Subjective Universality Kant and Burke on the Beautiful

Subjective Universality: Kant and Burke on the Beautiful and the Sublime Brian Dominguez Berry 30 April 2018

Kant’s Claim “There must be attached to the judgment of taste, with the consciousness of an abstraction in it from a all interest, a claim to validity for everyone without the universality that pertains to objects, i. e. , it must be combined with a claim to subjective universality” (Kant, Critique of the Power of Judgement 97).

Overview ❖ Kant’s Claim ❖ Key Terms ❖ Philosophical Precedents (Baumgarten, Aristotle, Longinus) ❖ Burke on the Beautiful and the Sublime ❖ Kant on the Beautiful and the Sublime

Anti-Kant ❖ ❖ Beauty is in the eye of the beholder. De gustibus non est disputandum: In matters of taste there can be no disputes. ❖ Preferences are subjective/relative. ❖ The subjective is particular. ❖ Only objective concepts can be universal.

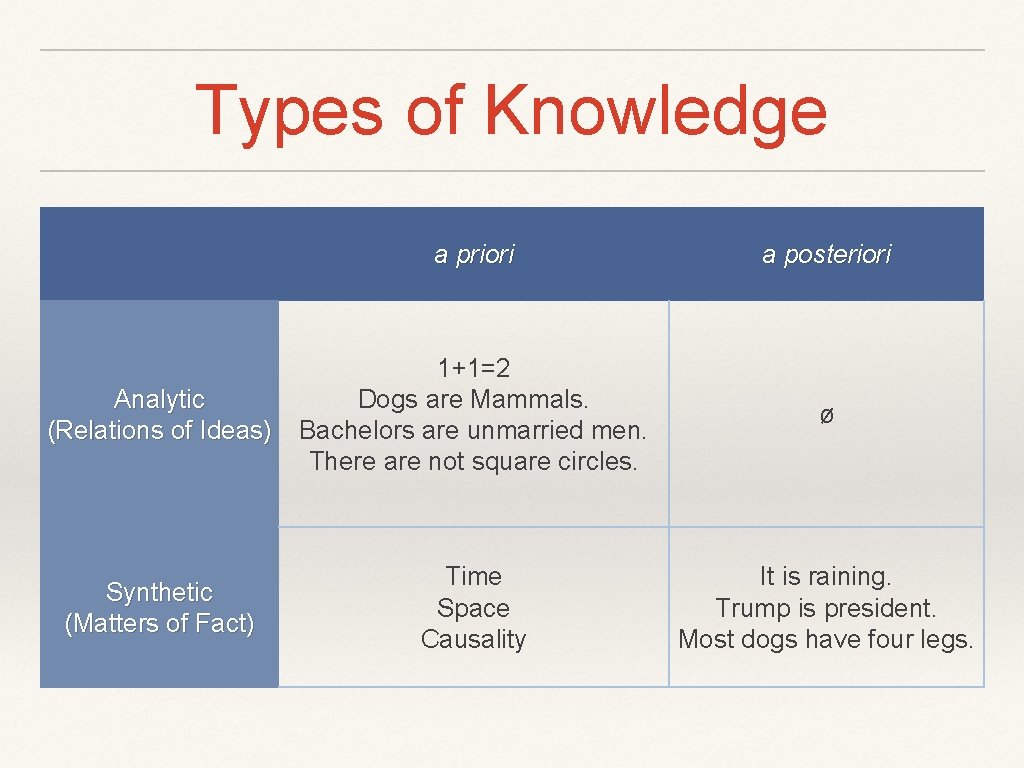

Key Terms ❖ ❖ Aesthetic (Gk αἰσθητικός): pertaining to feeling or the senses (sense perception). Judgement: an assertion or proposition (any linguistic or metalinguistic expression). A priori (Lt “from the earlier”): something known from reason alone, e. g. independent of experience. A posteriori (Lt “from the later”): something known only after experience.

Alexander Baumgarten ❖ Alexander Gottlieb Baumgarten (1714– 62) ❖ German Philosopher ❖ “Philosophical Considerations of Some Matters Concerning the Poem” (1735) ❖ Aesthetica (1750)

Baumgarten on Aesthetics “The Greek philosophers and the Church fathers have always carefully distinguished between the aistheta [objects of sense] and the noeta [objects of thought]… noeta are the object of logic, the aistheta are the subject of the episteme aisthetike or AESTHETICS [the science of perception]” (Baumgarten, Meditationes §CXVI).

Aristotle on the Universality of Poetry “The distinction between historian and poet is not in the one writing prose and the other verse—you might put the work of Herodotus into verse, and it would still be a species of history; it consists really in this, that the one describes the thing that has been, and the other a kind of thing that might be. Hence poetry is something more philosophic and of graver import than history, since its statements are of the nature rather of universals, whereas those of history are singulars. By a universal statement I mean one as to what such or such a kind of man will probably or necessarily say or do—which is the aim of poetry, though it affixes proper names to the characters; by a singular statement, one as to what, say, Alcibiades did or had done to him” (Aristotle, Poetics § 9).

Longinus’s Sublime The Sublime, wherever it occurs, consists in a certain loftiness and excellence of language, and that it is by this, and this only, that the greatest poets and prosewriters have gained eminence, and won themselves a lasting place in the Temple of Fame. A lofty passage does not convince the reason of the reader, but takes him out of himself. That which is admirable ever confounds our judgment, and eclipses that which is merely reasonable or agreeable. To believe or not is usually in our own power; but the Sublime, acting with an imperious and irresistible force, sways every reader whether he will or no. (On the Sublime)

Universal Sublime in Longinus It is proper to observe that in human life nothing is truly great which is despised by all elevated minds. …. It is natural to us to feel our souls lifted up by the true Sublime, and conceiving a sort of generous exultation to be filled with joy and pride, as though we had ourselves originated the ideas which we read. But when a passage is pregnant in suggestion, when it is hard, nay impossible, to distract the attention from it, and when it takes a strong and lasting hold on the memory, then we may be sure that we have lighted on the true Sublime. In general we may regard those words as truly noble and sublime which always please and please all readers. For when the same book always produces the same impression on all who read it, whatever be the difference in their pursuits, their manner of life, their aspirations, their ages, or their language, such a harmony of opposites gives irresistible authority to their favourable verdict. (Longinus On the Sublime)

Edmund Burke (1730– 97) ❖ Irish Philosopher and Statesman. ❖ Criticized the British treatment of the American colonies. ❖ Opposed the French Revolution.

The Sublime and the Beautiful ❖ Burke’s 1757 treatise was the first to clearly and completely separate the sublime and beautiful into separate categories. ❖ In the tradition of the English philosophical treatise, particularly inspired by Locke’s empiricism. ❖ Inspired Kant’s Critique of the Power of Judgement.

Discovering the Human Mind Through the Passions “The first and the simplest emotion which we discover in the human mind, is Curiosity. By curiosity, I mean whatever desire we have for, or whatever pleasure we take in, novelty…. But as those things, which engage us merely by their novelty, cannot attach us for any length of time, curiosity is the most superficial of all the affections; it changes its object perpetually… Curiosity blends itself more or less with all our passions. ” (Burke, The Sublime and the Beautiful I. 1)

Independence of Pain and Pleasure “It seems then necessary towards moving the passions of people advanced in life to any considerable degree, that the objects designed for that purpose, besides their being in some measure new, should be capable of exciting pain or pleasure from other causes. ” (Burke I. 2) “For my part, I am rather inclined to imagine, that pain and pleasure, in their most simple and natural manner of affecting, are each of a positive nature, and by no means necessarily dependent on each other for their existence. The human mind is often, and I think it is for the most part, in a state neither of pain nor pleasure, which I call a state of indifference. ” (Burke I. 2)

Removal of Pain ≠ Pleasure “I own it is not at first view so apparent, that the removal of a great pain does not resemble positive pleasure; but let us recollect in what state we have found our minds upon escaping some imminent danger, or on being released from the severity of some cruel pain. We have on such occasions found, if I am not much mistaken, the temper of our minds in a tenor very remote from that which attends the presence of positive pleasure; we have found them in a state of much sobriety, impressed with a sense of awe, in a sort of tranquillity shadowed with horror. ” (Burke I. 3)

Delight as Technical Term “The affection is undoubtedly positive; but the cause may be, as in this case it certainly is, a sort of Privation…. Very extraordinary it would be, if these affections, so distinguishable in their causes, so different in their effects, should be confounded with each other, because vulgar use has ranged them under the same general title. Whenever I have occasion to speak of this species of relative pleasure, I call it Delight; and I shall take the best care I can to use that word in no other sense. ” (Burke I. 4)

The Power of the Sublime “The passions therefore which are conversant about the preservation of the individual turn chiefly on pain and danger, and they are the most powerful of all the passions…. Whatever is fitted in any sort to excite the ideas of pain and danger, that is to say, whatever is in any sort terrible, or is conversant about terrible objects, or operates in a manner analogous to terror, is a source of the sublime; that is, it is productive of the strongest emotion which the mind is capable of feeling. ” (Burke I. 6– 7)

Natural and Sexual Selection ❖ ❖ “The passions belonging to the preservation of the individual turn wholly on pain and danger: those which belong to generation have their origin in gratifications and pleasures. ” (Burke I. 8) We might take Burke’s distinction between the psychological origin of the sublime and the beautiful as a precursor to Darwin’s natural and sexual selection.

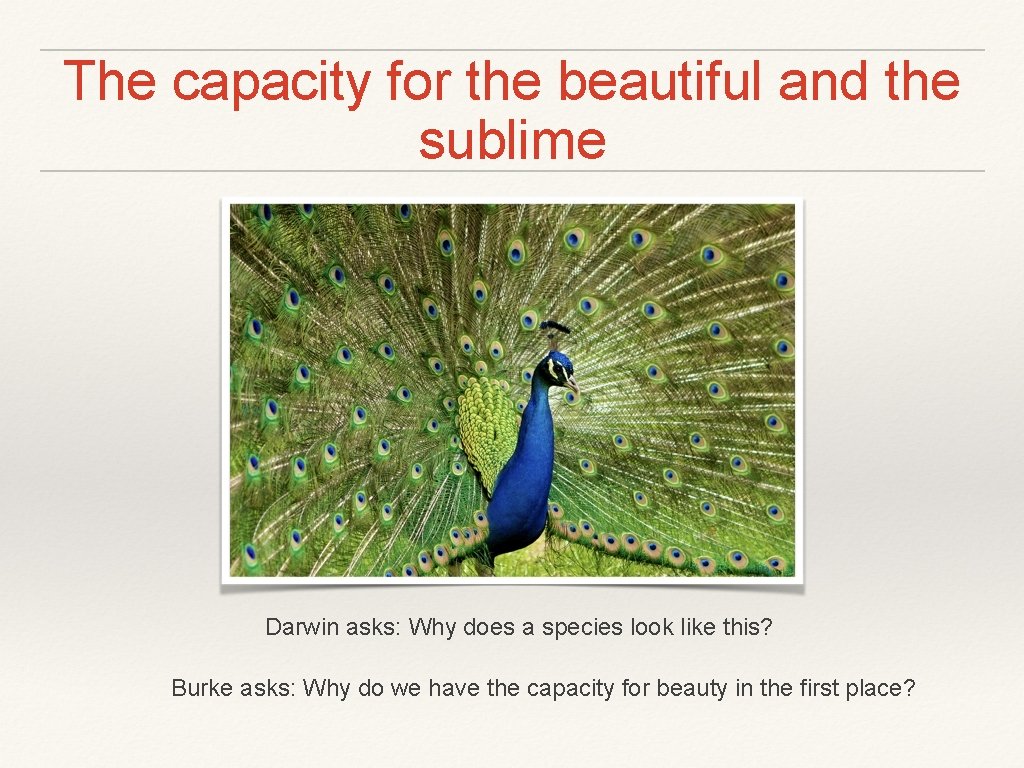

The capacity for the beautiful and the sublime Darwin asks: Why does a species look like this? Burke asks: Why do we have the capacity for beauty in the first place?

Pursuit of Pleasure “The generation of mankind is a great purpose, and it is requisite that men should be animated to the pursuit of it by some great incentive. It is therefore attended with a very high pleasure; but as it is by no means designed to be our constant business, it is not fit that the absence of this pleasure should be attended with any considerable pain. ” (Burke I. 9)

Back to Aristotle: Sympathy and Delight “We have a degree of delight, and that no small one, in the real misfortunes and pains of others…. Do we not read the authentic histories of scenes of this nature with as much pleasure as romances or poems, where the incidents are fictitious? ” (Burke I. 9) “Terror is a passion which always produces delight when it does not press too closely; and pity is a passion accompanied with pleasure, because it arises from love and social affection. ” (Burke I. 9)

Are you not entertained? “It is absolutely necessary my life should be out of any imminent hazard, before I can take a delight in the sufferings of others, real or imaginary. ” (Burke I. 15) “In imitated distresses the only difference is the pleasure resulting from the effects of imitation; for it is never so perfect, but we can perceive it is imitation, and on that principle are somewhat pleased with it. ” (Burke I. 15)

Back to Aristotle: Imitation “For as sympathy makes us take a concern in whatever men feel, so this affection prompts us to copy whatever they do; and consequently we have a pleasure in imitating…. It is by imitation far more than by precept, that we learn everything; and what we learn thus, we acquire not only more effectually, but more pleasantly. ” (Burke I. 16) “When the object represented in poetry or painting is such as we could have no desire of seeing in the reality, then I may be sure that its power in poetry or painting is owing to the power of imitation, and to no cause operating in the thing itself. ” (Burke I. 16)

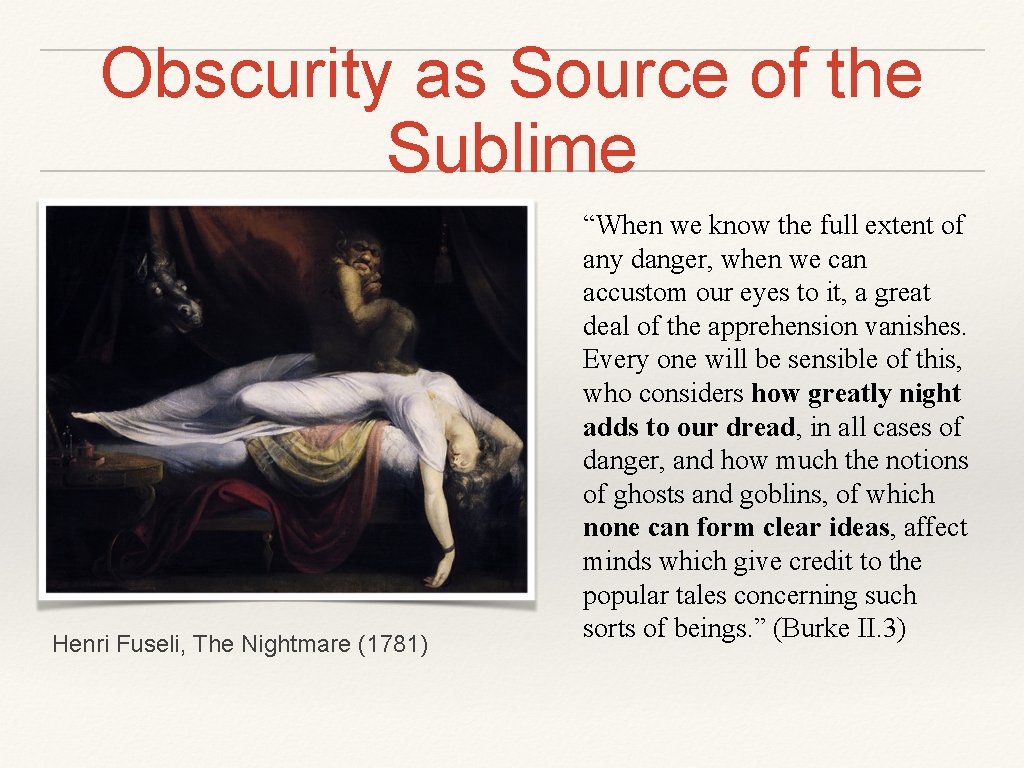

Obscurity as Source of the Sublime Henri Fuseli, The Nightmare (1781) “When we know the full extent of any danger, when we can accustom our eyes to it, a great deal of the apprehension vanishes. Every one will be sensible of this, who considers how greatly night adds to our dread, in all cases of danger, and how much the notions of ghosts and goblins, of which none can form clear ideas, affect minds which give credit to the popular tales concerning such sorts of beings. ” (Burke II. 3)

The Obscurity of Language If I make a drawing of a palace, or a temple, or a landscape, I present a very clear idea of those objects; but then (allowing for the effect of imitation, which is something) my picture can at most affect only as the palace, temple, or landscape would have affected in the reality. On the other hand, the most lively and spirited verbal description I can give raises a very obscure and imperfect idea of such objects; but then it is in my power to raise a stronger emotion by the description than I could do by the best painting. This experience constantly evinces. The proper manner of conveying the affections of the mind from one to another, is by words; there is a great insufficiency in all other methods of communication…. In reality, a great clearness helps but little towards affecting the passions. ” (Burke II. 3)

The Boundless Sublime “The ideas of eternity and infinity are among the most affecting we have; and yet perhaps there is nothing of which we really understand so little. ” (Burke II. 4) “Hardly anything can strike the mind with its greatness, which does not make some sort of approach towards infinity; which nothing can do whilst we are able to perceive its bounds; but to see an object distinctly, and to perceive its bounds, is one and the same thing. A clear idea is therefore another name for a little idea. ” (Burke II. 4)

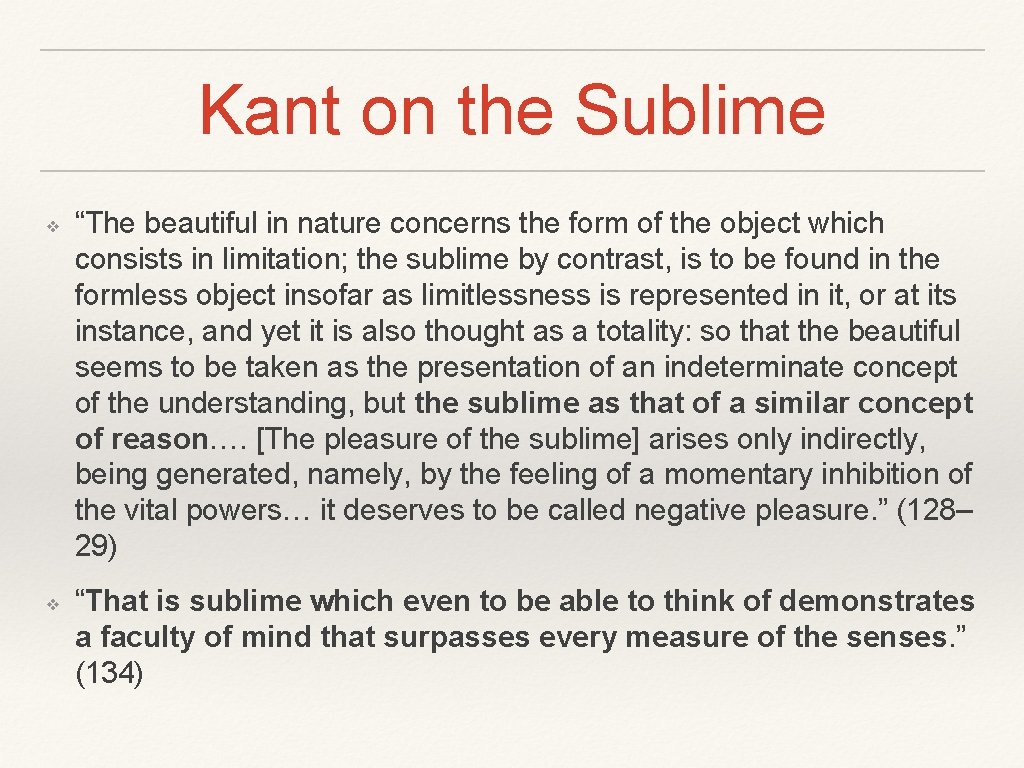

Beautiful Sublime Small Vaste in dimensions Smooth and Polished Great, Rugged, and Negligent Shuns Right Lines (Angles) Sometimes Angular Not Obscure Dark and Gloomy Light and Delicate Solid and Massive Founded on Pleasure Founded on Pain

Immanuel Kant (1724– 1804) ❖ Central figure of modern German philosophy whose work continues to inform all fields of philosophy. ❖ His three principle works, the three Critiques, cover the fields of epistemology, ethics, and aesthetics. ❖ Brought about a “Copernican” revolution in philosophy, wherein the human mind is seen to shape our experience of the world.

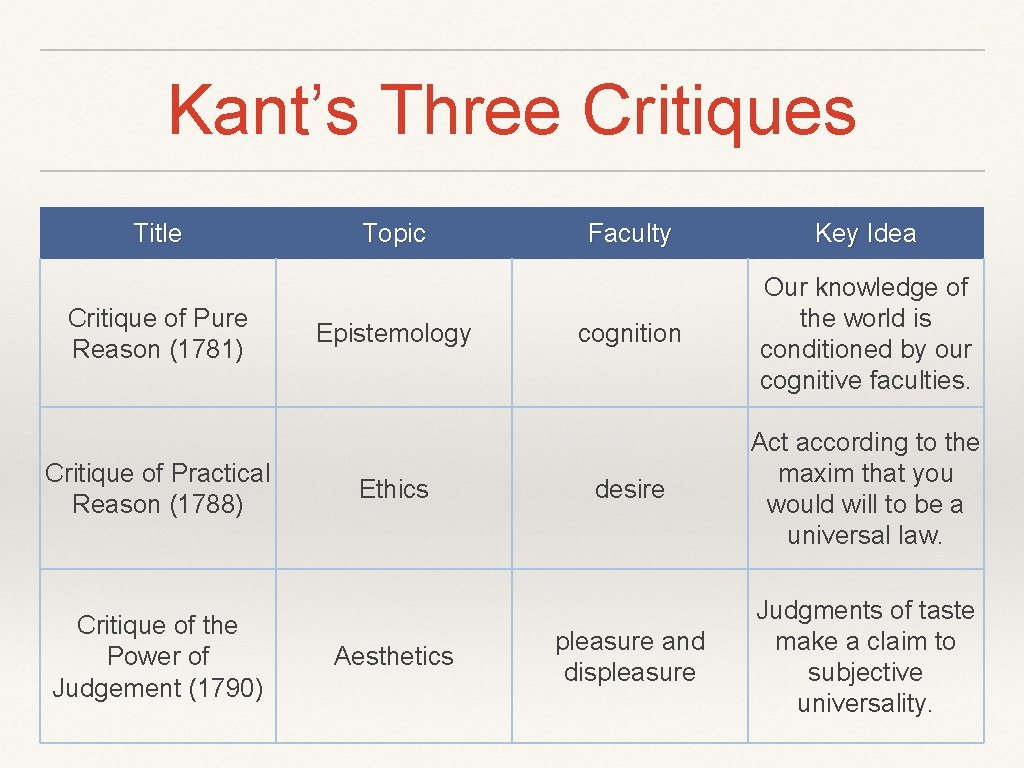

Kant’s Three Critiques Title Critique of Pure Reason (1781) Critique of Practical Reason (1788) Critique of the Power of Judgement (1790) Topic Epistemology Ethics Aesthetics Faculty Key Idea cognition Our knowledge of the world is conditioned by our cognitive faculties. desire Act according to the maxim that you would will to be a universal law. pleasure and displeasure Judgments of taste make a claim to subjective universality.

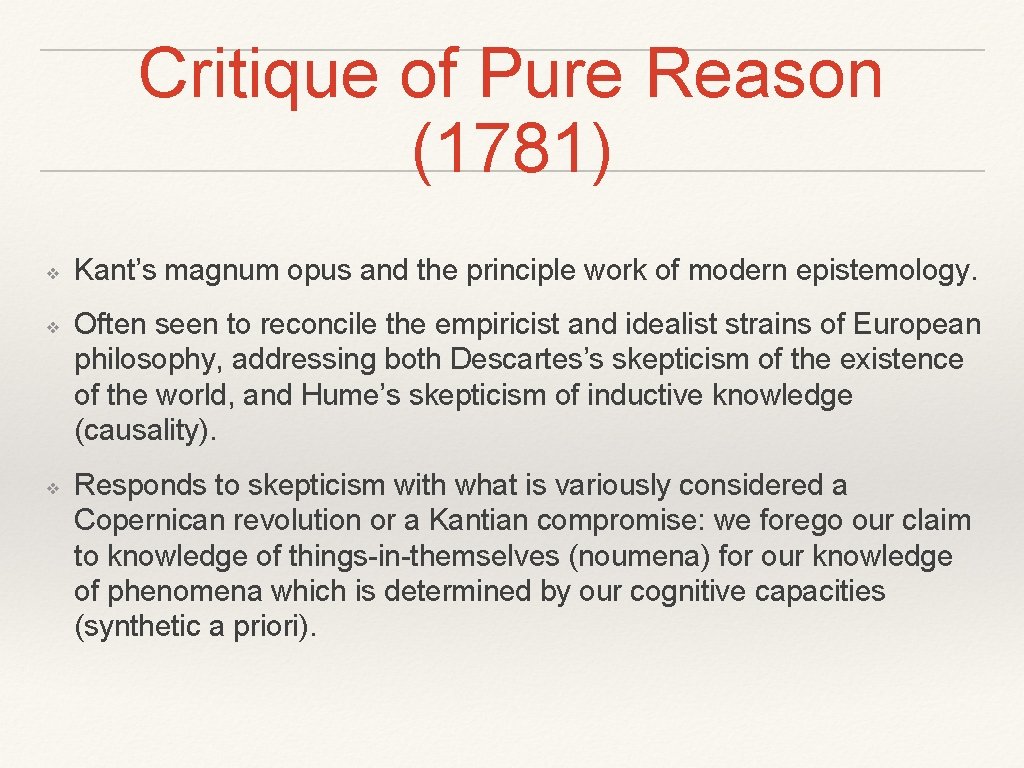

Critique of Pure Reason (1781) ❖ ❖ ❖ Kant’s magnum opus and the principle work of modern epistemology. Often seen to reconcile the empiricist and idealist strains of European philosophy, addressing both Descartes’s skepticism of the existence of the world, and Hume’s skepticism of inductive knowledge (causality). Responds to skepticism with what is variously considered a Copernican revolution or a Kantian compromise: we forego our claim to knowledge of things-in-themselves (noumena) for our knowledge of phenomena which is determined by our cognitive capacities (synthetic a priori).

Types of Knowledge a priori a posteriori Analytic (Relations of Ideas) 1+1=2 Dogs are Mammals. Bachelors are unmarried men. There are not square circles. ø Synthetic (Matters of Fact) Time Space Causality It is raining. Trump is president. Most dogs have four legs.

Critique of Practical Reason (1788) ❖ ❖ The compliment to the first critique, which deals with theoretical reason, the second critique deals with practical reason, our capacity to decide how to act. Best known for its categorical imperative: Act only according to that maxim whereby you can, at the same time, will that it should become a universal law.

Critique of the Power of Judgement (1790) ❖ Kant’s so-called third critique informs and unifies the first two critiques, even though it is not clear that Kant had conceived it as he was drafting the first two critiques. ❖ Although held in high esteem by Kant himself as one of his central works, the third critique puzzled Kant’s contemporaries, since it deals with aesthetic experience and judgement, which were not generally taken to be possible objects of rigorous philosophical inquiry.

The Antinomy of Determinism and Free Will ❖ ❖ The reason the first two critiques need unifying is that they elaborate a fundamental antinomy in our thinking about human thought and action: whether it is entirely determined by external causes or the result of individual free will. Theoretical philosophy or the philosophy of nature (1 st Critique) falls within the domain of the Understanding, which operates according to determinism. Practical philosophy or the philosophy of action (2 nd Critique) falls within the domain of Reason, which operates within the concept of freed will. Our capacity for Judgement overlaps with both the Understanding and Reason.

The Problem as Stated in the 3 rd Critique “The concept of nature certainly makes its objects representable in intuition, but not as things in themselves, rather as mere appearances, while the concept of freedom in its object makes a thing representable in itself but not in the intuition, and thus neither of the two can provide a theoretical cognition of its object (and even of the thinking subject) as a thing in itself, which would be the supersensible, the idea of which must underlie the possibility of all those objects of experience, but which itself can never be elevated and expanded into a cognition” (Kant, Critique of the Power of Judgement 63).

The Problem cont. “Now although there is an incalculable gulf fixed between the domain of the concept of nature, as the sensible, and the domain of the concept of freedom, as the supersensible, so that from the former to the latter (thus by means of theoretical use of reason) no transition is possible, just as if there were so many different worlds, the first of which can have no influence on the second: yet the latter should have an influence on the former, namely the concept of freedom should make the end that is imposed by its laws real in the sensible world; and nature must consequently also be able to be conceived in such a way that the lawfulness of its form is at least in agreement with the possibility of the ends that are to be realized in it in accordance with the laws of freedom” (Kant 63).

The 3 rd Critique’s Solution “But in the family of the higher faculties of cognition there is still an intermediary between the understanding and reason. There is the power of judgement, about which one has cause to presume, by analogy, that it too should contain in itself a priori, if not exactly its own legislation, then still a proper principle of its own for seeking laws, although a merely subjective one; which, even though it can claim no field of objects as its domain, can nevertheless have some territory and a certain constitution of it, for which precisely this principle only might be valid” (Kant 64).

Examples of (Aesthetic) Judgments ❖ This wine is red. ❖ This wine is a garnacha from southern Spain. ❖ This wine is good. ❖ This wine has hints of currant and blackberry. ❖ This wine is a summer afternoon in Sevilla.

Determining and Reflecting Judgements ❖ ❖ ❖ A judgement is the faculty for thinking of the particular as contained under the universal. Determining Judgement: the universal is given and the particular is subsumed under the universal (deduction). Reflecting Judgement: only the particular is given for which the universal is to be found (induction).

The Purposiveness of Nature ❖ ❖ We take pleasure in the thought that the laws of nature are consistent and unified, and that nature has a purpose or an end (teleology). “That the concept of the purposiveness of nature belongs among the transcendental principles can readily be seen from the maxims of the power of judgment… which nevertheless pertain to nothing other than the possibility of experience… as determined by a manifold of particular laws… various rules whose necessity cannot be demonstrated from concepts… ‘Nature takes the shortest way’ [etc. ]” (Kant 69).

The Pleasure of Purposiveness “Now this transcendental concept of the purposiveness of nature is neither a concept of nature nor a concept of freedom, since it attributes nothing at all to the object (of nature), but rather only represents the unique way in which we must proceed in reflection on the objects of nature with the aim of a thoroughly connected experience, consequently it is a subjective principle (maxim) of the power of judgement; hence we are also delighted (strictly speaking, relieved of a need) when we encounter such a systematic unity among merely empirical laws, just as if it were a happy accident which happened to favor our aim, even though we necessarily had to assume that there is such a unity, yet without having been able to gain insight into it and to prove it. ” (Kant 71)

The Aesthetic Representation of Purposiveness “The subjective aspect in a representation which cannot become an element of cognition at all is the pleasure or displeasure connected with it…. Now the purposiveness of a thing… is also not a property of the object itself…. Thus the purposiveness that precedes the cognition of an object … is the subjective aspect of it that cannot become an element of cognition at all. The object is therefore called purposive in this case only because its representation is immediately connected with the feeling of pleasure; and this representation itself is an aesthetic representation of purposiveness. ” (Kant 75)

The Universality of Reflecting Judgements “That object the form of which (not the material aspect of its representation, as sensation) in mere reflection on it (without any intention of acquiring a concept from it) is judged as the ground of a pleasure in the representation of such an object—with its representation this pleasure is also judged to be necessarily combined, consequently not merely for the subject who apprehends this form but for everyone who judges at all. The object is then called beautiful; and the faculty for judging through such a pleasure (consequently also with universal validity) is called taste. ” (Kant 76)

(However) Beauty is Subjective “In order to decide whether or not something is beautiful, we do not relate the representation by means of understanding to the object for cognition, but rather relate it by means of the imagination (perhaps combined with the understanding) to the subject and its feeling of pleasure or displeasure. The judgment of taste is therefore not a cognitive judgment, hence not a logical one, but is rather aesthetic … cannot be other than subjective. Any relation of representations … can be objective … but not the relation to the feeling of pleasure and displeasure. ” (Kant 89)

The Judgment of Taste is Disinterested ❖ “The satisfaction that we combine with the representation the existence of an object is called interest…. If someone asks me whether I find the palace that stands before me beautiful…. One only wants to know whether the mere representation of the object is accompanied with satisfaction in me” (90– 91). ❖ “One must not be in the least biased in favor of the existence of the thing, but must be entirely indifferent in this respect in order to play the judge in matters of taste” (91).

You Can’t Eat Your Cake and Judge It Too

The Judgement of Taste: ❖ Is a reflecting (not determining) judgment. ❖ Grounds the concept of the purposiveness of nature. ❖ Relates to subjective pleasure and displeasure. ❖ But nonetheless claims universal validity. ❖ Is disinterested.

Three Kinds of Satisfaction ❖ ❖ ❖ The Agreeable: That which pleases the senses in sensation. The Good: That which pleases by means of the reason alone, through the mere concept. The Beautiful: That which, without concepts, is represented as the object of a universal satisfaction.

The Agreeable ❖ “With regard to the agreeable, everyone is content that his judgment, which he grounds on a private feeling … be restricted merely to his own person. ” (97) ❖ “When he says that sparkling wine from the Canaries is agreeable, someone else should improve his expression and remind him that he should say ‘It is agreeable to me. ’” (97) ❖ “With regard to the agreeable, the principle Everyone has his own taste (of the senses) is valid. ” (97)

The Good “With regard to the good … judgments also rightly lay claim to validity for everyone; but the good is represented as an object of a universal satisfaction only through a concept, which is not the case either with the agreeable or with the beautiful. ” (98)

The Beautiful "It would be ridiculous if … someone who prided himself on his taste thought to justify himself thus: ‘This object (the building we are looking at, the clothing someone is wearing, the concert that we hear, the poem that is presented for judging) is beautiful for me. ’ For he must not call it beautiful if it pleases merely him…. Hence he says that the thing is beautiful, and does not count on the agreement of others … but rather demands it of them. ” (98)

Universal Voice ❖ ❖ “The taste of reflection, which, as experience teaches, is often enough rejected in its claim to the universal validity of its judgement (about the beautiful)… while those who make those judgements do not find themselves in conflict over the possibility of such a claim, but only find it impossible to agree on the correct application of this faculty in particular cases. ” (99) “In the judgement of taste nothing is postulated except such a universal voice with regard to satisfaction without the mediation of concepts, hence the possibility of an aesthetic judgment that could at the same time be considered valid for everyone. The judgement of taste does not itself postulate the accord … it only ascribes this agreement to everyone. ” (101)

Kant on the Sublime ❖ ❖ “The beautiful in nature concerns the form of the object which consists in limitation; the sublime by contrast, is to be found in the formless object insofar as limitlessness is represented in it, or at its instance, and yet it is also thought as a totality: so that the beautiful seems to be taken as the presentation of an indeterminate concept of the understanding, but the sublime as that of a similar concept of reason…. [The pleasure of the sublime] arises only indirectly, being generated, namely, by the feeling of a momentary inhibition of the vital powers… it deserves to be called negative pleasure. ” (128– 29) “That is sublime which even to be able to think of demonstrates a faculty of mind that surpasses every measure of the senses. ” (134)

Taste as Sensus Communis ❖ ❖ ❖ Not ‘common sense’ in our usually use of the term. “By ‘sensus communis, ’ must be understood the idea of a communal sense, i. e. , a faculty for judging that in its reflection takes account (a priori) of everyone else’s way of representing in thought, in order as it were to hold its judgment up to human reason as a whole and thereby avoid the illusion which, from subjective private conditions that could easily be held to be objective, would have a detrimental influence on the judgment” (173). “One means by ‘sense’ the feeling of pleasure. Once could even define taste as the faculty for judging that which makes our feeling in a given representation universally communicable without the mediation of concepts” (175).

- Slides: 54