The Respiratory System Lecture in Normal Physiology Respiration

- Slides: 39

The Respiratory System Lecture in Normal Physiology

Respiration is the complex of processes by which an organism meets its requirements of oxygen and eliminates carbon dioxide. In man and the higher animals it comprises the following processes: n 1) exchange of air between the external environment and the pulmonary alveoli (external respiration or lung ventilation); n 2) exchange of gases between the alveolar air and the blood in the pulmonary capillaries (diffusion of gases in the lungs) n 3) transport of gases by the blood; n 4) exchange of gases between blood and tissues through the tissue capillaries (diffusion of gases in the tissues) ; n 5) consumption of oxygen by cells and the elimination of carbon dioxide (cell or internal respiration).

Non-respiratory functions of respiratory tract ■ 1. OLFACTION ■ 2. VOCALIZATION ■ 3. PREVENTION OF DUST PARTICLES ■ 4. DEFENSE MECHANISM ■ 5. MAINTENANCE OF WATER BALANCE ■ 6. REGULATION OF BODY TEMPERATURE

■ 7. REGULATION OF ACID BASE BALANCE Lungs play an important role in maintaining the acid base balance of the body by regulating the carbon dioxide content in blood. ■ 8. ANTICOAGULANT FUNCTION Lungs contain the mast cells, which secrete heparin. Heparin is an anticoagulant and it prevents the intravascular clotting. ■ 9. ACTIVATION OF ANGIOTENSIN I Endothelial cells of the pulmonary capillaries secrete the angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE). This converts the angiotensin I into active angiotensin II and regulates BP ■ 10. SYNTHESIS OF HORMONAL SUBSTANCES Lung tissues are also known to synthesize the hormonal

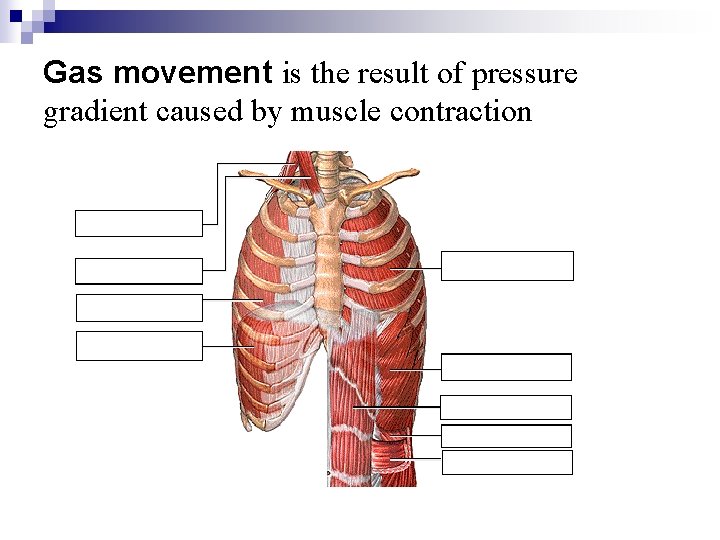

Gas movement is the result of pressure gradient caused by muscle contraction

Mechanics of Breathing Pulmonary ventilation consists of two phases: inspiration and expiration accomplished by alternately increasing and decreasing the volumes of the thorax and lungs. n Normal, quiet inspiration results from muscle contraction, and normal expiration – from muscle relaxation and elastic recoil. These actions can be forced by contractions of the accessory respiratory muscles. n The structure of the rib cage and associated cartilages provides continuous elastic tension, so that when stretched by muscle contraction during inspiration, the rib cage can return passively to its resting dimensions when the muscles relax. This elastic recoil is greatly aided by the elasticity of the lungs.

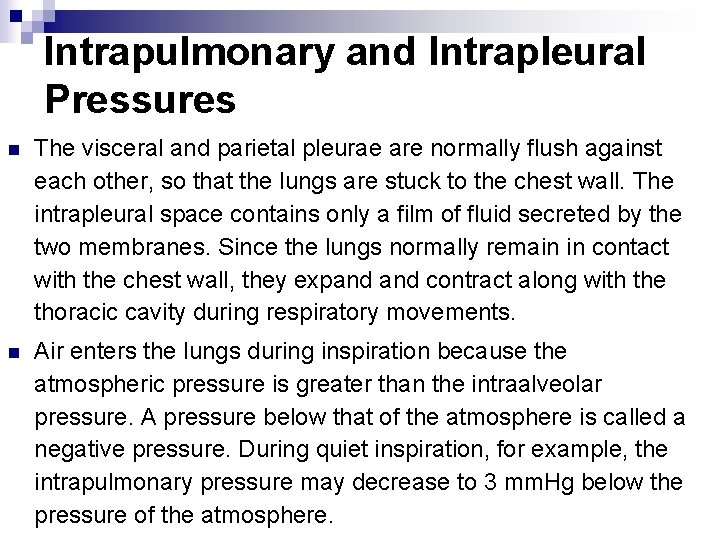

Intrapulmonary and Intrapleural Pressures n The visceral and parietal pleurae are normally flush against each other, so that the lungs are stuck to the chest wall. The intrapleural space contains only a film of fluid secreted by the two membranes. Since the lungs normally remain in contact with the chest wall, they expand contract along with the thoracic cavity during respiratory movements. n Air enters the lungs during inspiration because the atmospheric pressure is greater than the intraalveolar pressure. A pressure below that of the atmosphere is called a negative pressure. During quiet inspiration, for example, the intrapulmonary pressure may decrease to 3 mm. Hg below the pressure of the atmosphere.

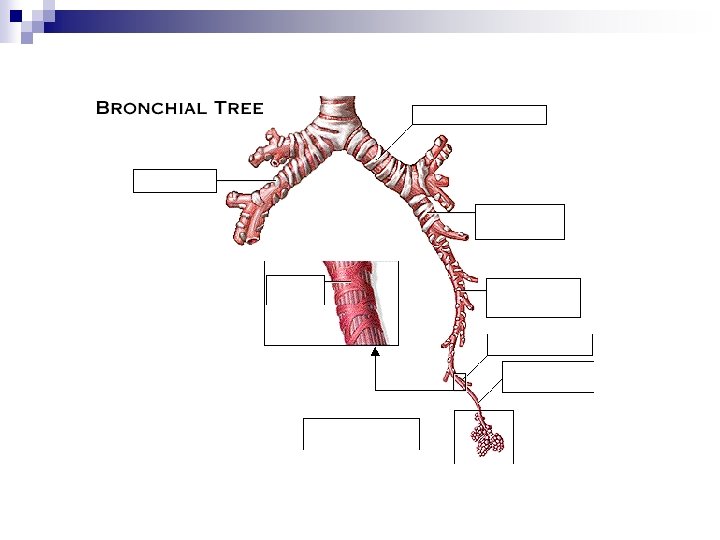

Respiratory tract is divided into a conducting zone, which conducts the air to the respiratory zone, and a respiratory zone, which is the site of gas exchange between air and blood. The exchange of gases between air and blood occurs across the walls of respiratory alveoli. These tiny air sacs, only a single cell layer thick, permit rapid rates of gas diffusion.

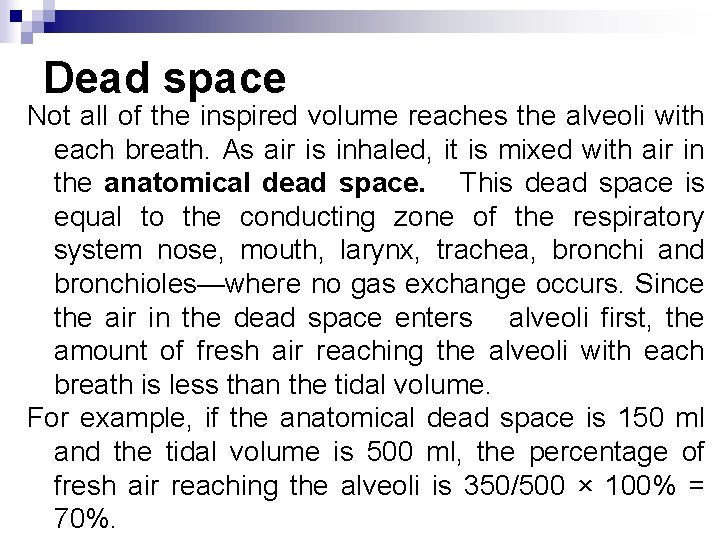

Dead space Not all of the inspired volume reaches the alveoli with each breath. As air is inhaled, it is mixed with air in the anatomical dead space. This dead space is equal to the conducting zone of the respiratory system nose, mouth, larynx, trachea, bronchi and bronchioles—where no gas exchange occurs. Since the air in the dead space enters alveoli first, the amount of fresh air reaching the alveoli with each breath is less than the tidal volume. For example, if the anatomical dead space is 150 ml and the tidal volume is 500 ml, the percentage of fresh air reaching the alveoli is 350/500 × 100% = 70%.

Movement of air, from higher to lower pressure, between the conducting zone and the terminal bronchioles occurs as a result of the pressure difference between the two ends of the airways. Air flow through bronchioles, like blood flow through blood vessels, is directly proportional to the pressure difference and inversely proportional to the frictional resistance to flow. n The pressure differences in the pulmonary system are induced by changes in lung volumes. n

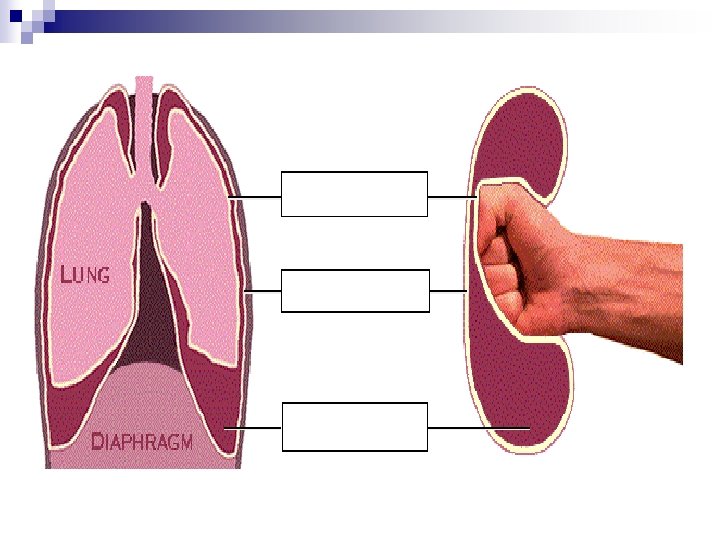

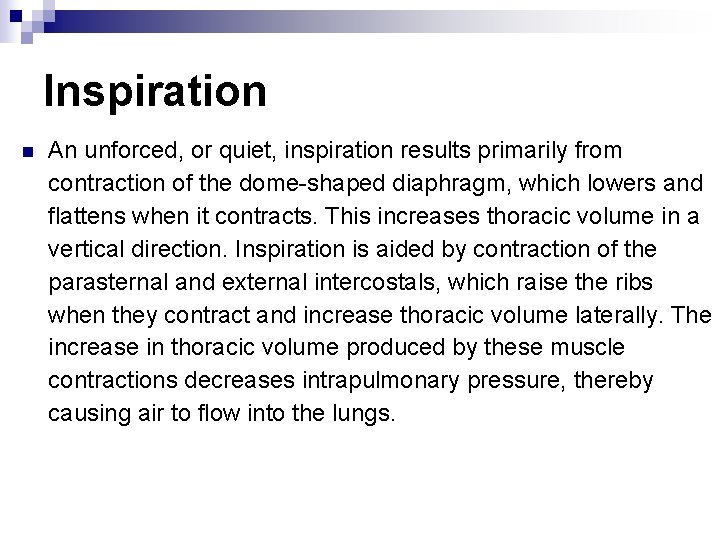

Inspiration n An unforced, or quiet, inspiration results primarily from contraction of the dome-shaped diaphragm, which lowers and flattens when it contracts. This increases thoracic volume in a vertical direction. Inspiration is aided by contraction of the parasternal and external intercostals, which raise the ribs when they contract and increase thoracic volume laterally. The increase in thoracic volume produced by these muscle contractions decreases intrapulmonary pressure, thereby causing air to flow into the lungs.

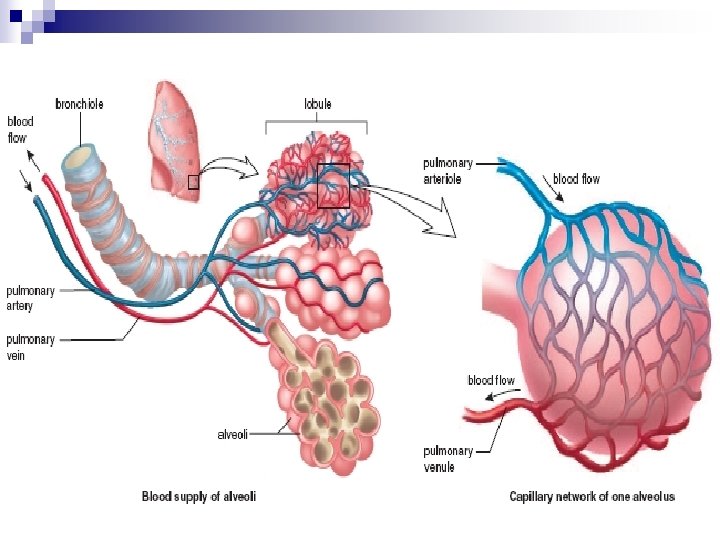

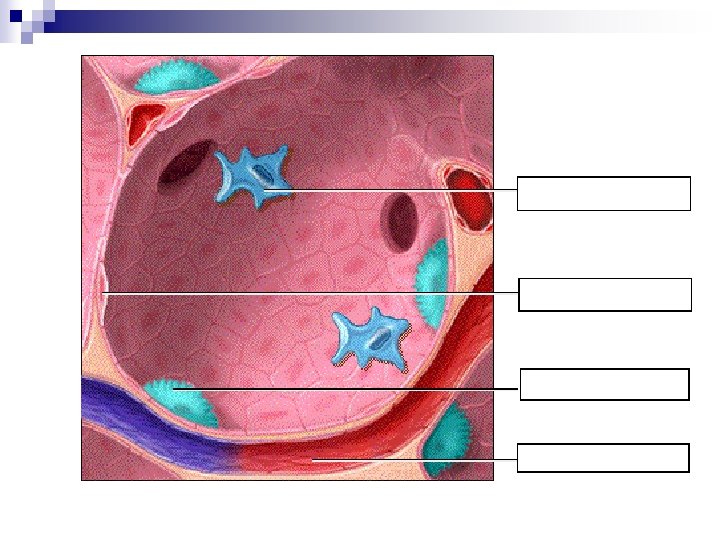

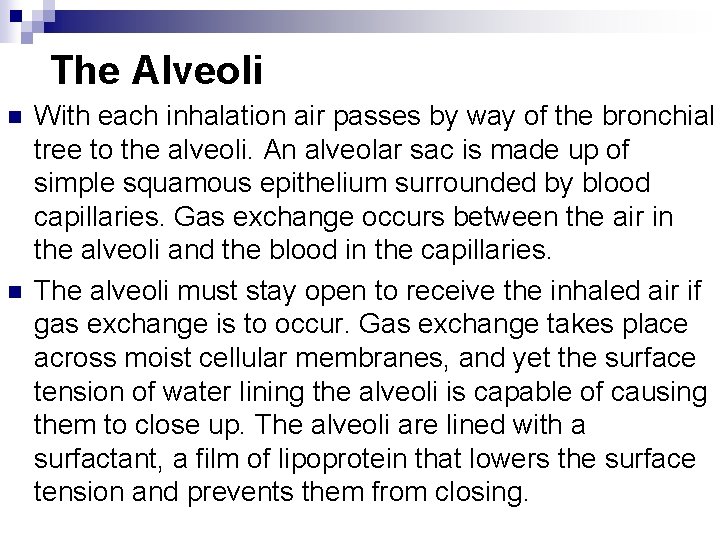

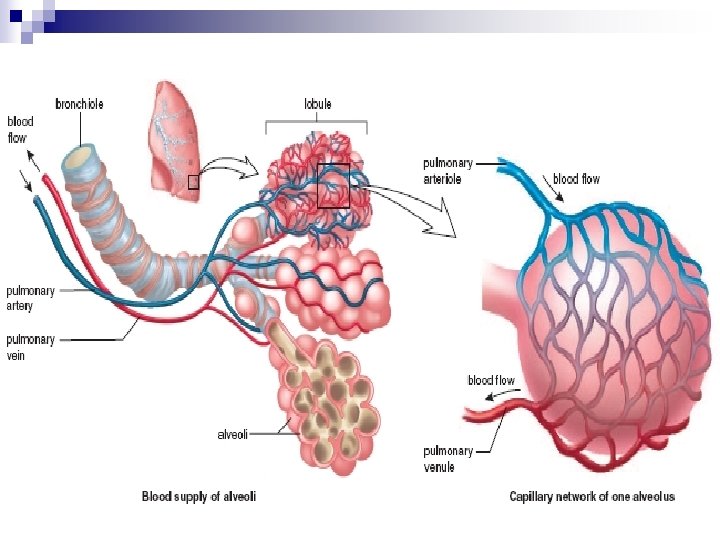

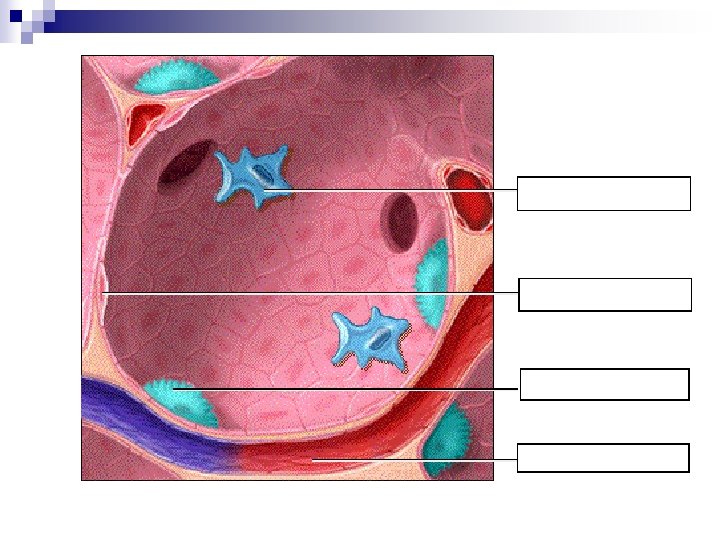

The Alveoli n n With each inhalation air passes by way of the bronchial tree to the alveoli. An alveolar sac is made up of simple squamous epithelium surrounded by blood capillaries. Gas exchange occurs between the air in the alveoli and the blood in the capillaries. The alveoli must stay open to receive the inhaled air if gas exchange is to occur. Gas exchange takes place across moist cellular membranes, and yet the surface tension of water lining the alveoli is capable of causing them to close up. The alveoli are lined with a surfactant, a film of lipoprotein that lowers the surface tension and prevents them from closing.

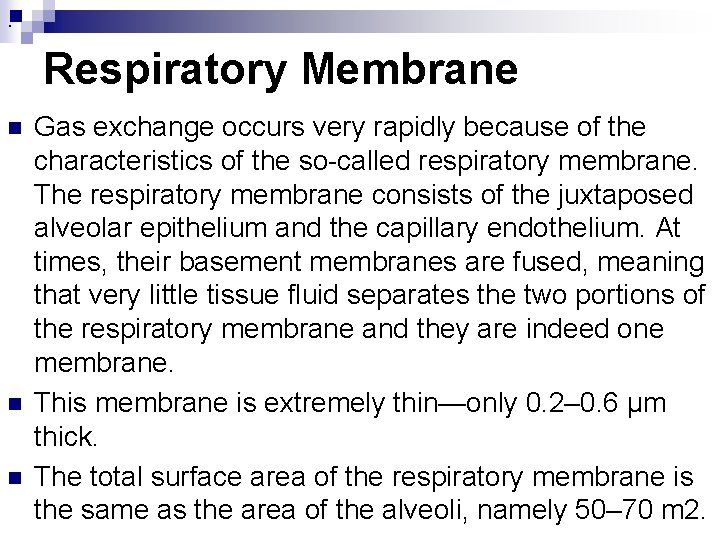

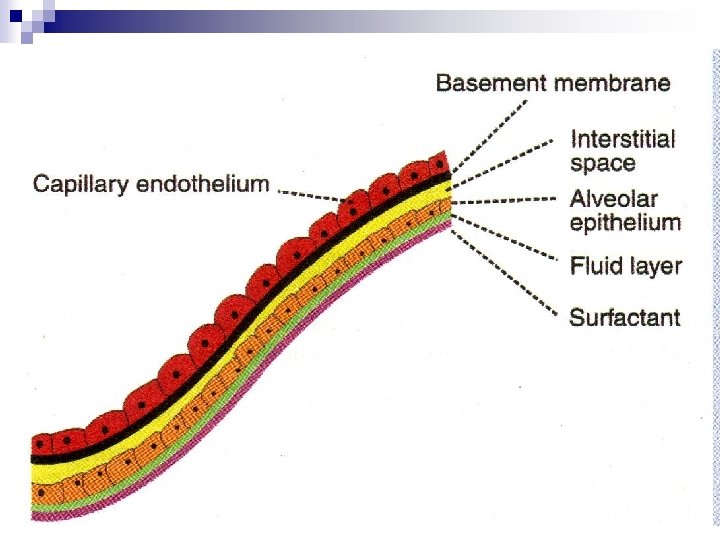

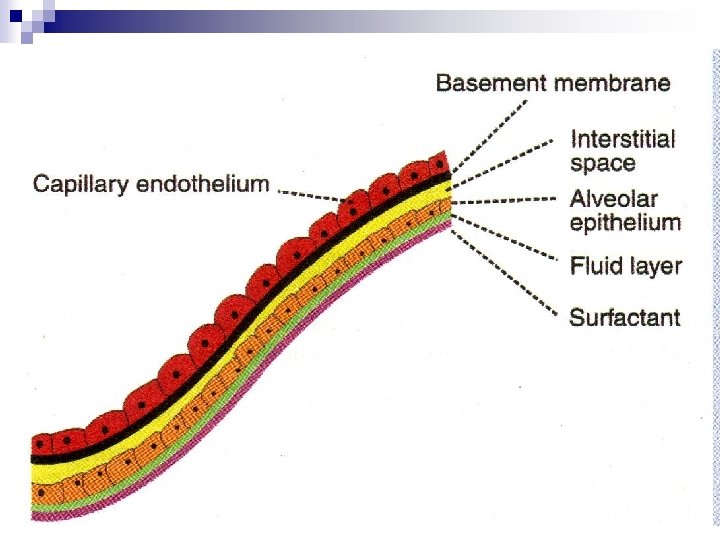

. Respiratory Membrane n n n Gas exchange occurs very rapidly because of the characteristics of the so-called respiratory membrane. The respiratory membrane consists of the juxtaposed alveolar epithelium and the capillary endothelium. At times, their basement membranes are fused, meaning that very little tissue fluid separates the two portions of the respiratory membrane and they are indeed one membrane. This membrane is extremely thin—only 0. 2– 0. 6 μm thick. The total surface area of the respiratory membrane is the same as the area of the alveoli, namely 50– 70 m 2.

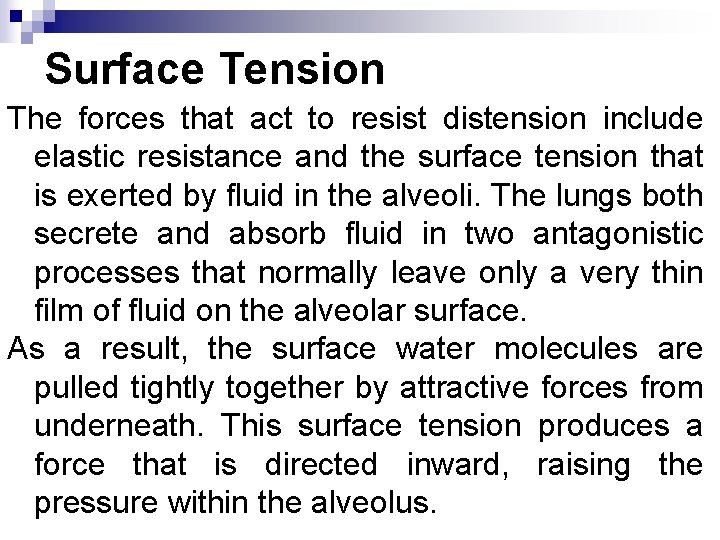

Surface Tension The forces that act to resist distension include elastic resistance and the surface tension that is exerted by fluid in the alveoli. The lungs both secrete and absorb fluid in two antagonistic processes that normally leave only a very thin film of fluid on the alveolar surface. As a result, the surface water molecules are pulled tightly together by attractive forces from underneath. This surface tension produces a force that is directed inward, raising the pressure within the alveolus.

Surfactant Alveolar fluid contains a phospholipid known as lecithin that functions to lower surface tension. This compound is called surfactant—a surface active agent. The surfactant molecules become interspersed between water molecules at the water-air interface of the alveoli, thereby reducing the attractive forces between water molecules that produce the surface tension. Thus, because of surfactant, the surface tension in the alveoli is reduced. Further, the ability of surfactant to lower surface tension improves as the alveoli get smaller during expiration. Surfactant thus prevents the alveoli from collapsing during expiration. Even after a forceful expiration, the alveoli remain open and a residual volume of air remains in the lungs.

Quiet expiration is a passive process . After becoming stretched by contractions of the diaphragm and thoracic muscles, the thorax and lungs recoil as a result of their elastic tension when the respiratory muscles relax. The decrease in lung volume raises the pressure within the alveoli above the atmospheric pressure and pushes the air out. During forced expiration, the internal intercostal muscles contract and depress the rib cage. The abdominal muscles also aid expiration because, when they contract, they force abdominal organs up against the diaphragm.

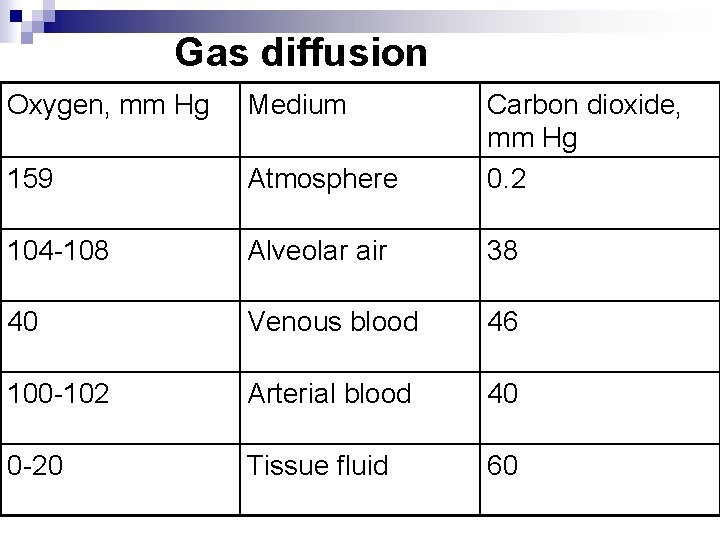

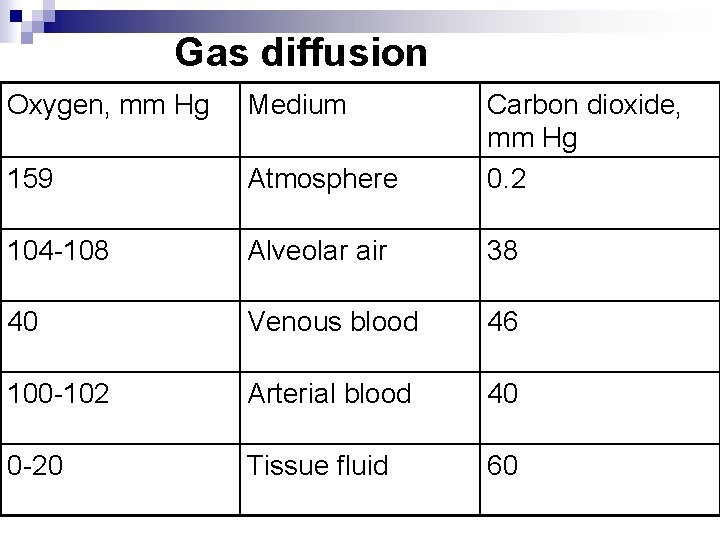

Gas diffusion Oxygen, mm Hg Medium 159 Atmosphere Carbon dioxide, mm Hg 0. 2 104 -108 Alveolar air 38 40 Venous blood 46 100 -102 Arterial blood 40 0 -20 Tissue fluid 60

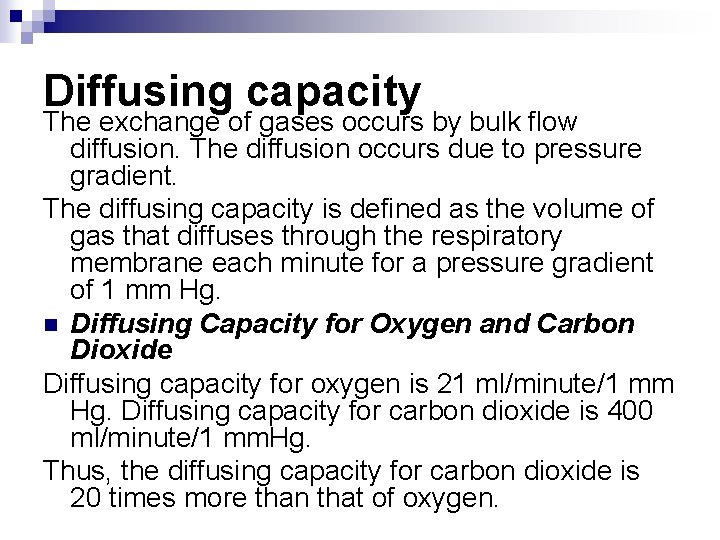

Diffusing capacity The exchange of gases occurs by bulk flow diffusion. The diffusion occurs due to pressure gradient. The diffusing capacity is defined as the volume of gas that diffuses through the respiratory membrane each minute for a pressure gradient of 1 mm Hg. n Diffusing Capacity for Oxygen and Carbon Dioxide Diffusing capacity for oxygen is 21 ml/minute/1 mm Hg. Diffusing capacity for carbon dioxide is 400 ml/minute/1 mm. Hg. Thus, the diffusing capacity for carbon dioxide is 20 times more than that of oxygen.

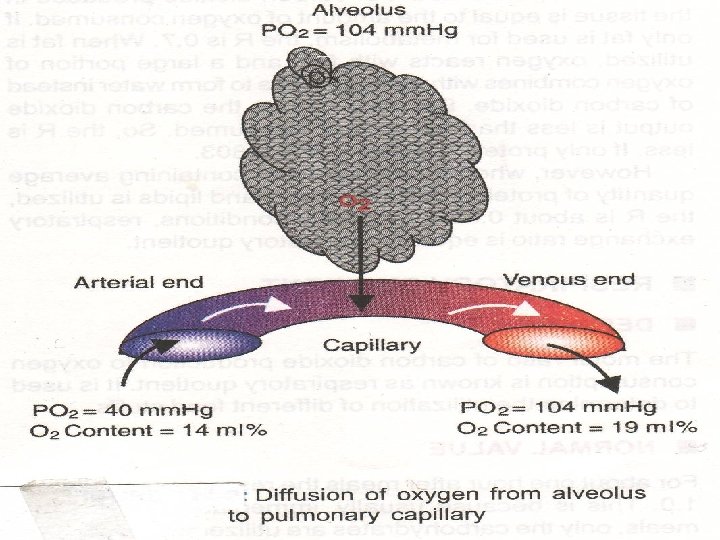

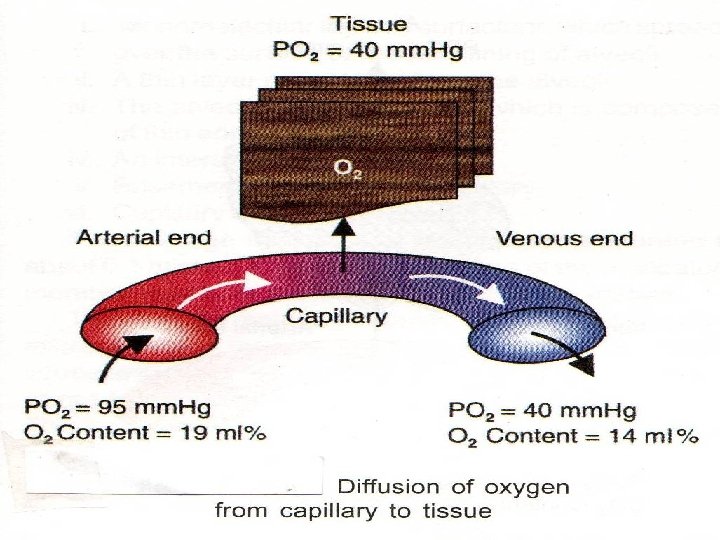

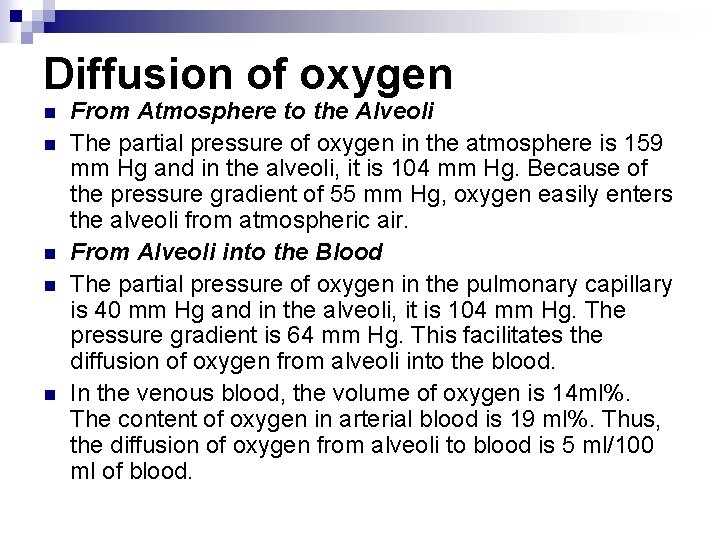

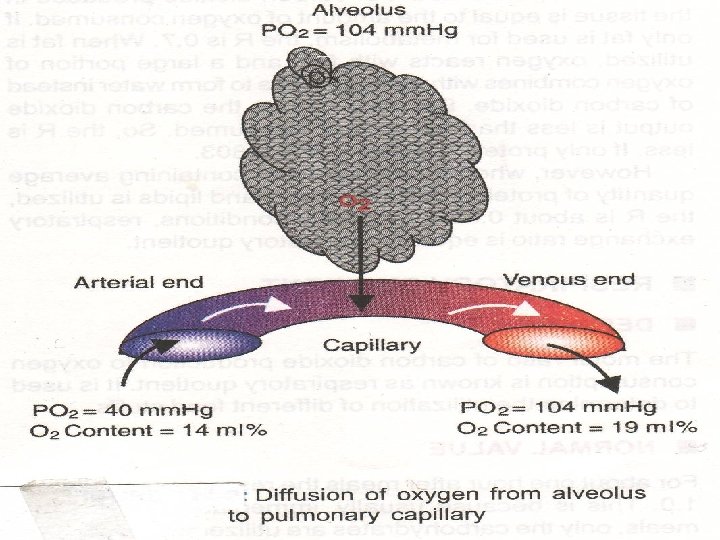

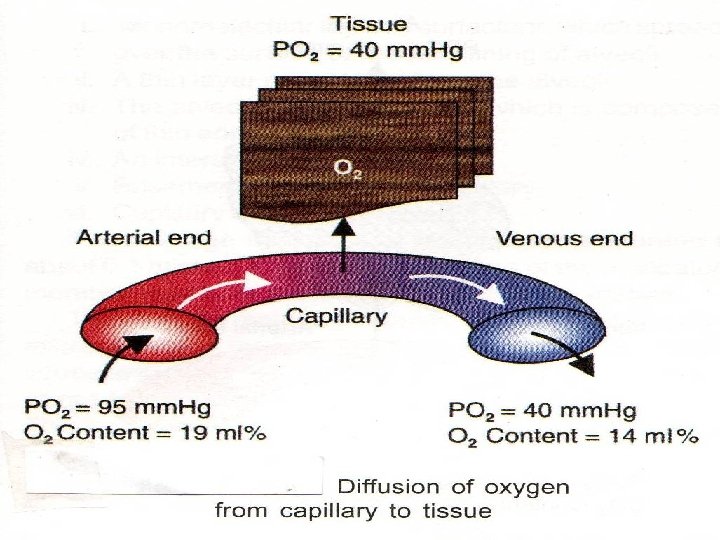

Diffusion of oxygen n n From Atmosphere to the Alveoli The partial pressure of oxygen in the atmosphere is 159 mm Hg and in the alveoli, it is 104 mm Hg. Because of the pressure gradient of 55 mm Hg, oxygen easily enters the alveoli from atmospheric air. From Alveoli into the Blood The partial pressure of oxygen in the pulmonary capillary is 40 mm Hg and in the alveoli, it is 104 mm Hg. The pressure gradient is 64 mm Hg. This facilitates the diffusion of oxygen from alveoli into the blood. In the venous blood, the volume of oxygen is 14 ml%. The content of oxygen in arterial blood is 19 ml%. Thus, the diffusion of oxygen from alveoli to blood is 5 ml/100 ml of blood.

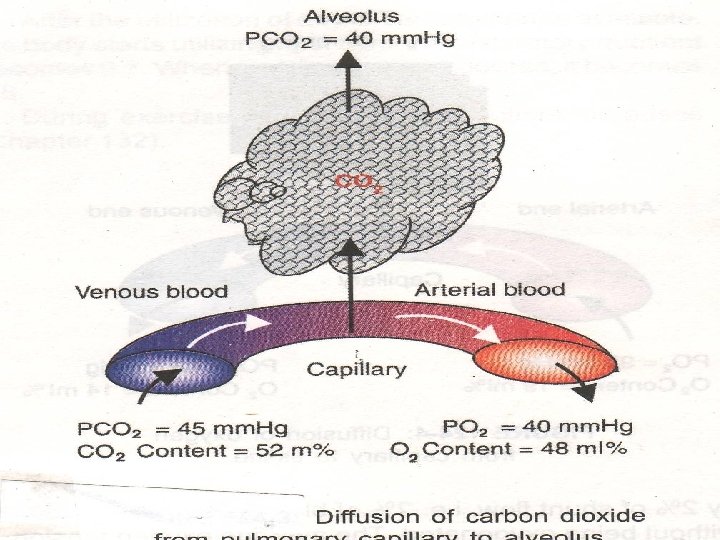

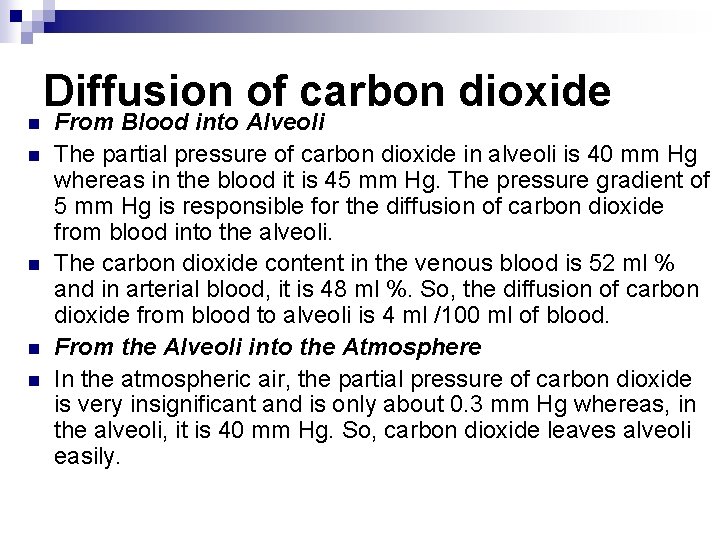

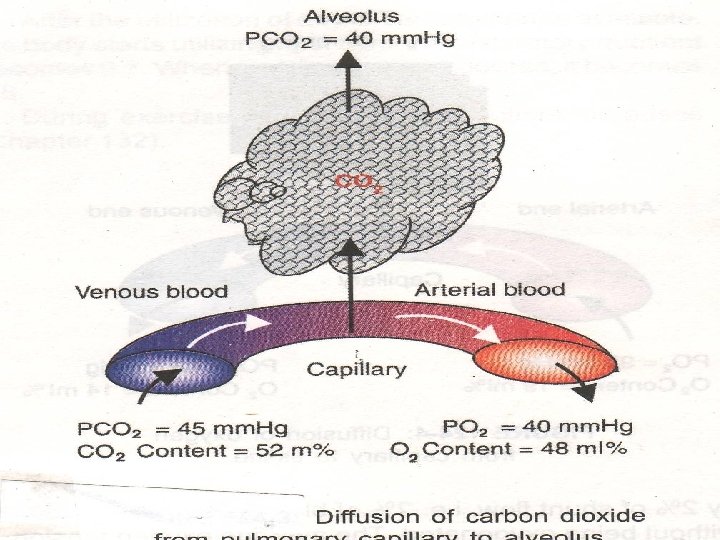

n n n Diffusion of carbon dioxide From Blood into Alveoli The partial pressure of carbon dioxide in alveoli is 40 mm Hg whereas in the blood it is 45 mm Hg. The pressure gradient of 5 mm Hg is responsible for the diffusion of carbon dioxide from blood into the alveoli. The carbon dioxide content in the venous blood is 52 ml % and in arterial blood, it is 48 ml %. So, the diffusion of carbon dioxide from blood to alveoli is 4 ml /100 ml of blood. From the Alveoli into the Atmosphere In the atmospheric air, the partial pressure of carbon dioxide is very insignificant and is only about 0. 3 mm Hg whereas, in the alveoli, it is 40 mm Hg. So, carbon dioxide leaves alveoli easily.

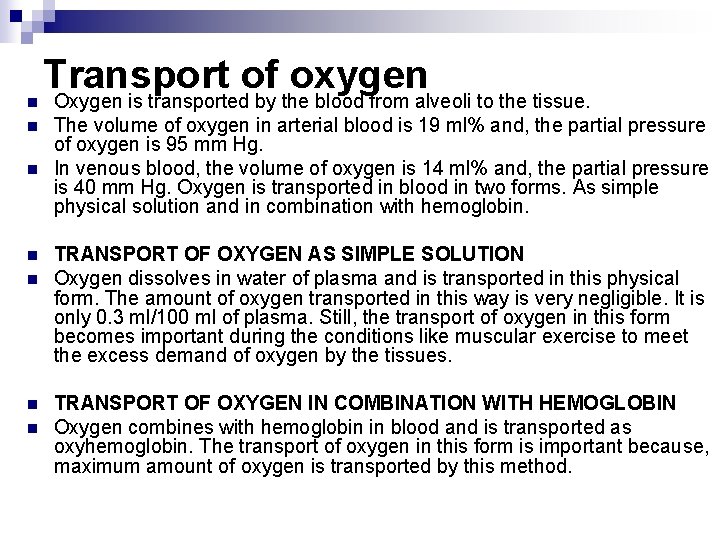

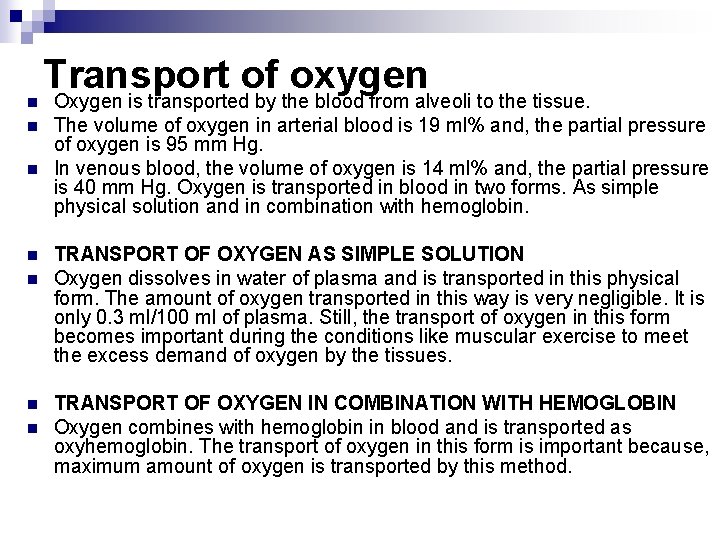

n n n n Transport of oxygen Oxygen is transported by the blood from alveoli to the tissue. The volume of oxygen in arterial blood is 19 ml% and, the partial pressure of oxygen is 95 mm Hg. In venous blood, the volume of oxygen is 14 ml% and, the partial pressure is 40 mm Hg. Oxygen is transported in blood in two forms. As simple physical solution and in combination with hemoglobin. TRANSPORT OF OXYGEN AS SIMPLE SOLUTION Oxygen dissolves in water of plasma and is transported in this physical form. The amount of oxygen transported in this way is very negligible. It is only 0. 3 ml/100 ml of plasma. Still, the transport of oxygen in this form becomes important during the conditions like muscular exercise to meet the excess demand of oxygen by the tissues. TRANSPORT OF OXYGEN IN COMBINATION WITH HEMOGLOBIN Oxygen combines with hemoglobin in blood and is transported as oxyhemoglobin. The transport of oxygen in this form is important because, maximum amount of oxygen is transported by this method.

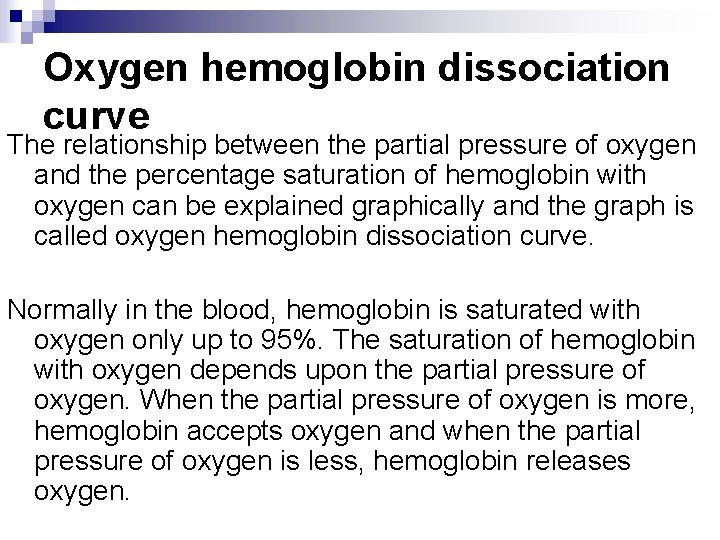

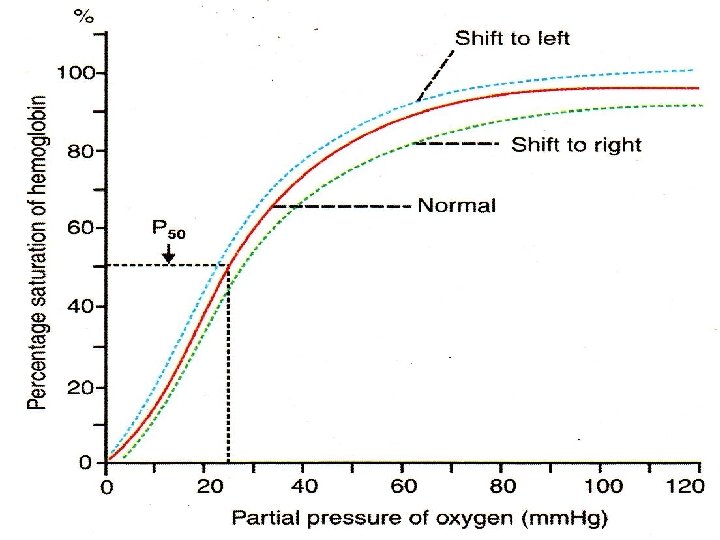

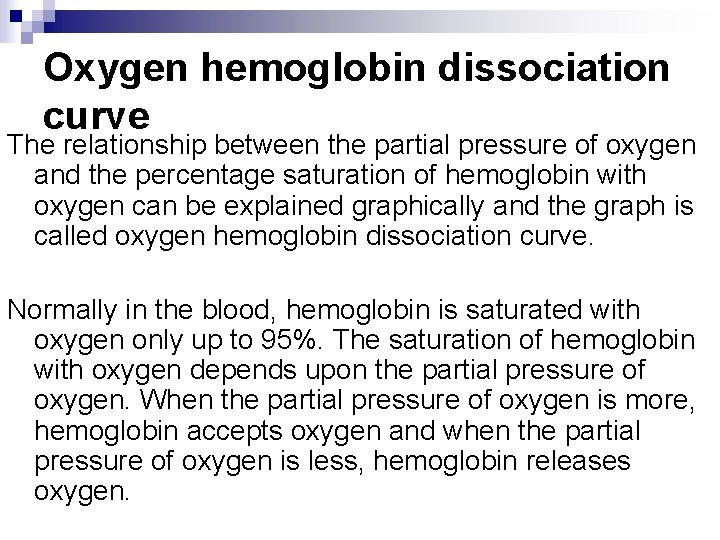

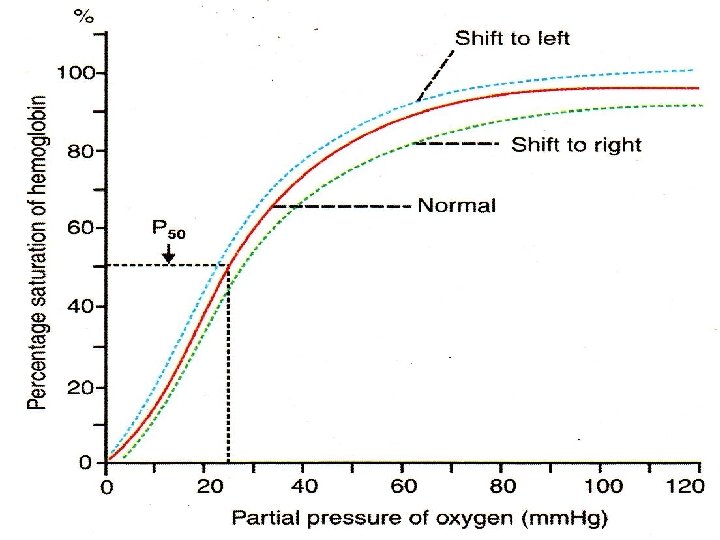

Oxygen hemoglobin dissociation curve The relationship between the partial pressure of oxygen and the percentage saturation of hemoglobin with oxygen can be explained graphically and the graph is called oxygen hemoglobin dissociation curve. Normally in the blood, hemoglobin is saturated with oxygen only up to 95%. The saturation of hemoglobin with oxygen depends upon the partial pressure of oxygen. When the partial pressure of oxygen is more, hemoglobin accepts oxygen and when the partial pressure of oxygen is less, hemoglobin releases oxygen.

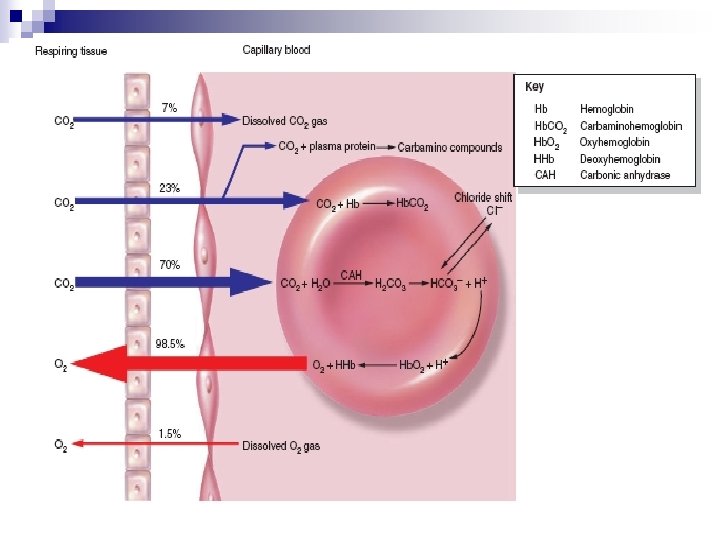

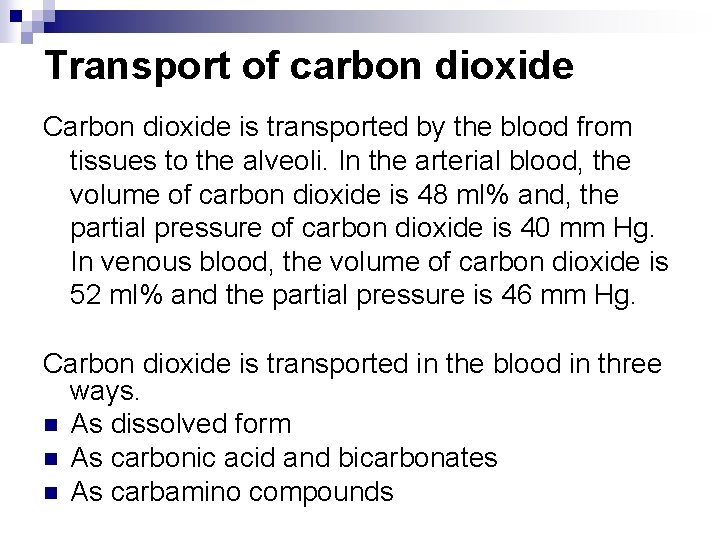

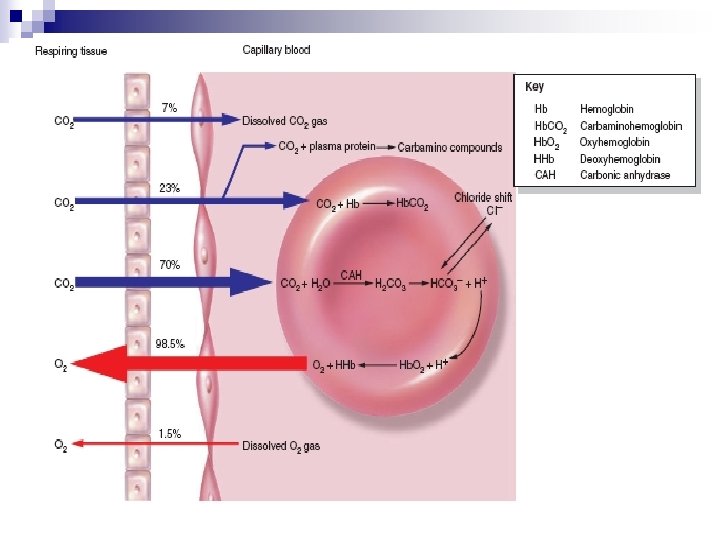

Transport of carbon dioxide Carbon dioxide is transported by the blood from tissues to the alveoli. In the arterial blood, the volume of carbon dioxide is 48 ml% and, the partial pressure of carbon dioxide is 40 mm Hg. In venous blood, the volume of carbon dioxide is 52 ml% and the partial pressure is 46 mm Hg. Carbon dioxide is transported in the blood in three ways. n As dissolved form n As carbonic acid and bicarbonates n As carbamino compounds

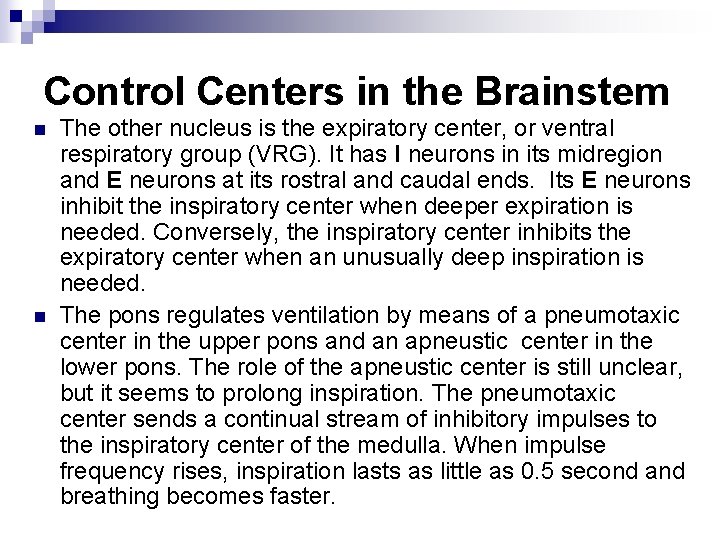

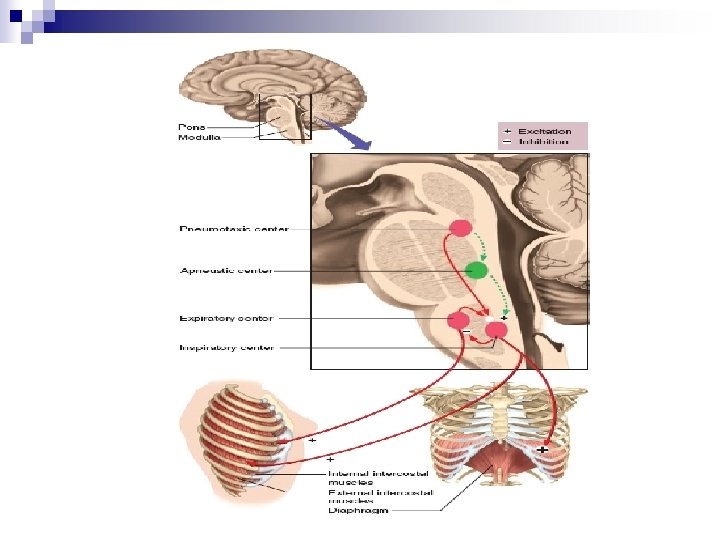

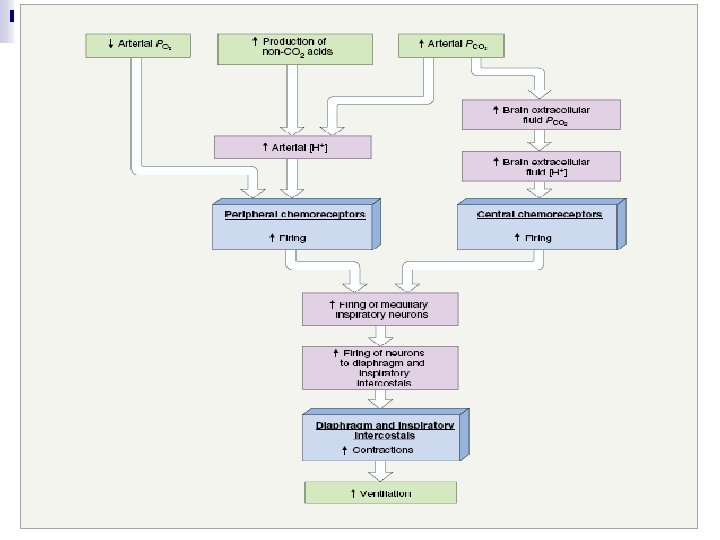

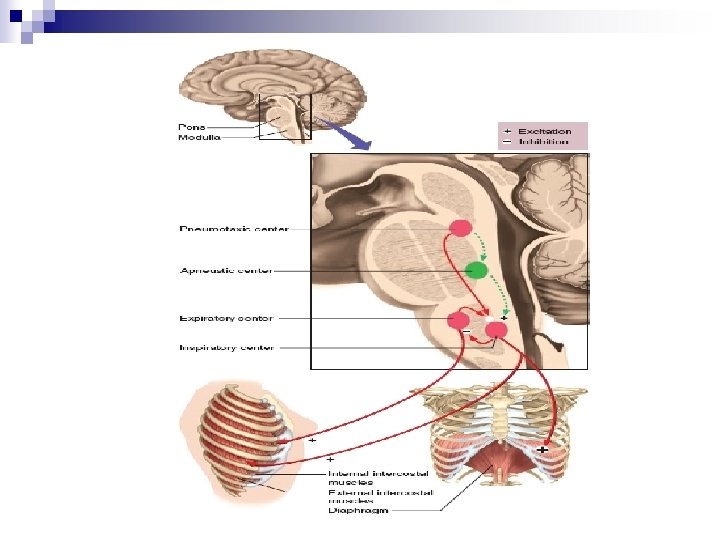

Control Centers in the Brainstem n n The medulla oblongata contains inspiratory (I) neurons, which fire during inspiration, and expiratory (E) neurons, which fire during forced expiration. Fibers from these neurons travel down the spinal cord and synapse with lower motor neurons in the cervical to thoracic regions. From here, nerve fibers travel in the phrenic nerves to the diaphragm and intercostal nerves to the intercostal muscles. The medulla has two respiratory nuclei. One of them, called the inspiratory center, or dorsal respiratory group (DRG), is composed primarily of I neurons, which stimulate the muscles of inspiration.

Control Centers in the Brainstem n n The other nucleus is the expiratory center, or ventral respiratory group (VRG). It has I neurons in its midregion and E neurons at its rostral and caudal ends. Its E neurons inhibit the inspiratory center when deeper expiration is needed. Conversely, the inspiratory center inhibits the expiratory center when an unusually deep inspiration is needed. The pons regulates ventilation by means of a pneumotaxic center in the upper pons and an apneustic center in the lower pons. The role of the apneustic center is still unclear, but it seems to prolong inspiration. The pneumotaxic center sends a continual stream of inhibitory impulses to the inspiratory center of the medulla. When impulse frequency rises, inspiration lasts as little as 0. 5 second and breathing becomes faster.

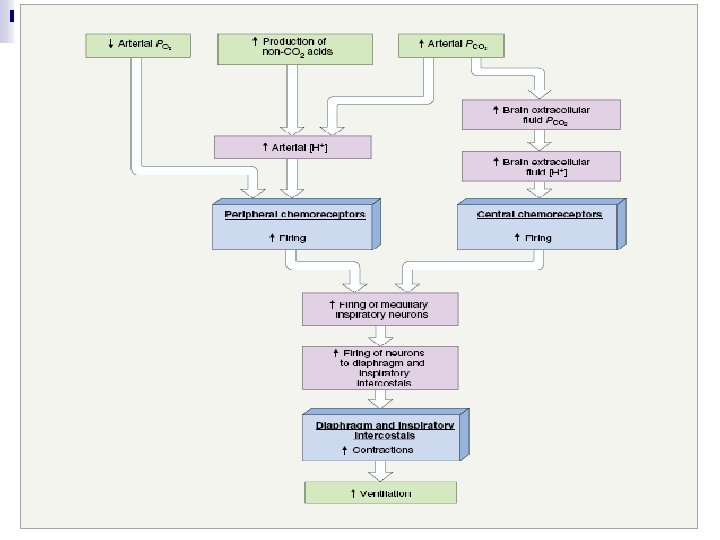

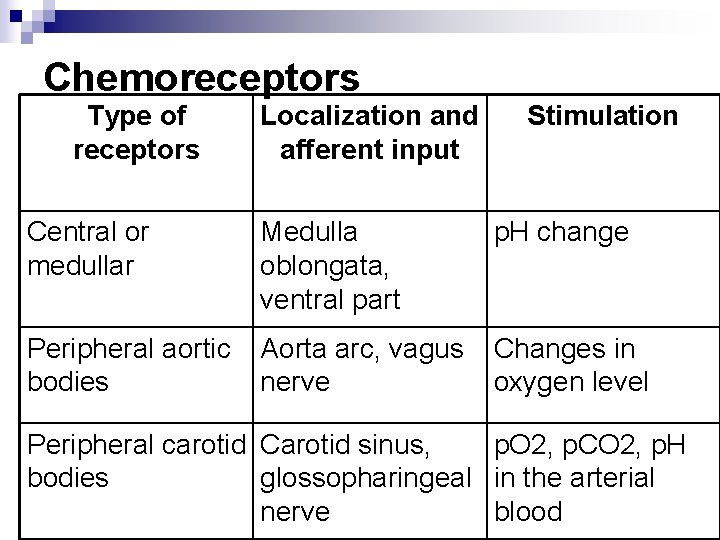

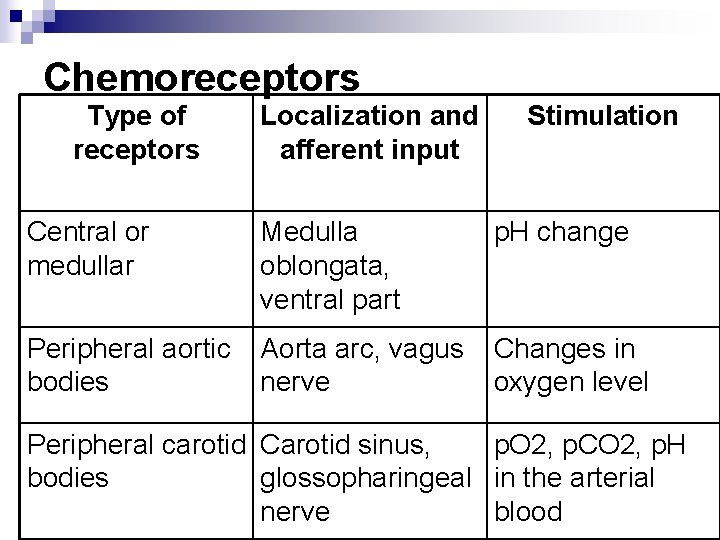

Chemoreceptors Type of receptors Localization and afferent input Stimulation Central or medullar Medulla oblongata, ventral part p. H change Peripheral aortic bodies Aorta arc, vagus nerve Changes in oxygen level Peripheral carotid Carotid sinus, p. O 2, p. CO 2, p. H bodies glossopharingeal in the arterial nerve blood