Summarizing How does a summary differ from a

- Slides: 13

Summarizing • How does a summary differ from a paraphrase and quotation? – How do you identify the main points? – How do you change the author’s words into your own? – How do you change the author’s sentence structure into your own?

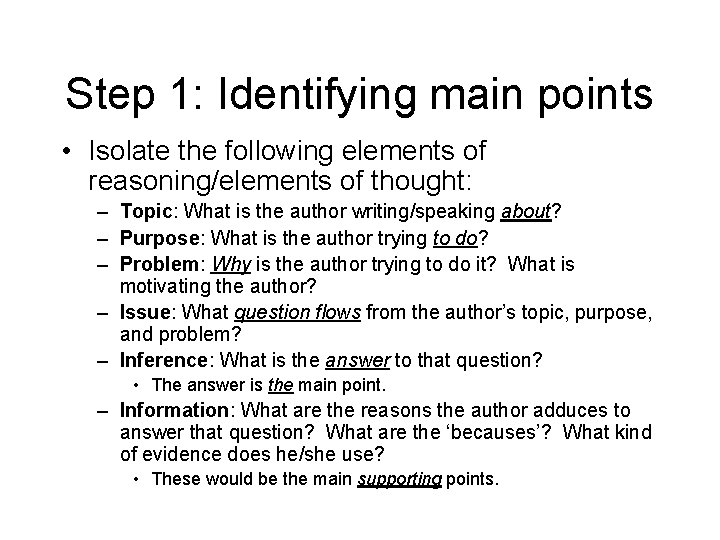

Step 1: Identifying main points • Isolate the following elements of reasoning/elements of thought: – Topic: What is the author writing/speaking about? – Purpose: What is the author trying to do? – Problem: Why is the author trying to do it? What is motivating the author? – Issue: What question flows from the author’s topic, purpose, and problem? – Inference: What is the answer to that question? • The answer is the main point. – Information: What are the reasons the author adduces to answer that question? What are the ‘becauses’? What kind of evidence does he/she use? • These would be the main supporting points.

Step 1: Identifying main points • Try this technique on a text with which we should all be familiar, President Ezra Taft Benson’s April ‘ 89 conference talk, “Beware of Pride”: – Topic: What is the author writing/speaking about? – Purpose: What is the author trying to do? – Problem: Why is the author trying to do it? What is motivating the author? – Issue: What question(s) flow(s) from the author’s topic, purpose, and problem? – Inference: What is/are the answer(s) to that/those question(s)? • The answer(s) is/are the main point(s). – Information: What are the reasons the author adduces to answer that/those question(s)? What are the ‘becauses’? What kind of evidence does he/she use? • These would be the main supporting points.

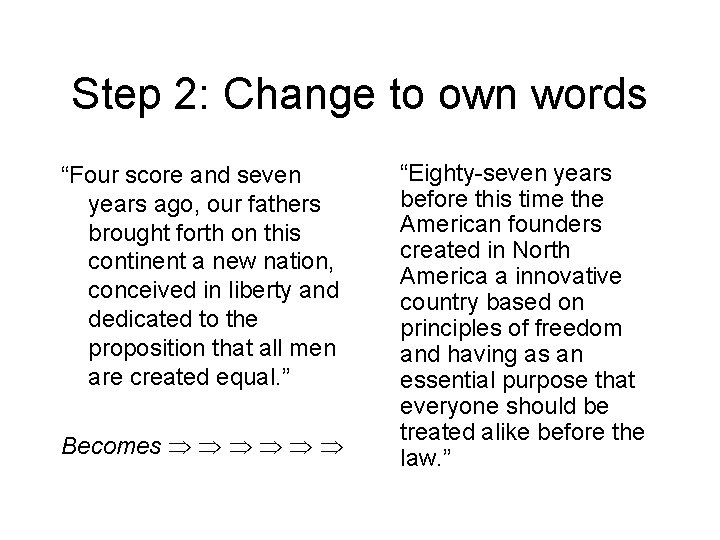

Steps 2 & 3: Change the main ideas into your own words and sentence structure Original quotation: “Four score and seven years ago, our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal. ”

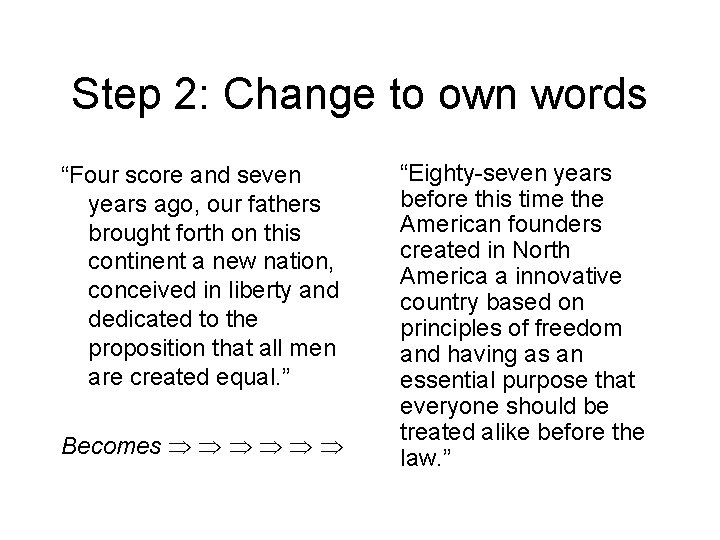

Step 2: Change to own words “Four score and seven years ago, our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal. ” Becomes “Eighty-seven years before this time the American founders created in North America a innovative country based on principles of freedom and having as an essential purpose that everyone should be treated alike before the law. ”

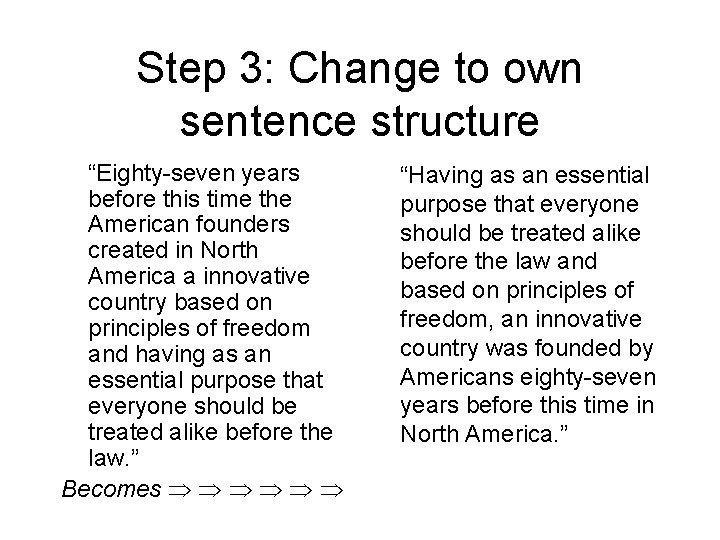

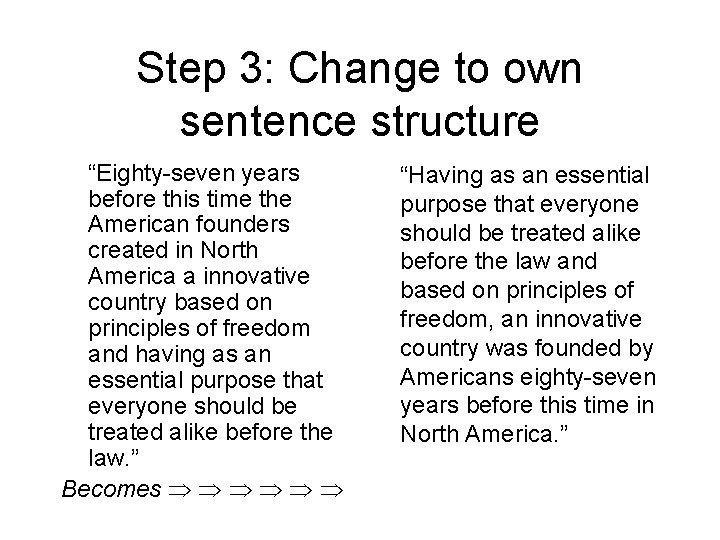

Step 3: Change to own sentence structure “Eighty-seven years before this time the American founders created in North America a innovative country based on principles of freedom and having as an essential purpose that everyone should be treated alike before the law. ” Becomes “Having as an essential purpose that everyone should be treated alike before the law and based on principles of freedom, an innovative country was founded by Americans eighty-seven years before this time in North America. ”

Summarizing Continued

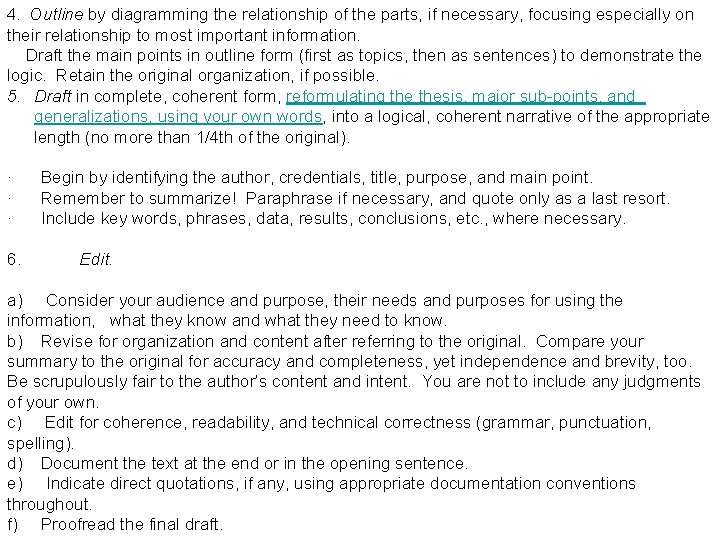

Summarizing procedure Below is a procedure for summarizing. Use as much of this material as is helpful to you—you needn’t stick slavishly to it. When all is said and done, a summary is an abbreviated statement of the author’s content and intent—the main points—in your own words and sentence structure. If you can do that well, you have summarized well. 1. Preview, scan, and skim the text. 2. Read the text “sympathetically, ” trying only to understand get the “big picture. ” 3. Reread the text, highlighting key terms and ideas and annotating as you go. Articulate the main point (thesis and generalizations). Divide the text into its main sections and subsections; identify main points or topic sentences for each · Introduction · Examples · Analysis · Conclusion, etc. You may find it helpful to mark off, delete, or otherwise indicate redundant and other non-essential information (e. g. , examples, details, trivia), so you needn’t rehearse them later.

4. Outline by diagramming the relationship of the parts, if necessary, focusing especially on their relationship to most important information. Draft the main points in outline form (first as topics, then as sentences) to demonstrate the logic. Retain the original organization, if possible. 5. Draft in complete, coherent form, reformulating thesis, major sub-points, and generalizations, using your own words, into a logical, coherent narrative of the appropriate length (no more than 1/4 th of the original). · Begin by identifying the author, credentials, title, purpose, and main point. · Remember to summarize! Paraphrase if necessary, and quote only as a last resort. · Include key words, phrases, data, results, conclusions, etc. , where necessary. 6. Edit. a) Consider your audience and purpose, their needs and purposes for using the information, what they know and what they need to know. b) Revise for organization and content after referring to the original. Compare your summary to the original for accuracy and completeness, yet independence and brevity, too. Be scrupulously fair to the author’s content and intent. You are not to include any judgments of your own. c) Edit for coherence, readability, and technical correctness (grammar, punctuation, spelling). d) Document the text at the end or in the opening sentence. e) Indicate direct quotations, if any, using appropriate documentation conventions throughout. f) Proofread the final draft.

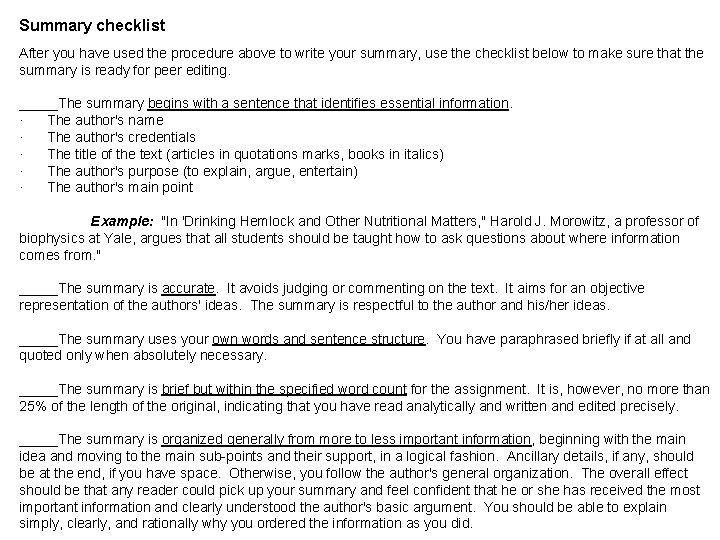

Summary checklist After you have used the procedure above to write your summary, use the checklist below to make sure that the summary is ready for peer editing. _____The summary begins with a sentence that identifies essential information. · The author's name · The author's credentials · The title of the text (articles in quotations marks, books in italics) · The author's purpose (to explain, argue, entertain) · The author's main point Example: "In 'Drinking Hemlock and Other Nutritional Matters, " Harold J. Morowitz, a professor of biophysics at Yale, argues that all students should be taught how to ask questions about where information comes from. " _____The summary is accurate. It avoids judging or commenting on the text. It aims for an objective representation of the authors' ideas. The summary is respectful to the author and his/her ideas. _____The summary uses your own words and sentence structure. You have paraphrased briefly if at all and quoted only when absolutely necessary. _____The summary is brief but within the specified word count for the assignment. It is, however, no more than 25% of the length of the original, indicating that you have read analytically and written and edited precisely. _____The summary is organized generally from more to less important information, beginning with the main idea and moving to the main sub-points and their support, in a logical fashion. Ancillary details, if any, should be at the end, if you have space. Otherwise, you follow the author's general organization. The overall effect should be that any reader could pick up your summary and feel confident that he or she has received the most important information and clearly understood the author's basic argument. You should be able to explain simply, clearly, and rationally why you ordered the information as you did.

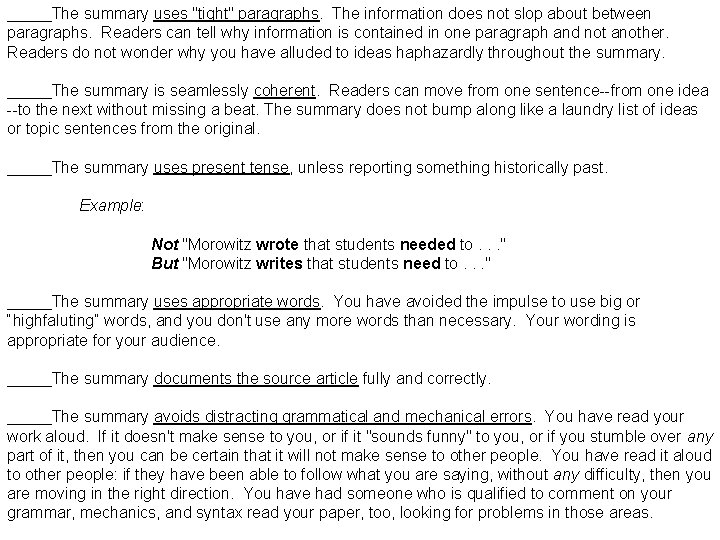

_____The summary uses "tight" paragraphs. The information does not slop about between paragraphs. Readers can tell why information is contained in one paragraph and not another. Readers do not wonder why you have alluded to ideas haphazardly throughout the summary. _____The summary is seamlessly coherent. Readers can move from one sentence--from one idea --to the next without missing a beat. The summary does not bump along like a laundry list of ideas or topic sentences from the original. _____The summary uses present tense, unless reporting something historically past. Example: Not "Morowitz wrote that students needed to. . . " But "Morowitz writes that students need to. . . " _____The summary uses appropriate words. You have avoided the impulse to use big or “highfaluting” words, and you don't use any more words than necessary. Your wording is appropriate for your audience. _____The summary documents the source article fully and correctly. _____The summary avoids distracting grammatical and mechanical errors. You have read your work aloud. If it doesn't make sense to you, or if it "sounds funny" to you, or if you stumble over any part of it, then you can be certain that it will not make sense to other people. You have read it aloud to other people: if they have been able to follow what you are saying, without any difficulty, then you are moving in the right direction. You have had someone who is qualified to comment on your grammar, mechanics, and syntax read your paper, too, looking for problems in those areas.

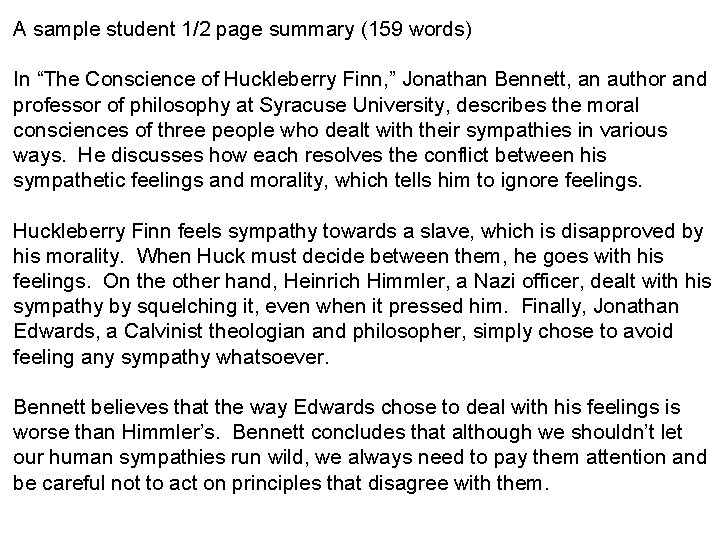

A sample student 1/2 page summary (159 words) In “The Conscience of Huckleberry Finn, ” Jonathan Bennett, an author and professor of philosophy at Syracuse University, describes the moral consciences of three people who dealt with their sympathies in various ways. He discusses how each resolves the conflict between his sympathetic feelings and morality, which tells him to ignore feelings. Huckleberry Finn feels sympathy towards a slave, which is disapproved by his morality. When Huck must decide between them, he goes with his feelings. On the other hand, Heinrich Himmler, a Nazi officer, dealt with his sympathy by squelching it, even when it pressed him. Finally, Jonathan Edwards, a Calvinist theologian and philosopher, simply chose to avoid feeling any sympathy whatsoever. Bennett believes that the way Edwards chose to deal with his feelings is worse than Himmler’s. Bennett concludes that although we shouldn’t let our human sympathies run wild, we always need to pay them attention and be careful not to act on principles that disagree with them.

A sample student 1 page summary (356 words) University of New York--Binghamton professor of philosophy, John Arthur, writes in, "Why Morality does not Depend on Religion, " that society cannot exist without morality. He also discusses whether society can exist without religion. He sees no connection between morality and religion: society could function without religion. Morality, he explains, is based on rules and how we feel when we act on them; religion involves worship of the supernatural. Religious people, he states, do the right thing because of consequences: they do right because God will bless them. However, an atheist who is raised to be honest could act in the same manner. Arthur states that some people cannot handle their own problems and may feel the need for a higher being, but Arthur adds we do not know if going to a higher being for assistance works. First, we need to know that there is a God and then how to approach Him. Scriptural inconsistencies and problems of receiving revelation, too, yield more questions than answers. Arthur also addresses Mortimer's idea that morality depends on religion. Mortimer states that we need religion to know right from wrong. This harmonizes with divine command theory. Divine command theory states that "without God's commands there would be no morality. " Arthur uses a conversation between Coppleston and Russell to demonstrate divine command theory and the difference between right and wrong. Ultimately, Coppleston argues that because of God there is a distinction between right and wrong. But Arthur continues that if religious persons understood divine command theory, they would reject it. Essentially, divine command theory says if God says something is right, it is right, and something is wrong because God says it is wrong. Arthur uses the absurd example of a parent trying to command a child: just because the parent says it is right does not make it right. Further, God could change his mind, saying what was once right is now wrong and visa versa. Arthur concludes that an ethical person could be religious or non-religious. Whether one is a theist or an atheist, he writes, it is best to follow the moral code best for oneself.