THE DATA OF MACROECONOMICS DR HENDY TANNADY ST

- Slides: 46

THE DATA OF MACROECONOMICS DR. HENDY TANNADY, ST, MM, MBA. DEPARTMENT OF MANAGEMENT FACULTY OF HUMANITIES AND BUSINESS UNIVERSITAS PEMBANGUNAN JAYA N. GREGORY MANKIW. (2013). MACROECONOMICS. NY: WORTH PUBLISHERS.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES In this chapter, you will learn about how we define and measure: Gross Domestic Product (GDP) the Consumer Price Index (CPI) the Unemployment Rate

MEASURING THE VALUE OF ECONOMIC ACTIVITY : GDP

WHY EXPENDITURE = INCOME In every transaction, the buyer’s expenditure becomes the seller’s income. Thus, the sum of all expenditure equals the sum of all income.

WHY EXPENDITURE = INCOME That fact, in turn, follows from an even more fundamental one: Because every transaction has a buyer and a seller, every dollar of expenditure by a buyer must become a dollar of income to a seller.

WHY EXPENDITURE = INCOME When Joe paints Jane’s house for $1, 000, that $1, 000 is income to Joe and expenditure by Jane. The transaction contributes $1, 000 to GDP, regardless of whether we are adding up all income or all expenditure.

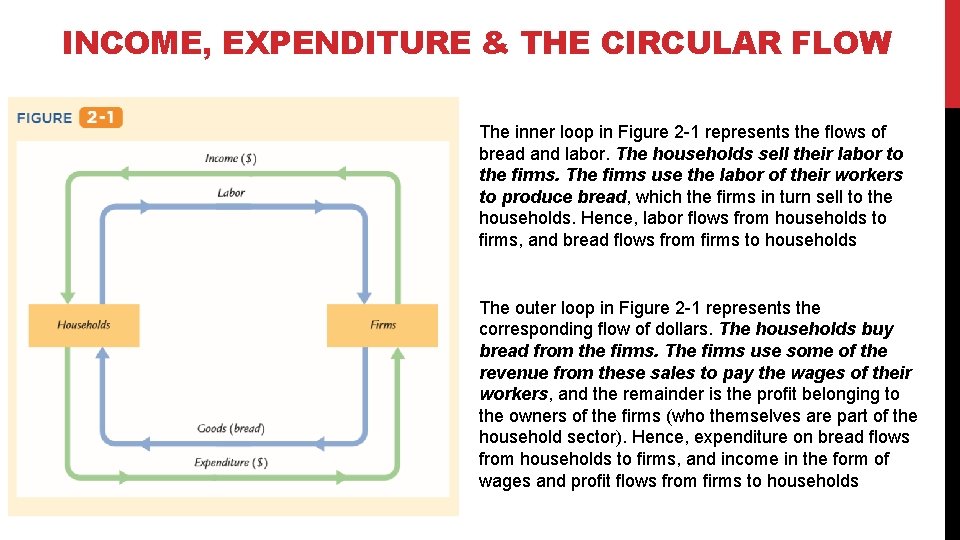

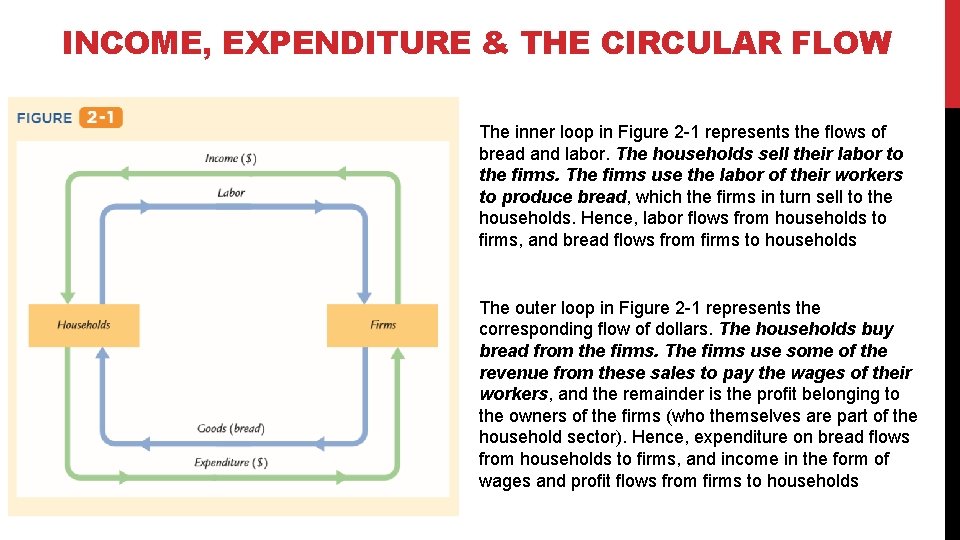

INCOME, EXPENDITURE & THE CIRCULAR FLOW The inner loop in Figure 2 -1 represents the flows of bread and labor. The households sell their labor to the firms. The firms use the labor of their workers to produce bread, which the firms in turn sell to the households. Hence, labor flows from households to firms, and bread flows from firms to households The outer loop in Figure 2 -1 represents the corresponding flow of dollars. The households buy bread from the firms. The firms use some of the revenue from these sales to pay the wages of their workers, and the remainder is the profit belonging to the owners of the firms (who themselves are part of the household sector). Hence, expenditure on bread flows from households to firms, and income in the form of wages and profit flows from firms to households

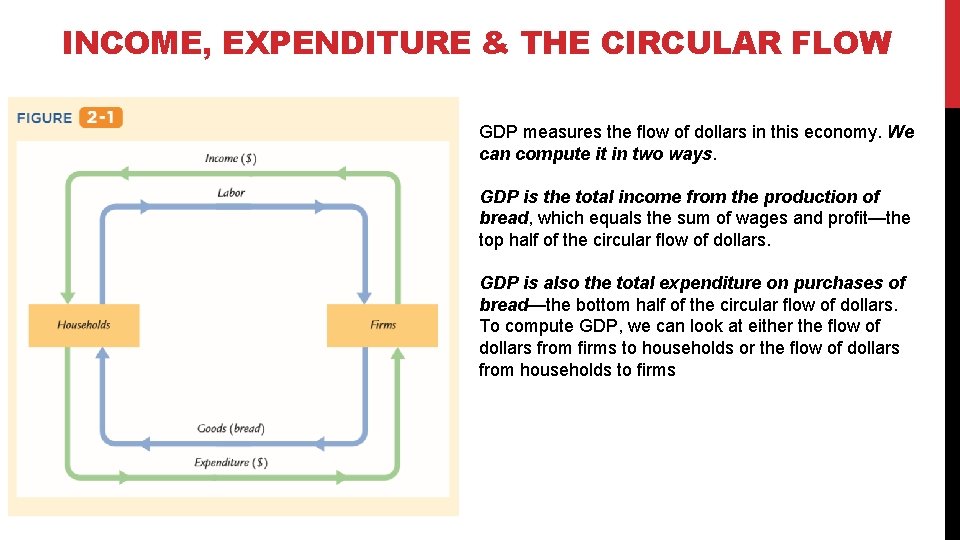

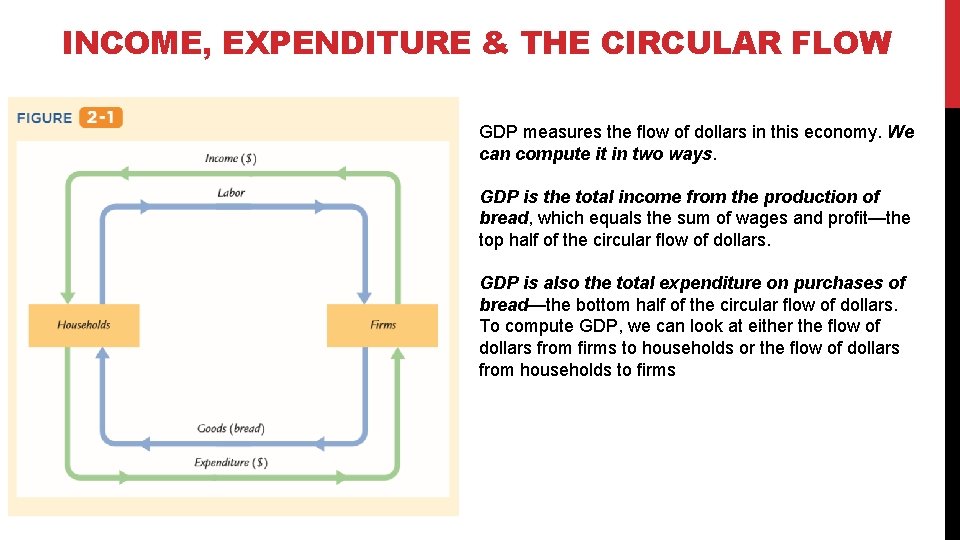

INCOME, EXPENDITURE & THE CIRCULAR FLOW GDP measures the flow of dollars in this economy. We can compute it in two ways. GDP is the total income from the production of bread, which equals the sum of wages and profit—the top half of the circular flow of dollars. GDP is also the total expenditure on purchases of bread—the bottom half of the circular flow of dollars. To compute GDP, we can look at either the flow of dollars from firms to households or the flow of dollars from households to firms

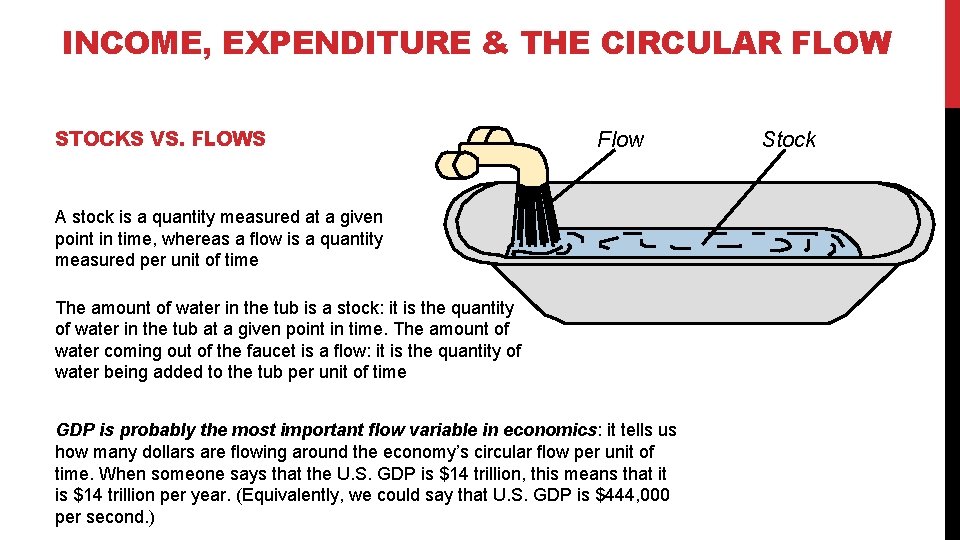

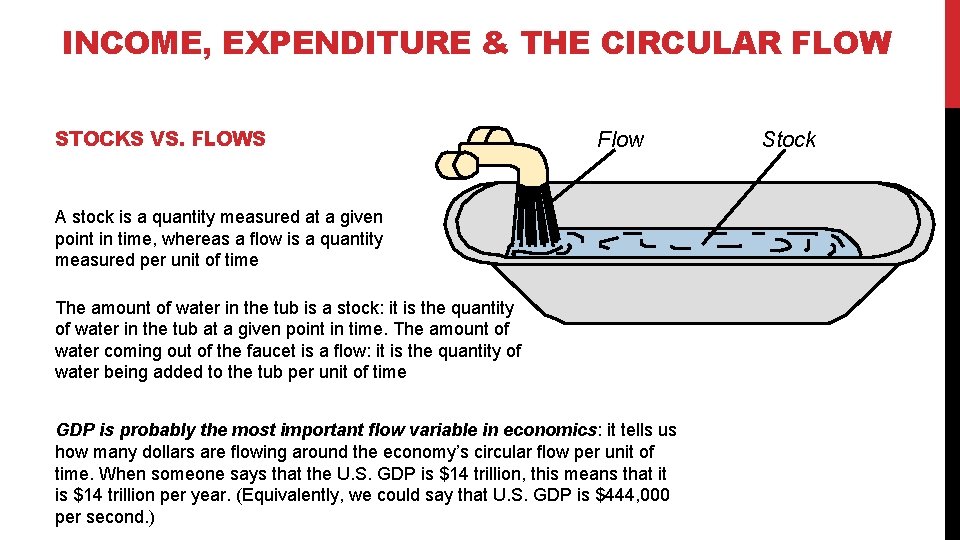

INCOME, EXPENDITURE & THE CIRCULAR FLOW STOCKS VS. FLOWS Flow A stock is a quantity measured at a given point in time, whereas a flow is a quantity measured per unit of time The amount of water in the tub is a stock: it is the quantity of water in the tub at a given point in time. The amount of water coming out of the faucet is a flow: it is the quantity of water being added to the tub per unit of time GDP is probably the most important flow variable in economics: it tells us how many dollars are flowing around the economy’s circular flow per unit of time. When someone says that the U. S. GDP is $14 trillion, this means that it is $14 trillion per year. (Equivalently, we could say that U. S. GDP is $444, 000 per second. ) Stock

RULES FOR COMPUTING GDP ADDING APPLES & ORANGES The U. S. economy produces many different goods and services—hamburgers, haircuts, cars, computers, and so on. GDP combines the value of these goods and services into a single measure. The diversity of products in the economy complicates the calculation of GDP because different products have different values. Suppose, for example, that the economy produces four apples and three oranges. How do we compute GDP? We could simply add apples and oranges and conclude that GDP equals seven pieces of fruit. But this makes sense only if we think apples and oranges have equal value, which is generally not true. Thus, if apples cost $0. 50 each and oranges cost $1. 00 each, GDP would be GDP = (Price of Apples × Quantity of Apples) + (Price of Oranges × Quantity of Oranges) = ($0. 50 × 4) + ($1. 00 × 3) = $5. 00.

RULES FOR COMPUTING GDP USED GOODS When the Topps Company makes a pack of baseball cards and sells it for $2, that $2 is added to the nation’s GDP. But when a collector sells a rare Mickey Mantle card to another collector for $500, that $500 is not part of GDP measures the value of currently produced goods and services. The sale of the Mickey Mantle card reflects the transfer of an asset, not an addition to the economy’s income. Thus, the sale of used goods is not included as part of GDP

RULES FOR COMPUTING GDP THE TREATMENT OF INVENTORIES Imagine that a bakery hires workers to produce more bread, pays their wages, and then fails to sell the additional bread. How does this transaction affect GDP? The answer depends on what happens to the unsold bread. Let’s first suppose that the bread spoils. In this case, the firm has paid more in wages but has not received any additional revenue, so the firm’s profit is reduced by the amount that wages have increased. Total expenditure in the economy hasn’t changed because no one buys the bread. Total income hasn’t changed either—although more is distributed as wages and less as profit. Because the transaction affects neither expenditure nor income, it does not alter GDP. Now suppose, instead, that the bread is put into inventory (perhaps as frozen dough) to be sold later. In this case, the national income accounts treat the transaction differently. The owners of the firm are assumed to have “purchased’’ the bread for the firm’s inventory, and the firm’s profit is not reduced by the additional wages it has paid. Because the higher wages paid to the firm’s workers raise total income, and the greater spending by the firm’s owners on inventory raises total expenditure, the economy’s GDP rises.

RULES FOR COMPUTING GDP INTERMEDIATE GOODS AND VALUE ADDED For example, suppose a cattle rancher sells one-quarter pound of meat to Mc. Donald’s for $1, and then Mc. Donald’s sells you a hamburger for $3. Should GDP include both the meat and the hamburger (a total of $4) or just the hamburger ($3)? The answer is that GDP includes only the value of final goods. Thus, the hamburger is included in GDP but the meat is not: GDP increases by $3, not by $4. One way to compute the value of all final goods and services is to sum the value added at each stage of production. The value added of a fi rm equals the value of the firm’s output less the value of the intermediate goods that the firm purchases. $1 $3

REAL GDP VS NOMINAL GDP Economists use the rules just described to compute GDP, which values the economy’s total output of goods and services. But is GDP a good measure of economic well-being? Consider once again the economy that produces only apples and oranges. In this economy, GDP is the sum of the value of all the apples produced and the value of all the oranges produced. That is, GDP = (Price of Apples × Quantity of Apples) + (Price of Oranges × Quantity of Oranges)

REAL GDP VS NOMINAL GDP Economists call the value of goods and services measured at current prices nominal GDP. Notice that nominal GDP can increase either because prices rise or because quantities rise. It is easy to see that GDP computed this way is not a good gauge of economic well-being. That is, this measure does not accurately reflect how well the economy can satisfy the demands of households, firms, and the government. If all prices doubled without any change in quantities, nominal GDP would double. Yet it would be misleading to say that the economy’s ability to satisfy demands has doubled because the quantity of every good produced remains the same.

REAL GDP VS NOMINAL GDP A better measure of economic well-being would tally the economy’s output of goods and services without being influenced by changes in prices. For this purpose, economists use real GDP, which is the value of goods and services measured using a constant set of prices. That is, real GDP shows what would have happened to expenditure on output if quantities had changed but prices had not.

REAL GDP VS NOMINAL GDP Real GDP in 2011 = (2011 Price of Apples × 2011 Quantity of Apples) + (2011 Price of Oranges × 2011 Quantity of Oranges). Similarly, real GDP in 2012 would be = (2011 Price of Apples × 2012 Quantity of Apples) + (2011 Price of Oranges × 2012 Quantity of Oranges). And real GDP in 2013 would be = (2011 Price of Apples × 2013 Quantity of Apples) + (2011 Price of Oranges × 2013 Quantity of Oranges)

THE GDP DEFLATOR From nominal GDP and real GDP we can compute a third statistic: the GDP deflator. The GDP deflator, also called the implicit price deflator for GDP, is the ratio of nominal GDP to real GDP: The GDP deflator reflects what’s happening to the overall level of prices in the economy.

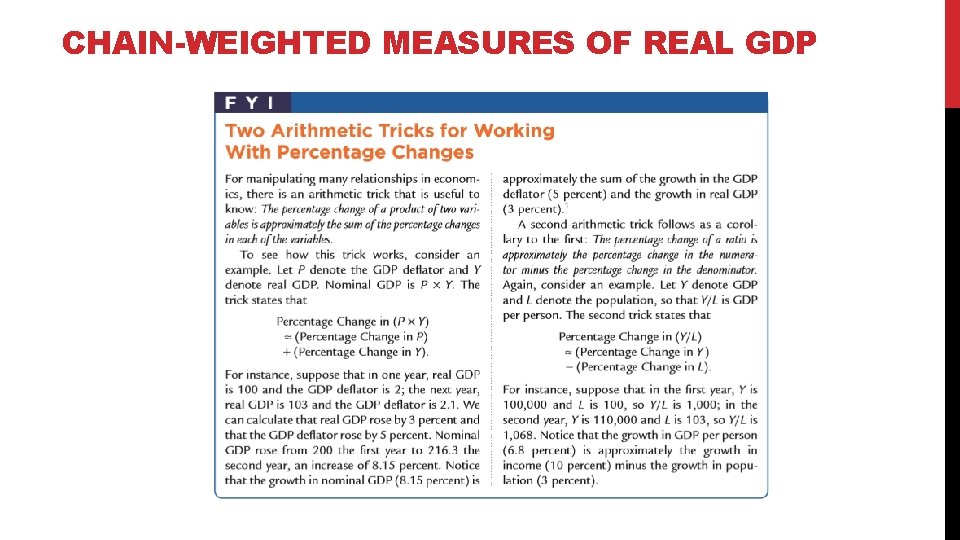

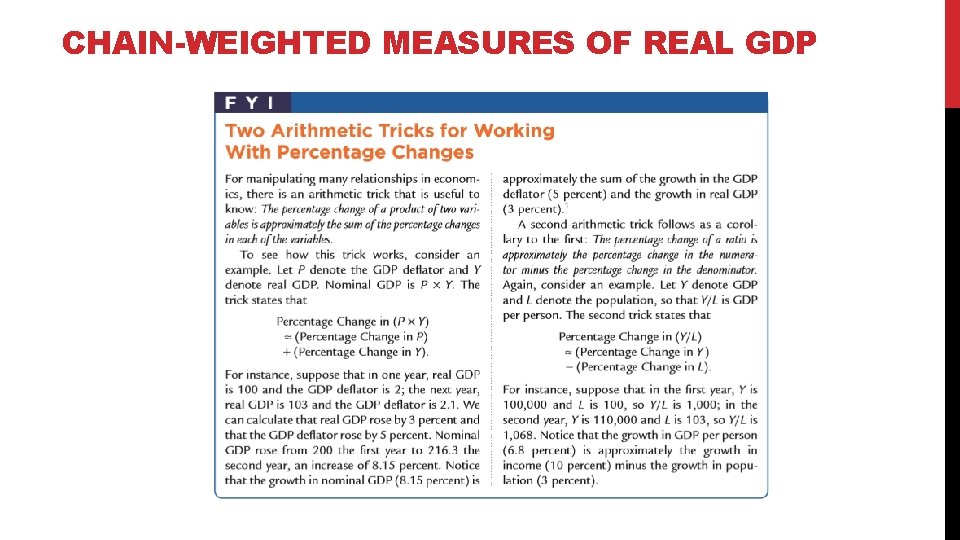

CHAIN-WEIGHTED MEASURES OF REAL GDP

THE COMPONENTS OF EXPENDITURE Consumption (C) Investment (I) Government Purchases (G) Net Exports (NX) GDP (Y) Y = C + I + G + NX

THE COMPONENTS OF EXPENDITURE GDP is the sum of consumption, investment, government purchases, and net exports. Each dollar of GDP falls into one of these categories. This equation is an identity—an equation that must hold because of the way the variables are defined. It is called the national income accounts identity. Y = C + I + G + NX

THE COMPONENTS OF EXPENDITURE Consumption consists of the goods and services bought by households. It is divided into three subcategories: nondurable goods, and services. Nondurable goods are goods that last only a short time, such as food and clothing. Durable goods are goods that last a long time, such as cars and TVs. Services include various intangible items purchased by consumers, such as haircuts and doctor visits. Y= C + I + G + NX

THE COMPONENTS OF EXPENDITURE Investment consists of goods bought for future use. Investment is also divided into three subcategories: business fixed investment, residential fixed investment, and inventory investment. Business fixed investment is the purchase of new plant and equipment by firms. Residential investment is the purchase of new housing by households and landlords. Inventory investment is the increase in firms’ inventories of goods (if inventories are falling, inventory investment is negative). Y=C+ I + G + NX

THE COMPONENTS OF EXPENDITURE Government purchases are the goods and services bought by federal, state, and local governments. This category includes such items as military equipment, highways, and the services provided by government workers. It does not include transfer payments to individuals, such as Social Security and welfare. Because transfer payments reallocate existing income and are not made in exchange for goods and services, they are not part of GDP. Y=C+I+ G + NX

THE COMPONENTS OF EXPENDITURE Net exports, accounts for trade with other countries. Net exports are the value of goods and services sold to other countries (exports) minus the value of goods and services that foreigners sell us (imports). Net exports are positive when the value of our exports is greater than the value of our imports and negative when the value of our imports is greater than the value of our exports. Net exports represent the net expenditure from abroad on our goods and services, which provides income for domestic producers. Y=C+I+G+ NX

OTHERS MEASURES OF INCOME To see how the alternative measures of income relate to one another, we start with GDP and modify it in various ways. To obtain gross national product (GNP), we add to GDP receipts of factor income (wages, profi t, and rent) from the rest of the world and subtract payments of factor income to the rest of the world: GNP = GDP + Factor Payments from Abroad – Factor Payments to Abroad. Whereas GDP measures the total income produced domestically, GNP measures the total income earned by nationals (residents of a nation)

OTHERS MEASURES OF INCOME To obtain net national product (NNP), we subtract from GNP the depreciation of capital—the amount of the economy’s stock of plants, equipment, and residential structures that wears out during the year: NNP = GNP – Depreciation Net national product is approximately equal to another measure called national income.

OTHERS MEASURES OF INCOME The six categories, and the percentage of national income paid in each category, are the following: • • • Compensation of employees (63%) Proprietors’ income (8%) Rental income (3%) Corporate profits (14%) Net interest (4%) Indirect business taxes (8%)

SEASONAL ADJUSTMENT The output of the economy rises during the year, reaching a peak in the fourth quarter (October, November, and December) and then falling in the first quarter (January, February, and March) of the next year. These regular seasonal changes are substantial. From the fourth quarter to the first quarter, real GDP falls on average about 8 percent. It is not surprising that real GDP follows a seasonal cycle. Some of these changes are attributable to changes in our ability to produce: for example, building homes is more difficult during the cold weather of winter than during other seasons. In addition, people have seasonal tastes: they have preferred times for such activities as vacations and Christmas shopping

MEASURING THE COST OF LIVING : THE CONSUMER PRICE INDEX

THE PRICE OF A BASKET OF GOODS The most commonly used measure of the level of prices is the consumer price index (CPI). The Bureau of Labor Statistics, which is part of the U. S. Department of Labor, has the job of computing the CPI. It begins by collecting the prices of thousands of goods and services. Just as GDP turns the quantities of many goods and services into a single number measuring the value of production, the CPI turns the prices of many goods and services into a single index measuring the overall level of prices.

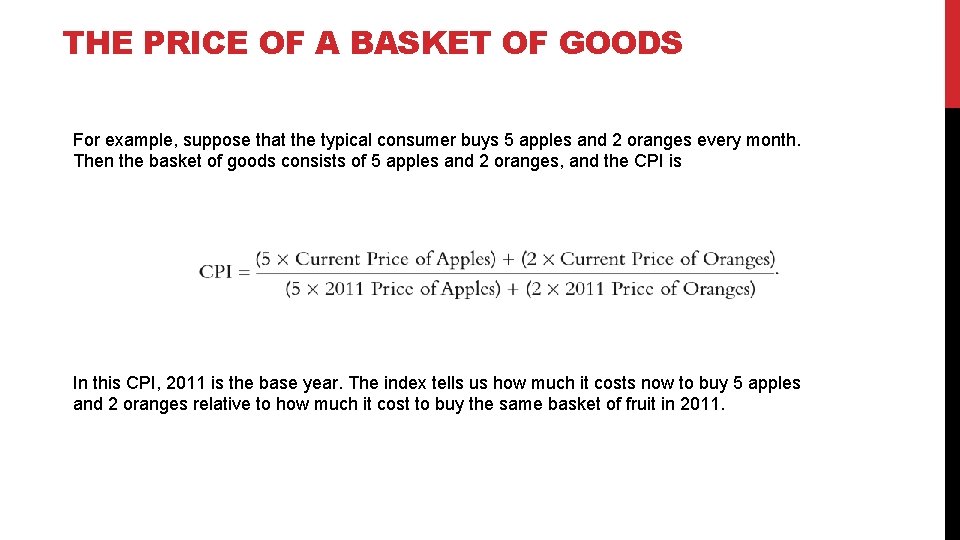

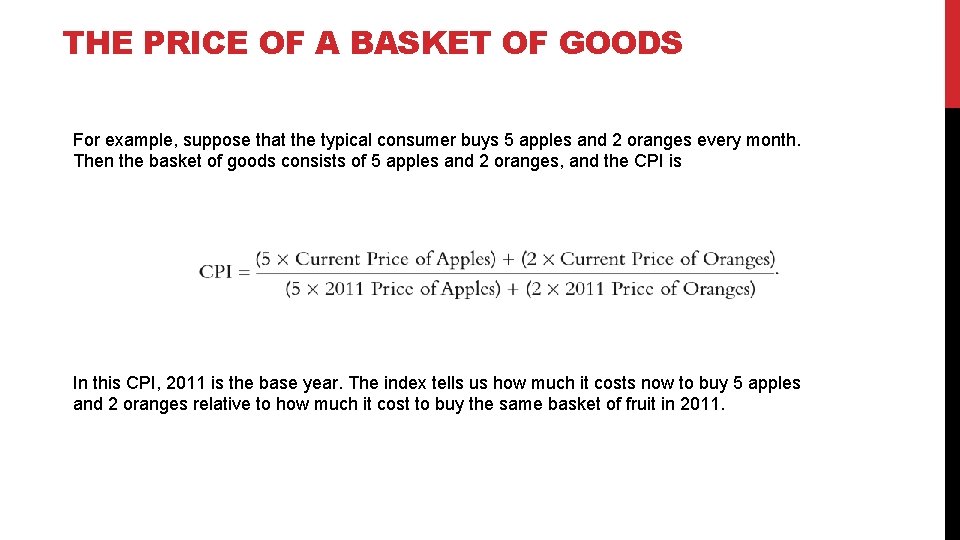

THE PRICE OF A BASKET OF GOODS For example, suppose that the typical consumer buys 5 apples and 2 oranges every month. Then the basket of goods consists of 5 apples and 2 oranges, and the CPI is In this CPI, 2011 is the base year. The index tells us how much it costs now to buy 5 apples and 2 oranges relative to how much it cost to buy the same basket of fruit in 2011.

THE CPI VERSUS GDP DEFLATOR The GDP deflator and the CPI give somewhat different information about what’s happening to the overall level of prices in the economy. There are three key differences between the two measures. 1. The first difference is that the GDP deflator measures the prices of all goods and services produced whereas the CPI measures the prices of only the goods and services bought by consumers. Thus, an increase in the price of goods bought only by firms or the government will show up in the GDP deflator but not in the CPI.

THE CPI VERSUS GDP DEFLATOR The GDP deflator and the CPI give somewhat different information about what’s happening to the overall level of prices in the economy. There are three key differences between the two measures. 2. The second difference is that the GDP deflator includes only those goods produced domestically. Imported goods are not part of GDP and do not show up in the GDP deflator. Hence, an increase in the price of Toyotas made in Japan and sold in this country affects the CPI, because the Toyotas are bought by consumers, but it does not affect the GDP deflator

THE CPI VERSUS GDP DEFLATOR The GDP deflator and the CPI give somewhat different information about what’s happening to the overall level of prices in the economy. There are three key differences between the two measures. 3. The third and most subtle difference results from the way the two measures aggregate the many prices in the economy. The CPI assigns fixed weights to the prices of different goods, whereas the GDP deflator assigns changing weights. In other words, the CPI is computed using a fi xed basket of goods, whereas the GDP defl ator allows the basket of goods to change over time as the composition of GDP changes. The following example shows how these approaches differ. Suppose that major frosts destroy the nation’s orange crop. The quantity of oranges produced falls to zero, and the price of the few oranges that remain on grocers’ shelves is driven sky-high. Because oranges are no longer part of GDP, the increase in the price of oranges does not show up in the GDP defl ator. But because the CPI is computed with a fixed basket of goods that includes oranges, the increase in the price of oranges causes a substantial rise in the CPI.

DOES THE CPI OVERSTATE INFLATION ? The consumer price index is a closely watched measure of inflation. Policymakers in the Federal Reserve monitor the CPI when determining monetary policy. In addition, many laws and private contracts have cost-of-living allowances, called COLAs, which use the CPI to adjust for changes in the price level. For instance, Social Security benefits are adjusted automatically every year so that infl ation will not erode the living standard of the elderly.

MEASURING JOBLESSNESS : THE UNEMPLOYMENT RATE

THE HOUSEHOLD SURVEY The unemployment rate comes from a survey of about 60, 000 households called the Current Population Survey. Based on the responses to survey questions, each adult (age 16 and older) in each household is placed into one of three categories: ■ Employed. This category includes those who at the time of the survey worked as paid employees, worked in their own business, or worked as unpaid workers in a family member’s business. It also includes those who were not working but who had jobs from which they were temporarily absent because of, for example, vacation, illness, or bad weather. ■ Unemployed. This category includes those who were not employed, were available for work, and had tried to find employment. It also includes those waiting to be recalled to a job from which they had been laid off. ■ Not in the labor force. This category includes those who fit neither of the first two categories, such as a full-time student, homemaker, or retiree.

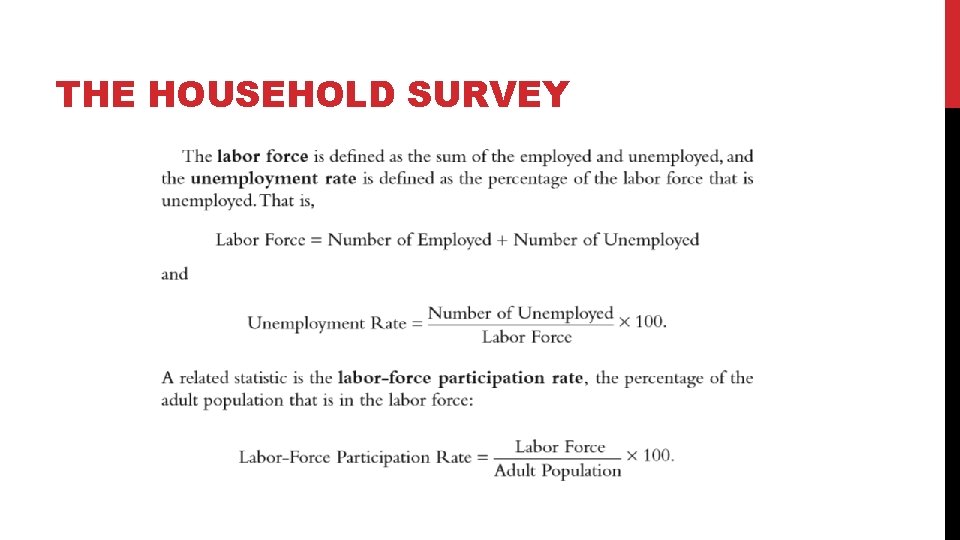

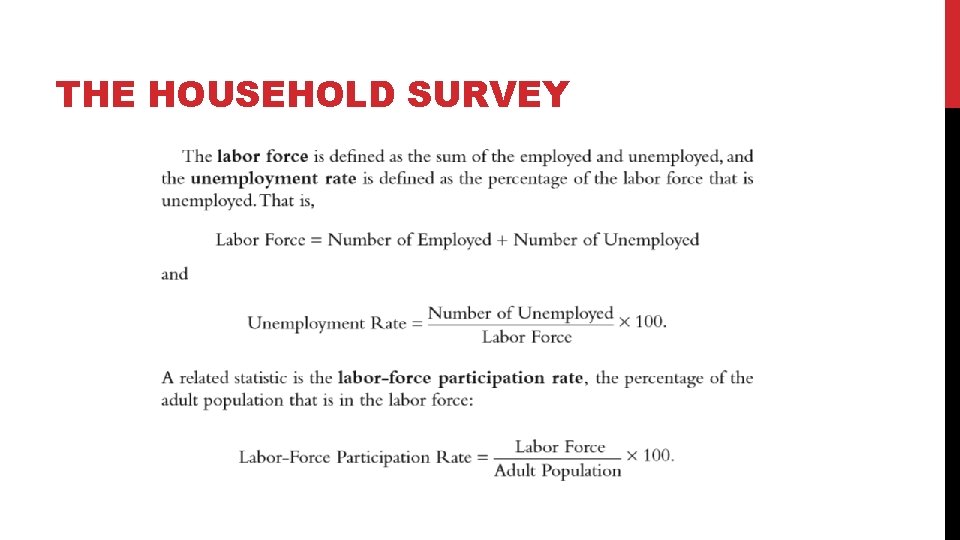

THE HOUSEHOLD SURVEY

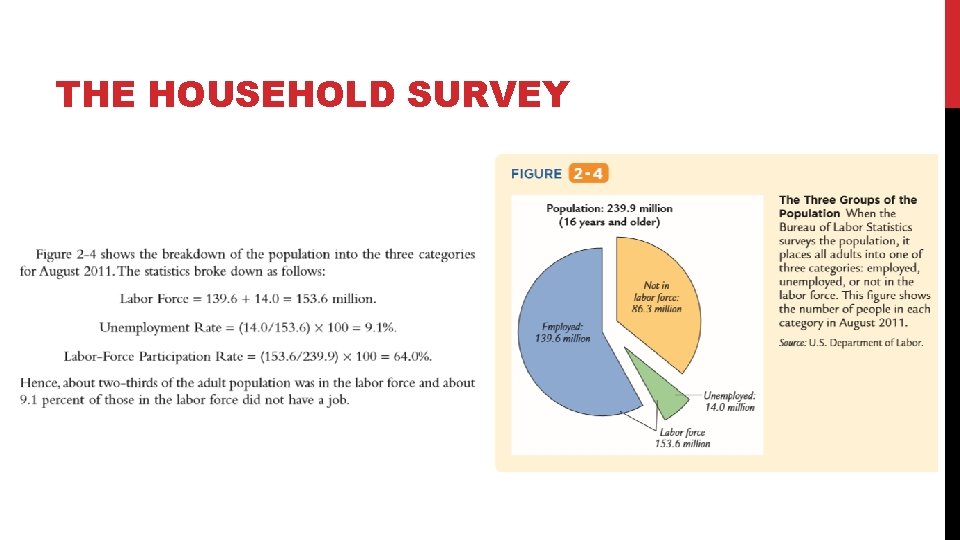

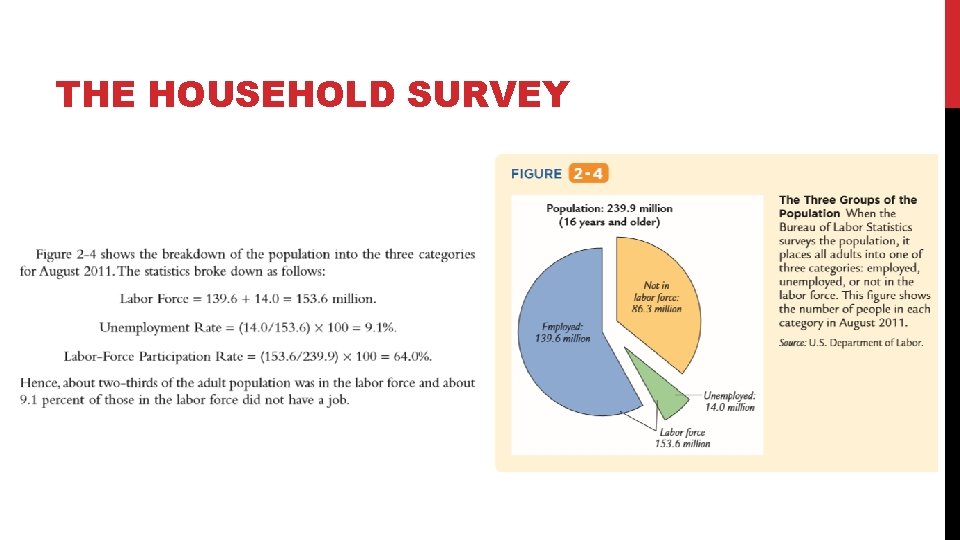

THE HOUSEHOLD SURVEY

CONCLUSION: FORM ECONOMIC STATISTICS TO ECONOMIC MODELS

The three statistics discussed in this chapter—gross domestic product, the consumer price index, and the unemployment rate—quantify the performance of the economy. Public and private decisionmakers use these statistics to monitor changes in the economy and to formulate appropriate policies. Economists use these statistics to develop and test theories about how the economy works.

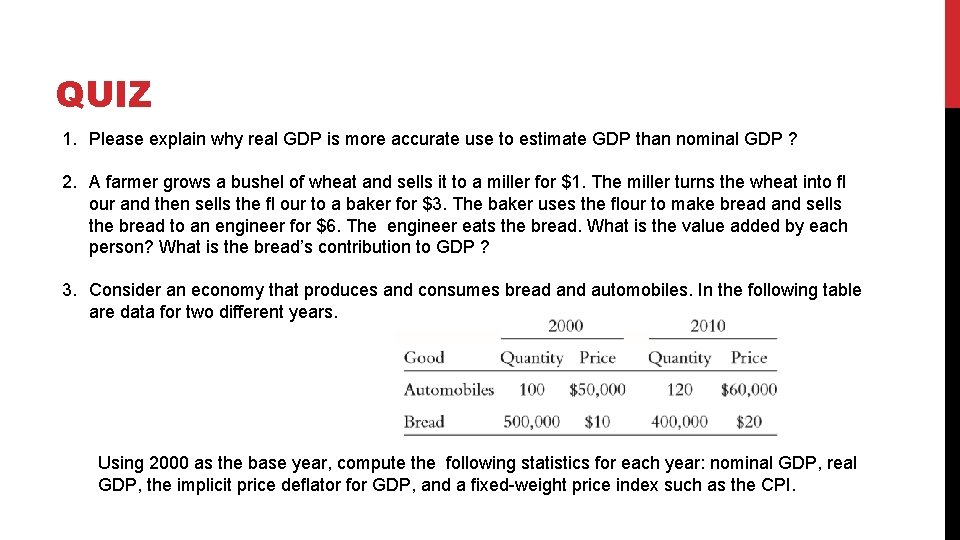

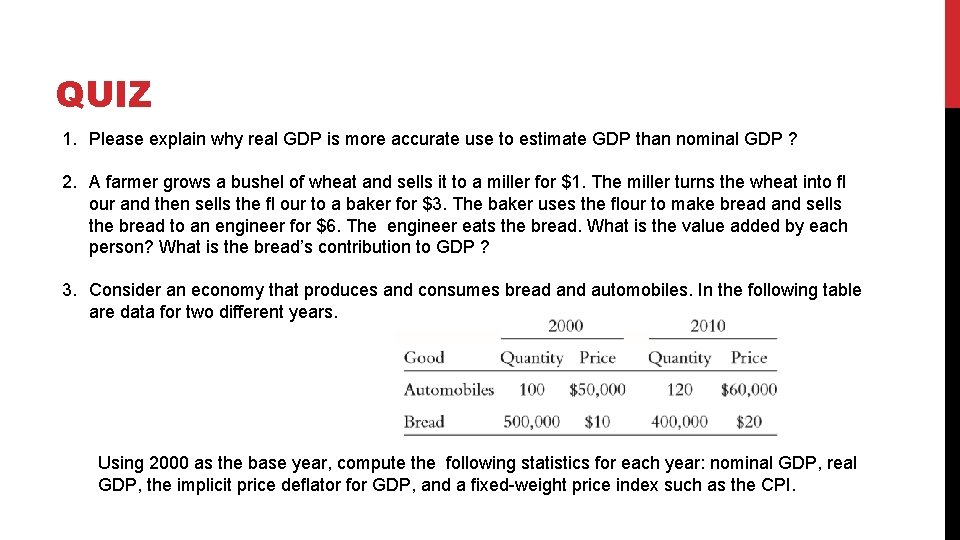

QUIZ 1. Please explain why real GDP is more accurate use to estimate GDP than nominal GDP ? 2. A farmer grows a bushel of wheat and sells it to a miller for $1. The miller turns the wheat into fl our and then sells the fl our to a baker for $3. The baker uses the flour to make bread and sells the bread to an engineer for $6. The engineer eats the bread. What is the value added by each person? What is the bread’s contribution to GDP ? 3. Consider an economy that produces and consumes bread and automobiles. In the following table are data for two different years. Using 2000 as the base year, compute the following statistics for each year: nominal GDP, real GDP, the implicit price deflator for GDP, and a fixed-weight price index such as the CPI.

QUIZ 4. Abby consumes only apples. In year 1, red apples cost $1 each, green apples cost $2 each, and Abby buys 10 red apples. In year 2, red apples cost $2, green apples cost $1, and Abby buys 10 green apples. a. Compute a consumer price index for apples for each year. Assume that year 1 is the base year in which the consumer basket is fixed. How does your index change from year 1 to year 2? b. Compute Abby’s nominal spending on apples in each year. How does it change from year 1 to year 2? c. Using year 1 as the base year, compute Abby’s real spending on apples in each year. How does it change from year 1 to year 2? d. Defining the implicit price deflator as nominal spending divided by real spending, compute the deflator for each year. How does the deflator change from year 1 to year 2?

QUIZ 5. Can you explain why measurement of GDP not only use income as an approach but expenditure is able to use as GDP measurement approach. 6. Can you explain the relationship between household and firm in circular flow of economic. 7. Can you explain the concept of “intermediate goods” and “value added” in formulating GDP.

THANK YOU