SYSTEMIC FLUORIDES FLUORIDE TABLETS SALT FLUORIDATION AND MILK

SYSTEMIC FLUORIDES FLUORIDE TABLETS, SALT FLUORIDATION, AND MILK FLUORIDATION Lecture by: Dr. Pramod Yadav 1

CONTENTS • • • INTRODUCTION FLUORIDE TABLETS AND DROPS SALT FLUORIDATION MILK FLUORIDATION CONCLUSION REFERENCES 2

Introduction • When water fluoridation was first introduced in the mid 1940 s it was assumed that fluoride produced most of its cariostatic effects through preeruptive effects. • Ingestion of fluoride in the early years of life was thus considered essential for the full benefits of fluoride to be realized, and the earlier in life this ingestion started, the more complete the benefits. • It was natural, therefore, that alternative means of ingesting fluoride by infants and young children were looked for those children who did not receive fluoridated water. 3

FLUORIDE TABLETS AND DROPS 4

Effectiveness in caries prevention • During the 1950 s, the value of water fluoridation as a way of preventing caries became clear. It was recognized, however, that water fluoridation was not always possible and that a sensible alternative might be to give children an equivalent amount of fluoride as a tablet where water fluoridation is not possible. 5

• One of the first demonstrations of the value of fluoride tablets for caries prevention was given by Arnold, Mc. Clure and White (1960). • The number of years the children in this study ingested the tablets varied, but the average was 7 years. • The authors concluded that the results correspond with what has been observed in the use of drinking water containing 1 ppm F'. • Children over the age of 3 years received 1 mg F/day and this dose has formed the basis for further studies, and for individual and community prevention. 6

Deciduous teeth • Caries preventive effect was observed consistently (about 50 80% reduction) in studies where the initial age was 2 years or younger. • In a more thorough study Granath et al. (1978) suggested that while buccolingual surfaces may benefit if the commencement age is over 2 years, the effect on approximal surfaces is very much less if the commencement age is 2 years or over. • This suggests that the topical effect is greater on the more exposed buccolingual surfaces than on the less accessible approximal surfaces. 7

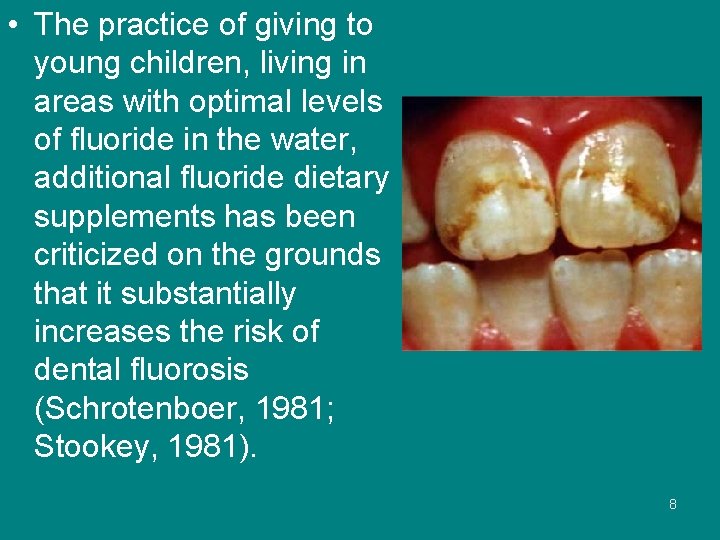

• The practice of giving to young children, living in areas with optimal levels of fluoride in the water, additional fluoride dietary supplements has been criticized on the grounds that it substantially increases the risk of dental fluorosis (Schrotenboer, 1981; Stookey, 1981). 8

Permanent teeth • The initial age of the subjects and the duration of fluoride tablet intake varied widely in the different investigations done. • In only four of the studies (Hamberg, 1971; Sch. Jtzmannsky, 1971; Aasenden and Peebles, 1974; Margolis et al. , 1975) were fluoride tablets taken from birth for at least 7 years. • Reductions ranged from 39% in Schutzmannsky's trial to 80% in the trial of Aasenden and Peebles. 9

• In the trial of Margolis and co workers the children who started taking fluoride tablets at birth showed a 58% reduction in DFT compared with only a 14% reduction in the group of children who started at the age of 4 years, suggesting the importance of ingestion in the first few years of life, before the permanent teeth erupted. 10

Prenatal • In all the trials conducted to investigate the effectiveness of the ingestion of prenatal fluoride tablets the percentage of caries reduction was greater in the children whose mothers received fluoride tablets in pregnancy. But in spite of the apparent greater benefit of prenatal fluoride, Hoskova (1968) concluded that fluoride administration should begin as soon after birth as possible, attributing the greater benefit to better home conditions in the prenatal group. 11

• Feltman and Kosel (1961) compared the caries experience of 672 children who had received (a) only prenatal supplements (162 children), (b) prenatal and postnatal supplements (228 children) and (c) only postnatal tablets from varying ages (282 children). • Prenatal fluoride appeared to confer benefit additional to that derived from postnatal fluoride exposure. 12

Fluoride-vitamin combination • Vitamin and fluoride supplementation has been combined in some preparations sold in the USA. This is convenient when both vitamins and fluoride are required. • Glenn (1979) suggested that some preparations contain 250 mg of calcium and that there was a danger that this might inactivate the fluoride. • However, examination of the results of trials showed that the effectiveness of fluoride drops/tablets is neither enhanced nor reduced by their combination with vitamins and minerals: Stookey (1981) came to the same conclusion. 13

Type of fluoride compound • The results of the three trials testing Ca. F 2 compounds are very variable (0 70% reduction); all were short term trials. • The impressive result of Krusic (1960) is surprising, since the insolubility of Ca. F 2 would obviate the likelihood of a topical effect compared with Na. F, and a systemic effect would be very unlikely to occur in this short trial in 8 15 year old children. 14

• From the three trials in which APF compounds were used, the effectiveness would appear to be no greater than that observed in the larger number of Na. F trials. • APF tablets are considerably more expensive than Na. F tablets (Driscoll et al. , 1978), and the greater salivary flow caused by the low p. H of the APF tablets is likely to reduce the concentration of fluoride around the teeth and hasten its clearance from the mouth. • It would appear that to ensure high and long lasting salivary F levels, tablets should contain Na. F rather than APF, disintegrate slowly in the mouth without being sucked, and possess as little flavour as possible, so long as the tablets are acceptable to children (Mc. Call, Stephen and Mc. Nee, 1981). 15

• Although it is desirable that fluoride tablets dissolve slowly so that teeth are bathed in high levels of fluoride for a long time, it is important to appreciate that saliva does not flow extensively around the mouth. • Weatherell et al. (1984) and Primosch, Weatherell and Strong (1986) have shown clearly that fluoride released from a tablet tends to remain highly concentrated at the site of tablet dissolution. • There was very little mixing between the sides of the mouth or between vestibules of upper and lower arches. • It would seem important, therefore, that the position of tablets in the mouth is changed regularly (Dawes and Weatherell, 1990). 16

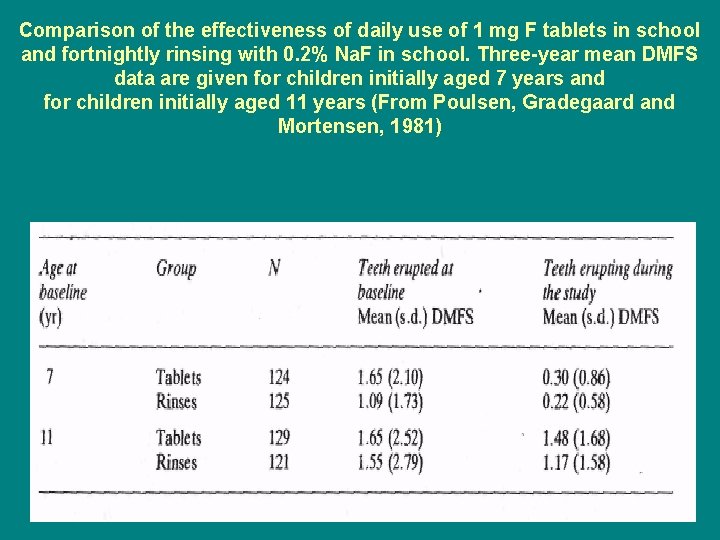

Effectiveness of fluoride tablets compared with other methods • Poulsen, Gradegaard and Mortensen (1981) compared the effectiveness of the daily use of a 1 mg. F tablet and the fortnightly rinsing with 0. 2% Na. F in a school based programme in Denmark. • The results indicated that caries increments were lower in the rinsing group than in the tablet group. • This difference was seen in both age groups and was statistically significant in teeth erupted at baseline, but not in teeth erupting during the study. 17

Comparison of the effectiveness of daily use of 1 mg F tablets in school and fortnightly rinsing with 0. 2% Na. F in school. Three-year mean DMFS data are given for children initially aged 7 years and for children initially aged 11 years (From Poulsen, Gradegaard and Mortensen, 1981) 18

Summary of effectiveness of fluoride tablets and drops • From the results of published trials it would seem that there is no doubt that the use of fluoride tablets or drops is effective in preventing dental caries in both the deciduous and permanent dentitions. • The effectiveness would seem to be greater the earlier the child begins to take the fluoride supplement from 40% to 80% reduction being expected in both deciduous and permanent dentitions if supplementation is commenced before 2 years of age. • For school based schemes the effectiveness would appear to be slightly lower and more variable (30 80% reduction) but still substantial. Na. F would appear to be the compound of choice. 19

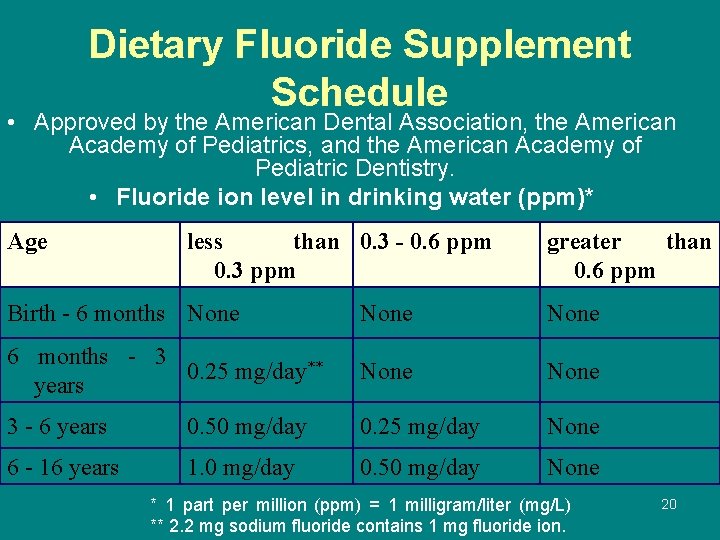

Dietary Fluoride Supplement Schedule • Approved by the American Dental Association, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. • Fluoride ion level in drinking water (ppm)* Age less than 0. 3 - 0. 6 ppm 0. 3 ppm greater than 0. 6 ppm Birth - 6 months None 6 months - 3 0. 25 mg/day** years None 3 - 6 years 0. 50 mg/day 0. 25 mg/day None 6 - 16 years 1. 0 mg/day 0. 50 mg/day None * 1 part per million (ppm) = 1 milligram/liter (mg/L) ** 2. 2 mg sodium fluoride contains 1 mg fluoride ion. 20

• It is suggested that only children living in non fluoridated areas use dietary fluoride supplements between the ages of six months to 16 years. • The objective of any systemic fluoride administration is to obtain the maximum caries preventive effect with a low risk of unacceptable enamel mottling. • As far as water fluoridation is concerned this is achieved, in temperate climates, where drinking water contains 1 ppm. F. • In the past, fluoride tablet dosages have been calculated in an attempt to duplicate the fluoride intake which occurs in people receiving optimally 21 fluoridated drinking water.

SALT FLUORIDATION 22

• Salt fluoridation is the controlled addition of fluoride, usually as sodium or potassium fluoride, during the manufacture of salt for human consumption. • With the current acceptance of fluoride's essentially topical effects, fluoridated salt controls caries through helping to maintain a constant, low level of fluoride in the intraoral environment. • The more that the various sources of salt contain fluoride i. e. salt for domestic use, salt used in restaurants, bakeries, food processing, and other institu tional food providers such as hospitals, the more effectively will the ambient levels of in traoral fluoride be maintained and the more effective will the fluoridated salt be in caries control. 23

• Fluoridated salt as a means of preventing caries was first suggested by Wespi, who was actually a gynecologist. • Wespi had first hand knowledge of the success of iodized salt, which had been initiated in Switzerland in 1922 to prevent goiter, an endemic condition in many parts of the Alpine region through the first half of this century. • Aided by his reputation as an expert on iodized salt and with a strong commitment to public health, Wespi suggested to the Board of Cantonal Health Directors in Switzerland that fluoride should join iodine as a salt additive. • The Canton of Zurich was the first to act on this suggestion, and authorized the sale of fluoridated domestic salt in 1955. This salt contained 90 mg F/kg. Most other cantons fol lowed Zurich's lead within 10 years, and as early as 1966 the sales figures showed that flu oridated salt accounted for 65% of the domestic salt market. 24

• In 1970 the Canton of Vaud, in western Switzerland, began its manufacture of fluoridated salt at 250 mg F/kg. This concentration had been suggested by Wespi and by Muhlemann, because earlier research had shown that the initial concentra tion (90 mg F/kg) was too low for the most effective cariostasis. • Vaud went even further, and required the bulk salt delivered to bakeries, restaurants, hospitals, and other institutions providing food to contain 250 mg F/kg, This was in addition to the existing program of flu oridating all domestic salt. 25

• By 1983, the initial concentration of 90 mg F/kg was raised to 250 mg F/kg for salt distributed everywhere in Switzerland except for the Canton of Basel, which has had fluoridated water since 1962. • Other countries have since followed Switzerland's lead and adopted salt fluoridation: France in 1986, Germany in 1991, Costa Rica and Jamaica in 1987. • This list is likely to grow since other countries are considering the measure. 26

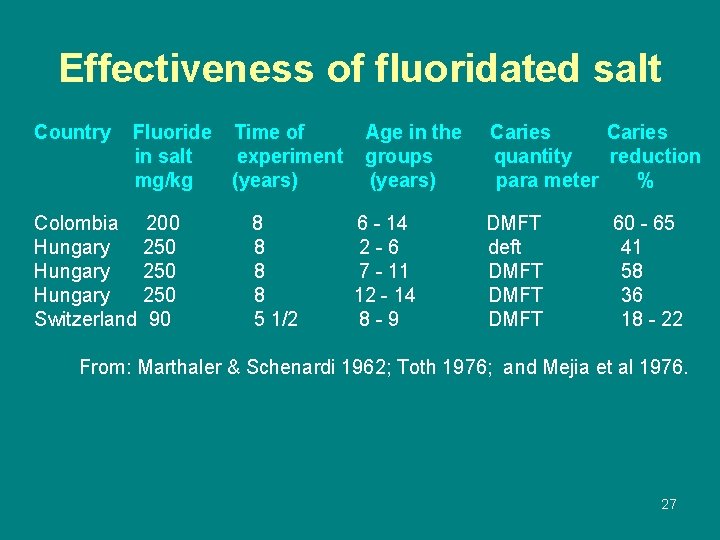

Effectiveness of fluoridated salt Country Fluoride in salt mg/kg Time of experiment (years) Age in the groups (years) Caries quantity reduction para meter % Colombia 200 8 6 14 DMFT 60 65 Hungary 250 8 2 6 deft 41 Hungary 250 8 7 11 DMFT 58 Hungary 250 8 12 14 DMFT 36 Switzerland 90 5 1/2 8 9 DMFT 18 22 From: Marthaler & Schenardi 1962; Toth 1976; and Mejia et al 1976. 27

• Conclusion : The reduction in caries experience in children between 1984 and 1995 was striking and may be a result of a combination of factors, the likeliest being the fluoridation of domestic salt. • The continued availability of fluoride toothpastes may have contributed to this reduction though data are not available to measure this. Oral health education in schools did not reach majority of the children and there were only a limited school dental service in the island. • The evidence for the efficacy of salt fluoridation is thus based on a limited number of field trials and observational studies. • Like water fluoridation, the nature of the procedure does not lend itself to randomized, double blind clinical trials. While the field trial designs i. e. where a whole community knowingly adopts a proce dure is scientifically weaker than a clinical trial, the evidence for salt fluoridation is con sistent and plausible. 28

The ideal fluoride concentration in salt • The concentration of fluoride in salt is largely based on average salt consumption. The daily intake of domestic salt in European populations has been estimated to range from 1. 5 to 3. 34 g/day so that a person consuming 2. . 25 g of the salt initially fluoridated at 90 mg F/kg would ingest only 0. 2 mg fluoride from it. 29

Feasibility in India • It is important to distribute fluoridated salt through channels used by the low socio economic strata; in these strata caries prevalence is highest and dental care is often unaffordable or neglected. • Salt fluoridation appears to be a viable method of systemic fluoride ingestion in India as its distribution can be easily monitored specially in high fluoride belts. • Moreover individual monitoring is not required as the levels are so adjusted so as to provide optimum levels of fluoride keeping in view the fact that on an average an individual consumes 5 8 gms of salt / day in India. • Also salt is freely available and is used by majority of the population. Moreover the cariostatic effectiveness is almost equal to fluoridated water, when the fluoride content of the salt is adjusted to 250 mg / kg salt. • Also salt fluoridation does not alter its colour as in case of salt 30 iodisation.

Disadvantage of Salt Fluoridation • Fluoridated salt consumption is lowest when the need of fluoride is greatest i. e. in early years of life. • The current view is that high salt consumption leads to hypertension. • Salt consumption differs from person to person. 31

MILK FLUORIDATION 32

• Milk fluoridation is the addition of a measured quantity of fluoride to bottled or packaged milk to be drunk by children. • Strongly promoted by Ziegler, an influential pediatrician, the first project with fluoridated milk began in the Swiss city of Winterthur in 1955. • Milk containing fluoride of 1. 0 mg/L was provided to 749 children aged 9 44 months, and another 553 children were included as controls. • After 6 years, substantial reductions in caries were reported for both the primary and permanent dentitions. 33

• The rationale for adding fluoride to milk is that this procedure "targets" fluoride directly to children, and thus would be less expensive than fluoridating the drinking water. • Having both fluoridated and non fluoridated milk available also maintains consumer choice. • However, despite considerable interest in many quarters, the choice of milk as a vehicle for fluoride raises questions. • The first concern was absorption, for it was shown a long time ago that while fluoride is absorbed almost as completely from milk as it is from water, the process takes considerably longer. • If fluoride acted preemptively to prevent caries that would not matter much, but in the current model of fluoride cariostasis it means that virtually no topical effect take place. • There also practical concerns, such as the considerable number of children in most countries who do not drink milk for one reason or another. 34

• There have been only a few studies on the cariostatic efficacy of fluoridated milk, and some of them were flawed in design or operation. • These and other studies reported favorable results, and increases in the fluoride content of enamel have been reported in children who consumed fluoridated milk for a year. • The study in Scotland provided 1. 5 mg F in 200 m. L of milk to the children on each school day. 35

• Few public health programs using fluoridated milk have become established, though there are reports of such programs in Bulgaria and another to begin in St. Helens, near Liverpool, in England. • However, it is hard to recommend further research into milk fluoridation in view of the large number of fluoride vehicles available today and the restricted topical effects from fluoride in milk. • In 1972, Stamm summarized the following criticisms of milk fluoridation as a public health measure: 1. Since children from the lower socioeconomic groups tend to drink the lowest amount of fresh milk, they would benefit least; 2. Any benefit ceases as an individual matures and drinks less milk; 3. Slow absorption means no topical effect. 36

Fluoridating the milk • Fluoridated milk can be produced in many different forms such as the liquid and the powder, each may be mixed with the choice of the different fluorides available. • Sodium fluoride is by far the commonly used agent for large scale production of fluoridated milk, currently being used in Bulgaria, China, Russia and Britain. • The other agents are calcium fluoride, disodium monofluorophosphate (used in Chile) and disodium silicofluoride. • Except in Chile where the fluoridated milk was in powder form, the rest of the schemes mentioned used liquid milk. 37

• To calculate the fluoride concentration, it is necessary to consider the volume of fluoridated milk consumed daily by each child. • In Britain a child received 189 ml of milk and in China each child got 250 ml milk. In Bulgaria, 200 ml is consumed daily and the fluoride requirement is 1 mg per day, the concentration of fluoride in milk is set 38 at 5 ppm.

Conclusion • The most significant message from the programme is that such health benefit can be achieved without any technical or administrative change to an already ongoing school food programme PAE. • Two different types of health benefit such as caries prevention and overall well being can be achieved by one single public health oriented programme such as fluoridated milk made freely available to all children 39

• This philosophy is in line with the Common Risk Factor approach of the WHO. • The Chilean Health Ministry has authorised JUNAEB to expand the PAE F in rural areas of the country south of IV Region allowing gradual inclusion of 215, 000 children living in these areas to benefit. 40

Conclusions • Fluoridated milk seem to keep a permanently low level of ionized fluoride within the oral cavity promoting remineralization. It is likely that this topical mechanism contributes to the caries preventive effect of fluoridated milk. However there are still a series of unanswered questions, and additional studies should be performed to determine, • the age at which it is best to start drinking fluoridated milk • for how many years it should continue • the frequency of consumption • optimum fluoride concentration to be added • anti caries effect of milk and it's products 41

REFERENCES • • • • Burt BA. Dentistry, dental practice and community. 6 th ed. New York. Elseiver. 2005. Peter S. Essentials of preventive community dentistry. Arya Publishing House. 2003. Second edition. DCI. National oral health survey. Fluoride mapping 2002 2003. Tewari A. Fluorides and dental caries. JIDA 1985 86. WHO expert committee on oral health status and fluoride use. 1994 TRS 846. Slack GL. Dental public health an introduction to community dental health. John Wright and Sons. 1981, second edition Dunning JM. Principles of dental public health. Harvard University Press. 1986; 4 th edition. Murray JJ. Fluorides in caries prevention. 3 rd ed. Mumbai, Varghese publishing house. 1999. Pine CM. community oral health. 1997. ed. Mumbai. KM Varghese company. Daly B, Watt R, Batchelor P, Treasure E. 2003. ed. New Delhi. Oxford university press. 299 313. Mc. Donagh MS. Systematic review of water fluoridation. BMJ 2000; 321: 855 59. Griffin SO. An economic evaluation of community water fluoridation. JPHD 2001; 61(2): 78 86. Susheela AK. Scientific evidence of adverse effects of fluoride. 1998 Harris NO. Primary preventive dentistry. 4 th ed. Connecticut. Appleton And Lange. 1996. 447 477. 42

• Jong AW. Community dental health. Mosby 1993. Third edition. • Achievements in Public Health, 1900 1999: Fluoridation of Drinking Water to Prevent Dental Caries. JAMA. 2000; 283: 1283 1286. • Sheila Jones, Brian A. Burt, Poul Erik Petersen, Michael A. Lennon. The effective use of fluorides in public health. Bull World Health Organ vol. 83 no. 9 Genebra 2005 • Ten Cate JM. Current concepts on theories of the mechanism of action of fluoride. Acta Odontol scand 1999; 57: 325 29. • Burt BA. Fluoridation and social equity. JPHD 2002; 62: 195 200. • Kalsbeek H. Caries experience of 15 year old children in Netherlands after discontinuation of water fluoridation. Caries Res 1993; 27: 201 5. • Newbrun E. Effectiveness of water fluoridation. JPHD 1989; 49: 279 89. • www. Unicef. org • Water fluoridation and costs of Medicaid treatment for dental decay Louisiana, 1995 1996. • Petersen PE. Effective use of fluorides for the prevention of dental caries in 21 st century: WHO approach. CDOE 2004; 32: 319 21. • John J. Clarkson and Jacinta Mc. Loughlin. Role of fluoride in oral health promotion. International Dental Journal (2000) 50, 119– 128 • Weitz A, Villa AE. Caries reduction in rural schoolchildren exposed to fluorides through a milk fluoridation program in Araucania, Chile. Caries Research. 2004; 39: 357. 43

44

- Slides: 44