TESTING TESTING OUTLINE Plan Tests Design Tests White

![TESTING OVERVIEW � [9. 1] testing is the process of finding differences between the TESTING OVERVIEW � [9. 1] testing is the process of finding differences between the](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/5bee8f02e6b3fcb2867f72246cd0debc/image-3.jpg)

![TESTING OVERVIEW Expected results Software configuration Testing [9. 2] Test results Evaluation Reliability & TESTING OVERVIEW Expected results Software configuration Testing [9. 2] Test results Evaluation Reliability &](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/5bee8f02e6b3fcb2867f72246cd0debc/image-4.jpg)

![PLAN TESTS [9. 5. 1] è It is impossible to completely test the entire PLAN TESTS [9. 5. 1] è It is impossible to completely test the entire](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/5bee8f02e6b3fcb2867f72246cd0debc/image-9.jpg)

![DESIGN TESTS [9. 3. 2] test case: one way of testing the system (what, DESIGN TESTS [9. 3. 2] test case: one way of testing the system (what,](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/5bee8f02e6b3fcb2867f72246cd0debc/image-10.jpg)

![BASIS PATH TESTING [9. 4. 2] Goal: Goal exercise each independent path in the BASIS PATH TESTING [9. 4. 2] Goal: Goal exercise each independent path in the](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/5bee8f02e6b3fcb2867f72246cd0debc/image-14.jpg)

![OTHER BLACK BOX TECHNIQUES Error Guessing [9. 4. 2] ◦ use application domain experience OTHER BLACK BOX TECHNIQUES Error Guessing [9. 4. 2] ◦ use application domain experience](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/5bee8f02e6b3fcb2867f72246cd0debc/image-31.jpg)

![STATE-BASED TESTING � focuses [9. 4. 2] on comparing the resulting state of a STATE-BASED TESTING � focuses [9. 4. 2] on comparing the resulting state of a](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/5bee8f02e6b3fcb2867f72246cd0debc/image-34.jpg)

![UNIT TESTING Component [9. 4. 2] interface local data structures boundary conditions independent paths UNIT TESTING Component [9. 4. 2] interface local data structures boundary conditions independent paths](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/5bee8f02e6b3fcb2867f72246cd0debc/image-39.jpg)

![INTEGRATION TESTING [9. 4. 3] è If components all work individually, why more be INTEGRATION TESTING [9. 4. 3] è If components all work individually, why more be](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/5bee8f02e6b3fcb2867f72246cd0debc/image-41.jpg)

![SYSTEM TESTING [9. 4. 4] We need to test the entire system to be SYSTEM TESTING [9. 4. 4] We need to test the entire system to be](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/5bee8f02e6b3fcb2867f72246cd0debc/image-46.jpg)

![DEBUGGING [9. 3. 4] �a consequence of testing, but a separate activity – > DEBUGGING [9. 3. 4] �a consequence of testing, but a separate activity – >](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/5bee8f02e6b3fcb2867f72246cd0debc/image-54.jpg)

- Slides: 57

TESTING

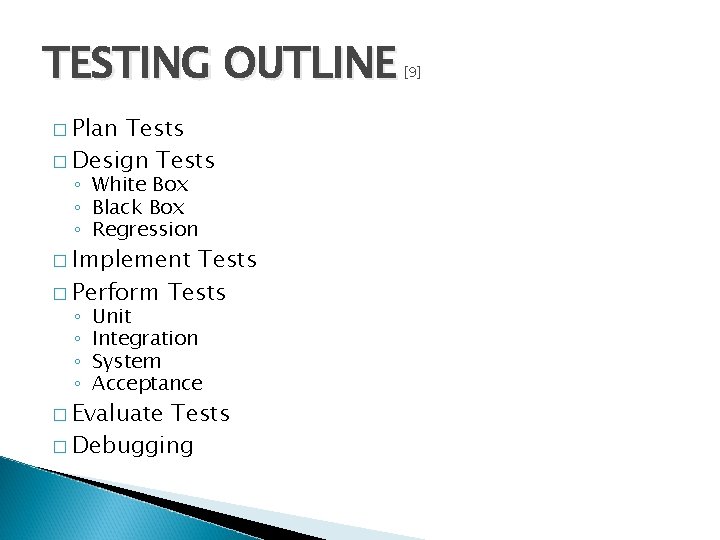

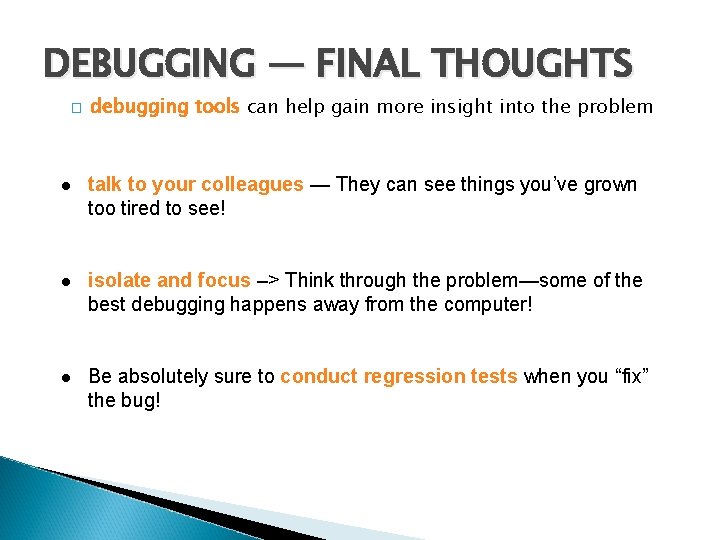

TESTING OUTLINE � Plan Tests � Design Tests ◦ White Box ◦ Black Box ◦ Regression � Implement Tests � Perform Tests ◦ ◦ Unit Integration System Acceptance � Evaluate Tests � Debugging [9]

![TESTING OVERVIEW 9 1 testing is the process of finding differences between the TESTING OVERVIEW � [9. 1] testing is the process of finding differences between the](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/5bee8f02e6b3fcb2867f72246cd0debc/image-3.jpg)

TESTING OVERVIEW � [9. 1] testing is the process of finding differences between the specified (expected) and the observed (existing) system behavior Goal: design tests that will systematically find defects è aim is to break the system usually done by developers that were not involved in system implementation to test a system effectively, must have a detailed understanding of the whole system è not a job for novices it is impossible to completely test a nontrivial system è systems often deployed without being completely tested

![TESTING OVERVIEW Expected results Software configuration Testing 9 2 Test results Evaluation Reliability TESTING OVERVIEW Expected results Software configuration Testing [9. 2] Test results Evaluation Reliability &](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/5bee8f02e6b3fcb2867f72246cd0debc/image-4.jpg)

TESTING OVERVIEW Expected results Software configuration Testing [9. 2] Test results Evaluation Reliability & quality model Error rate data No errors Done Test configuration Errors Debug Corrections è the time uncertainty in testing is the debug part!

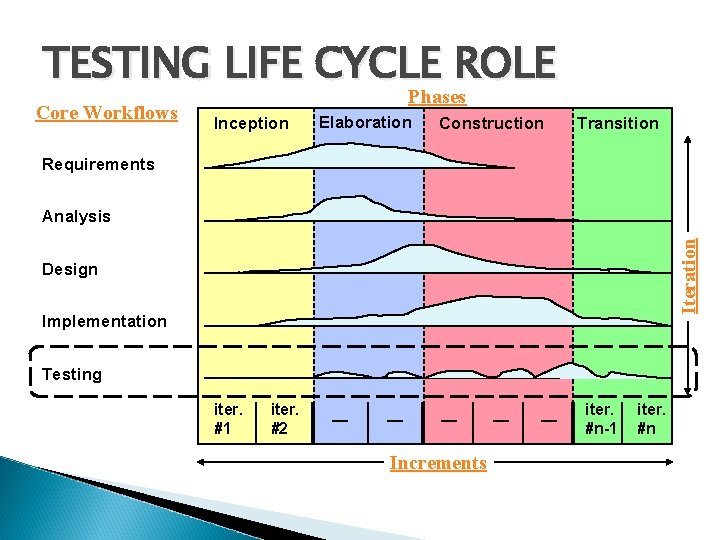

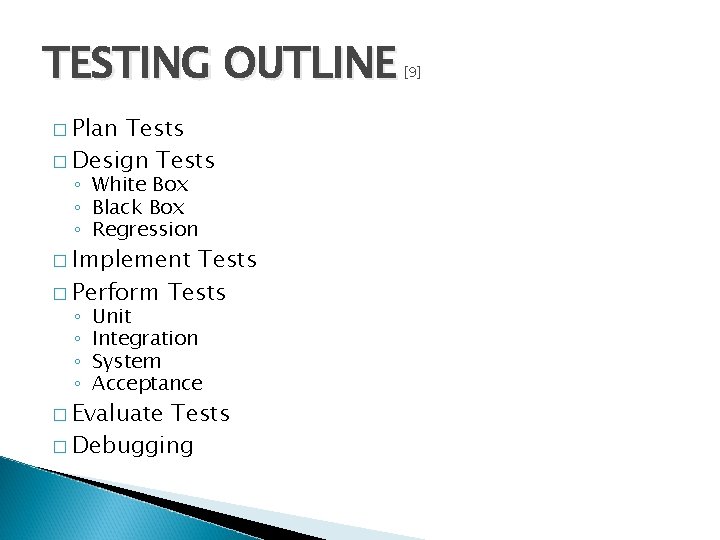

TESTING LIFE CYCLE ROLE Core Workflows Phases Inception Elaboration Construction Transition Requirements Iteration Analysis Design Implementation Testing iter. #1 iter. #2 — — — Increments — — iter. #n-1 iter. #n

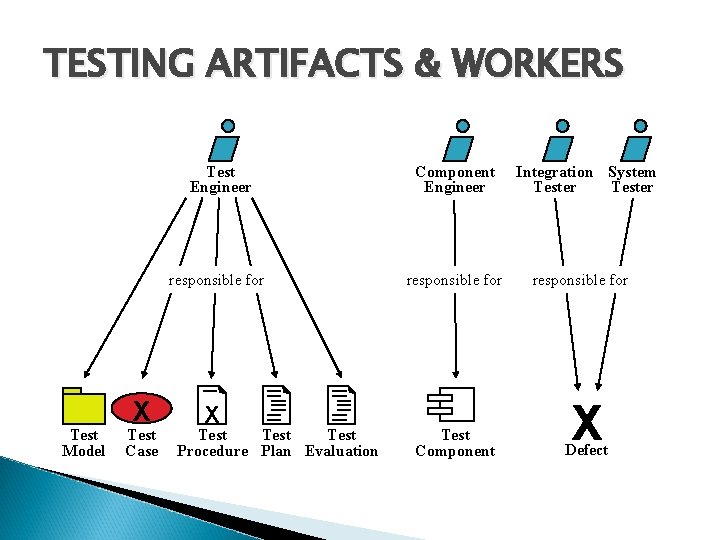

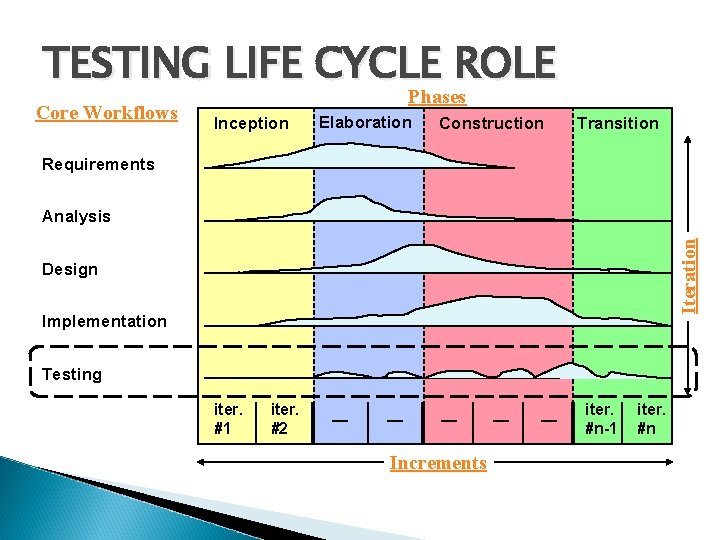

TESTING ARTIFACTS & WORKERS Test Model X Test Case Test Engineer Component Engineer responsible for X Test Procedure Plan Evaluation Test Component Integration System Tester responsible for X Defect

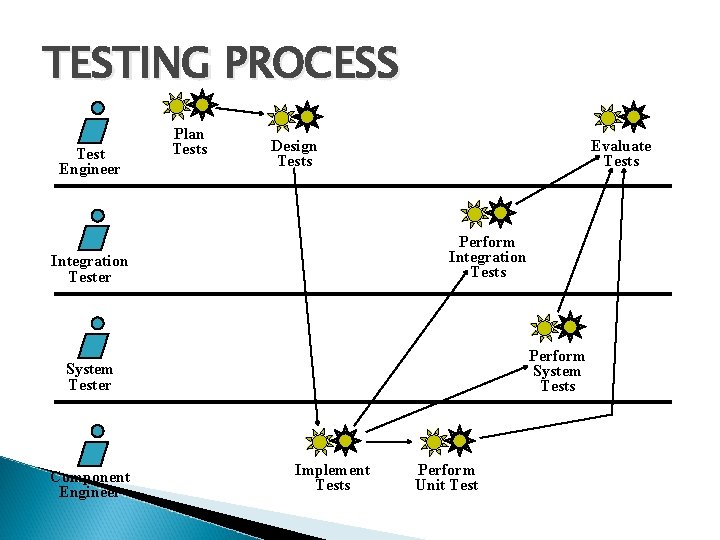

TESTING PROCESS Test Engineer Plan Tests Design Tests Evaluate Tests Perform Integration Tests Integration Tester Perform System Tests System Tester Component Engineer Implement Tests Perform Unit Test

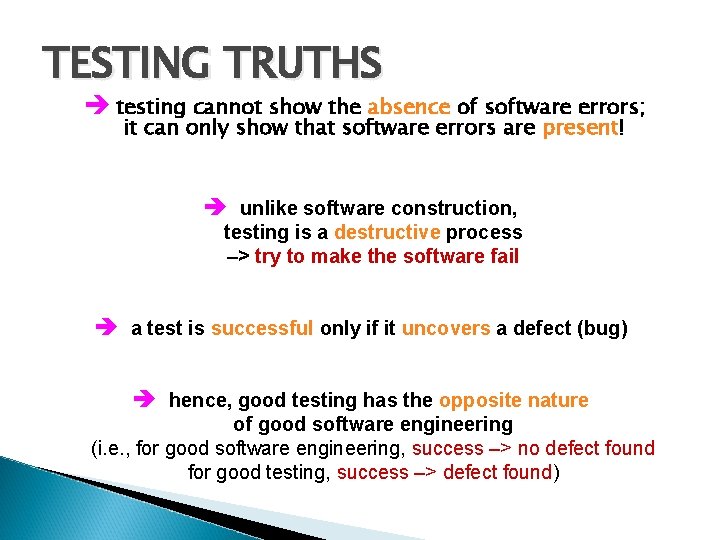

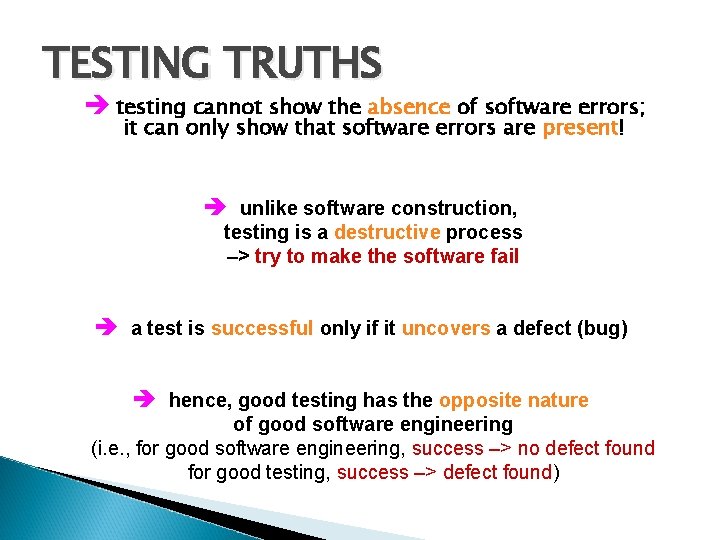

TESTING TRUTHS è testing cannot show the absence of software errors; it can only show that software errors are present! è unlike software construction, testing is a destructive process –> try to make the software fail è a test is successful only if it uncovers a defect (bug) è hence, good testing has the opposite nature of good software engineering (i. e. , for good software engineering, success –> no defect found for good testing, success –> defect found)

![PLAN TESTS 9 5 1 è It is impossible to completely test the entire PLAN TESTS [9. 5. 1] è It is impossible to completely test the entire](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/5bee8f02e6b3fcb2867f72246cd0debc/image-9.jpg)

PLAN TESTS [9. 5. 1] è It is impossible to completely test the entire system! Overall goal: goal design a set of tests that has the highest likelihood of uncovering defects with the minimum amount of time and effort since resources are usually limited (up to 40% of project effort often devoted to testing) Testing strategy: specifies the criteria and goals of testing – what kinds of tests to perform and how to perform them – the required level of test and code coverage – the percentage of tests that should execute with a specific result Estimate of resources required: human/system Schedule for the testing: when to run the tests

![DESIGN TESTS 9 3 2 test case one way of testing the system what DESIGN TESTS [9. 3. 2] test case: one way of testing the system (what,](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/5bee8f02e6b3fcb2867f72246cd0debc/image-10.jpg)

DESIGN TESTS [9. 3. 2] test case: one way of testing the system (what, conditions, how) è knowing the internal workings of a component, design test cases to ensure the component performs according to specification White Box Testing: “testing-in-the-small” Derive test cases to verify component logic based on data/control structures. –> Availability of source code is required. è knowing the specified functionality of a component, design test cases to demonstrate that the functionality is fully operational Black Box Testing: “testing-in-the-large” Derive test cases to verify component functionality based on the inputs and outputs. –> Availability of source code is not required! Regression Testing: selective White Box and Black Box re-testing to ensure that no new defects are introduced after a change

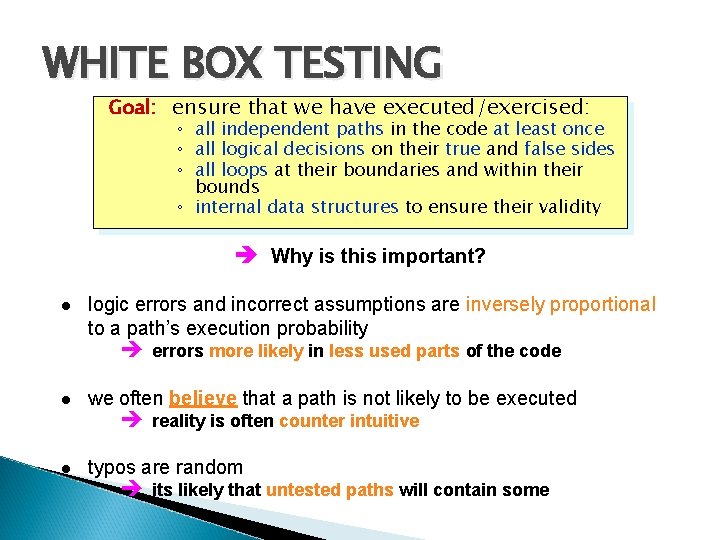

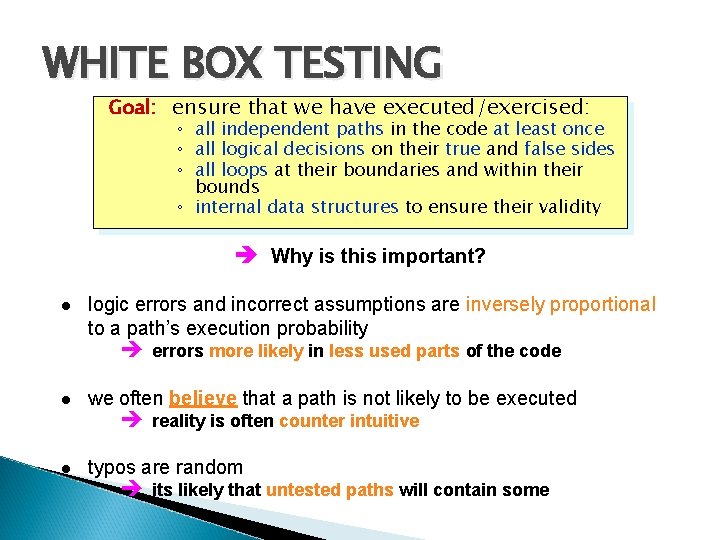

WHITE BOX TESTING Goal: ensure that we have executed/exercised: ◦ all independent paths in the code at least once ◦ all logical decisions on their true and false sides ◦ all loops at their boundaries and within their bounds ◦ internal data structures to ensure their validity è Why is this important? logic errors and incorrect assumptions are inversely proportional to a path’s execution probability è errors more likely in less used parts of the code we often believe that a path is not likely to be executed typos are random è reality is often counter intuitive è its likely that untested paths will contain some

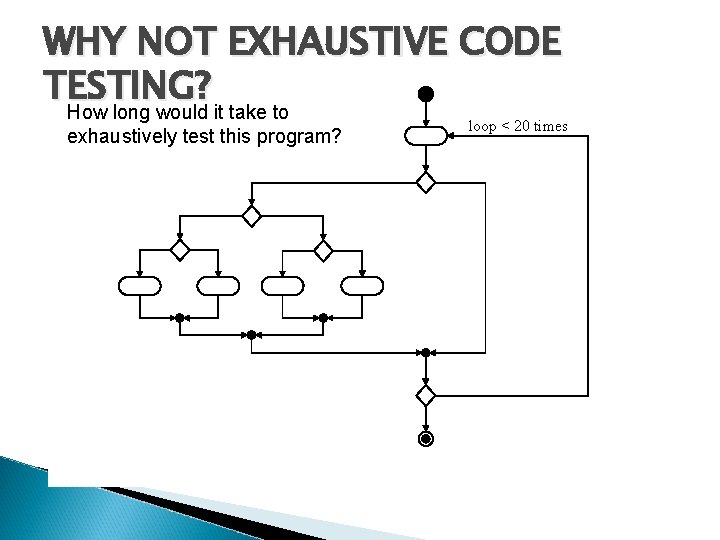

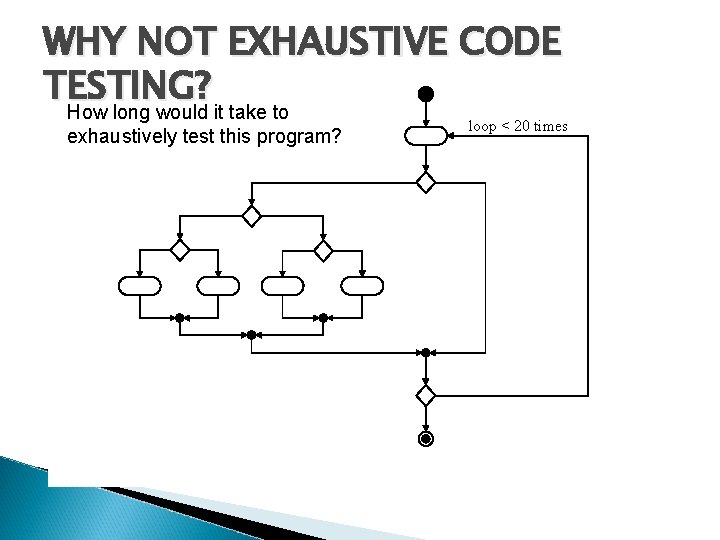

WHY NOT EXHAUSTIVE CODE TESTING? How long would it take to exhaustively test this program? è There are 1014 possible paths! It takes 3, 170 years to exhaustively test the program if each test requires 1 ms!! loop < 20 times

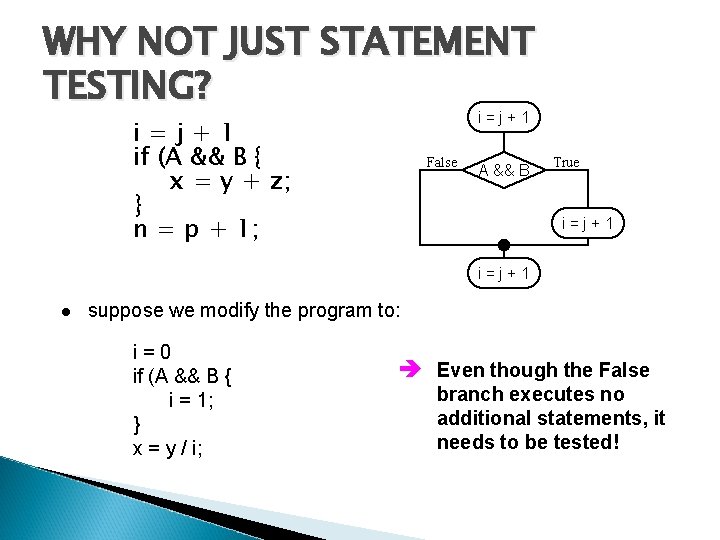

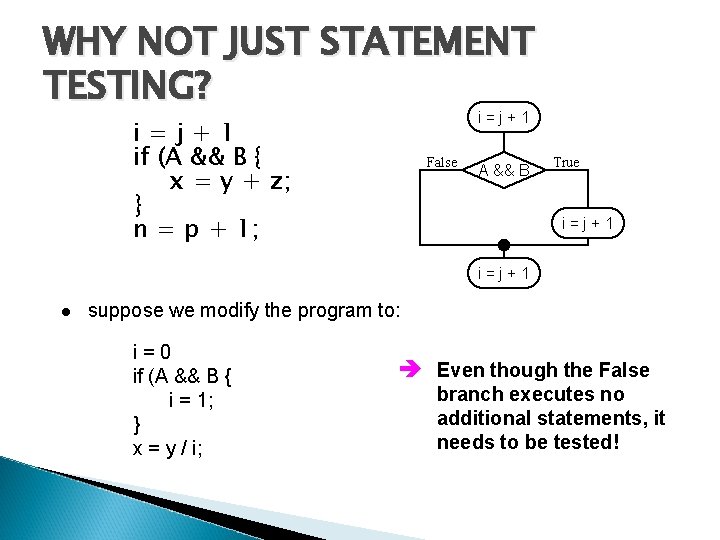

WHY NOT JUST STATEMENT TESTING? i=j+1 if (A && B { x = y + z; } n = p + 1; False A && B True i=j+1 suppose we modify the program to: i=0 if (A && B { i = 1; } x = y / i; è Even though the False branch executes no additional statements, it needs to be tested!

![BASIS PATH TESTING 9 4 2 Goal Goal exercise each independent path in the BASIS PATH TESTING [9. 4. 2] Goal: Goal exercise each independent path in the](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/5bee8f02e6b3fcb2867f72246cd0debc/image-14.jpg)

BASIS PATH TESTING [9. 4. 2] Goal: Goal exercise each independent path in the code at least once 1. From the code, draw a corresponding flow graph. . Sequence If-then-else Do-while Case Do-until

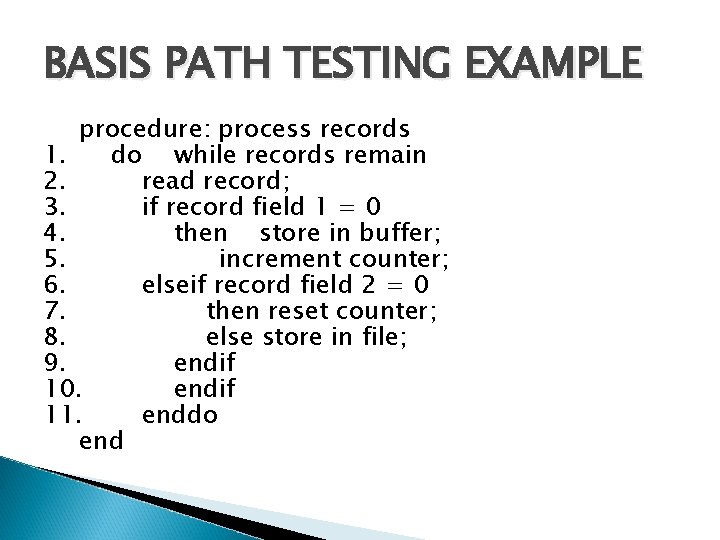

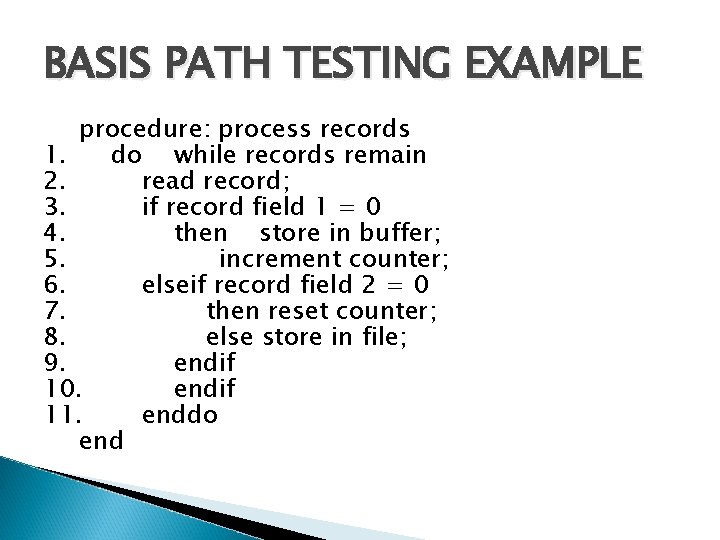

BASIS PATH TESTING EXAMPLE procedure: process records 1. do while records remain 2. read record; 3. if record field 1 = 0 4. then store in buffer; 5. increment counter; 6. elseif record field 2 = 0 7. then reset counter; 8. else store in file; 9. endif 10. endif 11. enddo end

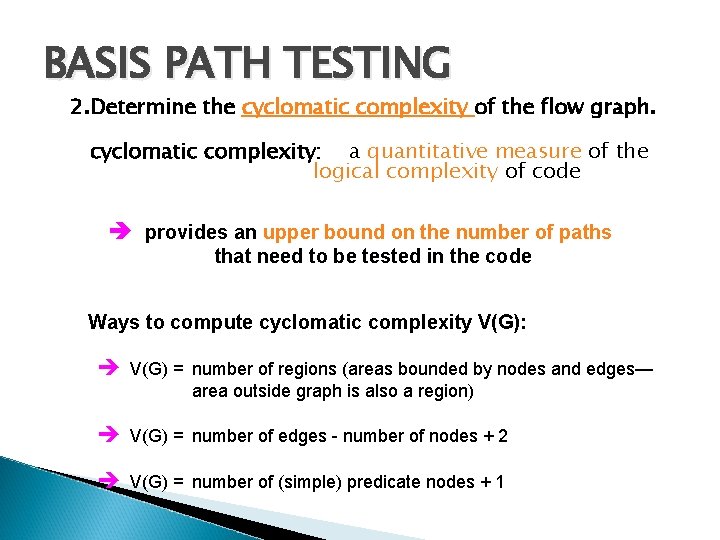

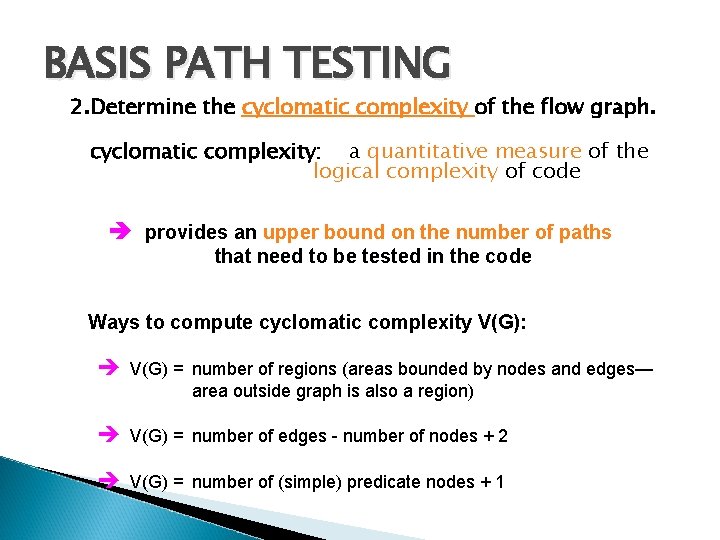

BASIS PATH TESTING 2. Determine the cyclomatic complexity of the flow graph. cyclomatic complexity: a quantitative measure of the logical complexity of code è provides an upper bound on the number of paths that need to be tested in the code Ways to compute cyclomatic complexity V(G): è V(G) = number of regions (areas bounded by nodes and edges— area outside graph is also a region) è V(G) = number of edges - number of nodes + 2 è V(G) = number of (simple) predicate nodes + 1

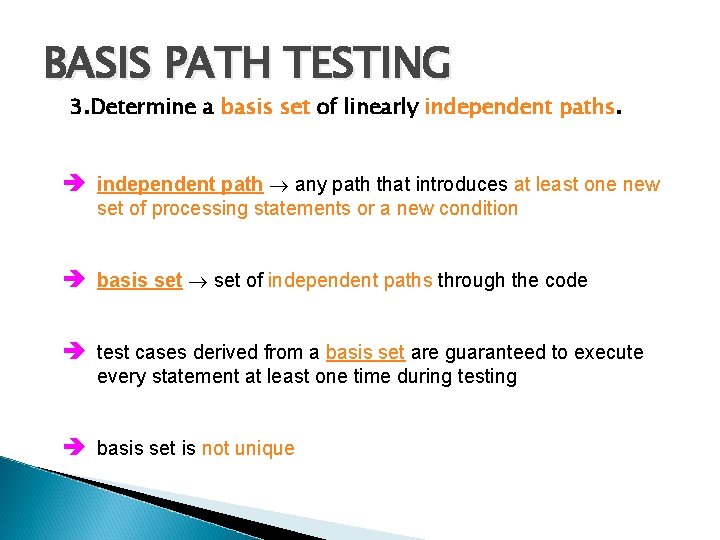

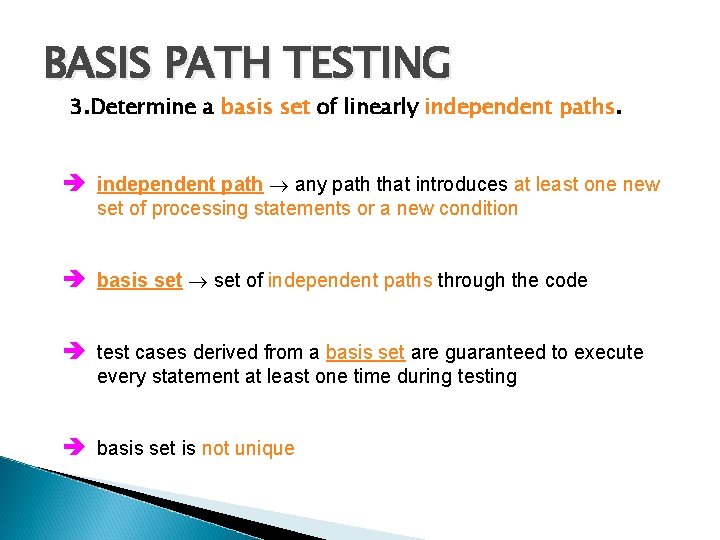

BASIS PATH TESTING 3. Determine a basis set of linearly independent paths. è independent path any path that introduces at least one new set of processing statements or a new condition è basis set of independent paths through the code è test cases derived from a basis set are guaranteed to execute every statement at least one time during testing è basis set is not unique

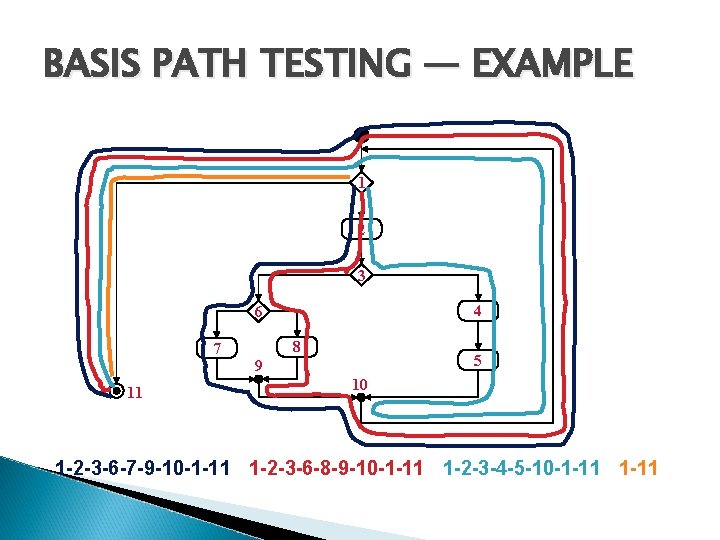

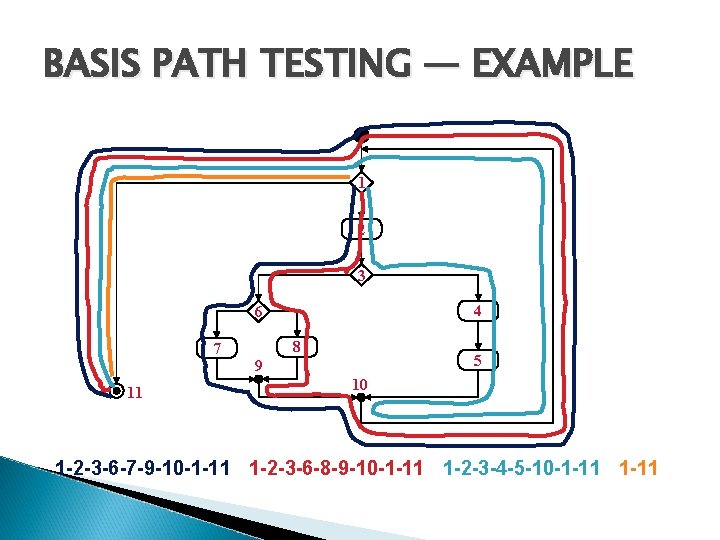

BASIS PATH TESTING — EXAMPLE 1 2 3 4 6 7 11 8 5 9 10 1 -2 -3 -6 -7 -9 -10 -1 -11 1 -2 -3 -6 -8 -9 -10 -1 -11 1 -2 -3 -4 -5 -10 -1 -11

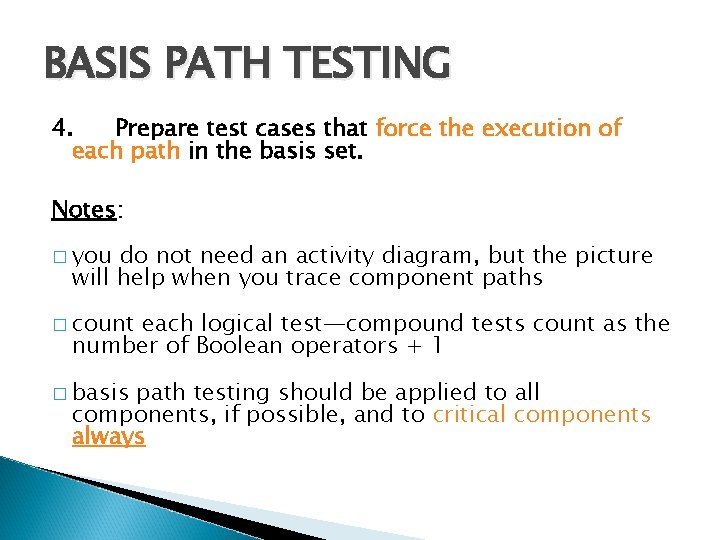

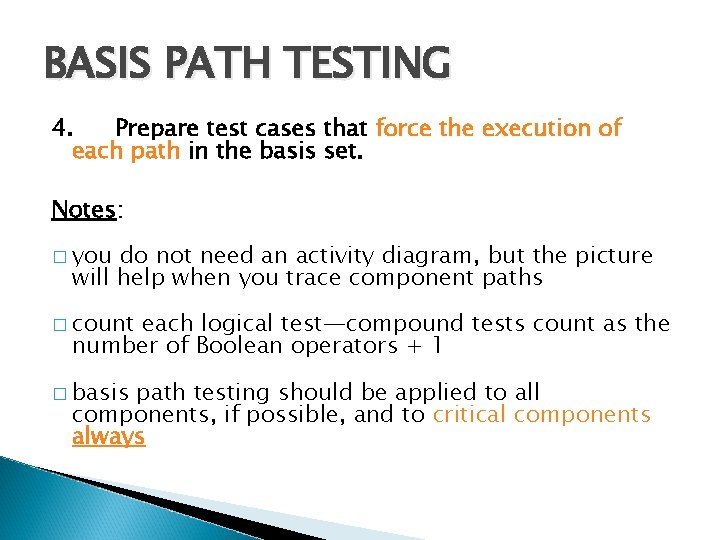

BASIS PATH TESTING 4. Prepare test cases that force the execution of each path in the basis set. Notes: � you do not need an activity diagram, but the picture will help when you trace component paths � count each logical test—compound tests count as the number of Boolean operators + 1 � basis path testing should be applied to all components, if possible, and to critical components always

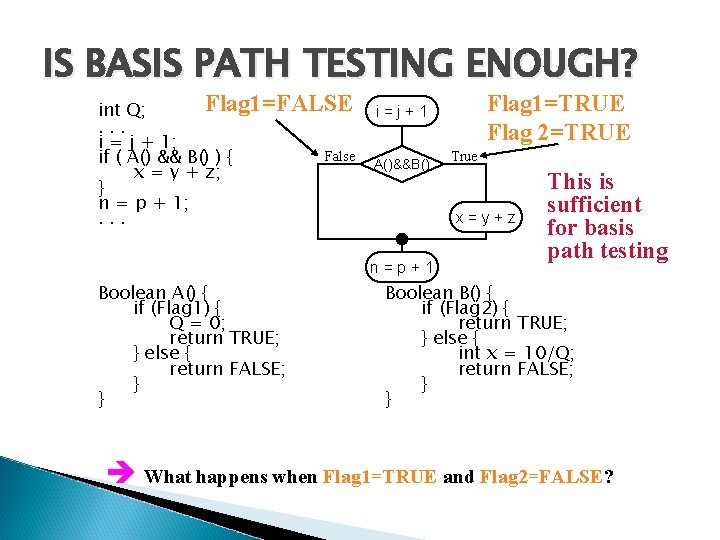

IS BASIS PATH TESTING ENOUGH? Flag 1=FALSE int Q; . . . i = j + 1; False if ( A() && B() ) { x = y + z; } n = p + 1; . . . A()&&B() True x=y+z n=p+1 Boolean A() { if (Flag 1) { Q = 0; return TRUE; } else { return FALSE; } } Flag 1=TRUE Flag 2=TRUE i=j+1 This is sufficient for basis path testing Boolean B() { if (Flag 2) { return TRUE; } else { int x = 10/Q; return FALSE; } } è What happens when Flag 1=TRUE and Flag 2=FALSE?

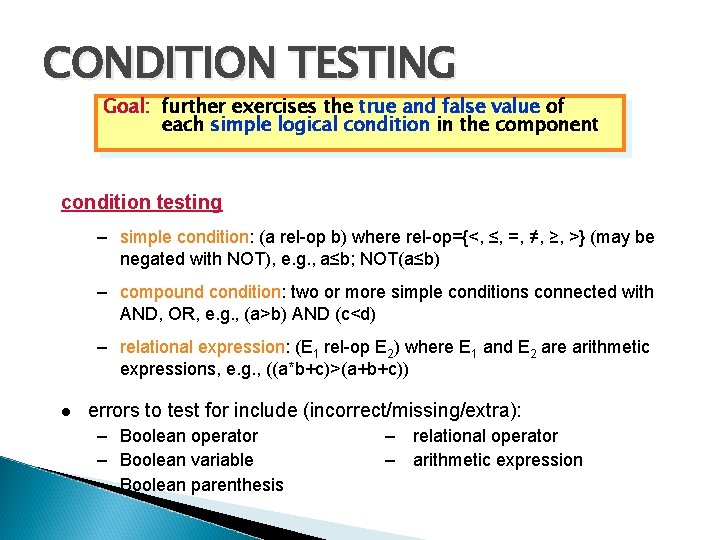

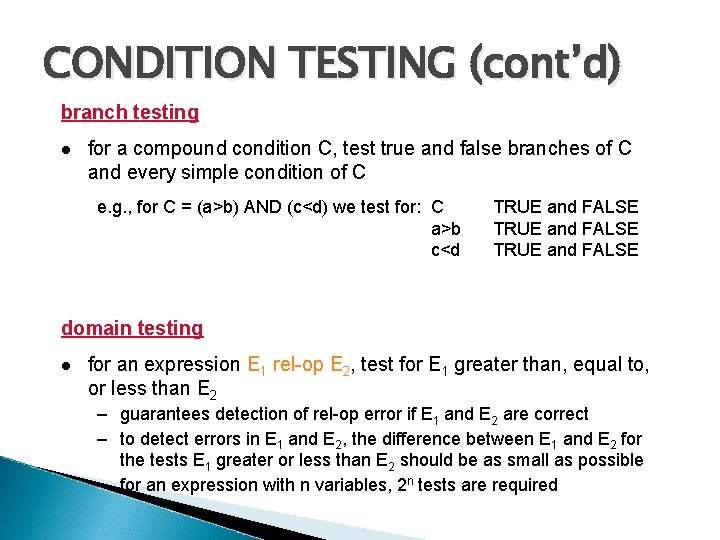

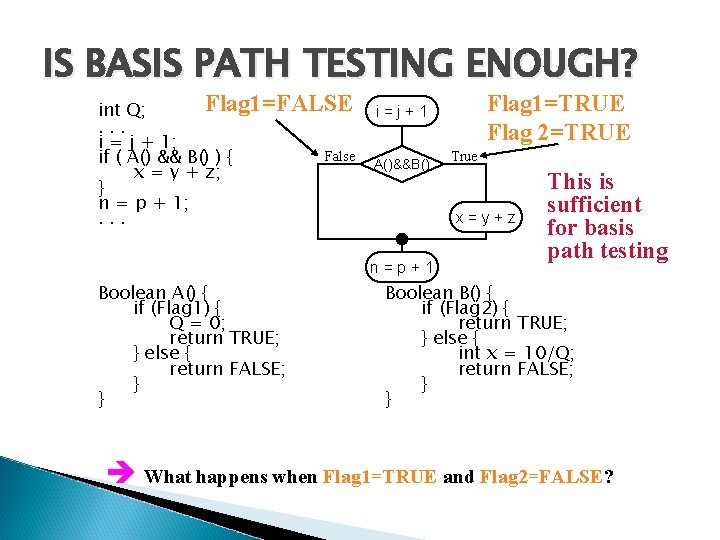

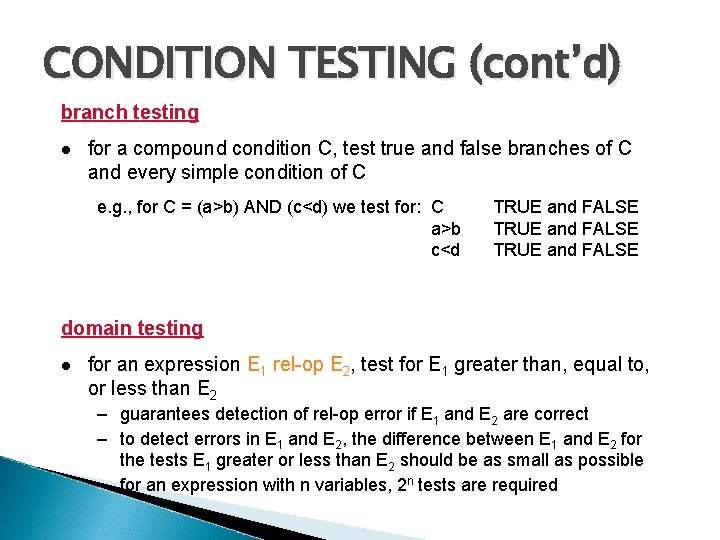

CONDITION TESTING Goal: further exercises the true and false value of each simple logical condition in the component condition testing – simple condition: (a rel-op b) where rel-op={<, ≤, =, ≠, ≥, >} (may be negated with NOT), e. g. , a≤b; NOT(a≤b) – compound condition: two or more simple conditions connected with AND, OR, e. g. , (a>b) AND (c<d) – relational expression: (E 1 rel-op E 2) where E 1 and E 2 are arithmetic expressions, e. g. , ((a*b+c)>(a+b+c)) errors to test for include (incorrect/missing/extra): – Boolean operator – Boolean variable – Boolean parenthesis – relational operator – arithmetic expression

CONDITION TESTING (cont’d) branch testing for a compound condition C, test true and false branches of C and every simple condition of C e. g. , for C = (a>b) AND (c<d) we test for: C a>b c<d TRUE and FALSE domain testing for an expression E 1 rel-op E 2, test for E 1 greater than, equal to, or less than E 2 – guarantees detection of rel-op error if E 1 and E 2 are correct – to detect errors in E 1 and E 2, the difference between E 1 and E 2 for the tests E 1 greater or less than E 2 should be as small as possible – for an expression with n variables, 2 n tests are required

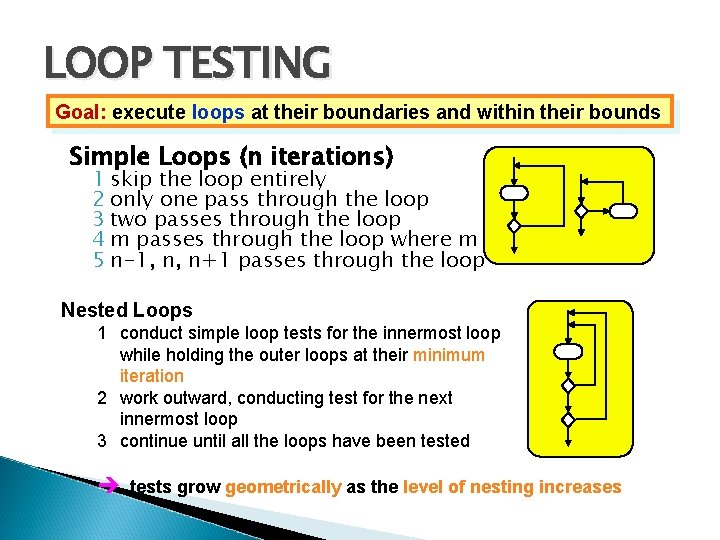

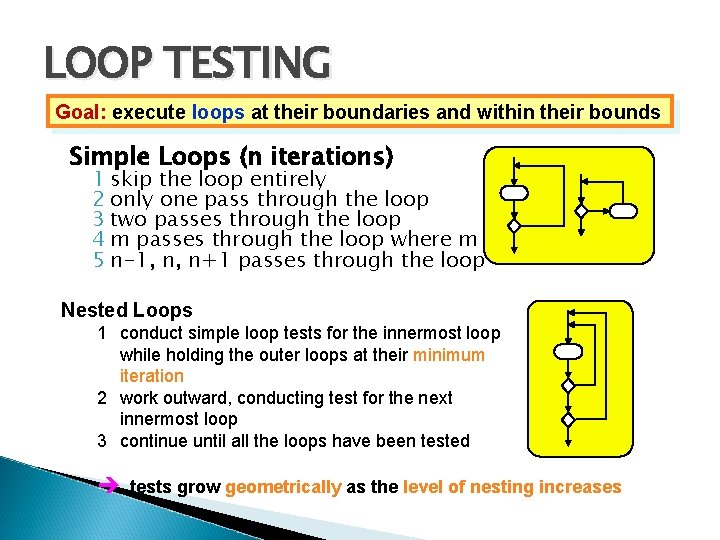

LOOP TESTING Goal: execute loops at their boundaries and within their bounds Simple Loops (n iterations) 1 skip the loop entirely 2 only one pass through the loop 3 two passes through the loop 4 m passes through the loop where m < n 5 n-1, n, n+1 passes through the loop Nested Loops 1 conduct simple loop tests for the innermost loop while holding the outer loops at their minimum iteration 2 work outward, conducting test for the next innermost loop 3 continue until all the loops have been tested è tests grow geometrically as the level of nesting increases

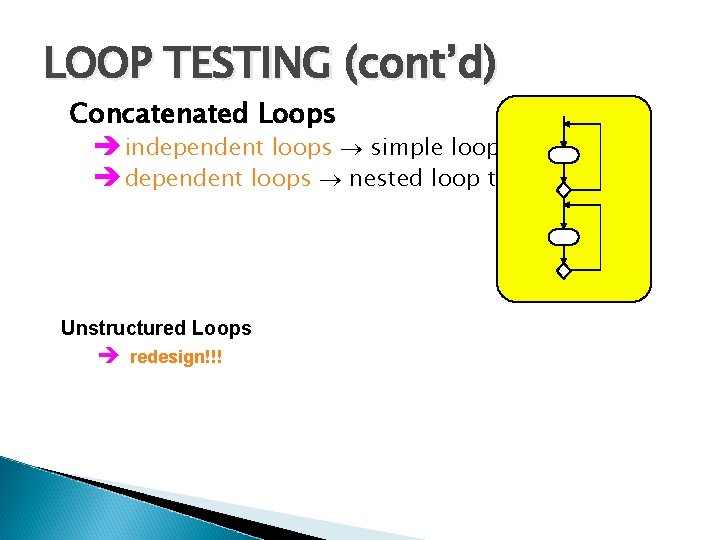

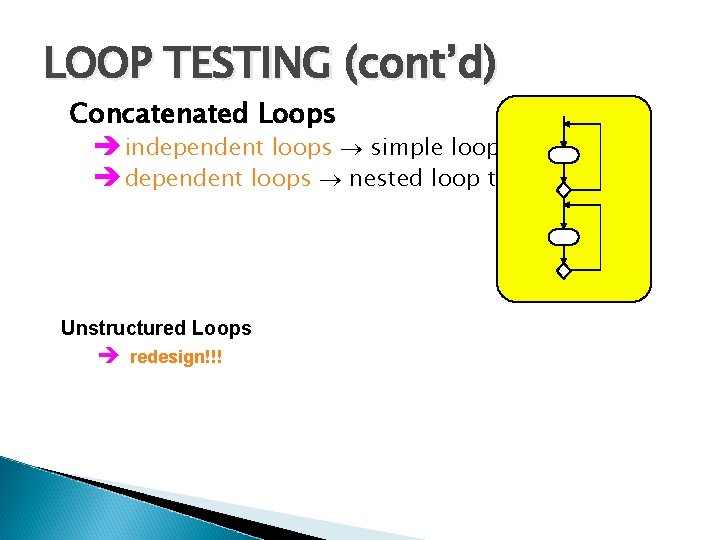

LOOP TESTING (cont’d) Concatenated Loops è independent loops simple loop testing è dependent loops nested loop testing Unstructured Loops è redesign!!!

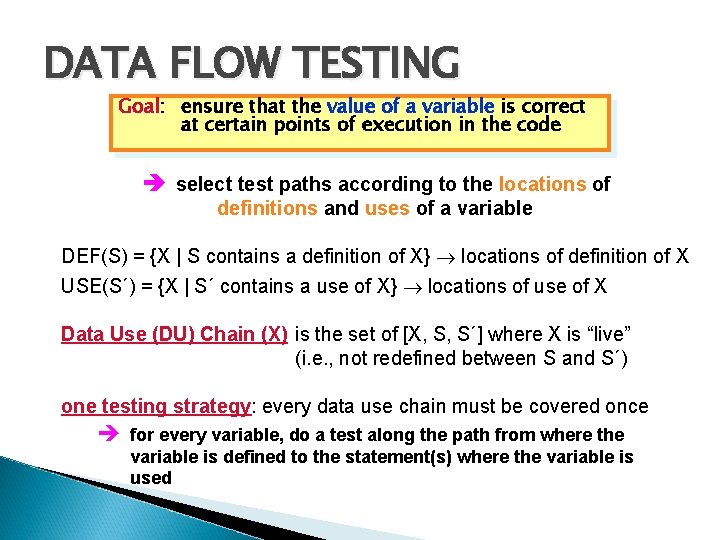

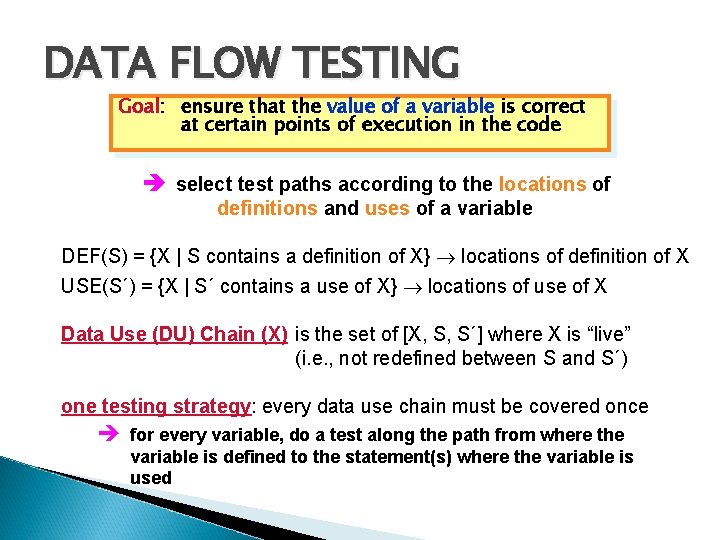

DATA FLOW TESTING Goal: Goal ensure that the value of a variable is correct at certain points of execution in the code è select test paths according to the locations of definitions and uses of a variable DEF(S) = {X | S contains a definition of X} locations of definition of X USE(S´) = {X | S´ contains a use of X} locations of use of X Data Use (DU) Chain (X) is the set of [X, S, S´] where X is “live” (i. e. , not redefined between S and S´) one testing strategy: every data use chain must be covered once è for every variable, do a test along the path from where the variable is defined to the statement(s) where the variable is used

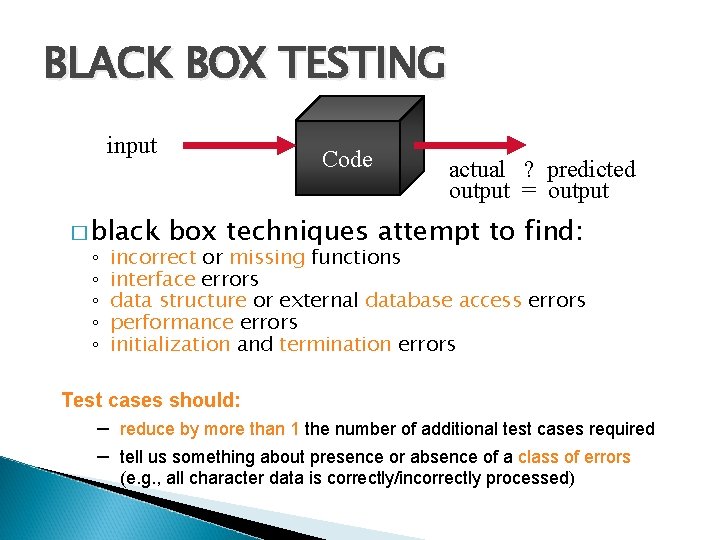

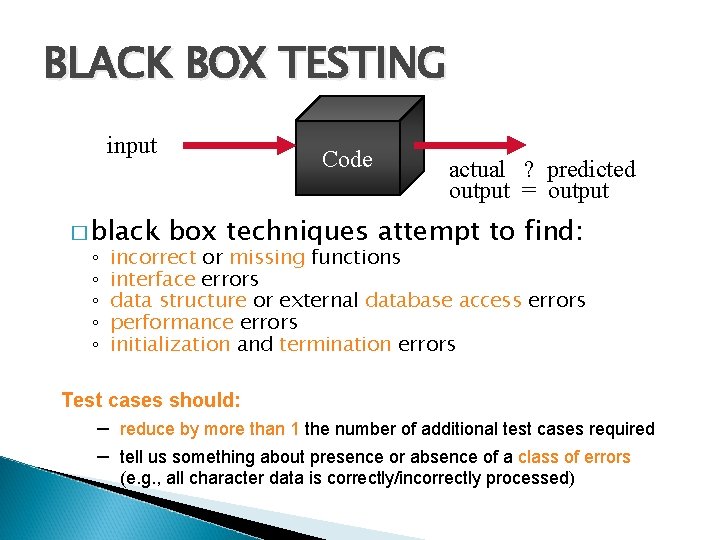

BLACK BOX TESTING input � black ◦ ◦ ◦ Code actual ? predicted output = output box techniques attempt to find: incorrect or missing functions interface errors data structure or external database access errors performance errors initialization and termination errors Test cases should: – reduce by more than 1 the number of additional test cases required – tell us something about presence or absence of a class of errors (e. g. , all character data is correctly/incorrectly processed)

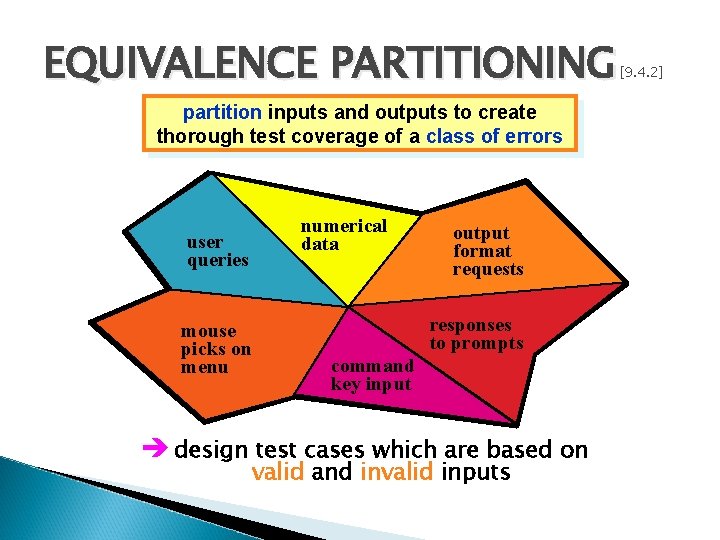

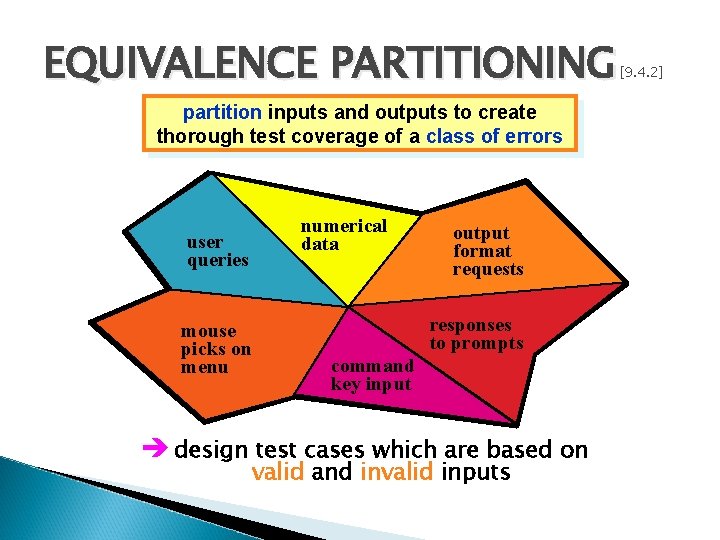

EQUIVALENCE PARTITIONING partition inputs and outputs to create thorough test coverage of a class of errors user queries numerical data output format requests all possible input values mouse picks on menu responses to prompts command key input è design test cases which are based on valid and invalid inputs [9. 4. 2]

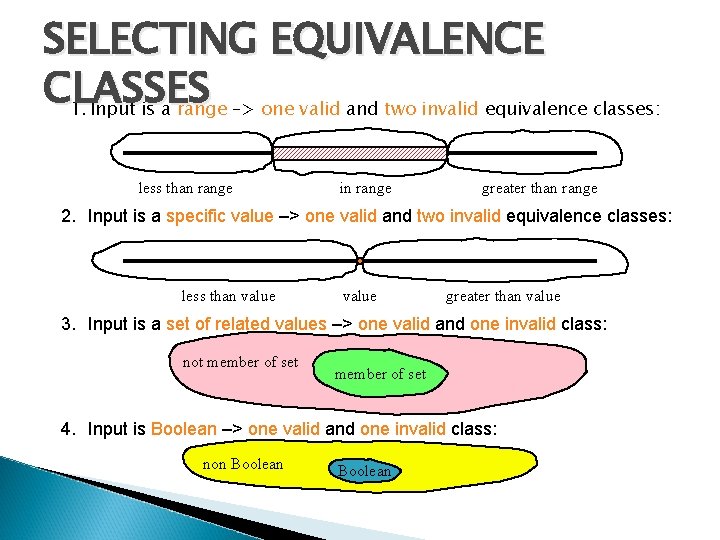

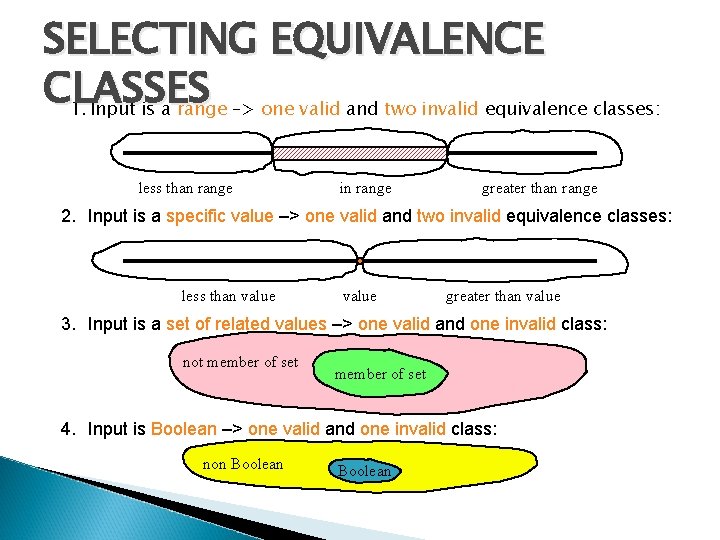

SELECTING EQUIVALENCE CLASSES 1. Input is a range –> one valid and two invalid equivalence classes: less than range in range greater than range 2. Input is a specific value –> one valid and two invalid equivalence classes: less than value greater than value 3. Input is a set of related values –> one valid and one invalid class: not member of set 4. Input is Boolean –> one valid and one invalid class: non Boolean

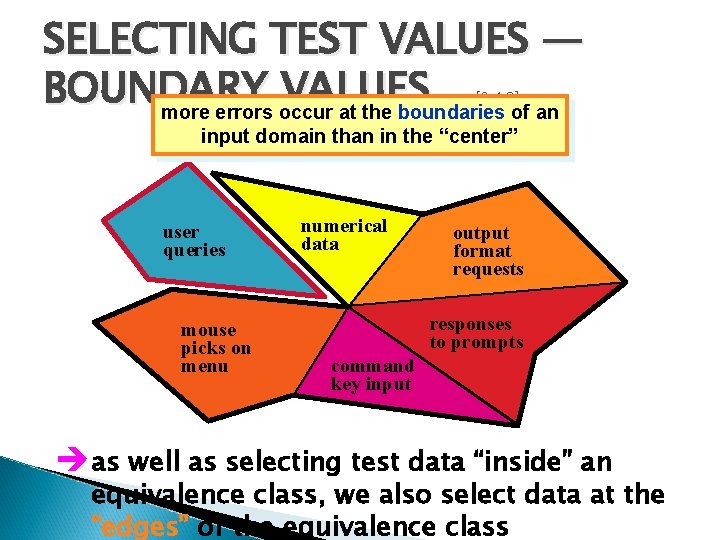

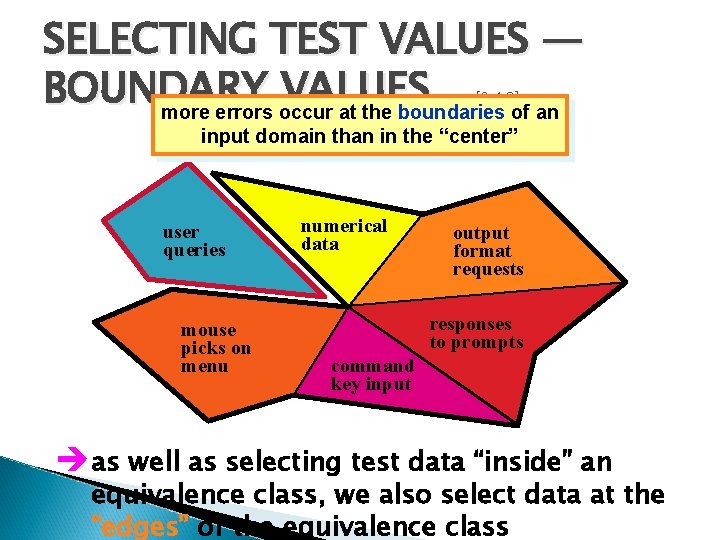

SELECTING TEST VALUES — BOUNDARY VALUES more errors occur at the boundaries of an [9. 4. 2] input domain than in the “center” user queries mouse picks on menu numerical data output format requests responses to prompts command key input èas well as selecting test data “inside” an equivalence class, we also select data at the “edges” of the equivalence class

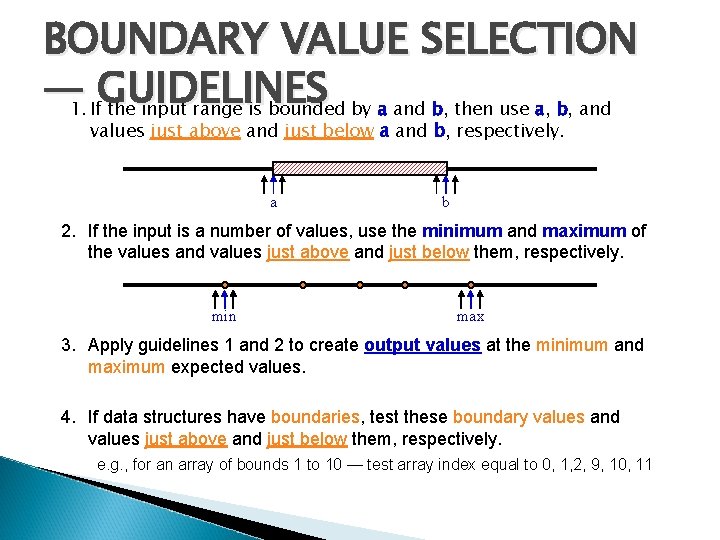

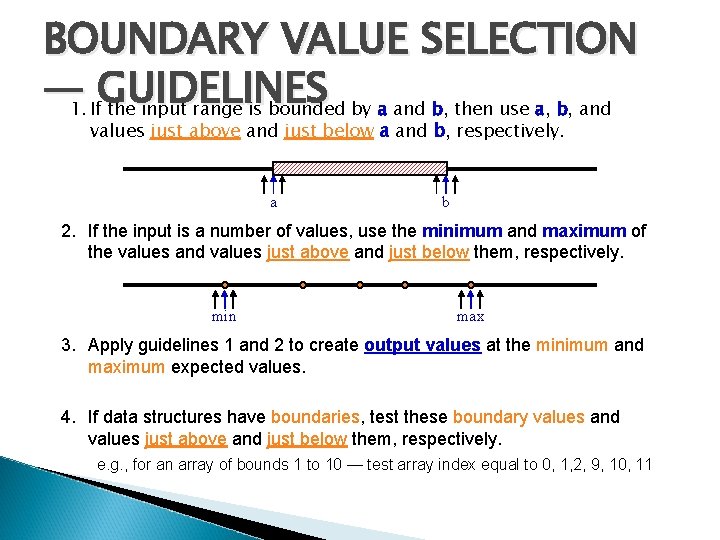

BOUNDARY VALUE SELECTION — 1. If. GUIDELINES the input range is bounded by a and b, then use a, b, and values just above and just below a and b, respectively. a b 2. If the input is a number of values, use the minimum and maximum of the values and values just above and just below them, respectively. min max 3. Apply guidelines 1 and 2 to create output values at the minimum and maximum expected values. 4. If data structures have boundaries, test these boundary values and values just above and just below them, respectively. e. g. , for an array of bounds 1 to 10 — test array index equal to 0, 1, 2, 9, 10, 11

![OTHER BLACK BOX TECHNIQUES Error Guessing 9 4 2 use application domain experience OTHER BLACK BOX TECHNIQUES Error Guessing [9. 4. 2] ◦ use application domain experience](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/5bee8f02e6b3fcb2867f72246cd0debc/image-31.jpg)

OTHER BLACK BOX TECHNIQUES Error Guessing [9. 4. 2] ◦ use application domain experience or knowledge to select test values Cause-Effect Graphing 1. causes (input conditions) and effects (actions) are identified for a subsystem 2. a cause-effect graph is developed 3. the graph is converted to a decision table 4. decision table rules are converted into test cases Comparison Testing – when reliability is absolutely critical, write several versions of the software — perhaps to be used as backups – run same test data on all versions; cross-check results for consistency Caution: if the error is from a bad specification and all versions are built from the same specification, then the same bug will be present in all copies!

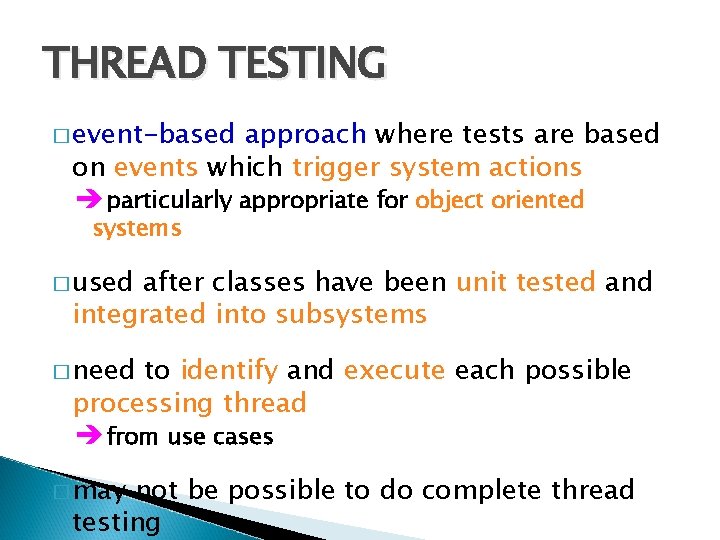

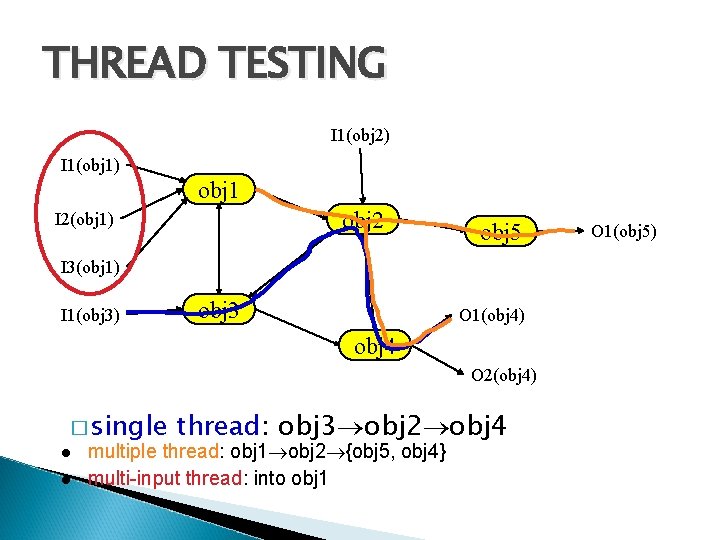

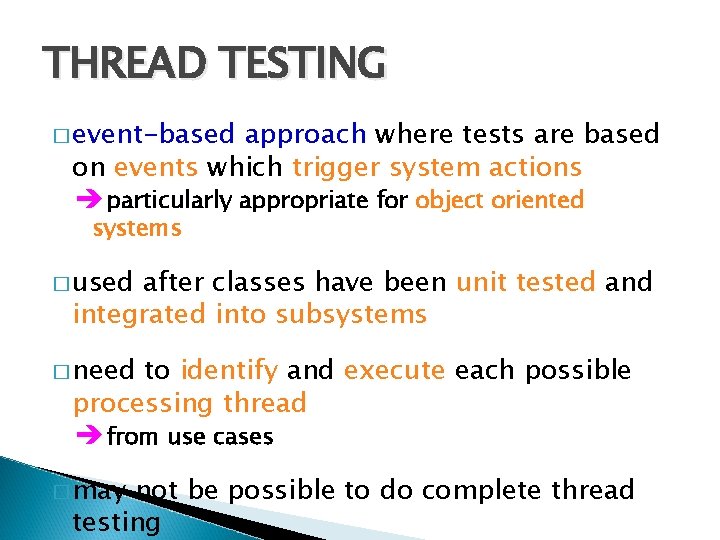

THREAD TESTING � event-based approach where tests are based on events which trigger system actions è particularly appropriate for object oriented systems � used after classes have been unit tested and integrated into subsystems � need to identify and execute each possible processing thread è from use cases � may not be possible to do complete thread testing

THREAD TESTING I 1(obj 2) I 1(obj 1) obj 1 obj 2 I 2(obj 1) obj 5 I 3(obj 1) I 1(obj 3) obj 3 O 1(obj 4) obj 4 O 2(obj 4) � single thread: obj 3 obj 2 obj 4 multiple thread: obj 1 obj 2 {obj 5, obj 4} multi-input thread: into obj 1 O 1(obj 5)

![STATEBASED TESTING focuses 9 4 2 on comparing the resulting state of a STATE-BASED TESTING � focuses [9. 4. 2] on comparing the resulting state of a](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/5bee8f02e6b3fcb2867f72246cd0debc/image-34.jpg)

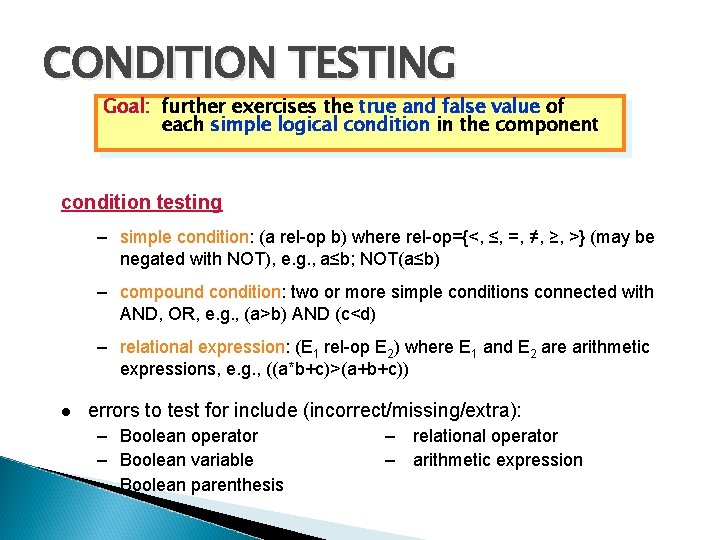

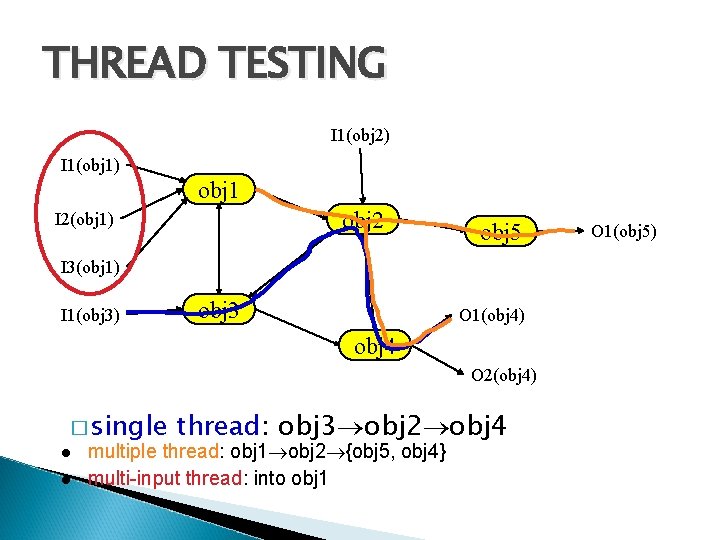

STATE-BASED TESTING � focuses [9. 4. 2] on comparing the resulting state of a class with the expected state è derive test cases using statechart diagram for a class � derive a representative set of “stimuli” for each transition � check the attributes of the class after applying a “stimuli” to determine of the specified state has been reached è first need to put the class in the desired state before applying the “stimuli”

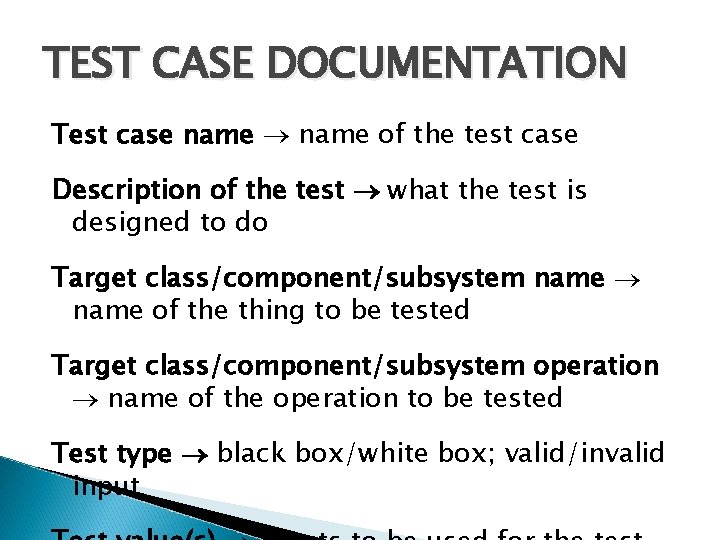

TEST CASE DOCUMENTATION Test case name of the test case Description of the test what the test is designed to do Target class/component/subsystem name of the thing to be tested Target class/component/subsystem operation name of the operation to be tested Test type black box/white box; valid/invalid input

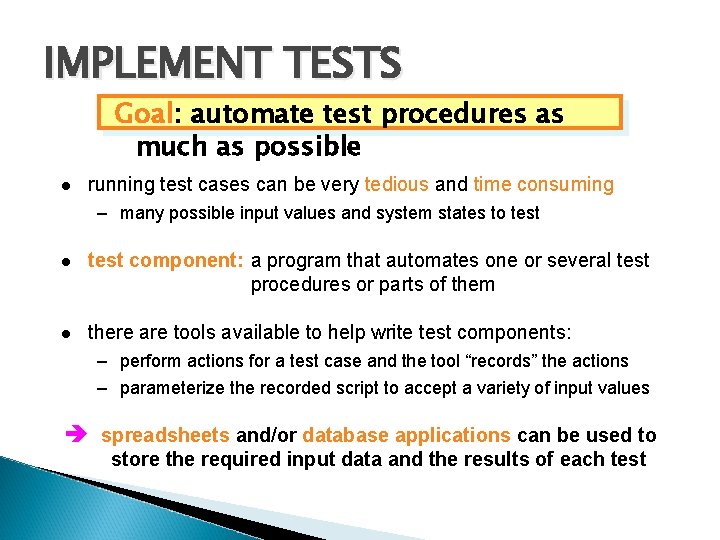

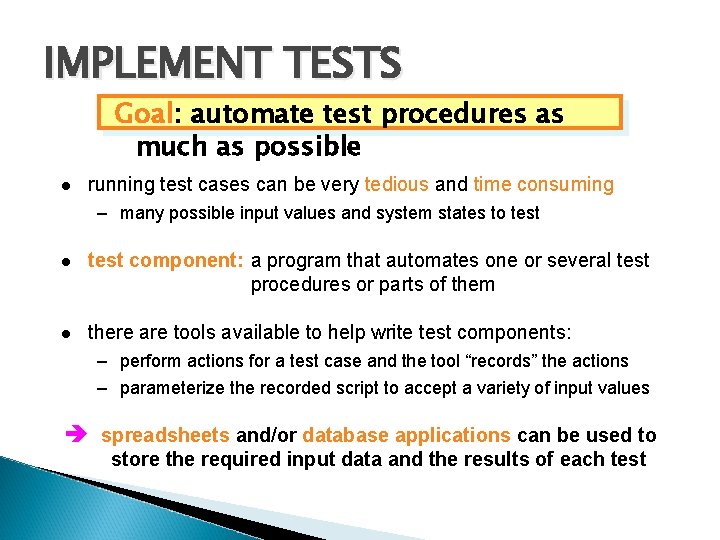

IMPLEMENT TESTS Goal: Goal automate test procedures as much as possible running test cases can be very tedious and time consuming – many possible input values and system states to test component: a program that automates one or several test procedures or parts of them there are tools available to help write test components: – perform actions for a test case and the tool “records” the actions – parameterize the recorded script to accept a variety of input values è spreadsheets and/or database applications can be used to store the required input data and the results of each test

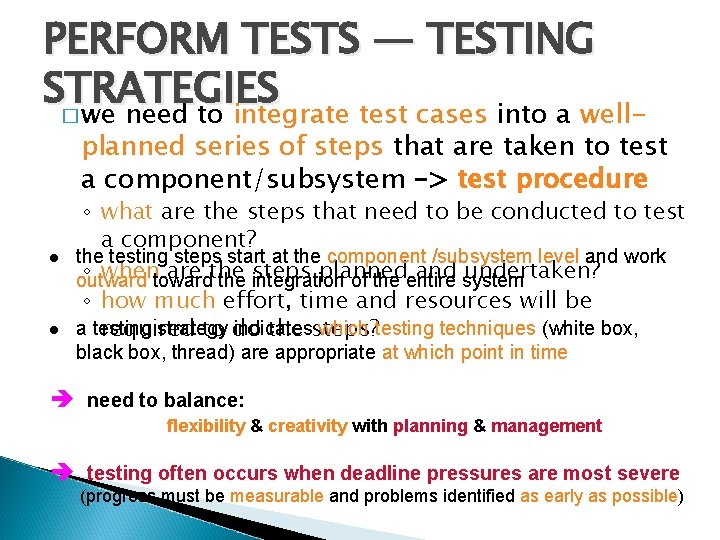

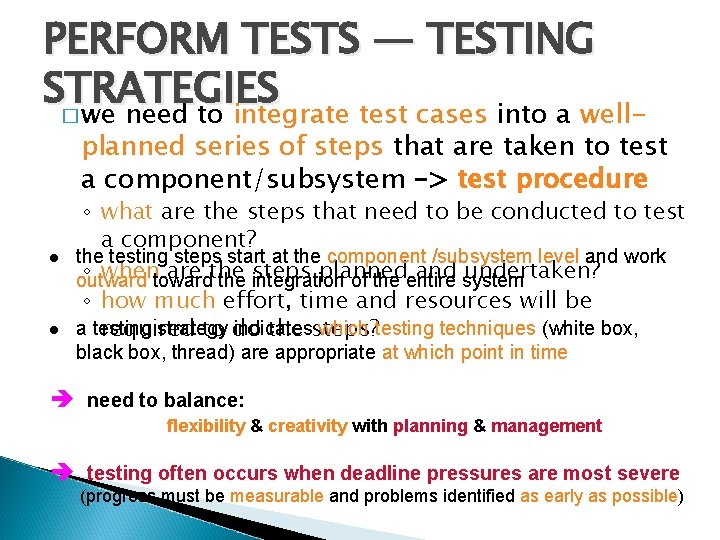

PERFORM TESTS — TESTING STRATEGIES � we need to integrate test cases into a well- planned series of steps that are taken to test a component/subsystem –> test procedure ◦ what are the steps that need to be conducted to test a component? the testing steps start at the component /subsystem level and work ◦ whentoward are the steps planned and system undertaken? outward the integration of the entire ◦ how much effort, time and resources will be a testing strategy indicates which testing techniques (white box, required to do the steps? black box, thread) are appropriate at which point in time è need to balance: flexibility & creativity with planning & management è testing often occurs when deadline pressures are most severe (progress must be measurable and problems identified as early as possible)

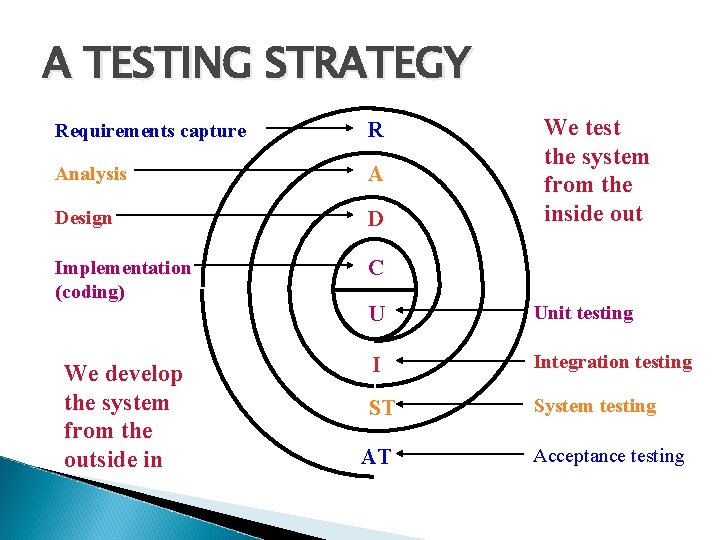

A TESTING STRATEGY We test the system from the inside out Requirements capture R Analysis A Design D Implementation (coding) C U Unit testing We develop the system from the outside in I Integration testing ST System testing AT Acceptance testing

![UNIT TESTING Component 9 4 2 interface local data structures boundary conditions independent paths UNIT TESTING Component [9. 4. 2] interface local data structures boundary conditions independent paths](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/5bee8f02e6b3fcb2867f72246cd0debc/image-39.jpg)

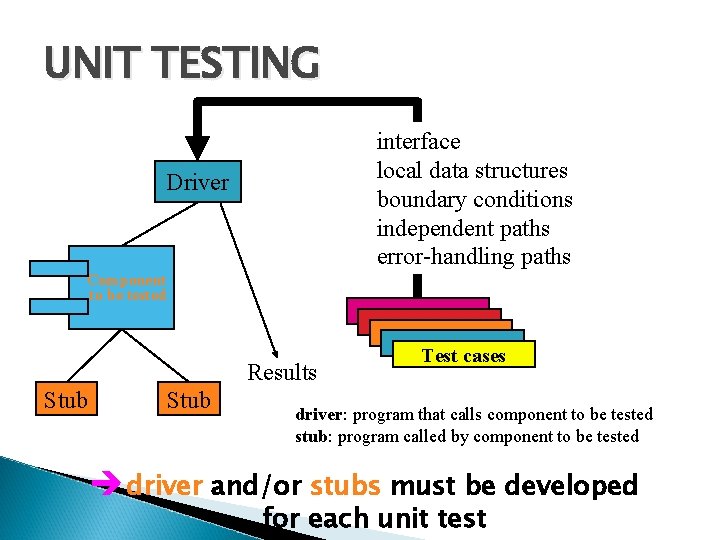

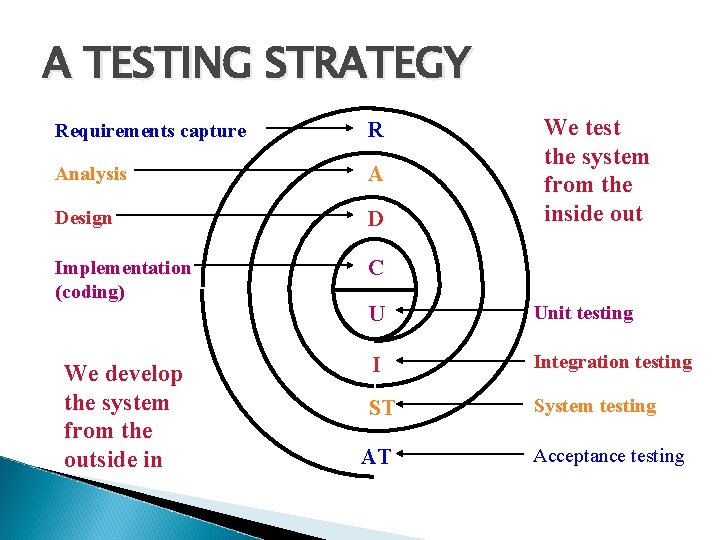

UNIT TESTING Component [9. 4. 2] interface local data structures boundary conditions independent paths error-handling paths Test cases è emphasis is on White Box techniques

UNIT TESTING interface local data structures boundary conditions independent paths error-handling paths Driver Component to be tested Results Stub Test cases driver: program that calls component to be tested stub: program called by component to be tested è driver and/or stubs must be developed for each unit test

![INTEGRATION TESTING 9 4 3 è If components all work individually why more be INTEGRATION TESTING [9. 4. 3] è If components all work individually, why more be](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/5bee8f02e6b3fcb2867f72246cd0debc/image-41.jpg)

INTEGRATION TESTING [9. 4. 3] è If components all work individually, why more be testing? è Interface errors cannot uncovered by unit testing integration approaches: Incremental construction strategy Big Bang!! versus Incremental “builds” Regression testing

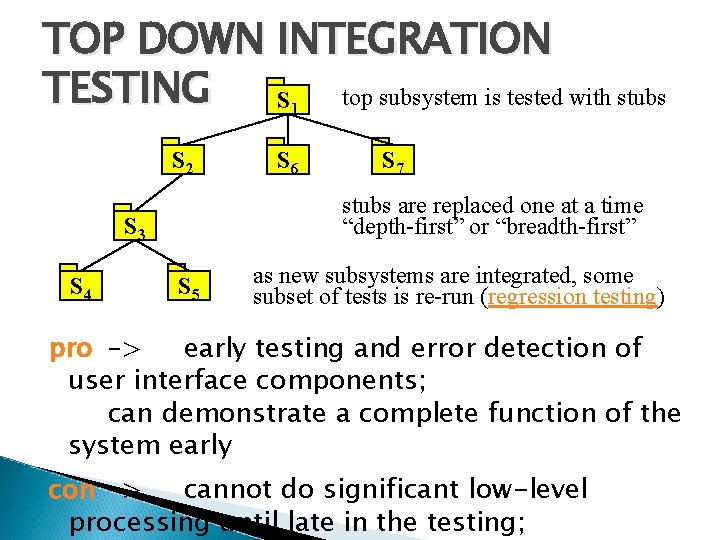

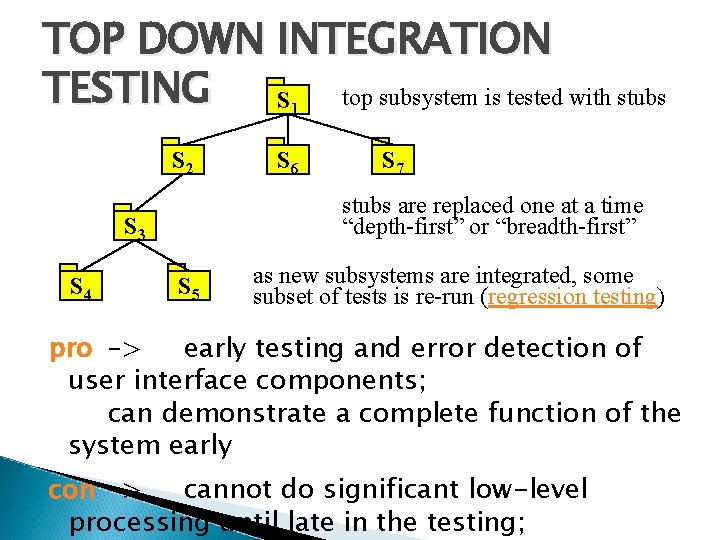

TOP DOWN INTEGRATION TESTING top subsystem is tested with stubs S 1 S 2 S 7 stubs are replaced one at a time “depth-first” or “breadth-first” S 3 S 4 S 6 S 5 as new subsystems are integrated, some subset of tests is re-run (regression testing) pro –> early testing and error detection of user interface components; can demonstrate a complete function of the system early con –> cannot do significant low-level processing until late in the testing;

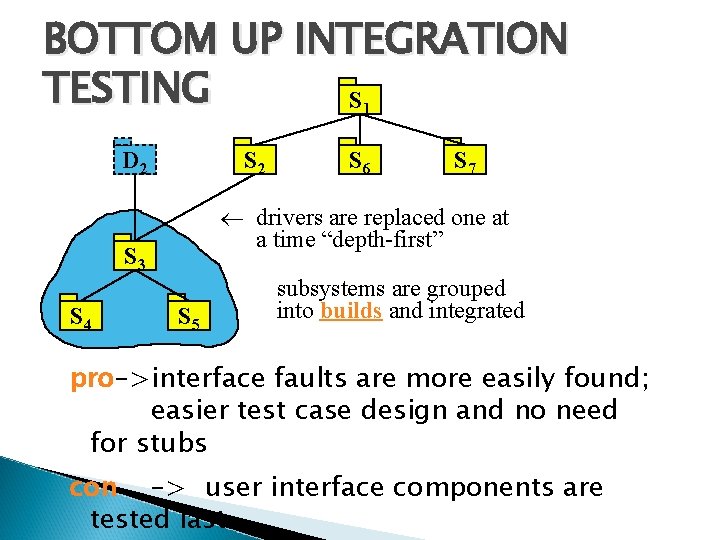

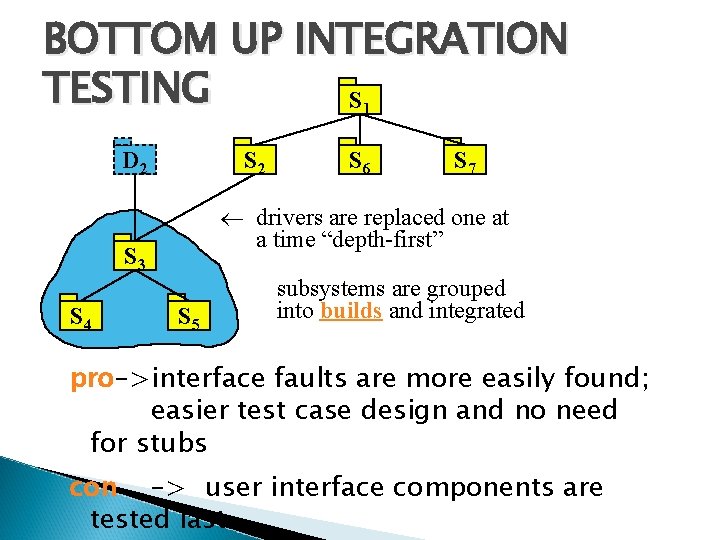

BOTTOM UP INTEGRATION TESTING S 1 D 2 S 7 drivers are replaced one at a time “depth-first” S 3 S 4 S 6 S 5 subsystems are grouped into builds and integrated pro–>interface faults are more easily found; easier test case design and no need for stubs con –> user interface components are tested last

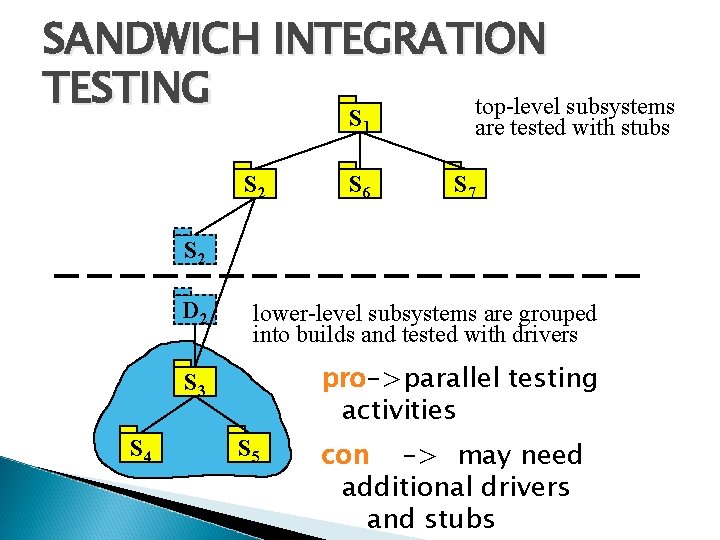

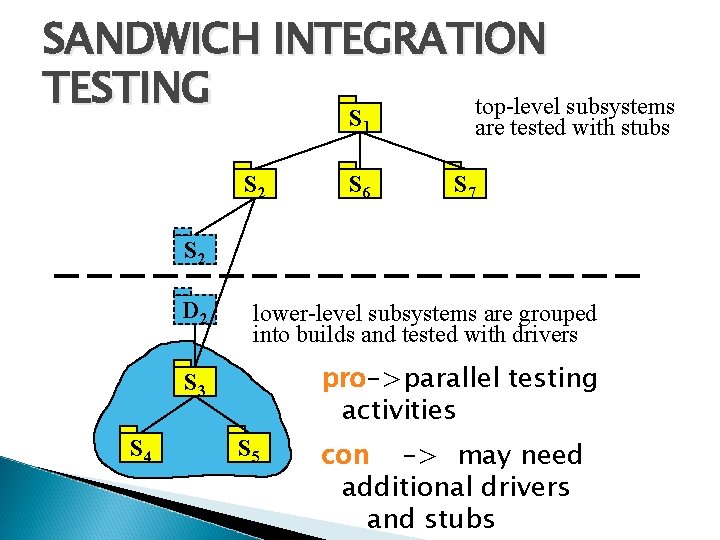

SANDWICH INTEGRATION TESTING top-level subsystems S 1 S 2 S 6 are tested with stubs S 7 S 2 S 4 D 2 lower-level subsystems are grouped into builds and tested with drivers S 3 pro–>parallel testing activities S 5 con –> may need additional drivers and stubs

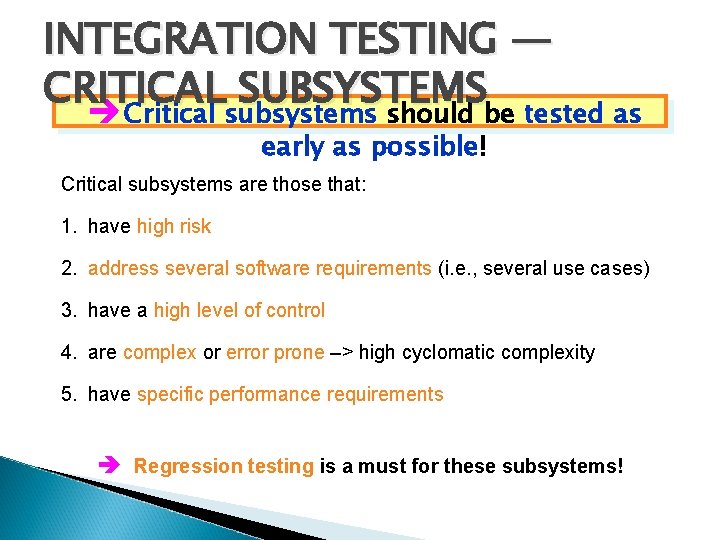

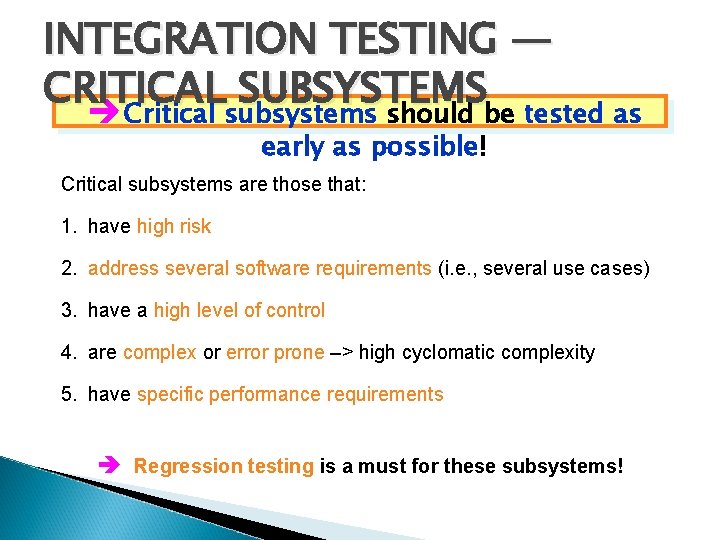

INTEGRATION TESTING — CRITICAL SUBSYSTEMS è Critical subsystems should be tested as early as possible! Critical subsystems are those that: 1. have high risk 2. address several software requirements (i. e. , several use cases) 3. have a high level of control 4. are complex or error prone –> high cyclomatic complexity 5. have specific performance requirements è Regression testing is a must for these subsystems!

![SYSTEM TESTING 9 4 4 We need to test the entire system to be SYSTEM TESTING [9. 4. 4] We need to test the entire system to be](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/5bee8f02e6b3fcb2867f72246cd0debc/image-46.jpg)

SYSTEM TESTING [9. 4. 4] We need to test the entire system to be sure the system functions properly when some specific types of system tests: integrated Functional –> developers verify that all user functions work as specified in the system requirements specification Performance –> developers verify that the nonfunctional requirements are met Pilot –> a selected group of end users verifies common functionality in the target environment Acceptance –> customer verifies usability, functional and nonfunctional requirements against system requirements specification Installation –> customer verifies usability, functional and nonfunctional requirements in real use

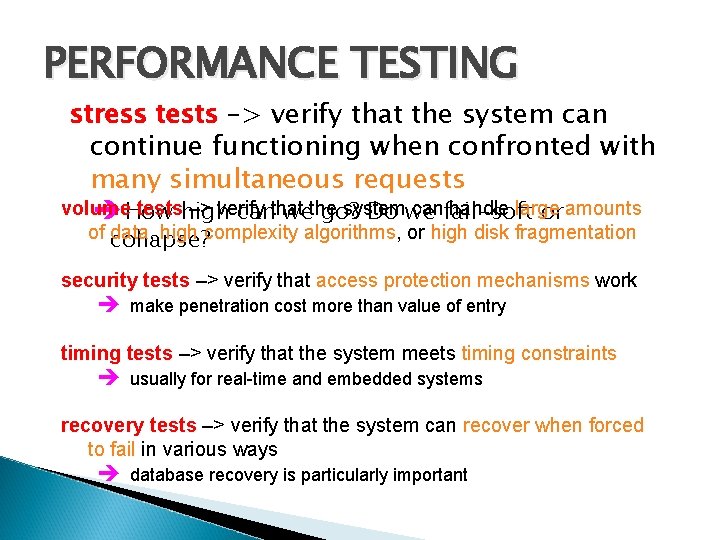

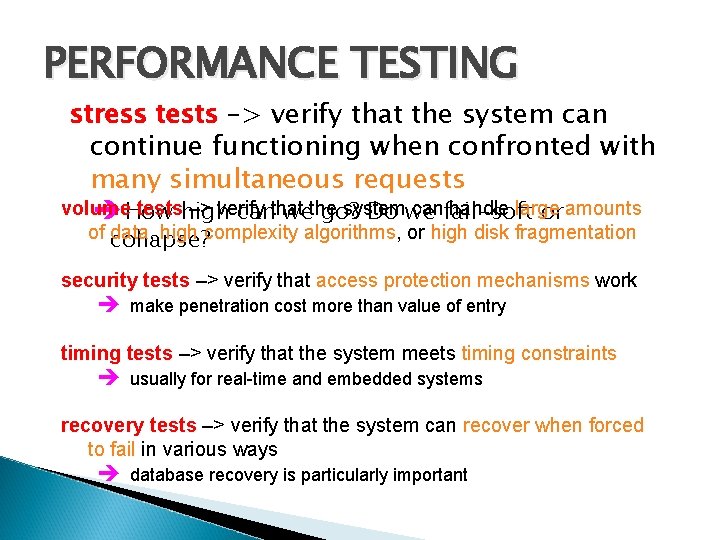

PERFORMANCE TESTING stress tests –> verify that the system can continue functioning when confronted with many simultaneous requests volume testshigh –> verify system canfail-soft handle large è How canthat wethe go? Do we or amounts of collapse? data, high complexity algorithms, or high disk fragmentation security tests –> verify that access protection mechanisms work è make penetration cost more than value of entry timing tests –> verify that the system meets timing constraints è usually for real-time and embedded systems recovery tests –> verify that the system can recover when forced to fail in various ways è database recovery is particularly important

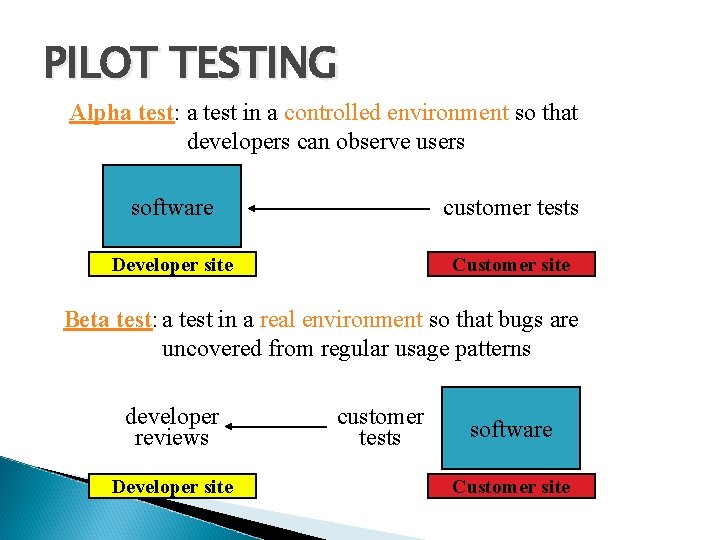

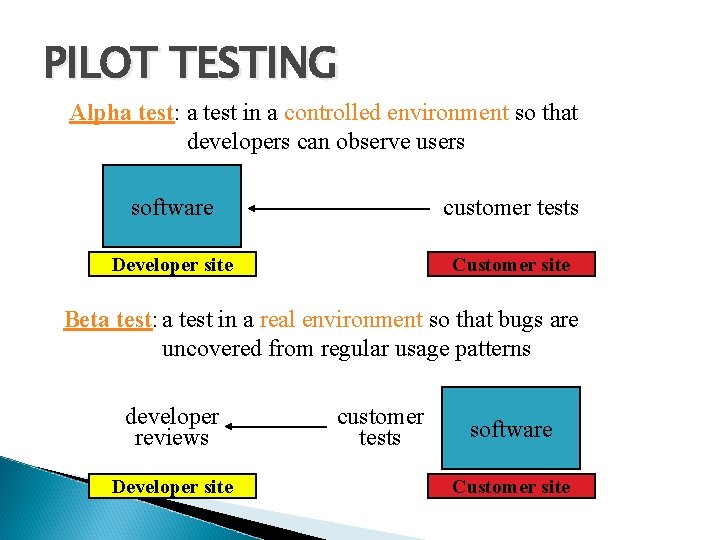

PILOT TESTING Alpha test: a test in a controlled environment so that developers can observe users software customer tests Developer site Customer site Beta test: a test in a real environment so that bugs are uncovered from regular usage patterns developer reviews Developer site customer tests software Customer site

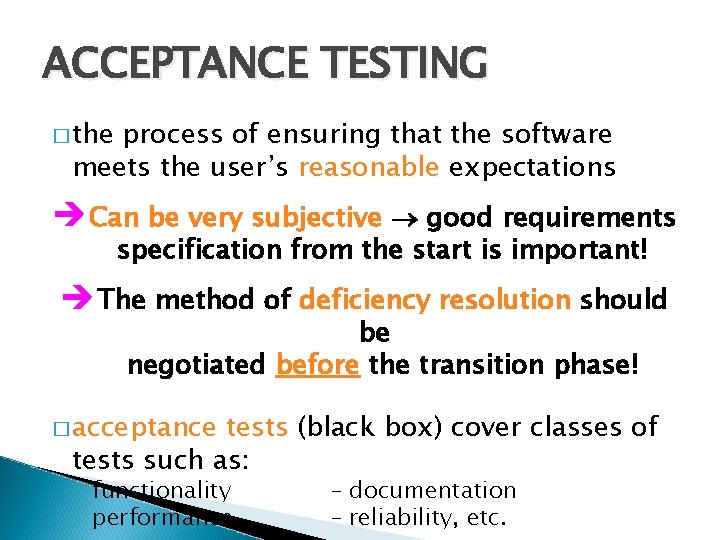

ACCEPTANCE TESTING � the process of ensuring that the software meets the user’s reasonable expectations è Can be very subjective good requirements specification from the start is important! è The method of deficiency resolution should be negotiated before the transition phase! � acceptance tests (black box) cover classes of tests such as: ◦ functionality ◦ performance – documentation – reliability, etc.

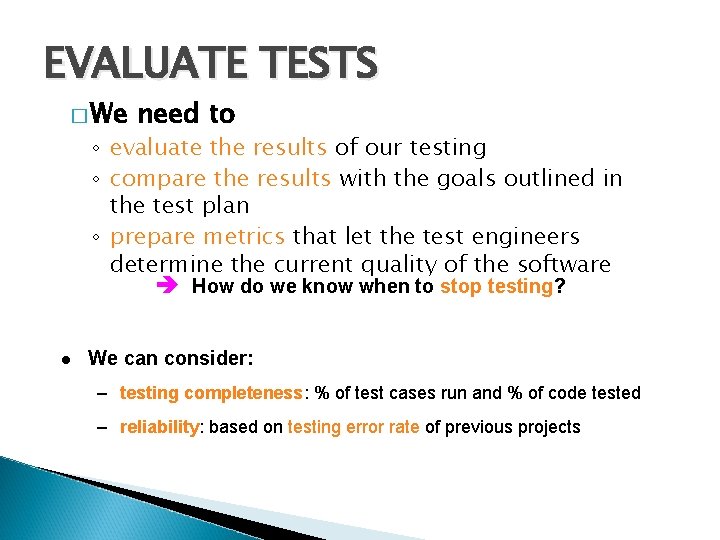

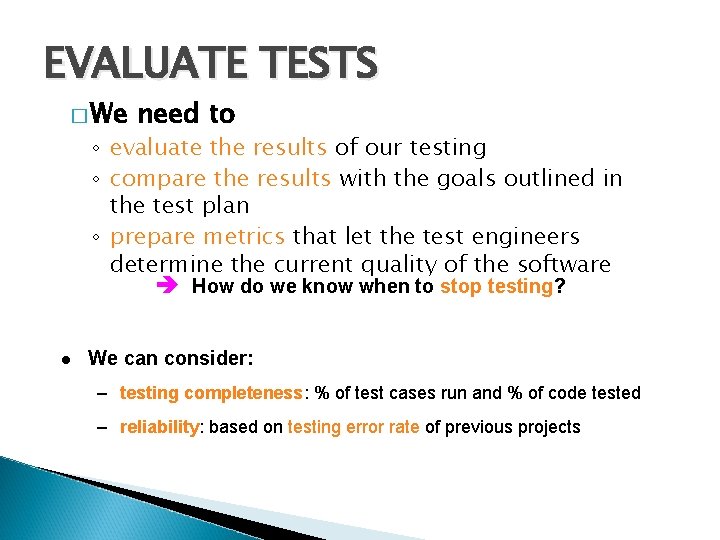

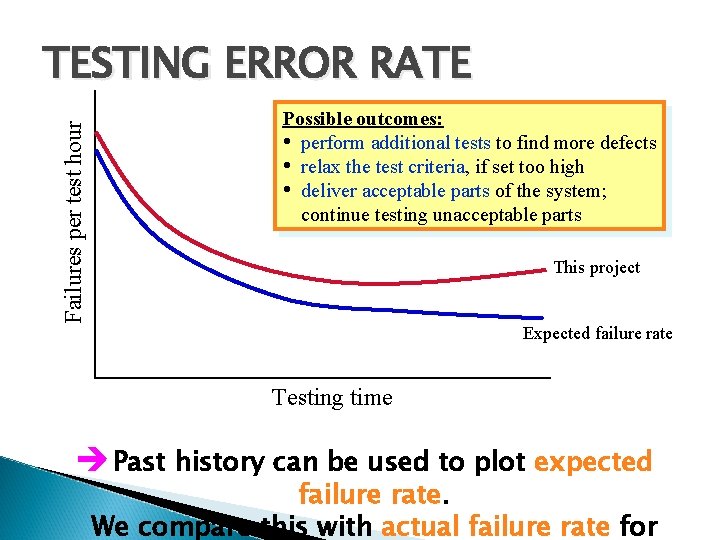

EVALUATE TESTS � We need to ◦ evaluate the results of our testing ◦ compare the results with the goals outlined in the test plan ◦ prepare metrics that let the test engineers determine the current quality of the software è How do we know when to stop testing? We can consider: – testing completeness: % of test cases run and % of code tested – reliability: based on testing error rate of previous projects

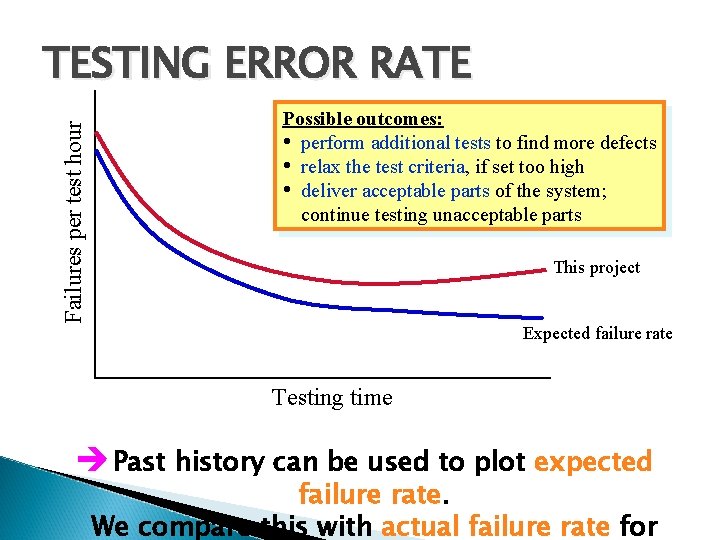

Failures per test hour TESTING ERROR RATE Possible outcomes: • perform additional tests to find more defects • relax the test criteria, if set too high • deliver acceptable parts of the system; continue testing unacceptable parts This project Expected failure rate Testing time è Past history can be used to plot expected failure rate. We compare this with actual failure rate for

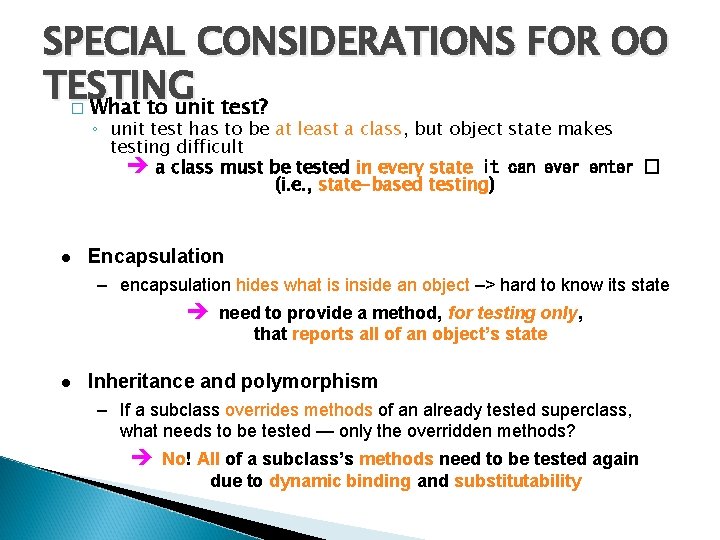

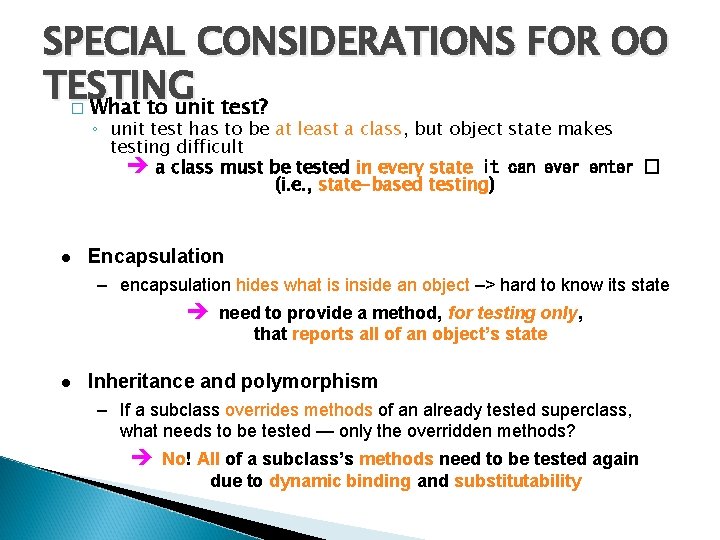

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS FOR OO TESTING What to unit test? � ◦ unit test has to be at least a class, but object state makes testing difficult è a class must be tested in every state it can ever enter � (i. e. , state-based testing) Encapsulation – encapsulation hides what is inside an object –> hard to know its state è need to provide a method, for testing only, that reports all of an object’s state Inheritance and polymorphism – If a subclass overrides methods of an already tested superclass, what needs to be tested — only the overridden methods? è No! All of a subclass’s methods need to be tested again due to dynamic binding and substitutability

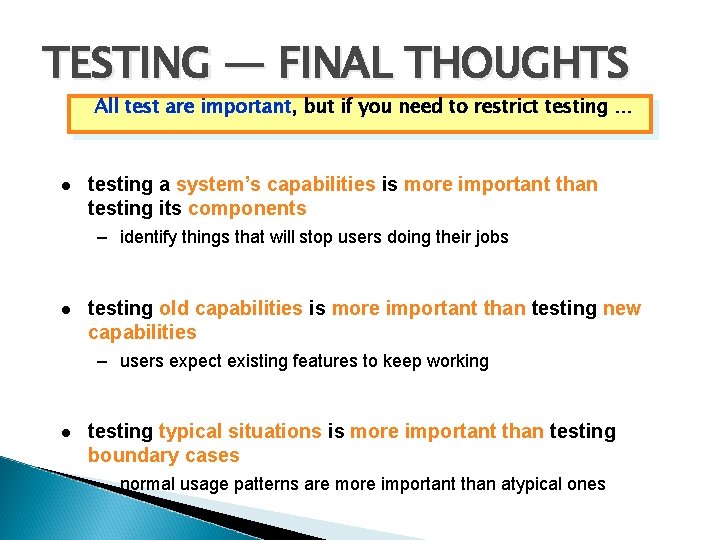

TESTING — FINAL THOUGHTS All test are important, but if you need to restrict testing … testing a system’s capabilities is more important than testing its components – identify things that will stop users doing their jobs testing old capabilities is more important than testing new capabilities – users expect existing features to keep working testing typical situations is more important than testing boundary cases – normal usage patterns are more important than atypical ones

![DEBUGGING 9 3 4 a consequence of testing but a separate activity DEBUGGING [9. 3. 4] �a consequence of testing, but a separate activity – >](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/5bee8f02e6b3fcb2867f72246cd0debc/image-54.jpg)

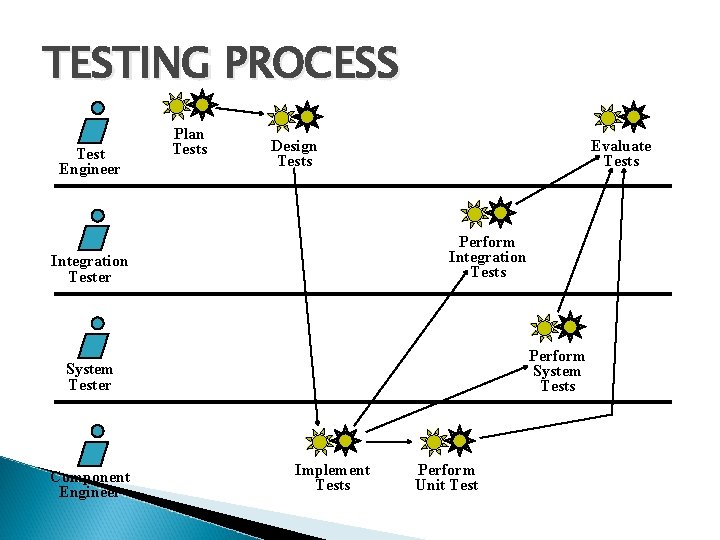

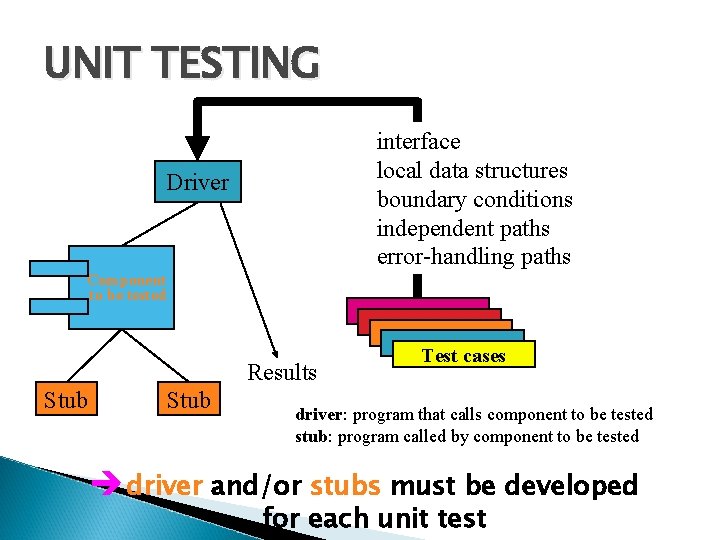

DEBUGGING [9. 3. 4] �a consequence of testing, but a separate activity – > not testing � can be one of the most exasperating parts of development –> easy to lose focus or follow the wrong path! Debugging is like trying to cure a sick person. time required to determine the nature and location of the error time required to correct the error We see the symptoms and try to find the cause.

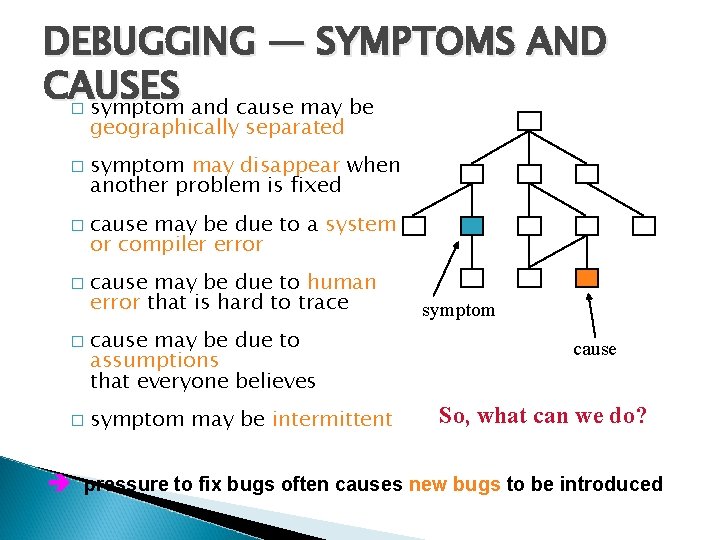

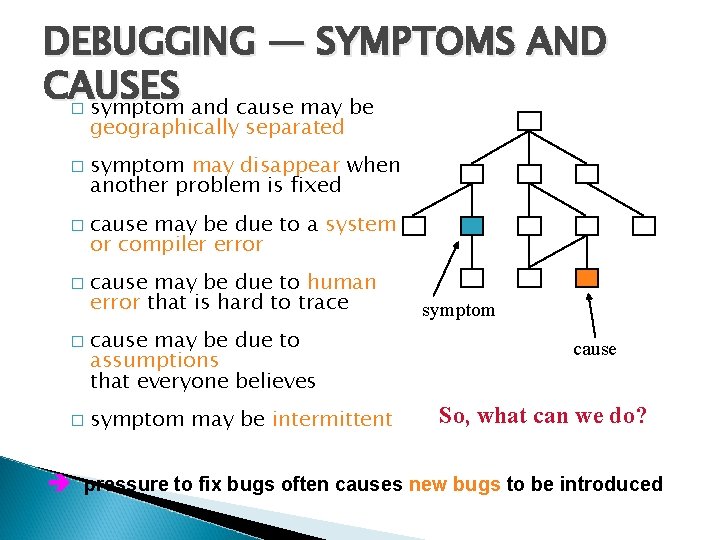

DEBUGGING — SYMPTOMS AND CAUSES symptom and cause may be � � � geographically separated symptom may disappear when another problem is fixed cause may be due to a system or compiler error cause may be due to human error that is hard to trace cause may be due to assumptions that everyone believes symptom may be intermittent symptom cause So, what can we do? è pressure to fix bugs often causes new bugs to be introduced

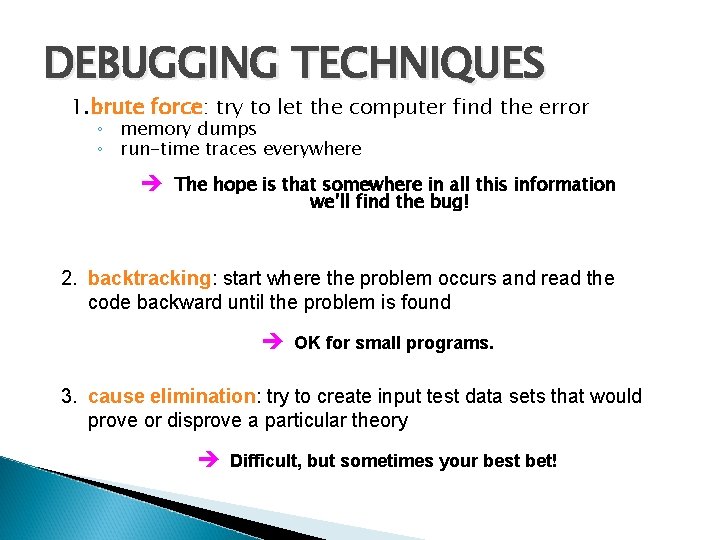

DEBUGGING TECHNIQUES 1. brute force: try to let the computer find the error ◦ memory dumps ◦ run-time traces everywhere è The hope is that somewhere in all this information we’ll find the bug! 2. backtracking: start where the problem occurs and read the code backward until the problem is found è OK for small programs. 3. cause elimination: try to create input test data sets that would prove or disprove a particular theory è Difficult, but sometimes your best bet!

DEBUGGING — FINAL THOUGHTS � debugging tools can help gain more insight into the problem talk to your colleagues — They can see things you’ve grown too tired to see! isolate and focus –> Think through the problem—some of the best debugging happens away from the computer! Be absolutely sure to conduct regression tests when you “fix” the bug!