The Federal Role in Education Introduction Even before

The Federal Role in Education

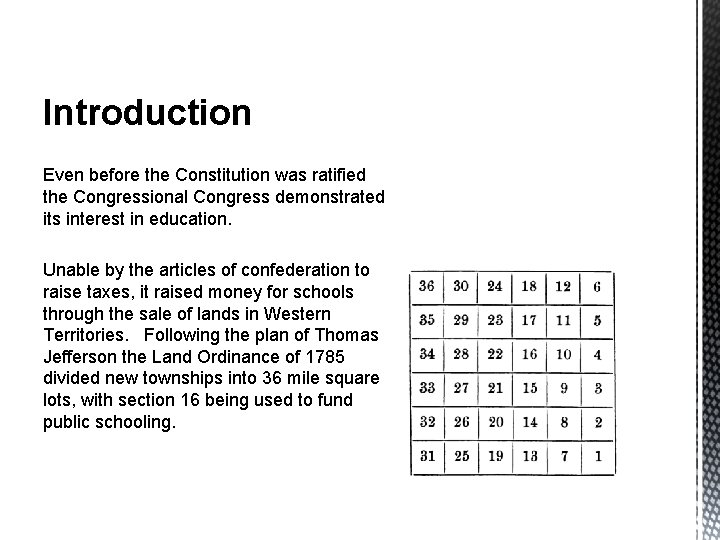

Introduction Even before the Constitution was ratified the Congressional Congress demonstrated its interest in education. Unable by the articles of confederation to raise taxes, it raised money for schools through the sale of lands in Western Territories. Following the plan of Thomas Jefferson the Land Ordinance of 1785 divided new townships into 36 mile square lots, with section 16 being used to fund public schooling.

Two years later The Northwest Ordinance created the first territory, north of the Ohio river. Ratified by the first Congress, this established articles of compact between these lands and the peoples of the United States. This became the blueprint by which the Federal government would expand its sovereign powers westward.

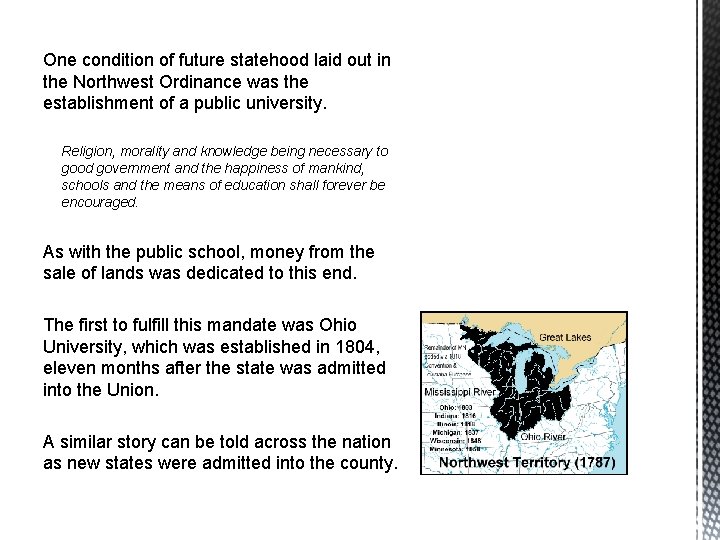

One condition of future statehood laid out in the Northwest Ordinance was the establishment of a public university. Religion, morality and knowledge being necessary to good government and the happiness of mankind, schools and the means of education shall forever be encouraged. As with the public school, money from the sale of lands was dedicated to this end. The first to fulfill this mandate was Ohio University, which was established in 1804, eleven months after the state was admitted into the Union. A similar story can be told across the nation as new states were admitted into the county.

Alabama, for example. Statehood was granted in 1819 and, ten years later, The University of Alabama was opened in 1831—the Harvard of the South! The words of the Northwest ordinance were included in Alabama’s first Constitution, and now sit appropriately above the doorway to Graves Hall, home of the College of Education. Religion, morality and knowledge being necessary to good government and the happiness of mankind, schools and the means of education shall forever be encouraged.

During the first century of the new nation, Congress granted more than 77 million acres to act as an endowment for the support of public schools. Congress doubled the allocation, reserving two lots, 16 and 36, for the support of schools when it established the territorial government of Oregon in 1848. Two years later California followed suit. 5. 5 percent of the public domain in the state went to education. In the desert states of Utah, Arizona, and New Mexico, where land had lass value, each received four sections per township for public schools.

Other Congressional Acts followed. The Morrill Act of 1862 This legislated the sale of lands to support and maintain Universities dedicated to agriculture, the and mechanical arts. ” These A&M schools, without excluding other scientific and classical studies and including military tactic, to teach such branches of learning as are related to agriculture and the mechanic arts, in such manner as the legislatures of the States may respectively prescribe, in order to promote the liberal and practical education of the industrial classes in the several pursuits and professions in life.

A second Morrill Act in 1890 led to the establishment of more than 70 land grant colleges in the South. Each state was required to show either (i) race was not an admissions criterion, or (ii) establish a separate land-grant institution for persons of color. As a result some of the nation’s most prominent HBC were founded.

Alabama A&M University Founded in 1875 by a former slave, William Hooper Councill and opened as the “Huntsville Normal School” in downtown Huntsville. Taught industrial education and became the “State Normal and Industrial School at Huntsville. ” Designated an 1890 land-grant institution by the federal government in February 1891. The school's name was changed to “The State Agricultural and Mechanical College for Negroes. ”

The Smith Hughes Act 1917 Based upon the recommendations of Charles Prosser, it allocated Federal money to support vocational education for children not suited to academic instruction. The government would pay part or all of the salary of appropriately trained teachers.

If a high-school student was taught one class by a teacher paid from Federal vocational funds, they should not receive no more than fifty per cent academic instruction. A “ 50 -25 -25” rule was developed: fifty percent of the time in shop work; twenty-five percent in closely related subjects, and twenty-five percent in academic course work. This program was maintained by cooperating states from the 1920 s to the early 1960 s.

The GI Bill The Servicemen's Readjustment Act of 1944 provided a range of benefits for returning WWII vets, including low-cost mortgages and loans, and financial support to attend university. By 1956, roughly 2. 2 million veterans had made use of these benefits in order to attend college or university. It is claimed that the G. I. Bill was a major factor in the creation of the American middle class, but it also increased racial inequality because many of the Bill’s benefits were not granted to soldiers of color.

The National Defense Education Act (NDEA) Supposedly influenced by the launch of Sputnik, the Act sought to beef up science education in American schools in order to keep up with the Soviets. The act sought to ensure the country had sufficient graduates necessary for national defense. To this end federal help was directed to foreign language and STEM education. It also provided financial support, the “National Defense Student Loan program” to help a growing number of students seeking university education in the 1960 s.

The Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) Passed as part of Johnson's War on Poverty this is the most far-reaching educational legislation ever passed by Congress. It funds primary and secondary schooling emphasizing equality of opportunity for all children. Title I of the act allocates funds to schools and school districts where 40% or more of the students are from low-income families

Since its initial passage in 1965, ESEA has been reauthorized seven times, most recently in January 2001 by George W. Bush as the No Child Left Behind Act. In 2014 nearly $15 Billion were distributed by a variety of formulas to local school districts in order to improve the education of disadvantaged students from birth through the 12 th grade.

The Department of Education One of the most interesting points about these and many other government initiatives is that they have been undertaken without any direct mandate for education. The Tenth Amendment states: The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people. Because the Constitution does not mention education, it is taken to be state and a local responsibility.

Justification for such federal acts, which grew in scale after the Second World War, are typically drawn from the general welfare clause within the Preamble and Article I (on Taxing and Spending), or the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Even so it should be remembered that approximately 92% of money for public schooling comes from State taxation. NCLB amounts to approximately 8% of district monies, although proportionality more in low income areas. Practically, as well and theoretically, education is still very much a state issue. There are however, political groups such as the Cato Institute, which advocates for the repeal of NCLB and constraint on any federal involvement in education.

Given this separation of powers how can we understand the federal government’s increasing involvement in public education? Two areas of influence reveal the logic of this developing presence. Funding and research.

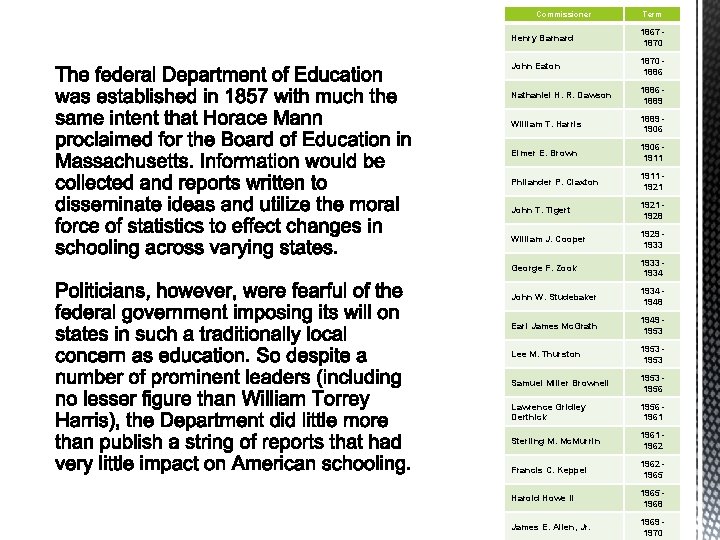

Commissioner Term Henry Barnard 1867 1870 John Eaton 1870 1886 Nathaniel H. R. Dawson 1886 1889 William T. Harris 1889 1906 Elmer E. Brown 1906 1911 Philander P. Claxton 1911 1921 John T. Tigert 1921 1928 William J. Cooper 1929 1933 George F. Zook 1933 1934 John W. Studebaker 1934 1948 Earl James Mc. Grath 1949 1953 Lee M. Thurston 1953 Samuel Miller Brownell 1953 1956 Lawrence Gridley Derthick 1956 1961 Sterling M. Mc. Murrin 1961 1962 Francis C. Keppel 1962 1965 Harold Howe II 1965 1968 James E. Allen, Jr. 1969 1970

This first government body did not have the powers of other departments and was soon reclassified as an office, or alternatively a Bureau. As such its role remained largely advisory.

However, with the Morrill Acts, the Smith. Hughes Act , the GI Bill, and the NDEA increasing administrative and financial responsibilities were added to the original mission. These responsibilities were further expanded in the 1960 s and 1970 s by the educational provisions of the Civil Rights Act and the Title I programs of the ESEA.

In response to these pressures the Carter administration created a cabinet level Department of Education with its own secretary. Citing states’ rights and the dangers of an overreaching Federal bureaucracy Ronald Reagan came into office pledging to dismantle the agency. But is survived, and by the admiration of George W. Bush had greatly expanded with a new research-based agenda to solve the problems that beset the American school.

How did this situation come about? Why did the Federal Government get so involved in shaping public schooling and directing educational research during the 1960 s? How did conservatives undermine this liberal agenda and assert the rights of parents, communities, and states over questions of schooling? And how was it that the Department of Education re-emerged stronger than ever— empowered with a new science of education —in the bipartisan NCLB Act of 2001; the most expansive Federal initiative on education in the nation’s history?

My attention will be on the first part of this story (the 1960 s), but I will conclude by pointing briefly to the subsequent developments that lead to NCLB and the establishment of the Institute for Educational Science (IES) that currently leads the search for evidence-based practices in education.

Research and Money While the story begins with the initial goals of the Department, the 1960 s was the pivotal decade for government support of educational research.

Starting with an annual outlay of $1 million in 1956, a number of research labs were established in Universities across the country. By 1966 $70 million a year was devoted a variety of projects mainly associated with problems related to National Defense Education Act (1958) and the Head Start initiative.

One of the most important results at this time was the brainchild of Francis Keppel (former dean of education at Harvard), who became Commissioner of Education in 1962. Together with Ralph Tyler and John Gardner at the Carnegie Corporation, Keppel proposed the development of a National Testing Program, not to rank children as the SAT did, but to evaluate the progress of the population against academic standards.

State superintendents were terrified by the prospect of national standards, which they thought would cut out their voice in policy making and rain down even more criticism on the back of complaints rising from Sputnik and the Civil Rights Movement.

Eventually, this resistance was overcome and in 1969 The National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) was established. Although it had little immediate impact— publishing oftentimes ambiguous and contested information not obviously applicable to concrete practice—NAEP has become increasingly important as a measure of student performance.

NAEP: A Common Yardstick The National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) is the only nationally representative and continuing assessment of what America's students know and can do in various subject areas. Assessments are conducted periodically in mathematics, reading, science, writing, the arts, civics, economics, geography, and U. S. history. Since NAEP assessments are administered uniformly using the same sets of test booklets across the nation, NAEP results serve as a common metric for all states and selected urban districts. The assessment stays essentially the same from year to year, with only carefully documented changes. This permits NAEP to provide a clear picture of student academic progress over time.

One of Keppel’s ambitions was to use NAEP to focus on the issue of equality of educational opportunity. The 1964 Civil Rights Act mandated a two year review to determine the “availability of equal educational opportunities for individuals by reason of race, color, religion, or national origin. ” Pursuant to this task he appointed James Coleman to survey elementary and secondary schools across the country. It was a massive study, involving over half a million children from 4, 000 schools.

Previously such studies looked at educational inputs – the equality of school facilities, teachers, and instruction. Keppel, however, was determined to introduce the idea of the equality of outcomes. To what extent was the school bringing about actual opportunity?

The major findings of the 700 -page The Coleman Report (1966): The differences between the resources of schools attended by white and black students were far less than anticipated and had a weaker relationship to achievement scores than expected. The more salient variables associated with test scores were: the preparation, verbal abilities, and confidence of teachers; the student’s family background, including class and race; the social class of a student’s classmates; and students’ convictions that they could control their fate. Schools, Coleman asserted, simply could not overcome the effects of enculturation in poor (especially poor black) communities.

If education could not make up for family background what became of the vaulted ideal of the common school? This stimulated fierce debates about whether or not the American Dream was truly open to all? Was the school really a pathway to success for those with intelligence and a positive work ethic? Or did it actually serve as a sorting machine that cemented the status quo and large scale social inequalities?

Most controversially, Coleman reported that federal money advocated by Title 1 of the ESEA (1965) to promote compensatory education programs was proving inconsequential. Such findings, of course, were politically incendiary for the Office of Education given the vast sums of money being spent as a result of Johnson’s War on Poverty.

We should pause to remember the social context. With low paying jobs, little training, decaying infrastructure, broken families, rising poverty, and crime, the largely black ghettos of nation’s big cities had become sites of despair. As revealed by Michael Harrington in The Other America (1962) 50 million people were living in substandard housing with inadequate health care and next to no economic prospects. This “urban crisis” made possible Johnston’s agenda to fight poverty in America.

To address the low achievement educators had developed a new panacea: compensatory education. Grounded in a cultural deficit model, children were viewed as members of an underprivileged or deprived culture.

Social scientists compared the intellectual recourses of middle and working class homes —one was full of books and offered rich educational experiences, the other was academically barren. They compared schools—one encouraged questions, creativity, and inquiry, the other focused on discipline, memorization, and ritualized tasks.

Particularly controversial was the claim that black Vernacular English (BEV)—later known as Ebonics—was an inferior form of speech lacking the conceptual richness of the middle class voice. By stressing the immediate and the concrete, social theorists argued, it simply did not prepare children for the more sophisticated, abstract and expansive language of the school.

Simply put, together with the horrid effects of poverty, the culture of the home failed to correctly stimulate the child’s mind: by the time they arrived in school most poor (especially most poor back) children were already destined to fail. Their lives had to be enriched at the earliest opportunity.

Operation Head Start sought to address this problem. Kindergartens and pre-schools would make up for the poor home environment by providing stimulating conditions for the developing mind.

This demanded new curricula materials and pedagogic methods that would ensure all children learnt. As a result educators developed an interest in children’s learning styles. Perhaps teachers could devise less verbal activities that engaged the visual and physical learning styles of the poor? They also looked at cultural differences that might make the school an alienating place. Whose history, whose interests, whose concerns were being discussed? Could urban kids relate to Dick and Jane?

But these goals were never materialized in practice. Despite all the money spent, few teachers were trained and little or no direction of given on the use of funds. PBS’s Sesame Street may have been the most lasting and successful use of these funds in meeting the original aims of the program.

Given this situation the publication of the Coleman’s Report promised to be explosive. Political events also played into the situation. Mayor Richard Daily, fearful that the Office of Education was going to push Chicago schools to desegregate, pressured Johnson lent on Keppel, who promptly resigned. Stepping into the breech, Keppel’s successor, Harold Howe II, sought to avoid controversy by issuing an executive summary of the Report that deemphasized the study’s importance.

It was Johnson’s former advisor, now Harvard professor, Daniel Patrick Moynihan that resurrected Coleman’s work. Alerted that Coleman’s findings situated the problem of inequality in the home, Moynihan saw the possibility of vindicating his own earlier work, “The Negro Family. ”

According to Moynihan, black social problems arose from the disintegration of the African American family. The fundamental problem, in which this is most clearly the case, is that of family structure. The evidence — not final, but powerfully persuasive — is that the Negro family in the urban ghettos is crumbling.

Measures that have worked in the past, or would work for most groups in the present, will not work here. A national effort is required that will give a unity of purpose to the many activities of the Federal government in this area, directed to a new kind of national goal: the establishment of a stable Negro family structure.

This would be a new departure for Federal policy. And a difficult one. But it almost certainly offers the only possibility of resolving in our time what is, after all, the nation's oldest, and most intransigent, and now its most dangerous social problem.

African Americans, he argued, do not struggle because of segregation or political disenfranchisement, but from the pathological nature of the family. The husband was absent from nearly 2 million of the nation's 5 million homes; and nearly 25% of all births were illegitimate.

Here was a vicious circle enforced and perpetuated by poverty and racial prejudice. The way forward Moynihan explained, was to break this cycle by creating new Federal, state and local government jobs for black men and by creating finical incentives to remain in the family. He proposed a massive stimulus plan to seriously address the root causes of the situation; unemployment, poverty, discrimination, inadequate health care, and poor housing.

Moynihan was roundly—some would say unfairly—criticized by academics and Civil Rights groups for his apparent questioning of black culture. Was he not blaming the victim? In his defense, Moynihan clearly saw these effects as completely structural—the product of lingering racism and economic marginalization. One writer has suggested that his own struggles in a single parent, poverty-ridden family may have heightened his sensitivity to the importance of a father figure in a child’s life.

Inviting Coleman to write up his findings for the journal Public Interest, Moynihan sent the resulting article to a Congressional subcommittee to investigate the “hush up, ” and formed his own study group of academics to explore its findings.

Later published as On Equality of Educational Opportunity (1972), the resulting seminars heralded Coleman’s report as a watershed in social science research. By demonstrating the use of quantitative methods in policy analysis became a touchstone for subsequent research on the problems of race and poverty in America.

Yet the Coleman Report did not bring any radical change in policy. It did make the important case that any measure of educational opportunity must be judged in terms of outcomes.

Equally shocking was Howe’s report to Congress on the success of the Head Start Program. Although a strong supporter of the ESEA Robert Kennedy was skeptical that schools— especially those in the South—would do a good job educating black youth. The nation’s money, Kennedy had feared, might be wasted or worse still, skimmed off for other uses.

Howe’s report described the problems associated with the use of funds and the measurement of their effectiveness. 17, 000 out of 27, 000 districts qualified for an average of $119 per student. But each faced different problems they often made very different use of the money. All he offer was the vague promise that the funds were proving useful. RFK was livid. “You have spent a billion dollars but cannot say whether children can read or not? ” He was left with the damaging– but widely held view that the Office of Education did not have the expertise to evaluate the ESEA.

A fundamental problem for the researchers was the aggregation of data too heterogeneous to compile. It was thus decided that states must only report, not analyze, student data. But as published in devastating 1968 TEMPO Report, findings only served to further undermine the credibility of the Office of Education.

Pupil achievement was declining in Title I schools. Schools with 40 -60% black population had the poorest response to compensatory education programs. Bookkeeping was so confused it was near impossible to tell how funds were being employed.

It became apparent that compensatory education was simply not working. The central approach funded by Title I funds to address equality of opportunity was, by the Office’s own measure, ineffectual.

These debates about school achievement have to be set against detraining race relations that resulted in the summer riots of 1965 and 1966. Support for the liberal reforms passed by the Johnson administration started to erode. African Americans turned to black Nationalism and whites—especially those who supported George Wallace—started to oppose Civil Rights Legislation. Something had to be done to demonstrate progress.

While insisting upon non-discrimination, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 had explicitly outlawed racial balancing. But with the passing of the ESEA the threat of cutting funds to school districts that did not demonstrate true integration now had some teeth.

The Department of Heath, Education and Welfare (HEW) issued guidelines indicating the money would only be given to districts in compliance by the fall of 1967.

Many in Congress read this as an activist agenda, moving from colorblind laws to race conscious policies. Indeed HEW wanted the court to overturn the so called Briggs Dictum which held the intent of Brown was simply to stop segregation, not to force integration.

This was resolved with the momentous Singleton and Jefferson decisions. By 1967 HEW’s standards of integration were being imposed upon school districts across the South. According to Judge Wisdom, “the only school desegregation plan that meets constitutional standards is one that works. ” Wisdom was serious, the courts would work with the HEW to ensure nothing less than full compliance. The era of hiding behind the promise of “All Deliberate Speed” was over.

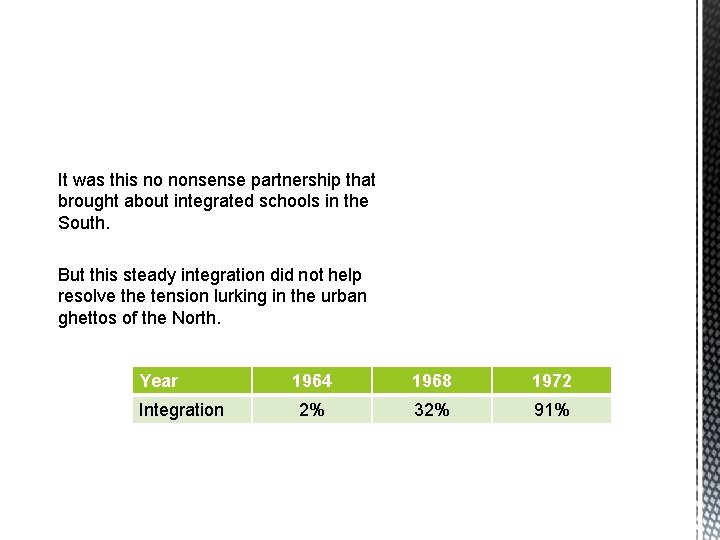

It was this no nonsense partnership that brought about integrated schools in the South. But this steady integration did not help resolve the tension lurking in the urban ghettos of the North. Year Integration 1964 1968 1972 2% 32% 91%

The Coleman Report was mined for any indication of whether or not integration would improve the academic achievement of minority students—it offered little support. Nonetheless a growing consensus emerged that compensatory education was less important then racial integration in promoting the success of African American students.

The 1967 Report by the US Commission on Civil Rights, Racial Isolation in Public Schools, presented a strong statement of this view. Compensatory education programs were ineffective. Focusing on social class coupled with race, it pointed to the growing zoning of cities caused by economic factors and white flight. No schools it concluded, should be less then 50% white.

The landmark Green County decision proved decisive. Here the Supreme Court agreed that racial mixing was necessary to overcome the de jure segregation—and endorsed criteria based upon HEWs guidelines for the establishment of a unitary school district.

But the positive measures pushed by the Department and backed by the courts proved extremely unpopular with the public— especially when busing was used to tackle de facto segregation in the North. With the Millikan v Bradley decision of 1974 the court turned against integration. In a 5 -4 ruling they decided that Brown did not mandate integration as a means to overcome segregation. Conservatives celebrated the end of social engineering by activist judges.

A new threat to the integrationists’ agenda came from Harvard sociologist David Amour. He argued that racial balance did not lead to higher achievement or greater self-esteem among blacks. Nor did it improve race relations. Add to this Colman's 1975 argument that bussing was a self defeating policy because it actually contributed to white flight. The new and important question became, did desegregation address the Achievement Gap? The answer seemed to be no.

One account of the results in Boston reads: Busing has not only failed to integrate Boston schools, it has also failed to improve education opportunities for the city’s black children. When Boston introduced Stanford 9 testing to the public schools in 1996, 94 percent of seventh-graders at Woodrow Wilson Elementary School scored "poor" or "failing" in math, as did 73 percent of fifthgraders at Brighton’s Alexander Hamilton School. At Dorchester’s William E. Endicott School, 95 percent of the fifth-graders scored "poor" or "failing" in reading and 100 percent scored "poor" or "failing" in math.

So, what were the lessons of the 1960 s and 1970 s? Largely negative and problematic: First, social scientists were not able to explain how race and class were related to school achievement. Nor was it clear whether integration led to better performance or increased self esteem.

A common sentiment seemed to be that the drive for integration had taken the focus off academic performance. Many blacks started to ask if success was not more important that integration. Society had changed; opportunities brought about by civil rights made integration seem less important.

Against this growing Conservative backlash the Nixon administration responded with a call for more research on what works in education. Nixon proposed the establishment of a National Institute of Education similar to the highly successful National Institutes of Health (NIH) and National Science Foundation (NSF).

Consider what it would be to have such a prestigious institution directing educational research. Certainly Nixon was sold on the idea. He thought it would produce a cheaper and more efficient means to school improvement than anything the Department of Education could cook up. It would also address the achievement gap: a Science of Education would solve the problem.

Some in Congress argued that aid for education should go directly to colleges and universities rather than a National Institute. But Nixon’s bill was narrowly approved.

Unfortunately the NIE got of to a bad start. It inherited funding problems, failed to recruit qualified staff in a timely way, and failed to articulate any clear goals. Congress was not pleased. When in 1974 the director requested a sizable increase in funding the budget was just about halved! Given commitments to ongoing projects, this left the agency virtually moribund.

Congress it seemed, either did not understand educational research or regarded it as hopelessly inadequate, rife with jargon, mushy politics, trendy theory, and second rate scholarship. This was the time of the “Paradigm Wars” between qualitative and quantitative methods, a debate that for many undermined the foundations of educational research. There was simply nothing concrete to invest in. Funds we cut and projects terminated.

All washed up, the NIE was eliminated in the Education Organization Act of October 1979 that created the Office of Educational Research and Improvement (OERI). The OERI itself had meager funds and was not intended to do much more than maintain statistical data collection necessary for projects such as NAEP.

From Risk to Ruin? This minimal role fit perfectly with the crisis rhetoric of the 1980 s and 1990 s and the conservative attack on bloated and inefficient government. Jimmy Carter had raised the office of Education into a cabinet department. Ronald Regan promised to eliminate it; but never followed through. Regan’s first secretary Terrell Bell did cut many programs—most notoriously student loans—but effectively preserved the department by issuing A Nation at Risk (1983). This was to be an important turning point.

Already NAEP was pointing to declining test scores and decreasing numbers of students taking advanced placement classes. Enrollment in math, science and foreign languages were also diminishing. In clear and bold language Bell presented the stark implications of these trends. “America was committing an act of unthinking, unilateral educational disarmament. ” “The educational foundations of our society is being eroded by a rising tide of mediocrity that threatens our very future as a Nation. ”

What should be done? Graduation standards had to be strengthened, more demanding academic work required, student behavior improved, homework increased, and the school day and school year extended. This implied better paid and prepared teachers, but it was an investment American had to make.

What Bell did not address were the social causes that created these conditions. The focus was on holding children of all backgrounds to higher expectations. In this sense ANAR implicitly endorsed colorblind social policies and directed attention from economic inequality to the problem of reducing the Achievement Gap—which it pointed out had been widening during the 1970 s.

A challenge was set; how can standards help improve the quality of education. Over the next decade a politically attractive solution began to take shape: use modern, market driven reforms to improve or replace public schooling.

When Regan announced William Bennett as Secretary of Education in 1985 the Department effectively served as a bully pulpit for this agenda: the promotion of polices such as “character, content, and choice. ” Standards, testing, and choice promised to end bureaucracy, focus on the needs of poor children, empower parents to take children out of failing schools, and bridge the Achievement Gap.

George H. Bush took office in 1989 determined to turn rhetoric into action. Appointing Lamar Alexander Secretary of Education, within a week he had a blueprint for reform, America 2000, on Bush’s desk. Based upon six national goals (it was not a Federal program) agreed by state governors this initiative included merit pay and alternative certification paths for teachers, a longer school year, national standards in core subjects and the use of achievement tests to measure progress in core subjects. Controversially, it also contained a commitment to school choice. As a result the bill died in the Senate in the face of Democratic opposition.

It had lofty, if not utopian goals. By the Year 2000. . All children in America will start school ready to learn. The high school graduation rate will increase to at least 90 percent. All students will leave grades 4, 8, and 12 having demonstrated competency over challenging subject matter including English, mathematics, science, foreign languages, civics and government, economics, the arts, history, and geography, and every school in America will ensure that all students learn to use their minds well, so they may be prepared for responsible citizenship, further learning, and productive employment in our nation's modern economy. United States students will be first in the world in mathematics and science achievement. Every adult American will be literate and will possess the knowledge and skills necessary to compete in a global economy and exercise the rights and responsibilities of citizenship. Every school in the United States will be free of drugs, violence, and the unauthorized presence of firearms and alcohol and will offer a disciplined environment conducive to learning.

As one of the state governors involved in the framing of American 2000 Bill Clinton sought to continue much of the Bush agenda. Adding two more outcomes, he formulated and pushed the Goals 2000 Bill through Congress. The nation's teaching force will have access to programs for the continued improvement of their professional skills and the opportunity to acquire the knowledge and skills needed to instruct and prepare all American students for the next century. Every school will promote partnerships that will increase parental involvement and participation in promoting the social, emotional, and academic growth of children. One key difference was restriction of choice to public rather than private schools.

It is interesting to follow the evolution of this strategy through the lens of the historian turned government official turned educational critic, Diane Ravitch.

In 1991 Ravitch was appointed as assistant to Secretary Lamar Alexander at the Department of Education and charged with directing OERI. Her pet concern was the development of meaningful National Standards. According to Ravitch standards were the key to reform because they would ensure measurable progress whether in public, private, or charter schools. The problem was that the Federal government did not have jurisdiction over the curriculum; this was clearly a state and local matter. The happy solution, it seemed, was to fund private groups to set the standards and encourage their voluntary adoption by states.

National standards, she reasoned, should indicate, in substantive and concrete terms exactly what a good education comprised. This was the only way to ensure meaningful accountability.

But the politics lie in the details. When academics from the University of California proposed an account of the nation’s past through the lens of race, class, and gender, conservative critics responded that ideology was subverting history and polluting children’s minds with the distorted idea that America was built upon oppression. Hardly the stirring account necessary to instill patriotism and civic responsibility in the next generation.

Interestingly Ravitch had been an outspoken opponent of radical historians who had sought to discredit the democratic role of the American school. But she was far from embracing the kind of knee-jerk, Rush Limbaugh conservatism that would eliminate critical inquiry.

But rather than engaging in political compromise over the curriculum, critics saw red and the issue erupted into a firestorm of controversy. With Republicans lining up against national standards, Clinton decided to steer clear of an ugly debate. Goals 2000 would provide grants and empower states to write their own curriculum. The result, Ravitch argues, was vacuous standards that failed to identify any meaningful content.

When George W. Bush campaigned for office in 2000 one of his main promises was to enact educational reform styled on the success of the system he had overseen as governor of Texas. States would establish their own curricula and write their own tests. They would then be responsible for demonstrating progress toward ensuring every student was proficient in Math and English.

Failure to meet these expectations would result in penalties, including the closing of schools, funded remedial tuition, and the option of moving students elsewhere. It is at this point, Ravitch concludes, “with no underlying vision of what education should be. . . test-based accountability—not standards— became our national education policy. ”

Reflecting on the 1990 s Ravitch explains how powerful the business mentality was. New forms of management promised to transform outmoded administration, replace ineffective personnel, and introduce incentives that would encourage innovation and produce results. This logic was embraced as a new way, a tertium quid between the old left and the old right. “Democrats saw an opportunity to reinvent government; Republicans, a chance to diminish the power of teachers’ unions, which, in their view, protect jobs and pensions while blocking effective management and innovation. ”

In the wake of 9/11 Bush’s plan was embraced in a bipartisan spirit. Driven by high stakes testing, teacher accountability, evidence-based practices, data driven decision making, choice, charter school, and vouchers, Republicans agreed to the biggest expansion in Federal control in the nations’ history, Democrats the rule of the market system. It was not long before Ravitch was completely disillusioned, turning from the government’s greatest booster to its most severe critic. Education, she later realized, was public, moral concern that could not be treated like an economic commodity.

By the turn of the century, however, a powerful lobby of social theorists had successfully promoted evidence-based policy as a scientific means to rational policy reform. No Child Left Behind was thus passed into law on a wave of confidence in the power of experimental research to determine effective or “best” educational practices.

This faith can be seen in the Education Sciences Reform Act of 2002, which established the Institute of Educational Sciences (IES). One of the first actions of the IES was to invite a panel of distinguished scholars—from a variety of fields—to specify exactly what constituted scientific research in education. The result, presented in the 2002 National Research Council report Scientific Research in Education (SRE), was a commitment to rigorous experimental inquiry based— whenever possible—on randomized control studies. This experimental design had revolutionized biomedical research and was being implemented with promising results in a variety of other social fields.

The guiding model was the UK’s Cochrane Collaboration which offered systematic reviews of medical research that could be easily accessed and applied by physicians. Seeking to emulate this approach the Campbell Collaboration was formed to push a similar agenda in America. It played a pivotal role in the policies framed at the IES.

Under this new orthodoxy, randomized trials are the “gold standard” by which a science of education can identify the causal processes underlying effective teaching practices. Within this approach qualitative research serves a handmaiden to the researcher, offering clues of causes to be tested and helping practitioners implement proven practices. But the quantitative analysis of causes is all important. For it is only by capturing causes that effective “treatments” can be known.

The fruit of such studies, like the medical research systemized by the Cochrane Collaboration, is then disseminated to educators through the IES “What Works Clearinghouse. ” It must be said however, that the systematic reviews at the Department of Education lack the depth, power and comprehensiveness of those at the Cochrane Collaboration, and are often presented in technical language not accessible to teachers.

Whether this evidence-driven search for quantifiably justified best practices can achieve the educational ends promised through increasingly scripted pedagogic and curricula reforms is an open question. Ravitch, for one is not hopeful.

- Slides: 104