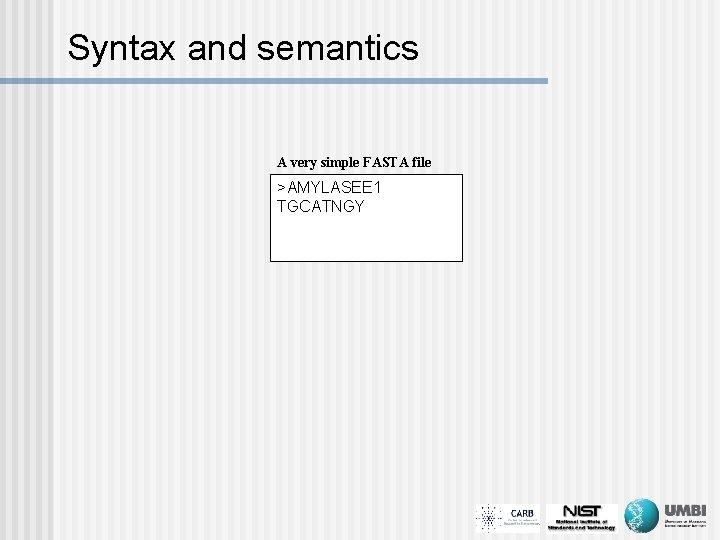

Syntax and semantics A very simple FASTA file

- Slides: 15

Syntax and semantics A very simple FASTA file >AMYLASEE 1 TGCATNGY

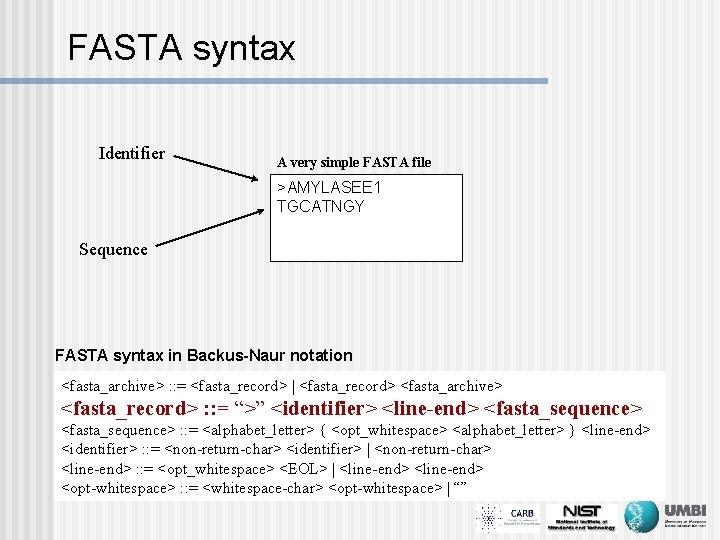

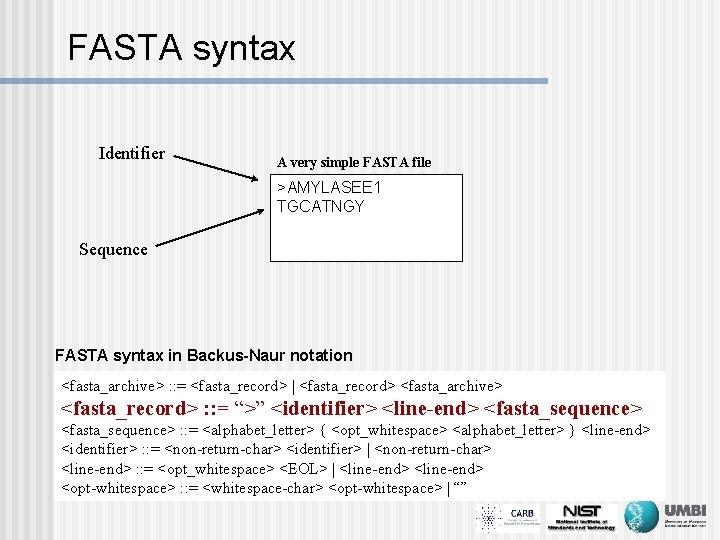

FASTA syntax Identifier A very simple FASTA file >AMYLASEE 1 TGCATNGY Sequence FASTA syntax in Backus-Naur notation <fasta_archive> : : = <fasta_record> | <fasta_record> <fasta_archive> <fasta_record> : : = “>” <identifier> <line-end> <fasta_sequence> : : = <alphabet_letter> { <opt_whitespace> <alphabet_letter> } <line-end> <identifier> : : = <non-return-char> <identifier> | <non-return-char> <line-end> : : = <opt_whitespace> <EOL> | <line-end> <opt-whitespace> : : = <whitespace-char> <opt-whitespace> | “”

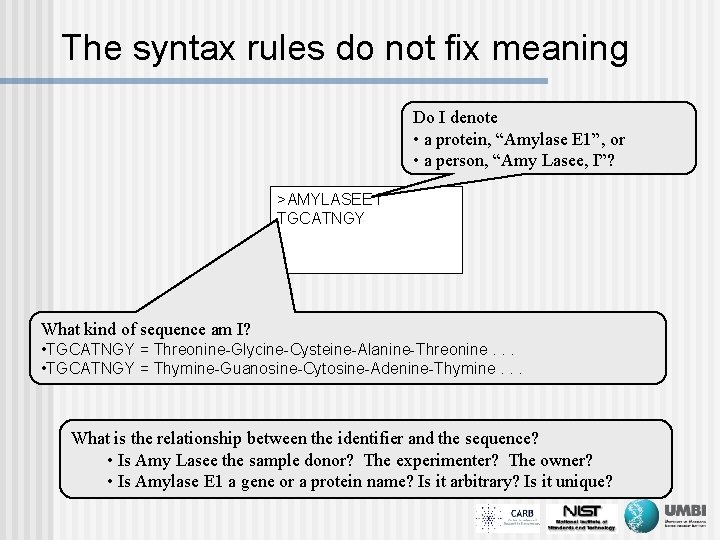

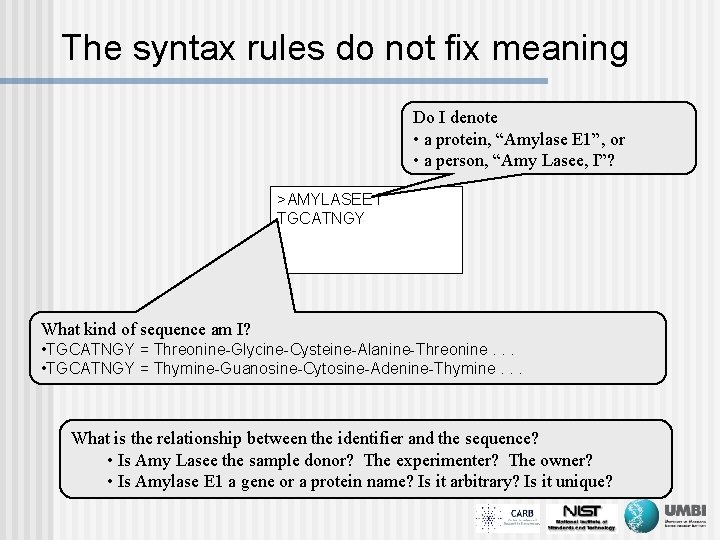

The syntax rules do not fix meaning Do I denote • a protein, “Amylase E 1”, or • a person, “Amy Lasee, I”? >AMYLASEE 1 TGCATNGY What kind of sequence am I? • TGCATNGY = Threonine-Glycine-Cysteine-Alanine-Threonine. . . • TGCATNGY = Thymine-Guanosine-Cytosine-Adenine-Thymine. . . What is the relationship between the identifier and the sequence? • Is Amy Lasee the sample donor? The experimenter? The owner? • Is Amylase E 1 a gene or a protein name? Is it arbitrary? Is it unique?

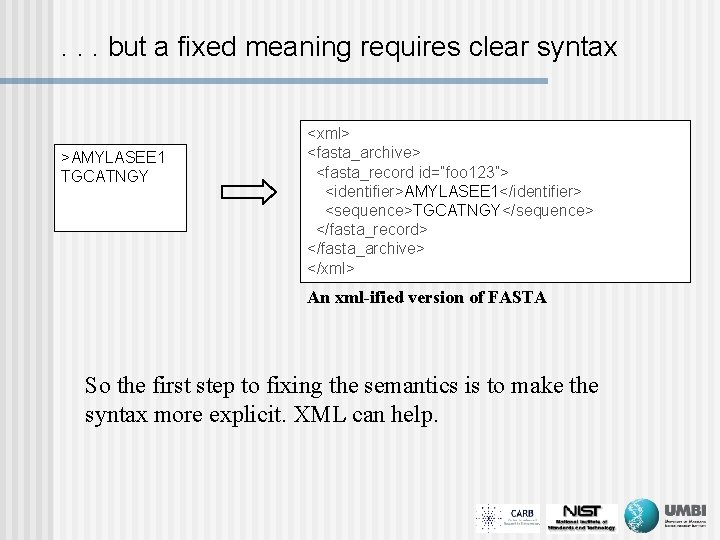

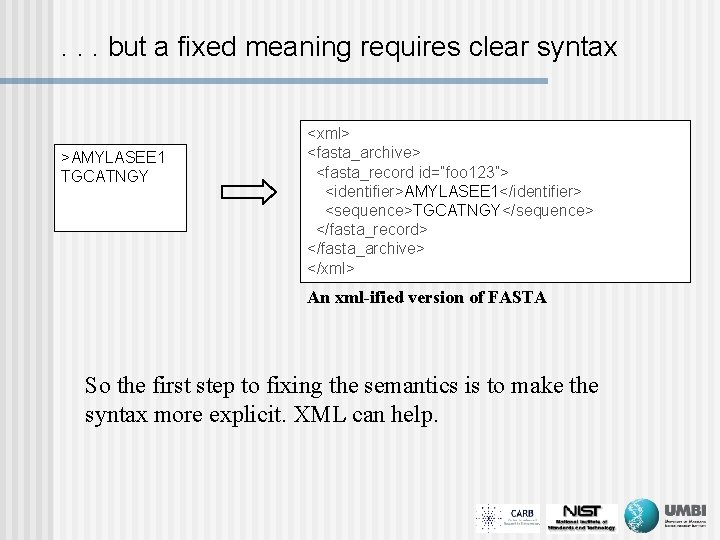

. . . but a fixed meaning requires clear syntax >AMYLASEE 1 TGCATNGY <xml> <fasta_archive> <fasta_record id=“foo 123”> <identifier>AMYLASEE 1</identifier> <sequence>TGCATNGY</sequence> </fasta_record> </fasta_archive> </xml> An xml-ified version of FASTA So the first step to fixing the semantics is to make the syntax more explicit. XML can help.

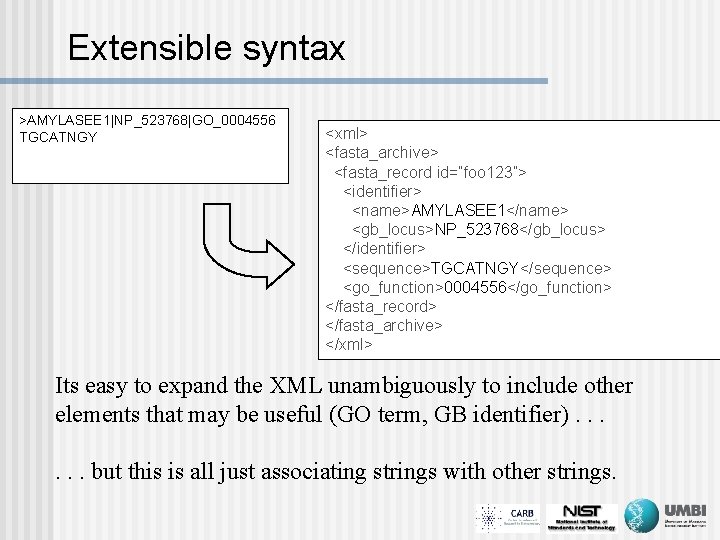

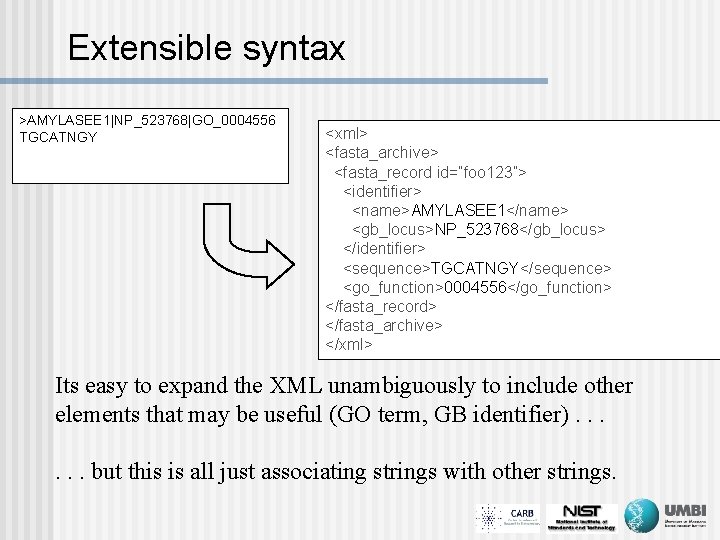

Extensible syntax >AMYLASEE 1|NP_523768|GO_0004556 TGCATNGY <xml> <fasta_archive> <fasta_record id=“foo 123”> <identifier> <name>AMYLASEE 1</name> <gb_locus>NP_523768</gb_locus> </identifier> <sequence>TGCATNGY</sequence> <go_function>0004556</go_function> </fasta_record> </fasta_archive> </xml> Its easy to expand the XML unambiguously to include other elements that may be useful (GO term, GB identifier). . . but this is all just associating strings with other strings.

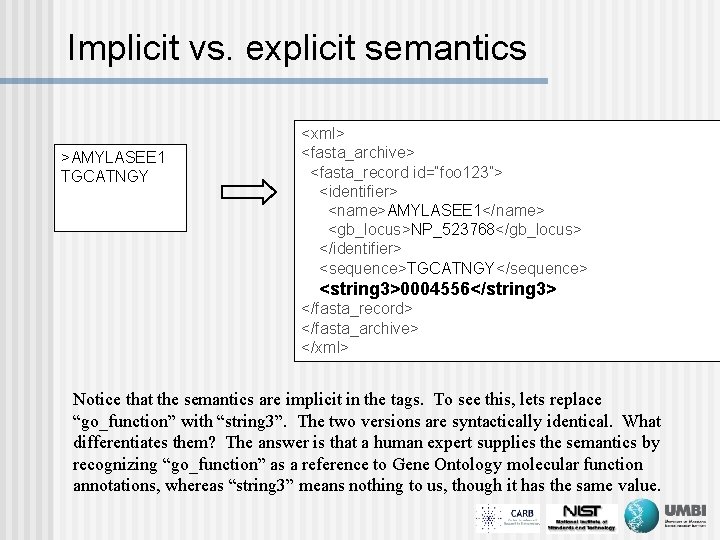

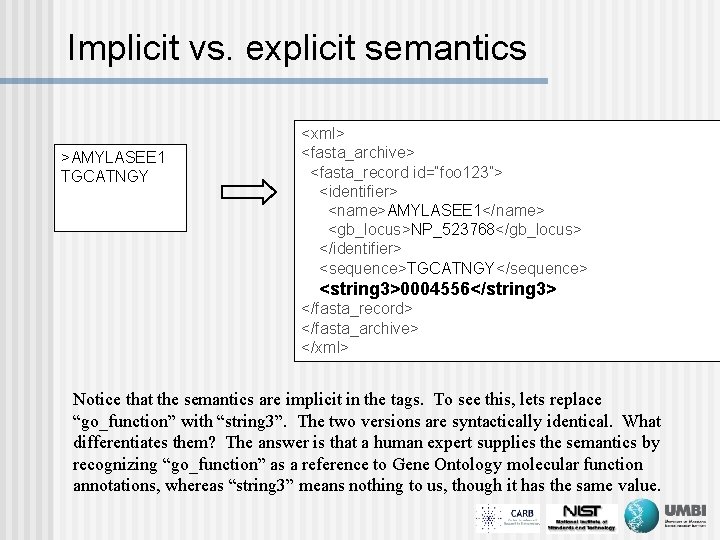

Implicit vs. explicit semantics >AMYLASEE 1 TGCATNGY <xml> <fasta_archive> <fasta_record id=“foo 123”> <identifier> <name>AMYLASEE 1</name> <gb_locus>NP_523768</gb_locus> </identifier> <sequence>TGCATNGY</sequence> <go_function>0004556</go_function> <string 3>0004556</string 3> </fasta_record> </fasta_archive> </xml> Notice that the semantics are implicit in the tags. To see this, lets replace “go_function” with “string 3”. The two versions are syntactically identical. What differentiates them? The answer is that a human expert supplies the semantics by recognizing “go_function” as a reference to Gene Ontology molecular function annotations, whereas “string 3” means nothing to us, though it has the same value.

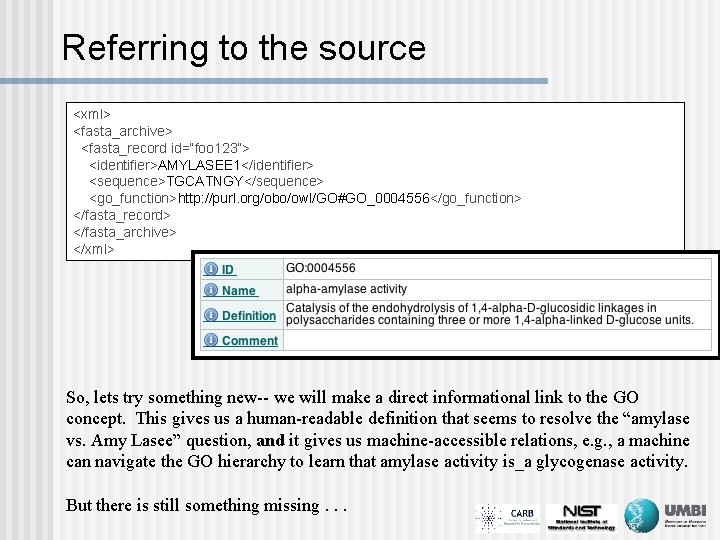

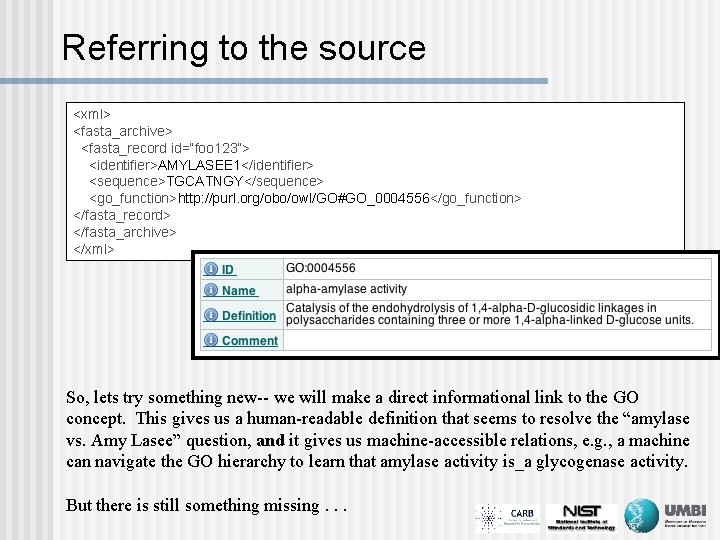

Referring to the source <xml> <fasta_archive> <fasta_record id=“foo 123”> <identifier>AMYLASEE 1</identifier> <sequence>TGCATNGY</sequence> <go_function>http: //purl. org/obo/owl/GO#GO_0004556</go_function> </fasta_record> </fasta_archive> </xml> So, lets try something new-- we will make a direct informational link to the GO concept. This gives us a human-readable definition that seems to resolve the “amylase vs. Amy Lasee” question, and it gives us machine-accessible relations, e. g. , a machine can navigate the GO hierarchy to learn that amylase activity is_a glycogenase activity. But there is still something missing. . .

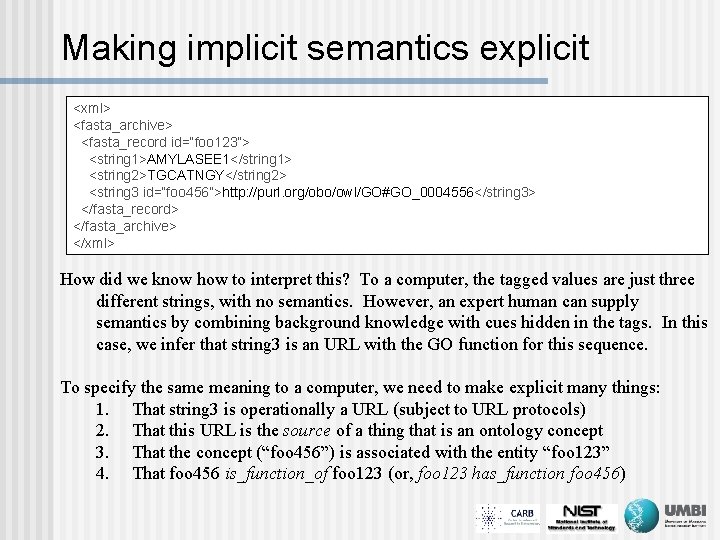

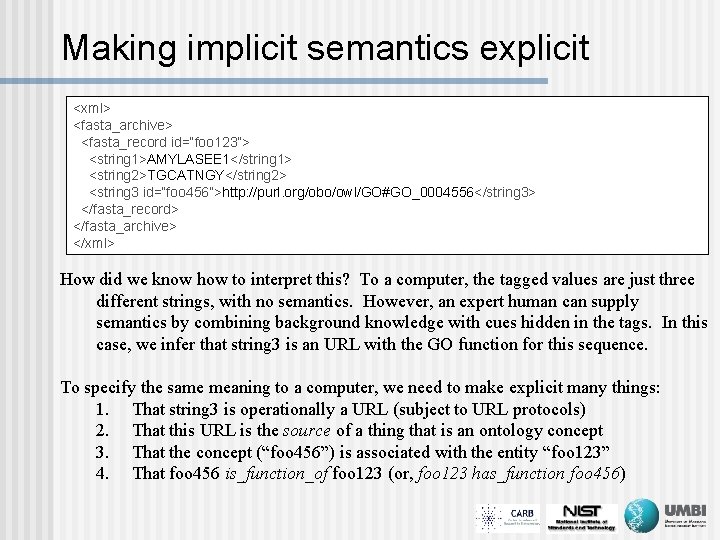

Making implicit semantics explicit <xml> <fasta_archive> <fasta_record id=“foo 123”> <string 1>AMYLASEE 1</string 1> <string 2>TGCATNGY</string 2> <string 3 id=“foo 456”>http: //purl. org/obo/owl/GO#GO_0004556</string 3> </fasta_record> </fasta_archive> </xml> How did we know how to interpret this? To a computer, the tagged values are just three different strings, with no semantics. However, an expert human can supply semantics by combining background knowledge with cues hidden in the tags. In this case, we infer that string 3 is an URL with the GO function for this sequence. To specify the same meaning to a computer, we need to make explicit many things: 1. That string 3 is operationally a URL (subject to URL protocols) 2. That this URL is the source of a thing that is an ontology concept 3. That the concept (“foo 456”) is associated with the entity “foo 123” 4. That foo 456 is_function_of foo 123 (or, foo 123 has_function foo 456)

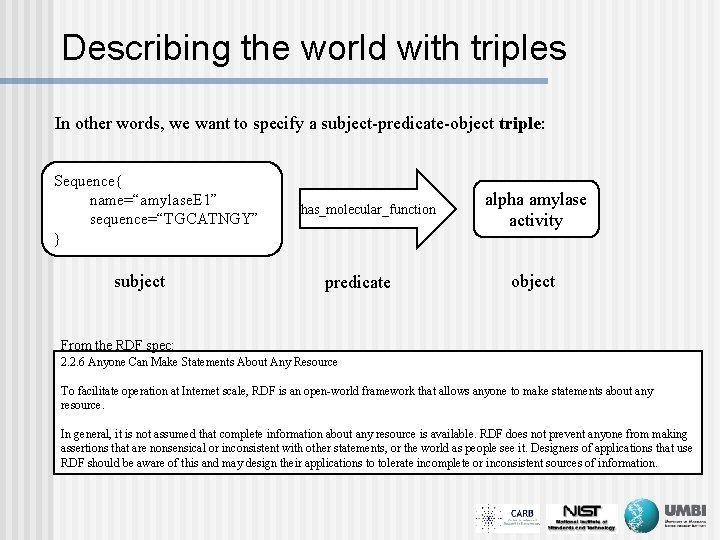

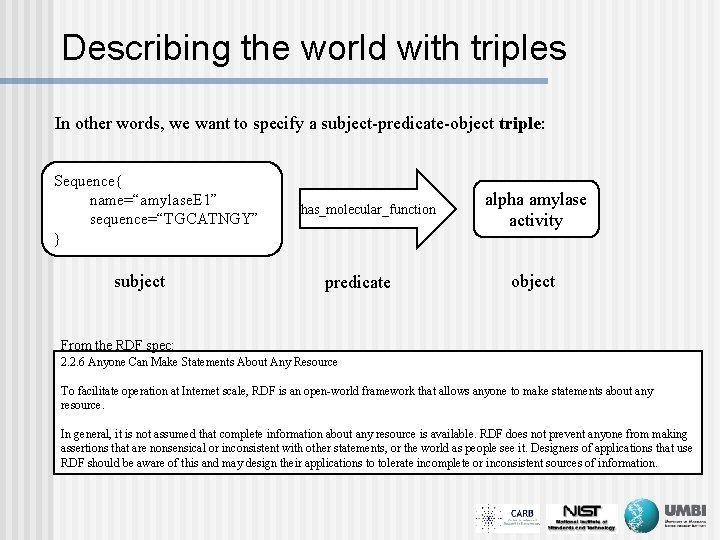

Describing the world with triples In other words, we want to specify a subject-predicate-object triple: Sequence{ name=“amylase. E 1” sequence=“TGCATNGY” } subject has_molecular_function predicate alpha amylase activity object From the RDF spec: 2. 2. 6 Anyone Can Make Statements About Any Resource To facilitate operation at Internet scale, RDF is an open-world framework that allows anyone to make statements about any resource. In general, it is not assumed that complete information about any resource is available. RDF does not prevent anyone from making assertions that are nonsensical or inconsistent with other statements, or the world as people see it. Designers of applications that use RDF should be aware of this and may design their applications to tolerate incomplete or inconsistent sources of information.

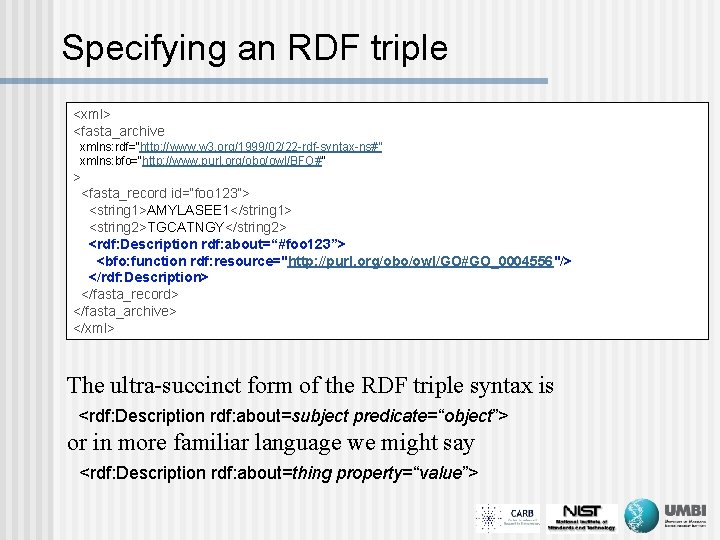

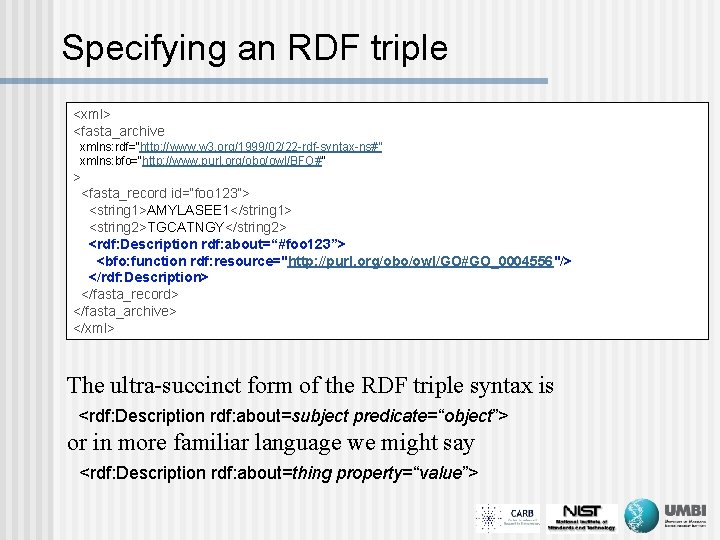

Specifying an RDF triple <xml> <fasta_archive xmlns: rdf=“http: //www. w 3. org/1999/02/22 -rdf-syntax-ns#” xmlns: bfo=“http: //www. purl. org/obo/owl/BFO#” > <fasta_record id=“foo 123”> <string 1>AMYLASEE 1</string 1> <string 2>TGCATNGY</string 2> <rdf: Description rdf: about=“#foo 123”> <bfo: function rdf: resource="http: //purl. org/obo/owl/GO#GO_0004556"/> </rdf: Description> </fasta_record> </fasta_archive> </xml> The ultra-succinct form of the RDF triple syntax is <rdf: Description rdf: about=subject predicate=“object”> or in more familiar language we might say <rdf: Description rdf: about=thing property=“value”>

Using nexml syntax Not finished. Nexml provides 2 ways to express semantics: 1. Built-in links to CDAO (SAWSDL links in schema) 2. Ad hoc references to external namespaces in <dict>

Built-in links to CDAO Not finished. Example (“Edge”) of SAWSDL links in schema

References to external namespaces using <dict> elements Not finished. Will explain some examples from wiki.

some things to express (see wiki) • Attaching a concept to an element • Attaching annotation or an external resource to an element • Attaching a concept to an element through a relation • Attaching a taxon identifier to an OTU through a relation • Identifying specimens within collections • Literature References • Example 1: associate a reference with a tree (or other) element • Example 2: associate a reference with a record • Associating an OBO phenotype with a character state

What can I do with semantics? Not finished. 1 thing to do is to make semantics clear to human users. Another thing is to make this accessible to computers. What can the computers do? If you have software to read your files and reconstruct the RDF triples as statements in the ontology language, then you can carry out reasoning in the ontology language. Examples (taxonomy; types of chars; anatomical relations of chars)