The Role of Functional Impairment in Depression and

- Slides: 37

The Role of Functional Impairment in Depression and Suicidal Behavior among Older Adults September 8, 2020 Amy Fiske, Ph. D Associate Professor of Psychology West Virginia University

Overview • • Introduction Conceptual Framework Value Placed on Autonomy Coping Strategies Cognitive Flexibility Engaging in Pleasant Events Future Directions Clinical Implications

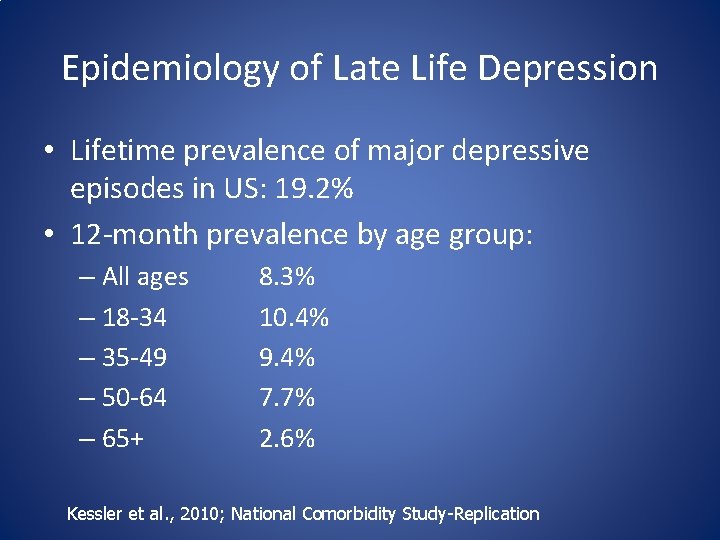

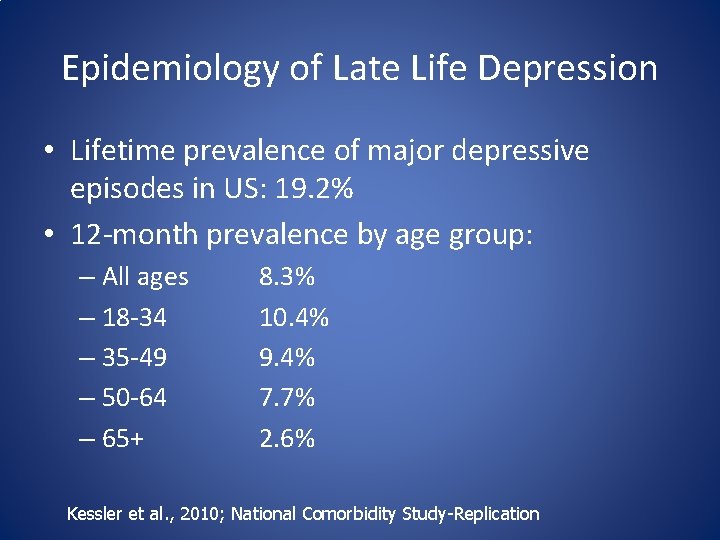

Epidemiology of Late Life Depression • Lifetime prevalence of major depressive episodes in US: 19. 2% • 12 -month prevalence by age group: – All ages – 18 -34 – 35 -49 – 50 -64 – 65+ 8. 3% 10. 4% 9. 4% 7. 7% 2. 6% Kessler et al. , 2010; National Comorbidity Study-Replication

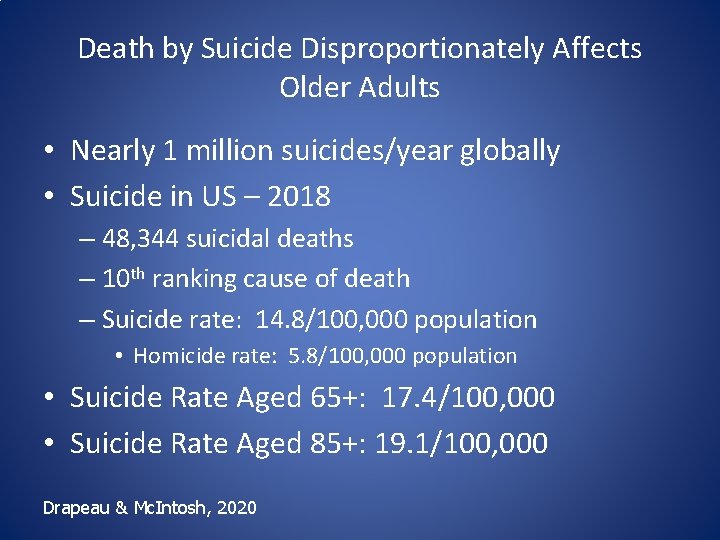

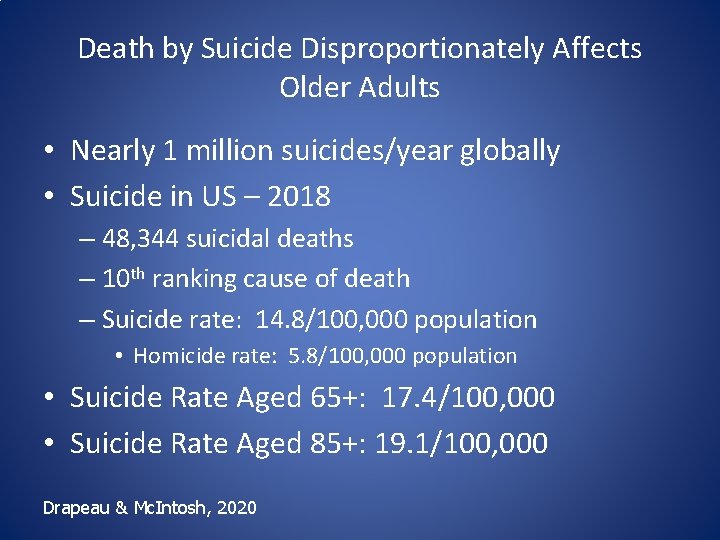

Death by Suicide Disproportionately Affects Older Adults • Nearly 1 million suicides/year globally • Suicide in US – 2018 – 48, 344 suicidal deaths – 10 th ranking cause of death – Suicide rate: 14. 8/100, 000 population • Homicide rate: 5. 8/100, 000 population • Suicide Rate Aged 65+: 17. 4/100, 000 • Suicide Rate Aged 85+: 19. 1/100, 000 Drapeau & Mc. Intosh, 2020

Risk Factors for Late Life Suicide • Genetics – Non-fatal suicidal behaviors • Psychopathology – Often first episode of depression • Stressful Life events • Physical illness and disability • Enduring predispositions – Neuroticism, low openness to experience – Obsessional and anxious traits • Prior suicidal behavior • Social and other factors • Cognitive factors

Motivational Theory of Lifespan Development • Views successful aging as a function of control – Primary control strategies: changing the environment – Secondary control strategies: changing the self in service of primary control striving Heckhausen, Wrosch, & Schulz, 2010

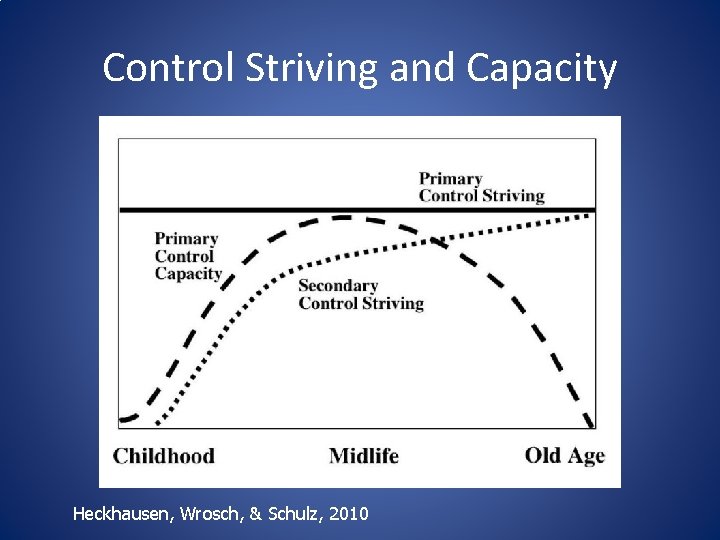

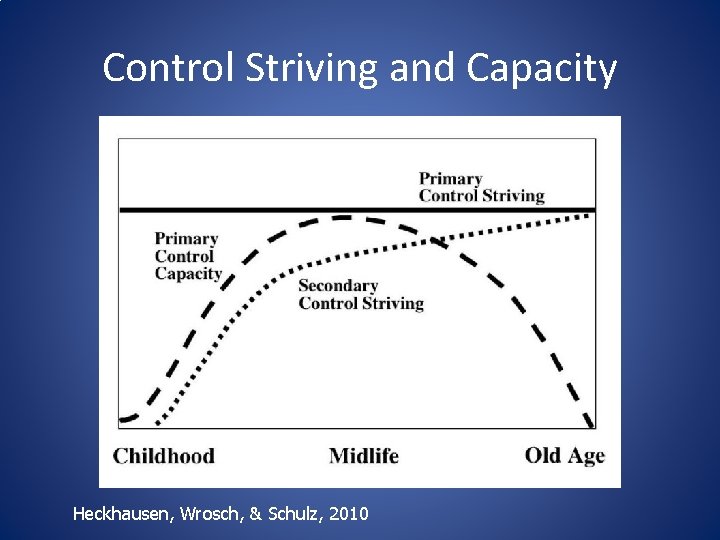

Control Striving and Capacity Heckhausen, Wrosch, & Schulz, 2010

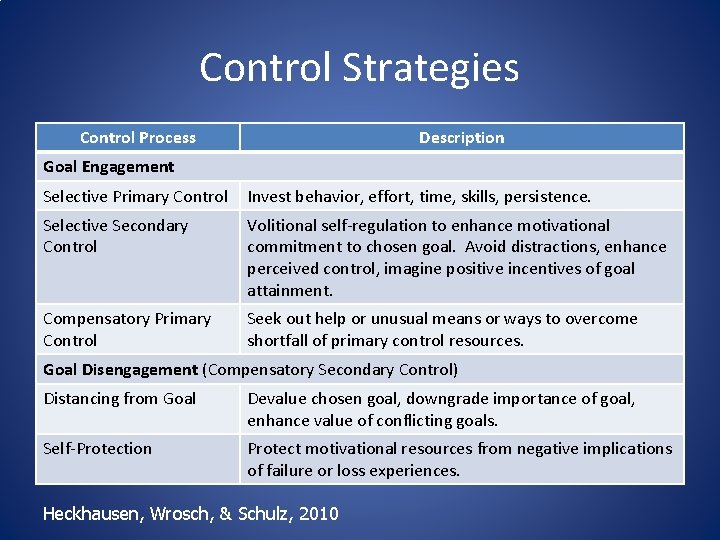

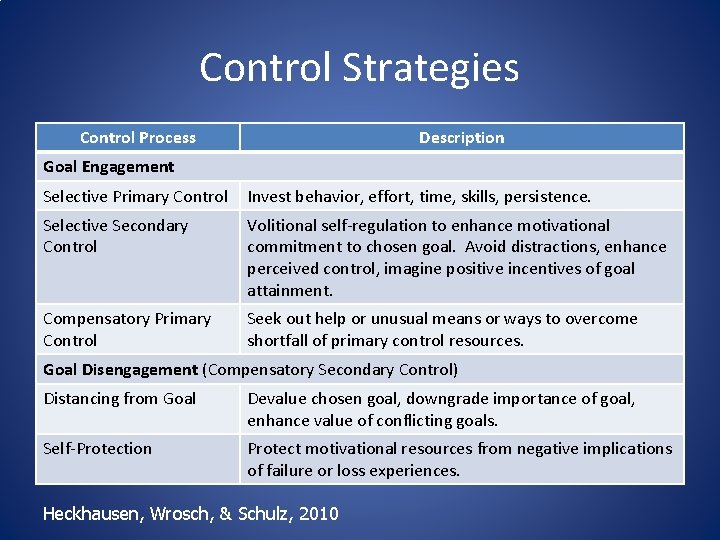

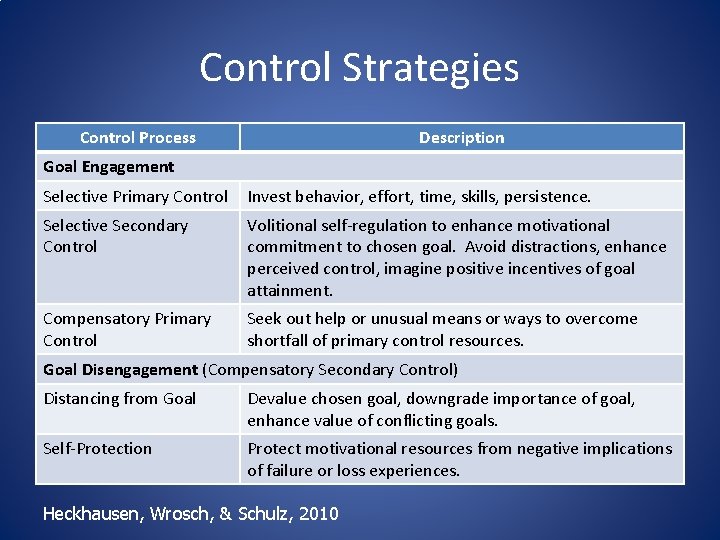

Selection and Compensation • Control strategies can also be classified by regulatory challenges they address: – Selection: investing in a goal – Compensation: responding to failure and loss by honing action strategies and protecting motivational resources Heckhausen, Wrosch, & Schulz, 2010

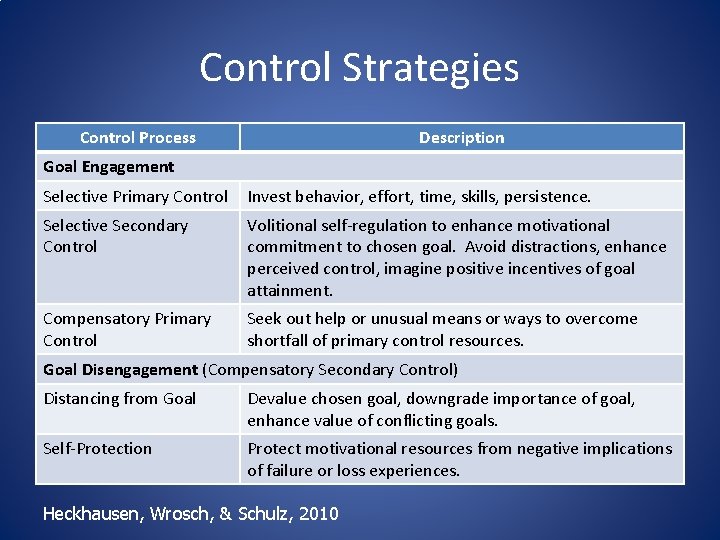

Control Strategies Control Process Description Goal Engagement Selective Primary Control Invest behavior, effort, time, skills, persistence. Selective Secondary Control Volitional self-regulation to enhance motivational commitment to chosen goal. Avoid distractions, enhance perceived control, imagine positive incentives of goal attainment. Compensatory Primary Control Seek out help or unusual means or ways to overcome shortfall of primary control resources. Goal Disengagement (Compensatory Secondary Control) Distancing from Goal Devalue chosen goal, downgrade importance of goal, enhance value of conflicting goals. Self-Protection Protect motivational resources from negative implications of failure or loss experiences. Heckhausen, Wrosch, & Schulz, 2010

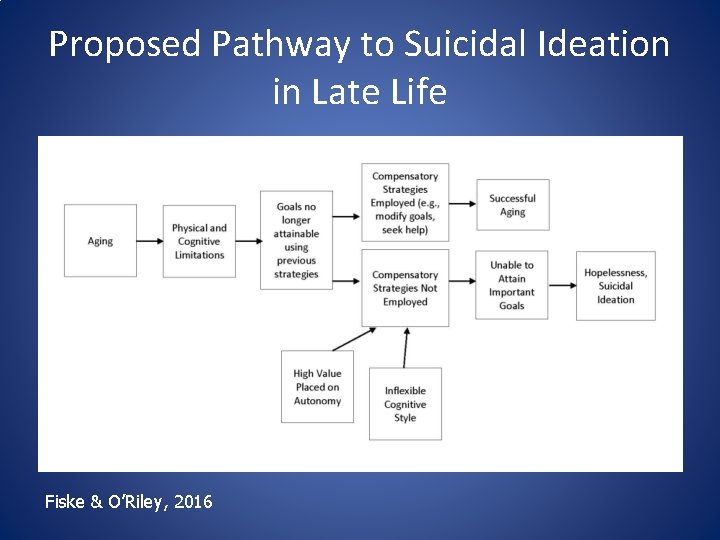

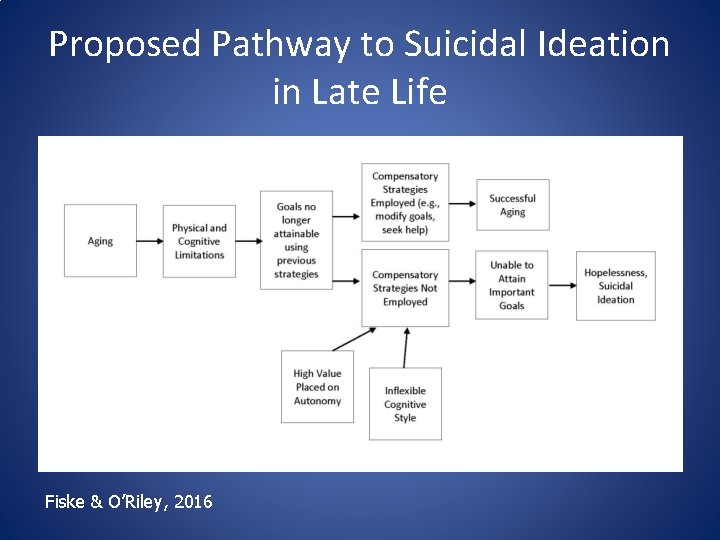

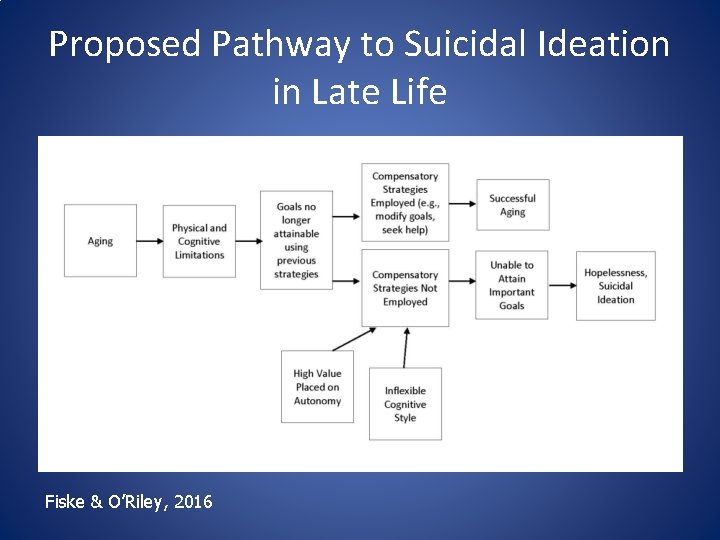

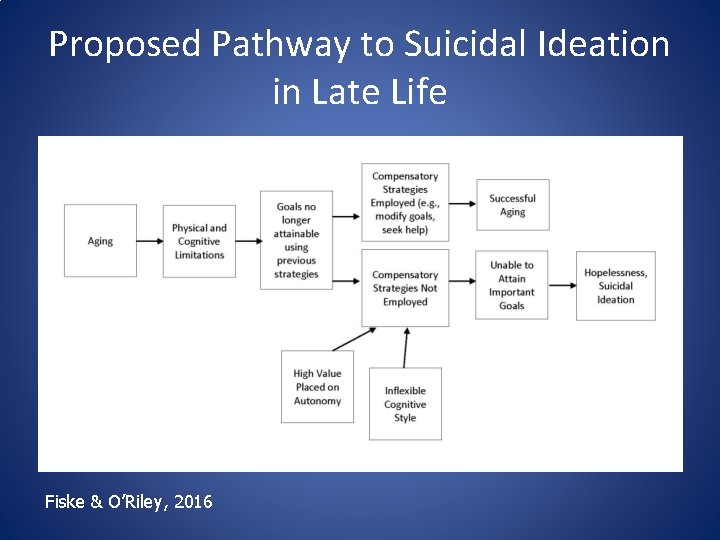

Proposed Pathway to Suicidal Ideation in Late Life Fiske & O’Riley, 2016

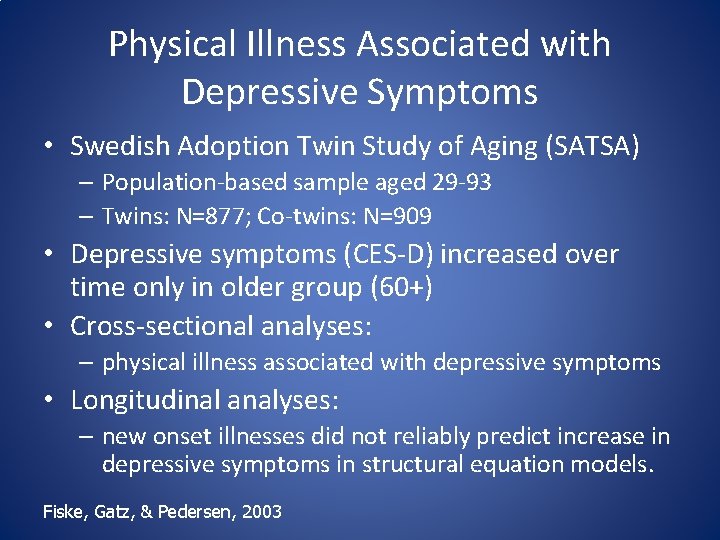

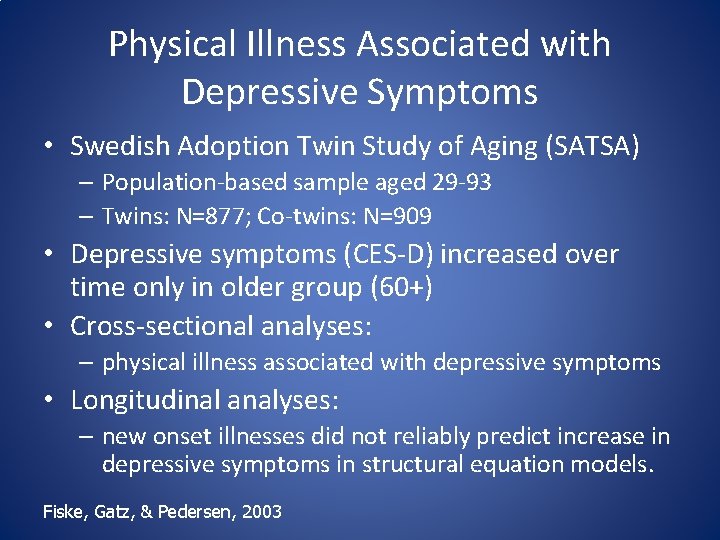

Physical Illness Associated with Depressive Symptoms • Swedish Adoption Twin Study of Aging (SATSA) – Population-based sample aged 29 -93 – Twins: N=877; Co-twins: N=909 • Depressive symptoms (CES-D) increased over time only in older group (60+) • Cross-sectional analyses: – physical illness associated with depressive symptoms • Longitudinal analyses: – new onset illnesses did not reliably predict increase in depressive symptoms in structural equation models. Fiske, Gatz, & Pedersen, 2003

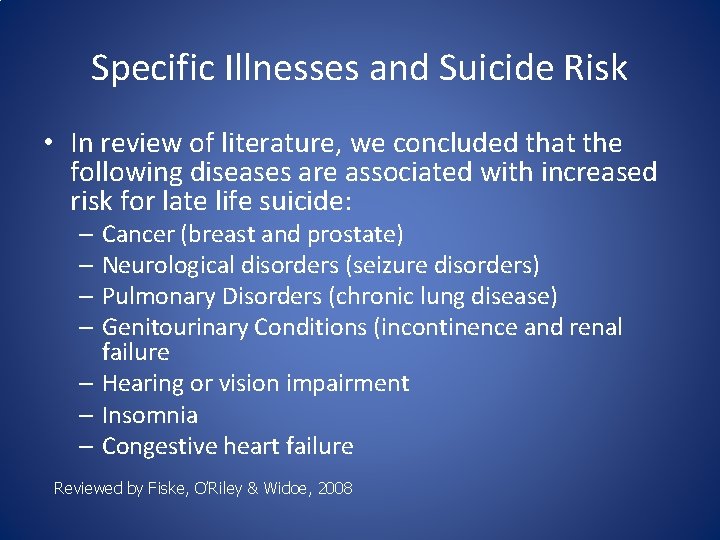

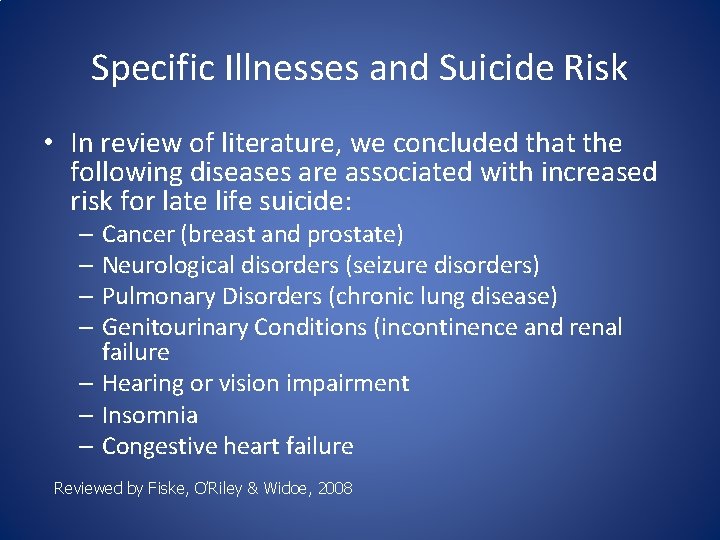

Specific Illnesses and Suicide Risk • In review of literature, we concluded that the following diseases are associated with increased risk for late life suicide: – Cancer (breast and prostate) – Neurological disorders (seizure disorders) – Pulmonary Disorders (chronic lung disease) – Genitourinary Conditions (incontinence and renal failure – Hearing or vision impairment – Insomnia – Congestive heart failure Reviewed by Fiske, O’Riley & Widoe, 2008

Timing of Disease May Be Important • People who receive diagnoses associated with physical illness appear to be at increased risk for suicide: – During the period surrounding diagnosis • Psychological reaction – Later stages of illness • Associated with functional decline Reviewed by Fiske, O’Riley & Widoe, 2008

Possible Mediators • Depression – Some, but not all, risk is explained by depression • Functional impairment – Important risk factor • Pain – Severe pain increases suicide risk (Juurlink et al. , 2004) • Sleep difficulties • Enduring dispositions

SHARE Study • Analysis of European data from SHARE (N=35, 664) • Heart attack, diabetes/high blood sugar, chronic lung disease, arthritis, ulcer, and hip/femoral fractures were associated with increased odds of passive suicidal ideation, partly mediated by functional impairment and depression. • Conditions affecting the endocrine, respiratory, and musculoskeletal systems were associated with increased odds of passive suicidal ideation. (Lutz, Morton, Turiano, & Fiske, 2016)

Functional Impairment and Suicidal Ideation • In a critical review of 45 studies, we found strong support for the conclusion that functional impairment was associated with suicidal ideation in older adults. • Evidence suggested that depression mediates the relation between functional impairment and suicidal ideation, although most studies did not formally test for mediation. (Lutz & Fiske, 2918)

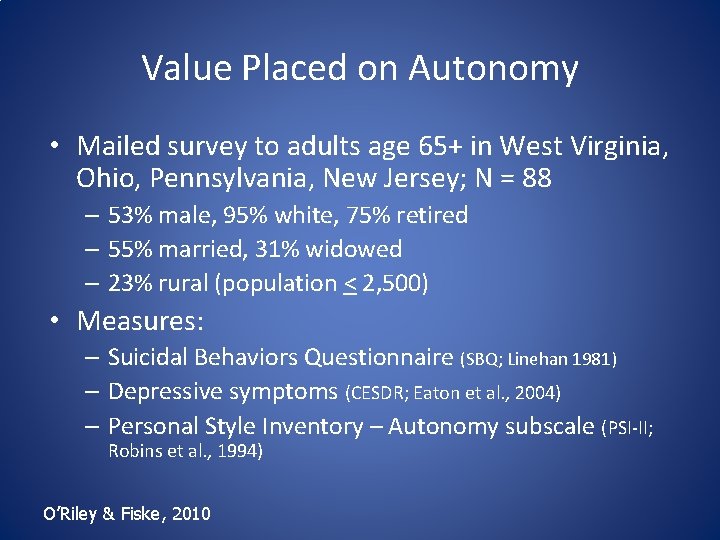

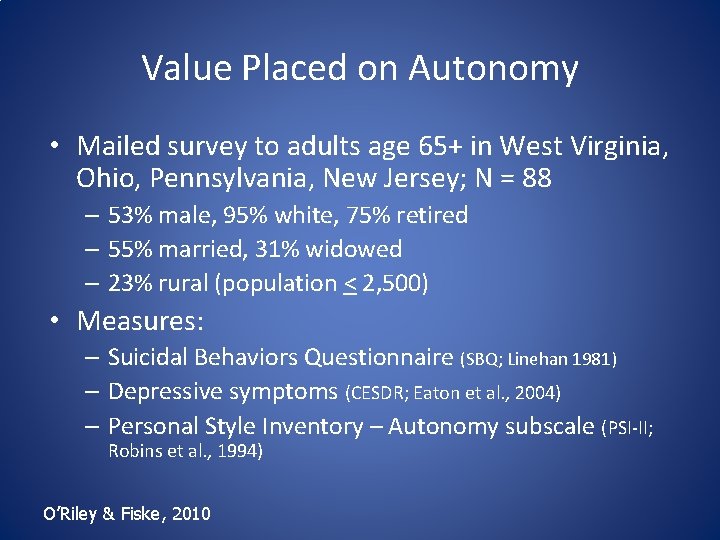

Value Placed on Autonomy • Mailed survey to adults age 65+ in West Virginia, Ohio, Pennsylvania, New Jersey; N = 88 – 53% male, 95% white, 75% retired – 55% married, 31% widowed – 23% rural (population < 2, 500) • Measures: – Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire (SBQ; Linehan 1981) – Depressive symptoms (CESDR; Eaton et al. , 2004) – Personal Style Inventory – Autonomy subscale (PSI-II; Robins et al. , 1994) O’Riley & Fiske, 2010

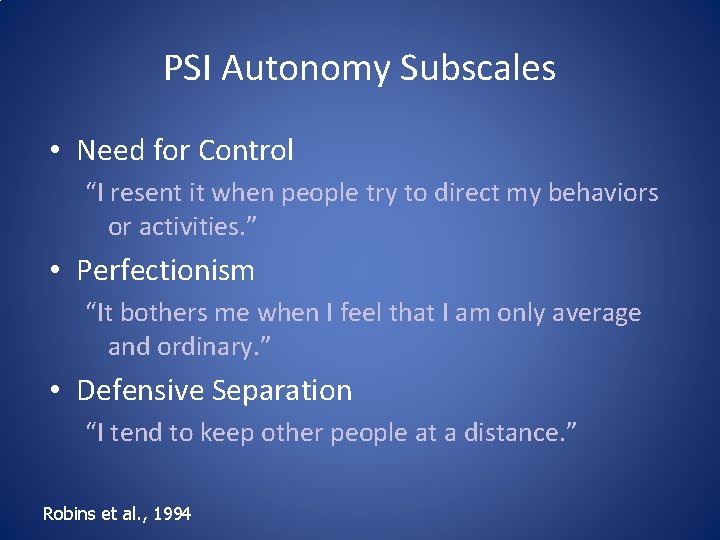

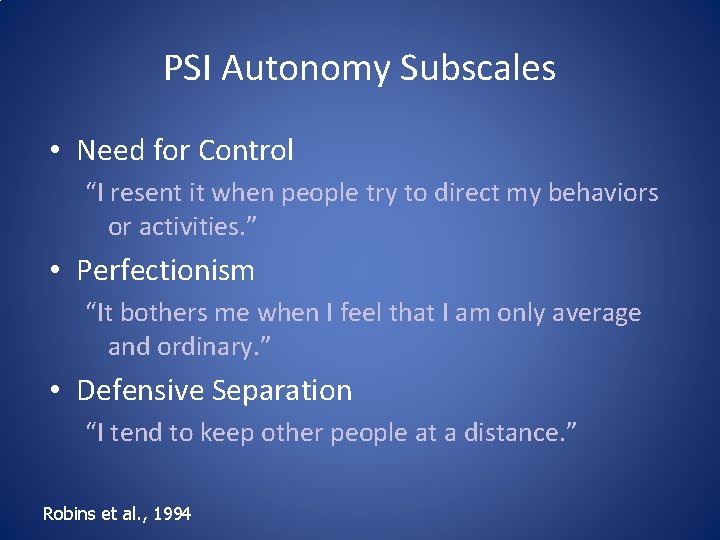

PSI Autonomy Subscales • Need for Control “I resent it when people try to direct my behaviors or activities. ” • Perfectionism “It bothers me when I feel that I am only average and ordinary. ” • Defensive Separation “I tend to keep other people at a distance. ” Robins et al. , 1994

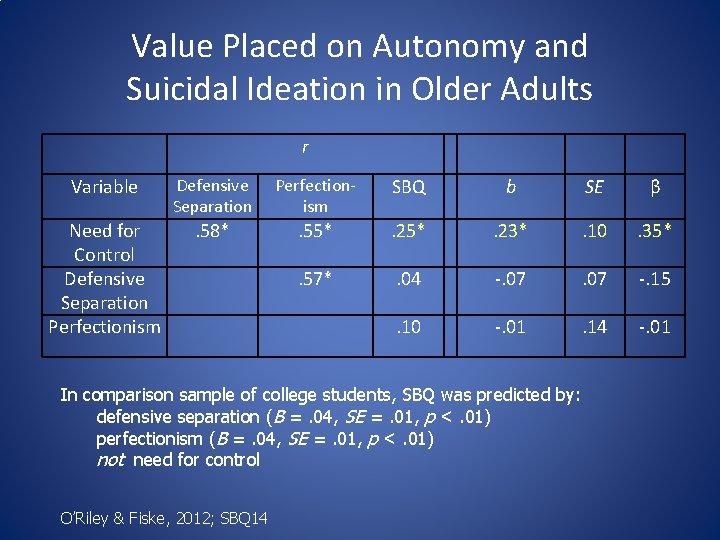

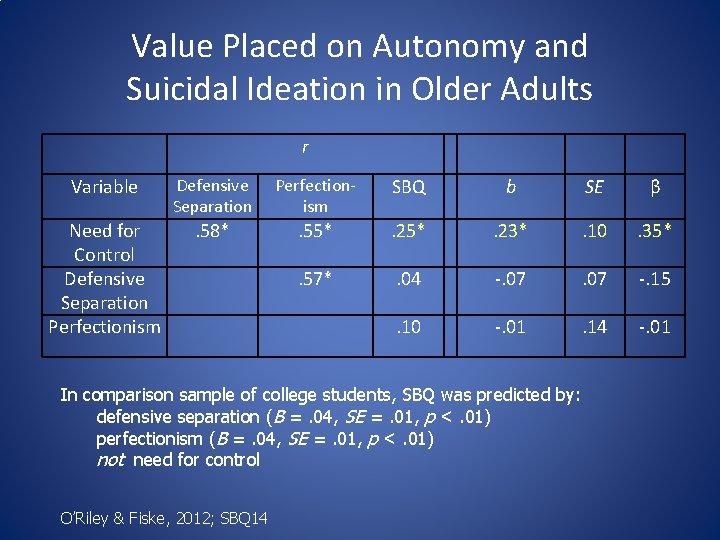

Value Placed on Autonomy and Suicidal Ideation in Older Adults r Variable Defensive Separation Perfectionism SBQ b SE β Need for Control Defensive Separation Perfectionism . 58* . 55* . 23* . 10 . 35* . 57* . 04 -. 07 -. 15 . 10 -. 01 . 14 -. 01 In comparison sample of college students, SBQ was predicted by: defensive separation (B =. 04, SE =. 01, p <. 01) perfectionism (B =. 04, SE =. 01, p <. 01) not need for control O’Riley & Fiske, 2012; SBQ 14

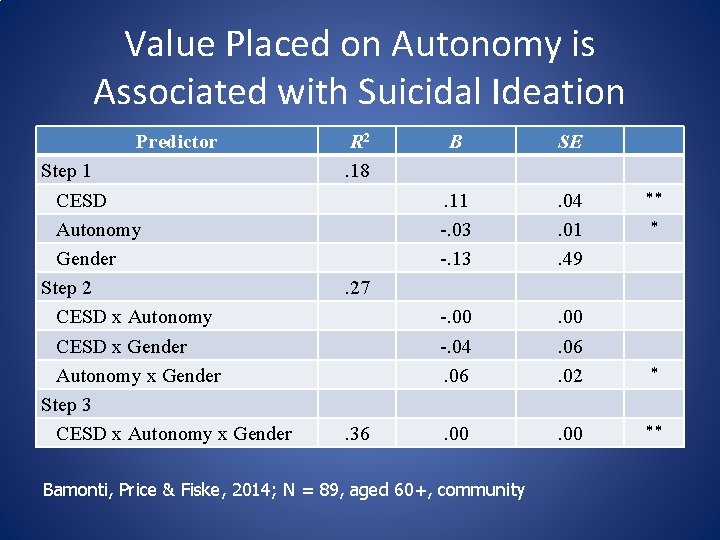

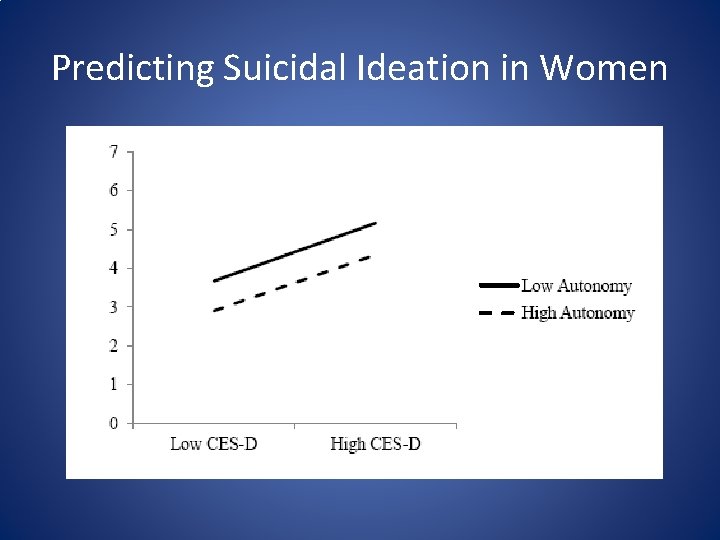

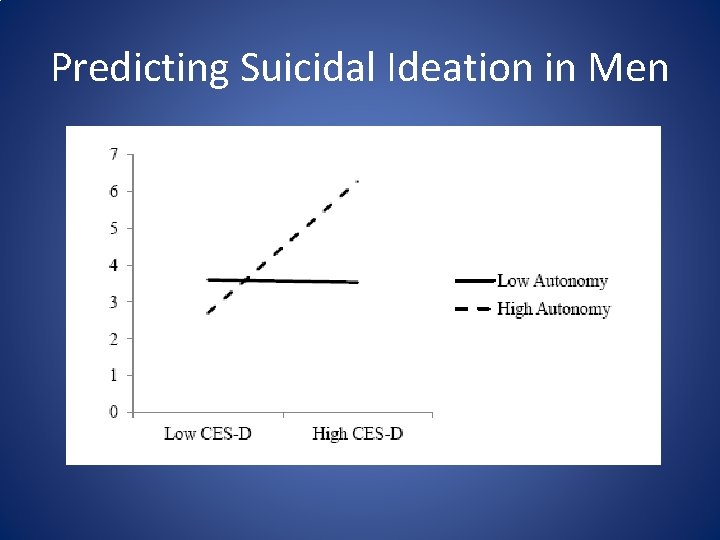

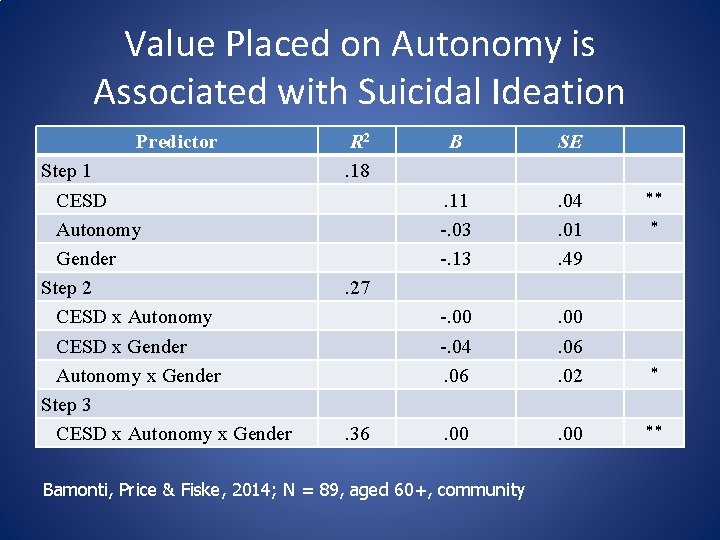

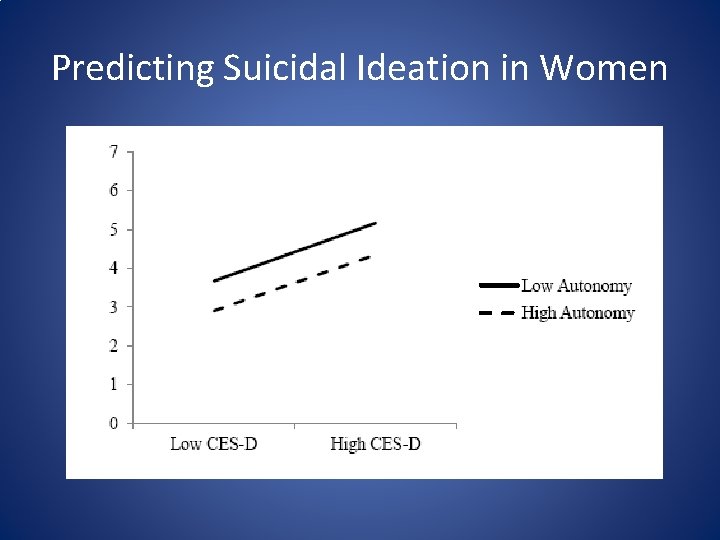

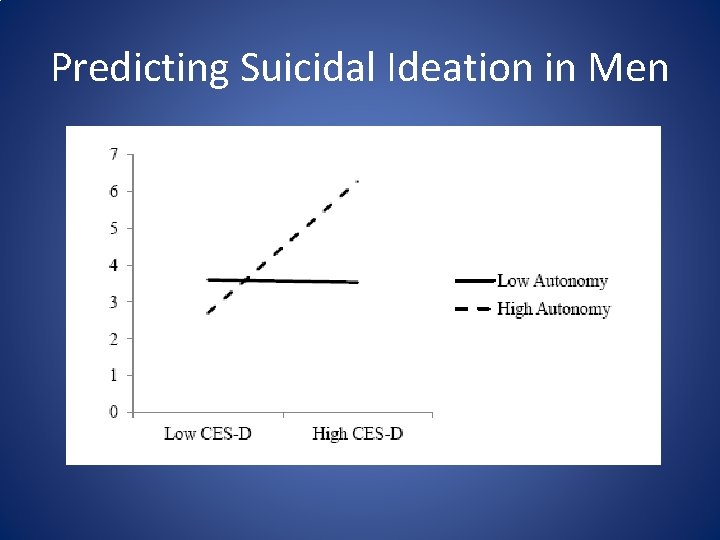

Value Placed on Autonomy is Associated with Suicidal Ideation Predictor Step 1 CESD Autonomy Gender Step 2 CESD x Autonomy CESD x Gender Autonomy x Gender Step 3 CESD x Autonomy x Gender R 2. 18 B SE . 11 -. 03 -. 13 . 04. 01. 49 -. 00 -. 04. 06 . 00. 06. 02 * . 00 ** ** * . 27 . 36 Bamonti, Price & Fiske, 2014; N = 89, aged 60+, community

Predicting Suicidal Ideation in Women

Predicting Suicidal Ideation in Men

Control Strategies Control Process Description Goal Engagement Selective Primary Control Invest behavior, effort, time, skills, persistence. Selective Secondary Control Volitional self-regulation to enhance motivational commitment to chosen goal. Avoid distractions, enhance perceived control, imagine positive incentives of goal attainment. Compensatory Primary Control Seek out help or unusual means or ways to overcome shortfall of primary control resources. Goal Disengagement (Compensatory Secondary Control) Distancing from Goal Devalue chosen goal, downgrade importance of goal, enhance value of conflicting goals. Self-Protection Protect motivational resources from negative implications of failure or loss experiences. Heckhausen, Wrosch, & Schulz, 2010

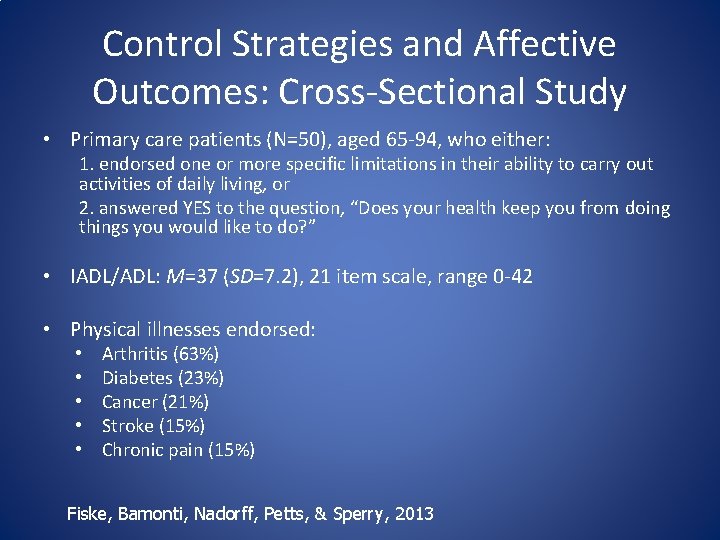

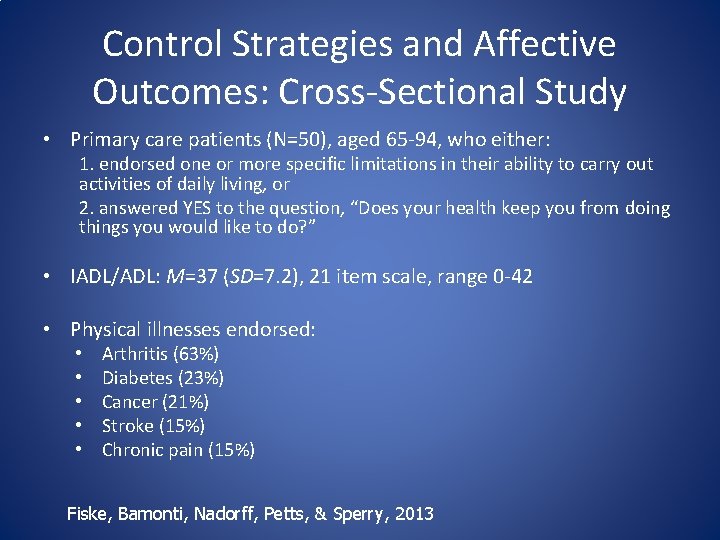

Control Strategies and Affective Outcomes: Cross-Sectional Study • Primary care patients (N=50), aged 65 -94, who either: 1. endorsed one or more specific limitations in their ability to carry out activities of daily living, or 2. answered YES to the question, “Does your health keep you from doing things you would like to do? ” • IADL/ADL: M=37 (SD=7. 2), 21 item scale, range 0 -42 • Physical illnesses endorsed: • • • Arthritis (63%) Diabetes (23%) Cancer (21%) Stroke (15%) Chronic pain (15%) Fiske, Bamonti, Nadorff, Petts, & Sperry, 2013

Additional Sample Characteristics • • • Female (60%) White (96%) Married (62%) College degree (46%) Retired (61%) • Depressive symptoms (CESD-R): M=8. 1 (SD=10. 5), cutoff = 16 • Geriatric Suicidal Ideation Scale (GSIS): M=12. 0 (SD=3. 1), cutoff = 19 Fiske, Bamonti, Nadorff, Petts, & Sperry, 2013

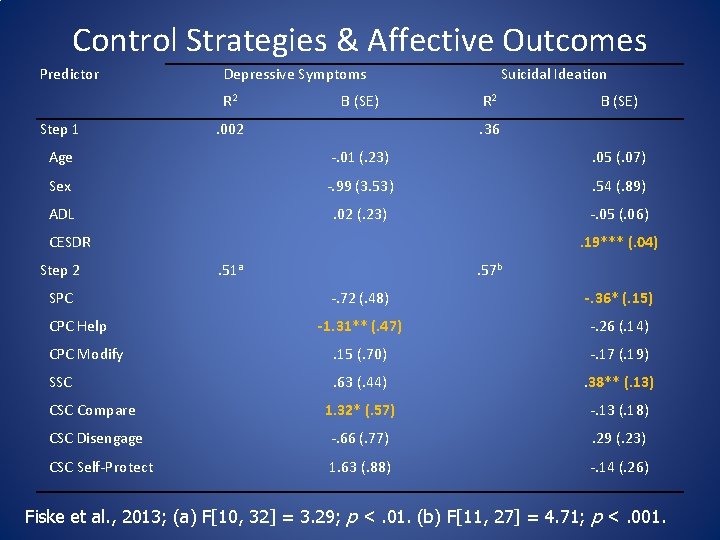

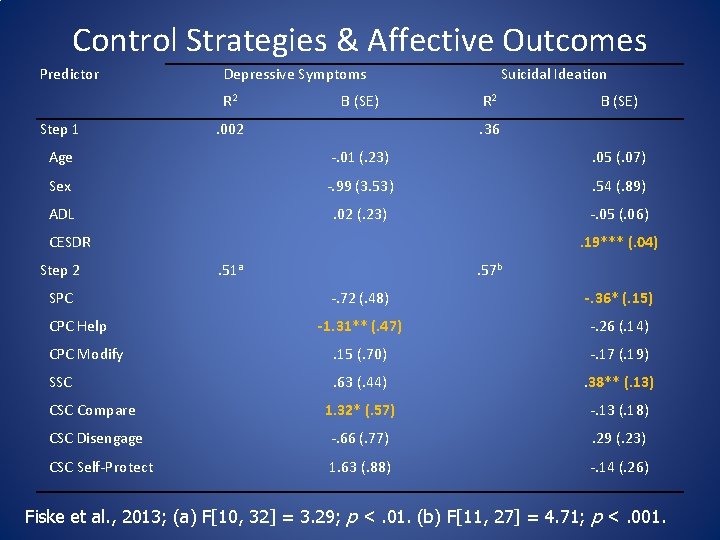

Control Strategies & Affective Outcomes Predictor Depressive Symptoms R 2 Step 1 B (SE) . 002 Suicidal Ideation R 2 B (SE) . 36 Age -. 01 (. 23) . 05 (. 07) Sex -. 99 (3. 53) . 54 (. 89) ADL . 02 (. 23) -. 05 (. 06) CESDR Step 2 SPC . 19*** (. 04). 51 a . 57 b -. 72 (. 48) -. 36* (. 15) -1. 31** (. 47) -. 26 (. 14) CPC Modify . 15 (. 70) -. 17 (. 19) SSC . 63 (. 44) . 38** (. 13) CSC Compare 1. 32* (. 57) -. 13 (. 18) CSC Disengage -. 66 (. 77) . 29 (. 23) CSC Self-Protect 1. 63 (. 88) -. 14 (. 26) CPC Help Fiske et al. , 2013; (a) F[10, 32] = 3. 29; p <. 01. (b) F[11, 27] = 4. 71; p <. 001.

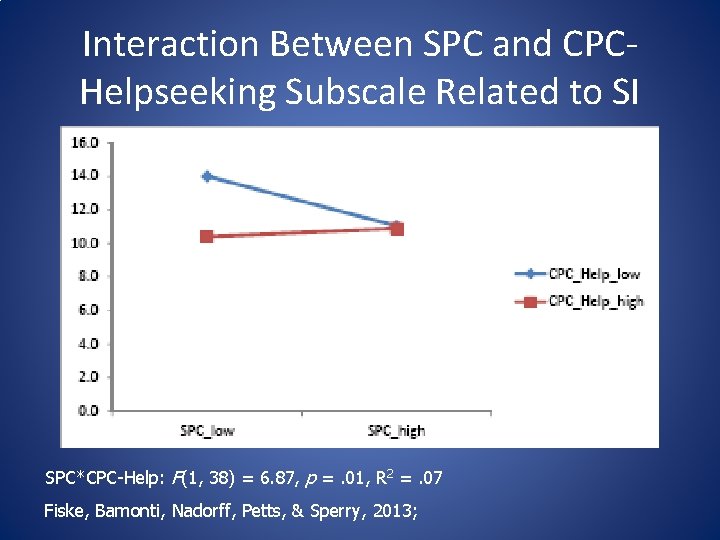

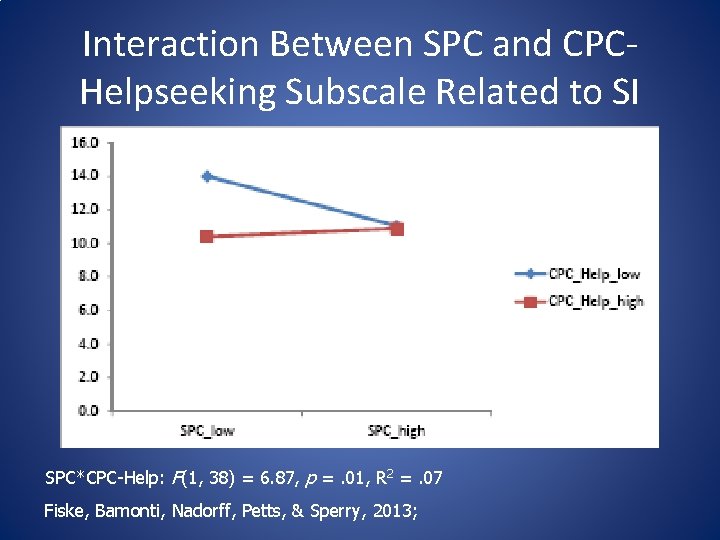

Interaction Between SPC and CPCHelpseeking Subscale Related to SI SPC*CPC-Help: F(1, 38) = 6. 87, p =. 01, R 2 =. 07 Fiske, Bamonti, Nadorff, Petts, & Sperry, 2013;

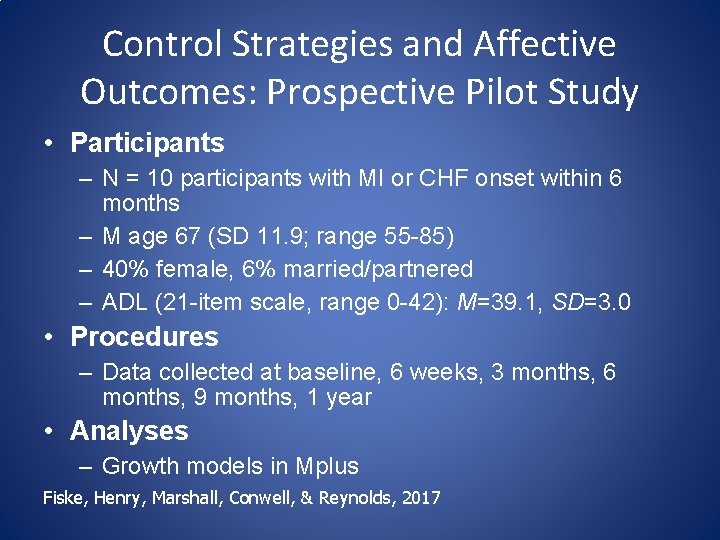

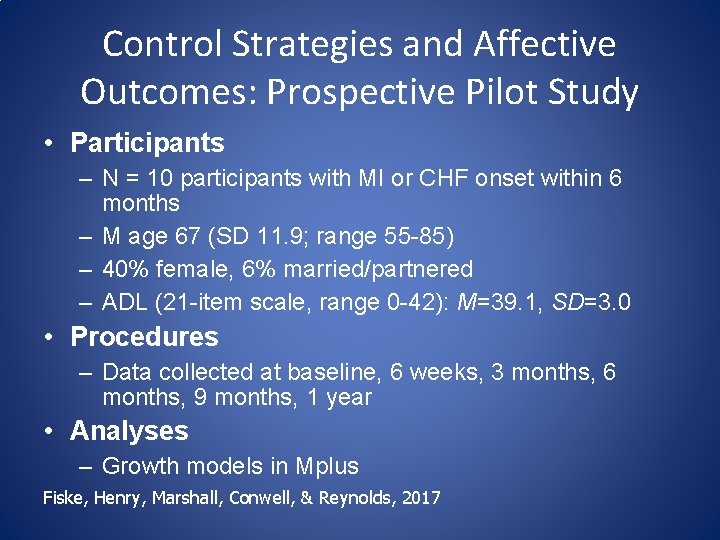

Control Strategies and Affective Outcomes: Prospective Pilot Study • Participants – N = 10 participants with MI or CHF onset within 6 months – M age 67 (SD 11. 9; range 55 -85) – 40% female, 6% married/partnered – ADL (21 -item scale, range 0 -42): M=39. 1, SD=3. 0 • Procedures – Data collected at baseline, 6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, 9 months, 1 year • Analyses – Growth models in Mplus Fiske, Henry, Marshall, Conwell, & Reynolds, 2017

Cross-Sectional Results • In cross-sectional models, CPC was significantly associated with change in depressive symptoms (CESDR) at 6 mo. , 9 mo. , 1 yr, and change in hopelessness (BHS) and suicidal ideation (GSIS) at every time point. • SPC was significantly associated with change in depressive symptoms (CESDR) at 3 mo. , 6 mo. , 9 mo. , change in hopelessness (BHS) at 9 mo. , and change in suicidal ideation (GSIS) at 6 mo. and 9 mo. Fiske, Henry, Marshall, Conwell, & Reynolds, 2017

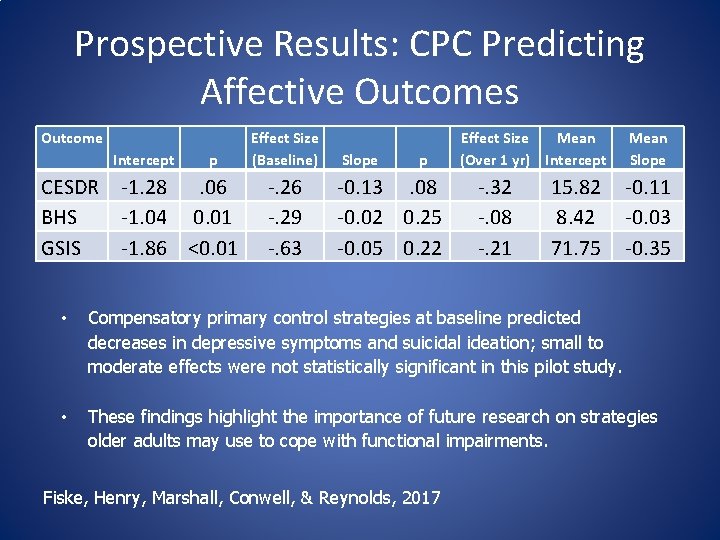

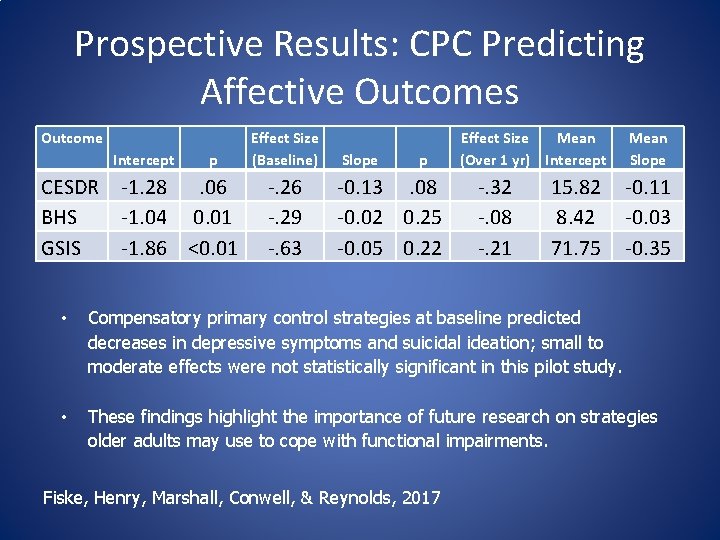

Prospective Results: CPC Predicting Affective Outcomes Outcome Intercept p CESDR -1. 28. 06 BHS -1. 04 0. 01 GSIS -1. 86 <0. 01 Effect Size (Baseline) -. 26 -. 29 -. 63 Slope p -0. 13. 08 -0. 02 0. 25 -0. 05 0. 22 Effect Size Mean (Over 1 yr) Intercept -. 32 -. 08 -. 21 15. 82 8. 42 71. 75 Mean Slope -0. 11 -0. 03 -0. 35 • Compensatory primary control strategies at baseline predicted decreases in depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation; small to moderate effects were not statistically significant in this pilot study. • These findings highlight the importance of future research on strategies older adults may use to cope with functional impairments. Fiske, Henry, Marshall, Conwell, & Reynolds, 2017

Cognitive Flexibility Predicting Affective Outcomes • Cognitive flexibility = (lack of) perseverative errors on the Wisconsin Card Sort Test • Correlated with SPC: -. 12; CPC: -. 59; SSC: . 16; CSC: -. 16 • Perseveration errors: – Significantly predicted change in hopelessness (BHS), with moderate effect size – Did not significantly predict suicidal ideation (GSIS) or depressive symptoms (CESD-R), probably due to small sample; effects were moderate and small-moderate, respectively.

Engagement in Pleasant Events Associated with Affective Outcomes • Sample included N=82 adults aged 60 -90 – 65% female, 98% White • Mediation analyses found that physical disability was associated with greater depressive symptoms, lower positive affect and lower meaning in life indirectly through engagement in pleasant events. • Behavioral therapy is an empirically supported treatment for older adults, but may require adaptation for persons with disabilities. Bamonti & Fiske, 2019

Proposed Pathway to Suicidal Ideation in Late Life Fiske & O’Riley, 2016

Future Directions • Test whether relation between functional impairment and affective outcomes is moderated by coping strategies. • Test whether control strategies predict affective outcomes prospectively in a larger sample of older adults with significant functional impairments. • Develop interventions to enhance control strategies (e. g. , encourage flexibility, facilitate help-seeking) and test whether they alter affective outcomes. • Test whether value placed on autonomy or cognitive flexibility predict use of control strategies.

Conclusions • Suicide rates are particularly high among older men • Physical illness is associated with suicide, especially if accompanied by functional impairment • A lifespan developmental perspective suggests that control strategies may moderate the relation between functional impairment and affective outcomes. • Value placed on autonomy and cognitive flexibility are associated with affective outcomes, and may influence the likelihood that control strategies will be employed. • Reduced engagement in pleasant events explains the relation between disability and depression.

Acknowledgements • NIMH Grant No. R 15 MH-80399 • Chandra Reynolds, Ph. D, University of California Riverside • WVU Mental Health and Aging Laboratory

Amy Fiske, Ph. D. Associate Professor West Virginia University Department of Psychology (304) 293 -1708 Amy. Fiske@mail. wvu. edu