Systematic Software Testing Using Test Abstractions Darko Marinov

Systematic Software Testing Using Test Abstractions Darko Marinov RIO Summer School Rio Cuarto, Argentina February 2011

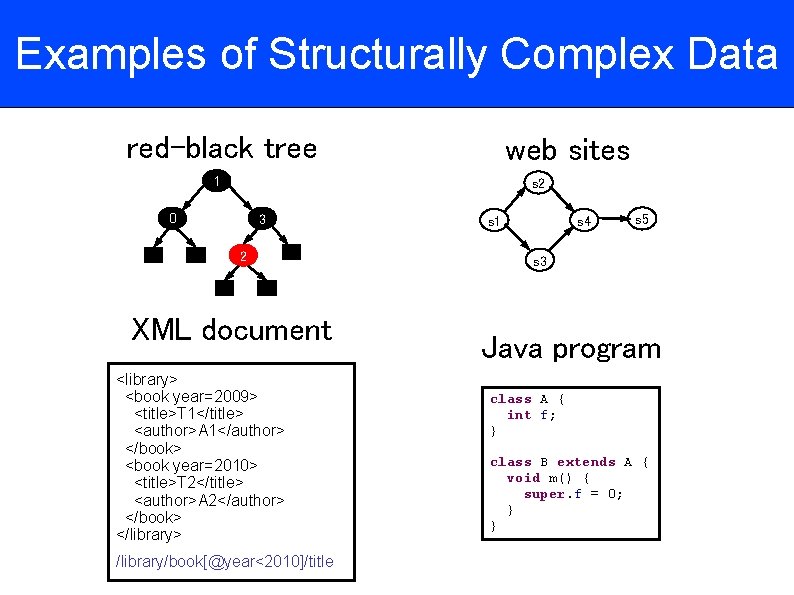

Examples of Structurally Complex Data red-black tree web sites 1 s 2 0 3 2 XML document <library> <book year=2009> <title>T 1</title> <author>A 1</author> </book> <book year=2010> <title>T 2</title> <author>A 2</author> </book> </library> /library/book[@year<2010]/title s 1 s 4 s 5 s 3 Java program class A { int f; } class B extends A { void m() { super. f = 0; } }

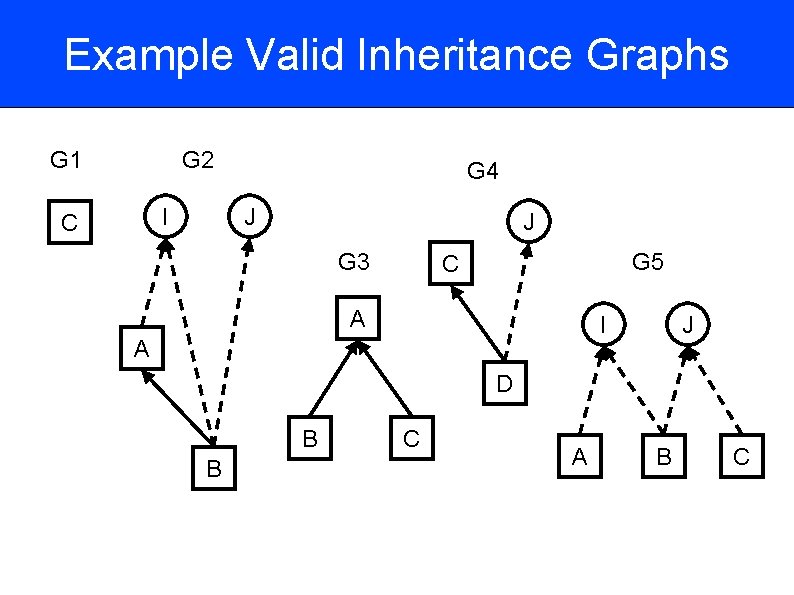

Running Example: Inheritance Graphs Java program Inheritance graph interface I { void m(); } I J interface J { void m(); } class A implements I { void m() {} } class B extends A implements I, J { void m() {} } Properties 1. DAG A 2. Valid. Java B.

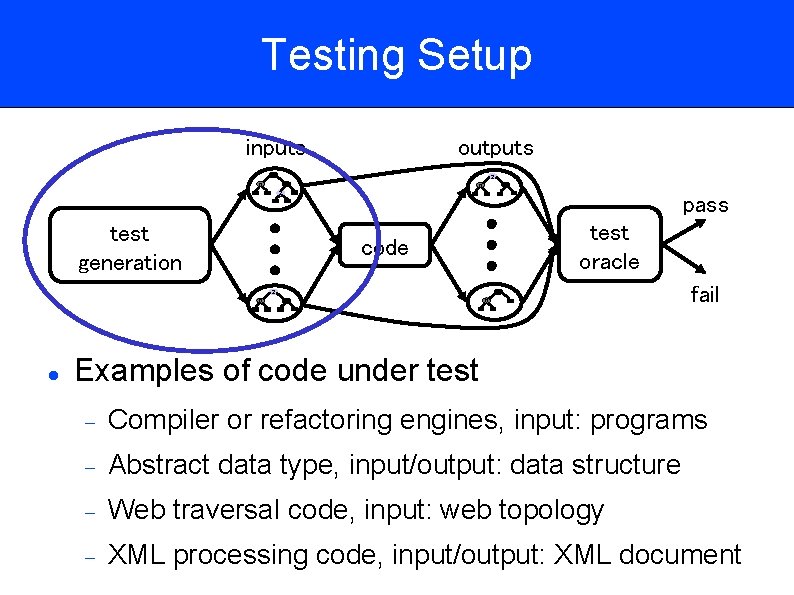

Testing Setup inputs outputs 1 2 0 3 2 pass test generation test oracle code 3 2 0 3 0 fail Examples of code under test Compiler or refactoring engines, input: programs Abstract data type, input/output: data structure Web traversal code, input: web topology XML processing code, input/output: XML document

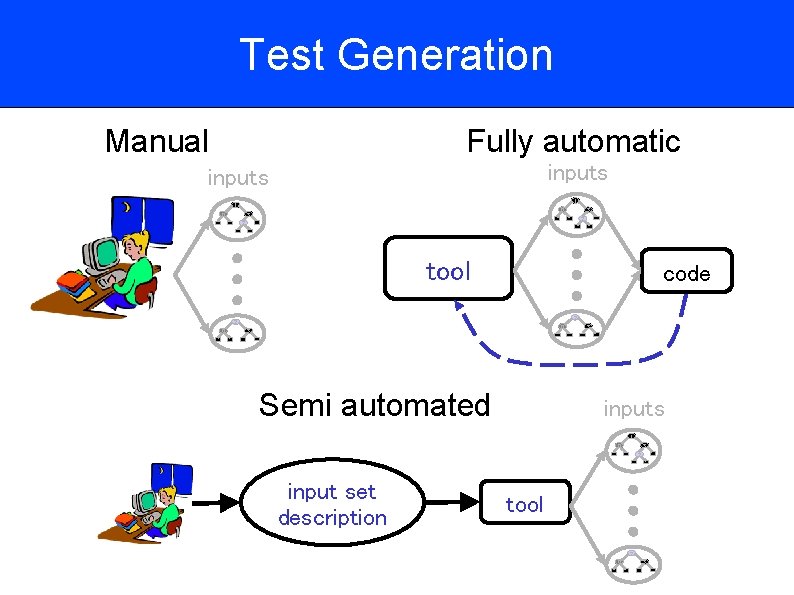

Test Generation Manual Fully automatic inputs 1 1 0 0 3 3 2 2 tool code 2 2 0 0 3 Semi automated 3 inputs 1 0 3 2 input set description tool 2 0 3

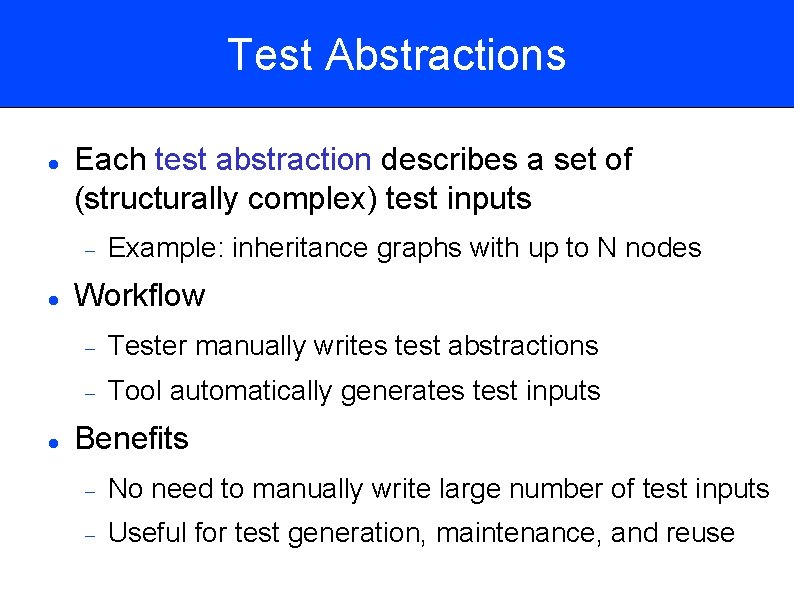

Test Abstractions Each test abstraction describes a set of (structurally complex) test inputs Example: inheritance graphs with up to N nodes Workflow Tester manually writes test abstractions Tool automatically generates test inputs Benefits No need to manually write large number of test inputs Useful for test generation, maintenance, and reuse

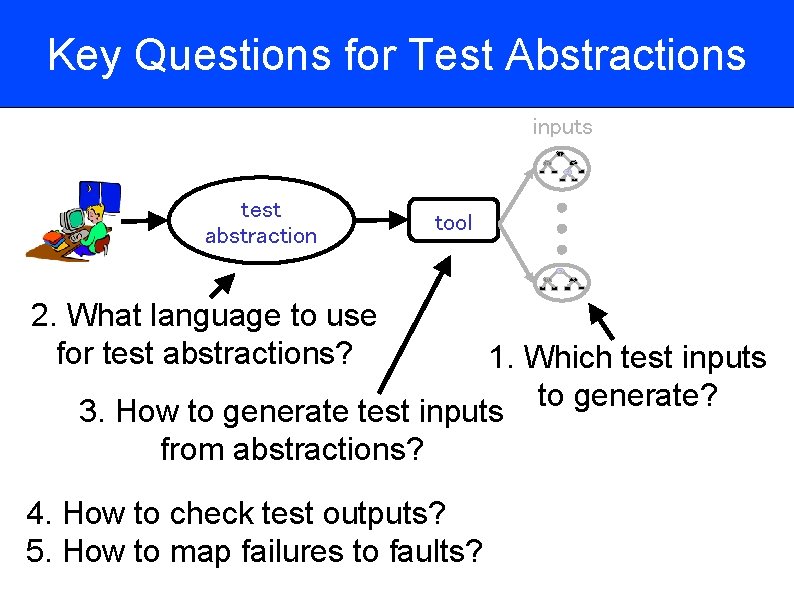

Key Questions for Test Abstractions inputs 1 0 3 2 test abstraction tool 2 0 2. What language to use for test abstractions? 3 1. Which test inputs to generate? 3. How to generate test inputs from abstractions? 4. How to check test outputs? 5. How to map failures to faults?

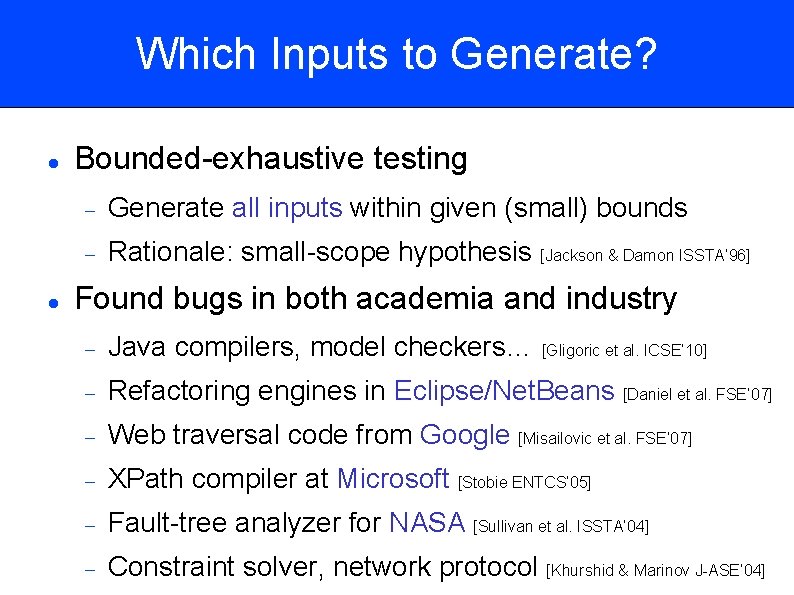

Which Inputs to Generate? Bounded-exhaustive testing Generate all inputs within given (small) bounds Rationale: small-scope hypothesis [Jackson & Damon ISSTA’ 96] Found bugs in both academia and industry Java compilers, model checkers… [Gligoric et al. ICSE’ 10] Refactoring engines in Eclipse/Net. Beans [Daniel et al. FSE’ 07] Web traversal code from Google [Misailovic et al. FSE’ 07] XPath compiler at Microsoft [Stobie ENTCS’ 05] Fault-tree analyzer for NASA [Sullivan et al. ISSTA’ 04] Constraint solver, network protocol [Khurshid & Marinov J-ASE’ 04]

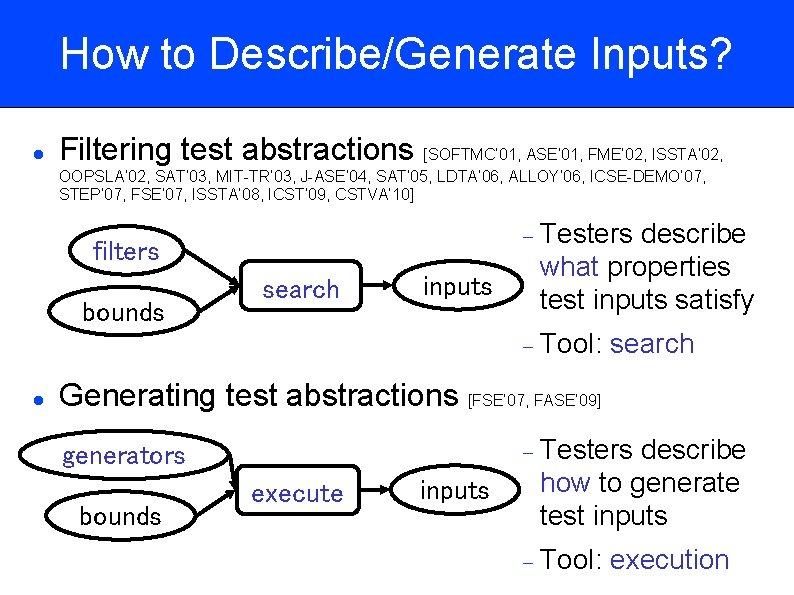

How to Describe/Generate Inputs? Filtering test abstractions [SOFTMC’ 01, ASE’ 01, FME’ 02, ISSTA’ 02, OOPSLA’ 02, SAT’ 03, MIT-TR’ 03, J-ASE’ 04, SAT’ 05, LDTA’ 06, ALLOY’ 06, ICSE-DEMO’ 07, STEP’ 07, FSE’ 07, ISSTA’ 08, ICST’ 09, CSTVA’ 10] Testers filters bounds search inputs describe what properties test inputs satisfy Tool: search Generating test abstractions [FSE’ 07, FASE’ 09] Testers generators bounds execute inputs describe how to generate test inputs Tool: execution

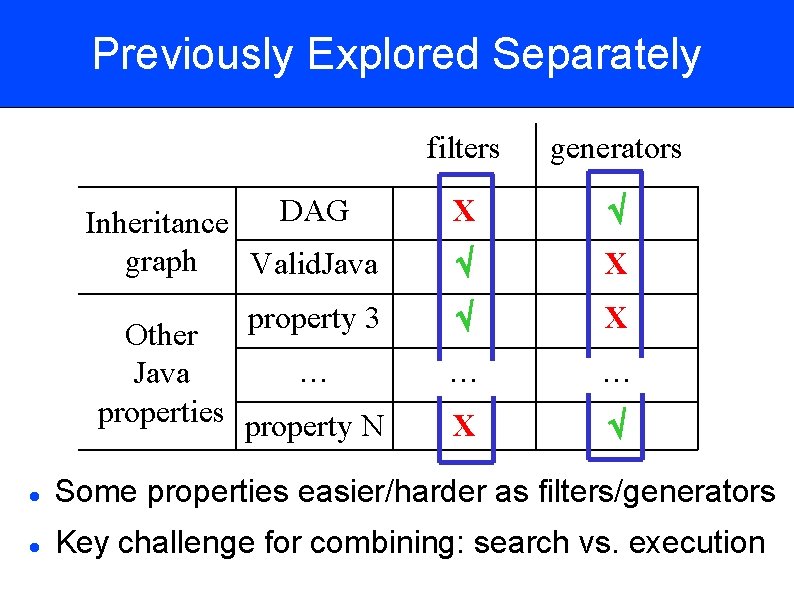

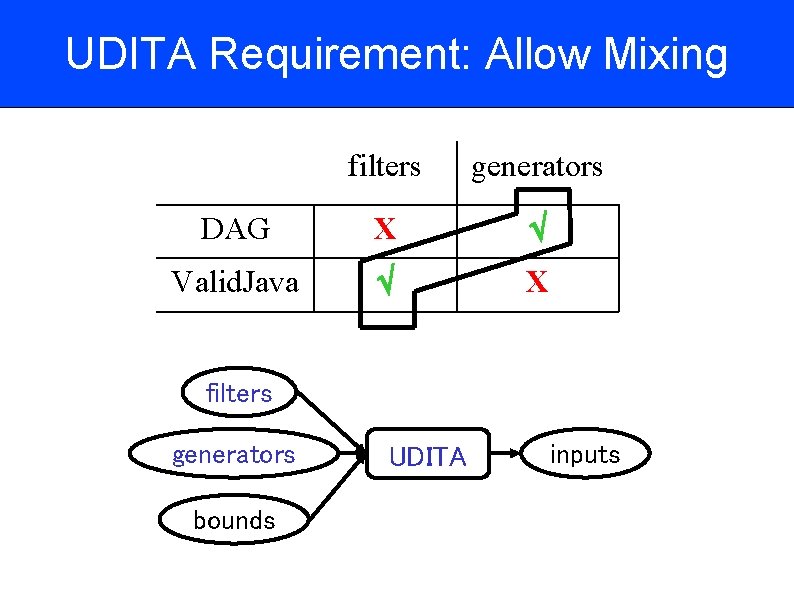

Previously Explored Separately filters generators DAG Inheritance graph Valid. Java X X property 3 X … … X Other … Java properties property N Some properties easier/harder as filters/generators Key challenge for combining: search vs. execution

![UDITA: Combined Both [ICSE’ 10] filters generators DAG Inheritance graph Valid. Java X X UDITA: Combined Both [ICSE’ 10] filters generators DAG Inheritance graph Valid. Java X X](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/bbb92c2396716afdd1b4308480b45c66/image-11.jpg)

UDITA: Combined Both [ICSE’ 10] filters generators DAG Inheritance graph Valid. Java X X property 3 X … … X Other … Java properties property N Extends Java with non-deterministic choices Found bugs in Eclipse/Net. Beans/javac/JPF/UDITA

Outline Introduction Example Filtering Test Abstractions Generating Test Abstractions UDITA: Combined Filtering and Generating Evaluation Conclusions

![Example: Inheritance Graphs class IG { Node[ ] nodes; Properties int size; DAG static Example: Inheritance Graphs class IG { Node[ ] nodes; Properties int size; DAG static](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/bbb92c2396716afdd1b4308480b45c66/image-13.jpg)

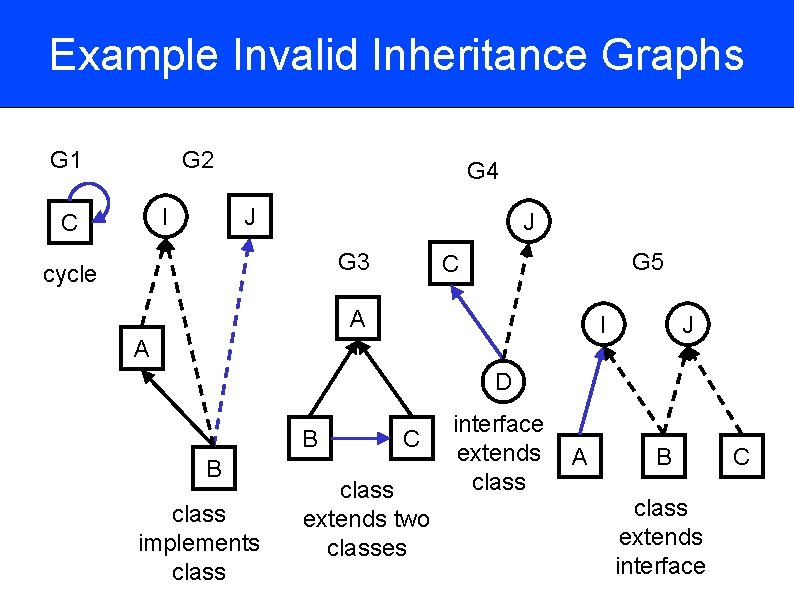

Example: Inheritance Graphs class IG { Node[ ] nodes; Properties int size; DAG static class Node { Node[ ] supertypes; boolean is. Class; } } Nodes in the graph should have no direct cycle Valid. Java Each class has at most one superclass All supertypes of interfaces are interfaces

Example Valid Inheritance Graphs G 1 G 2 I C G 4 J J G 3 G 5 C A I A J D B B C A B C

Example Invalid Inheritance Graphs G 1 G 2 I C G 4 J J G 3 cycle G 5 C A I A J D B B class implements class C class extends two classes interface extends class A B class extends interface C

(In)valid Inputs Valid inputs = desired inputs Inputs on which tester wants to test code Code may produce a regular output or an exception E. g. for Java compiler Interesting (il)legal Java programs No precondition, input can be any text E. g. for abstract data types Encapsulated data structure representations Inputs need to satisfy invariants Invalid inputs = undesired inputs

Outline Introduction Example Filtering Test Abstractions Generating Test Abstractions UDITA: Combined Filtering and Generating Evaluation Conclusions

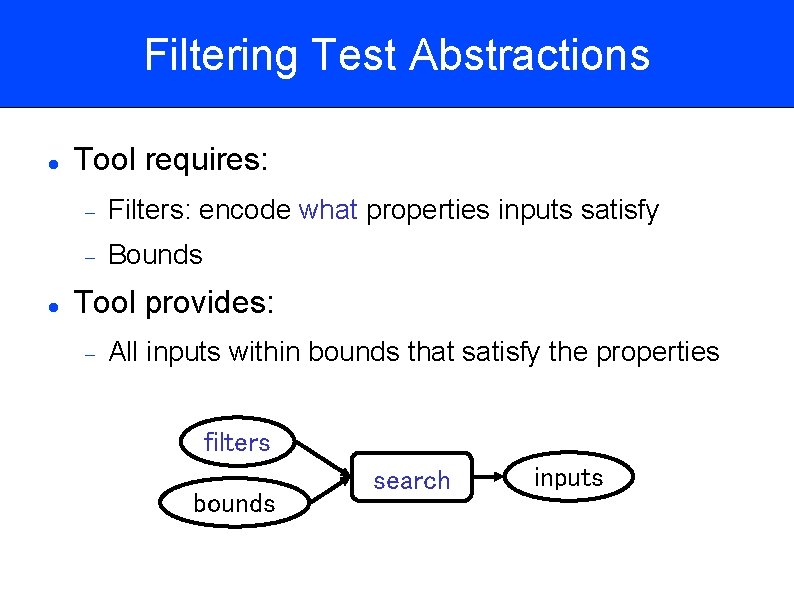

Filtering Test Abstractions Tool requires: Filters: encode what properties inputs satisfy Bounds Tool provides: All inputs within bounds that satisfy the properties filters bounds search inputs

Language for Filters Each filter takes an input that can be valid or invalid Returns a boolean indicating validity Experience from academia and industry showed that using a new language makes adoption hard Write filters in standard implementation language (Java, C#, C++…) Advantages Familiar language Existing development tools Filters may be already present in code Challenge: generate inputs from imperative filters

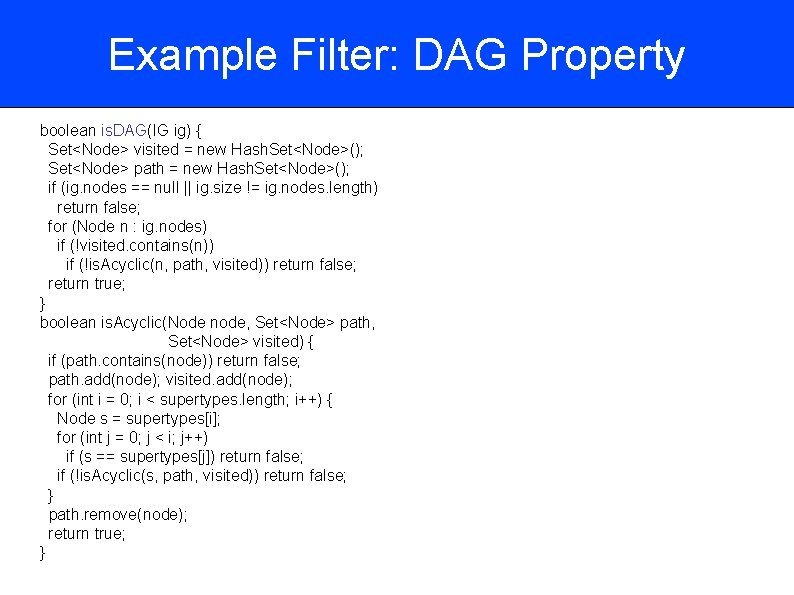

Example Filter: DAG Property boolean is. DAG(IG ig) { Set<Node> visited = new Hash. Set<Node>(); Set<Node> path = new Hash. Set<Node>(); if (ig. nodes == null || ig. size != ig. nodes. length) return false; for (Node n : ig. nodes) if (!visited. contains(n)) if (!is. Acyclic(n, path, visited)) return false; return true; } boolean is. Acyclic(Node node, Set<Node> path, Set<Node> visited) { if (path. contains(node)) return false; path. add(node); visited. add(node); for (int i = 0; i < supertypes. length; i++) { Node s = supertypes[i]; for (int j = 0; j < i; j++) if (s == supertypes[j]) return false; if (!is. Acyclic(s, path, visited)) return false; } path. remove(node); return true; }

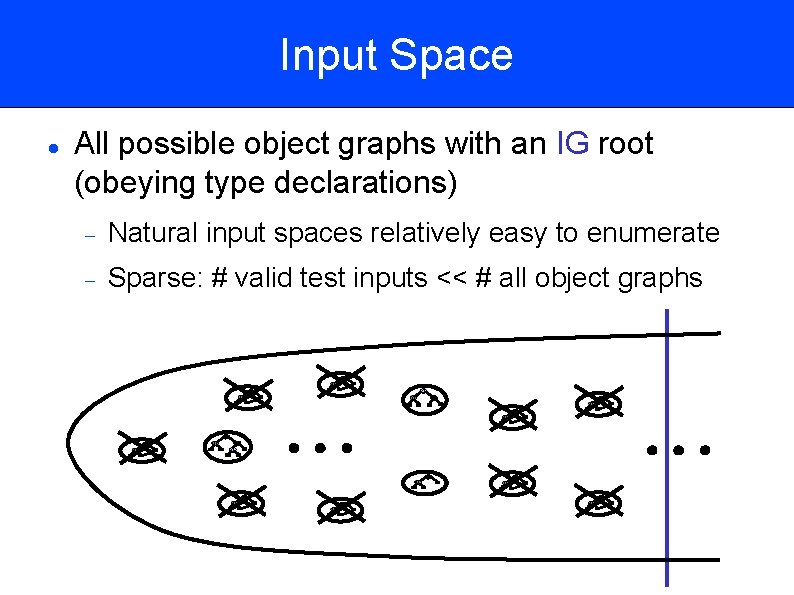

Input Space All possible object graphs with an IG root (obeying type declarations) Natural input spaces relatively easy to enumerate Sparse: # valid test inputs << # all object graphs 0 0 3 2 3 0 0 0 3 0 1 2 3 3 3 0 0 3 3 0 3

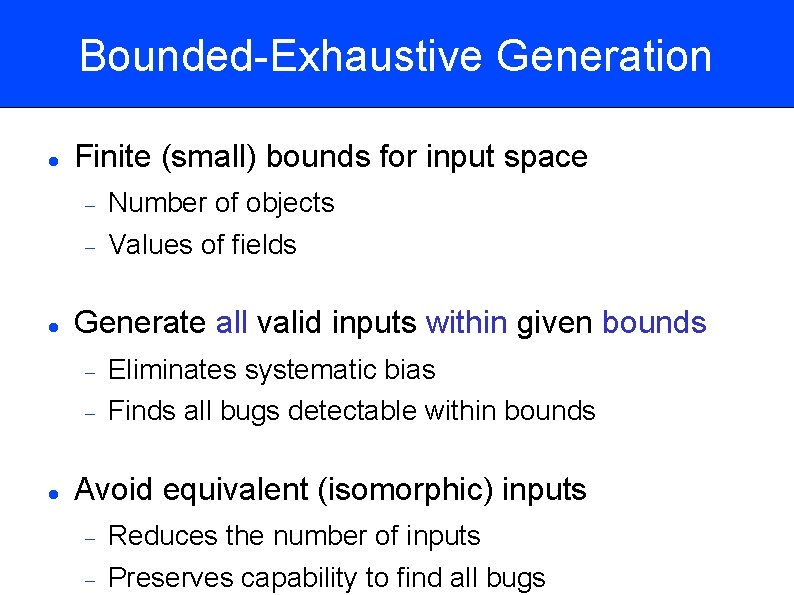

Bounded-Exhaustive Generation Finite (small) bounds for input space Generate all valid inputs within given bounds Number of objects Values of fields Eliminates systematic bias Finds all bugs detectable within bounds Avoid equivalent (isomorphic) inputs Reduces the number of inputs Preserves capability to find all bugs

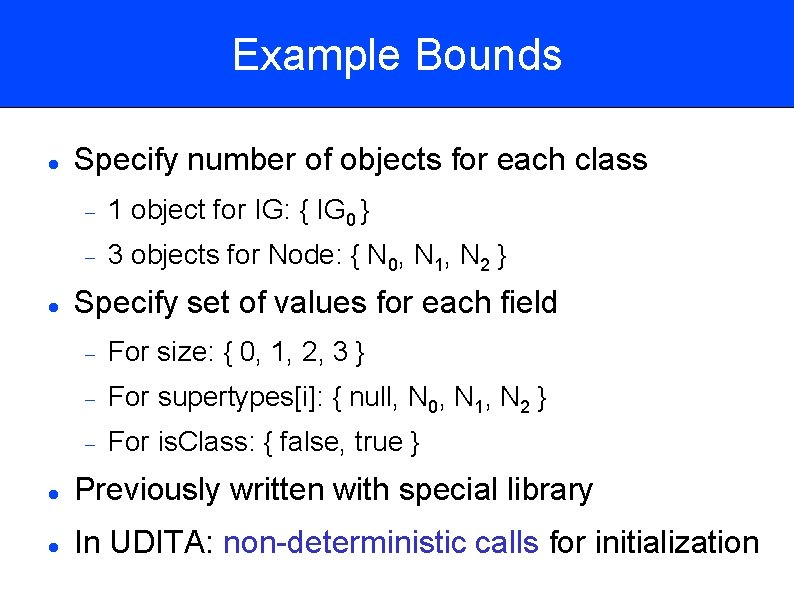

Example Bounds Specify number of objects for each class 1 object for IG: { IG 0 } 3 objects for Node: { N 0, N 1, N 2 } Specify set of values for each field For size: { 0, 1, 2, 3 } For supertypes[i]: { null, N 0, N 1, N 2 } For is. Class: { false, true } Previously written with special library In UDITA: non-deterministic calls for initialization

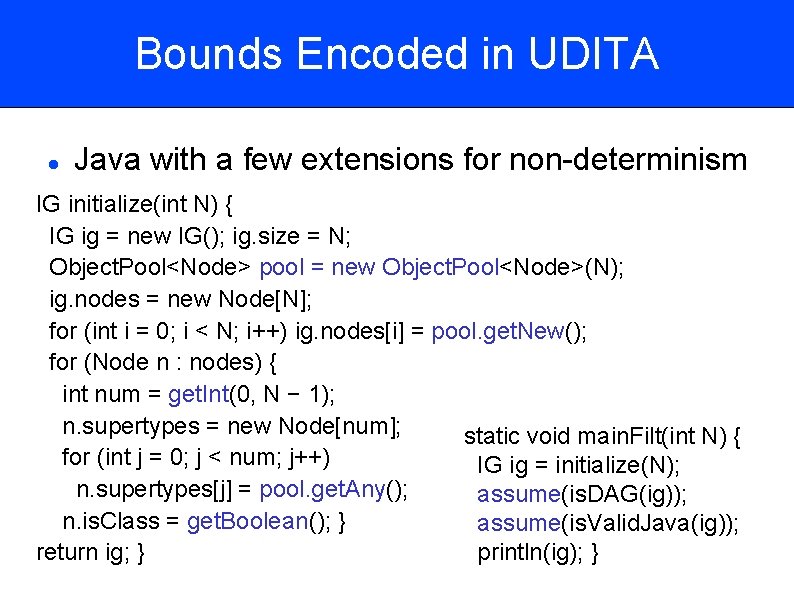

Bounds Encoded in UDITA Java with a few extensions for non-determinism IG initialize(int N) { IG ig = new IG(); ig. size = N; Object. Pool<Node> pool = new Object. Pool<Node>(N); ig. nodes = new Node[N]; for (int i = 0; i < N; i++) ig. nodes[i] = pool. get. New(); for (Node n : nodes) { int num = get. Int(0, N − 1); n. supertypes = new Node[num]; static void main. Filt(int N) { for (int j = 0; j < num; j++) IG ig = initialize(N); n. supertypes[j] = pool. get. Any(); assume(is. DAG(ig)); n. is. Class = get. Boolean(); } assume(is. Valid. Java(ig)); println(ig); } return ig; }

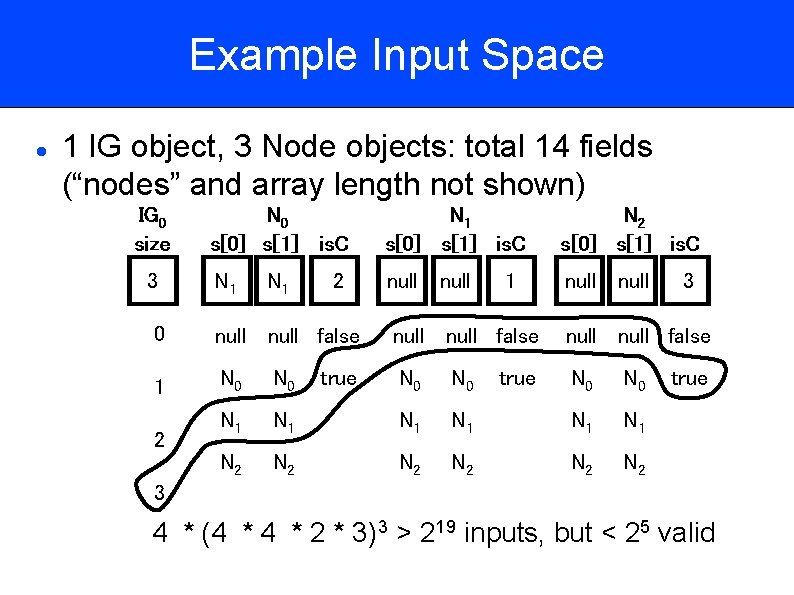

Example Input Space 1 IG object, 3 Node objects: total 14 fields (“nodes” and array length not shown) IG 0 size 3 N 0 s[0] s[1] is. C N 1 s[0] s[1] is. C N 2 s[0] s[1] is. C N 1 null N 1 2 1 3 0 null false null false 1 N 0 N 0 N 0 N 1 N 1 N 1 N 2 N 2 N 2 2 true 3 4 * (4 * 2 * 3)3 > 219 inputs, but < 25 valid

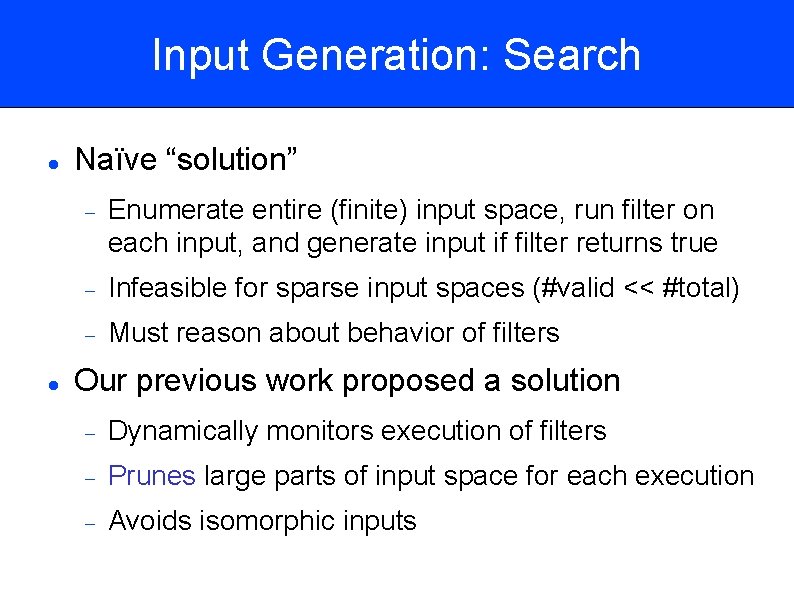

Input Generation: Search Naïve “solution” Enumerate entire (finite) input space, run filter on each input, and generate input if filter returns true Infeasible for sparse input spaces (#valid << #total) Must reason about behavior of filters Our previous work proposed a solution Dynamically monitors execution of filters Prunes large parts of input space for each execution Avoids isomorphic inputs

Outline Introduction Example Filtering Test Abstractions Generating Test Abstractions UDITA: Combined Filtering and Generating Evaluation Conclusions

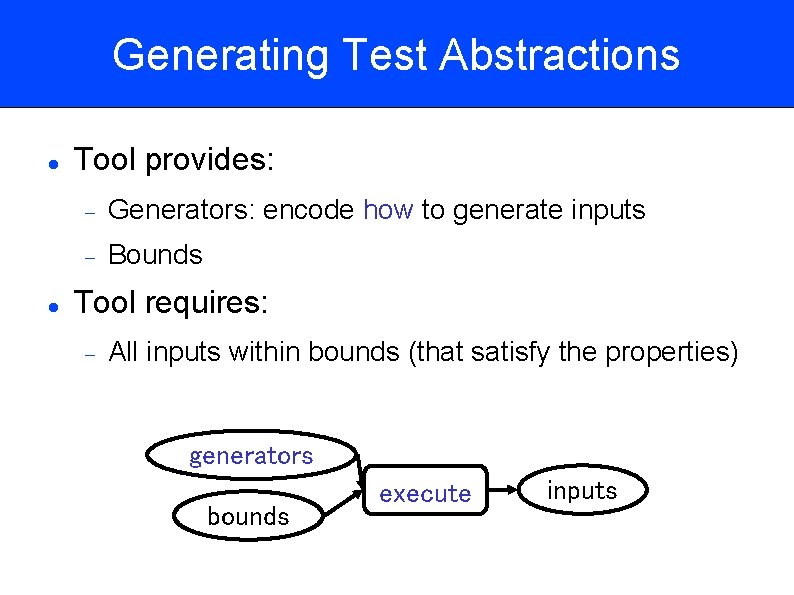

Generating Test Abstractions Tool provides: Generators: encode how to generate inputs Bounds Tool requires: All inputs within bounds (that satisfy the properties) generators bounds execute inputs

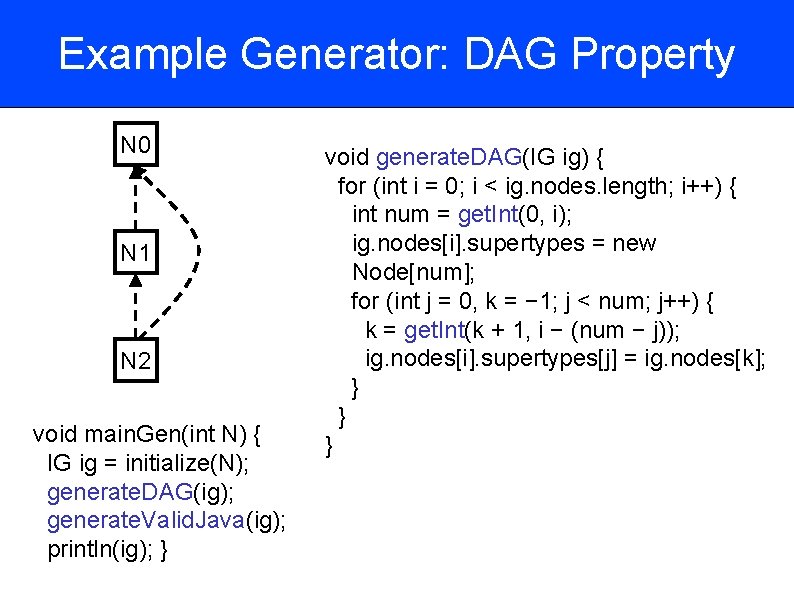

Example Generator: DAG Property N 0 N 1 N 2 void main. Gen(int N) { IG ig = initialize(N); generate. DAG(ig); generate. Valid. Java(ig); println(ig); } void generate. DAG(IG ig) { for (int i = 0; i < ig. nodes. length; i++) { int num = get. Int(0, i); ig. nodes[i]. supertypes = new Node[num]; for (int j = 0, k = − 1; j < num; j++) { k = get. Int(k + 1, i − (num − j)); ig. nodes[i]. supertypes[j] = ig. nodes[k]; } } }

Outline Introduction Example Filtering Test Abstractions Generating Test Abstractions UDITA: Combined Filtering and Generating Evaluation Conclusions

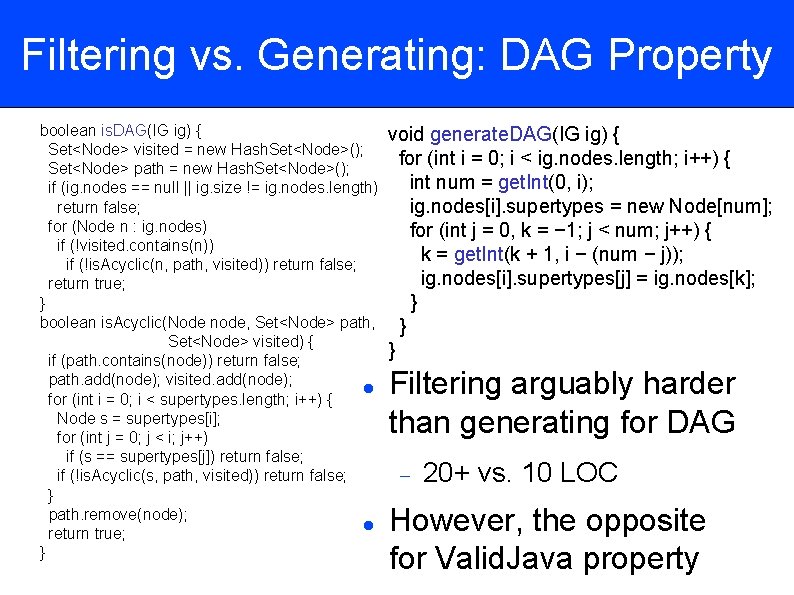

Filtering vs. Generating: DAG Property boolean is. DAG(IG ig) { Set<Node> visited = new Hash. Set<Node>(); Set<Node> path = new Hash. Set<Node>(); if (ig. nodes == null || ig. size != ig. nodes. length) return false; for (Node n : ig. nodes) if (!visited. contains(n)) if (!is. Acyclic(n, path, visited)) return false; return true; } boolean is. Acyclic(Node node, Set<Node> path, Set<Node> visited) { if (path. contains(node)) return false; path. add(node); visited. add(node); for (int i = 0; i < supertypes. length; i++) { Node s = supertypes[i]; for (int j = 0; j < i; j++) if (s == supertypes[j]) return false; if (!is. Acyclic(s, path, visited)) return false; } path. remove(node); return true; } void generate. DAG(IG ig) { for (int i = 0; i < ig. nodes. length; i++) { int num = get. Int(0, i); ig. nodes[i]. supertypes = new Node[num]; for (int j = 0, k = − 1; j < num; j++) { k = get. Int(k + 1, i − (num − j)); ig. nodes[i]. supertypes[j] = ig. nodes[k]; } } } Filtering arguably harder than generating for DAG 20+ vs. 10 LOC However, the opposite for Valid. Java property

UDITA Requirement: Allow Mixing filters generators DAG X Valid. Java X filters generators bounds UDITA inputs

Other Requirements for UDITA Language for test abstractions Ease of use: naturally encode properties Expressiveness: encode a wide range of properties Compositionality: from small to large test abstractions Familiarity: build on a popular language Algorithms and tools for efficient generation of concrete tests from test abstractions Key challenge: search (filtering) and execution (generating) are different paradigms

UDITA Solution Based on a popular language (Java) extended with non-deterministic choices Base language allows writing filters for search/filtering and generators for execution/generating Non-deterministic choices for bounds and enumeration Non-determinism for primitive values: get. Int/Boolean New language abstraction for objects: Object. Pool class Object. Pool<T> { public Object. Pool<T>(int size, boolean include. Null) {. . . } public T get. Any() {. . . } public T get. New() {. . . } }

UDITA Implementation Implemented in Java Path. Finder (JPF) Explicit state model checker from NASA JVM with backtracking capabilities Has non-deterministic call: Verify. get. Int(int lo, int hi) Default/eager generation too slow Efficient generation by delayed choice execution Publicly available JPF extension http: //babelfish. arc. nasa. gov/trac/jpf/wiki/projects/jpf-delayed Documentation on UDITA web page http: //mir. cs. illinois. edu/udita

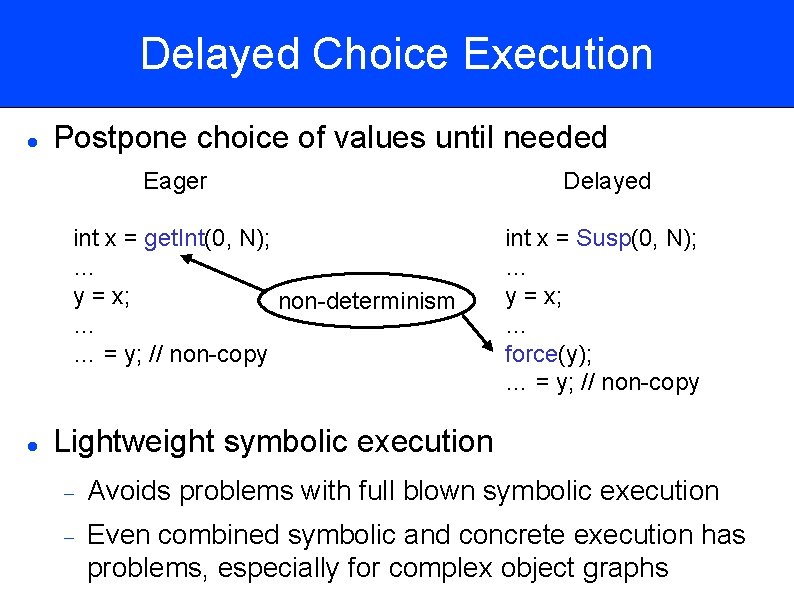

Delayed Choice Execution Postpone choice of values until needed Eager int x = get. Int(0, N); … y = x; non-determinism … … = y; // non-copy Delayed int x = Susp(0, N); … y = x; … force(y); … = y; // non-copy Lightweight symbolic execution Avoids problems with full blown symbolic execution Even combined symbolic and concrete execution has problems, especially for complex object graphs

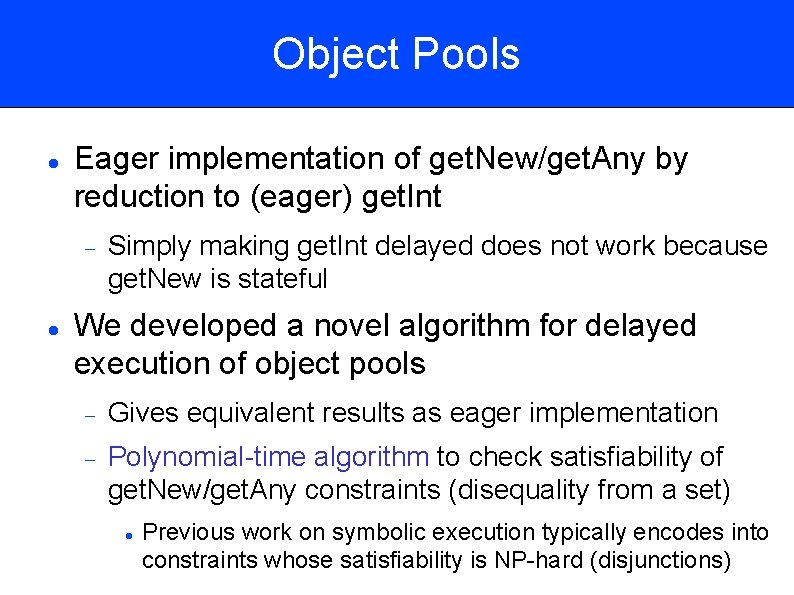

Object Pools Eager implementation of get. New/get. Any by reduction to (eager) get. Int Simply making get. Int delayed does not work because get. New is stateful We developed a novel algorithm for delayed execution of object pools Gives equivalent results as eager implementation Polynomial-time algorithm to check satisfiability of get. New/get. Any constraints (disequality from a set) Previous work on symbolic execution typically encodes into constraints whose satisfiability is NP-hard (disjunctions)

Outline Introduction Example Filtering Test Abstractions Generating Test Abstractions UDITA: Combined Filtering and Generating Evaluation Conclusions

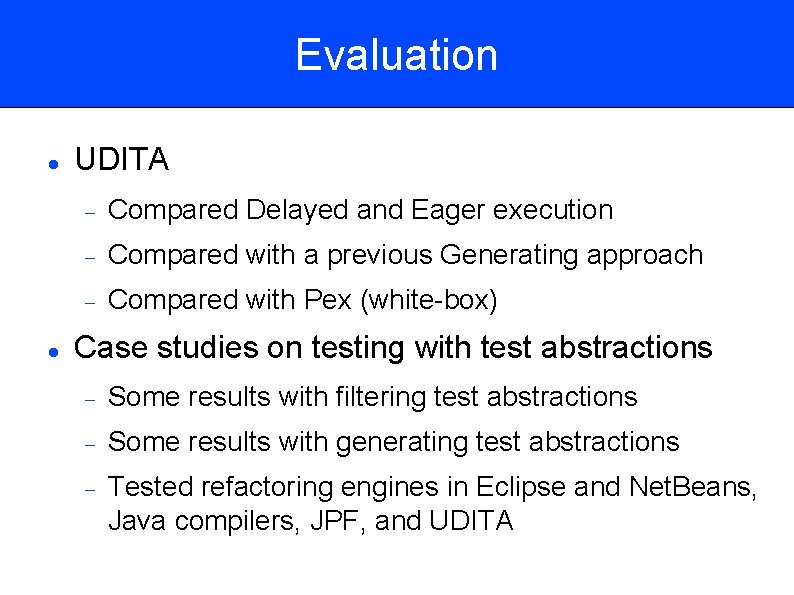

Evaluation UDITA Compared Delayed and Eager execution Compared with a previous Generating approach Compared with Pex (white-box) Case studies on testing with test abstractions Some results with filtering test abstractions Some results with generating test abstractions Tested refactoring engines in Eclipse and Net. Beans, Java compilers, JPF, and UDITA

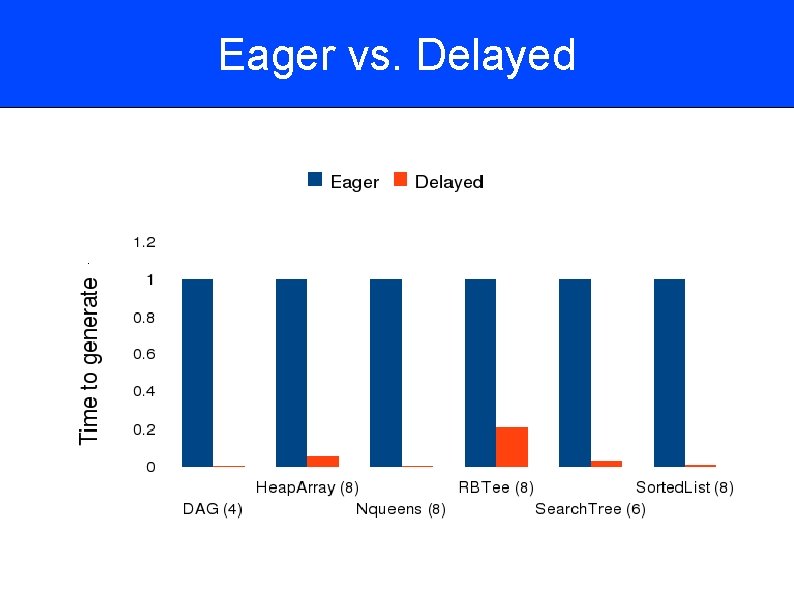

Eager vs. Delayed .

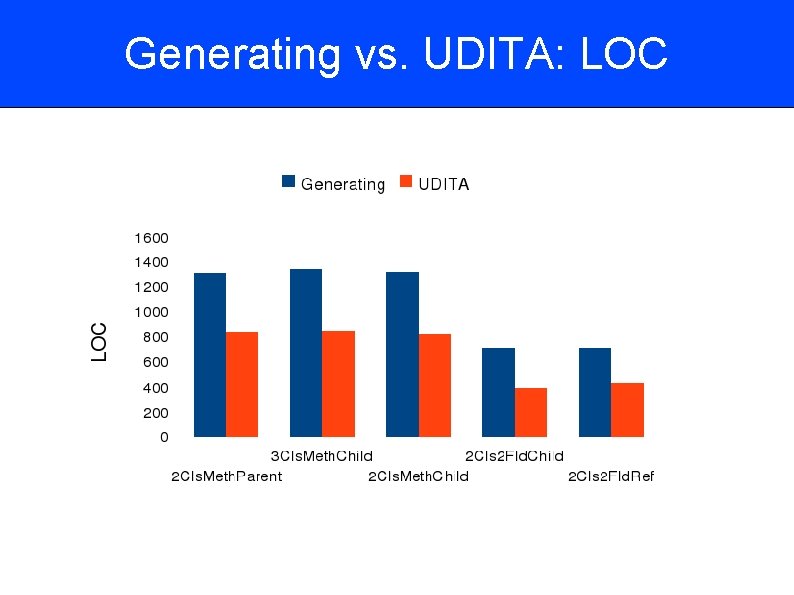

Generating vs. UDITA: LOC

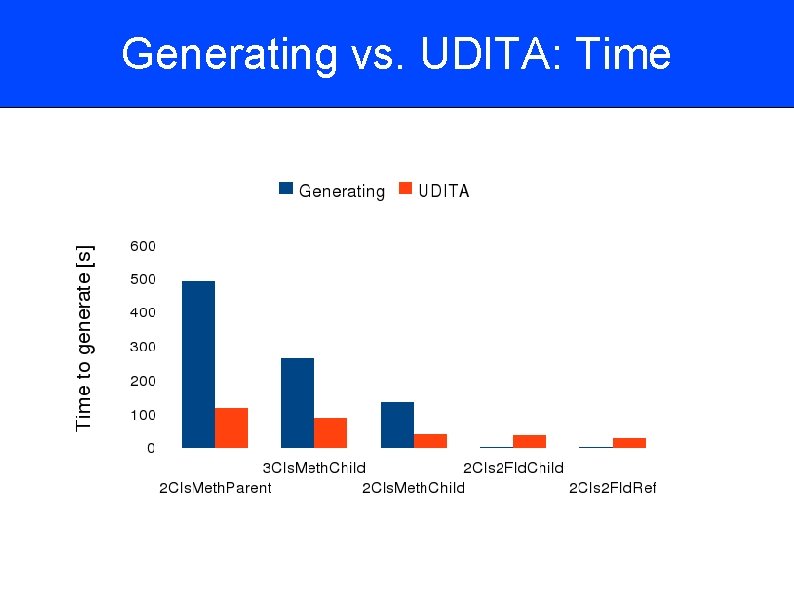

Generating vs. UDITA: Time

UDITA vs. Pex Compared UDITA with Pex State-of-the-art symbolic execution engine from MSR Uses a state-of-the-art constraint solver Comparison on a set of data structures White-box testing: tool monitors code under test Finding seeded bugs Result: object pools help Pex to find bugs Summer internship to include object size in Pex

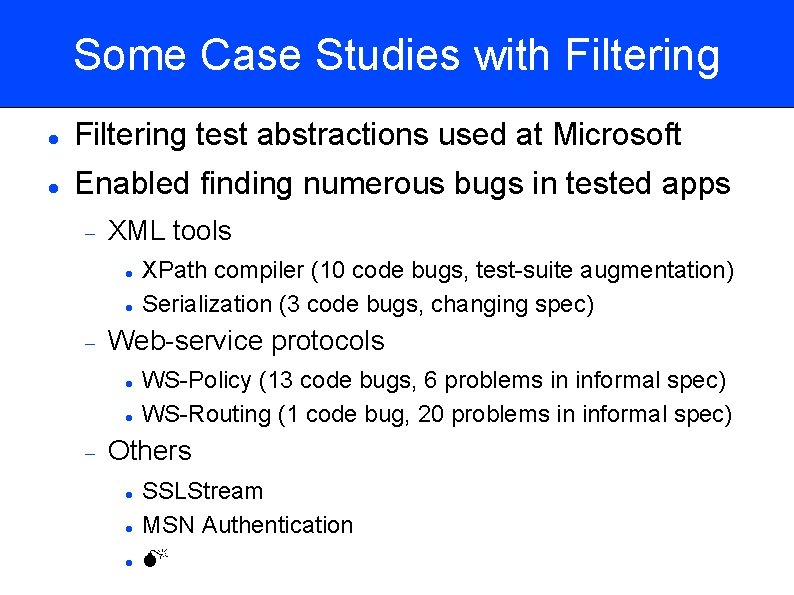

Some Case Studies with Filtering test abstractions used at Microsoft Enabled finding numerous bugs in tested apps XML tools Web-service protocols XPath compiler (10 code bugs, test-suite augmentation) Serialization (3 code bugs, changing spec) WS-Policy (13 code bugs, 6 problems in informal spec) WS-Routing (1 code bug, 20 problems in informal spec) Others SSLStream MSN Authentication

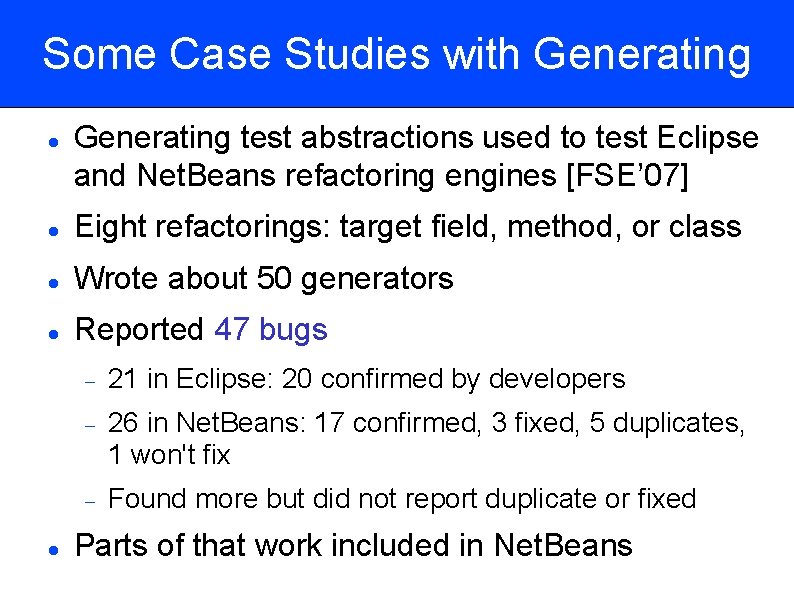

Some Case Studies with Generating test abstractions used to test Eclipse and Net. Beans refactoring engines [FSE’ 07] Eight refactorings: target field, method, or class Wrote about 50 generators Reported 47 bugs 21 in Eclipse: 20 confirmed by developers 26 in Net. Beans: 17 confirmed, 3 fixed, 5 duplicates, 1 won't fix Found more but did not report duplicate or fixed Parts of that work included in Net. Beans

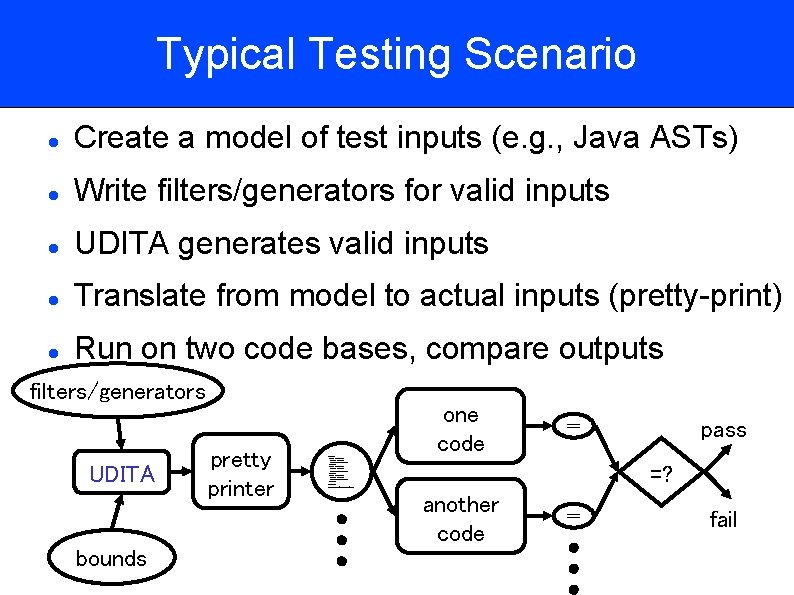

Typical Testing Scenario Create a model of test inputs (e. g. , Java ASTs) Write filters/generators for valid inputs UDITA generates valid inputs Translate from model to actual inputs (pretty-print) Run on two code bases, compare outputs filters/generators UDITA bounds pretty printer one code pass <title>T 1</title> <title>T 2</title> <library> <book year=2001> <title>T 1</title> <author>A 1</author> </book> <book year=2002> <title>T 2</title> <author>A 2</author> </book> <book year=2003> <title>T 3</title> <author>A 3</author> </book> </library> =? /library/book[@year<2003]/titl another code <title>T 1</title> <title>T 2</title> fail

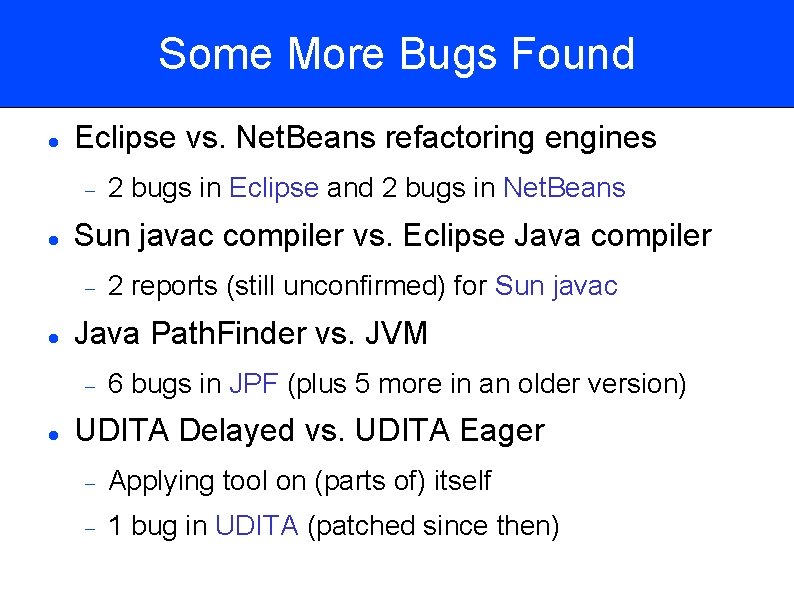

Some More Bugs Found Eclipse vs. Net. Beans refactoring engines Sun javac compiler vs. Eclipse Java compiler 2 reports (still unconfirmed) for Sun javac Java Path. Finder vs. JVM 2 bugs in Eclipse and 2 bugs in Net. Beans 6 bugs in JPF (plus 5 more in an older version) UDITA Delayed vs. UDITA Eager Applying tool on (parts of) itself 1 bug in UDITA (patched since then)

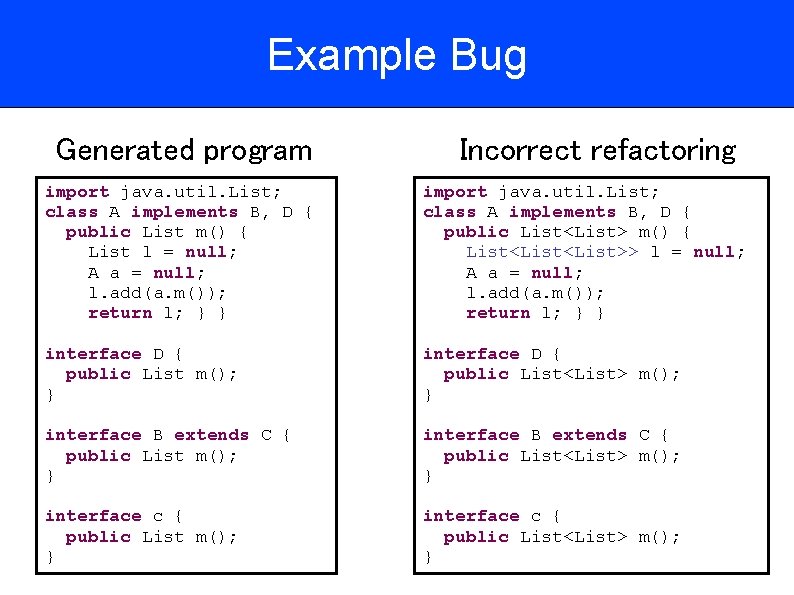

Example Bug Generated program Incorrect refactoring import java. util. List; class A implements B, D { public List m() { List l = null; A a = null; l. add(a. m()); return l; } } import java. util. List; class A implements B, D { public List<List> m() { List<List>> l = null; A a = null; l. add(a. m()); return l; } } interface D { public List m(); } interface D { public List<List> m(); } interface B extends C { public List<List> m(); } interface c { public List<List> m(); }

Outline Introduction Example Filtering Test Abstractions Generating Test Abstractions UDITA: Combined Filtering and Generating Evaluation Conclusions

Summary Testing is important for software reliability Necessary step before (even after) deployment Structurally complex data Increasingly used in modern systems Important challenge for software testing Test abstractions Proposed model for complex test data Adopted in industry Used to find bugs in several real-world applications

Benefits & Costs of Test Abstractions Benefits Test abstractions can find bugs in real code (e. g. , at Microsoft or for Eclipse/Net. Beans/javac/JPF/UDITA) Arguably better than manual testing Costs 1. Human time for writing test abstractions (filters or generators) [UDITA, ICSE’ 10] 2. Machine time for generating/executing/checking tests (human time waiting for the tool) [FASE’ 09] 3. Human time for inspecting failing tests [FASE’ 09]

Credits for Generating TA and UDITA Collaborators from U. of Illinois and other schools Brett Daniel Milos Gligoric (Belgrade->Illinois) Danny Dig Tihomir Gvero (Belgrade->EPFL) Kely Garcia Sarfraz Khurshid (UT Austin) Vilas Jagannath Viktor Yun Young Lee Kuncak (EPFL) Funding NSF CCF-0746856, CNS-0615372, CNS-0613665 Microsoft gift

Test Abstractions Test abstractions Proposed model for structurally complex test data Adopted in industry Used to find bugs in several real-world applications (e. g. , at Microsoft, Eclipse/Net. Beans/javac/JPF/UDITA) UDITA: latest approach for test abstractions Easier to write test abstractions Novel algorithm for faster generation Publicly available JPF extension http: //mir. cs. illinois. edu/udita

- Slides: 53