The First Taste of Formal Verification a tutorial

- Slides: 27

The First Taste of Formal Verification (a tutorial to be given at ICCAD 2011) Alan Mishchenko UC Berkeley

Overview l l Introduction Verification engines l l Examples of verification engines l l Retiming, simulation, PDR Integrated verification flow Representations used in the tools l l Transformers, bug-hunters, provers BDDs, CNFs, AIGs Conclusion Side notes: Working for industry in academia 2

Introduction l l l Importance Scope of this talk Problem formulation l l l Safety vs. liveness property verification Bounded vs. unbounded verification Model checking (MC) vs. equivalence checking (EC) Outcomes of verification Sequential miter Certifying verification l Inductive invariant 3

Scope of This Talk l In this talk, we limit ourselves to l l Synchronous designs Verifying safety properties Designs represented as bit-level sequential logic circuits with the initial state(s) Extensions not covered l l l Analog designs Verifying liveness properties Word-level designs and properties Symbolic trajectory evaluation (STE) etc 4

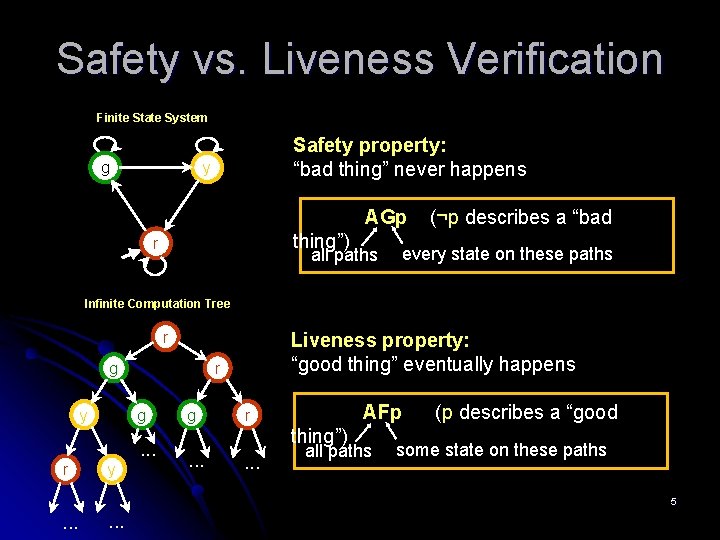

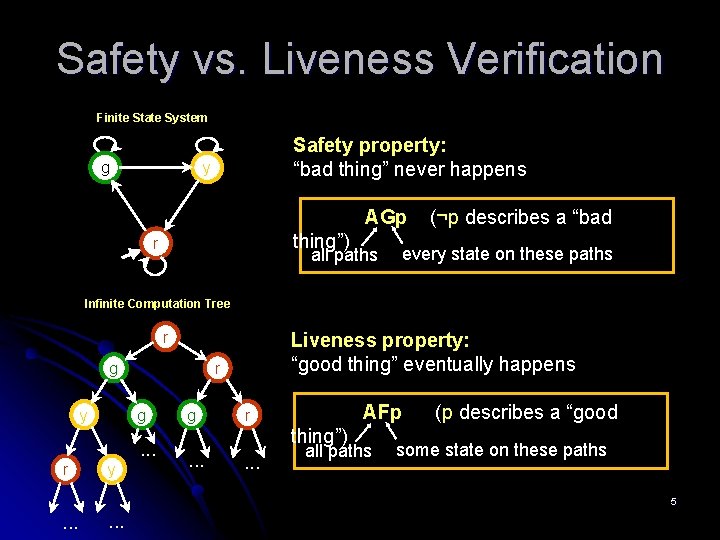

Safety vs. Liveness Verification Finite State System g Safety property: “bad thing” never happens y AGp thing”) r (¬p describes a “bad every state on these paths all paths Infinite Computation Tree r g y r g . . . r y Liveness property: “good thing” eventually happens g AFp r thing”). . . all paths (p describes a “good some state on these paths 5 . . .

Bounded vs. Unbounded Verification l Bounded-depth verification l Verifies property in the first few time frames l Important for quick checking of properties l Works well even for relatively large designs l Unbounded-depth verification l Verifies property for infinite time frames l Requires elaborate and scalable engines l Runs out of resources for complex properties in large designs 6

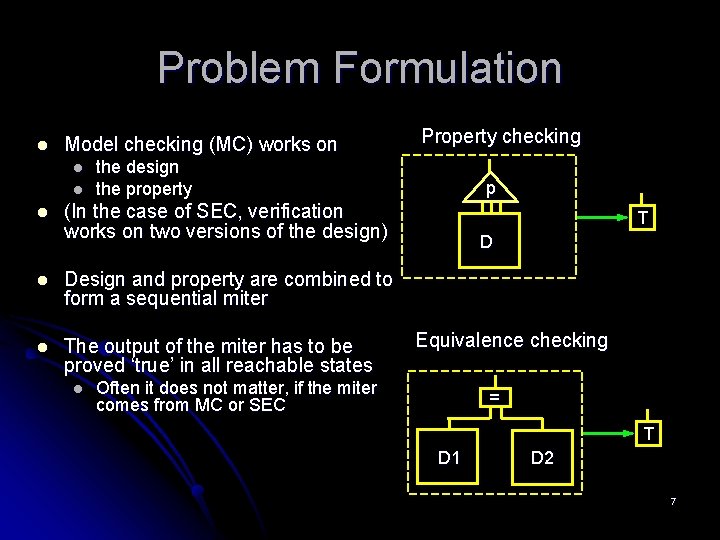

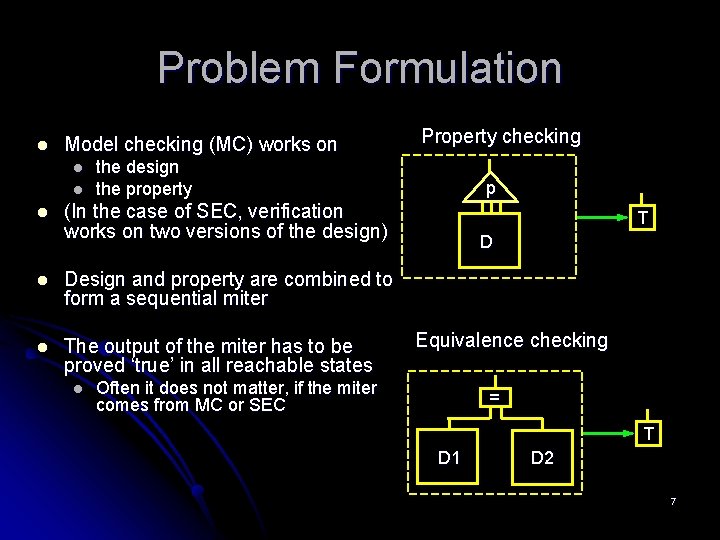

Problem Formulation l Model checking (MC) works on l l l Property checking the design the property p (In the case of SEC, verification works on two versions of the design) l Design and property are combined to form a sequential miter l The output of the miter has to be proved ‘true’ in all reachable states l T D Equivalence checking Often it does not matter, if the miter comes from MC or SEC = T D 1 D 2 7

Outcomes of Verification l Success l l Failure l l The property holds in all reachable states A finite-length counter-example (CEX) is found Undecided l A limit on resources (such as runtime) is reached 8

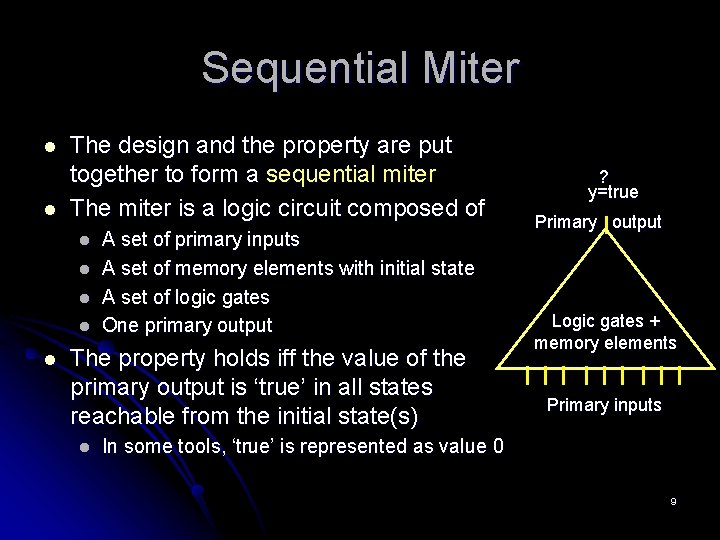

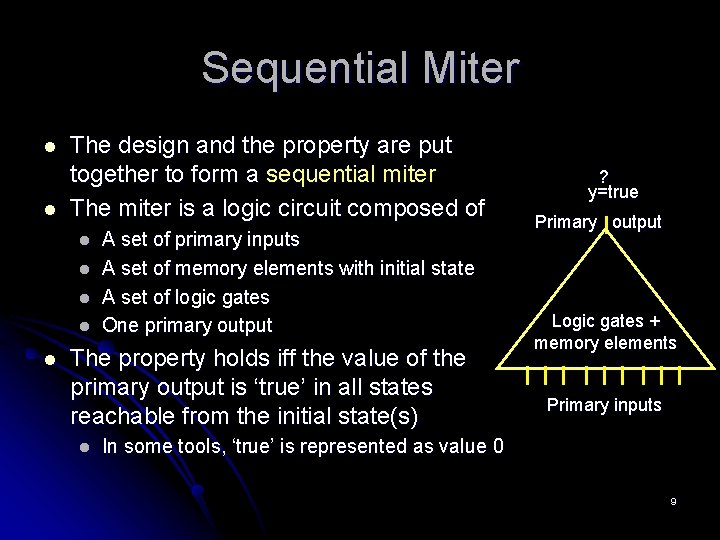

Sequential Miter l l The design and the property are put together to form a sequential miter The miter is a logic circuit composed of l l l A set of primary inputs A set of memory elements with initial state A set of logic gates One primary output The property holds iff the value of the primary output is ‘true’ in all states reachable from the initial state(s) l ? y=true Primary output Logic gates + memory elements Primary inputs In some tools, ‘true’ is represented as value 0 9

Certifying Verification l How do we know that the answer produced by a verification tool is correct? l l If the result is “SAT”, re-run the resulting CEX to make sure that it is valid If the result is “UNSAT”, an inductive invariant may be generated and checked by a third-party tool 10

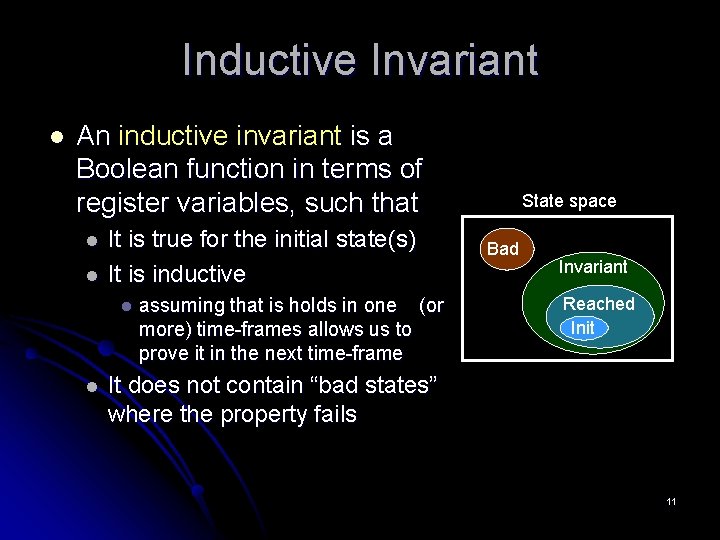

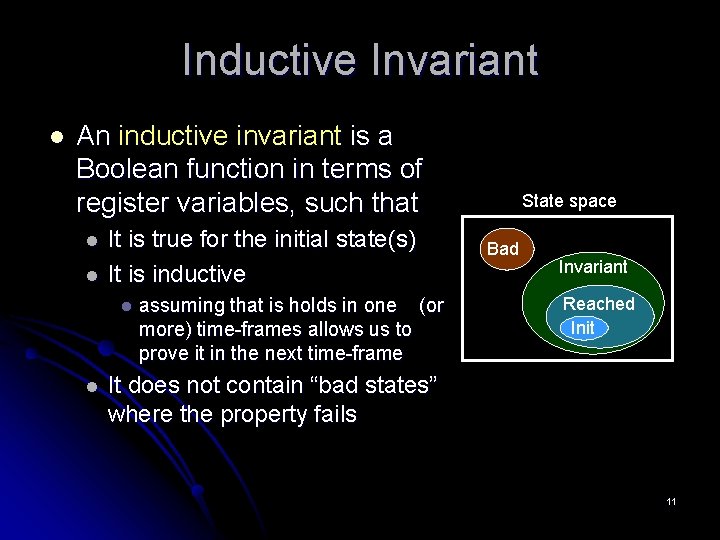

Inductive Invariant l An inductive invariant is a Boolean function in terms of register variables, such that l l It is true for the initial state(s) It is inductive l l assuming that is holds in one (or more) time-frames allows us to prove it in the next time-frame State space Bad Invariant Reached Init It does not contain “bad states” where the property fails 11

Inductive Invariant (cont. ) l l It does not matter how inductive invariant is computed If it is available in any form (as a circuit, BDD or CNF), it can be checked for correctness using a third-party tool l This way, verification proof can be certified Comment 1: If the property is true, the set of all reachable states is an inductive invariant Comment 2: In practice, computing the set of all reachable states is often impossible. In such cases, an inductive invariant can be an overapproximation of reachable states. This allows for proving properties composed of thousands of memory elements, well beyond the limits of exact reachability. 12

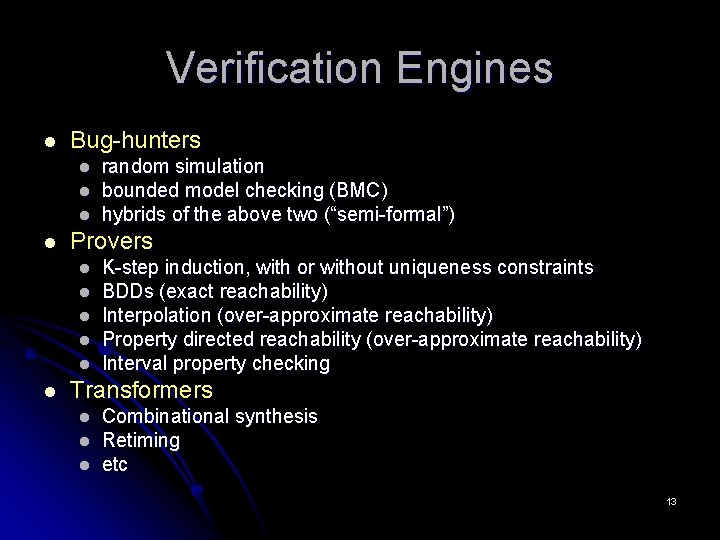

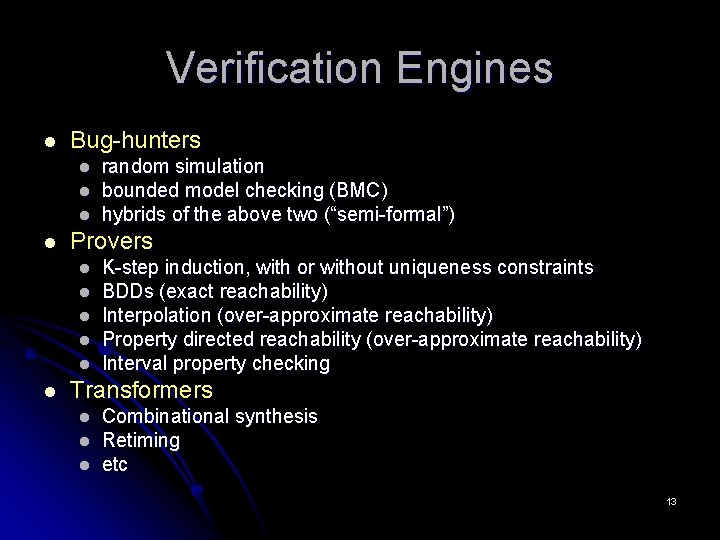

Verification Engines l Bug-hunters l l Provers l l l random simulation bounded model checking (BMC) hybrids of the above two (“semi-formal”) K-step induction, with or without uniqueness constraints BDDs (exact reachability) Interpolation (over-approximate reachability) Property directed reachability (over-approximate reachability) Interval property checking Transformers l l l Combinational synthesis Retiming etc 13

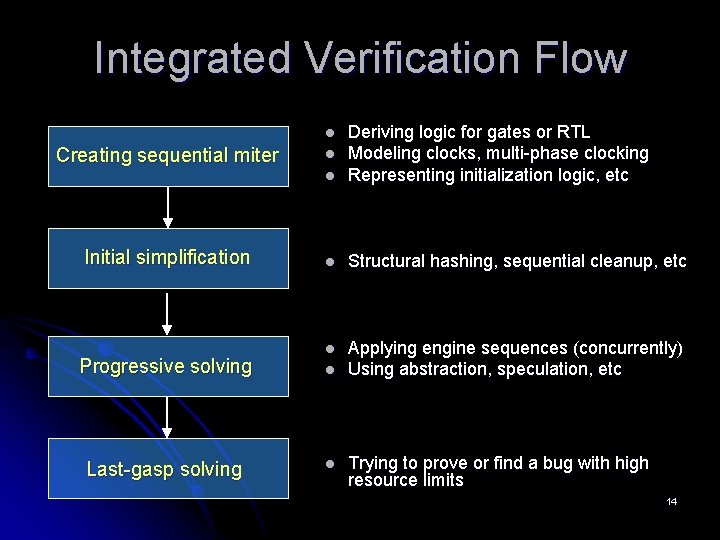

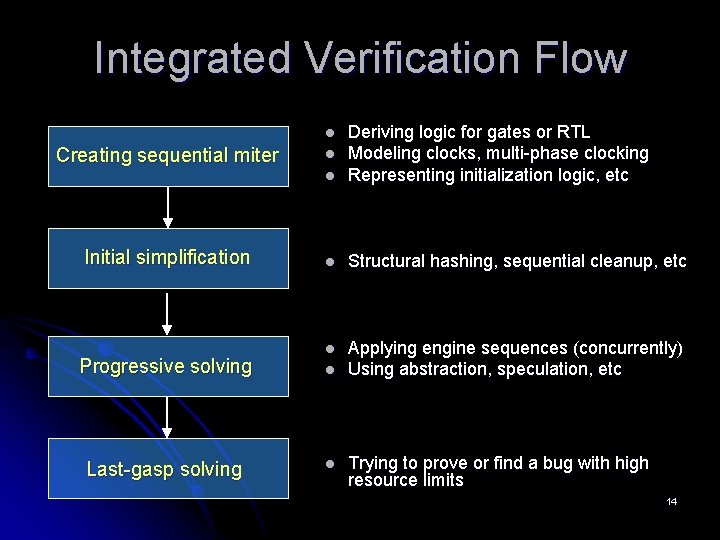

Integrated Verification Flow l Deriving logic for gates or RTL Modeling clocks, multi-phase clocking Representing initialization logic, etc l Structural hashing, sequential cleanup, etc l Applying engine sequences (concurrently) Using abstraction, speculation, etc l Creating sequential miter Initial simplification Progressive solving Last-gasp solving l l l Trying to prove or find a bug with high resource limits 14

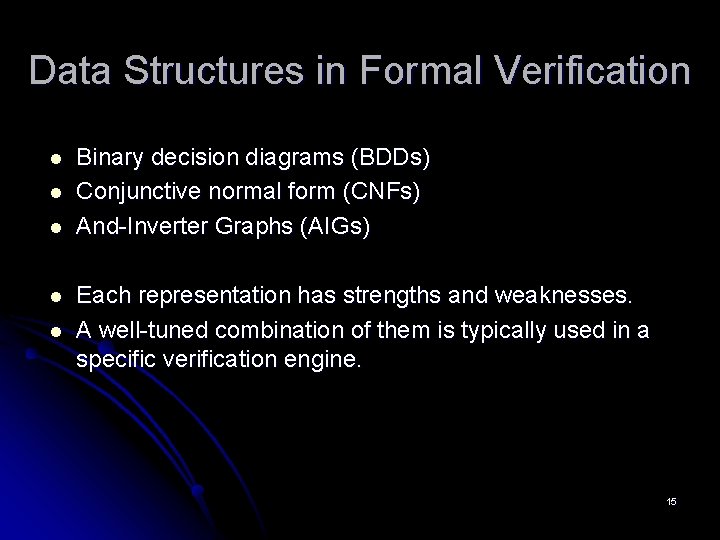

Data Structures in Formal Verification l l l Binary decision diagrams (BDDs) Conjunctive normal form (CNFs) And-Inverter Graphs (AIGs) Each representation has strengths and weaknesses. A well-tuned combination of them is typically used in a specific verification engine. 15

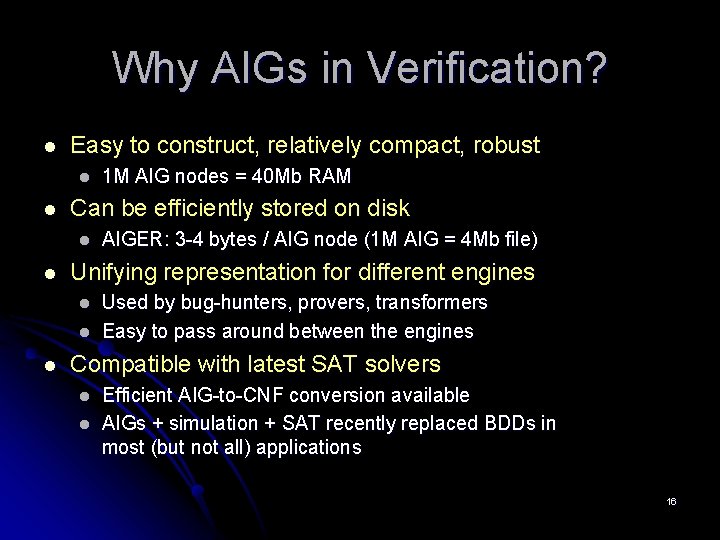

Why AIGs in Verification? l Easy to construct, relatively compact, robust l l Can be efficiently stored on disk l l AIGER: 3 -4 bytes / AIG node (1 M AIG = 4 Mb file) Unifying representation for different engines l l l 1 M AIG nodes = 40 Mb RAM Used by bug-hunters, provers, transformers Easy to pass around between the engines Compatible with latest SAT solvers l l Efficient AIG-to-CNF conversion available AIGs + simulation + SAT recently replaced BDDs in most (but not all) applications 16

Examples of Verification Engines l Transformer l Retiming l Bug-hunter l Simulation l Prover l Property directed reachability (PDR) 17

Retiming Engine l l Uses most-forward retiming to “canonicize” register positions (before register correspondence) Uses min-register retiming (A. Hurst, DAC’ 08) to reduce the number of registers (before signal correspondence) l l l Exposes combinational logic for optimization Minimizes the size of state-space Derives a new register boundary 18

Simulation Engine l Generates random/guided input sequences and simulates them through the design, beginning in the initial state(s), going as far as resource limits allow l l If the property failed, a counter-example is produced If a resource limit is reached, the problem is undecided l Can be used to find bugs in very large designs Can find very deep bugs, which other methods cannot find l Efficient implementation uses l l Bit-parallel simulation Optimized memory management Smart selection of input patterns, based on l l l Scoring Machine learning etc 19

PDR: Property Directed Reachability l Pioneering work of Aaron Bradley l l Remarkable features l l A surprise (3 d place) winner at HWMCC’ 10! Efficiently tackles both SAT and UNSAT instances Lends itself to localization abstraction and parallelism Conceptually simple, relatively tuning-free The best single-engine verification tool to date l l l Outperforms interpolation and induction on average Outperforms simulation and BMC for hard SAT cases Solves many instances previous solved only by BDDs 20

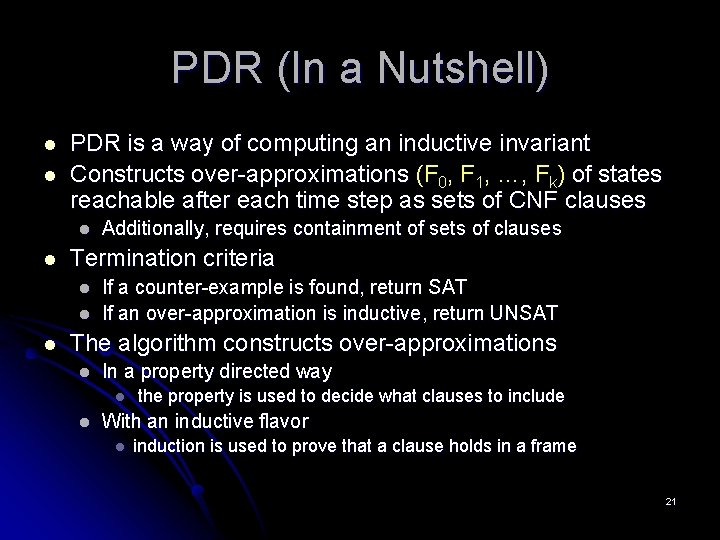

PDR (In a Nutshell) l l PDR is a way of computing an inductive invariant Constructs over-approximations (F 0, F 1, …, Fk) of states reachable after each time step as sets of CNF clauses l l Termination criteria l l l Additionally, requires containment of sets of clauses If a counter-example is found, return SAT If an over-approximation is inductive, return UNSAT The algorithm constructs over-approximations l In a property directed way l l the property is used to decide what clauses to include With an inductive flavor l induction is used to prove that a clause holds in a frame 21

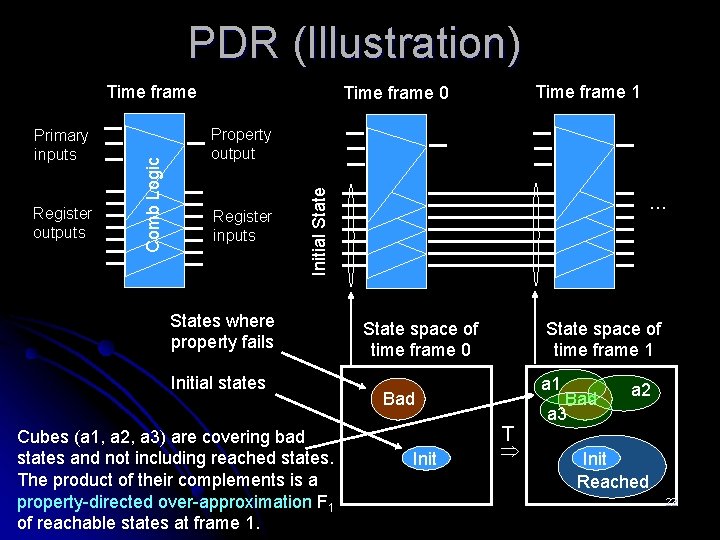

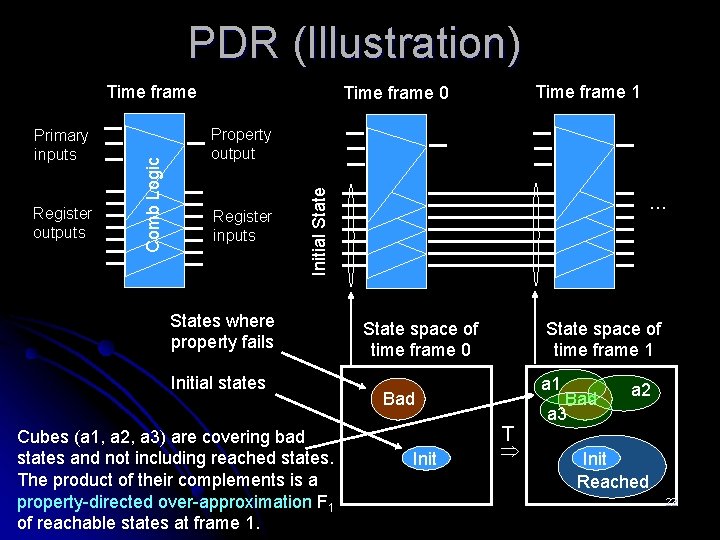

PDR (Illustration) Register outputs Time frame 1 Time frame 0 Property output Register inputs Initial State Primary inputs Comb Logic Time frame States where property fails Initial states Cubes (a 1, a 2, a 3) are covering bad states and not including reached states. The product of their complements is a property-directed over-approximation F 1 of reachable states at frame 1. … State space of time frame 0 State space of time frame 1 a 1 Bad Init T Bad a 3 a 2 Init Reached 22

What’s Next? l In addition to expanding into new directions l l Satisfiability Modulo Theories (SMT) Software verification Using concurrency, etc Improved bit-level engines are in high demand l l l Application-specific SAT solvers A modern BDD package Improved sequential logic simulators l l l combining random, guided and symbolic simulation Improved abstraction refinement … and may be a new engine or two 23

Conclusions l l l Reviewed verification fundamentals Discussed a typical verification flow Considered verification engines l l l Transformers, bug-hunters, provers Introduced a recently-discovered engine (PDR) Looked into the future 24

25

Working for Industry in Academia l l The focus of our research group at Berkeley (BVSRC) shifted to formal verification in 2007 This was motivated by our attempts to apply new sequential synthesis in the verification domain l l Early on we got a number of industrial examples from several companies, which helped us stay on track with industrial requirements l l The effort succeeded in a number of ways Having hard, realistic examples is key for academic research! Currently we support an open-source integrated verification tool distributed as part of ABC l The tools is widely used in industry and academia 26

Abstract l This talk focuses on formal verification of synchronous hardware. We review the definition of sequential equivalence, representations of sequential circuits used in the tools, as well as typical algorithms employed to solve verification problems. The representations discussed include And-Inverter Graphs (AIGs), Binary Decision Diagrams (BDDs), and Conjuntive Normal Forms (CNFs). Different types of verification engines presented include transformers that simplify the problem, bug-hunters that detect failures after a finite number of clock cycles, and provers that prove a property to hold for infinite number of clock cycles. Strengths and weaknesses of different representations and engines are discussed, based on the experience of developing an industrial-strength verification system. 27