THE INFLUENCE OF THE NaCa EXCHANGER DURING SHORTTERM

- Slides: 1

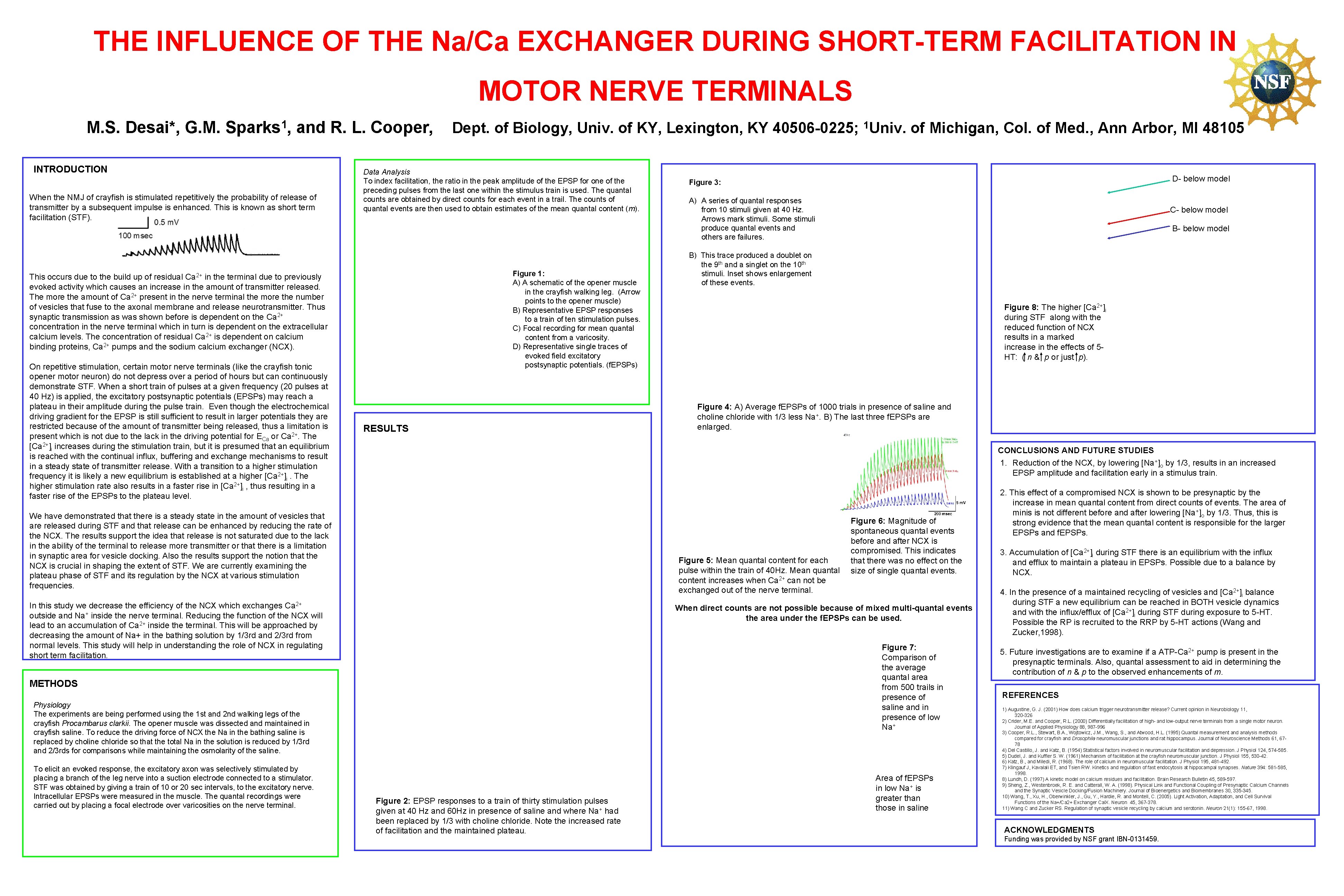

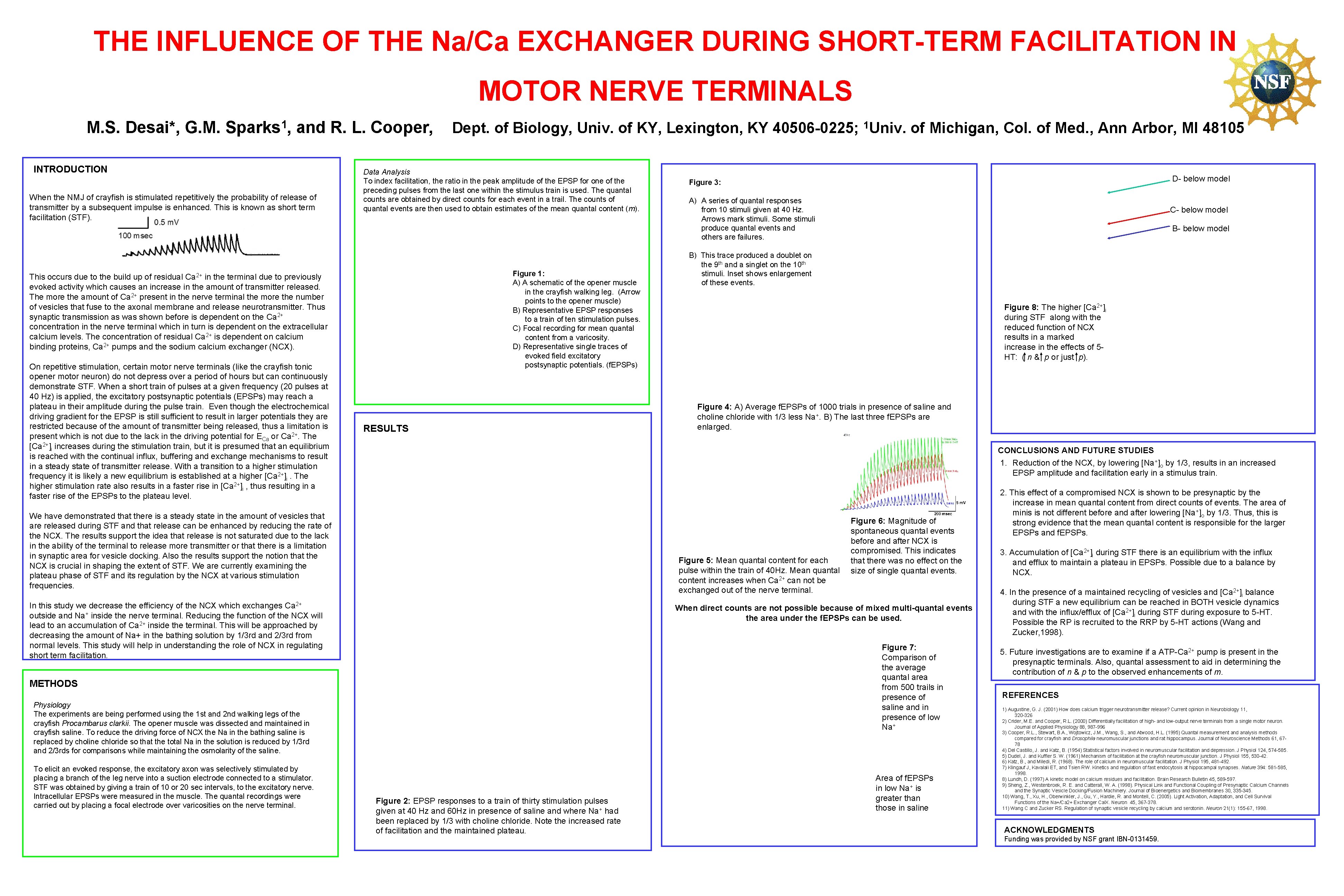

THE INFLUENCE OF THE Na/Ca EXCHANGER DURING SHORT-TERM FACILITATION IN MOTOR NERVE TERMINALS M. S. Desai*, G. M. 1 Sparks , and R. L. Cooper, INTRODUCTION When the NMJ of crayfish is stimulated repetitively the probability of release of transmitter by a subsequent impulse is enhanced. This is known as short term facilitation (STF). Data Analysis To index facilitation, the ratio in the peak amplitude of the EPSP for one of the preceding pulses from the last one within the stimulus train is used. The quantal counts are obtained by direct counts for each event in a trail. The counts of quantal events are then used to obtain estimates of the mean quantal content (m). Figure 1: A) A schematic of the opener muscle in the crayfish walking leg. (Arrow points to the opener muscle) B) Representative EPSP responses to a train of ten stimulation pulses. C) Focal recording for mean quantal content from a varicosity. D) Representative single traces of evoked field excitatory postsynaptic potentials. (f. EPSPs) This occurs due to the build up of residual Ca 2+ in the terminal due to previously evoked activity which causes an increase in the amount of transmitter released. The more the amount of Ca 2+ present in the nerve terminal the more the number of vesicles that fuse to the axonal membrane and release neurotransmitter. Thus synaptic transmission as was shown before is dependent on the Ca 2+ concentration in the nerve terminal which in turn is dependent on the extracellular calcium levels. The concentration of residual Ca 2+ is dependent on calcium binding proteins, Ca 2+ pumps and the sodium calcium exchanger (NCX). On repetitive stimulation, certain motor nerve terminals (like the crayfish tonic opener motor neuron) do not depress over a period of hours but can continuously demonstrate STF. When a short train of pulses at a given frequency (20 pulses at 40 Hz) is applied, the excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs) may reach a plateau in their amplitude during the pulse train. Even though the electrochemical driving gradient for the EPSP is still sufficient to result in larger potentials they are restricted because of the amount of transmitter being released, thus a limitation is present which is not due to the lack in the driving potential for ECa or Ca 2+. The [Ca 2+]i increases during the stimulation train, but it is presumed that an equilibrium is reached with the continual influx, buffering and exchange mechanisms to result in a steady state of transmitter release. With a transition to a higher stimulation frequency it is likely a new equilibrium is established at a higher [Ca 2+]i. The higher stimulation rate also results in a faster rise in [Ca 2+]i , thus resulting in a faster rise of the EPSPs to the plateau level. Dept. of Biology, Univ. of KY, Lexington, KY 40506 -0225; RESULTS of Michigan, Col. of Med. , Ann Arbor, MI 48105 D- below model Figure 3: A) A series of quantal responses from 10 stimuli given at 40 Hz. Arrows mark stimuli. Some stimuli produce quantal events and others are failures. C- below model B) This trace produced a doublet on the 9 th and a singlet on the 10 th stimuli. Inset shows enlargement of these events. Figure 8: The higher [Ca 2+]i during STF along with the reduced function of NCX results in a marked increase in the effects of 5 HT: ( n & p or just p). Figure 4: A) Average f. EPSPs of 1000 trials in presence of saline and choline chloride with 1/3 less Na+. B) The last three f. EPSPs are enlarged. CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE STUDIES 1. Reduction of the NCX, by lowering [Na+]o by 1/3, results in an increased EPSP amplitude and facilitation early in a stimulus train. We have demonstrated that there is a steady state in the amount of vesicles that are released during STF and that release can be enhanced by reducing the rate of the NCX. The results support the idea that release is not saturated due to the lack in the ability of the terminal to release more transmitter or that there is a limitation in synaptic area for vesicle docking. Also the results support the notion that the NCX is crucial in shaping the extent of STF. We are currently examining the plateau phase of STF and its regulation by the NCX at various stimulation frequencies. Figure 5: Mean quantal content for each pulse within the train of 40 Hz. Mean quantal content increases when Ca 2+ can not be exchanged out of the nerve terminal. In this study we decrease the efficiency of the NCX which exchanges Ca 2+ outside and Na+ inside the nerve terminal. Reducing the function of the NCX will lead to an accumulation of Ca 2+ inside the terminal. This will be approached by decreasing the amount of Na+ in the bathing solution by 1/3 rd and 2/3 rd from normal levels. This study will help in understanding the role of NCX in regulating short term facilitation. Figure 6: Magnitude of spontaneous quantal events before and after NCX is compromised. This indicates that there was no effect on the size of single quantal events. When direct counts are not possible because of mixed multi-quantal events the area under the f. EPSPs can be used. Figure 7: Comparison of the average quantal area from 500 trails in presence of saline and in presence of low Na+ METHODS Physiology The experiments are being performed using the 1 st and 2 nd walking legs of the crayfish Procambarus clarkii. The opener muscle was dissected and maintained in crayfish saline. To reduce the driving force of NCX the Na in the bathing saline is replaced by choline chloride so that the total Na in the solution is reduced by 1/3 rd and 2/3 rds for comparisons while maintaining the osmolarity of the saline. To elicit an evoked response, the excitatory axon was selectively stimulated by placing a branch of the leg nerve into a suction electrode connected to a stimulator. STF was obtained by giving a train of 10 or 20 sec intervals, to the excitatory nerve. Intracellular EPSPs were measured in the muscle. The quantal recordings were carried out by placing a focal electrode over varicosities on the nerve terminal. 1 Univ. Figure 2: EPSP responses to a train of thirty stimulation pulses given at 40 Hz and 60 Hz in presence of saline and where Na+ had been replaced by 1/3 with choline chloride. Note the increased rate of facilitation and the maintained plateau. Area of f. EPSPs in low Na+ is greater than those in saline 2. This effect of a compromised NCX is shown to be presynaptic by the increase in mean quantal content from direct counts of events. The area of minis is not different before and after lowering [Na+]o by 1/3. Thus, this is strong evidence that the mean quantal content is responsible for the larger EPSPs and f. EPSPs. 3. Accumulation of [Ca 2+]i during STF there is an equilibrium with the influx and efflux to maintain a plateau in EPSPs. Possible due to a balance by NCX. 4. In the presence of a maintained recycling of vesicles and [Ca 2+]i balance during STF a new equilibrium can be reached in BOTH vesicle dynamics and with the influx/efflux of [Ca 2+]i during STF during exposure to 5 -HT. Possible the RP is recruited to the RRP by 5 -HT actions (Wang and Zucker, 1998). 5. Future investigations are to examine if a ATP-Ca 2+ pump is present in the presynaptic terminals. Also, quantal assessment to aid in determining the contribution of n & p to the observed enhancements of m. REFERENCES 1) Augustine, G. J. (2001) How does calcium trigger neurotransmitter release? Current opinion in Neurobiology 11, 320 -326 2) Crider, M. E. and Cooper, R. L. (2000) Differentially facilitation of high- and low-output nerve terminals from a single motor neuron. Journal of Applied Physiology 88, 987 -996 3) Cooper, R. L. , Stewart, B. A. , Wojtowicz, J. M. , Wang, S. , and Atwood, H. L. (1995) Quantal measurement and analysis methods compared for crayfish and Drosophila neuromuscular junctions and rat hippocampus. Journal of Neuroscience Methods 61, 6778 4) Del Castillo, J. and Katz, B. (1954) Statistical factors involved in neuromuscular facilitation and depression. J Physiol 124, 574 -585. 5) Dudel, J. and Kuffler S. W. (1961) Mechanism of facilitation at the crayfish neuromuscular junction. J Physiol 155, 530 -42. 6) Katz, B. , and Miledi, R. (1968). The role of calcium in neuromuscular facilitation. J Physiol 195, 481 -492. 7) Klingauf J, Kavalali ET, and Tsien RW. Kinetics and regulation of fast endocytosis at hippocampal synapses. Nature 394: 581 -585, 1998. 8) Lundh, D. (1997) A kinetic model on calcium residues and facilitation. Brain Research Bulletin 45, 589 -597. 9) Sheng, Z. , Westenbroek, R. E. and Catterall, W. A. (1998). Physical Link and Functional Coupling of Presynaptic Calcium Channels and the Synaptic Vesicle Docking/Fusion Machinery. Journal of Bioenergetics and Biomembranes 30, 335 -345. 10) Wang, T. , Xu, H. , Oberwinkler, J. , Gu, Y. , Hardie, R. and Montell, C. (2005). Light Activation, Adaptation, and Cell Survival Functions of the Na+/Ca 2+ Exchanger Cal. X. Neuron 45, 367 -378. 11) Wang C and Zucker RS. Regulation of synaptic vesicle recycling by calcium and serotonin. Neuron 21(1): 155 -67, 1998. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Funding was provided by NSF grant IBN-0131459.