Teaching not by the book An Effective Approach

Teaching not by the book: An Effective Approach to Indigenous Behaviour & Classroom Management

Journey to Behaviour Management Let’s have a yarn and come along on a journey to learning about behaviour management strategies (and some cross over to general classroom management) in an Indigenous context. This resource came about from our search for answers about how best to approach behaviour in an Indigenous setting. Or perhaps more so, how is it different to what we already know? What we came to understand, is behaviour management is generally universal.

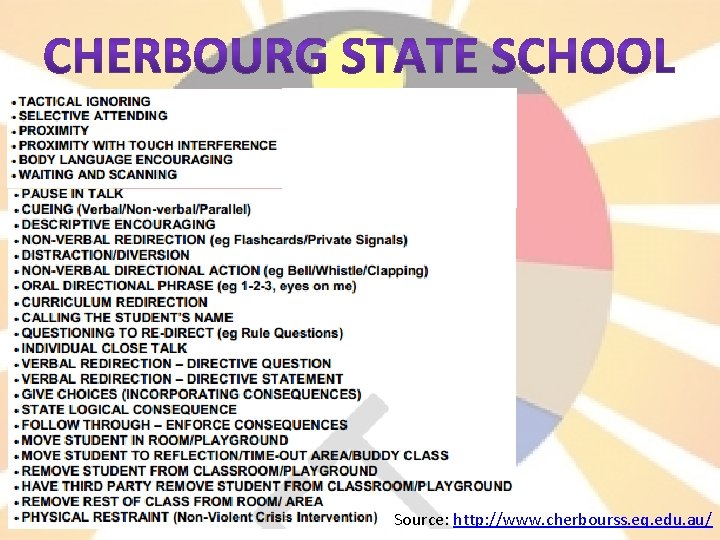

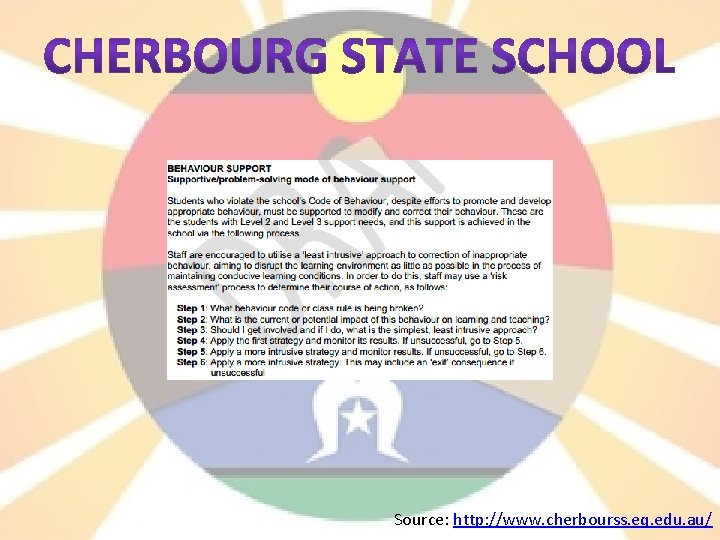

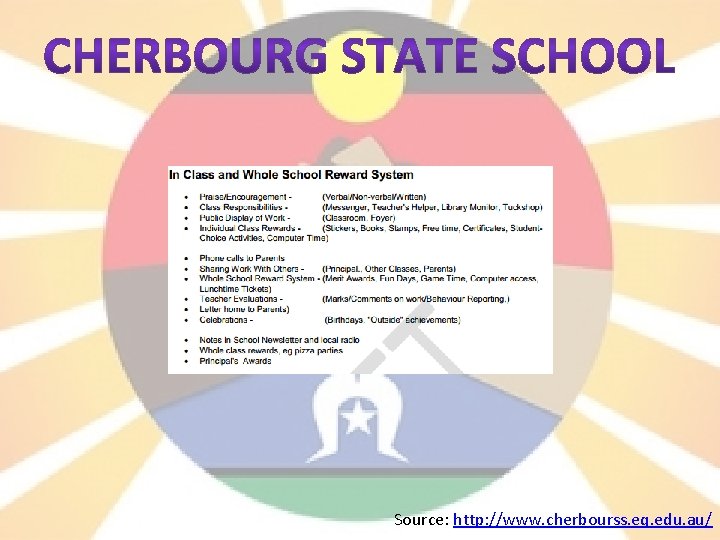

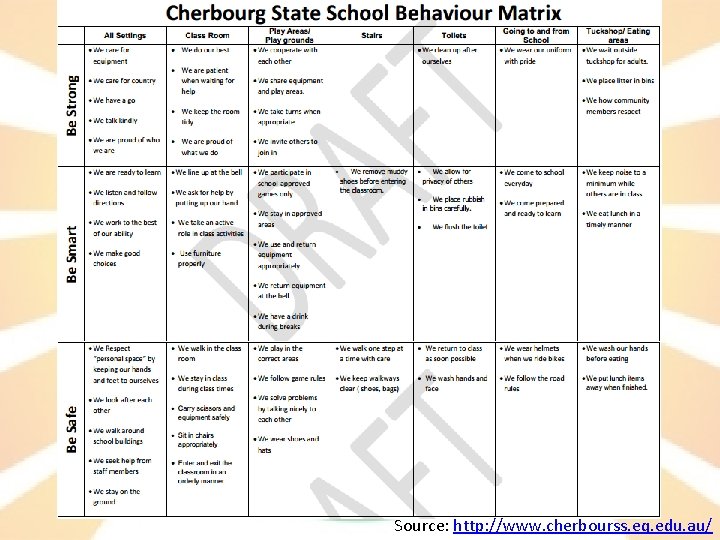

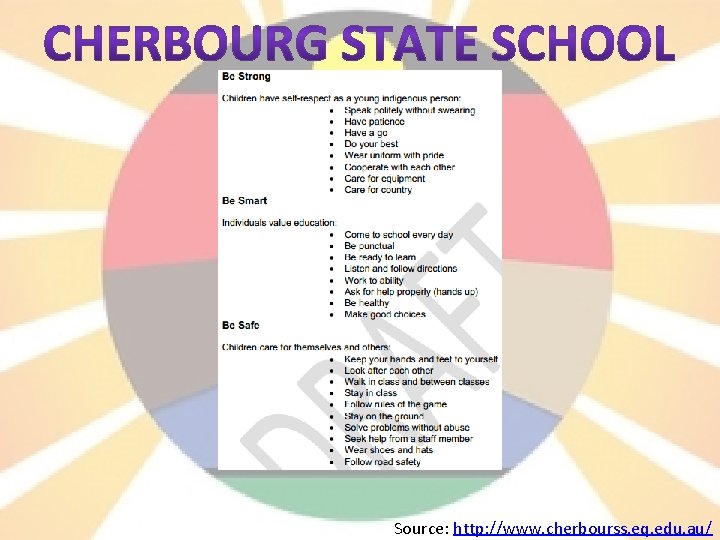

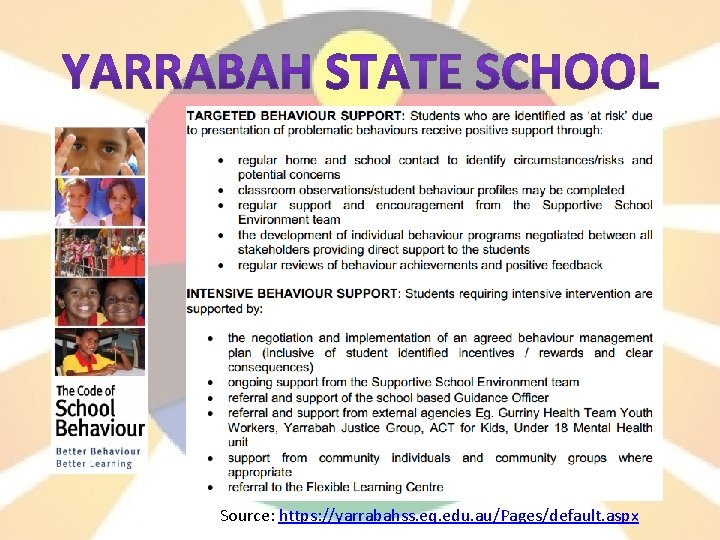

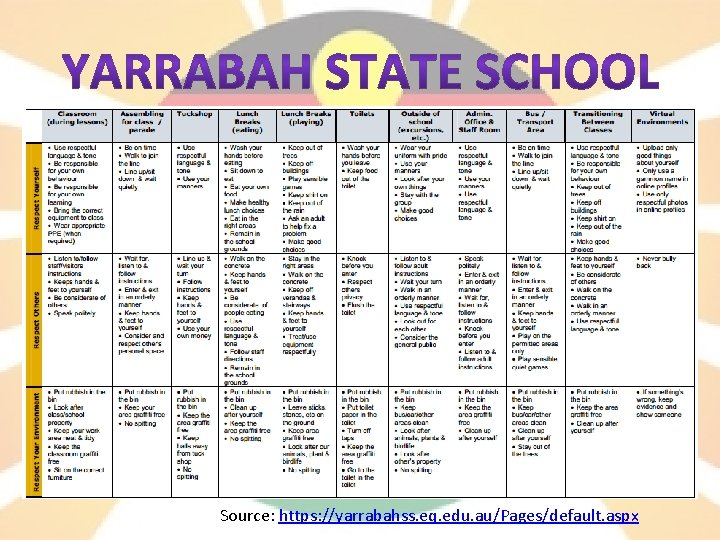

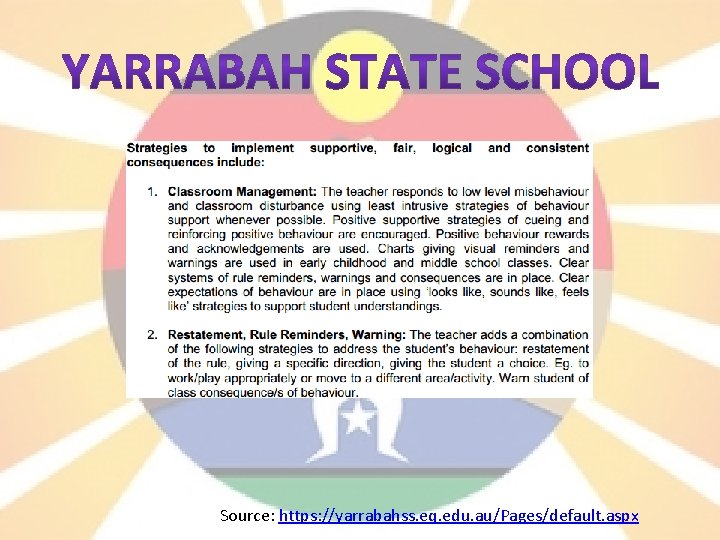

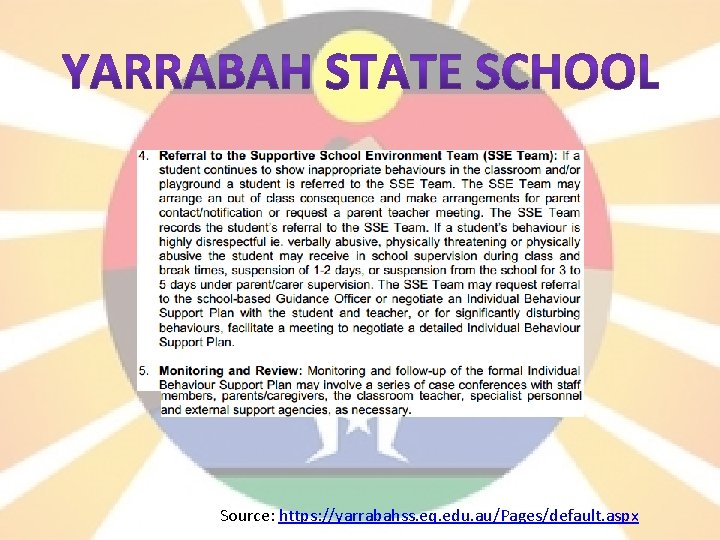

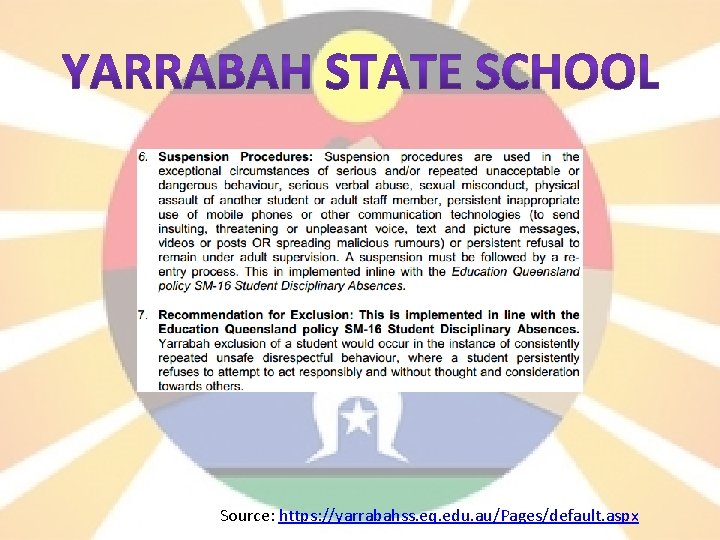

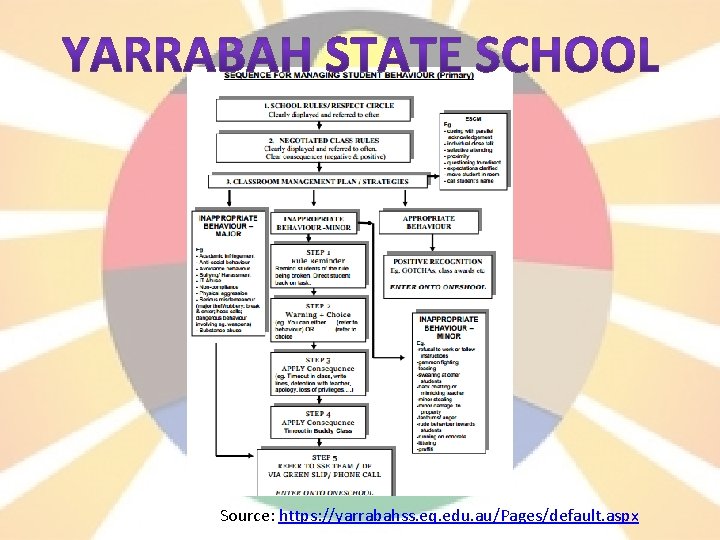

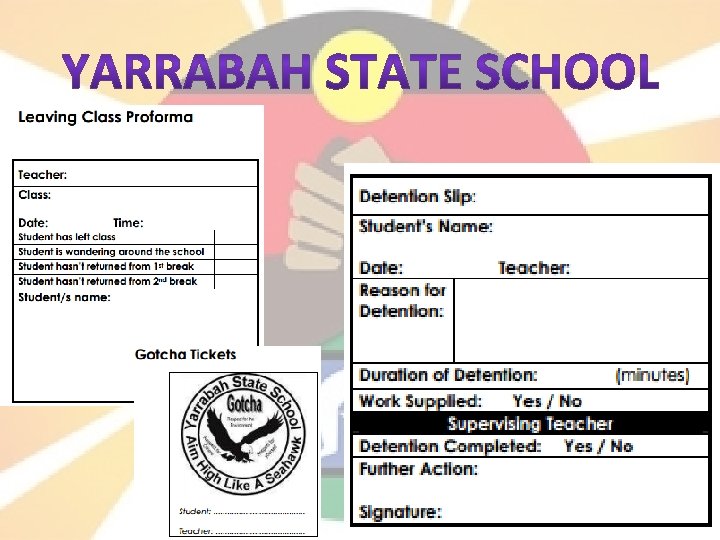

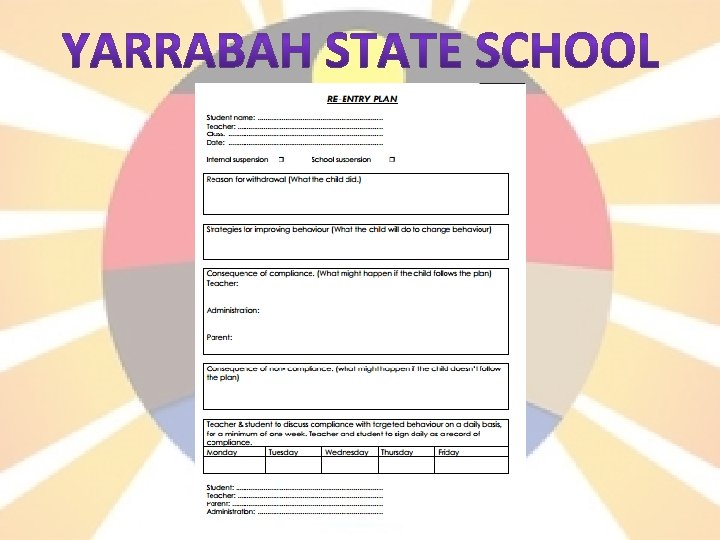

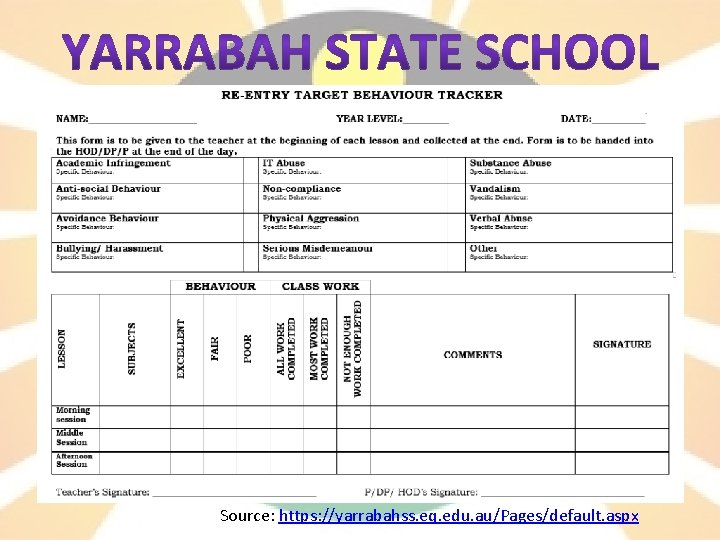

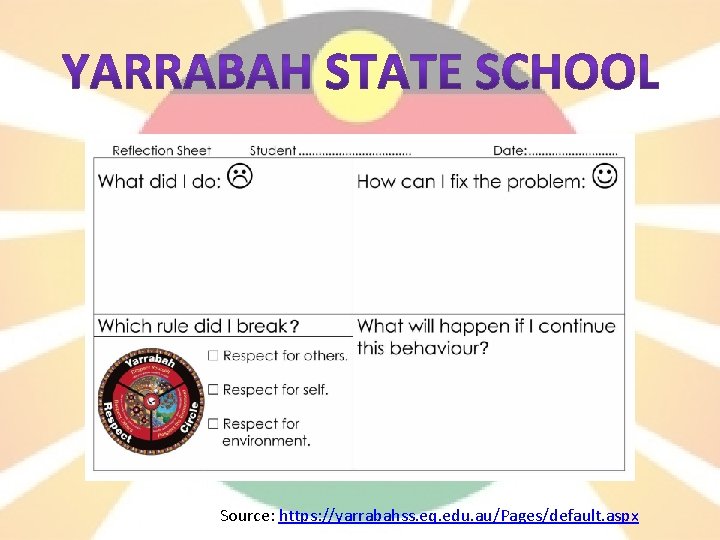

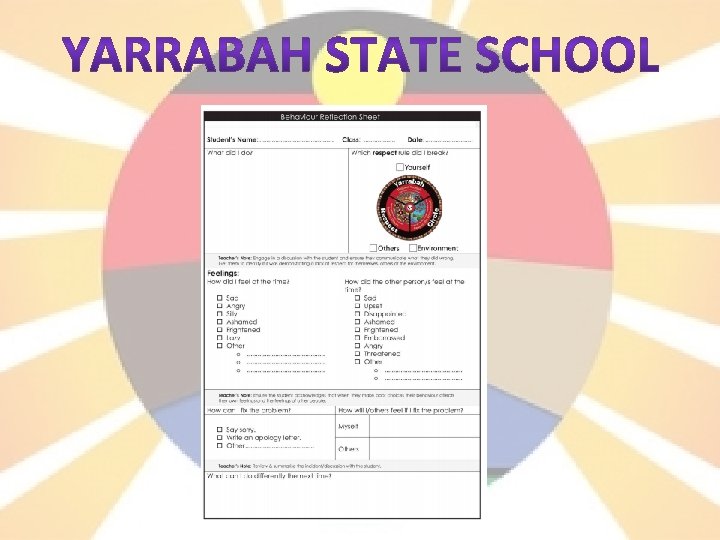

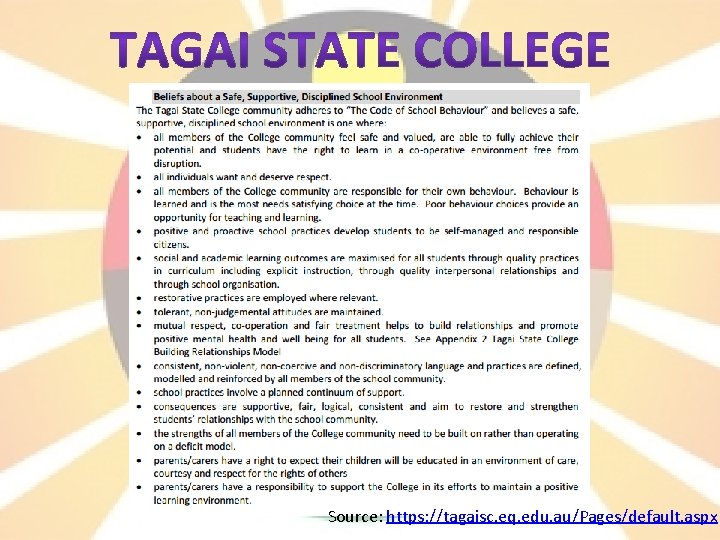

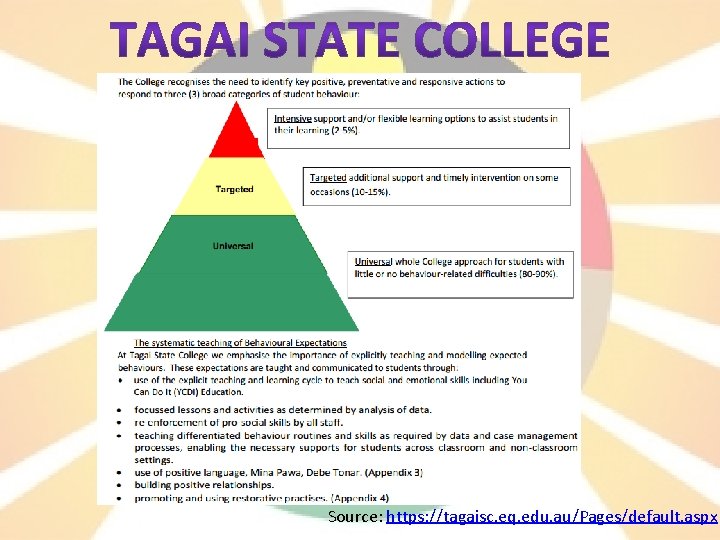

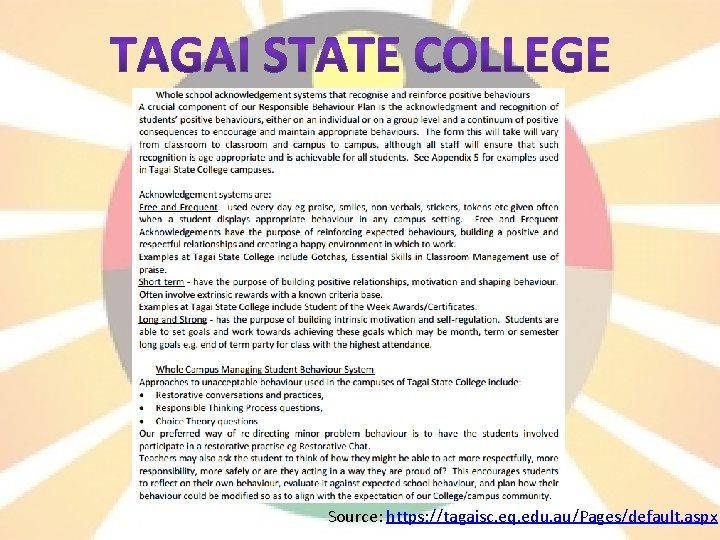

Real Life Samples Our research started by exploring a sample consisting of three different QLD whole school behaviour management plans and how they are implemented. (The schools included Cherbourg in South East QLD, Tagai State College in the Torres Strait and Yarrabah in Far North QLD). The links can be found on our website. What immediately struck us, were the similarities. Not just in underpinning principles but how they compared to schools on the Sunshine Coast. We dug deeper and found copious research into behaviour management in Indigenous schools and began to question where the differences arise between remote and metro schools. This sample is related to QLD specifically however we feel there is scope to adjust and apply the content to Indigenous locations throughout Australia. We suggest using caution and use this resource as a starting point or guide rather to gain foundational understandings of how to manage behaviour in an Indigenous context. Credit: Images taken from the school websites

Findings from Comparing Indigenous and Non-Indigenous School Behaviour Management Plans Less concerned with the approach and more so about the relationship, respect, identity, cultural awareness and alignment between the students and the teacher. Basically – this resource addresses the basic notion of ‘content students, content teacher’

Flip the Deficit Model Take a strengths based approach to behaviour. This means using preventative measures, providing positive praise and encouraging a growth mindset attitude to themselves. Korff (2015) suggests teachers must “reach them and get them interested in learning, teachers must leave textbook solutions behind”. This means approaching behaviour from a bottoms up approach. An investment must be made early on before any learning can take place (Korff, 2015). Throughout this resource we will uncover some fundamental principles to ensuring behaviour management supports the wellbeing of the teacher and the students. Firstly, consideration to behaviour requires consideration to the holistic needs of the student. It begins before the student sets foot in the classroom. Follow the link for an inspiring motivational video to inspire both the teacher and students to believe in themselves. Instead of seeing obligation and effort, see opportunity to grow and improve. : https: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=Aj. Z 0 Kb. Jcav 0

Inspire Yourself and then Inspire them too! As teachers we know learning is infectious. But. . this is conditional on interest and engagement. If you aren’t positive, enthusiastic and inspired, how can they be? Improve your wellbeing by improving your attitude. Watch these must see Tedx Talks! What All Students Need to Hear : https: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=-O 7 v 4 EJjx-g Why I Teach: https: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=p. Znh. WEKd. Jsg What Adults Can Learn from Kids: https: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=TN 79 Qyddsf 0 How little people can make a big difference (The Buddy Bench): https: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=V 7 Z-Hq-xvx. M

Classroom Management Considerations: • The impact and implications of history • Social factors and life stressors • Student responsibility • Cultural modifications (8 Ways Application) • Teacher personality and identity • Strong relationships and attendance • Disengagement • Control, compliance and autonomy • High expectations • Confrontation • Rewards and discipline • Shame • Humour and fun

Who is in my Classroom? Approximately one-in-five Australians will experience some form of behavioural or emotional problems during childhood and adolescence. • These problems can include: internalising disorders, where behaviours are often directed inwards towards the self (e. g. anxiety, depression, withdrawal) or externalising disorders, where behaviour is directed outwards away from the self (e. g. aggression, conduct problems, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), delinquency). • Often such disorders can be comorbid difficult to distinguish or define. (Example: ADHD could be more difficult to diagnose in combination with a depressive order such as bipolar which may present with the same symptoms. This occurs in 13 to 27 per cent of cases of ADHD, with the comorbidity as high as 60 per cent in in certain instances (Brunsvold et al, 2008). • “Anxiety, depression, conduct disorder and ADHD are some of the most common behavioural and emotional problems observed in children and young people” (Sawyer et al, 2001). • The Western Australian Aboriginal Child Health Survey (WAACHS), conducted a study into mental health and social and emotional wellbeing among Aboriginal children and youth. The findings demonstrated a higher overall rate (26 % compared to 17 %) of mental health incidents than Non-Aboriginal youth between 4 -11. (Zubrick et al, 2005) • 21% of Aboriginal 12– 17 year-olds are at risk statistically of developing a mental health complaint compare to 13% of Non-Aboriginal youth. • High stress rates are recorded for Aboriginal students given the many life stressors faced. (Zubrick et al, 2005) • Aboriginal youth generally have high resiliency levels and strengths however they are more susceptible to behavioural and emotional problems (Zubrick et al, 2005). These factors all play a role in increasing the stress and responsibilities of teachers and creates mental health implications. Addressing the social emotional learning needs of the students is a mutually benefitting exercise. • (Walker, Robinson, Adermann, Campbell, 2014; Malin, 1990; and Harrison, 2011)

Why is this Significant? THE STUDENT: • The life pathways for young Indigenous Australians are often fraught with behavioural and emotional disruptions. • These are caused not just from socioeconomic factors but also due to other factors such as demographics or clinically significant internalising or externalising problems which are predictors for mental health difficulties in adulthood. 4 • These disruptions also predict: Ø high school non-completion; Ø physical health problems; Ø drug and alcohol misuse; Ø marital difficulties; Ø increased mortality; and, Ø involvement in the criminal and justice system. It is imperative not to make biased assumptions or judgements based on stereotypes. The role of the teacher is not to go in with a ‘these kids needs saving’ attitude. Many communities do not form a part of these stereotypes. It is considered an honour to work alongside and within these communities. Misconceptions can be easily made when making generalisations. The best advice is to engage with research, create a generalised understanding of the factors at play and go in with an open mind attitude towards building relationships. ‘Seek first to understand then be understood’. Impact on Teacher Identity THE TEACHER: We have established the link between behaviour (and classroom) management to the wellbeing of the teacher. It is therefore important to consider the issues impacting the students wellbeing which disrupts their behaviour and then finding strategies to mitigate this in turn benefitting the wellbeing of the students and the teacher. Teaching is an altruistic profession requiring a commitment to constantly reviewing and building competencies and flaws and all the while maintaining a healthy wellbeing. In order to provide a holistic education to students which supports the needs of the whole child not merely the academics, requires the teacher to have a strong sense of identity and wellbeing in themselves. Coombs (cited in Collier & Donnelly, 1984, p 20) states “your emerging professional teacher identity (which is interconnected to your personal identity) will both influence and be influenced by your actual teaching”. Zemblyas (2003, p. 223) adds “emotions inform and define identity in the process of becoming. You need to be able to identify the things you do well, the qualities that you possess and that you will need to develop’. “Teachers’ identity experiences are central to their practice and commitment as professionals” (Day, Elliot & Kingston, 2005; Gibbs, 2006). A sense of personal and professional identity are inextricably linked (Gibbs, 2006; Palmer, 1993) As Gibbs (2006, p. 77) writes “teachers who have deep knowledge about themselves as people and as teachers show a sense of security in their personal and professional identities”. (Walker, Robinson, Adermann, Campbell, 2014; Harrison, 2011; and Hudspith, 1997)

The Impact and Implications of History • Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander history is fraught with horror stories and pain such as that caused by the Stolen Generations. It is important to acknowledge these events and promote reconciliation. However, this should not allow students to misbehave. It is important for expectations to remain high and to aim for a reconciled future (SMH, 2008). • Some families of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander heritage have ill feelings towards school in relation to history. They also may not want the Stolen Generations to be included in the curriculum due to an ancestral connection and may prefer for this to be taught at home(Korff, 2015). • Korff (2015) states “effects of the Stolen Generations still have implications on each student’s life. When teaching about this chapter, teachers need to protect students’ privacy and not expect them to talk about their personal stories” • It is important strategies are arranged to strengthen relationships in the community an establish a safe learning environment including promoting reconciliation and setting expectations. Key ideas for implementing this can be found on the website. This is about teaching students to walk in two worlds (Walker, Robinson, Adermann, Campbell, 2014; Harrison, 2011; and Burney, 2000)

How to Identify a Behavioural Problem Accurately assessing and diagnosing behavioural and emotional issues is problematic in general. There are further factors when the student is of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Island descent. 13 • Concerns relate specifically to issues of Ø Bias; Ø Validity; and Ø Reliability reflected through the use of culturally biased assessment tools; - inappropriate comparison of data; - a poor relationship between the assessor and the participant; - the assessment setting; - whether similar performance is seen in the cultural context; - and recognition of cultural factors such as culture-bound syndromes or differences in conceptualisation of mental health. (Walker, Robinson, Adermann, Campbell, 2014) “Several authors argue that any assessment is culturally biased unless it takes into account all potential factors regarding the development and maintenance of the problem and the impact on any intervention. We need to acknowledge the critical importance of family and identity issues and the possible physical health and social and environmental factors that may complicate a diagnosis” (Walker et al, 2014). This is beyond the scope of this resource. It is suggested the school and mental health professionals should be involved in this process. For further reading, please see (see Chapter 13 in Schultz and Walker and colleagues in Walker et al (2014)) or contact your school to seek clarification on the process and involving relevant stakeholders. •

What Next? How? Supporting Aboriginal youth with behavioural and emotional disruptions should start with an understanding of influences on their social emotional wellbeing from an individual, family, community and structural/systems perspective. • This ensures the holistic needs of the students social emotional wellbeing are met and is likely to result in greater success academically and behaviourally both improving the wellness of the individual and the teacher (and of course the wider schooling and societal community). Individual factors (student) including: Ø self-esteem; Ø Resilience; Ø emotional and cognitive development • At a system (school) level : Ø There is a contemporary focus on improving mental health services for Aboriginal families. This stems from government support implementing wellbeing programs in schools from a macro level through to the micro level (the teacher in the classroom) to address the holistic needs of students. Ø Other influences from the Australian government include promoting mental health through the creation of such resources and initiatives as Mind. Matters and Kids. Matter. Ø Schools are not only seen as a frontline barrier to prevention of mental health issues but also pivotal in the identification and referral process. (Walker, et al 2014; AUSINET, 2008; and MCEEDYA, 2013)

Social Factors and Life Stressors The Western Australian Aboriginal Child Health Survey (WAACHS) linked clinically significant emotional or behavioural difficulties to a number of major life stress events experienced in the previous 12 months: • “family and household factors, specifically dysfunctional families and poor quality parenting; • being in the care of a sole parent or other carers; • having lived in five or more homes; • being subjected to racism in the past six months; • physical ill health of the child and carers; • speech impairment; • severe otitis media; • vision problems; • carer access to mental health services; and • substance misuse” (Zubrick et al, 2005) Many students are faced daily with situations of domestic violence, alcohol abuse and frequently cause emotional issues by their mid-teens. Teachers can mitigate this risk through the provision of a safe learning environment and classroom climate “which cares for the academic and social needs of the students develops trust and teaches them they are valued. Many Aboriginal kids are not taught values at home. If teachers spend half an hour teaching basic norms they get much more control over their students. There is a lack of positive role models for Aboriginal students, especially boys who have no father figures in their lives through death or separation. They need basic strategies for their immediate needs, for example extra attention, food or a talk about what happened the previous night at home” Korff (2005). •

Student Responsibility • Give students more chances (Korff, 2015) • Many behavioural problems can be managed by taking the time to listen and giving students a “second, third and forth” chance (Korff, 2015). • Aboriginal students are more autonomous by nature. As the teacher, an understanding and tolerance of such factors can assist in firm boundaries and also realistic expectations. (Korff, 2015).

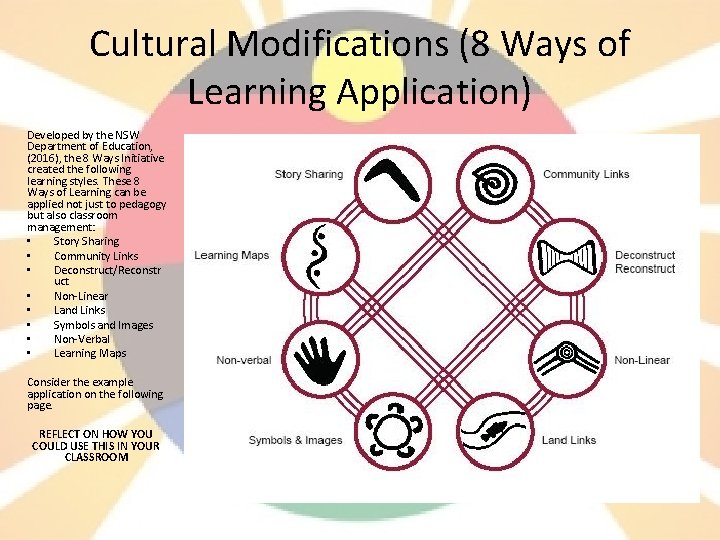

Cultural Modifications (8 Ways of Learning Application) Developed by the NSW Department of Education, (2016), the 8 Ways Initiative created the following learning styles. These 8 Ways of Learning can be applied not just to pedagogy but also classroom management: • Story Sharing • Community Links • Deconstruct/Reconstr uct • Non-Linear • Land Links • Symbols and Images • Non-Verbal • Learning Maps Consider the example application on the following page. REFLECT ON HOW YOU COULD USE THIS IN YOUR CLASSROOM

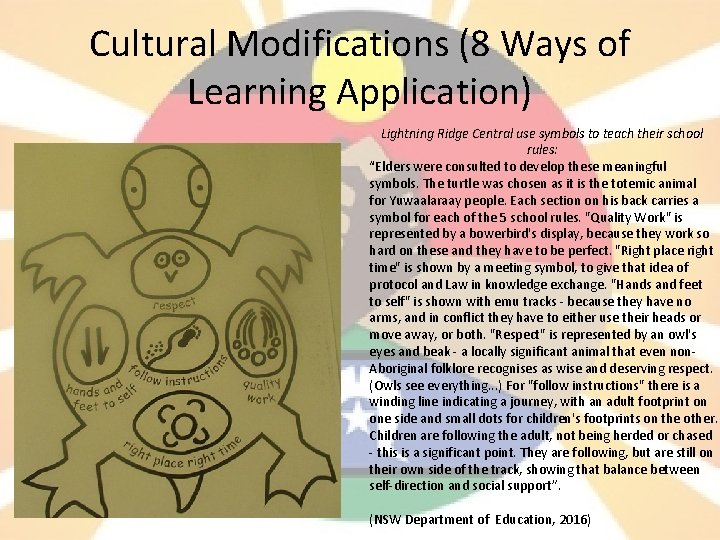

Cultural Modifications (8 Ways of Learning Application) Lightning Ridge Central use symbols to teach their school rules: “Elders were consulted to develop these meaningful symbols. The turtle was chosen as it is the totemic animal for Yuwaalaraay people. Each section on his back carries a symbol for each of the 5 school rules. "Quality Work" is represented by a bowerbird's display, because they work so hard on these and they have to be perfect. "Right place right time" is shown by a meeting symbol, to give that idea of protocol and Law in knowledge exchange. "Hands and feet to self" is shown with emu tracks - because they have no arms, and in conflict they have to either use their heads or move away, or both. "Respect" is represented by an owl's eyes and beak - a locally significant animal that even non. Aboriginal folklore recognises as wise and deserving respect. (Owls see everything. . . ) For "follow instructions" there is a winding line indicating a journey, with an adult footprint on one side and small dots for children's footprints on the other. Children are following the adult, not being herded or chased - this is a significant point. They are following, but are still on their own side of the track, showing that balance between self-direction and social support”. (NSW Department of Education, 2016)

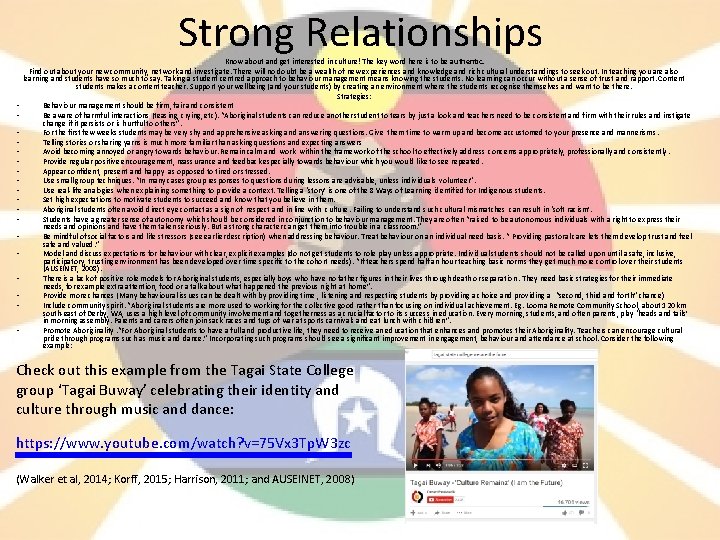

Strong Relationships • • • • • Know about and get interested in culture! The key word here is to be authentic. Find out about your new community, network and investigate. There will no doubt be a wealth of new experiences and knowledge and rich cultural understandings to seek out. In teaching you are also learning and students have so much to say. Taking a student centred approach to behaviour management means knowing the students. No learning can occur without a sense of trust and rapport. Content students makes a content teacher. Support your wellbeing (and your students) by creating an environment where the students recognise themselves and want to be there. Strategies: Behaviour management should be firm, fair and consistent Be aware of harmful interactions (teasing, crying, etc). “Aboriginal students can reduce another student to tears by just a look and teachers need to be consistent and firm with their rules and instigate change if it persists or is hurtful to others”. For the first few weeks students may be very shy and apprehensive asking and answering questions. Give them time to warm up and become accustomed to your presence and mannerisms. Telling stories or sharing yarns is much more familiar than asking questions and expecting answers Avoid becoming annoyed or angry towards behaviour. Remain calm and work within the framework of the school to effectively address concerns appropriately, professionally and consistently. Provide regular positive encouragement, reassurance and feedback especially towards behaviour which you would like to see repeated. Appear confident, present and happy as opposed to tired or stressed. Use small group techniques. “In many cases group responses to questions during lessons are advisable, unless individuals volunteer”. Use real-life analogies when explaining something to provide a context. Telling a ‘story’ is one of the 8 Ways of Learning identified for Indigenous students. Set high expectations to motivate students to succeed and know that you believe in them. Aboriginal students often avoid direct eye contact as a sign of respect and in line with culture. Failing to understand such cultural mismatches can result in ‘soft racism’. Students have a greater sense of autonomy which should be considered in conjunction to behaviour management. They are often “raised to be autonomous individuals with a right to express their needs and opinions and have them taken seriously. But a strong character can get them into trouble in a classroom. ” Be mindful of social factors and life stressors (see earlier description) when addressing behaviour. Treat behaviour on an individual need basis. “ Providing pastoral care lets them develop trust and feel safe and valued. ” Model and discuss expectations for behaviour with clear, explicit examples (do not get students to role play unless appropriate. Individual students should not be called upon until a safe, inclusive, participatory, trusting environment has been developed over time specific to the cohort needs). “If teachers spend half an hour teaching basic norms they get much more control over their students (AUSEINET, 2008). There is a lack of positive role models for Aboriginal students, especially boys who have no father figures in their lives through death or separation. They need basic strategies for their immediate needs, for example extra attention, food or a talk about what happened the previous night at home”. Provide more chances (Many behavioural issues can be dealt with by providing time , listening and respecting students by providing a choice and providing a “second, third and forth” chance) Include community spirit. “Aboriginal students are more used to working for the collective good rather than focusing on individual achievement. Eg. Looma Remote Community School, about 120 km south-east of Derby, WA, uses a high level of community involvement and togetherness as a crucial factor to its success in education. Every morning, students, and often parents, play ‘heads and tails’ in morning assembly. Parents and carers often join sack races and tugs of war at sports carnivals and eat lunch with children”. Promote Aboriginality. “For Aboriginal students to have a full and productive life, they need to receive an education that enhances and promotes their Aboriginality. Teachers can encourage cultural pride through programs such as music and dance. ” Incorporating such programs should see a significant improvement in engagement, behaviour and attendance at school. Consider the following example: Check out this example from the Tagai State College group ‘Tagai Buway’ celebrating their identity and culture through music and dance: https: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=75 Vx 3 Tp. W 3 zc (Walker et al, 2014; Korff, 2015; Harrison, 2011; and AUSEINET, 2008)

Attendance and Behaviour Create a classroom the students don’t want to stay away from • Attendance should be welcoming and praised. • Develop strong home school relationships which extend to the community to foster a warm connection promoting school as valuable and positive. • Students who have poor attendance rates and attitudes to school are less likely to participate positively with expectations set in the classroom. They need to see value in what they are doing. “Encouraging positive school experiences is central to the process of lifting both achievement and retention rates among Aboriginal students need to view school as rewarding, enjoyable, and as a learning environment encouraging active engagement in ongoing educational opportunities” (WAPPA, 2012). • Poor attendance creates a poor outlook and potential for opportunities. • “Non-attendance at school remains perhaps the most severe manifestation of the dysfunctional relationship between school and Aboriginal students. Non-attendance becomes a pattern that is hard to break, especially if triggered by school-based confrontation” (WAPPA, 2012). • The home school disconnect has a significant impact on a students positive identity of themselves and their prospects. Development of “positive self-identities as students before improved participation and retention could be achieved. This requires a school environment where students from a supportive home environment had a sense of belonging, where teachers have positive expectations of student success and where curriculum is perceived by the students to be relevant” (WAPPA, 2012) When considering the wellbeing of the teacher and the risk imposed by unsuccessful behaviour management, the following quotes provide some food for thought: “The impact on educational and behavioural management outcomes in schools of the inability to engage Aboriginal students into the learning process, can be attributed in large part to the lack of success enjoyed by Aboriginal students. The inability to read and participate fully in academic activities by a significant number of Aboriginal students, is an inhibiting factor to Aboriginal education participation, success, school attendance and retention” (WAPPA, 2012). “Clearly, the initial focus in developing strategies for maximising the potential educational opportunities for Aboriginal students, is linked to engaging in regular attendance. Schools should have consistent behaviour management and discipline programs and an absence of put-downs, racial discrimination and negative misconceptions about learning potential in students. Teachers can reduce conflict and increase student attendance, engagement and retention by employing culturally appropriate strategies, that is, interactional processes that accommodate the student's culture and result in his/her perception of acceptance and understanding in the classroom” (WAPPA, 2012).

Disengagement as a Result of EAL/D • • Disengagement due to language barriers can be a strong indicator or behavioural disruptions and disengagement from school. Indigenous students often face English as a second, third, fourth or even foreign language Teachers should explain ideas in more concrete ways and approach topics from alternate angles as well as providing real life context through stories. “Learning to read and write requires the brain to be neurologically developmentally primed. ” (Koori Mail, n. d p 54) Children’s brains need to be stimulated in the first language that they speak. ” Bilingual programs and textbooks help Aboriginal children to live in two worlds and improve literacy rates. This may mean that you teach meanings using both languages, say hello, goodbye etc in the native tounge, use local words for group names, tell local stories, allow students to explain concepts in their first language and so on. Incorporating , learning and being respectful of the Indigenous dialogue specific to your area is important and should not be overlooked as a means of getting involved in the community, showing respect and developing rapport. However, your role in most Indigenous schools is first and foremost to model and use consistent and quality English to help students develop these skills themselves. We suggest looking into the practices of the school you are in and asking other staff what the protocol is. (Harrison, 2011; and Korff, 2015)

High Expectations • • • Don’t expect Indigenous students to underperform either in the behavioural or academic sense. Studies have shown that when Aboriginal student numbers are low, teachers have been known to ignore, expect low results or victimise them. This is more then setting high expectations in learning. This is about reaching out to the students to support them to participate, develop resilience and push through when they feel like giving up. Teachers can do this by having firm, fair, consistent boundaries and expectations in relation to behaviour which are collaboratively decided and clearly communicated. Case Studies • • “I want them to reach for the stars, ” (Principal Paul Eaglestone from Looma Remote Community School in WA). “We’re all about student gain. I prefer high targets, even if sometimes students do well but don’t quite get there “ (ABC, 2016). “I give the students examples, ” explains Len Yarran from Balga Senior High School (WA). “I tell them there are people who came from alcoholic households, suicides in their family, backgrounds where there was no hope, and they have changed their lives. Some of them are in really influential positions” (The Australian, 2014). “I dreamt big, ” says Aboriginal gold medal winner and politician Nova Peris. “Most people would have looked at an Aboriginal girl from the Territory, with its statistics of alcohol abuse, youth suicide, domestic violence, imprisonment rates and substandard education, and point to every reason why I should not succeed. But I was determined to be successful” (Koori Mail, n. d). Sky News international editor and Wiradjuri man, Stan Grant, remembers: “Aboriginal kids like me were too often denied opportunity, ignored or held captive to the low expectations of others. Indeed at age 14 I, along with my black cousins and mates, was encouraged to leave school, our principal said there was no meaningful place for us” (The Australian, 2014). (Korff, 2015)

Rewards and Consequences • • • Include community spirit and collaborative rewards for good as well as individual recognition. The concept of ‘what can the group achieve collectively’. Rewards and consequences are often specific to your teaching context. Check out the examples included from the three same schools at the end of this Power. Point and request copies of policy documents for your own school. Use the rewards (either intrinsic or extrinsic) and consequences to the advantage and needs of the class and the teacher. As a guide, your classroom management should consist of a rough balance between 50% positive praise and encouragement and 50% redirection and consequences. • Real life examples Looma Remote Community School, about 120 km south-east of Derby, WA, uses a high level of community involvement and togetherness as a crucial factor to its success in education. Every morning, students, and often parents, play ‘heads and tails’ in morning assembly. Parents and carers often join sack races and tugs of war at sports carnivals and eat lunch with children (ABC, 2016). Some schools (such as Tagai State College) use a collective reward system involving tickets in a draw given out based on attendance to encourage the students to come to school to possibly win an educational aid such as an Ipad. (Walker et al, 2014; Harrison, 2011)

Tips to Remember! • • • • Avoid confronting students Catch children being good Every child has strengths Parents only want what is best for their children It is better to understand a little than misunderstand a lot Invest time in preventing bad behaviour Perseverance is the key They yearn for belonging and to be understood Avoid shaming students Use humour (NOT sarcasm) to engage and build rapport Can be slow to respond to requests Non-compliance is often acceptable at home Avoid confrontations Use group rewards (Harrison, 2011; Munns, 1998)

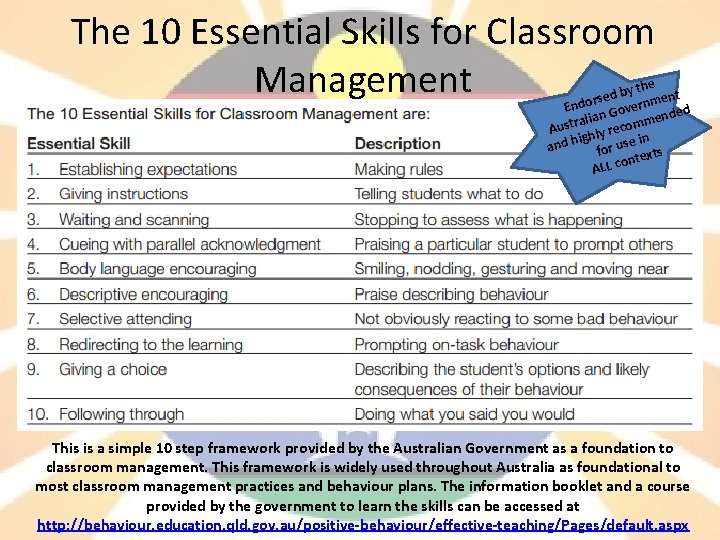

The 10 Essential Skills for Classroom Management e by th ent d e s r Endo Governm ded men alian Austr hly recom ig in and h for use ts ntex o c L AL This is a simple 10 step framework provided by the Australian Government as a foundation to classroom management. This framework is widely used throughout Australia as foundational to most classroom management practices and behaviour plans. The information booklet and a course provided by the government to learn the skills can be accessed at http: //behaviour. education. qld. gov. au/positive-behaviour/effective-teaching/Pages/default. aspx

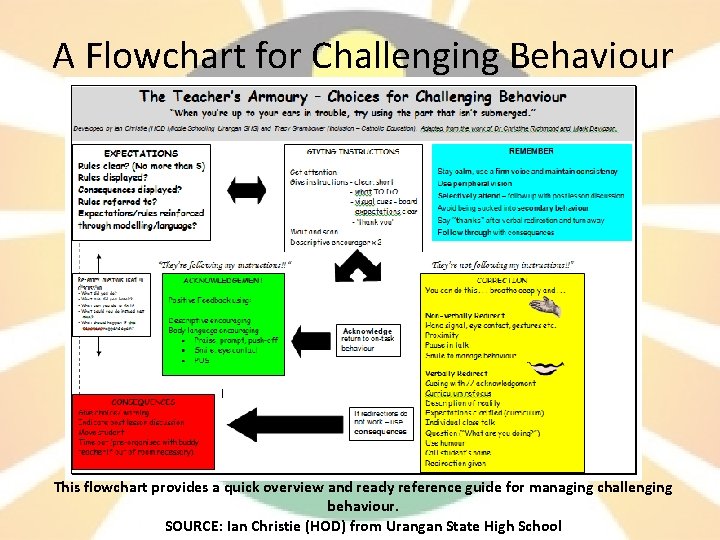

A Flowchart for Challenging Behaviour This flowchart provides a quick overview and ready reference guide for managing challenging behaviour. SOURCE: Ian Christie (HOD) from Urangan State High School

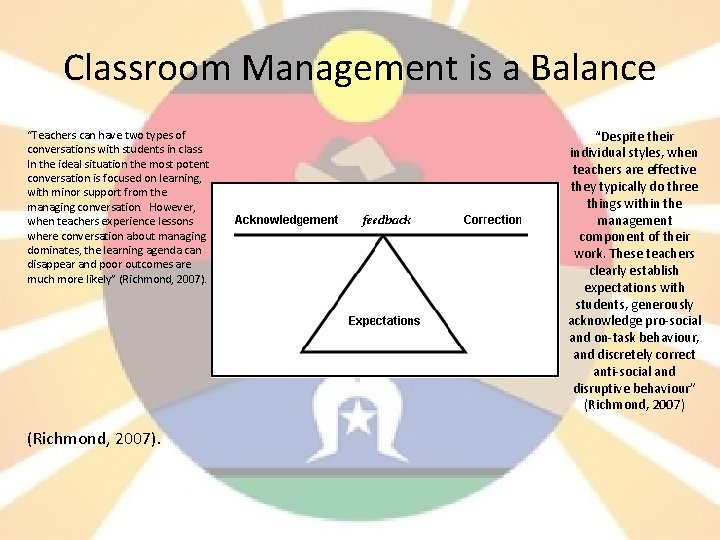

Classroom Management is a Balance “Teachers can have two types of conversations with students in class. In the ideal situation the most potent conversation is focused on learning, with minor support from the managing conversation. However, when teachers experience lessons where conversation about managing dominates, the learning agenda can disappear and poor outcomes are much more likely” (Richmond, 2007). “Despite their individual styles, when teachers are effective they typically do three things within the management component of their work. These teachers clearly establish expectations with students, generously acknowledge pro-social and on-task behaviour, and discretely correct anti-social and disruptive behaviour” (Richmond, 2007)

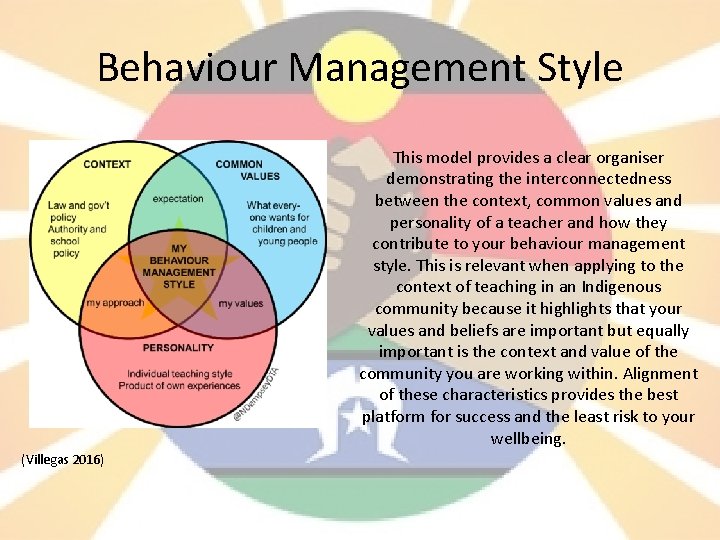

Behaviour Management Style This model provides a clear organiser demonstrating the interconnectedness between the context, common values and personality of a teacher and how they contribute to your behaviour management style. This is relevant when applying to the context of teaching in an Indigenous community because it highlights that your values and beliefs are important but equally important is the context and value of the community you are working within. Alignment of these characteristics provides the best platform for success and the least risk to your wellbeing. (Villegas 2016)

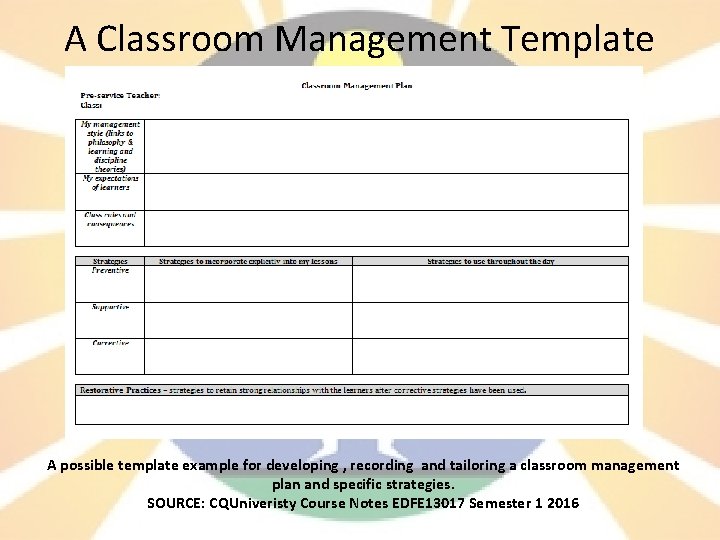

A Classroom Management Template A possible template example for developing , recording and tailoring a classroom management plan and specific strategies. SOURCE: CQUniveristy Course Notes EDFE 13017 Semester 1 2016

Key Ideas Summarised • • • • Be cool, calm, firm, fair and consistent. Invest time into setting up a safe, harmonious learning environment. Quality relationships are equally important as quality pedagogy (learning won’t occur until these are firmly established between the teacher, students, parents/carers and the community) Avoid disengagement by being mindful of triggers and have strategies in place. Don’t allow students to disengage due to behaviour and ensure high expectations are maintained for all students. All students should be participating, involved and provided with attention and recognition Work to boost attendance by strengthening relationships, rapport and classroom climate Always avoid shaming Be sensitive of the past and promote reconciliation through practice Avoid confrontation , heavy discipline, being controlling or authoritarian and backing students into a corner. Return to a situation after providing cool down time. Provide positive praise and encouragement as much as possible Identify harness and encourage students strengths Involve parents wherever possible and provide good news regularly about student learning Invest time in preventing misbehaviour Don’t expect or demand immediate conforming or compliance. Expect to develop this over time in collaboration with the needs of the students (many experience differing levels of control, compliance or autonomy outside of school – it is common for these traits to be encouraged or expected which will then translate into the classroom) Encourage group rewards rather than individual Be mindful of autonomy and non-compliance outside of school and make allowances and extra time for responding Use humour to see the funny side of things (including yourself). Avoid sarcasm or put downs

Reflection Time/Self Audit Read and reflect on the questions listed below. Consider why/why not or backing up responses with reasons when responding. • • • • • • What are your ideas so far? Write a reflective statement on how you think behaviour management can be a risk or protective factor to teacher wellbeing and why? What do I know about each of the students in my class? Am I differentiating for the needs of all students? Are the students engaged and actively participating? Is the work at an appropriate level for all the students in my class? Have I set high expectations underpinned by a supportive environment? Do my students understand what I am asking? What have I done to establish a safe learning environment and is it effective? Identify what steps I am undertaking to ensure my pedagogy is culturally appropriate and sensitive. Is my approach to behaviour management firm, fair and consistent? Are my expectations achievable and realistic? Am I providing options and choice? Am I happy with my classroom management? Is my classroom somewhere my students would want to be? Can my students recognise themselves and their identity in my classroom? Do I know where to seek assistance or find information? Am I developing and nurturing relationships within the classroom and community? What could I do to improve any of the areas mentioned in this presentation? Is what I am doing the best I can do? Have I considered the links between my wellbeing and behaviour (or classroom) management? Where can I go from here? What will I do? Who can support me to achieve success?

Further Information Website and Resources Check out the free resources and regular webinars with experts available on our website: Beyondteachers. weebly. com Live Chat We offer a live collaborate style on-line chat every Thursday evening between 6: 00 pm – 9: 00 pm where an experienced Indigenous teacher will be available to assist with any further questions or queries that you may have in relation to Indigenous learning styles and pedagogy

Source: http: //www. cherbourss. eq. edu. au/

Source: http: //www. cherbourss. eq. edu. au/

Source: http: //www. cherbourss. eq. edu. au/

Source: http: //www. cherbourss. eq. edu. au/

Source: http: //www. cherbourss. eq. edu. au/

Source: https: //yarrabahss. eq. edu. au/Pages/default. aspx

Source: https: //yarrabahss. eq. edu. au/Pages/default. aspx

Source: https: //yarrabahss. eq. edu. au/Pages/default. aspx

Source: https: //yarrabahss. eq. edu. au/Pages/default. aspx

Source: https: //yarrabahss. eq. edu. au/Pages/default. aspx

Source: https: //yarrabahss. eq. edu. au/Pages/default. aspx

Source: https: //yarrabahss. eq. edu. au/Pages/default. aspx

Source: https: //yarrabahss. eq. edu. au/Pages/default. aspx

Source: https: //tagaisc. eq. edu. au/Pages/default. aspx

Source: https: //tagaisc. eq. edu. au/Pages/default. aspx

Source: https: //tagaisc. eq. edu. au/Pages/default. aspx

Source: https: //tagaisc. eq. edu. au/Pages/default. aspx

Source: https: //tagaisc. eq. edu. au/Pages/default. aspx

Reference List • • • • • • • Australian Network for Promotion Prevention and Early Intervention for Mental Health (AUSEINET) (2008). Mental health promotion and illness prevention: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People. Ausinetter. 30(1): 22 -27. Boon, H. (2016). Why and how to use different teaching methods with Indigenous students. Australia Association for Research in Education (AARE). Retrieved via the web on April 2016 http: //www. aare. edu. au/blog/? p=1449 Brunsvold GL, Oepen G, Federman EJ, Akins R (2008). Comorbid Depression and ADHD in Children and Adolescents. Psychiatric Times. 25(10). Burney, L. (2000). Not Just a Challenge, an Opportunity. In M Gratton (ed). Reconciliation: Essays on Australian Reconciliation. Bookman Press, Melbourne, pp. 65 -73. Cherbourg State School. (2009). Positive Rewards System. Department of Training and Education. Retrieved via the web April 2016 from http: //www. cherbourss. eq. edu. au/Rewards. html Collier, G. and Donnelly, K. (1984), Self Esteem, Sydney: N. S. W. Education Department Day, C. , Elliot, B. , & Kingston, A. (2005). Reform, standards and teacher identity: Challenges of sustaining commitment. Teaching and Teacher Education, 21(5), 563 -57 Gibbs, C. J. (2006). To be a teacher: Journeys towards authenticity. Auckland, New Zealand: Pearson Education. Harrison, N. (2011). Teaching and Learning In Aboriginal Education. Second Edition. Oxford Univeristy Press. Australia and New Zealand. Victoria. Hudspith, S (1997). ‘Visible pedagogy and urban Aboriginal students’. In S Harris & M Malin (eds). Aboriginal education: historical moral and practical tales, Northern Territory University Press, Darwin, pp. 96 -108. Koori Mail. (n. d). 'Kids' brains 'need help', 511 p. 54 Korff, J. (2015). Teaching Aboriginal Students. Creative Spirits. Retrieved via the web on April 2016 from http: //www. creativespirits. info/aboriginalculture/education/teaching-aboriginalstudents#axzz 47 RPfh. Kq. L Malin, M (1990 a). ‘The Visibility and Invisibility of the Aboriginal Child in the Urban Classroom’. Australian Journal of Education, vol. 34, no. 3, pp. 312 -29. Malin, M (1990 b). ‘Why is Life so Hard for Aboriginal Students in Urban Classroom? ’. The Aboriginal Child at School, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 9 -29. Ministerial Council for Education, Early Childhood Development and Youth Affairs (MCEECDYA). (2013). Retrieved via the web May 2016 from: http: //www. mceecdya. edu. au/mceecdya/. Munns, G. (1998). They Just Can’t Hack That: Aboriginal Students, Their Teachers and Responses to Schools and Classrooms, in G Partington (ed). Perspectives on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Education. Social Science Press, Katoomba, New South Wales, pp. 171 -87 NSW Department of Education, (2016). Behaviour Management. Retrieved via the web on April 2016 from http: //8 ways. wikispaces. com/Behaviour+management Richmond, C. (2007). Teach More, Manage Less: A Minimalist Approach to Behaviour Management. Australia: Scholastic. http: //www. etfo. ca/Resources/e. Resources/Research. For. Teachers/Lists/Research%20 List/Disp. Form. aspx? ID=8 Sawyer. M, Arney. F, Baghurst. P, Clark. J, Graetz. B, Kosky. R, et al (2001). The mental health of young people in Australia: key findings from the child and adolescent component of the national survey of mental health and well-being. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 35(6): 806 -14. SMH, (2008). 'The school of tough love‘. Good Weekend. pp. 26. St Vincent's Hospital Sydney Limited. (2016). This Way Up. Retrieved via the web on April 2016 from https: //thiswayup. org. au/how-do-you-feel/stressed/ The Australian. (2014). 'Where all the indigenous faces? ', Dated 28/7/2014 Koori Mail. (n. d). 'Education, recognition hot topics at Garma', 482 p. 3 ABC, (2016). 'Newcastle academic slams 'Eurocentric' education for indigenous students', Newcastle. Dated 19/1/2016 Villegas, T (2016). Donald Trump is Bad for Students With Disabilities in America. Retrieved from http: //www. thinkinclusive. us/tag/special-education 2/http: //www. etfo. ca/Resources/e. Resources/Research. For. Teachers/Lists/Research%20 List/Disp. Form. aspx? ID=8 Walker, R. Robinson, M. Adermann, J. Campbell, M. (2014). Working with Behavioural and Emotional Problems in Young People. Chapter 22 Part 5. Pp 383 -398. In Working together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mental health and wellbeing principles and practice - 2 nd edition. Telethon Kids Institute, Kulunga Aboriginal Research Development Unit, Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (Australia). Retrieved via the web on April 2016 from http: //aboriginal. telethonkids. org. au/media/673991/wt-part-5 -chapt-22 -final. pdf Western Australian Primary Principals Association (WAPPA) (2012). Online Aboriginal Education. Department of Education retrieved via the web from http: //www. wappa. asn. au/oae/module 4/mod 4_part 3. html Zembylas, M. (2003). Emotions and teacher identity: A poststructural perspective. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 9(3), 213– 238. Zubrick, S. Silburn, S. Larence, D. Mitrou. G, Dalby. B, Blair. M, et al. (2005). Western Australian Aboriginal Child Health Survey. The Social and Emotional Wellbeing of Aboriginal Children and Young People. Volume 2. Perth.

- Slides: 53