Synchronous Collaboration and Awareness Systems Bo Begole Ubiquitous

Synchronous Collaboration and Awareness Systems Bo Begole Ubiquitous Computing Area Manager Computer Science Lab UC Berkeley, Sep 25, 2006

Synchronous Collaboration and Awareness Systems n n Degrees of Interdependence Replicated Application Sharing: Flexible JAMM Multi-user UNIX terminal: Shared. Shell Awareness: – Con. Nexus – Awarenex n Presence and Availability Forecasting: – Rhythm Awareness – Lilsys

Why CSCW Research is Important n n Inter-Personal Computing Most of what we do with computers is communicated to others – Documents – Information Analysis – Even calculating Ballistic Missile trajectories are a form of communication (“I hate you”) n CSCW combines systems and social research

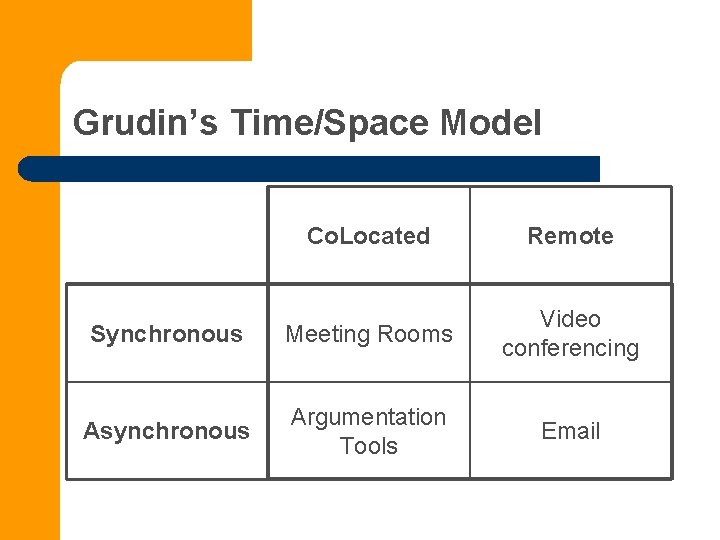

Grudin’s Time/Space Model Co. Located Remote Synchronous Meeting Rooms Video conferencing Asynchronous Argumentation Tools Email

Degrees of Interdependence Two Examples Research Funding: Technology Development: Weakly Interdependent work Moderately Interdependent work Proposal Module-level programming Highly interactive Interdependent work Reviews System design & prgrmng Negotiation System integration & debugging Task Criticality Time Spent Communication Tools Paper Memos Usenet Web pages Asynch Productivity Tools Editors Browsers & other Viewers SMS Text chat Full-duplex audio Push-to-talk Face-to-face audio meeting IM email Blogs Semi, Peri, Psuedo-synch Shared File Systems Decision Support Systems Wikis Distributed Presentation Meeting Support Systems Synchronous Multiplayer Games Shared Apps

Collaboration Transparency • Sharing single-user legacy applications • Application source code is not modified • Runtime environment is modified • sharing mechanism is “transparent” to application. • Synchronous “Application sharing” for • Pair programming • Debugging/integration • Collaborative document editing • Examples: • Net. Meeting, Web. Ex, Go. To. My. PC, Shared. X, Shared. App, XTV, Sun. Forum, Timbuktu, etc.

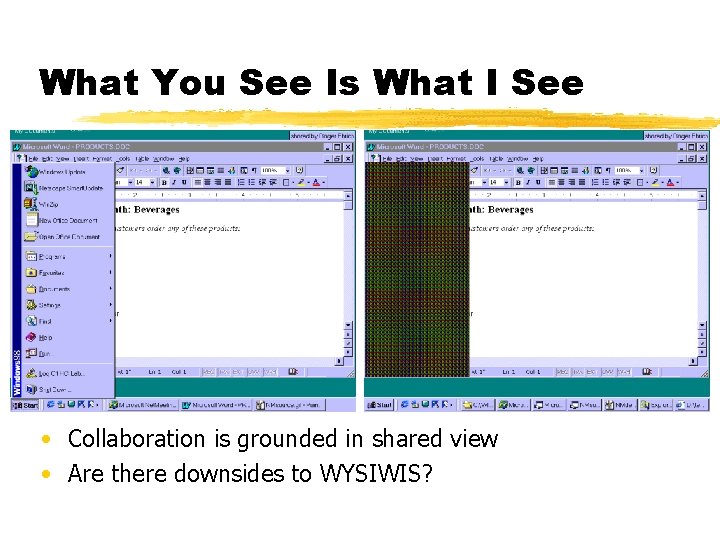

What You See Is What I See view but • Collaboration is grounded in shared view, • prevents independent to work • Are there downsides WYSIWIS?

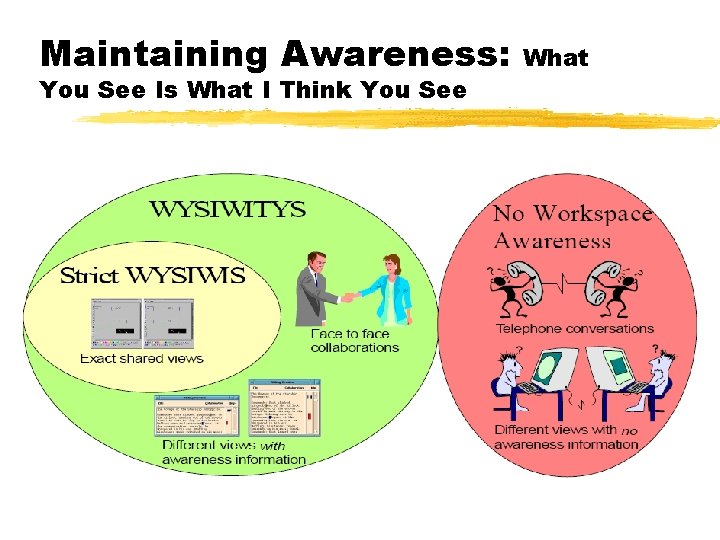

Maintaining Awareness: You See Is What I Think You See What

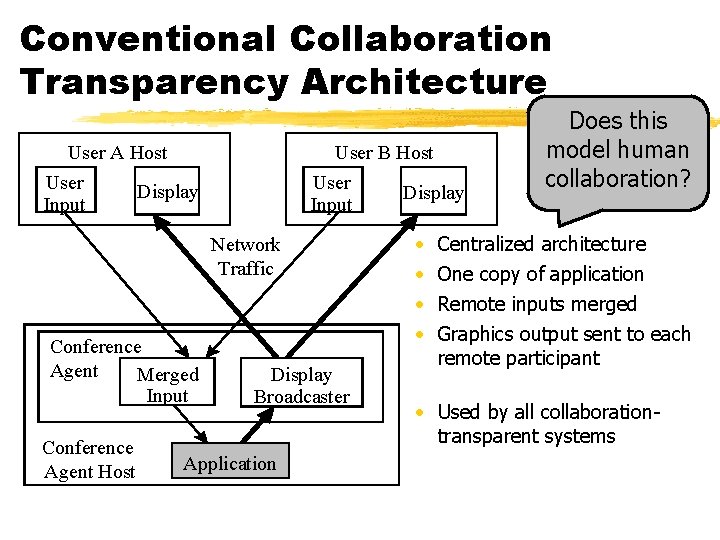

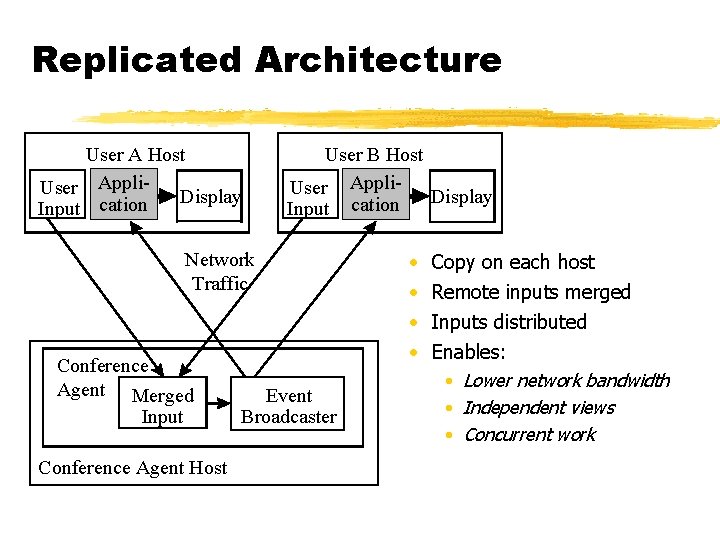

Conventional Collaboration Transparency Architecture User A Host User Input User B Host User Input Display Network Traffic Conference Agent Merged Input Conference Agent Host Display Broadcaster Application Display • • Does this model human collaboration? Centralized architecture One copy of application Remote inputs merged Graphics output sent to each remote participant • Used by all collaborationtransparent systems

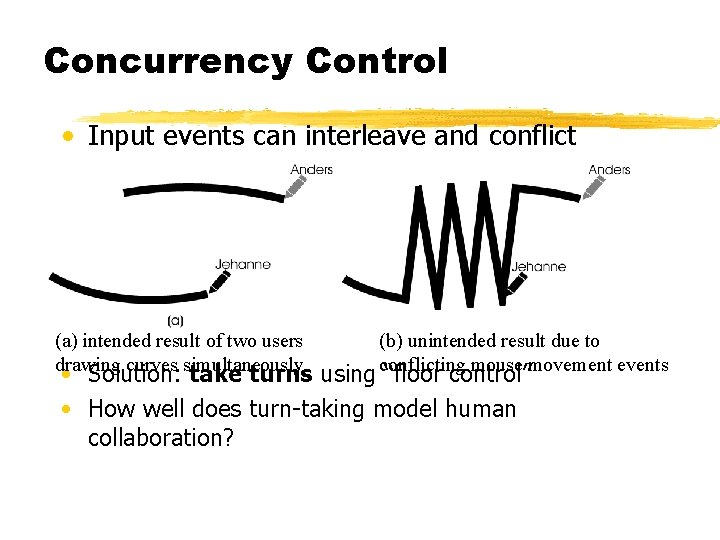

Concurrency Control • Input events can interleave and conflict (a) intended result of two users drawing curves simultaneously (b) unintended result due to conflicting mouse movement events • Solution: take turns using “floor control” • How well does turn-taking model human collaboration?

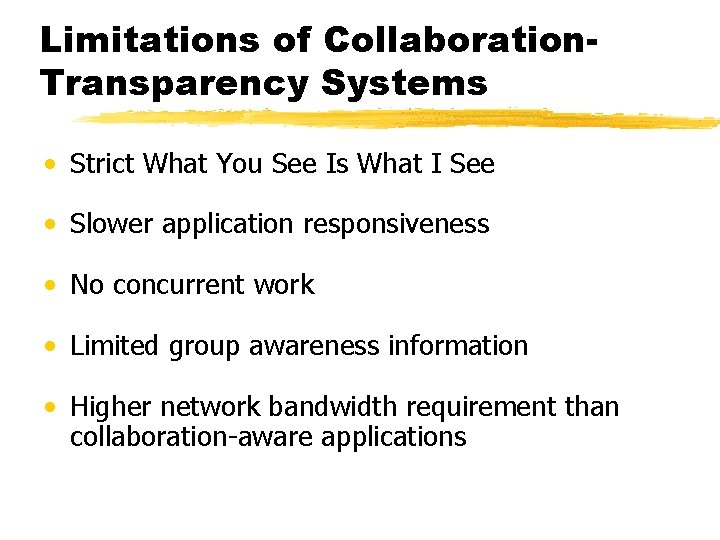

Limitations of Collaboration. Transparency Systems • Strict What You See Is What I See • Slower application responsiveness • No concurrent work • Limited group awareness information • Higher network bandwidth requirement than collaboration-aware applications

Collaboration-Aware Applications • Applications designed for collaborative use • Examples: • • Editors – SASSE, Calliope, Sub. Etha. Edit, Writely Whiteboards – innumerable Chat – ICQ, AIM Visualization – CAPI, Shastra, Sieve Work flow – Team. Rooms, Groove Learning – Li. NC, Co. Vis Games – Diablo, Doom, World. Of. Warcraft, There Toolkits – Habanero, Tango, Group. Kit

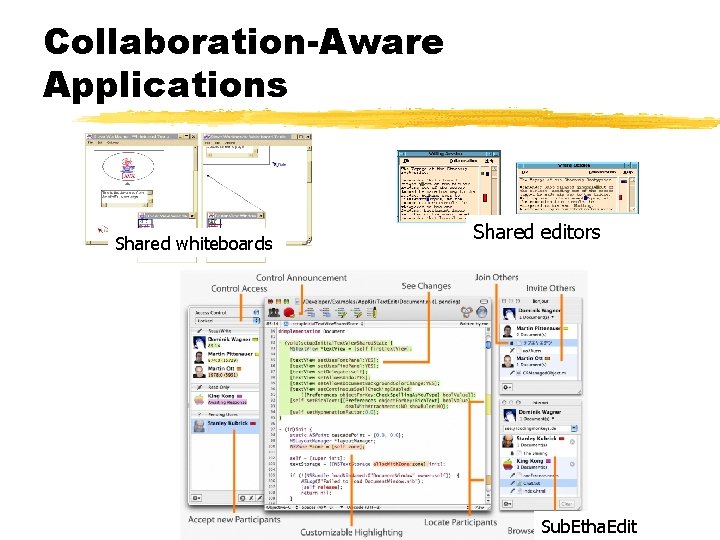

Collaboration-Aware Applications Shared whiteboards Shared editors Sub. Etha. Edit

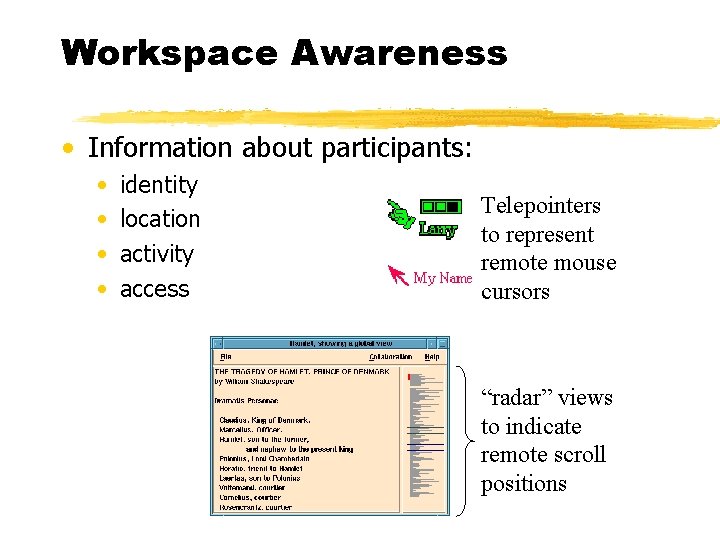

Workspace Awareness • Information about participants: • • identity location activity access Telepointers to represent remote mouse cursors “radar” views to indicate remote scroll positions

Replicated Architecture User A Host User Appli. Display Input cation User B Host User Appli- Display Input cation Network Traffic Conference Agent Merged Input Conference Agent Host Event Broadcaster • • Copy on each host Remote inputs merged Inputs distributed Enables: • Lower network bandwidth • Independent views • Concurrent work

Can We Achieve Spontaneous Collaboration? • Co-workers “encounter” each other • Accessing shared content, docs, code, etc. • Within shared events, web sites, meetings, etc. • Applications morph into collaborative versions on-the-fly • Research prototypes • Flexible JAMM [Begole et al. 99] • Zipper [IBM] • Co-Word/Co-Power. Point [Griffith U. ]

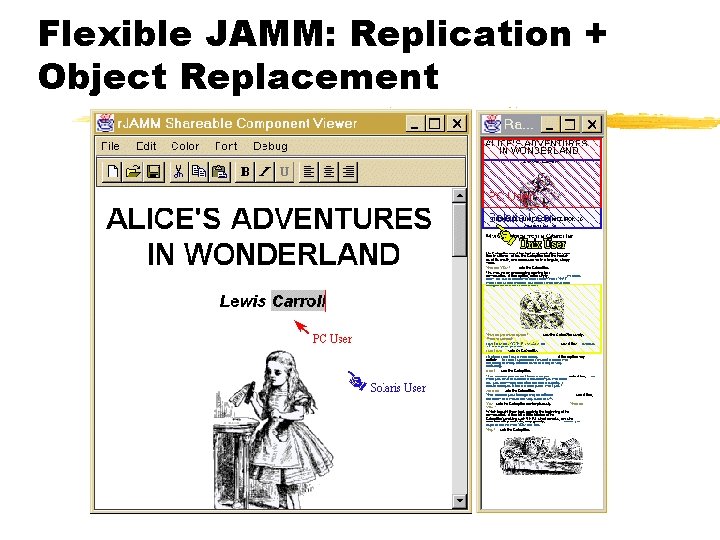

Flexible JAMM: Replication + Object Replacement

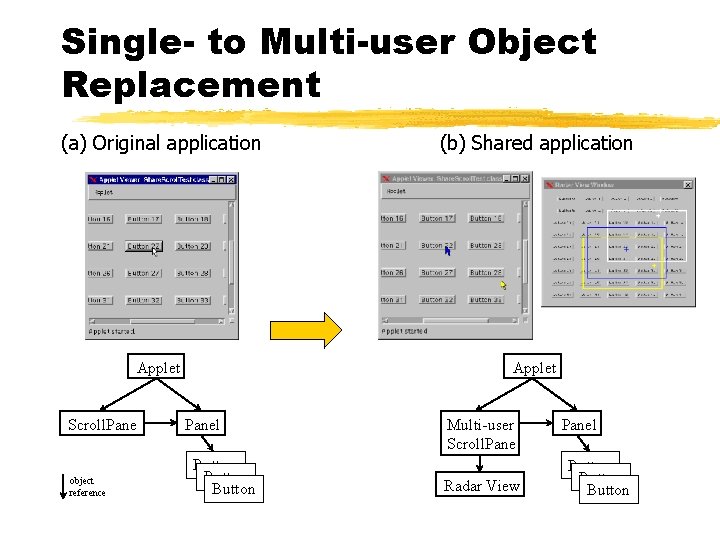

Single- to Multi-user Object Replacement (a) Original application (b) Shared application Applet Scroll. Pane object reference Panel Button Multi-user Scroll. Pane Radar View Panel Button

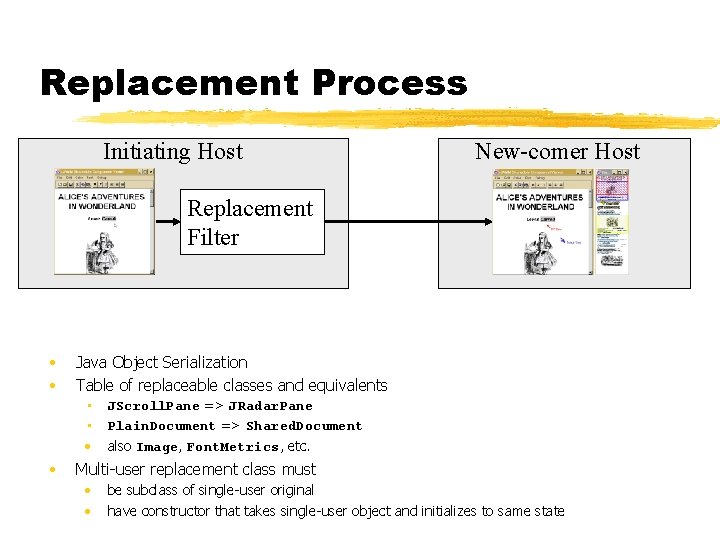

Replacement Process Initiating Host New-comer Host Replacement Filter • • Java Object Serialization Table of replaceable classes and equivalents • JScroll. Pane => JRadar. Pane • Plain. Document => Shared. Document • also Image, Font. Metrics, etc. • Multi-user replacement class must • • be subclass of single-user original have constructor that takes single-user object and initializes to same state

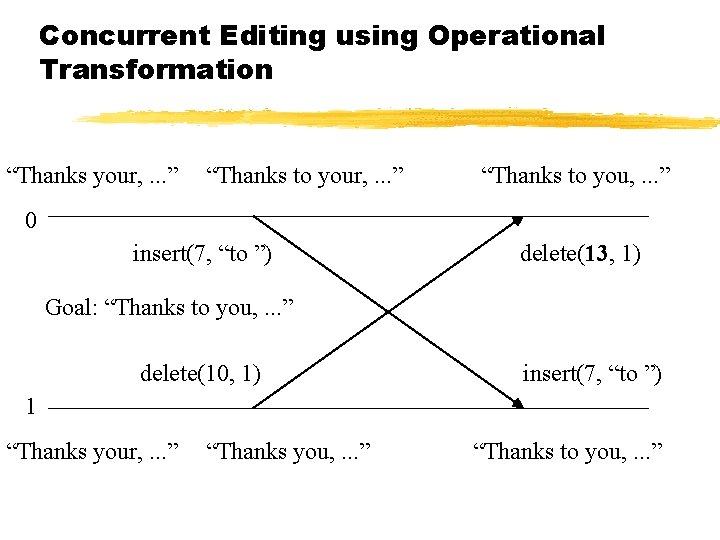

Concurrent Editing using Operational Transformation “Thanks your, . . . ” “Thanks to you, . . . ” 0 insert(7, “to ”) delete(10, delete(13, 1) Goal: “Thanks to you, . . . ” delete(10, 1) insert(7, “to ”) 1 “Thanks your, . . . ” “Thanks you, . . . ” “Thanks to you, . . . ”

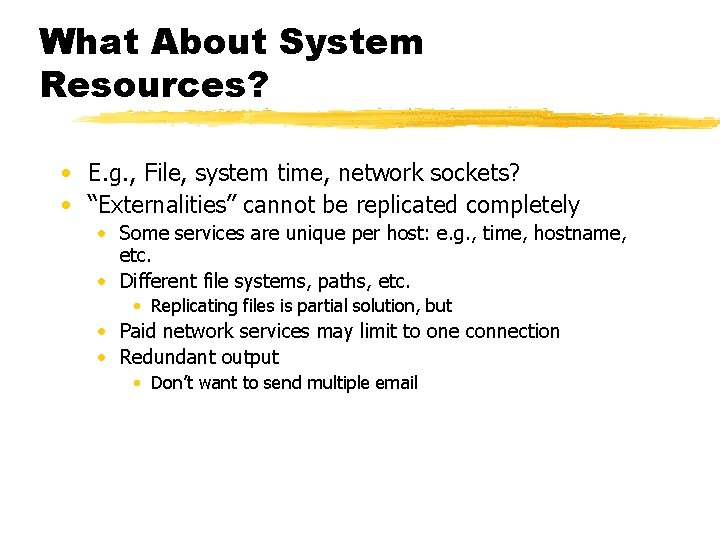

What About System Resources? • E. g. , File, system time, network sockets? • “Externalities” cannot be replicated completely • Some services are unique per host: e. g. , time, hostname, etc. • Different file systems, paths, etc. • Replicating files is partial solution, but • Paid network services may limit to one connection • Redundant output • Don’t want to send multiple email

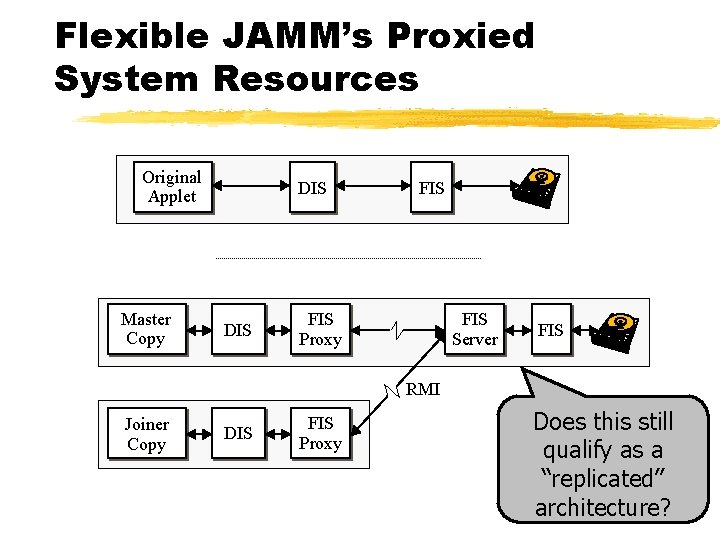

Flexible JAMM’s Proxied System Resources Original Applet Master Copy DIS FIS Proxy FIS Server FIS RMI Joiner Copy DIS FIS Proxy Does this still qualify as a “replicated” architecture?

Does it Work? Could it Introduce Problems? • Flexible JAMM versus Net. Meeting • Two tasks • Loosely-coupled collaboration - Text Entry • Two authors simultaneously enter text • Tightly-coupled collaboration - Copy Edit • “Editor” leads “author” to correct errors in existing text • 8 pairs, with 35 wpm typing proficiency

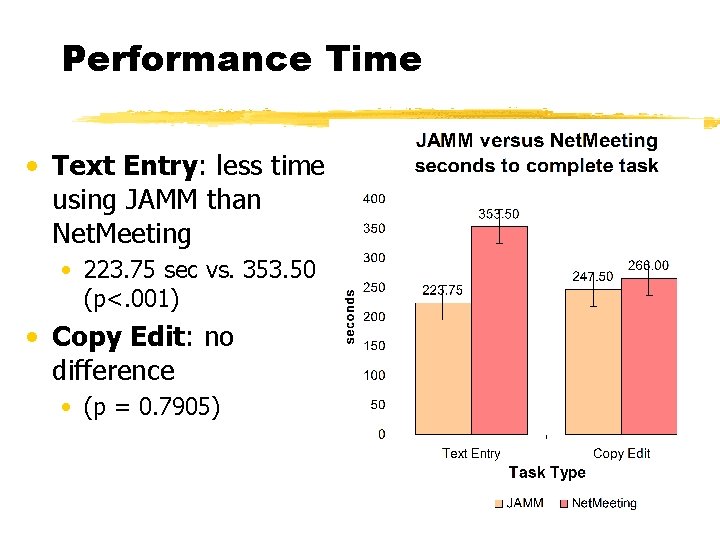

Performance Time • Text Entry: less time using JAMM than Net. Meeting • 223. 75 sec vs. 353. 50 (p<. 001) • Copy Edit: no difference • (p = 0. 7905)

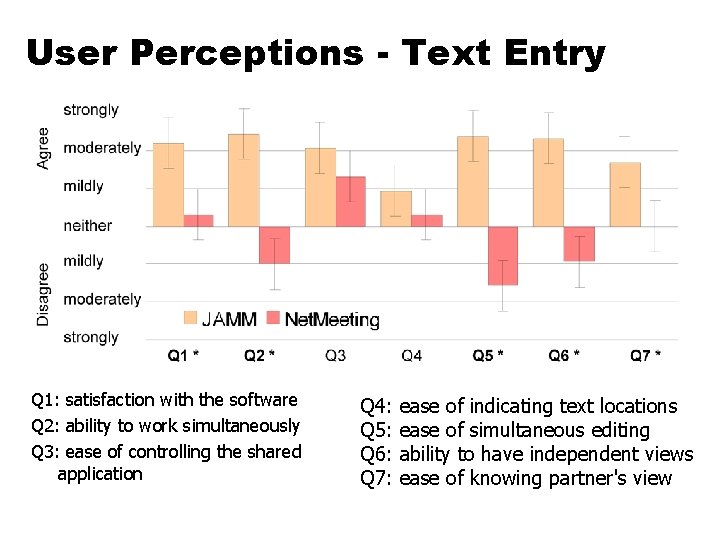

User Perceptions - Text Entry Q 1: satisfaction with the software Q 2: ability to work simultaneously Q 3: ease of controlling the shared application Q 4: Q 5: Q 6: Q 7: ease of indicating text locations ease of simultaneous editing ability to have independent views ease of knowing partner's view

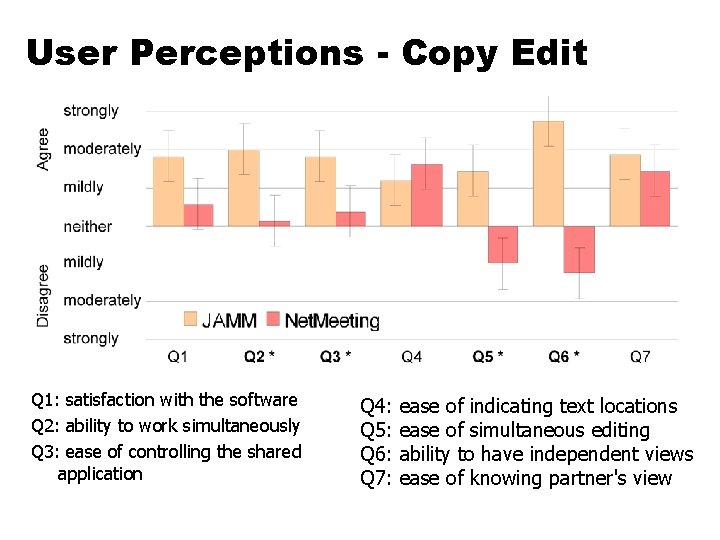

User Perceptions - Copy Edit Q 1: satisfaction with the software Q 2: ability to work simultaneously Q 3: ease of controlling the shared application Q 4: Q 5: Q 6: Q 7: ease of indicating text locations ease of simultaneous editing ability to have independent views ease of knowing partner's view

Evaluation - other results • • • No difference in accuracy JAMM preferred for Text Entry Neither preferred for Copy Edit JAMM preferred overall Net. Meeting floor control mechanism is difficult for people to use

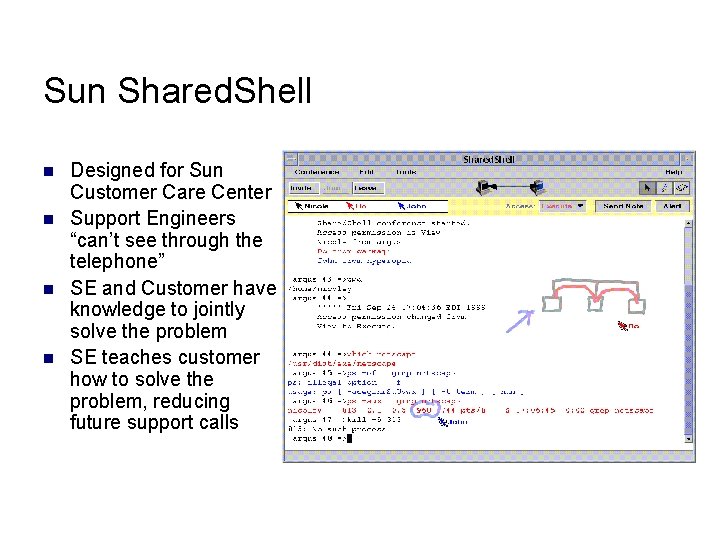

Sun Shared. Shell n n Designed for Sun Customer Care Center Support Engineers “can’t see through the telephone” SE and Customer have knowledge to jointly solve the problem SE teaches customer how to solve the problem, reducing future support calls

Shared. Shell Video n Yankelovich, N. , “Bo” Begole, J. , and Tang, J. C. 2000. Sun Shared. Shell tool. In Proceedings of the 2000 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States). CSCW '00. ACM Press, New York, NY, 351. DOI= http: //doi. acm. org/10. 1145/358916. 361981

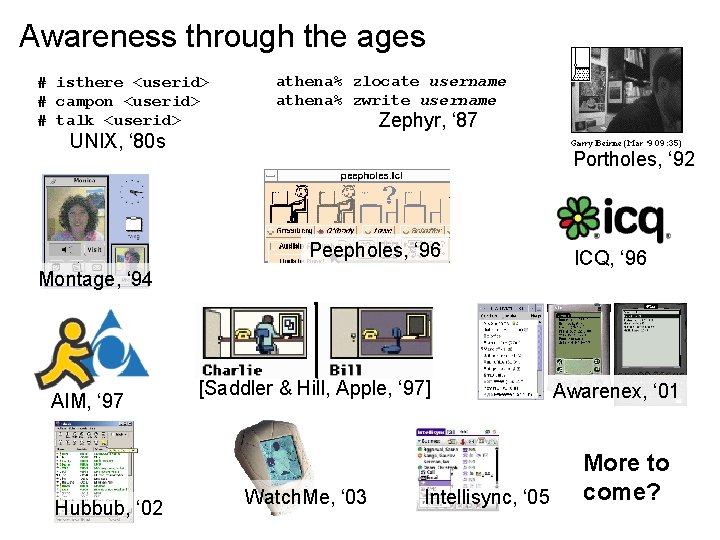

Awareness through the ages # isthere <userid> # campon <userid> # talk <userid> athena% zlocate username athena% zwrite username Zephyr, ‘ 87 UNIX, ‘ 80 s Portholes, ‘ 92 Peepholes, ‘ 96 Montage, ‘ 94 AIM, ‘ 97 Hubbub, ‘ 02 [Saddler & Hill, Apple, ‘ 97] Watch. Me, ‘ 03 Intellisync, ‘ 05 ICQ, ‘ 96 Awarenex, ‘ 01 More to come?

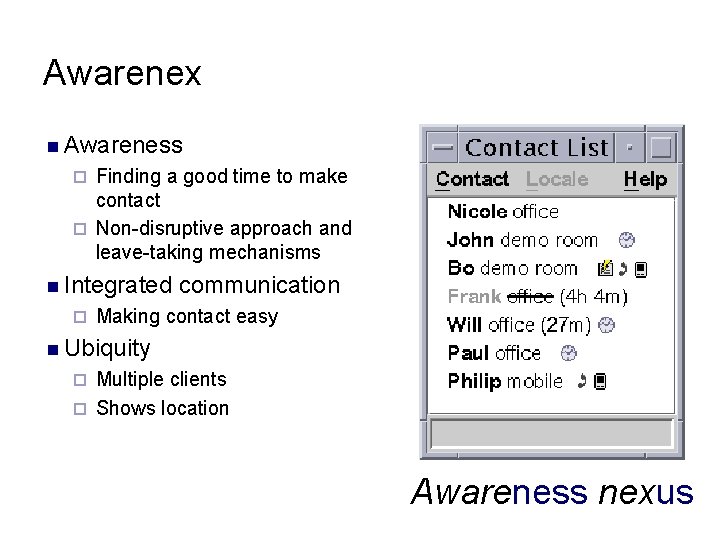

Awarenex n Awareness Finding a good time to make contact ¨ Non-disruptive approach and leave-taking mechanisms ¨ n Integrated ¨ communication Making contact easy n Ubiquity Multiple clients ¨ Shows location ¨ Awareness nexus

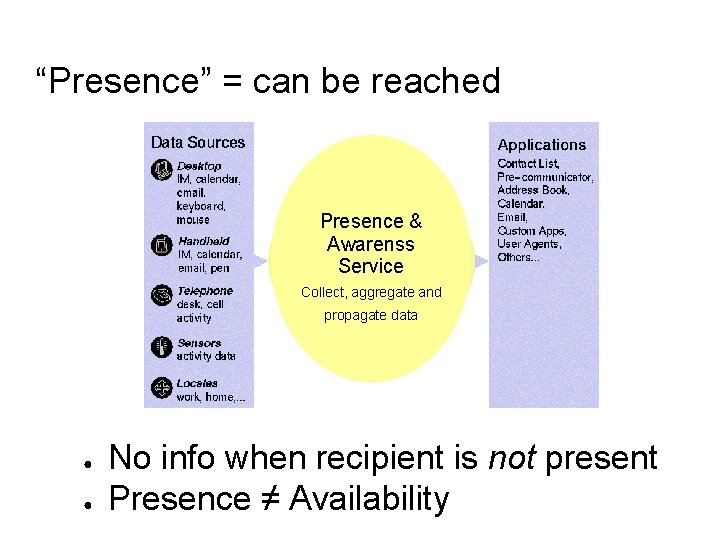

“Presence” = can be reached Presence & Awarenss Service Collect, aggregate and propagate data ● ● No info when recipient is not present Presence ≠ Availability

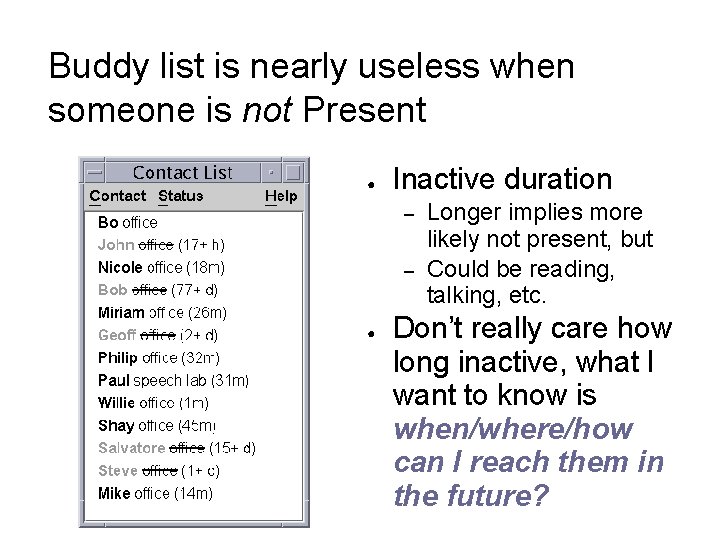

Buddy list is nearly useless when someone is not Present ● Inactive duration – – ● Longer implies more likely not present, but Could be reading, talking, etc. Don’t really care how long inactive, what I want to know is when/where/how can I reach them in the future?

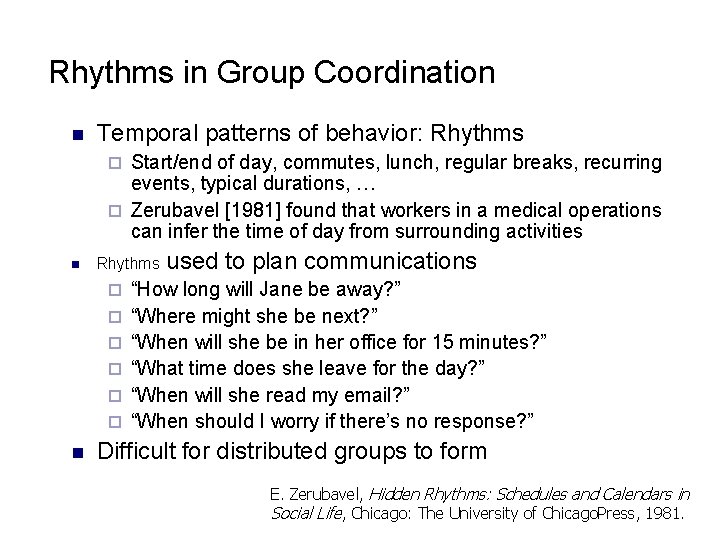

Rhythms in Group Coordination n Temporal patterns of behavior: Rhythms Start/end of day, commutes, lunch, regular breaks, recurring events, typical durations, … ¨ Zerubavel [1981] found that workers in a medical operations can infer the time of day from surrounding activities ¨ n Rhythms ¨ ¨ ¨ n used to plan communications “How long will Jane be away? ” “Where might she be next? ” “When will she be in her office for 15 minutes? ” “What time does she leave for the day? ” “When will she read my email? ” “When should I worry if there’s no response? ” Difficult for distributed groups to form E. Zerubavel, Hidden Rhythms: Schedules and Calendars in Social Life, Chicago: The University of Chicago. Press, 1981.

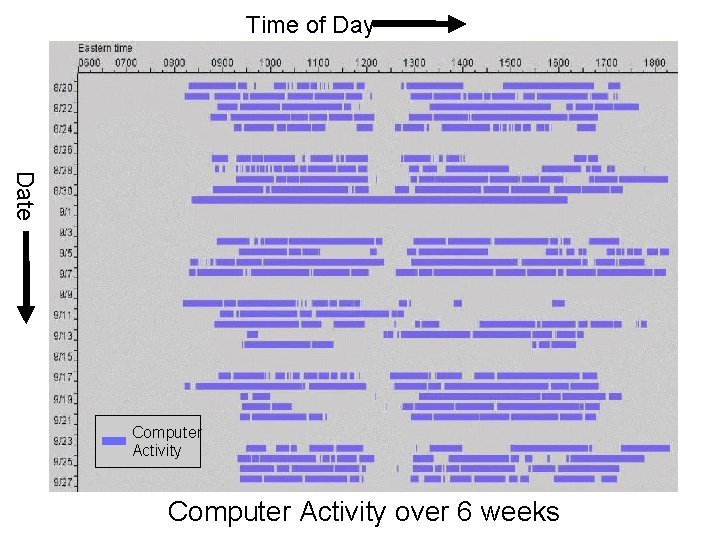

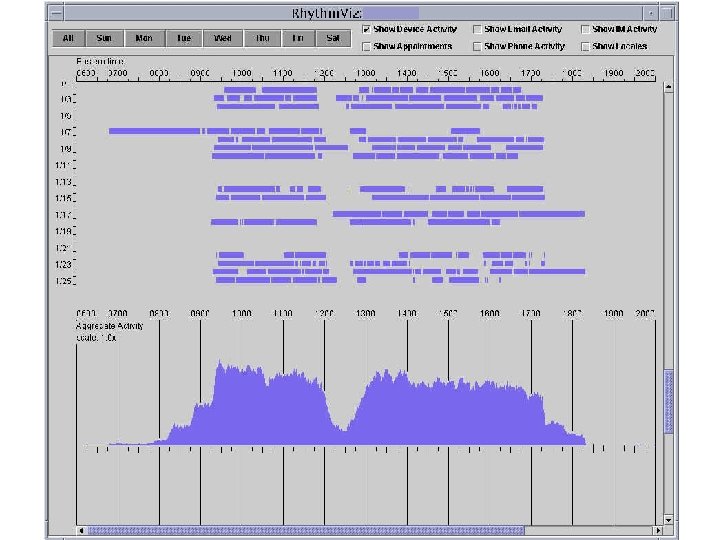

Time of Day Date Computer Activity over 6 weeks

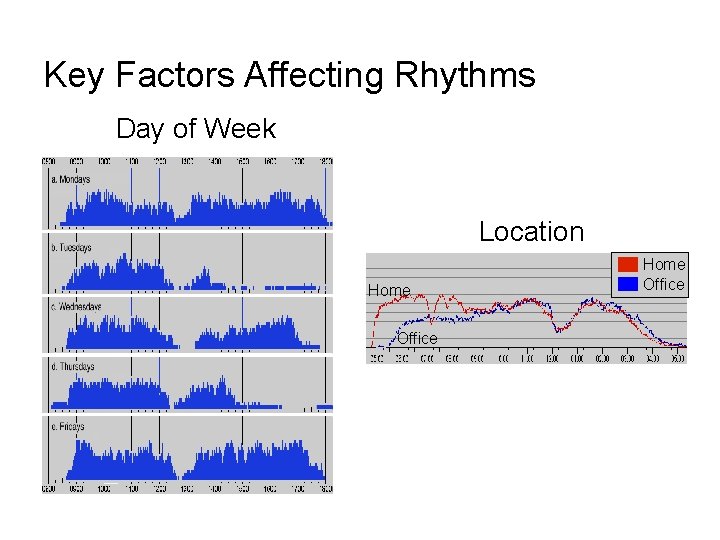

Key Factors Affecting Rhythms Day of Week Location Home Office

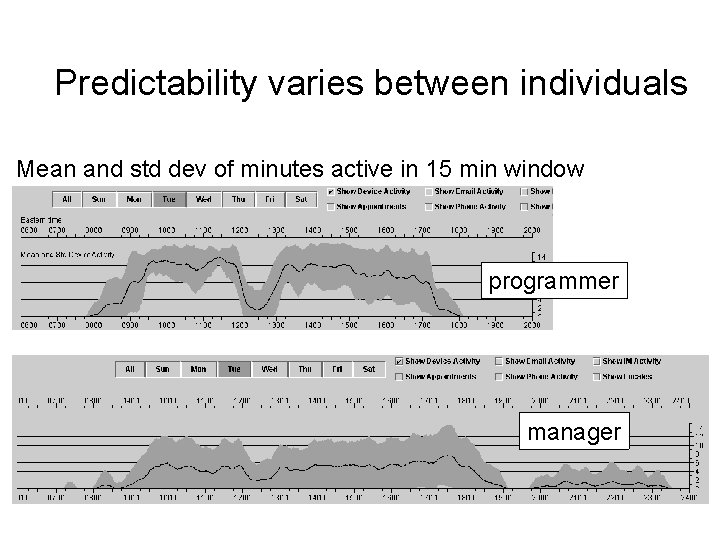

Predictability varies between individuals Mean and std dev of minutes active in 15 min window programmer manager

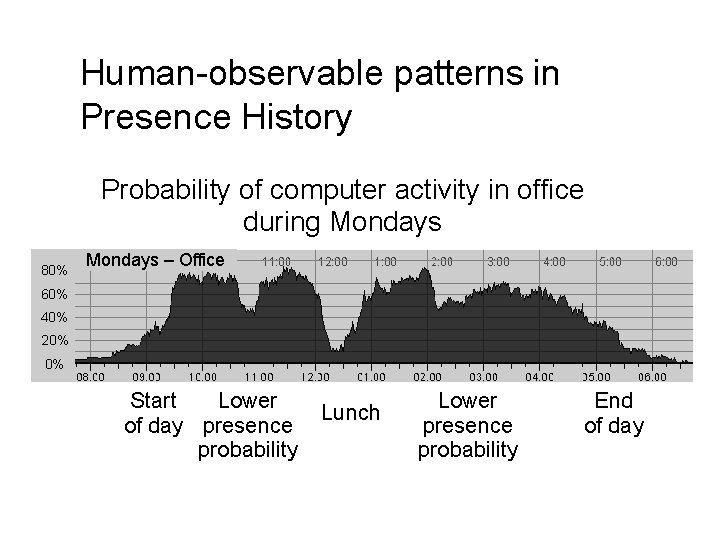

Human-observable patterns in Presence History Probability of computer activity in office during Mondays 80% Mondays – Office 60% 40% 20% 0% Start Lower of day presence probability Lunch Lower presence probability End of day

![Modeling Approaches Bayesian Network Decision Tree [Horvitz, et al. 2002] Difficult for end-users (and Modeling Approaches Bayesian Network Decision Tree [Horvitz, et al. 2002] Difficult for end-users (and](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/380bcd7089505bc09581752378cc6494/image-40.jpg)

Modeling Approaches Bayesian Network Decision Tree [Horvitz, et al. 2002] Difficult for end-users (and developers!) to interpret Temporal periodicity and patterns are not apparent to users

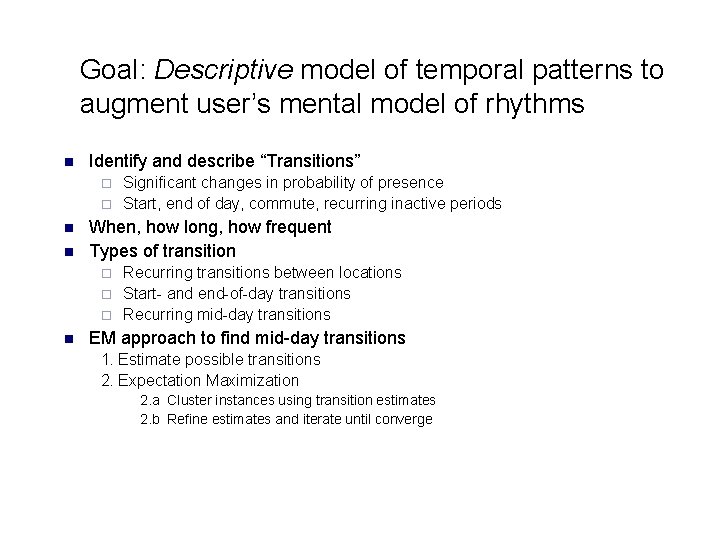

Goal: Descriptive model of temporal patterns to augment user’s mental model of rhythms n Identify and describe “Transitions” Significant changes in probability of presence ¨ Start, end of day, commute, recurring inactive periods ¨ n n When, how long, how frequent Types of transition Recurring transitions between locations ¨ Start- and end-of-day transitions ¨ Recurring mid-day transitions ¨ n EM approach to find mid-day transitions 1. Estimate possible transitions 2. Expectation Maximization 2. a Cluster instances using transition estimates 2. b Refine estimates and iterate until converge

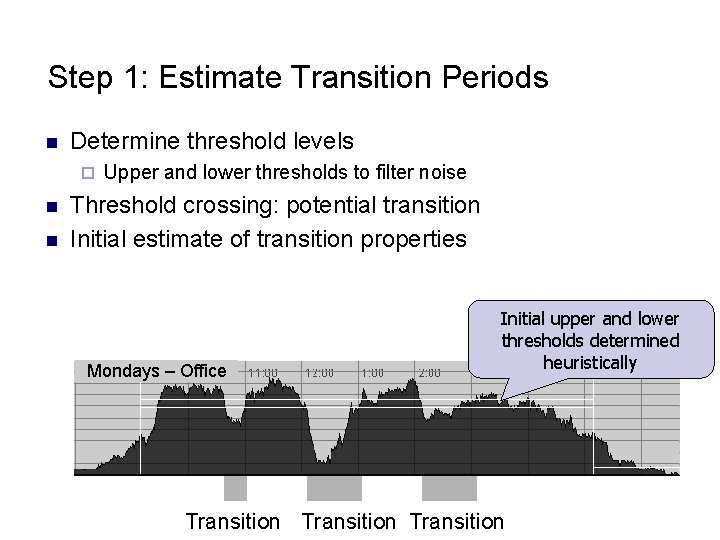

Step 1: Estimate Transition Periods n Determine threshold levels ¨ n n Upper and lower thresholds to filter noise Threshold crossing: potential transition Initial estimate of transition properties Mondays – Office Initial upper and lower thresholds determined heuristically Transition

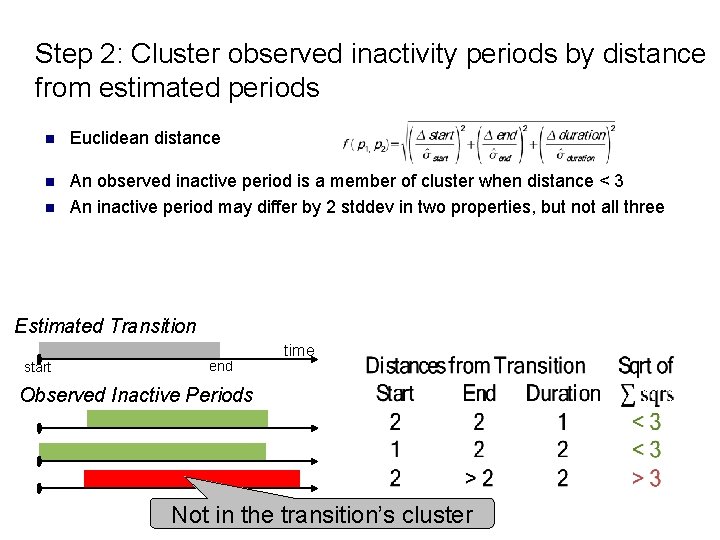

Step 2: Cluster observed inactivity periods by distance from estimated periods n Euclidean distance n An observed inactive period is a member of cluster when distance < 3 An inactive period may differ by 2 stddev in two properties, but not all three n Estimated Transition start end time Observed Inactive Periods Not in the transition’s cluster

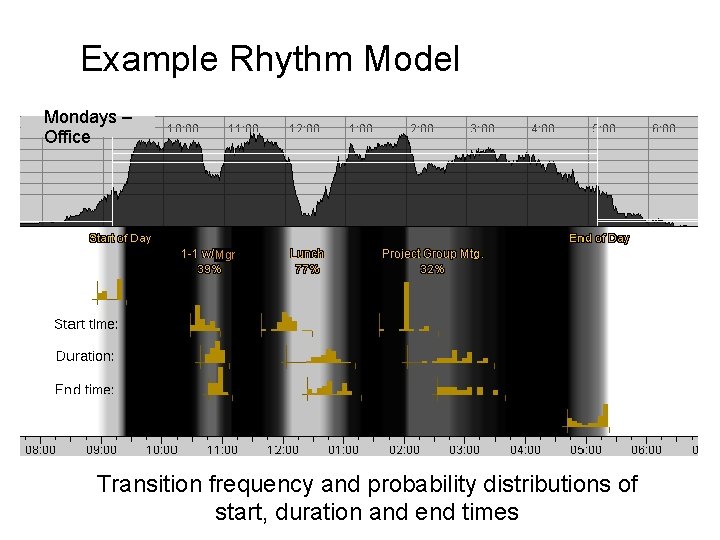

Example Rhythm Model Mondays – Office Mgr Transition frequency and probability distributions of start, duration and end times

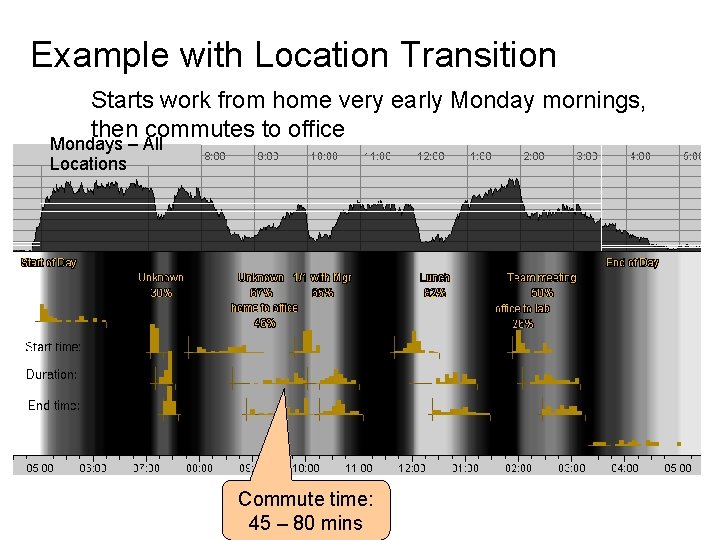

Example with Location Transition Starts work from home very early Monday mornings, then commutes to office Mondays – All Locations Commute time: 45 – 80 mins

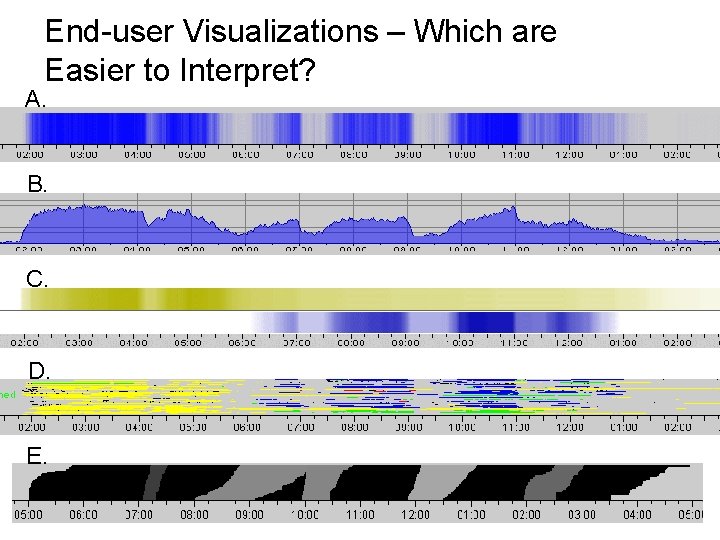

End-user Visualizations – Which are Easier to Interpret? A. B. C. D. E.

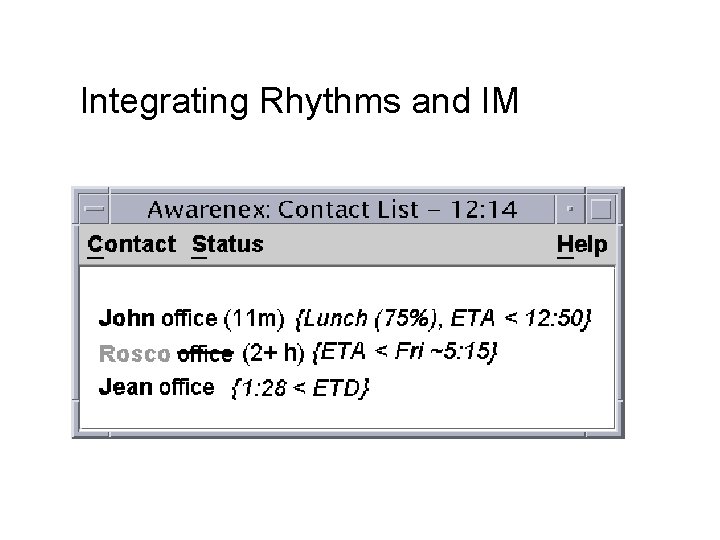

Integrating Rhythms and IM

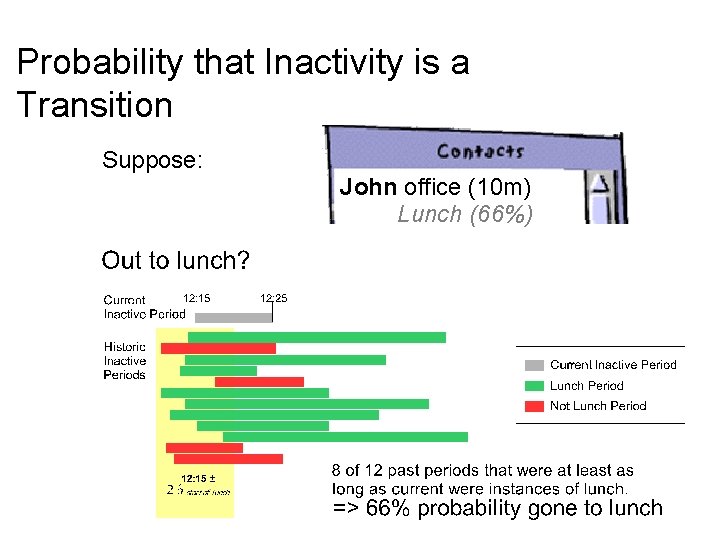

Probability that Inactivity is a Transition Suppose: John office (10 m) Lunch (66%)

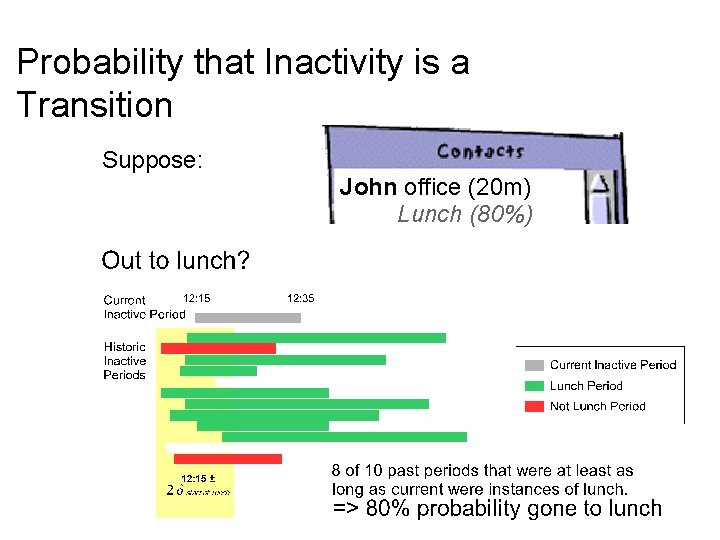

Probability that Inactivity is a Transition Suppose: John office (20 m) Lunch (80%)

Outline n n Presence and Non-Presence Rhythm Awareness – Modeling – Applications n n Availability and Unavailability Lilsys – Technical details – User reactions n Future Directions

Presence ≠ Availability n Interruptions are necessary – and welcome when related to current task [Sproull ’ 84, J. Hudson, et al. ’ 02] n But carry costs – 15 -20% of time spent on interrupts – £ 139 bn annual loss in UK (14. 6% GDP) [Solingen ‘ 98, Czerwinski ‘ 04, Gonzalez & Mark ‘ 04] [Brother Industries Ltd. 2005] » roughly $1. 75 tn US n Willingness to be interrupted depends on – Situation, activity, task, relation, topic, time, etc. n Inferencing based on situation can approach human accuracy [Fogarty 2004]

![Two philosophies on infering availability n Human interpretation [Saddler & Hill, 97] n Machine Two philosophies on infering availability n Human interpretation [Saddler & Hill, 97] n Machine](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/380bcd7089505bc09581752378cc6494/image-52.jpg)

Two philosophies on infering availability n Human interpretation [Saddler & Hill, 97] n Machine interpretation Awarenex

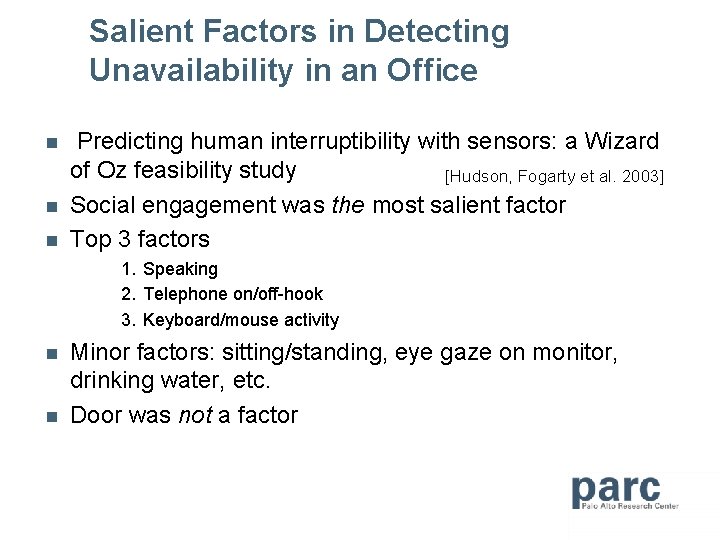

Salient Factors in Detecting Unavailability in an Office n n n Predicting human interruptibility with sensors: a Wizard of Oz feasibility study [Hudson, Fogarty et al. 2003] Social engagement was the most salient factor Top 3 factors 1. Speaking 2. Telephone on/off-hook 3. Keyboard/mouse activity n n Minor factors: sitting/standing, eye gaze on monitor, drinking water, etc. Door was not a factor

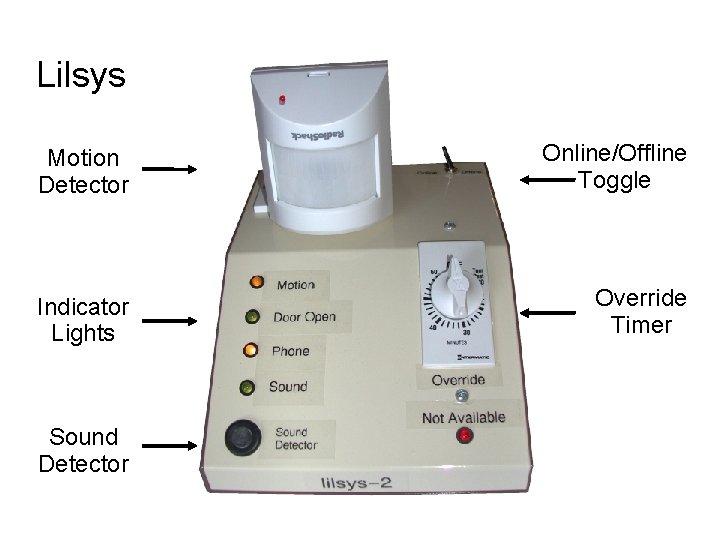

Lilsys Motion Detector Online/Offline Toggle Indicator Lights Override Timer Sound Detector

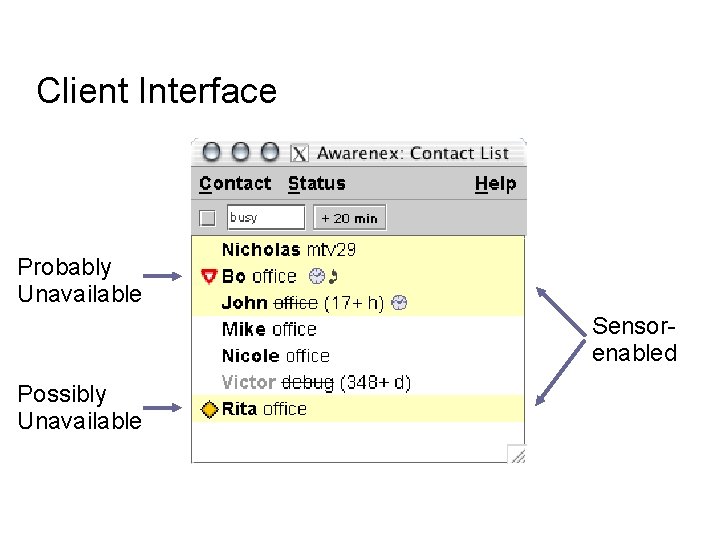

Client Interface Probably Unavailable Sensorenabled Possibly Unavailable

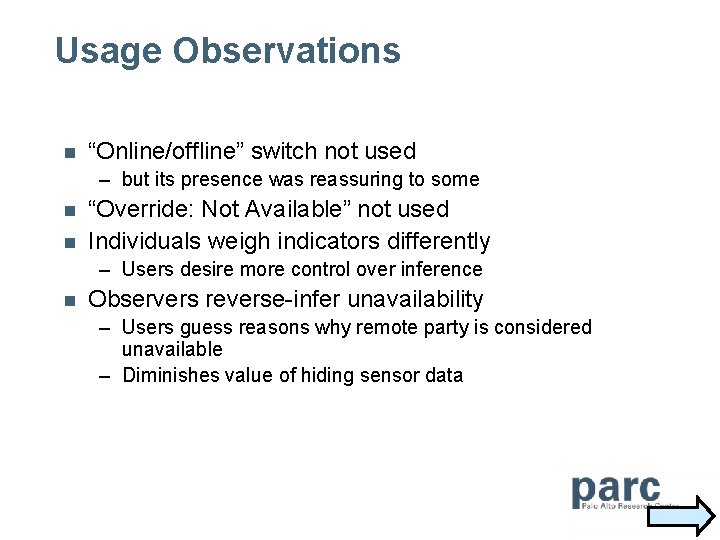

Usage Observations n “Online/offline” switch not used – but its presence was reassuring to some n n “Override: Not Available” not used Individuals weigh indicators differently – Users desire more control over inference n Observers reverse-infer unavailability – Users guess reasons why remote party is considered unavailable – Diminishes value of hiding sensor data

Did it work? n Can there ever be a good time to interrupt? – Users perceive same amount of interruption » Also found in My. Vine by Fogarty, Lai, Christensen 2004 – But the interrupter “approached” more politely n Interruptions in face-to-face – Approach is shaped by availability assessment – Both parties aware of degree of intrusion – Recipient gives feedback on appropriateness by being gracious or annoyed n n You can’t hold a caller accountable if they can’t be expected to know your interruptibility Availability inference helps contact negotiation

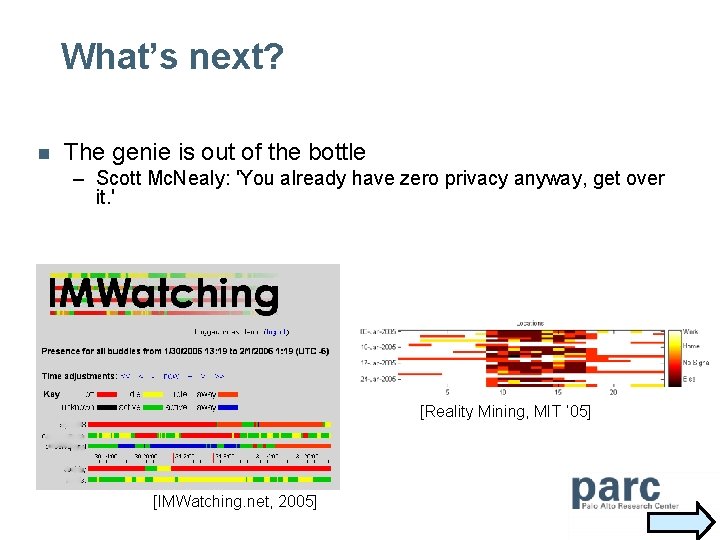

What’s next? n The genie is out of the bottle – Scott Mc. Nealy: 'You already have zero privacy anyway, get over it. ' [Reality Mining, MIT ’ 05] [IMWatching. net, 2005]

![Impression Management n Awareness complicates Impression Management [Goffman] – Harder to “give” intended impressions Impression Management n Awareness complicates Impression Management [Goffman] – Harder to “give” intended impressions](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/380bcd7089505bc09581752378cc6494/image-59.jpg)

Impression Management n Awareness complicates Impression Management [Goffman] – Harder to “give” intended impressions – Harder to know what is “given off” (i. e. , others see) – Harder to repair undesired impressions n Support impression management – – Show what others can and have seen Give user control of inference rules Modify personal data Give users “reverse Digital Rights Mgmt” » E. g. , if rhythm model shows Janet takes long lunches » Show that n n n Janet attends meetings during lunch Janet reads email from home in evenings Janet had the most sales last quarter, etc. How?

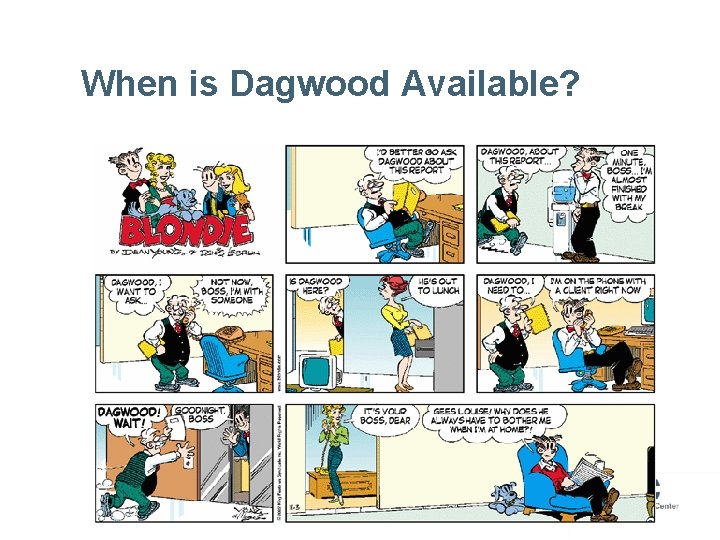

When is Dagwood Available?

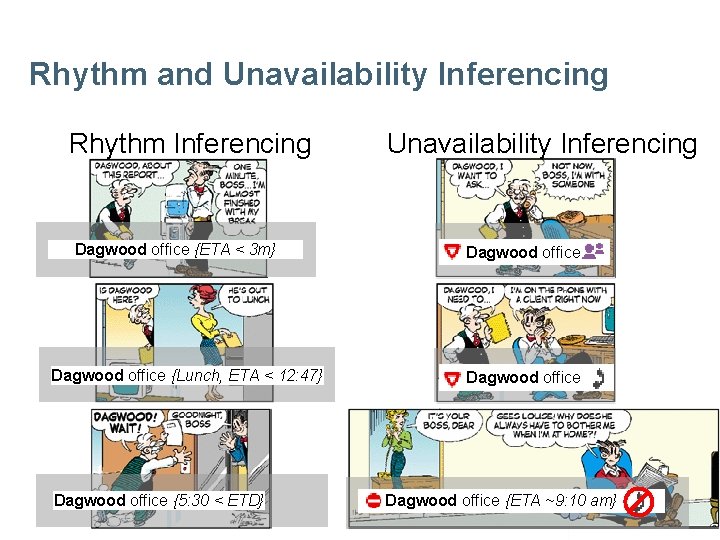

Rhythm and Unavailability Inferencing Rhythm Inferencing Dagwood office {ETA < 3 m} Dagwood office {Lunch, ETA < 12: 47} Dagwood office {5: 30 < ETD} Unavailability Inferencing Dagwood office {ETA ~9: 10 am}

Synchronous Collaboration and Awareness Systems Bo Begole Ubiquitous Computing Area Manager Computer Science Lab

References n n n "Incorporating Human and Machine Interpretation of Unavailability and Rhythm Awareness into the Design of Collaborative Applications", James "Bo" Begole and John C. Tang, to appear in HCI Journal. “If Not Now, When? : The Effects of Interruption at Different Moments in Task Execution”, P. Adamczyk & B. Bailey, CHI 2004 "Beyond Instant Messaging", J. Tang & J. Begole, ACM Queue, (1)8, Nov 2003, pp. 28 -37 “Lilsys: Sensing Unavialability”, J. Begole, N. Matsakis and J. Tang, Technical Note in CSCW 2004, to appear “Rhythm Modeling, Visualizations and Applications”, J. Begole, J. Tang, and R. Hill, UIST 2003 “Work Rhythms: Analyzing Visualizations of Awareness Histories”, Begole, Tang, Smith & Yankelovich, CSCW 2002 “Coordinate: Probabilistic Forecasting of Presence and Availability”, E. Horvitz, P. Koch, C. Kadie, A. Jacobs, UAI 2002 “'I’d Be Overwhelmed, But It’s Just One More Thing to Do: ' Availability and Interruption in Research Management”, J. Hudson, J. Christensen, W. Kellogg, and T. Erickson, CHI 2002 “Predicting Human Interruptibility with Sensors”, S. Hudson, J. Fogarty, C. Atkeson, J. Forlizzi, S. Kiesler, J. Lee, J. Yang, CHI 2003 “The time famine: Toward a sociology of work time”, L. Perlow, Administrative Science Quarterly, 44, (1999), 57 -81. “When Can I Expect an Email Response? A Study of Rhythms in Email Usage”, J. Tyler and J. Tang, ECSCW 2003 Hidden Rhythms: Schedules and Calendars in Social Life, E. Zerubavel, 1981

- Slides: 63