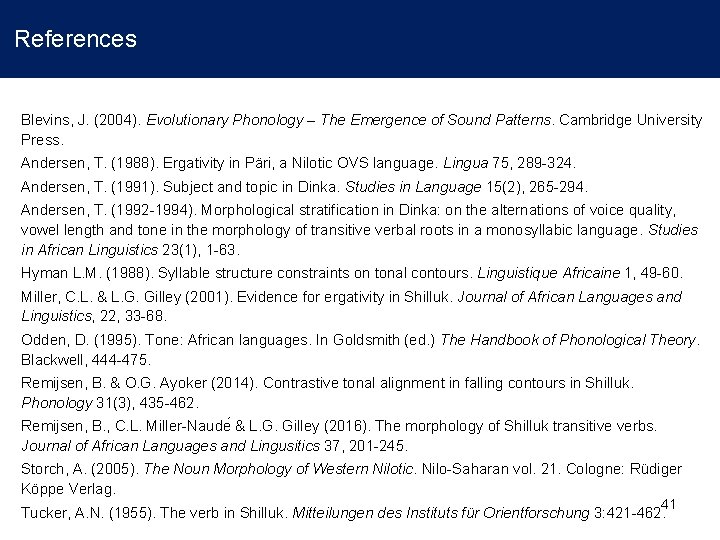

References Blevins, J. (2004). Evolutionary Phonology – The Emergence of Sound Patterns. Cambridge University Press. Andersen, T. (1988). Ergativity in Päri, a Nilotic OVS language. Lingua 75, 289 -324. Andersen, T. (1991). Subject and topic in Dinka. Studies in Language 15(2), 265 -294. Andersen, T. (1992 -1994). Morphological stratification in Dinka: on the alternations of voice quality, vowel length and tone in the morphology of transitive verbal roots in a monosyllabic language. Studies in African Linguistics 23(1), 1 -63. Hyman L. M. (1988). Syllable structure constraints on tonal contours. Linguistique Africaine 1, 49 -60. Miller, C. L. & L. G. Gilley (2001). Evidence for ergativity in Shilluk. Journal of African Languages and Linguistics, 22, 33 -68. Odden, D. (1995). Tone: African languages. In Goldsmith (ed. ) The Handbook of Phonological Theory. Blackwell, 444 -475. Remijsen, B. & O. G. Ayoker (2014). Contrastive tonal alignment in falling contours in Shilluk. Phonology 31(3), 435 -462. Remijsen, B. , C. L. Miller-Naude & L. G. Gilley (2016). The morphology of Shilluk transitive verbs. Journal of African Languages and Lingusitics 37, 201 -245. Storch, A. (2005). The Noun Morphology of Western Nilotic. Nilo-Saharan vol. 21. Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe Verlag. 41 Tucker, A. N. (1955). The verb in Shilluk. Mitteilungen des Instituts für Orientforschung 3: 421 -462.

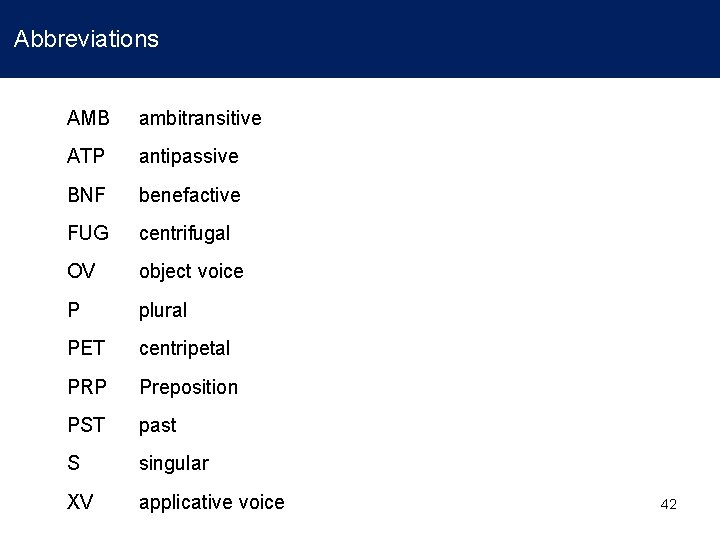

Abbreviations AMB ambitransitive ATP antipassive BNF benefactive FUG centrifugal OV object voice P plural PET centripetal PRP Preposition PST past S singular XV applicative voice 42

Extra 1 – alternative analyses 43

Alternative analysis 1: Active vs. passive (Tucker 1955) lu m gɛ a -ca m (ɪ ɪ a ba c) a OBJ. -gwɔ VOICE k dɪ =kɪ PASSIVE grass: P PST-make: OV PRP HOW ‘What was done with the vegetables? ’ PR 3 P PST-eat: OV ɟɪ ɪ gɛ a -ca m lu m a -SUBJ. ca m VOICE ŋɔ = ACTIVE PRP Abac ‘They were eaten (by Abac). ’ people PST-eat WHAT ‘What did the people eat? ’ PR 3 P PST-eat pʌ t gɛ a -ca aam lu m a -gwɔ ɔɔk ŋɔ spoon: P PST-make: XV WHAT ‘What were the spoons used for? ’ grass: : P ‘They ate vegetables. ’ PR 3 P PST-eat: XV grass: : P ‘They were used to eat vegetables. ’ 44

Alternative analysis 1: Active vs. passive (Tucker 1955) Supporting evidence • Subject Voice is unmarked (cf. lu Active). m a -gwɔ k Voice kɪ dɪ is Object grass: P PST-make: OV PRP HOW marked (cf. Passive). ‘What was done with the vegetables? ’ gɛ a -ca m (ɪ ɪ a ba c) PR 3 P PST-eat: OV PRP Abac ‘They were eaten (by Abac). ’ • With Object Voice, expression is optional gɛ a -ca m lu m ɟɪ of ɪ semantic a -ca m subject ŋɔ (cf. Passive). With Subject people PST-eat WHAT PR 3 P PST-eat grass: : P ‘What did the eat? ’ drop is ‘They ate vegetables. ’ Voice, it ispeople not (topic restricted). pʌ t a -gwɔ ɔɔk ŋɔ gɛ a -ca aam lu m • spoon: With. PObject Voice, PST-make: XV WHATsemantic PR 3 P PST-eat: XV grass: : P subject by for? ’ function ‘What wereis themarked spoons used ‘They were used to eat vegetables. ’ 45 morpheme

Alternative analysis 1: Active vs. passive (Tucker 1955) unclear. ɟɪ ɪ a -ca m PR 3 P PST-eat: OV PRP Abac ‘They were eaten (by Abac). ’ gɛ a -ca m lu m ŋɔ people PST-eat WHAT ‘What did the people eat? ’ PR 3 P PST-eat pʌ t gɛ a -ca aam lu m a -gwɔ ɔɔk ŋɔ spoon: P PST-make: XV WHAT ‘What were the spoons used for? ’ grass: : P ‘They ate vegetables. ’ PR 3 P PST-eat: XV SUBJ. VOICE • grass: P PST-make: OV PRP HOW Status Applicative Voice ‘What wasof done with the vegetables? ’ gɛ a -ca m (ɪ ɪ a ba c) APPLIC. VOICE • Subject Voice is informationlu structurally m a -gwɔ kmarked. kɪ dɪ OBJ. VOICE Evidence against grass: : P ‘They were used to eat vegetables. ’ 46

Alternative analysis 2: Ergativity (Miller & Gilley 2001) a -gwɔ k = ERGATIVE kɪ dɪ OBJ. VOICE grass: P PST-make: OV PRP HOW ‘What was done with the vegetables? ’ gɛ a -ca m (ɪ ɪ a ba c) ɟɪ ɪ gɛ a -ca m lu m SUBJ. = ABSOLUTIVE a -ca VOICE m ŋɔ PR 3 P PST-eat: OV PRP Abac ‘They were eaten (by Abac). ’ people PST-eat WHAT ‘What did the people eat? ’ PR 3 P PST-eat pʌ t gɛ a -ca aam lu m a -gwɔ ɔɔk ŋɔ spoon: P PST-make: XV WHAT ‘What were the spoons used for? ’ grass: : P ‘They ate vegetables. ’ PR 3 P PST-eat: XV grass: : P ‘They were used to eat vegetables. ’ 47

Alternative analysis 2: Ergativity (Miller & Gilley 2001) Evidence in support • Object Voice is informationlu structurally m a -gwɔ kunmarked, kɪ dɪ cf. grass: P PST-make: OV PRP HOW Ergative. gɛ a -ca m (ɪ ɪ a ba c) PR 3 P PST-eat: OV PRP Abac ‘What was done with the vegetables? ’ ‘They were eaten (by Abac). ’ ɟɪ ɪ gɛ a -ca m lu m a -ca m ŋɔ people PST-eat WHAT ‘What did the people eat? ’ PR 3 P PST-eat pʌ t gɛ a -ca aam lu m a -gwɔ ɔɔk ŋɔ spoon: P PST-make: XV WHAT ‘What were the spoons used for? ’ grass: : P ‘They ate vegetables. ’ PR 3 P PST-eat: XV grass: : P ‘They were used to eat vegetables. ’ 48

Alternative analysis 2: Ergativity (Miller & Gilley 2001) Evidence against • Object Voice is in fact lu morphologically m a -gwɔ k kɪ dɪ on marked grass: -make: OVSubject PRP HOW Voice verb, P PST whereas ‘What was done with the vegetables? ’ is not. • ɟɪ The ɪ constituent a -ca m ŋɔ hypothesized to be. PST an-eat ergative term is a non people WHAT ‘What the people eat? ’ -coredidargument (see evidence on following slides): pʌ t a -gwɔ ɔɔk ŋɔ spoon: P PST-make: XV WHAT ‘What were the spoons used for? ’ gɛ a -ca m (ɪ ɪ a ba c) PR 3 P PST-eat: OV PRP Abac ‘They were eaten (by Abac). ’ gɛ a -ca m lu m PR 3 P PST-eat grass: : P ‘They ate vegetables. ’ gɛ a -ca aam lu m PR 3 P PST-eat: XV grass: : P ‘They were used to eat vegetables. ’ 49

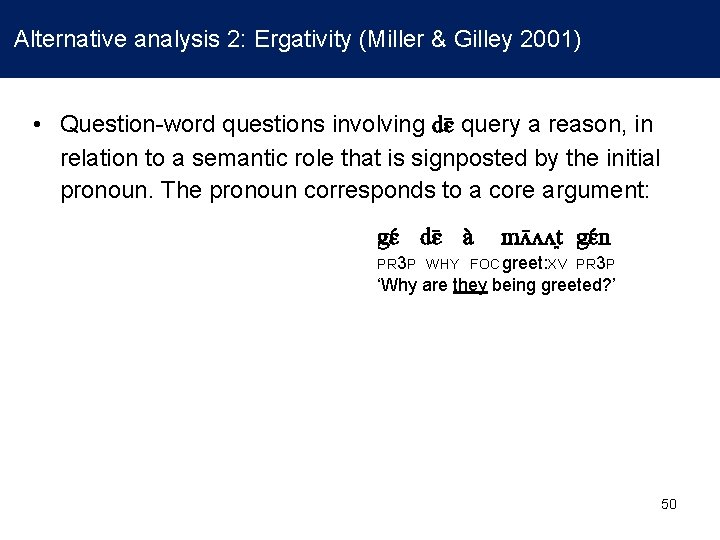

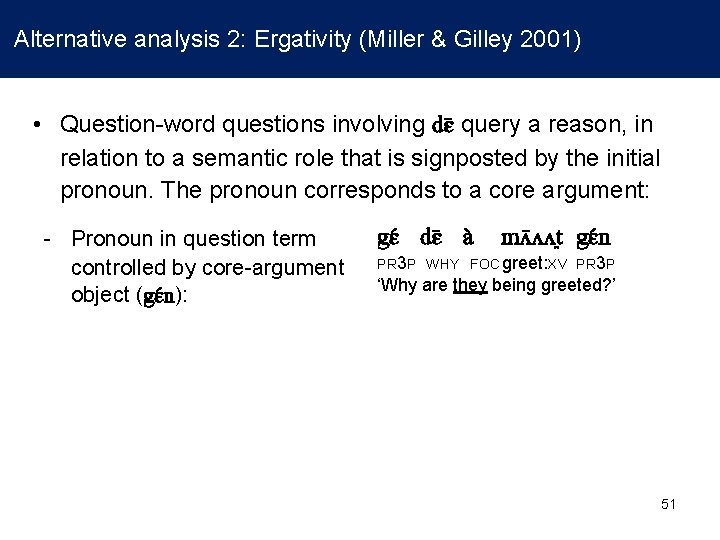

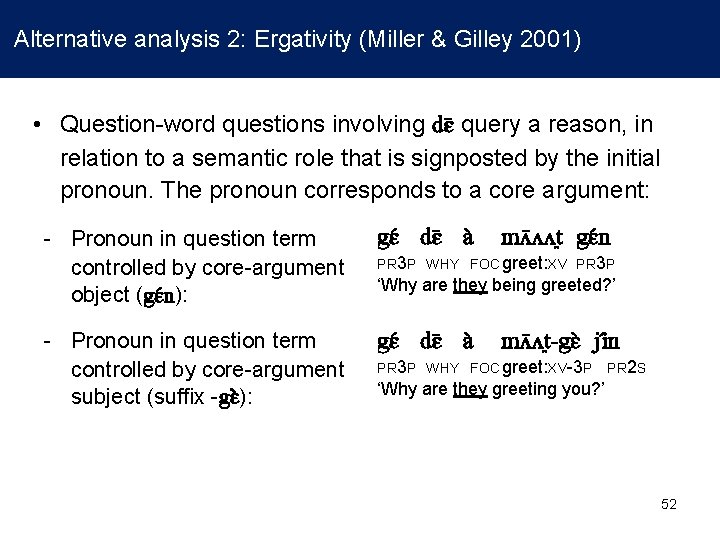

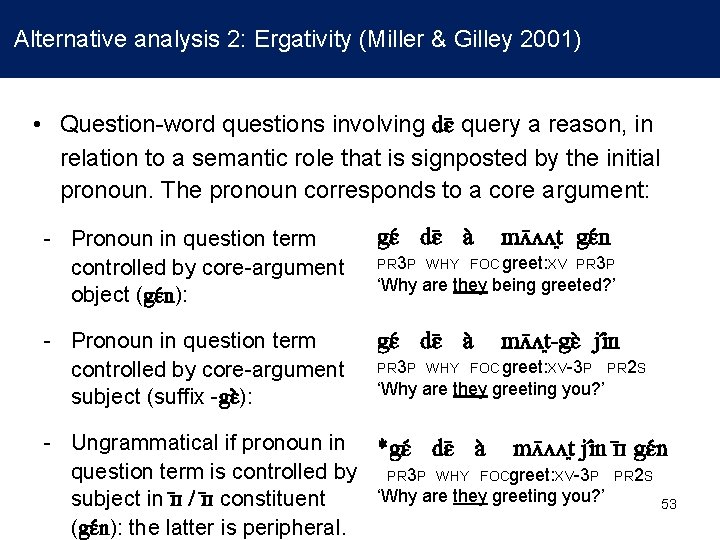

Alternative analysis 2: Ergativity (Miller & Gilley 2001) • Question-word questions involving dɛ query a reason, in relation to a semantic role that is signposted by the initial pronoun. The pronoun corresponds to a core argument: gɛ dɛ a mʌ ʌʌt gɛ n PR 3 P WHY FOC greet: XV PR 3 P ‘Why are they being greeted? ’ 50

Alternative analysis 2: Ergativity (Miller & Gilley 2001) • Question-word questions involving dɛ query a reason, in relation to a semantic role that is signposted by the initial pronoun. The pronoun corresponds to a core argument: - Pronoun in question term controlled by core-argument object (gɛ n): gɛ dɛ a mʌ ʌʌt gɛ n PR 3 P WHY FOC greet: XV PR 3 P ‘Why are they being greeted? ’ 51

Alternative analysis 2: Ergativity (Miller & Gilley 2001) • Question-word questions involving dɛ query a reason, in relation to a semantic role that is signposted by the initial pronoun. The pronoun corresponds to a core argument: - Pronoun in question term controlled by core-argument object (gɛ n): gɛ dɛ a - Pronoun in question term controlled by core-argument subject (suffix -gɛ ): gɛ dɛ a mʌ ʌʌt gɛ n PR 3 P WHY FOC greet: XV PR 3 P ‘Why are they being greeted? ’ mʌ ʌt -gɛ ji n PR 3 P WHY FOC greet: XV-3 P PR 2 S ‘Why are they greeting you? ’ 52

Alternative analysis 2: Ergativity (Miller & Gilley 2001) • Question-word questions involving dɛ query a reason, in relation to a semantic role that is signposted by the initial pronoun. The pronoun corresponds to a core argument: - Pronoun in question term controlled by core-argument object (gɛ n): gɛ dɛ a - Pronoun in question term controlled by core-argument subject (suffix -gɛ ): gɛ dɛ a mʌ ʌʌt gɛ n PR 3 P WHY FOC greet: XV PR 3 P ‘Why are they being greeted? ’ mʌ ʌt -gɛ ji n PR 3 P WHY FOC greet: XV-3 P PR 2 S ‘Why are they greeting you? ’ - Ungrammatical if pronoun in *gɛ dɛ a mʌ ʌʌt ji n ɪ ɪ gɛ n question term is controlled by PR 3 P WHY FOCgreet: XV-3 P PR 2 S ‘Why are they greeting you? ’ subject in ɪ ɪ / ɪ ɪ constituent 53 (gɛ n): the latter is peripheral.

Extra 2 – contrastive tonal alignment (see Remijsen & Ayoker 2014) 54

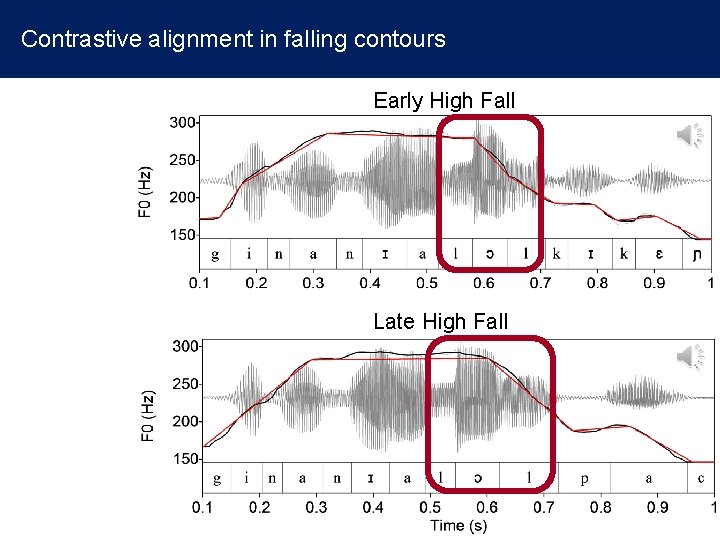

Contrastive alignment in falling contours Early High Fall Late High Fall

![Contrastive alignment in falling contours “[T]here is no possible opposition between two HL or Contrastive alignment in falling contours “[T]here is no possible opposition between two HL or](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/ed2def7943e841667030eb1252d03abb/image-56.jpg)

Contrastive alignment in falling contours “[T]here is no possible opposition between two HL or two LH contours where the two tones are synchronized differently within the syllable. ” [Hyman 1988: 51] “[I]t might be that in some languages pitch changes are timed relatively early in the syllable, and in other languages they are timed relatively late. Such control would only be phonetic, never phonological. ” [Odden 1995: 450] 56

- Slides: 56