The Financial Implications of Corporate Fraud Chen Lin

- Slides: 37

The Financial Implications of Corporate Fraud Chen Lin Chinese University of Hong Kong Frank M. Song University of Hong Kong Zengyuan Sun University of Hong Kong

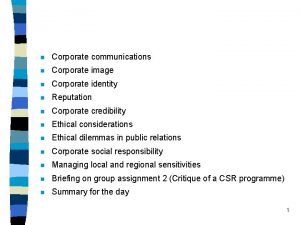

Motivation Corporate fraud is a problematic issue around the world Prevalence Seriousness Corporate fraud: misconduct behavior of firms or managers, which results in material value loss to shareholders, or relevant stakeholders (like creditors, customers, suppliers, and so on), and therefore leads to legal enforcement in shareholder class action lawsuit (Dyck, Morse, and Zingales, 2010)

Motivation Value Implications Firms and managers’ suffering (Feroz, Park, and Pastena, 1991; Du. Charme, Malatesta, and Sefcik, 2004; Karpoff, Lee, and Martin, 2008 a; Karpoff, Lee, and Martin, 2008 b) Much less clear on whether and how corporate fraud affects firm’s financing costs, decisions and polices. Fill the gap by investigating the effect of corporate fraud on cost of debt financing and corporate cash holding policies. the most important external and internal financing

Motivation Fraud damages the ability to raise additional fund Reputation damage: Klein and Leffler (1981) and Jarrel and Peltzman (1985) Information asymmetry: Kreps and Wilson (1982) and Milgrom and Roberts (1982) Might force the firms to pass up future valuable positive NPV projects To keep the liquidity and avoid the underinvestment issues, fraudulent firms might rely more on internal sources of fund in terms of cash holdings accumulation to finance future valuable investments

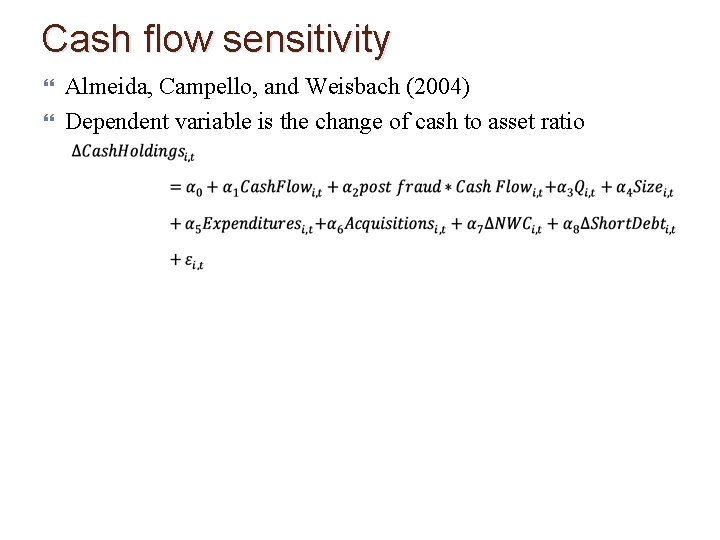

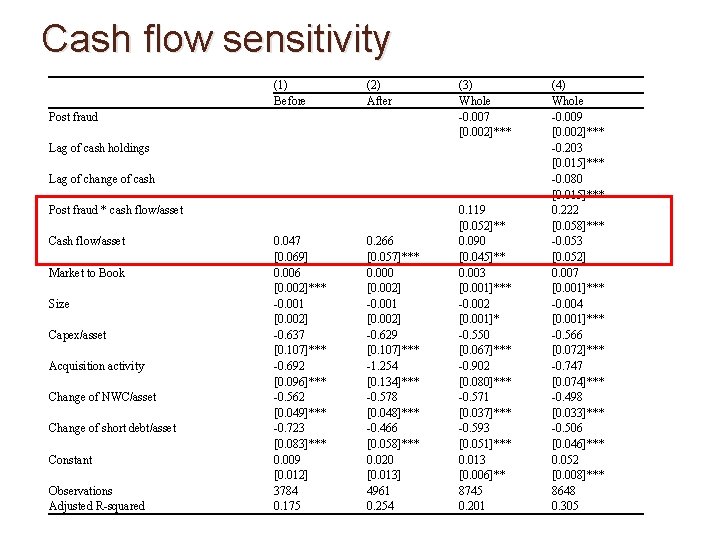

Motivation Fraudulent firms will accumulate more cash and the value of cash increases If the external finance does become more costly after corporate fraud, fraudulent firms are expected to become financially more constrained and as a consequence, accumulate more cash out of cash flow (Almeida, Campello, and Weisbach, 2004) Corporate fraud results in a higher degree of cash flow sensitivity of cash. Despite theoretical appeal, to our knowledge, we are among the first to directly investigate the interactions between costly external finance and corporate cash holdings in the framework of corporate fraud.

Literature & Hypothesis Possible channels: Adjustment and Reputation (Karpoff, Lee, and Martin, 2008 a; Graham, Li, and Qiu, 2008) Adjustment: Readjust upward fraudulent firms’ credit risk (transitory) Reputation: two meanings (the main channel) Increases information asymmetry perceived by outsiders damages firms’ reputation in terms of changes of terms of trade Hypothesis: Corporate fraud results in increase of cost of debt

Literature & Hypothesis Interaction with governance Since corporate fraud results in information asymmetry issue, the outsiders may impose more agency cost if the shareholder right is weak and therefore can not provide sufficient monitoring for fraud issue Agrawal, Jaffe, and Karpoff (1999); Farber (2005) Hypothesis: the costly external finance resulted by corporate fraud is more severe in weak governance firms

Literature & Hypothesis Precautionary motive argument Firms retain cash holdings to better cope with adverse shocks when getting access to capital market is costly (Bates, Kahle, and Stulz, 2009) Firms with greater information asymmetry with outsiders tend to hold more cash (Opler, Pinkowitz, Stulz, and Williamson, 1999) Marginal value of cash increases for firms facing financing frictions because the internal funds enable firms to invest in valuable investments projects which might forgo due to costly external finance (Faulkender and Wang, 2006) Almeida, Campello, and Weisbach (2004) model the precautionary demand of cash and empirically show that financial constrained firms tend to save cash out of cash flow, while unstrained firms do not Hypothesis: Fraudulent firms accumulate more cash and value of cash increases associated with corporate fraud based on the precautionary motive argument Hypothesis: Fraudulent firms display positive cash flow sensitivity of cash after corporate fraud

Literature & Hypothesis Interaction effects: further check the causal effect of costly external finance on cash holdings Costly external finance increases more shock for firms in great need for capital Cash concerns should be more pronounced in industries more dependent on external finance (Rajan and Zingales, 1998) Cash concerns should be more pronounced for firms in weak governance Hypothesis: Based on the precautionary hypothesis, the effect of corporate fraud on cash, value of cash, and cash flow sensitivity of cash should be more pronounced in weak governance firms and in industries in great need of capital

Findings Corporate fraud significantly increases the external financing cost (costly and restrictive external financing) The effect of corporate fraud on cost of debt is more pronounced in weak governance firms Consistent with the precautionary motive argument, fraudulent firms retain more cash and value of cash significantly increases after corporate fraud Corporate fraud contribute to financial constrains as finding that fraudulent firms save more cash out of cash flow The effect on cash, value of cash, and cash flow sensitivity of cash is more pronounced in weak governance firms and firms in great need of capital

Contributions Add to the corporate fraud literature (Karpoff, Lee, and Martin, 2008 a, b; Karpoff and Lou, 2010; Dyck, Morse and Zingales, 2010; Wang, Winton and Yu, 2010) by showing that corporate fraud exerts significant impacts on firm’s financing costs, decisions and policies. Contribute to the liquidity management literature (Campello, Graham, and Harvey, 2010; Campello, Giambona, Graham, and Harvey, 2011) by showing that how fraudulent firms manage internal sources of fund in response to costly external finance.

Data Corporate fraud Stanford Securities Class Action Clearinghouse (SCAC) Dyck, Morse, and Zingales (2010); Wang, Winton, and Yu (2010) ; Lin and Paravisini (2010) and Tian, Udell, and Yu (2011) Others Cost of debt, syndicate bank loan: Dealscan; Compustat; CRSP

Data Non-meritorious (frivolous) litigation problem (Choi, 2004) Restricted to the period after the passage of the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995 (PSLRA), which aims to discourage frivolous litigation (Choi, Nelson, and Pritchard, 2009; Johnson, Kasznik, and Nelson, 2000) Drop cases where the judicial review process leads to their dismissal For settled ones, keep those cases where the settlement is no less than 2 million US dollars, a threshold level of payment which are used to separate meritorious ones from frivolous ones as advocated by Grundfest (1995) and Choi, Nelson, and Pritchard (2009) We exclude the cases with the nature of IPO allocation, mutual fund timing, and analyst malpractices

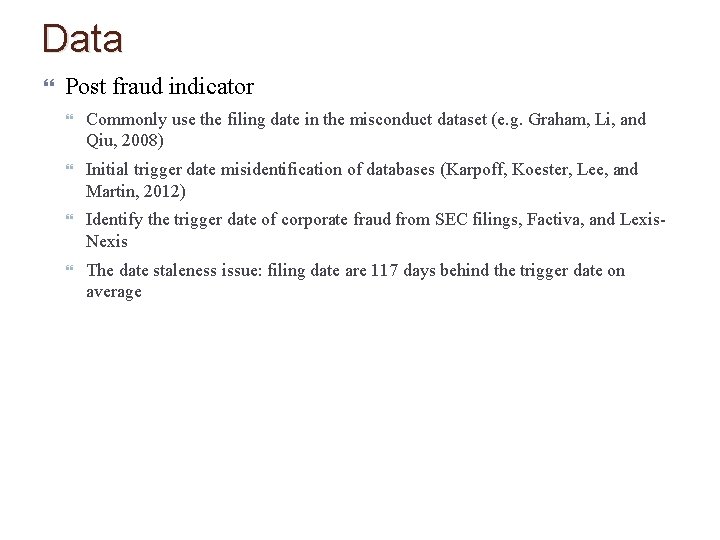

Data Post fraud indicator Commonly use the filing date in the misconduct dataset (e. g. Graham, Li, and Qiu, 2008) Initial trigger date misidentification of databases (Karpoff, Koester, Lee, and Martin, 2012) Identify the trigger date of corporate fraud from SEC filings, Factiva, and Lexis. Nexis The date staleness issue: filing date are 117 days behind the trigger date on average

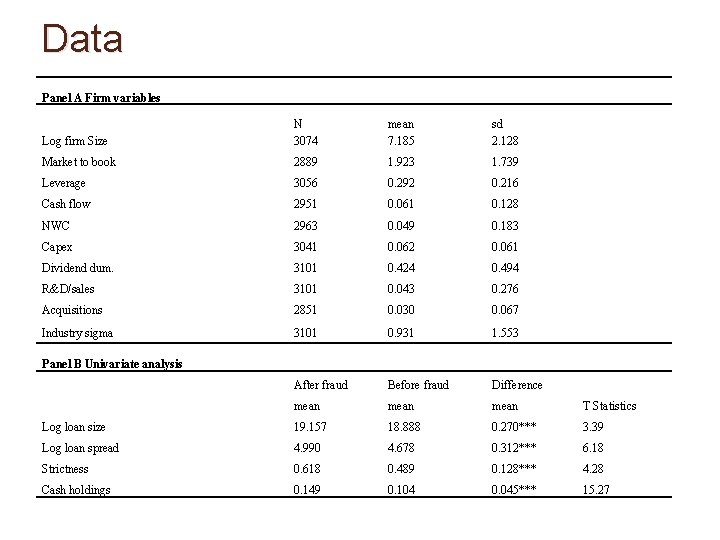

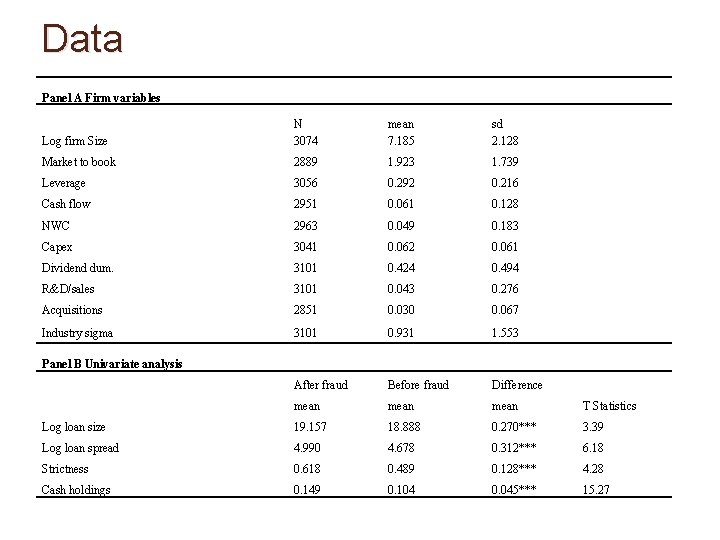

Data Panel A Firm variables Log firm Size N 3074 mean 7. 185 sd 2. 128 Market to book 2889 1. 923 1. 739 Leverage 3056 0. 292 0. 216 Cash flow 2951 0. 061 0. 128 NWC 2963 0. 049 0. 183 Capex 3041 0. 062 0. 061 Dividend dum. 3101 0. 424 0. 494 R&D/sales 3101 0. 043 0. 276 Acquisitions 2851 0. 030 0. 067 Industry sigma 3101 0. 931 1. 553 After fraud Before fraud Difference mean T Statistics Log loan size 19. 157 18. 888 0. 270*** 3. 39 Log loan spread 4. 990 4. 678 0. 312*** 6. 18 Strictness 0. 618 0. 489 0. 128*** 4. 28 Cash holdings 0. 149 0. 104 0. 045*** 15. 27 Panel B Univariate analysis

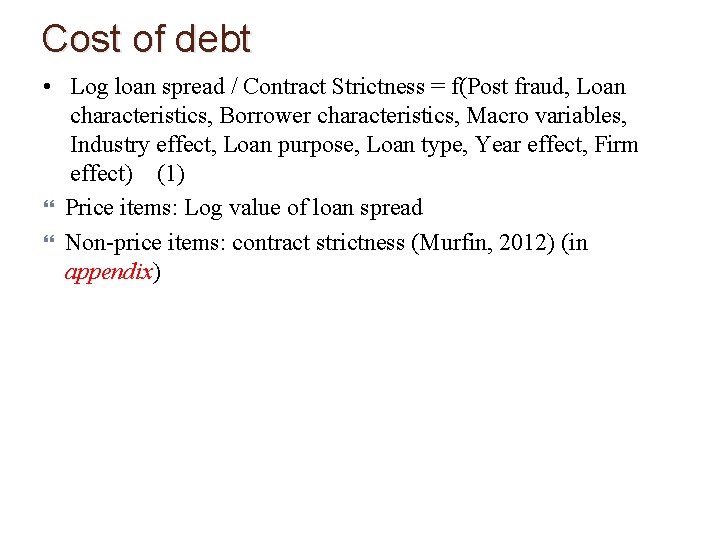

Cost of debt • Log loan spread / Contract Strictness = f(Post fraud, Loan characteristics, Borrower characteristics, Macro variables, Industry effect, Loan purpose, Loan type, Year effect, Firm effect) (1) Price items: Log value of loan spread Non-price items: contract strictness (Murfin, 2012) (in appendix)

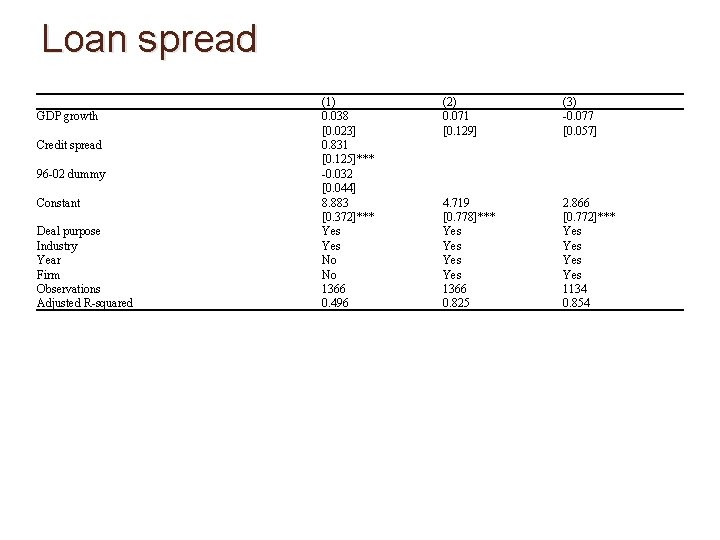

Loan spread Post fraud Log loan size Log maturity Price grid dummy Revolver Num. of lenders Log firm size Leverage Profitability Tangibility Market to book S&P ratings Zscore Cash flow volatility (1) 0. 312 [0. 041]*** -0. 282 [0. 016]*** 0. 163 [0. 033]*** -0. 024 [0. 040] -0. 234 [0. 040]*** -0. 002 [0. 002] (2) 0. 296 [0. 060]*** -0. 071 [0. 021]*** 0. 065 [0. 028]** -0. 022 [0. 037] -0. 121 [0. 027]*** -0. 002 [0. 002] (3) 0. 295 [0. 070]*** -0. 061 [0. 020]*** 0. 055 [0. 031]* -0. 034 [0. 033] -0. 117 [0. 026]*** -0. 001 [0. 001] -0. 047 [0. 063] 0. 635 [0. 197]*** -1. 329 [0. 319]*** 0. 545 [0. 314]* 0. 030 [0. 017]* 0. 191 [0. 030]*** -0. 035 [0. 071] 0. 911 [0. 246]*** -1. 239 [0. 531]** 0. 875 [0. 327]*** 0. 053 [0. 028]* 0. 177 [0. 030]*** -0. 122 [0. 057]** 1. 750 [0. 890]*

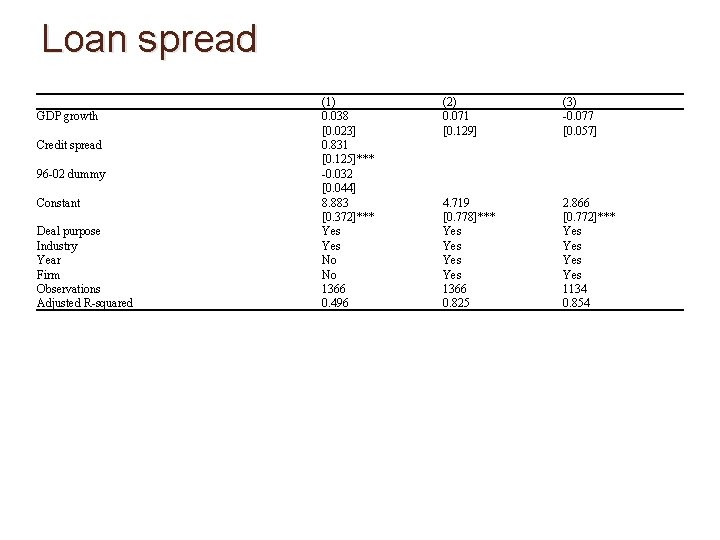

Loan spread GDP growth Credit spread 96 -02 dummy Constant Deal purpose Industry Year Firm Observations Adjusted R-squared (1) 0. 038 [0. 023] 0. 831 [0. 125]*** -0. 032 [0. 044] 8. 883 [0. 372]*** Yes No No 1366 0. 496 (2) 0. 071 [0. 129] (3) -0. 077 [0. 057] 4. 719 [0. 778]*** Yes Yes 1366 0. 825 2. 866 [0. 772]*** Yes Yes 1134 0. 854

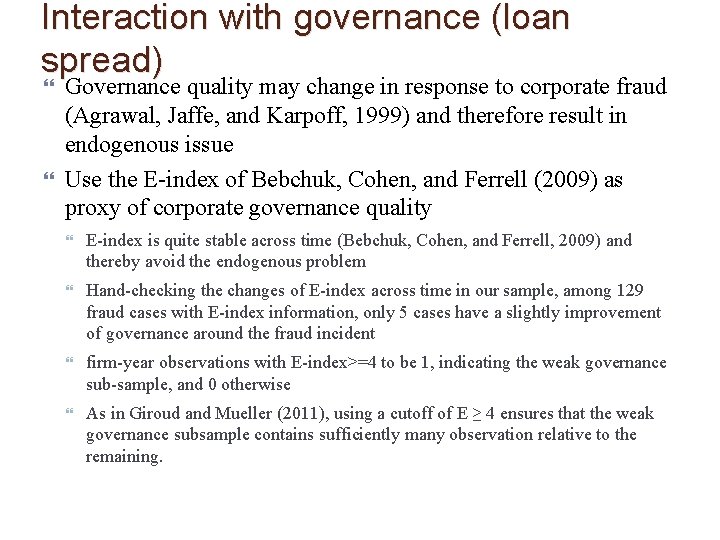

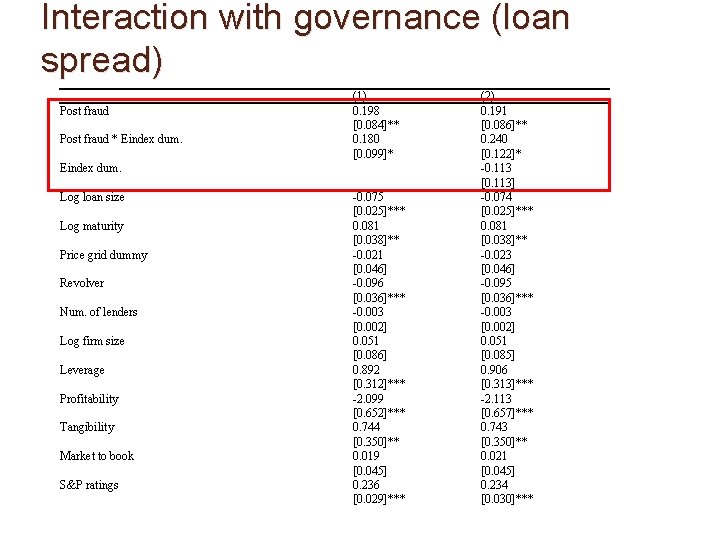

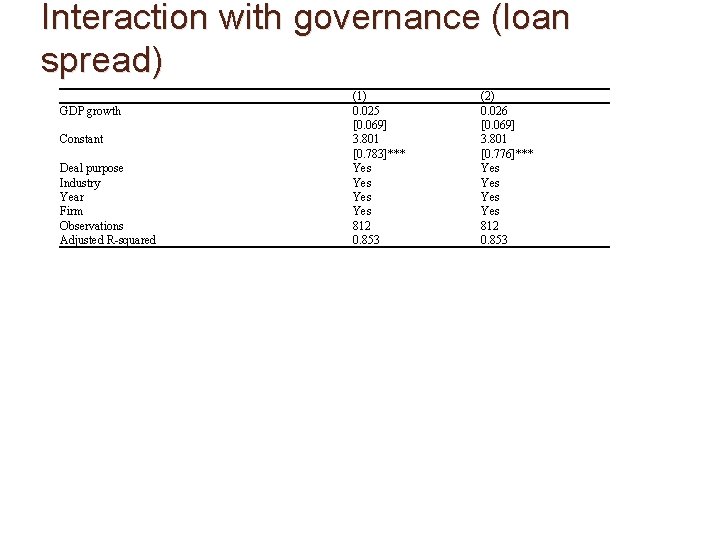

Interaction with governance (loan spread) Governance quality may change in response to corporate fraud (Agrawal, Jaffe, and Karpoff, 1999) and therefore result in endogenous issue Use the E-index of Bebchuk, Cohen, and Ferrell (2009) as proxy of corporate governance quality E-index is quite stable across time (Bebchuk, Cohen, and Ferrell, 2009) and thereby avoid the endogenous problem Hand-checking the changes of E-index across time in our sample, among 129 fraud cases with E-index information, only 5 cases have a slightly improvement of governance around the fraud incident firm-year observations with E-index>=4 to be 1, indicating the weak governance sub-sample, and 0 otherwise As in Giroud and Mueller (2011), using a cutoff of E ≥ 4 ensures that the weak governance subsample contains sufficiently many observation relative to the remaining.

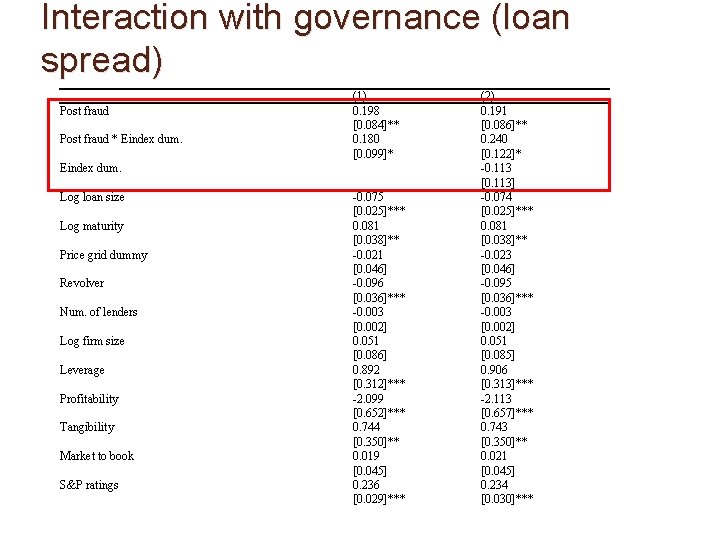

Interaction with governance (loan spread) Post fraud * Eindex dum. (1) 0. 198 [0. 084]** 0. 180 [0. 099]* Eindex dum. Log loan size Log maturity Price grid dummy Revolver Num. of lenders Log firm size Leverage Profitability Tangibility Market to book S&P ratings -0. 075 [0. 025]*** 0. 081 [0. 038]** -0. 021 [0. 046] -0. 096 [0. 036]*** -0. 003 [0. 002] 0. 051 [0. 086] 0. 892 [0. 312]*** -2. 099 [0. 652]*** 0. 744 [0. 350]** 0. 019 [0. 045] 0. 236 [0. 029]*** (2) 0. 191 [0. 086]** 0. 240 [0. 122]* -0. 113 [0. 113] -0. 074 [0. 025]*** 0. 081 [0. 038]** -0. 023 [0. 046] -0. 095 [0. 036]*** -0. 003 [0. 002] 0. 051 [0. 085] 0. 906 [0. 313]*** -2. 113 [0. 657]*** 0. 743 [0. 350]** 0. 021 [0. 045] 0. 234 [0. 030]***

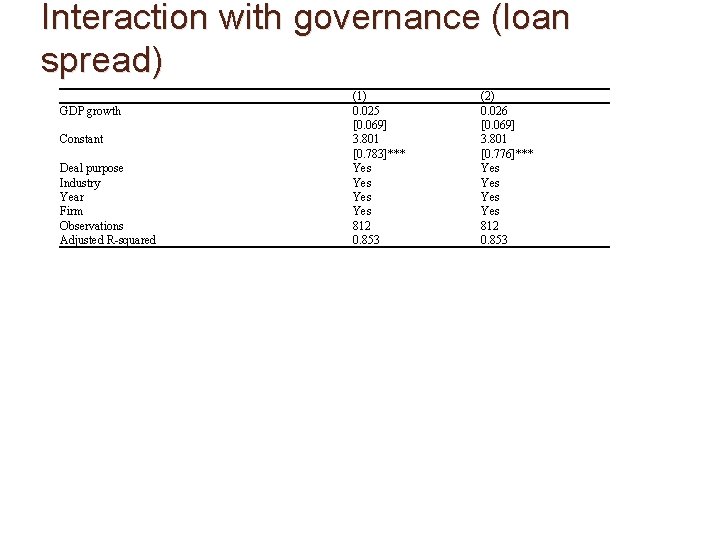

Interaction with governance (loan spread) GDP growth Constant Deal purpose Industry Year Firm Observations Adjusted R-squared (1) 0. 025 [0. 069] 3. 801 [0. 783]*** Yes Yes 812 0. 853 (2) 0. 026 [0. 069] 3. 801 [0. 776]*** Yes Yes 812 0. 853

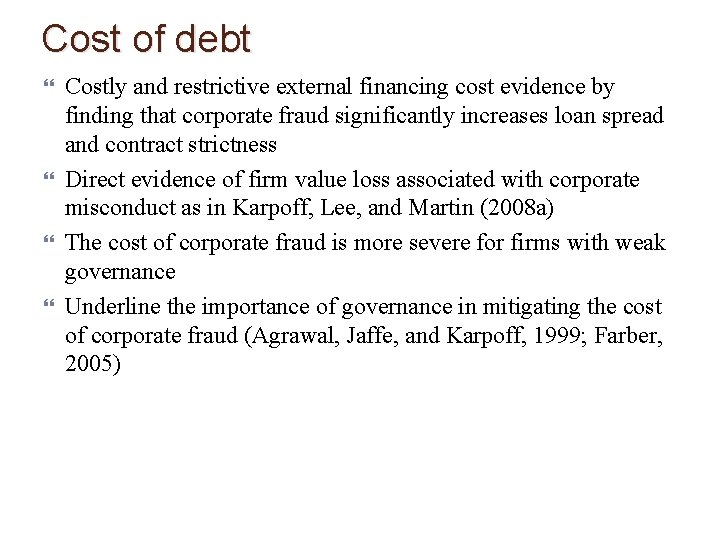

Cost of debt Costly and restrictive external financing cost evidence by finding that corporate fraud significantly increases loan spread and contract strictness Direct evidence of firm value loss associated with corporate misconduct as in Karpoff, Lee, and Martin (2008 a) The cost of corporate fraud is more severe for firms with weak governance Underline the importance of governance in mitigating the cost of corporate fraud (Agrawal, Jaffe, and Karpoff, 1999; Farber, 2005)

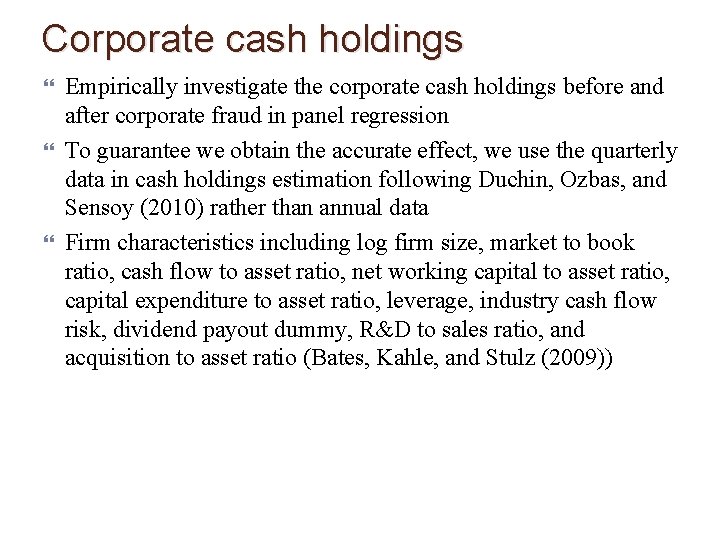

Corporate cash holdings Empirically investigate the corporate cash holdings before and after corporate fraud in panel regression To guarantee we obtain the accurate effect, we use the quarterly data in cash holdings estimation following Duchin, Ozbas, and Sensoy (2010) rather than annual data Firm characteristics including log firm size, market to book ratio, cash flow to asset ratio, net working capital to asset ratio, capital expenditure to asset ratio, leverage, industry cash flow risk, dividend payout dummy, R&D to sales ratio, and acquisition to asset ratio (Bates, Kahle, and Stulz (2009))

Corporate cash holdings Post fraud Size Market to book Leverage Cash flow/NA NWC/NA Capex/NA Divdend dum. R&D/sales Acquisition activity Industry sigma Constant Observations Adjusted R-squared (1) 0. 042 [0. 004]*** -0. 023 [0. 001]*** 0. 063 [0. 002]*** -0. 095 [0. 010]*** -0. 393 [0. 062]*** -0. 133 [0. 013]*** 0. 292 [0. 111]*** 0. 013 [0. 003]*** 0. 559 [0. 047]*** -0. 405 [0. 105]*** 0. 020 [0. 005]*** 0. 201 [0. 013]*** 8789 0. 522 (2) 0. 023 [0. 009]*** -0. 032 [0. 006]*** 0. 046 [0. 005]*** -0. 008 [0. 026] -0. 049 [0. 132] -0. 063 [0. 040] 0. 099 [0. 209] 0. 022 [0. 011]* 0. 479 [0. 171]*** -0. 172 [0. 113] 0. 009 [0. 010] 0. 239 [0. 045]*** 8789 0. 229

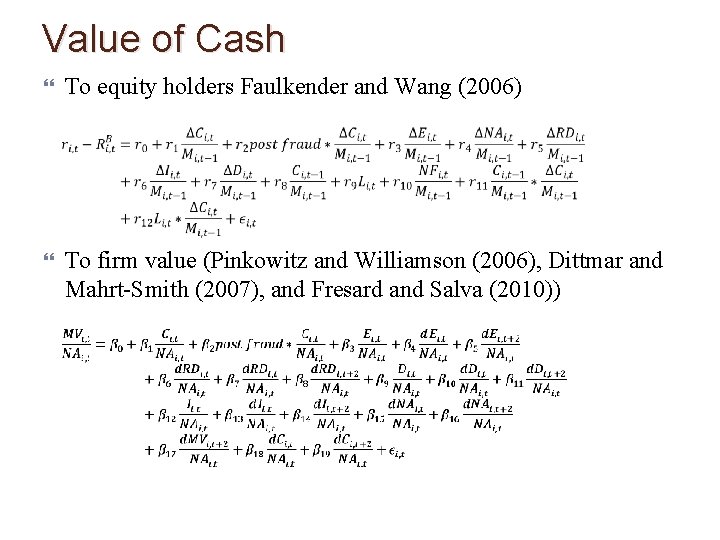

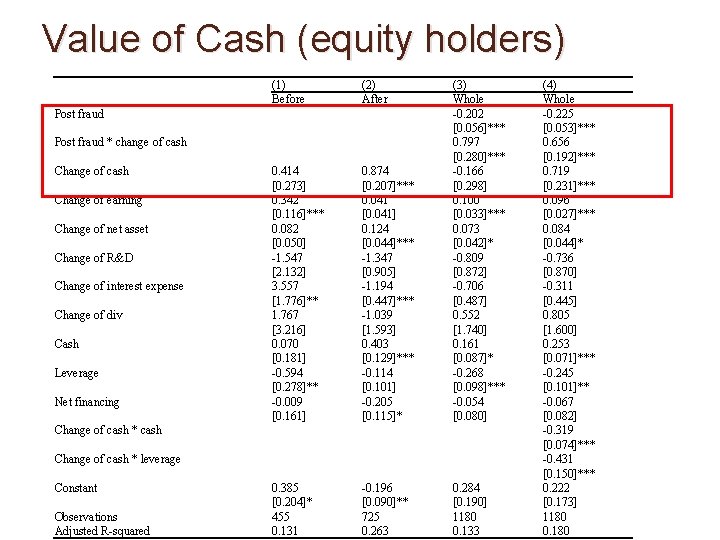

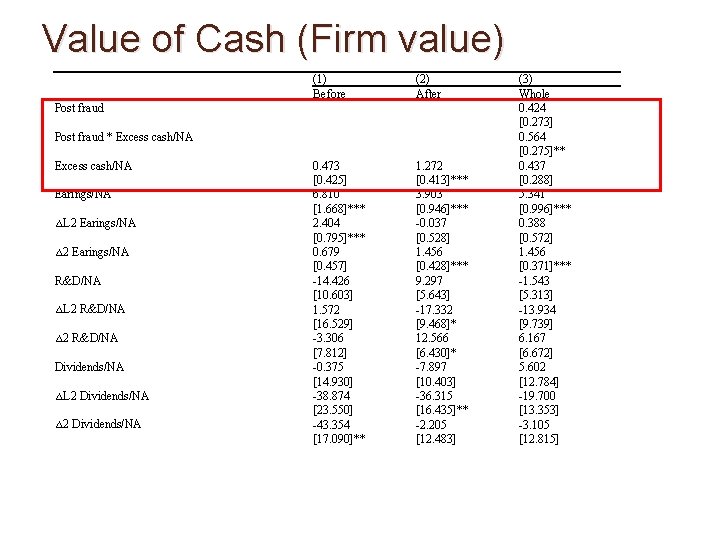

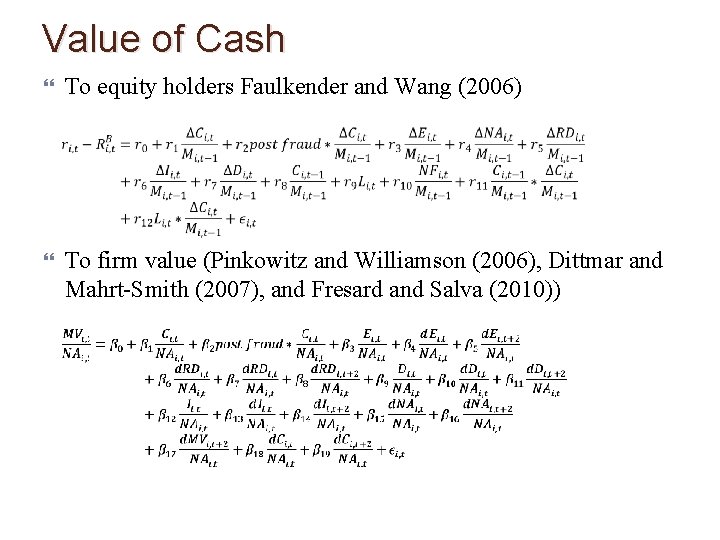

Value of Cash To equity holders Faulkender and Wang (2006) To firm value (Pinkowitz and Williamson (2006), Dittmar and Mahrt-Smith (2007), and Fresard and Salva (2010))

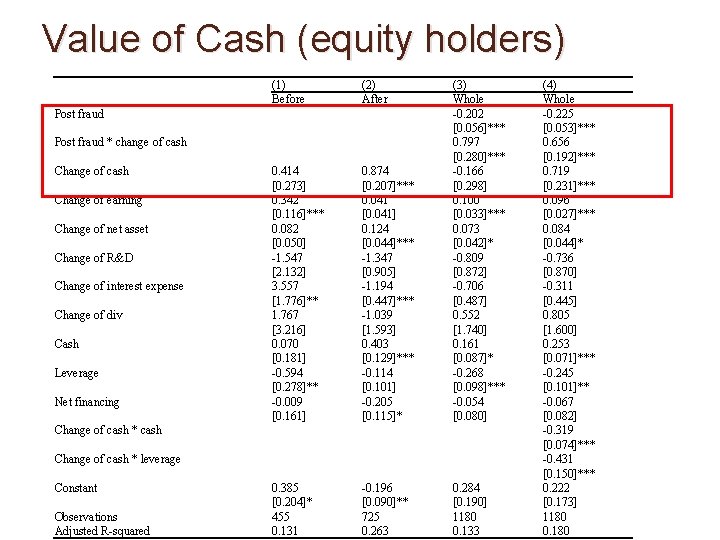

Value of Cash (equity holders) Post fraud (1) Before (2) After 0. 414 [0. 273] 0. 342 [0. 116]*** 0. 082 [0. 050] -1. 547 [2. 132] 3. 557 [1. 776]** 1. 767 [3. 216] 0. 070 [0. 181] -0. 594 [0. 278]** -0. 009 [0. 161] 0. 874 [0. 207]*** 0. 041 [0. 041] 0. 124 [0. 044]*** -1. 347 [0. 905] -1. 194 [0. 447]*** -1. 039 [1. 593] 0. 403 [0. 129]*** -0. 114 [0. 101] -0. 205 [0. 115]* (3) Whole -0. 202 [0. 056]*** 0. 797 [0. 280]*** -0. 166 [0. 298] 0. 100 [0. 033]*** 0. 073 [0. 042]* -0. 809 [0. 872] -0. 706 [0. 487] 0. 552 [1. 740] 0. 161 [0. 087]* -0. 268 [0. 098]*** -0. 054 [0. 080] 0. 385 [0. 204]* 455 0. 131 -0. 196 [0. 090]** 725 0. 263 0. 284 [0. 190] 1180 0. 133 Post fraud * change of cash Change of earning Change of net asset Change of R&D Change of interest expense Change of div Cash Leverage Net financing Change of cash * cash Change of cash * leverage Constant Observations Adjusted R-squared (4) Whole -0. 225 [0. 053]*** 0. 656 [0. 192]*** 0. 719 [0. 231]*** 0. 096 [0. 027]*** 0. 084 [0. 044]* -0. 736 [0. 870] -0. 311 [0. 445] 0. 805 [1. 600] 0. 253 [0. 071]*** -0. 245 [0. 101]** -0. 067 [0. 082] -0. 319 [0. 074]*** -0. 431 [0. 150]*** 0. 222 [0. 173] 1180 0. 180

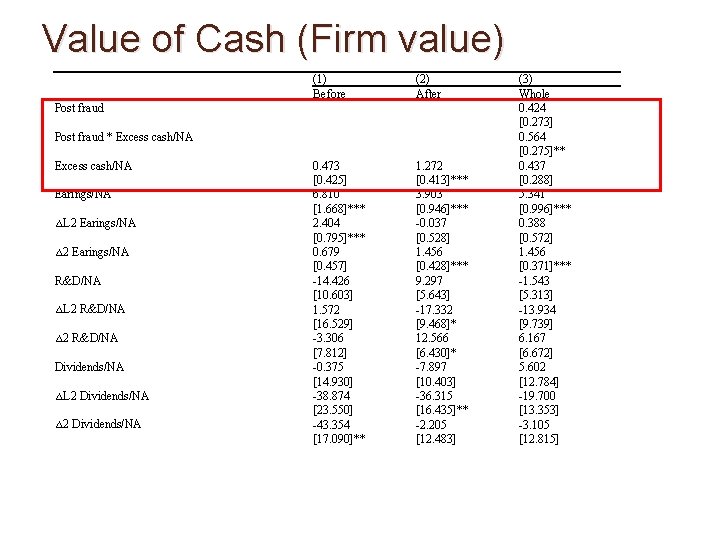

Value of Cash (Firm value) Post fraud (1) Before (2) After 0. 473 [0. 425] 6. 810 [1. 668]*** 2. 404 [0. 795]*** 0. 679 [0. 457] -14. 426 [10. 603] 1. 572 [16. 529] -3. 306 [7. 812] -0. 375 [14. 930] -38. 874 [23. 550] -43. 354 [17. 090]** 1. 272 [0. 413]*** 3. 903 [0. 946]*** -0. 037 [0. 528] 1. 456 [0. 428]*** 9. 297 [5. 643] -17. 332 [9. 468]* 12. 566 [6. 430]* -7. 897 [10. 403] -36. 315 [16. 435]** -2. 205 [12. 483] Post fraud * Excess cash/NA Earings/NA △L 2 Earings/NA △ 2 Earings/NA R&D/NA △L 2 R&D/NA △ 2 R&D/NA Dividends/NA △L 2 Dividends/NA △ 2 Dividends/NA (3) Whole 0. 424 [0. 273] 0. 564 [0. 275]** 0. 437 [0. 288] 5. 341 [0. 996]*** 0. 388 [0. 572] 1. 456 [0. 371]*** -1. 543 [5. 313] -13. 934 [9. 739] 6. 167 [6. 672] 5. 602 [12. 784] -19. 700 [13. 353] -3. 105 [12. 815]

Value of Cash (Firm value) Interests/NA △L 2 NA/NA △ 2 Market value/NA Constant Observations Adjusted R-squared (1) Before 6. 166 [6. 270] 0. 830 [5. 808] 5. 420 [4. 668] -0. 313 [0. 253] 0. 704 [0. 126]*** -0. 274 [0. 060]*** 1. 894 [0. 660]*** 248 0. 555 (2) After 7. 472 [6. 103] 0. 609 [3. 735] 1. 218 [5. 042] -0. 046 [0. 185] 0. 479 [0. 121]*** -0. 327 [0. 046]*** 1. 932 [0. 392]*** 343 0. 532 (3) Whole 3. 964 [4. 483] 0. 292 [3. 250] 1. 079 [3. 341] 0. 023 [0. 135] 0. 480 [0. 081]*** -0. 310 [0. 037]*** 1. 495 [0. 519]*** 591 0. 511

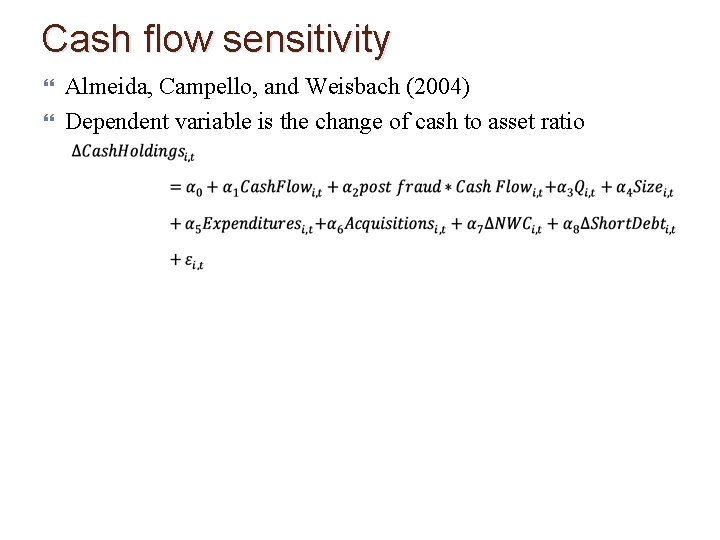

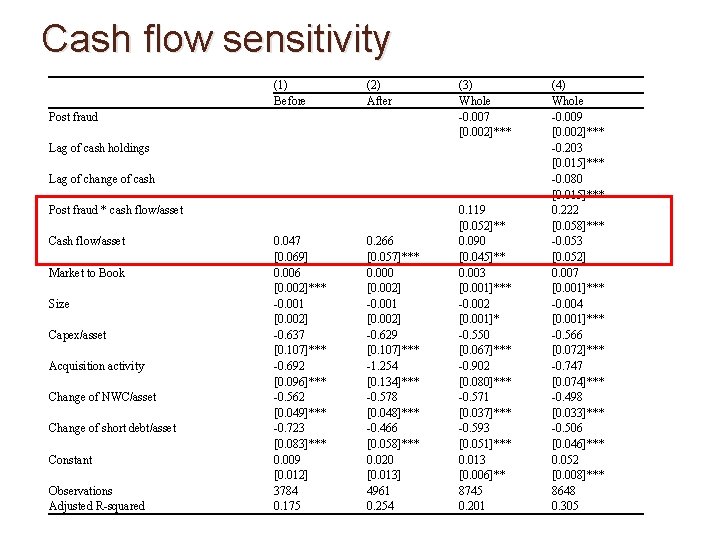

Cash flow sensitivity Almeida, Campello, and Weisbach (2004) Dependent variable is the change of cash to asset ratio

Cash flow sensitivity Post fraud (1) Before (2) After (3) Whole -0. 007 [0. 002]*** Lag of cash holdings Lag of change of cash Post fraud * cash flow/asset Cash flow/asset Market to Book Size Capex/asset Acquisition activity Change of NWC/asset Change of short debt/asset Constant Observations Adjusted R-squared 0. 047 [0. 069] 0. 006 [0. 002]*** -0. 001 [0. 002] -0. 637 [0. 107]*** -0. 692 [0. 096]*** -0. 562 [0. 049]*** -0. 723 [0. 083]*** 0. 009 [0. 012] 3784 0. 175 0. 266 [0. 057]*** 0. 000 [0. 002] -0. 001 [0. 002] -0. 629 [0. 107]*** -1. 254 [0. 134]*** -0. 578 [0. 048]*** -0. 466 [0. 058]*** 0. 020 [0. 013] 4961 0. 254 0. 119 [0. 052]** 0. 090 [0. 045]** 0. 003 [0. 001]*** -0. 002 [0. 001]* -0. 550 [0. 067]*** -0. 902 [0. 080]*** -0. 571 [0. 037]*** -0. 593 [0. 051]*** 0. 013 [0. 006]** 8745 0. 201 (4) Whole -0. 009 [0. 002]*** -0. 203 [0. 015]*** -0. 080 [0. 015]*** 0. 222 [0. 058]*** -0. 053 [0. 052] 0. 007 [0. 001]*** -0. 004 [0. 001]*** -0. 566 [0. 072]*** -0. 747 [0. 074]*** -0. 498 [0. 033]*** -0. 506 [0. 046]*** 0. 052 [0. 008]*** 8648 0. 305

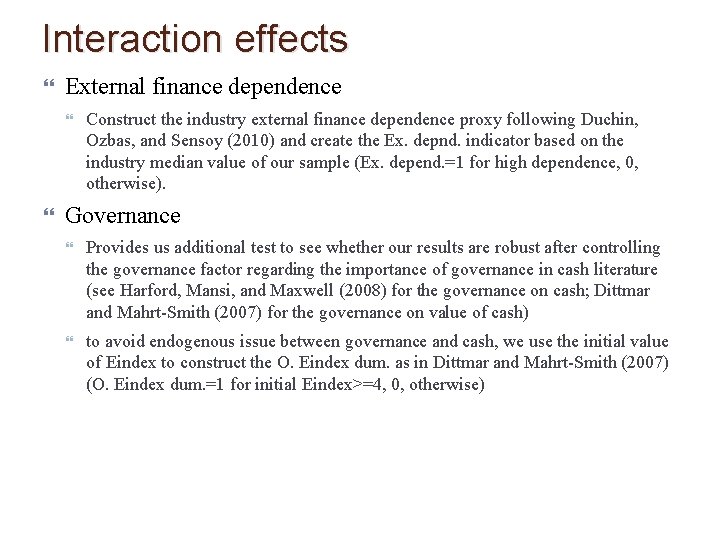

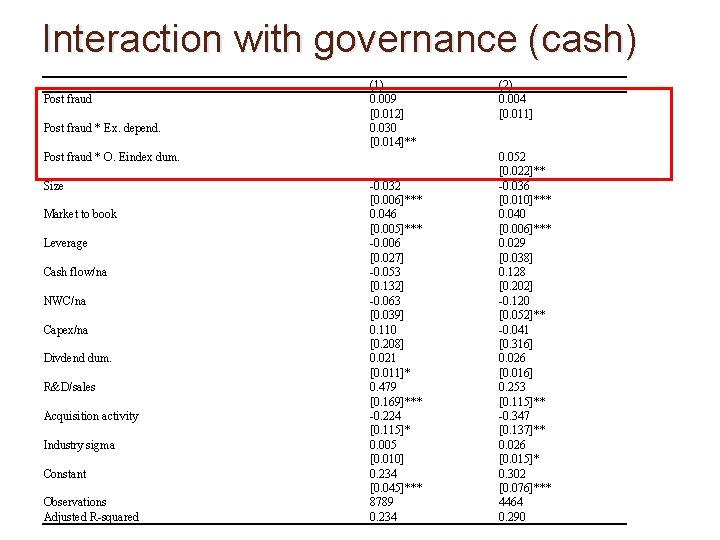

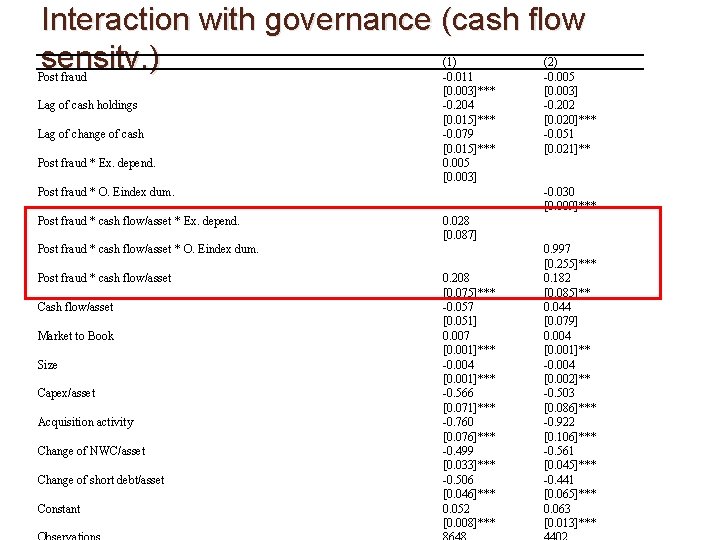

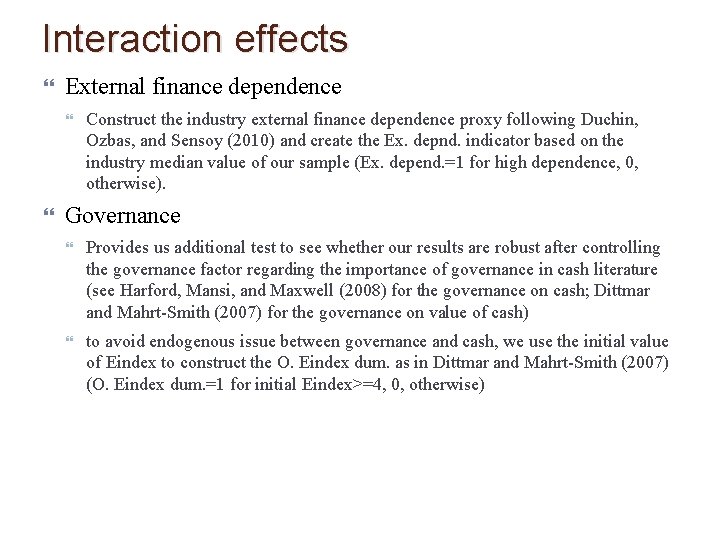

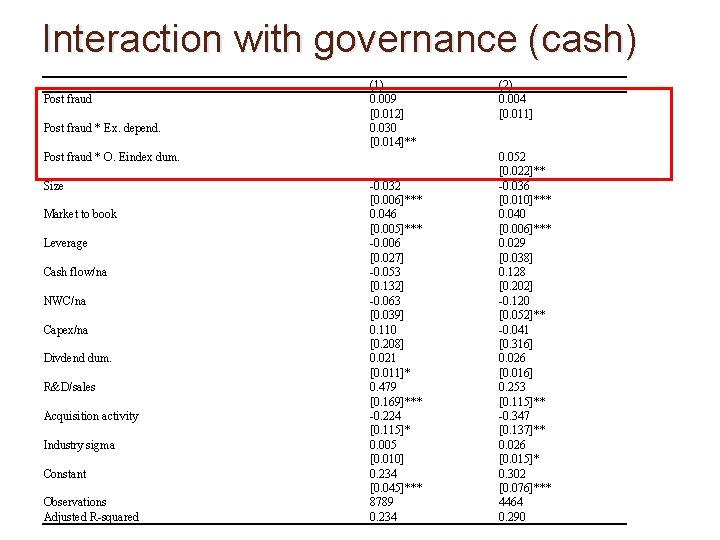

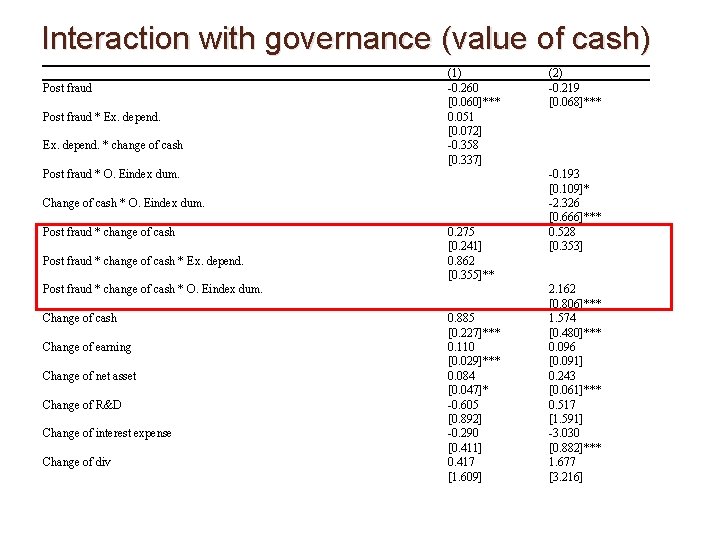

Interaction effects External finance dependence Construct the industry external finance dependence proxy following Duchin, Ozbas, and Sensoy (2010) and create the Ex. depnd. indicator based on the industry median value of our sample (Ex. depend. =1 for high dependence, 0, otherwise). Governance Provides us additional test to see whether our results are robust after controlling the governance factor regarding the importance of governance in cash literature (see Harford, Mansi, and Maxwell (2008) for the governance on cash; Dittmar and Mahrt-Smith (2007) for the governance on value of cash) to avoid endogenous issue between governance and cash, we use the initial value of Eindex to construct the O. Eindex dum. as in Dittmar and Mahrt-Smith (2007) (O. Eindex dum. =1 for initial Eindex>=4, 0, otherwise)

Interaction with governance (cash) Post fraud * Ex. depend. (1) 0. 009 [0. 012] 0. 030 [0. 014]** Post fraud * O. Eindex dum. Size Market to book Leverage Cash flow/na NWC/na Capex/na Divdend dum. R&D/sales Acquisition activity Industry sigma Constant Observations Adjusted R-squared -0. 032 [0. 006]*** 0. 046 [0. 005]*** -0. 006 [0. 027] -0. 053 [0. 132] -0. 063 [0. 039] 0. 110 [0. 208] 0. 021 [0. 011]* 0. 479 [0. 169]*** -0. 224 [0. 115]* 0. 005 [0. 010] 0. 234 [0. 045]*** 8789 0. 234 (2) 0. 004 [0. 011] 0. 052 [0. 022]** -0. 036 [0. 010]*** 0. 040 [0. 006]*** 0. 029 [0. 038] 0. 128 [0. 202] -0. 120 [0. 052]** -0. 041 [0. 316] 0. 026 [0. 016] 0. 253 [0. 115]** -0. 347 [0. 137]** 0. 026 [0. 015]* 0. 302 [0. 076]*** 4464 0. 290

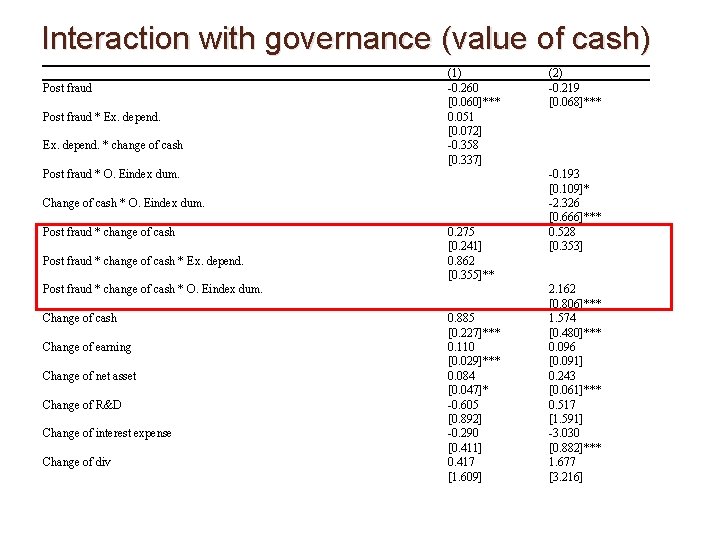

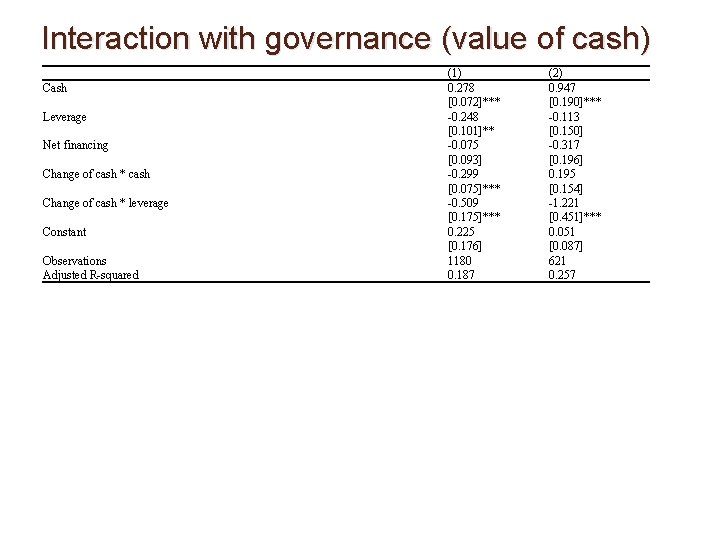

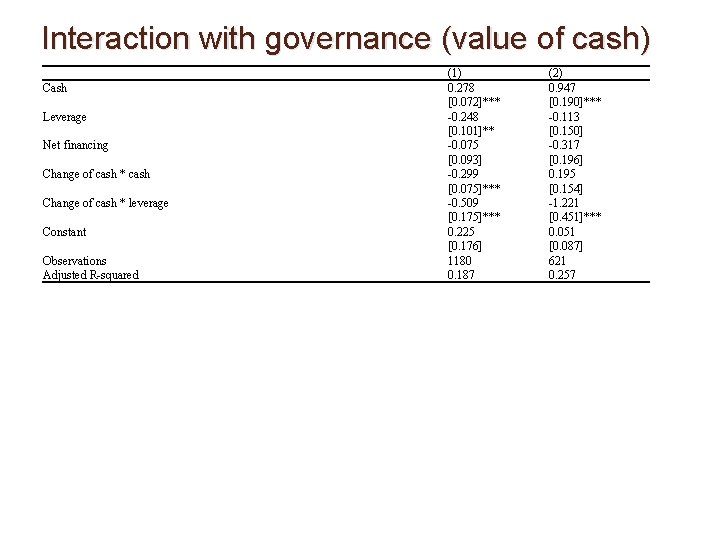

Interaction with governance (value of cash) Post fraud * Ex. depend. * change of cash (1) -0. 260 [0. 060]*** 0. 051 [0. 072] -0. 358 [0. 337] Post fraud * O. Eindex dum. Change of cash * O. Eindex dum. Post fraud * change of cash * Ex. depend. 0. 275 [0. 241] 0. 862 [0. 355]** Post fraud * change of cash * O. Eindex dum. Change of cash Change of earning Change of net asset Change of R&D Change of interest expense Change of div 0. 885 [0. 227]*** 0. 110 [0. 029]*** 0. 084 [0. 047]* -0. 605 [0. 892] -0. 290 [0. 411] 0. 417 [1. 609] (2) -0. 219 [0. 068]*** -0. 193 [0. 109]* -2. 326 [0. 666]*** 0. 528 [0. 353] 2. 162 [0. 806]*** 1. 574 [0. 480]*** 0. 096 [0. 091] 0. 243 [0. 061]*** 0. 517 [1. 591] -3. 030 [0. 882]*** 1. 677 [3. 216]

Interaction with governance (value of cash) Cash Leverage Net financing Change of cash * cash Change of cash * leverage Constant Observations Adjusted R-squared (1) 0. 278 [0. 072]*** -0. 248 [0. 101]** -0. 075 [0. 093] -0. 299 [0. 075]*** -0. 509 [0. 175]*** 0. 225 [0. 176] 1180 0. 187 (2) 0. 947 [0. 190]*** -0. 113 [0. 150] -0. 317 [0. 196] 0. 195 [0. 154] -1. 221 [0. 451]*** 0. 051 [0. 087] 621 0. 257

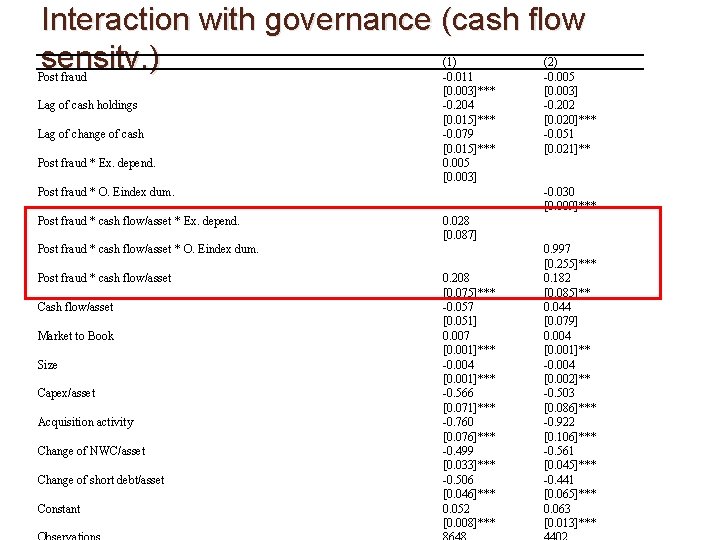

Interaction with governance (cash flow sensitv. ) Post fraud Lag of cash holdings Lag of change of cash Post fraud * Ex. depend. (1) -0. 011 [0. 003]*** -0. 204 [0. 015]*** -0. 079 [0. 015]*** 0. 005 [0. 003] Post fraud * O. Eindex dum. Post fraud * cash flow/asset * Ex. depend. -0. 030 [0. 009]*** 0. 028 [0. 087] Post fraud * cash flow/asset * O. Eindex dum. Post fraud * cash flow/asset Cash flow/asset Market to Book Size Capex/asset Acquisition activity Change of NWC/asset Change of short debt/asset Constant (2) -0. 005 [0. 003] -0. 202 [0. 020]*** -0. 051 [0. 021]** 0. 208 [0. 075]*** -0. 057 [0. 051] 0. 007 [0. 001]*** -0. 004 [0. 001]*** -0. 566 [0. 071]*** -0. 760 [0. 076]*** -0. 499 [0. 033]*** -0. 506 [0. 046]*** 0. 052 [0. 008]*** 0. 997 [0. 255]*** 0. 182 [0. 085]** 0. 044 [0. 079] 0. 004 [0. 001]** -0. 004 [0. 002]** -0. 503 [0. 086]*** -0. 922 [0. 106]*** -0. 561 [0. 045]*** -0. 441 [0. 065]*** 0. 063 [0. 013]***

Conclusions Examine channels through which corporate fraud affects corporate values. Corporate fraud significantly increases the external financing cost In line with the costly and restrictive external finance, fraudulent firms retain more cash to better cope with adverse shocks Consistent with the precautionary motive argument, shareholders and outsiders value more for an additional dollar of cash after corporate fraud Corporate fraud contribute to financial constrains by finding that fraudulent firms save more cash out of cash flow Further confirm by examining the interaction effect son cost of debt, cash, value of cash, and cash flow sensitivity of cash.

Thanks

How do fraud symptoms help in detecting fraud

How do fraud symptoms help in detecting fraud Inverse compositional spatial transformer networks

Inverse compositional spatial transformer networks Chen lin finance

Chen lin finance Chen chen berlin

Chen chen berlin Hui lin financial services professional

Hui lin financial services professional Objective of corporate finance

Objective of corporate finance Financial statements of non corporate entities

Financial statements of non corporate entities Corporate financial policy and the value of cash

Corporate financial policy and the value of cash Corporate financial strategy

Corporate financial strategy Corporate financial reporting and analysis

Corporate financial reporting and analysis Ethiopian government accounting

Ethiopian government accounting Marketing implications

Marketing implications Legal implications in nursing practice

Legal implications in nursing practice Flucytosine mechanism of action

Flucytosine mechanism of action Discussion and implications

Discussion and implications Implications table

Implications table Implications of nativist theory

Implications of nativist theory What is tautology in math

What is tautology in math Educational implications of existentialism

Educational implications of existentialism Implications of quantum entanglement

Implications of quantum entanglement Ranexa nursing implications

Ranexa nursing implications Nursing implications

Nursing implications Multiplicity of evidence

Multiplicity of evidence Future implications definition

Future implications definition Nursing implications for synthroid

Nursing implications for synthroid Guided participation vygotsky examples

Guided participation vygotsky examples Language

Language Implications math

Implications math Trends and issues in nursing

Trends and issues in nursing Database approach to data management

Database approach to data management Novolin n dosage chart

Novolin n dosage chart Bandura social learning theory 1971

Bandura social learning theory 1971 Eng2d media unit

Eng2d media unit Examples of decongestants

Examples of decongestants Medical implications of developmental biology

Medical implications of developmental biology Social implications of computers

Social implications of computers Implikasi etis adalah

Implikasi etis adalah Perennialism metaphysics

Perennialism metaphysics