Teaching Students to Critically Read Scientific Research Articles

- Slides: 31

Teaching Students to Critically Read Scientific Research Articles Gottesman AJ and Hoskins SG. “C. R. E. A. T. E. Cornerstone: Introduction to Scientific Thinking, a new course for STEM-interested freshmen, demystifies scientific thinking through analysis of scientific literature. ” CBE Life Sci Educ. March 4, 2013 12: 59 -72. Hoskins S, Stevens L, and Nehm R. “Selective Use of Primary Literature Transforms the Classroom into a Virtual Laboratory. ” 2007. Genetics, 176 1381 -1389. https: //teachcreate. org/

Warm up What are some of the challenges in learning how to read primary literature in your field? What study strategies do you want students to use when reading primary literature? What skills would you want students to execute as they critically read primary literature? Why is it important for students to read primary literature? (What are they supposed to get out of it? ) When do you expect students to learn how to read primary literature?

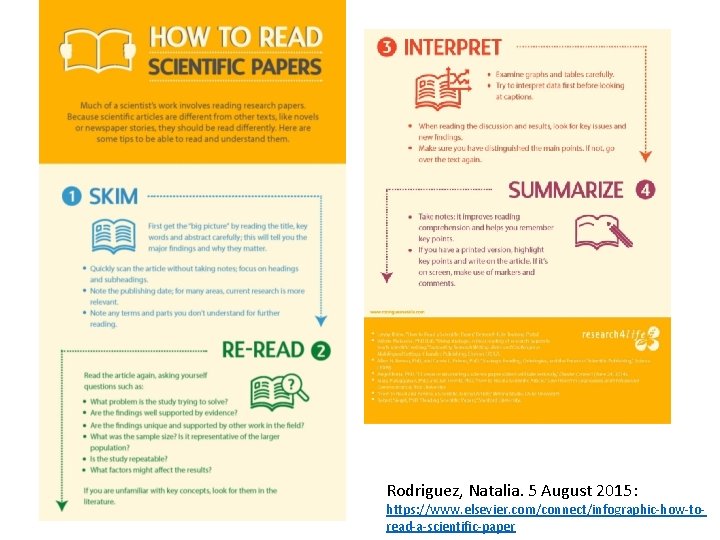

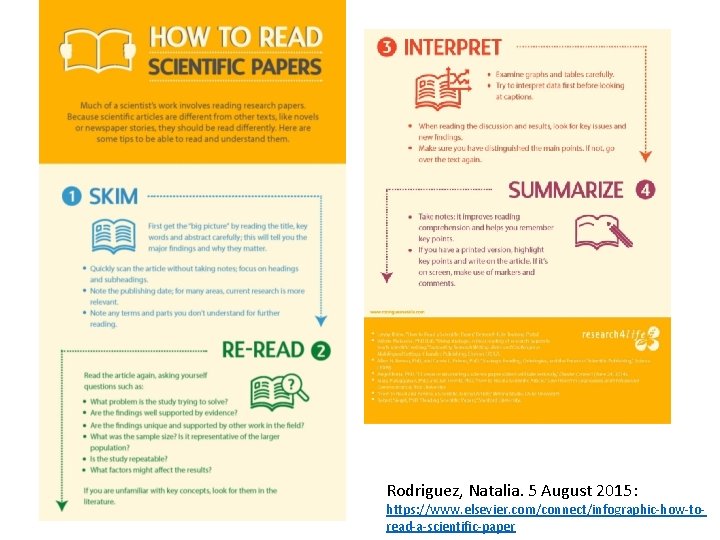

Rodriguez, Natalia. 5 August 2015: https: //www. elsevier. com/connect/infographic-how-toread-a-scientific-paper

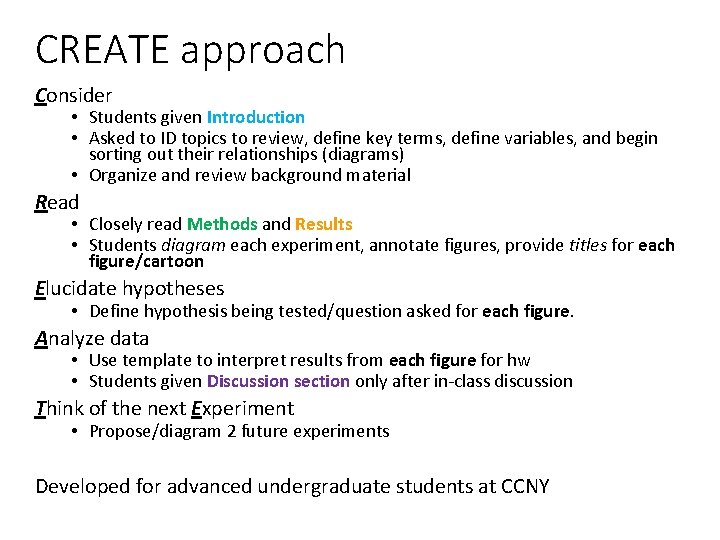

CREATE approach Consider • Students given Introduction • Asked to ID topics to review, define key terms, define variables, and begin sorting out their relationships (diagrams) • Organize and review background material Read • Closely read Methods and Results • Students diagram each experiment, annotate figures, provide titles for each figure/cartoon Elucidate hypotheses • Define hypothesis being tested/question asked for each figure. Analyze data • Use template to interpret results from each figure for hw • Students given Discussion section only after in-class discussion Think of the next Experiment • Propose/diagram 2 future experiments Developed for advanced undergraduate students at CCNY

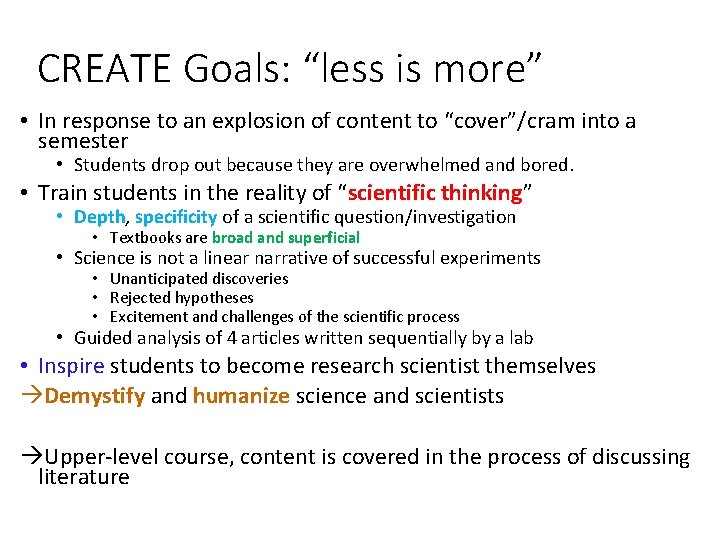

CREATE Goals: “less is more” • In response to an explosion of content to “cover”/cram into a semester • Students drop out because they are overwhelmed and bored. • Train students in the reality of “scientific thinking” • Depth, specificity of a scientific question/investigation • Textbooks are broad and superficial • Science is not a linear narrative of successful experiments • Unanticipated discoveries • Rejected hypotheses • Excitement and challenges of the scientific process • Guided analysis of 4 articles written sequentially by a lab • Inspire students to become research scientist themselves àDemystify and humanize science and scientists àUpper-level course, content is covered in the process of discussing literature

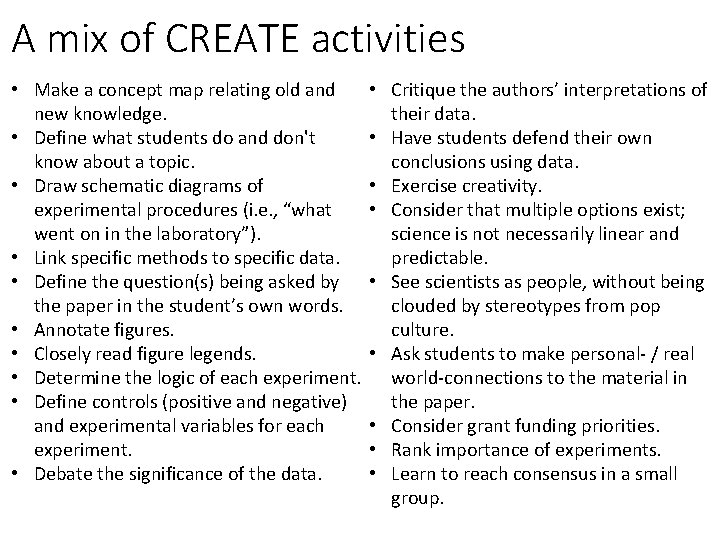

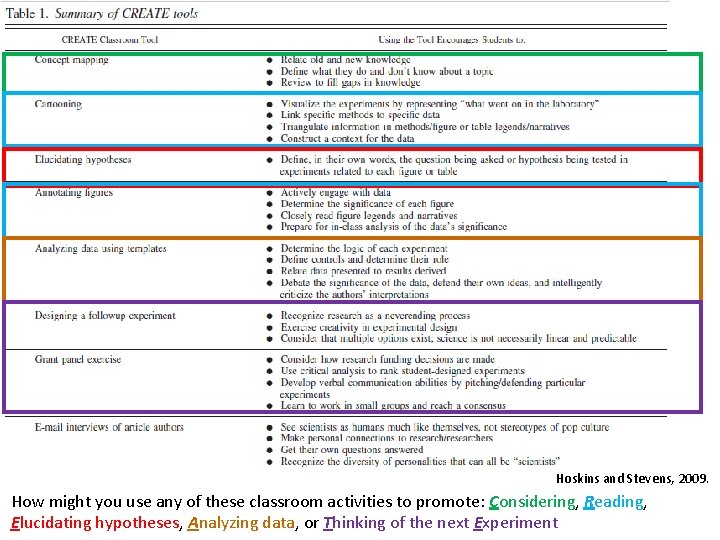

A mix of CREATE activities • Make a concept map relating old and new knowledge. • Define what students do and don't know about a topic. • Draw schematic diagrams of experimental procedures (i. e. , “what went on in the laboratory”). • Link specific methods to specific data. • Define the question(s) being asked by the paper in the student’s own words. • Annotate figures. • Closely read figure legends. • Determine the logic of each experiment. • Define controls (positive and negative) and experimental variables for each experiment. • Debate the significance of the data. • Critique the authors’ interpretations of their data. • Have students defend their own conclusions using data. • Exercise creativity. • Consider that multiple options exist; science is not necessarily linear and predictable. • See scientists as people, without being clouded by stereotypes from pop culture. • Ask students to make personal- / real world-connections to the material in the paper. • Consider grant funding priorities. • Rank importance of experiments. • Learn to reach consensus in a small group.

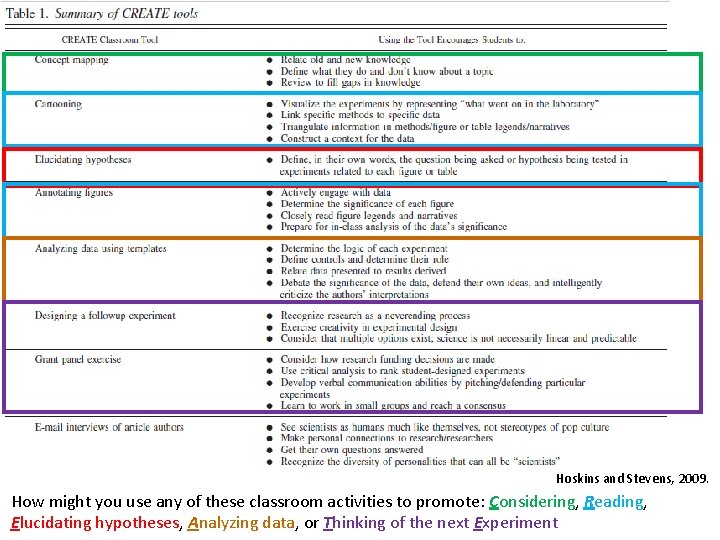

Hoskins and Stevens, 2009. How might you use any of these classroom activities to promote: Considering, Reading, Elucidating hypotheses, Analyzing data, or Thinking of the next Experiment

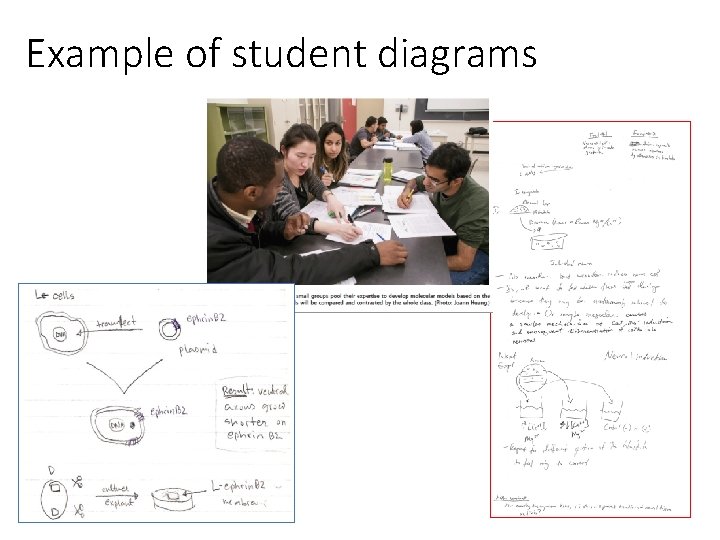

Example of student diagrams

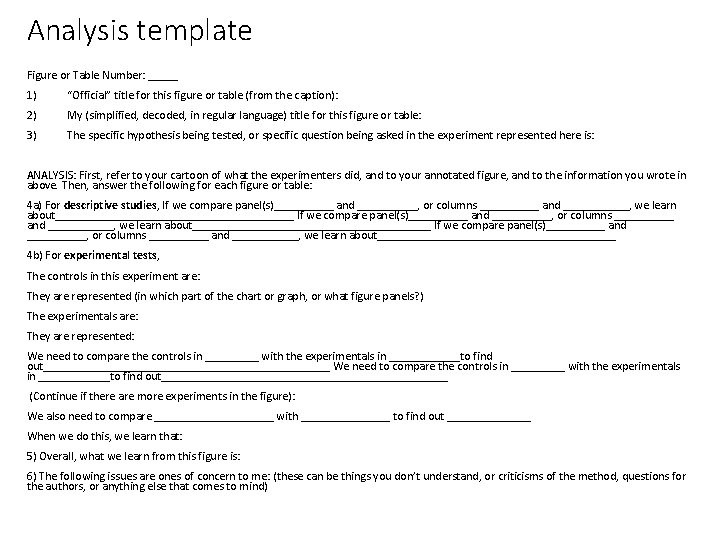

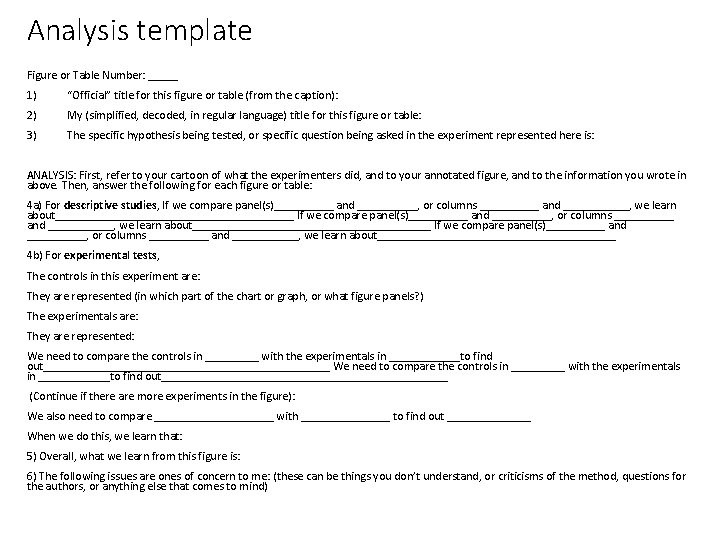

Analysis template Figure or Table Number: _____ 1) “Official” title for this figure or table (from the caption): 2) My (simplified, decoded, in regular language) title for this figure or table: 3) The specific hypothesis being tested, or specific question being asked in the experiment represented here is: ANALYSIS: First, refer to your cartoon of what the experimenters did, and to your annotated figure, and to the information you wrote in above. Then, answer the following for each figure or table: 4 a) For descriptive studies, If we compare panel(s)__________ and __________, or columns __________ and ___________, we learn about________________________________________ If we compare panel(s)_____ and _____, or columns _____ and ______, we learn about____________________ 4 b) For experimental tests, The controls in this experiment are: They are represented (in which part of the chart or graph, or what figure panels? ) The experimentals are: They are represented: We need to compare the controls in _________ with the experimentals in ____________to find out________________________________________________ (Continue if there are more experiments in the figure): We also need to compare __________ with ________ to find out _______ When we do this, we learn that: 5) Overall, what we learn from this figure is: 6) The following issues are ones of concern to me: (these can be things you don’t understand, or criticisms of the method, questions for the authors, or anything else that comes to mind)

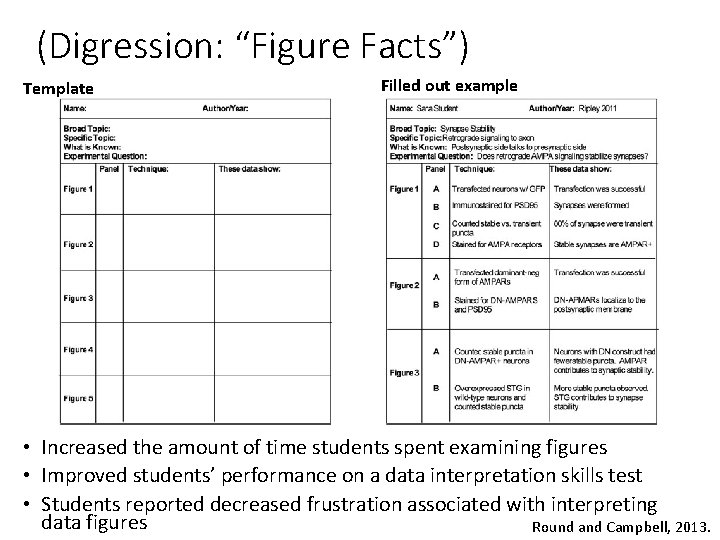

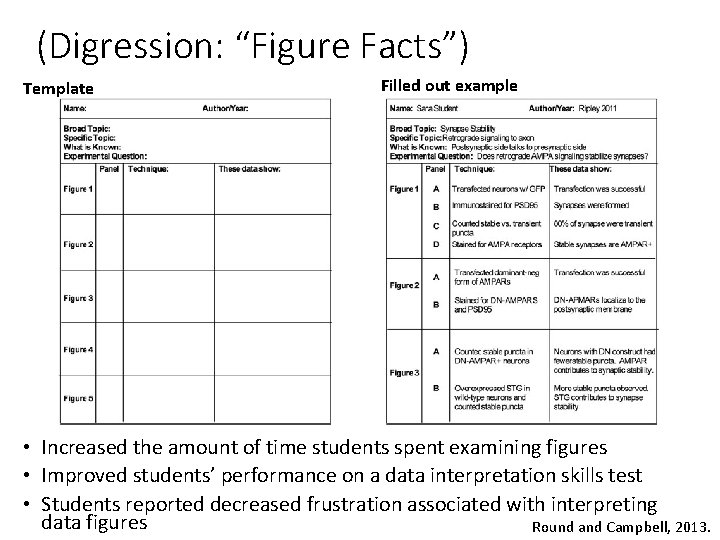

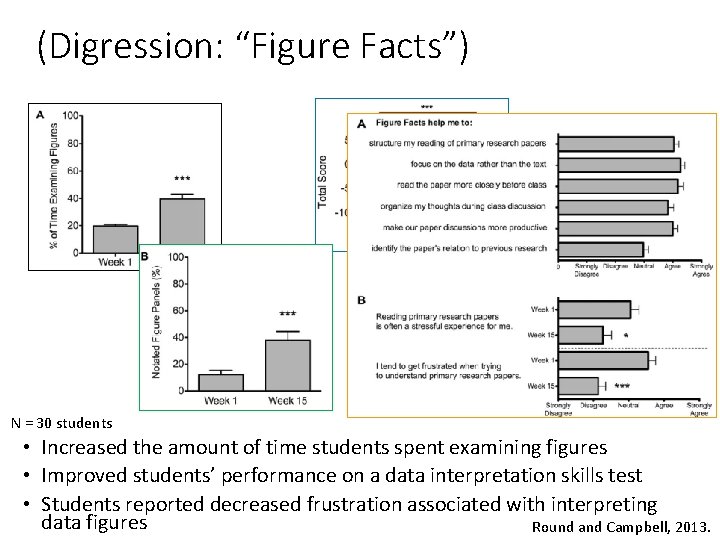

(Digression: “Figure Facts”) Template Filled out example • Increased the amount of time students spent examining figures • Improved students’ performance on a data interpretation skills test • Students reported decreased frustration associated with interpreting data figures Round and Campbell, 2013.

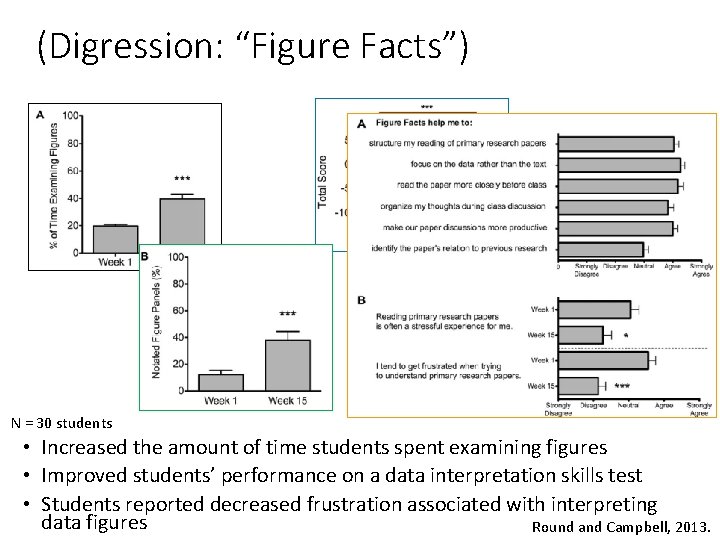

(Digression: “Figure Facts”) N = 30 students • Increased the amount of time students spent examining figures • Improved students’ performance on a data interpretation skills test • Students reported decreased frustration associated with interpreting data figures Round and Campbell, 2013.

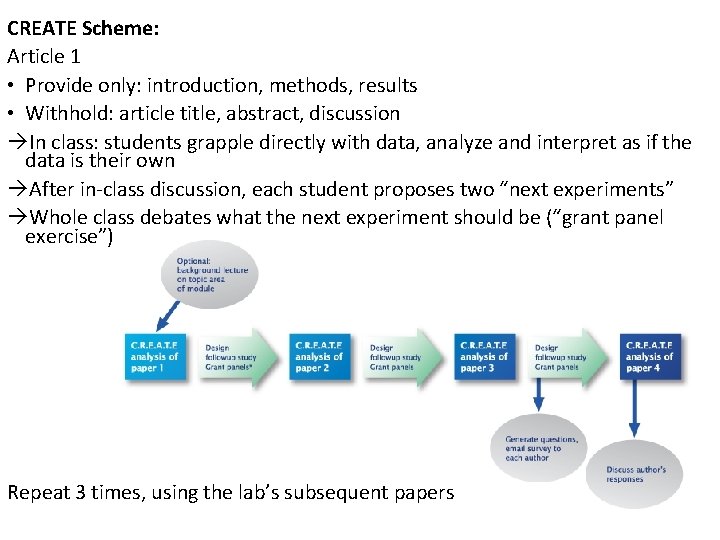

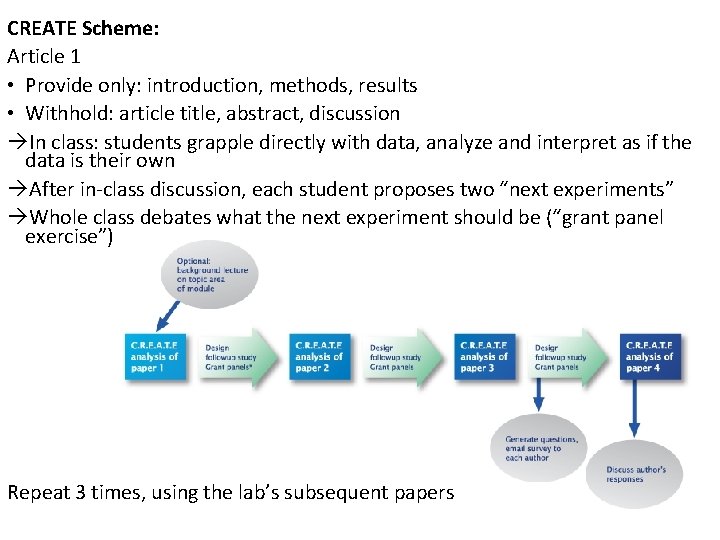

CREATE Scheme: Article 1 • Provide only: introduction, methods, results • Withhold: article title, abstract, discussion àIn class: students grapple directly with data, analyze and interpret as if the data is their own àAfter in-class discussion, each student proposes two “next experiments” àWhole class debates what the next experiment should be (“grant panel exercise”) Repeat 3 times, using the lab’s subsequent papers

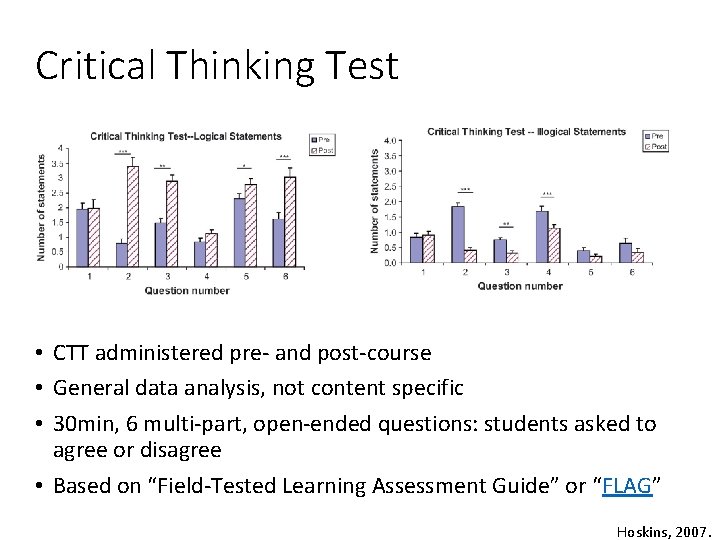

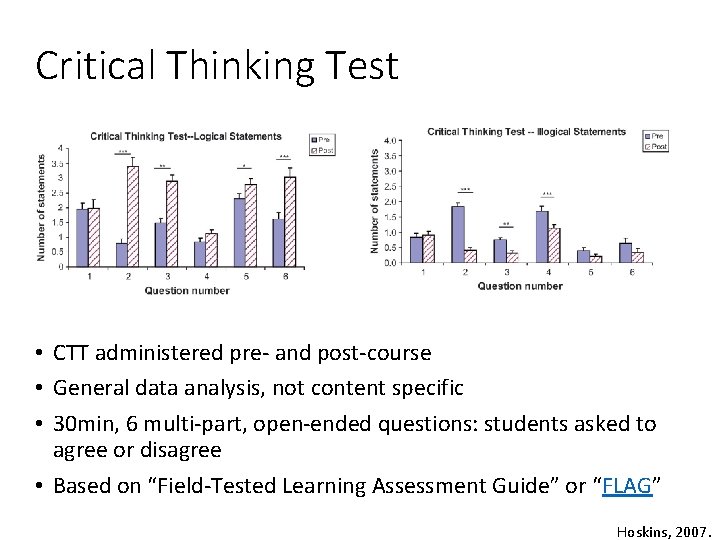

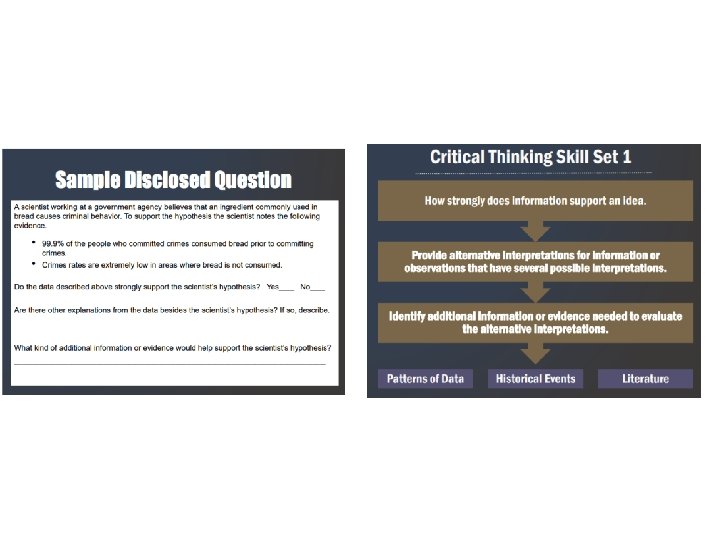

Critical Thinking Test • CTT administered pre- and post-course • General data analysis, not content specific • 30 min, 6 multi-part, open-ended questions: students asked to agree or disagree • Based on “Field-Tested Learning Assessment Guide” or “FLAG” Hoskins, 2007.

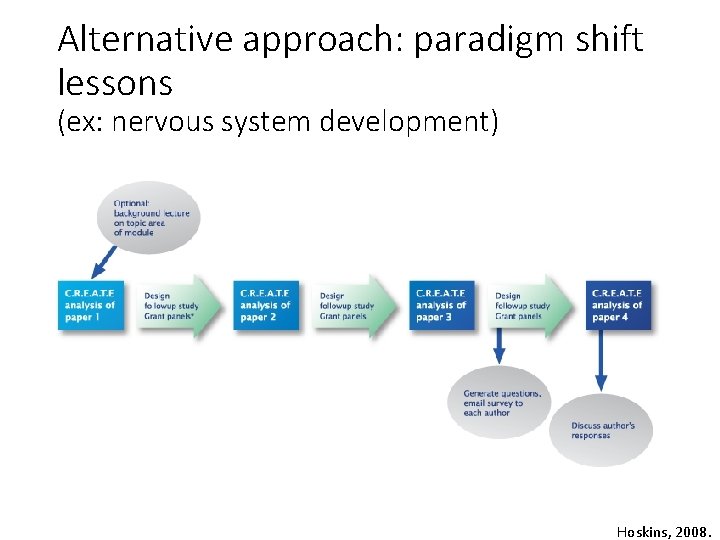

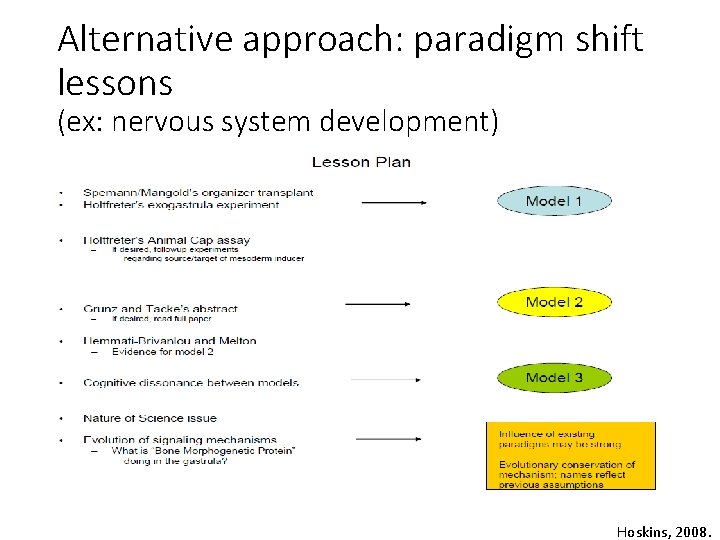

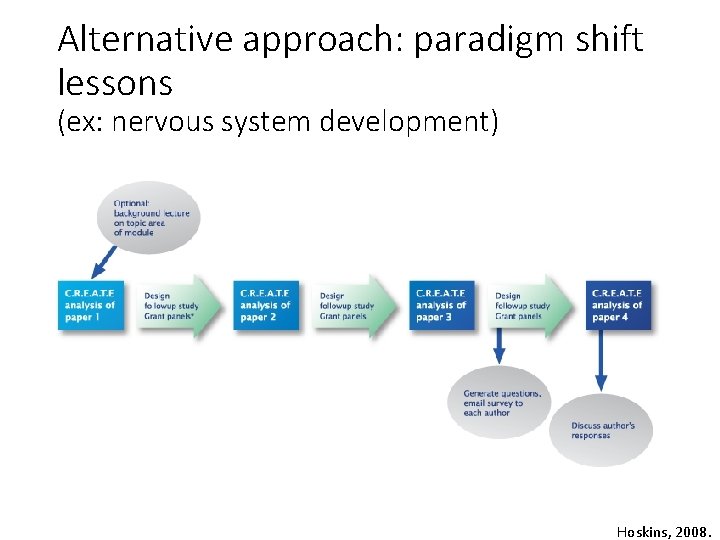

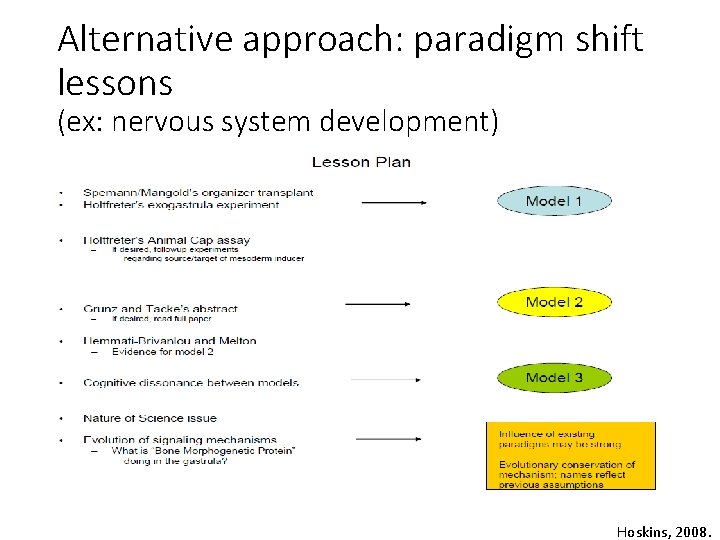

Alternative approach: paradigm shift lessons (ex: nervous system development) Hoskins, 2008.

Alternative approach: paradigm shift lessons (ex: nervous system development) Hoskins, 2008.

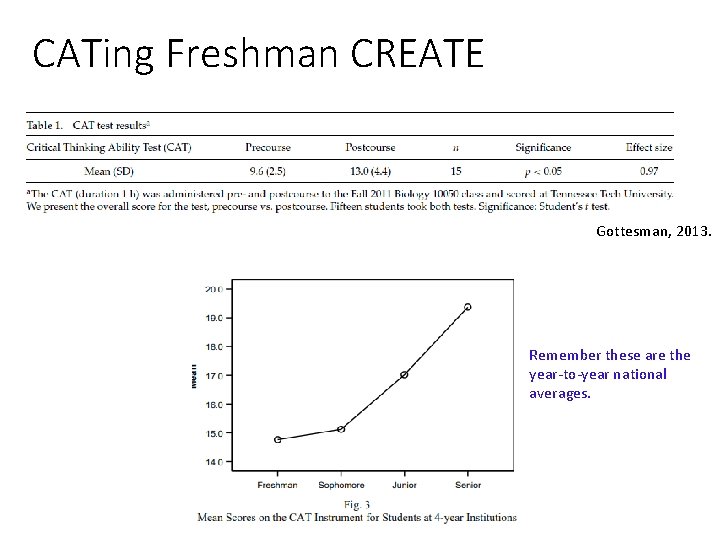

Applying CREATE to an intro class • New course (Bio 10050): 69% female, 59% URM • Changes from Bio 35500: • Freshmen were started off with several popular press articles as a “warm up” • Newspaper and magazine articles about scientists or discoveries • Finished semester by reading 2 research articles (in sequence from the same lab) • Streamlined topic • All readings engaged the same topic Gottesman, 2013.

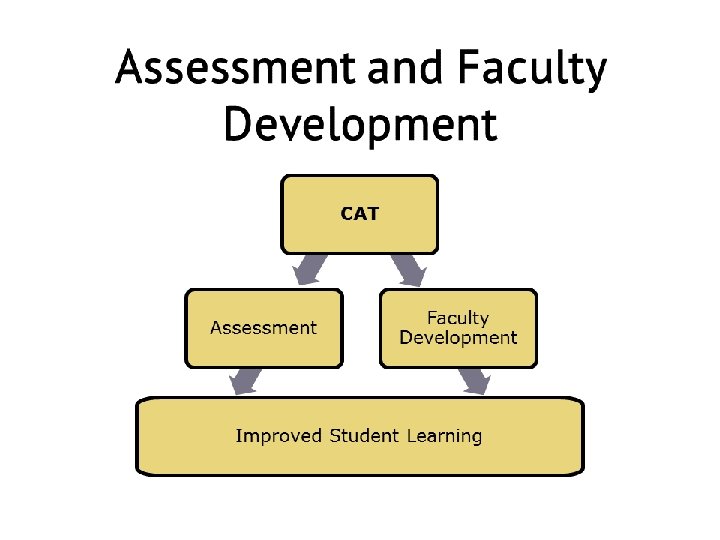

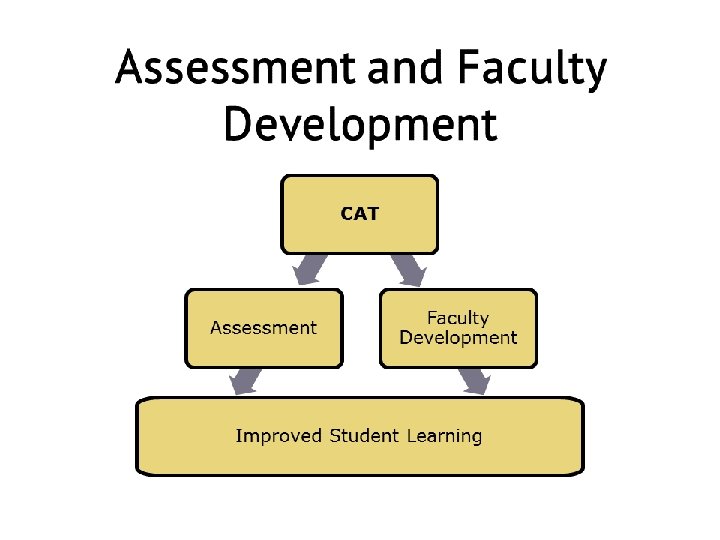

Critical Thinking Assessment Test (“CAT”) https: //www. tntech. edu/cat/ • Tennessee Tech U originally partnered with six other institutions across the U. S. to evaluate and refine the CAT instrument beginning in 2004. • National dissemination began in 2007.

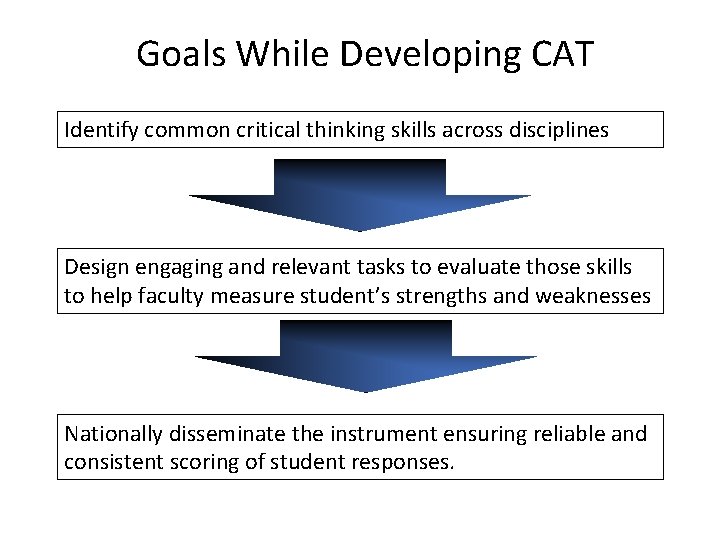

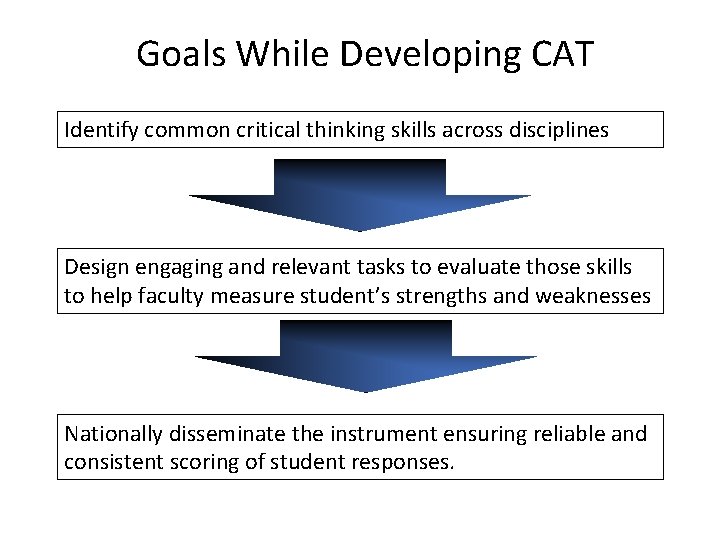

Goals While Developing CAT Identify common critical thinking skills across disciplines Design engaging and relevant tasks to evaluate those skills to help faculty measure student’s strengths and weaknesses Nationally disseminate the instrument ensuring reliable and consistent scoring of student responses.

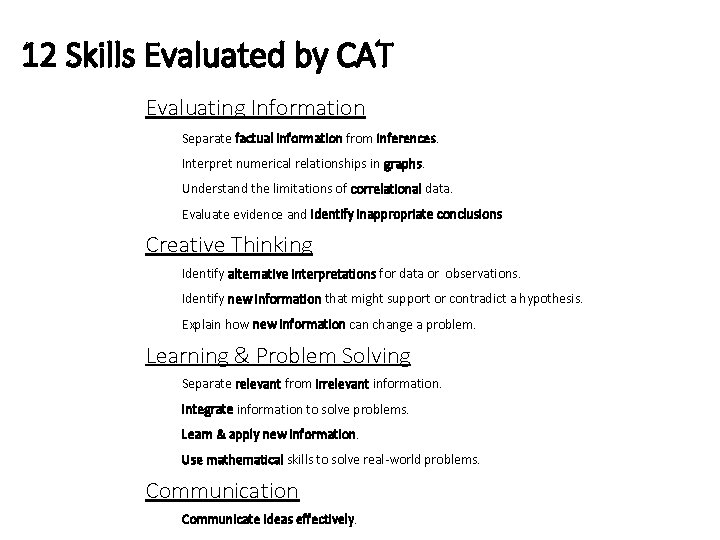

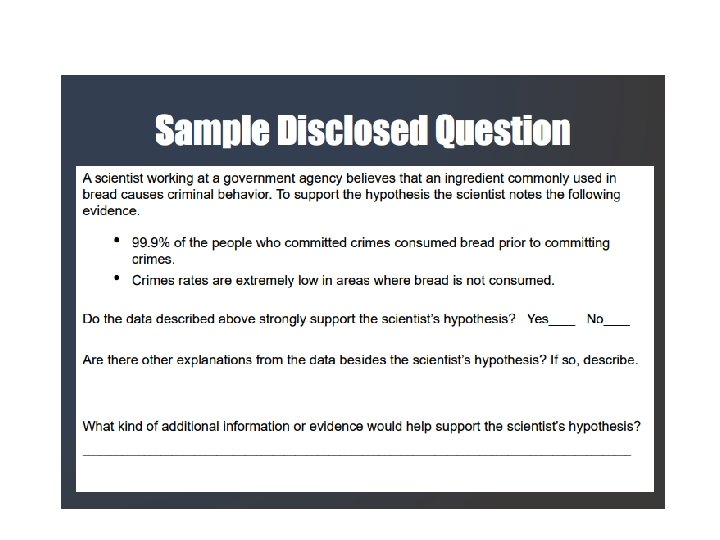

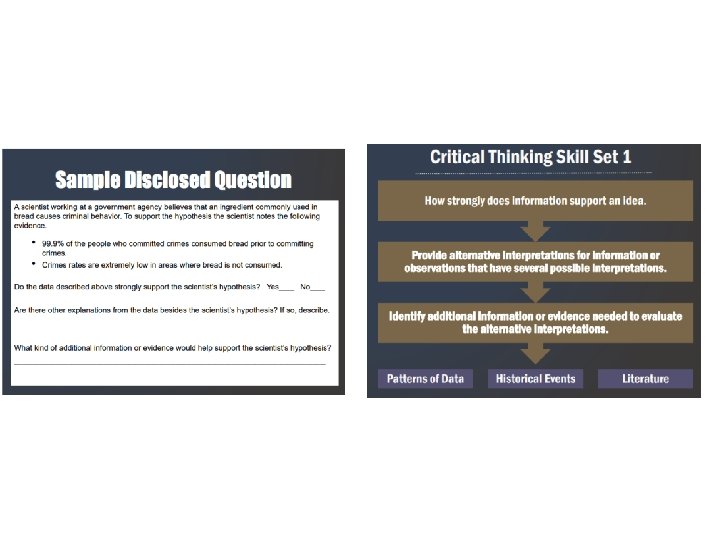

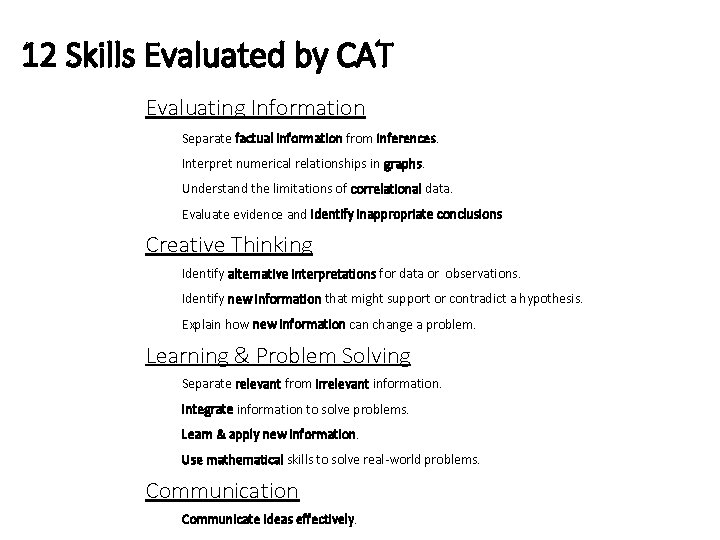

12 Skills Evaluated by CAT Evaluating Information Separate factual information from inferences. Interpret numerical relationships in graphs. Understand the limitations of correlational data. Evaluate evidence and identify inappropriate conclusions Creative Thinking Identify alternative interpretations for data or observations. Identify new information that might support or contradict a hypothesis. Explain how new information can change a problem. Learning & Problem Solving Separate relevant from irrelevant information. Integrate information to solve problems. Learn & apply new information. Use mathematical skills to solve real-world problems. Communication Communicate ideas effectively.

CAT features One hour exam • Mostly short answer essay • Scored by faculty in workshops • Detailed scoring guide • Reliable & Valid • Sensitive to changes in a single course or informal learning experience • SLOW: “How long will it take faculty to score the CAT and how many tests can they score in one scoring workshop? Faculty get faster at scoring with practice. Don't expect to score more than 6 -7 tests per faculty member during your first full-day scoring workshop. The number of tests that can be scored will increase considerably during the next scoring session (e. g. , 10 -12 person). ” –from FAQ

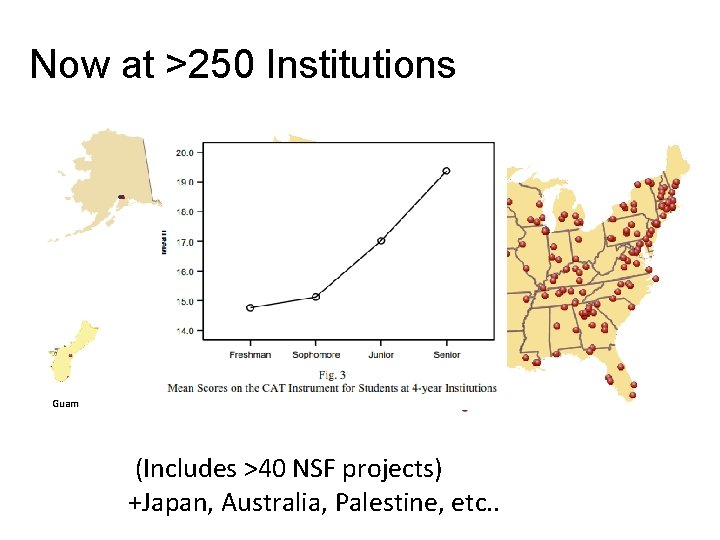

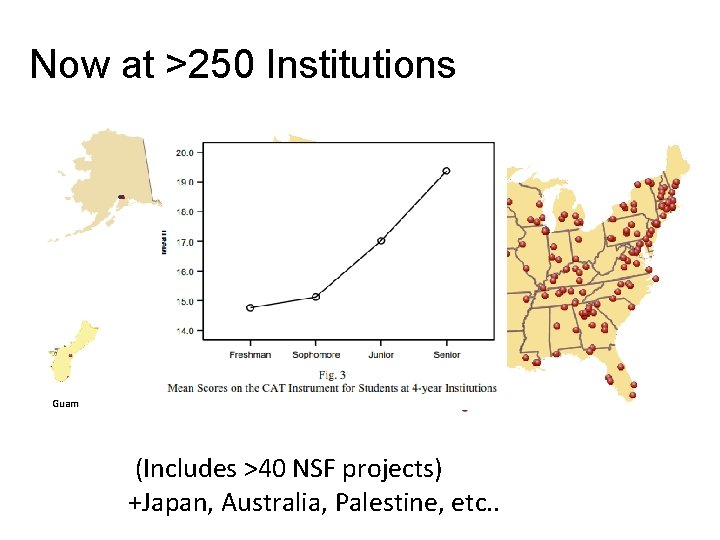

Now at >250 Institutions Guam Hawaii (Includes >40 NSF projects) +Japan, Australia, Palestine, etc. .

Desired CAT Implementation

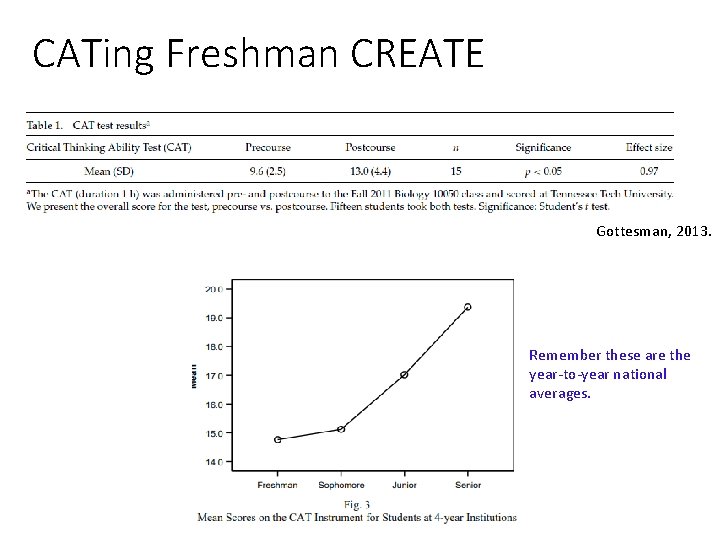

CATing Freshman CREATE Gottesman, 2013. Remember these are the year-to-year national averages.

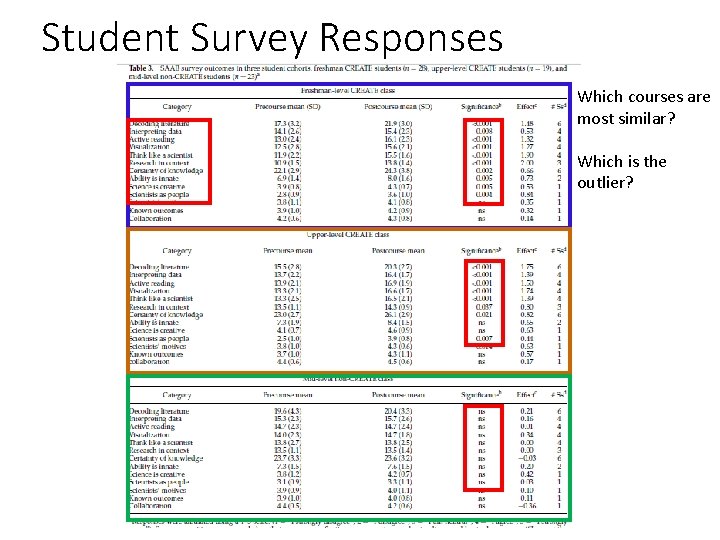

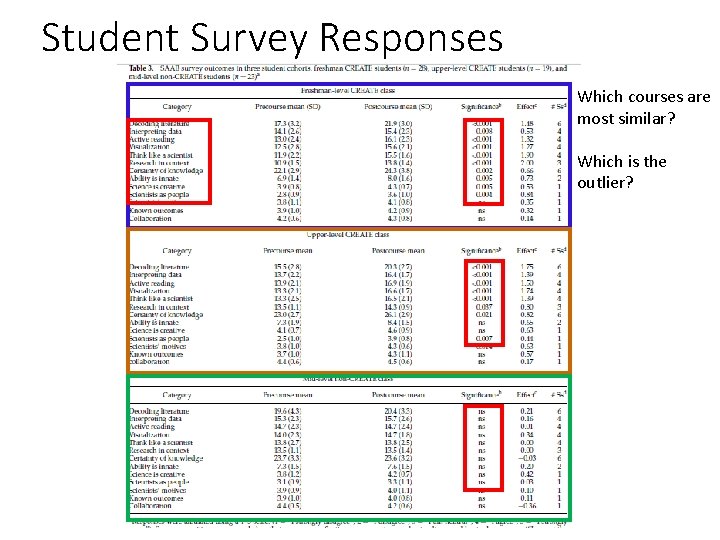

Student Survey Responses Which courses are most similar? Which is the outlier?

Conclusions • CREATE promotes student • • • critical thinking content integration ability to design and interpret experiments attitudes towards science and scientists self-confidence as scientists • Is applicable for advanced students and freshmen (although it serves different roles) • Can be applied to popular newspaper and magazine science articles • Labs are often considered the best ways to: • teach creative and critical thinking • teach what it means to be a “scientist” • Can these effects be replicated in a classroom? • Does “CREATE” do so?

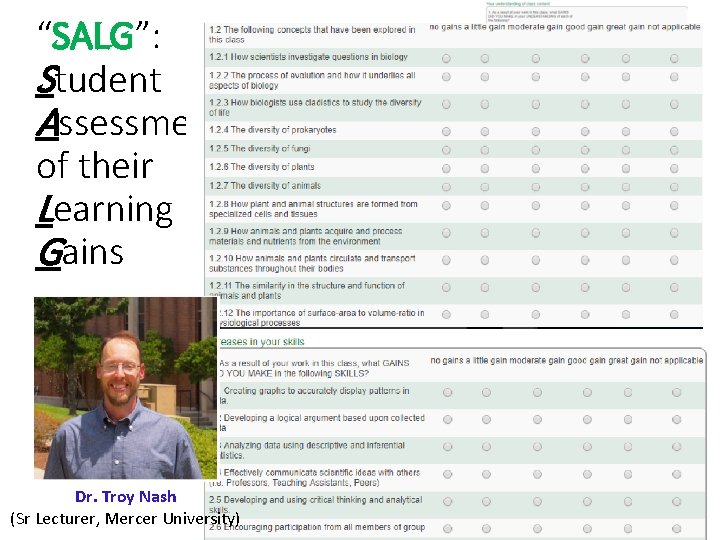

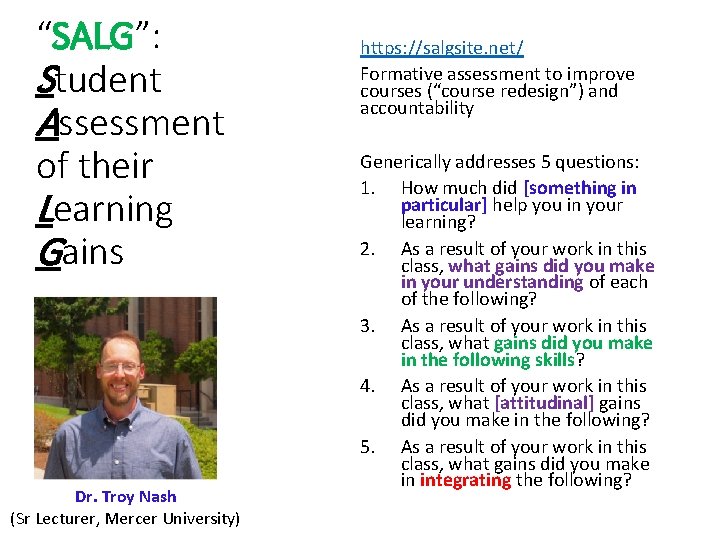

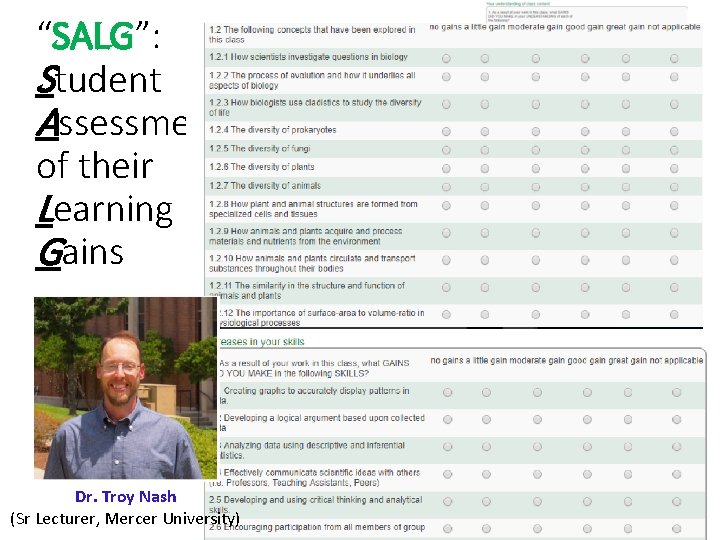

“SALG”: Student Assessment of their Learning Gains Dr. Troy Nash (Sr Lecturer, Mercer University) https: //salgsite. net/ Formative assessment to improve courses (“course redesign”) and accountability Generically addresses 5 questions: 1. How much did [something in particular] help you in your learning? 2. As a result of your work in this class, what gains did you make in your understanding of each of the following? 3. As a result of your work in this class, what gains did you make in the following skills? 4. As a result of your work in this class, what [attitudinal] gains did you make in the following? 5. As a result of your work in this class, what gains did you make in integrating the following?

“SALG”: Student Assessment of their Learning Gains Dr. Troy Nash (Sr Lecturer, Mercer University)

“SALG”: Student Assessment of their Learning Gains https: //salgsite. net/ Formative assessment to improve courses (“course redesign”) and accountability