The household production in National Accounts Italys study

- Slides: 39

The household production in National Accounts Italy’s study Monica Montella Task Force UNECE- Geneva, november 26 -27

Task Force UNECE- Geneva, november 26 -27 Summary Ø Satellite Account System by SNA 08 Ø The household production in National Accounts (SNA)/(ESA) Ø Estimation method to be used Ø The sequence of accounts including household production Ø Open questions 2

Task Force UNECE- Geneva, november 26 -27 Satellite Account System by SNA 08 A further and more extensive form of flexibility is that of a satellite account. As its name indicates, it is linked to, but distinct from, the central system. Many satellite accounts are possible but, though each is consistent with the central system, they may not always be consistent with each other. Satellite accounts incorporate the concepts of the central framework of national economic accounts, enhancing analytical skills. 3

Task Force UNECE- Geneva, november 26 -27 Satellite Account System by SNA 08 4 Broadly speaking, there are two types of satellite accounts. One type involves some rearrangement of central classifications and the possible introduction of complementary elements. Such satellite accounts mostly cover accounts specific to given fields such as education, tourism and environmental protection expenditures and may be seen as an extension of the key sector accounts just referred to. They may involve some differences from the central system, such as an alternative treatment of ancillary activities, but they do not change the underlying concepts of the SNA in a fundamental way (SNA 08 cfr: 29. 5).

Task Force UNECE- Geneva, november 26 -27 Satellite Account System by SNA 08 5 The second type of satellite analysis is mainly based on concepts that are alternatives to those of the SNA. These include a different production boundary, an enlarged concept of consumption or capital formation, an extension of the scope of assets, and so on. Often a number of alternative concepts may be used at the same time. This second type of analysis may involve, like the first, changes in classifications, but in the second type the main emphasis is on the alternative concepts. Using those alternative concepts may give rise to partial complementary aggregates, the purpose of which is to supplement the central system (SNA 08 cfr: 29. 6).

Task Force UNECE- Geneva, november 26 -27 Satellite Account System by SNA 08 6 Satellite accounts, especially of the second sort, allow experimentation with new concepts and methodologies, with a much wider degree of freedom than is possible within the central system (SNA 08 cfr: 29. 8) There is no ambiguity in the central framework of the SNA; unpaid household services are excluded from the production boundary. However, in a satellite account it is perfectly possible to extend the production boundary so that such services may be included (SNA 08 cfr: 29. 146)

Task Force UNECE- Geneva, november 26 -27 Satellite Account System by SNA 08 7 There is fairly widespread agreement that the way in which to start measuring household services for own consumption is by means of measuring the amount of time spent on them. There is increasing interest in conducting time use surveys that make such information available. Time use surveys, however, are not unambiguous. There is the question of multitasking. For example, it is possible for somebody to prepare a meal, keep an eye on a small child and help an older child with their homework all at the same time. Should the total amount of time be divided by three or should each activity count the whole amount of time spent? (SNA 08 cfr: 29. 147)

Task Force UNECE- Geneva, november 26 -27 Satellite Account System by SNA 08 8 The basic question in valuing the time spent on household services is whether to use the opportunity cost of the person performing the task or a comparator cost. Both of these present difficulties. The opportunity cost seems appealing because application of economic theory suggests that somebody capable of earning more money than the comparator would indeed earn the extra money and pay somebody else to undertake the household tasks. But this is clearly not what happens in practice. Comparator costs may be difficult to come by and may be unrealistic (SNA 08 cfr: 29. 150)

Task Force UNECE- Geneva, november 26 -27 Satellite Account System by SNA 08 9 There are two approaches that could be taken in a satellite account. The first is to adopt an alternative treatment for consumer durables at the same time as valuing unpaid household production. The other is to leave unpaid household production excluded from the production boundary but consider replacing consumer durables by an estimate of the services they provide. Treating consumer durables as assets is also of interest in the context of measuring household saving and wealth (SNA 08 cfr: 29. 155)

Task Force UNECE- Geneva, november 26 -27 Satellite Account System by SNA 08 10 The question of valuing volunteer labour is the same as that of valuing the time spent on unpaid household activities and the same alternatives are available. If voluntary labour were valued, the following accounting entries would be necessary: a. compensation of employees of the unit employing the volunteer labour; b. income for the household to which the volunteer belongs; c. a transfer of the same amount by the volunteer to the employing unit; d. final consumption expenditure of the employing unit; e. almost always social transfers in kind. This is the same as the way it is recommended that labour inputs to collective construction projects are measured (SNA 08 cfr: 29. 160). 29. 160

Task Force UNECE- Geneva, november 26 -27 Why a household satellite accounts? 11 The purpose of HSA is to focus attention on the part of production that is not defined in the System of National Accounts. The whole production activities carried out by families, with their own capital and the unpaid work of their members for the process of production of goods and services for own use and not intended for sale is the household economy. The definition of household production expands the concept of production and the productive role of families is recognized.

Task Force UNECE- Geneva, november 26 -27 Household production definition 12 The concept of household production more internationally accredited is promoted by the OECD (1995), that the production of families is embodied in goods and services produced within the household by its members (who consume them), combining their unpaid work with consumer durables and non durables purchased in the market. In addition to the production of market which provides a framework of household production, the boundaries of the production of National Accounts will change, the households are not seen only as consumers but as the units involved in the production process. Besides the account by institutional sector of the families market, there is a new satellite account, the "informal household production account".

Task Force UNECE- Geneva, november 26 -27 Household production definition 1 3 The OECD definition (1995) of household production is now internationally accepted “The term household production is used to refer to goods and services produced within the household by its members by combining their unpaid labor with purchases of durable and non-durable consumption goods”. The household production must not be a market transaction; and this is called non-market production; producing non-market includes: • unpaid work; • family care; • capital formation in own account. The concept of production in general is important and complex, focuses on the production of market and non-market as defined in the SNA (System of National Accounts) and non-market production is not included in SNA.

Task Force UNECE- Geneva, november 26 -27 Household satellite account system by ESA 2010 14 ESA 2010 22. 89– 22. 95 Household production includes only services that can be delegated to someone other than the person benefiting from it (third party-principle). Different principal functions can be distinguished: housing, nutrition, clothing, care (children, adults and pets) and volunteer work. In the present work we have been used the following functions: accommodation / lodging, meals and nutrition, clothing and laundry services, assistance and care to children and the elderly, volunteering / informal help; transport services. The output and value added of household production can be valued using an input or an output method. The output method implies that household production is valued at market equivalent prices (i. e. the value observed for similar services explicitly sold on the market). The input method it is crucial what valuation is chosen for the labour inputs, e. g. wages including or excluding social security contributions and what reference group should be chosen (average wages, wages of specialist workers or wages of generalist housekeepers).

Task Force UNECE- Geneva, november 26 -27 Entire Economic Production Different units household SNA market Production Market output by units other than household for market transaction SNA non market Production Other non market output units other than household of Household production SNA market Household production Goods and services produced in household units and supplied on the market to units other than their producer 15 Non-market Household production SNA Non-market Household production - Own-account production of goods; - Own-account construction of dwellings; - The own-account production of housing services by owneroccupiers; - Domestic and personal services produced by employing paid domestic staff; - Volunteer activities that result in goods (e. g. the construction of a church). NON-SNA Nonmarket Household production - NON SNA Household production → of which: ownaccount production of services (transport) → Informal help to other households → Volunteer work (services)

Task Force UNECE- Geneva, november 26 -27 NON MARKET NON-SNA Household production Household Production by functions Main outputs / principal functions: - Providing housing /accommodation - Providing meals and nutrition - Providing clothing and laundry services - Providing care - Providing transport - Volunteer work and informal help 16

Task Force UNECE- Geneva, november 26 -27 Estimation method to be used Output-based method Value of outputs (quantity x price) the market prices of equivalent goods and services include VAT and taxes/subsidies on products (price concept is actually purchaser’s price): – intermediate consumption = gross value added – consumption of capital – other taxes on production + other subsidies on production = mixed income (which comprises labour compensation and net operating surplus). 17

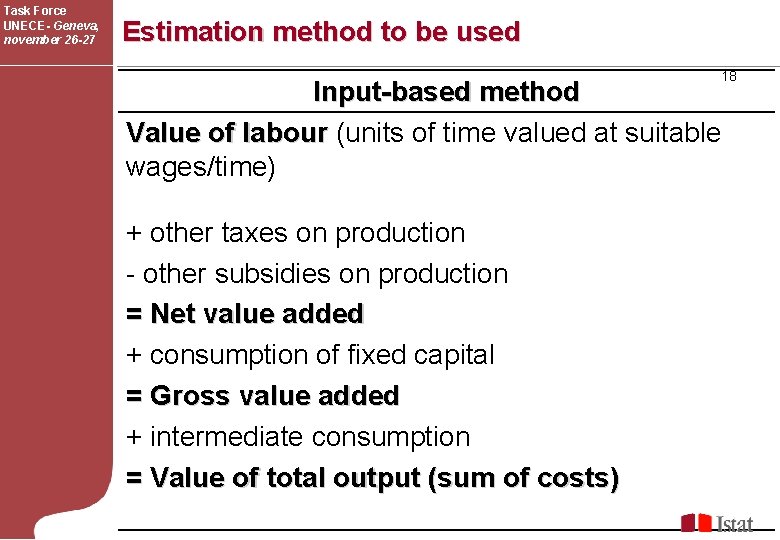

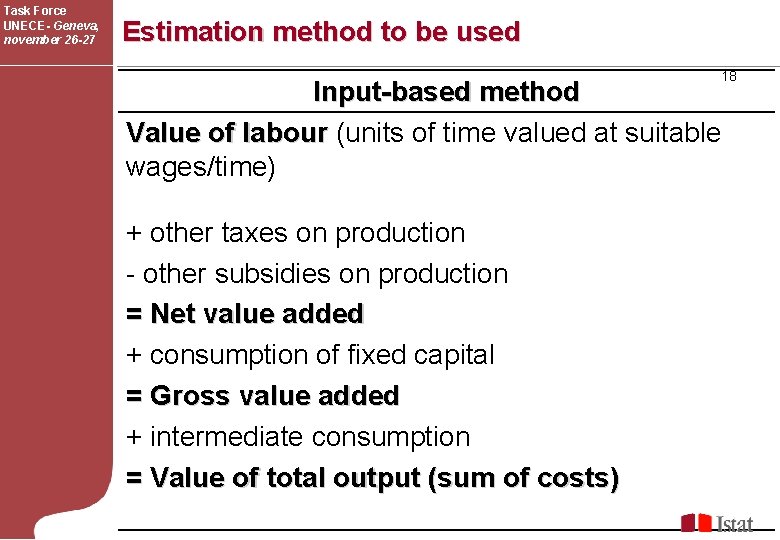

Task Force UNECE- Geneva, november 26 -27 Estimation method to be used 18 Input-based method Value of labour (units of time valued at suitable wages/time) + other taxes on production - other subsidies on production = Net value added + consumption of fixed capital = Gross value added + intermediate consumption = Value of total output (sum of costs)

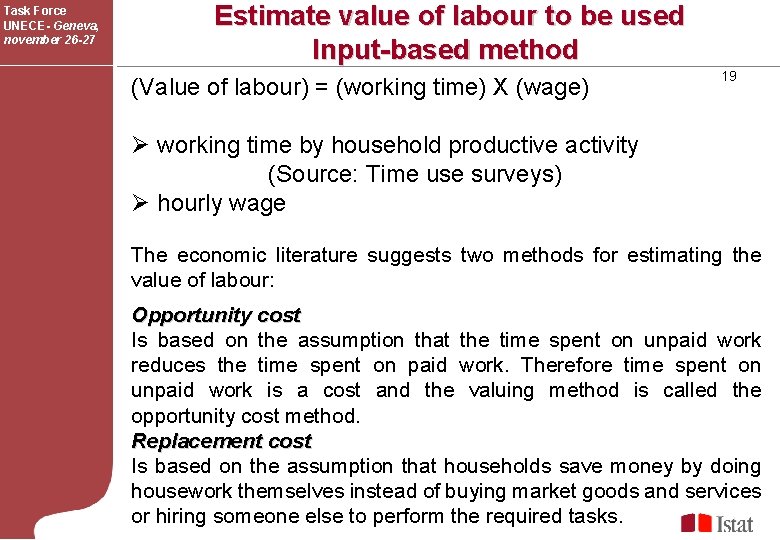

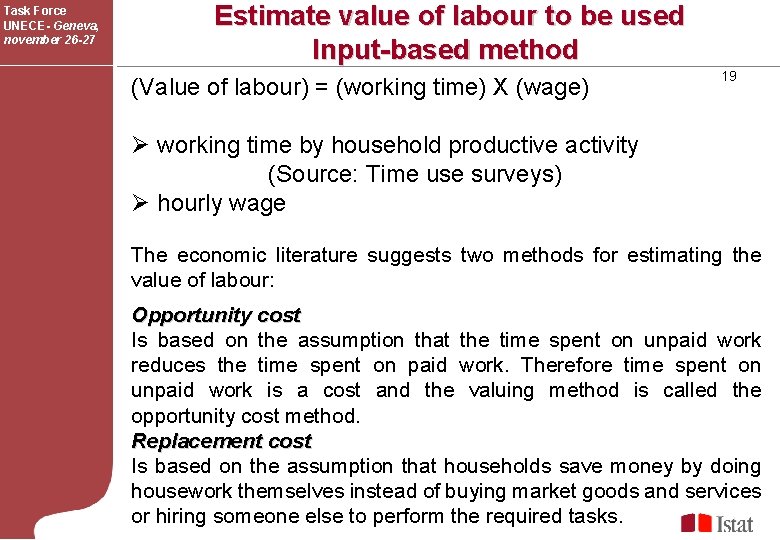

Task Force UNECE- Geneva, november 26 -27 Estimate value of labour to be used Input-based method (Value of labour) = (working time) X (wage) 19 Ø working time by household productive activity (Source: Time use surveys) Ø hourly wage The economic literature suggests two methods for estimating the value of labour: Opportunity cost Is based on the assumption that the time spent on unpaid work reduces the time spent on paid work. Therefore time spent on unpaid work is a cost and the valuing method is called the opportunity cost method. Replacement cost Is based on the assumption that households save money by doing housework themselves instead of buying market goods and services or hiring someone else to perform the required tasks.

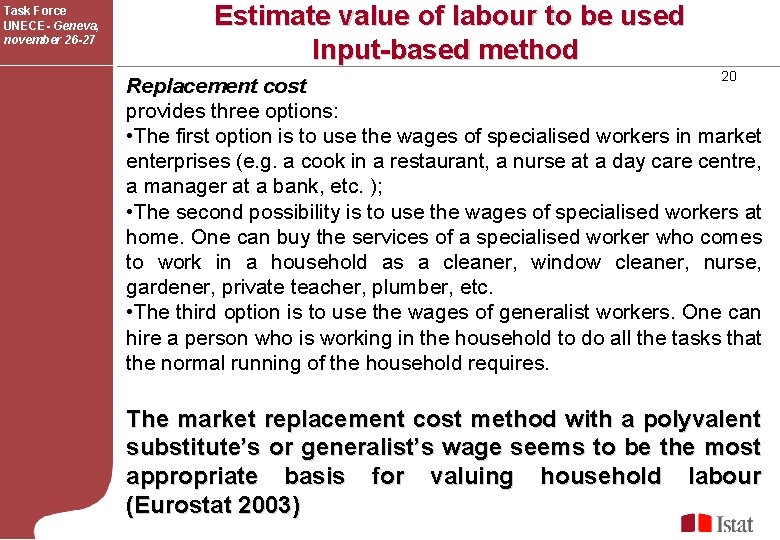

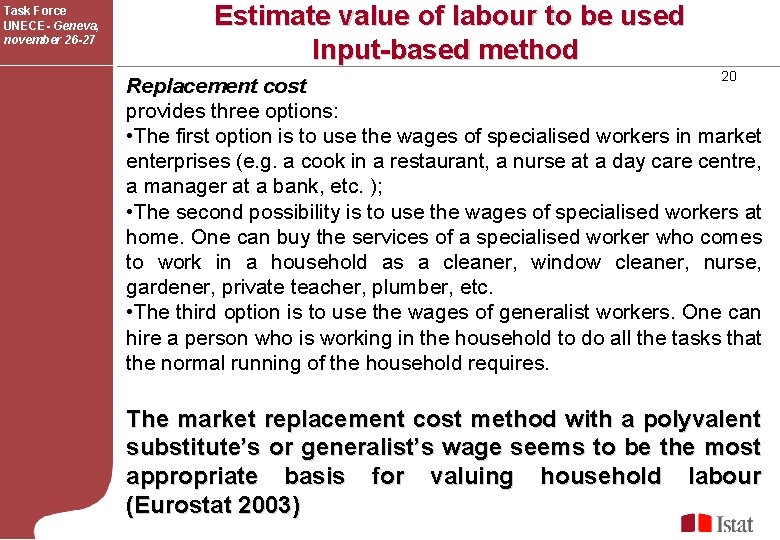

Task Force UNECE- Geneva, november 26 -27 Estimate value of labour to be used Input-based method 20 Replacement cost provides three options: • The first option is to use the wages of specialised workers in market enterprises (e. g. a cook in a restaurant, a nurse at a day care centre, a manager at a bank, etc. ); • The second possibility is to use the wages of specialised workers at home. One can buy the services of a specialised worker who comes to work in a household as a cleaner, window cleaner, nurse, gardener, private teacher, plumber, etc. • The third option is to use the wages of generalist workers. One can hire a person who is working in the household to do all the tasks that the normal running of the household requires. The market replacement cost method with a polyvalent substitute’s or generalist’s wage seems to be the most appropriate basis for valuing household labour (Eurostat 2003)

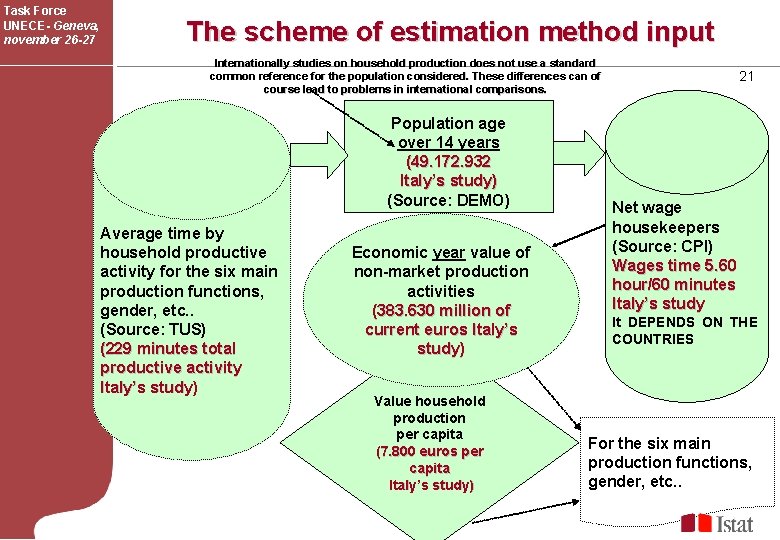

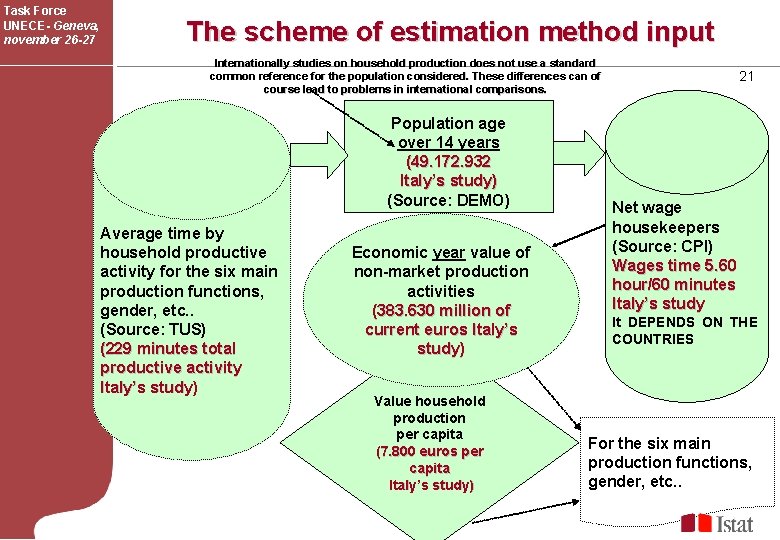

Task Force UNECE- Geneva, november 26 -27 The scheme of estimation method input Internationally studies on household production does not use a standard common reference for the population considered. These differences can of course lead to problems in international comparisons. Population age over 14 years (49. 172. 932 Italy’s study) (Source: DEMO) Average time by household productive activity for the six main production functions, gender, etc. . (Source: TUS) (229 minutes total productive activity Italy’s study) Economic year value of non-market production activities (383. 630 million of current euros Italy’s study) Value household production per capita (7. 800 euros per capita Italy’s study) 21 Net wage housekeepers (Source: CPI) Wages time 5. 60 hour/60 minutes Italy’s study It DEPENDS ON THE COUNTRIES For the six main production functions, gender, etc. .

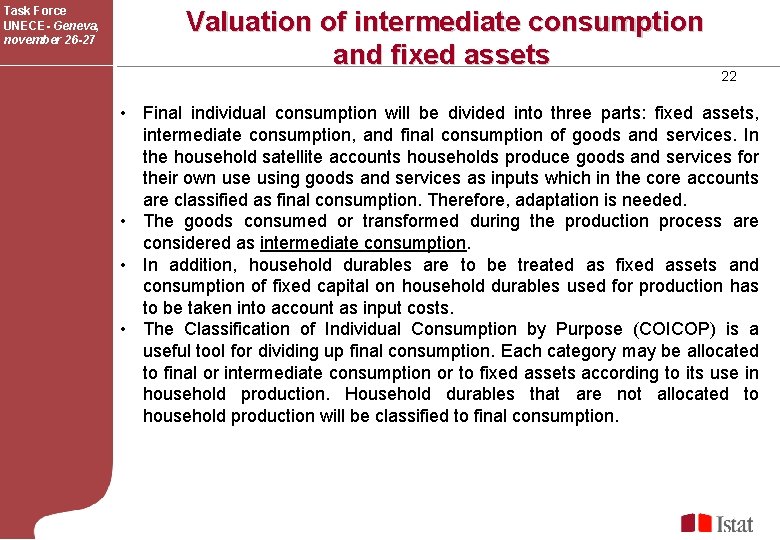

Task Force UNECE- Geneva, november 26 -27 Valuation of intermediate consumption and fixed assets 22 • Final individual consumption will be divided into three parts: fixed assets, intermediate consumption, and final consumption of goods and services. In the household satellite accounts households produce goods and services for their own use using goods and services as inputs which in the core accounts are classified as final consumption. Therefore, adaptation is needed. • The goods consumed or transformed during the production process are considered as intermediate consumption. • In addition, household durables are to be treated as fixed assets and consumption of fixed capital on household durables used for production has to be taken into account as input costs. • The Classification of Individual Consumption by Purpose (COICOP) is a useful tool for dividing up final consumption. Each category may be allocated to final or intermediate consumption or to fixed assets according to its use in household production. Household durables that are not allocated to household production will be classified to final consumption.

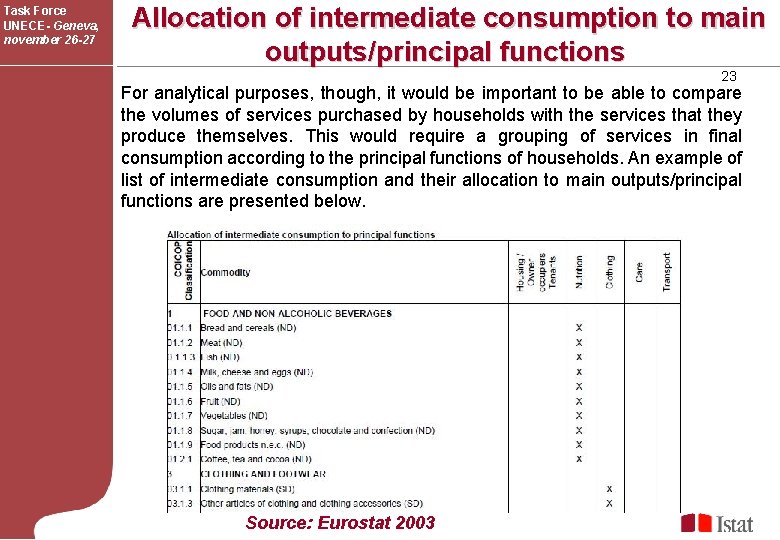

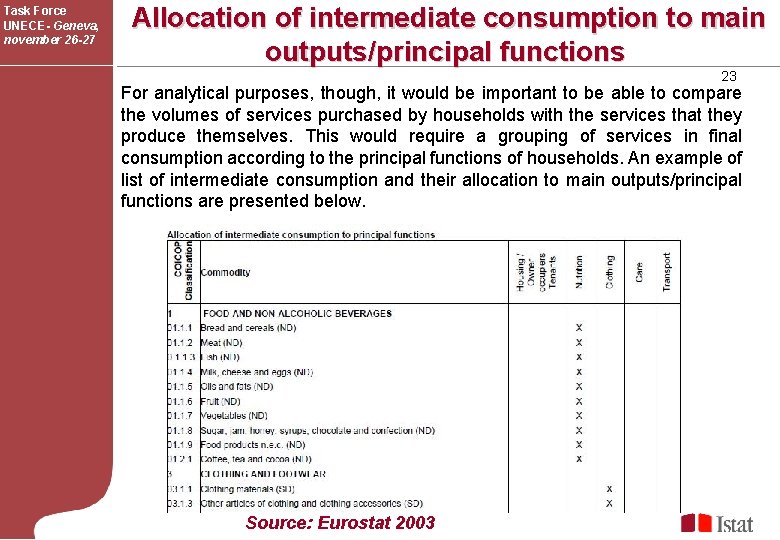

Task Force UNECE- Geneva, november 26 -27 Allocation of intermediate consumption to main outputs/principal functions 23 For analytical purposes, though, it would be important to be able to compare the volumes of services purchased by households with the services that they produce themselves. This would require a grouping of services in final consumption according to the principal functions of households. An example of list of intermediate consumption and their allocation to main outputs/principal functions are presented below. Source: Eurostat 2003

Task Force UNECE- Geneva, november 26 -27 Allocation of intermediate consumption to main outputs/principal functions 24 When starting the allocation decisions, countries face questions such as: - what are the production processes like in our country? - what sort of products are in supply? - what kind of the data sources are available? Some countries can use 4 -digit level COICOP data and very detailed level time use data, some countries have much less detailed data available. Source: Eurostat 2003 It is necessary to give a unique detailed list of the allocation intermediate consumption and fixed capital applicable for any country to use.

Task Force UNECE- Geneva, november 26 -27 Valuation fixed assets in household production 25 Fixed capital used in household production The boundary line between fixed assets and intermediate consumption is clarified in the SNA. Expenditures on durable producer goods that are small, inexpensive and used to perform relatively simple operations may be treated as intermediate consumption when such expenditures are made regularly and are very small compared with expenditures on machinery and equipment. Examples of such goods are hand tools such as saws, spades, knives, axes, hammers, screwdrivers, and so on. However, in countries where such tools account for a significant part of the stock of producers’ durable goods, they may be treated as fixed assets (SNA 08 6. 225).

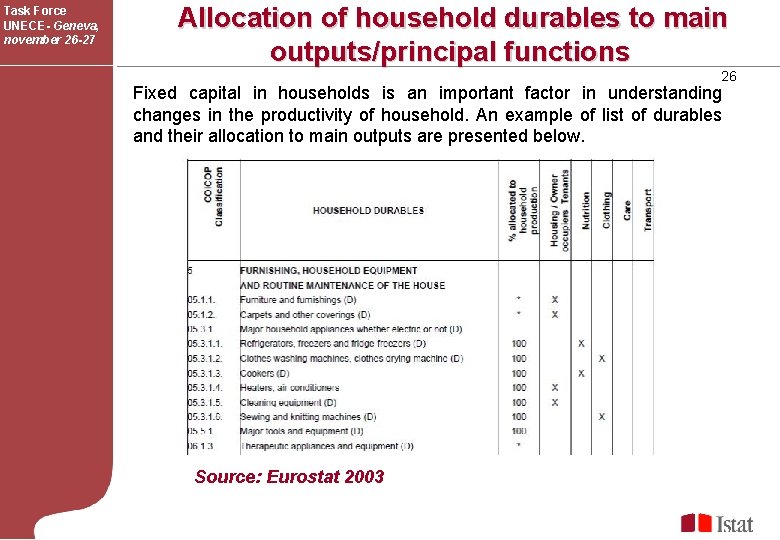

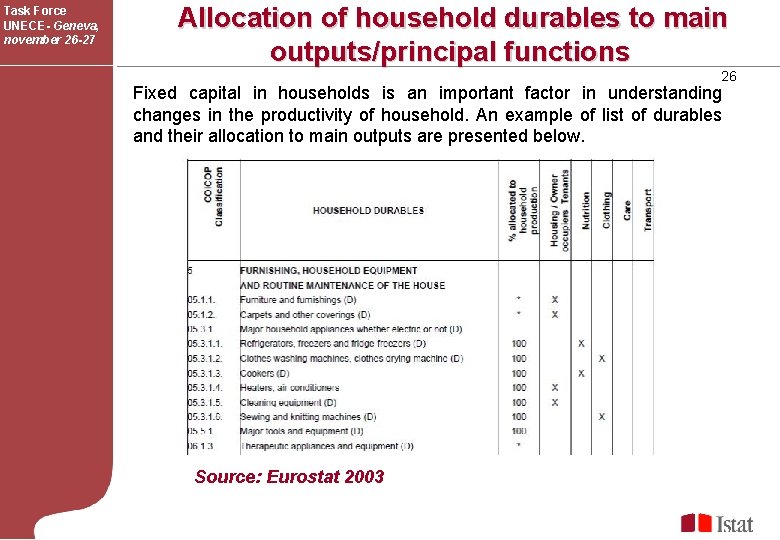

Task Force UNECE- Geneva, november 26 -27 Allocation of household durables to main outputs/principal functions 26 Fixed capital in households is an important factor in understanding changes in the productivity of household. An example of list of durables and their allocation to main outputs are presented below. Source: Eurostat 2003

Task Force UNECE- Geneva, november 26 -27 Allocation of intermediate consumption and household durables to main outputs/principal functions 27 Source: Montella studies ESA 95 and National Account In Italy’s study for consumption of fixed capital it was adopted the perpetual inventory method (with possibility of deterioration linear), which allows you to obtain an estimate of the gross and net stock of consumer durables held by households. Depreciation shares with constant capital.

Task Force UNECE- Geneva, november 26 -27 Consumption of fixed capital 28 Consumption of fixed capital is the decline, during the course of the accounting period, in the current value of the stock of fixed assets owned and used by a producer as a result of physical deterioration, normal obsolescence or normal accidental damage. The term depreciation is often used in place of consumption of fixed capital but it is avoided in the SNA because in commercial accounting the term depreciation is often used in the context of writing off historic costs whereas in the SNA consumption of fixed capital is dependent on the current value of the asset. The ”Perpetual Inventory Method” or PIM is in widespread international use for purposes of estimating the value of consumption of fixed capital. http: //www. oecd. org/std/productivity-stats/43734711. pdf The PIM has also been used and recommended in the context of household production. Which models used in calculating the depreciation of economic value? The geometric and the straight-line depreciation model or other? (SNA 08 cfr. 6. 240)

Task Force UNECE- Geneva, november 26 -27 Consumer durables 29 There are two approaches that could be taken in a satellite account. The first is to adopt an alternative treatment for consumer durables at the same time as valuing unpaid household production. The other is to leave unpaid household production excluded from the production boundary but consider replacing consumer durables by an estimate of the services they provide. Treating consumer durables as assets is also of interest in the context of measuring household saving and wealth. Examples of this type of analysis can be found in Durable Goods and their Effect on Household Saving Ratios in the Euro Area (Jalava et al, 2006), (SNA 08 cfr. 29. 155).

Task Force UNECE- Geneva, november 26 -27 Italy’s study 30 Source: Montella studies ESA 95 M_TUS 2002 and National Account

Task Force UNECE- Geneva, november 26 -27 Estimate taxes and social security contributions 31 Taxes and social security contributions may amount to up to half the wages, depending on the country and the welfare system. If households were to buy the service from the market, they would have to pay the gross wage. On the other hand, if it is thought that households earn the money by producing the services themselves, then the net wage would obviously be more appropriate because the household would not have to pay taxes or social security contributions for themselves. The choice depends again on the purpose of the analysis. About: - Taxes on production - Miscellaneous current taxes It might be necessary to check which of these taxes need to be reclassified as other taxes on production for the purposes of household satellite accounts.

Task Force UNECE- Geneva, november 26 -27 The HSA in National Accounts 32 The household satellite account (HSA) can be integrated with accounts by institutional sector, the supply and use table (SUT), and the resources and uses account to obtain measures of the extension of household production. The main purpose of satellite accounts is to give an integrated picture of a given field of economic activities, flexibly expanding the analytical capacity of national accounting without overburdening or disrupting the central system.

Task Force UNECE- Geneva, november 26 -27 A case study (Italy) The satellite account of households production 33 Year 2002 (millions of current euro) Source: Montella studies ESA 95 M_TUS 2002 and National Account

Task Force UNECE- Geneva, november 26 -27 Open questions 34 Ø In the output method approach there may be a problem in considering the treatment of simultaneous activities simply taking all outputs into account. Ø Definitions of outputs, in practice, depend on the data sources available. This may lead to undue differences between countries, depending on the range of existing surveys or the willingness to undertake additional surveys (there is only limited experience with the output surveys ( approach). Ø It is necessary, if the method of input is adopted, to develop an harmonization of time-use survey (TUS). Ø It is necessary to give a unique detailed list of the allocation intermediate or final consumption applicable for any country to use. These differences can of course lead to problems in international comparisons.

Task Force UNECE- Geneva, november 26 -27 Open questions 35 Ø Internationally studies on household production does not use a standard common reference for the population considered; the United States uses the population over 18 (JS Landefeld et al. 2009), the OECD that more than 15 years and Finland sets the limit at under 10 years (Varjonen et al 2006). These differences can of course lead to problems in international comparisons. Ø In ESA 2010 22. 89– 22. 95 we have a first specific point In ESA 2010 on Household production accounts. Another important on issue is to include the full Household production issue is to include the full accounts also in SNA.

Task Force UNECE- Geneva, november 26 -27 Conclusion 36 The Household production accounts: • provides information on the unpaid domestic work; • describes statistically aspects hitherto unmeasured; • highlights the importance of household production compared to the income produced in a territory; • allows the comparison of the household production with other economic activities in GDP; • determining the value of household production can be used in social policy (example, alimony or the amount of survivor's pension); • allows to analyze and better understand the private consumption. It is recognized internationally that an appropriate accounting of household production would support the definition and adoption of policy measures in support of a more harmonious development.

Task Force UNECE- Geneva, november 26 -27 37 Thank you for your attention For more information: montella@istat. it

Task Force UNECE- Geneva, november 26 -27 References 38 Abraham K. G. and C. Mackie. 2005. Beyond the market. Designing Non market Accounts for the United State”. Panel to Study the Design of Non market Accounts. The National Academies Press, National Research Council. Baldassarini A. e M. C. Romano 2006. Non market household work in National Accounts. Presented at 18 th Annual Meeting on Socio-Economics Trier, Germany June 30 July 2. Becker G. S. 1965. A theory of the allocation of time. The Economic Journal, pp. 493 – 517. Casero V. and C. Angulo. 2008. A satellite account of the households in Spain. 2003 Results derived from Time Use Survey 2002 -2003. Working papers 1/08. Madrid, June 2008. Chadeau A. 1985. Measuring household activities: some international comparisons, Review of Income and Wealth, 3: pp. 237 -253 Clark C. 1958. The economics of housework. Bulletin of the Oxford Institute of Statistics , (May). Corea C. , Donnarumma I. and E. Frenda. 2009. La stima dello stock dei beni durevoli delle famiglie: un primo contributo sperimentale. Contributo Istat n° 6/2009, Istat. Corea C. , Di Leo F. e S. Massari. 2000. La Spesa per consumo delle famiglie. Contributo presentato al seminario La nuova Contabilità Nazionale, 12 -13 gennaio, Istat. ESA. 2010. Manual European System Accounts DRAFT versione marzo 2010, part II. European Commission. 2009. GDP and beyond: Measuring progress in a changing world. Brussels Eurostat. 2003. Household production and consumption: proposal for a methodology of household satellite accounts. Working papers and studies European Commission, theme 3, population and social conditions. Eurostat. 1996. European System of Accounts, ESA 1995. Eurostat. 2011. Emphasise the Household perspective. Report of the task force on the household perspective and distributional aspects of income, consumption and wealth, . Lussemburgo Fraumeni B. M. 2008 a. Household production accounts for Canada, Mexico and the Unite States: methodological issues, results and recommendations. Paper presented at 30 th General Conference of IARIW. Fraumeni B. M. 2008 b. Human capital: from indicators and indexes to accounts. Paper presented at Workshop on the Measurement of Human Capital, Fondazione Giovanni Agnelli, Turin 3 -4 nov. Giannelli G. C. , L. Mangiavacchi and L. Piccoli. 2010. GDP and the Value of Family Caretaking: How Much Does Europe Care ? IZA Discussion Paper No. 5046. Goldschmidt-Clermont L. 1982. Unpaid Work in the Household: A Review of Economic E valuation Methods. International Labour Office, Geneva. Goldschmidt-Clermont L. 1993. Monetary Valuation of Non-Market Productive Time – Methodological Considerations. The Review of Income and Wealth , 39, pp. 419 -433 Goldschmidt-Clermont L. 1994. Accounting in monetary terms for unpaid household work. In Kalfs N. and A. S. Harvey (eds), Fifteen Reunion of the International Association of Time Use Research: Amsterdam, June 15 -18, 1993, NIMMO, Amsterdam, pp 47 -54 Gørtz M. 2006. Household production in the family. Work or pleasure ? CAM Department of economics, University of Copenhagen Harvey A. S. and A. K. Mukhopadhyay. 2005. Household Production in Canada: Measuring and Valuing Outputs. In Hoa T. V. (ed. ), Advances in Household Economics, Consumer Behaviour and Economic Policy, Ashgate, U. K. , pp. 70– 84. Ichino A. e A. Alesina. 2009. L’Italia fatta in casa. Indagine sulla vera ricchezza degli italiani. Mondatori. Ironmonger D. S. 2001. Household production. In Smelser N. J. & P. B. Baltes (eds), International Encyclopaedia of the Social and Behavioural Sciences, Volume 10, Elsevier Science, Oxford. Ironmonger D. S. 1996. Counting outputs, capital inputs and caring labor: Estimating Gross Household Product. Feminist Economics, vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 37 -64. Istat. 2007. Indagine multiscopo sulle famiglie " Uso del tempo" - Anni 2002 -2003. Collana: Informazioni, n. 2, Istat. Jalava J and I. K. Kanovius. 2007. Durable good and their effect on household saving ratios in the euro area. European Central Bank Working Paper Series No. 755, May. Kende P. 1975. Vers une valuation de la consommation réelle des ménages. Revue Consommation , Avril-Juin. Kulshreshtha A. C. and G. Singh. 2000. Valuation of non-market household production. Central Statistical Organisation, New Delhi. Kuznets S. 1944. National Income and its Composition. 7979 -7938, National Bureau of Economic. Kuznets S. 1934. National Income 1929– 1932. Senate Document No. 124 , 73 rd Congress, 2 nd Session, U. S. Government Printing Office, Washington DC.

Task Force UNECE- Geneva, november 26 -27 References 39 Landefeld J. S. , Fraumeni B. M. and M. C. Vojtech. 2009. Accounting for household production: a prototipe satellite account using the American time use survey. Review of Income and Wealth Series, 55, Number 2, June. Nordhaus W. and J. Tobin. 1972. Is Growth Obsolete? National Bureau of Economic Research. OECD. 1992. What is household non-market production worth. by Chadeau A. , OECD Economic Studies No. 18, Spring 1992. OECD. 1995. Household production in OECD countries. Data sources and measurement methods, OECD Paris OECD. 1999. Proposal for a satellite account of household production, Paris. OECD. 2011. Incorporating estimates of household production of non-market services into international comparisons on material well-being. Nadim AHmad e Seung Hee Koh, documento presentato al meeting of the committee on statistics 8 th session; STD/CSTAT/2011/10, 27 maggio 2011, Ginevra. Office for National Statistics. 2002. Household satellite account (experimental) methodology. Holloway S. , S. Short, S. Tamplin, April. OIL. 2011. International Labour Organization, Manual of Measurement of Volunteer Work, Final approved pre-publication version, Geneva, March 2011. Perkins Gilman C. 1898. Women and Economics Boston, MA: Small, Maynard & Co. Quist J. , Szita K. and K. Toth. 1998. Green Shopping, Cooking and Eating in the Sustainable Household. Paper presented at the Workshop The sustainable household: Technological and cultural changes, organised by Vergragt Ph. Reid M. G. 1934. Economics of household production. New York, J. Wiley & Sons; London, Chapman & Hall Rüger Y. and J. Varjonen. 2008. Value of household Production in Finland Germany. Analysis and recalculation of the household satellite account system in both countries. National Consumer Research Centre Working Papers 112. Sakuma I. 2010. The Production Boundary Reconsidered. Paper prepared for the 31 st General Conference of The International Association for Research in Income and Wealth. St. Gallen, Switzerland, August 22 -28, . Soupourmas F. and D. Ironmonger. 2002. Calculating Australia’s Gross Household Product: Measuring the Economic Value of the Household Economy 1970– 2000. University of Melbourne, Department of Economics, Working Paper 833. Statistics Finland National Consumer Research Centre. 2006. Household production and consumption in Finland 2001 - Household satellite account. Helsinki. Stiglitz J. and A. Sen, P. Fitoussi. 2009. Report by the Commission on the Measurement of economic performance and social progress. Swiss Federal Statistical Office. 2010. http: //www. bfs. admin. ch/bfs/portal/en/index/themen/20/04/blank/key/sat_kont/01. html United Nations. 1995. Fourth World Conference on Women. 4 -15 September, Beijing, China. United Nations, Eurostat, IMF, World Bank, 1993, System of National Accounts 1993 United Nations OECD, European Commission, International Monetary Fund, , World Bank. 2009. SNA 08 - System of a National Accounts. 2008. New York. Bruxelles, Luxembourg, New York, Paris, Washington D. C Van de Ven P. , K. Brugt and S. Keuning. 1999. Measuring well-being with an integrated system of economic and social accounts. Statistics Netherlands Division Presentation and Integration Department of National Accounts. Varjonen J. , Niemi, I. , Hamunen, E. Pääkkönen, H. and T. Sandström. 1999. Proposal for a Satellite Account of Household Production. Eurostat Working Papers 9/1999/A 4/11. Varjonen J. and I. Niemi. 2000. A proposal for a European satellite account of household production. In Household Accounting: Experience in Concepts and Compilation, Volume 2, Household Satellite Extensions, Studies in Methods, Series F, No. 75 /Vol. 2 Handbook of National Accounting, United Nations, New York. Walker K. and W. H. Gauger. 1973. Time and its dollar value in household work, Family Economics Review. Waring M. 1988. If Women Counted: A New Feminist Economics. Harper&Row, San Francisco. Waring M. and E. Sonius. 1989. Household productive activities. Chapter 2. In Ironmonger D. (ed. ) Households Work: Productive Activities, Women and Income in the Household Economy, Allen&Unwin, Sydney, pp. 18 -32. Wood C. A. 1997. The First World/Third Party Criterion: A Feminist Critique of Production Boundaries in Economics. Feminist Economics 3(3), pp. 47 -68.

Alur proses produksi multimedia

Alur proses produksi multimedia Household production model

Household production model York national accounts

York national accounts The national income and product accounts

The national income and product accounts National account systems

National account systems System of national accounts (sna)

System of national accounts (sna) Advisory expert group on national accounts

Advisory expert group on national accounts Chapter 13 study guide production and business operations

Chapter 13 study guide production and business operations Hình ảnh bộ gõ cơ thể búng tay

Hình ảnh bộ gõ cơ thể búng tay Lp html

Lp html Bổ thể

Bổ thể Tỉ lệ cơ thể trẻ em

Tỉ lệ cơ thể trẻ em Chó sói

Chó sói Chụp tư thế worms-breton

Chụp tư thế worms-breton Bài hát chúa yêu trần thế alleluia

Bài hát chúa yêu trần thế alleluia Các môn thể thao bắt đầu bằng tiếng bóng

Các môn thể thao bắt đầu bằng tiếng bóng Thế nào là hệ số cao nhất

Thế nào là hệ số cao nhất Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới

Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới Cong thức tính động năng

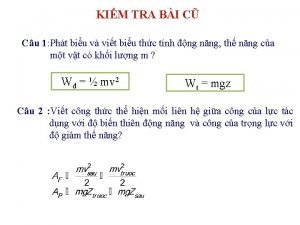

Cong thức tính động năng Trời xanh đây là của chúng ta thể thơ

Trời xanh đây là của chúng ta thể thơ Mật thư anh em như thể tay chân

Mật thư anh em như thể tay chân 101012 bằng

101012 bằng độ dài liên kết

độ dài liên kết Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới

Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới Thể thơ truyền thống

Thể thơ truyền thống Quá trình desamine hóa có thể tạo ra

Quá trình desamine hóa có thể tạo ra Một số thể thơ truyền thống

Một số thể thơ truyền thống Cái miệng nó xinh thế chỉ nói điều hay thôi

Cái miệng nó xinh thế chỉ nói điều hay thôi Vẽ hình chiếu vuông góc của vật thể sau

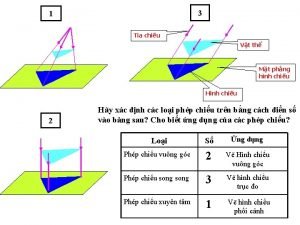

Vẽ hình chiếu vuông góc của vật thể sau Biện pháp chống mỏi cơ

Biện pháp chống mỏi cơ đặc điểm cơ thể của người tối cổ

đặc điểm cơ thể của người tối cổ Giọng cùng tên là

Giọng cùng tên là Vẽ hình chiếu đứng bằng cạnh của vật thể

Vẽ hình chiếu đứng bằng cạnh của vật thể Vẽ hình chiếu vuông góc của vật thể sau

Vẽ hình chiếu vuông góc của vật thể sau Thẻ vin

Thẻ vin đại từ thay thế

đại từ thay thế điện thế nghỉ

điện thế nghỉ Tư thế ngồi viết

Tư thế ngồi viết Diễn thế sinh thái là

Diễn thế sinh thái là Dot

Dot