Telling lies Michael Lacewing enquiriesalevelphilosophy co uk Michael

- Slides: 7

Telling lies Michael Lacewing enquiries@alevelphilosophy. co. uk © Michael Lacewing

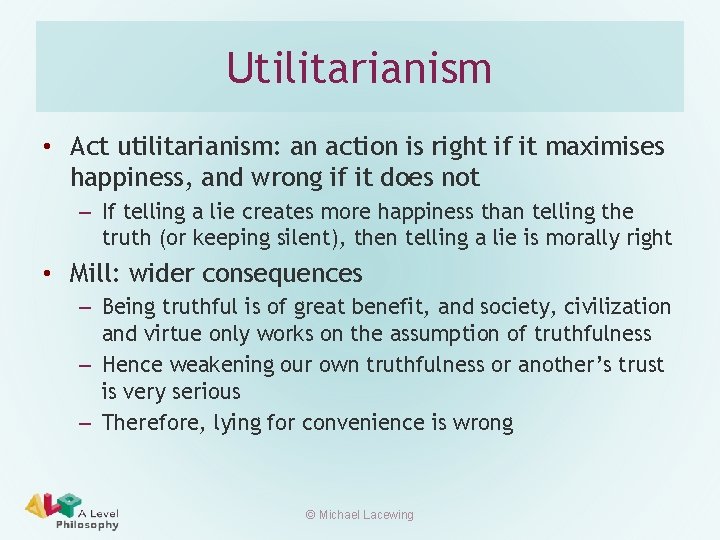

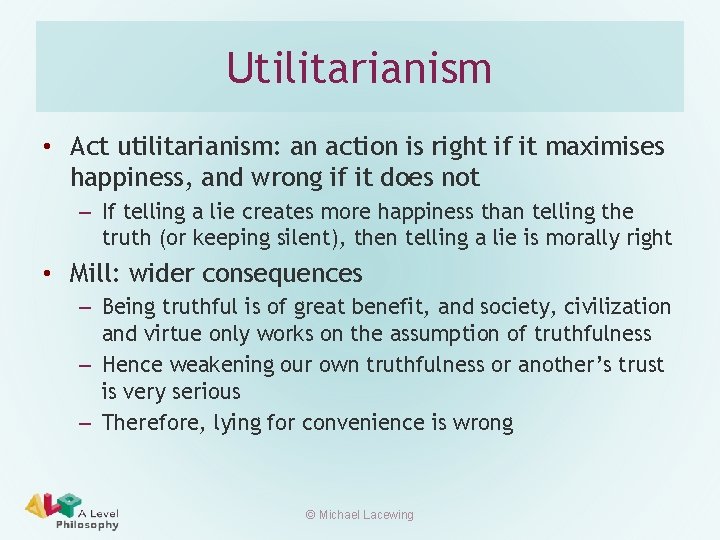

Utilitarianism • Act utilitarianism: an action is right if it maximises happiness, and wrong if it does not – If telling a lie creates more happiness than telling the truth (or keeping silent), then telling a lie is morally right • Mill: wider consequences – Being truthful is of great benefit, and society, civilization and virtue only works on the assumption of truthfulness – Hence weakening our own truthfulness or another’s trust is very serious – Therefore, lying for convenience is wrong © Michael Lacewing

Utilitarianism • Mill: Lying can be permissible, e. g. when it is the only way to withhold information from someone who intends harm – E. g. Kant’s example of the would-be murderer • Rule utilitarianism: an action is right if, and only if, it complies with those rules which, if everybody followed them, would lead to the greatest happiness (compared to any other set of rules) – ‘Never lie’ will not maximize happiness – But it is hard to formalise the best rule © Michael Lacewing

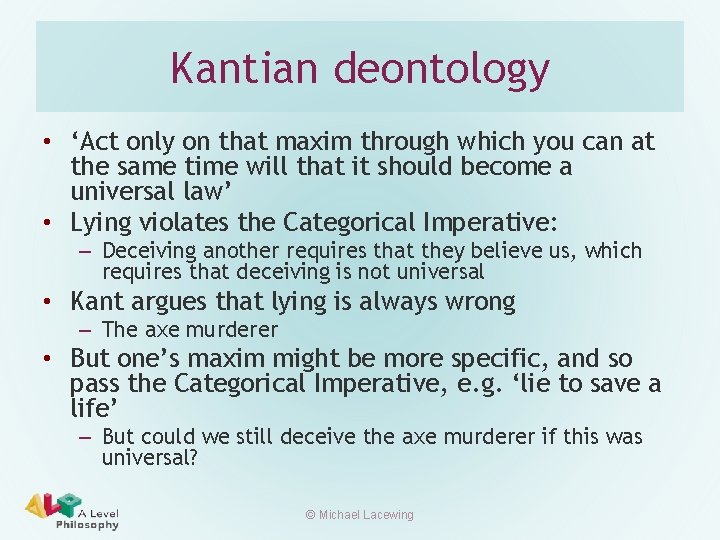

Kantian deontology • ‘Act only on that maxim through which you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law’ • Lying violates the Categorical Imperative: – Deceiving another requires that they believe us, which requires that deceiving is not universal • Kant argues that lying is always wrong – The axe murderer • But one’s maxim might be more specific, and so pass the Categorical Imperative, e. g. ‘lie to save a life’ – But could we still deceive the axe murderer if this was universal? © Michael Lacewing

Kantian deontology • Kant: If we lie, we are responsible for the consequences of our lie – But aren’t we equally responsible for the consequences of doing our duty? • ‘Act in such a way that you always treat humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of any other, never simply as a means, but always at the same time as an end’ • Lying violates the formula of humanity – The deceived person can’t freely choose whether to adopt our end • Kant seems to allow that lying is a ‘weapon of defence’ against someone who intends harm © Michael Lacewing

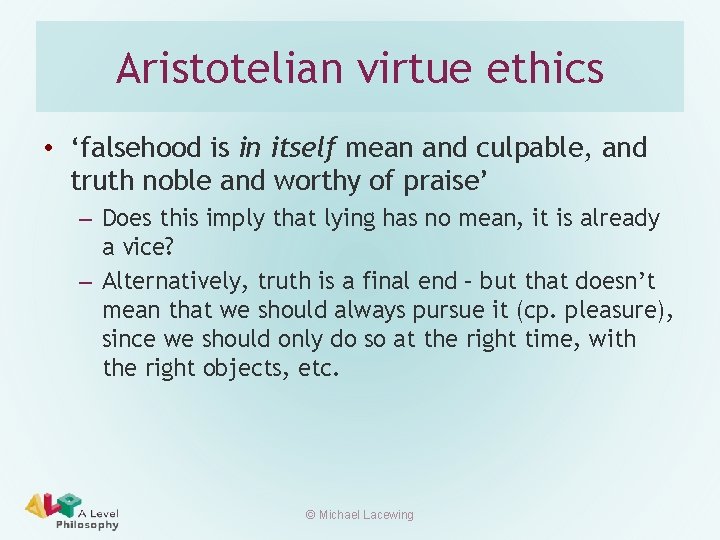

Aristotelian virtue ethics • ‘falsehood is in itself mean and culpable, and truth noble and worthy of praise’ – Does this imply that lying has no mean, it is already a vice? – Alternatively, truth is a final end – but that doesn’t mean that we should always pursue it (cp. pleasure), since we should only do so at the right time, with the right objects, etc. © Michael Lacewing

Aristotelian virtue ethics • Aristotle mainly discusses boastfulness – lying about oneself – This is ‘futile rather than bad’ – It can be done for better or worse motives (e. g. to gain reputation v. gain money) • This indicates that lying is never virtuous – But if there are few rules in ethics, it is unlikely that lying is always wrong – If we lie, we must do so at the right time, with the right motive, about the right truths, and in the right way © Michael Lacewing