The Growth of Cognitive modeling in HumanComputer Interaction

- Slides: 53

The Growth of Cognitive modeling in Human-Computer Interaction Since GOMS Presented by: Daniel Loewus-Deitch Douglas Grimes

Purpose of Article (1) n n Evaluate the current status of our methods for modeling HCI cognition and analyzing task performance. Review the evolution of GOMS and MHP and how subsequent research has supported and extended this framework.

Purpose of Article (2) n Examine 3 new directions for this framework: Study of learning and transfer. n Study of errors. n Analysis of parallel processes. n

Some Central Issues n n n How people transfer between skilled performance and problem solving. Designing consistent user interfaces. How people produce and manage errors. How we interpret visual displays. When processes are parallel and when they are serial.

Usefulness and Goals of Cognitive Modeling n Main goal: n Predicting how users will interact with proposed designs.

Usefulness and Goals of Cognitive Modeling n Useful in: Initially constraining the design space. n Answering specific design decisions, including various tradeoffs. n Estimating the total time for task performance. n Estimate training time and guide training documentation. n Discovering the most resource-intensive and error-prone stages of an activity. n

GOMS and MHP n Card et al. proposed their framework to help system designers Gather detailed knowledge about the processes of perception to action. n Generate predictions about human behavior and task performance in “real, naturalistic settings. ” n

GOMS and MHP n Two key components: n MHP (Model Human Processor) – a general characterization of the human as an information-processing system, including a System architecture n Library of quantitative parameters that breaks down task performance into specific components. n

GOMS and MHP n Two key components: n GOMS (Goals, Operators, Methods, and Selecction rules) – A family of models that describes what the user needs to know in order to perform computer-based tasks.

GOMS and MHP n Steps of theoretical process: User perceives activity on screen. n Evaluates whether it is what is expected. n Sets up an intention of the next step (goals). n Retrieves way to enact this intent on the system. n Executes appropriate motor movements. n Repeat process. n

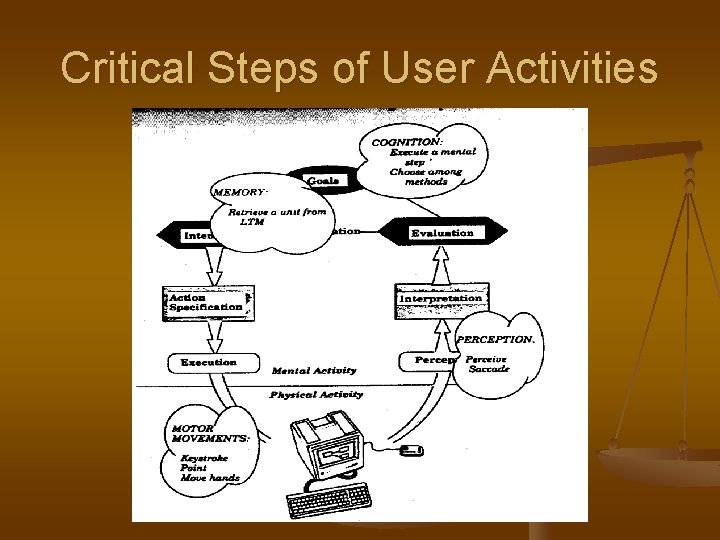

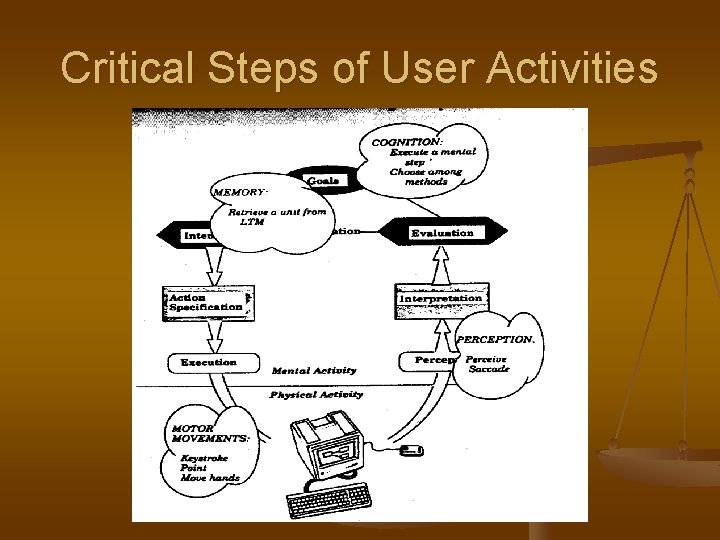

Critical Steps of User Activities

Assumptions n n n Routine cognitive skills can be described as a serial sequence of cognitive operations and motor activities. Each time parameter is independent of context (the same in any task). Empirical data derived from use of text editors, graphic systems, etc. is generalizable.

Strengths n n Can accurately predict the time it takes a skilled user to execute a task based on a set of composite actions. Certain component parameters have been found to be very consistent across various tasks and stable across repeated experiments. n n Keystroke Pointing Moving hands Retrieving a chunk of info. from LTM.

Strengths n Allows comparisons of different design alternatives.

Limitations n n n Generalizable to new domains? Applied only to skilled users. No account of learning or delayed recall. No account of errors (predicts perfect performance). Cognitive processes treated in same manner as perceptual and motor activities. No consideration of parallel processes.

Limitations n n n No consideration of mental workload. Does not determine functionality. Does not address user fatigue. No account for individual differences. Does not predict user satisfaction or acceptance. Does not consider CSCW issues.

Advances in Modeling Specific Serial Components (1) n Direct tests of two assumptions: Serial processing n Consistency of time parameters across tasks n n n Helped define and expand the MHP. Determined by studies involving entering editor commands with keyboard commands and entering formulas in spreadsheets.

Advances in Modeling Specific Serial Components (2) n Parameters are grouped into 3 classes: Motor movement n Perception n Memory and cognition n n Parameters can be mapped onto the critical steps of the user activity process (previous figure).

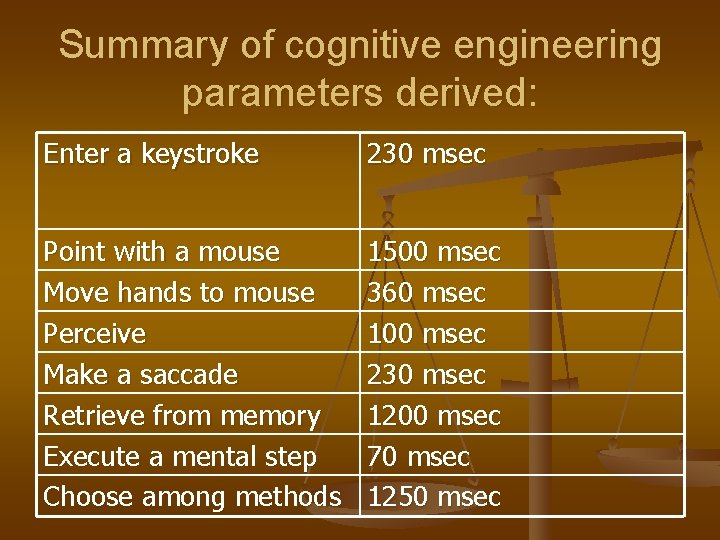

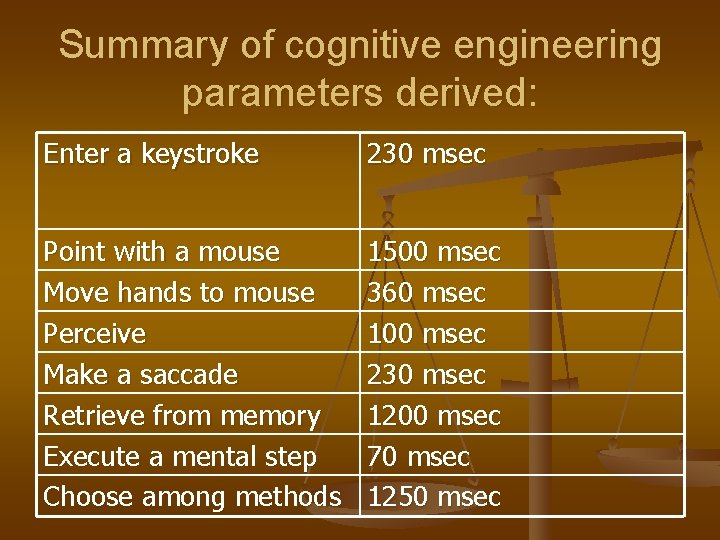

Motor Movements n Keying 230 msec n Can vary with skill level of typist, frequency of particular key use, and predictability of text being typed. n n Moving a mouse 1100 msec per selection n Varies with distance of movement and size of target (Fitt’s Law). n n Always a constant time of 1 s to began moving.

Motor Movements n Hand Movements Move from keyboard to pointing device. n Large-muscle movement. n Variation among different pointing devices. n

Perception n Perceptual processor is estimated to be 100 msec. Saccade is estimated at 230 msec. “Scanning” parameter, identified by Olson and Nielson, found in experiment to be 2300 msec. n n n User scans spreadsheet screen, looking for cell addresses. Composite of scanning, storing, and retrieving. Roughly supports previously identified time parameter estimate when broken down into components.

Memory and Cognitive Processes n Memory retrieval M (“mental”) = time to retrieve the next unit of information from LTM. n Estimated at 1350 msec. n On repeated trials, retrieval times drop 50% and remain flat, but keying times remain the same. n

Memory and Cognitive Processes n Executing steps in a task GOMS provides an explicit representation of the mental steps involved. n Kieras and Polson programmed the procedures in production system formalism. n

Memory and Cognitive Processes n Choosing among methods MHP assumes that more choices for a response lead to longer response times. n Research suggests that a choice between methods is a complex cognitive task, requiring a number of cognitive steps. n

Summary of cognitive engineering parameters derived: Enter a keystroke 230 msec Point with a mouse Move hands to mouse Perceive Make a saccade Retrieve from memory Execute a mental step Choose among methods 1500 msec 360 msec 100 msec 230 msec 1200 msec 70 msec 1250 msec

Example of Applied Use of GOMS n n Walker et al. demonstrated how GOMS can help a designer narrow down his search. Goal was to shorten menu-selection time with nested menus.

Example of Applied Use of GOMS n 3 adjustments were made and tested using GOMS techniques: Pop up submenus on right rather than bottom (shorten total distance user much move cursor to make a selection). n Target size grows as the distance from the cursor increases (Fittsized menus). n Add a virtual border around the pop-up menu (increase target size). n

Accuracy in Predicting Composite Performance n Young and Mac. Lean measured the times of people entering a block of values in a spreadsheet using 2 different methods: Mouse method n Menu method n n Showed that using these parameters can provide sufficient accuracy for this level of analysis (14% error range in this case).

Extensions of Basic Framework n Task-Action Grammar (TAG) Knowledge a user must have in order to translate from goals to actions in a particular system. n Predicts learning with the relationship between system features and natural world associations. n Consists of commands, features of goal, dictionary of tasks, and rules that translate goals into actions. n

Extensions of Basic Framework n Production systems Represent GOMS structure and aspects of MHP. n Makes underlying knowledge much more explicit. n

Learning and Transfer n n n Reaction to GOMS’ narrow focus on skilled performance. Time to learn has been advanced by n Cognitive Complexity Theory n Payne and Green’s research on grammar rules. Transfer of training has been advanced by n Kieras and Polson’s production system models

Kieras and Polson’s Cognitive Complexity Theory (1) n Made advances by focusing on Time to learn new procedures. n Transfer of training between procedures. n n Used specialized language called NGOMSL to facilitate the programming of production system representations.

Kieras and Polson’s Cognitive Complexity Theory (2) n n First determined number of steps in procedure and then assessed the time it takes a person to learn the procedure. Can’t generalize quantified learning times to naturalistic settings.

Payne and Green n Number of rules determines ease of learning. n n More often a rule can be used, the more consistent a system is. More critical is whether features of rules follow real-world rules already familiar to the user.

Kieras and Polson’s Production System Models n n n Makes explicit exactly what it is that a person has to learn to use a new system. Productions = units of learning. Number of productions the two systems share is a good prediction of transfer. Makes consistency of design across systems explicit and quantifiable. TAG has some similar potential.

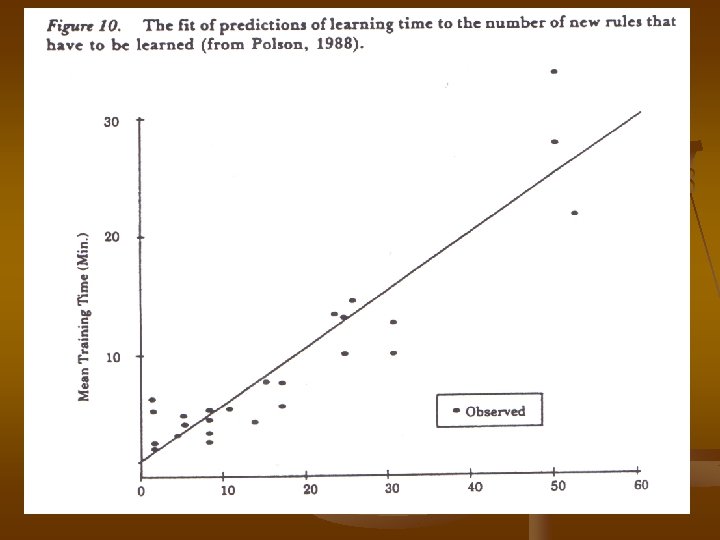

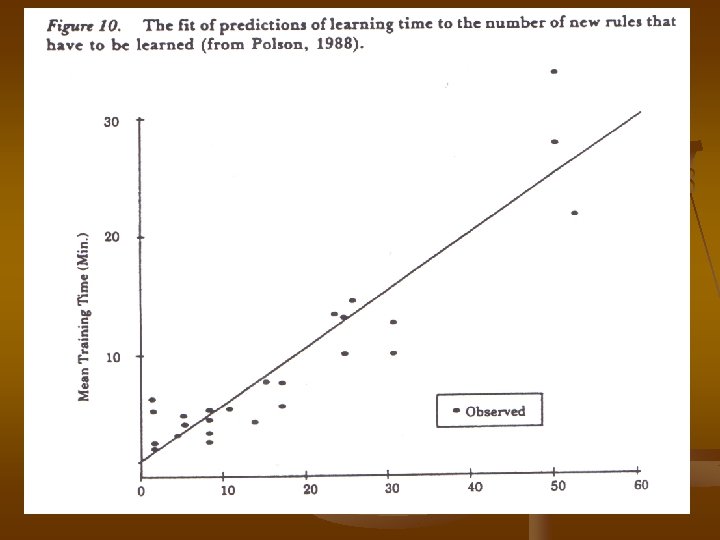

(Time to Learn Scatter Plot – Poulson)

Analysis of Errors n n Hypothesis: When working memory is overloaded, errors will increases. Test: Calculate Profit = Revenues – Costs, using Lotus 1 -2 -3 & IFPS Result: IFPS burdens working memory fewer errors Similar studies on SQL queries.

Parallel Processes n n Earlier cognitive studies assumed serial processing. Skilled motor and perceptual action is highly parallel: n n n Expert typist, musician, athlete, driver, … Serial models overestimate time for parallel tasks Skilled action is more parallel; novice action more serial.

Critical Path Analysis: Parallel + Sequential n n Theory: 3 parallel processors: perceptual, cognitive, and motor Studies of skilled typing and skilled menu use. (Author’s interpretation, not speaker’s): Expert (~33 wpm) limited by cognitive processor (e. g. , reading speed for typist) n Novice (~6 wpm) limited by motor speed. n

Q’s on Critical Path Analysis n If cognitive processor is the bottleneck for expert typist, why can expert typists read much faster than they type? Do we “chunk” letters together in preconscious processing, then “unchunk” them to type? n Where do we draw the line between perception and cognition? Example shows reading is one word at a time with constant time per word, but recognizing words is a cognitive process, whether preconscious or not. Also ocular-motor skill. n n Doesn’t address looping/cascading. In spite of Q’s more accurate predictions for some tasks than purely serial models.

What cognitive modeling (serial & parallel) has not revealed n n n How we move from skilled to unskilled tasks smoothly throughout the day. Learning: “Athough we know that consistency in a system may make that system easier to learn … and easier to operate…, we do not know much more than that. ” Errors: More than overloading working memory Individual differences in HCI Fatigue and other stress factors: machines don’t tire or get stressed out; people do.

From GOMS to Games n n Prior studies based on static visual display of text and numbers. Bonnie John & Alonso Vera extended GOMS model to more interactive HCI’s -video games, call handling, & browsing. Subject: 9 year-old expert Result – 2 levels: GOMS predicts functional interaction well n Keystroke accuracy ~ 50% n n Program (HI-SOAR) learns ~ humans

Conclusion n GOMS and its successors are useful for many repetitive HCI tasks – bank tellers, ATM’s, airline reservations, bookkeeping… Cognitive modeling saves $ + time less need to build and test prototypes on users when models can predict results. n User testing still needed for reality check – “situated cognition” = understanding tasks in their human and environmental context.

(Start of extra slides) n

Learning Computer Tasks n n n Limitation of GOMS: Restricted to skilled performance. Didn’t address learning. Cognitive Complexity Theory (Kieras & Polson) 2 aspects of their learning model: Time to learn a new system or task n Transferring knowledge between tasks n

Time to Learn n Kieras developed a high-level programming language to describe learning simple computer tasks, like data entry or writing an SQL query. Keiras & Polson found learning each step of a task takes ~ 30 s. Other studies found shorter times. Current best guess ~ 25 s. /step for learning.

Learning & Complexity n n Number of rules to learn is not as important how well the rules follow realworld features the learner already knows. Implication: Metaphors work, as long as they are consistent.

Learning Computer Tasks (1): Theory n n K & P’s production rules make explicit exactly what a person has to learn to master a new system. Hypothesis: If # of productions (~steps) is a measure of how long it takes to learn, then 2 systems with same # of productions should take same time to learn.

Learning Computer Tasks (2): Studies n Example: Compare time it takes to learn: How to copy a floppy n How to print a document n n n Result: Learning times are consistent across systems. Value: When designing systems, favor alternatives with simpler production rules (easier to learn!)

Philosophical Critique of GOMS n n n Does it reduce human to machine? Answer: Not intended to address philosophy. Only intended to aid in system design. Bottom line: Predictions average within 14% of observed values for a narrow range of serial tasks.

Practical Critiques of GOMS n n n Restricted to skilled performance Doesn’t predict learning Doesn’t apply to parallel tasks

Extensions to Basic GOMS Framework n n Purpose: Less restrictive framework for understanding HCI. 3 areas of analysis since GOMS: 1. 2. 3. Learning Errors Parallel processes

Cognitive Engineering Grammars n n Purpose: Define cognitive tasks in terms of countable components for production rules. Example: Task-Action Grammar (TAG) Commands, e. g. “Left-click, ” “press <enter>” n Features of goal, e. g. direction of cursor n Tasks, e. g. , “Add 3 numbers. ” n Rules to translate goals into action. n