Symbolic vs Subsymbolic Connectionism an Introduction H Bowman

Symbolic vs Subsymbolic, Connectionism (an Introduction) H. Bowman (CCNCS, Kent)

Overview • Follow up to first symbolic – subsymbolic talk • Motivation, – clarify why (typically) connectionist networks are not compositional – introduce connectionism, • link to biology • activation dynamics • learning algorithms

Recap

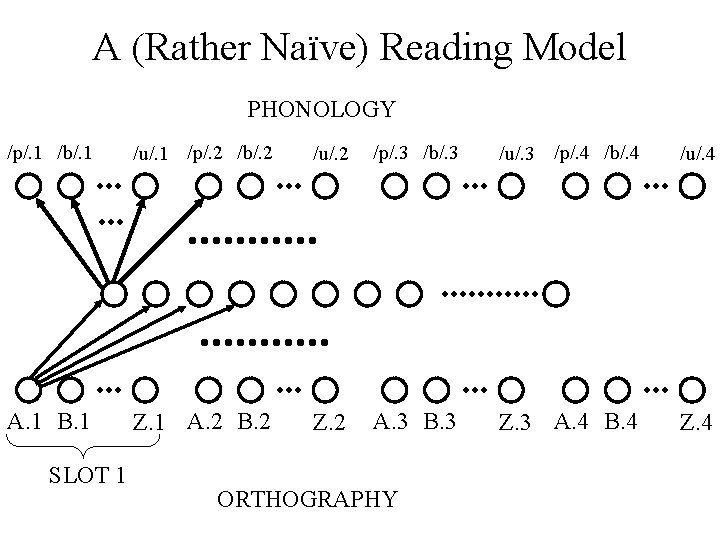

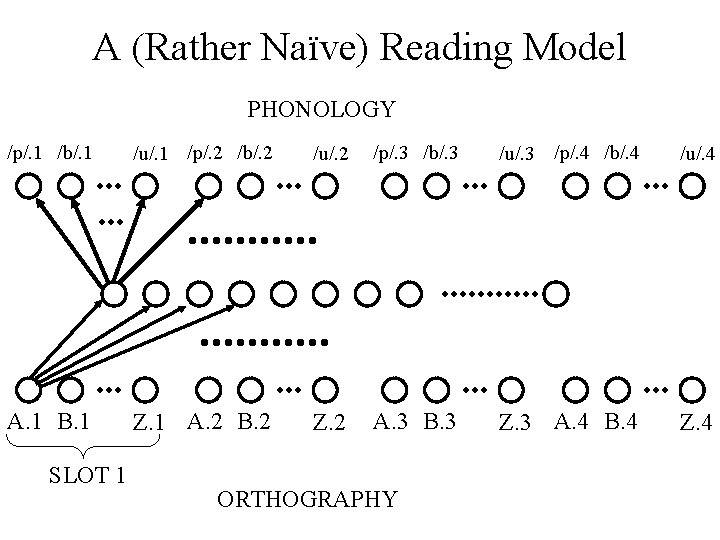

A (Rather Naïve) Reading Model PHONOLOGY /p/. 1 /b/. 1 /u/. 1 /p/. 2 /b/. 2 /u/. 2 /p/. 3 /b/. 3 /u/. 3 /p/. 4 /b/. 4 /u/. 4 A. 1 B. 1 Z. 1 A. 2 B. 2 Z. 2 A. 3 B. 3 Z. 3 A. 4 B. 4 Z. 4 SLOT 1 ORTHOGRAPHY

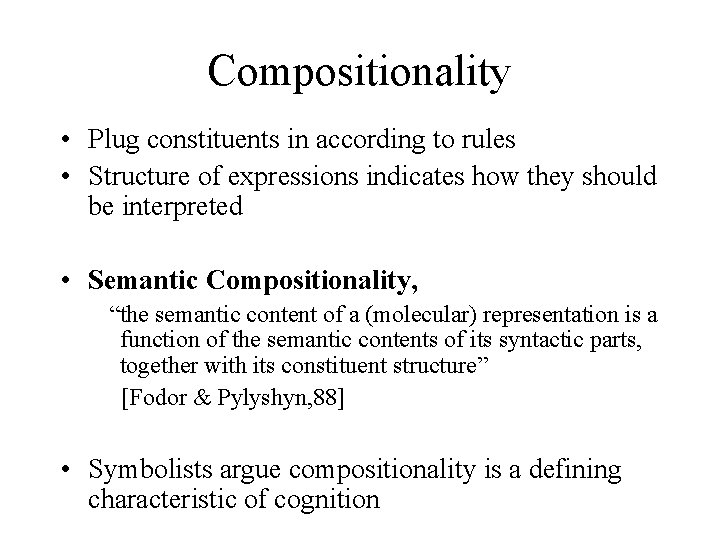

Compositionality • Plug constituents in according to rules • Structure of expressions indicates how they should be interpreted • Semantic Compositionality, “the semantic content of a (molecular) representation is a function of the semantic contents of its syntactic parts, together with its constituent structure” [Fodor & Pylyshyn, 88] • Symbolists argue compositionality is a defining characteristic of cognition

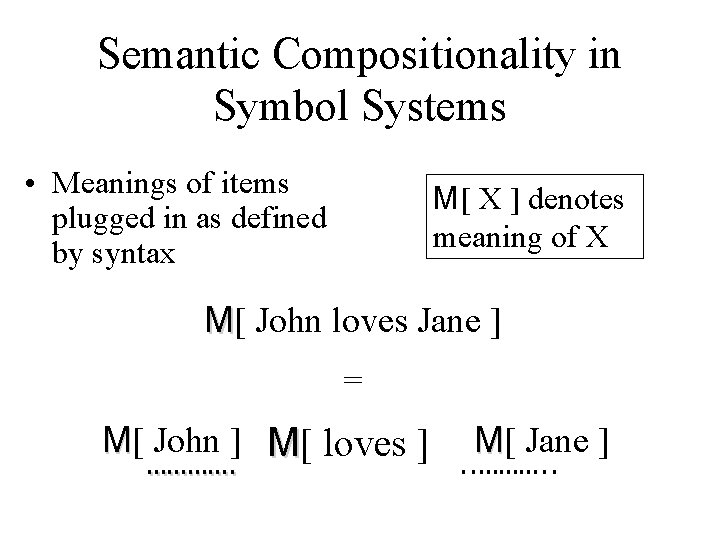

Semantic Compositionality in Symbol Systems • Meanings of items plugged in as defined by syntax M[ X ] denotes meaning of X M[ John loves Jane ] = M[ John ] M[ loves ] M[ Jane ] …………. .

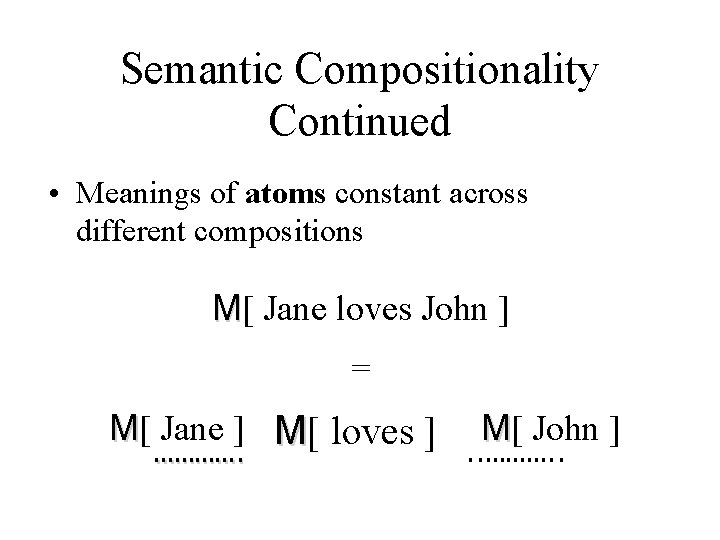

Semantic Compositionality Continued • Meanings of atoms constant across different compositions M[ Jane loves John ] = M[ Jane ] M[ loves ] M[ John ] …………. .

The Sub-symbolic Tradition

Rate Coding Hypothesis • Biological neurons fire spikes (pulses of current) • In artificial neural networks, – nodes reflect populations of biological neurons acting together, i. e. cell assemblies; – activation reflects rate of spiking of underlying biological neurons.

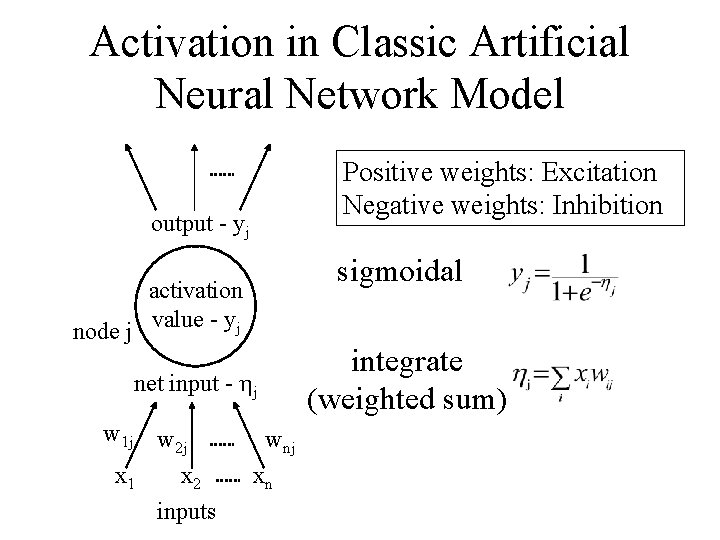

Activation in Classic Artificial Neural Network Model Positive weights: Excitation Negative weights: Inhibition output - yj sigmoidal activation node j value - yj integrate (weighted sum) net input - hj w 1 j x 1 w 2 j x 2 inputs wnj xn

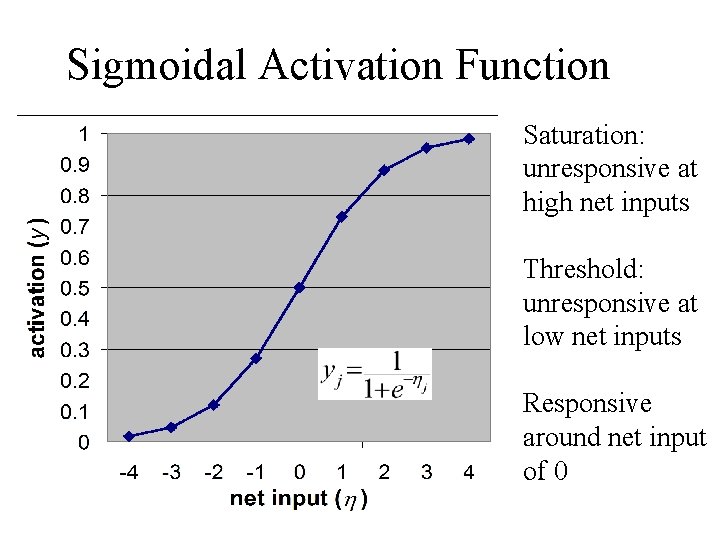

Sigmoidal Activation Function Saturation: unresponsive at high net inputs Threshold: unresponsive at low net inputs Responsive around net input of 0

Characteristics • Nodes homogeneous and essentially dumb • Input weights characterize what a node represents / detects • Sophisticated (intelligent? ) behaviour emerges from interaction amongst nodes

Learning • directed weight adjustment • two basic approaches, – Hebbian learning, • unsupervised • extracting regularities from environment – error-driven learning, • supervised • learn an input to output mapping

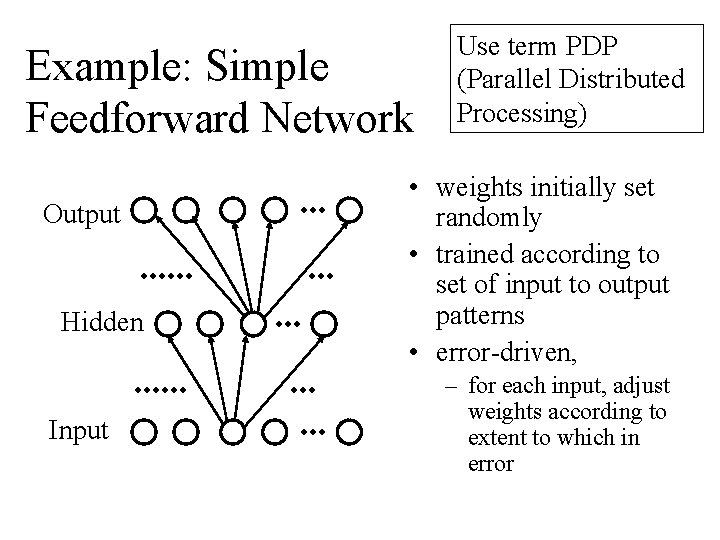

Example: Simple Feedforward Network Output Hidden Input Use term PDP (Parallel Distributed Processing) • weights initially set randomly • trained according to set of input to output patterns • error-driven, – for each input, adjust weights according to extent to which in error

Error-driven Learning • can learn any (computable) input-output mapping (modulo local minima) • delta rule and back-propagation • network learning completely determined by patterns presented to it

Example Connectionist Model • “Jane Loves John” difficult to represent in PDP models • Word reading as an example – orthography to phonology • Words of four letters or less • Need to represent order of letters, otherwise, e. g. slot and lots the same • Slot coding

A (Rather Naïve) Reading Model PHONOLOGY /p/. 1 /b/. 1 /u/. 1 /p/. 2 /b/. 2 /u/. 2 /p/. 3 /b/. 3 /u/. 3 /p/. 4 /b/. 4 /u/. 4 A. 1 B. 1 Z. 1 A. 2 B. 2 Z. 2 A. 3 B. 3 Z. 3 A. 4 B. 4 Z. 4 SLOT 1 ORTHOGRAPHY

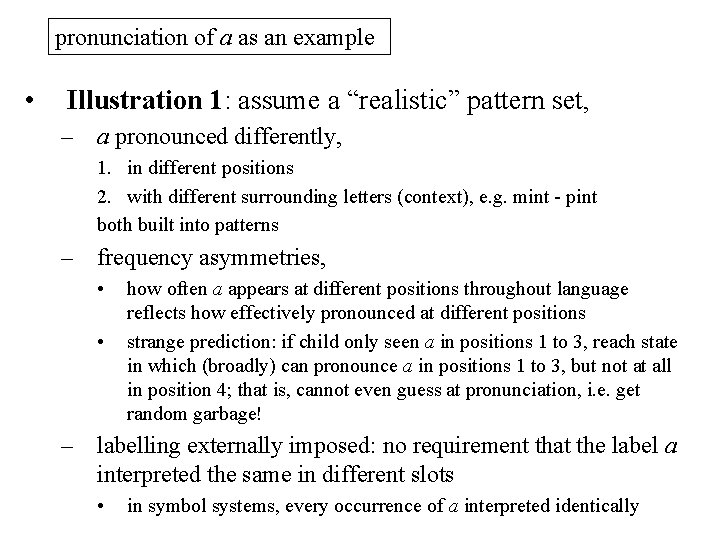

pronunciation of a as an example • Illustration 1: assume a “realistic” pattern set, – a pronounced differently, 1. in different positions 2. with different surrounding letters (context), e. g. mint - pint both built into patterns – frequency asymmetries, • • how often a appears at different positions throughout language reflects how effectively pronounced at different positions strange prediction: if child only seen a in positions 1 to 3, reach state in which (broadly) can pronounce a in positions 1 to 3, but not at all in position 4; that is, cannot even guess at pronunciation, i. e. get random garbage! – labelling externally imposed: no requirement that the label a interpreted the same in different slots • in symbol systems, every occurrence of a interpreted identically

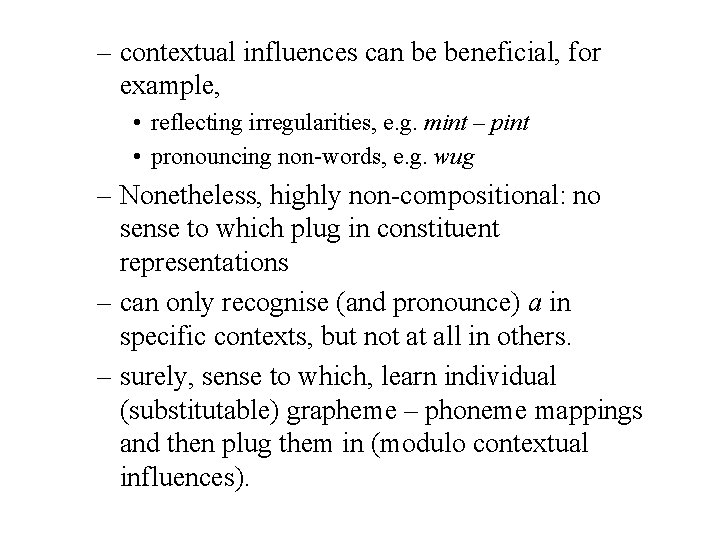

– contextual influences can be beneficial, for example, • reflecting irregularities, e. g. mint – pint • pronouncing non-words, e. g. wug – Nonetheless, highly non-compositional: no sense to which plug in constituent representations – can only recognise (and pronounce) a in specific contexts, but not at all in others. – surely, sense to which, learn individual (substitutable) grapheme – phoneme mappings and then plug them in (modulo contextual influences).

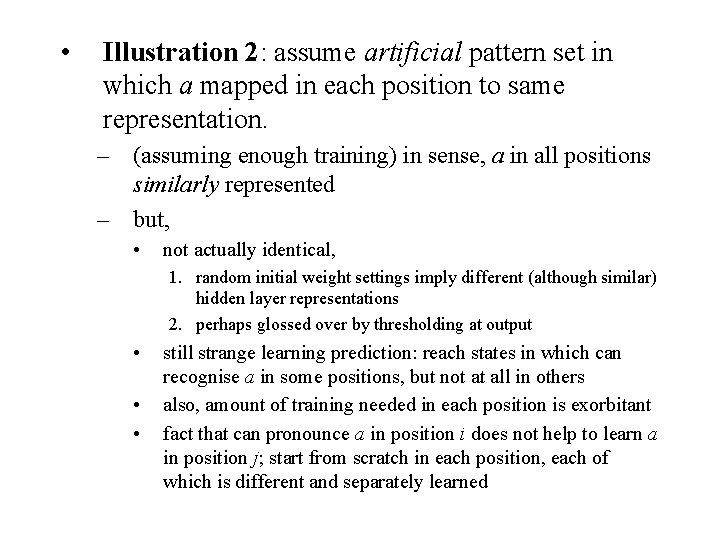

• Illustration 2: assume artificial pattern set in which a mapped in each position to same representation. – (assuming enough training) in sense, a in all positions similarly represented – but, • not actually identical, 1. random initial weight settings imply different (although similar) hidden layer representations 2. perhaps glossed over by thresholding at output • • • still strange learning prediction: reach states in which can recognise a in some positions, but not at all in others also, amount of training needed in each position is exorbitant fact that can pronounce a in position i does not help to learn a in position j; start from scratch in each position, each of which is different and separately learned

Connectionism & Compositionality • Principle: – with PDP nets, contextual influence inherent, compositionality the exception – with symbol systems, compositionality inherent, contextual influence the exception • in some respects neural nets generalise well, but in other respects generalise badly. – appropriate: global regularities across patterns extracted (similar patterns treated similarly) – inappropriate: with slot coding, component representations not reused

Connectionism & Compositionality • alternative connectionist models may do better, but not clear that any is truly systematic in sense of symbolic processing • alternative approaches, – localist models, e. g. Interactive Activation or Activation Gradient models – O’Reilly’s spatial invariance model of word reading? – Elman nets – recurrence for learning sequences.

References • • • Anderson, J. R. (1993). Rules of the Mind. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Bowers, J. S. (2002). Challenging the widespread assumption that connectionism and distributed representations go hand-in-hand. Cognitive Psychology. , 45, 413 -445. Evans, J. S. B. T. (2003). In Two Minds: Dual Process Accounts of Reasoning. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 7(10), 454 -459. Fodor, J. A. , & Pylyshyn, Z. W. (1988). Connectionism and Cognitive Architecture: A Critical Analysis. Cognition, 28, 3 -71. Hinton, G. E. (1990). Special Issue of Journal Artificial Intelligence on Connectionist Symbol Processing (edited by Hinton, G. E. ). Artificial Intelligence, 46(1 -4). O'Reilly, R. C. , & Munakata, Y. (2000). Computational Explorations in Cognitive Neuroscience: Understanding the Mind by Simulating the Brain. : MIT Press. Mc. Clelland, J. L. (1992). Can Connectionist Models Discover the Structure of Natural Language? In R. Morelli, W. Miller Brown, D. Anselmi, K. Haberlandt & D. Lloyd (Eds. ), Minds, Brains and Computers: Perspectives in Cognitive Science and Artificial Intelligence (pp. 168 -189). Norwood, NJ. : Ablex Publishing Company. Mc. Clelland, J. L. (1995). A Connectionist Perspective on Knowledge and Development. In J. J. Simon & G. S. Halford (Eds. ), Developing Cognitive Competence: New Approaches to Process Modelling (pp. 157 -204). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Page, M. P. A. (2000). Connectionist Modelling in Psychology: A Localist Manifesto. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 23, 443 -512. Pinker, S. , Ullman, M. T. , Mc. Clelland, J. L. , & Patterson, K. (2002). The Past-Tense Debate (Series of Opinion Articles). Trends Cogn Sci, 6(11), 456 -474.

- Slides: 23