The role of childdirected speech in first language

- Slides: 25

The role of child-directed speech in first language acquisition Sonja Eisenbeiss seisen@essex. ac. uk http: //essex. academia. edu/Sonja. Eisenbeiss/ http: //languagegamesforall. wordpress. com/ @Language. Games 4 a

Child-Directed Speech: Other Terms § Baby talk § Motherese § Parentese § Caretaker speech § Infant-directed speech

Some Common Myths about Child-Directed Speech § When talking to children adults mostly label objects and describe ongoing events for children. § Spoken speech contains many speech errors and incomplete utterances – especially when you have to manage difficult situations with a child. § Parents systematically correct their children’s errors. § “Motherese” is instinctive and does not differ much across cultures.

And the reality ? ? ? Is more complex….

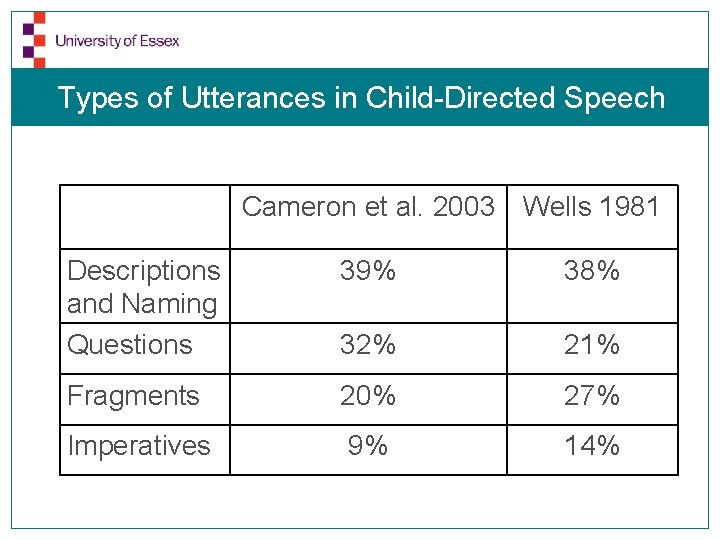

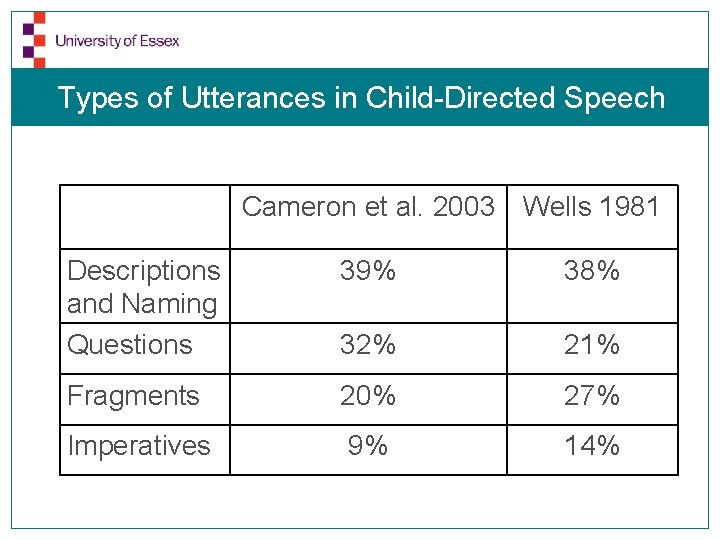

Types of Utterances in Child-Directed Speech Cameron et al. 2003 Wells 1981 Descriptions and Naming Questions 39% 38% 32% 21% Fragments 20% 27% Imperatives 9% 14%

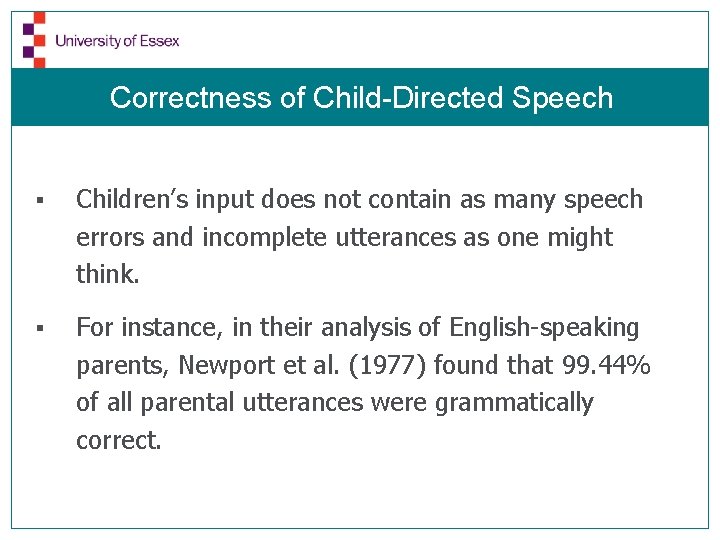

Correctness of Child-Directed Speech § Children’s input does not contain as many speech errors and incomplete utterances as one might think. § For instance, in their analysis of English-speaking parents, Newport et al. (1977) found that 99. 44% of all parental utterances were grammatically correct.

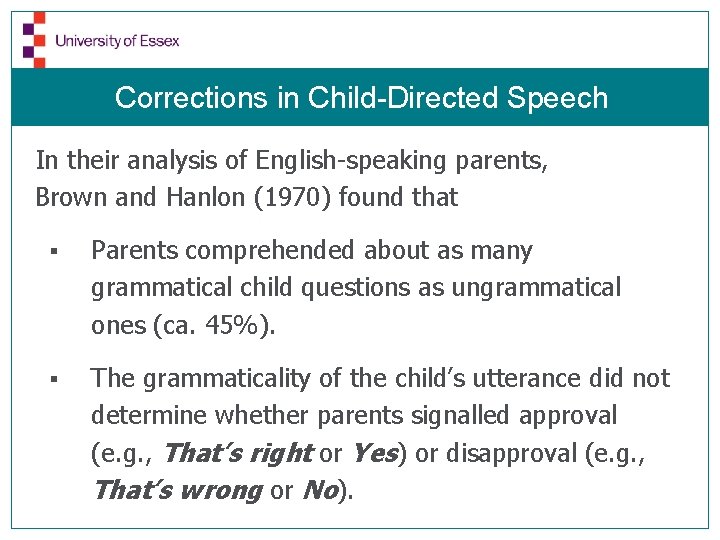

Corrections in Child-Directed Speech In their analysis of English-speaking parents, Brown and Hanlon (1970) found that § Parents comprehended about as many grammatical child questions as ungrammatical ones (ca. 45%). § The grammaticality of the child’s utterance did not determine whether parents signalled approval (e. g. , That’s right or Yes) or disapproval (e. g. , That’s wrong or No).

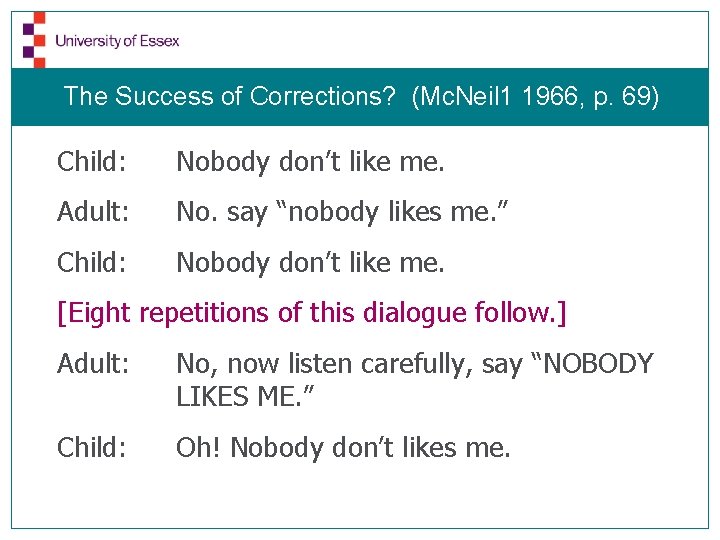

The Success of Corrections? (Mc. Neil 1 1966, p. 69) Child: Nobody don’t like me. Adult: No. say “nobody likes me. ” Child: Nobody don’t like me. [Eight repetitions of this dialogue follow. ] Adult: No, now listen carefully, say “NOBODY LIKES ME. ” Child: Oh! Nobody don’t likes me.

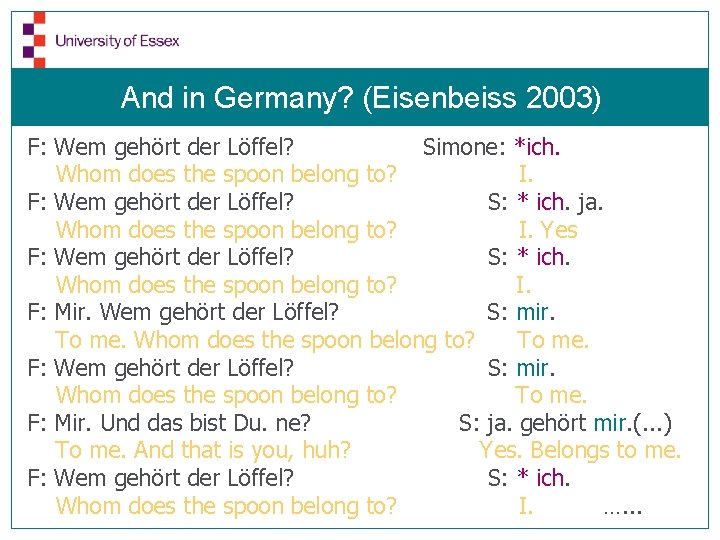

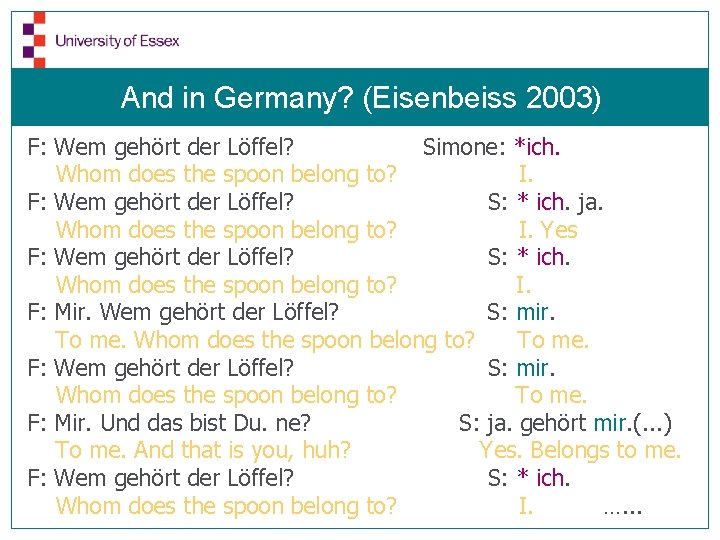

And in Germany? (Eisenbeiss 2003) F: Wem gehört der Löffel? Simone: *ich. Whom does the spoon belong to? I. F: Wem gehört der Löffel? S: * ich. ja. Whom does the spoon belong to? I. Yes F: Wem gehört der Löffel? S: * ich. Whom does the spoon belong to? I. F: Mir. Wem gehört der Löffel? S: mir. To me. Whom does the spoon belong to? To me. F: Wem gehört der Löffel? S: mir. Whom does the spoon belong to? To me. F: Mir. Und das bist Du. ne? S: ja. gehört mir. (. . . ) To me. And that is you, huh? Yes. Belongs to me. F: Wem gehört der Löffel? S: * ich. Whom does the spoon belong to? I. …. . .

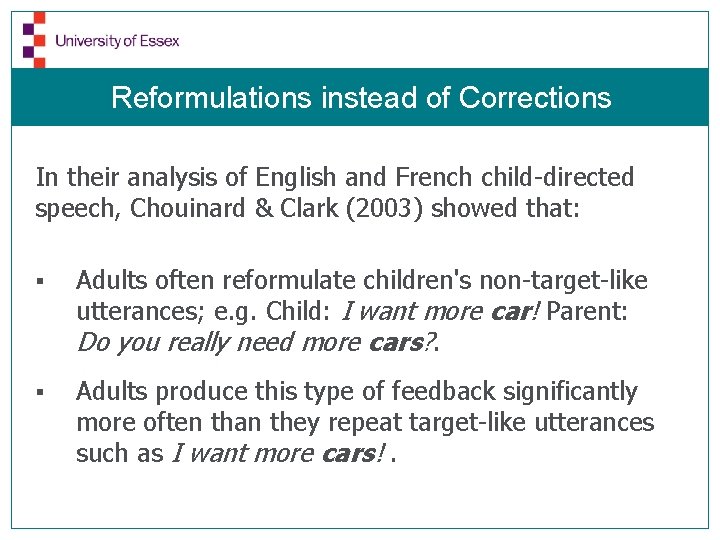

Reformulations instead of Corrections In their analysis of English and French child-directed speech, Chouinard & Clark (2003) showed that: § Adults often reformulate children's non-target-like utterances; e. g. Child: I want more car! Parent: Do you really need more cars? . § Adults produce this type of feedback significantly more often than they repeat target-like utterances such as I want more cars!.

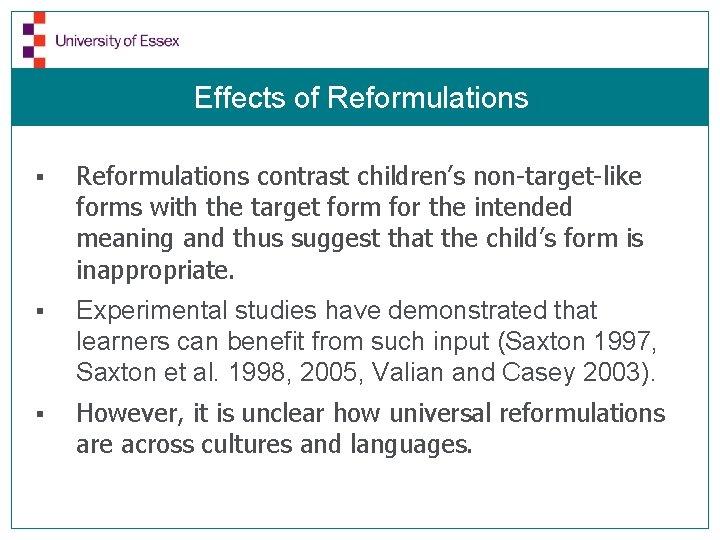

Effects of Reformulations § Reformulations contrast children’s non-target-like forms with the target form for the intended meaning and thus suggest that the child’s form is inappropriate. § Experimental studies have demonstrated that learners can benefit from such input (Saxton 1997, Saxton et al. 1998, 2005, Valian and Casey 2003). § However, it is unclear how universal reformulations are across cultures and languages.

Cross-Cultural Differences § the amount of feedback provided § views on the need of explicit language teaching § time children spent interacting with adults vs. other children § the role of fathers (Gallaway/Richards 1994 , Ochs/Schieffelin 1984)

Some Universals of Child-Directed Speech § short, but mostly correct and complete utterances § slow, with longer pauses than adult-directed speech high, varied pitch, exaggerated intonation and stress => identification of word and phrase boundaries restricted vocabulary reference mostly restricted to here and now => word learning high proportion of imperative and questions more repetitions than in adult-adult speech => sentence structure and grammar § § §

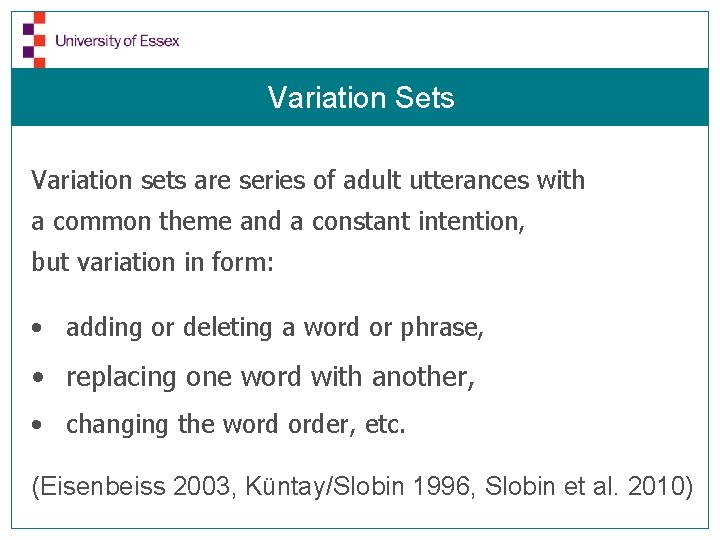

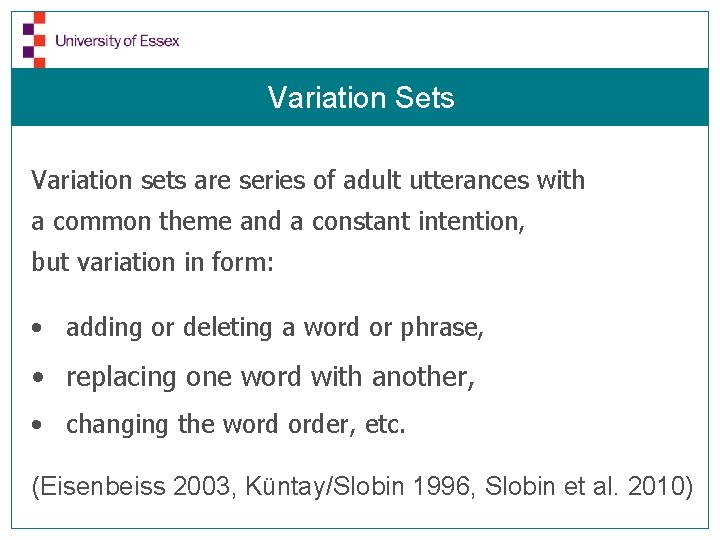

Variation Sets Variation sets are series of adult utterances with a common theme and a constant intention, but variation in form: • adding or deleting a word or phrase, • replacing one word with another, • changing the word order, etc. (Eisenbeiss 2003, Küntay/Slobin 1996, Slobin et al. 2010)

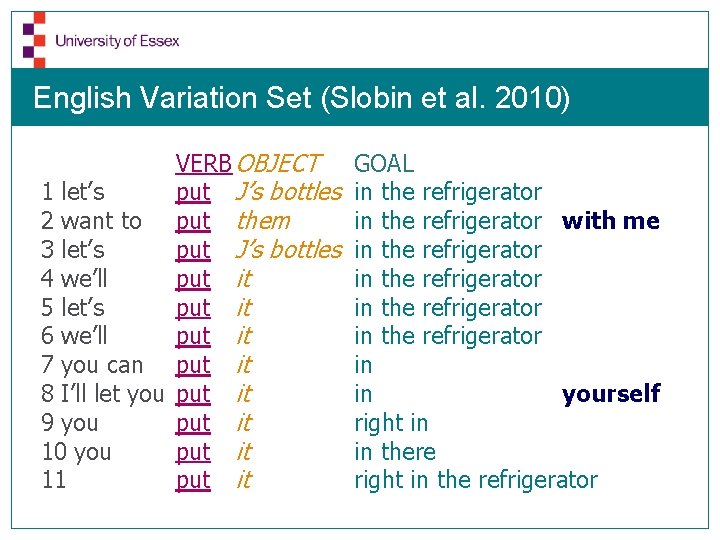

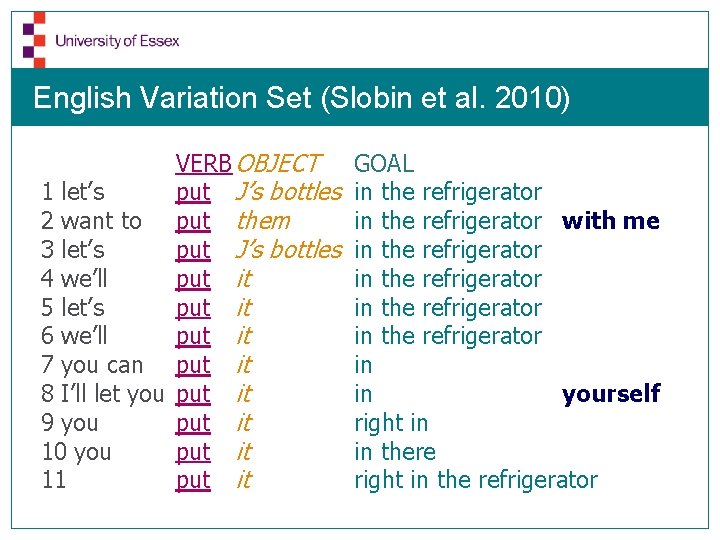

English Variation Set (Slobin et al. 2010) VERB OBJECT 1 let’s put J’s bottles 2 want to put them 3 let’s put J’s bottles 4 we’ll put it 5 let’s put it 6 we’ll put it 7 you can put it 8 I’ll let you put it 9 you put it 10 you put it 11 put it GOAL in the refrigerator with me in the refrigerator in in yourself right in in there right in the refrigerator

How could Variation Sets support Learning? Variation sets provide clues about the target language: • adding or deleting a word or phrase => which elements can be omitted? • replacing one word with another => which types of elements fulfill similar functions? • changing the word order, etc. => which word order variations are possible?

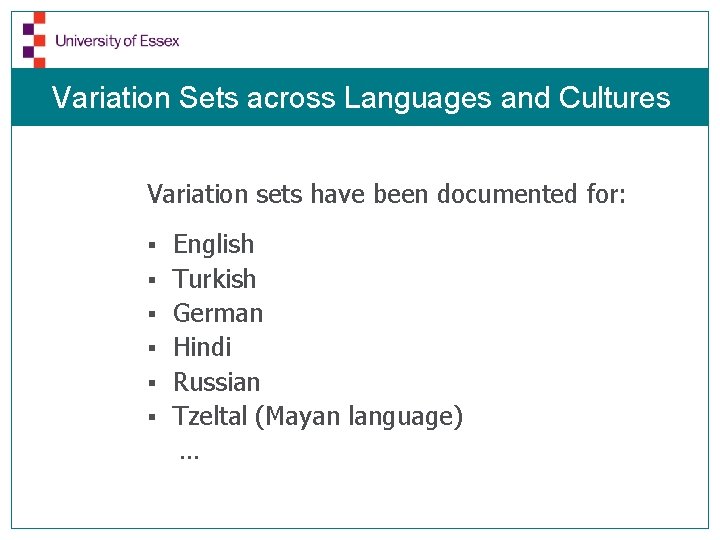

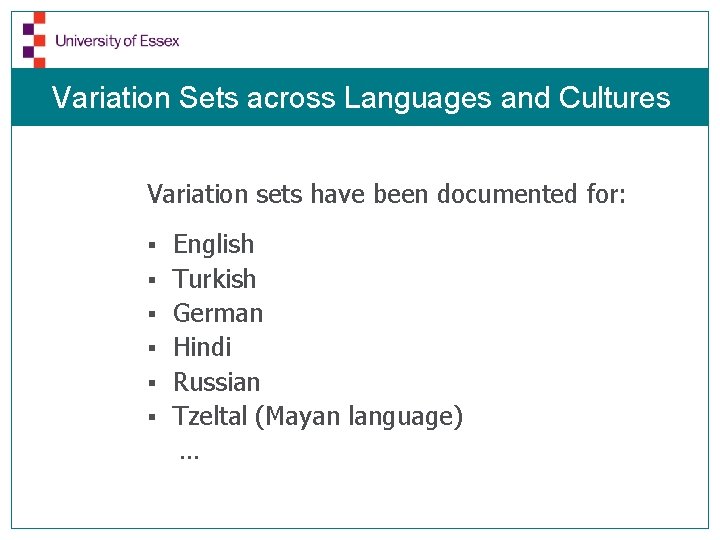

Variation Sets across Languages and Cultures Variation sets have been documented for: § § § English Turkish German Hindi Russian Tzeltal (Mayan language) …

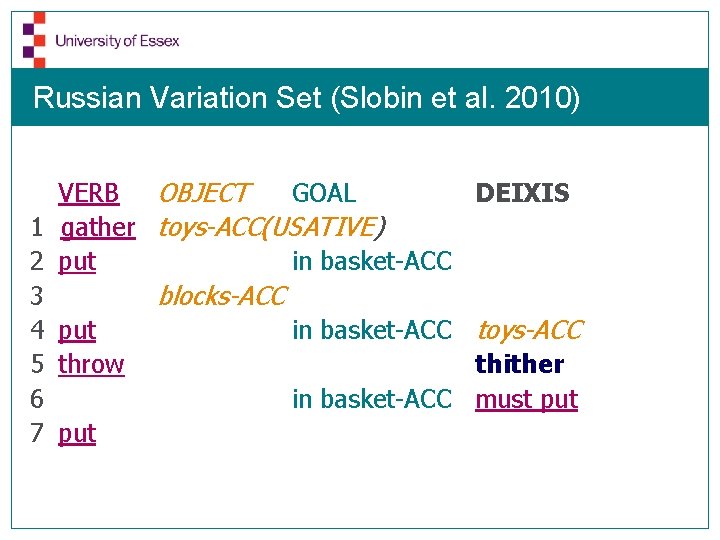

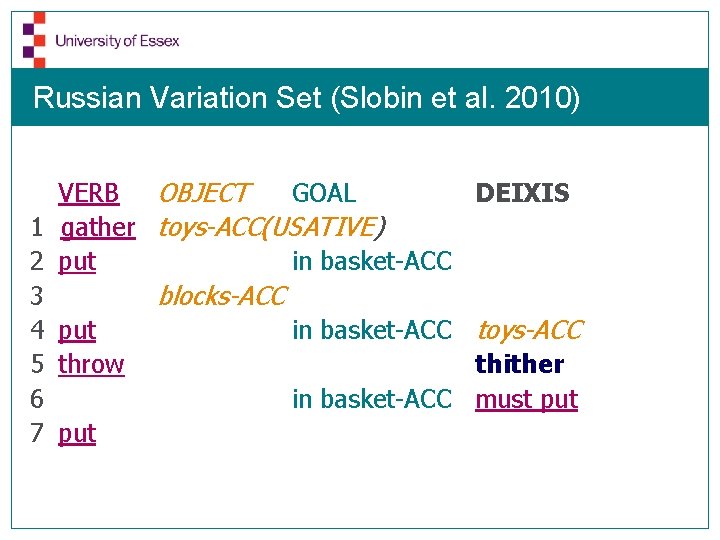

Russian Variation Set (Slobin et al. 2010) VERB OBJECT GOAL 1 gather toys-ACC(USATIVE) 2 put in basket-ACC 3 blocks-ACC 4 put in basket-ACC 5 throw 6 in basket-ACC 7 put DEIXIS toys-ACC thither must put

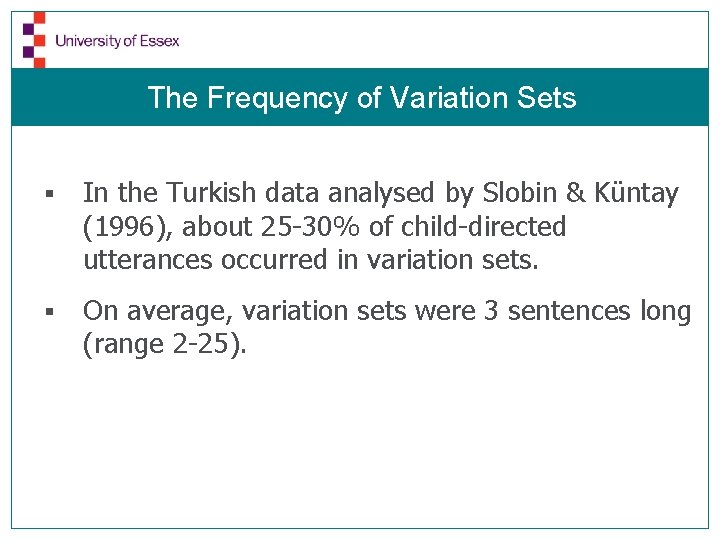

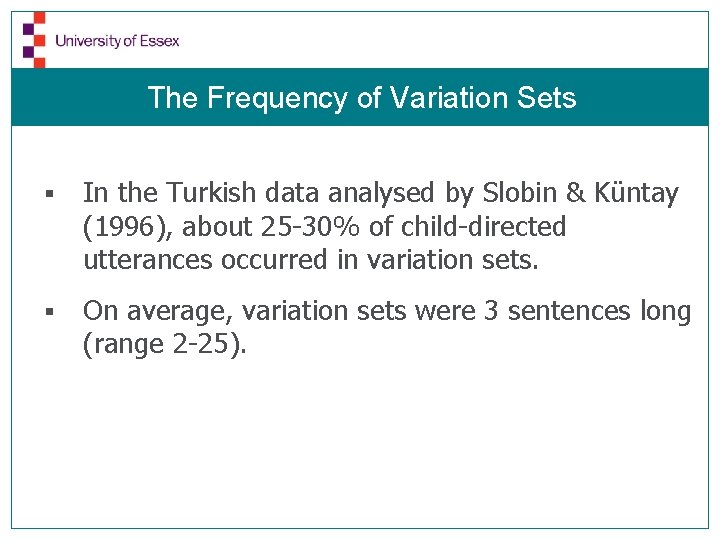

The Frequency of Variation Sets § In the Turkish data analysed by Slobin & Küntay (1996), about 25 -30% of child-directed utterances occurred in variation sets. § On average, variation sets were 3 sentences long (range 2 -25).

Effects of Variation Sets § Children produce words that they have heard in variation sets more often than words they have heard in other utterances – even when frequency is controlled for (ongoing research by H. Waterfall). § Adult learners learn artificial languages more easily when their training involves variation sets (Onnis et al. 2008).

Current Research Projects Involving Students § How do parents talk to their children when they play different types of (language) games? § Do some types of games encourage parents to use more variation sets or other potentially supportive properties of child-directed speech than others? § Do some games encourage children to talk more than others? § See: https: //languagegamesforall. wordpress. com/

References Brown, R. , & Hanlon, C. (1970) Derivational complexity and the order of acquisition in child speech. In: J. R. Hayes (Ed. ), Cognition and the development of language (pp. 11 -53). New York: Wiley. Cameron-Faulkner, T. , Lieven, E. , Tomasello, M. (2003). A construction based analysis of child directed speech. Cognitive Science 27, 843– 873. Chouinard, M. M. & Clark, E. V. (2003) Adult reformulation of child errors as negative evidence. Journal of Child Language 30: 637– 69. Eisenbeiss, S. 2003. Merkmalsgesteuerter Grammatikerwerb. Doctoral dissertation, University of Düsseldorf, Germany. "http: //docserv. uniduesseldorf. de/servlets/Derivate. Servlet/Derivate-3185/1185. pdf")

References Gallaway, C. and Richards, B. (eds. ) (1994). Input and interaction in language acquisition. London: Cambridge University Press. Küntay, A. , & Slobin, D. I. (1996). Listening to a Turkish mother: Some puzzles for acquisition. In D. I. Slobin, J. Gerhardt, A. Kyratzis, & J. Guo (Eds. ), Social interaction, social context, and language: Essays in honor of Susan Ervin-Tripp (pp. 265 -286). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Newport, E. L. , Gleitman, H. , & Gleitman, L. R. (1977). Mother, I’d rather do it myself: Some effects and non-effects of maternal speech style. In C. E. Snow & CA. Ferguson (Eds. ), Talking to children: Language inpuf and acquisition (pp. 109 -149). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

References Ochs, E. , & Schieffelin, B. B. (1984). Language acquisition and socialization: Three developmental stories and their implications. In R. A. Shweder & R. A. Levine (Eds. ), Culture theory: Essays on mind, self and emotion. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Onnis, L. , Waterfall, H. R. , and Edelman, S. (2008). Learn locally, act globally: Learning language from variation set cues. Cognition 109, 423 -430. Saxton, M. , Kulscar, B. Marshall and Rupra, M. (1998). Longer-term effects of corrective input: An experimental approach. Journal of Child Language 5: 701 -21. Saxton, Matthew, Backley, Phillip, Gallaway, Clare, (2005). Negative input for grammatical errors: effects after a lag of 12 weeks. Journal of Child Language 32, 643– 672.

References Saxton, M. (1997). The contrast theory of negative input. Journal of Child Language 24, 139 -161. Slobin, Dan I. , Bowerman, Melissa, Brown, Penelope, Eisenbeiss, Sonja & Narasimhan, Bhuvana (2011). In: Jürgen Bohnemeyer and Eric Pederson (eds. ) Event Representation, 134 -165. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Valian, V. and Casey, L. (2003). Young children's acquisition of whquestions: the role of structured input. Journal of Child Language 30, 117 -143 Wells, C. G. (1981). Learning through interaction: The study of language development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Azure worker role

Azure worker role Lothar krappmann

Lothar krappmann Statuses and their related roles determine the structure

Statuses and their related roles determine the structure Difference of first language and second language

Difference of first language and second language Language

Language Hát kết hợp bộ gõ cơ thể

Hát kết hợp bộ gõ cơ thể Bổ thể

Bổ thể Tỉ lệ cơ thể trẻ em

Tỉ lệ cơ thể trẻ em Chó sói

Chó sói Chụp phim tư thế worms-breton

Chụp phim tư thế worms-breton Hát lên người ơi alleluia

Hát lên người ơi alleluia Môn thể thao bắt đầu bằng chữ f

Môn thể thao bắt đầu bằng chữ f Thế nào là hệ số cao nhất

Thế nào là hệ số cao nhất Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới

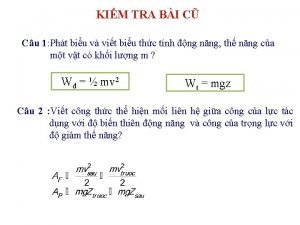

Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới Cong thức tính động năng

Cong thức tính động năng Trời xanh đây là của chúng ta thể thơ

Trời xanh đây là của chúng ta thể thơ Mật thư anh em như thể tay chân

Mật thư anh em như thể tay chân Làm thế nào để 102-1=99

Làm thế nào để 102-1=99 độ dài liên kết

độ dài liên kết Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới

Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới Thể thơ truyền thống

Thể thơ truyền thống Quá trình desamine hóa có thể tạo ra

Quá trình desamine hóa có thể tạo ra Một số thể thơ truyền thống

Một số thể thơ truyền thống Cái miệng nó xinh thế chỉ nói điều hay thôi

Cái miệng nó xinh thế chỉ nói điều hay thôi Vẽ hình chiếu vuông góc của vật thể sau

Vẽ hình chiếu vuông góc của vật thể sau