The Sonnet History of the Sonnet The sonnet

- Slides: 14

The Sonnet

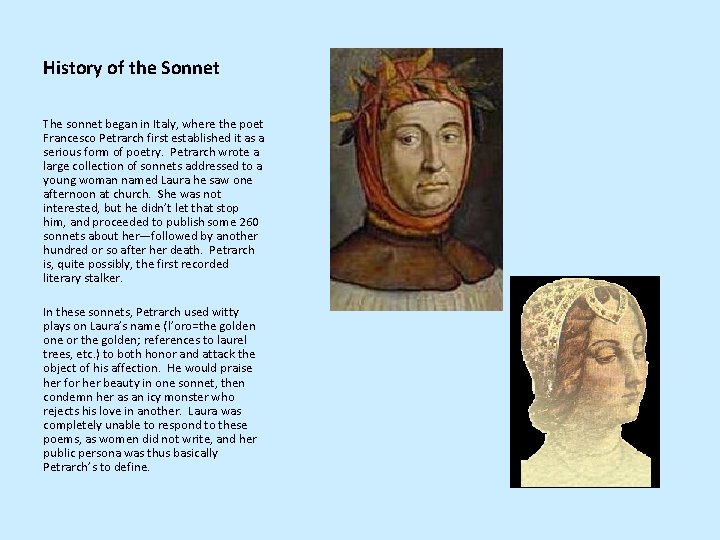

History of the Sonnet The sonnet began in Italy, where the poet Francesco Petrarch first established it as a serious form of poetry. Petrarch wrote a large collection of sonnets addressed to a young woman named Laura he saw one afternoon at church. She was not interested, but he didn’t let that stop him, and proceeded to publish some 260 sonnets about her—followed by another hundred or so after her death. Petrarch is, quite possibly, the first recorded literary stalker. In these sonnets, Petrarch used witty plays on Laura’s name (l’oro=the golden one or the golden; references to laurel trees, etc. ) to both honor and attack the object of his affection. He would praise her for her beauty in one sonnet, then condemn her as an icy monster who rejects his love in another. Laura was completely unable to respond to these poems, as women did not write, and her public persona was thus basically Petrarch’s to define.

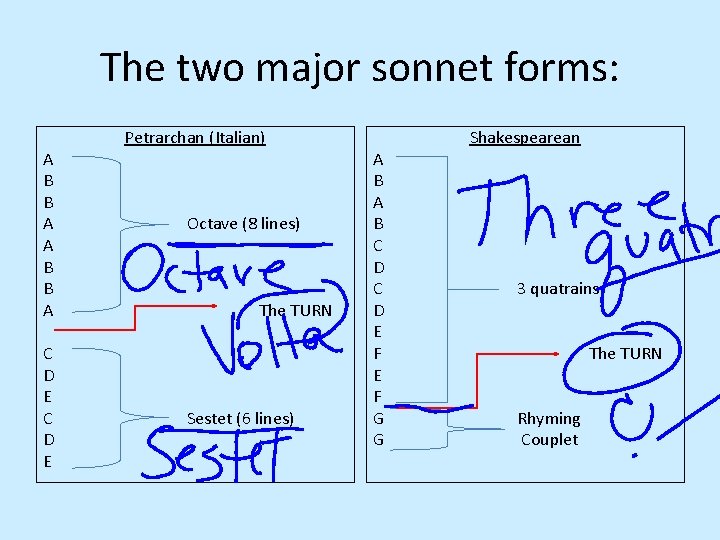

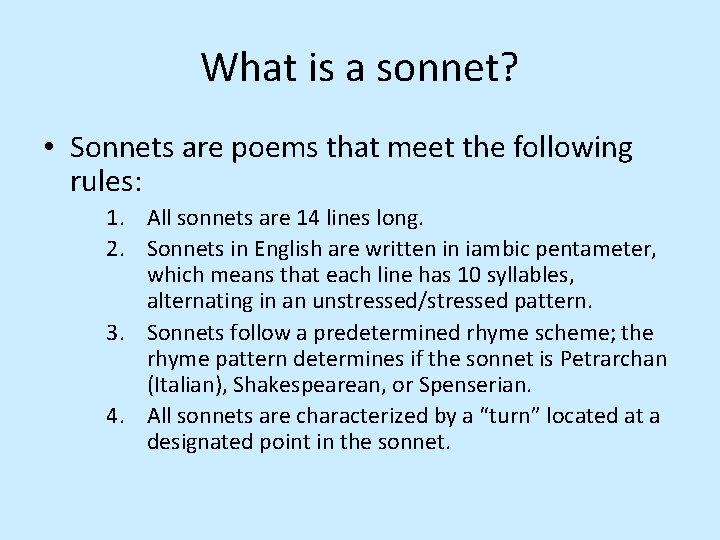

What is a sonnet? • Sonnets are poems that meet the following rules: 1. All sonnets are 14 lines long. 2. Sonnets in English are written in iambic pentameter, which means that each line has 10 syllables, alternating in an unstressed/stressed pattern. 3. Sonnets follow a predetermined rhyme scheme; the rhyme pattern determines if the sonnet is Petrarchan (Italian), Shakespearean, or Spenserian. 4. All sonnets are characterized by a “turn” located at a designated point in the sonnet.

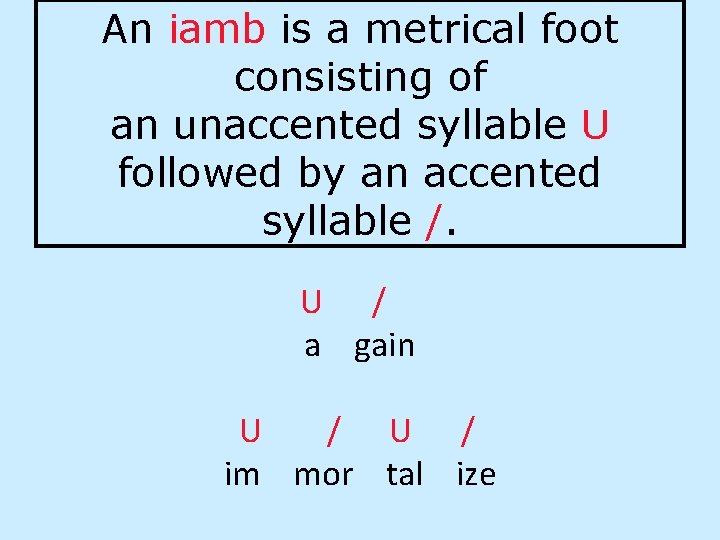

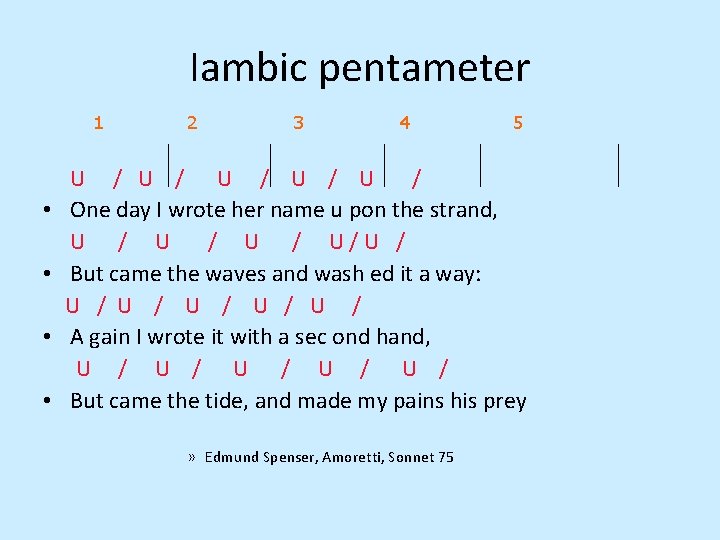

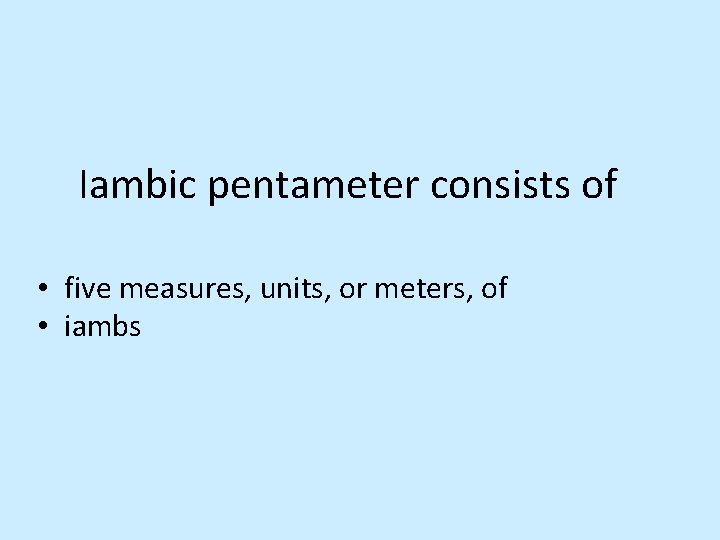

Iambic pentameter consists of • five measures, units, or meters, of • iambs

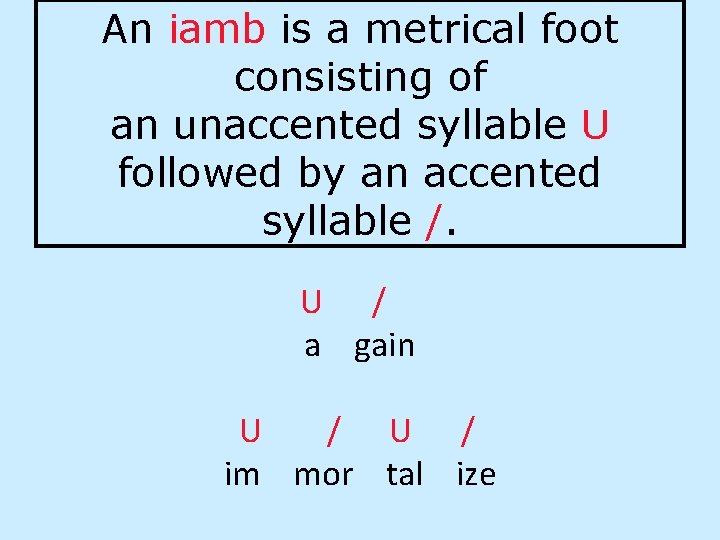

An iamb is a metrical foot consisting of an unaccented syllable U followed by an accented syllable /. U / a gain U / im mor tal ize

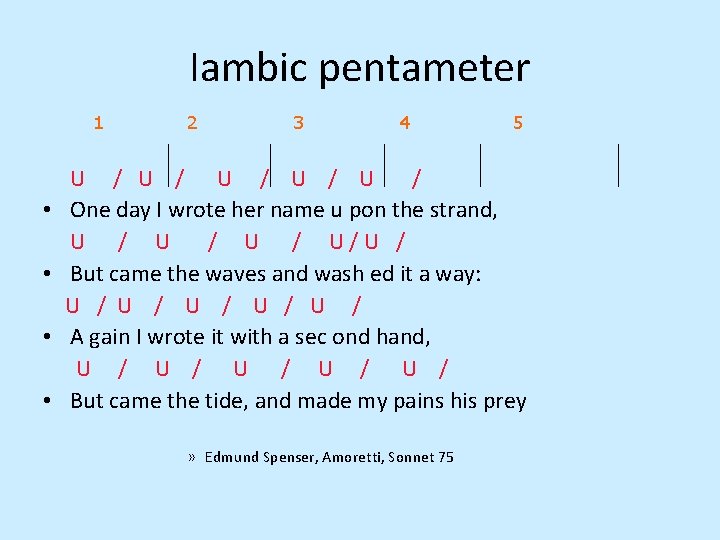

Iambic pentameter 1 • • 2 3 4 5 U / U / U / One day I wrote her name u pon the strand, U / U / U/U / But came the waves and wash ed it a way: U / U / U / A gain I wrote it with a sec ond hand, U / U / U / But came the tide, and made my pains his prey » Edmund Spenser, Amoretti, Sonnet 75

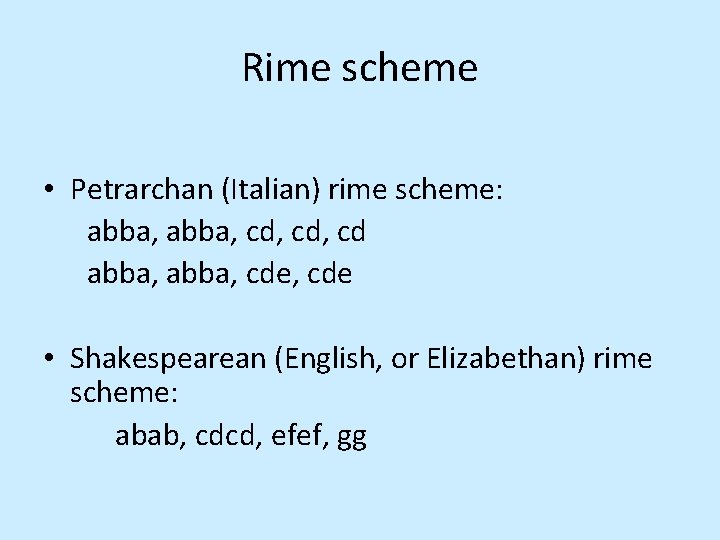

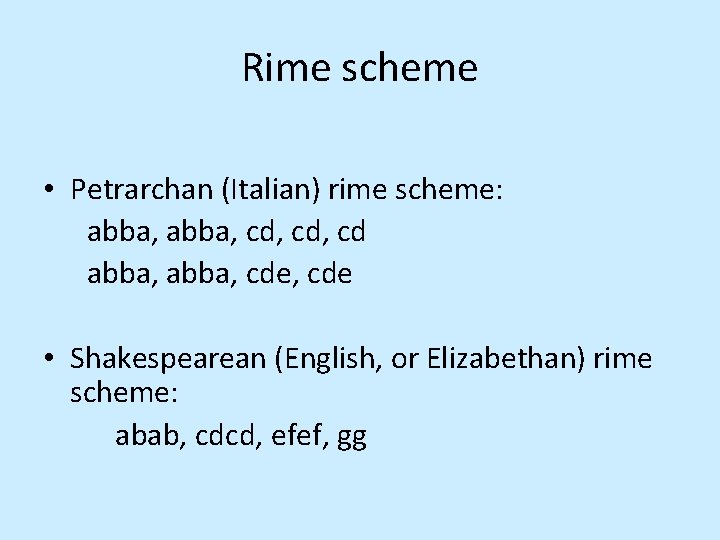

Rime scheme • Petrarchan (Italian) rime scheme: abba, cd, cd abba, cde, cde • Shakespearean (English, or Elizabethan) rime scheme: abab, cdcd, efef, gg

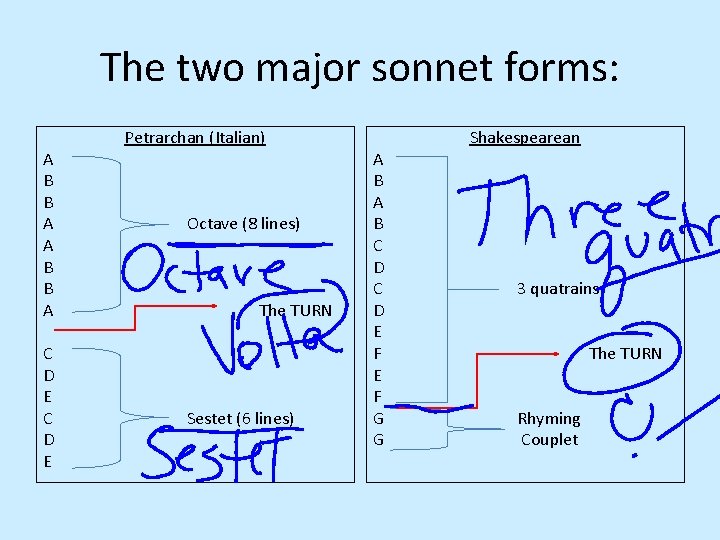

The two major sonnet forms: A B B A C D E Petrarchan (Italian) Octave (8 lines) The TURN Sestet (6 lines) A B C D E F G G Shakespearean 3 quatrains The TURN Rhyming Couplet

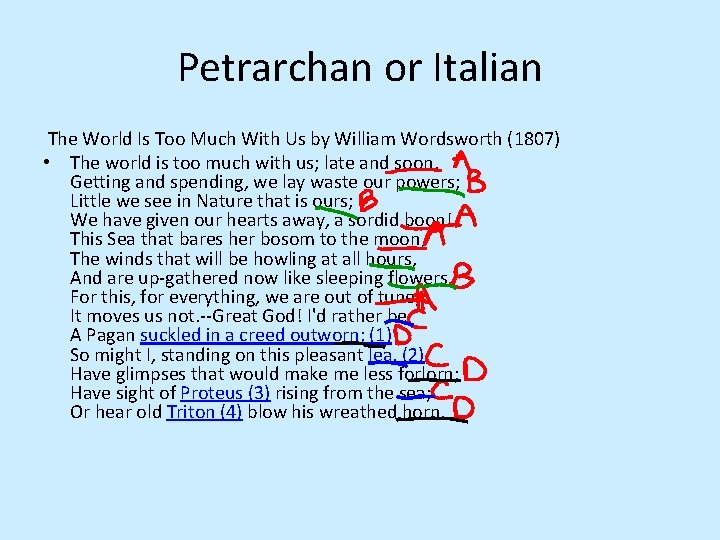

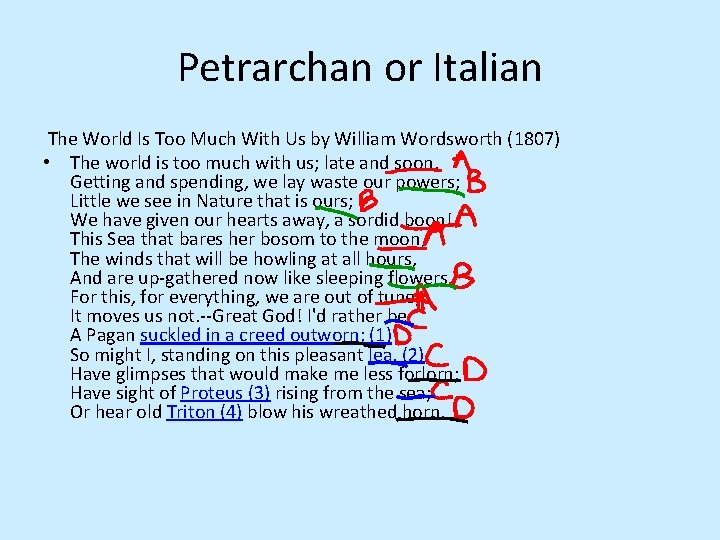

Petrarchan or Italian The World Is Too Much With Us by William Wordsworth (1807) • The world is too much with us; late and soon, Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers; Little we see in Nature that is ours; We have given our hearts away, a sordid boon! This Sea that bares her bosom to the moon, The winds that will be howling at all hours, And are up-gathered now like sleeping flowers, For this, for everything, we are out of tune; It moves us not. --Great God! I'd rather be A Pagan suckled in a creed outworn; (1) So might I, standing on this pleasant lea, (2) Have glimpses that would make me less forlorn; Have sight of Proteus (3) rising from the sea; Or hear old Triton (4) blow his wreathed horn.

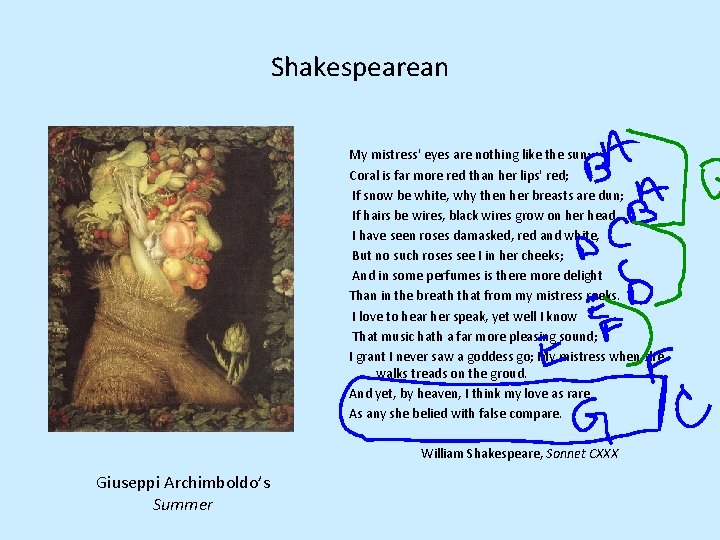

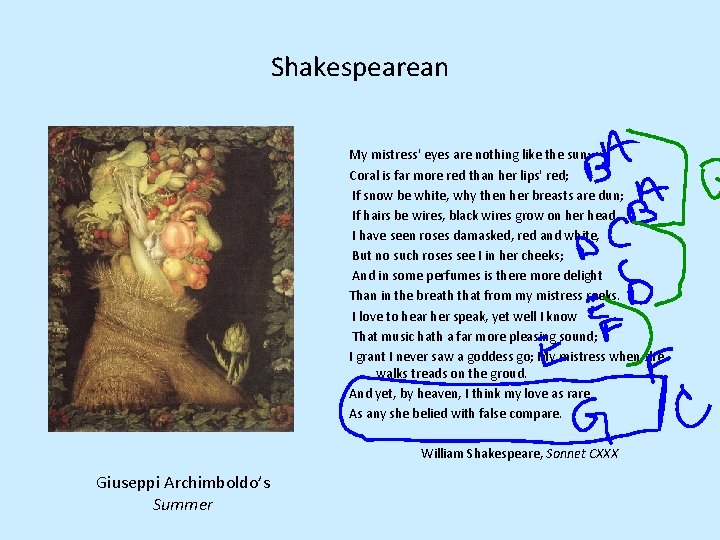

Shakespearean My mistress' eyes are nothing like the sun; Coral is far more red than her lips' red; If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun; If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head. I have seen roses damasked, red and white, But no such roses see I in her cheeks; And in some perfumes is there more delight Than in the breath that from my mistress reeks. I love to hear her speak, yet well I know That music hath a far more pleasing sound; I grant I never saw a goddess go; My mistress when she walks treads on the groud. And yet, by heaven, I think my love as rare As any she belied with false compare. William Shakespeare, Sonnet CXXX Giuseppi Archimboldo’s Summer

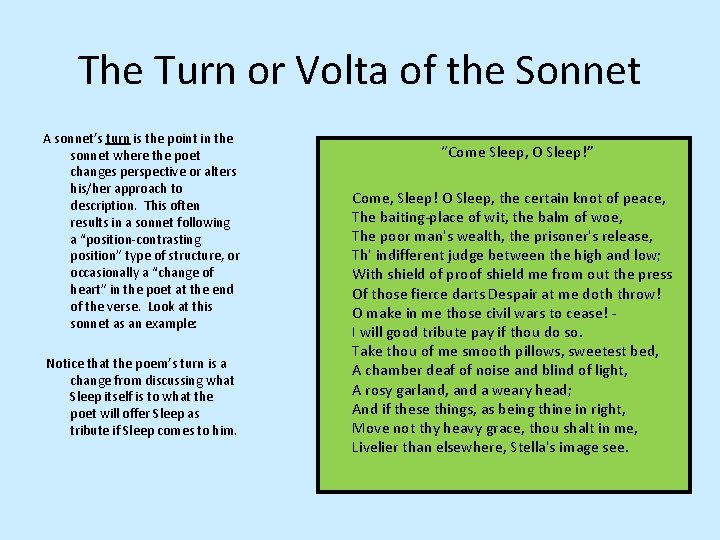

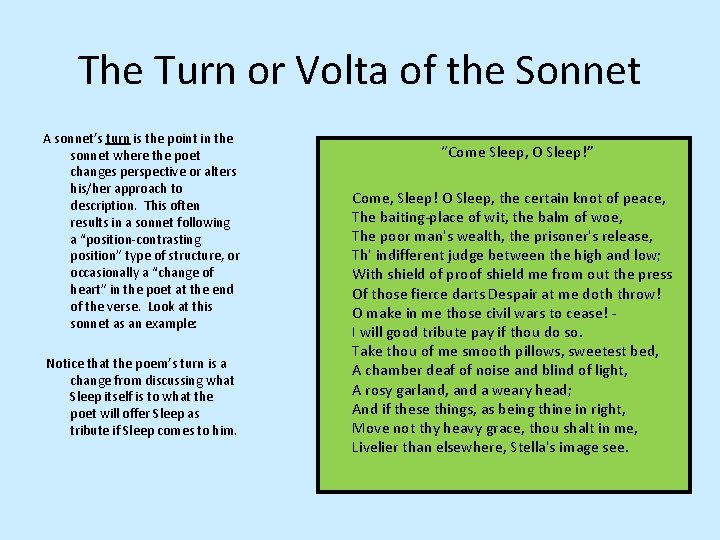

The Turn or Volta of the Sonnet A sonnet’s turn is the point in the sonnet where the poet changes perspective or alters his/her approach to description. This often results in a sonnet following a “position-contrasting position” type of structure, or occasionally a “change of heart” in the poet at the end of the verse. Look at this sonnet as an example: Notice that the poem’s turn is a change from discussing what Sleep itself is to what the poet will offer Sleep as tribute if Sleep comes to him. “Come Sleep, O Sleep!” Come, Sleep! O Sleep, the certain knot of peace, The baiting-place of wit, the balm of woe, The poor man's wealth, the prisoner's release, Th' indifferent judge between the high and low; With shield of proof shield me from out the press Of those fierce darts Despair at me doth throw! O make in me those civil wars to cease! I will good tribute pay if thou do so. Take thou of me smooth pillows, sweetest bed, A chamber deaf of noise and blind of light, A rosy garland, and a weary head; And if these things, as being thine in right, Move not thy heavy grace, thou shalt in me, Livelier than elsewhere, Stella's image see.

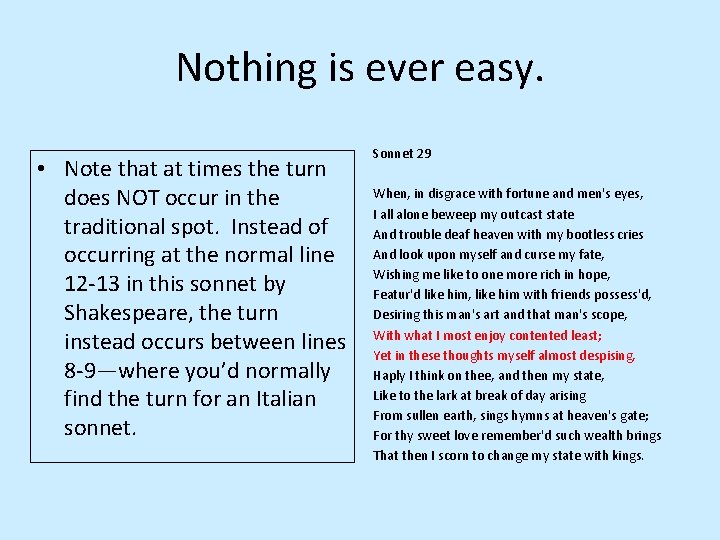

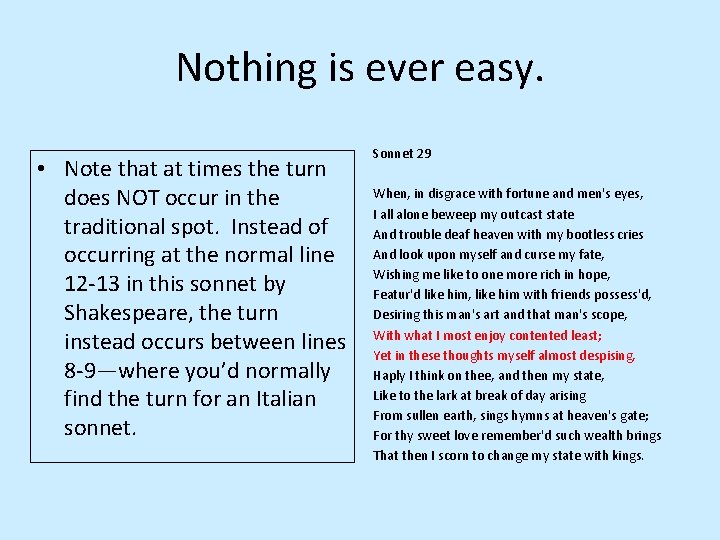

Nothing is ever easy. • Note that at times the turn does NOT occur in the traditional spot. Instead of occurring at the normal line 12 -13 in this sonnet by Shakespeare, the turn instead occurs between lines 8 -9—where you’d normally find the turn for an Italian sonnet. Sonnet 29 When, in disgrace with fortune and men's eyes, I all alone beweep my outcast state And trouble deaf heaven with my bootless cries And look upon myself and curse my fate, Wishing me like to one more rich in hope, Featur'd like him, like him with friends possess'd, Desiring this man's art and that man's scope, With what I most enjoy contented least; Yet in these thoughts myself almost despising, Haply I think on thee, and then my state, Like to the lark at break of day arising From sullen earth, sings hymns at heaven's gate; For thy sweet love remember'd such wealth brings That then I scorn to change my state with kings.

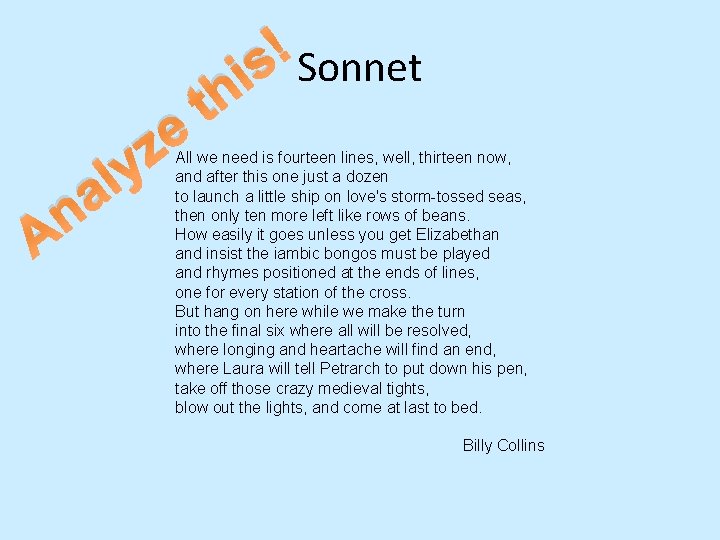

n A e z y l a t i h ! s Sonnet All we need is fourteen lines, well, thirteen now, and after this one just a dozen to launch a little ship on love's storm-tossed seas, then only ten more left like rows of beans. How easily it goes unless you get Elizabethan and insist the iambic bongos must be played and rhymes positioned at the ends of lines, one for every station of the cross. But hang on here while we make the turn into the final six where all will be resolved, where longing and heartache will find an end, where Laura will tell Petrarch to put down his pen, take off those crazy medieval tights, blow out the lights, and come at last to bed. Billy Collins

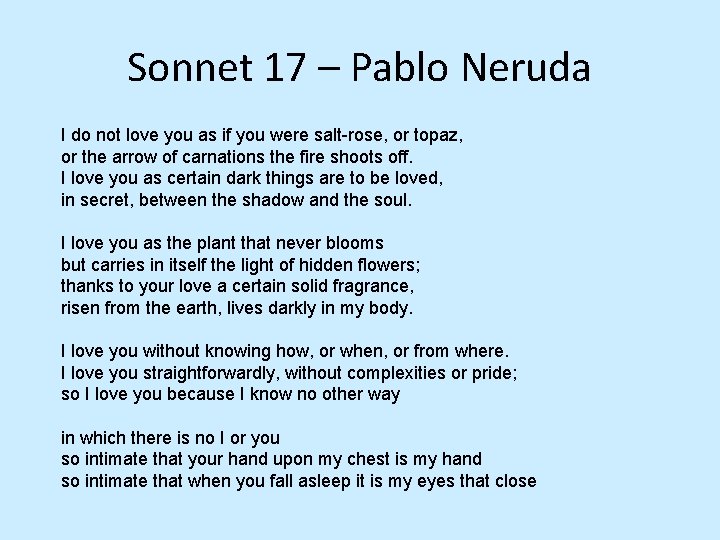

Sonnet 17 – Pablo Neruda I do not love you as if you were salt-rose, or topaz, or the arrow of carnations the fire shoots off. I love you as certain dark things are to be loved, in secret, between the shadow and the soul. I love you as the plant that never blooms but carries in itself the light of hidden flowers; thanks to your love a certain solid fragrance, risen from the earth, lives darkly in my body. I love you without knowing how, or when, or from where. I love you straightforwardly, without complexities or pride; so I love you because I know no other way in which there is no I or you so intimate that your hand upon my chest is my hand so intimate that when you fall asleep it is my eyes that close