The Art of Teaching Science Introduction and Welcome

- Slides: 30

The Art of Teaching Science Introduction and Welcome

The Art of Teaching Science Welcome to The Art of Teaching Science. We hope you will find this book to be a valuable resource for your professional development and creative expression as a middle and high school science teacher. Our approach is humanistic in our concern for the interests, needs, and welfare of people and our belief in the capacity of science education to enrich human life. Jack Hassard & Michael Dias

Chapter Slide Shows • There are 12 slide shows, one for each chapter. They are designed to be used by students and instructors. For students, the slides give a multimedia overview for each chapter. For the instructor, the slide shows can be used in whole or part to augment course syllabi, and online experiences for students.

Philosophy • The Art of Teaching Science is rooted in the philosophy that initial and continuing preparation of science teachers should develop professional artistry. • In this view, the learning to teach process involves encounters with peers, professional teachers, and science teacher educators. • A number of pedagogical learning tools have been integrated into the Art of Teaching Science. • These tools involve: – Inquiry and experimentation – Reflection through writing and discussions – Experiences with students, science curriculum and pedagogy • Becoming a science teacher is a creative process. In the view espoused here, you will be encouraged to "invent" and "construct" ideas about science teaching through your interaction with your peers, teachers and your instructors.

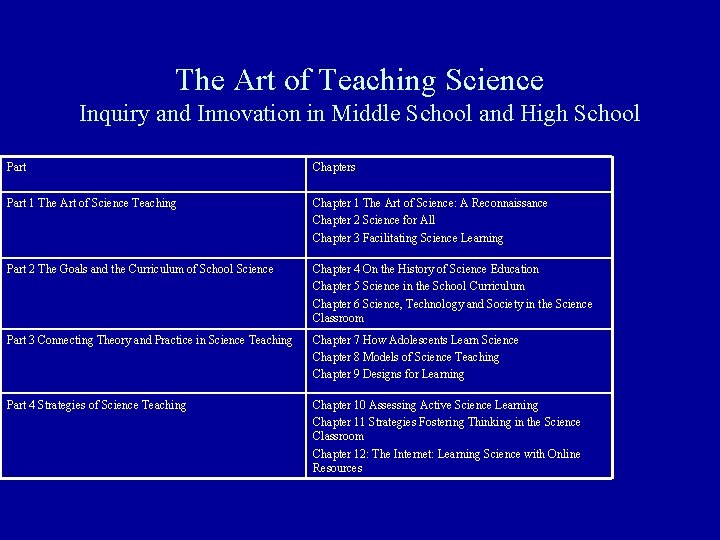

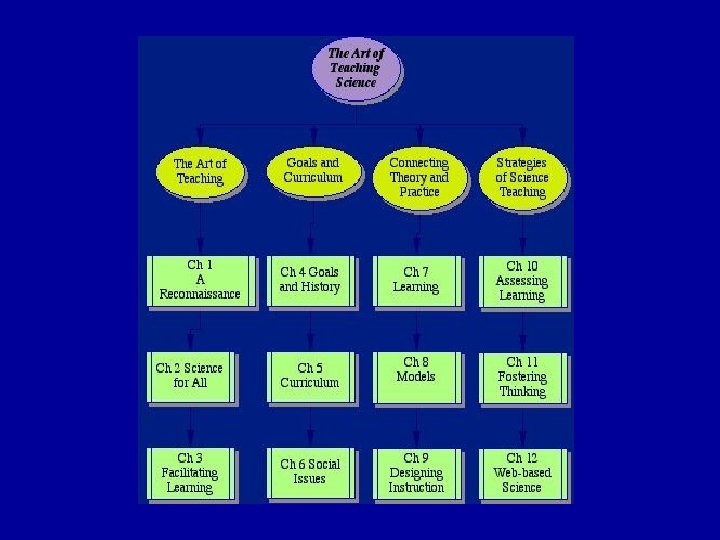

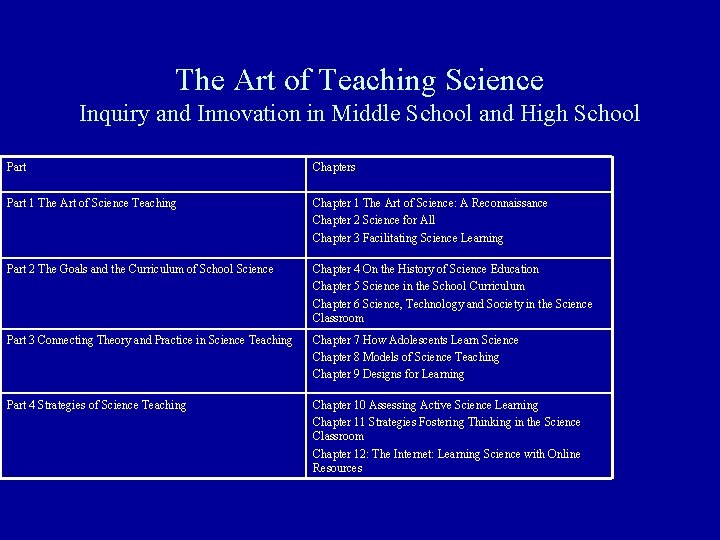

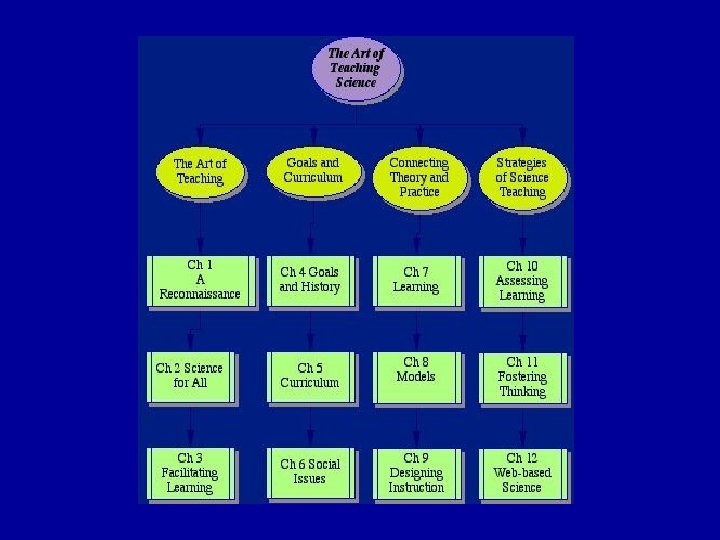

The Art of Teaching Science Inquiry and Innovation in Middle School and High School Part Chapters Part 1 The Art of Science Teaching Chapter 1 The Art of Science: A Reconnaissance Chapter 2 Science for All Chapter 3 Facilitating Science Learning Part 2 The Goals and the Curriculum of School Science Chapter 4 On the History of Science Education Chapter 5 Science in the School Curriculum Chapter 6 Science, Technology and Society in the Science Classroom Part 3 Connecting Theory and Practice in Science Teaching Chapter 7 How Adolescents Learn Science Chapter 8 Models of Science Teaching Chapter 9 Designs for Learning Part 4 Strategies of Science Teaching Chapter 10 Assessing Active Science Learning Chapter 11 Strategies Fostering Thinking in the Science Classroom Chapter 12: The Internet: Learning Science with Online Resources

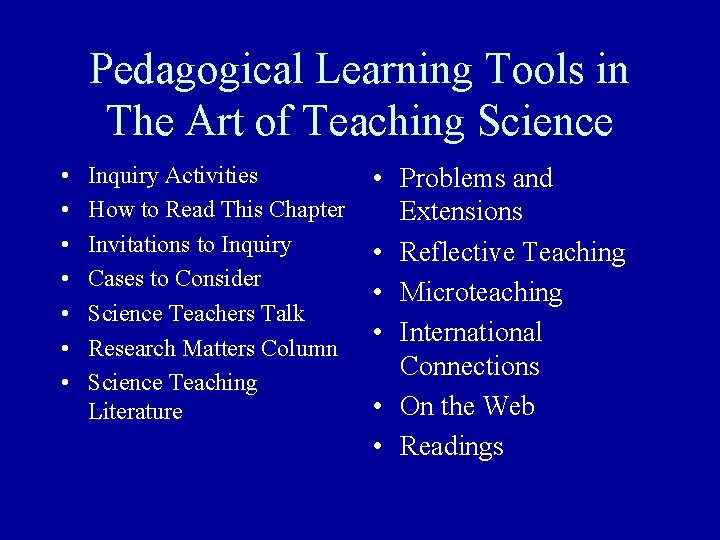

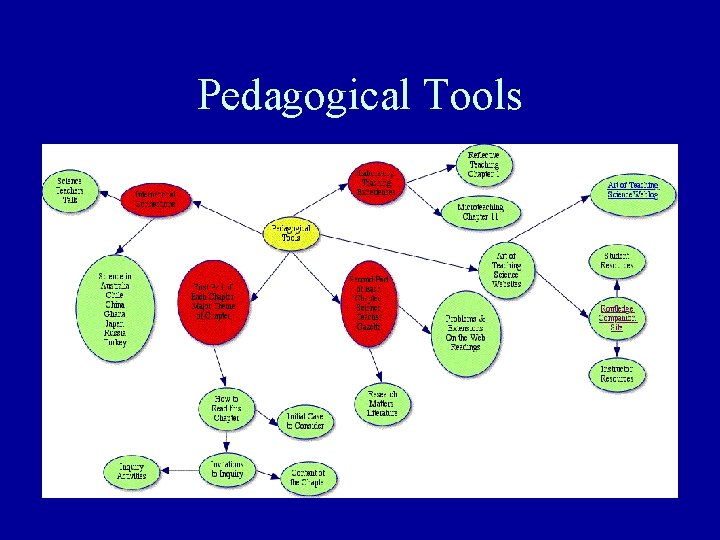

Pedagogical Learning Tools in The Art of Teaching Science • • Inquiry Activities How to Read This Chapter Invitations to Inquiry Cases to Consider Science Teachers Talk Research Matters Column Science Teaching Literature • Problems and Extensions • Reflective Teaching • Microteaching • International Connections • On the Web • Readings

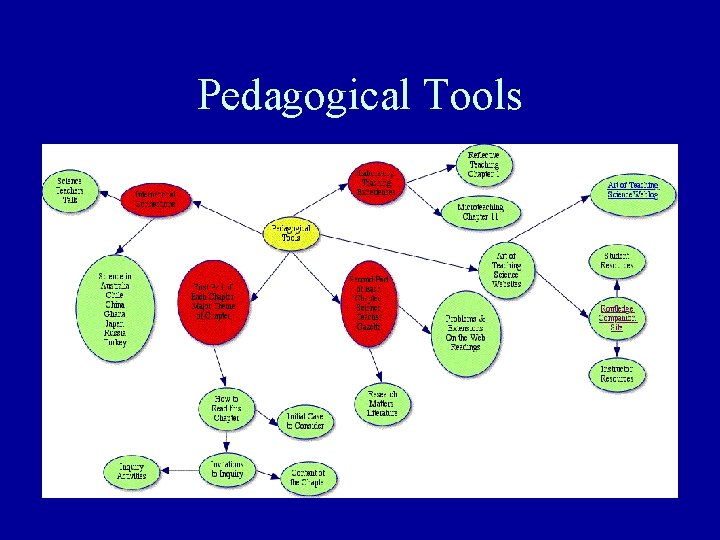

Pedagogical Tools

Inquiry Activities • Inquiry Activities are designed to engage teachers in a variety of learning-to-teach conducted individually and in collaboration with teaching colleagues in middle and high schools as well as at the university. • The inquiry activities are based on a constructivist learning model and – enable students to use their existing conceptions in problem solving situations; – enable students to design a plan to investigate a problem for a particular context and situation; – can be solved in many ways thereby resulting in multiple solutions; – engage students in reflective and high level cognitive thinking; – engage students in cooperative learning groups

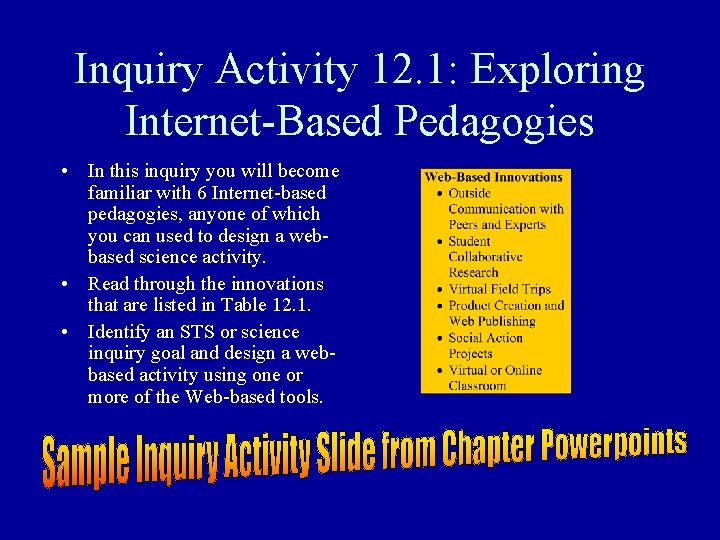

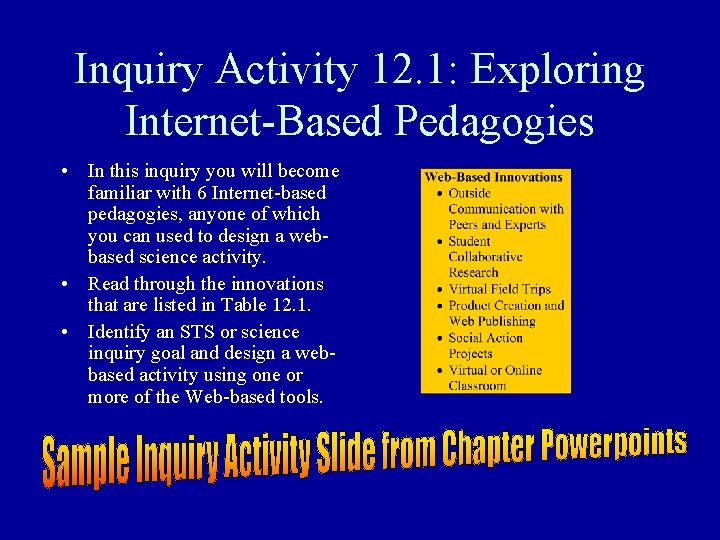

Inquiry Activity 12. 1: Exploring Internet-Based Pedagogies • In this inquiry you will become familiar with 6 Internet-based pedagogies, anyone of which you can used to design a webbased science activity. • Read through the innovations that are listed in Table 12. 1. • Identify an STS or science inquiry goal and design a webbased activity using one or more of the Web-based tools.

How to Read This Chapter • This chapter is a reconnaissance of the profession of science teaching, and also a place to begin the learning-to-teach process. There are some activities that are designed to help you explore some of your prior conceptions about science teaching (Inquiry Activity 1. 1), and other activities designed to have you investigate the ideas that experienced teachers hold about teaching, and students about science. All of these are here to help you build upon your prior knowledge and to help you in the construction of your ideas about teaching. You might get the most out of this chapter by skimming the main sections, and then coming back to deliberately move though the chapter.

Invitations to Inquiry • • • How important is it to the secondary science teacher to know about learning theory? What is constructivism, and why has it emerged as one of the most significant explanations of student learning? How do cognitive psychologists explain student learning? How do social psychologist explain student learning? How do behavioral theories explain student learning in science? What was the contribution of theorists like Skinner, Bruner, Piaget, Vygotsky, and von Glasersfeld to secondary science teaching? What is meant by multiple intelligences and how does it impact student learning? How do learning styles of students influence learning in the classroom? What is metacognition, and how can metacognition help students learn science?

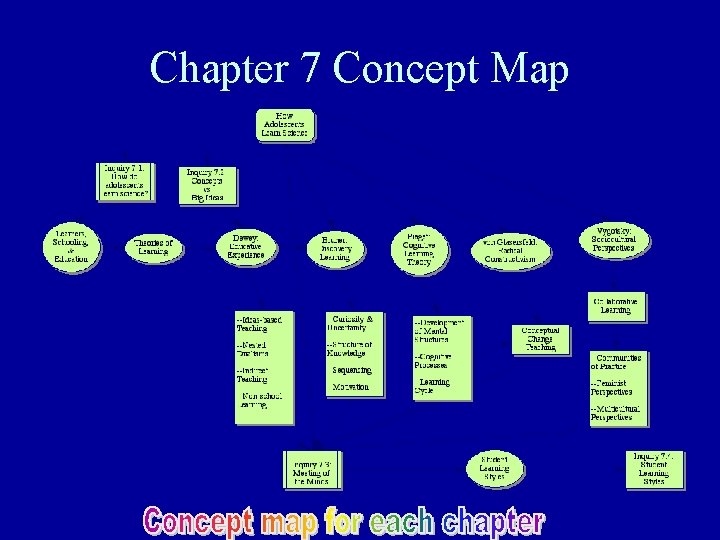

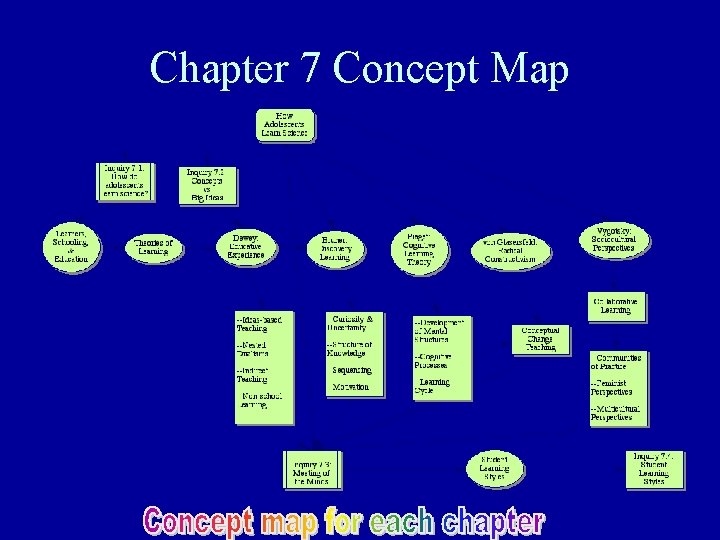

Chapter 7 Concept Map

Cases to Consider Cases are problem solving dilemmas based on actual and fictional events of science teaching. The professions of law, business, and medicine have long used the case method which has been more recently applied to teacher education. Cases in The Art of Teaching Science consist of a brief presentation of the case followed by a dilemma statement. Cases can be explored in a variety of ways: role playing, cooperative problem solving, written responses followed by group discussions, and debates. Case enactments can also be video taped for replay and analysis. After some work in schools, students can write their own case and respond to those of their colleagues. Each chapter begins with a Case to Consider.

• • Cases Approach The Case Ruth Wilson, a second year high school biology teacher in a community that has only one high school, took a graduate course in the summer at the local university. In the course, she became extremely interested in a theory of learning, called "constructivism” proposed by several theorists. Constructivism, as she understood it, provided a framework to understand how students acquired knowledge. One of the basic notions underlying theory was that students “constructed and made meaning” of their experiences. The theory provides more freedom for the students in terms of their own thinking processes. Ms. Wilson feels strongly that this “constructivist” framework supported her teaching philosophy better than the more structured approach she was using during her first year of teaching. Prior to the opening of school, Ms. Wilson changed her curriculum plans to reflect the constructivist theory. She spent the first two weeks of school helping the students become skilled and familiar with hands-on learning. For many of her students, this was a new venture. She planned activities where students had to make choices among objectives, or activities, or content. Knowing that students like to work together, she decided to place students in small teams. At the end of the two weeks, she instructed the teams to decide and select the activities and content in the first part of the text that would interest them. They should formulate a plan, and carry it out for the remainder of the grading period. A few weeks later, a rather irate parent called Mr. . Brady, the principal of the school, complaining that her son is wasting his time in Ms. Wilson's class. The parent complained that her son was not learning anything, and she demanded a conference with Ms. Wilson. • • The Problem How would you deal with this situation? What would you say to the parent? Is Ms. Wilson on sound footing regarding her theory of teaching? How do explain your teaching theory to your principal? What is your personal view on this approach to teaching and learning?

Reflective Teaching • The Art of Teaching Science provides teaching strategies that facilitate the development of reflective thought. Inquiry Activity 1. 2, entitled Microteach: Reflective Teaching invites you to select an instructional objective (see Table 1. 2) for which you will plan 20 minutes of teaching that will help the learners begin to meet this objective. • A powerful aspect of Reflective Teaching is that it "teaches" teachers a metacognitve tool for thinking about their teaching, and once they understand the process, teachers can apply the approach in any teaching situation.

Inquiry 1. 2: Reflective Teaching • • In this inquiry you’ll teach a science lesson to a small group using any of the models in the chapter using a three stage experience: – Prepare – Teach – Reflect You’ll use the experience to find out how successful you were. Details of the Reflective Teaching experience are outlined in Inquiry 1. 2.

Microteaching is a laboratory approach to teaching developed some years ago, and used quite effectively first by the Peace Corps, and then by colleges of education in initial and continuing teacher education programs. Although microteaching is used initially in Inquiry 1. 2, it is detailed in Chapter 11, and used in the context of helping teachers develop a model for practicing and receiving feedback about teaching strategies. Since microteaching is scaled down teaching, it works very well in small cooperative groups of peers, as well as with students in a school context. You will find the approach to microteaching detailed in Inquiry Activity 11. 1. Students can prepare brief lessons, teach them to a small group of peers or students, meet with a peer coach, and then reteach the lesson based on suggestions made in the peer coaching conference.

Inquiry 11. 1: Microteaching • • Microteaching is scaled down teaching. You will use it to explore the interactive teaching strategies in chapter 11. Prepare a 5 -8 minute lesson and use it to focus on one or more of the teaching strategies (advance organizers, questioning, using examples, etc. ). Teach the lesson to a small group of peers; use the video tape to reflect and make changes in the lesson for a reteach episode. How successful were you?

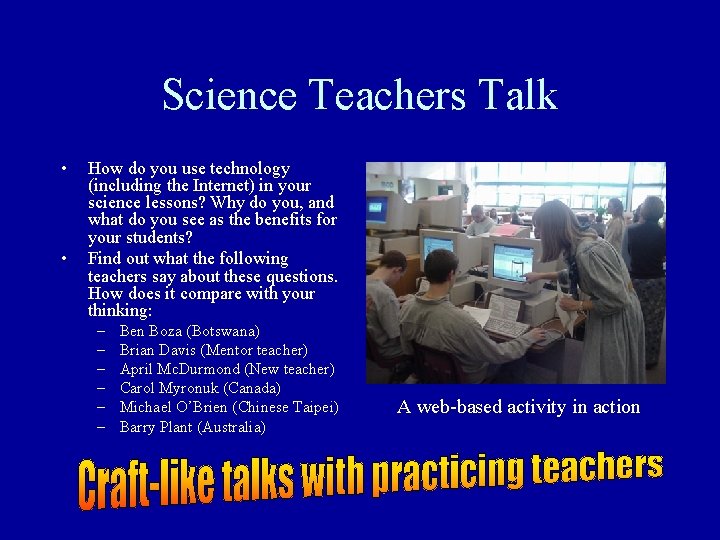

Science Teachers Talk • Interviews with several practicing middle school and high school science teachers from several countries were conducted to create the Science Teachers Talk column of the Science Teaching Gazette. The teachers were asked to respond to a questionnaire on science teaching. The questions corresponded to the text chapters, and can be used as a stimulus for discussion, and problem solving. • Readers of The Art of Teaching Science may be asked to respond to the interview questions before reading the teachers' responses, and afterwards, compare their approaches and opinions. These craft-talk columns are rich with the wisdom-of-practice that is an integral part of the knowledge of science teaching.

Science Teachers Talk • • How do you use technology (including the Internet) in your science lessons? Why do you, and what do you see as the benefits for your students? Find out what the following teachers say about these questions. How does it compare with your thinking: – – – Ben Boza (Botswana) Brian Davis (Mentor teacher) April Mc. Durmond (New teacher) Carol Myronuk (Canada) Michael O’Brien (Chinese Taipei) Barry Plant (Australia) A web-based activity in action

Research Matters • There is a growing emphasis on the importance of involving practicing science teachers not only in applying science education research, but also in conducting action research and sharing their practical knowledge. • The Science Teaching Gazette includes Research Matters articles written by members of the National Association for Research in Science Teaching (NARST).

Science Education Literature Some of the volumes of the Science Teaching Gazette includes excerpts from the literature of science teaching. The literature pieces have been included to enrich the investigation of science teaching, to extend the context of learning to include the work of the science and science education community, and to introduce teachers to journals and books in the field.

Science is Not Words* • Read Dr. George Feynman’s article, “Science is not words. ” • How does Feynman’s view of science stack up with yours? How might this be applied to teaching? • Follow-up with a visit to a Feynman Site: http: //www. amasci. com/feynma n. html

On the Web • A collection of websites that relate to the chapter. • They are located in the Gazette, and they are also linked in this website for easy access to these resources

Websites • Routledge Companion Website – Student Resources – Instructor Resources • Art of Teaching Science Weblog – Interactive Discussions – Resources for Teaching

Readings • A collection of readings, for each chapter, including books and journal articles • designed to help you go further in your exploration of science teaching.

Problems and Extension • • Prepare a Web-based lesson using one of the following Web-based tools: key pals, online discussions, chat, tele-mentoring, pooled data analysis, tale-field trip or social action project. Include the goals for the lesson, and how students would be active learners in the lesson. Discuss the implications of using the Web to make your teaching environment a “global classroom”. What do you think will be the outcomes and benefits for your students, and colleagues? Locate a science museum on the Web, and design a tele-field trip using the museum as the basis for your project. Design a pooled data analysis project for a group of middle or high school students in any content area of science. Visit some of the examples of pooled data analysis projects identified in the chapter. After studying these projects, outline a new project by working with a group of peers. Share the project by putting it on the Web, and presenting it to a group of peers.

International Connections Colleagues from other countries wrote brief descriptions of the curriculum and teaching issues in Australia, Chile, China, Ghana, Japan, Russia, Turkey. As science educators, we are members of a community of practice that is worldwide. What are the issues in other countries, and what do these teach us about our own issues? These science educators have based their writing on personal experiences with the culture, and in most cases the authors were born, educated and taught in the country they described.

Science in… • • Australia Chile China Ghana Japan Russia Turkey