Switching Units Lecture 5 2 Types of switching

- Slides: 55

Switching Units Lecture 5 2

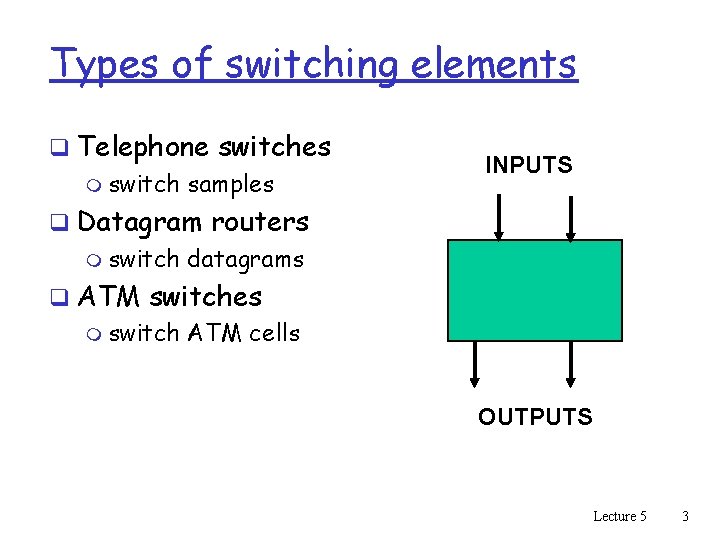

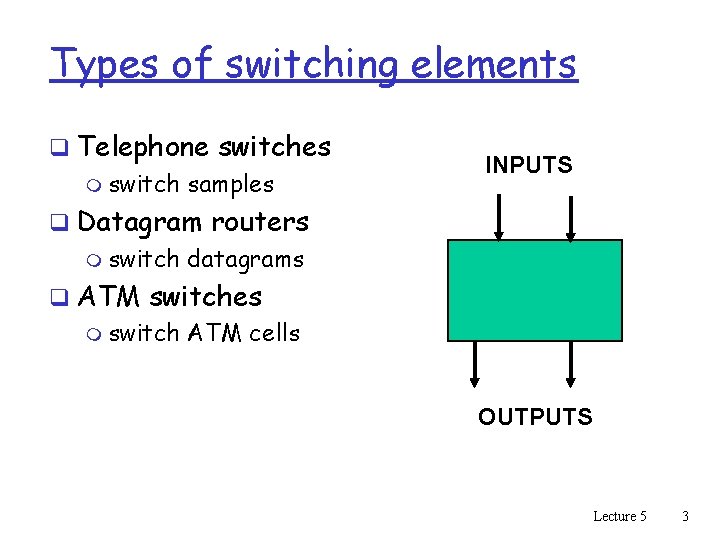

Types of switching elements q Telephone switches m switch samples INPUTS q Datagram routers m switch datagrams q ATM switches m switch ATM cells OUTPUTS Lecture 5 3

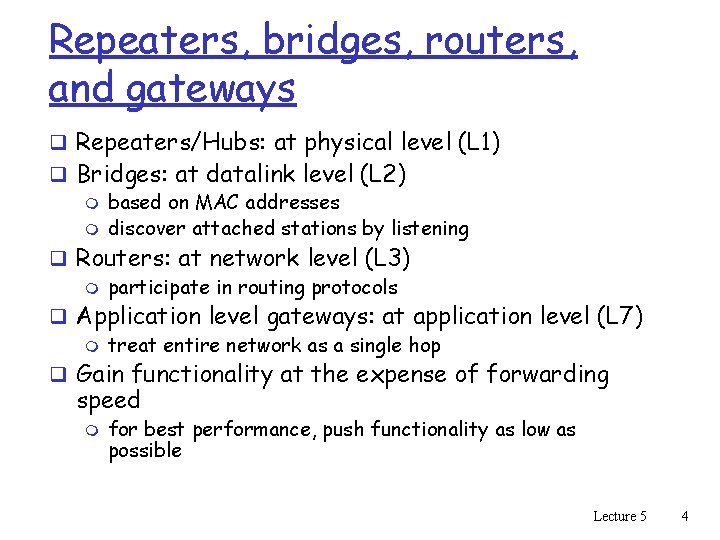

Repeaters, bridges, routers, and gateways q Repeaters/Hubs: at physical level (L 1) q Bridges: at datalink level (L 2) m based on MAC addresses m discover attached stations by listening q Routers: at network level (L 3) m participate in routing protocols q Application level gateways: at application level (L 7) m treat entire network as a single hop q Gain functionality at the expense of forwarding speed m for best performance, push functionality as low as possible Lecture 5 4

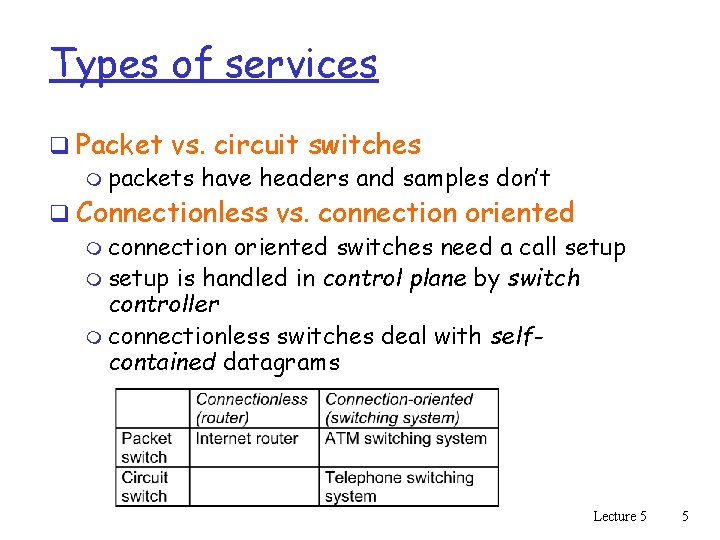

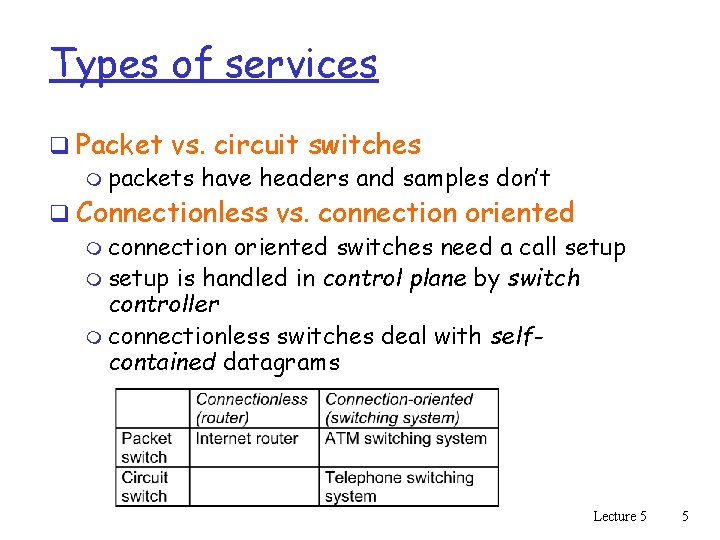

Types of services q Packet vs. circuit switches m packets have headers and samples don’t q Connectionless vs. connection oriented m connection oriented switches need a call setup m setup is handled in control plane by switch controller m connectionless switches deal with selfcontained datagrams Lecture 5 5

Other switching unit functions q Participate in routing algorithms m to build routing tables m Next Lecture! q Resolve contention for output trunks m buffer scheduling m Previous Lecture! q Admission control m to guarantee resources to certain streams Lecture 5 6

Requirements q Capacity of switch is the maximum rate at which it can move information, assuming all data paths are simultaneously active q Primary goal: maximize capacity m subject to cost and reliability constraints q Circuit switch must reject call if can’t find a path for samples from input to output m goal: minimize call blocking q Packet switch must reject a packet if it can’t find a buffer to store it awaiting access to output trunk m goal: minimize packet loss q Subgoal: Don’t reorder packets Lecture 5 7

Internal switching q In a circuit switch, path of a sample is determined at time of connection establishment m No need for a sample header--position in frame is enough q In a packet switch, packets carry a destination field m Need to look up destination port on-the-fly q Datagram m lookup based on entire destination address q Cell m lookup based on VCI – used as an index to a table q Other than that, switching units are very similar Lecture 5 8

Blocking in packet switches q Can have both internal and output blocking q Internal m no path to output m Example: head of line blocking. q Output m output link busy q If packet is blocked, must either buffer or drop it Lecture 5 9

Dealing with blocking q Overprovisioning m internal links much faster than inputs q Buffers m at input or output q Backpressure m if switch fabric doesn’t have buffers, prevent packet from entering until path is available q Parallel switch fabrics m increases effective switching capacity Lecture 5 10

Three generations of packet switches q Different trade-offs between cost and performance q Represent evolution in switching capacity, rather than in technology m With same technology, a later generation switch achieves greater capacity, but at greater cost q All three generations are represented in current products Lecture 5 11

First generation switch computer CPU queues in memory linecard q Most Ethernet switches and cheap packet routers q Bottleneck can be CPU, host-adaptor or I/O bus, depending Lecture 5 12

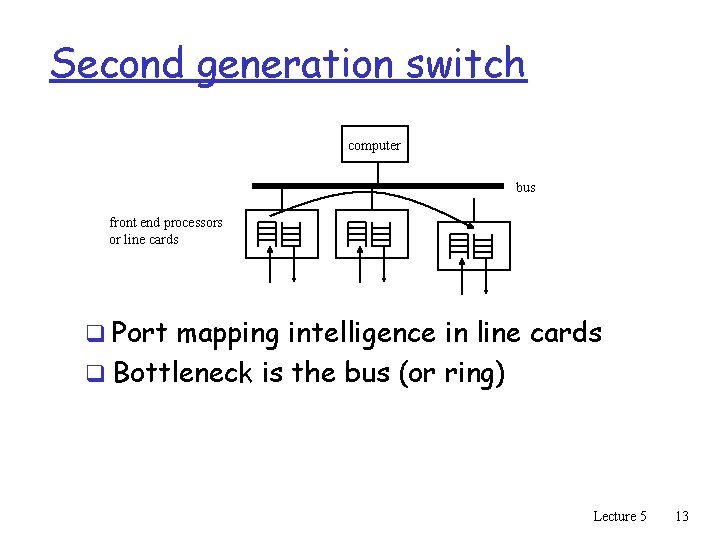

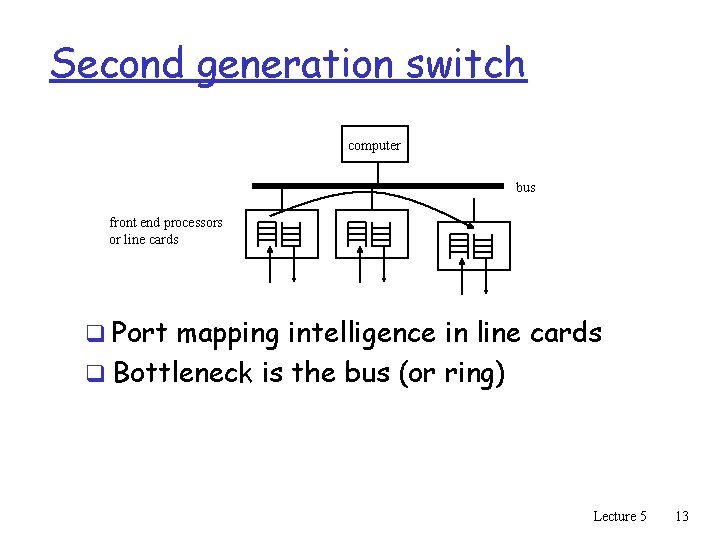

Second generation switch computer bus front end processors or line cards q Port mapping intelligence in line cards q Bottleneck is the bus (or ring) Lecture 5 13

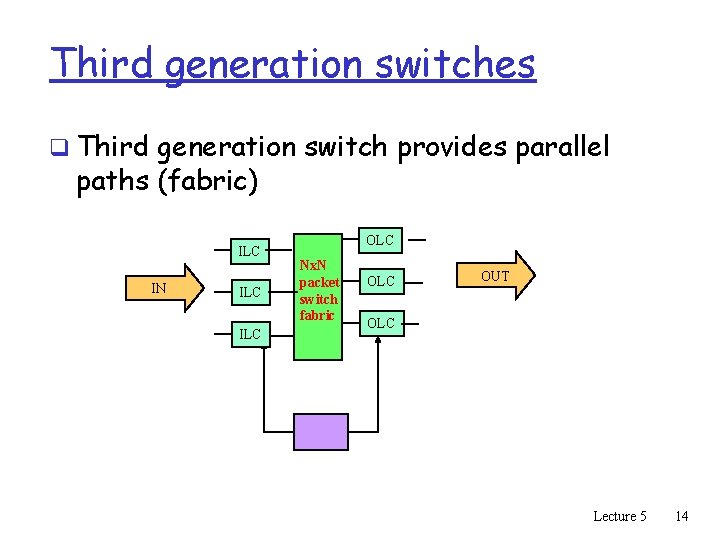

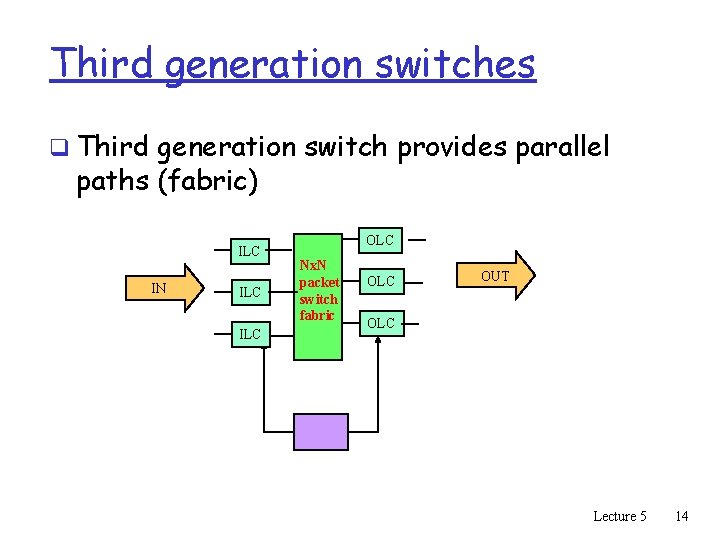

Third generation switches q Third generation switch provides parallel paths (fabric) ILC IN ILC OLC Nx. N packet switch fabric OLC OUT OLC Lecture 5 14

Third generation (contd. ) q Features m self-routing fabric m output buffer is a point of contention • unless we arbitrate access to fabric m potential for unlimited scaling, • as long as we can resolve contention for output buffer Lecture 5 15

Switching - Fabric Lecture 5 16

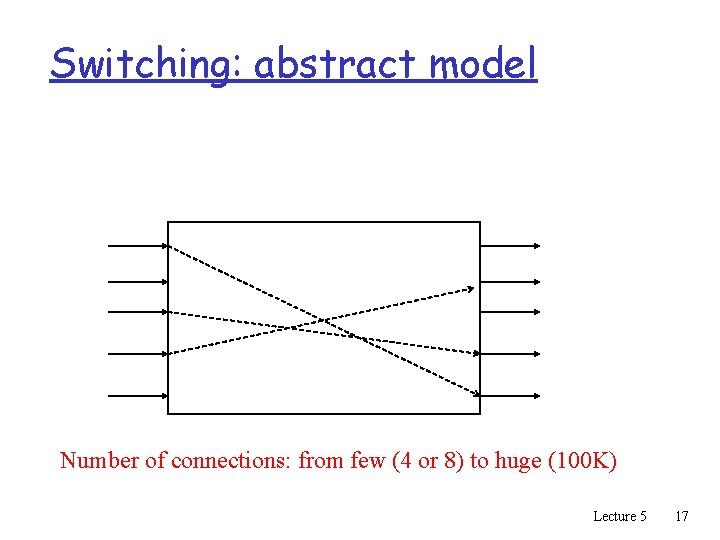

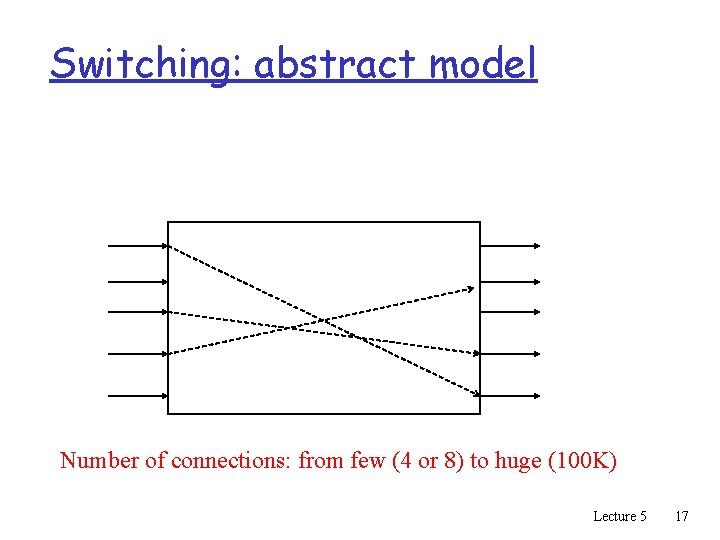

Switching: abstract model Number of connections: from few (4 or 8) to huge (100 K) Lecture 5 17

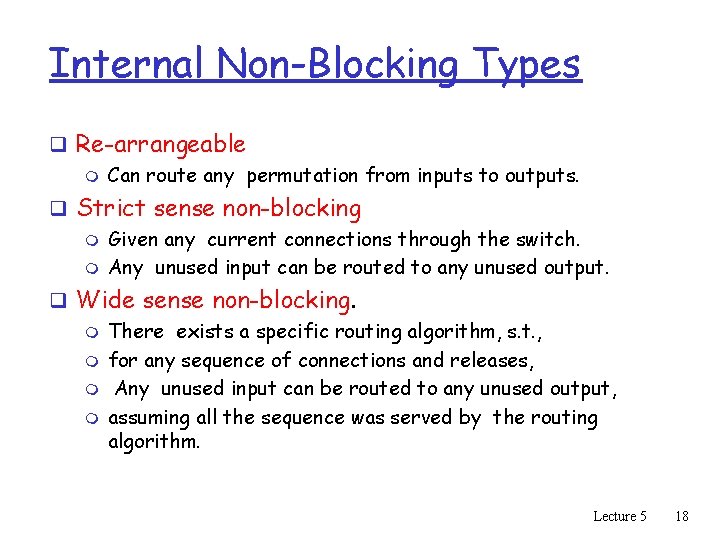

Internal Non-Blocking Types q Re-arrangeable m Can route any permutation from inputs to outputs. q Strict sense non-blocking m Given any current connections through the switch. m Any unused input can be routed to any unused output. q Wide sense non-blocking. m There exists a specific routing algorithm, s. t. , m for any sequence of connections and releases, m Any unused input can be routed to any unused output, m assuming all the sequence was served by the routing algorithm. Lecture 5 18

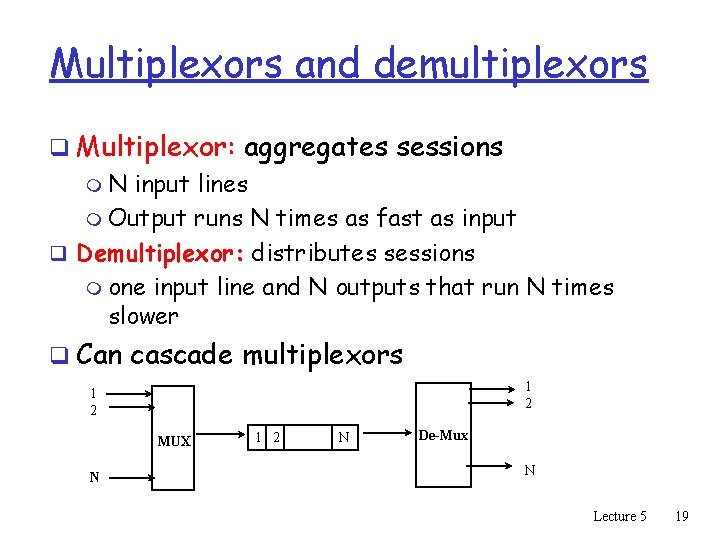

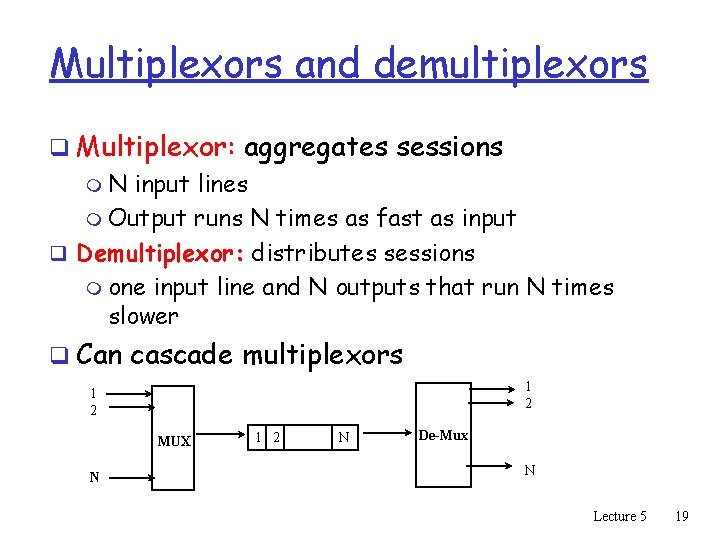

Multiplexors and demultiplexors q Multiplexor: aggregates sessions m N input lines m Output runs N times as fast as input q Demultiplexor: distributes sessions m one input line and N outputs that run N times slower q Can cascade multiplexors 1 2 MUX N 1 2 N De-Mux N Lecture 5 19

Time division switching q Key idea: when demultiplexing, position in frame determines output link q Time division switching interchanges sample position within a frame: m Time M U X slot interchange (TSI) TSI D E M U X Lecture 5 20

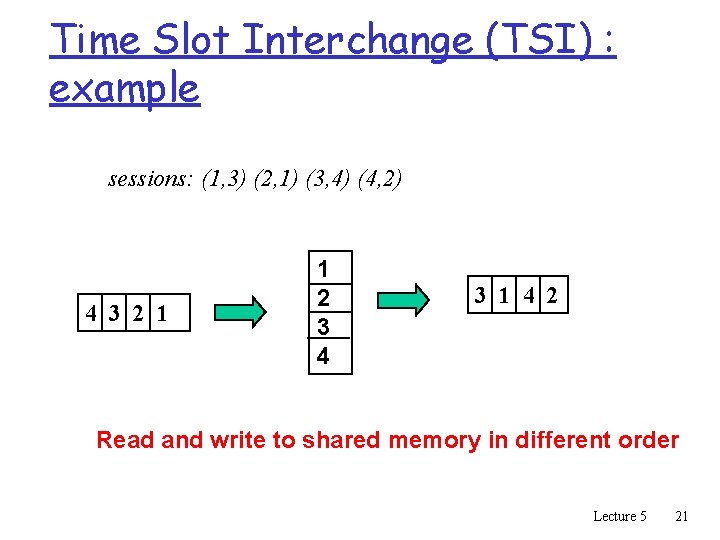

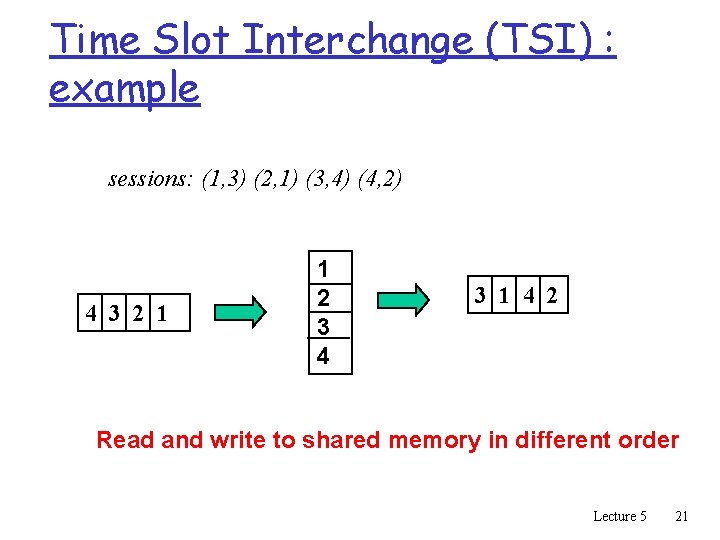

Time Slot Interchange (TSI) : example sessions: (1, 3) (2, 1) (3, 4) (4, 2) 4 3 2 1 1 2 3 4 3 1 4 2 Read and write to shared memory in different order Lecture 5 21

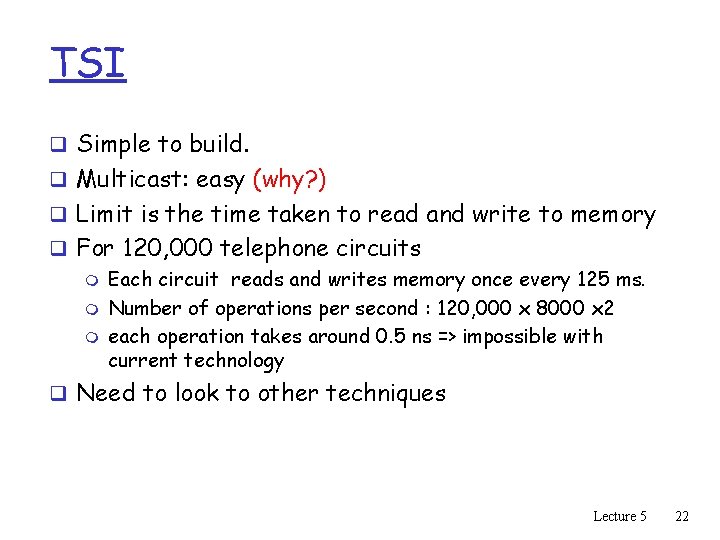

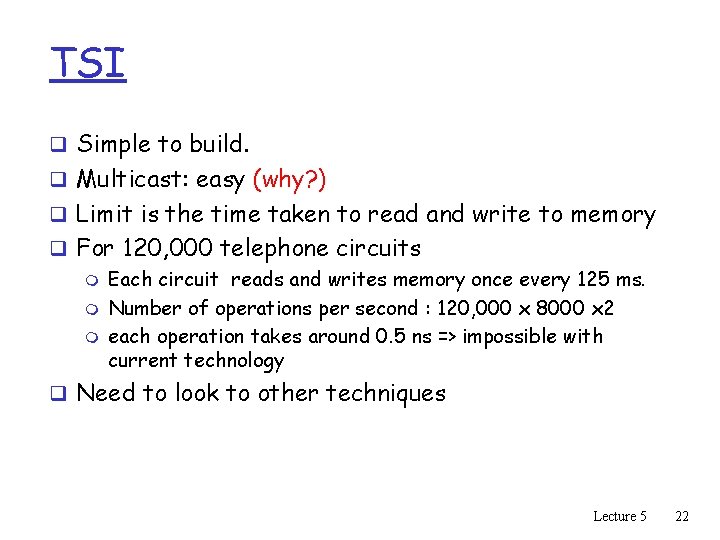

TSI q Simple to build. q Multicast: easy (why? ) q Limit is the time taken to read and write to memory q For 120, 000 telephone circuits m Each circuit reads and writes memory once every 125 ms. m Number of operations per second : 120, 000 x 8000 x 2 m each operation takes around 0. 5 ns => impossible with current technology q Need to look to other techniques Lecture 5 22

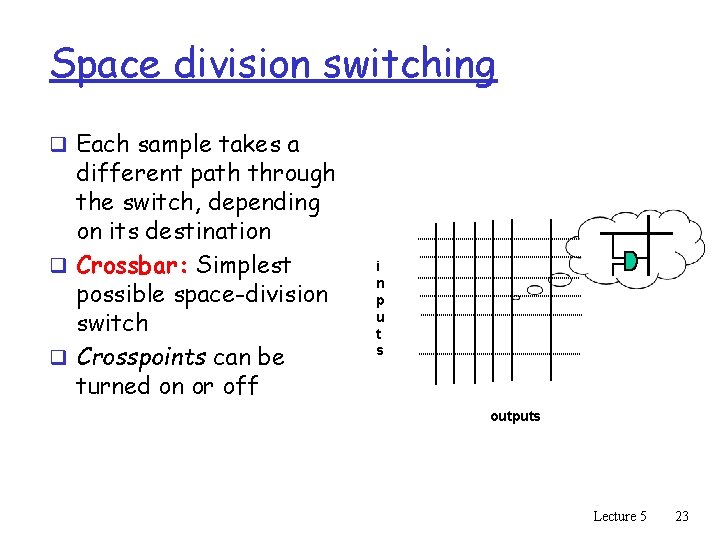

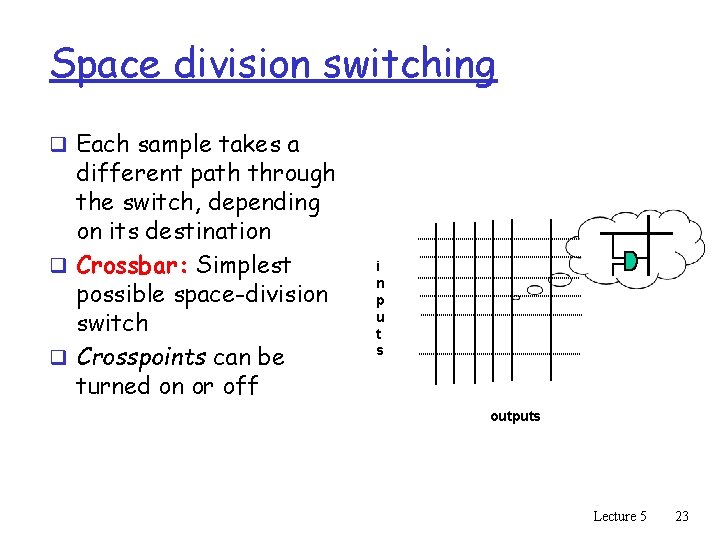

Space division switching q Each sample takes a different path through the switch, depending on its destination q Crossbar: Simplest possible space-division switch q Crosspoints can be turned on or off i n p u t s outputs Lecture 5 23

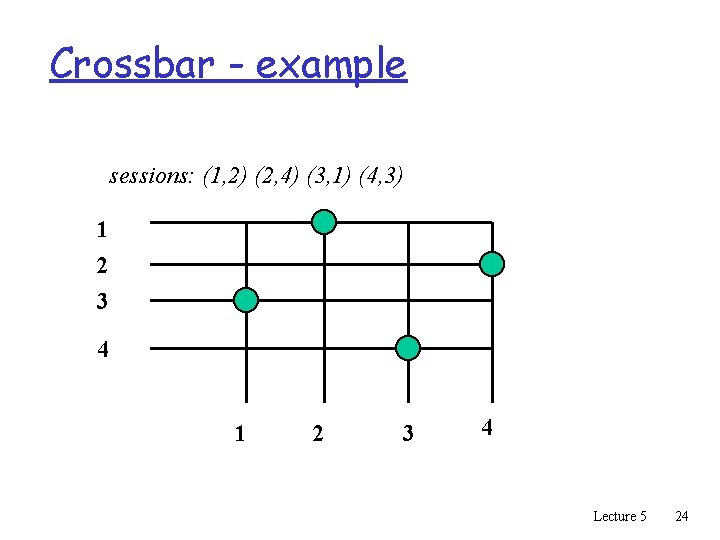

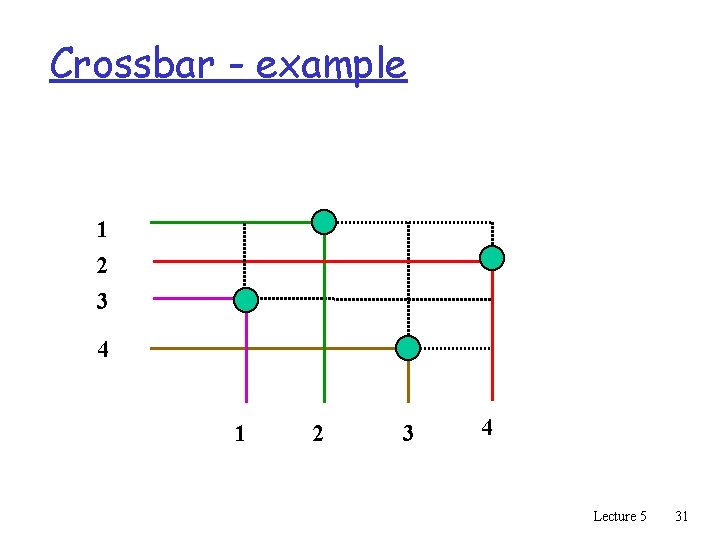

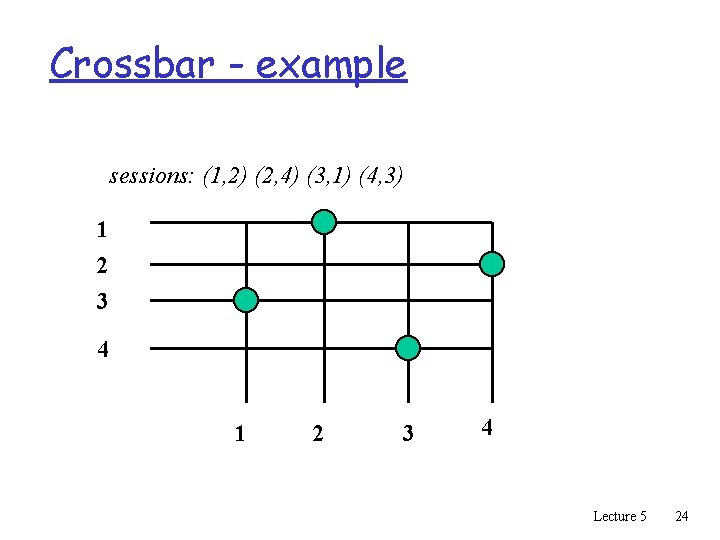

Crossbar - example sessions: (1, 2) (2, 4) (3, 1) (4, 3) 1 2 3 4 Lecture 5 24

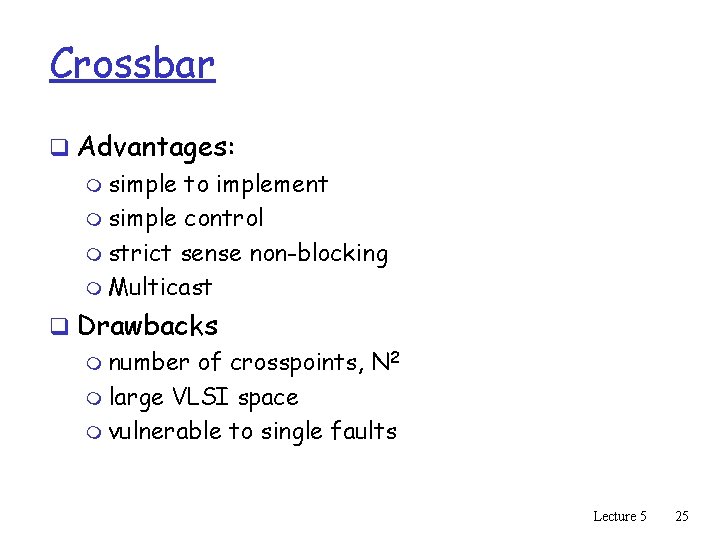

Crossbar q Advantages: m simple to implement m simple control m strict sense non-blocking m Multicast q Drawbacks m number of crosspoints, N 2 m large VLSI space m vulnerable to single faults Lecture 5 25

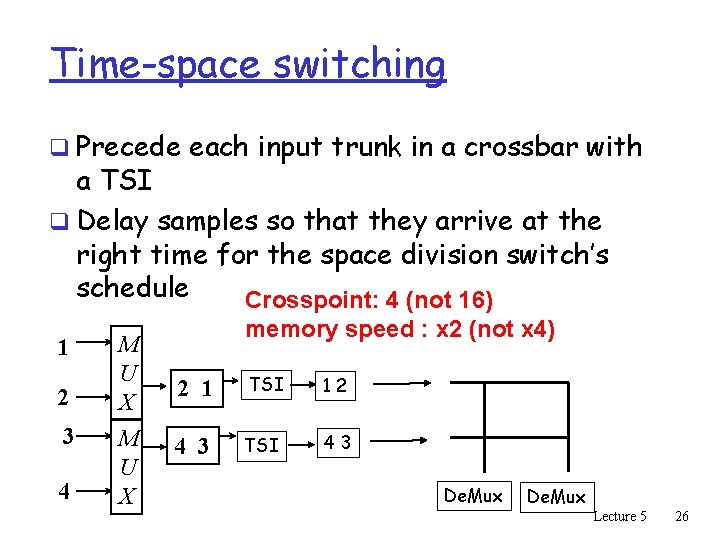

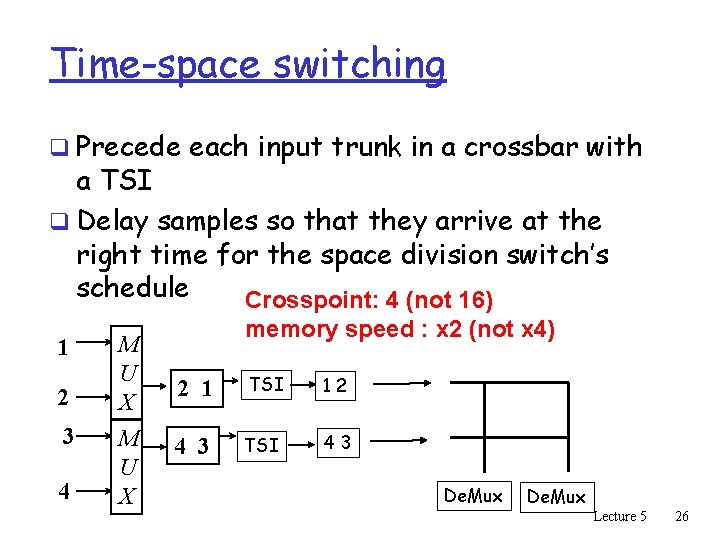

Time-space switching q Precede each input trunk in a crossbar with a TSI q Delay samples so that they arrive at the right time for the space division switch’s schedule Crosspoint: 4 (not 16) 1 2 3 4 M U X memory speed : x 2 (not x 4) 2 1 TSI 12 4 3 TSI 43 De. Mux Lecture 5 26

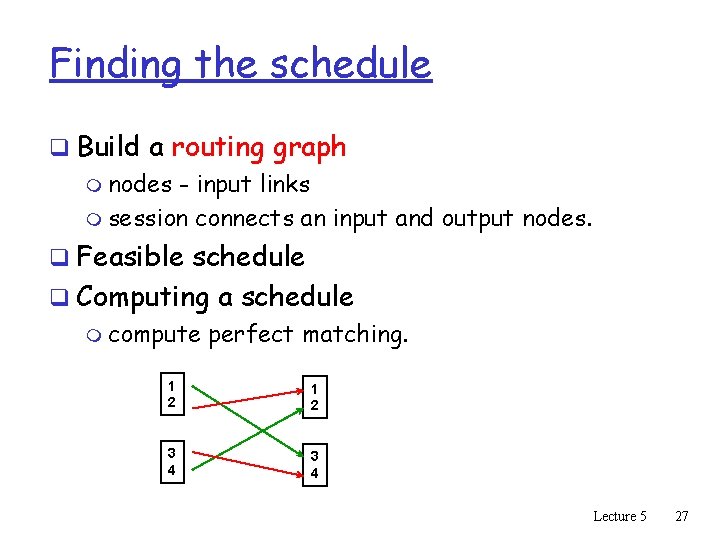

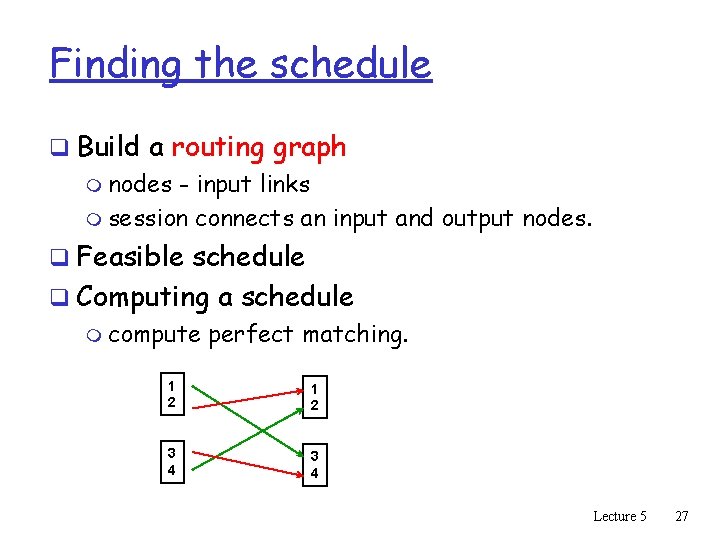

Finding the schedule q Build a routing graph m nodes - input links m session connects an input and output nodes. q Feasible schedule q Computing a schedule m compute perfect matching. 1 2 3 4 Lecture 5 27

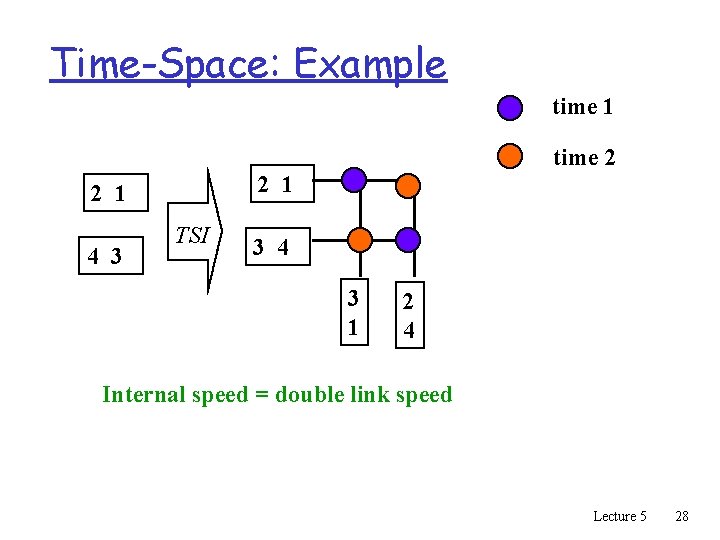

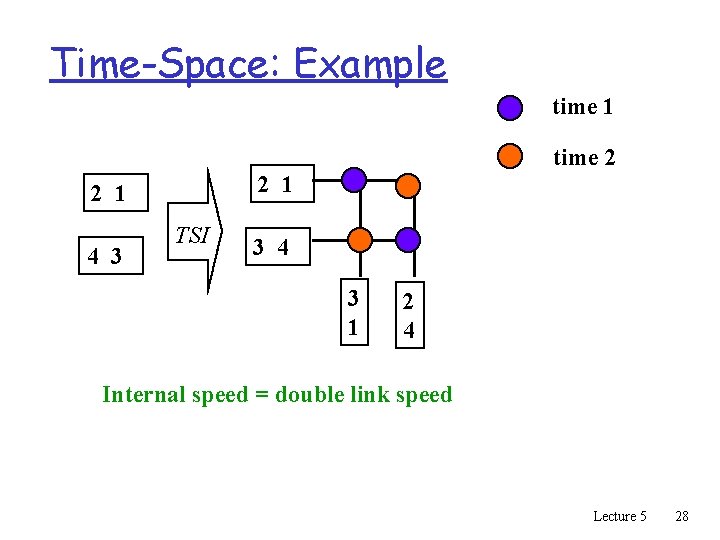

Time-Space: Example time 1 time 2 2 1 4 3 TSI 3 4 3 1 2 4 Internal speed = double link speed Lecture 5 28

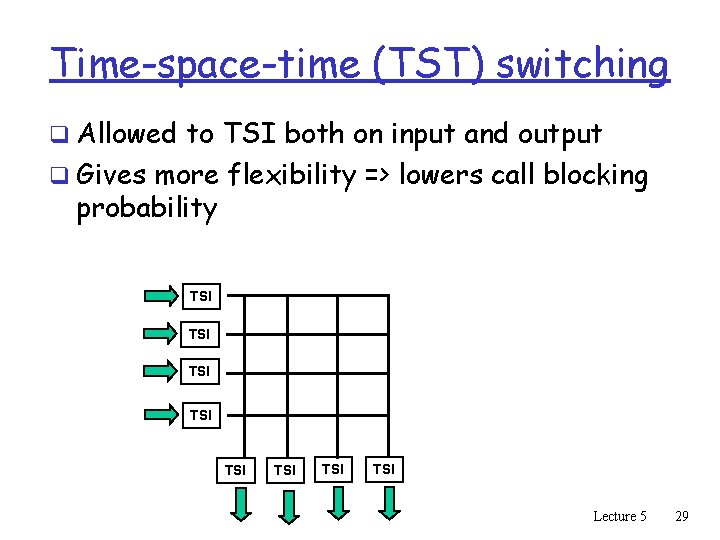

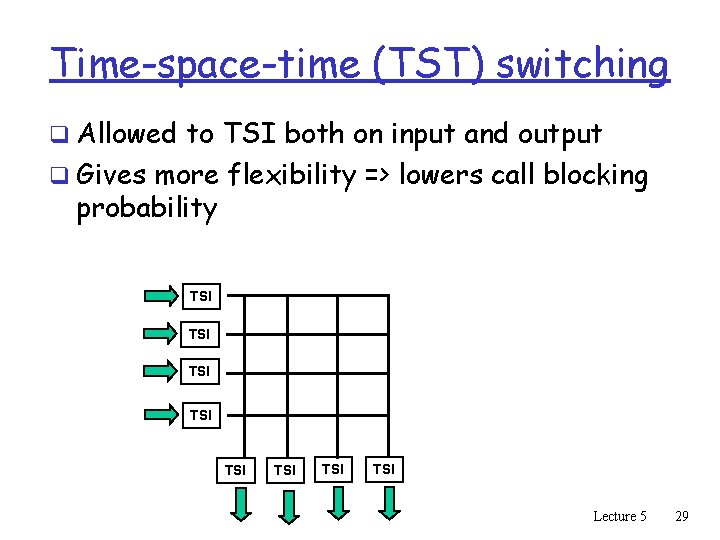

Time-space-time (TST) switching q Allowed to TSI both on input and output q Gives more flexibility => lowers call blocking probability TSI TSI Lecture 5 29

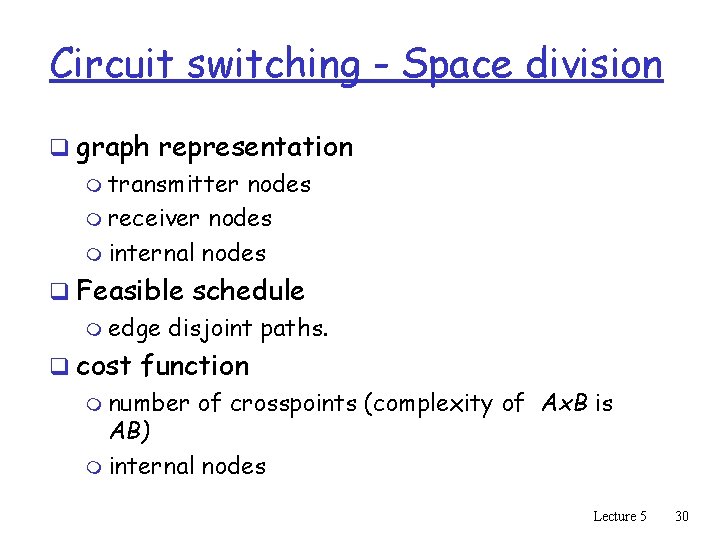

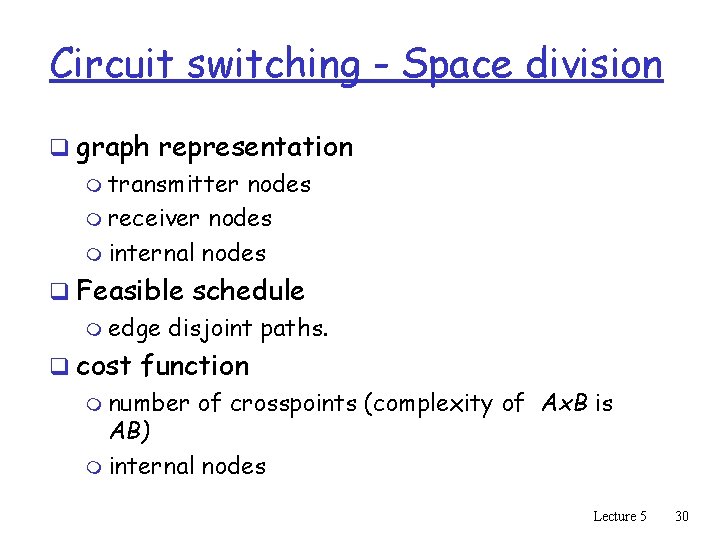

Circuit switching - Space division q graph representation m transmitter nodes m receiver nodes m internal nodes q Feasible schedule m edge disjoint paths. q cost function m number of crosspoints (complexity of Ax. B is AB) m internal nodes Lecture 5 30

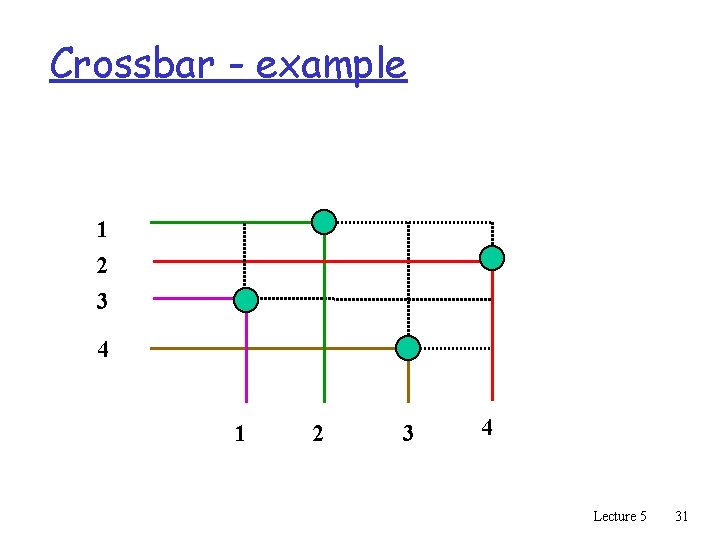

Crossbar - example 1 2 3 4 Lecture 5 31

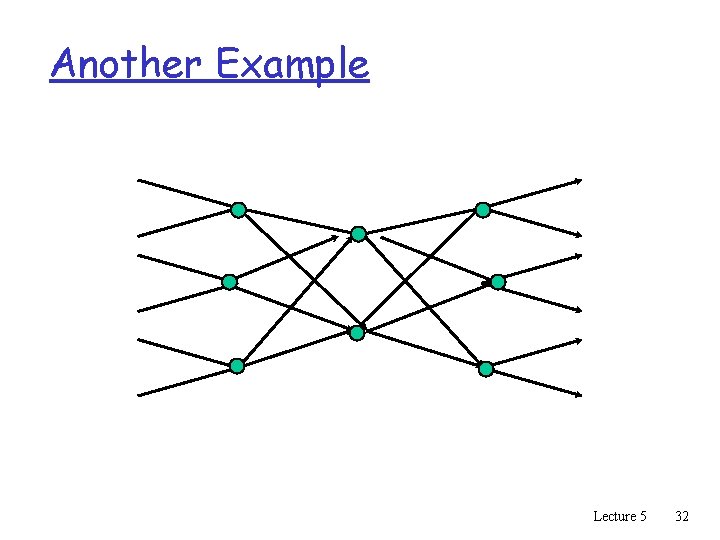

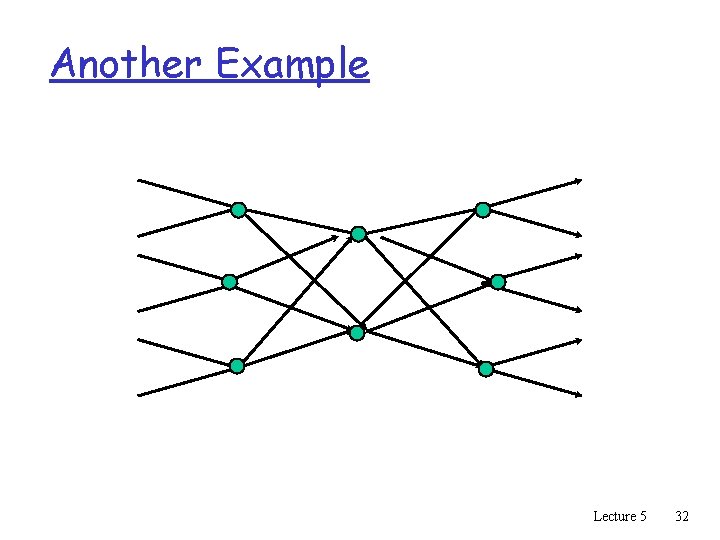

Another Example Lecture 5 32

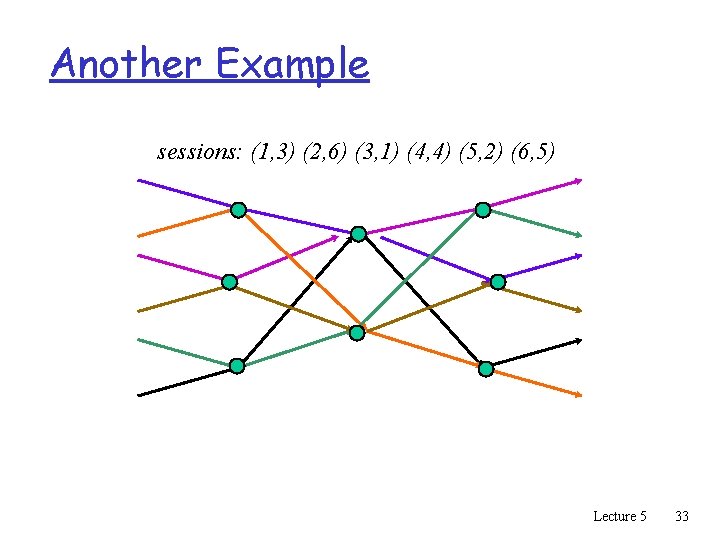

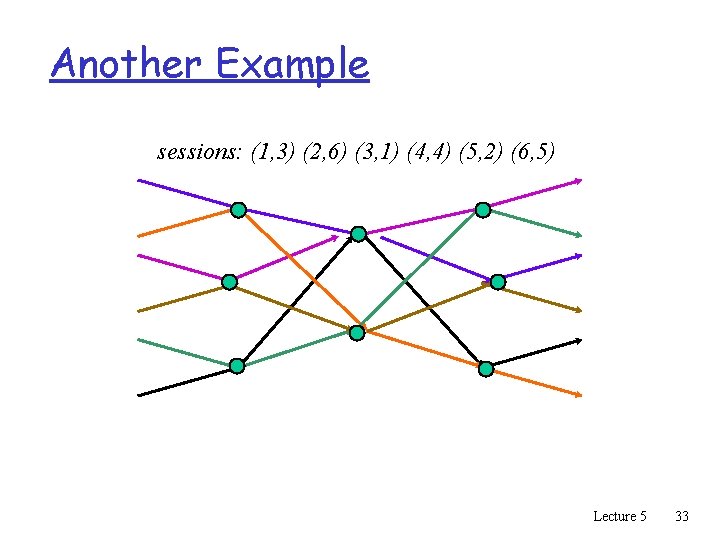

Another Example sessions: (1, 3) (2, 6) (3, 1) (4, 4) (5, 2) (6, 5) Lecture 5 33

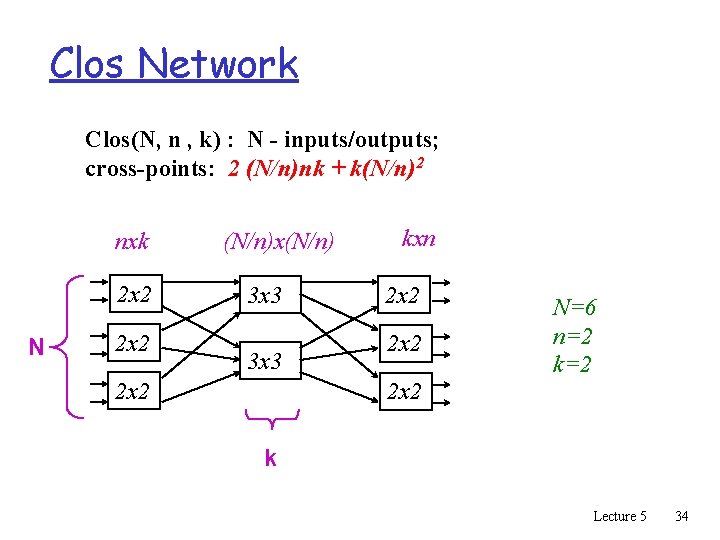

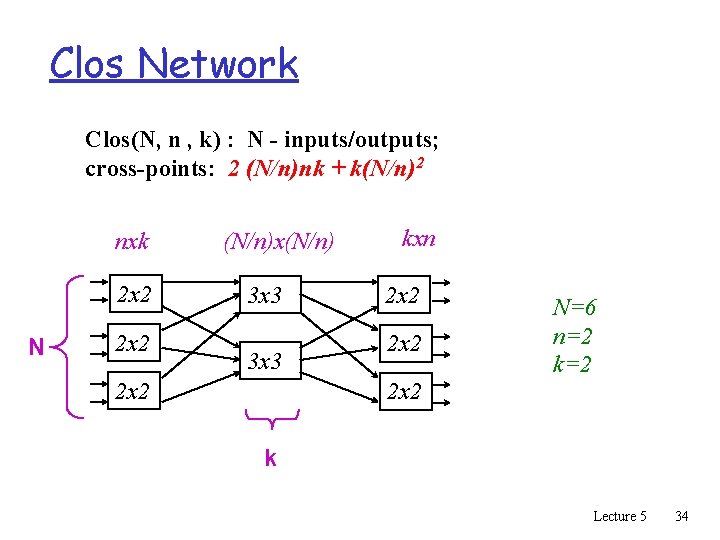

Clos Network Clos(N, n , k) : N - inputs/outputs; cross-points: 2 (N/n)nk + k(N/n)2 nxk 2 x 2 N 2 x 2 (N/n)x(N/n) 3 x 3 2 x 2 kxn 2 x 2 N=6 n=2 k=2 2 x 2 k Lecture 5 34

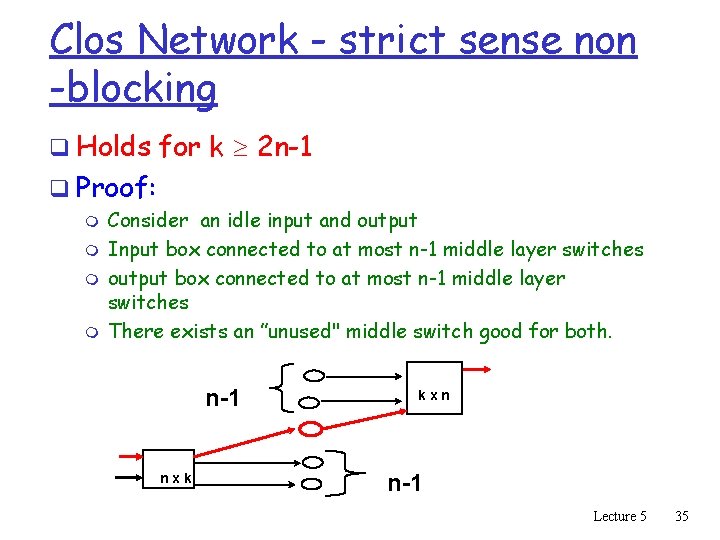

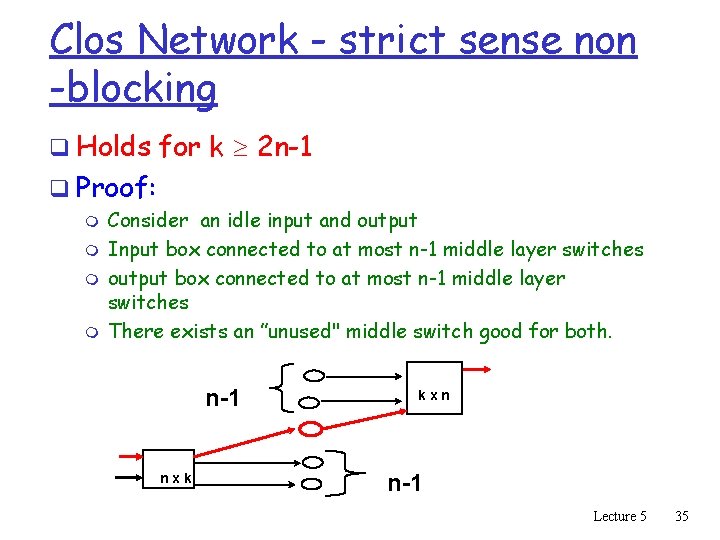

Clos Network - strict sense non -blocking q Holds for k 2 n-1 q Proof: m m Consider an idle input and output Input box connected to at most n-1 middle layer switches output box connected to at most n-1 middle layer switches There exists an ”unused" middle switch good for both. n-1 nxk kxn n-1 Lecture 5 35

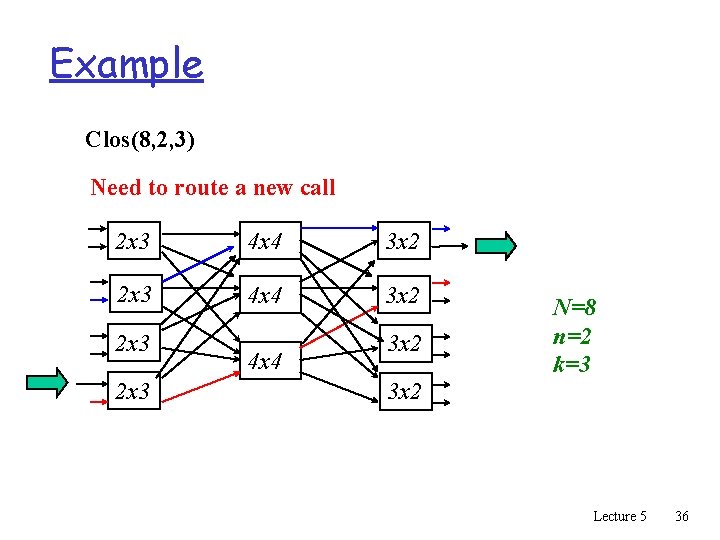

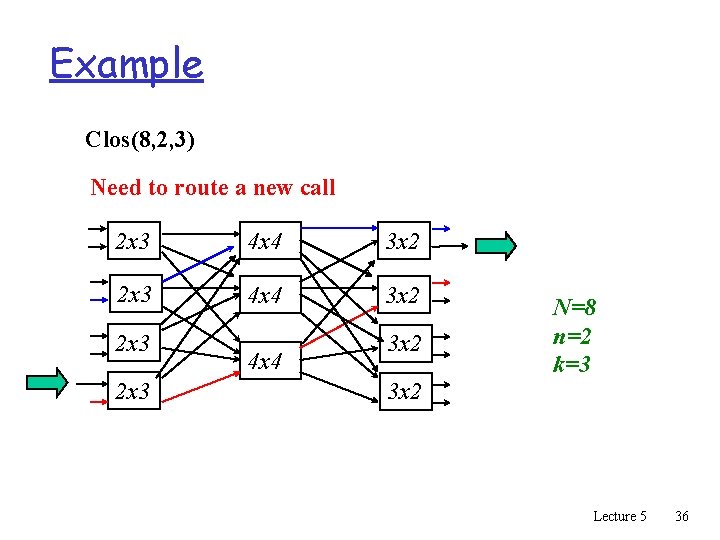

Example Clos(8, 2, 3) Need to route a new call 2 x 3 4 x 4 3 x 2 N=8 n=2 k=3 3 x 2 Lecture 5 36

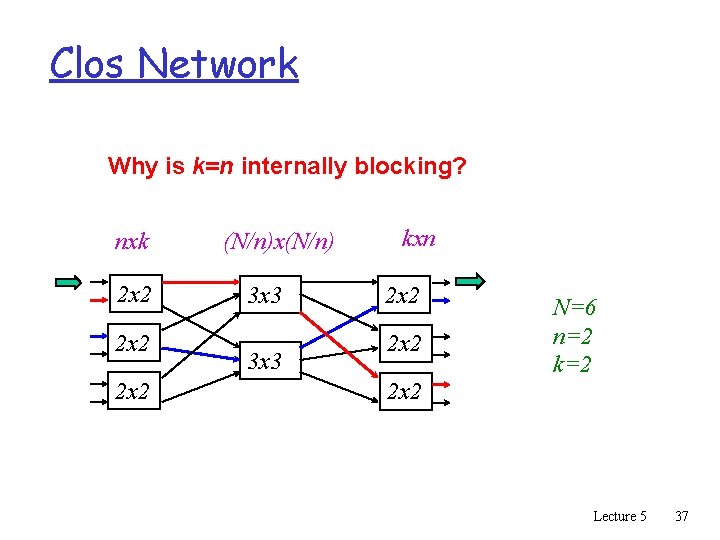

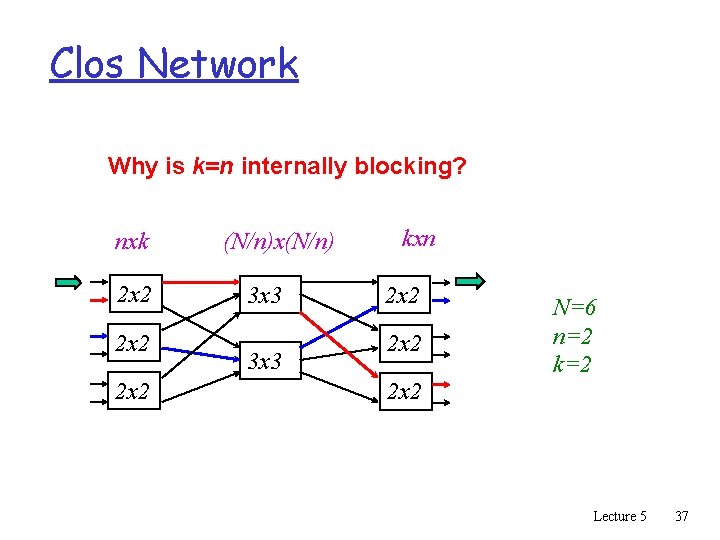

Clos Network Why is k=n internally blocking? nxk 2 x 2 (N/n)x(N/n) 3 x 3 kxn 2 x 2 N=6 n=2 k=2 2 x 2 Lecture 5 37

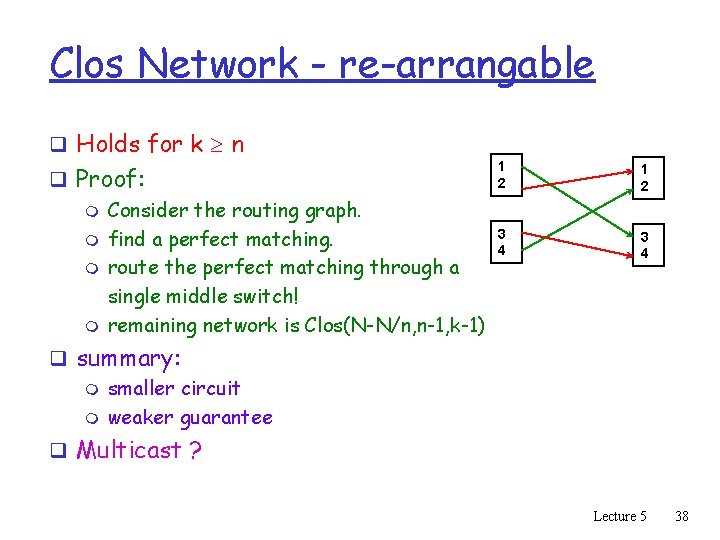

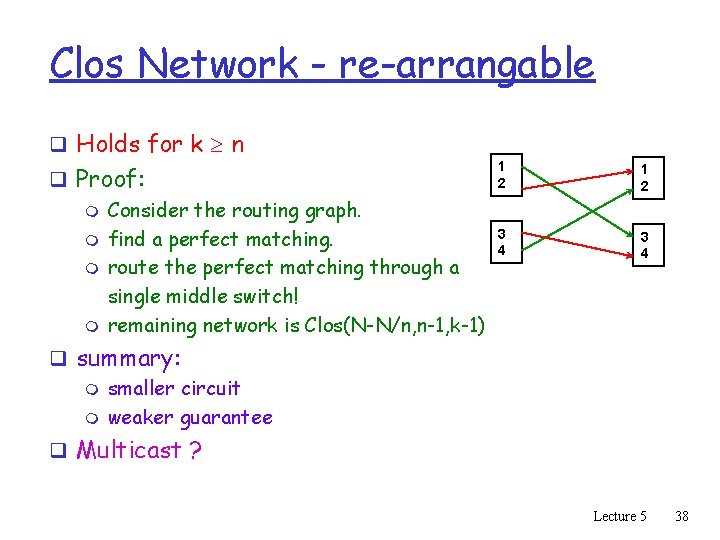

Clos Network - re-arrangable q Holds for k n q Proof: m Consider the routing graph. m find a perfect matching. m route the perfect matching through a single middle switch! m remaining network is Clos(N-N/n, n-1, k-1) 1 2 3 4 q summary: m smaller circuit m weaker guarantee q Multicast ? Lecture 5 38

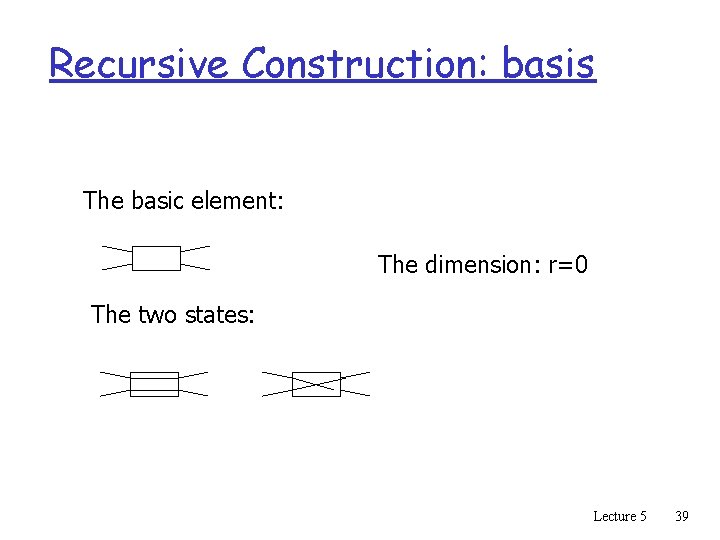

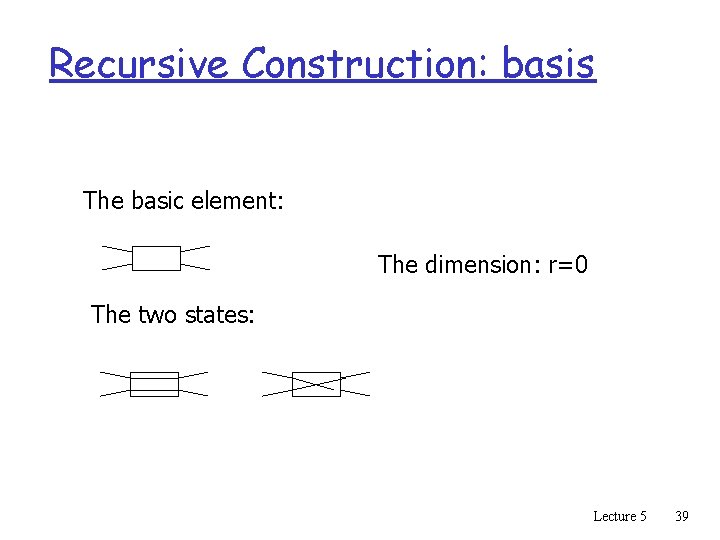

Recursive Construction: basis The basic element: The dimension: r=0 The two states: Lecture 5 39

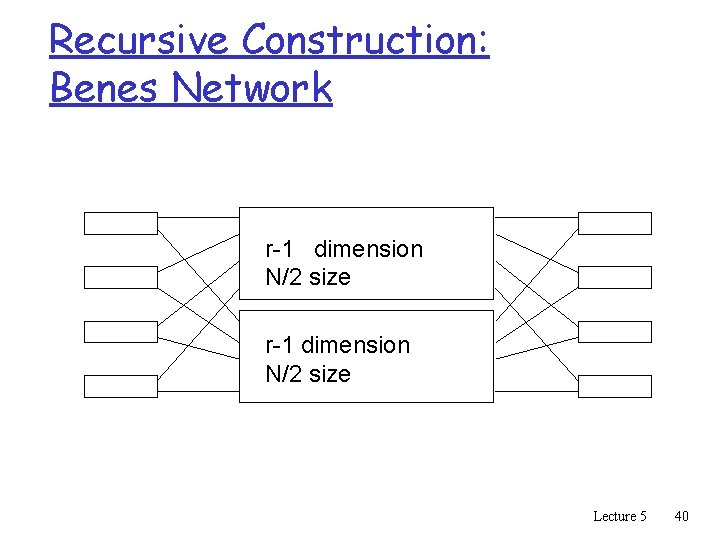

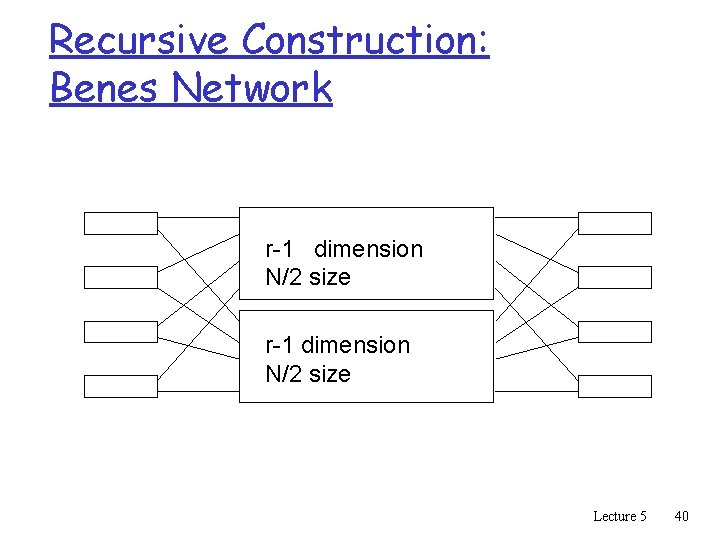

Recursive Construction: Benes Network r-1 dimension N/2 size Lecture 5 40

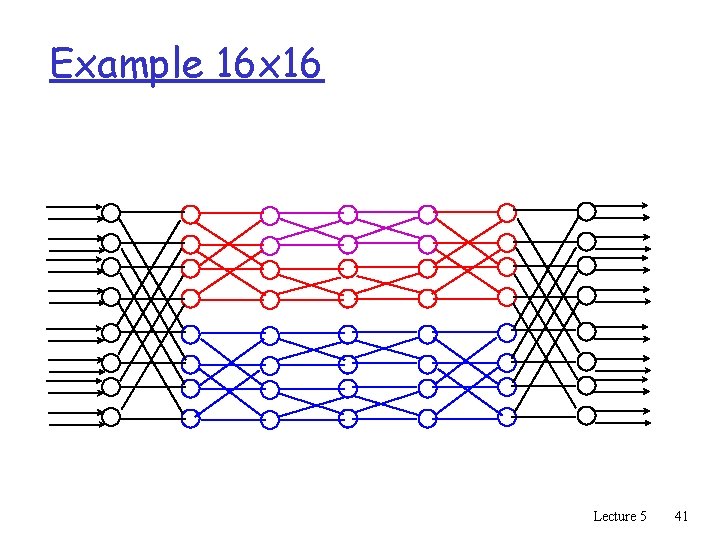

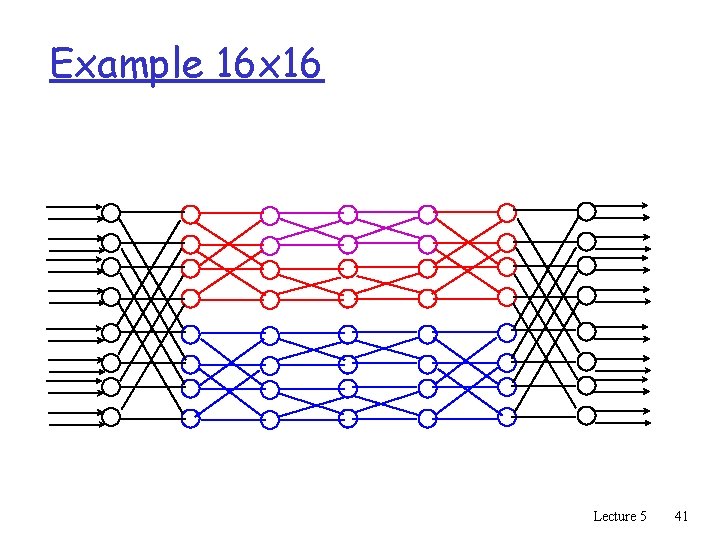

Example 16 x 16 Lecture 5 41

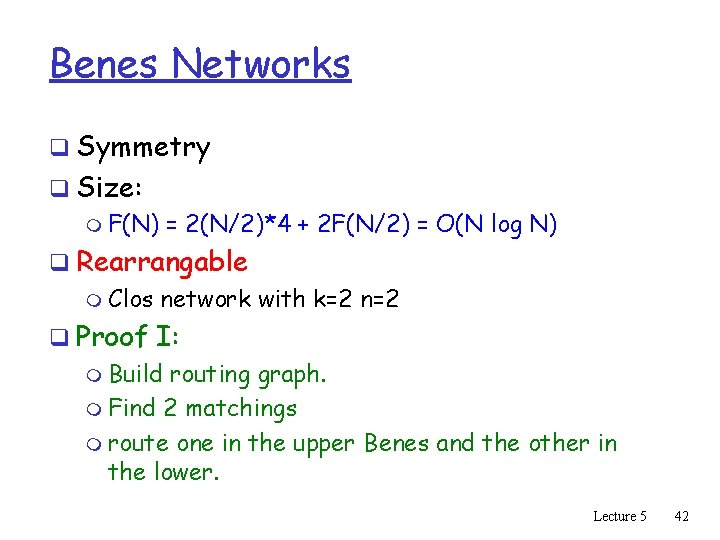

Benes Networks q Symmetry q Size: m F(N) = 2(N/2)*4 + 2 F(N/2) = O(N log N) q Rearrangable m Clos network with k=2 n=2 q Proof I: m Build routing graph. m Find 2 matchings m route one in the upper Benes and the other in the lower. Lecture 5 42

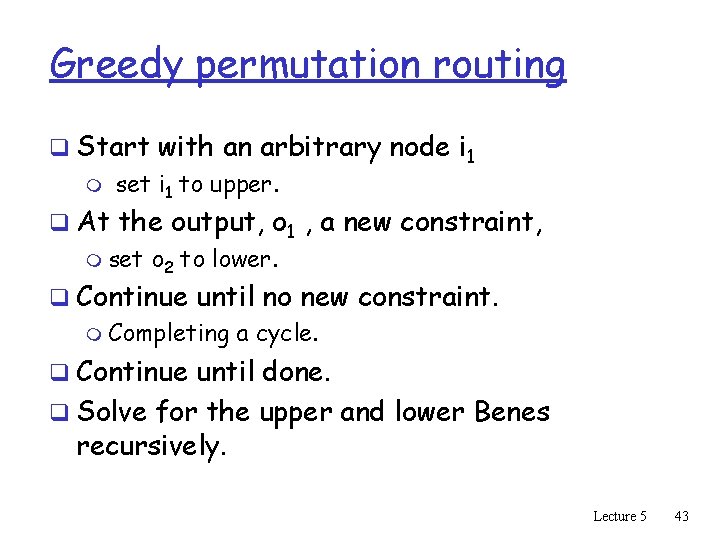

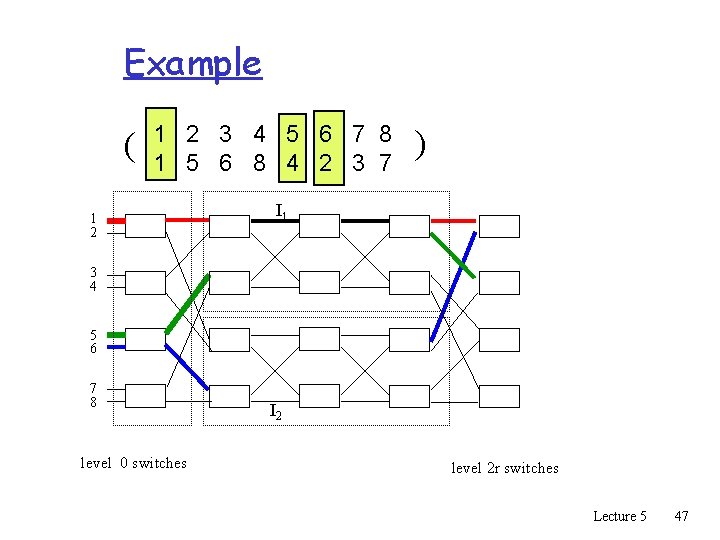

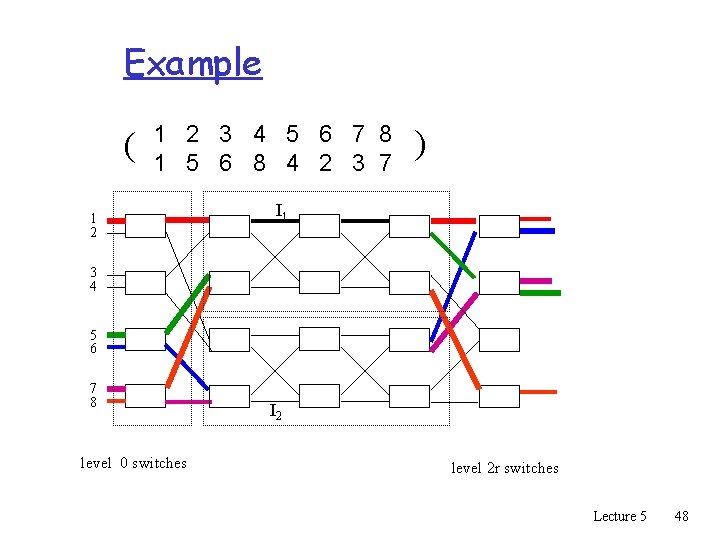

Greedy permutation routing q Start with an arbitrary node i 1 m set i 1 to upper. q At the output, o 1 , a new constraint, m set o 2 to lower. q Continue until no new constraint. m Completing a cycle. q Continue until done. q Solve for the upper and lower Benes recursively. Lecture 5 43

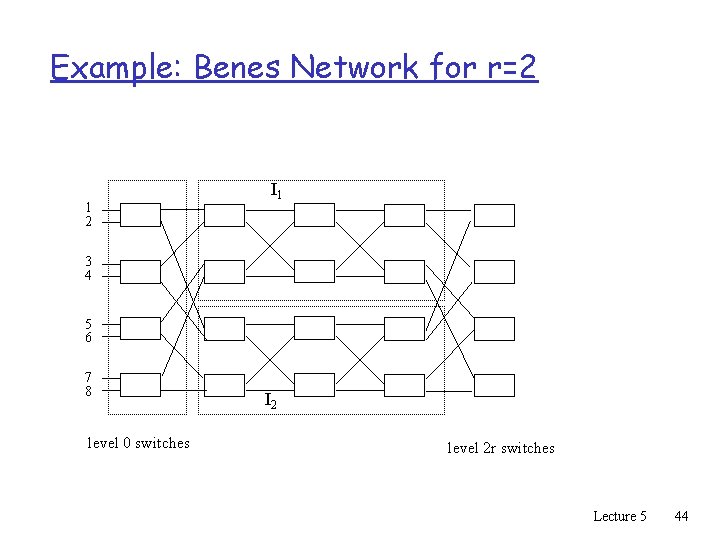

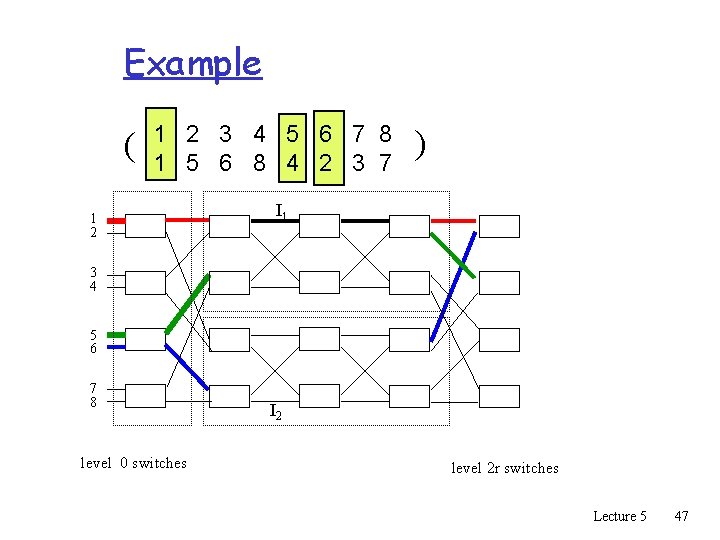

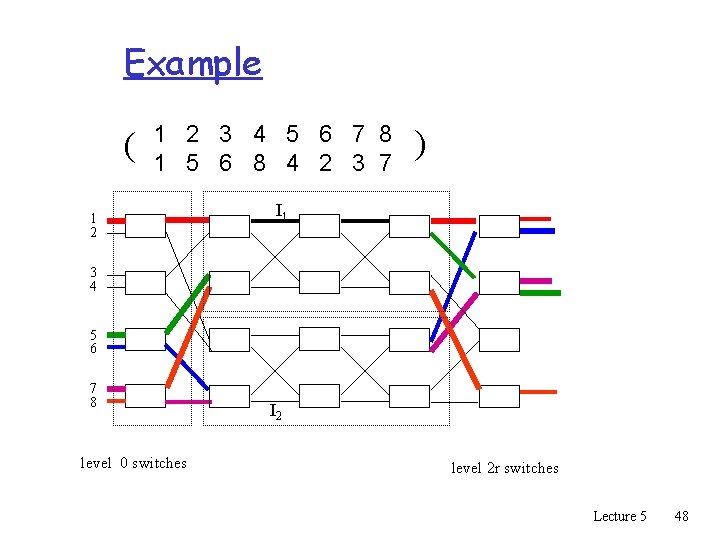

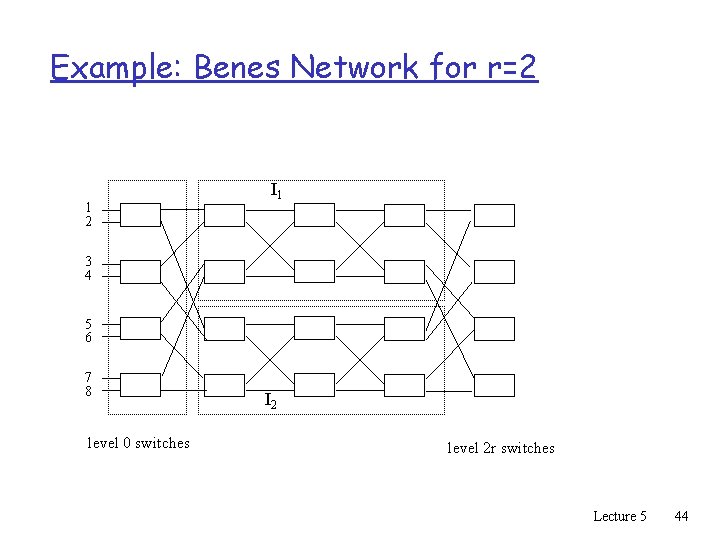

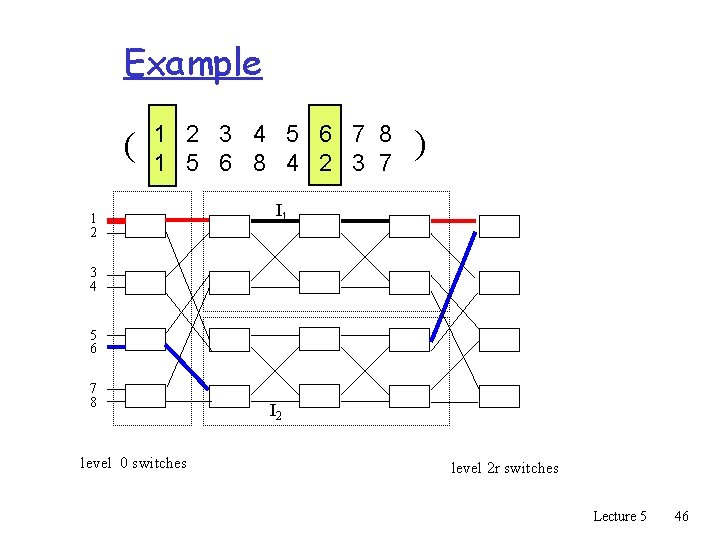

Example: Benes Network for r=2 1 2 I 1 3 4 5 6 7 8 level 0 switches I 2 level 2 r switches Lecture 5 44

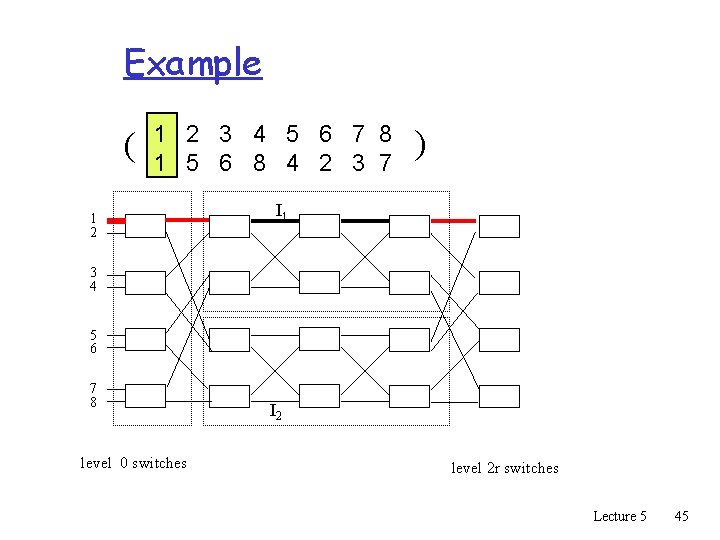

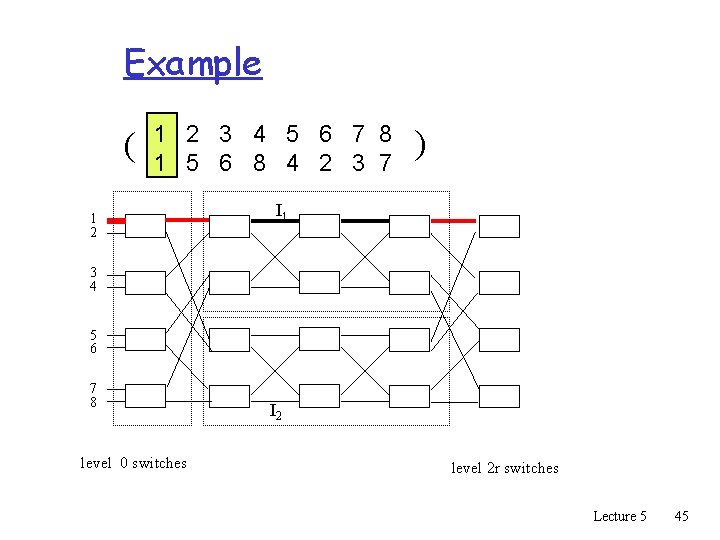

Example ( 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 1 5 6 8 4 2 3 7 1 2 ) I 1 3 4 5 6 7 8 level 0 switches I 2 level 2 r switches Lecture 5 45

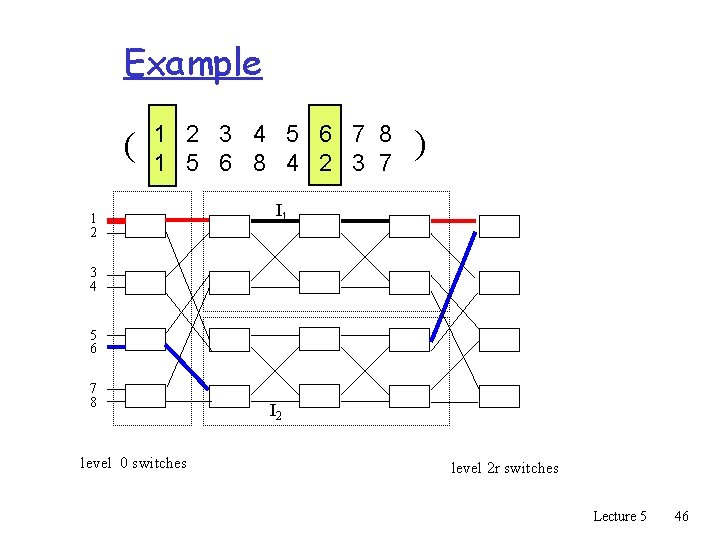

Example ( 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 1 5 6 8 4 2 3 7 1 2 ) I 1 3 4 5 6 7 8 level 0 switches I 2 level 2 r switches Lecture 5 46

Example ( 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 1 5 6 8 4 2 3 7 1 2 ) I 1 3 4 5 6 7 8 level 0 switches I 2 level 2 r switches Lecture 5 47

Example ( 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 1 5 6 8 4 2 3 7 1 2 ) I 1 3 4 5 6 7 8 level 0 switches I 2 level 2 r switches Lecture 5 48

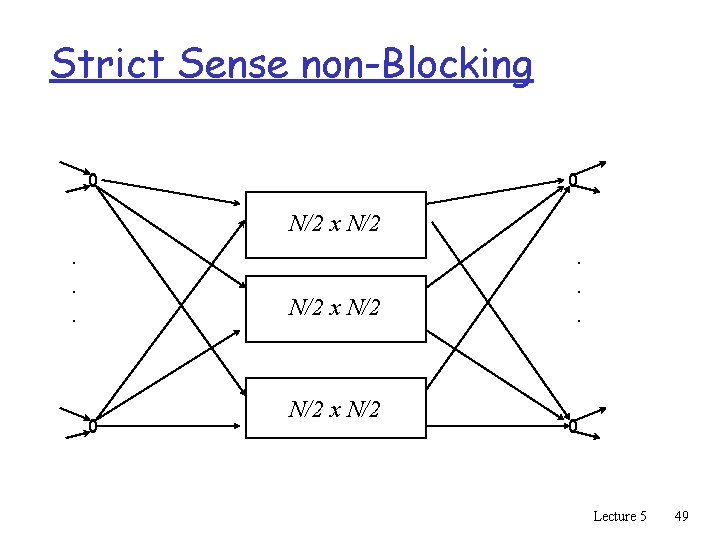

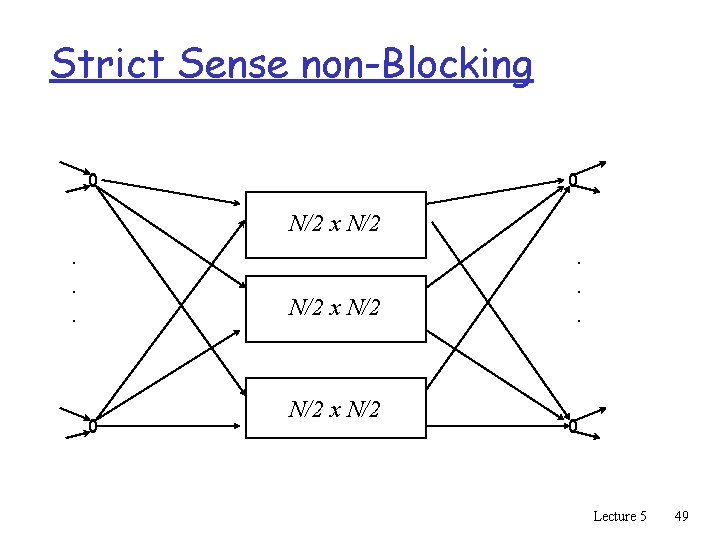

Strict Sense non-Blocking N/2 x N/2. . . N/2 x N/2 Lecture 5 49

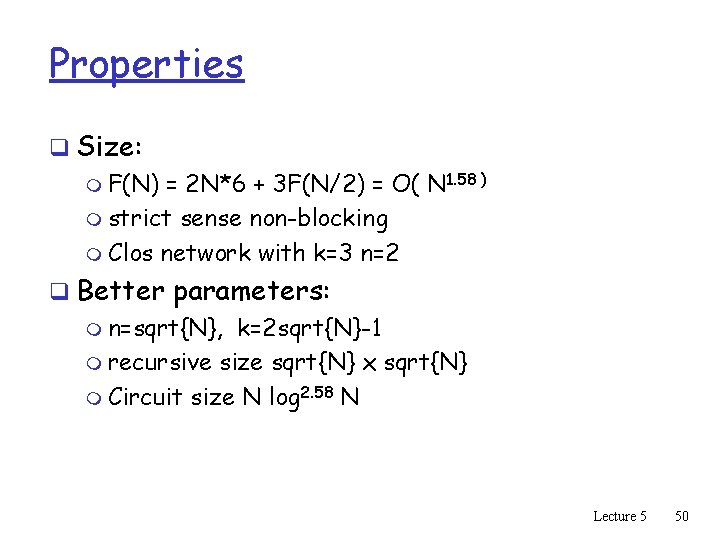

Properties q Size: m F(N) = 2 N*6 + 3 F(N/2) = O( N 1. 58 ) m strict sense non-blocking m Clos network with k=3 n=2 q Better parameters: m n=sqrt{N}, k=2 sqrt{N}-1 m recursive size sqrt{N} x sqrt{N} m Circuit size N log 2. 58 N Lecture 5 50

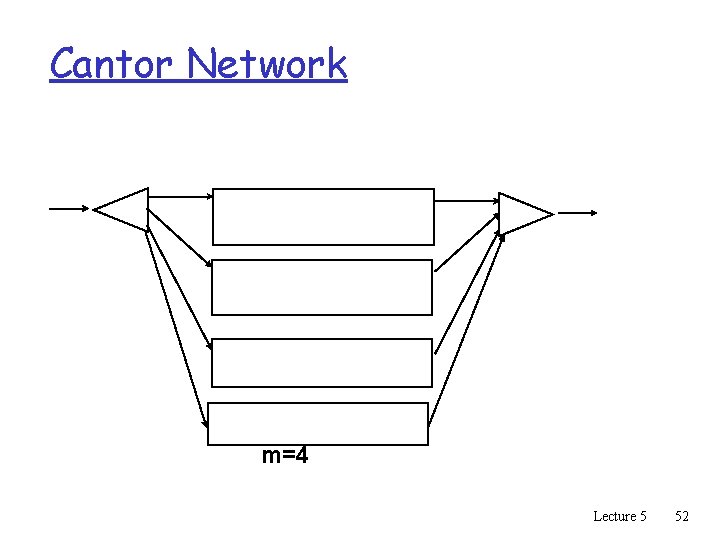

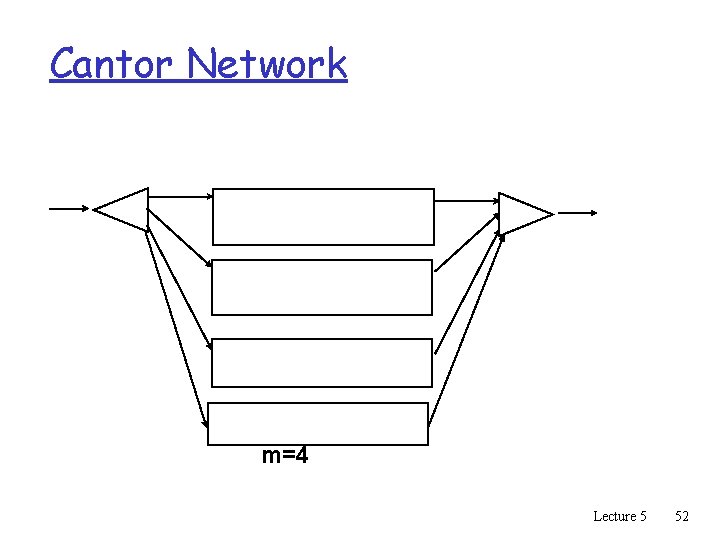

Cantor Networks q m copies of Benes network. q For m = log N its strict sense non-blocking q Network size N log 2 N q Example Lecture 5 51

Cantor Network m=4 Lecture 5 52

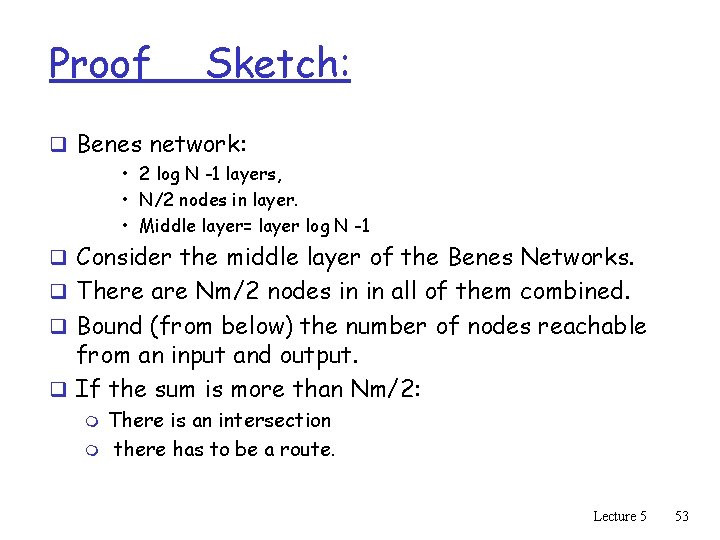

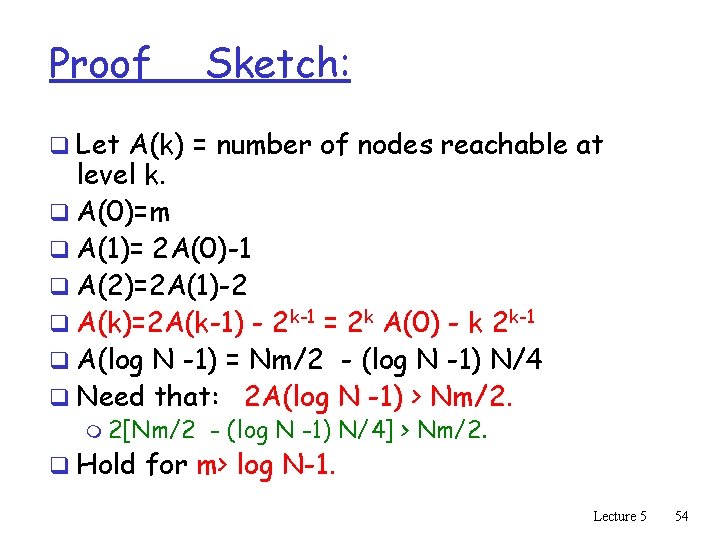

Proof Sketch: q Benes network: • 2 log N -1 layers, • N/2 nodes in layer. • Middle layer= layer log N -1 q Consider the middle layer of the Benes Networks. q There are Nm/2 nodes in in all of them combined. q Bound (from below) the number of nodes reachable from an input and output. q If the sum is more than Nm/2: m m There is an intersection there has to be a route. Lecture 5 53

Proof Sketch: q Let A(k) = number of nodes reachable at level k. q A(0)=m q A(1)= 2 A(0)-1 q A(2)=2 A(1)-2 q A(k)=2 A(k-1) - 2 k-1 = 2 k A(0) - k 2 k-1 q A(log N -1) = Nm/2 - (log N -1) N/4 q Need that: 2 A(log N -1) > Nm/2. m 2[Nm/2 - (log N -1) N/4] > Nm/2. q Hold for m> log N-1. Lecture 5 54

Advanced constructions q There are networks of size O(N log N). m the constants are huge! q Basic paradigm also applies to large packet switches. Lecture 5 56