The book a LRBS timeline All books shown

The book: a LRBS timeline All books shown here are held in Senate House Library, University of London. Due to lack of access during the 2020 Coronavirus lockdown, not all images are of the Senate House Library copy.

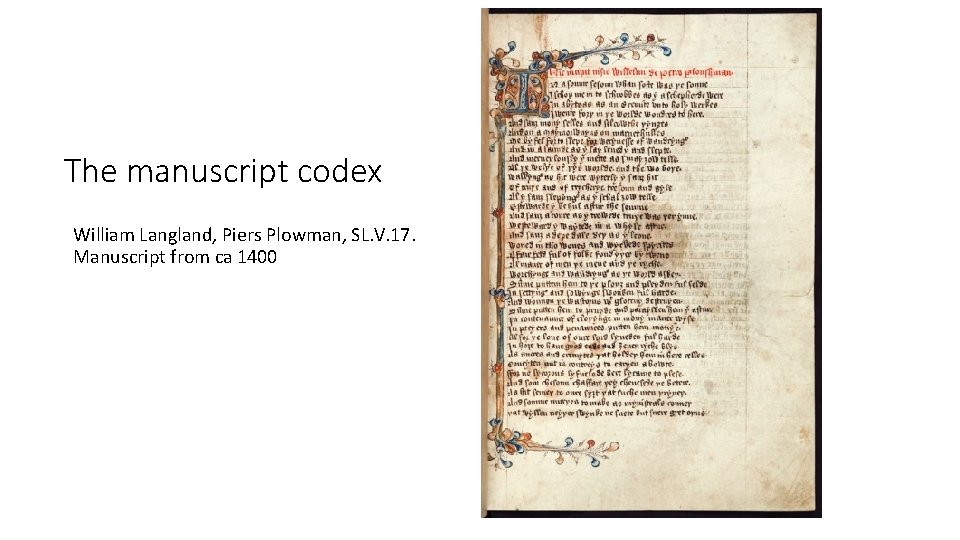

The manuscript codex William Langland, Piers Plowman, SL. V. 17. Manuscript from ca 1400

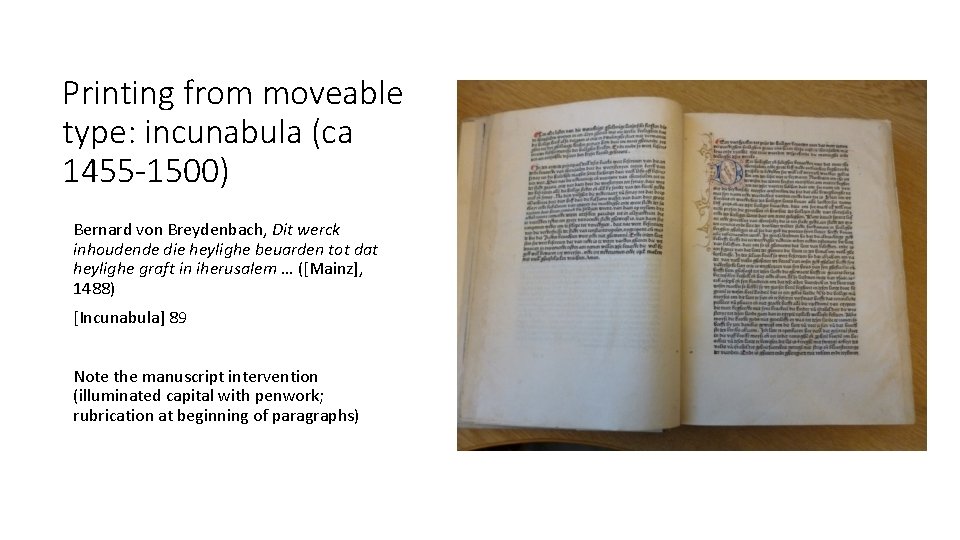

Printing from moveable type: incunabula (ca 1455 -1500) Bernard von Breydenbach, Dit werck inhoudende die heylighe beuarden tot dat heylighe graft in iherusalem … ([Mainz], 1488) [Incunabula] 89 Note the manuscript intervention (illuminated capital with penwork; rubrication at beginning of paragraphs)

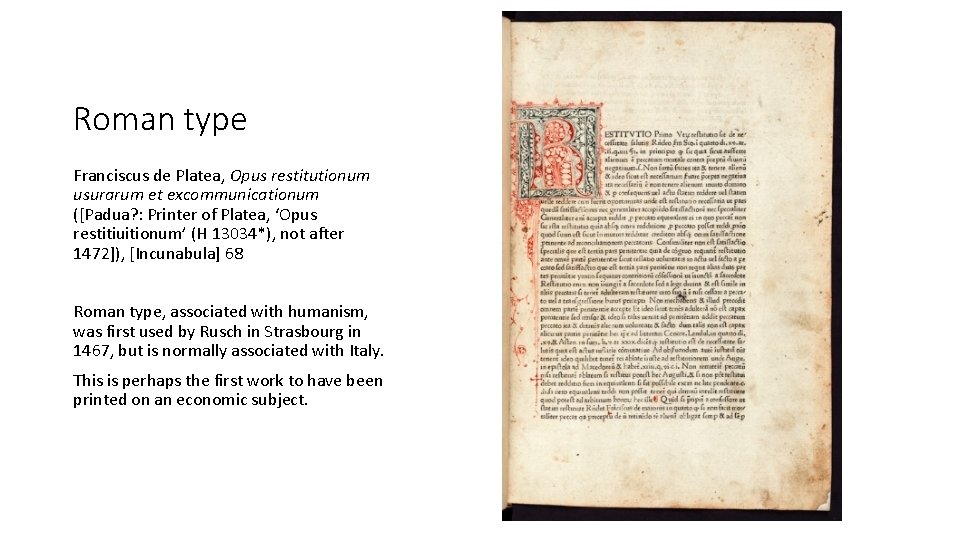

Roman type Franciscus de Platea, Opus restitutionum usurarum et excommunicationum ([Padua? : Printer of Platea, ‘Opus restitiuitionum’ (H 13034*), not after 1472]), [Incunabula] 68 Roman type, associated with humanism, was first used by Rusch in Strasbourg in 1467, but is normally associated with Italy. This is perhaps the first work to have been printed on an economic subject.

![William Caxton: England’s first printer • Jacobus de Cessolis, The Game of Chesse ([Westminster]: William Caxton: England’s first printer • Jacobus de Cessolis, The Game of Chesse ([Westminster]:](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/241579d55ab0f9d5e7ad0ea9663b0c0b/image-5.jpg)

William Caxton: England’s first printer • Jacobus de Cessolis, The Game of Chesse ([Westminster]: William Caxton, [1483]), [Incunabula] 132 • William Caxton introduced printing to England in 1476. He translated this work himself. England was unusual for the high proportion of incunabula published in the vernacular (63%). • The illustration is a woodcut.

![Printing music Franchinus Gaffurius, Theorica musice (Milan: P. Mantegazzi, 1480), [Incunabula] 95 Printing music Printing music Franchinus Gaffurius, Theorica musice (Milan: P. Mantegazzi, 1480), [Incunabula] 95 Printing music](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/241579d55ab0f9d5e7ad0ea9663b0c0b/image-6.jpg)

Printing music Franchinus Gaffurius, Theorica musice (Milan: P. Mantegazzi, 1480), [Incunabula] 95 Printing music on stave lines was a challenge, and the earliest printers left spaces for notes to be added by hand. The first true example of music type is recorded c. 1473. See the Littleton Collection at Senate House Library for examples of early music printing.

![Lavish illustration Hartmann Schedel, The Nuremberg Chronicle ([Nuremberg]: Anton Koberger, 1493), [Incunabula] 121 Illustration Lavish illustration Hartmann Schedel, The Nuremberg Chronicle ([Nuremberg]: Anton Koberger, 1493), [Incunabula] 121 Illustration](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/241579d55ab0f9d5e7ad0ea9663b0c0b/image-7.jpg)

Lavish illustration Hartmann Schedel, The Nuremberg Chronicle ([Nuremberg]: Anton Koberger, 1493), [Incunabula] 121 Illustration appeared in printed books from 1461 onwards. The Nuremberg Chronicle stands out for the large number of its woodcuts (1, 809, including repeats) and for illustration by major artists, Michael Wohlgemut and Wilhelm Pleydenwurff.

![15 th-century binding Heinrich Institoris and Jacob Sprenger, Malleus maleficarum ([Nuremberg]: Anton Koberger, 1494), 15 th-century binding Heinrich Institoris and Jacob Sprenger, Malleus maleficarum ([Nuremberg]: Anton Koberger, 1494),](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/241579d55ab0f9d5e7ad0ea9663b0c0b/image-8.jpg)

15 th-century binding Heinrich Institoris and Jacob Sprenger, Malleus maleficarum ([Nuremberg]: Anton Koberger, 1494), [Incunabula] 40 Until the mechanisation of bookbinding in the 1820 s, books were normally issued unbound in sheets or in cheap temporary bindings for quick sale. Books were often bound and rebound in accordance with fashion. This is an example of a book with its first, contemporary on nearcontemporary binding.

![Post-incunables Heures a l’usaige de Rome (Paris: Germain Hardouyn, [ca 1516]), G 10 [Catholic Post-incunables Heures a l’usaige de Rome (Paris: Germain Hardouyn, [ca 1516]), G 10 [Catholic](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/241579d55ab0f9d5e7ad0ea9663b0c0b/image-9.jpg)

Post-incunables Heures a l’usaige de Rome (Paris: Germain Hardouyn, [ca 1516]), G 10 [Catholic Church] SR Books printed 1501 -ca 1520 are known as ‘post-incunabula’. They were printed by the same people using the same techniques as incunabula, and show the artificiality, if convenience, of the cut-off date of 1500 for the earliest printing. This particular book is printed on vellum and resembles a manuscript.

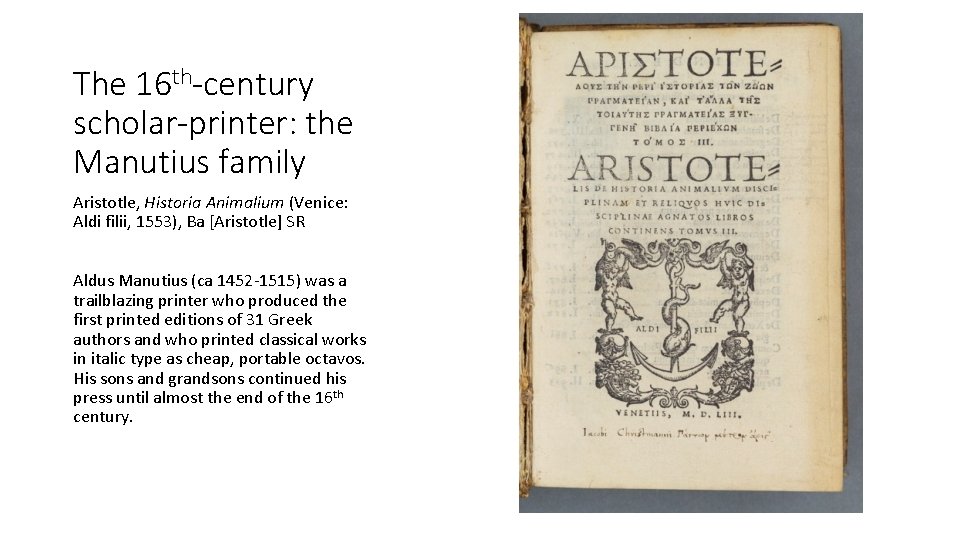

The 16 th-century scholar-printer: the Manutius family Aristotle, Historia Animalium (Venice: Aldi filii, 1553), Ba [Aristotle] SR Aldus Manutius (ca 1452 -1515) was a trailblazing printer who produced the first printed editions of 31 Greek authors and who printed classical works in italic type as cheap, portable octavos. His sons and grandsons continued his press until almost the end of the 16 th century.

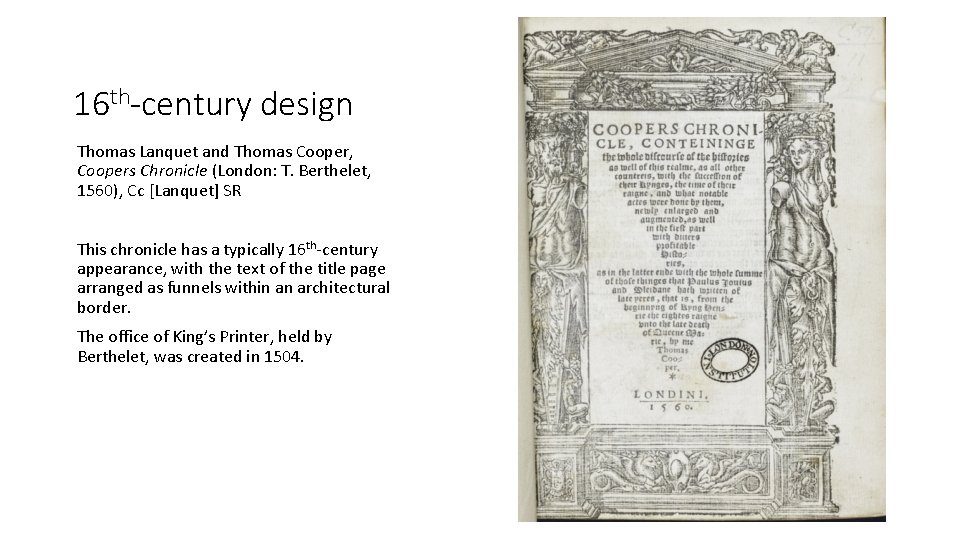

16 th-century design Thomas Lanquet and Thomas Cooper, Coopers Chronicle (London: T. Berthelet, 1560), Cc [Lanquet] SR This chronicle has a typically 16 th-century appearance, with the text of the title page arranged as funnels within an architectural border. The office of King’s Printer, held by Berthelet, was created in 1504.

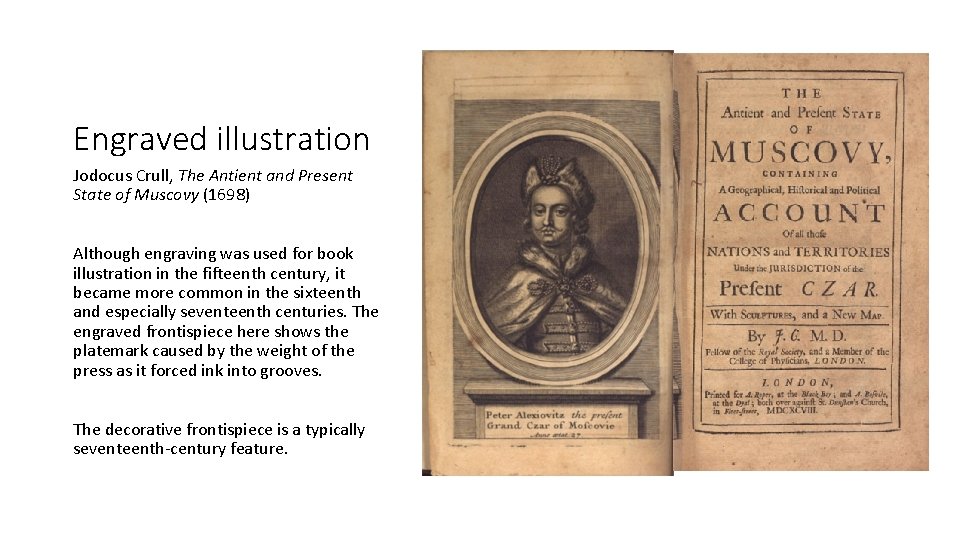

Engraved illustration Jodocus Crull, The Antient and Present State of Muscovy (1698) Although engraving was used for book illustration in the fifteenth century, it became more common in the sixteenth and especially seventeenth centuries. The engraved frontispiece here shows the platemark caused by the weight of the press as it forced ink into grooves. The decorative frontispiece is a typically seventeenth-century feature.

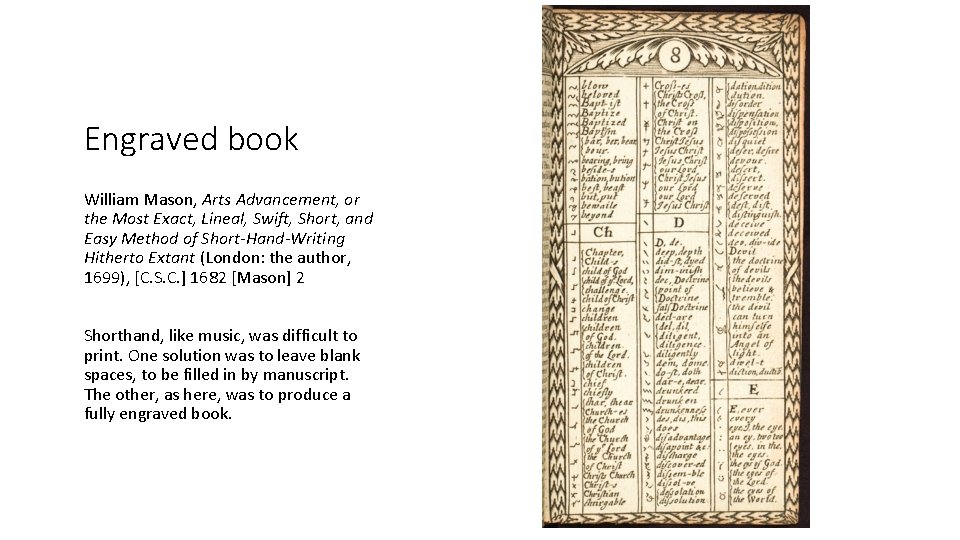

Engraved book William Mason, Arts Advancement, or the Most Exact, Lineal, Swift, Short, and Easy Method of Short-Hand-Writing Hitherto Extant (London: the author, 1699), [C. S. C. ] 1682 [Mason] 2 Shorthand, like music, was difficult to print. One solution was to leave blank spaces, to be filled in by manuscript. The other, as here, was to produce a fully engraved book.

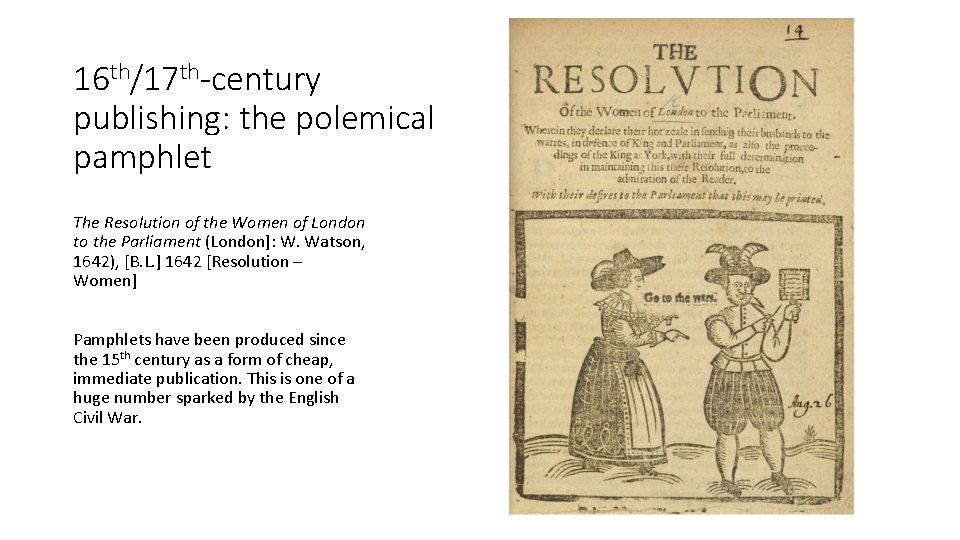

16 th/17 th-century publishing: the polemical pamphlet The Resolution of the Women of London to the Parliament (London]: W. Watson, 1642), [B. L. ] 1642 [Resolution – Women] Pamphlets have been produced since the 15 th century as a form of cheap, immediate publication. This is one of a huge number sparked by the English Civil War.

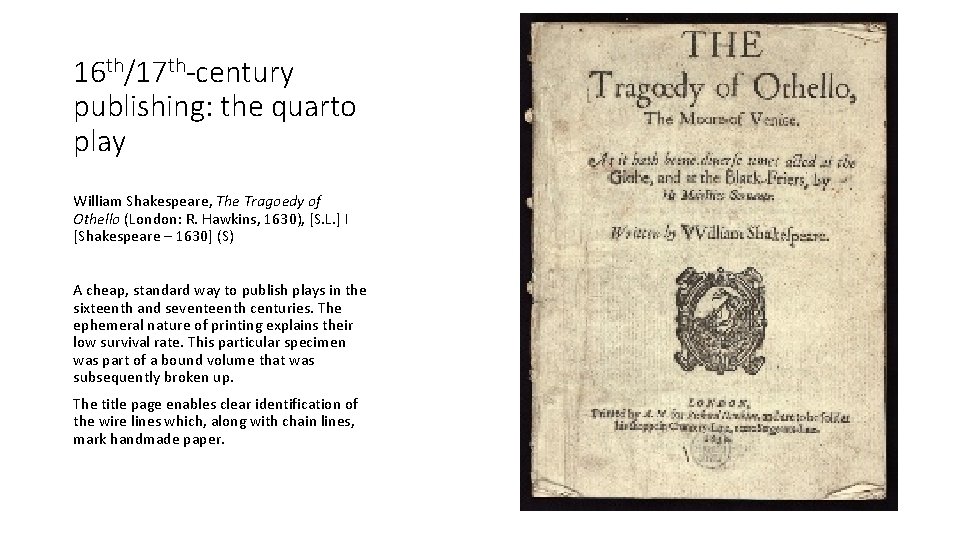

16 th/17 th-century publishing: the quarto play William Shakespeare, The Tragoedy of Othello (London: R. Hawkins, 1630), [S. L. ] I [Shakespeare – 1630] (S) A cheap, standard way to publish plays in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The ephemeral nature of printing explains their low survival rate. This particular specimen was part of a bound volume that was subsequently broken up. The title page enables clear identification of the wire lines which, along with chain lines, mark handmade paper.

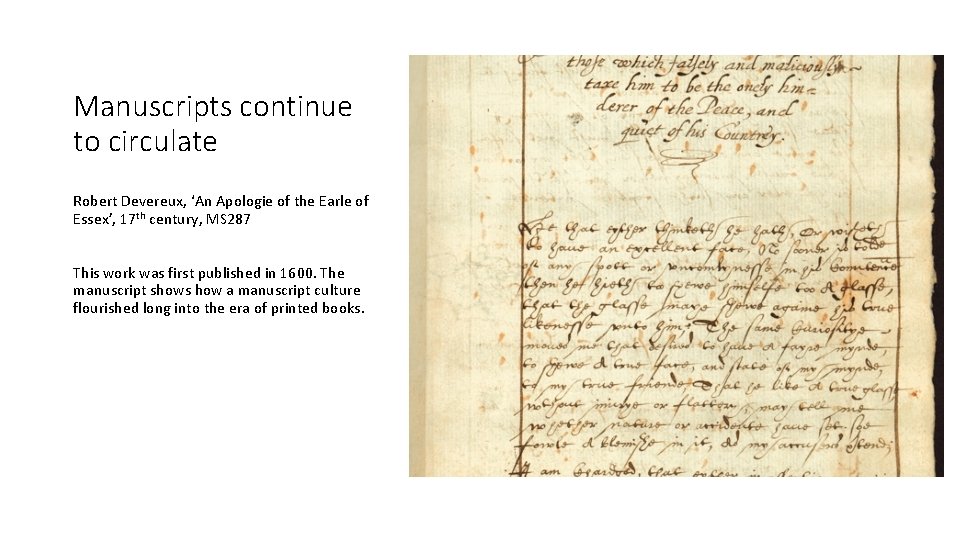

Manuscripts continue to circulate Robert Devereux, ‘An Apologie of the Earle of Essex’, 17 th century, MS 287 This work was first published in 1600. The manuscript shows how a manuscript culture flourished long into the era of printed books.

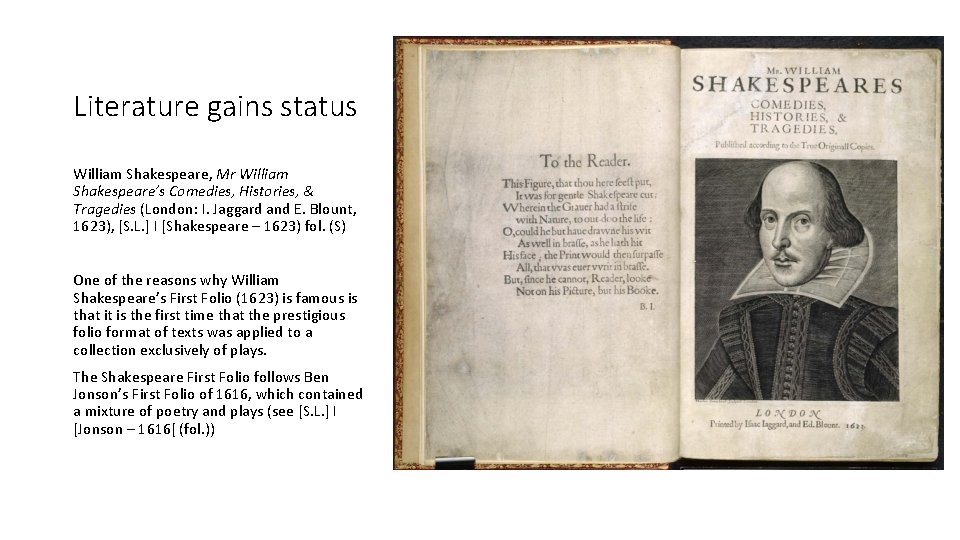

Literature gains status William Shakespeare, Mr William Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies (London: I. Jaggard and E. Blount, 1623), [S. L. ] I [Shakespeare – 1623) fol. (S) One of the reasons why William Shakespeare’s First Folio (1623) is famous is that it is the first time that the prestigious folio format of texts was applied to a collection exclusively of plays. The Shakespeare First Folio follows Ben Jonson’s First Folio of 1616, which contained a mixture of poetry and plays (see [S. L. ] I [Jonson – 1616[ (fol. ))

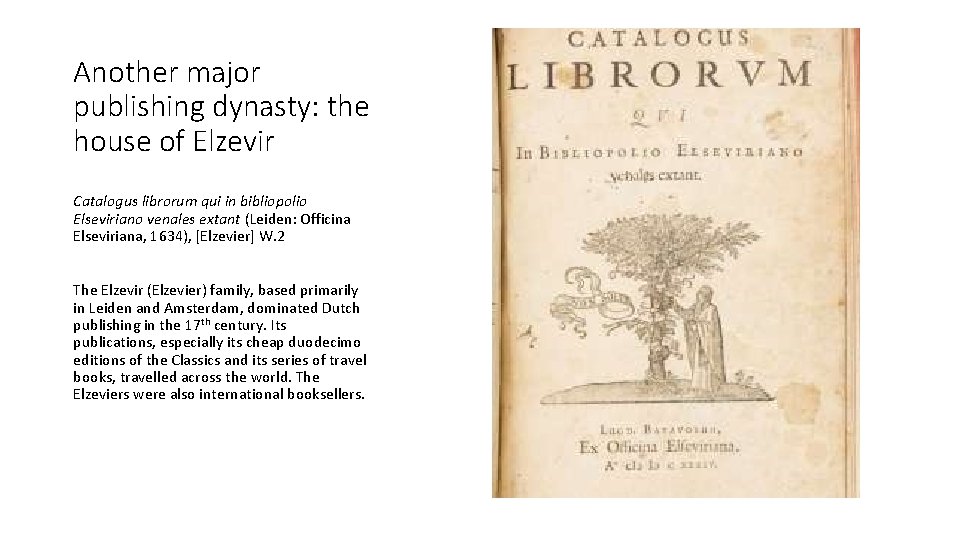

Another major publishing dynasty: the house of Elzevir Catalogus librorum qui in bibliopolio Elseviriano venales extant (Leiden: Officina Elseviriana, 1634), [Elzevier] W. 2 The Elzevir (Elzevier) family, based primarily in Leiden and Amsterdam, dominated Dutch publishing in the 17 th century. Its publications, especially its cheap duodecimo editions of the Classics and its series of travel books, travelled across the world. The Elzeviers were also international booksellers.

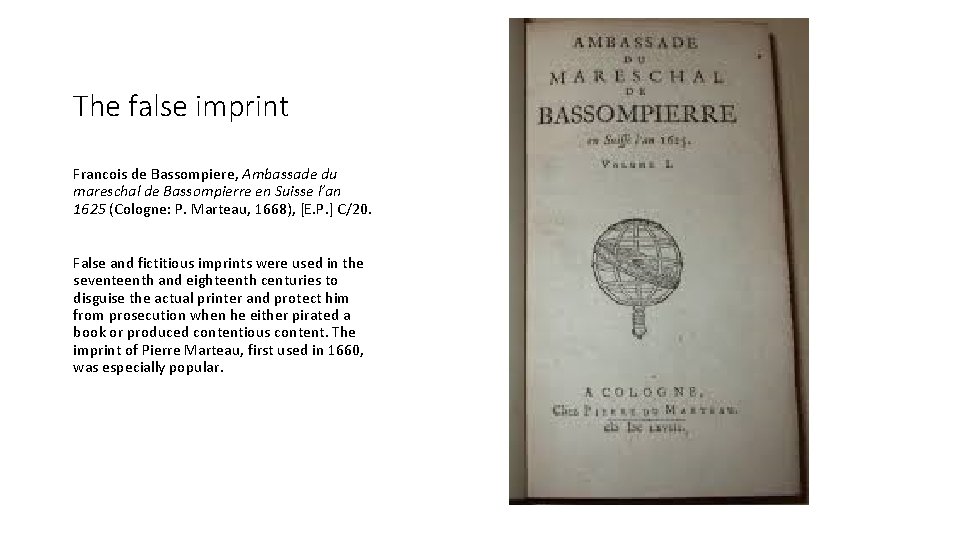

The false imprint Francois de Bassompiere, Ambassade du mareschal de Bassompierre en Suisse l’an 1625 (Cologne: P. Marteau, 1668), [E. P. ] C/20. False and fictitious imprints were used in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries to disguise the actual printer and protect him from prosecution when he either pirated a book or produced contentious content. The imprint of Pierre Marteau, first used in 1660, was especially popular.

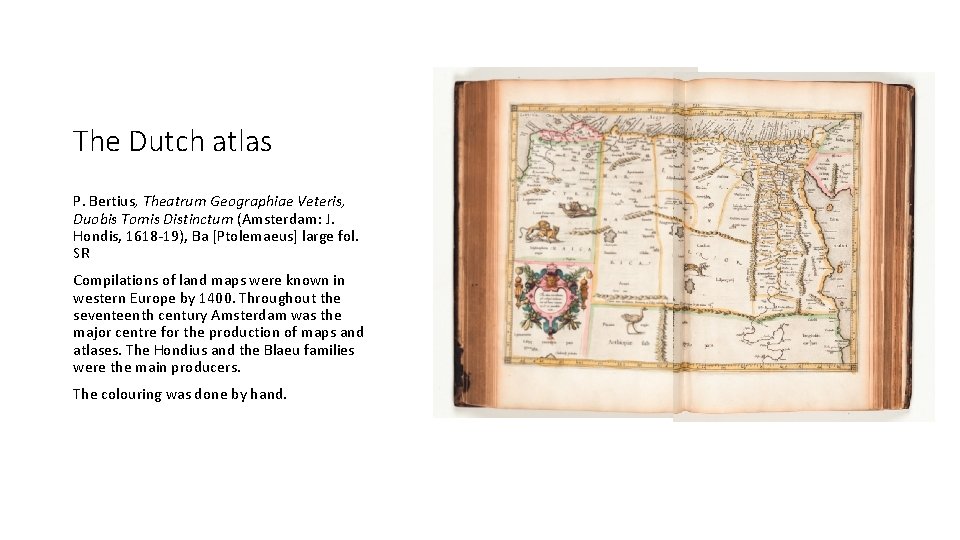

The Dutch atlas P. Bertius, Theatrum Geographiae Veteris, Duobis Tomis Distinctum (Amsterdam: J. Hondis, 1618 -19), Ba [Ptolemaeus] large fol. SR Compilations of land maps were known in western Europe by 1400. Throughout the seventeenth century Amsterdam was the major centre for the production of maps and atlases. The Hondius and the Blaeu families were the main producers. The colouring was done by hand.

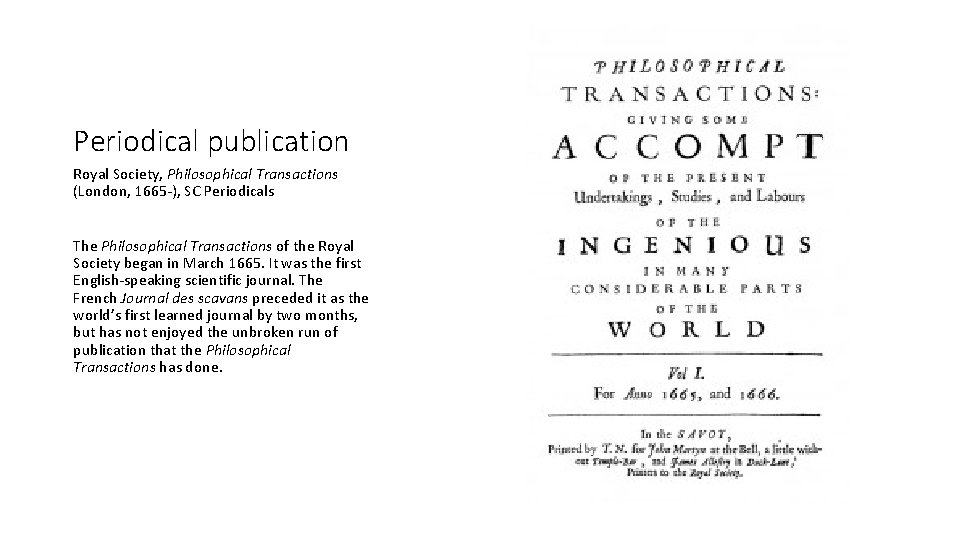

Periodical publication Royal Society, Philosophical Transactions (London, 1665 -), SC Periodicals The Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society began in March 1665. It was the first English-speaking scientific journal. The French Journal des scavans preceded it as the world’s first learned journal by two months, but has not enjoyed the unbroken run of publication that the Philosophical Transactions has done.

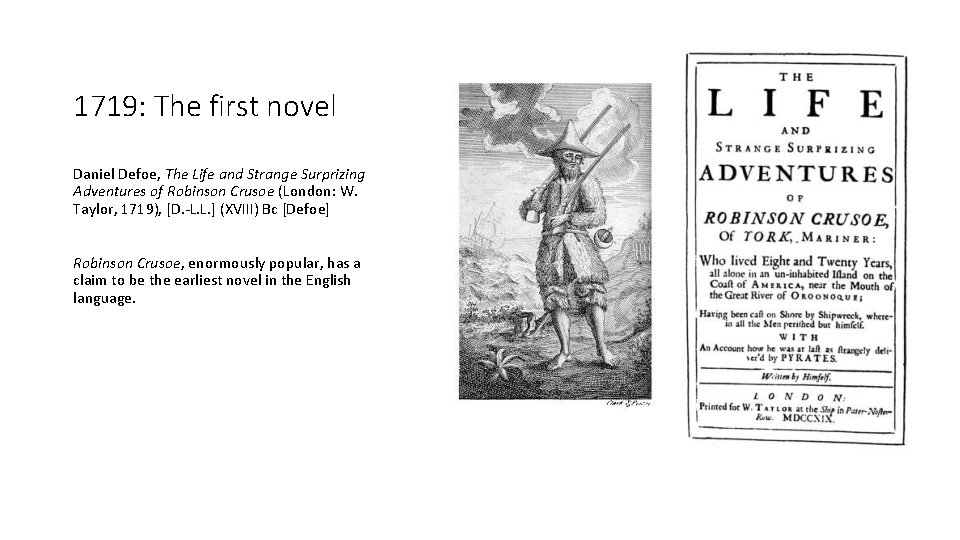

1719: The first novel Daniel Defoe, The Life and Strange Surprizing Adventures of Robinson Crusoe (London: W. Taylor, 1719), [D. -L. L. ] (XVIII) Bc [Defoe] Robinson Crusoe, enormously popular, has a claim to be the earliest novel in the English language.

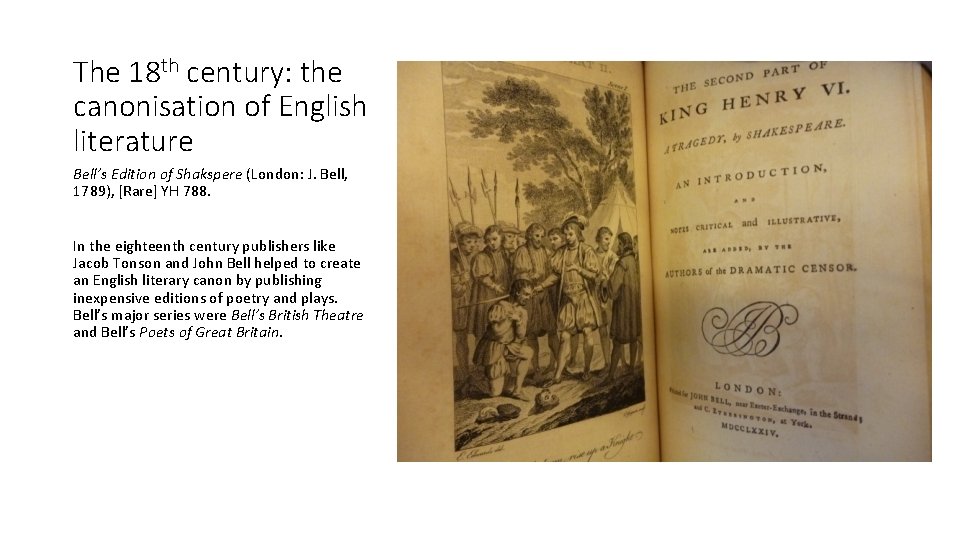

The 18 th century: the canonisation of English literature Bell’s Edition of Shakspere (London: J. Bell, 1789), [Rare] YH 788. In the eighteenth century publishers like Jacob Tonson and John Bell helped to create an English literary canon by publishing inexpensive editions of poetry and plays. Bell’s major series were Bell’s British Theatre and Bell’s Poets of Great Britain.

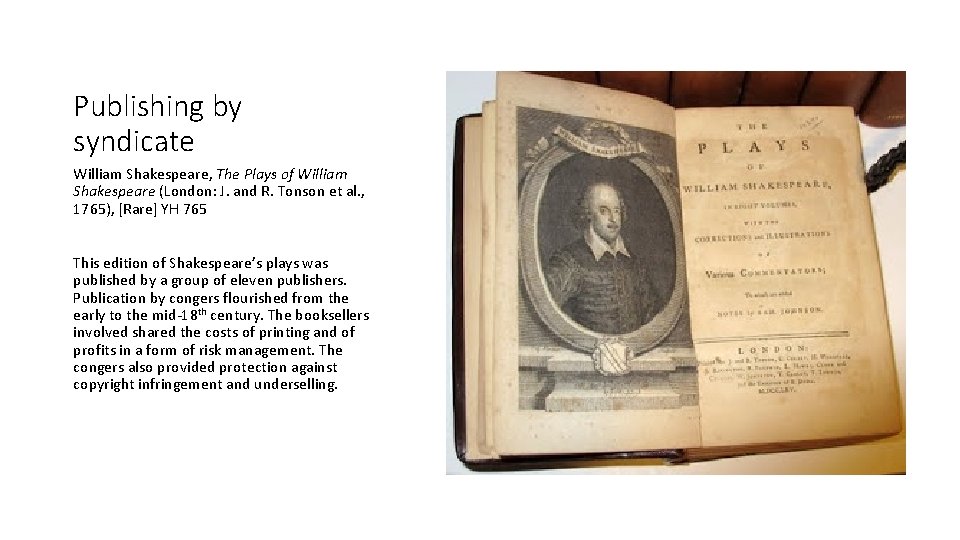

Publishing by syndicate William Shakespeare, The Plays of William Shakespeare (London: J. and R. Tonson et al. , 1765), [Rare] YH 765 This edition of Shakespeare’s plays was published by a group of eleven publishers. Publication by congers flourished from the early to the mid-18 th century. The booksellers involved shared the costs of printing and of profits in a form of risk management. The congers also provided protection against copyright infringement and underselling.

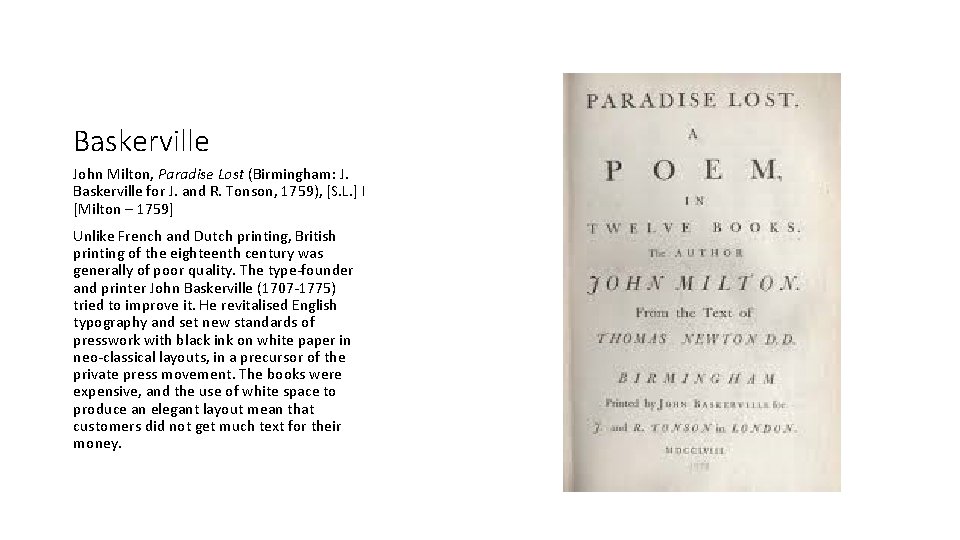

Baskerville John Milton, Paradise Lost (Birmingham: J. Baskerville for J. and R. Tonson, 1759), [S. L. ] I [Milton – 1759] Unlike French and Dutch printing, British printing of the eighteenth century was generally of poor quality. The type-founder and printer John Baskerville (1707 -1775) tried to improve it. He revitalised English typography and set new standards of presswork with black ink on white paper in neo-classical layouts, in a precursor of the private press movement. The books were expensive, and the use of white space to produce an elegant layout mean that customers did not get much text for their money.

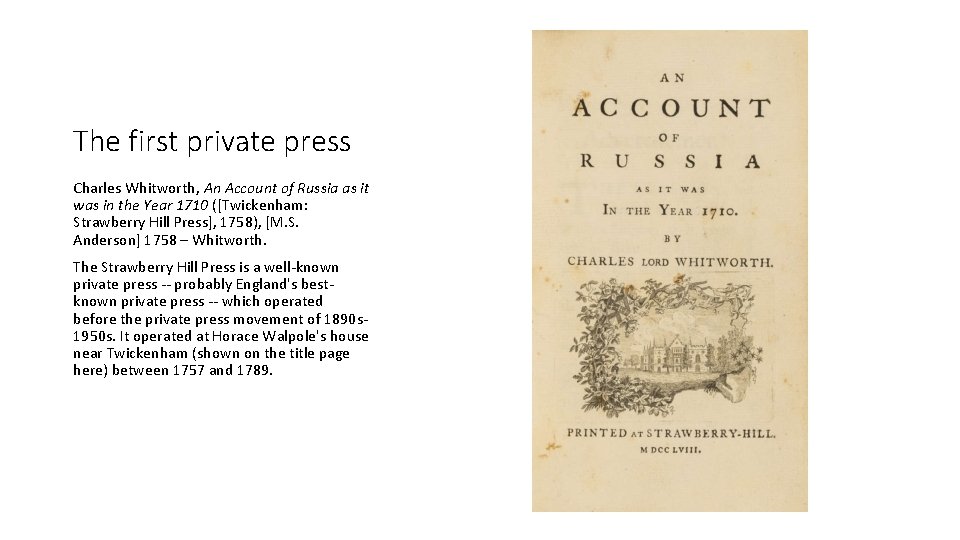

The first private press Charles Whitworth, An Account of Russia as it was in the Year 1710 ([Twickenham: Strawberry Hill Press], 1758), [M. S. Anderson] 1758 – Whitworth. The Strawberry Hill Press is a well-known private press -- probably England's bestknown private press -- which operated before the private press movement of 1890 s 1950 s. It operated at Horace Walpole's house near Twickenham (shown on the title page here) between 1757 and 1789.

![Publishing by subscription John Sibthorp, Flora Graeca Sibthorpiana (London: [H. G. Bohn, 1845 -46]), Publishing by subscription John Sibthorp, Flora Graeca Sibthorpiana (London: [H. G. Bohn, 1845 -46]),](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/241579d55ab0f9d5e7ad0ea9663b0c0b/image-27.jpg)

Publishing by subscription John Sibthorp, Flora Graeca Sibthorpiana (London: [H. G. Bohn, 1845 -46]), [Rare] T 4 a [Sibthorp] elf Publication by subscription, like publication by conger, is a form of risk management, favoured especially for particularly expensive and specialised works. Subscribers order books and sometimes pay for them in advance. The system was practised from the mid-sixteenth century and was favoured especially in the eighteenth century, when more than 2, 000 books were so published.

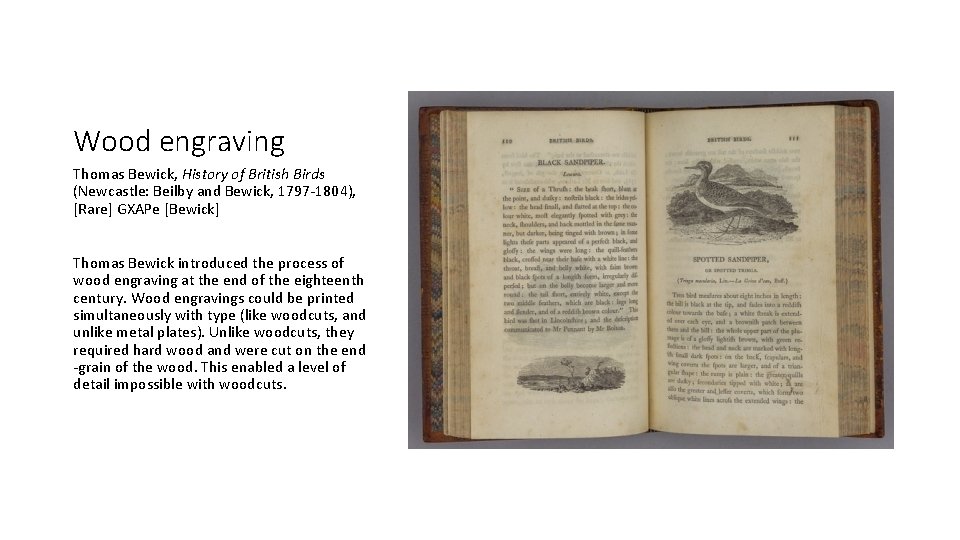

Wood engraving Thomas Bewick, History of British Birds (Newcastle: Beilby and Bewick, 1797 -1804), [Rare] GXAPe [Bewick] Thomas Bewick introduced the process of wood engraving at the end of the eighteenth century. Wood engravings could be printed simultaneously with type (like woodcuts, and unlike metal plates). Unlike woodcuts, they required hard wood and were cut on the end -grain of the wood. This enabled a level of detail impossible with woodcuts.

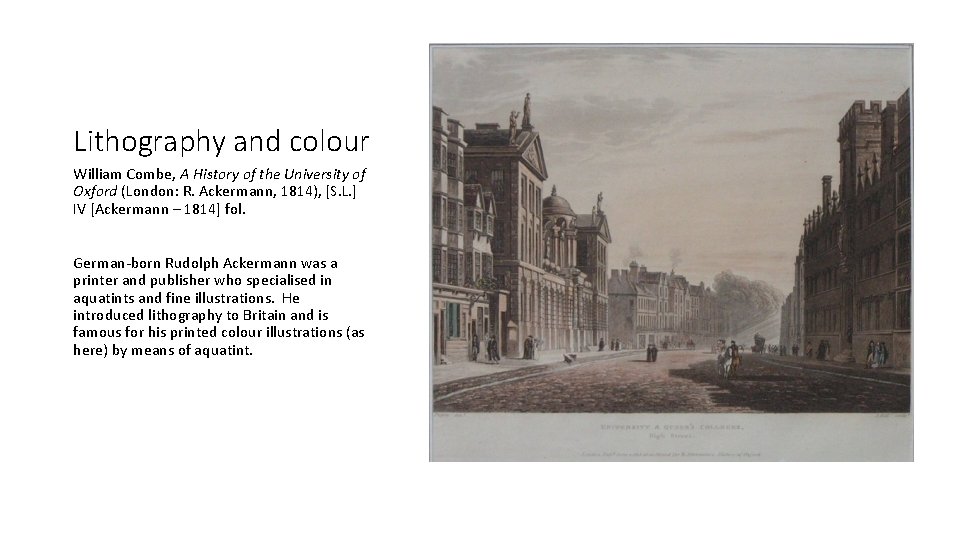

Lithography and colour William Combe, A History of the University of Oxford (London: R. Ackermann, 1814), [S. L. ] IV [Ackermann – 1814] fol. German-born Rudolph Ackermann was a printer and publisher who specialised in aquatints and fine illustrations. He introduced lithography to Britain and is famous for his printed colour illustrations (as here) by means of aquatint.

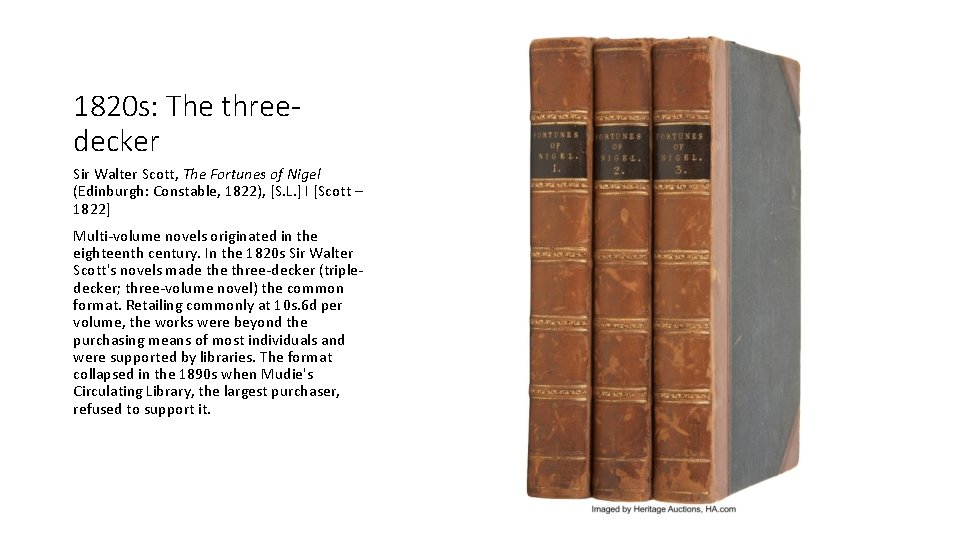

1820 s: The threedecker Sir Walter Scott, The Fortunes of Nigel (Edinburgh: Constable, 1822), [S. L. ] I [Scott – 1822] Multi-volume novels originated in the eighteenth century. In the 1820 s Sir Walter Scott's novels made three-decker (tripledecker; three-volume novel) the common format. Retailing commonly at 10 s. 6 d per volume, the works were beyond the purchasing means of most individuals and were supported by libraries. The format collapsed in the 1890 s when Mudie's Circulating Library, the largest purchaser, refused to support it.

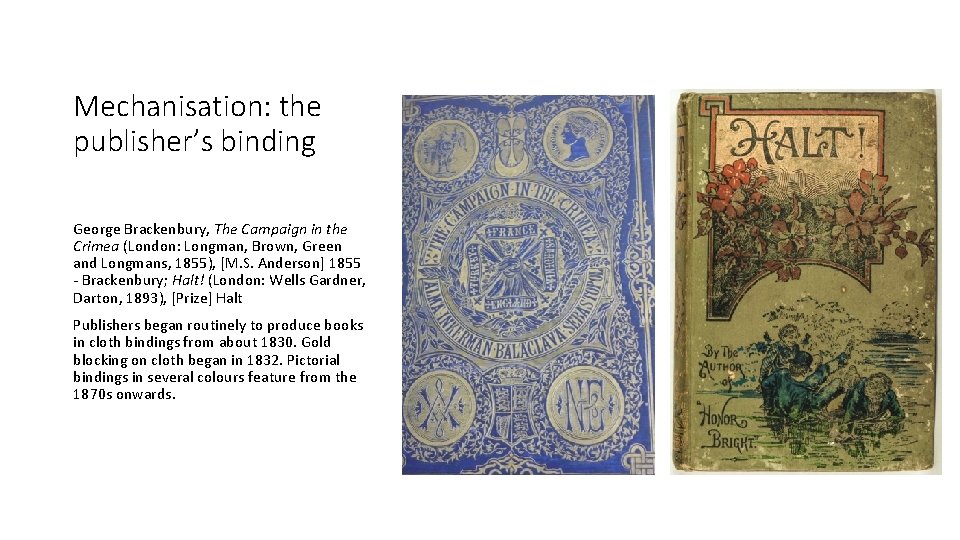

Mechanisation: the publisher’s binding George Brackenbury, The Campaign in the Crimea (London: Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans, 1855), [M. S. Anderson] 1855 - Brackenbury; Halt! (London: Wells Gardner, Darton, 1893), [Prize] Halt Publishers began routinely to produce books in cloth bindings from about 1830. Gold blocking on cloth began in 1832. Pictorial bindings in several colours feature from the 1870 s onwards.

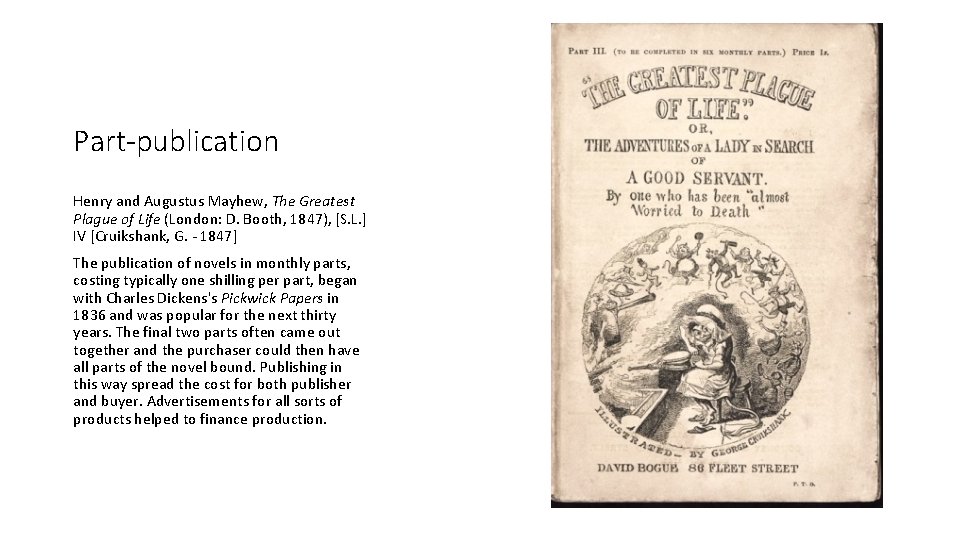

Part-publication Henry and Augustus Mayhew, The Greatest Plague of Life (London: D. Booth, 1847), [S. L. ] IV [Cruikshank, G. - 1847] The publication of novels in monthly parts, costing typically one shilling per part, began with Charles Dickens's Pickwick Papers in 1836 and was popular for the next thirty years. The final two parts often came out together and the purchaser could then have all parts of the novel bound. Publishing in this way spread the cost for both publisher and buyer. Advertisements for all sorts of products helped to finance production.

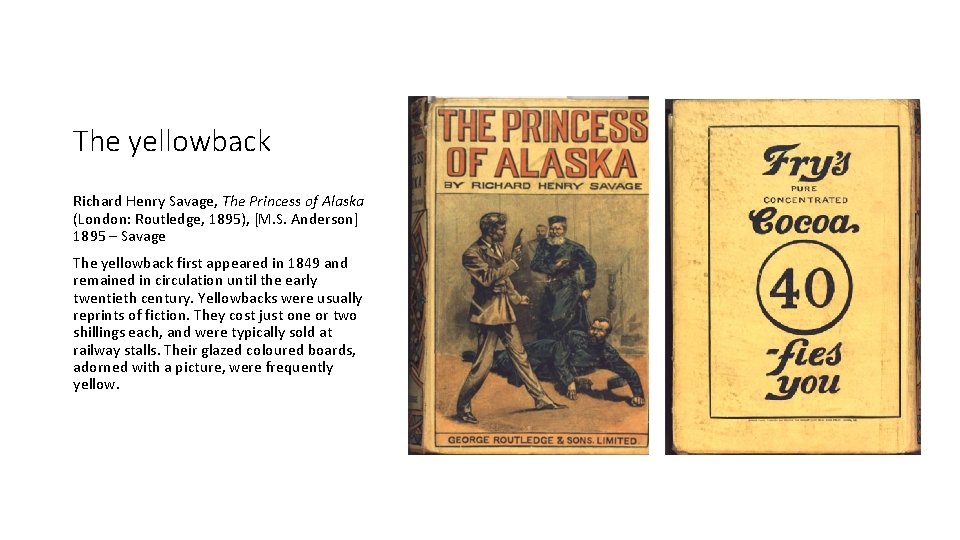

The yellowback Richard Henry Savage, The Princess of Alaska (London: Routledge, 1895), [M. S. Anderson] 1895 – Savage The yellowback first appeared in 1849 and remained in circulation until the early twentieth century. Yellowbacks were usually reprints of fiction. They cost just one or two shillings each, and were typically sold at railway stalls. Their glazed coloured boards, adorned with a picture, were frequently yellow.

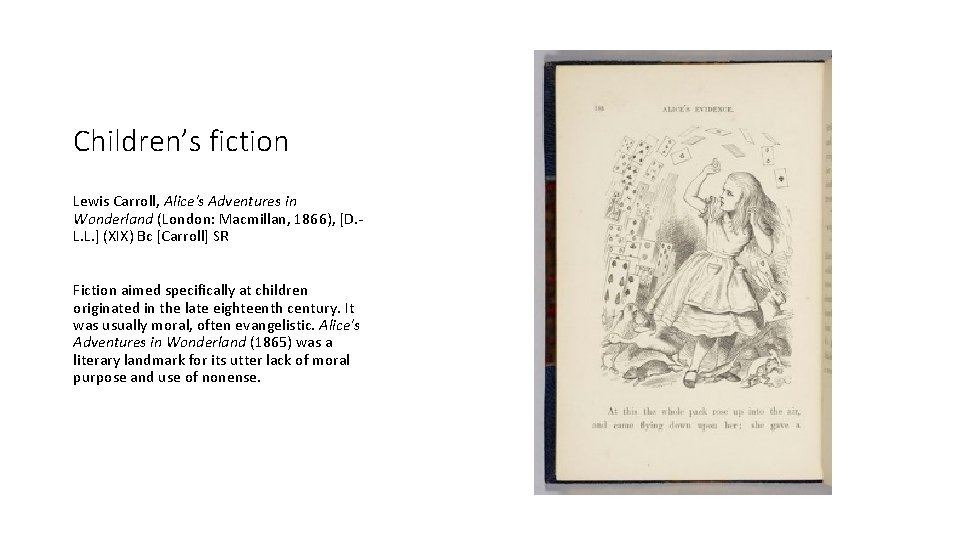

Children’s fiction Lewis Carroll, Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (London: Macmillan, 1866), [D. L. L. ] (XIX) Bc [Carroll] SR Fiction aimed specifically at children originated in the late eighteenth century. It was usually moral, often evangelistic. Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865) was a literary landmark for its utter lack of moral purpose and use of nonense.

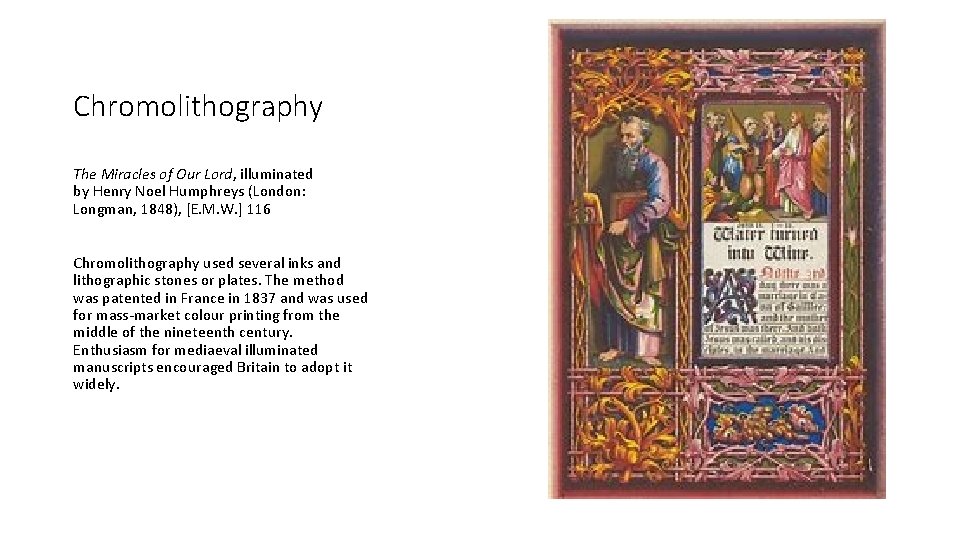

Chromolithography The Miracles of Our Lord, illuminated by Henry Noel Humphreys (London: Longman, 1848), [E. M. W. ] 116 Chromolithography used several inks and lithographic stones or plates. The method was patented in France in 1837 and was used for mass-market colour printing from the middle of the nineteenth century. Enthusiasm for mediaeval illuminated manuscripts encouraged Britain to adopt it widely.

![Mechanised colour printing Kate Greenaway's Almanack (London: G. Routledge, 1890 s), [S. L. ] Mechanised colour printing Kate Greenaway's Almanack (London: G. Routledge, 1890 s), [S. L. ]](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/241579d55ab0f9d5e7ad0ea9663b0c0b/image-36.jpg)

Mechanised colour printing Kate Greenaway's Almanack (London: G. Routledge, 1890 s), [S. L. ] IV [Greenaway - 1890] Although colour printing was possible as early as the fifteenth century, it was difficult. In the nineteenth century chromolithography vied with printing in three or more colours from woodblocks. The illustration here is by Edmund Evans (1826 -1905), who perfected this technique.

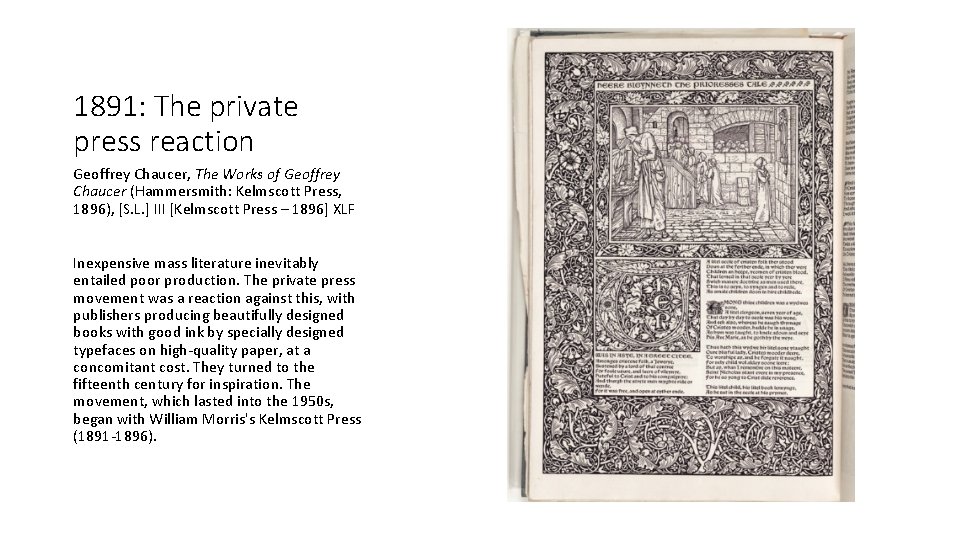

1891: The private press reaction Geoffrey Chaucer, The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer (Hammersmith: Kelmscott Press, 1896), [S. L. ] III [Kelmscott Press – 1896] XLF Inexpensive mass literature inevitably entailed poor production. The private press movement was a reaction against this, with publishers producing beautifully designed books with good ink by specially designed typefaces on high-quality paper, at a concomitant cost. They turned to the fifteenth century for inspiration. The movement, which lasted into the 1950 s, began with William Morris's Kelmscott Press (1891 -1896).

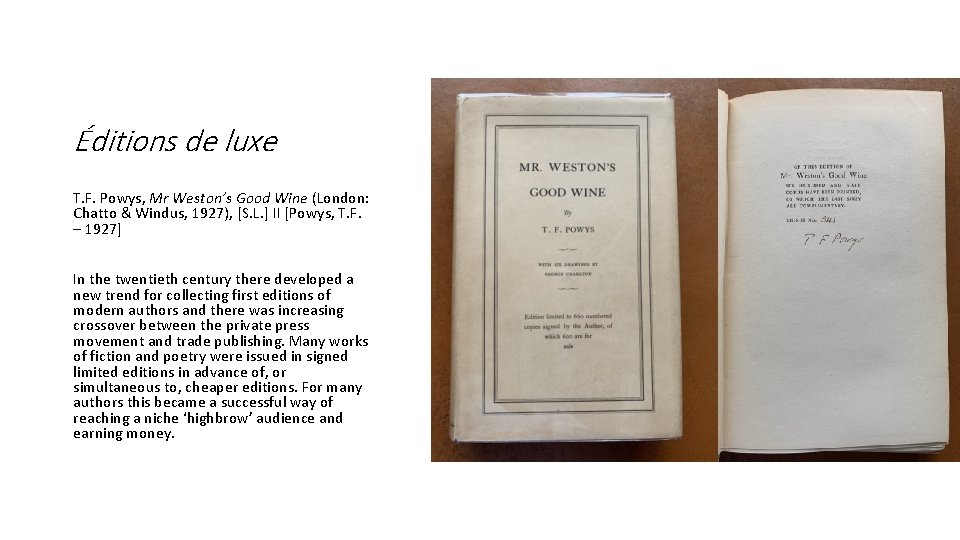

Éditions de luxe T. F. Powys, Mr Weston’s Good Wine (London: Chatto & Windus, 1927), [S. L. ] II [Powys, T. F. – 1927] In the twentieth century there developed a new trend for collecting first editions of modern authors and there was increasing crossover between the private press movement and trade publishing. Many works of fiction and poetry were issued in signed limited editions in advance of, or simultaneous to, cheaper editions. For many authors this became a successful way of reaching a niche ‘highbrow’ audience and earning money.

![Books and film Arnold Bennett, Piccadilly: Story of the Film (London: Readers Library, [1929]), Books and film Arnold Bennett, Piccadilly: Story of the Film (London: Readers Library, [1929]),](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/241579d55ab0f9d5e7ad0ea9663b0c0b/image-39.jpg)

Books and film Arnold Bennett, Piccadilly: Story of the Film (London: Readers Library, [1929]), YXPY/Ben. The arrival of film and especially ‘talkies’ in the late 1920 s provided opportunities for authors and the book industry to exploit cross-media relationships. These not only included tie-in editions of adaptations of famous novels, but novelisations of famous films. Volumes in the Readers Library series were a mainstay of Woolworths and other general stores.

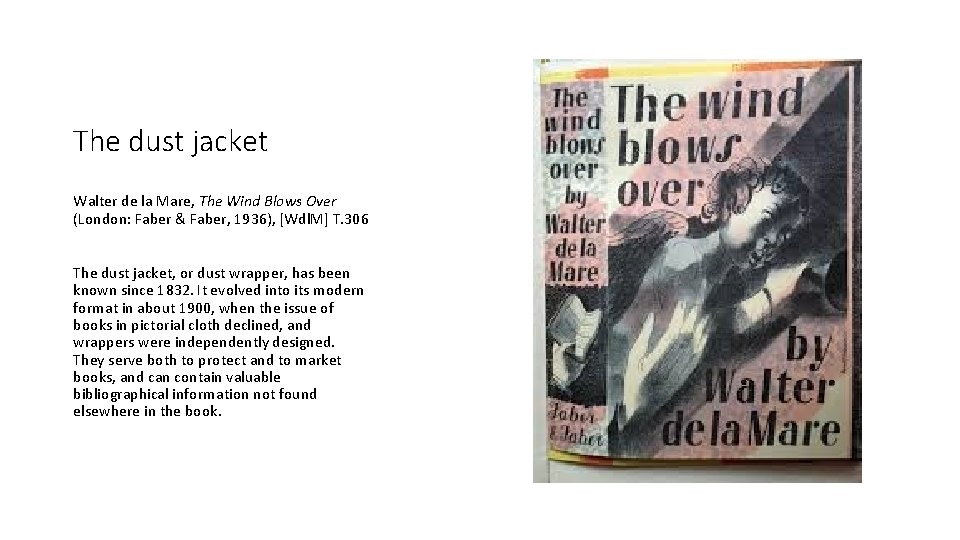

The dust jacket Walter de la Mare, The Wind Blows Over (London: Faber & Faber, 1936), [Wdl. M] T. 306 The dust jacket, or dust wrapper, has been known since 1832. It evolved into its modern format in about 1900, when the issue of books in pictorial cloth declined, and wrappers were independently designed. They serve both to protect and to market books, and can contain valuable bibliographical information not found elsewhere in the book.

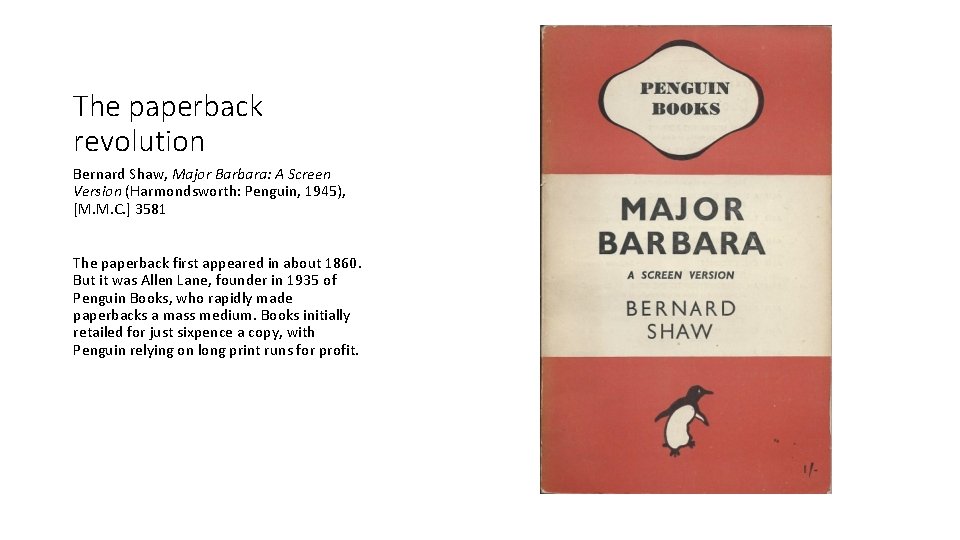

The paperback revolution Bernard Shaw, Major Barbara: A Screen Version (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1945), [M. M. C. ] 3581 The paperback first appeared in about 1860. But it was Allen Lane, founder in 1935 of Penguin Books, who rapidly made paperbacks a mass medium. Books initially retailed for just sixpence a copy, with Penguin relying on long print runs for profit.

- Slides: 41