The KnowledgeRich School Project the Curriculum Design Coherence

- Slides: 1

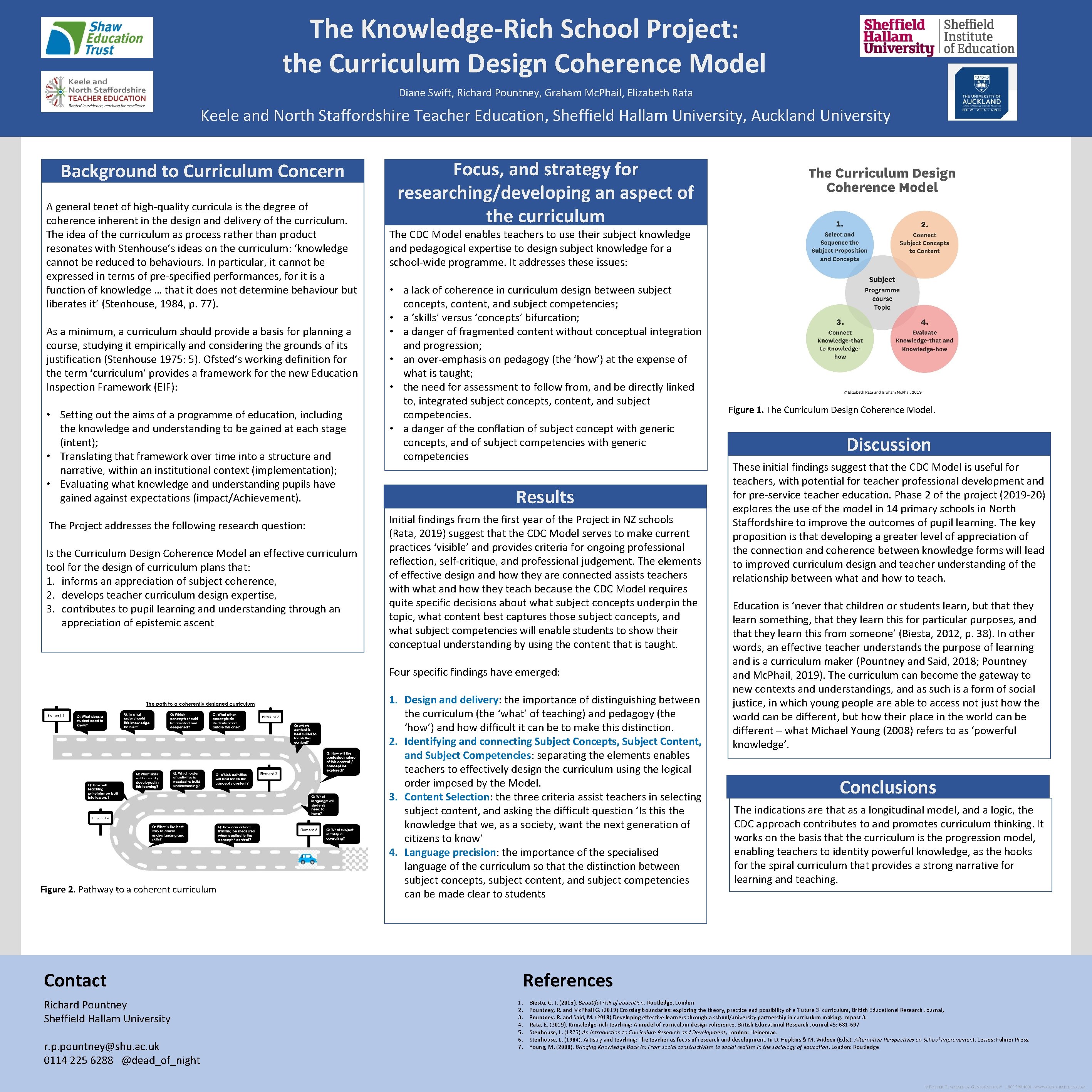

The Knowledge-Rich School Project: the Curriculum Design Coherence Model Diane Swift, Richard Pountney, Graham Mc. Phail, Elizabeth Rata Keele and North Staffordshire Teacher Education, Sheffield Hallam University, Auckland University Background to Curriculum Concern A general tenet of high‐quality curricula is the degree of coherence inherent in the design and delivery of the curriculum. The idea of the curriculum as process rather than product resonates with Stenhouse’s ideas on the curriculum: ‘knowledge cannot be reduced to behaviours. In particular, it cannot be expressed in terms of pre‐specified performances, for it is a function of knowledge … that it does not determine behaviour but liberates it’ (Stenhouse, 1984, p. 77). As a minimum, a curriculum should provide a basis for planning a course, studying it empirically and considering the grounds of its justification (Stenhouse 1975: 5). Ofsted’s working definition for the term ‘curriculum’ provides a framework for the new Education Inspection Framework (EIF): • Setting out the aims of a programme of education, including the knowledge and understanding to be gained at each stage (intent); • Translating that framework over time into a structure and narrative, within an institutional context (implementation); • Evaluating what knowledge and understanding pupils have gained against expectations (impact/Achievement). The Project addresses the following research question: Is the Curriculum Design Coherence Model an effective curriculum tool for the design of curriculum plans that: 1. informs an appreciation of subject coherence, 2. develops teacher curriculum design expertise, 3. contributes to pupil learning and understanding through an appreciation of epistemic ascent Focus, and strategy for researching/developing an aspect of the curriculum The CDC Model enables teachers to use their subject knowledge and pedagogical expertise to design subject knowledge for a school‐wide programme. It addresses these issues: • a lack of coherence in curriculum design between subject concepts, content, and subject competencies; • a ‘skills’ versus ‘concepts’ bifurcation; • a danger of fragmented content without conceptual integration and progression; • an over‐emphasis on pedagogy (the ‘how’) at the expense of what is taught; • the need for assessment to follow from, and be directly linked to, integrated subject concepts, content, and subject competencies. • a danger of the conflation of subject concept with generic concepts, and of subject competencies with generic competencies Results Initial findings from the first year of the Project in NZ schools (Rata, 2019) suggest that the CDC Model serves to make current practices ‘visible’ and provides criteria for ongoing professional reflection, self‐critique, and professional judgement. The elements of effective design and how they are connected assists teachers with what and how they teach because the CDC Model requires quite specific decisions about what subject concepts underpin the topic, what content best captures those subject concepts, and what subject competencies will enable students to show their conceptual understanding by using the content that is taught. Four specific findings have emerged: Figure 2. Pathway to a coherent curriculum Contact Richard Pountney Sheffield Hallam University r. p. pountney@shu. ac. uk 0114 225 6288 @dead_of_night 1. Design and delivery: the importance of distinguishing between the curriculum (the ‘what’ of teaching) and pedagogy (the ‘how’) and how difficult it can be to make this distinction. 2. Identifying and connecting Subject Concepts, Subject Content, and Subject Competencies: separating the elements enables teachers to effectively design the curriculum using the logical order imposed by the Model. 3. Content Selection: the three criteria assist teachers in selecting subject content, and asking the difficult question ‘Is this the knowledge that we, as a society, want the next generation of citizens to know’ 4. Language precision: the importance of the specialised language of the curriculum so that the distinction between subject concepts, subject content, and subject competencies can be made clear to students Figure 1. The Curriculum Design Coherence Model. Discussion These initial findings suggest that the CDC Model is useful for teachers, with potential for teacher professional development and for pre‐service teacher education. Phase 2 of the project (2019‐ 20) explores the use of the model in 14 primary schools in North Staffordshire to improve the outcomes of pupil learning. The key proposition is that developing a greater level of appreciation of the connection and coherence between knowledge forms will lead to improved curriculum design and teacher understanding of the relationship between what and how to teach. Education is ‘never that children or students learn, but that they learn something, that they learn this for particular purposes, and that they learn this from someone’ (Biesta, 2012, p. 38). In other words, an effective teacher understands the purpose of learning and is a curriculum maker (Pountney and Said, 2018; Pountney and Mc. Phail, 2019). The curriculum can become the gateway to new contexts and understandings, and as such is a form of social justice, in which young people are able to access not just how the world can be different, but how their place in the world can be different – what Michael Young (2008) refers to as ‘powerful knowledge’. Conclusions The indications are that as a longitudinal model, and a logic, the CDC approach contributes to and promotes curriculum thinking. It works on the basis that the curriculum is the progression model, enabling teachers to identity powerful knowledge, as the hooks for the spiral curriculum that provides a strong narrative for learning and teaching. References 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. Biesta, G. J. (2015). Beautiful risk of education. Routledge, London Pountney, R. and Mc. Phail G. (2019) Crossing boundaries: exploring theory, practice and possibility of a ‘Future 3’ curriculum, British Educational Research Journal, Pountney, R. and Said, M. (2018) Developing effective learners through a school/university partnership in curriculum making. Impact 3. Rata, E. (2019). Knowledge‐rich teaching: A model of curriculum design coherence. British Educational Research Journal. 45: 681‐ 697 Stenhouse, L. (1975) An introduction to Curriculum Research and Development, London: Heineman. Stenhouse, L. (1984). Artistry and teaching: The teacher as focus of research and development. In D. Hopkins & M. Wideen (Eds. ), Alternative Perspectives on School Improvement. Lewes: Falmer Press. Young, M. (2008). Bringing Knowledge Back In: From social constructivism to social realism in the sociology of education. London: Routledge