The Practicality of Parallel Planning The necessity and

- Slides: 10

The Practicality of Parallel Planning: The necessity and usefulness of a back-up major for students Presented by: Philip T. Johnson, M. Ed. Senior Academic Advising Counselor – The Jeannine Rainbolt College of Education University of Oklahoma pjohnson 77@ou. edu

What is parallel planning in advising? Parallel planning is an advising technique utilized when a student’s inability to continue in their major or a student’s educational intention to change from their major occurs. Inability to continue in a major can be academic, dispositional/emotional, or financial in nature…while intention may be related to an outright decision to switch majors due to a change in the student’s academic or professional interests. Parallel planning often involves effort to establish a “backup major” or “parachute plan” so should a change in major be required or desired, the pathway to shifting to the backup major will be as seamless as possible. Parallel planning is best conducted early in the student’s collegiate experience, and it is often best orchestrated by the college in which the student’s initial major is governed.

What can parallel planning measure? Parallel planning often aims to measure the following criteria when considering a backup major: Ø A student’s natural or preferred academic interests and professional aims Ø A student’s history of coursework performance (highest and lowest grades) Ø A student’s examination of strengths and weaknesses with relation to performance characteristics (communication, creativity, organization, teamwork capability) Ø A student’s “ideal” or “preferred” work environment or professional career Ø An analysis of different majors based on GPA requirements, length of time to complete if major was changed, and analysis of a possible major transition

The importance of parallel planning for both a college major and its profession In 2011, during the onset of the Recession, USA Today published a story in their College section titled “Should you have a ‘backup’ career? ” These excerpts highlight the importance of parallel planning: “…advisors are now counseling students to consider a ‘backup career’ or at least begin to plan in case their dream career doesn’t materialize. ” “…advisors recommend students look at alternatives to their job industry as well. ” “…Students should consider looking into a backup career or reflect on themselves more in depth to find an alternative job that can help pay for all those college loans that are slowly starting to enter the mailboxes. ” Source found at - http: //college. usatoday. com/2011/12/28/should-youhave-a-backup-career/

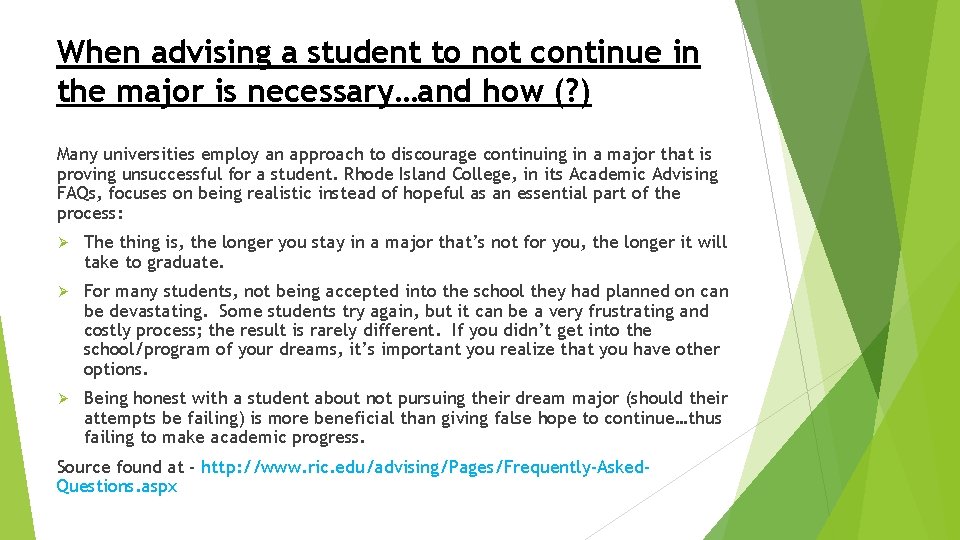

When advising a student to not continue in the major is necessary…and how (? ) Many universities employ an approach to discourage continuing in a major that is proving unsuccessful for a student. Rhode Island College, in its Academic Advising FAQs, focuses on being realistic instead of hopeful as an essential part of the process: Ø The thing is, the longer you stay in a major that’s not for you, the longer it will take to graduate. Ø For many students, not being accepted into the school they had planned on can be devastating. Some students try again, but it can be a very frustrating and costly process; the result is rarely different. If you didn’t get into the school/program of your dreams, it’s important you realize that you have other options. Ø Being honest with a student about not pursuing their dream major (should their attempts be failing) is more beneficial than giving false hope to continue…thus failing to make academic progress. Source found at - http: //www. ric. edu/advising/Pages/Frequently-Asked. Questions. aspx

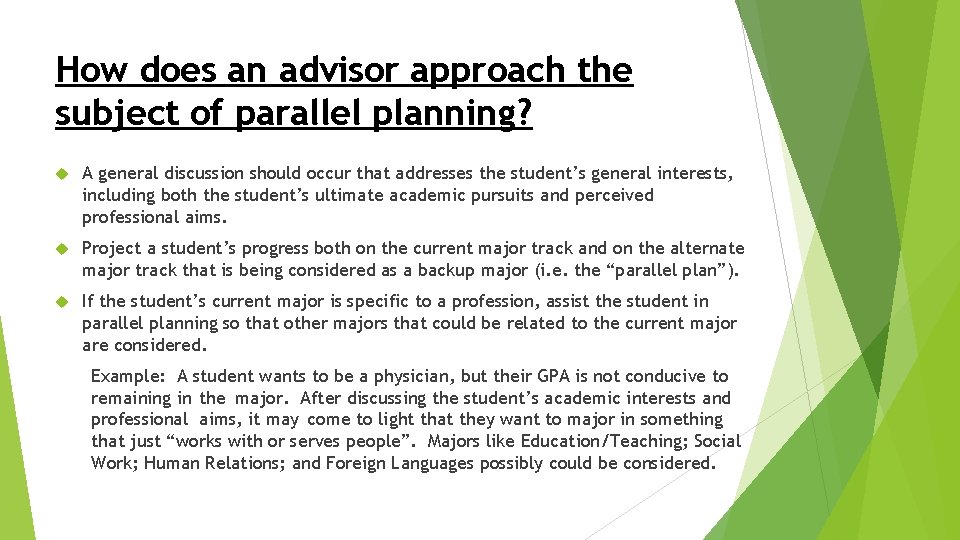

How does an advisor approach the subject of parallel planning? A general discussion should occur that addresses the student’s general interests, including both the student’s ultimate academic pursuits and perceived professional aims. Project a student’s progress both on the current major track and on the alternate major track that is being considered as a backup major (i. e. the “parallel plan”). If the student’s current major is specific to a profession, assist the student in parallel planning so that other majors that could be related to the current major are considered. Example: A student wants to be a physician, but their GPA is not conducive to remaining in the major. After discussing the student’s academic interests and professional aims, it may come to light that they want to major in something that just “works with or serves people”. Majors like Education/Teaching; Social Work; Human Relations; and Foreign Languages possibly could be considered.

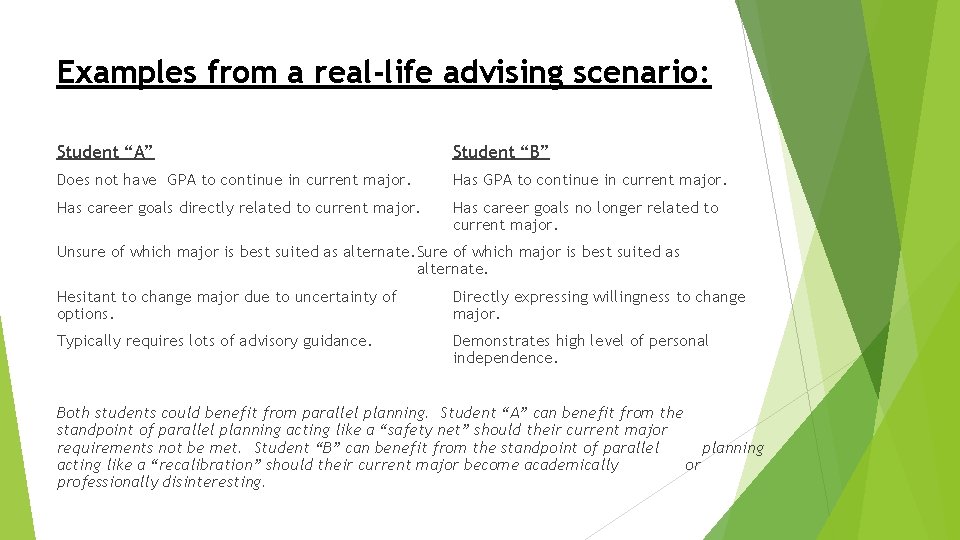

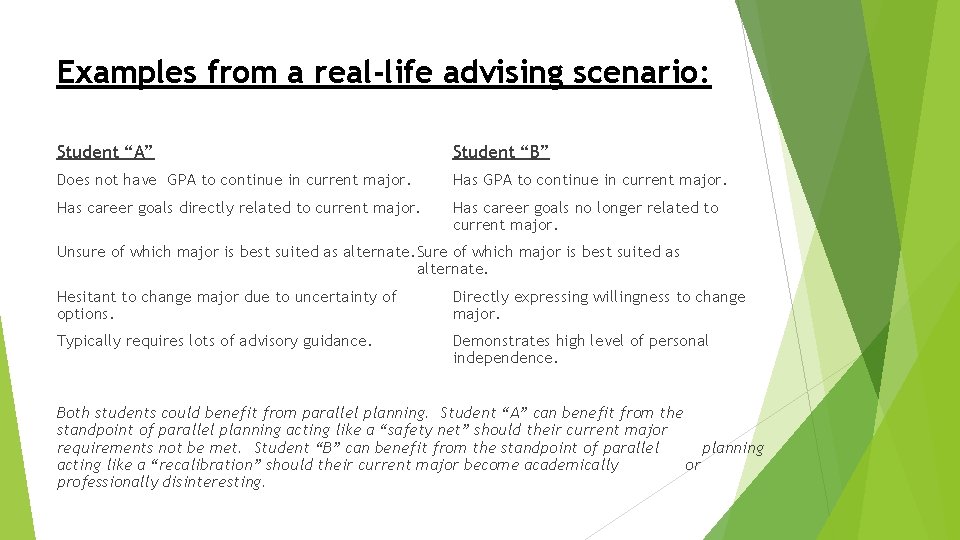

Examples from a real-life advising scenario: Student “A” Student “B” Does not have GPA to continue in current major. Has career goals directly related to current major. Has career goals no longer related to current major. Unsure of which major is best suited as alternate. Sure of which major is best suited as alternate. Hesitant to change major due to uncertainty of options. Directly expressing willingness to change major. Typically requires lots of advisory guidance. Demonstrates high level of personal independence. Both students could benefit from parallel planning. Student “A” can benefit from the standpoint of parallel planning acting like a “safety net” should their current major requirements not be met. Student “B” can benefit from the standpoint of parallel planning acting like a “recalibration” should their current major become academically or professionally disinteresting.

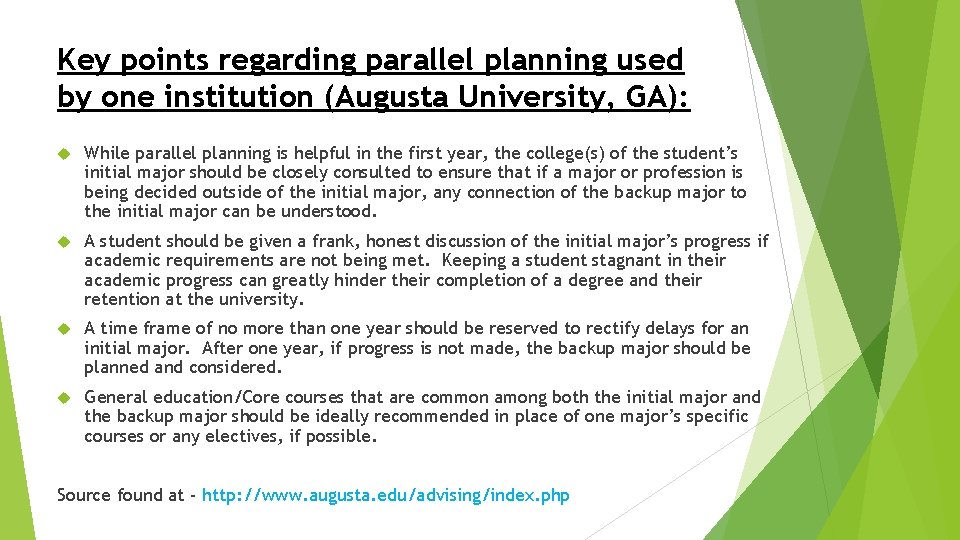

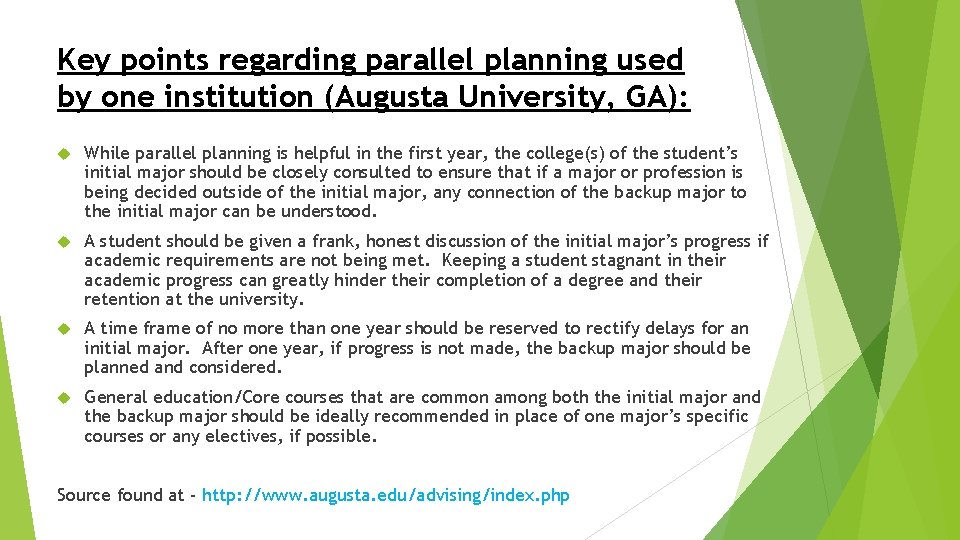

Key points regarding parallel planning used by one institution (Augusta University, GA): While parallel planning is helpful in the first year, the college(s) of the student’s initial major should be closely consulted to ensure that if a major or profession is being decided outside of the initial major, any connection of the backup major to the initial major can be understood. A student should be given a frank, honest discussion of the initial major’s progress if academic requirements are not being met. Keeping a student stagnant in their academic progress can greatly hinder their completion of a degree and their retention at the university. A time frame of no more than one year should be reserved to rectify delays for an initial major. After one year, if progress is not made, the backup major should be planned and considered. General education/Core courses that are common among both the initial major and the backup major should be ideally recommended in place of one major’s specific courses or any electives, if possible. Source found at - http: //www. augusta. edu/advising/index. php

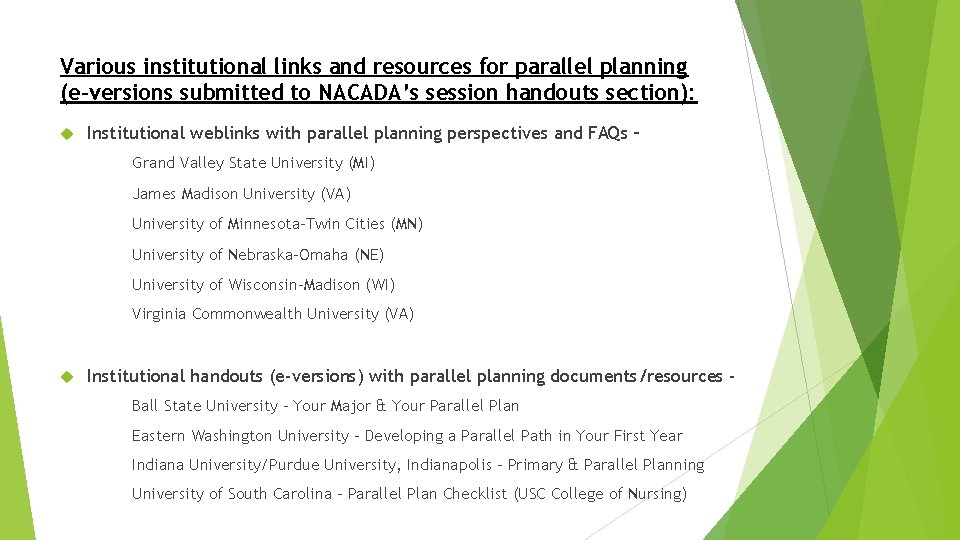

Various institutional links and resources for parallel planning (e-versions submitted to NACADA’s session handouts section): Institutional weblinks with parallel planning perspectives and FAQs – Grand Valley State University (MI) James Madison University (VA) University of Minnesota-Twin Cities (MN) University of Nebraska-Omaha (NE) University of Wisconsin-Madison (WI) Virginia Commonwealth University (VA) Institutional handouts (e-versions) with parallel planning documents/resources Ball State University – Your Major & Your Parallel Plan Eastern Washington University – Developing a Parallel Path in Your First Year Indiana University/Purdue University, Indianapolis – Primary & Parallel Planning University of South Carolina – Parallel Plan Checklist (USC College of Nursing)

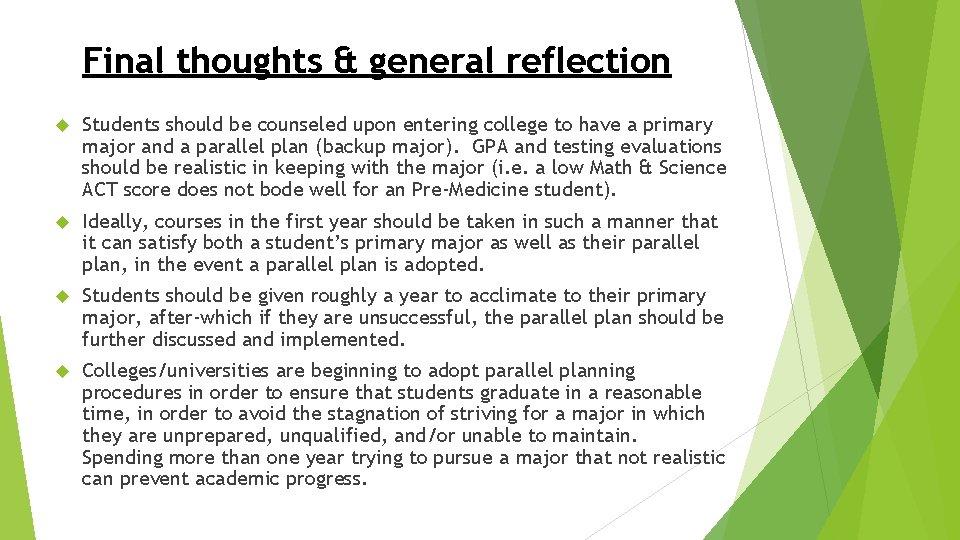

Final thoughts & general reflection Students should be counseled upon entering college to have a primary major and a parallel plan (backup major). GPA and testing evaluations should be realistic in keeping with the major (i. e. a low Math & Science ACT score does not bode well for an Pre-Medicine student). Ideally, courses in the first year should be taken in such a manner that it can satisfy both a student’s primary major as well as their parallel plan, in the event a parallel plan is adopted. Students should be given roughly a year to acclimate to their primary major, after-which if they are unsuccessful, the parallel plan should be further discussed and implemented. Colleges/universities are beginning to adopt parallel planning procedures in order to ensure that students graduate in a reasonable time, in order to avoid the stagnation of striving for a major in which they are unprepared, unqualified, and/or unable to maintain. Spending more than one year trying to pursue a major that not realistic can prevent academic progress.