The Normalization of College Drinking Behaviors How Social

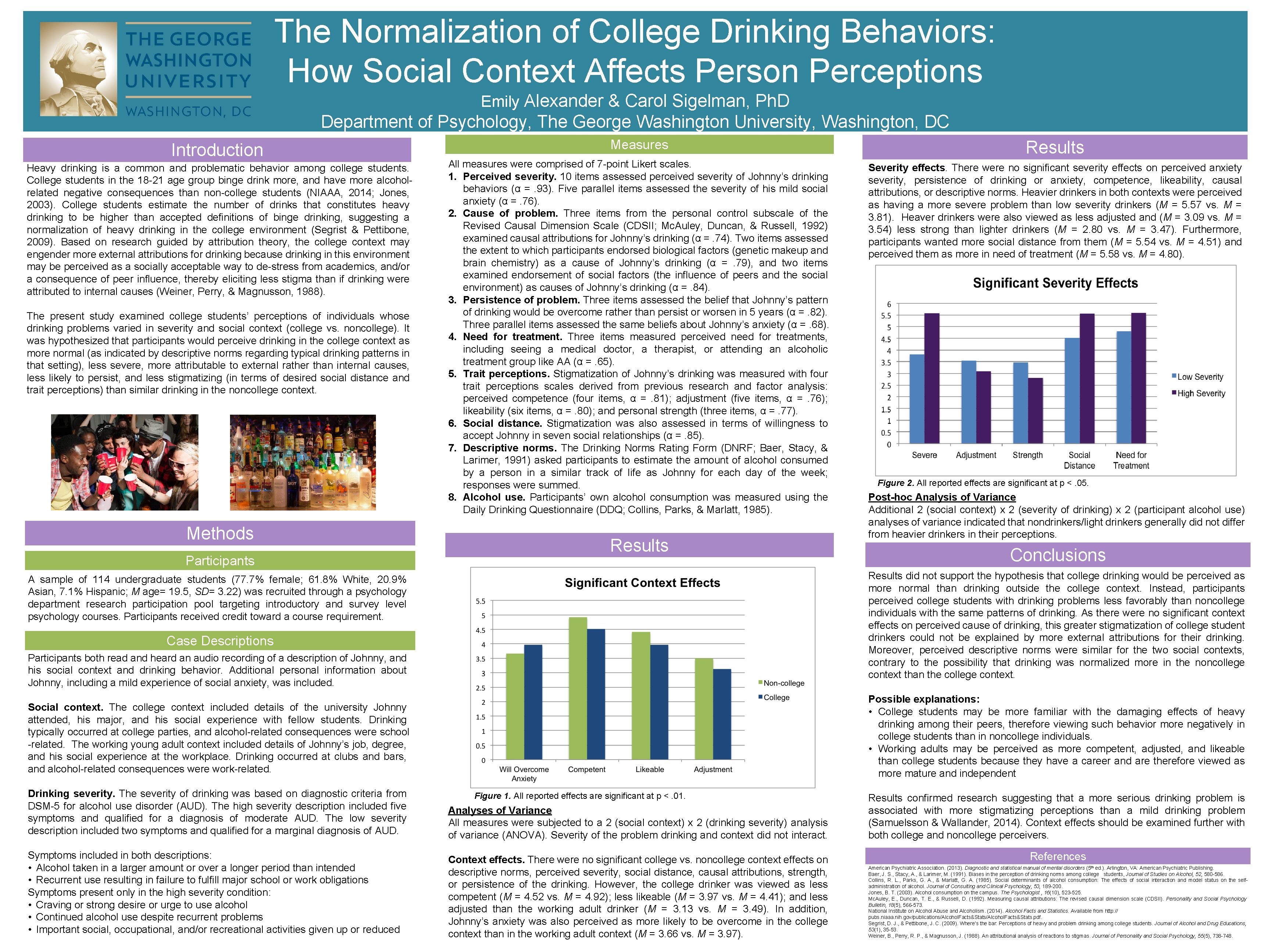

The Normalization of College Drinking Behaviors: How Social Context Affects Person Perceptions Emily Alexander & Carol Sigelman, Ph. D Department of Psychology, The George Washington University, Washington, DC Introduction Heavy drinking is a common and problematic behavior among college students. College students in the 18 -21 age group binge drink more, and have more alcoholrelated negative consequences than non-college students (NIAAA, 2014; Jones, 2003). College students estimate the number of drinks that constitutes heavy drinking to be higher than accepted definitions of binge drinking, suggesting a normalization of heavy drinking in the college environment (Segrist & Pettibone, 2009). Based on research guided by attribution theory, the college context may engender more external attributions for drinking because drinking in this environment may be perceived as a socially acceptable way to de-stress from academics, and/or a consequence of peer influence, thereby eliciting less stigma than if drinking were attributed to internal causes (Weiner, Perry, & Magnusson, 1988). The present study examined college students’ perceptions of individuals whose drinking problems varied in severity and social context (college vs. noncollege). It was hypothesized that participants would perceive drinking in the college context as more normal (as indicated by descriptive norms regarding typical drinking patterns in that setting), less severe, more attributable to external rather than internal causes, less likely to persist, and less stigmatizing (in terms of desired social distance and trait perceptions) than similar drinking in the noncollege context. Methods Participants Measures Results All measures were comprised of 7 -point Likert scales. 1. Perceived severity. 10 items assessed perceived severity of Johnny’s drinking behaviors (α =. 93). Five parallel items assessed the severity of his mild social anxiety (α =. 76). 2. Cause of problem. Three items from the personal control subscale of the Revised Causal Dimension Scale (CDSII; Mc. Auley, Duncan, & Russell, 1992) examined causal attributions for Johnny’s drinking (α =. 74). Two items assessed the extent to which participants endorsed biological factors (genetic makeup and brain chemistry) as a cause of Johnny’s drinking (α =. 79), and two items examined endorsement of social factors (the influence of peers and the social environment) as causes of Johnny’s drinking (α =. 84). 3. Persistence of problem. Three items assessed the belief that Johnny’s pattern of drinking would be overcome rather than persist or worsen in 5 years (α =. 82). Three parallel items assessed the same beliefs about Johnny’s anxiety (α =. 68). 4. Need for treatment. Three items measured perceived need for treatments, including seeing a medical doctor, a therapist, or attending an alcoholic treatment group like AA (α =. 65). 5. Trait perceptions. Stigmatization of Johnny’s drinking was measured with four trait perceptions scales derived from previous research and factor analysis: perceived competence (four items, α =. 81); adjustment (five items, α =. 76); likeability (six items, α =. 80); and personal strength (three items, α =. 77). 6. Social distance. Stigmatization was also assessed in terms of willingness to accept Johnny in seven social relationships (α =. 85). 7. Descriptive norms. The Drinking Norms Rating Form (DNRF; Baer, Stacy, & Larimer, 1991) asked participants to estimate the amount of alcohol consumed by a person in a similar track of life as Johnny for each day of the week; responses were summed. 8. Alcohol use. Participants’ own alcohol consumption was measured using the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ; Collins, Parks, & Marlatt, 1985). Severity effects. There were no significant severity effects on perceived anxiety severity, persistence of drinking or anxiety, competence, likeability, causal attributions, or descriptive norms. Heavier drinkers in both contexts were perceived as having a more severe problem than low severity drinkers (M = 5. 57 vs. M = 3. 81). Heaver drinkers were also viewed as less adjusted and (M = 3. 09 vs. M = 3. 54) less strong than lighter drinkers (M = 2. 80 vs. M = 3. 47). Furthermore, participants wanted more social distance from them (M = 5. 54 vs. M = 4. 51) and perceived them as more in need of treatment (M = 5. 58 vs. M = 4. 80). Results Figure 2. All reported effects are significant at p <. 05. Post-hoc Analysis of Variance Additional 2 (social context) x 2 (severity of drinking) x 2 (participant alcohol use) analyses of variance indicated that nondrinkers/light drinkers generally did not differ from heavier drinkers in their perceptions. Conclusions Results did not support the hypothesis that college drinking would be perceived as more normal than drinking outside the college context. Instead, participants perceived college students with drinking problems less favorably than noncollege individuals with the same patterns of drinking. As there were no significant context effects on perceived cause of drinking, this greater stigmatization of college student drinkers could not be explained by more external attributions for their drinking. Moreover, perceived descriptive norms were similar for the two social contexts, contrary to the possibility that drinking was normalized more in the noncollege context than the college context. A sample of 114 undergraduate students (77. 7% female; 61. 8% White, 20. 9% Asian, 7. 1% Hispanic; M age= 19. 5, SD= 3. 22) was recruited through a psychology department research participation pool targeting introductory and survey level psychology courses. Participants received credit toward a course requirement. Case Descriptions Participants both read and heard an audio recording of a description of Johnny, and his social context and drinking behavior. Additional personal information about Johnny, including a mild experience of social anxiety, was included. Possible explanations: • College students may be more familiar with the damaging effects of heavy drinking among their peers, therefore viewing such behavior more negatively in college students than in noncollege individuals. • Working adults may be perceived as more competent, adjusted, and likeable than college students because they have a career and are therefore viewed as more mature and independent Social context. The college context included details of the university Johnny attended, his major, and his social experience with fellow students. Drinking typically occurred at college parties, and alcohol-related consequences were school -related. The working young adult context included details of Johnny’s job, degree, and his social experience at the workplace. Drinking occurred at clubs and bars, and alcohol-related consequences were work-related. Drinking severity. The severity of drinking was based on diagnostic criteria from DSM-5 for alcohol use disorder (AUD). The high severity description included five symptoms and qualified for a diagnosis of moderate AUD. The low severity description included two symptoms and qualified for a marginal diagnosis of AUD. Analyses of Variance All measures were subjected to a 2 (social context) x 2 (drinking severity) analysis of variance (ANOVA). Severity of the problem drinking and context did not interact. Symptoms included in both descriptions: • Alcohol taken in a larger amount or over a longer period than intended • Recurrent use resulting in failure to fulfill major school or work obligations Symptoms present only in the high severity condition: • Craving or strong desire or urge to use alcohol • Continued alcohol use despite recurrent problems • Important social, occupational, and/or recreational activities given up or reduced Context effects. There were no significant college vs. noncollege context effects on descriptive norms, perceived severity, social distance, causal attributions, strength, or persistence of the drinking. However, the college drinker was viewed as less competent (M = 4. 52 vs. M = 4. 92); less likeable (M = 3. 97 vs. M = 4. 41); and less adjusted than the working adult drinker (M = 3. 13 vs. M = 3. 49). In addition, Johnny’s anxiety was also perceived as more likely to be overcome in the college context than in the working adult context (M = 3. 66 vs. M = 3. 97). Figure 1. All reported effects are significant at p <. 01. Results confirmed research suggesting that a more serious drinking problem is associated with more stigmatizing perceptions than a mild drinking problem (Samuelsson & Wallander, 2014). Context effects should be examined further with both college and noncollege perceivers. References American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5 th ed. ). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. Baer, J. S. , Stacy, A. , & Larimer, M. (1991). Biases in the perception of drinking norms among college students, Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 52, 580 -586. Collins, R. L. , Parks, G. A. , & Marlatt, G. A. (1985). Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the selfadministration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 53, 189 -200. Jones, B. T. (2003). Alcohol consumption on the campus. The Psychologist , 16(10), 523 -525. Mc. Auley, E. , Duncan, T. E. , & Russell, D. (1992). Measuring causal attributions: The revised causal dimension scale (CDSII). Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 18(5), 566 -573. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. (2014). Alcohol Facts and Statistics. Available from http: // pubs. niaaa. nih. gov/publications/Alcohol. Facts&Stats. pdf. Segrist, D. J. , & Pettibone, J. C. (2009). Where’s the bar: Perceptions of heavy and problem drinking among college students. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Educations, 53(1), 35 -53. Weiner, B. , Perry, R. P. , & Magnusson, J. (1988). An attributional analysis of reactions to stigmas. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 55(5), 738 -748.

- Slides: 1