The evolution and ecological adaptation of bacteria Adam

The evolution and ecological adaptation of bacteria Adam Deutschbauer Arkin lab meeting May 3, 2006

The fundamental goal of genetics Forward genetics – gene/trait mapping Phenotype SELECTION EVOLUTION Genotype Reverse genetics – functional genomics

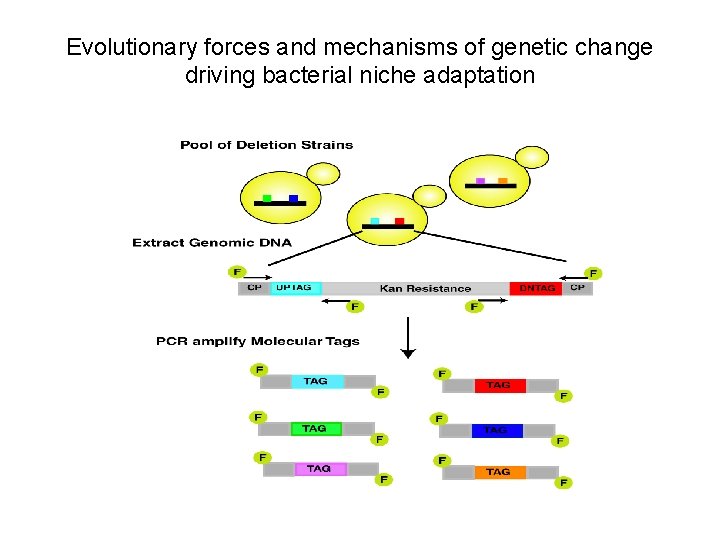

Evolutionary forces and mechanisms of genetic change driving bacterial niche adaptation

A basic outline for addressing the evolution and niche adaptation of bacteria Bork, Science, 2006 • Identify the genetic changes responsible for phenotypic diversity between strains within a bacterial genus • Relate the genotype- phenotype correlations to the ecological context where the strains were isolated from • Use the genotype-phenotype correlations and the tools of comparative genomics to infer mechanisms of evolution

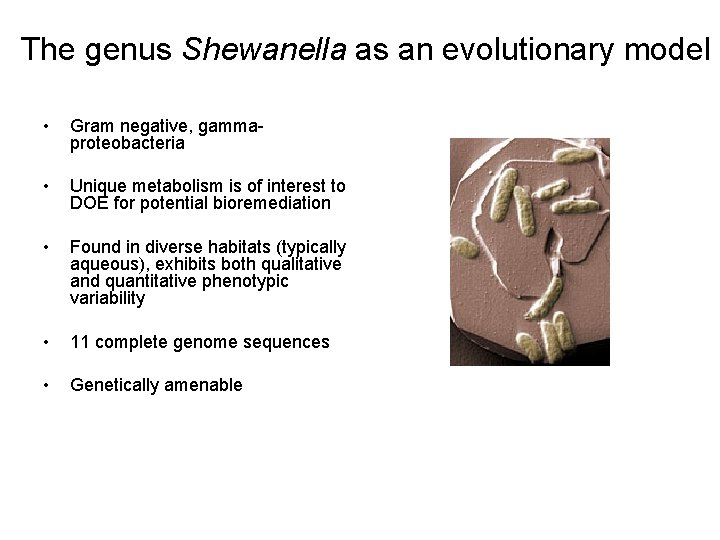

The genus Shewanella as an evolutionary model • Gram negative, gammaproteobacteria • Unique metabolism is of interest to DOE for potential bioremediation • Found in diverse habitats (typically aqueous), exhibits both qualitative and quantitative phenotypic variability • 11 complete genome sequences • Genetically amenable

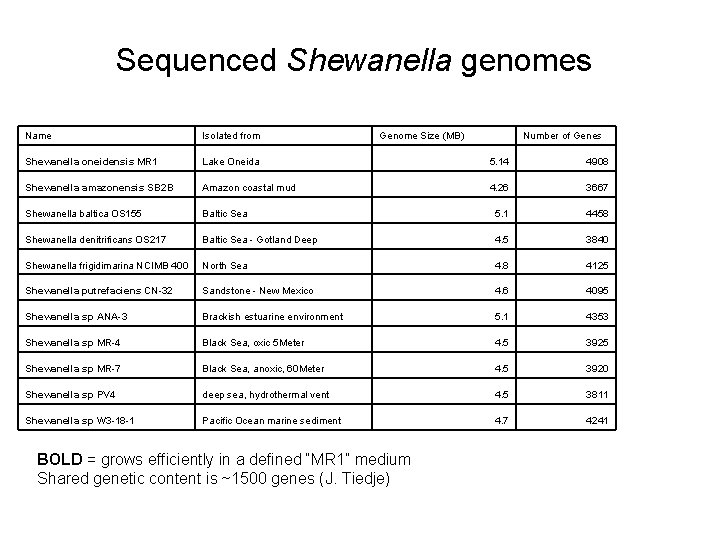

Sequenced Shewanella genomes Name Isolated from Genome Size (MB) Shewanella oneidensis MR 1 Lake Oneida 5. 14 4908 Shewanella amazonensis SB 2 B Amazon coastal mud 4. 26 3667 Shewanella baltica OS 155 Baltic Sea 5. 1 4458 Shewanella denitrificans OS 217 Baltic Sea - Gotland Deep 4. 5 3840 Shewanella frigidimarina NCIMB 400 North Sea 4. 8 4125 Shewanella putrefaciens CN-32 Sandstone - New Mexico 4. 6 4095 Shewanella sp ANA-3 Brackish estuarine environment 5. 1 4353 Shewanella sp MR-4 Black Sea, oxic 5 Meter 4. 5 3925 Shewanella sp MR-7 Black Sea, anoxic, 60 Meter 4. 5 3920 Shewanella sp PV 4 deep sea, hydrothermal vent 4. 5 3811 Shewanella sp W 3 -18 -1 Pacific Ocean marine sediment 4. 7 4241 BOLD = grows efficiently in a defined “MR 1” medium Shared genetic content is ~1500 genes (J. Tiedje) Number of Genes

Genetic relatedness of Shewanella strains 16 S r. RNA gene gyr. B We need a better tree Tiedje, PNAS, 2001

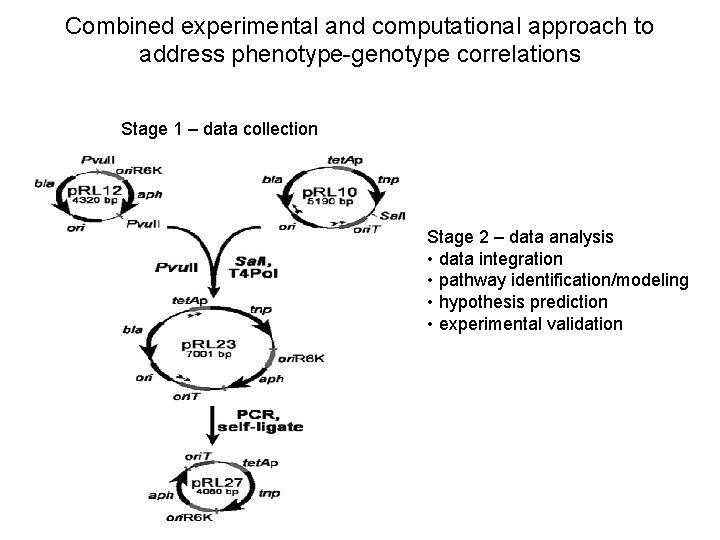

Combined experimental and computational approach to address phenotype-genotype correlations Stage 1 – data collection Stage 2 – data analysis • data integration • pathway identification/modeling • hypothesis prediction • experimental validation

Physiological profiling • Purpose: identify environmentally interesting conditions in which the Shewanella strains differ in phenotype both qualitatively and quantitatively • Method: Growth curve analysis using microplate readers and phenotype microarray technology (Biolog)

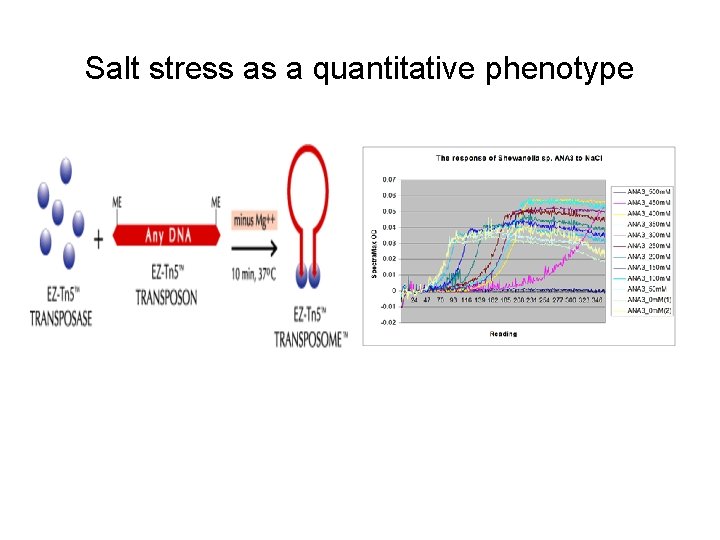

Salt stress as a quantitative phenotype

Additional phenotypes to test • Utilization of different metabolites using phenotype microarray (PM) technology (biology in collaboration with Y. Tang and J. Keasling, PM in collaboration with D. Joyner and T. Hazen) • Stress conditions (p. H, temperature, oxygen limitation, heavy metal exposure, UV light) • Utilization of alternative electron acceptors during anaerobic growth (would be a future collaboration – experiments are tricky) • I am only going to work on a handful of phenotypes (one quantitative and a few qualitative)

Comparative Genome Analysis • Purpose 1: Annotate the genomes, predict genes/pseudogenes/operons/regulons, find orthologous genes in other genomes/etc. , define metabolic pathways (This is essential for interpretation of the experimental data, model construction, and the formation of testable hypotheses) • Purpose 2: Determine if the observed differences in phenotype between the Shewanella strains can be explained from the genome sequence alone (This is essential so that I don’t waste my time) • Method: Tools available through Microbes. Online database and the expertise available from the Arkin GTL team.

Gene expression analysis • Purpose: Will provide insight into the evolution of gene expression and how it relates to phenotype (for that reason alone, it is worth doing the experiment) • Simply reports the RNA abundance of all genes (is often used to indirectly infer gene function) Method: Agilent spotted oligo microarrays, custom designs, in-house instrumentation for array processing

Mutagenesis • Purpose: Mutant phenotypes offer direct insight into gene function • Method: Global, random mutagenesis using a barcoding strategy to quantitatively measure fitness (need to develop because all existing methods are insufficient to rapidly mutagenize and study multiple genomes simultaneously)

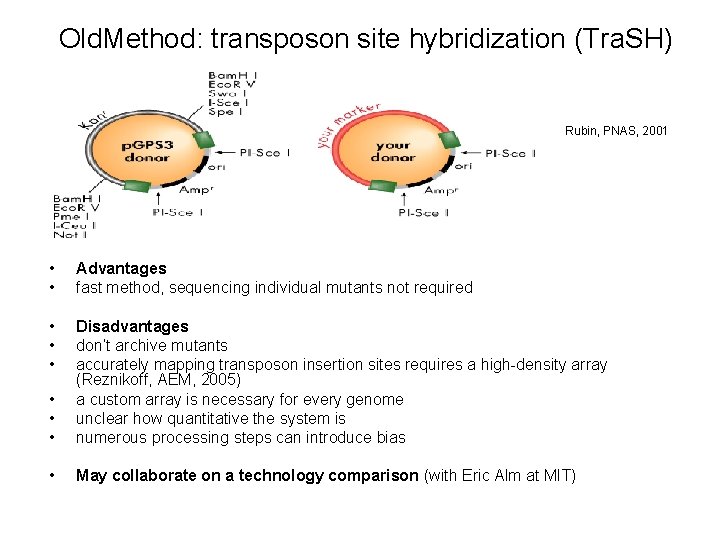

Old. Method: transposon site hybridization (Tra. SH) Rubin, PNAS, 2001 • • Advantages fast method, sequencing individual mutants not required • • • Disadvantages don’t archive mutants accurately mapping transposon insertion sites requires a high-density array (Reznikoff, AEM, 2005) a custom array is necessary for every genome unclear how quantitative the system is numerous processing steps can introduce bias • May collaborate on a technology comparison (with Eric Alm at MIT)

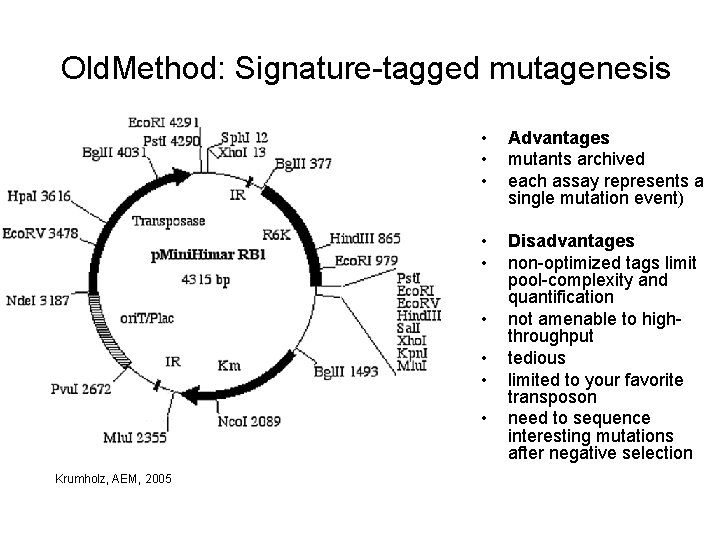

Old. Method: Signature-tagged mutagenesis • • • Advantages mutants archived each assay represents a single mutation event) • • Disadvantages non-optimized tags limit pool-complexity and quantification not amenable to highthroughput tedious limited to your favorite transposon need to sequence interesting mutations after negative selection • • Krumholz, AEM, 2005

My (unnamed) mutagenesis method • • • Advantages strains archived universal to any mobile genetic element high-throughput optimized to be quantitative • Disadvantages • tedious • interesting mutants need to be sequenced at the end

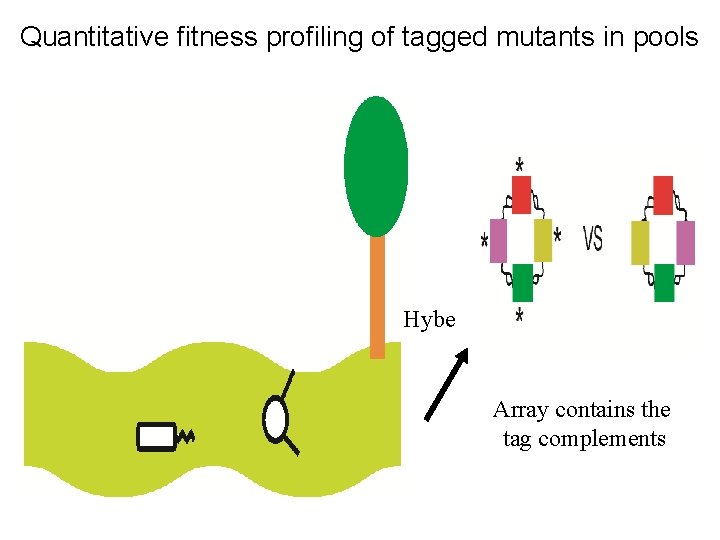

Quantitative fitness profiling of tagged mutants in pools Hybe Array contains the tag complements

Tag cloning strategy 96 tag pairs have been cloned and sequence verified (~60% have no mutations).

Gateway cloning with a universal tag collection

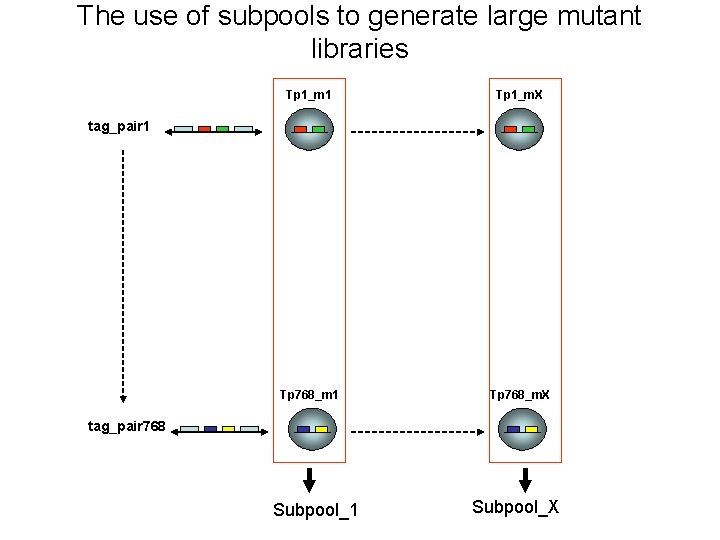

The use of subpools to generate large mutant libraries Tp 1_m 1 Tp 1_m. X Tp 768_m 1 Tp 768_m. X tag_pair 1 tag_pair 768 Subpool_1 Subpool_X

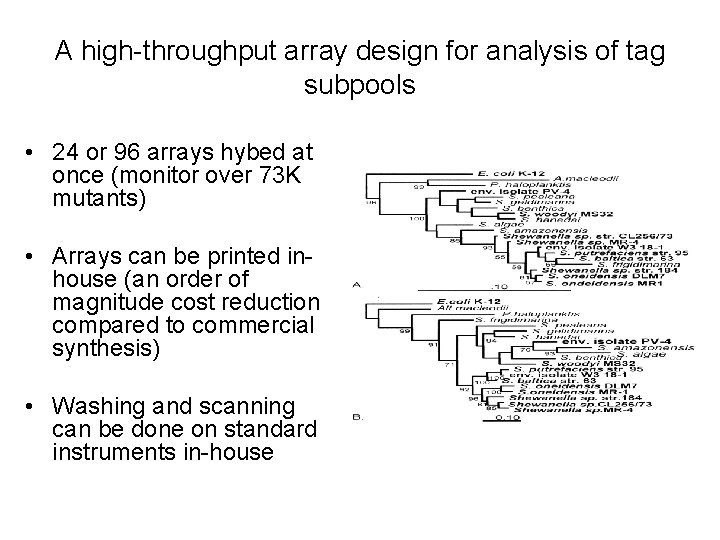

A high-throughput array design for analysis of tag subpools • 24 or 96 arrays hybed at once (monitor over 73 K mutants) • Arrays can be printed inhouse (an order of magnitude cost reduction compared to commercial synthesis) • Washing and scanning can be done on standard instruments in-house

Practical considerations • Labor (use a robot/undergrads, plating and picking colonies is a one-time effort per genome) • Number of mutants necessary (aim for ~25, 000 per genome) • Sample tracking (bar-code all plates, use an automated liquid-handling system, set up a database to keep track of experiments, spot-check individual mutants on occasion) Biggest issue • Interesting strains need to be sequenced to determine which gene(s) was targeted by the transposon

Mapping transposon insertion sites by sequencing • In the end, the amount of sequencing I’ll do is not so bad for the number of phenotypes/genomes I plan on studying as a postdoc (on the order of a few thousand reactions total) • Standard pyrosequencing using the same primers may reduce cost and help simplify the process • For the amount of money spent on certain bacterial projects, doing 20, 000 single pass sequence reads to generate a comprehensive mutant library for quantitative parallel analysis is worth it Ausubel lab, Harvard

Additional applications of a flexible molecular tag strategy • Identify alleles contributing to quantitative phenotypic variation between Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains in a single test tube assay (three years of grad school work in a single month) • Analysis of haploinsufficient phenotypes (particularly drug sensitivity) in the fungal pathogen Candida albicans (consequences of heterozygosity in a obligate diploid)

Proteomics and metabolomics • Available in house through collaboration with the Keasling lab • May be useful after generating preliminary data with gene expression and mutant analysis

The immediate future (~6 months) • Physiological profiling (phenotype arrays), pick the “final” phenotypes for analysis • “Basic” computational analysis of the Shewanella genomes for gene content, etc. • Develop the 96 -well tag microarray (as a collaboration) • Gene expression profiling of a handful of Shewanella genomes (4 maximum) • Clone the rest of the tag modules (as a collaboration)

The more distant future • Extend these studies to a pathogenic bacteria with extensive genetic diversity (such as Helicobacter pylori) • Compare the genetic changes underlying lab evolution (strictly through vertical descent) and natural evolution • Go back to the natural environment • Can we take strains from one phenotypic state to another (more on the engineering side, requires an understanding of the compatibility and evolution of regulatory systems)?

Acknowledgments • LBL (Adam Arkin, Morgan Price, Paramvir Dehal, Keith Keller, Janet Jacobsen, Yinjie Tang, Dominique Joyner, Terry Hazen) • Toronto (Guri Giaever, Corey Nislow) • EMBL (Lars Steinmetz) • Stanford (Ron Davis, Molly Miranda, Julia Oh, Raquel Tamse, Michelle Nguyen, Eula Fung, Keith Anderson)

- Slides: 29