The Pulmonologists Guide to the Pulmonary Consequences of

- Slides: 57

The Pulmonologist’s Guide to the Pulmonary Consequences of Smoking and the Benefits of Cessation

Overview Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) – Emphysema – Chronic bronchitis Asthma Lung cancer GOLD Initiative 2006. http: //www. goldcopd. com. Accessed July 24, 2007; Celli et al. Eur Respir J. 2004; 23: 932 -946.

Smoking and COPD

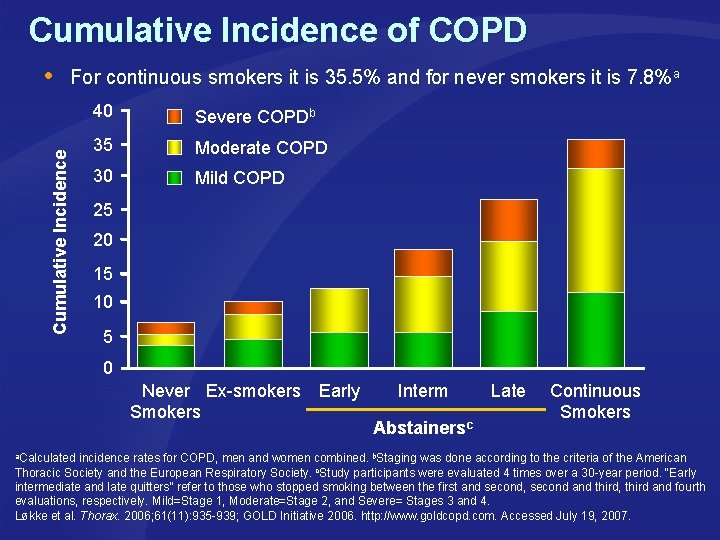

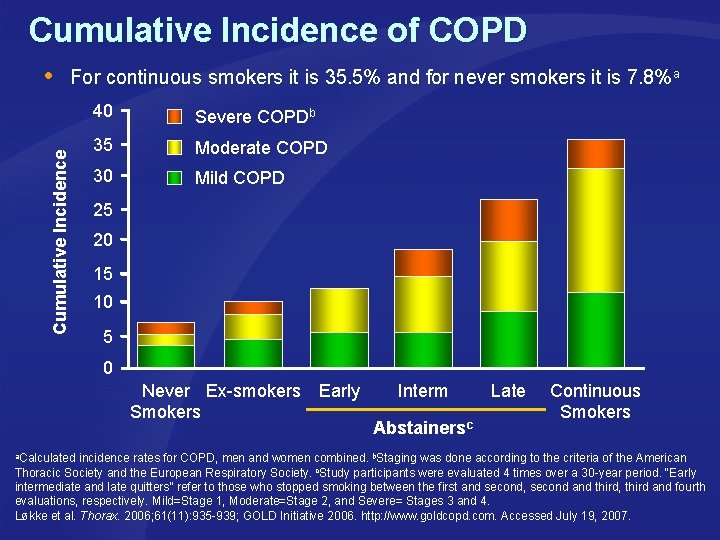

Cumulative Incidence of COPD Cumulative Incidence For continuous smokers it is 35. 5% and for never smokers it is 7. 8%a 40 Severe COPDb 35 Moderate COPD 30 Mild COPD 25 20 15 10 5 0 Never Ex-smokers Smokers Early Interm Abstainersc Late Continuous Smokers a. Calculated incidence rates for COPD, men and women combined. b. Staging was done according to the criteria of the American Thoracic Society and the European Respiratory Society. c. Study participants were evaluated 4 times over a 30 -year period. “Early intermediate and late quitters” refer to those who stopped smoking between the first and second, second and third, third and fourth evaluations, respectively. Mild=Stage 1, Moderate=Stage 2, and Severe= Stages 3 and 4. Løkke et al. Thorax. 2006; 61(11): 935 -939; GOLD Initiative 2006. http: //www. goldcopd. com. Accessed July 19, 2007.

COPD Mortality Worldwide, 80 million people have moderate-to-severe COPD Half of all COPD patients die within a decade of diagnosis COPD predicted to become the fourth leading cause of death worldwide by 2030 In 2005, 3 million people died of COPD Anto. Eur Respir J. 2001; 17: 982 -994; http: //www. who. int/respiratory/copd/en/. Accessed April 27, 2007; World Health Organization. http: //www. who. int/en. Accessed July 19, 2007; http: //www. istockphoto. com/file_closeup/who/people_specific_attributes/body_parts/848586_puff_2_smoke_version. php? id=848586. Accessed October 22, 2007.

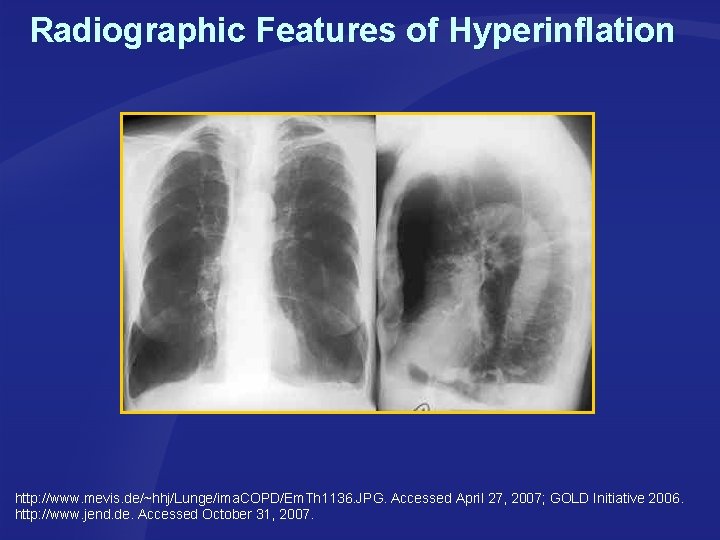

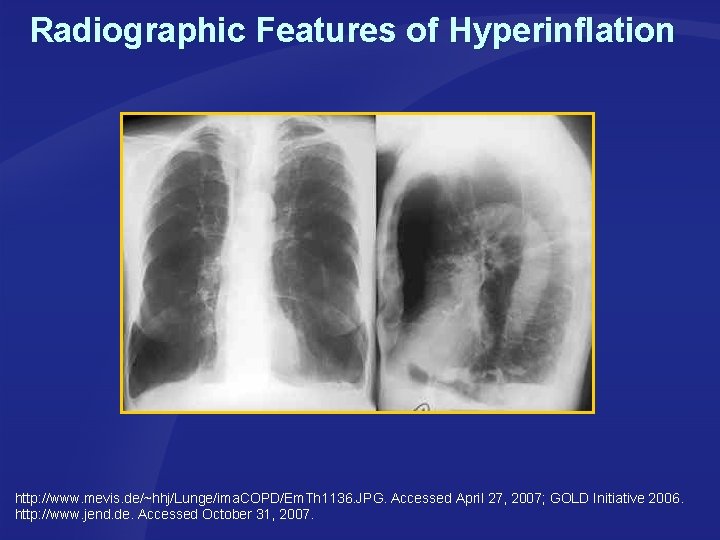

Radiographic Features of Hyperinflation http: //www. mevis. de/~hhj/Lunge/ima. COPD/Em. Th 1136. JPG. Accessed April 27, 2007; GOLD Initiative 2006. http: //www. jend. de. Accessed October 31, 2007.

COPD: Pathophysiology Airflow Limitation Irreversible airflow limitation measured during forced expiration is caused by either – An increase in the resistance of the small conducting airways – An increase in lung compliance due to emphysematous lung destruction – Both Airflow limitation is usually progressive and associated with – – Lesions that obstruct the small conducting airways Emphysematous destruction of the lung’s elastic recoil force – Abnormal inflammatory response to noxious particles or gases, primarily caused by cigarette smoking Hogg. Lancet. 2004; 364(9435): 709 -721; Anderson. Neurology. 2005; 64: 1488 -1489; Celli et al. Eur Respir J. 2004; 23: 932 -946.

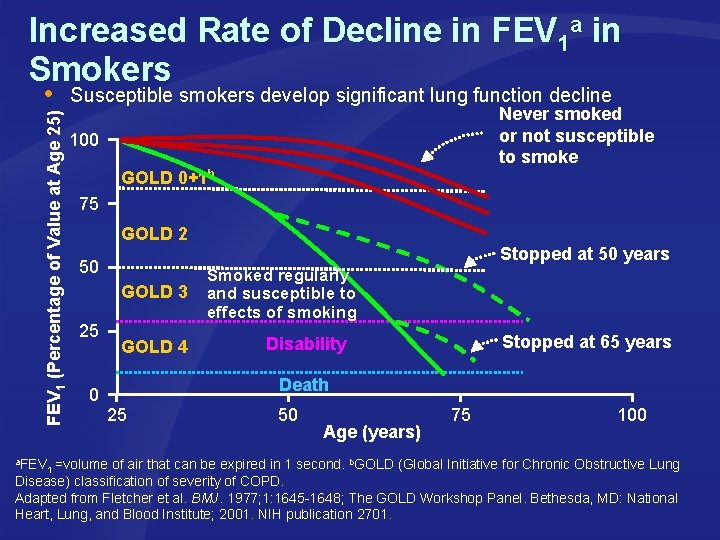

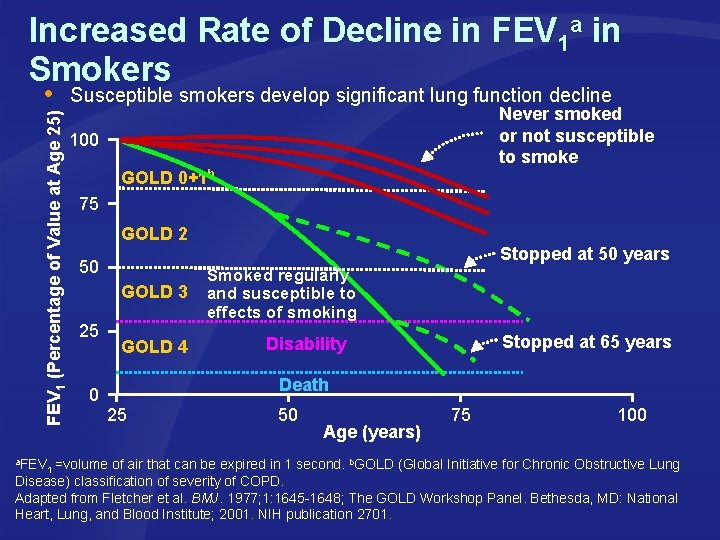

Increased Rate of Decline in FEV 1 a in Smokers FEV 1 (Percentage of Value at Age 25) a. FEV Susceptible smokers develop significant lung function decline Never smoked or not susceptible to smoke 100 GOLD 0+1 b 75 GOLD 2 Stopped at 50 years 50 GOLD 3 25 GOLD 4 Smoked regularly and susceptible to effects of smoking Stopped at 65 years Disability Death 0 25 50 Age (years) 1 =volume of air that can be expired in 1 second. 75 100 b. GOLD (Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease) classification of severity of COPD. Adapted from Fletcher et al. BMJ. 1977; 1: 1645 -1648; The GOLD Workshop Panel. Bethesda, MD: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; 2001. NIH publication 2701.

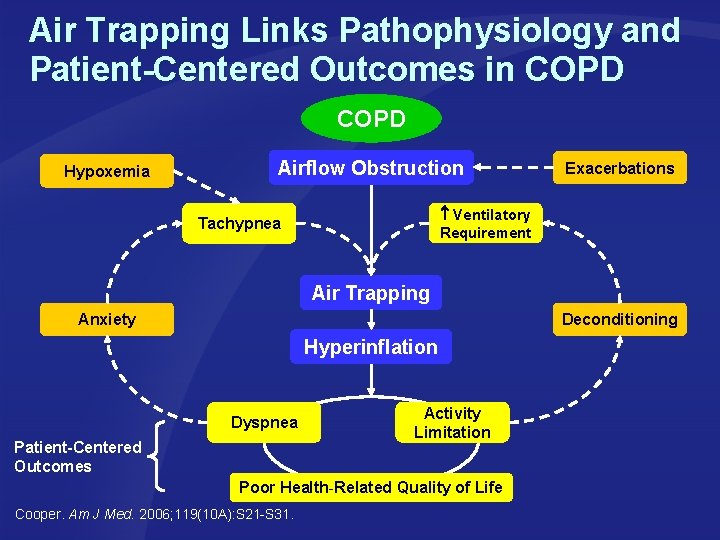

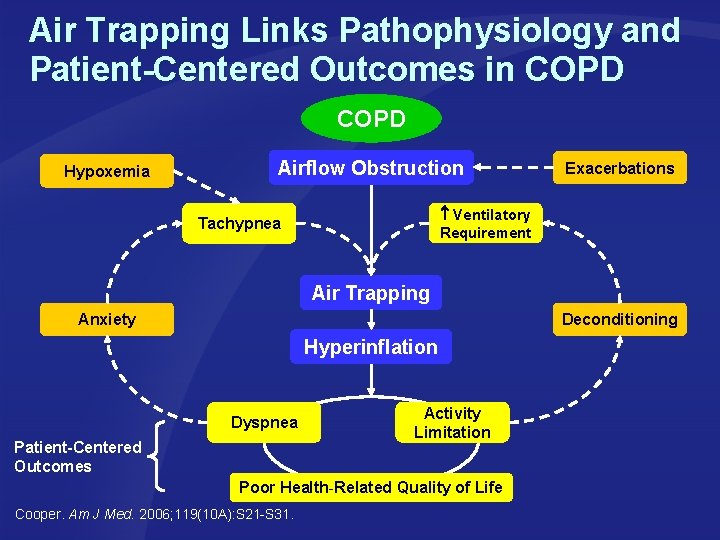

Air Trapping Links Pathophysiology and Patient-Centered Outcomes in COPD Hypoxemia Airflow Obstruction Exacerbations Ventilatory Requirement Tachypnea Air Trapping Anxiety Deconditioning Hyperinflation Dyspnea Patient-Centered Outcomes Activity Limitation Poor Health-Related Quality of Life Cooper. Am J Med. 2006; 119(10 A): S 21 -S 31.

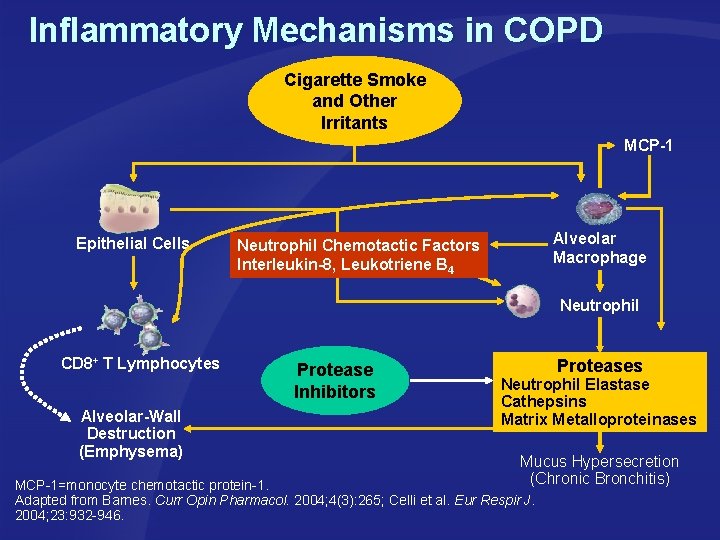

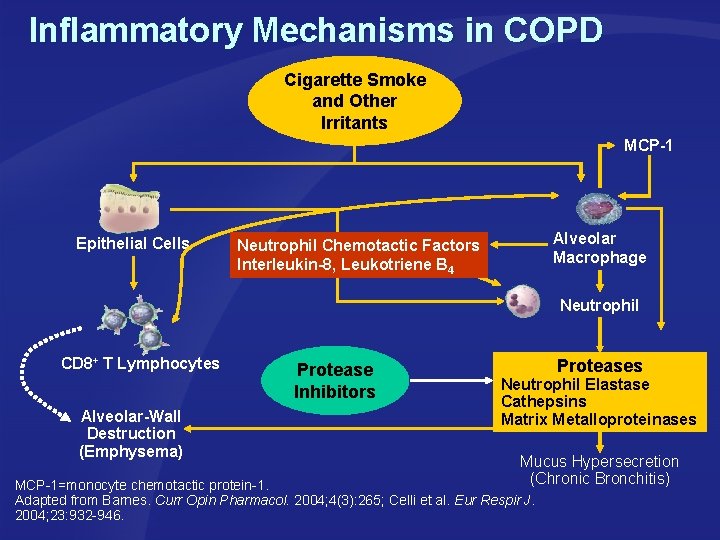

Inflammatory Mechanisms in COPD Cigarette Smoke and Other Irritants MCP-1 Epithelial Cells Alveolar Macrophage Neutrophil Chemotactic Factors Interleukin-8, Leukotriene B 4 Neutrophil CD 8+ T Lymphocytes Alveolar-Wall Destruction (Emphysema) Protease Inhibitors Proteases Neutrophil Elastase Cathepsins Matrix Metalloproteinases Mucus Hypersecretion (Chronic Bronchitis) MCP-1=monocyte chemotactic protein-1. Adapted from Barnes. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2004; 4(3): 265; Celli et al. Eur Respir J. 2004; 23: 932 -946.

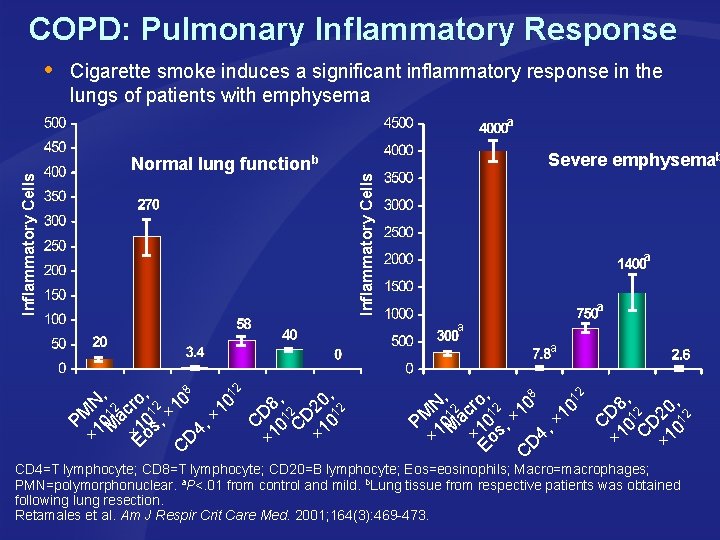

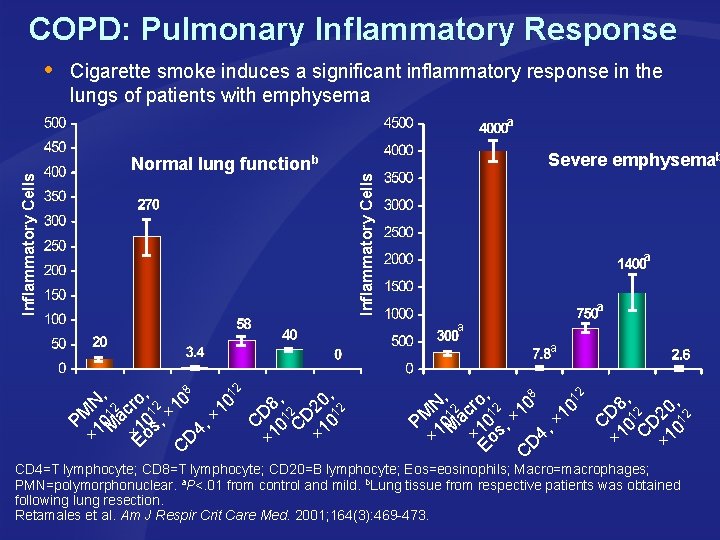

COPD: Pulmonary Inflammatory Response Cigarette smoke induces a significant inflammatory response in the lungs of patients with emphysema Normal lung functionb Severe emphysemab Inflammatory Cells a a a 8 12 , , 0 o 0 0 N 12 cr 12 1 8 2 12 1 × M D 12 D × a , 0 P 10 M 1 s C 0 C 10 4, 1 ×Eo × × D × C 8 , , 12 , , N 12 cro 12 10 8 0 0 2 1 D 2 C 01 D 2 01 PM 10 Ma 10 s, × 1 C 1 4 × o × × × D E C CD 4=T lymphocyte; CD 8=T lymphocyte; CD 20=B lymphocyte; Eos=eosinophils; Macro=macrophages; PMN=polymorphonuclear. a. P<. 01 from control and mild. b. Lung tissue from respective patients was obtained following lung resection. Retamales et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001; 164(3): 469 -473.

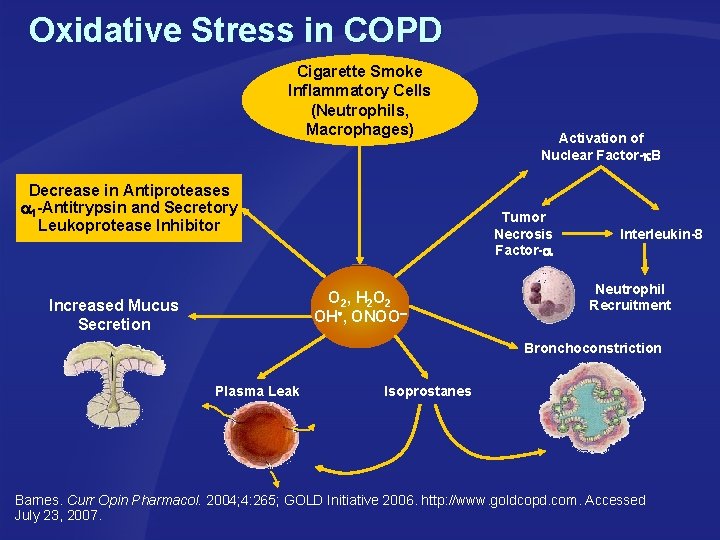

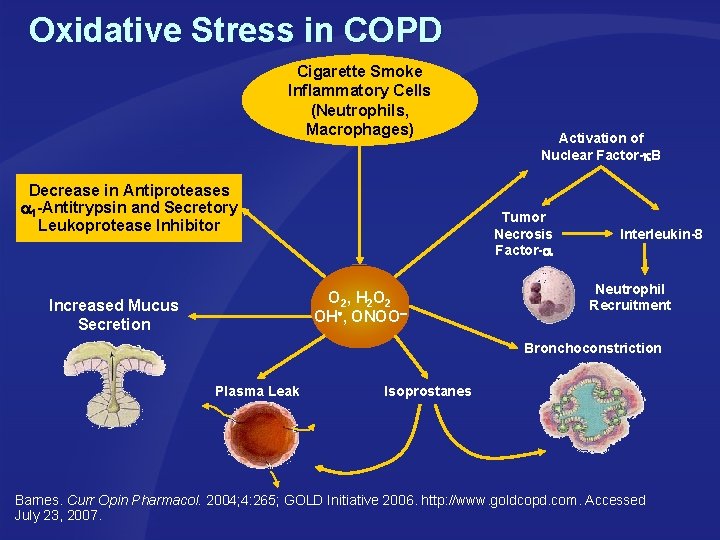

Oxidative Stress in COPD Cigarette Smoke Inflammatory Cells (Neutrophils, Macrophages) Decrease in Antiproteases 1 -Antitrypsin and Secretory Leukoprotease Inhibitor Tumor Necrosis Factor- O 2, H 2 O 2 OH , ONOO Increased Mucus Secretion Activation of Nuclear Factor- B Interleukin-8 Neutrophil Recruitment Bronchoconstriction Plasma Leak lsoprostanes Barnes. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2004; 4: 265; GOLD Initiative 2006. http: //www. goldcopd. com. Accessed July 23, 2007.

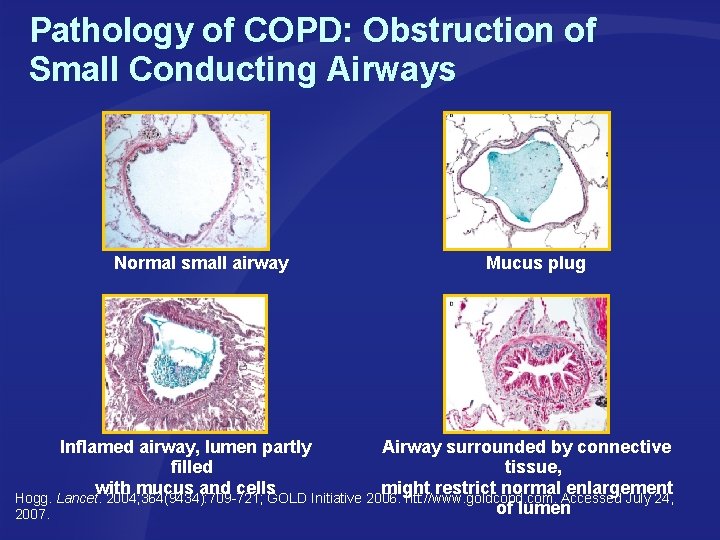

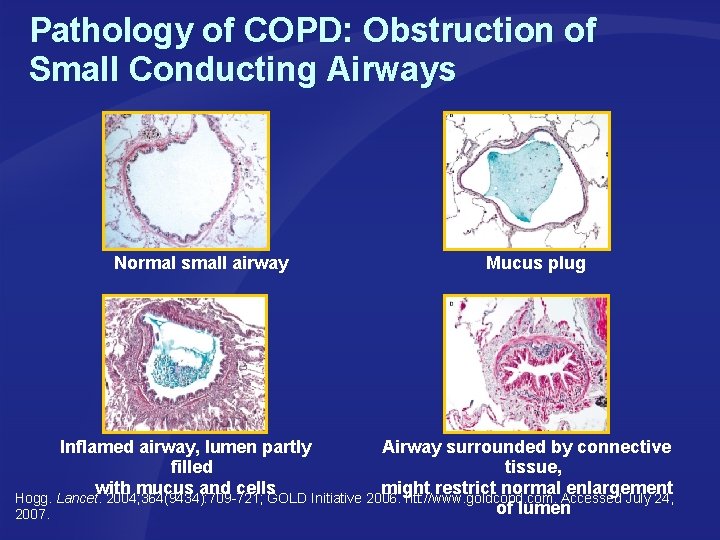

Pathology of COPD: Obstruction of Small Conducting Airways Normal small airway Mucus plug Inflamed airway, lumen partly Airway surrounded by connective filled tissue, with mucus and cells might restrict normal enlargement Hogg. Lancet. 2004; 364(9434): 709 -721; GOLD Initiative 2006. htt: //www. goldcopd. com. Accessed July 24, of lumen 2007.

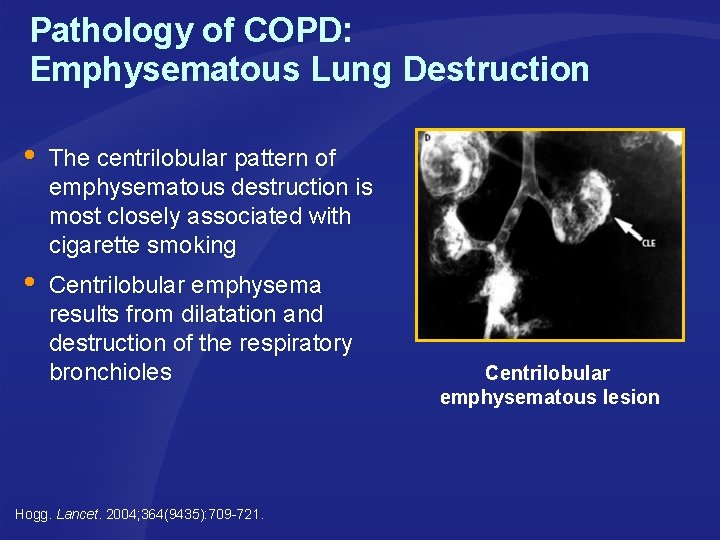

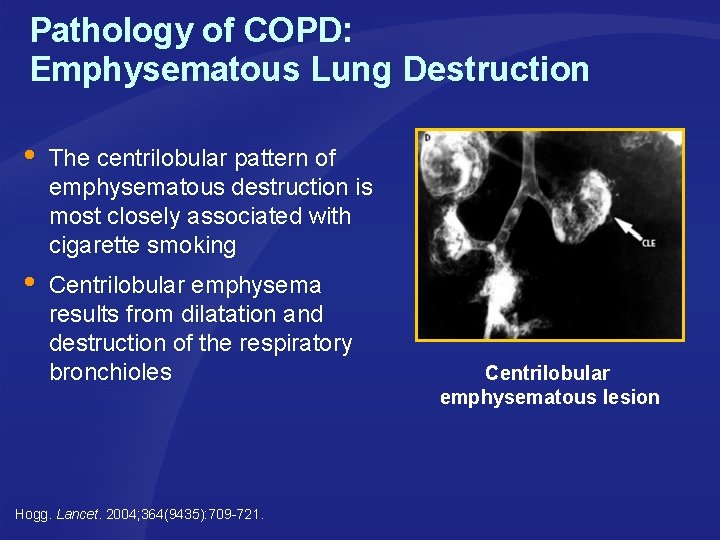

Pathology of COPD: Emphysematous Lung Destruction The centrilobular pattern of emphysematous destruction is most closely associated with cigarette smoking Centrilobular emphysema results from dilatation and destruction of the respiratory bronchioles Hogg. Lancet. 2004; 364(9435): 709 -721. Centrilobular emphysematous lesion

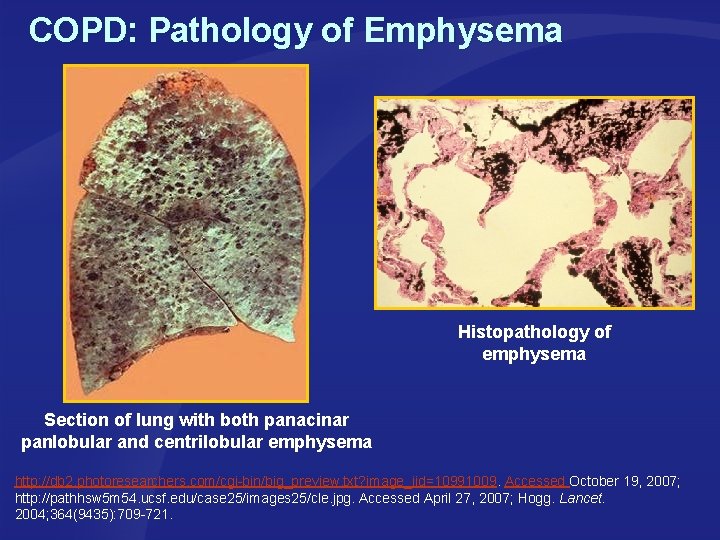

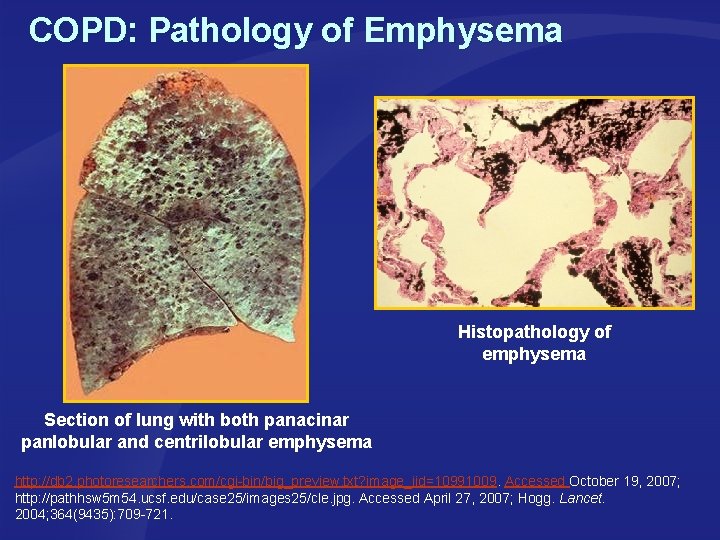

COPD: Pathology of Emphysema Histopathology of emphysema Section of lung with both panacinar panlobular and centrilobular emphysema http: //db 2. photoresearchers. com/cgi-bin/big_preview. txt? image_iid=10991009. Accessed October 19, 2007; http: //pathhsw 5 m 54. ucsf. edu/case 25/images 25/cle. jpg. Accessed April 27, 2007; Hogg. Lancet. 2004; 364(9435): 709 -721.

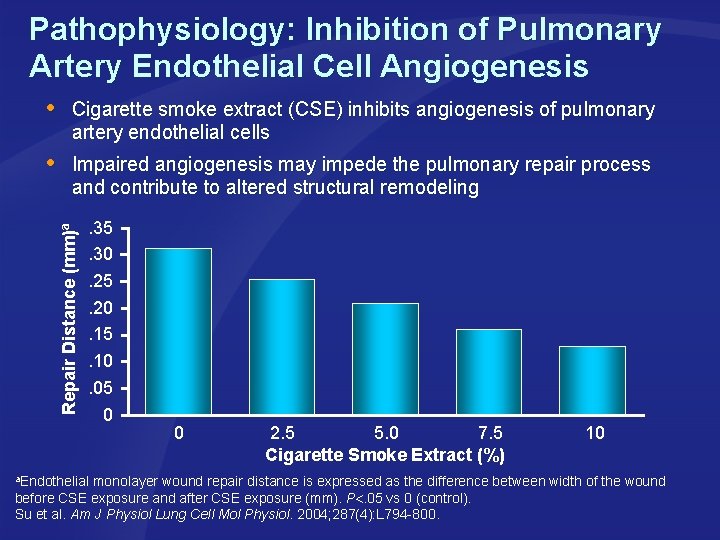

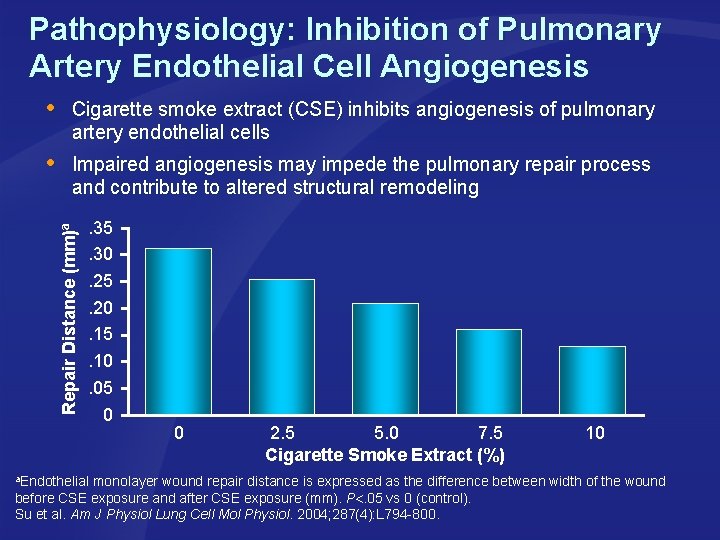

Pathophysiology: Inhibition of Pulmonary Artery Endothelial Cell Angiogenesis Cigarette smoke extract (CSE) inhibits angiogenesis of pulmonary artery endothelial cells Impaired angiogenesis may impede the pulmonary repair process and contribute to altered structural remodeling Repair Distance (mm)a . 35. 30. 25. 20. 15. 10. 05 0 0 2. 5 5. 0 7. 5 Cigarette Smoke Extract (%) 10 a. Endothelial monolayer wound repair distance is expressed as the difference between width of the wound before CSE exposure and after CSE exposure (mm). P. 05 vs 0 (control). Su et al. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004; 287(4): L 794 -800.

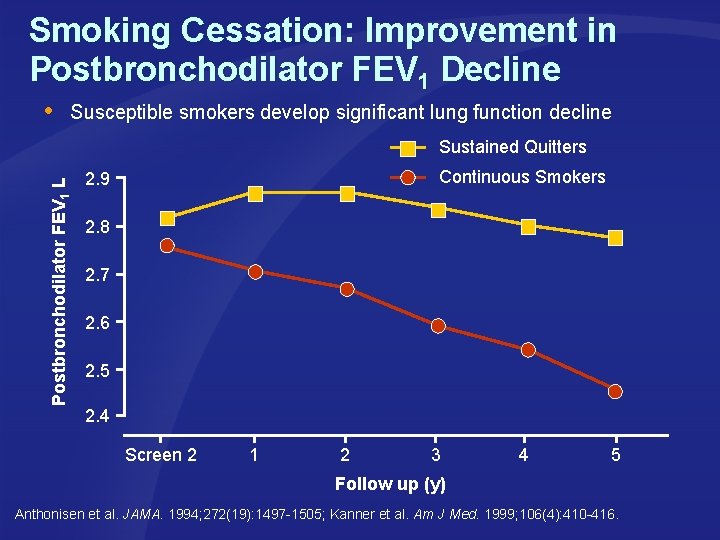

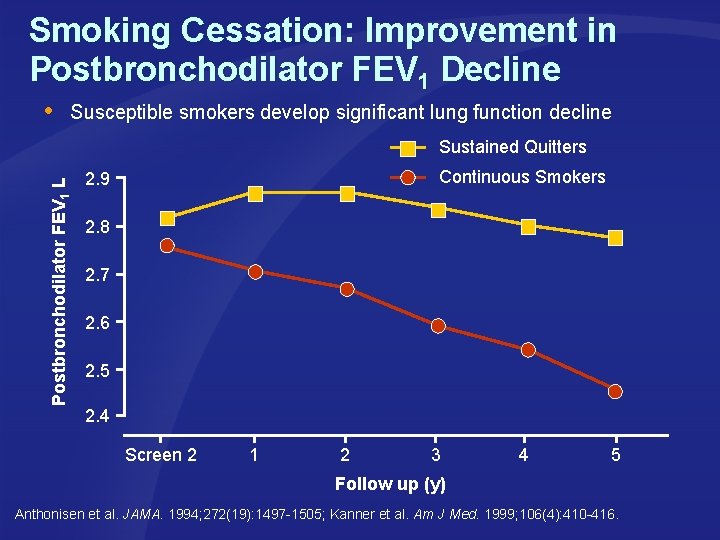

Smoking Cessation: Improvement in Postbronchodilator FEV 1 Decline Susceptible smokers develop significant lung function decline Postbronchodilator FEV 1 L Sustained Quitters Continuous Smokers 2. 9 2. 8 2. 7 2. 6 2. 5 2. 4 Screen 2 1 2 3 4 5 Follow up (y) Anthonisen et al. JAMA. 1994; 272(19): 1497 -1505; Kanner et al. Am J Med. 1999; 106(4): 410 -416.

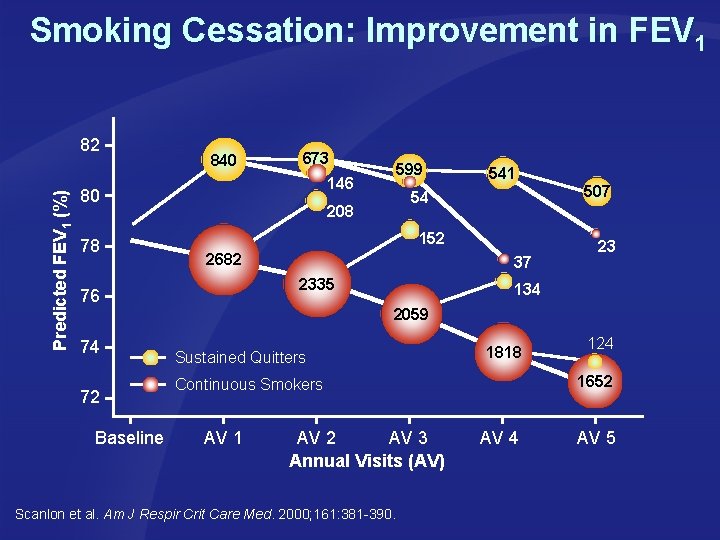

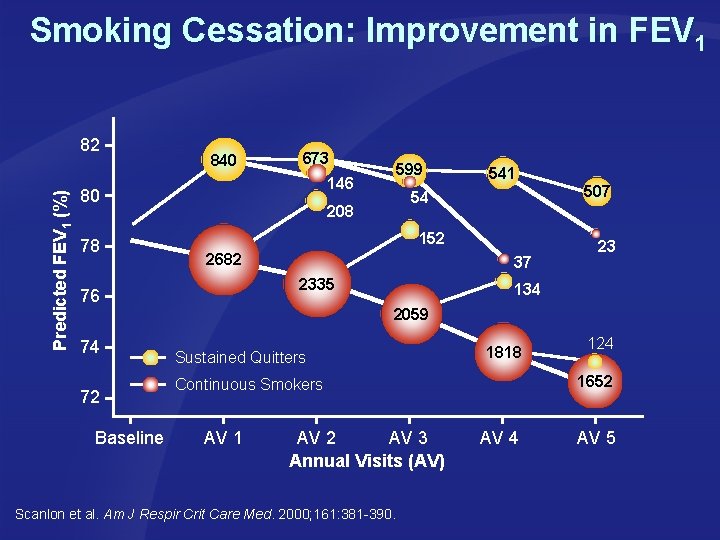

Smoking Cessation: Improvement in FEV 1 Predicted FEV 1 (%) 82 840 673 146 80 78 72 Baseline 541 507 54 208 152 2682 37 2335 76 74 599 23 134 2059 Sustained Quitters 1818 1652 Continuous Smokers AV 1 AV 2 AV 3 Annual Visits (AV) Scanlon et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000; 161: 381 -390. 124 AV 5

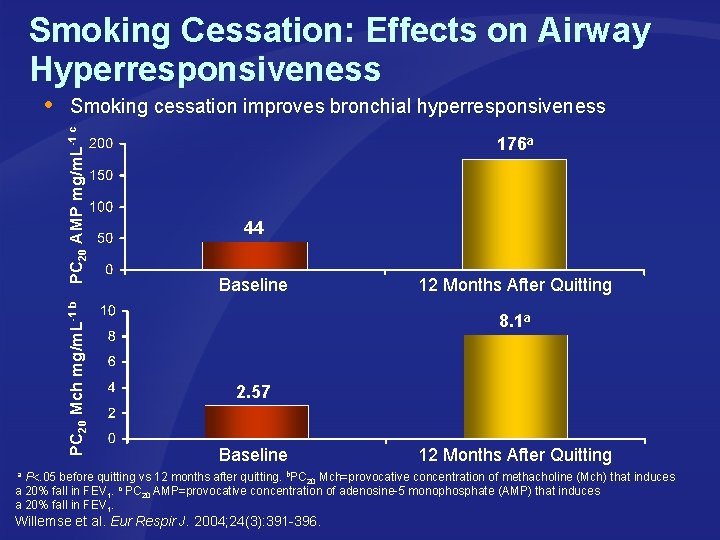

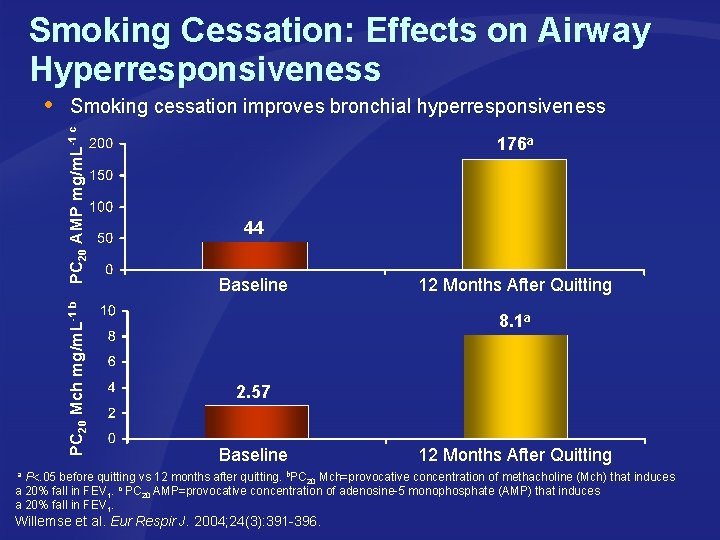

Smoking Cessation: Effects on Airway Hyperresponsiveness Smoking cessation improves bronchial hyperresponsiveness PC 20 Mch mg/m. L-1 b PC 20 AMP mg/m. L-1 c 176 a 44 Baseline 12 Months After Quitting 8. 1 a 2. 57 Baseline 12 Months After Quitting a P. 05 before quitting vs 12 months after quitting. b. PC Mch=provocative concentration of methacholine (Mch) that induces 20 a 20% fall in FEV 1. c PC 20 AMP=provocative concentration of adenosine-5‘ monophosphate (AMP) that induces a 20% fall in FEV 1. Willemse et al. Eur Respir J. 2004; 24(3): 391 -396.

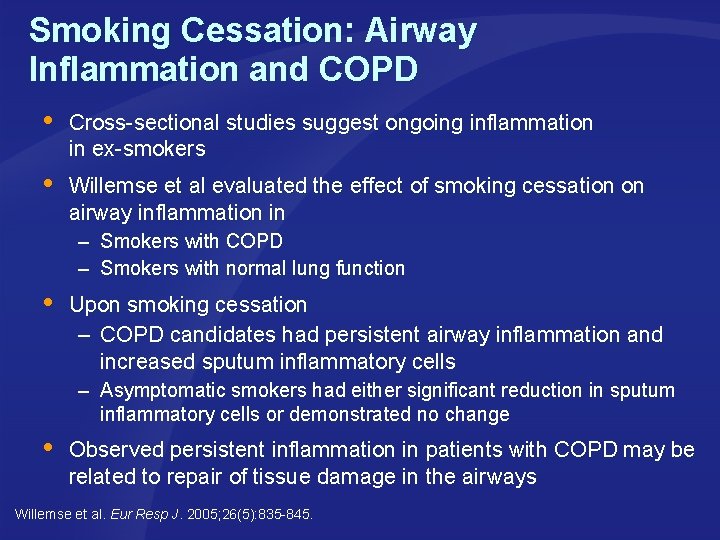

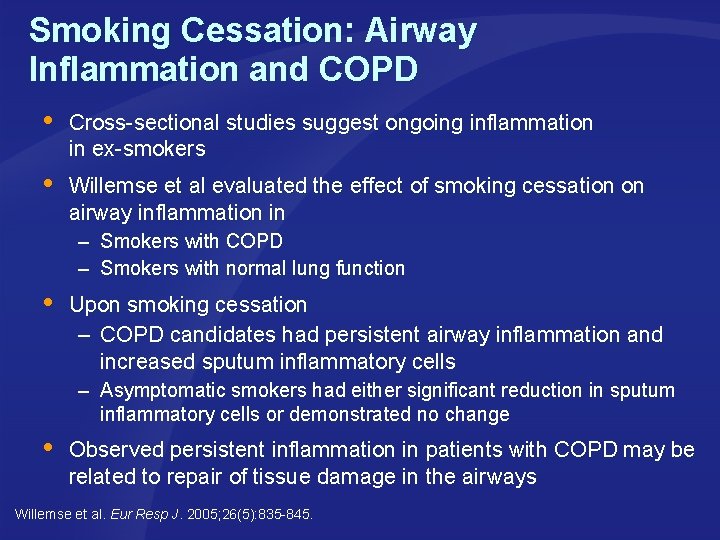

Smoking Cessation: Airway Inflammation and COPD Cross-sectional studies suggest ongoing inflammation in ex-smokers Willemse et al evaluated the effect of smoking cessation on airway inflammation in – – Smokers with COPD Smokers with normal lung function Upon smoking cessation – COPD candidates had persistent airway inflammation and increased sputum inflammatory cells – Asymptomatic smokers had either significant reduction in sputum inflammatory cells or demonstrated no change Observed persistent inflammation in patients with COPD may be related to repair of tissue damage in the airways Willemse et al. Eur Resp J. 2005; 26(5): 835 -845.

Notes Continuation of Previous Slide

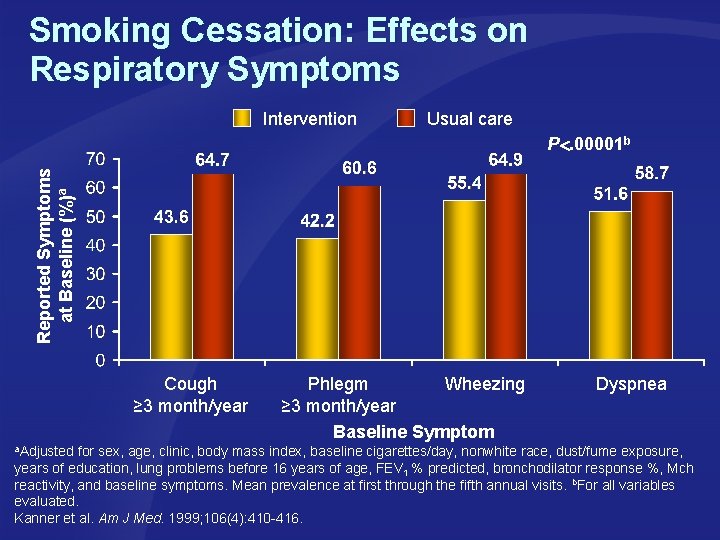

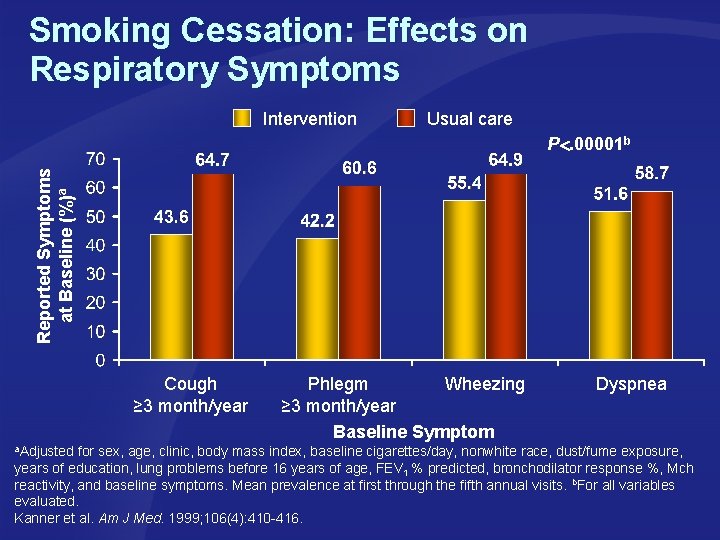

Smoking Cessation: Effects on Respiratory Symptoms Intervention Usual care Reported Symptoms at Baseline (%)a P. 00001 b Cough ≥ 3 month/year Phlegm Wheezing ≥ 3 month/year Baseline Symptom Dyspnea a. Adjusted for sex, age, clinic, body mass index, baseline cigarettes/day, nonwhite race, dust/fume exposure, years of education, lung problems before 16 years of age, FEV 1 % predicted, bronchodilator response %, Mch reactivity, and baseline symptoms. Mean prevalence at first through the fifth annual visits. b. For all variables evaluated. Kanner et al. Am J Med. 1999; 106(4): 410 -416.

Chronic Bronchitis Chronic inflammatory process associated with – Increased production of mucus – Defective mucociliary clearance – Disruption of the epithelial barrier Smoking increases neutrophil recruitment to the lung Approximately half of smokers who have chronic bronchitis develop COPD Productive cough for a minimum of 3 months a year Approximately 2 out of 5 continuous smokers ultimately develop chronic bronchitis Pelkonen et al. Chest. 2006; 130(4): 1129 -1137; Hill et al. Eur Respir J. 2000; 15(5): 886 -890; Hogg. Lancet. 2004; 364(9435): 709 -721; Celli et al. Eur Respir J. 2004; 23: 932 -946.

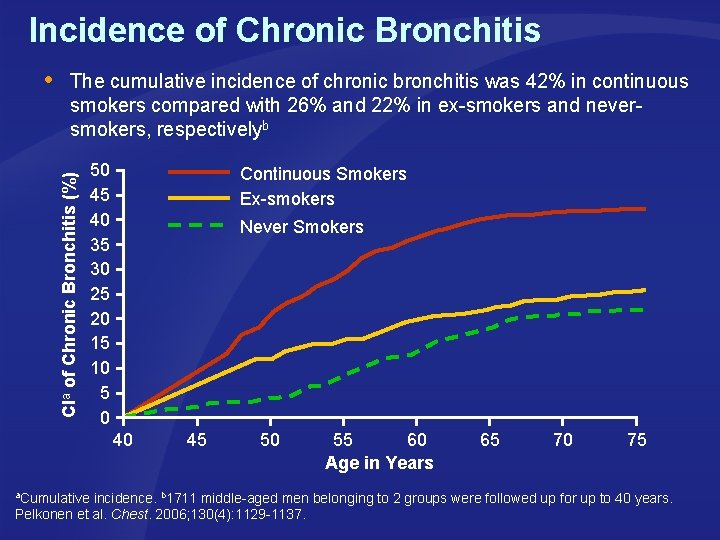

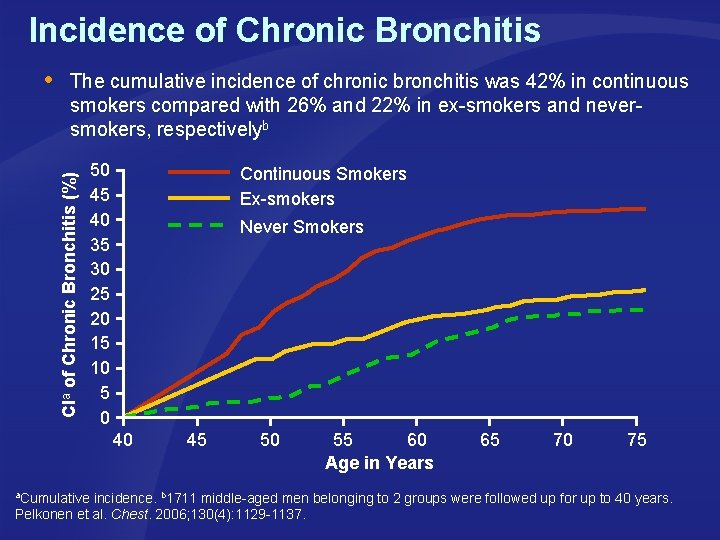

Incidence of Chronic Bronchitis The cumulative incidence of chronic bronchitis was 42% in continuous smokers compared with 26% and 22% in ex-smokers and never- smokers, respectivelyb CIa of Chronic Bronchitis (%) 50 45 40 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 Continuous Smokers Ex-smokers Never Smokers 40 45 50 55 60 Age in Years 65 70 75 a. Cumulative incidence. b 1711 middle-aged men belonging to 2 groups were followed up for up to 40 years. Pelkonen et al. Chest. 2006; 130(4): 1129 -1137.

Chronic Bronchitis: Effects of Smoking Cessation Smoking cessation in chronic bronchitis results in – Reduction in IL-8 concentration in airways – Decreased neutrophil recruitment – Slowed progression of lung disease Hill et al. Eur Respir J. 2000; 15(5): 886 -890.

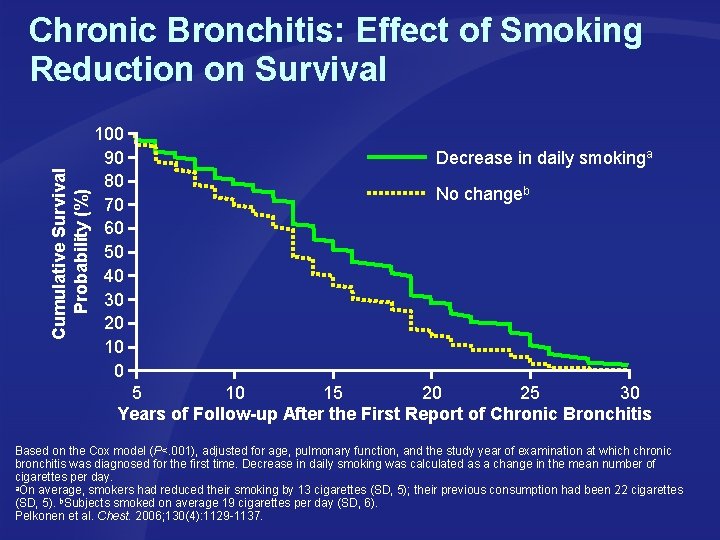

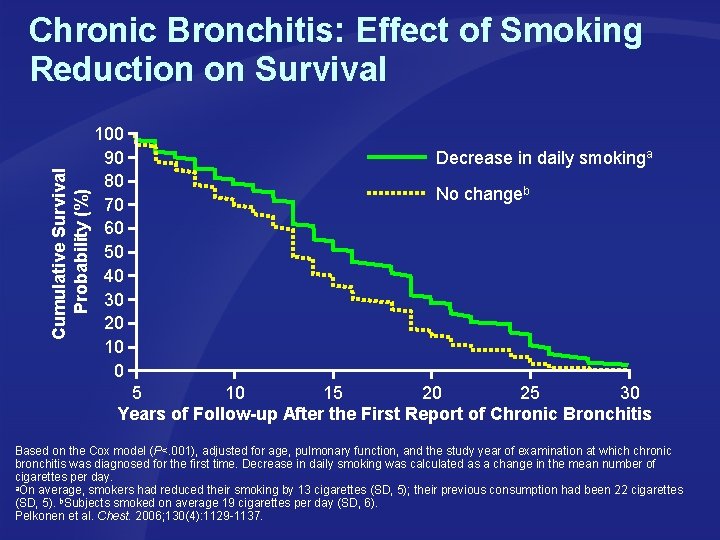

Cumulative Survival Probability (%) Chronic Bronchitis: Effect of Smoking Reduction on Survival 100 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Decrease in daily smokinga No changeb 5 10 15 20 25 30 Years of Follow-up After the First Report of Chronic Bronchitis Based on the Cox model (P<. 001), adjusted for age, pulmonary function, and the study year of examination at which chronic bronchitis was diagnosed for the first time. Decrease in daily smoking was calculated as a change in the mean number of cigarettes per day. a. On average, smokers had reduced their smoking by 13 cigarettes (SD, 5); their previous consumption had been 22 cigarettes (SD, 5). b. Subjects smoked on average 19 cigarettes per day (SD, 6). Pelkonen et al. Chest. 2006; 130(4): 1129 -1137.

Summary: Smoking and COPD – Increased incidence in smokers – Pathophysiology • Inflammation and oxidative stress result in – Obstructive lesions of the small conducting airways – Dilatation and destruction of respiratory bronchioles • Smoking induces significant lung function decline – Smoking cessation • Associated with improved lung function • Reduces airway hyperresponsiveness – Chronic bronchitis • Increased incidence in smokers • Smoking cessation – Slows progression of lung disease – Reduces mortality

Smoking and Asthma

Asthma and Environmental Tobacco Smoke (ETS) ETS aggravates asthma in childhood Asthmatic children whose mothers smoke have more severe cases of asthma compared with those whose mothers don’t smoke Prenatal smoking is causally associated with increased prevalence of asthma in children Chan-Yeung et al. Respirology. 2003; 8: 131 -139; Courtesy of Getty Images. http: //delivery. gettyimages. com/xc/BB 6074001. jpg? v=1&c=CFW&k=2&d=2 EA 4 B 0 C 59585 DB 42 C 1 FF 2 DD 0 E 5 B 2 E 618 EC 7 C 5022 FB 410 D 56. Accessed October 11, 2007.

Prenatal Smoking and Asthma in Children Analysis of 60 studies revealed that the risk of asthma in school- aged children is increased if either parent smokes; Odds Ratio (OR)a=1. 21 (95% CI, 1. 10 -1. 34) Maternal smoking did have a greater effect than paternal smoking, yet the effect of the father only was clearly significant Results suggest postnatal effect is also important a. The ratio of the odds of development of disease in exposed persons to the odds of development of disease in nonexposed persons. Cook et al. Thorax. 1997; 52(12): 1081 -1094; http: //www. worldofstock. com/closeups/PHE 1195. php. Accessed October 11, 2007.

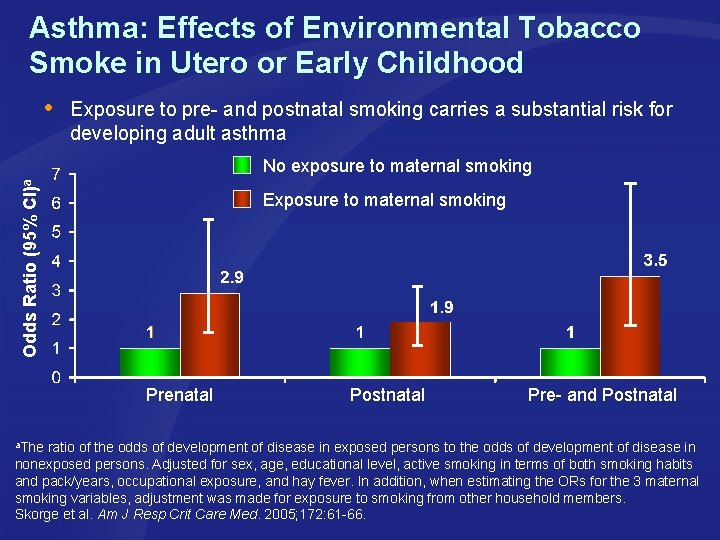

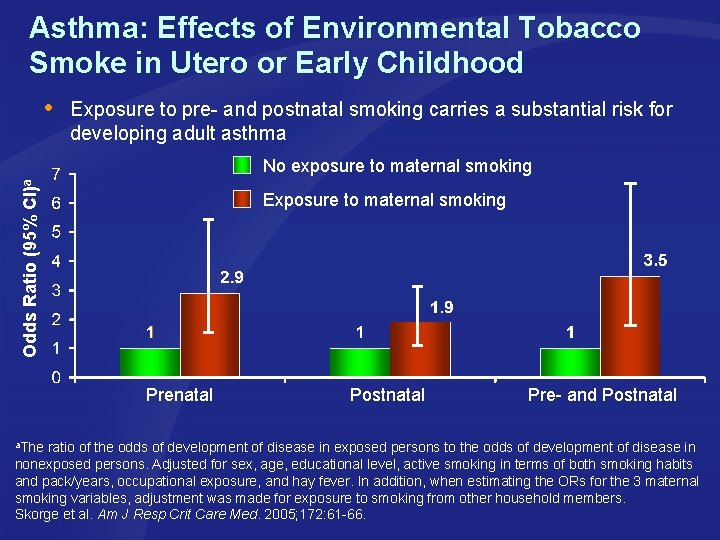

Asthma: Effects of Environmental Tobacco Smoke in Utero or Early Childhood Exposure to pre- and postnatal smoking carries a substantial risk for developing adult asthma Odds Ratio (95% CI)a No exposure to maternal smoking Exposure to maternal smoking Prenatal Postnatal Pre- and Postnatal a. The ratio of the odds of development of disease in exposed persons to the odds of development of disease in nonexposed persons. Adjusted for sex, age, educational level, active smoking in terms of both smoking habits and pack/years, occupational exposure, and hay fever. In addition, when estimating the ORs for the 3 maternal smoking variables, adjustment was made for exposure to smoking from other household members. Skorge et al. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 2005; 172: 61 -66.

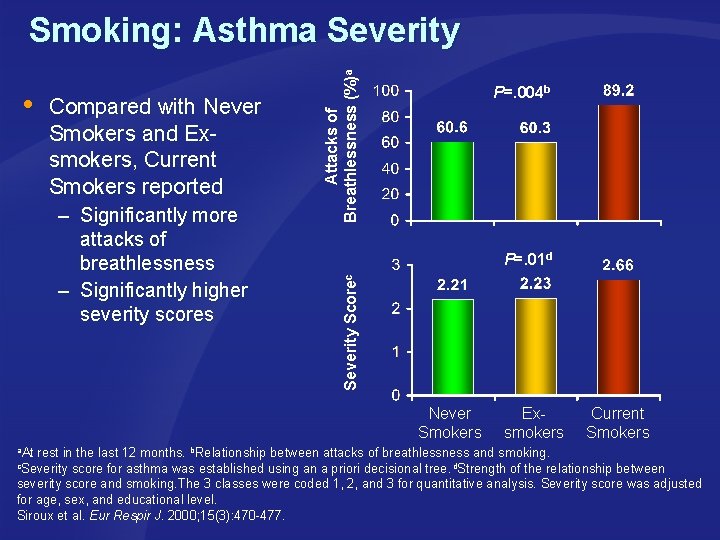

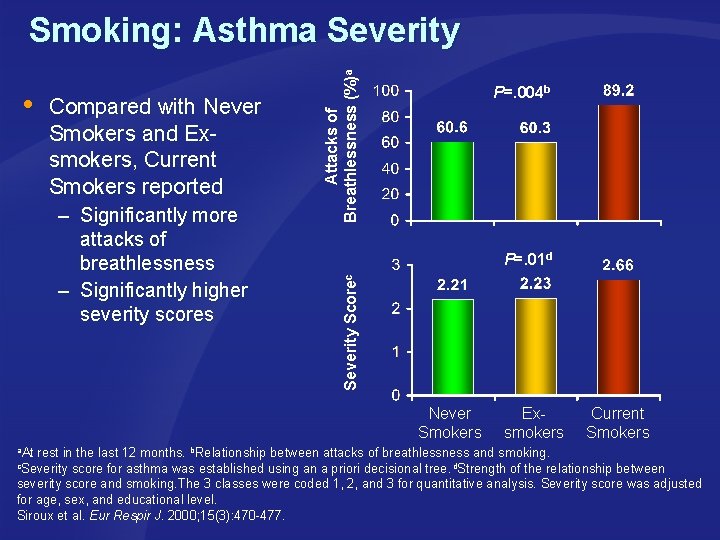

Compared with Never Smokers and Exsmokers, Current Smokers reported P=. 01 d Severity – Significantly more attacks of breathlessness – Significantly higher severity scores P=. 004 b Scorec Attacks of Breathlessness (%)a Smoking: Asthma Severity Never Smokers Exsmokers Current Smokers a. At rest in the last 12 months. b. Relationship between attacks of breathlessness and smoking. c. Severity score for asthma was established using an a priori decisional tree. d. Strength of the relationship between severity score and smoking. The 3 classes were coded 1, 2, and 3 for quantitative analysis. Severity score was adjusted for age, sex, and educational level. Siroux et al. Eur Respir J. 2000; 15(3): 470 -477.

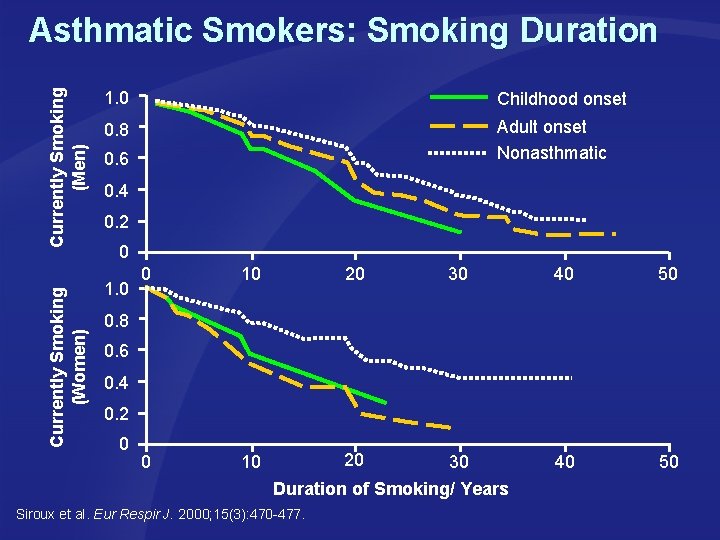

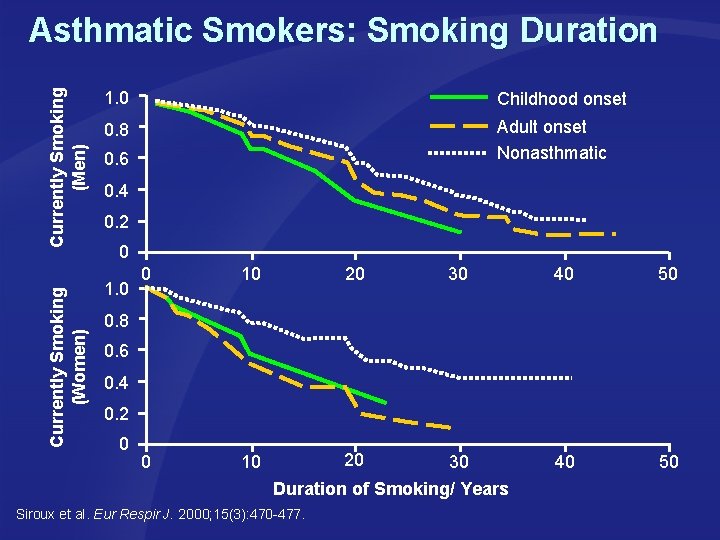

Currently Smoking (Men) 1. 0 Childhood onset 0. 8 Adult onset Nonasthmatic Currently Smoking (Women) Asthmatic Smokers: Smoking Duration 1. 0 0. 6 0. 4 0. 2 0 0 10 20 30 40 50 0. 8 0. 6 0. 4 0. 2 0 Duration of Smoking/ Years Siroux et al. Eur Respir J. 2000; 15(3): 470 -477.

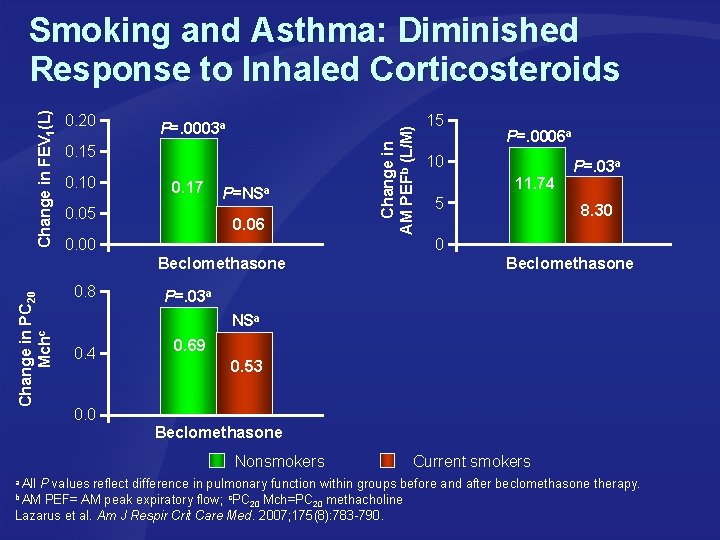

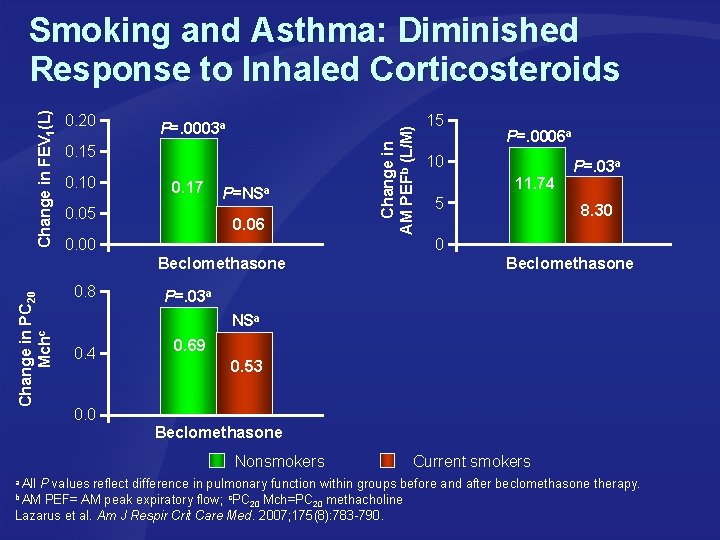

0. 20 P=. 0003 a 0. 15 0. 10 0. 17 0. 05 P=NSa 0. 06 Change in AM PEFb (L/M) Change in FEV 1(L) Smoking and Asthma: Diminished Response to Inhaled Corticosteroids Beclomethasone Change in PC 20 Mchc P=. 0006 a 10 11. 74 5 P=. 03 a 8. 30 0 0. 00 0. 8 15 Beclomethasone P=. 03 a NSa 0. 4 0. 0 0. 69 0. 53 Beclomethasone Nonsmokers Current smokers a All P values reflect difference in pulmonary function within groups before and after beclomethasone therapy. b AM PEF= AM peak expiratory flow; c. PC Mch=PC methacholine 20 20 Lazarus et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007; 175(8): 783 -790.

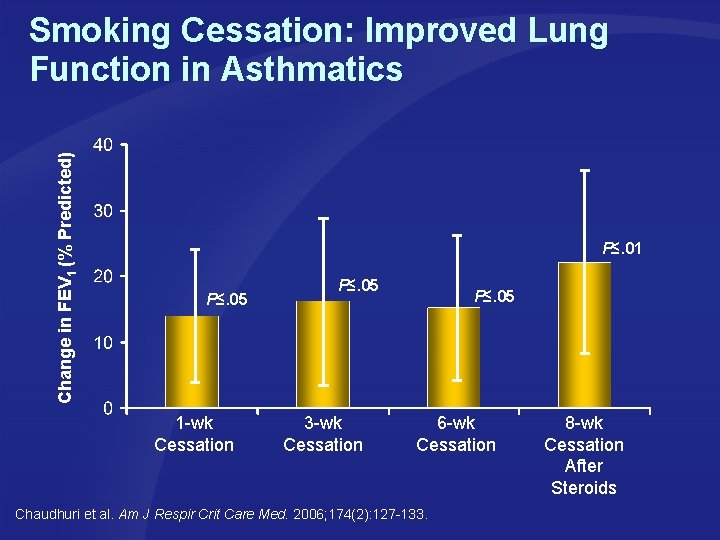

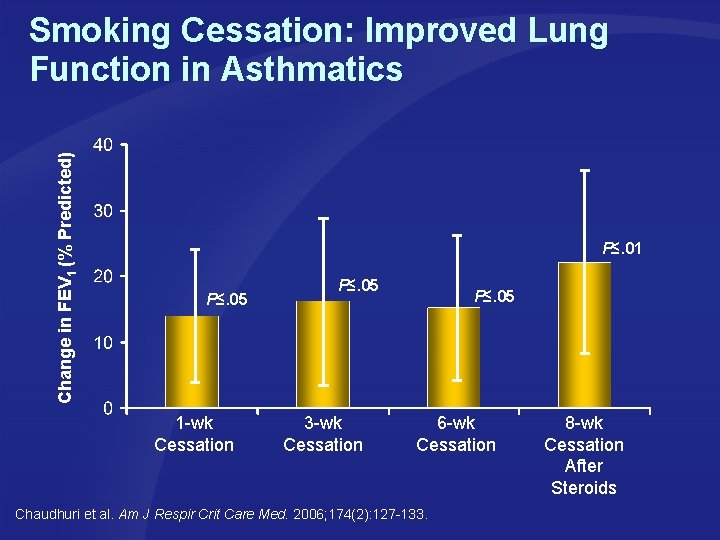

Change in FEV 1 (% Predicted) Smoking Cessation: Improved Lung Function in Asthmatics P≤. 01 P≤. 05 1 -wk Cessation P≤. 05 3 -wk Cessation P≤. 05 6 -wk Cessation Chaudhuri et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006; 174(2): 127 -133. 8 -wk Cessation After Steroids

Summary: Smoking and Asthma Environmental tobacco smoke aggravates asthma in childhood Asthmatic children whose parents smoke have more severe asthma than those whose parents don’t smoke Exposure to pre- and postnatal smoking carries a substantial risk of developing adult asthma Smoking asthmatics have a diminished response to inhaled corticosteroids

Smoking and Tuberculosis

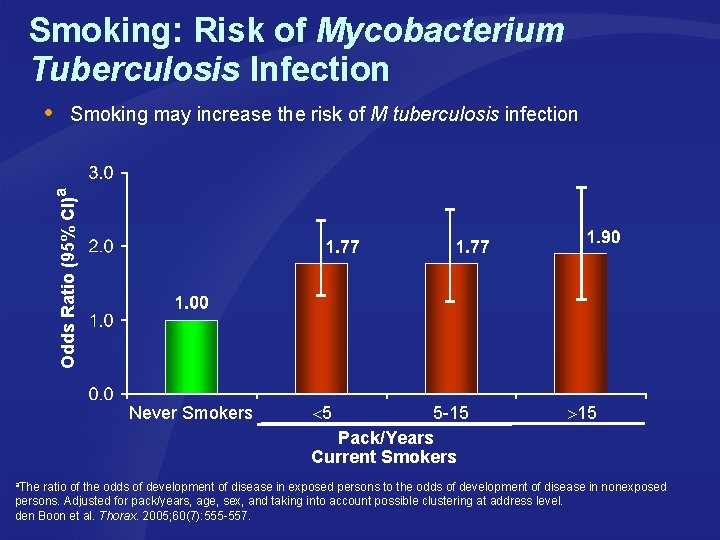

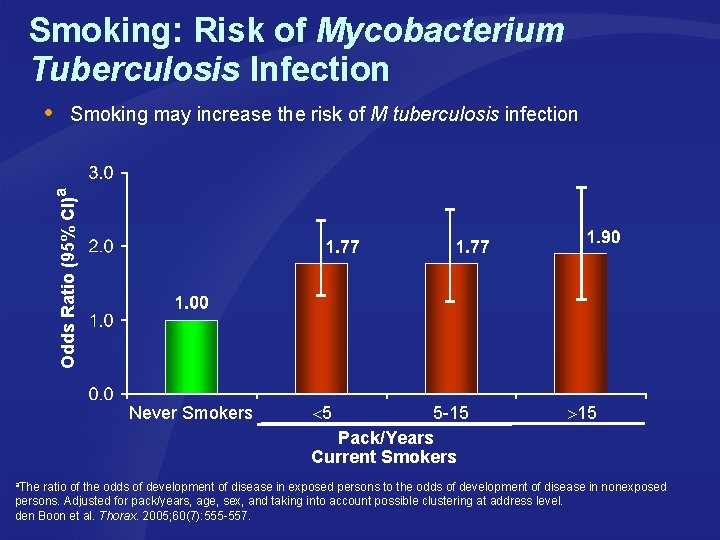

Smoking: Risk of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Infection Smoking may increase the risk of M tuberculosis infection Odds Ratio (95% CI)a Never Smokers 5 5 -15 Pack/Years Current Smokers 15 a. The ratio of the odds of development of disease in exposed persons to the odds of development of disease in nonexposed persons. Adjusted for pack/years, age, sex, and taking into account possible clustering at address level. den Boon et al. Thorax. 2005; 60(7): 555 -557.

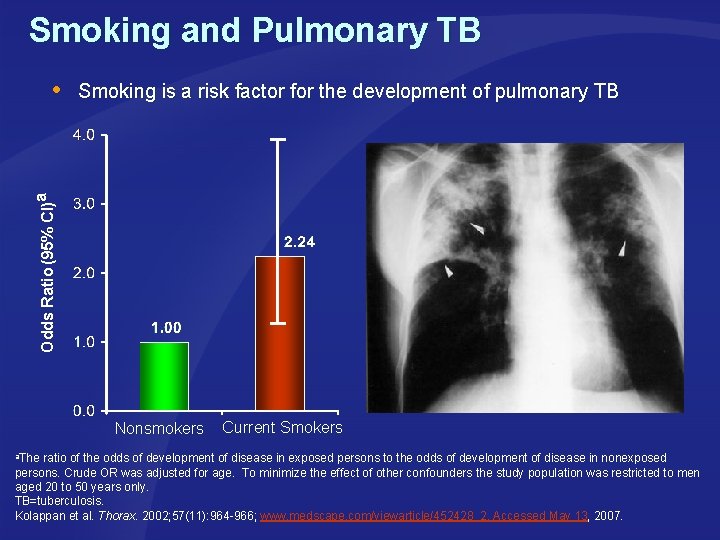

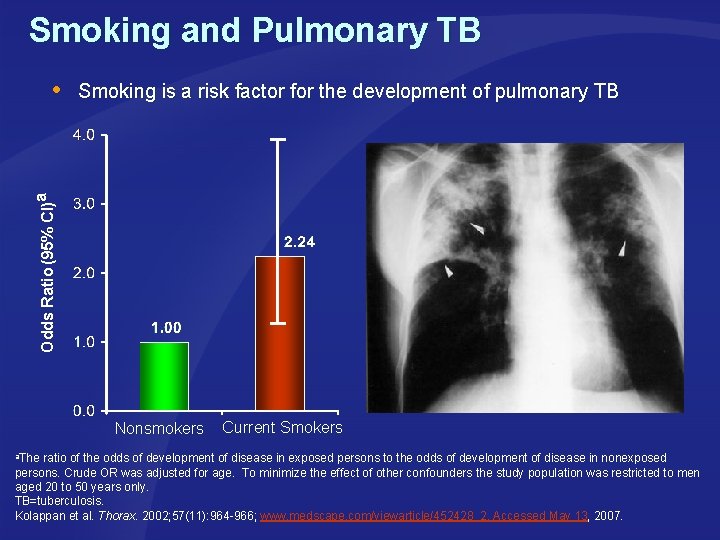

Smoking and Pulmonary TB Smoking is a risk factor for the development of pulmonary TB Odds Ratio (95% CI)a Nonsmokers Current Smokers a. The ratio of the odds of development of disease in exposed persons to the odds of development of disease in nonexposed persons. Crude OR was adjusted for age. To minimize the effect of other confounders the study population was restricted to men aged 20 to 50 years only. TB=tuberculosis. Kolappan et al. Thorax. 2002; 57(11): 964 -966; www. medscape. com/viewarticle/452428_2. Accessed May 13, 2007.

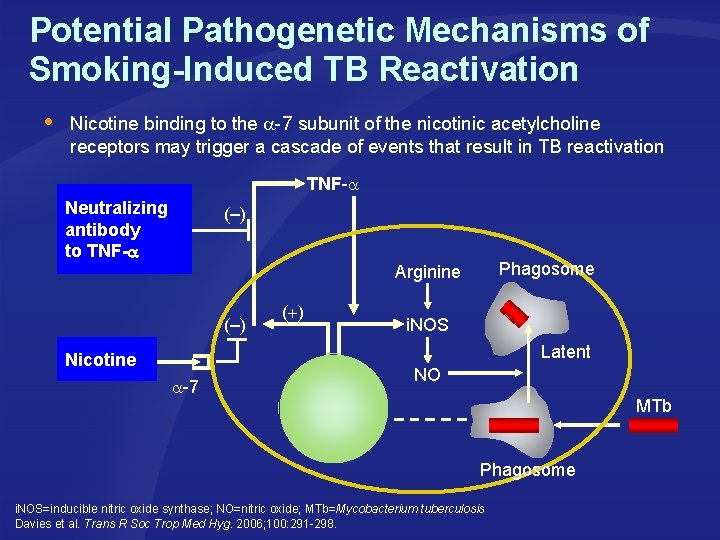

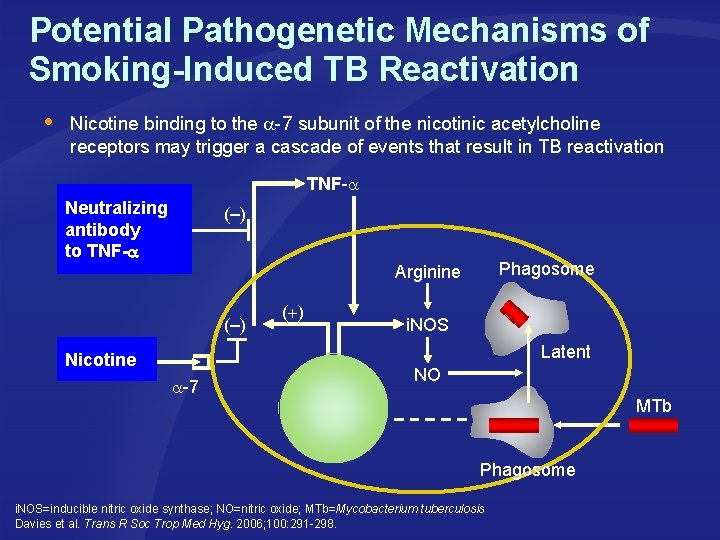

Potential Pathogenetic Mechanisms of Smoking-Induced TB Reactivation Nicotine binding to the -7 subunit of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptors may trigger a cascade of events that result in TB reactivation TNF- Neutralizing antibody to TNF- (–) Phagosome Arginine (–) ( ) i. NOS Latent Nicotine -7 NO MTb Phagosome i. NOS=inducible nitric oxide synthase; NO=nitric oxide; MTb=Mycobacterium tuberculosis Davies et al. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2006; 100: 291 -298.

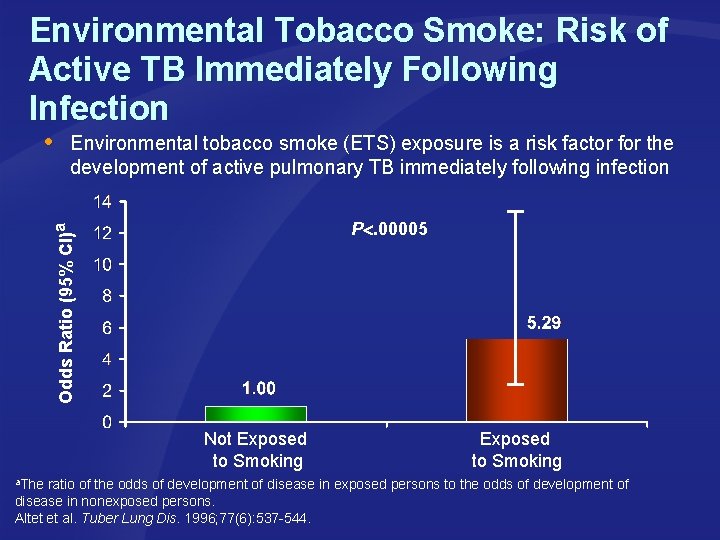

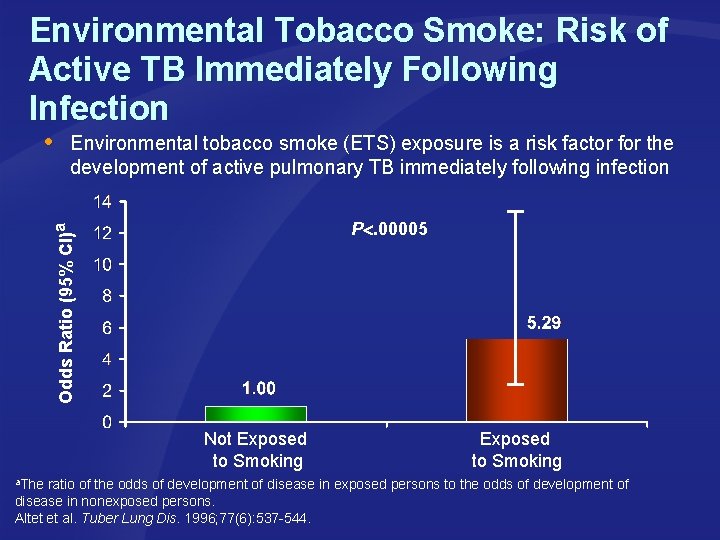

Environmental Tobacco Smoke: Risk of Active TB Immediately Following Infection Environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) exposure is a risk factor for the development of active pulmonary TB immediately following infection Odds Ratio (95% CI)a P. 00005 Not Exposed to Smoking a. The ratio of the odds of development of disease in exposed persons to the odds of development of disease in nonexposed persons. Altet et al. Tuber Lung Dis. 1996; 77(6): 537 -544.

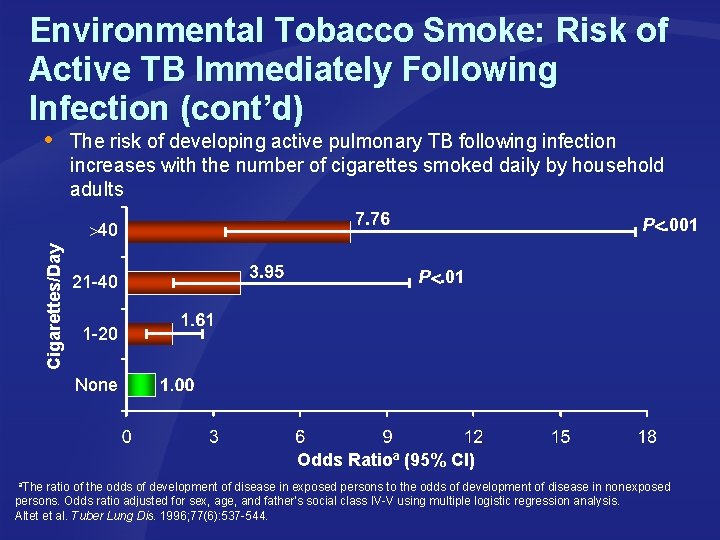

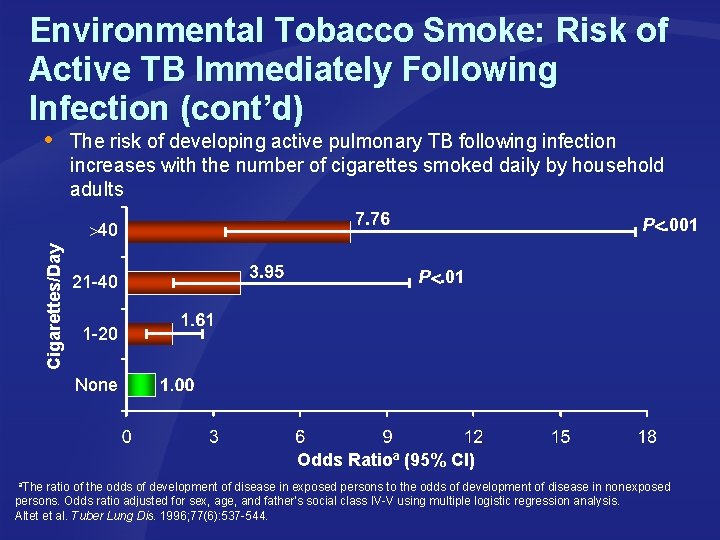

Environmental Tobacco Smoke: Risk of Active TB Immediately Following Infection (cont’d) The risk of developing active pulmonary TB following infection increases with the number of cigarettes smoked daily by household adults P. 001 Cigarettes/Day 40 21 -40 P. 01 1 -20 None Odds Ratioa (95% CI) a. The ratio of the odds of development of disease in exposed persons to the odds of development of disease in nonexposed persons. Odds ratio adjusted for sex, age, and father's social class IV-V using multiple logistic regression analysis. Altet et al. Tuber Lung Dis. 1996; 77(6): 537 -544.

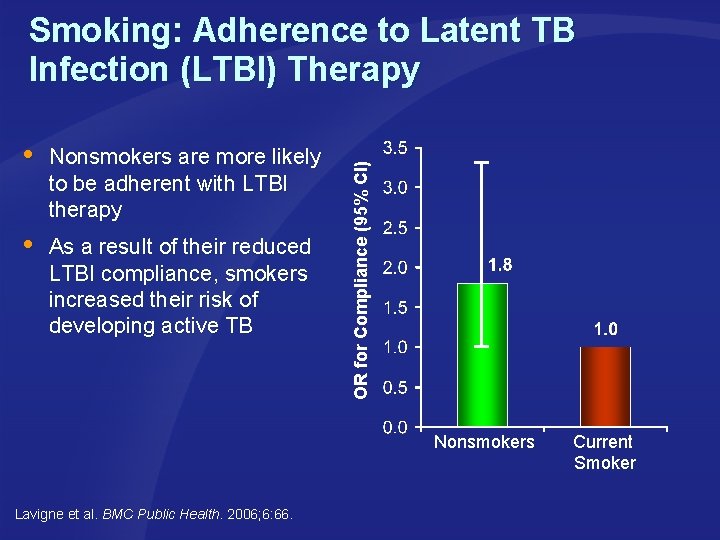

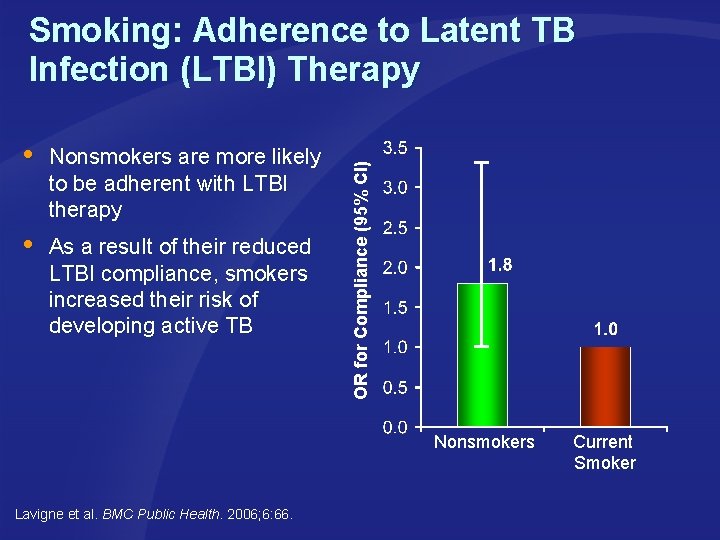

Nonsmokers are more likely to be adherent with LTBI therapy As a result of their reduced LTBI compliance, smokers increased their risk of developing active TB OR for Compliance (95% CI) Smoking: Adherence to Latent TB Infection (LTBI) Therapy Nonsmokers Lavigne et al. BMC Public Health. 2006; 6: 66. Current Smoker

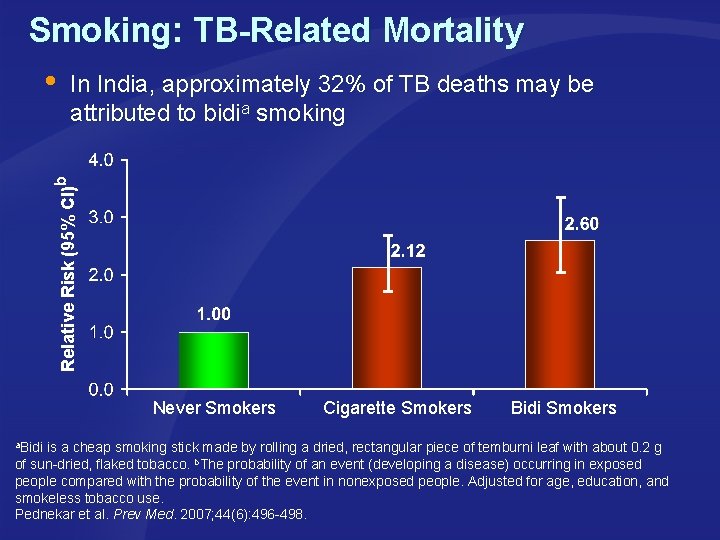

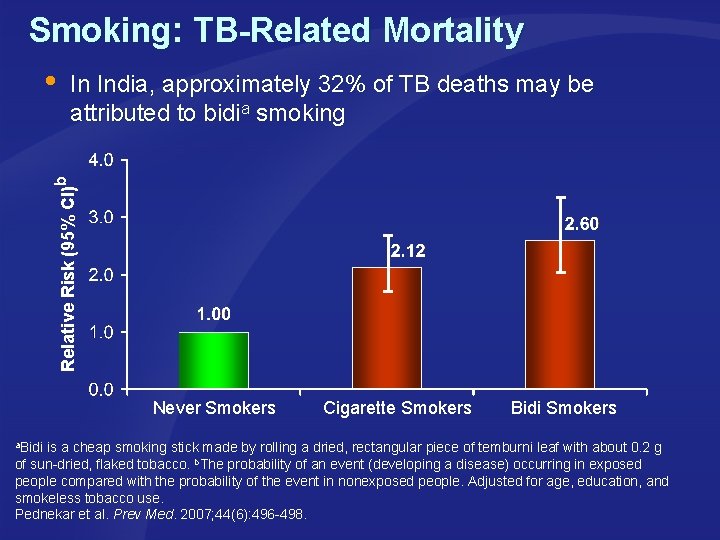

Smoking: TB-Related Mortality In India, approximately 32% of TB deaths may be attributed to bidia smoking Relative Risk (95% CI)b Never Smokers Cigarette Smokers Bidi Smokers a. Bidi is a cheap smoking stick made by rolling a dried, rectangular piece of temburni leaf with about 0. 2 g of sun-dried, flaked tobacco. b. The probability of an event (developing a disease) occurring in exposed people compared with the probability of the event in nonexposed people. Adjusted for age, education, and smokeless tobacco use. Pednekar et al. Prev Med. 2007; 44(6): 496 -498.

Smoking and Lung Cancer

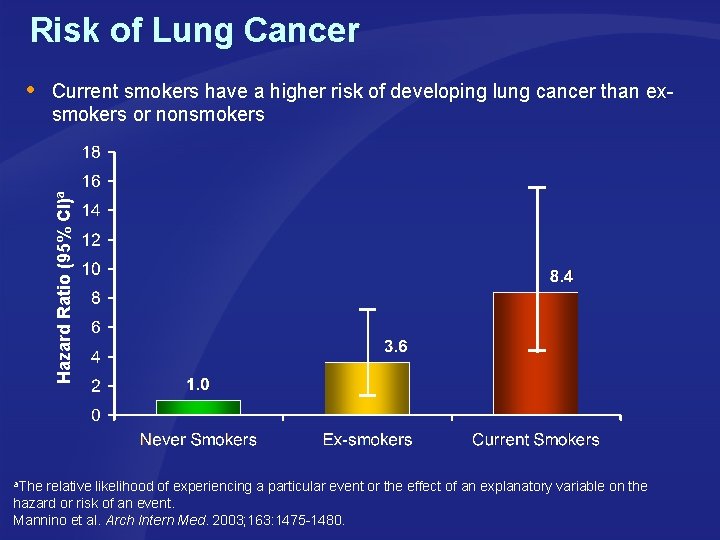

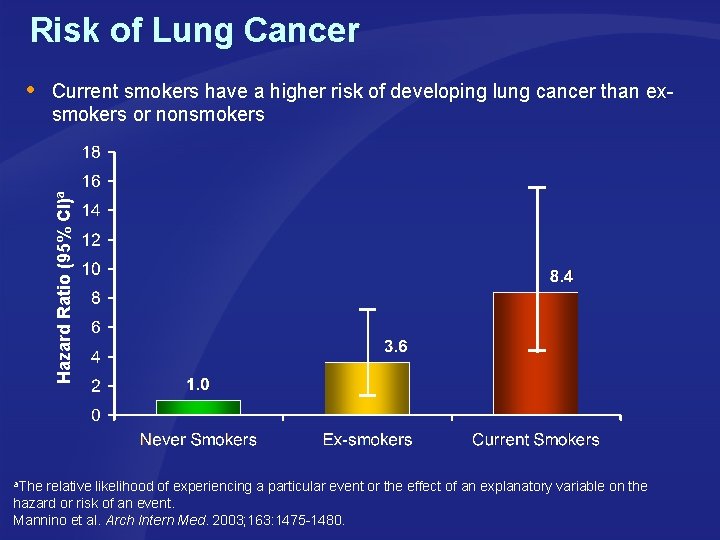

Risk of Lung Cancer Current smokers have a higher risk of developing lung cancer than exsmokers or nonsmokers Hazard Ratio (95% CI)a a. The relative likelihood of experiencing a particular event or the effect of an explanatory variable on the hazard or risk of an event. Mannino et al. Arch Intern Med. 2003; 163: 1475 -1480.

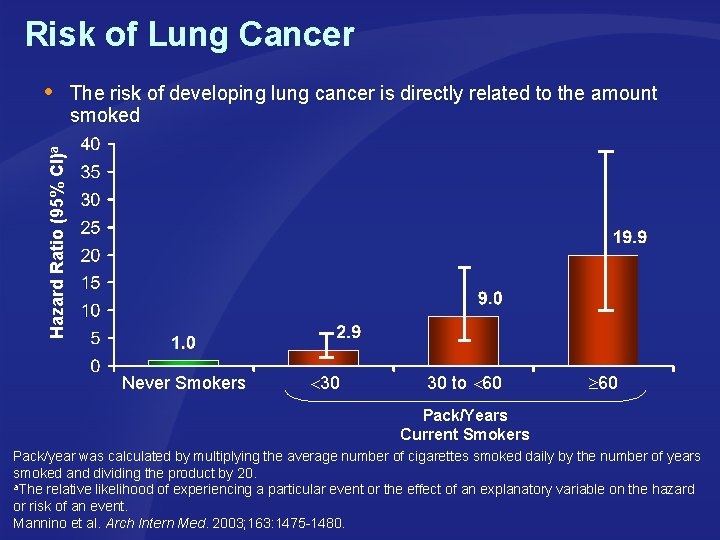

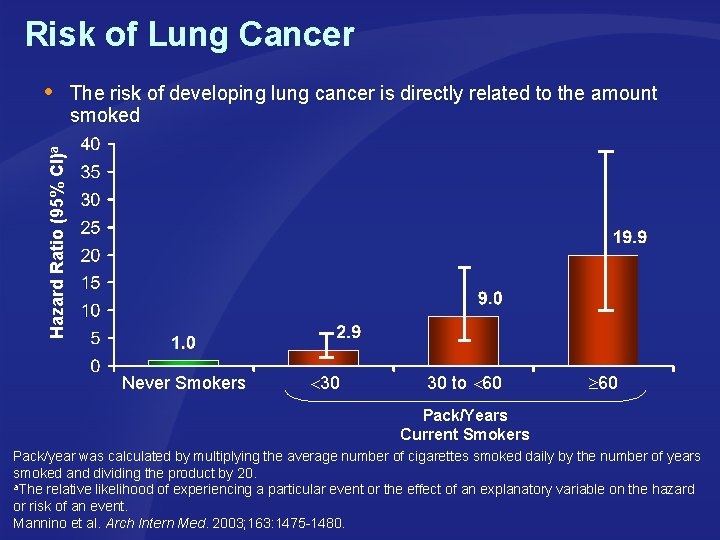

Risk of Lung Cancer The risk of developing lung cancer is directly related to the amount smoked Hazard Ratio (95% CI)a Never Smokers 30 30 to 60 Pack/Years Current Smokers Pack/year was calculated by multiplying the average number of cigarettes smoked daily by the number of years smoked and dividing the product by 20. a. The relative likelihood of experiencing a particular event or the effect of an explanatory variable on the hazard or risk of an event. Mannino et al. Arch Intern Med. 2003; 163: 1475 -1480.

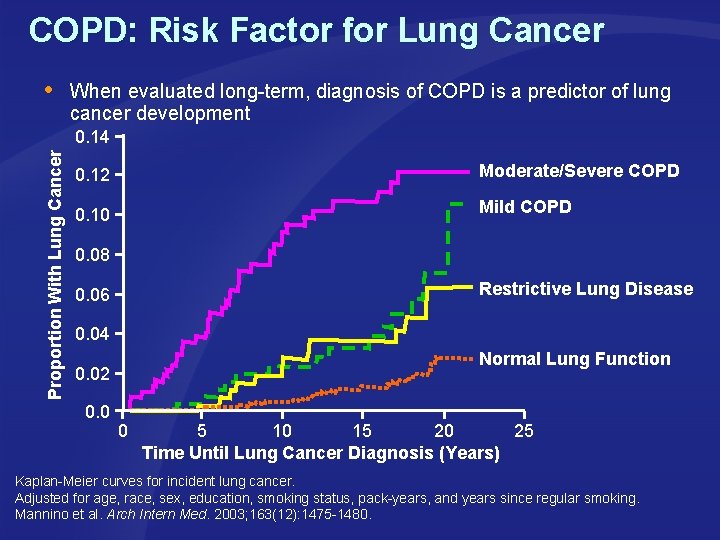

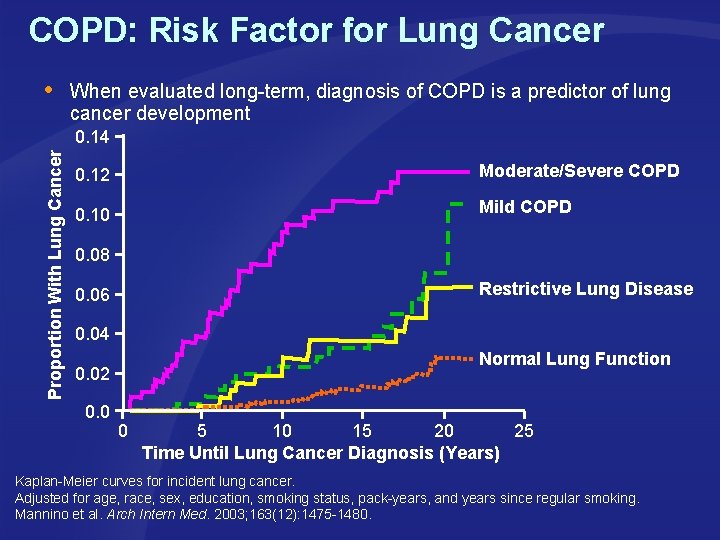

COPD: Risk Factor for Lung Cancer When evaluated long-term, diagnosis of COPD is a predictor of lung cancer development Proportion With Lung Cancer 0. 14 0. 12 Moderate/Severe COPD 0. 10 Mild COPD 0. 08 Restrictive Lung Disease 0. 06 0. 04 Normal Lung Function 0. 02 0. 0 0 5 10 15 20 25 Time Until Lung Cancer Diagnosis (Years) Kaplan-Meier curves for incident lung cancer. Adjusted for age, race, sex, education, smoking status, pack-years, and years since regular smoking. Mannino et al. Arch Intern Med. 2003; 163(12): 1475 -1480.

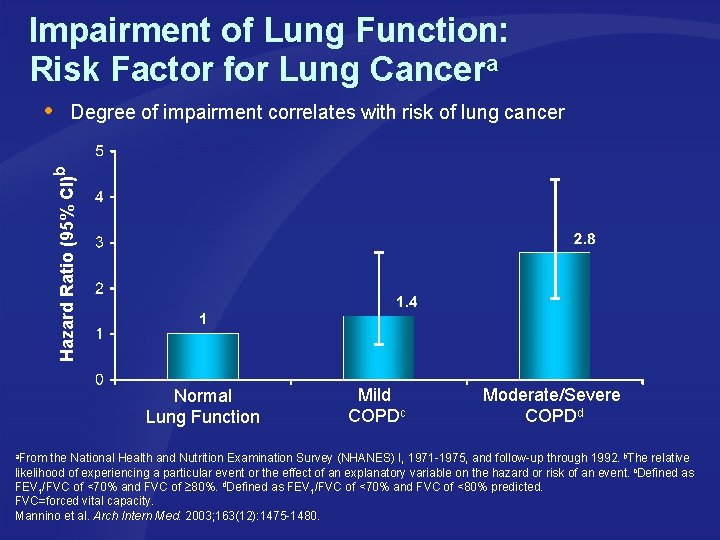

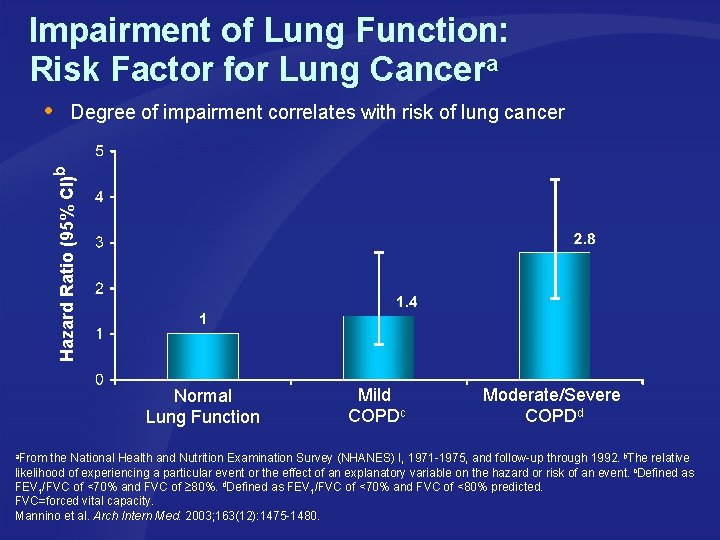

Impairment of Lung Function: Risk Factor for Lung Cancera Degree of impairment correlates with risk of lung cancer Hazard Ratio (95% CI)b Normal Lung Function Mild COPDc Moderate/Severe COPDd a. From the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) I, 1971 -1975, and follow-up through 1992. b. The relative likelihood of experiencing a particular event or the effect of an explanatory variable on the hazard or risk of an event. c. Defined as FEV 1/FVC of <70% and FVC of 80%. d. Defined as FEV 1/FVC of <70% and FVC of <80% predicted. FVC=forced vital capacity. Mannino et al. Arch Intern Med. 2003; 163(12): 1475 -1480.

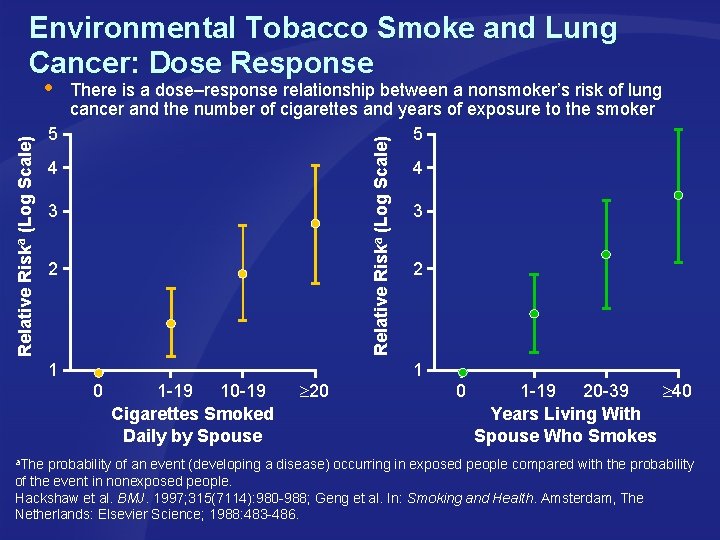

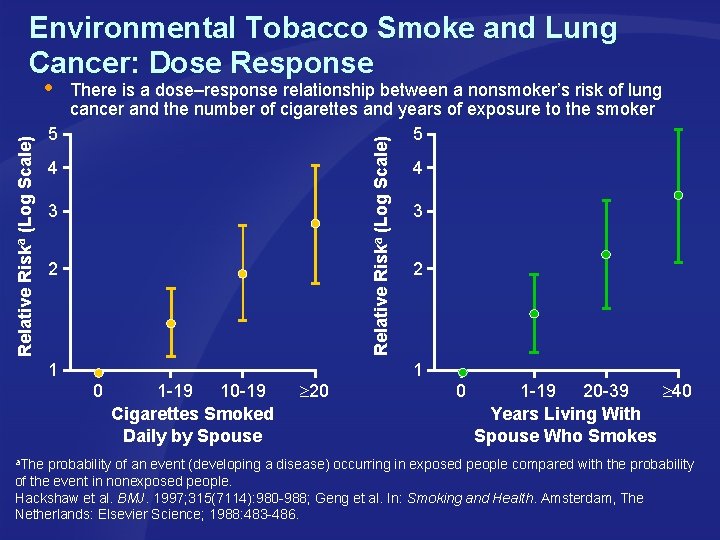

Environmental Tobacco Smoke and Lung Cancer: Dose Response There is a dose–response relationship between a nonsmoker’s risk of lung cancer and the number of cigarettes and years of exposure to the smoker 5 5 Relative Riska (Log Scale) 4 3 2 1 0 1 -19 10 -19 Cigarettes Smoked Daily by Spouse 20 4 3 2 1 0 1 -19 20 -39 40 Years Living With Spouse Who Smokes a. The probability of an event (developing a disease) occurring in exposed people compared with the probability of the event in nonexposed people. Hackshaw et al. BMJ. 1997; 315(7114): 980 -988; Geng et al. In: Smoking and Health. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Science; 1988: 483 -486.

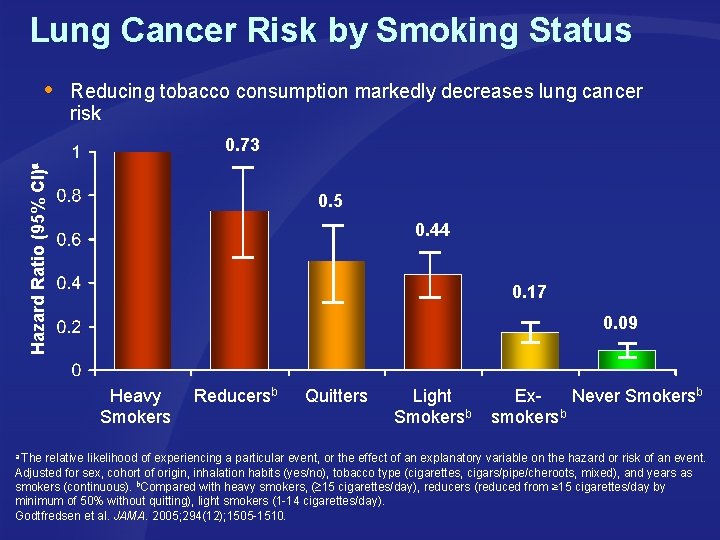

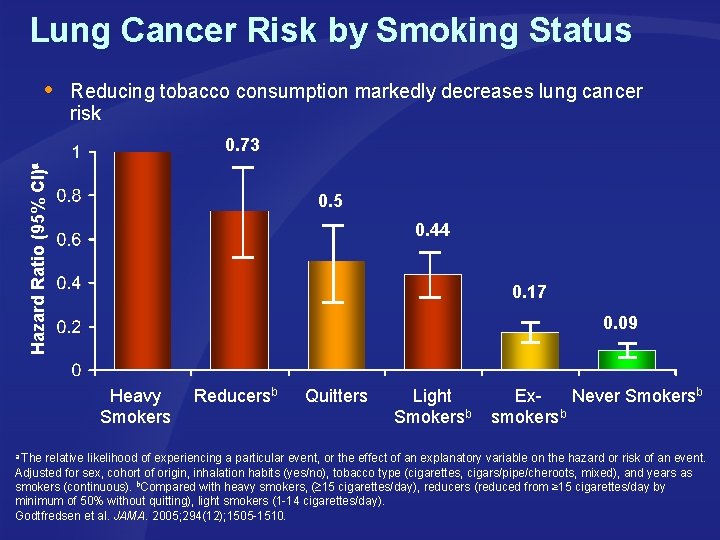

Lung Cancer Risk by Smoking Status Reducing tobacco consumption markedly decreases lung cancer risk Hazard Ratio (95% CI)a 0. 73 0. 5 0. 44 0. 17 0. 09 Heavy Smokers Reducersb Quitters Light Smokersb Ex. Never Smokersb smokersb a The relative likelihood of experiencing a particular event, or the effect of an explanatory variable on the hazard or risk of an event. Adjusted for sex, cohort of origin, inhalation habits (yes/no), tobacco type (cigarettes, cigars/pipe/cheroots, mixed), and years as smokers (continuous). b. Compared with heavy smokers, ( 15 cigarettes/day), reducers (reduced from ≥ 15 cigarettes/day by minimum of 50% without quitting), light smokers (1 -14 cigarettes/day). Godtfredsen et al. JAMA. 2005; 294(12); 1505 -1510.

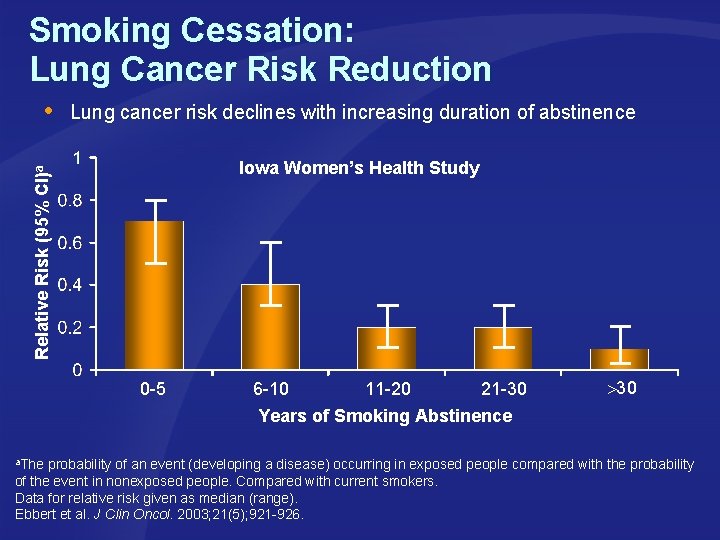

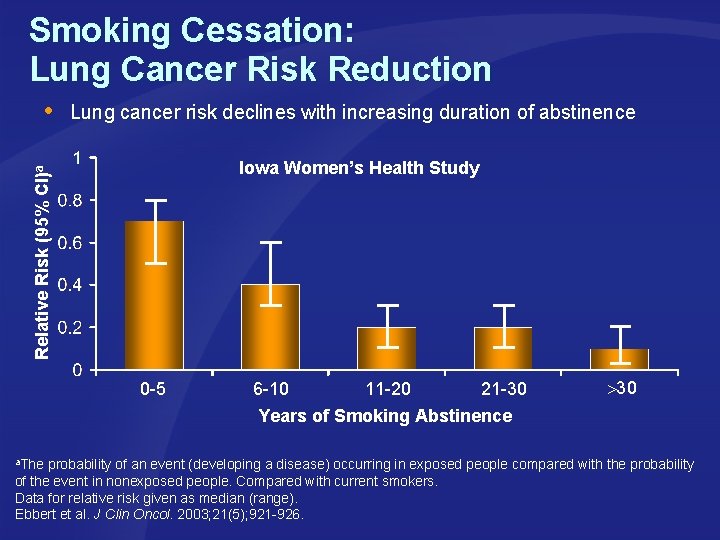

Smoking Cessation: Lung Cancer Risk Reduction Lung cancer risk declines with increasing duration of abstinence Iowa Women’s Health Study Relative Risk (95% CI)a 0 -5 6 -10 11 -20 21 -30 Years of Smoking Abstinence 30 a. The probability of an event (developing a disease) occurring in exposed people compared with the probability of the event in nonexposed people. Compared with current smokers. Data for relative risk given as median (range). Ebbert et al. J Clin Oncol. 2003; 21(5); 921 -926.

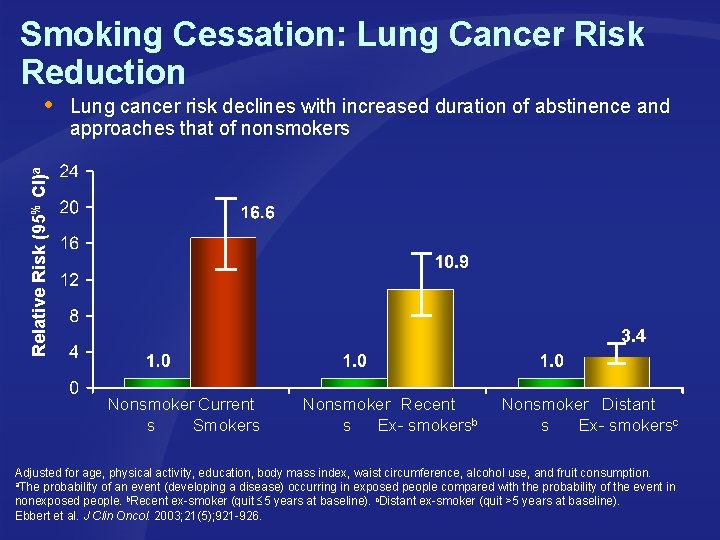

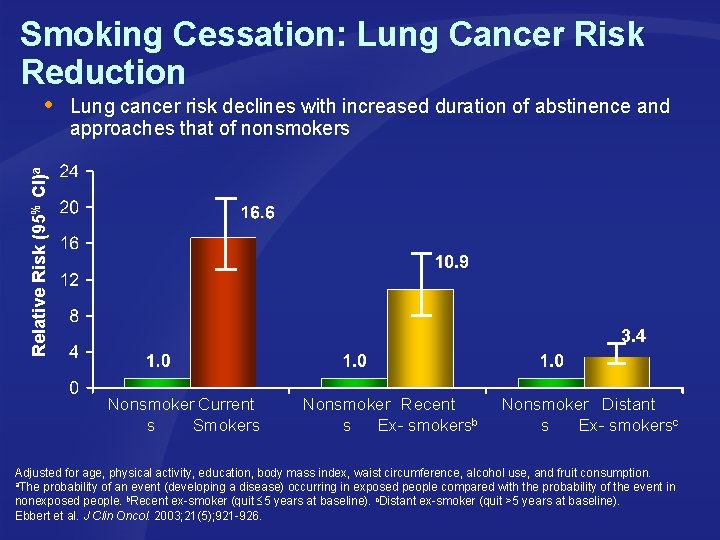

Smoking Cessation: Lung Cancer Risk Reduction Lung cancer risk declines with increased duration of abstinence and approaches that of nonsmokers Relative Risk (95% CI)a 3. 4 Nonsmoker Current s Smokers Nonsmoker Recent s Ex- smokersb Nonsmoker Distant s Ex- smokersc Adjusted for age, physical activity, education, body mass index, waist circumference, alcohol use, and fruit consumption. a. The probability of an event (developing a disease) occurring in exposed people compared with the probability of the event in nonexposed people. b. Recent ex-smoker (quit 5 years at baseline). c. Distant ex-smoker (quit >5 years at baseline). Ebbert et al. J Clin Oncol. 2003; 21(5); 921 -926.

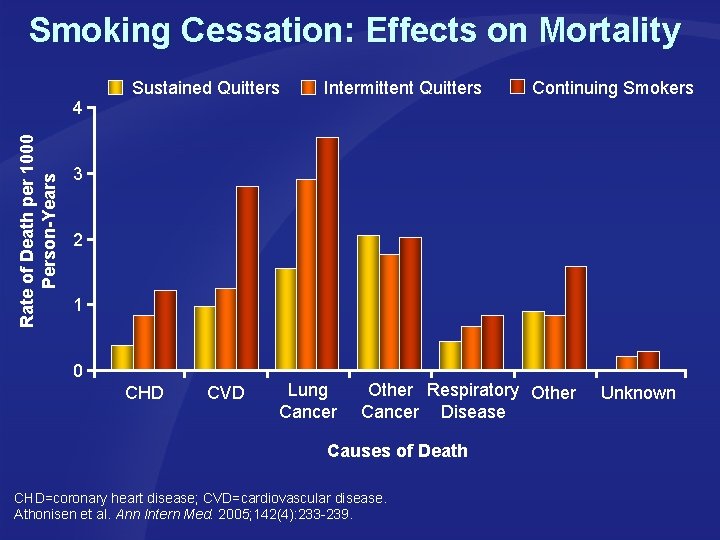

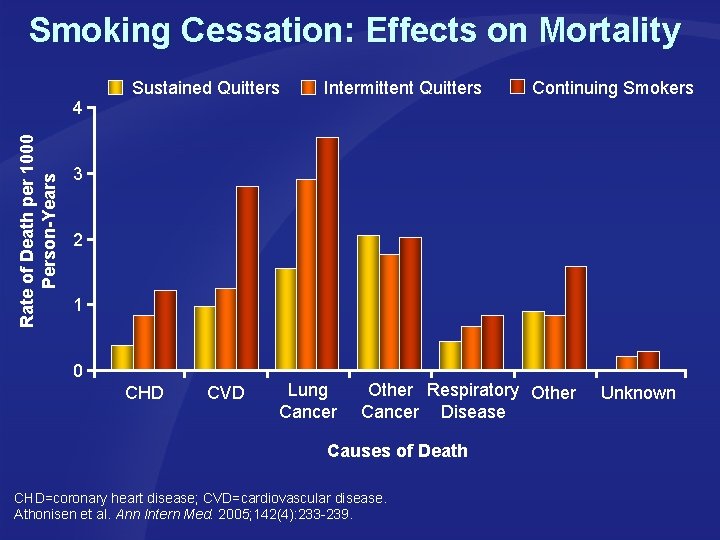

Smoking Cessation: Effects on Mortality Sustained Quitters Intermittent Quitters Continuing Smokers Rate of Death per 1000 Person-Years 4 3 2 1 0 CHD CVD Lung Cancer Other Respiratory Other Cancer Disease Causes of Death CHD=coronary heart disease; CVD=cardiovascular disease. Athonisen et al. Ann Intern Med. 2005; 142(4): 233 -239. Unknown

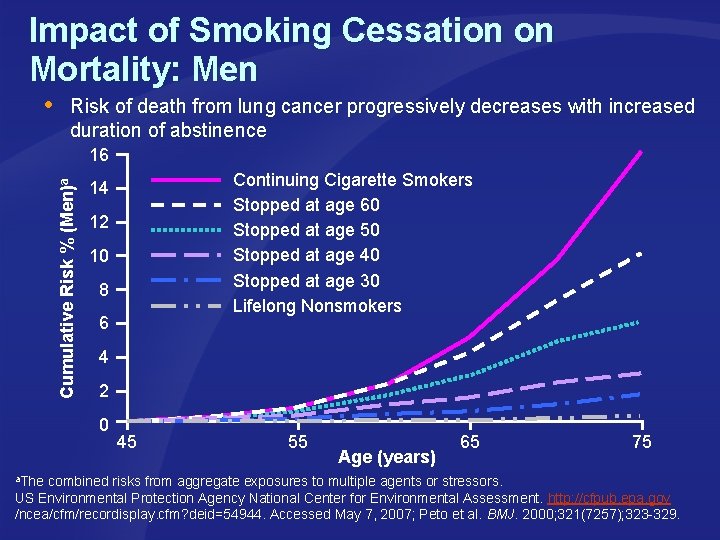

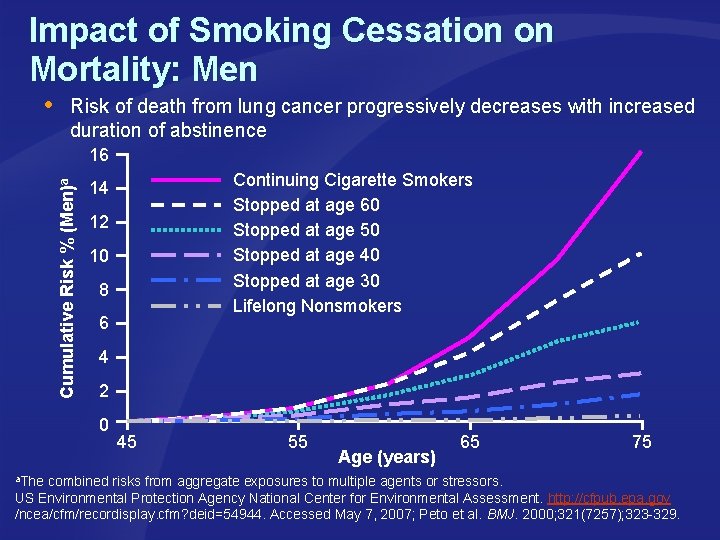

Impact of Smoking Cessation on Mortality: Men Risk of death from lung cancer progressively decreases with increased duration of abstinence Cumulative Risk % (Men)a 16 Continuing Cigarette Smokers Stopped at age 60 Stopped at age 50 Stopped at age 40 Stopped at age 30 Lifelong Nonsmokers 14 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 45 55 Age (years) 65 75 a. The combined risks from aggregate exposures to multiple agents or stressors. US Environmental Protection Agency National Center for Environmental Assessment. http: //cfpub. epa. gov /ncea/cfm/recordisplay. cfm? deid=54944. Accessed May 7, 2007; Peto et al. BMJ. 2000; 321(7257); 323 -329.

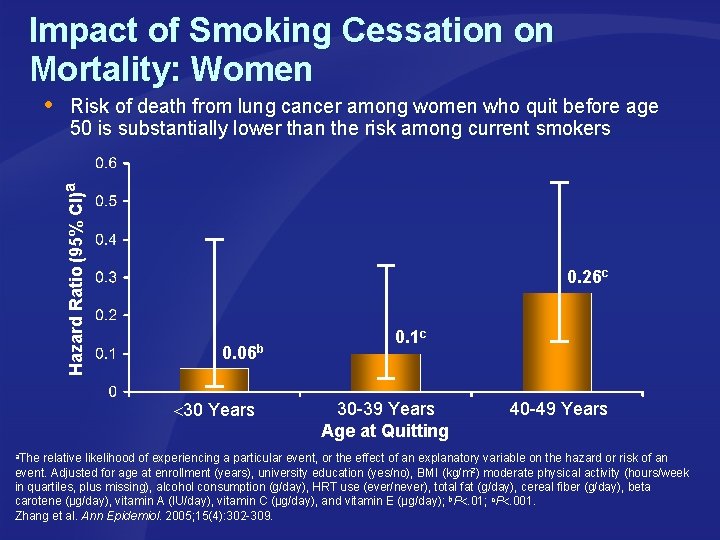

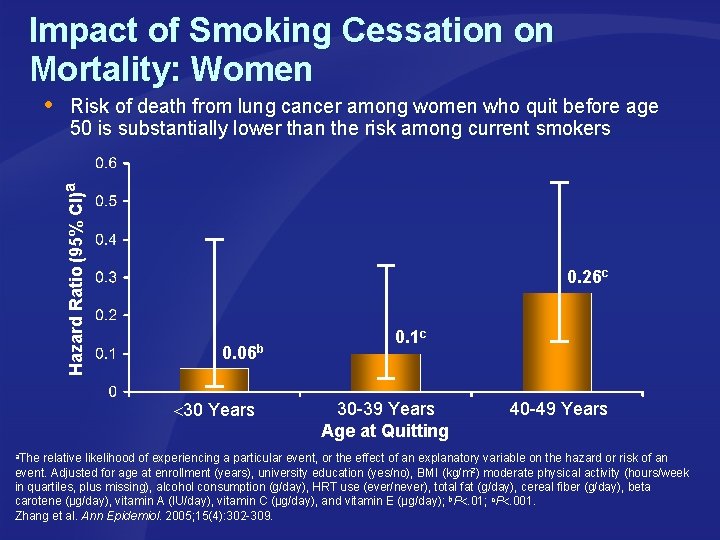

Impact of Smoking Cessation on Mortality: Women Risk of death from lung cancer among women who quit before age 50 is substantially lower than the risk among current smokers Hazard Ratio (95% CI)a 0. 26 c 0. 06 b 30 Years 0. 1 c 30 -39 Years Age at Quitting 40 -49 Years a. The relative likelihood of experiencing a particular event, or the effect of an explanatory variable on the hazard or risk of an event. Adjusted for age at enrollment (years), university education (yes/no), BMI (kg/m 2) moderate physical activity (hours/week in quartiles, plus missing), alcohol consumption (g/day), HRT use (ever/never), total fat (g/day), cereal fiber (g/day), beta carotene (µg/day), vitamin A (IU/day), vitamin C (µg/day), and vitamin E (µg/day); b. P. 01; c. P. 001. Zhang et al. Ann Epidemiol. 2005; 15(4): 302 -309.

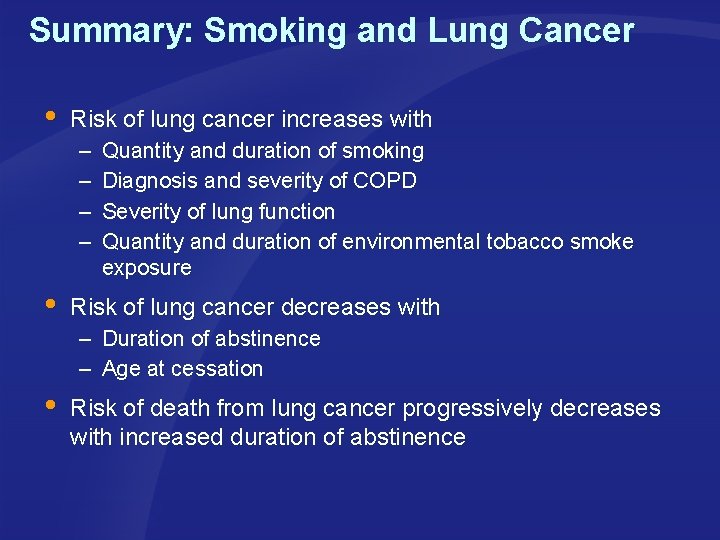

Summary: Smoking and Lung Cancer Risk of lung cancer increases with – – Quantity and duration of smoking Diagnosis and severity of COPD Severity of lung function Quantity and duration of environmental tobacco smoke exposure Risk of lung cancer decreases with – Duration of abstinence – Age at cessation Risk of death from lung cancer progressively decreases with increased duration of abstinence