The Power Threat Meaning Framework PTMFramework Slides Lucy

- Slides: 72

The Power Threat Meaning Framework #PTMFramework Slides © Lucy Johnstone & Mary Boyle (2019)

Learning Outcomes • Understand the core principles of the Power Threat Meaning Framework and how it offers support and validation for nondiagnostic approaches, including culturally-specific perspectives and practices • Demonstration of how the Framework perspective can be used in practice • Learn about applications of the Power Threat Meaning Framework across various settings • Access relevant documents and resources 2

Contributors to the project over a 5 year period Lucy Johnstone, Mary Boyle, John Cromby, Jacqui Dillon, Dave Harper, Peter Kinderman, Eleanor Longden, David Pilgrim, John Read, with editorial/research support from Kate Allsopp Consultancy group of service users/carers Critical reader group to advise on diversity Other expert contributions including examples of good practice

https: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=Hhd. A 3 x. B 63 GE

The Power Threat Meaning Framework • An attempt to outline an alternative to the diagnostic model of distress and unusual experiences • Funded by the Division of Clinical Psychology of the British Psychological Society but not an official DCP or BPS model • A set of ideas and a conceptual resource for everyone to draw on (professionals, service users, researchers, commissioners, the general public etc) • Not a replacement for all current models and practices. It offers a wider overall framework to support and enhance them. . . • . . . as well as suggesting new ways forward • A first stage, subject to ongoing development and evaluation • Has attracted national and international interest, although controversial in some quarters 5

DCP Position Statement on ‘Classification of behaviour and experience in relation to functional psychiatric diagnosis’ (2013) ‘The DCP is of the view that it is timely and appropriate to affirm publicly that the current classification system as outlined in DSM and ICD, in respect of the functional psychiatric diagnoses, has significant conceptual and empirical limitations. Consequently, there is a need for a paradigm shift in relation to the experiences that these diagnoses refer to, towards a conceptual system not based on a ‘disease’ model’ (May 2013) 6

The Power Threat Meaning Framework: Towards the identification of patterns in emotional distress, unusual experiences and troubled or troubling behaviour, as an alternative to functional psychiatric diagnosis • The main document, available online only. • Detailed overview of philosophical and conceptual principles; the roles of social, psychological and biological causal factors; SU/carer consultancy; and the relevant supporting evidence. • Chapter 8: Ways forward: Implications for public health policy; service design and commissioning; access to social care, housing and welfare benefits; therapeutic interventions; the legal system; and research.

The Power Threat Meaning Framework: Overview • The printed version (and online) consist of the Framework itself (Chapter 6 of the main document) Hard copy from membernetworkservices@bps. org. uk • Appendix 1: A guided discussion about the Framework (also available separately) • Appendices 2 -14 Good practice examples of non-diagnostic work within and beyond services • 2 page summary of the PTM Framework which can be adapted for local purposes; FAQs; Appendix 1 Guided Discussion; slides from the launch; videos of the launch talks; more resources to come. • The link takes you to all documents and resources: https: //www. bps. org. uk/news-and-policy/introducing-powerthreat-meaning-framework

The PTM Framework and trauma-informed approaches • Draws on this research (ACEs, neurobiology of stress etc) but also on a much wider range of philosophical, sociological and psychological literature • Non-diagnostic (‘PTSD’, ‘Complex Trauma’ etc. . ) • Prefers ‘adversity’ (less risk of decontextualised shorthand) • Suggests patterns of distress not only related to obvious ‘trauma events’ but also to more insidious factors including inequality, social exclusion, discrimination, devalued identities etc. . • Explicit links to wider institutional and organisational contexts, macro political and socioeconomic structures and ideologies • Importantly, suggests non-diagnostic alternatives for welfare access, commissioning, legal work, research…. etc. .

Moving beyond the ‘DSM mindset’…… Away from medicalisation – assuming that models designed for understanding bodies can be applied to people’s thoughts, feelings and behaviour. Instead, a framework that understands people in their relational, social and political environments…. ……and sees them as people acting and making meanings, within their life circumstances.

There is a lot of new research out there…. but it tends to get stuck at these points ‘Everything causes everything’ ‘Everyone has experienced everything’ ‘Everyone suffers from everything’

The Power Threat Meaning Framework Going beyond non-diagnostic ways of working one to one (such as formulation). . . . to suggest a framework for describing wider evidence-based patterns of distress and unusual experiences. . which help to construct individual/family/group/social narratives, inside or outside services, supported or not by professionals…. . …as well as suggest alternative ways of fulfilling the other functions of diagnosis.

A more effective, evidence-based way of performing the functions that diagnosis claims but fails to do • Summarising the evidence about causal factors in psychological distress and troubled or troubling behavior • Showing how we can group similar types of experience together • Suggesting ways forward and interventions • Providing a basis for research • Providing a basis for administrative decisions such as commissioning, service design, access to services and benefits, legal judgements and so on 13

As well as fulfilling the expected functions of diagnosis, these are the aims of the PTMF: • Recognising that emotional distress and troubled or troubling behaviour are, ultimately, understandable responses to a person’s history and circumstances • Restoring the link between distress and social injustice • Increasing people’s access to power and resources • Creating validating narratives which inform and empower people, groups and communities by restoring these links and meanings • Promoting social action 14

The Power Threat Meaning Framework poses these core questions • 'What has happened to you? ’ (How is Power operating in your life? ) • ‘How did it affect you? ’ (What kind of Threats does this pose? ) • ‘What sense did you make of it? ’ (What is the Meaning of these experiences to you? ) • ‘What did you have to do to survive? ’ (What kinds of Threat Response are you using? )

In one to one clinical, peer support or self help work this then leads to the questions: • What are your strengths? ’ (What access to Power resources do you have? ) • …. . and to integrate all the above: ‘What is your story? ’

• It is convenient to think of it in terms of Power, Threat, Meaning and Threat Response, but in fact the elements are not independent but evolve out of each other. • ‘Power’ implies both ‘Threat’ and ‘Threat Response’, and all of these are shaped by their Meanings. • Our very detailed review of the evidence about Power, Threat, Meaning and Threat Responses forms the basis of a provisional set of broad patterns in distress.

“What has happened to you? ” (How is POWER operating in your life? ) Power is everywhere in human affairs, yet explicit definitions are rare. PTMF defines power as: • The means of obtaining security and advantage • Being able to influence your environment to meet your own needs and interests

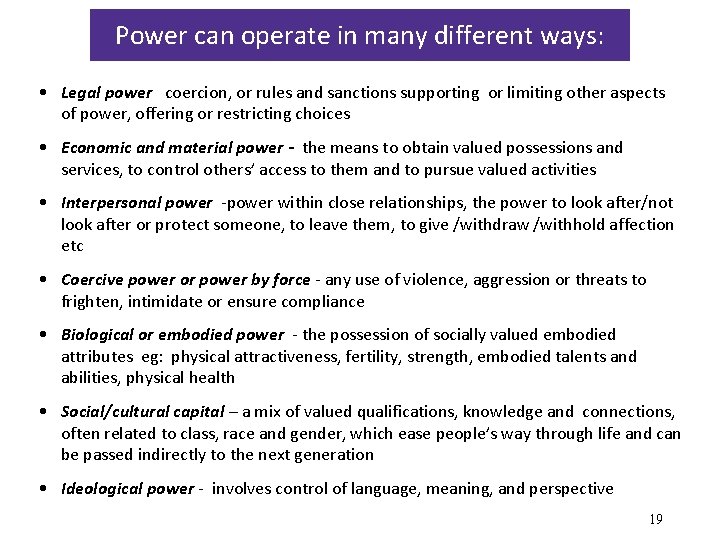

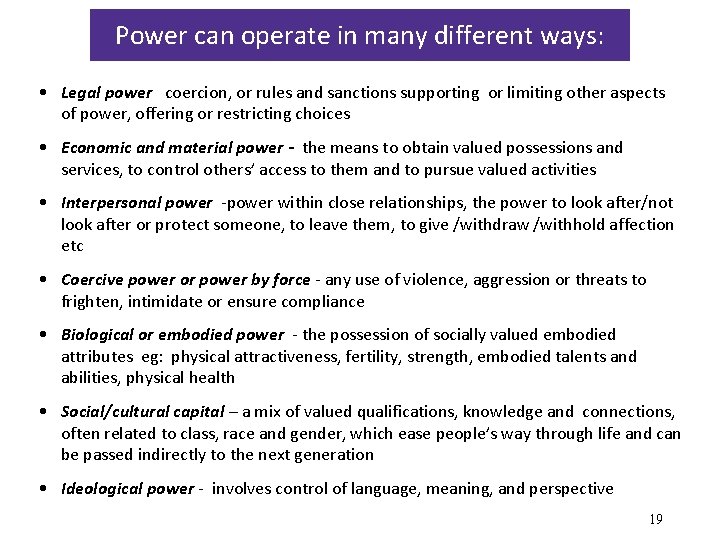

Power can operate in many different ways: • Legal power coercion, or rules and sanctions supporting or limiting other aspects of power, offering or restricting choices • Economic and material power - the means to obtain valued possessions and services, to control others’ access to them and to pursue valued activities • Interpersonal power -power within close relationships, the power to look after/not look after or protect someone, to leave them, to give /withdraw /withhold affection etc • Coercive power or power by force - any use of violence, aggression or threats to frighten, intimidate or ensure compliance • Biological or embodied power - the possession of socially valued embodied attributes eg: physical attractiveness, fertility, strength, embodied talents and abilities, physical health • Social/cultural capital – a mix of valued qualifications, knowledge and connections, often related to class, race and gender, which ease people’s way through life and can be passed indirectly to the next generation • Ideological power - involves control of language, meaning, and perspective 19

Ideological power § Probably the least obvious and least acknowledged form of power § Part of every other form of power § Operates when our thoughts, beliefs and feelings are manipulated, ignored, or disbelieved, and alternative interpretations are offered or imposed In everyday life, it shapes the sense we make of our circumstances. In mental health and criminal justice systems it can: § turn social problems into individual ones § diagnose or define people as ‘bad or mad’ 20

The particular importance of ideological power - power Ideological power over meaning, language and perspective. . . • Many people, especially those in less powerful positions, may be deprived of sound alternative frameworks to make sense of their own and others’ distressing or unusual experiences • This ‘epistemic injustice’ is experienced by groups who lack shared resources to understand their experiences, due to unequal power relations (Miranda Fricker, 2007) • From the PTMF perspective, the imposition of a diagnosis, with no alternatives offered, is an example of epistemic injustice. 21

The particular importance of ideological power - power Power over meaning, language and perspective. . . • The less access you have to conventional or approved forms of power, the more likely you are to adopt socially disturbing or disruptive strategies • Power also operates positively and protectively § friends, partners, family, communities, material resources, social capital, positive identities, education and access to knowledge 22

Some consequences of the negative operation of power. . . • Unpredictability and lack of control over your life • Feeling trapped in damaging environments • Conflict – internal, relationships, social • Negative views and stereotypes about you and/or your social or ethnic group • Repeated exposure to many forms of abuse and violence, along with humiliation, criticism, racism and other forms of discrimination etc

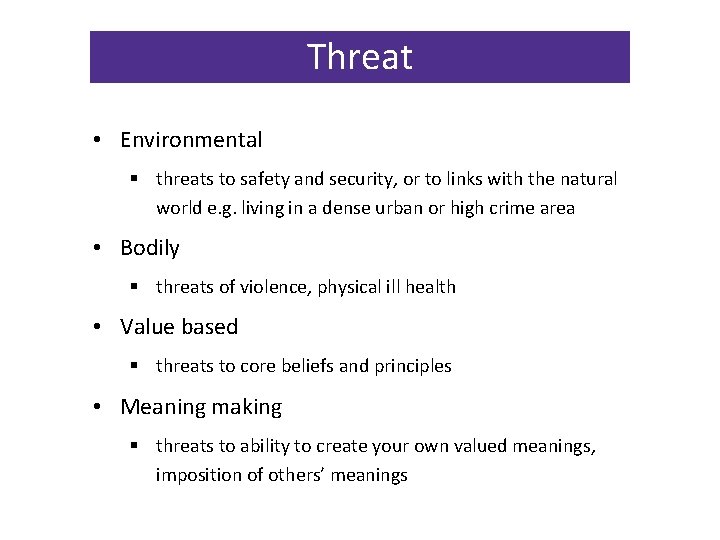

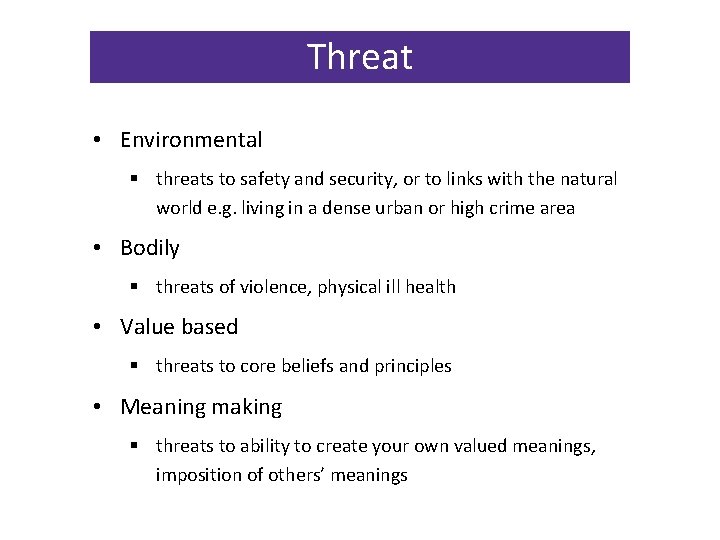

“How did it affect you? ” (What kind of THREATS does it pose? ) • Relationships § threats of rejection, abandonment, isolation • Emotional § overwhelming emotions, loss of control • Social/community § loss of social roles, social status, community links • Economic/material § threats to financial security, housing, meeting basic needs

Threat • Environmental § threats to safety and security, or to links with the natural world e. g. living in a dense urban or high crime area • Bodily § threats of violence, physical ill health • Value based § threats to core beliefs and principles • Meaning making § threats to ability to create your own valued meanings, imposition of others’ meanings

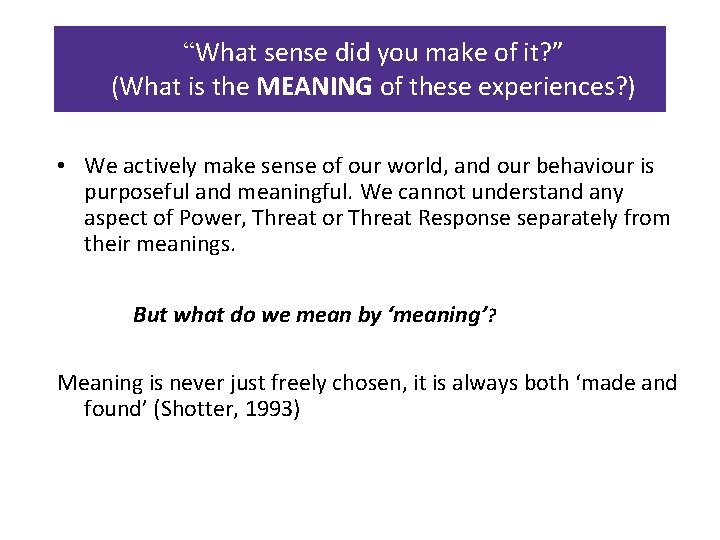

‘ “What sense did you make of it? ” (What is the MEANING of these experiences? ) • We actively make sense of our world, and our behaviour is purposeful and meaningful. We cannot understand any aspect of Power, Threat or Threat Response separately from their meanings. But what do we mean by ‘meaning’? Meaning is never just freely chosen, it is always both ‘made and found’ (Shotter, 1993)

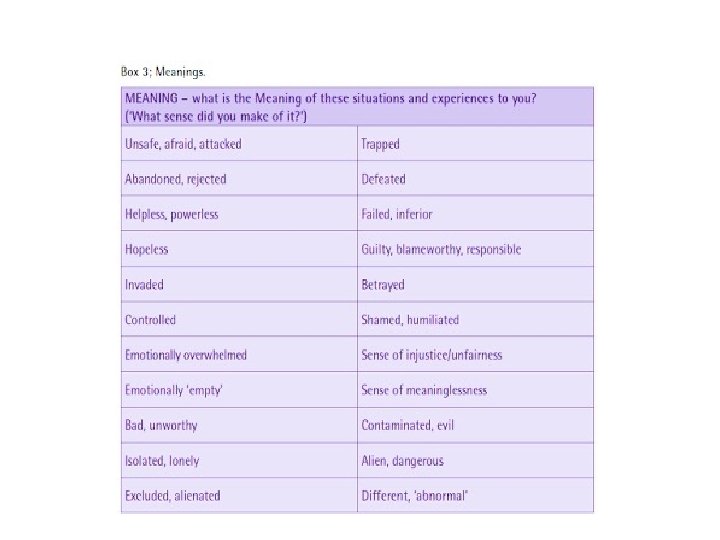

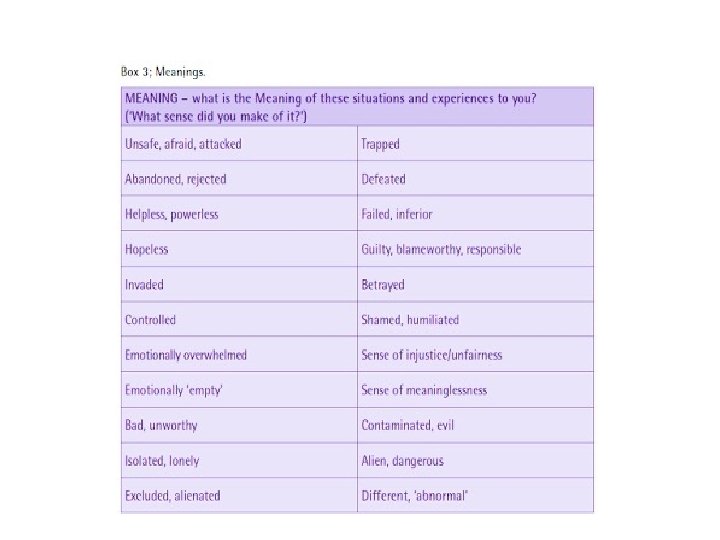

Being powerless is uncomfortable and often highly distressing. Some common feelings ('meanings') that arise from lack of power include:

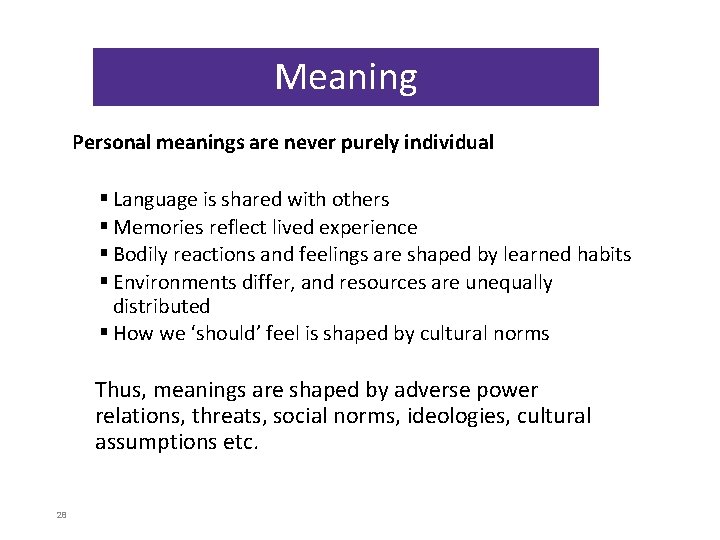

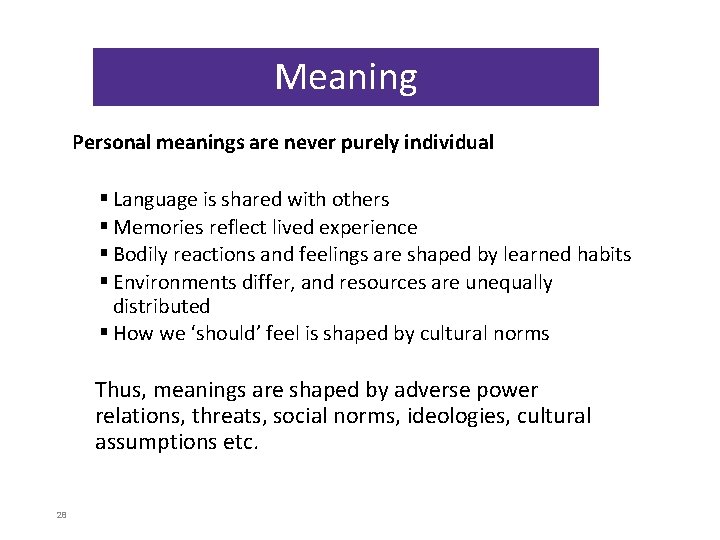

Meaning Personal meanings are never purely individual § Language is shared with others § Memories reflect lived experience § Bodily reactions and feelings are shaped by learned habits § Environments differ, and resources are unequally distributed § How we ‘should’ feel is shaped by cultural norms Thus, meanings are shaped by adverse power relations, threats, social norms, ideologies, cultural assumptions etc. 28

So, we need to see personal meanings within the contexts of: • Wider discourses (common understandings about what it means to be ‘mentally ill’, a ‘good mother’, ‘attractive’, ‘successful’, a ‘happy family’, a refugee, a member of a particular ethnic group, and so on) • Ideological meanings – deeply embedded assumptions about the world that serve certain interests (neoliberalism is a good example. ) 29

“What did you have to do to survive? ’” (What THREAT RESPONSES are you using? ) We have all evolved to be able to respond to threats, by reducing or avoiding them, adapting to or surviving them, and trying to keep safe. These threat responses are biologically-based but are also influenced by our past experiences, family context, gender, class, ethnicity, by social and cultural norms, and by what we can actually do in any given circumstances. They are on a spectrum from automatic (more biologically-based) to more personally and culturally-shaped.

Some examples of threat responses • Preparing to fight, flee, escape, seek safety • Giving up (‘learned helplessness’, apathy, low mood) • Being hypervigilant • Having flashbacks, phobic responses, nightmares • Experiencing rapid changes in mood and emotions • Amnesia/fragmented memory • Hearing voices, dissociating, holding unusual beliefs • Restricting our eating, using alcohol or drugs, self-harm • Denial, avoidance • Overwork, perfectionism 31

Threat responses (survival/coping mechanisms) are often labelled symptoms of ‘mental illness’

Some of these may be seen as ‘normal’ or even desirable (overwork, perfectionism, ruthlessness with colleagues, etc. . ) They are likely to be to some degree culture-specific (selfstarvation in Westernised countries; so-called ‘culture-bound syndromes’. ) Threat responses are there for a reason, and it makes more sense to group them by function – what purpose do they serve? than by ‘symptom. ’ Both the function and the meaning of the response vary over time and across cultures, but there are common themes. 33

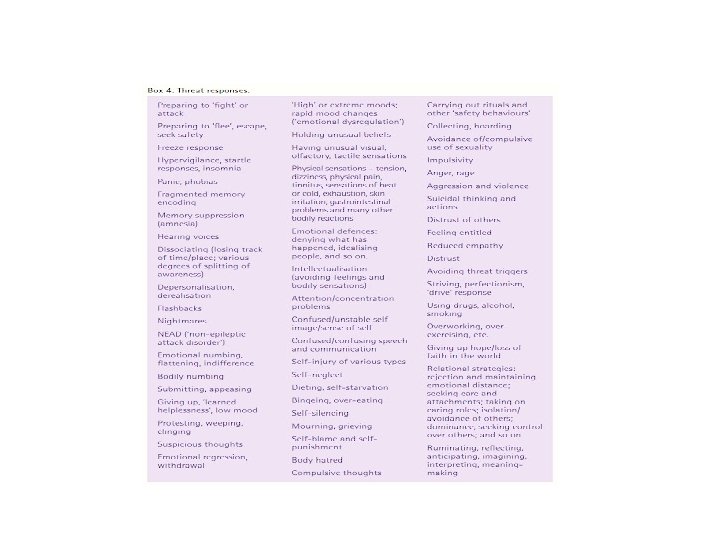

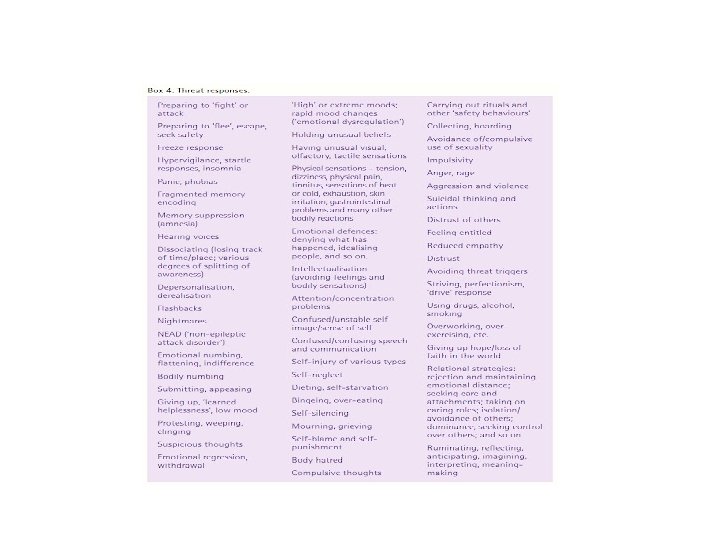

Threat responses grouped by common functions • Regulating overwhelming feelings: (e. g. by dissociation, self -injury, memory fragmentation, bingeing and purging, differential memory encoding, ritualising, intellectualisation, ‘high’ mood, low mood, hearing voices, use of alcohol and drugs, compulsive activity of various kinds, overeating, denial, projection, splitting, somatic sensations, bodily numbing). • Protection against attachment loss, hurt and abandonment: (e. g. by rejection of others, distrust, seeking care and emotional responses, submission, self-blame, interpersonal violence, hoarding, appeasement, selfsilencing, self-punishment). 34

Threat responses grouped by common functions Preserving identity, self-image and self-esteem: (e. g. by grandiosity, unusual beliefs, feeling entitled, perfectionism, striving, dominance, hostility, aggression) Preserving a place within the social group: (e. g. by striving, competitiveness, appeasement, self-silencing, self-blame) Protection from physical danger: (e. g. by hypervigilance, insomnia, flashbacks, nightmares, fight/flight/freeze, suspicious thoughts, isolation, aggression) 35

Restoring the link between Threats and Threat Responses – a main purpose of the Framework Linking Threats to Threat Responses • The Power Threat Meaning Framework shows how we can restore the links between threats and threat responses as an alternative to the diagnostic lens which obscures them. • At one level this is common sense. We all know that people living in poverty are more likely to feel miserable (‘depression’); we recognise that abuse and trauma makes it more likely that people will hear voices (‘psychosis’ or ‘schizophrenia’); and that Indigenous people have many reasons for despair. • But a number of factors combine to conceal these links – from the person and from society as a whole.

• The threat (or operation of Power) may be less obvious because it is subtle, cumulative, and/or socially acceptable. • The threat is often distant in time. • The threats may be so numerous, and the responses so many and varied, that the connections between them are confused and obscured. • There may be an accumulation of apparently minor threats and adversities over a very long period of time • The threat response may take an unusual or extreme form that is less obviously linked to the threat; for example, apparently ‘bizarre’ beliefs, hearing voices, self-harm, self-starvation. 37

• The person in distress may not be aware of the link themselves, since memory loss, dissociation and so on are part of their coping strategies. • The person in distress might have become used to overlooking possible links, because acknowledging them felt dangerous, stigmatising or shaming • Overlooking or ignoring the links may be encouraged by: § Messages about personal blame, weakness, culpability etc. § Messages about personal responsibility, not complaining, being strong etc.

• The use of diagnosis by professionals obscures the link between threats and threat responses, and imposes a narrative of individual ‘illness’ instead • There is widespread resistance to recognising the reality and impact of threats and the negative impacts of power • There are many vested interests (personal, family, professional, organisational, community, business, institutional, economic, political) in disconnecting threats from threat Responses - and thus preserving the diagnostic model.

Questions

General Patterns within the Power Threat Meaning Framework What kind of patterns of distress do we find if we put together the evidence about the influences of Power, Threat, Meaning and associated Threat Responses? Medical diagnosis depends on patterns identified through a medical lens. The PTMF aims to provide an alternative metaframework for identifying patterns or regularities appropriate for emotional distress and troubled or troubling behaviour. The General Patterns are, and always will be, in a state of development. We have suggested the principles on which they need to be based.

General Patterns within the Power Threat Meaning Framework Unlike biological patterns, these regularities are organised by meaning not by biology. The experience of adversity sets up broad, complex, overlapping, meaning-based patterns which are and always will be evolving. A very different kind of causality is implied, within which it will never be possible to make precise cause-effect predictions. The patterns will always reflect and be shaped by specific worldviews, social, historical, political and cultural contexts and ideological meanings.

Patterns of embodied, meaning-based threat responses to the negative operation of power. The General Patterns are described as verbs not nouns, to reflect the fact that they represent active (although not necessarily consciously chosen or controlled) attempts to survive the negative operation of power. They describe what people DO not what they ‘HAVE. ’ They are not a one-to-one replacement for diagnostic clusters, and people will vary in their ‘fit’ with one or more patterns – thus, general patterns will always need tailoring to the person (or couple/family/social group). 43

Evidence-based General Patterns We have provisionally outlined 7 evidence-based General Patterns which cut across: • Diagnostic categories • Specialties (MH, addictions, OA, Child, criminal justice, health) • ‘Normal’ and ‘abnormal’ • People who are psychiatrically labelled and all of us

Seven Provisional General Patterns 1. Identities 2. Surviving rejection, entrapment and invalidation 3. Surviving insecure attachments and adversities as a child/young person 4. Surviving separation and identity confusion 5. Surviving defeat, entrapment, disconnection and loss 6. Surviving social exclusions, shame and coercive power 7. Surviving single threats

In Westernised countries, these patterns draw on struggles with Western norms and standards, such as: • Separating from your family in early adulthood • Competing and achieving in line with social expectations (eg in the labour market; for material goods) • Meet your needs within a nuclear family structure • Fit in with standards about body size, shape and weight • Fit in with expectations about gender identity and gender roles • Avoiding ‘irrational’ experiences – (eg contradicting notions of a unitary self) • As an older adult – cope with loneliness and lack of status • Bring up children to fit in with all the above

General Pattern: Surviving social exclusion, shame and coercive power Within the Power Threat Meaning Framework, this describes someone whose family of origin is likely to have lived in environments characterised by threat, discrimination, material deprivation and social exclusion. This may have included absent fathers, institutional care and/or homelessness. Within this, caregivers are likely to have been struggling with their own histories of adversity, past and present, often by using drugs and alcohol. As a result of all this, the person’s early attachments were often disrupted and insecure, and they may have experienced significant adversities as a child and as an adult, including physical and sexual abuse, bullying, witnessing domestic violence, and harsh or humiliating parenting styles. ‘Disorganised’ attachment styles are common. Individuals tend to use survival strategies of cutting off from their own and others’ emotions, maintaining emotional distance, and remaining highly alert to threat.

Discourses and status comparisons may have imparted a sense of worthlessness, shame and injustice, which may be managed by various forms of violent behaviour. More unequal societies, in which economic inequality increases social competition, allow these dynamics to flourish. This may have a particularly strong impact on disadvantaged men, who have greater incentives than women to compete, achieve and maintain high social status, while being faced with numerous indications of their lack of success and status. Social discourses about gender roles, class and ethnicity shape the way in which the threats are experienced and expressed.

Questions

Patterns and ‘culture’ The Power Threat Meaning framework predicts and allows for the existence of widely varying cultural experiences and expressions of distress without seeing them as bizarre, primitive, less valid, or as exotic variations of the dominant diagnostic or other Western paradigms. Since it is an over-arching framework that is based on universal evolved human capabilities and threat responses, the basic principles of PTM apply across time and across cultures. Within this, open-ended lists of threat responses and functions allow for an indefinite number of locally and historically specific expressions of distress, all shaped by local cultural meanings.

Example of a ‘culture-bound syndrome’ DSM IV ‘Spirit possession’ is sometimes seen as equivalent to the psychiatric concept of ‘psychosis’. One version, ‘cen’, is found in Northern Uganda, where civil war has resulted in widespread brutality and the abduction and forced recruitment of children as soldiers. In this phenomenon, young people report that their identity has been taken over by the malevolent ghost of a dead person. ‘Cen’ has been found to be associated with high levels of war trauma and with abduction, and the spirit was often identified as someone the abductees had been forced to kill. We could understand this within the Power Threat Meaning framework without having to call it ‘schizophrenia’ or ‘psychosis’

In contrast to the Global Mental Health Movement which is currently exporting diagnostic models across the world, the Framework is intended to convey a message of respect for the many different ways people express and heal distress both within the UK and across the globe. Workshops on exploring, comparing and contrasting the PTMF with indigenous understandings in New Zealand Australia are described here: https: //www. madintheuk. com/2019/02/crossing-cultures-with-the-powerthreat-meaning-framework/ https: //www. madintheuk. com/2019/03/crossing-cultures-with-the-powerthreat-meaning-framework-australia/

The PTM Framework and the relevance of: • Histories of colonisation, slavery and intergenerational trauma, and the resulting discrimination, loss of identity, culture, heritage and land • Inseparability of individual from the social group • Relationship to the natural world • Integration of mind, body, spirit, natural world • Indigenous psychologies and research paradigms • Culturally-supported practices, rituals and ceremonies • Community narratives, values, faiths and spiritual beliefs, to support the healing and integration of the social group (Main, p. 216 -217; Overview, p 77 -79. )

The PTM Framework and narrative Story-telling and meaning-making are universal human capacities. The PTMF validates and provides evidence for the central role of narrative of all kinds as an alternative to diagnosis, and as a means of witnessing and healing, both within and beyond services. The evidence-based General Patterns support the construction of particular narratives of any kind So – including but going beyond evidence-based practice and historical truth, in order to value ‘narrative truth’ (Spence, 1982); and whether stories seem to ‘fit’ in a way that ‘makes change conceivable and attainable’ (Schafer, 1980). Recovery as ‘reclaiming our experience in order to take back authorship of our own stories’ (Dillon and May, 2003)

Examples of PTMF translated into practice Clinical Psychology Forum free download: https: //shop. bps. org. uk/publications/clinical-psychology-forum-no-313 january-2018. html Enhancing existing formulation and team formulation work (AMH, OA, LD, autism, youth offending, ‘PD’, etc) § Adding ‘Power’ explicitly to current formulation models § Using the Guided Discussion template for team formulations § Developing a formulation group based on PTMF Pilot study on 2 inpatient wards with potential across a London Trust Peer support groups in UK, USA, New Zealand, Australia Interest also from Ireland, Greece, Denmark, Spain, India, Brazil Guiding services for trafficked women and for refugees Other professions - Art Therapists, Social Workers, Counsellors/Therapists

Training/teaching • Introduced to courses in undergraduate psychology, clinical psychology, forensic psychology, nursing and social work, teacher training • Used in training with prison officers, educational psychologists, teachers • 150 + invited conference/training events since the launch Voluntary organisations • Video using PTMF to explain domestic abuse • Interest from many charities and other non statutory organisations Translations • Spanish. Italian, Danish and Portuguese planned. Criminal justice system • Used in court reports, service planning, groupwork, supervision

Research – informing/supporting the following: • Action Research project in Birmingham • Clinical psychology trainee projects Textbooks • ‘Abnormal psychology: Contrasting perspectives’ Raskin, 2018 • ‘Communication and interpersonal skills’ 4 th edn Grant and Goodman, 2018 • ‘Psychology and Sociology in MH Nursing’ Goodman, 3 rd edition, 2019 • Revised edition of ‘Psychology, mental health and distress’ Cromby, Harper and Reavey, 2013 Crossing cultures • Supporting the challenge to the Global MH movement • Workshops in New Zealand Australia alongside indigenous people www. madintheuk. com

What does this add to a routine formulation? The unhelpful aspects of the dominant narrative of psychiatric diagnosis and its wider context of meta-narratives about science. The contradictions in combining psychiatric diagnostic narratives with psychosocial ones. The role of social discourses, especially those about gender, class, ethnicity and the medicalisation of mental distress, and how these discourses can support the imposition of others’ meanings. The impacts of coercive, legal, and economic power. The nature and impact of power inequalities in psychiatric settings. The prevalence of abuse of interpersonal power within relationships. The role of ideological power as commonly expressed through dominant narratives and assumptions about individualism, achievement, personal responsibility, gender roles, and so on.

What does this add to a routine formulation? The mediating role of biologically-based threat responses. The importance of function over ‘symptom’ or specific problem. The role of power resources in shaping threat responses. Culture-specific meanings and forms of expression. Self-help and social action along with, or instead of, professional intervention. The importance of group and community narratives to support the healing and re-integration of the social group. Recognition of the personal and provisional nature of all narratives and the need for sensitivity, artistry and respect in supporting their development and expression. A meta message that is normalising, not pathologising (either medically or psychologically): ‘You are experiencing a normal, understandable and indeed adaptive reaction to threats and difficulties. Many others in the same circumstances have felt the same. ’

Trying it out…. An exercise Guided discussion for helping to apply these ideas to people’s real lives – inside or outside services. • Either: Use yourself as an example (whether or not you have a MH history) but take care of yourself! • Or: Use someone else as an anonymous example (friend, family member. ) NB Confidentiality Either: Pairing up with someone else Or: Doing it on your own

Trying it out…. An exercise Use the Guided Discussion to think about someone’s story • Read the summary • Divide into groups with each group thinking about Power influences, plus one of either Threat, Meaning, Threat Responses, or Strengths. • Write thoughts on flipchart paper. • Summarise the group view. • Reflections on the process • Update on the person’s story

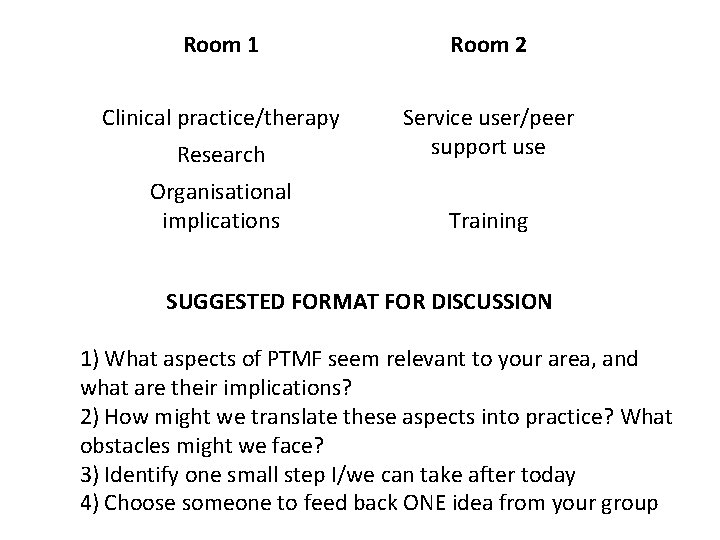

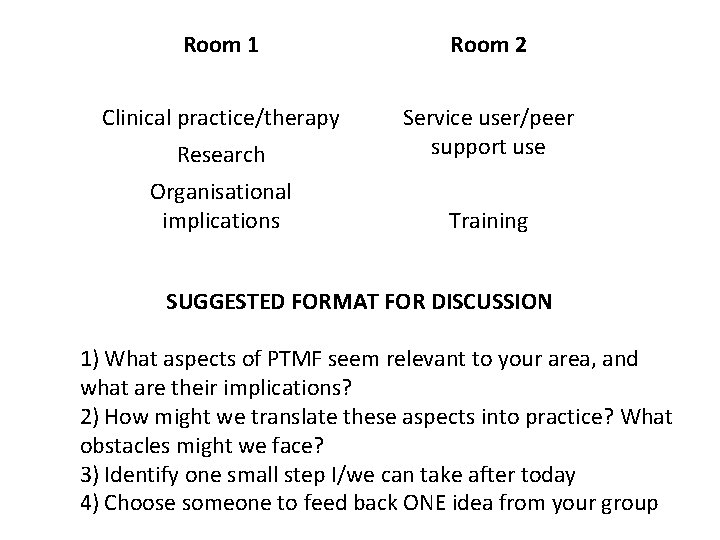

Room 1 Room 2 Clinical practice/therapy Research Service user/peer support use Organisational implications Training SUGGESTED FORMAT FOR DISCUSSION 1) What aspects of PTMF seem relevant to your area, and what are their implications? 2) How might we translate these aspects into practice? What obstacles might we face? 3) Identify one small step I/we can take after today 4) Choose someone to feed back ONE idea from your group

Consultation group of service users/carers The PTM Framework was co-produced with the survivor members of the core team from the first meeting. It draws extensively from survivor literature and has benefited from other SU contributors. In addition, we consulted with a group of 8 service users/survivors and carers. They were sent a brief outline of the Framework and then invited, via a one-to-one discussion, to reflect and give feedback on it from the perspective of their own lives, experiences and mental health difficulties. Their comments were then used to refine the framework further. They were paid for their time.

The consultant group (see Chapter 7 main document for more details) Aiming for a range of backgrounds and experiences: 4 men 4 women Age range 21 - 54 5 White British, 2 African Caribbean, 1 non-British (unspecified for the purposes of the project) A range of diagnoses in childhood and/or adulthood from anxiety to ‘schizophrenia’ Most had not been exposed to ‘critical’ perspectives in any detail, and were not mental health activists or campaigners.

‘ “What has happened to you? ” (How is Power operating in your life? ) ‘The most helpful aspect has been the power, and had this been up for discussion it would have changed the course of what happened…for me’ (E). ‘[The] power part of the framework is the fulcrum of it’ (F). ‘It would have felt like a weight off my shoulders to feel that the person I was talking to was recognising the things… that were predominantly the cause of my problems… somebody hearing me say, ‘I have absolutely had the sharp end of the stick in certain power-related situations ………That would have been an incredibly helpful alternative to what did happen’ (C).

“How did it affect you? ” (What kinds of Threat does this pose? ) ‘Threats’ included relationship traumas, poor housing, violent neighbourhoods, physical disability, welfare systems, racial discrimination and poverty.

“What sense did you make of it? ” (What is the Meaning of these experiences to you? ) ‘Intuitively I always understood my experiences this way. How scared, suspicious and fearful I was made sense to me, I’d experienced various threats, including my first memory, pretty much constantly throughout my life in all the different spheres I existed, and another dramatic threat on the day I started to hear voices…. My voices, constantly threatening to harm me, and berating me as justification for why they would harm me, felt like an expression of the fear I’d spent my life denying I felt, and mirrored the general pattern of threats I’d experienced. ’

Consultants spoke frequently about the damaging impact of having others’ meanings imposed on their feelings and behaviour within mental health services: ‘…absolutely everything I had to say, including that the drugs were making things worse, [staff] made me, and more specifically my brain, the problem, rather than my traumatic experiences’ (F). Consultants saw the processes of meaning-making and permission to speak as being linked, and as offering the potential for avoiding diagnosis, accessing more appropriate intervention, adopting more adaptive coping responses and feeling more positive about oneself.

“What did you have to do to survive? ” (What kinds of Threat Response are you using? ) B stated that it was extremely useful to provide a context for consciously exploring/addressing one’s responses to threat, and what the origins of these might be: ‘…. . dealing with real things that are happening right now, rather than persuading [you that you’re] a bit crazy, take the pill, shut up about it. ’

General Comments Consultant A approved of the simplicity of the framework (‘it is simple yet clever at the same time’), and how three discrete yet overlapping constructs could be used to capture ‘many different strands’ of one’s experience. B felt the framework made an ‘enormous’ amount of sense and was ‘very strong and useful…and really, really helpful’, particularly the threat component. B also approved of the way that the framework facilitated open discussion of ‘unmentionable’ events and could help people feel a sense of permission to disclose: ‘that it’s okay to talk about these things, it’s okay to tell people about them…to name them. ’

Strengths of the PTM Framework • preventing or making more difficult the imposition of others’ meanings • giving ‘permission’ to speak about certain life experiences • encouraging more positive and helpful coping responses • partly as a result of this, potentially fostering a quicker ‘recovery’ If the Framework had been offered at first contact with services: ‘I can guess I would have felt stronger afterwards. To be able to see a professional… Ask me, genuinely, about any problems I’d had, power related situations or threat related situations… [and] telling me ‘these are absolutely valid things to be hugely unhappy about and very valid things to have suffered because of’ (C).

Queries and aspects to improve • Language and conceptual complexity • Possible additional threat responses • Risk of interpreting as imposing another professional model • Need for wider cultural change if the PTM Framework is to have an impact. Consultant C pointed out that the PTM Framework could be problematic for people who might prefer a diagnosis which did not explore their personal history, and seemed to provide clearcut answers rather than this more complex picture.