The German case method in criminal law Thomas

- Slides: 19

The German case method in criminal law Thomas Kruessmann Belarus State University 21 -23 May 2018

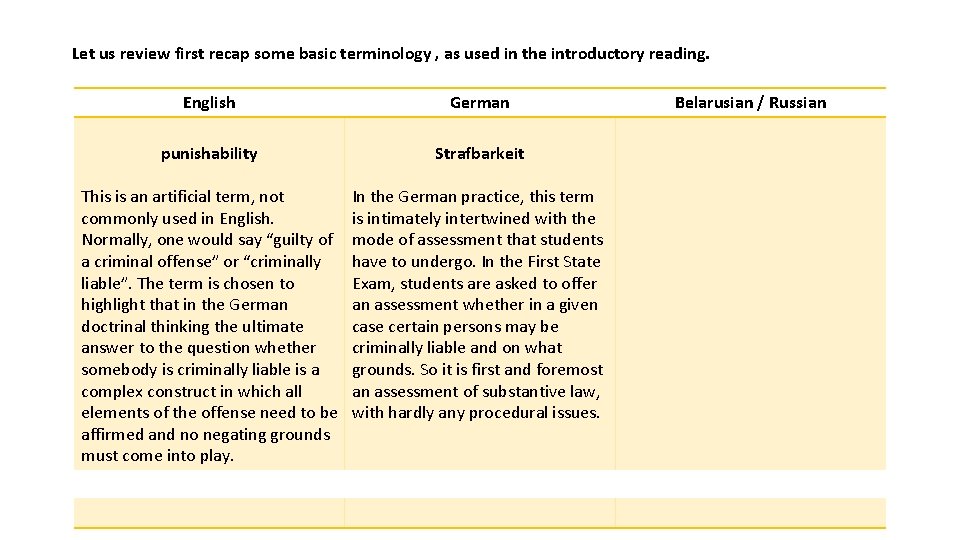

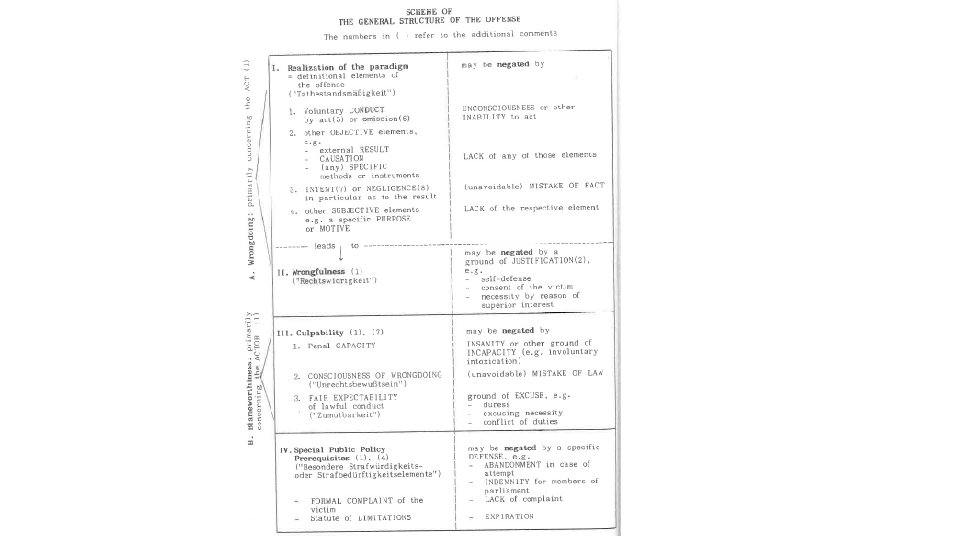

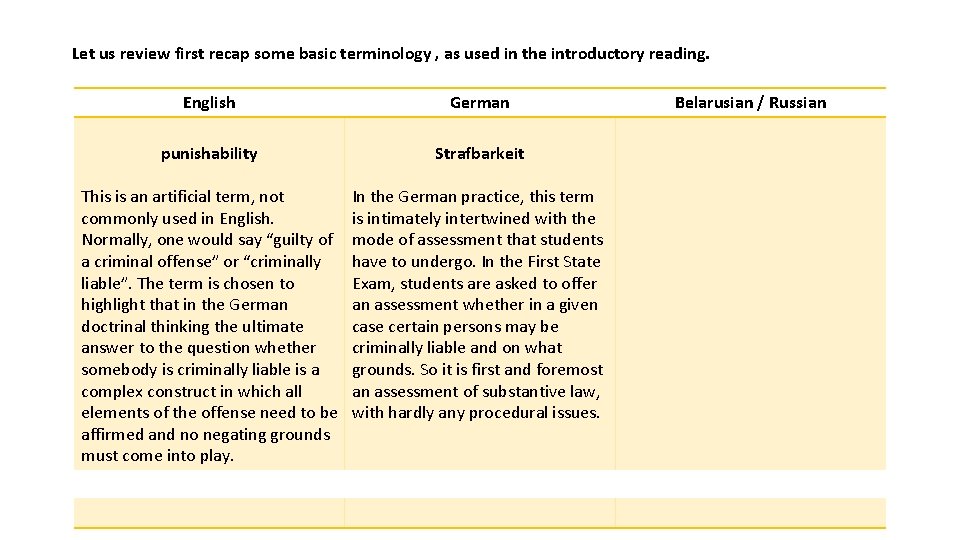

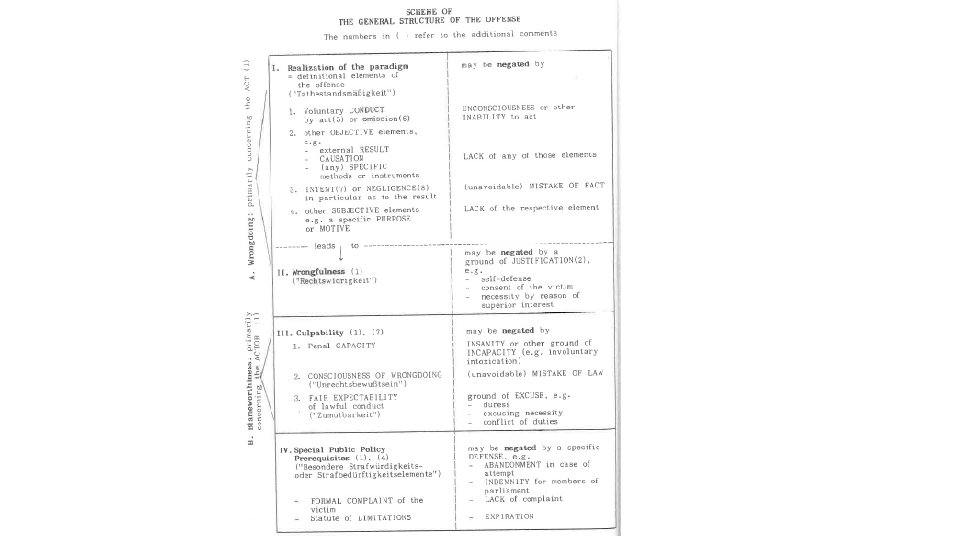

Let us review first recap some basic terminology , as used in the introductory reading. English German punishability Strafbarkeit This is an artificial term, not commonly used in English. Normally, one would say “guilty of a criminal offense” or “criminally liable”. The term is chosen to highlight that in the German doctrinal thinking the ultimate answer to the question whether somebody is criminally liable is a complex construct in which all elements of the offense need to be affirmed and no negating grounds must come into play. In the German practice, this term is intimately intertwined with the mode of assessment that students have to undergo. In the First State Exam, students are asked to offer an assessment whether in a given case certain persons may be criminally liable and on what grounds. So it is first and foremost an assessment of substantive law, with hardly any procedural issues. Belarusian / Russian

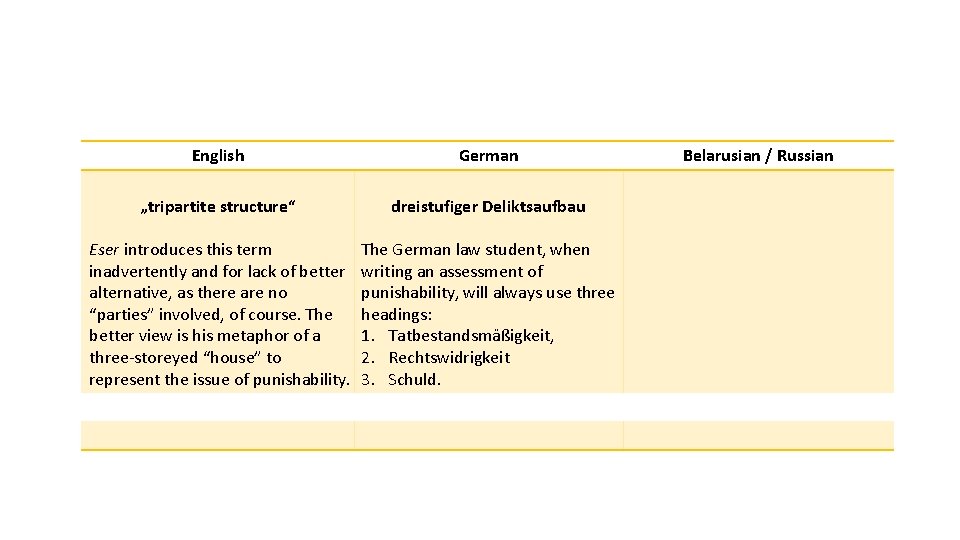

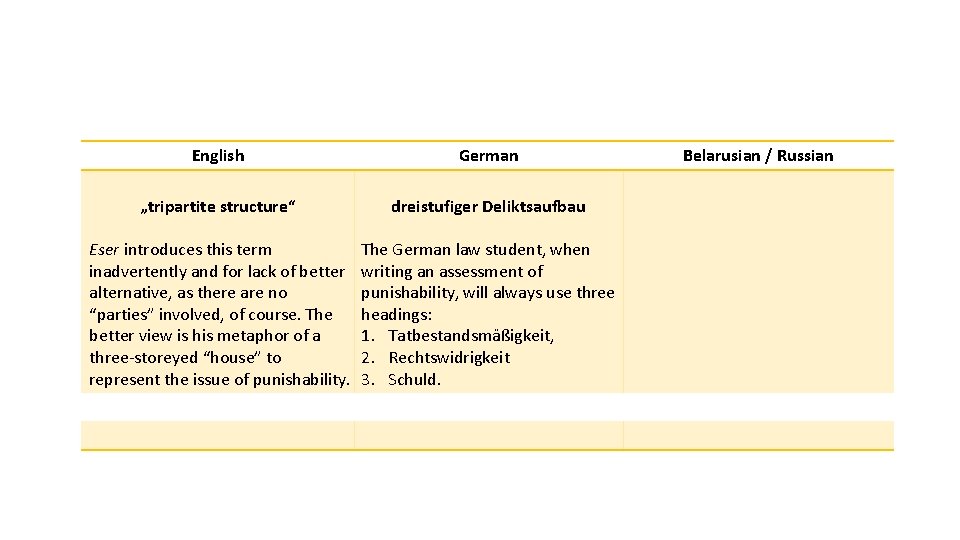

English German „tripartite structure“ dreistufiger Deliktsaufbau Eser introduces this term inadvertently and for lack of better alternative, as there are no “parties” involved, of course. The better view is his metaphor of a three-storeyed “house” to represent the issue of punishability. The German law student, when writing an assessment of punishability, will always use three headings: 1. Tatbestandsmäßigkeit, 2. Rechtswidrigkeit 3. Schuld. Belarusian / Russian

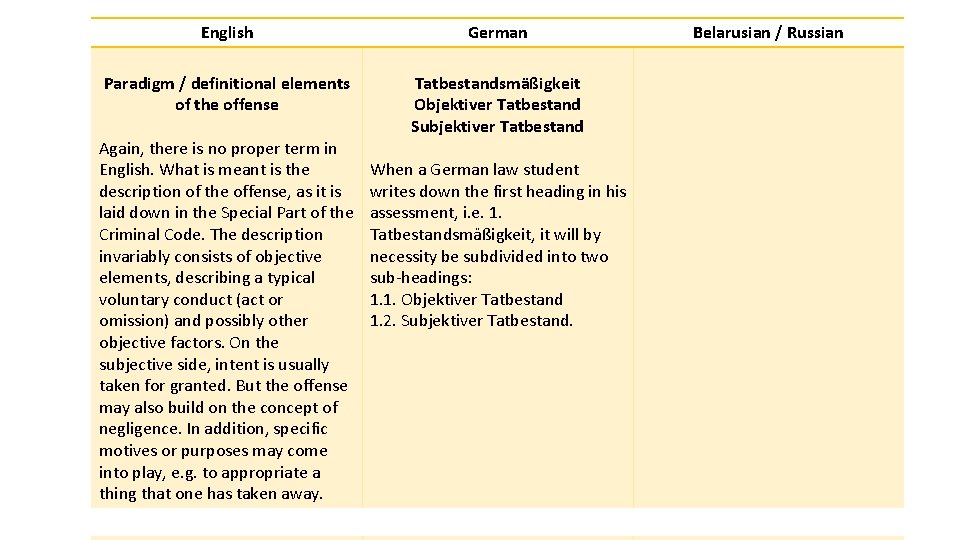

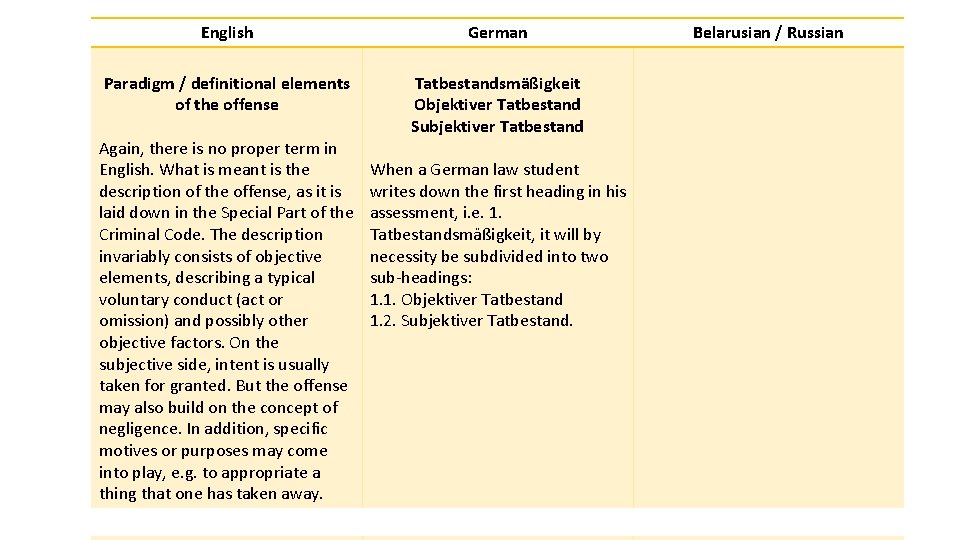

English German Paradigm / definitional elements of the offense Tatbestandsmäßigkeit Objektiver Tatbestand Subjektiver Tatbestand Again, there is no proper term in English. What is meant is the description of the offense, as it is laid down in the Special Part of the Criminal Code. The description invariably consists of objective elements, describing a typical voluntary conduct (act or omission) and possibly other objective factors. On the subjective side, intent is usually taken for granted. But the offense may also build on the concept of negligence. In addition, specific motives or purposes may come into play, e. g. to appropriate a thing that one has taken away. When a German law student writes down the first heading in his assessment, i. e. 1. Tatbestandsmäßigkeit, it will by necessity be subdivided into two sub-headings: 1. 1. Objektiver Tatbestand 1. 2. Subjektiver Tatbestand. Belarusian / Russian

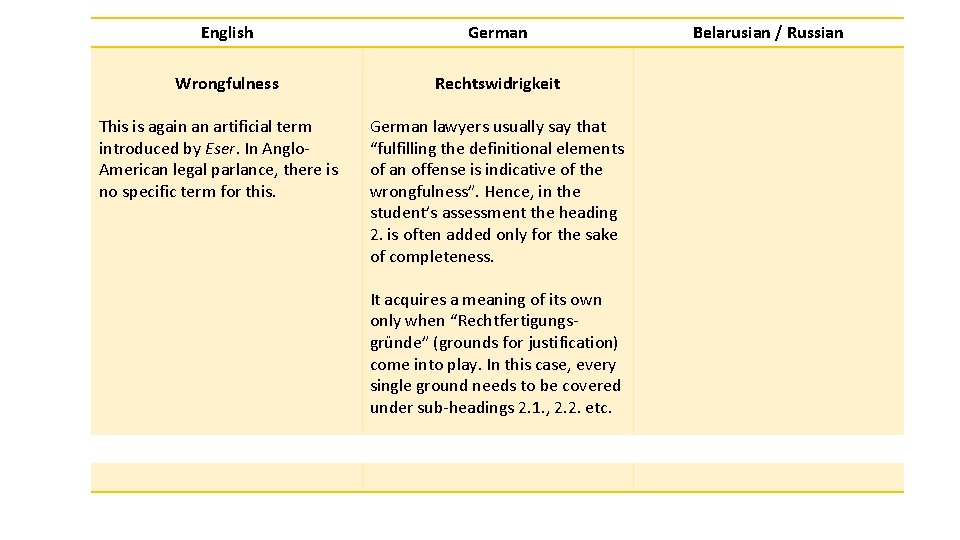

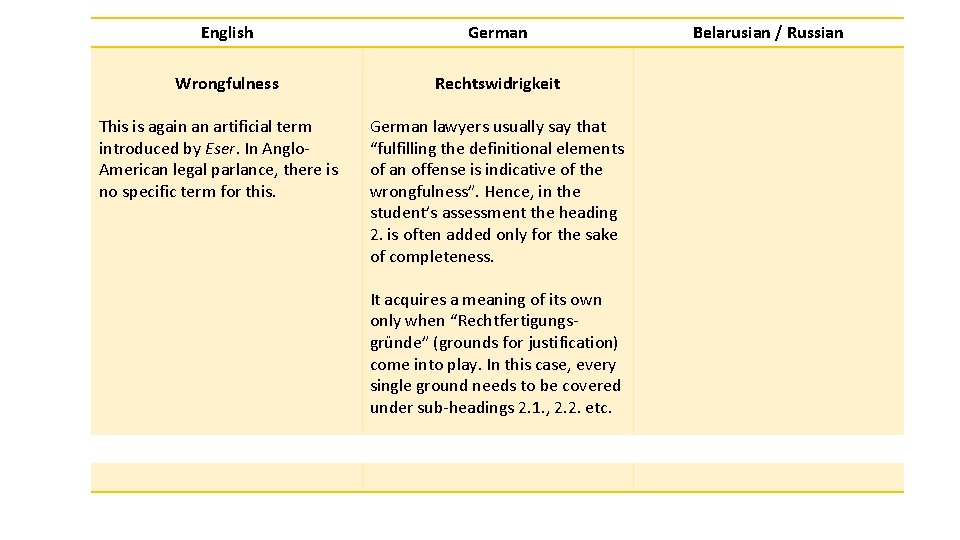

English German Wrongfulness Rechtswidrigkeit This is again an artificial term introduced by Eser. In Anglo. American legal parlance, there is no specific term for this. German lawyers usually say that “fulfilling the definitional elements of an offense is indicative of the wrongfulness”. Hence, in the student’s assessment the heading 2. is often added only for the sake of completeness. It acquires a meaning of its own only when “Rechtfertigungsgründe” (grounds for justification) come into play. In this case, every single ground needs to be covered under sub-headings 2. 1. , 2. 2. etc. Belarusian / Russian

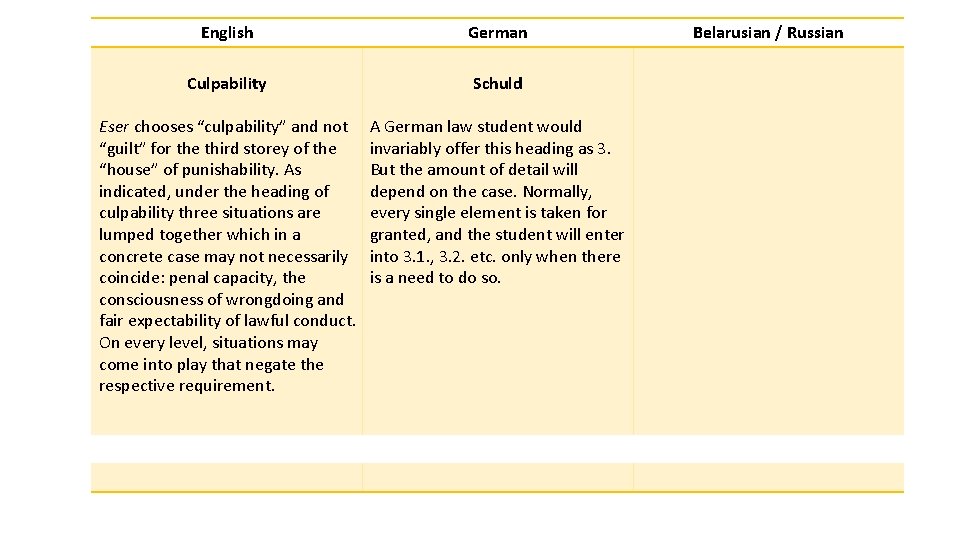

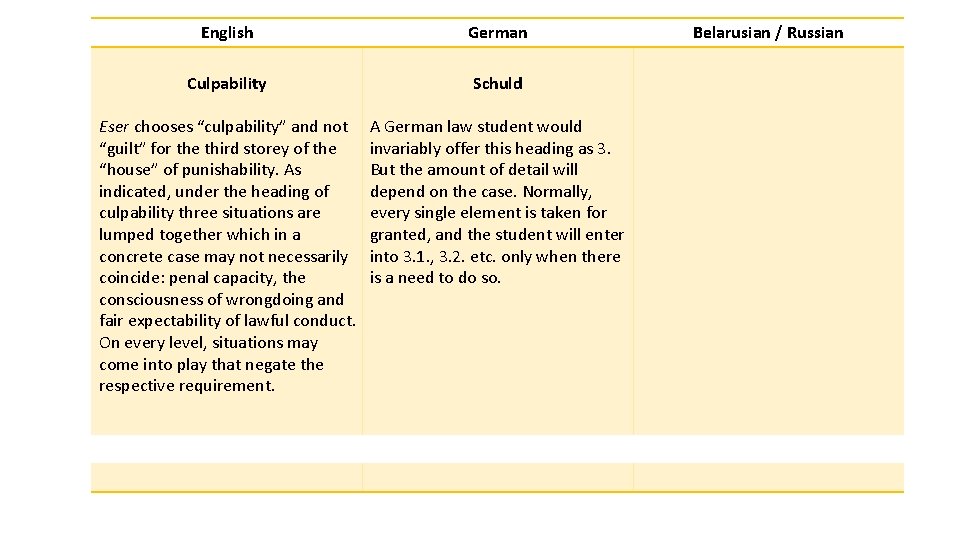

English German Culpability Schuld Eser chooses “culpability” and not “guilt” for the third storey of the “house” of punishability. As indicated, under the heading of culpability three situations are lumped together which in a concrete case may not necessarily coincide: penal capacity, the consciousness of wrongdoing and fair expectability of lawful conduct. On every level, situations may come into play that negate the respective requirement. A German law student would invariably offer this heading as 3. But the amount of detail will depend on the case. Normally, every single element is taken for granted, and the student will enter into 3. 1. , 3. 2. etc. only when there is a need to do so. Belarusian / Russian

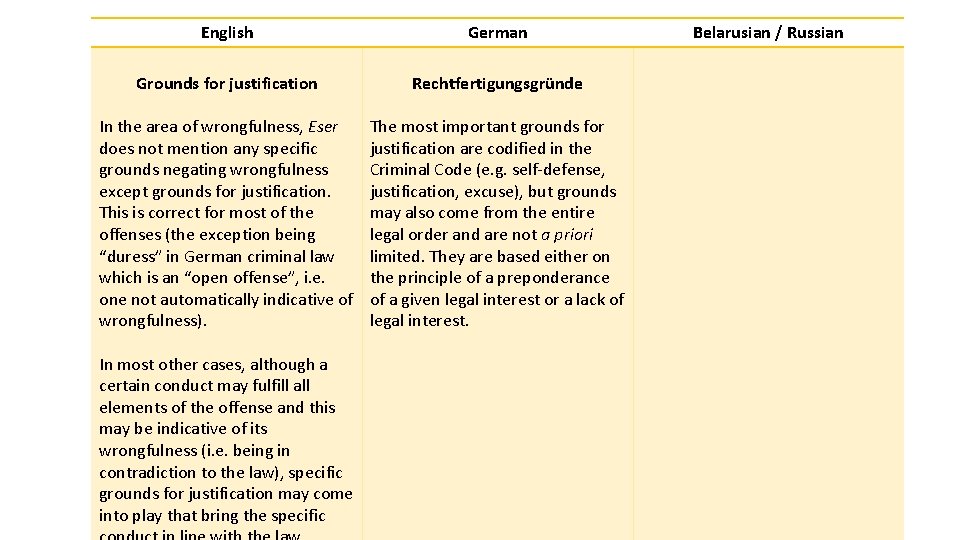

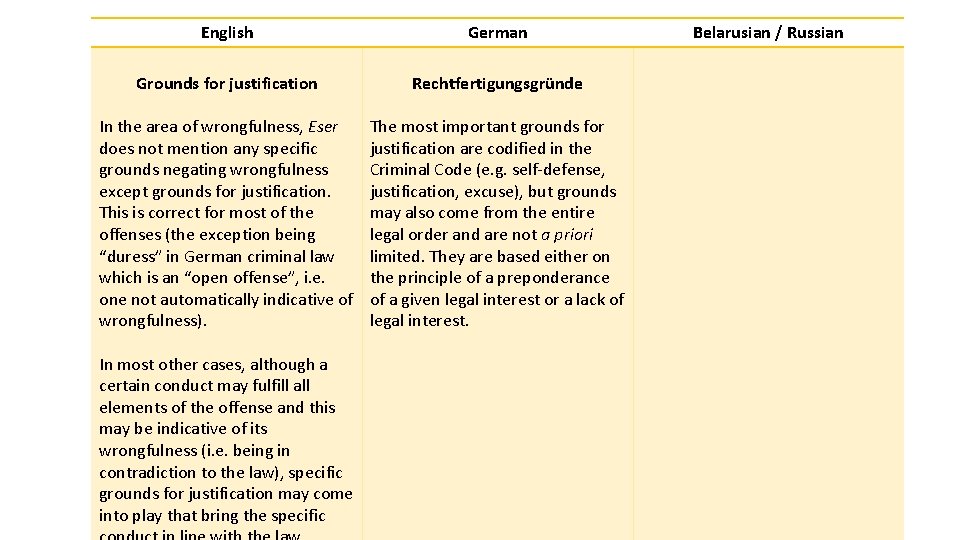

English German Grounds for justification Rechtfertigungsgründe In the area of wrongfulness, Eser does not mention any specific grounds negating wrongfulness except grounds for justification. This is correct for most of the offenses (the exception being “duress” in German criminal law which is an “open offense”, i. e. one not automatically indicative of wrongfulness). The most important grounds for justification are codified in the Criminal Code (e. g. self-defense, justification, excuse), but grounds may also come from the entire legal order and are not a priori limited. They are based either on the principle of a preponderance of a given legal interest or a lack of legal interest. In most other cases, although a certain conduct may fulfill all elements of the offense and this may be indicative of its wrongfulness (i. e. being in contradiction to the law), specific grounds for justification may come into play that bring the specific Belarusian / Russian

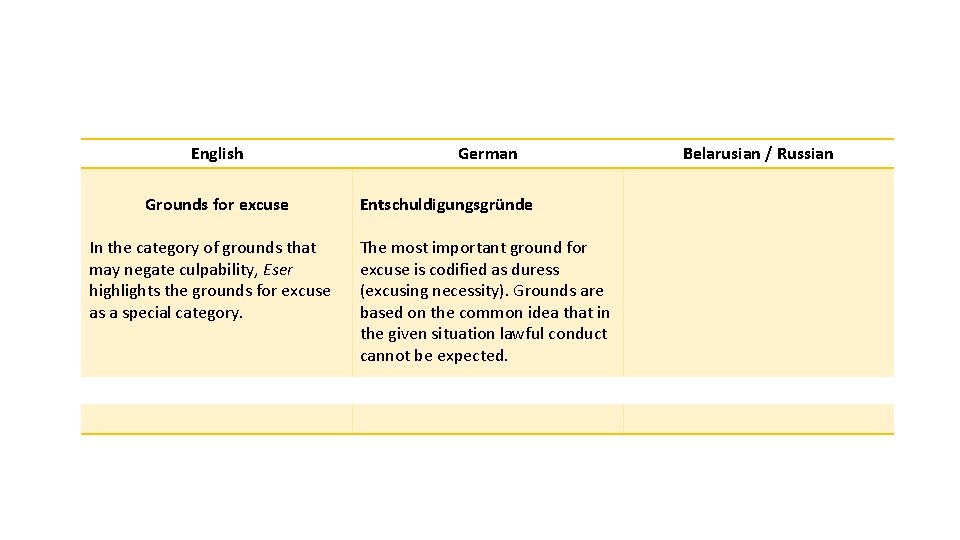

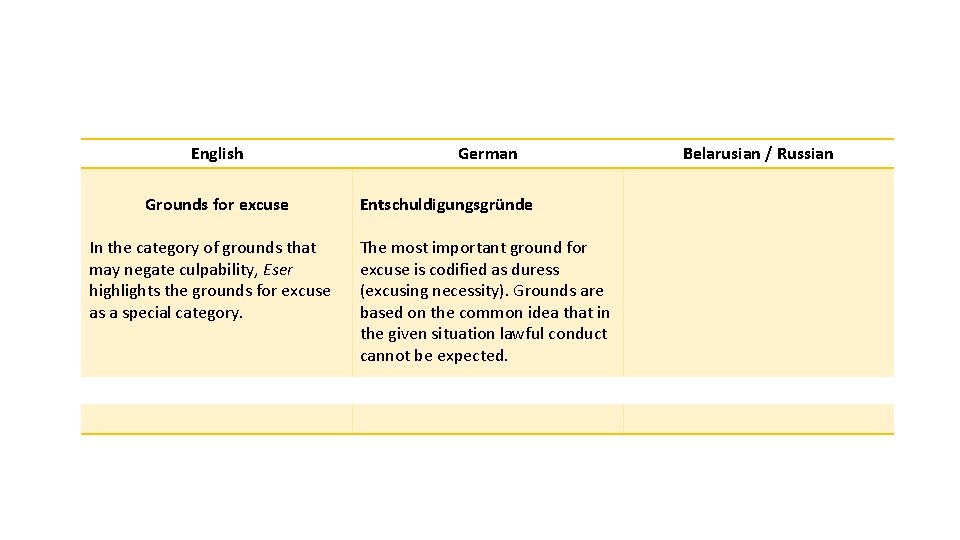

English Grounds for excuse In the category of grounds that may negate culpability, Eser highlights the grounds for excuse as a special category. German Entschuldigungsgründe The most important ground for excuse is codified as duress (excusing necessity). Grounds are based on the common idea that in the given situation lawful conduct cannot be expected. Belarusian / Russian

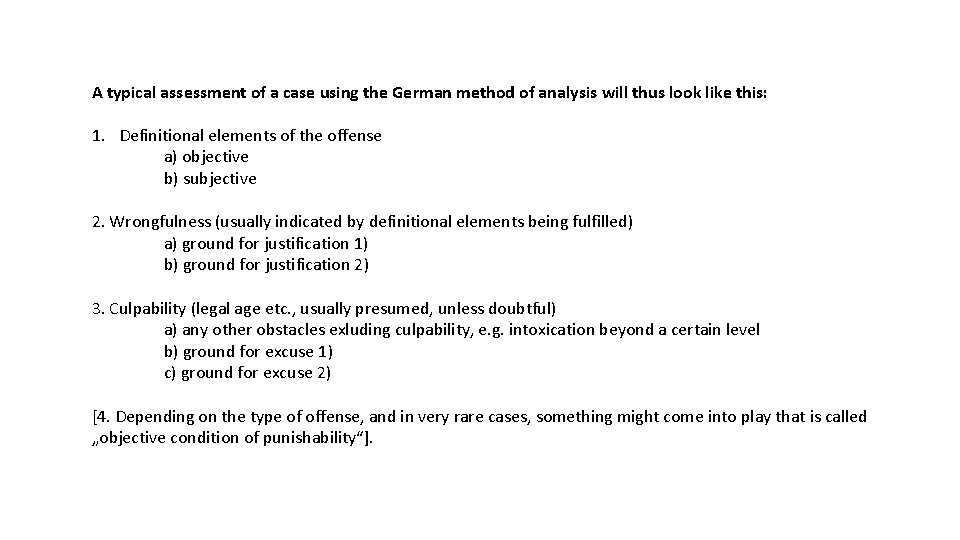

A typical assessment of a case using the German method of analysis will thus look like this: 1. Definitional elements of the offense a) objective b) subjective 2. Wrongfulness (usually indicated by definitional elements being fulfilled) a) ground for justification 1) b) ground for justification 2) 3. Culpability (legal age etc. , usually presumed, unless doubtful) a) any other obstacles exluding culpability, e. g. intoxication beyond a certain level b) ground for excuse 1) c) ground for excuse 2) [4. Depending on the type of offense, and in very rare cases, something might come into play that is called „objective condition of punishability“].

Let us use a very simple case as an example: A and his younger brother B decide to rob a bank. It is A’s idea and he is also the mastermind of the plan. B is just helping. Upon entering the bank as customers, A shoots an unsuspecting guard. He then threatens the cashier with his gun to hand out the money. B joins A into the bank but plays no active part. Earlier, he had helped his brother to obtain the gun. They make their escape on foot, but then A decides to take hold of a car that some neighbor left open on the street, and they continue their escape by car. The basic principles for building an assessment are the following: • The chain of historical events is categorized in complexes. • Punishability is assessed in principle for every potential offender separately. • Those who may have committed the offense directly will be assessed before those who may be punishable for aiding and abetting. • From among potential offenses, the “heavy-weight” ones will be assessed before the “light-weight” ones.

A. First complex: Getting the money from the bank I. Punishability of A 1. according to § 211 (“murder”) 2. according to §§ 249, 250 (robbery in an aggravated case) II. Punishability of B 1. According to §§ 211, 27 (aiding and abetting in murder) 2. According to §§ 249, 27 (aiding and abetting in robbery) B. Second complex: Escaping the bank I. Punishability of A 1. according to § 242 (theft of the car) 2. According to 248 a (making use of a car) II. Punishability of B According to §§ 242, 27 (aiding and abetting in making use of a car) C. Overall result

Zooming in now into the assessment of a certain offense, the fundamental “tripartite structure” comes into play. E. g. for murder (§ 211 German Criminal Code): A. First complex: Getting the money from the bank I. Punishability of A 1. according to § 211 (murder) Keeping in mind the wording of § 211: (1) Whosoever commits murder under the conditions of this provision shall be liable to imprisonment for life. (2) A murderer under this provision is any person who kills a person for pleasure, for sexual gratification, out of greed or otherwise base motives, by stealth or cruelly or by means that pose a danger to the public or in order to facilitate or to cover up another offence.

1. 1. Definitional elements of the offense This “three-step approach” of subsumtion is constituent for the style of the assessment! 1. 1. 1. – objective “to kill a person”? -> definition? applicable in the given situation? conclusion? ”out of greed”? -> definition? applicable in the given situation? conclusion “by stealth”? -> definition? applicable in the given situation? conclusion? e. g. what is the definition of “by stealth”? – taking advantage of the unsuspecting nature and the defenselessness of the victim – was the bank guard “unsuspecting”? – was he “defenseless” despite carrying a gun himself? 1. 1. 2. – subjective “with intent”? (unwritten element) other special subjective elements? e. g. ” to facilitate or to cover up another offence”? -> definition? applicable in the given situation? 1. 1. 3. Conclusion If for any reason some element on levels 1. 1. 1. and 1. 1. 2. is not fulfilled, the conclusion will be that there is no punishability. This will be the end of the assessment. If 1. 1. is fulfilled, we will continue into 1. 2.

1. 2. Wrongfulness We normally assume that when the definitional elements of an offense are fulfilled, the act (or omission) is wrongful. But certain justifications may come into play, e. g. 1. 2. 1. Self-defense (§ 32) 1. 2. 2. Justification (§ 34) 1. 2. 3. Other grounds for excluding wrongfulness Imagine some variations of the case in which a ground for justification comes in! E. g. A and the bank guard are enemies. When A enters the bank, the bank guard immediately suspects the robbery and decides to use the occasion as a pretext to kill A. A sees that the guard draws his gun and has no choice but to shoot him.

1. 3. Culpability We normally assume penal capacity etc. But there may be other factors, e. g. no consciousness of wrongdoing due to heavy intoxication or excuse / duress (§ 35). Imagine some variations of the case in which a ground for excuse comes in! 1. 4. Conclusion A is / is not punishable under § 211.

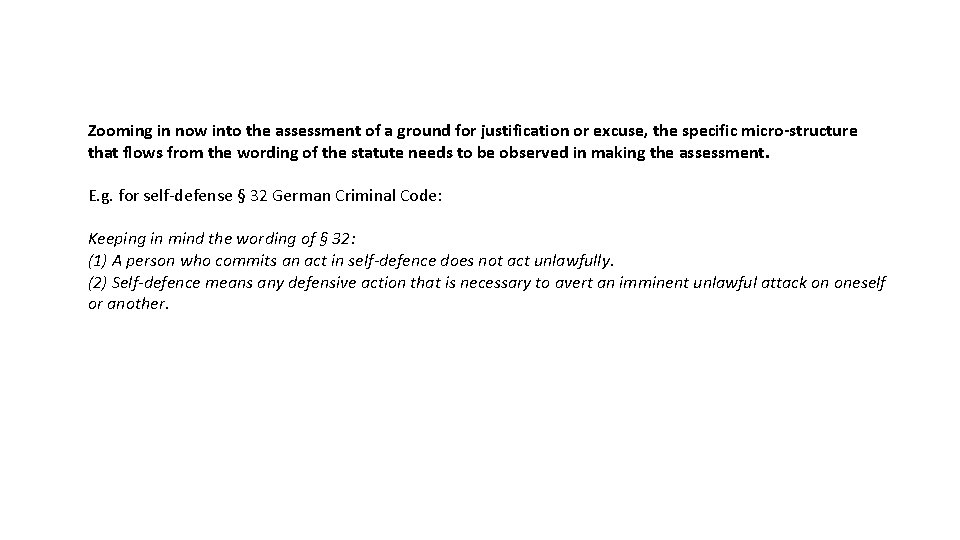

Zooming in now into the assessment of a ground for justification or excuse, the specific micro-structure that flows from the wording of the statute needs to be observed in making the assessment. E. g. for self-defense § 32 German Criminal Code: Keeping in mind the wording of § 32: (1) A person who commits an act in self-defence does not act unlawfully. (2) Self-defence means any defensive action that is necessary to avert an imminent unlawful attack on oneself or another.

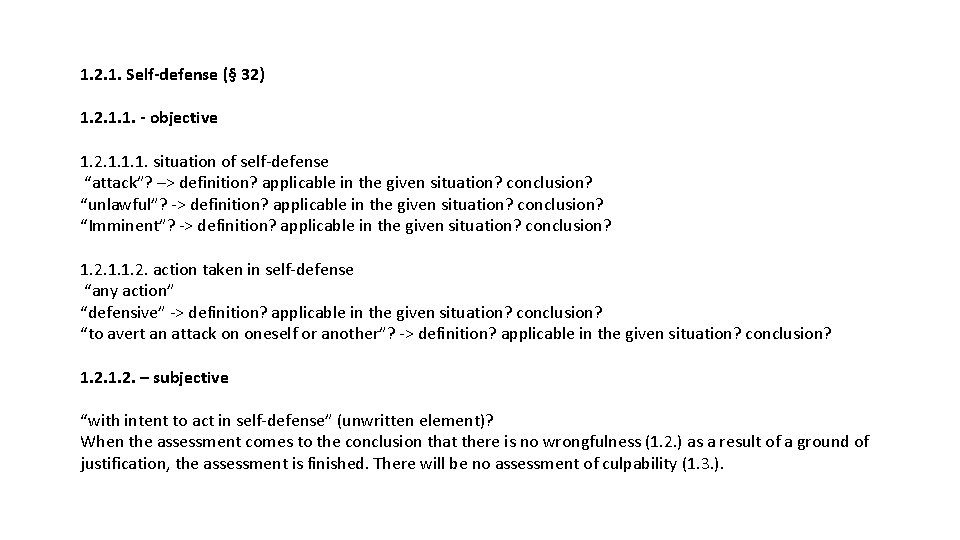

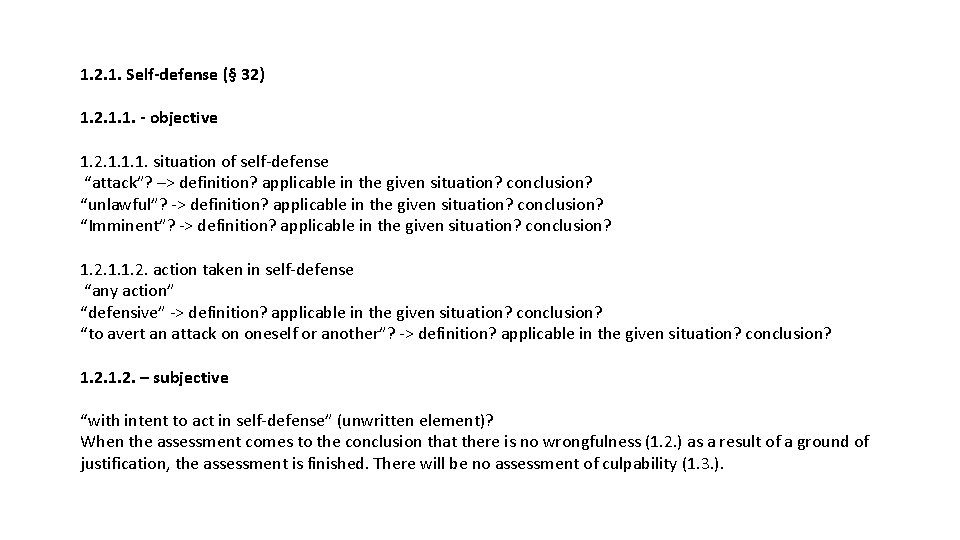

1. 2. 1. Self-defense (§ 32) 1. 2. 1. 1. - objective 1. 2. 1. 1. 1. situation of self-defense “attack”? –> definition? applicable in the given situation? conclusion? “unlawful”? -> definition? applicable in the given situation? conclusion? “Imminent”? -> definition? applicable in the given situation? conclusion? 1. 2. 1. 1. 2. action taken in self-defense “any action” “defensive” -> definition? applicable in the given situation? conclusion? “to avert an attack on oneself or another”? -> definition? applicable in the given situation? conclusion? 1. 2. – subjective “with intent to act in self-defense” (unwritten element)? When the assessment comes to the conclusion that there is no wrongfulness (1. 2. ) as a result of a ground of justification, the assessment is finished. There will be no assessment of culpability (1. 3. ).

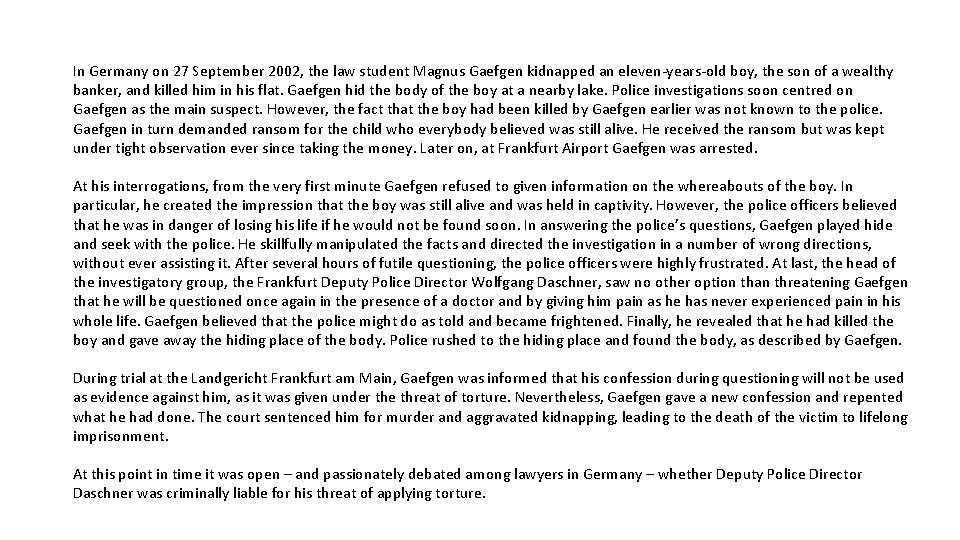

In Germany on 27 September 2002, the law student Magnus Gaefgen kidnapped an eleven-years-old boy, the son of a wealthy banker, and killed him in his flat. Gaefgen hid the body of the boy at a nearby lake. Police investigations soon centred on Gaefgen as the main suspect. However, the fact that the boy had been killed by Gaefgen earlier was not known to the police. Gaefgen in turn demanded ransom for the child who everybody believed was still alive. He received the ransom but was kept under tight observation ever since taking the money. Later on, at Frankfurt Airport Gaefgen was arrested. At his interrogations, from the very first minute Gaefgen refused to given information on the whereabouts of the boy. In particular, he created the impression that the boy was still alive and was held in captivity. However, the police officers believed that he was in danger of losing his life if he would not be found soon. In answering the police’s questions, Gaefgen played hide and seek with the police. He skillfully manipulated the facts and directed the investigation in a number of wrong directions, without ever assisting it. After several hours of futile questioning, the police officers were highly frustrated. At last, the head of the investigatory group, the Frankfurt Deputy Police Director Wolfgang Daschner, saw no other option than threatening Gaefgen that he will be questioned once again in the presence of a doctor and by giving him pain as he has never experienced pain in his whole life. Gaefgen believed that the police might do as told and became frightened. Finally, he revealed that he had killed the boy and gave away the hiding place of the body. Police rushed to the hiding place and found the body, as described by Gaefgen. During trial at the Landgericht Frankfurt am Main, Gaefgen was informed that his confession during questioning will not be used as evidence against him, as it was given under the threat of torture. Nevertheless, Gaefgen gave a new confession and repented what he had done. The court sentenced him for murder and aggravated kidnapping, leading to the death of the victim to lifelong imprisonment. At this point in time it was open – and passionately debated among lawyers in Germany – whether Deputy Police Director Daschner was criminally liable for his threat of applying torture.