The Glassy State and the Glass Transition Pconst

- Slides: 33

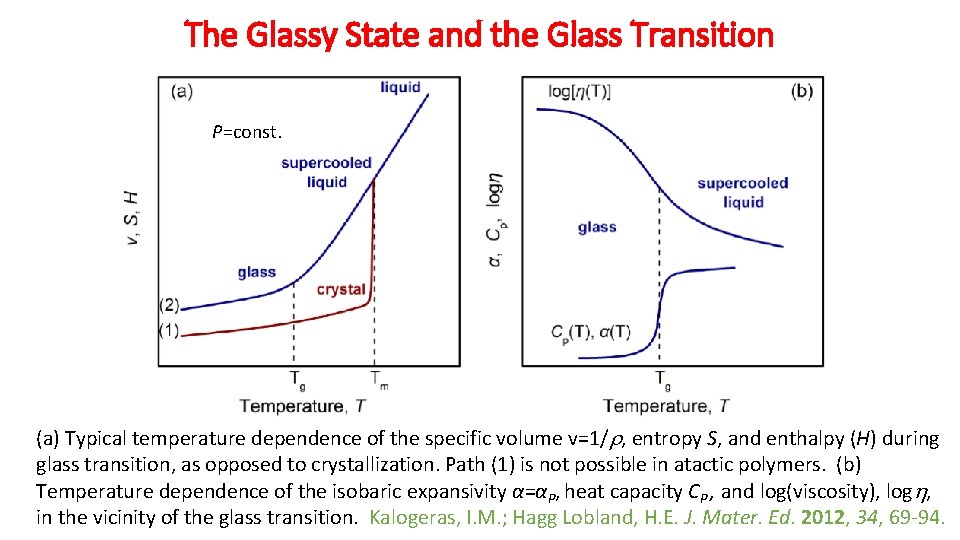

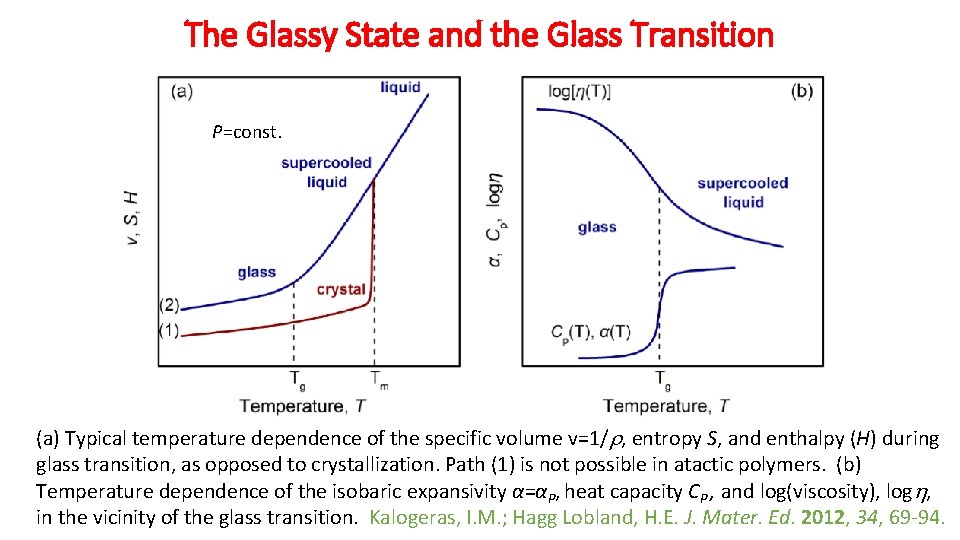

The Glassy State and the Glass Transition P=const. (a) Typical temperature dependence of the specific volume v=1/ , entropy S, and enthalpy (H) during glass transition, as opposed to crystallization. Path (1) is not possible in atactic polymers. (b) Temperature dependence of the isobaric expansivity α=αP, heat capacity CP , and log(viscosity), log , in the vicinity of the glass transition. Kalogeras, I. M. ; Hagg Lobland, H. E. J. Mater. Ed. 2012, 34, 69 -94.

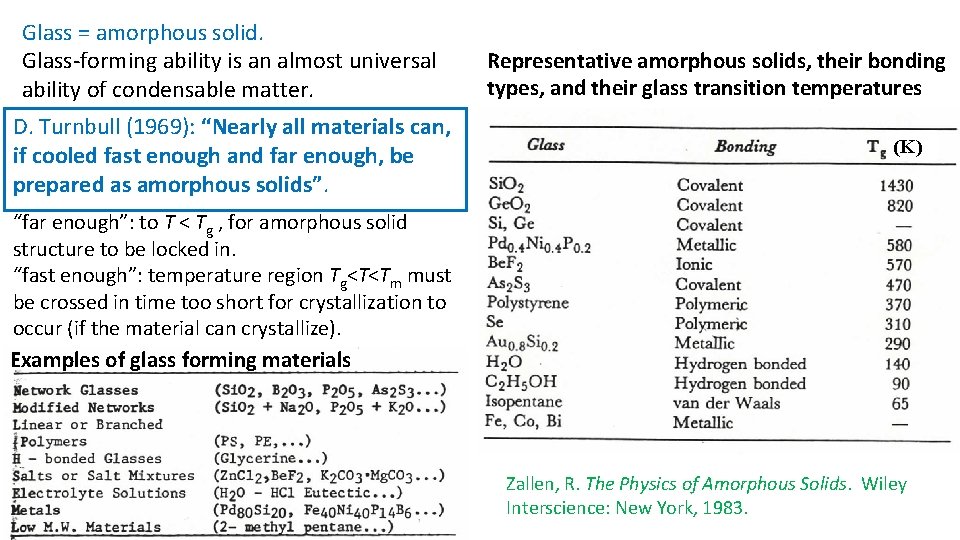

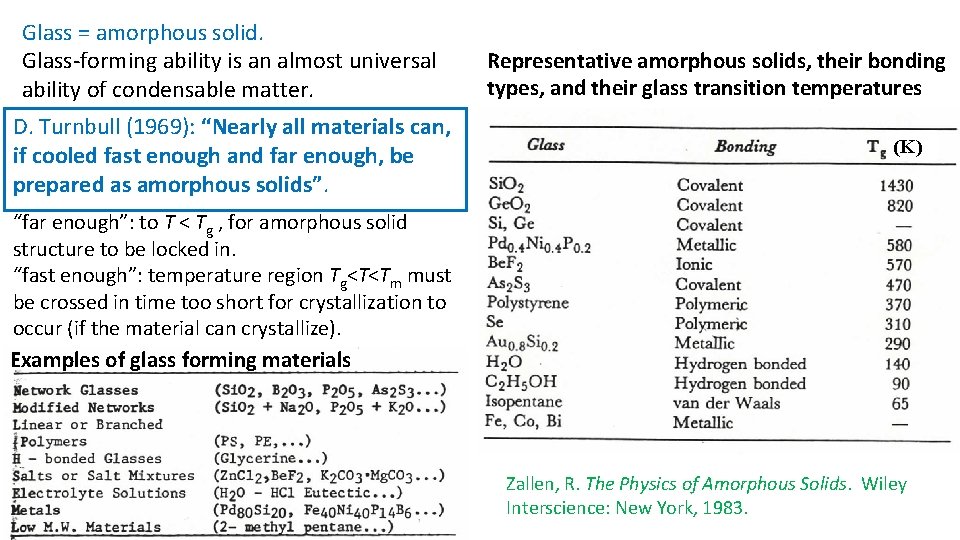

Glass = amorphous solid. Glass-forming ability is an almost universal ability of condensable matter. D. Turnbull (1969): “Nearly all materials can, if cooled fast enough and far enough, be prepared as amorphous solids”. Representative amorphous solids, their bonding types, and their glass transition temperatures (K) “far enough”: to T < Tg , for amorphous solid structure to be locked in. “fast enough”: temperature region Tg<T<Tm must be crossed in time too short for crystallization to occur (if the material can crystallize). Examples of glass forming materials Zallen, R. The Physics of Amorphous Solids. Wiley Interscience: New York, 1983.

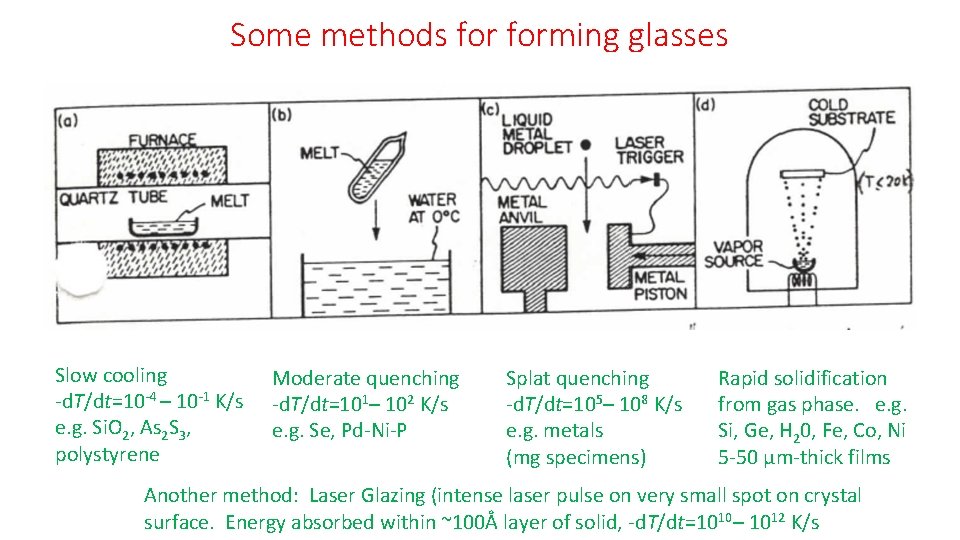

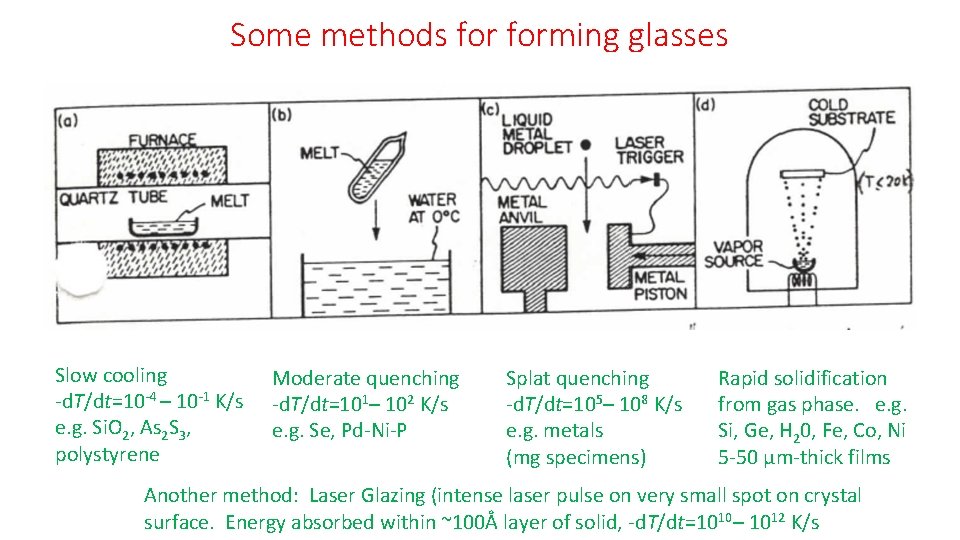

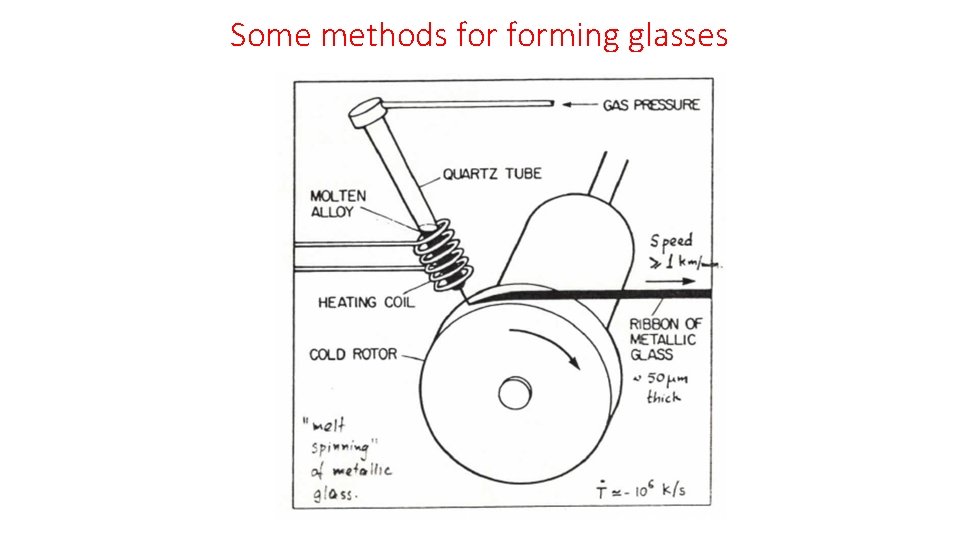

Some methods forming glasses Slow cooling -d. T/dt=10 -4 – 10 -1 K/s e. g. Si. O 2, As 2 S 3, polystyrene Moderate quenching -d. T/dt=101– 102 K/s e. g. Se, Pd-Ni-P Splat quenching -d. T/dt=105– 108 K/s e. g. metals (mg specimens) Rapid solidification from gas phase. e. g. Si, Ge, H 20, Fe, Co, Ni 5 -50 μm-thick films Another method: Laser Glazing (intense laser pulse on very small spot on crystal surface. Energy absorbed within ~100Å layer of solid, -d. T/dt=1010– 1012 K/s

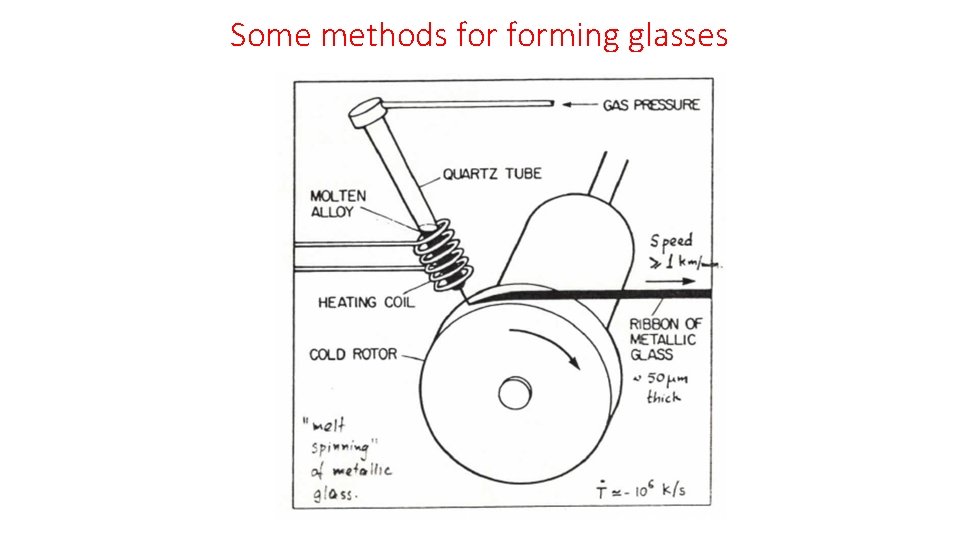

Some methods forming glasses

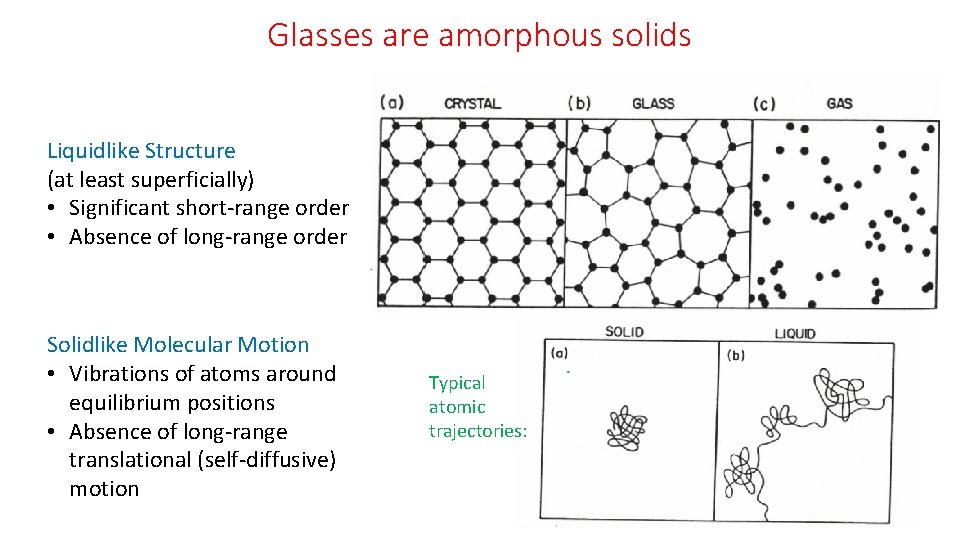

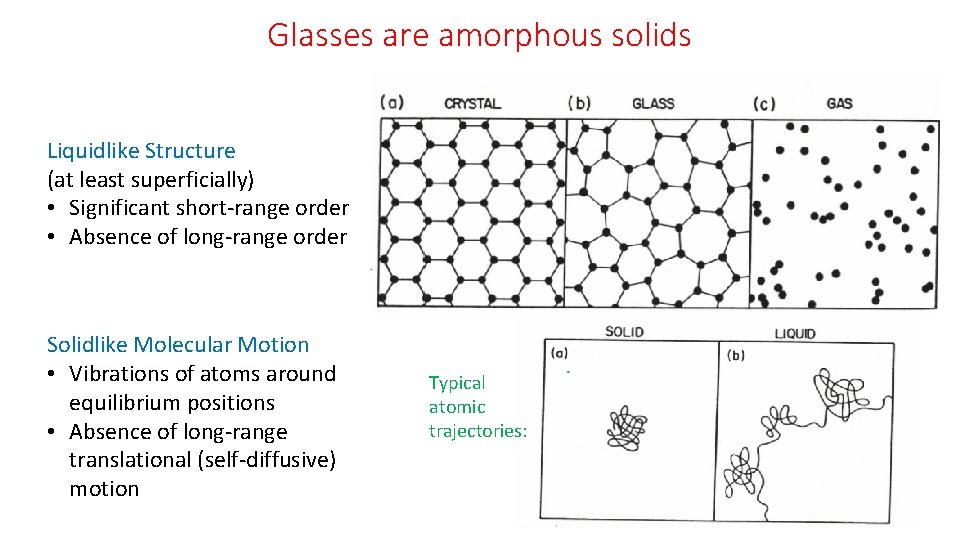

Glasses are amorphous solids Liquidlike Structure (at least superficially) • Significant short-range order • Absence of long-range order Solidlike Molecular Motion • Vibrations of atoms around equilibrium positions • Absence of long-range translational (self-diffusive) motion Typical atomic trajectories:

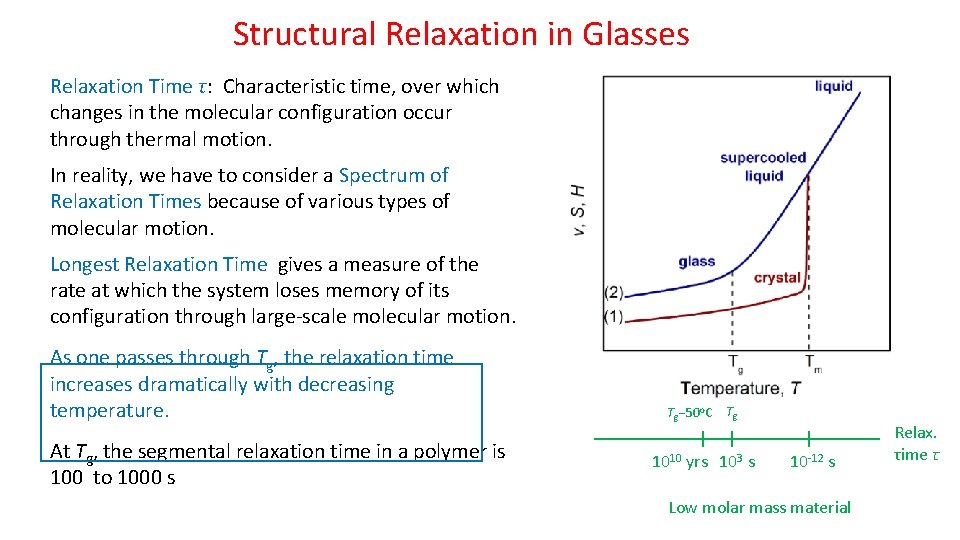

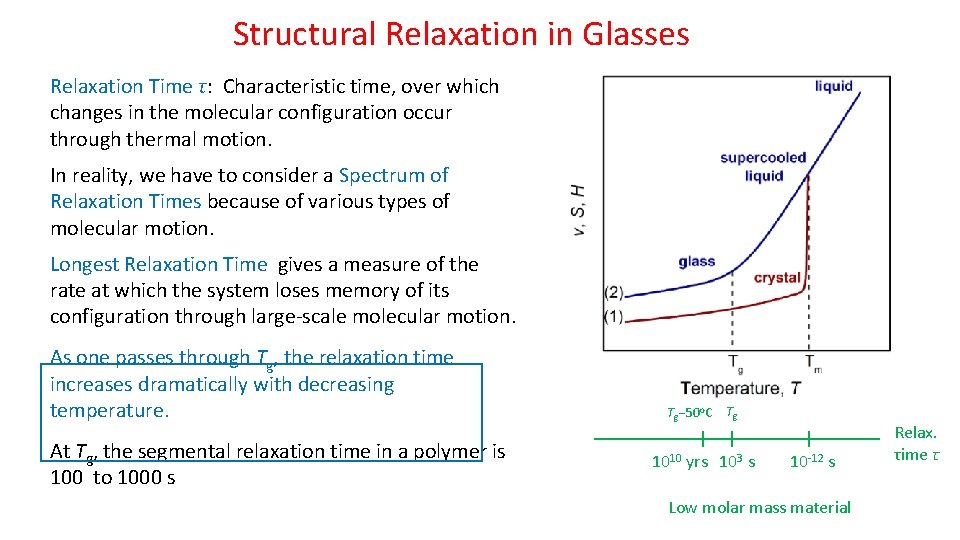

Structural Relaxation in Glasses Relaxation Time τ: Characteristic time, over which changes in the molecular configuration occur through thermal motion. In reality, we have to consider a Spectrum of Relaxation Times because of various types of molecular motion. Longest Relaxation Time gives a measure of the rate at which the system loses memory of its configuration through large-scale molecular motion. As one passes through Tg, the relaxation time increases dramatically with decreasing temperature. At Tg, the segmental relaxation time in a polymer is 100 to 1000 s Tg 50 o. C Tg 1010 yrs 103 s 10 -12 s Low molar mass material Relax. τime τ

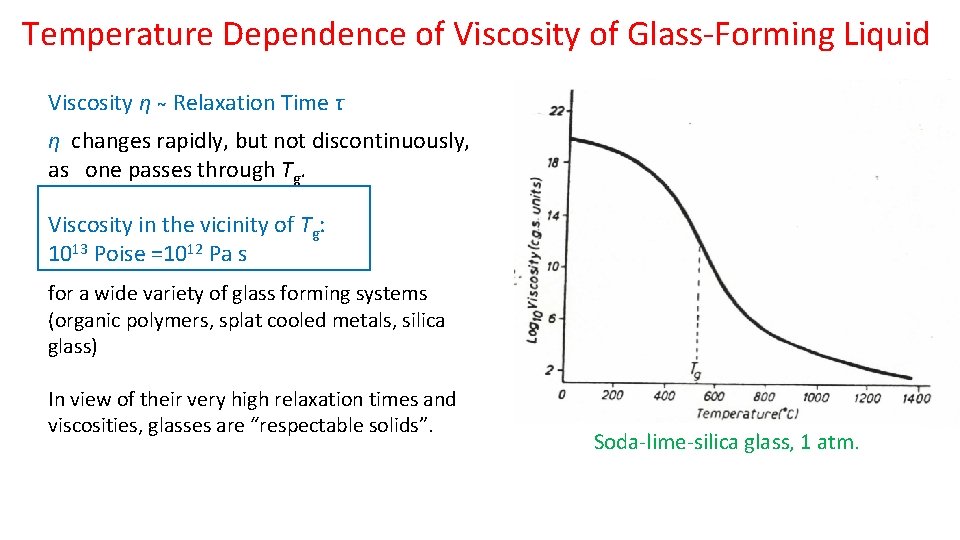

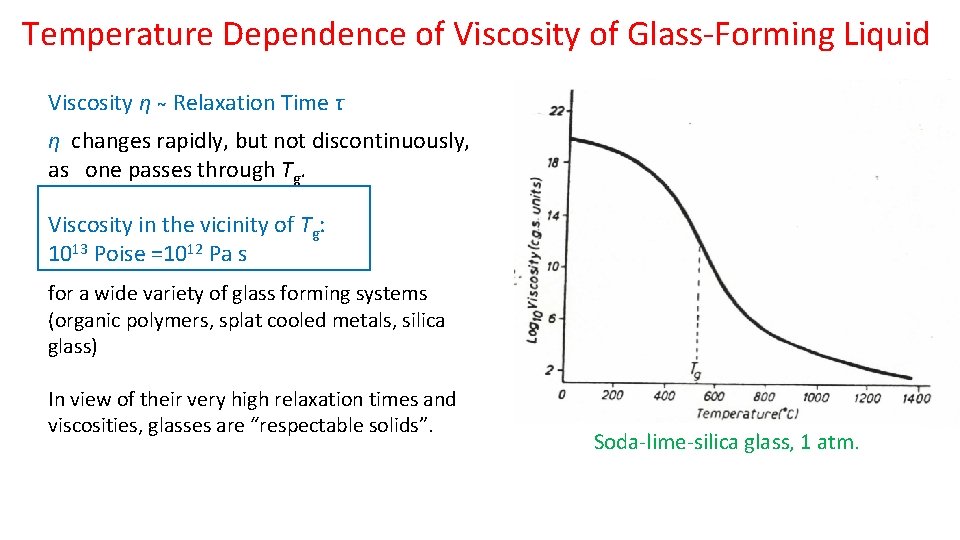

Temperature Dependence of Viscosity of Glass-Forming Liquid Viscosity η Relaxation Time τ η changes rapidly, but not discontinuously, as one passes through Tg. Viscosity in the vicinity of Tg: 1013 Poise =1012 Pa s for a wide variety of glass forming systems (organic polymers, splat cooled metals, silica glass) In view of their very high relaxation times and viscosities, glasses are “respectable solids”. Soda-lime-silica glass, 1 atm.

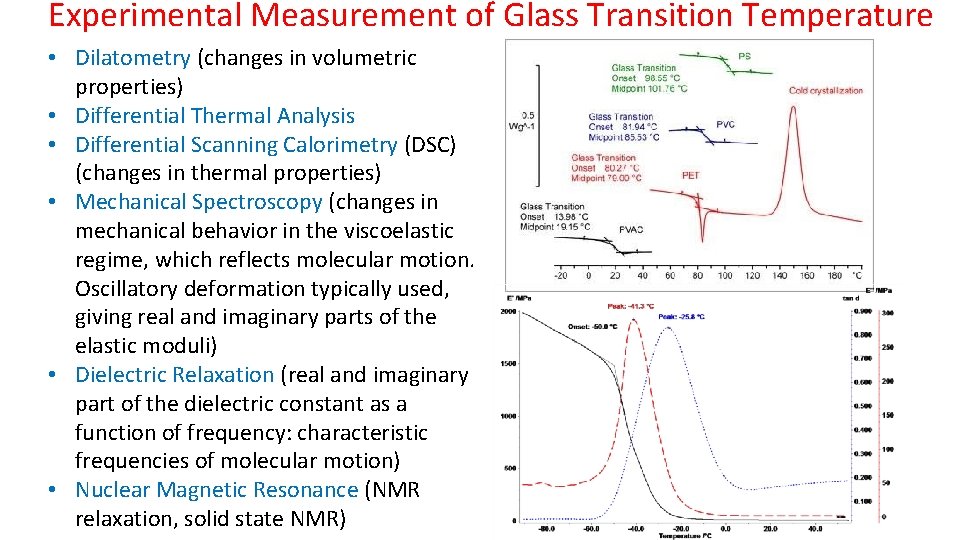

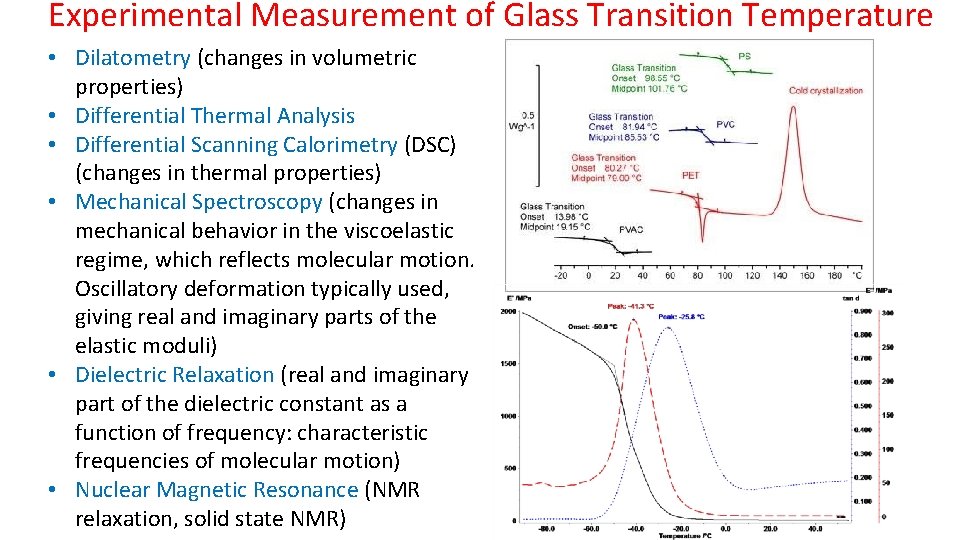

Experimental Measurement of Glass Transition Temperature • Dilatometry (changes in volumetric properties) • Differential Thermal Analysis • Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) (changes in thermal properties) • Mechanical Spectroscopy (changes in mechanical behavior in the viscoelastic regime, which reflects molecular motion. Oscillatory deformation typically used, giving real and imaginary parts of the elastic moduli) • Dielectric Relaxation (real and imaginary part of the dielectric constant as a function of frequency: characteristic frequencies of molecular motion) • Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR relaxation, solid state NMR)

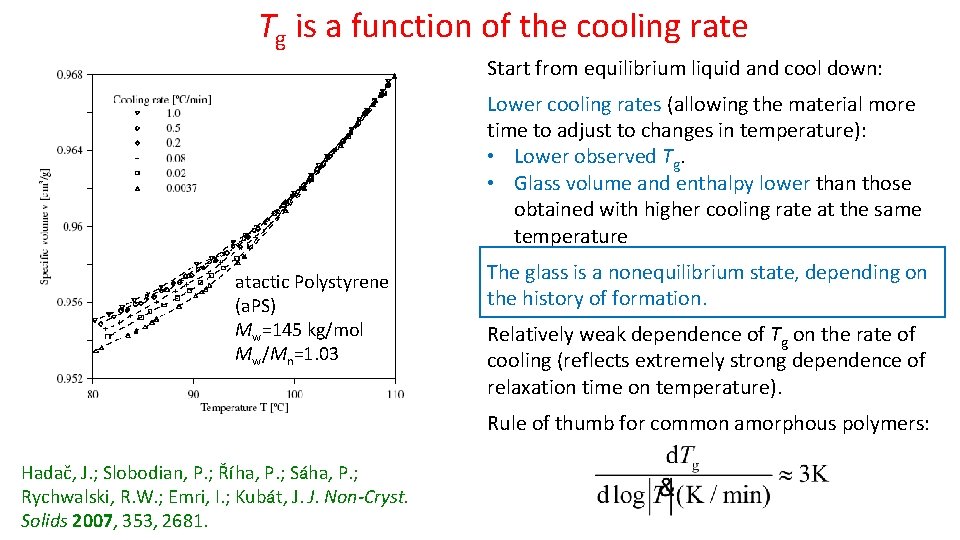

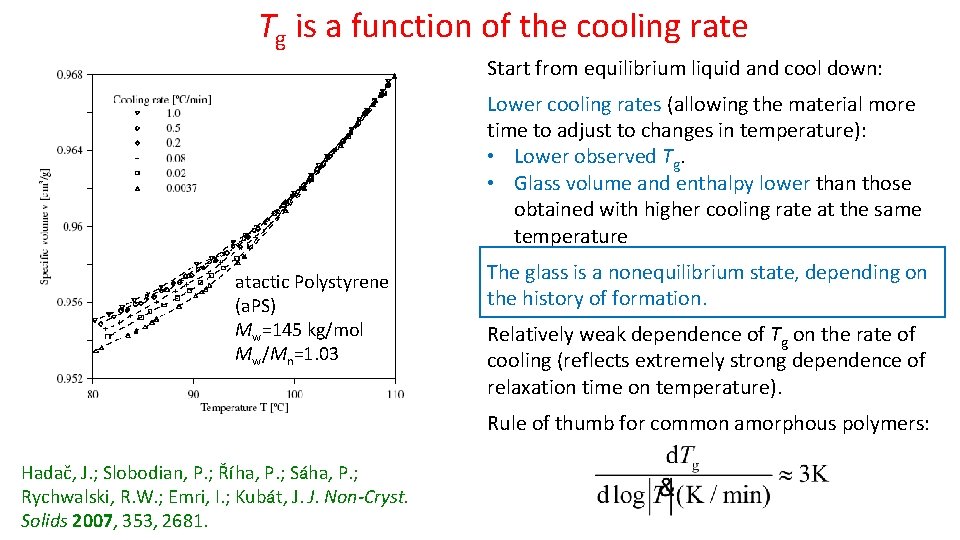

Tg is a function of the cooling rate Start from equilibrium liquid and cool down: Lower cooling rates (allowing the material more time to adjust to changes in temperature): • Lower observed Tg. • Glass volume and enthalpy lower than those obtained with higher cooling rate at the same temperature atactic Polystyrene (a. PS) Mw=145 kg/mol Mw/Mn=1. 03 The glass is a nonequilibrium state, depending on the history of formation. Relatively weak dependence of Tg on the rate of cooling (reflects extremely strong dependence of relaxation time on temperature). Rule of thumb for common amorphous polymers: Hadač, J. ; Slobodian, P. ; Říha, P. ; Sáha, P. ; Rychwalski, R. W. ; Emri, I. ; Kubát, J. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2007, 353, 2681.

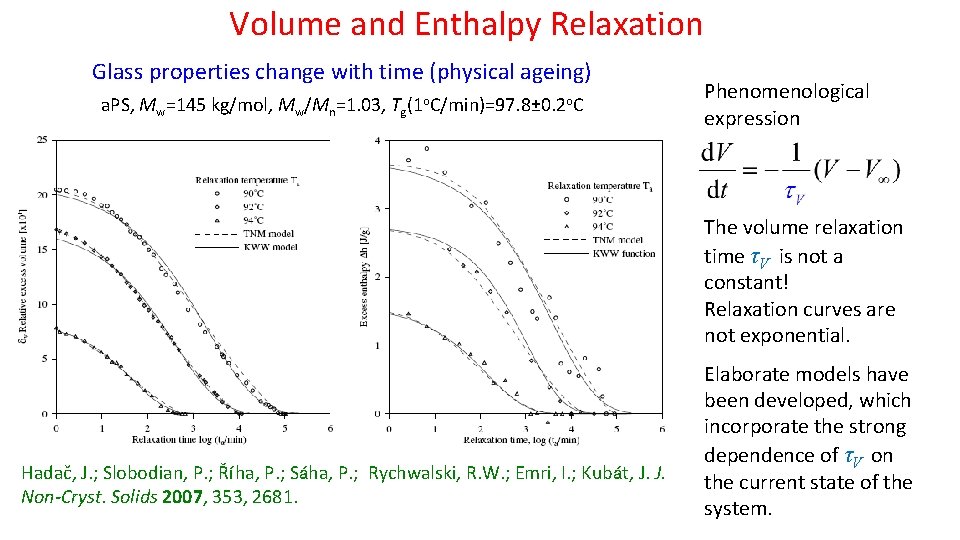

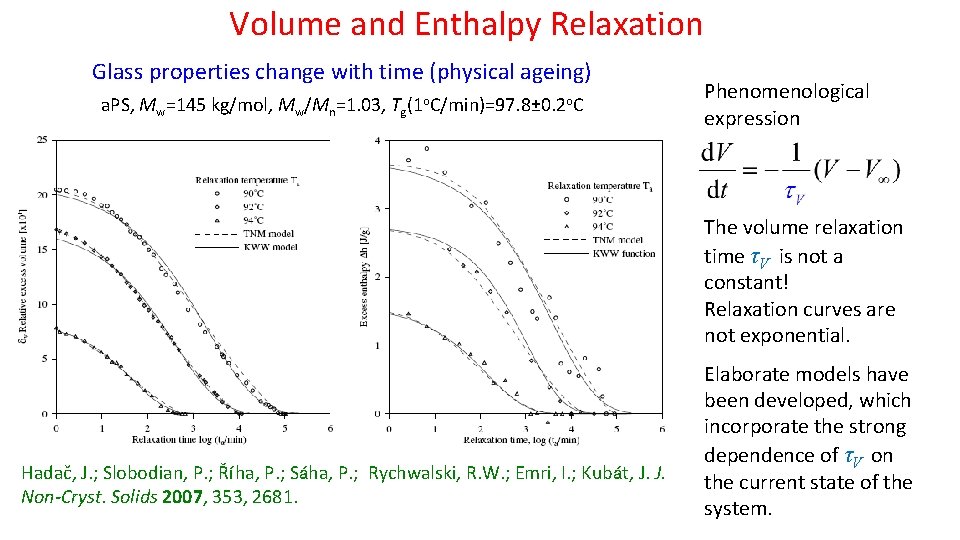

Volume and Enthalpy Relaxation Glass properties change with time (physical ageing) a. PS, Mw=145 kg/mol, Mw/Mn=1. 03, Tg(1 o. C/min)=97. 8± 0. 2 o. C Phenomenological expression The volume relaxation time τV is not a constant! Relaxation curves are not exponential. Hadač, J. ; Slobodian, P. ; Říha, P. ; Sáha, P. ; Rychwalski, R. W. ; Emri, I. ; Kubát, J. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2007, 353, 2681. Elaborate models have been developed, which incorporate the strong dependence of τV on the current state of the system.

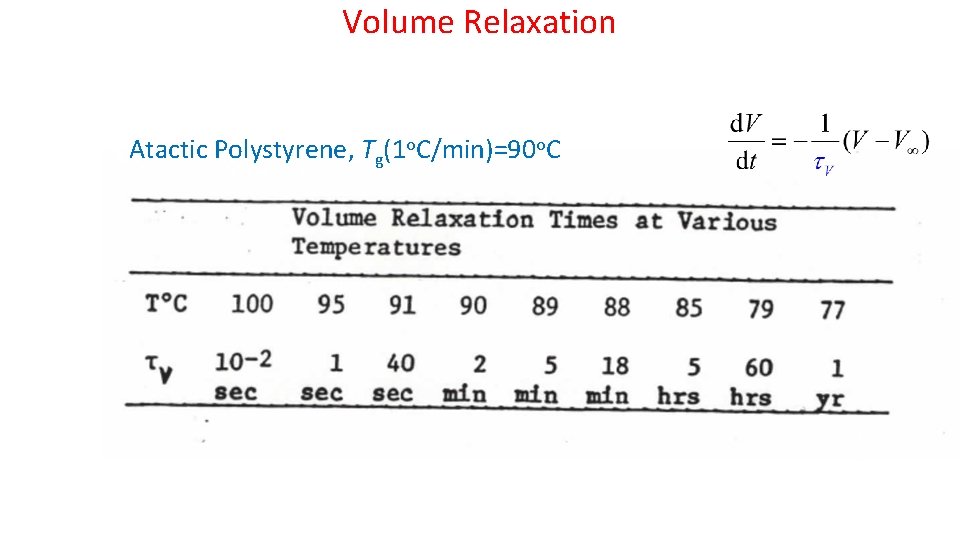

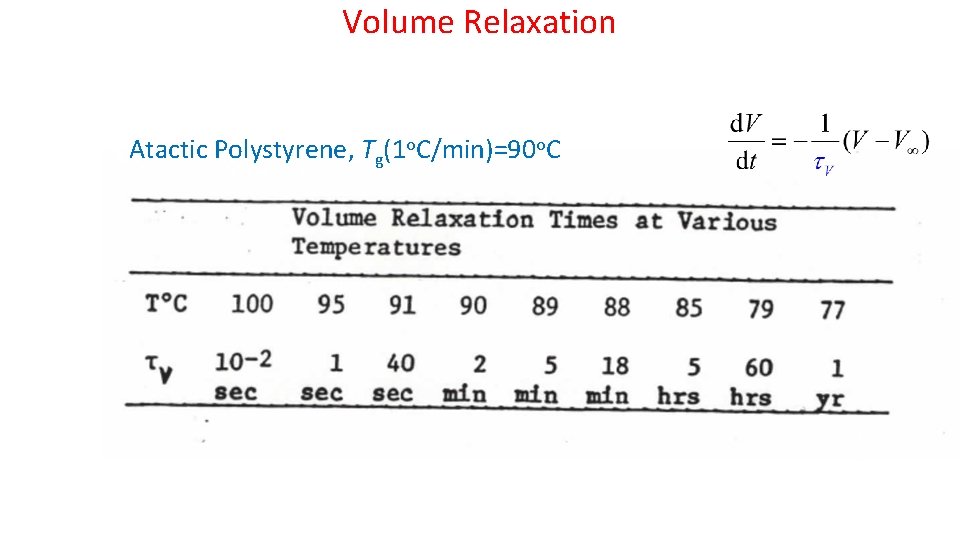

Volume Relaxation Atactic Polystyrene, Tg(1 o. C/min)=90 o. C

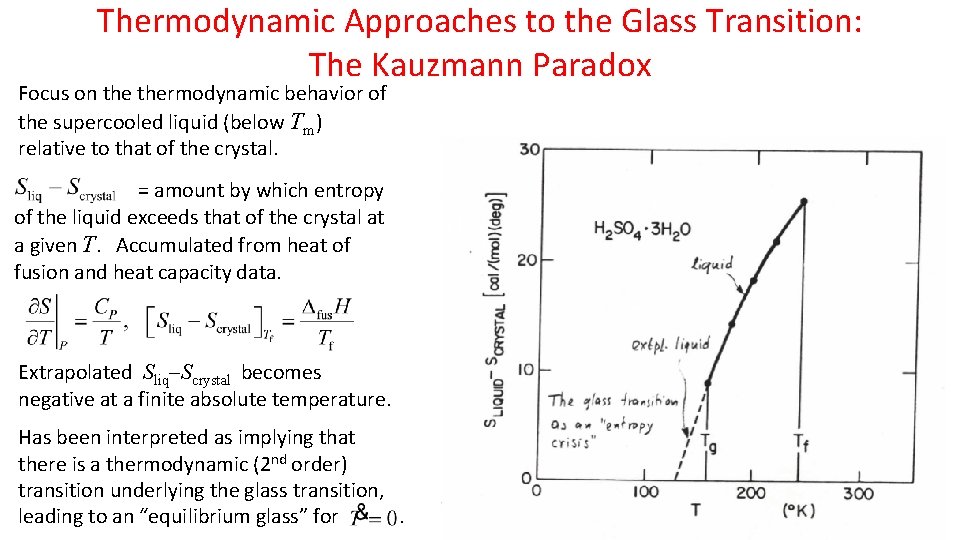

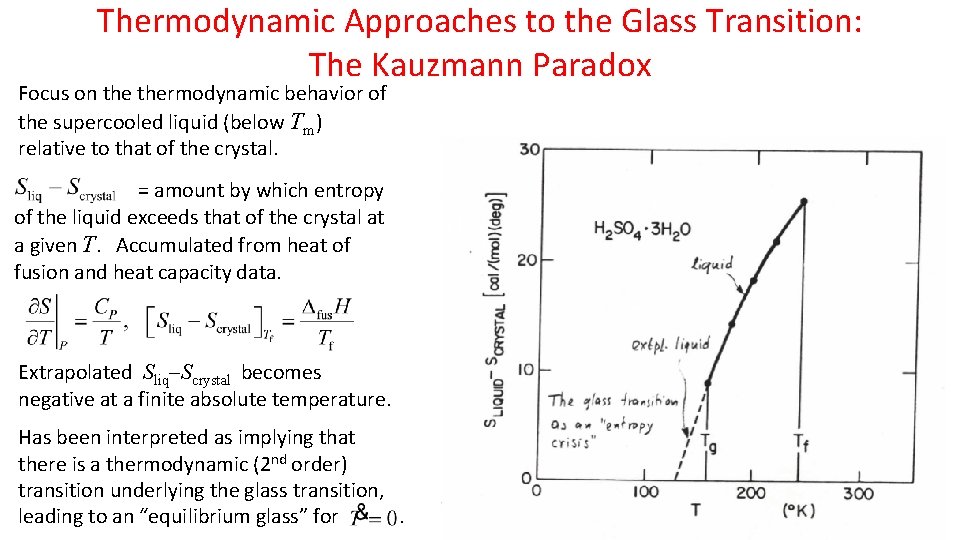

Thermodynamic Approaches to the Glass Transition: The Kauzmann Paradox Focus on thermodynamic behavior of the supercooled liquid (below Tm) relative to that of the crystal. = amount by which entropy of the liquid exceeds that of the crystal at a given T. Accumulated from heat of fusion and heat capacity data. Extrapolated Sliq Scrystal becomes negative at a finite absolute temperature. Has been interpreted as implying that there is a thermodynamic (2 nd order) transition underlying the glass transition, leading to an “equilibrium glass” for.

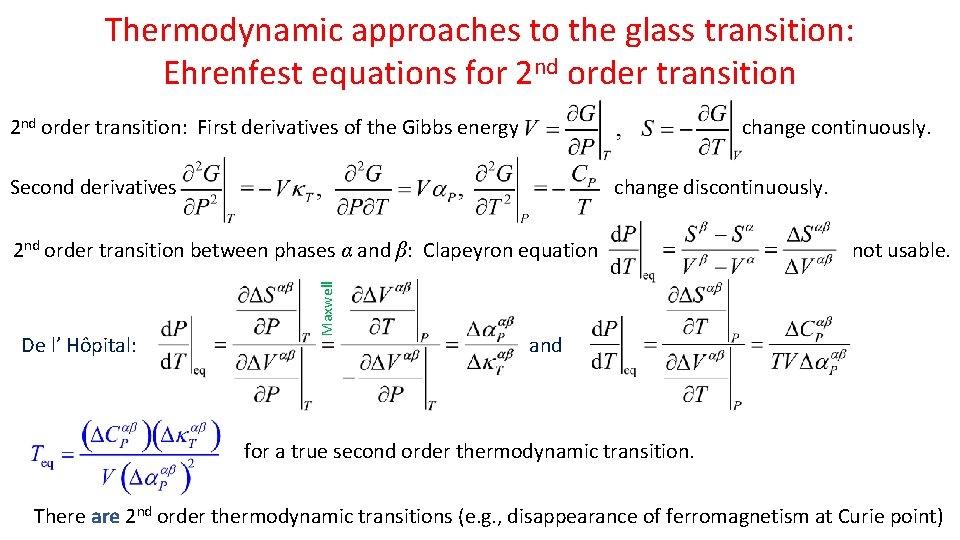

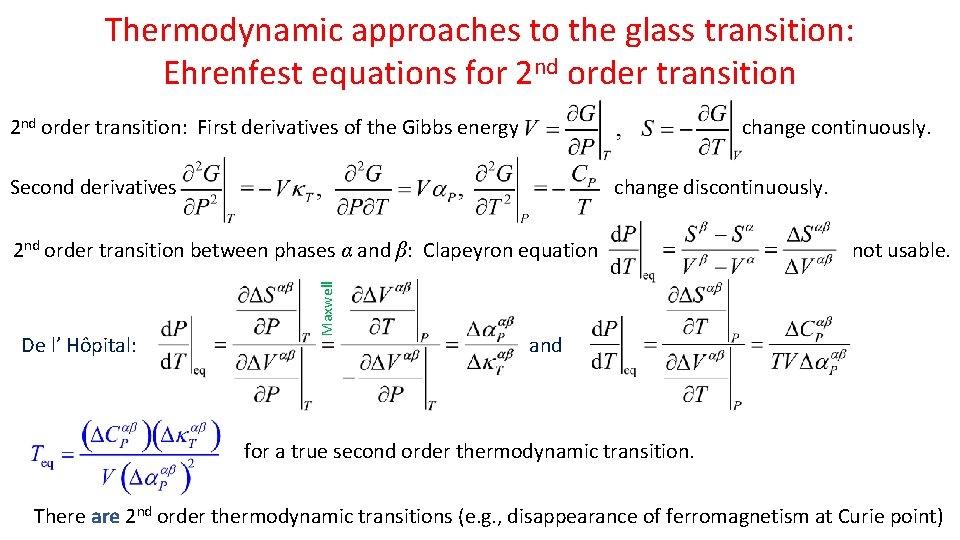

Thermodynamic approaches to the glass transition: Ehrenfest equations for 2 nd order transition: First derivatives of the Gibbs energy change continuously. Second derivatives change discontinuously. De l’ Hôpital: Maxwell 2 nd order transition between phases α and β: Clapeyron equation not usable. and for a true second order thermodynamic transition. There are 2 nd order thermodynamic transitions (e. g. , disappearance of ferromagnetism at Curie point)

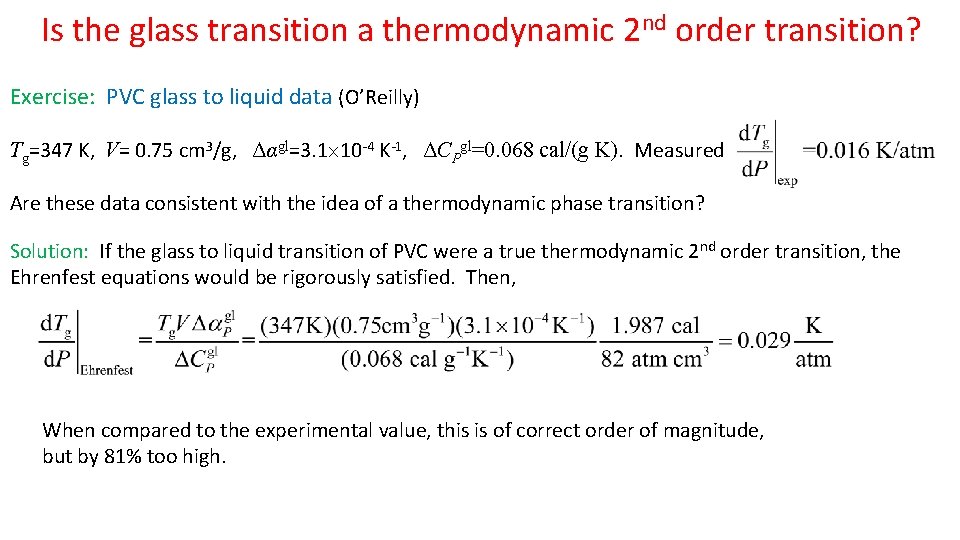

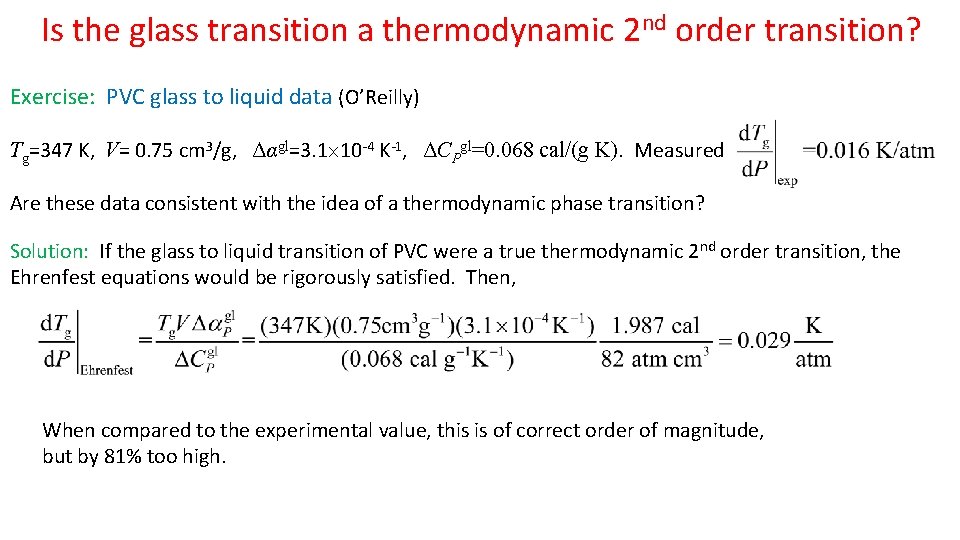

Is the glass transition a thermodynamic 2 nd order transition? Exercise: PVC glass to liquid data (O’Reilly) Tg=347 K, V= 0. 75 cm 3/g, Δαgl=3. 1 10 -4 K-1, ΔCPgl=0. 068 cal/(g K). Measured Are these data consistent with the idea of a thermodynamic phase transition? Solution: If the glass to liquid transition of PVC were a true thermodynamic 2 nd order transition, the Ehrenfest equations would be rigorously satisfied. Then, When compared to the experimental value, this is of correct order of magnitude, but by 81% too high.

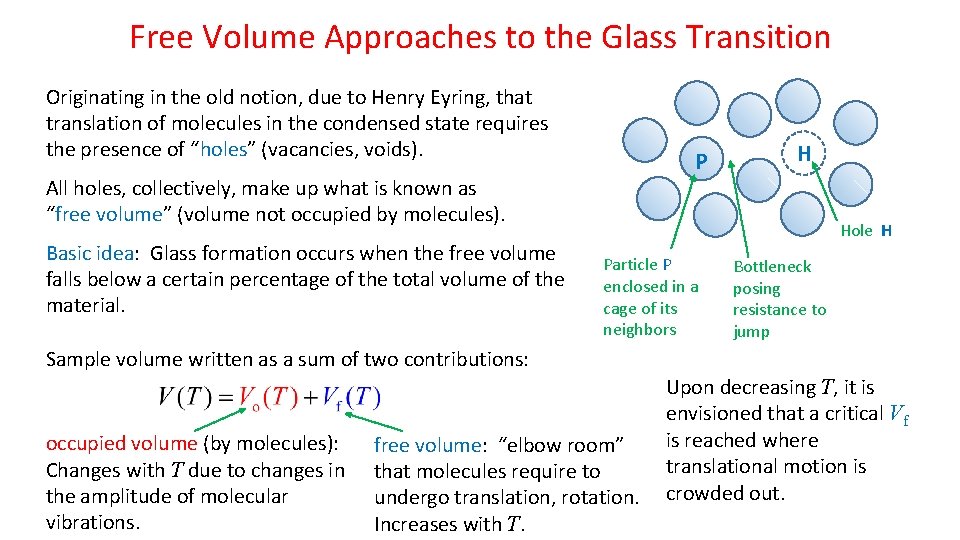

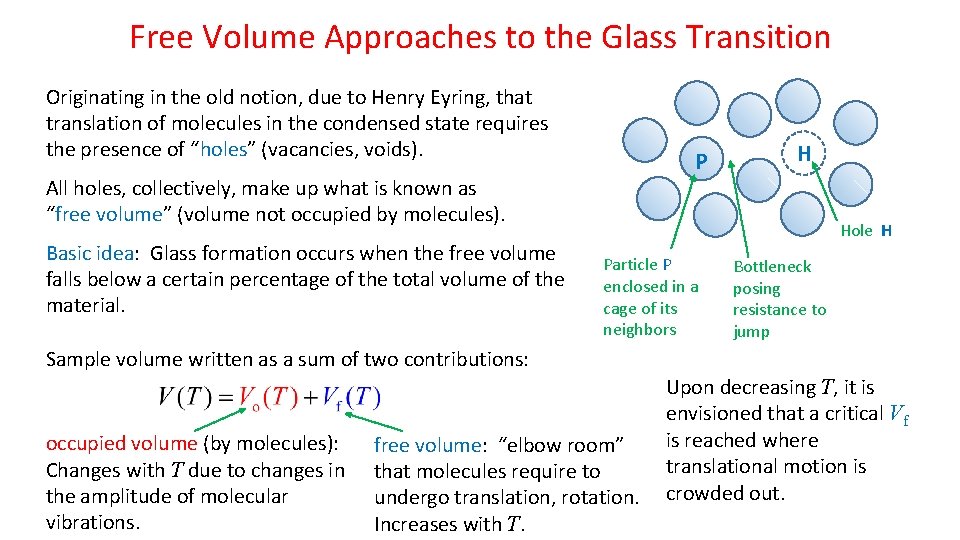

Free Volume Approaches to the Glass Transition Originating in the old notion, due to Henry Eyring, that translation of molecules in the condensed state requires the presence of “holes” (vacancies, voids). P All holes, collectively, make up what is known as “free volume” (volume not occupied by molecules). Basic idea: Glass formation occurs when the free volume falls below a certain percentage of the total volume of the material. H Hole H Particle P enclosed in a cage of its neighbors Bottleneck posing resistance to jump Sample volume written as a sum of two contributions: occupied volume (by molecules): Changes with T due to changes in the amplitude of molecular vibrations. free volume: “elbow room” that molecules require to undergo translation, rotation. Increases with T. Upon decreasing T, it is envisioned that a critical Vf is reached where translational motion is crowded out.

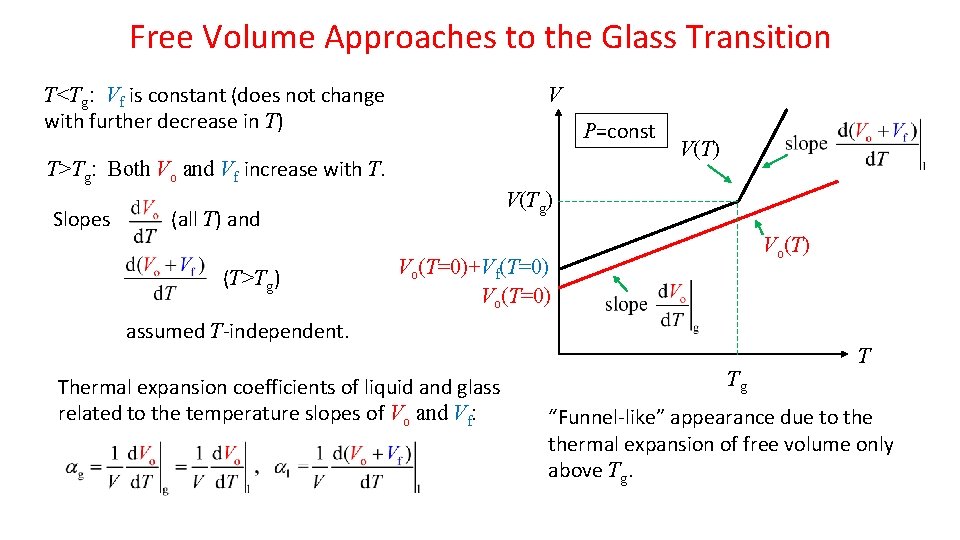

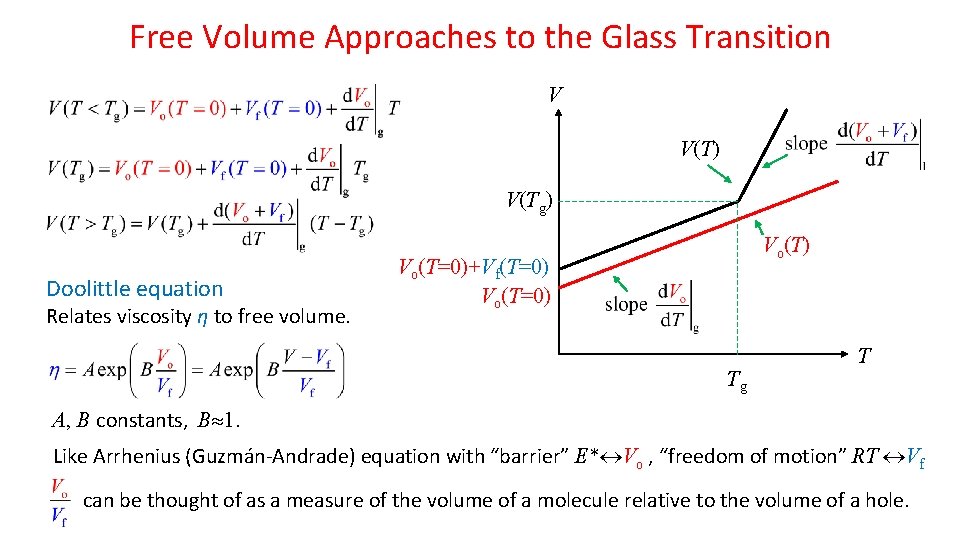

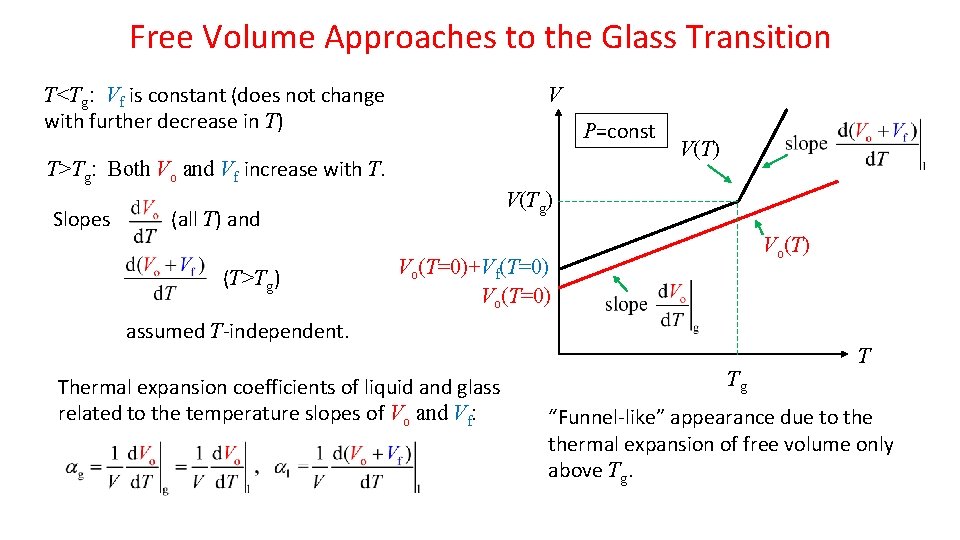

Free Volume Approaches to the Glass Transition T<Tg: Vf is constant (does not change with further decrease in T) V P=const T>Tg: Both Vo and Vf increase with T. Slopes V(Tg) (all T) and (T>Tg) V(T) Vo(T=0)+Vf(T=0) Vo(T=0) assumed T-independent. Thermal expansion coefficients of liquid and glass related to the temperature slopes of Vo and Vf: Tg T “Funnel-like” appearance due to thermal expansion of free volume only above Tg.

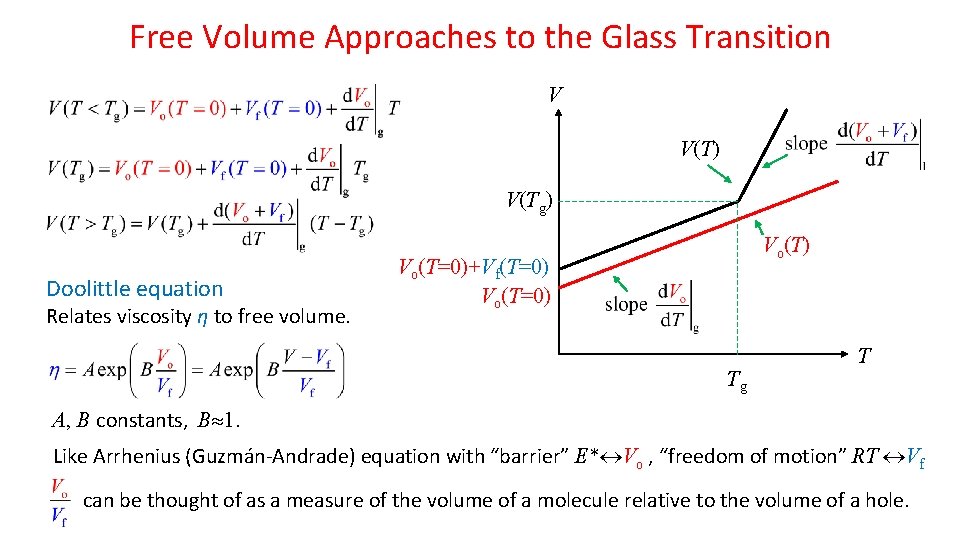

Free Volume Approaches to the Glass Transition V V(T) V(Tg) Doolittle equation Relates viscosity η to free volume. Vo(T) Vo(T=0)+Vf(T=0) Vo(T=0) Tg T A, B constants, B 1. Like Arrhenius (Guzmán-Andrade) equation with “barrier” E* Vo , “freedom of motion” RT Vf can be thought of as a measure of the volume of a molecule relative to the volume of a hole.

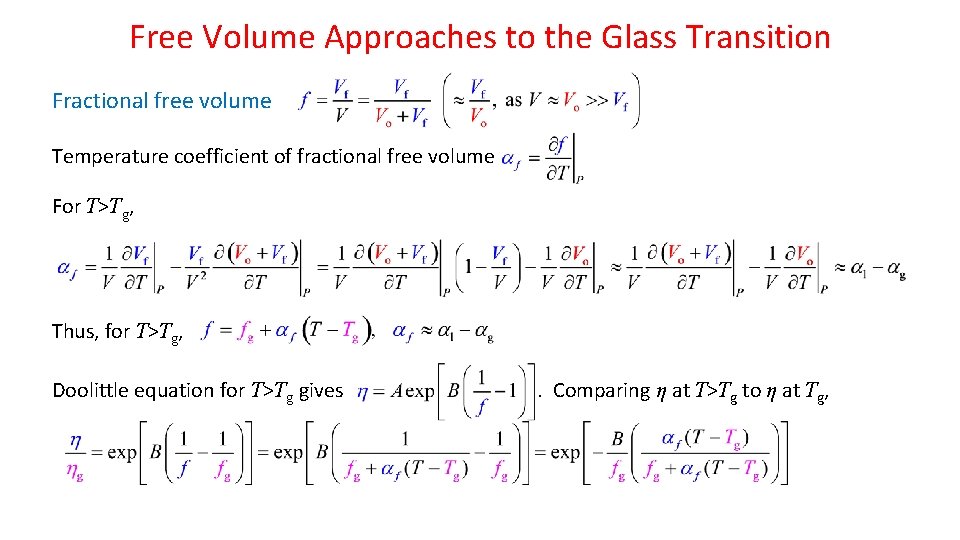

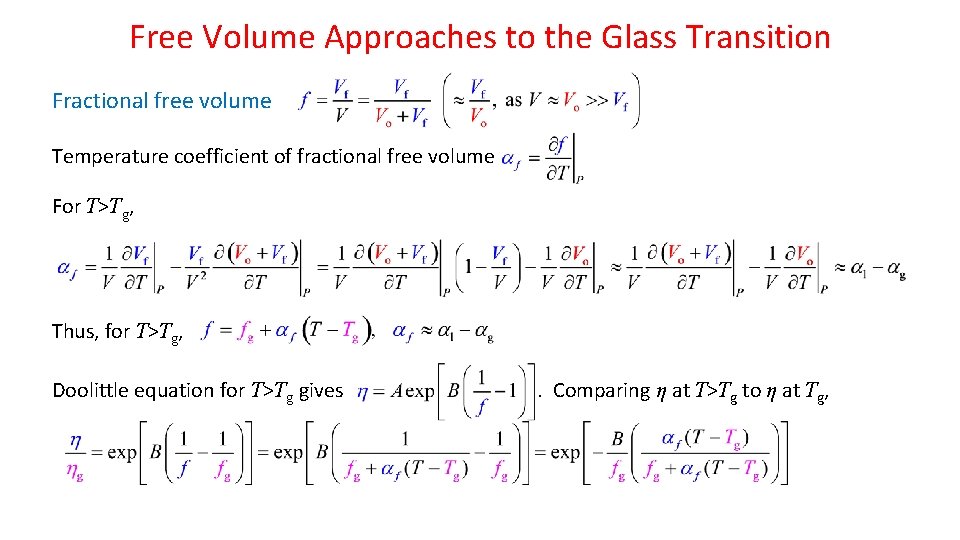

Free Volume Approaches to the Glass Transition Fractional free volume Temperature coefficient of fractional free volume For T>Tg, Thus, for T>Tg, Doolittle equation for T>Tg gives . Comparing η at T>Tg to η at Tg,

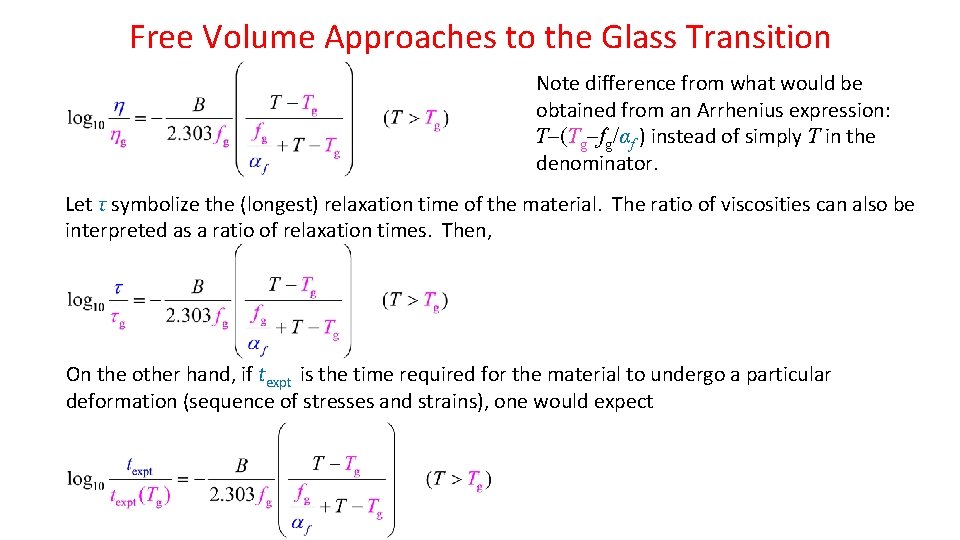

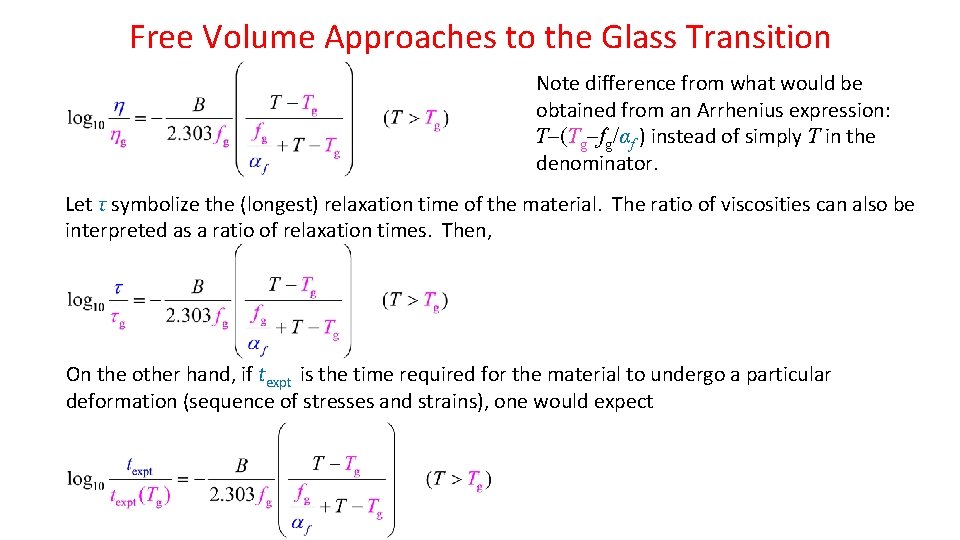

Free Volume Approaches to the Glass Transition Note difference from what would be obtained from an Arrhenius expression: T (Tg fg/αf ) instead of simply T in the denominator. Let τ symbolize the (longest) relaxation time of the material. The ratio of viscosities can also be interpreted as a ratio of relaxation times. Then, On the other hand, if texpt is the time required for the material to undergo a particular deformation (sequence of stresses and strains), one would expect

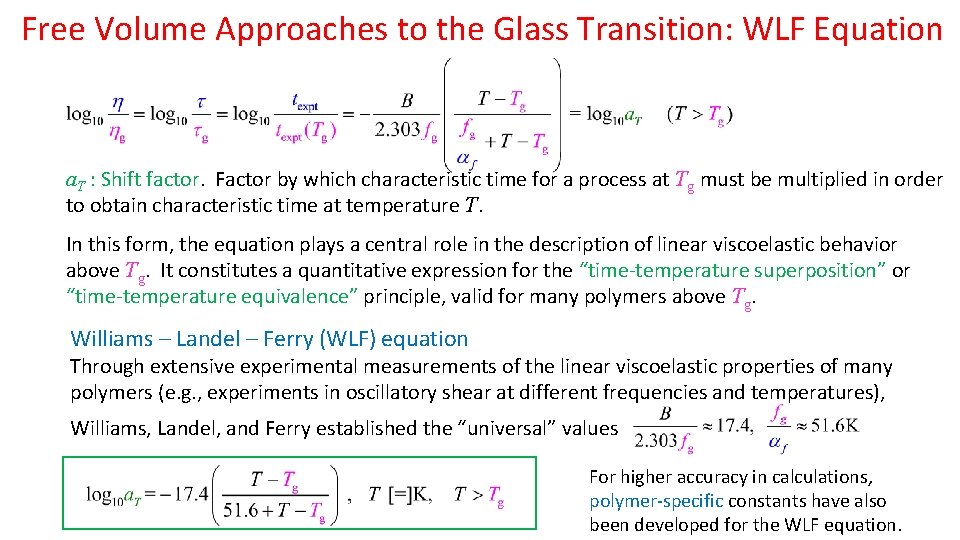

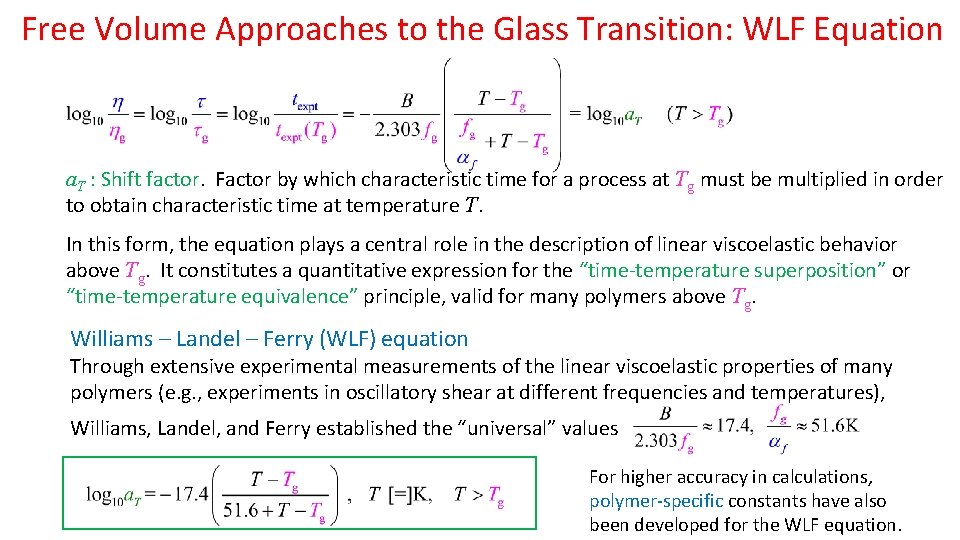

Free Volume Approaches to the Glass Transition: WLF Equation a. T : Shift factor. Factor by which characteristic time for a process at Tg must be multiplied in order to obtain characteristic time at temperature T. In this form, the equation plays a central role in the description of linear viscoelastic behavior above Tg. It constitutes a quantitative expression for the “time-temperature superposition” or “time-temperature equivalence” principle, valid for many polymers above Tg. Williams – Landel – Ferry (WLF) equation Through extensive experimental measurements of the linear viscoelastic properties of many polymers (e. g. , experiments in oscillatory shear at different frequencies and temperatures), Williams, Landel, and Ferry established the “universal” values For higher accuracy in calculations, polymer-specific constants have also been developed for the WLF equation.

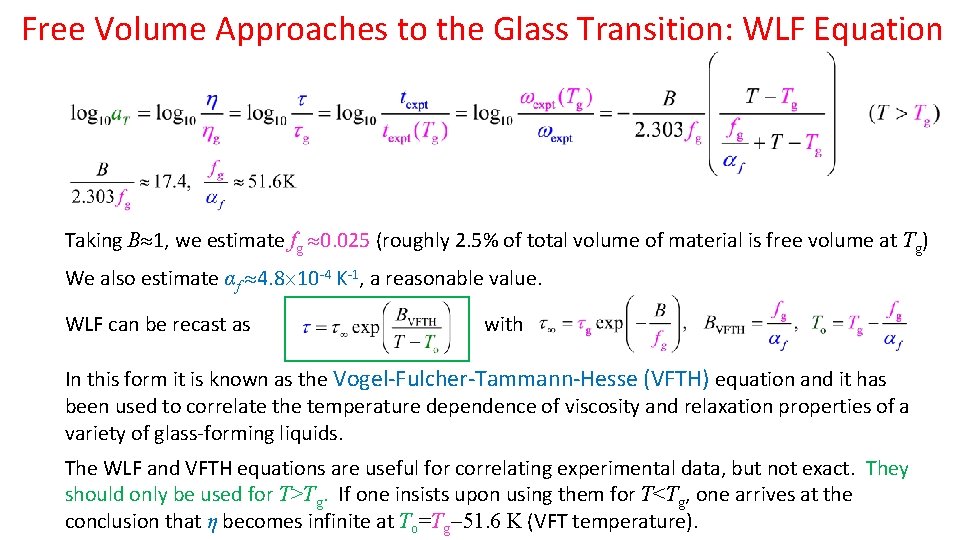

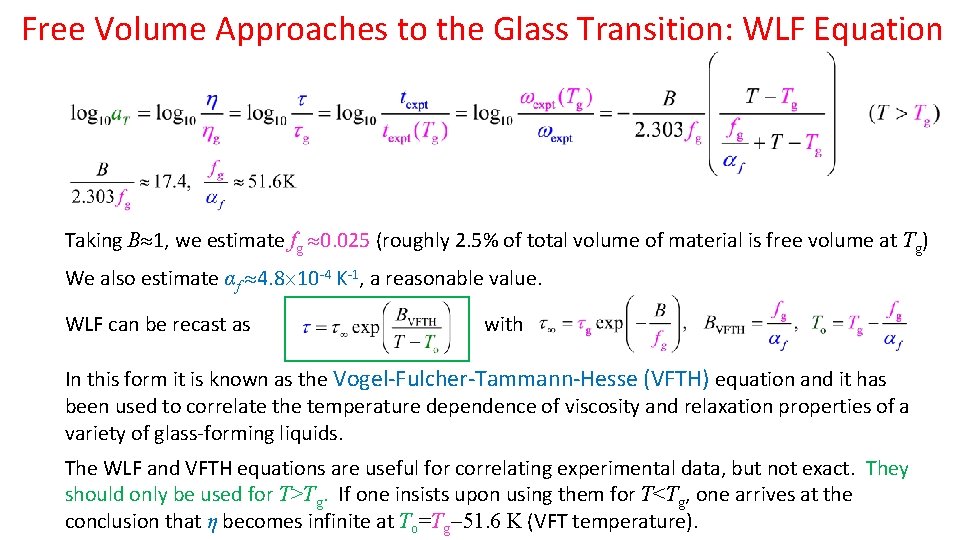

Free Volume Approaches to the Glass Transition: WLF Equation Taking B 1, we estimate fg 0. 025 (roughly 2. 5% of total volume of material is free volume at Tg) We also estimate αf 4. 8 10 -4 Κ-1, a reasonable value. WLF can be recast as with In this form it is known as the Vogel-Fulcher-Tammann-Hesse (VFTH) equation and it has been used to correlate the temperature dependence of viscosity and relaxation properties of a variety of glass-forming liquids. The WLF and VFTH equations are useful for correlating experimental data, but not exact. They should only be used for T>Tg. If one insists upon using them for T<Tg, one arrives at the conclusion that η becomes infinite at To=Tg 51. 6 K (VFT temperature).

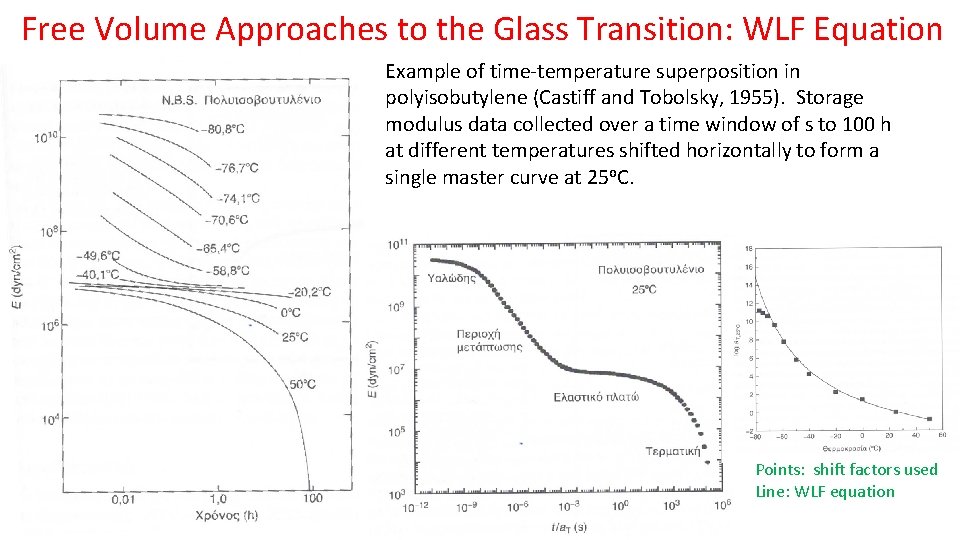

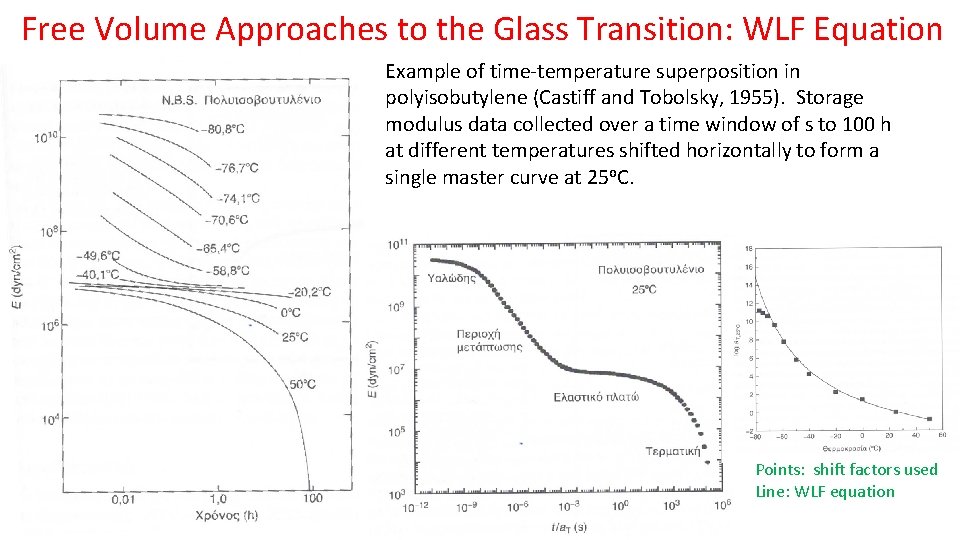

Free Volume Approaches to the Glass Transition: WLF Equation Example of time-temperature superposition in polyisobutylene (Castiff and Tobolsky, 1955). Storage modulus data collected over a time window of s to 100 h at different temperatures shifted horizontally to form a single master curve at 25 o. C. Points: shift factors used Line: WLF equation

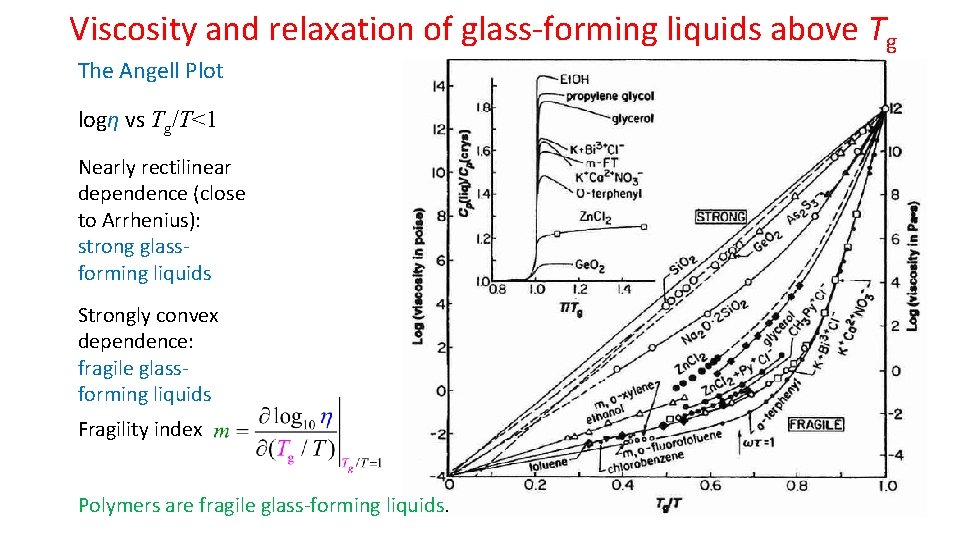

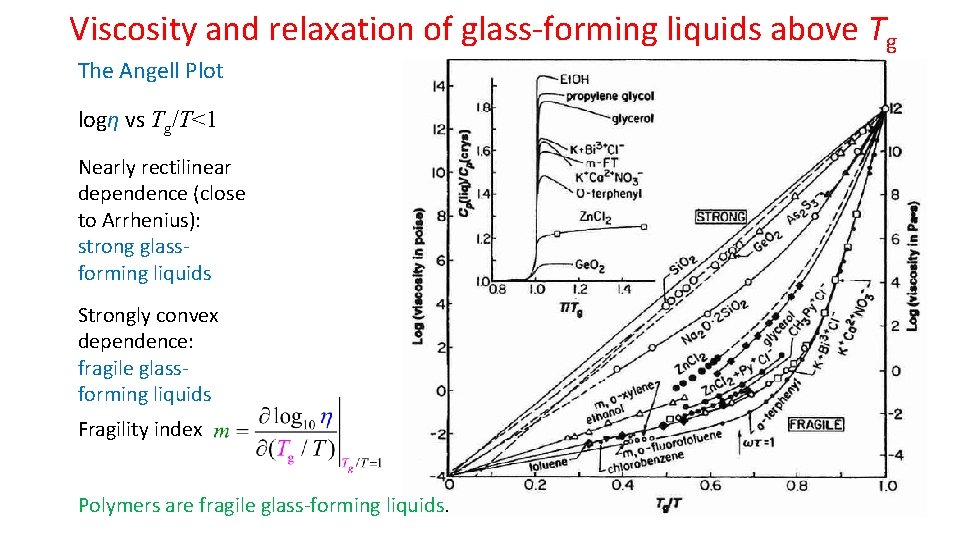

Viscosity and relaxation of glass-forming liquids above Tg The Angell Plot logη vs Tg/T<1 Nearly rectilinear dependence (close to Arrhenius): strong glassforming liquids Strongly convex dependence: fragile glassforming liquids Fragility index Polymers are fragile glass-forming liquids.

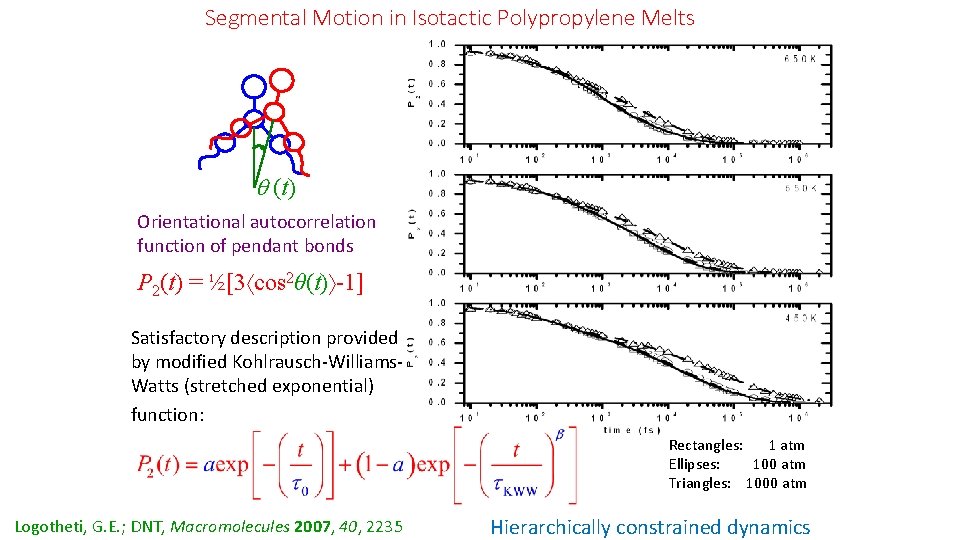

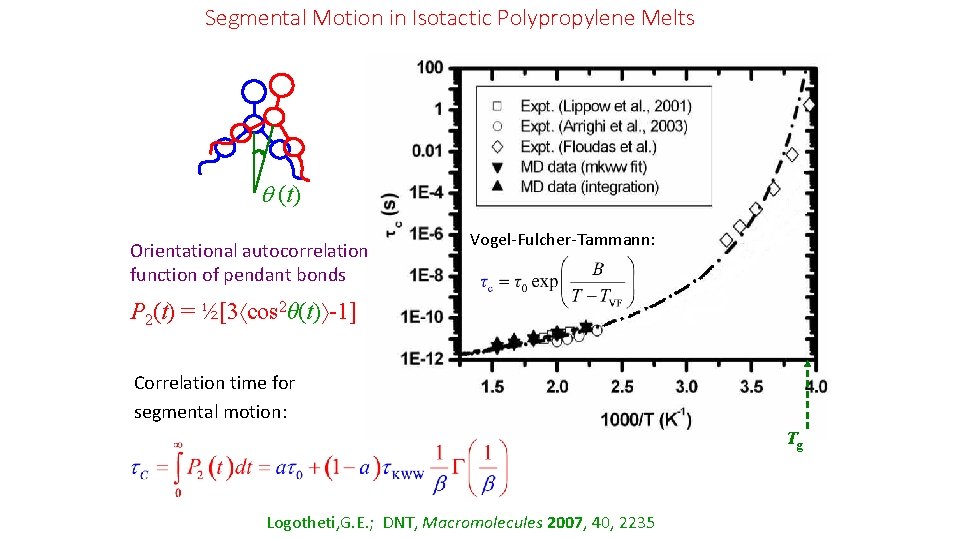

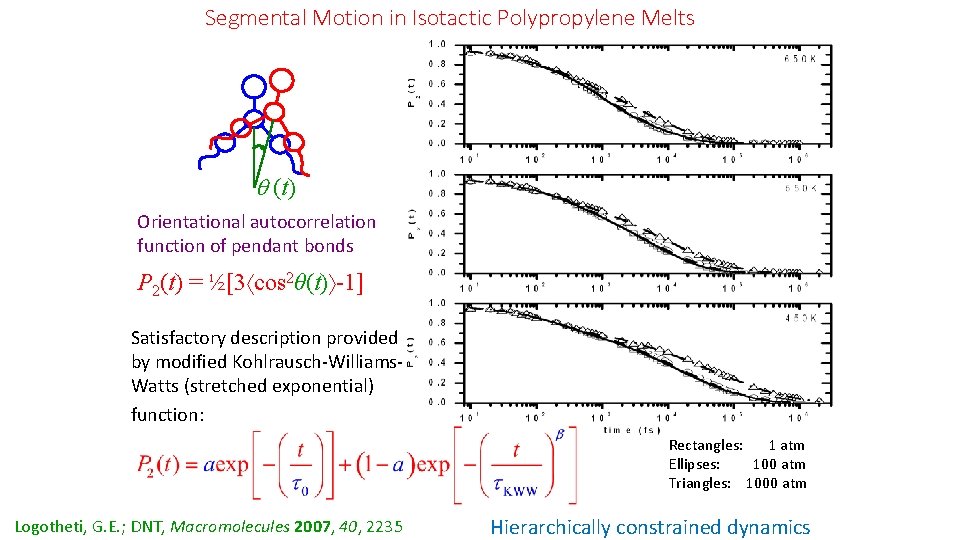

Segmental Motion in Isotactic Polypropylene Melts (t) Orientational autocorrelation function of pendant bonds P 2(t) = ½[3 cos 2θ(t) -1] Satisfactory description provided by modified Kohlrausch-Williams. Watts (stretched exponential) function: Rectangles: 1 atm Εllipses: 100 atm Τriangles: 1000 atm Logotheti, G. E. ; DNT, Macromolecules 2007, 40, 2235 Hierarchically constrained dynamics

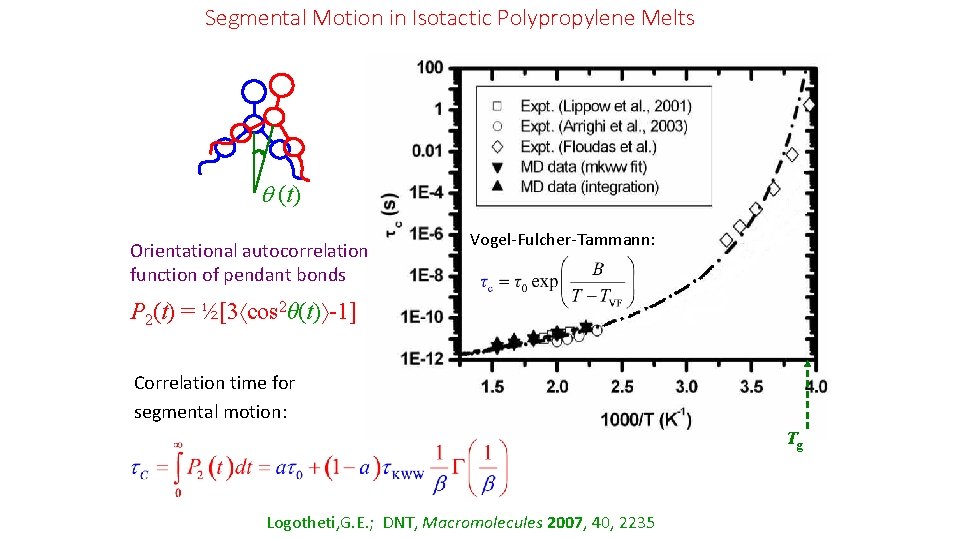

Segmental Motion in Isotactic Polypropylene Melts (t) Orientational autocorrelation function of pendant bonds Vogel-Fulcher-Tammann: P 2(t) = ½[3 cos 2θ(t) -1] Correlation time for segmental motion: Tg Logotheti, G. E. ; DNT, Macromolecules 2007, 40, 2235

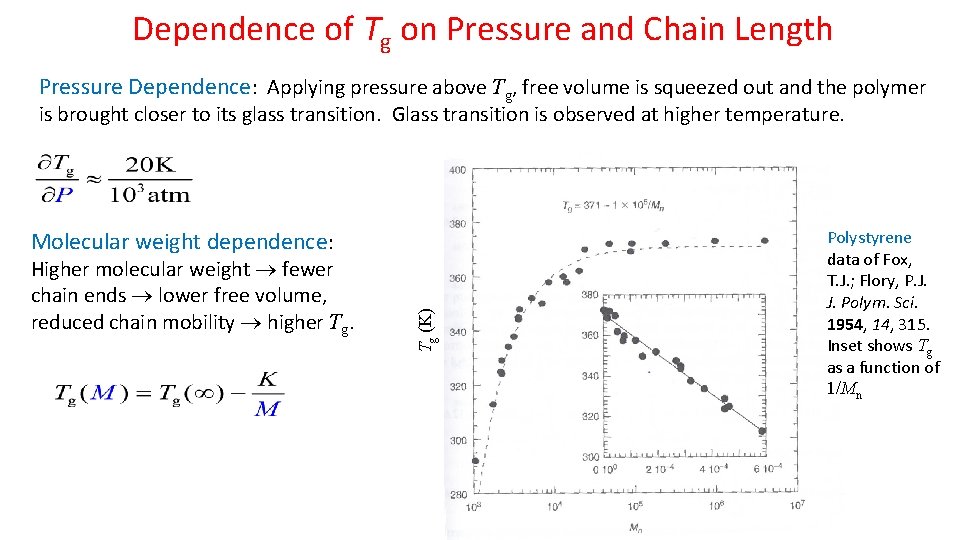

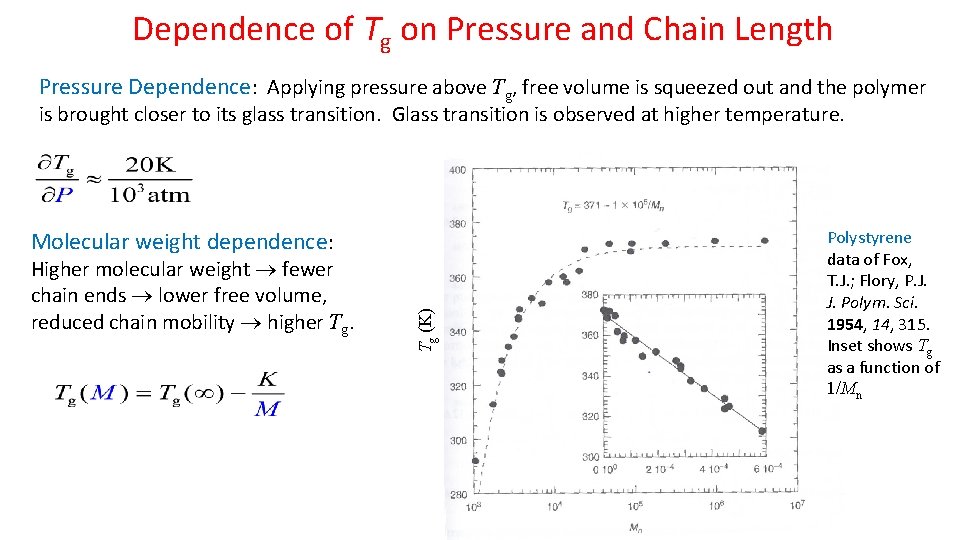

Dependence of Tg on Pressure and Chain Length Pressure Dependence: Applying pressure above Tg, free volume is squeezed out and the polymer is brought closer to its glass transition. Glass transition is observed at higher temperature. Higher molecular weight fewer chain ends lower free volume, reduced chain mobility higher Tg. Tg (K) Molecular weight dependence: Polystyrene data of Fox, T. J. ; Flory, P. J. J. Polym. Sci. 1954, 14, 315. Inset shows Tg as a function of 1/Mn

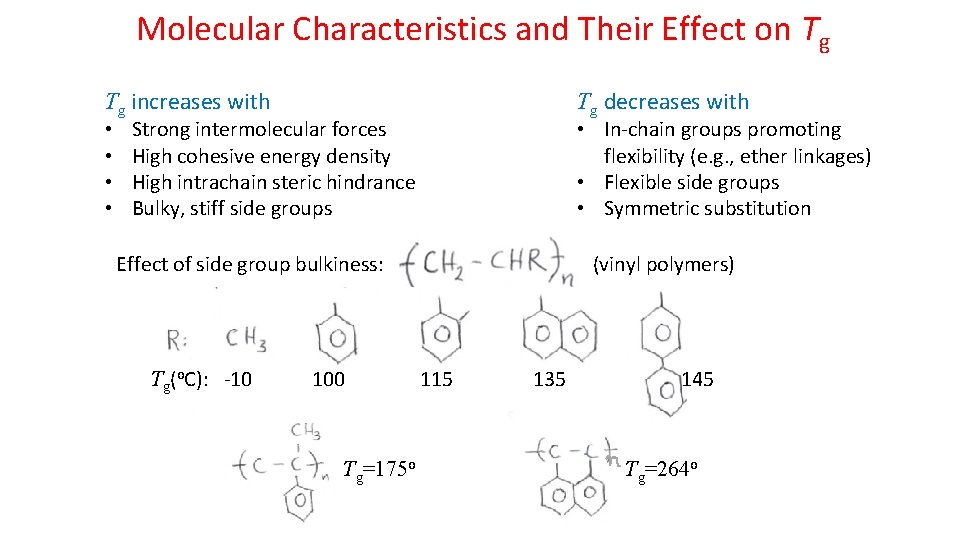

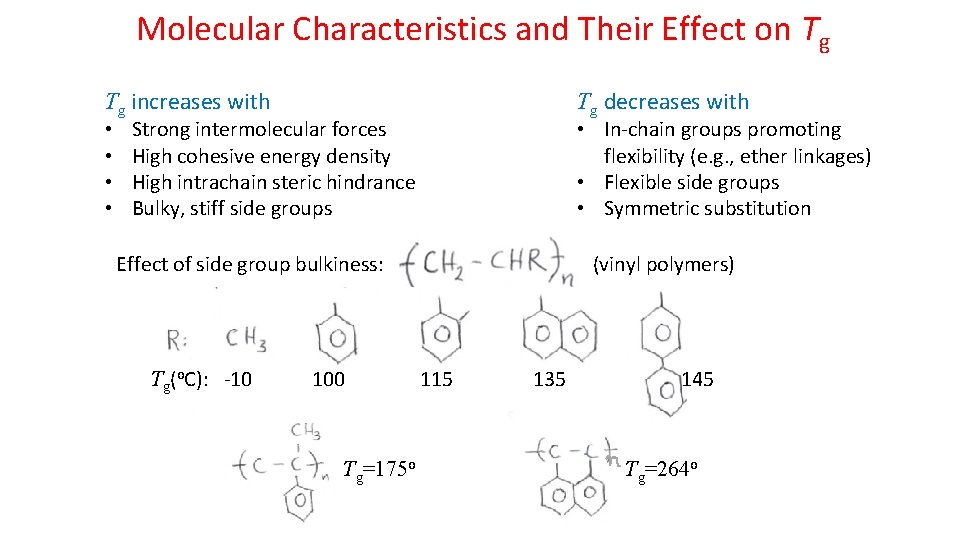

Molecular Characteristics and Their Effect on Tg Tg increases with • • Tg decreases with Strong intermolecular forces High cohesive energy density High intrachain steric hindrance Bulky, stiff side groups • In-chain groups promoting flexibility (e. g. , ether linkages) • Flexible side groups • Symmetric substitution Effect of side group bulkiness: Tg(o. C): -10 100 Tg=175 o (vinyl polymers) 115 135 145 Tg=264 o

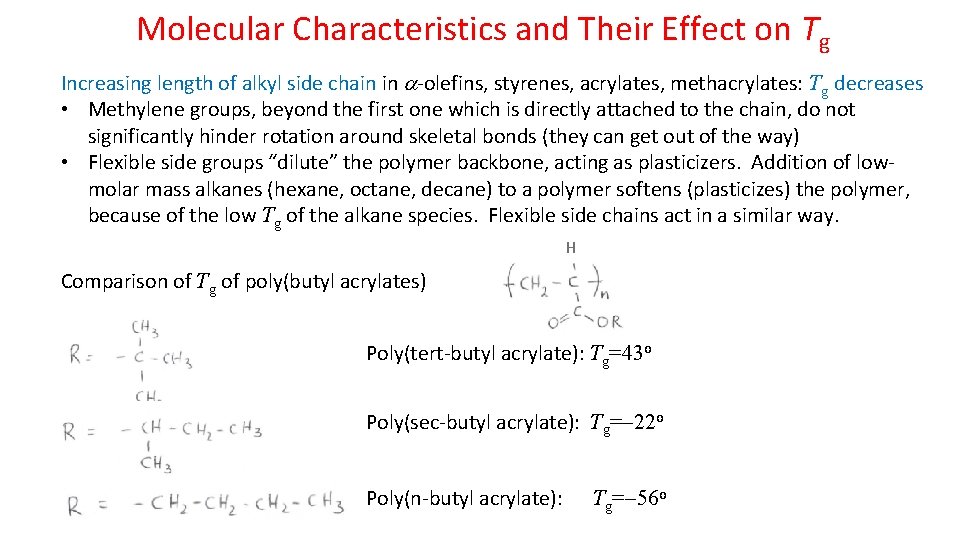

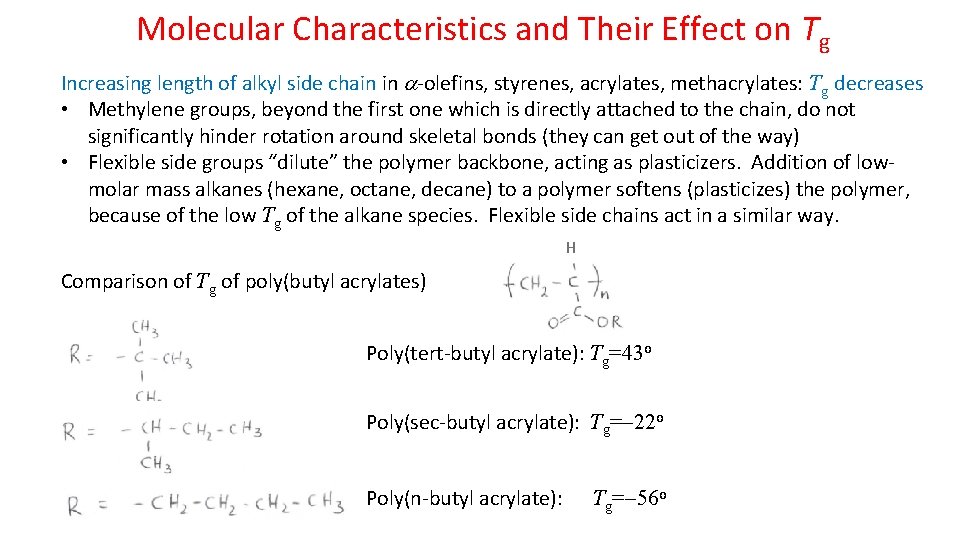

Molecular Characteristics and Their Effect on Tg Increasing length of alkyl side chain in -olefins, styrenes, acrylates, methacrylates: Tg decreases • Methylene groups, beyond the first one which is directly attached to the chain, do not significantly hinder rotation around skeletal bonds (they can get out of the way) • Flexible side groups “dilute” the polymer backbone, acting as plasticizers. Addition of lowmolar mass alkanes (hexane, octane, decane) to a polymer softens (plasticizes) the polymer, because of the low Tg of the alkane species. Flexible side chains act in a similar way. H Comparison of Tg of poly(butyl acrylates) Poly(tert-butyl acrylate): Tg=43 o Poly(sec-butyl acrylate): Tg= 22 o Poly(n-butyl acrylate): Tg= 56 o

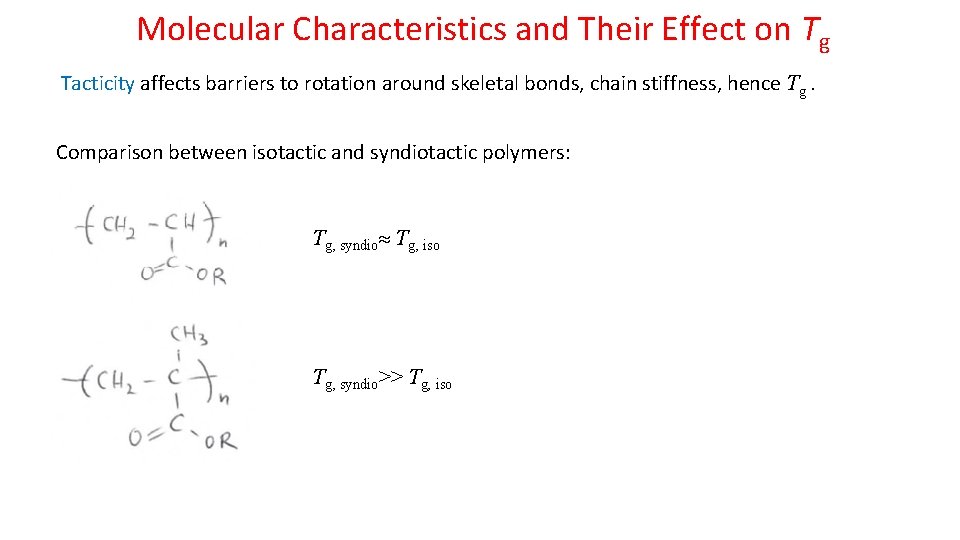

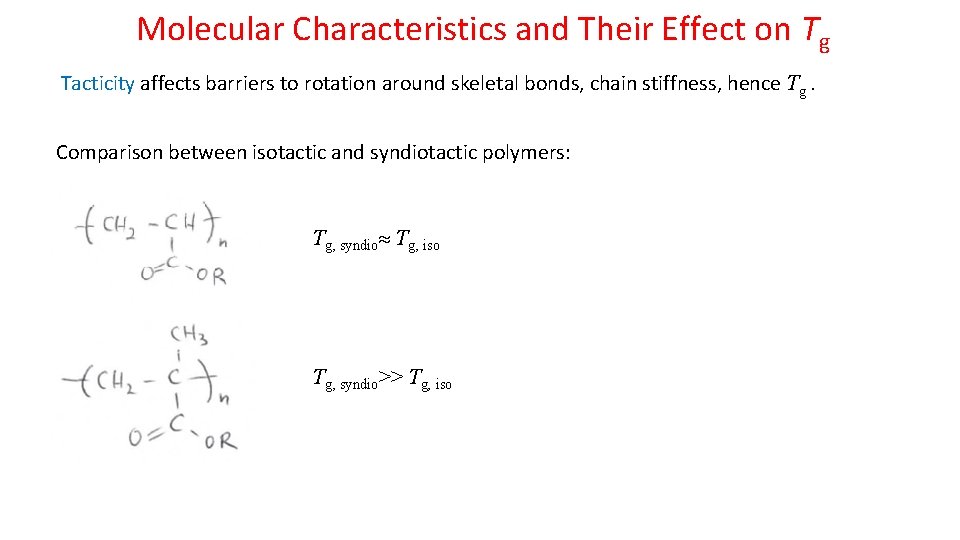

Molecular Characteristics and Their Effect on Tg Tacticity affects barriers to rotation around skeletal bonds, chain stiffness, hence Tg. Comparison between isotactic and syndiotactic polymers: Tg, syndio Tg, iso Tg, syndio>> Tg, iso

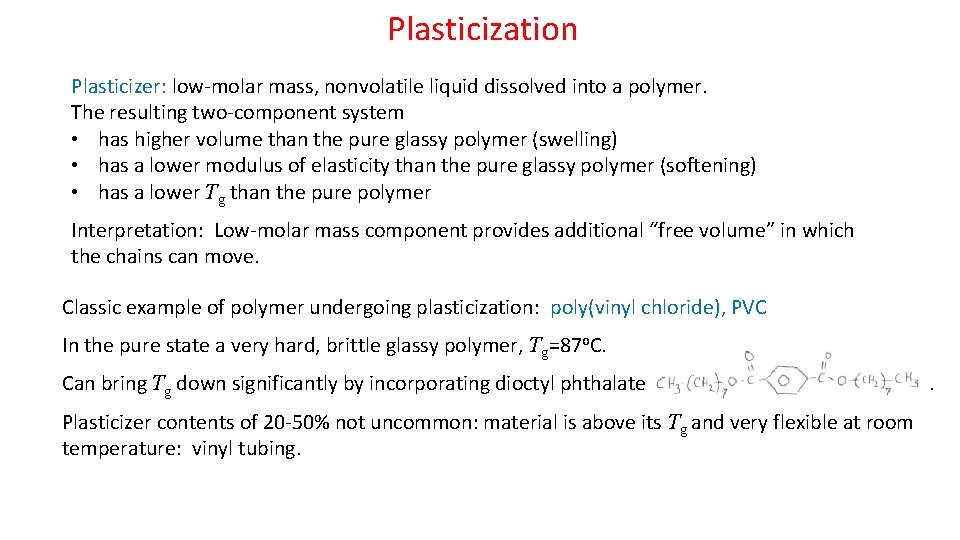

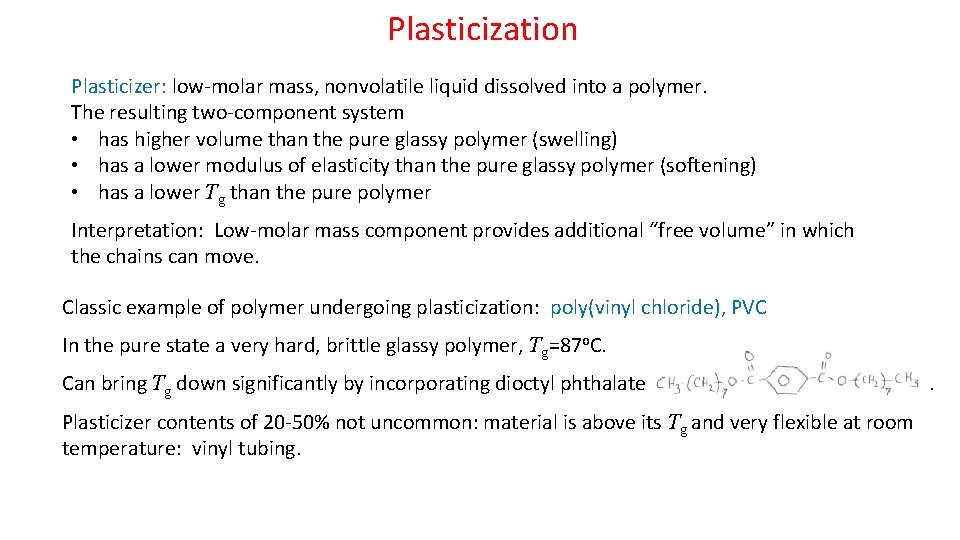

Plasticization Plasticizer: low-molar mass, nonvolatile liquid dissolved into a polymer. The resulting two-component system • has higher volume than the pure glassy polymer (swelling) • has a lower modulus of elasticity than the pure glassy polymer (softening) • has a lower Tg than the pure polymer Interpretation: Low-molar mass component provides additional “free volume” in which the chains can move. Classic example of polymer undergoing plasticization: poly(vinyl chloride), PVC In the pure state a very hard, brittle glassy polymer, Tg=87 o. C. Can bring Tg down significantly by incorporating dioctyl phthalate Plasticizer contents of 20 -50% not uncommon: material is above its Tg and very flexible at room temperature: vinyl tubing. .

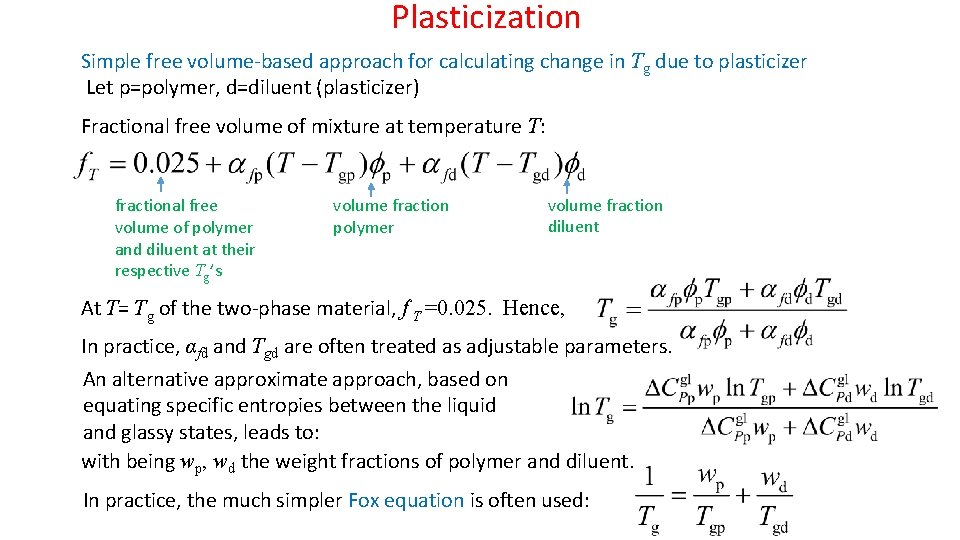

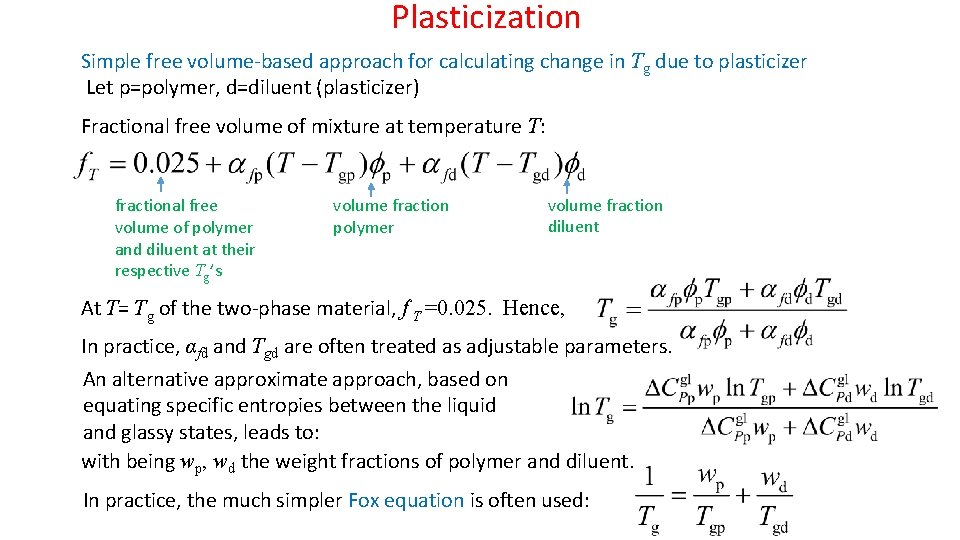

Plasticization Simple free volume-based approach for calculating change in Tg due to plasticizer Let p=polymer, d=diluent (plasticizer) Fractional free volume of mixture at temperature T: fractional free volume of polymer and diluent at their respective Tg’s volume fraction polymer volume fraction diluent At T= Tg of the two-phase material, f T =0. 025. Hence, In practice, αfd and Tgd are often treated as adjustable parameters. An alternative approximate approach, based on equating specific entropies between the liquid and glassy states, leads to: with being wp, wd the weight fractions of polymer and diluent. In practice, the much simpler Fox equation is often used:

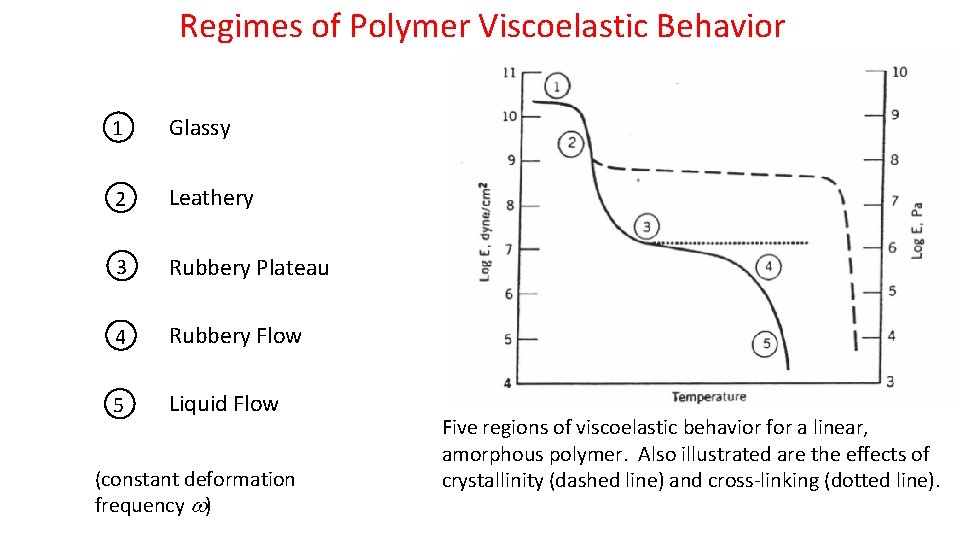

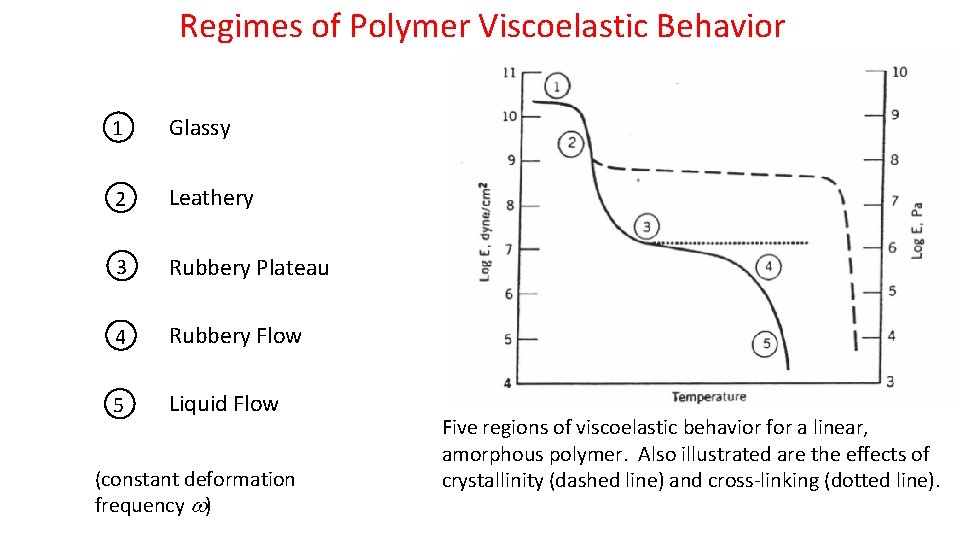

Regimes of Polymer Viscoelastic Behavior 1 Glassy 2 Leathery 3 Rubbery Plateau 4 Rubbery Flow 5 Liquid Flow (constant deformation frequency ) Five regions of viscoelastic behavior for a linear, amorphous polymer. Also illustrated are the effects of crystallinity (dashed line) and cross-linking (dotted line).

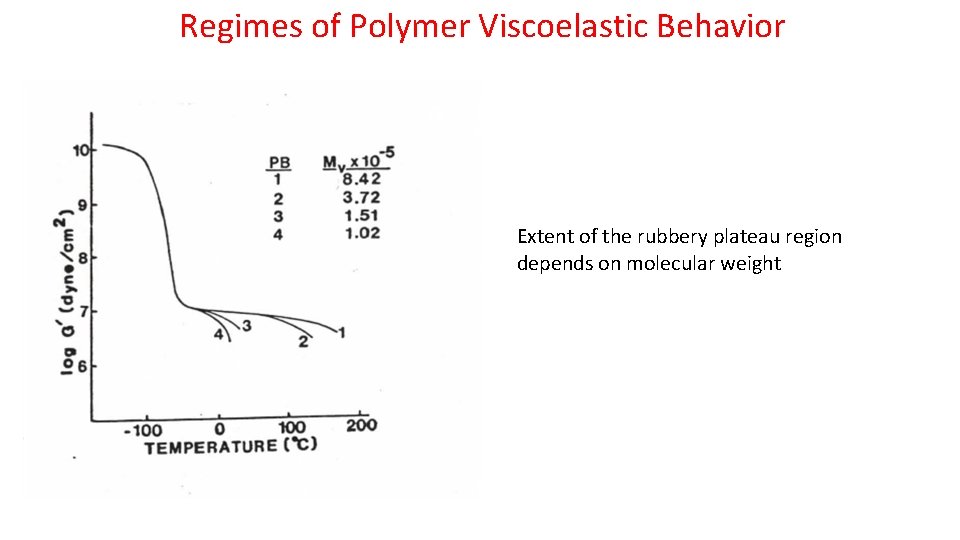

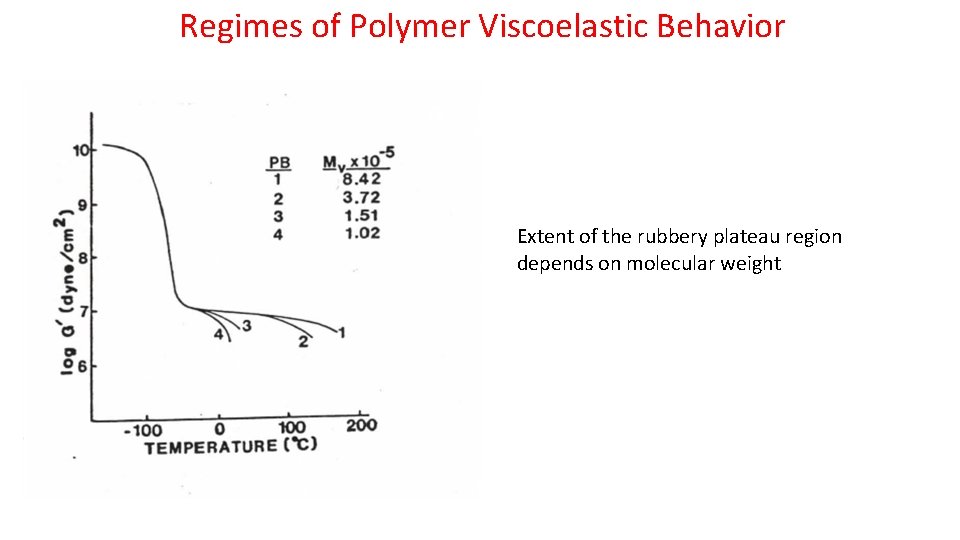

Regimes of Polymer Viscoelastic Behavior Extent of the rubbery plateau region depends on molecular weight