Strong Induction Normal Induction Induction If we prove

- Slides: 18

Strong Induction “Normal” Induction: Induction If we prove that 1) P(n 0) 2) For any k≥n 0, if P(k) then P(k+1) Then P(n) is true for all n≥n 0. “Strong” Induction: Induction If we prove that 1) Q(n 0) 2) For any k≥n 0, if Q(j) for all j from n 0 to k then Q(k+1) Then Q(k) is true for all k≥n 0. These two are equivalent! Why? Set P(n) to be the predicate “If n 0 ≤ j ≤ n then Q(j)” – P(n 0) ≡ Q(n 0) – P(k) ≡ Q(j) holds for all j between n 0 and k UCI ICS/Math 6 D 1

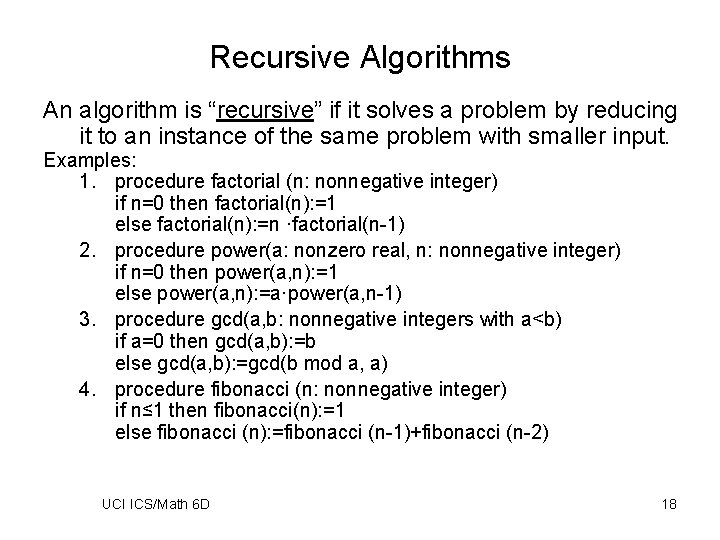

Proof by Strong Induction: Jigsaw Puzzle Each “step” in assembling a jigsaw puzzle consists of putting together two already assembled blocks of pieces where each single piece is considered a block itself. P(n) = “It takes exactly n-1 steps to assemble a saw puzzle of n pieces. ” Basis Step: P(1) is (trivially) true. Inductive Step: We assume P(j) true for all j≤k and we’ll argue P(k+1): The last step in assembling a puzzle of k+1 pieces is to put together two blocks: one of size j>0 and one of size k+1 -j, for some j. Since 0<j, k+1 -j≤k, P(j) and P(k+1 -j) are both assumed true. And so, the total number of steps to assemble a puzzle with n+1 pieces is 1 + (j-1) + ((k+1 -j)-1) = k = (k+1)-1. (This implies P(k+1), and hence ends the inductive part, and thus also the proof. ) UCI ICS/Math 6 D 2

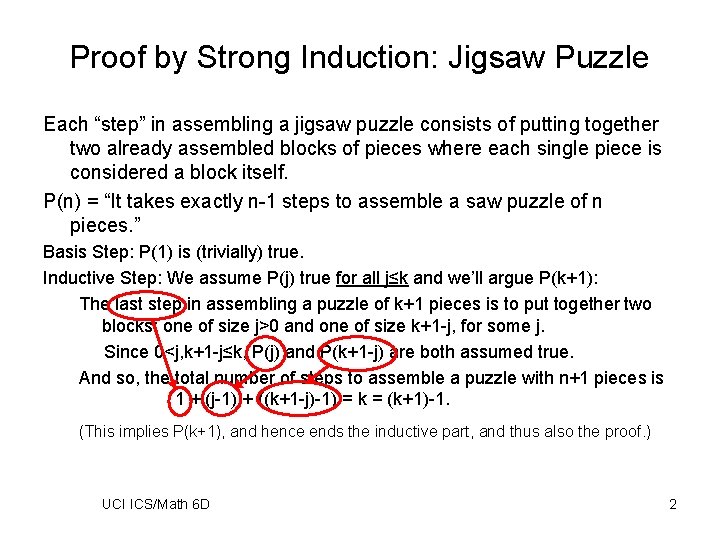

More Examples of Theorems with easy Proofs using Strong Induction Thm 1: The second player always wins the following game: – Starting with 2 piles each containing the same number of matches, players alternately remove any non-zero number of matches from one of the piles. – The winner is the person who removes the last match. Thm 2: Every n>1 can be written as the product of primes. Thm 3: Every postage amount of at least 18 cents can be formed using just 4 -cent and 7 -cent stamps: - First 4 cases: 18=2*7+4, 19=7+3*4, 20=5*4, 21=3*7 - Afterwards, using strong induction: Take any k≥ 21. By (strong) inductive assumption, and by the 4 cases above, k-3=i*7+j*4 for some i, j. Therefore k+1=i*7+(j+1)*4, which ends the inductive step. (Btw, starting from 18 may seem weird, but you just can’t do it for 17. . . ) UCI ICS/Math 6 D 3

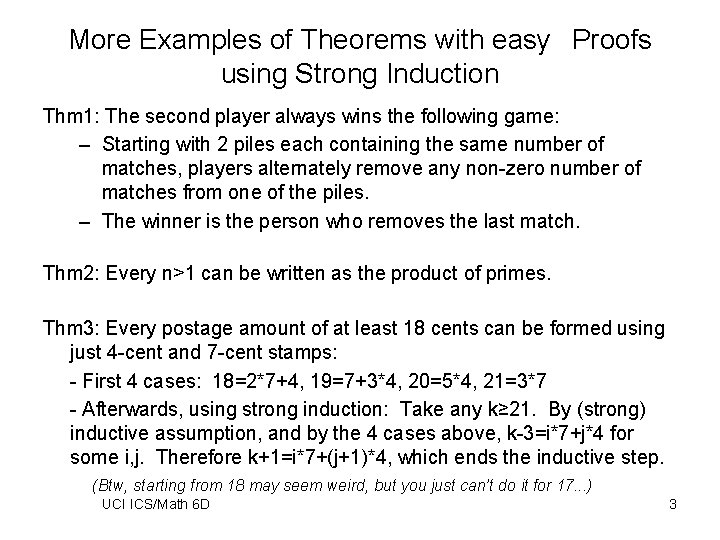

Basis for Induction: Integers are well ordered Induction is based on the fact that the integers are “well ordered”, i. e. Any non-empty set of integers which is bounded below i. e. there exists b (not necessarily in S) s. t. b ≤ x for all x in S contains a smallest element i. e. e in S s. t. for all x in S we have e ≤ x. Why does well-ordering imply induction? Assume (*) P(0) and (**) P(k)→P(k+1) for all k≥ 0. We’ll show that P(n)=T for all n≥ 0 (thus showing that induction works): Define (***) S = {n>0 | P(n)=F}. Assume S non-empty. By well-ordering of N, there is a least element e of S. Consider element e– 1: Since P(e) = F then by (**) also P(e– 1) = F. Note that e– 1 cannot be equal to 0 because P(0) = T by (*). But then by (***), e– 1 is in S, so e is not the least element of S… Þ Contradiction! Therefore S must be empty. Therefore P(n)=T for all n ≥ 0. UCI ICS/Math 6 D 4

Well Ordering can be used directly to prove things (i. e. not necessarily via induction) Theorem: If a and b are integers, not both 0, then s, t Z (s*a + t*b = gcd( a, b )). Proof: For any a, b define S = {n>0 | s, t Z n= s*a + t*b}. By the well-ordering of Z, S has a smallest element, call it d. Choose s and t so that d = s*a + t*b. Claim: d is a common divisor of a and b. Proof that d | a: Writing d = q*a + r where 0≤r<d. If r=0 then d | a. If r>0 then since r = d – q*a = (s*a + t*b) – q*a = (s - q)*a + t*b we would have r S. But since r<d it would mean that d is not the smallest element of S => contradiction => and therefore r=0 (and hence d | a). Similarly, d | b. d is the greatest common divisor since any common divisor of a and b must also divide s*a + t*b = d. UCI ICS/Math 6 D 5

Recursive (Inductive) Definitions A function f: N→R is defined “recursively” by specifying (1) f(0), its value at 0, and (2) f(n), for n>0, in terms of f(1), …. , f(n-1), i. e. in terms of f(k)’s for k<n. Examples: – f(n)=n! can be specified as f(0)=1 and, for n>0, f(n)=n*f(n-1). – For any a, fa(n)=an, can be specified as fa(0)=1 and, for n>0, fa(n)=a*fa(n-1) Note: In many cases, we specify f(k) explicitly not only for f(0) but also for f(1), f(2), …, f(m) for some m>0, and then use a recursive formula to define f(n) for all n>m. UCI ICS/Math 6 D 6

Fibonacci Numbers are Recursively Defined The Fibonacci numbers f 0, f 1, f 2, …, fn, …, are defined by (1) f 0=0, f 1=1 (2) fn=fn-1+fn-2, for n≥ 2 (Btw, we can also use F(n) instead of fn to designate n-th Fibonacci number. ) The first 18 Fibonacci numbers are: f 0=0, f 1=1, f 2=1, f 3=2, f 4=3, f 5=5, f 6=8, f 7=13, f 8=21, f 9=34, f 10=55, f 10=89, f 11=144, f 12=233, f 13=377, f 14=610, f 15=987, f 11=1597, f 12=2584, f 13=4181, f 14=6765, f 15=10946, f 16=17711, f 17=28657, f 18=46368, . . . Ref: http: //en. wikipedia. org/wiki/Fibonacci_number Question: Are they growing exponentially, i. e. like fn ≈ an for some a? UCI ICS/Math 6 D 7

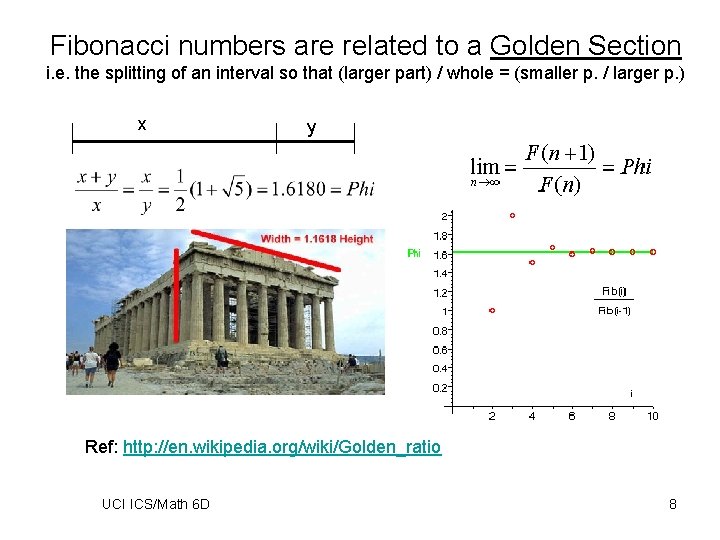

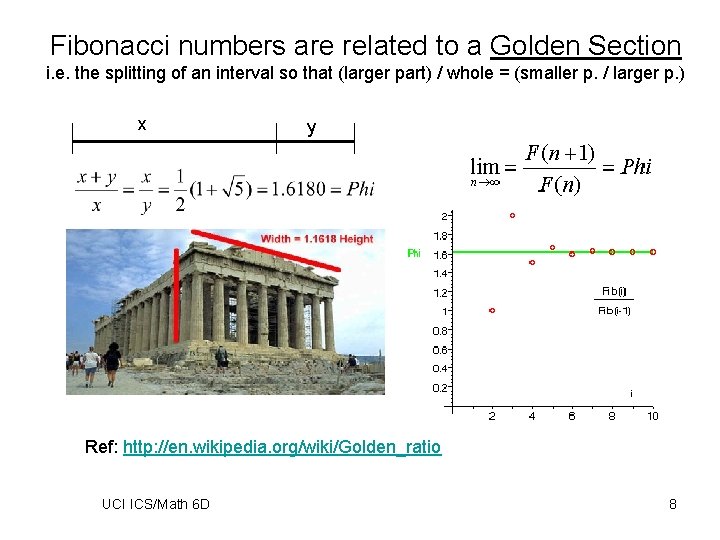

Fibonacci numbers are related to a Golden Section i. e. the splitting of an interval so that (larger part) / whole = (smaller p. / larger p. ) x y Ref: http: //en. wikipedia. org/wiki/Golden_ratio UCI ICS/Math 6 D 8

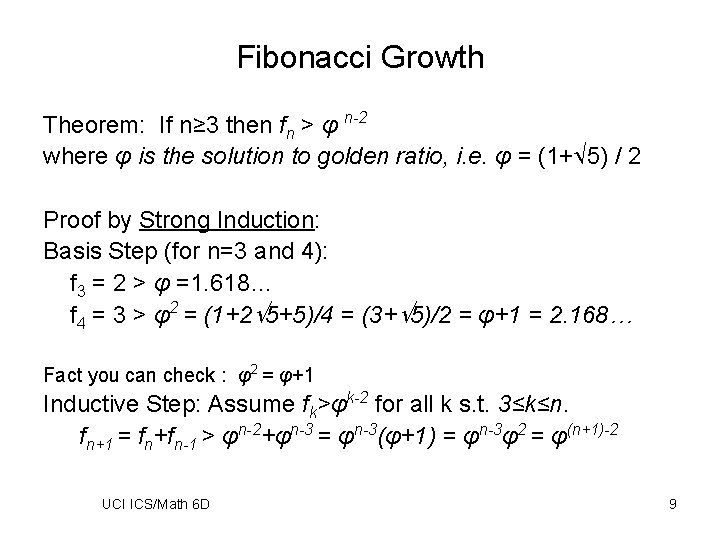

Fibonacci Growth Theorem: If n≥ 3 then fn > φ n-2 where φ is the solution to golden ratio, i. e. φ = (1+ 5) / 2 Proof by Strong Induction: Basis Step (for n=3 and 4): f 3 = 2 > φ =1. 618… f 4 = 3 > φ2 = (1+2 5+5)/4 = (3+ 5)/2 = φ+1 = 2. 168… Fact you can check : φ2 = φ+1 Inductive Step: Assume fk>φk-2 for all k s. t. 3≤k≤n. fn+1 = fn+fn-1 > φn-2+φn-3 = φn-3(φ+1) = φn-3φ2 = φ(n+1)-2 UCI ICS/Math 6 D 9

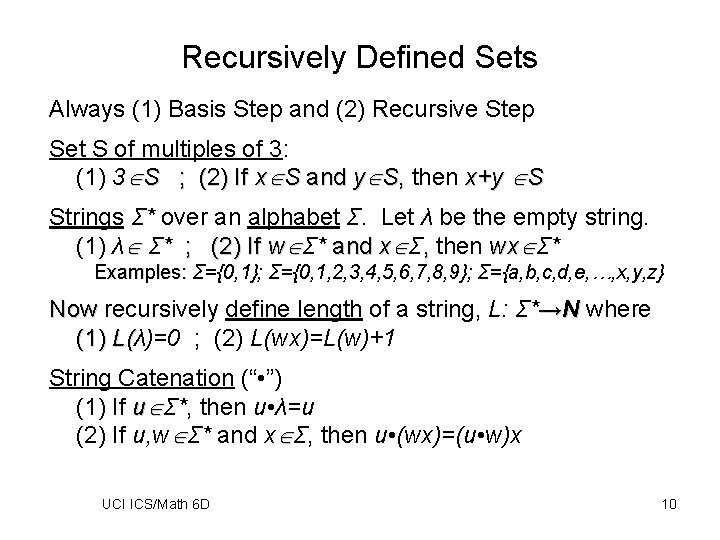

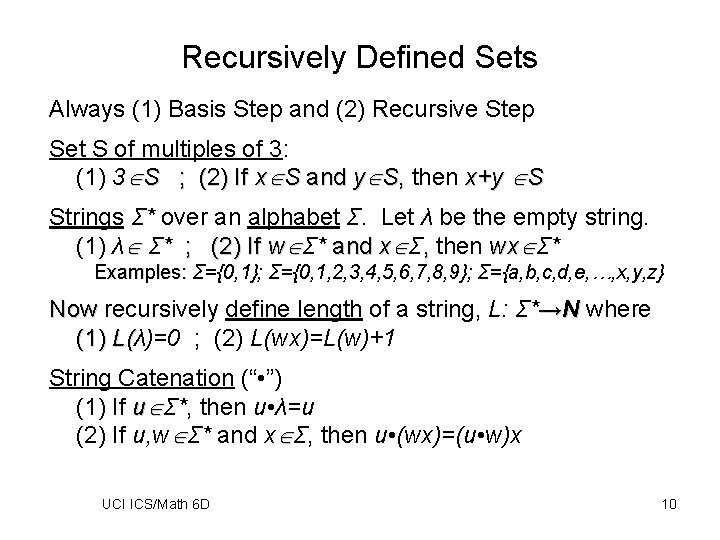

Recursively Defined Sets Always (1) Basis Step and (2) Recursive Step Set S of multiples of 3: (1) 3 S ; (2) If x S and y S, then x+y S Strings Σ* over an alphabet Σ. Let λ be the empty string. (1) λ Σ* ; (2) If w Σ* and x Σ, then wx Σ* Examples: Σ={0, 1}; Σ={0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9}; Σ={a, b, c, d, e, …, x, y, z} Now recursively define length of a string, L: Σ*→N where (1) L(λ)=0 ; (2) L(wx)=L(w)+1 L( String Catenation (“ • ”) (1) If u Σ*, then u • λ=u (2) If u, w Σ* and x Σ, then u • (wx)=(u • w)x UCI ICS/Math 6 D 10

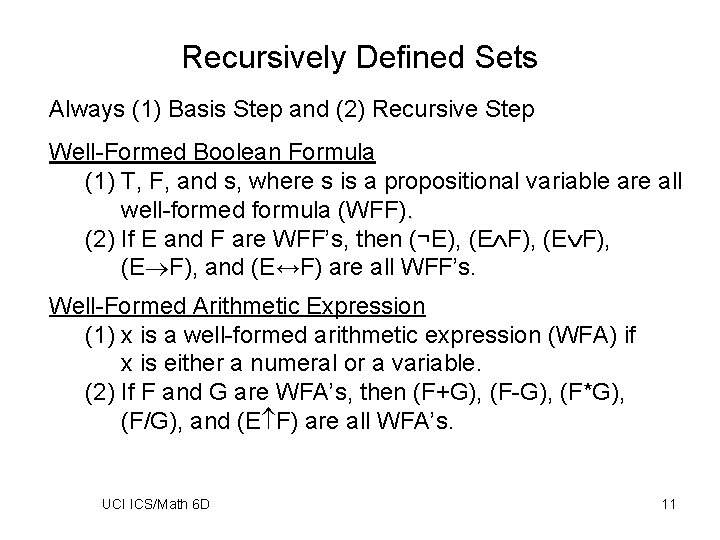

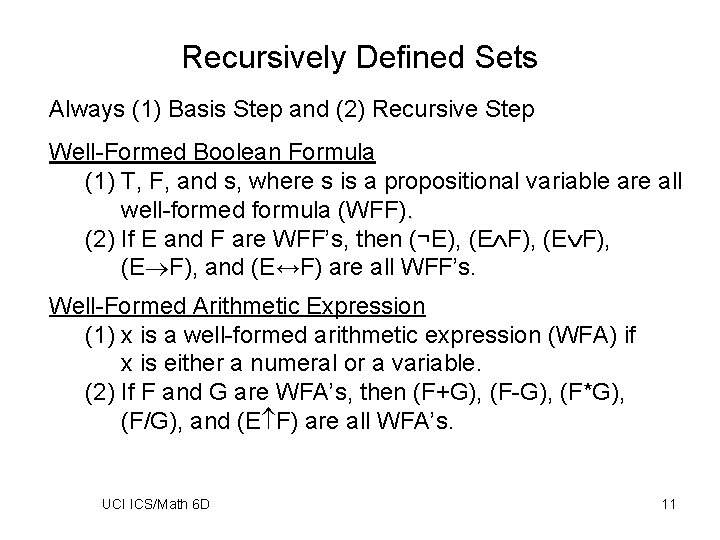

Recursively Defined Sets Always (1) Basis Step and (2) Recursive Step Well-Formed Boolean Formula (1) T, F, and s, where s is a propositional variable are all well-formed formula (WFF). (2) If E and F are WFF’s, then (¬E), (E F), and (E↔F) are all WFF’s. Well-Formed Arithmetic Expression (1) x is a well-formed arithmetic expression (WFA) if x is either a numeral or a variable. (2) If F and G are WFA’s, then (F+G), (F-G), (F*G), (F/G), and (E F) are all WFA’s. UCI ICS/Math 6 D 11

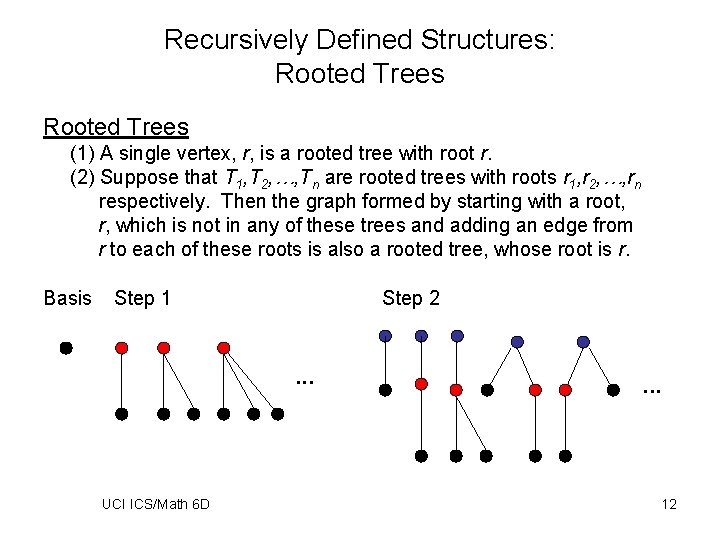

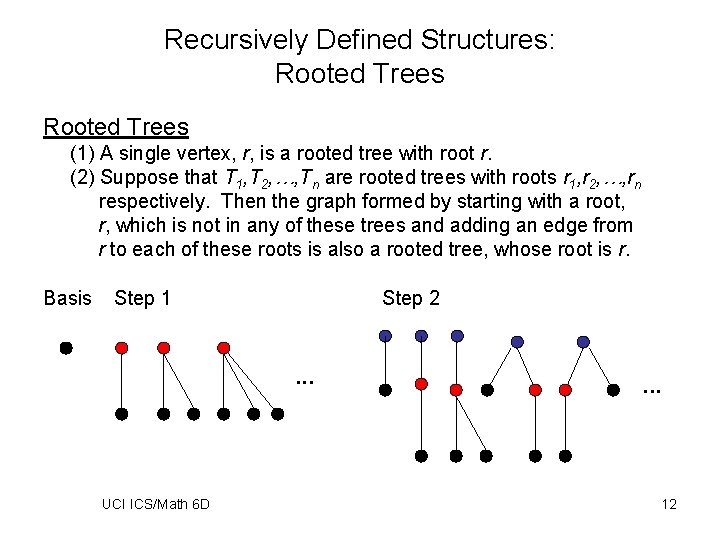

Recursively Defined Structures: Rooted Trees (1) A single vertex, r, is a rooted tree with root r. (2) Suppose that T 1, T 2, …, Tn are rooted trees with roots r 1, r 2, …, rn respectively. Then the graph formed by starting with a root, r, which is not in any of these trees and adding an edge from r to each of these roots is also a rooted tree, whose root is r. Basis Step 1 Step 2 . . . UCI ICS/Math 6 D . . . 12

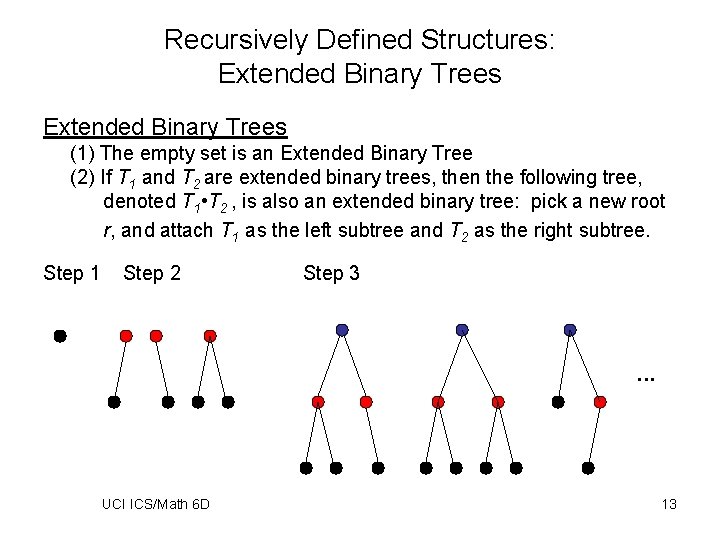

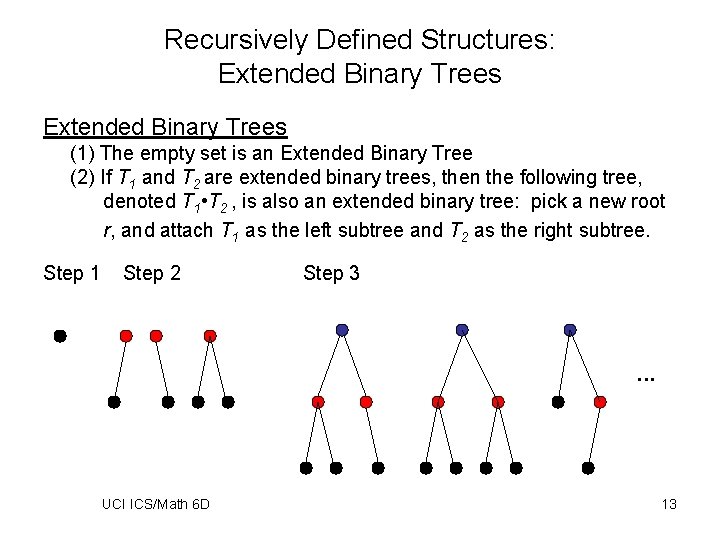

Recursively Defined Structures: Extended Binary Trees (1) The empty set is an Extended Binary Tree (2) If T 1 and T 2 are extended binary trees, then the following tree, denoted T 1 • T 2 , is also an extended binary tree: pick a new root r, and attach T 1 as the left subtree and T 2 as the right subtree. Step 1 Step 2 Step 3 . . . UCI ICS/Math 6 D 13

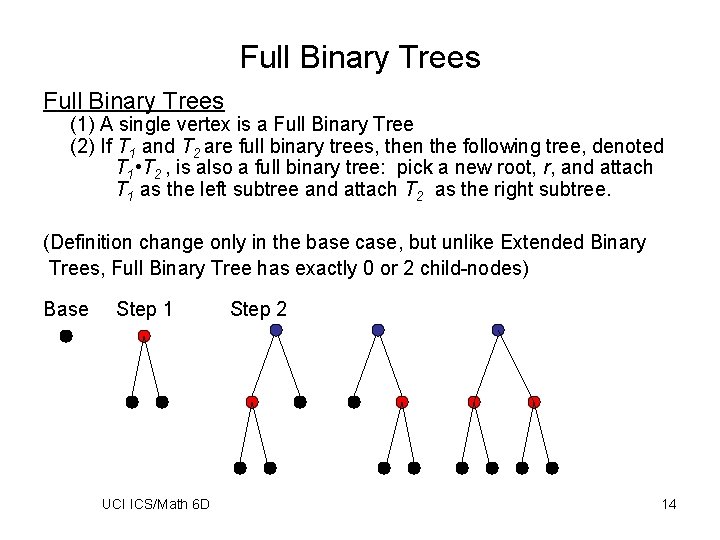

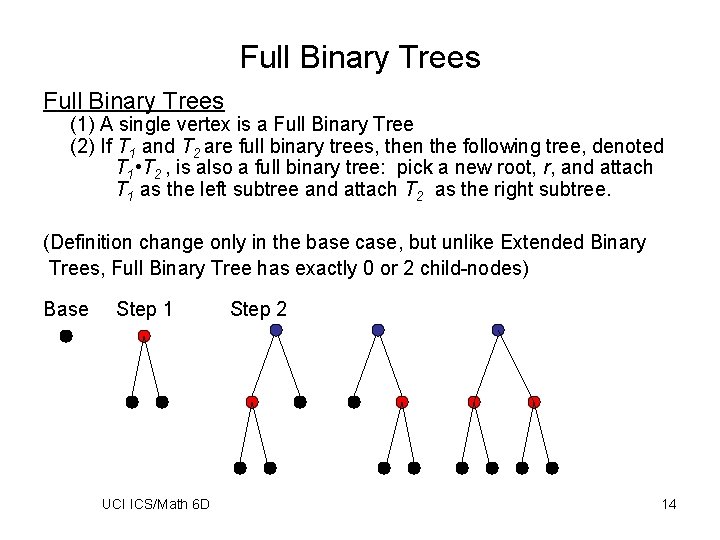

Full Binary Trees (1) A single vertex is a Full Binary Tree (2) If T 1 and T 2 are full binary trees, then the following tree, denoted T 1 • T 2 , is also a full binary tree: pick a new root, r, and attach T 1 as the left subtree and attach T 2 as the right subtree. (Definition change only in the base case, but unlike Extended Binary Trees, Full Binary Tree has exactly 0 or 2 child-nodes) Base Step 1 UCI ICS/Math 6 D Step 2 14

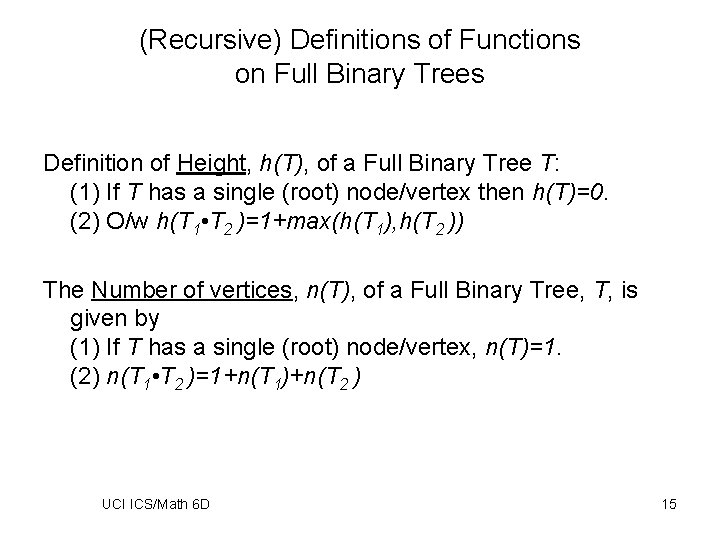

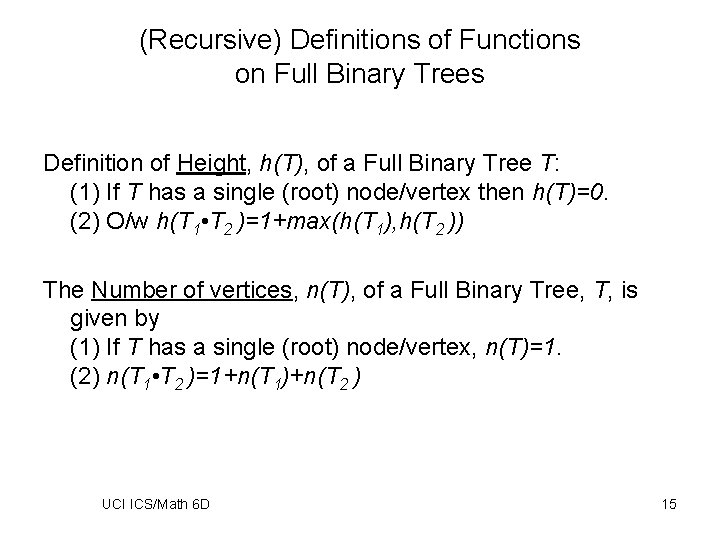

(Recursive) Definitions of Functions on Full Binary Trees Definition of Height, h(T), of a Full Binary Tree T: (1) If T has a single (root) node/vertex then h(T)=0. (2) O/w h(T 1 • T 2 )=1+max(h(T 1), h(T 2 )) The Number of vertices, n(T), of a Full Binary Tree, T, is given by (1) If T has a single (root) node/vertex, n(T)=1. (2) n(T 1 • T 2 )=1+n(T 1)+n(T 2 ) UCI ICS/Math 6 D 15

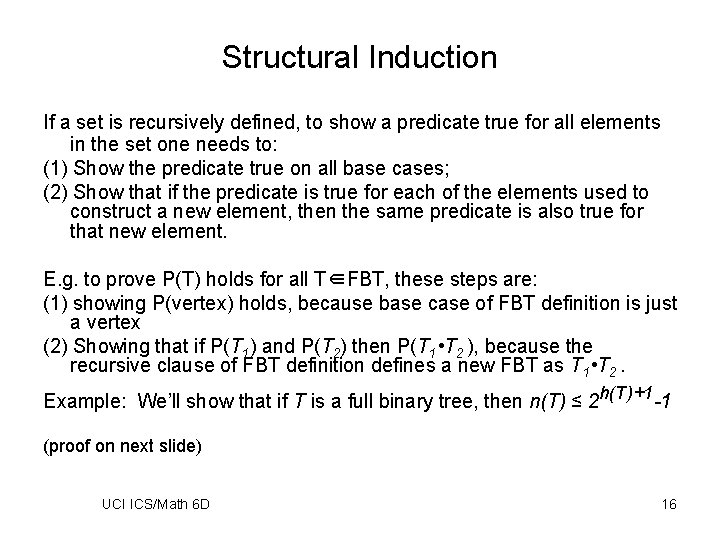

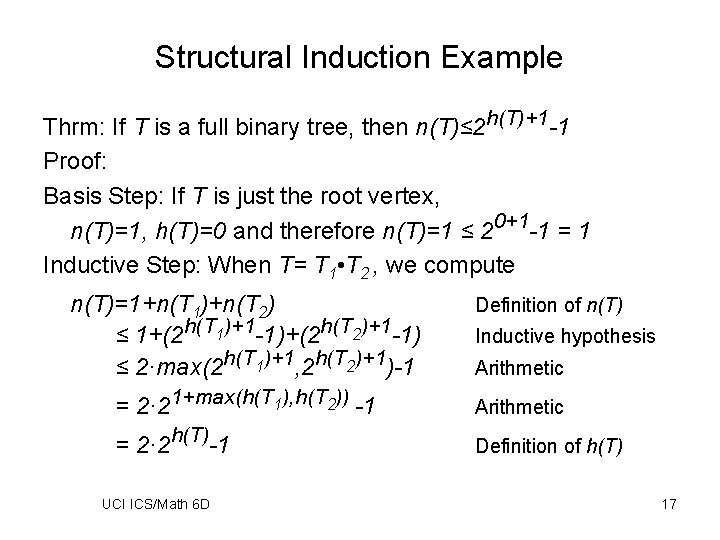

Structural Induction If a set is recursively defined, to show a predicate true for all elements in the set one needs to: (1) Show the predicate true on all base cases; (2) Show that if the predicate is true for each of the elements used to construct a new element, then the same predicate is also true for that new element. E. g. to prove P(T) holds for all T∈FBT, these steps are: (1) showing P(vertex) holds, because base case of FBT definition is just a vertex (2) Showing that if P(T 1) and P(T 2) then P(T 1 • T 2 ), because the recursive clause of FBT definition defines a new FBT as T 1 • T 2. Example: We’ll show that if T is a full binary tree, then n(T) ≤ 2 h(T)+1 -1 (proof on next slide) UCI ICS/Math 6 D 16

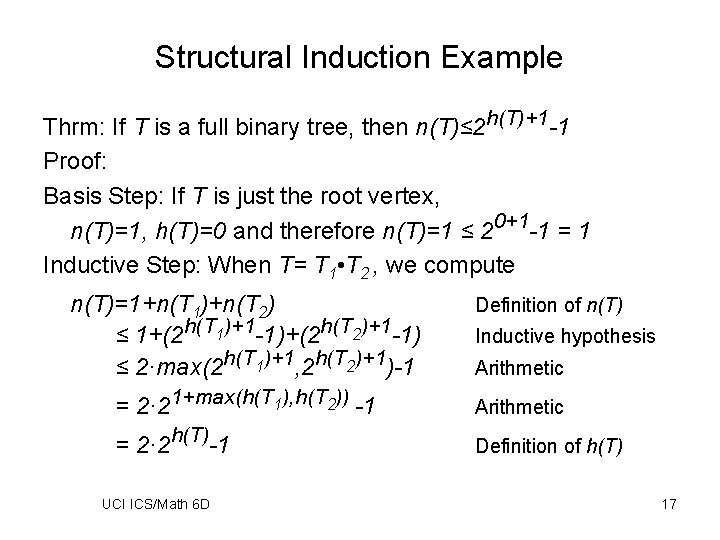

Structural Induction Example Thrm: If T is a full binary tree, then n(T)≤ 2 h(T)+1 -1 Proof: Basis Step: If T is just the root vertex, n(T)=1, h(T)=0 and therefore n(T)=1 ≤ 20+1 -1 = 1 Inductive Step: When T= T 1 • T 2 , we compute n(T)=1+n(T 1)+n(T 2) ≤ 1+(2 h(T 1)+1 -1)+(2 h(T 2)+1 -1) ≤ 2·max(2 h(T 1)+1, 2 h(T 2)+1)-1 Definition of n(T) Inductive hypothesis Arithmetic = 2· 21+max(h(T 1), h(T 2)) -1 Arithmetic = 2· 2 h(T)-1 Definition of h(T) UCI ICS/Math 6 D 17

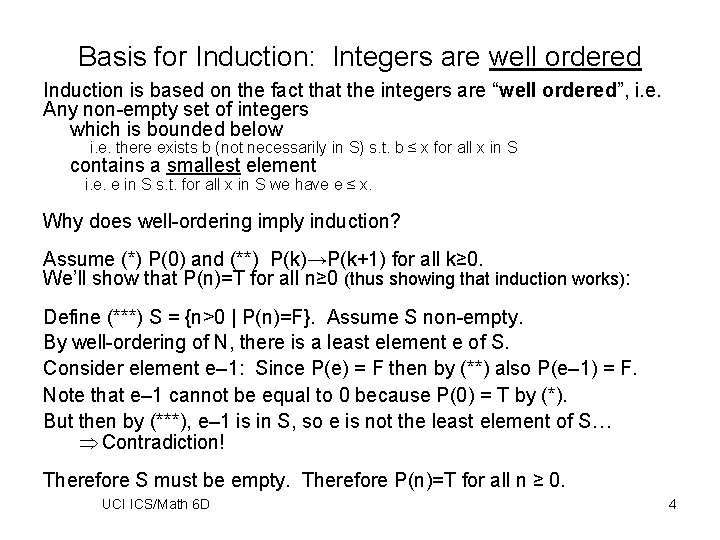

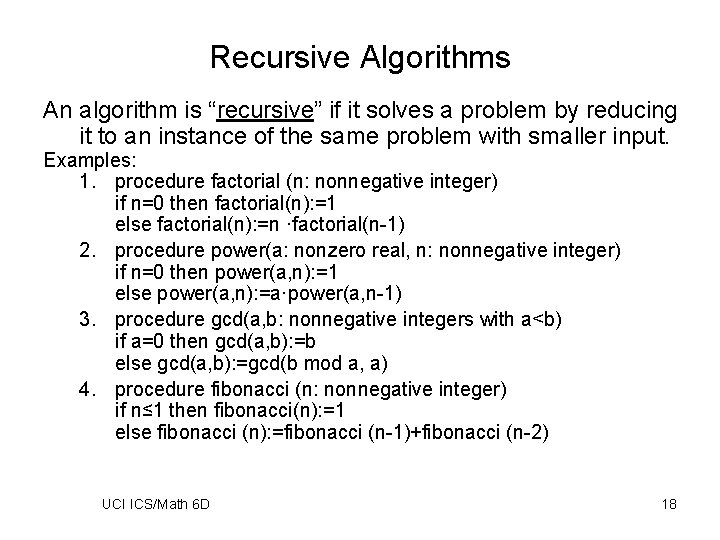

Recursive Algorithms An algorithm is “recursive” if it solves a problem by reducing it to an instance of the same problem with smaller input. Examples: 1. procedure factorial (n: nonnegative integer) if n=0 then factorial(n): =1 else factorial(n): =n ·factorial(n-1) 2. procedure power(a: nonzero real, n: nonnegative integer) if n=0 then power(a, n): =1 else power(a, n): =a·power(a, n-1) 3. procedure gcd(a, b: nonnegative integers with a<b) if a=0 then gcd(a, b): =b else gcd(a, b): =gcd(b mod a, a) 4. procedure fibonacci (n: nonnegative integer) if n≤ 1 then fibonacci(n): =1 else fibonacci (n): =fibonacci (n-1)+fibonacci (n-2) UCI ICS/Math 6 D 18