StorageDevice Hierarchy Rutgers University CS 416 Spring 2008

- Slides: 47

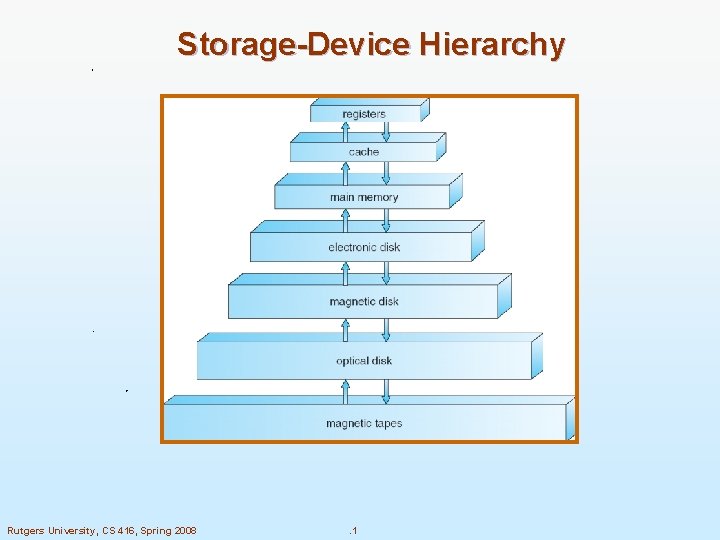

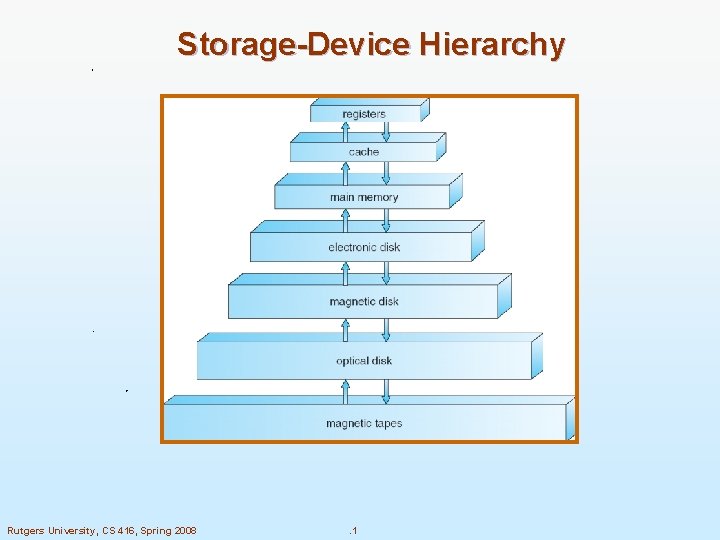

Storage-Device Hierarchy Rutgers University, CS 416, Spring 2008 . 1

Going Down the Hierarchy n. Decreasing cost per bit n. Increasing capacity n. Increasing access time 2 Rutgers University, CS 416, Spring 2008 . 2

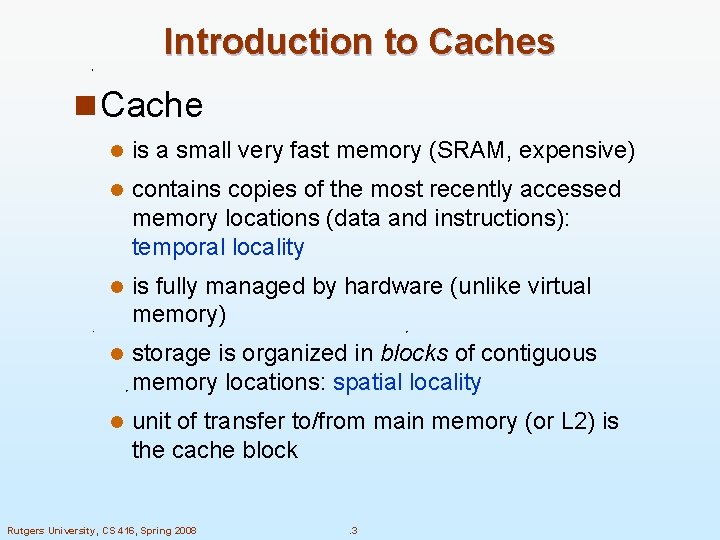

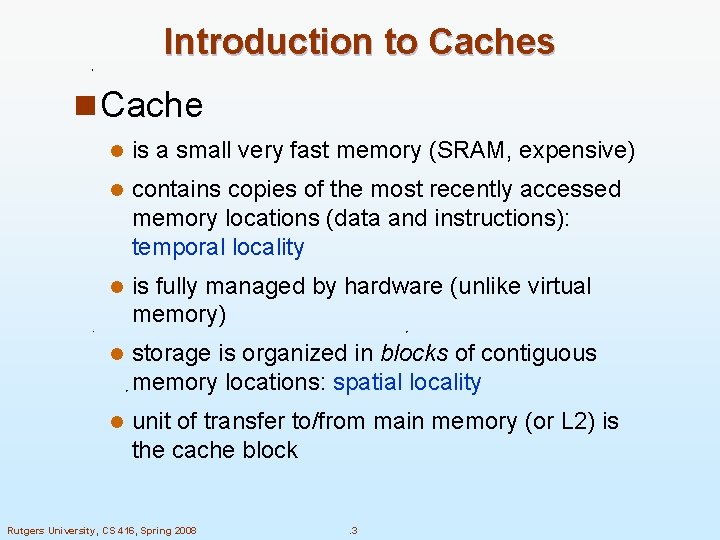

Introduction to Caches n Cache l is a small very fast memory (SRAM, expensive) l contains copies of the most recently accessed memory locations (data and instructions): temporal locality l is fully managed by hardware (unlike virtual memory) l storage is organized in blocks of contiguous memory locations: spatial locality l unit of transfer to/from main memory (or L 2) is the cache block Rutgers University, CS 416, Spring 2008 . 3

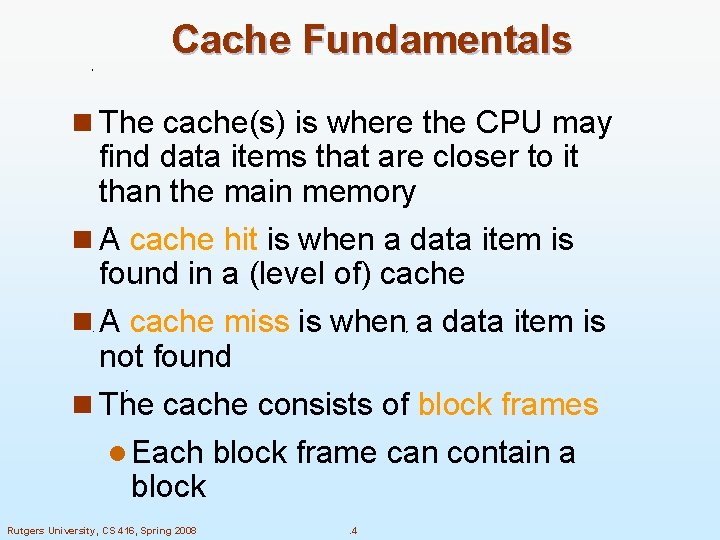

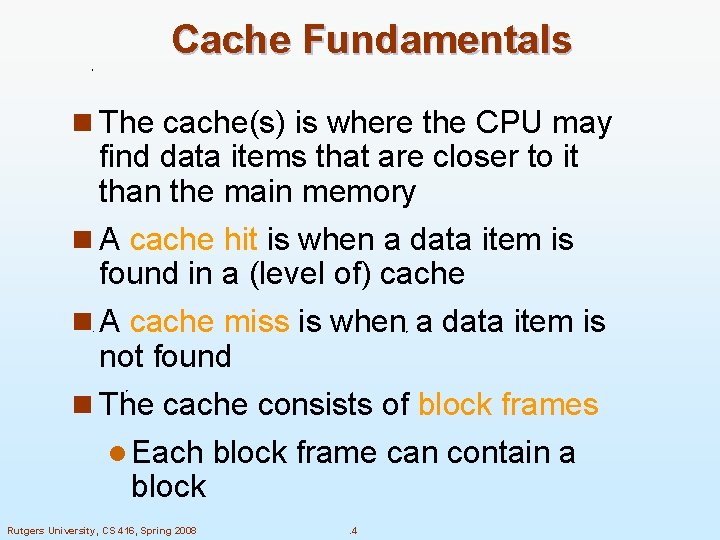

Cache Fundamentals n The cache(s) is where the CPU may find data items that are closer to it than the main memory n A cache hit is when a data item is found in a (level of) cache n A cache miss is when a data item is not found n The cache consists of block frames l Each block frame can contain a block Rutgers University, CS 416, Spring 2008 . 4

Cache Memory n motivated by the mismatch between processor and memory speed n closer to the processor than the main memory n smaller and faster than the main memory n n transfer between caches and main memory is performed in units called cache blocks/lines caches contain also the value of memory locations which are close to locations which were recently accessed (spatial locality) n Physical vs. virtual addressing n Cache performance: miss ratio, miss penalty, average access time n invisible to the OS Rutgers University, CS 416, Spring 2008 . 5

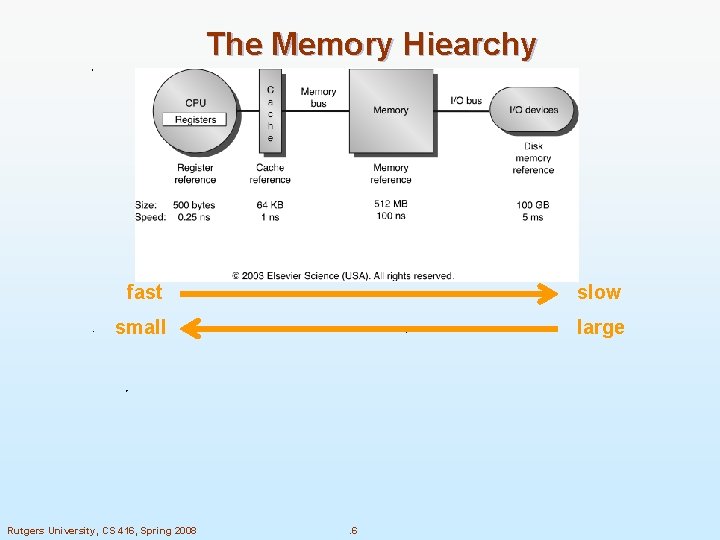

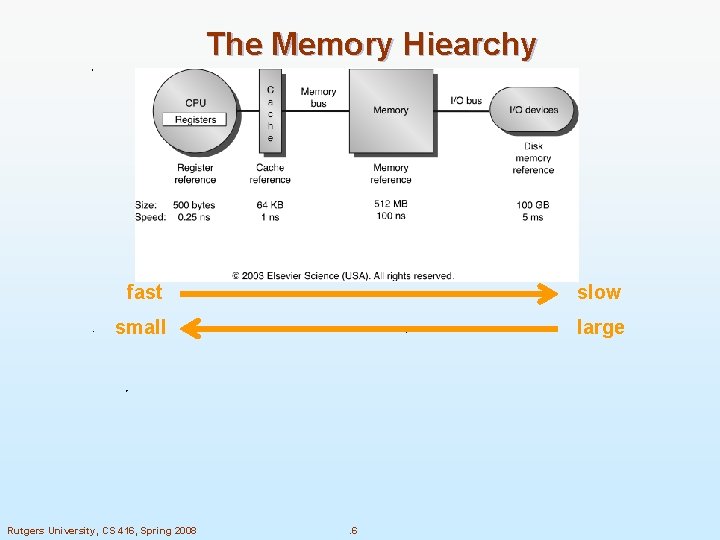

The Memory Hiearchy fast slow small large Rutgers University, CS 416, Spring 2008 . 6

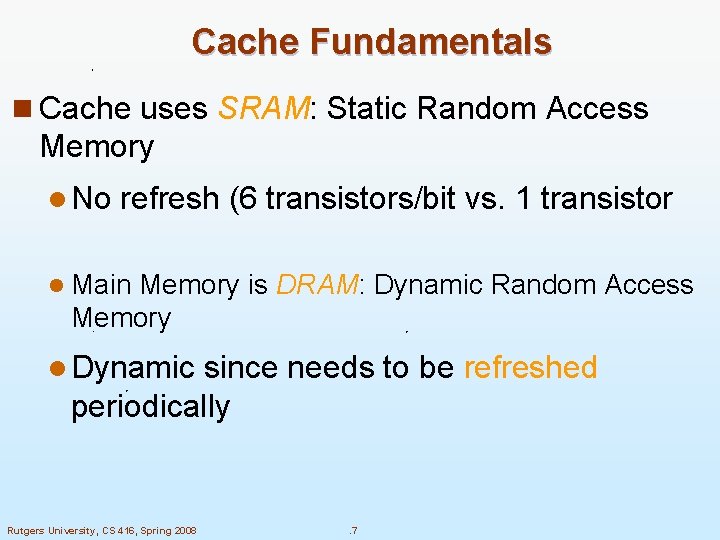

Cache Fundamentals n Cache uses SRAM: Static Random Access Memory l No refresh (6 transistors/bit vs. 1 transistor l Main Memory is DRAM: Dynamic Random Access Memory l Dynamic since needs to be refreshed periodically Rutgers University, CS 416, Spring 2008 . 7

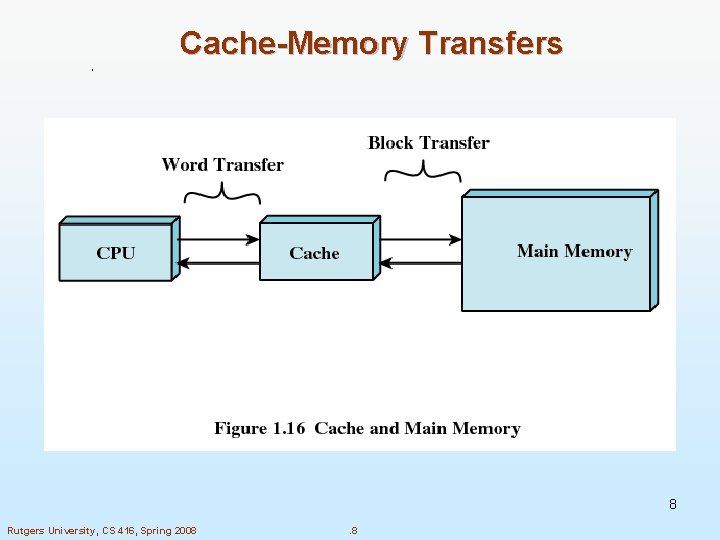

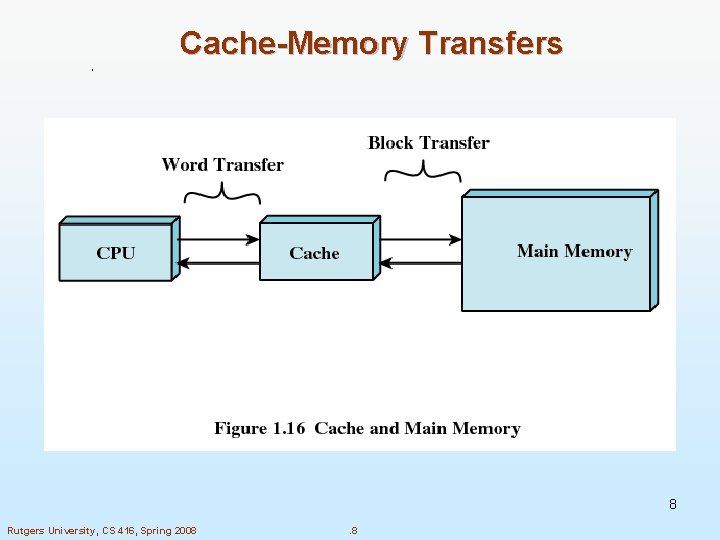

Cache-Memory Transfers 8 Rutgers University, CS 416, Spring 2008 . 8

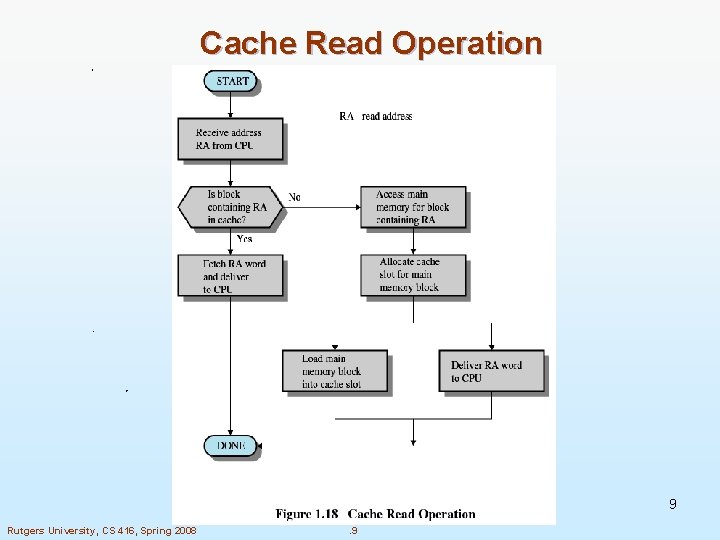

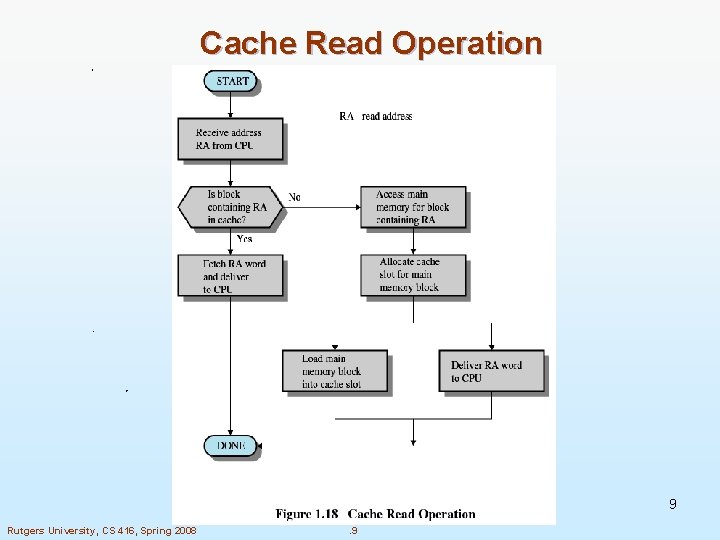

Cache Read Operation 9 Rutgers University, CS 416, Spring 2008 . 9

Types of Memory n Real memory l Main memory n Virtual memory l Memory on disk l Allows for effective multiprogramming and relieves the user of tight constraints of main memory 10 Rutgers University, CS 416, Spring 2008 . 10

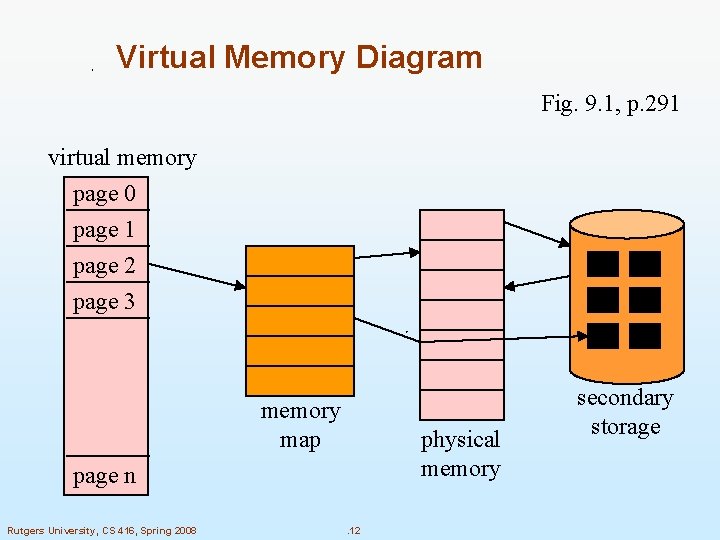

Virtual Memory n Virtual memory – separation of user logical memory from physical memory. l Only part of the program needs to be in memory for execution l Logical address space can therefore be much larger than physical address space l Allows for more efficient process creation n Virtual memory can be implemented via: l Demand paging l Demand segmentation Rutgers University, CS 416, Spring 2008 . 11

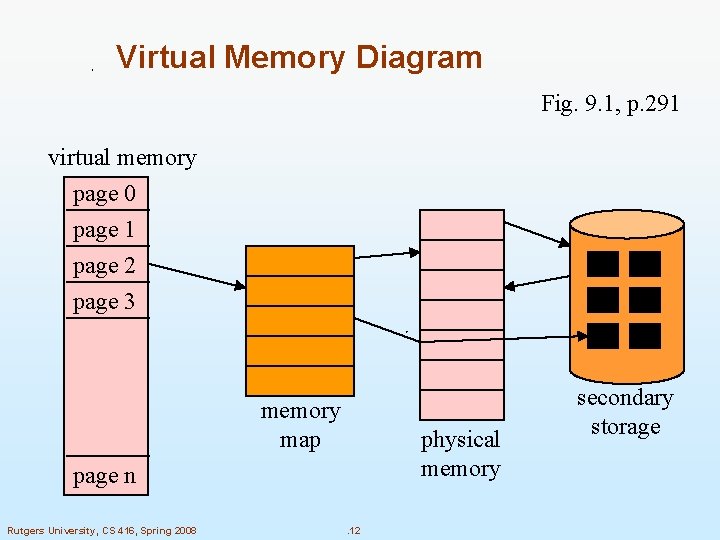

Virtual Memory Diagram Fig. 9. 1, p. 291 virtual memory page 0 page 1 page 2 page 3 memory map physical memory page n Rutgers University, CS 416, Spring 2008 . 12 secondary storage

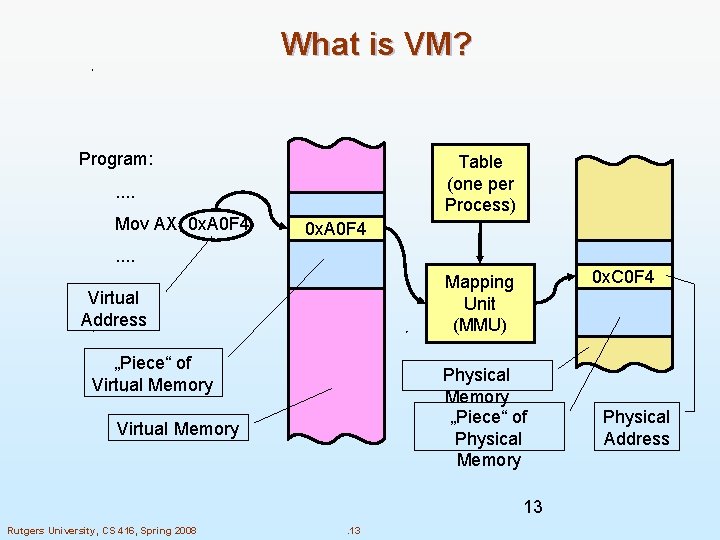

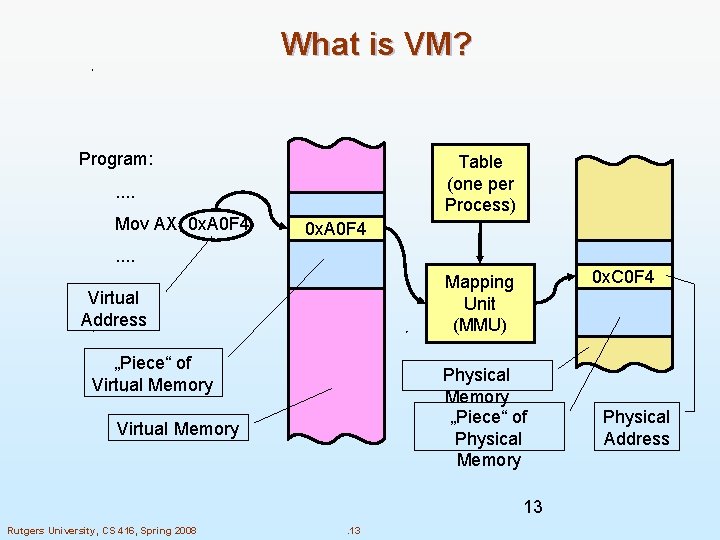

What is VM? Program: Table (one per Process) . . Mov AX, 0 x. A 0 F 4 . . 0 x. C 0 F 4 Mapping Unit (MMU) Virtual Address „Piece“ of Virtual Memory Physical Memory „Piece“ of Physical Memory Virtual Memory 13 Rutgers University, CS 416, Spring 2008 . 13 Physical Address

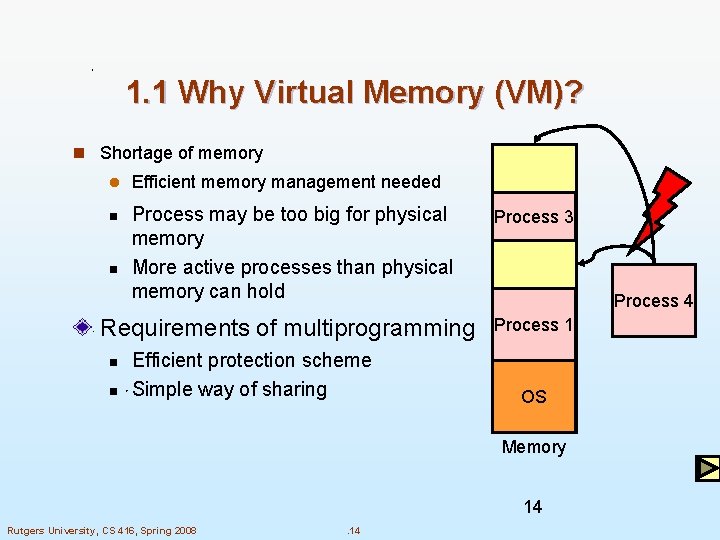

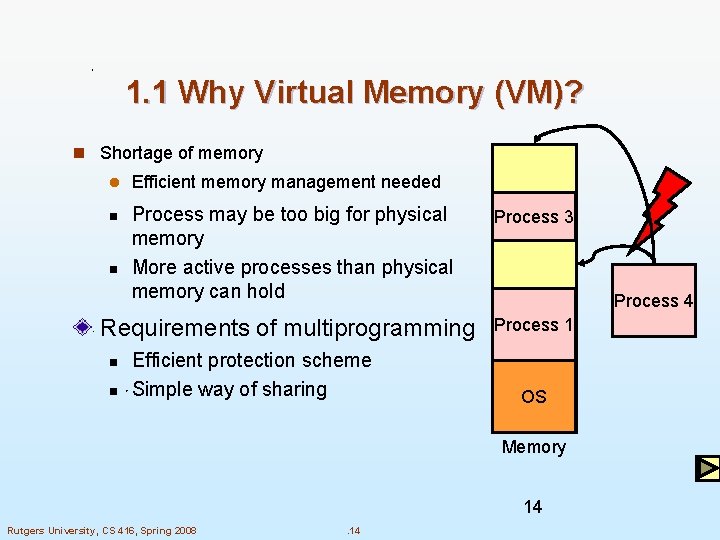

1. 1 Why Virtual Memory (VM)? n Shortage of memory l Efficient memory management needed Process may be too big for physical memory More active processes than physical memory can hold Process 3 Requirements of multiprogramming Process 1 n n Efficient protection scheme Simple way of sharing Process 2 Process 4 OS Memory 14 Rutgers University, CS 416, Spring 2008 . 14

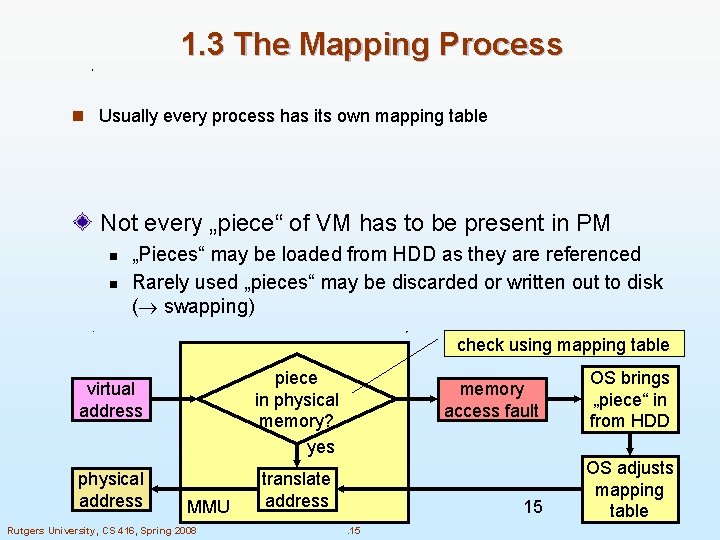

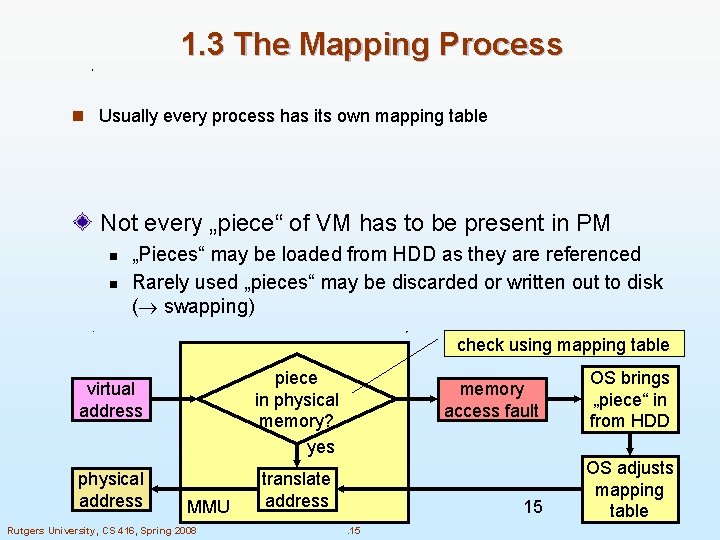

1. 3 The Mapping Process n Usually every process has its own mapping table Not every „piece“ of VM has to be present in PM n n „Pieces“ may be loaded from HDD as they are referenced Rarely used „pieces“ may be discarded or written out to disk ( swapping) check using mapping table piece in physical memory? yes virtual address physical address MMU Rutgers University, CS 416, Spring 2008 memory access fault translate address 15. 15 OS brings „piece“ in from HDD OS adjusts mapping table

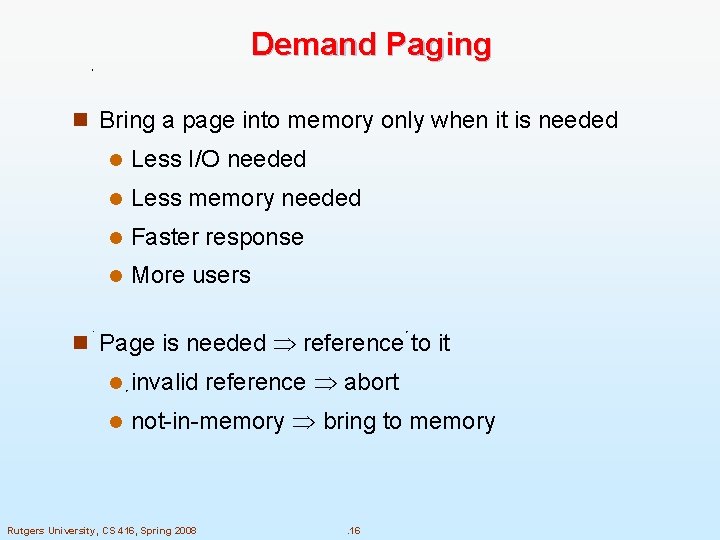

Demand Paging n Bring a page into memory only when it is needed l Less I/O needed l Less memory needed l Faster response l More users n Page is needed reference to it l invalid reference abort l not-in-memory bring to memory Rutgers University, CS 416, Spring 2008 . 16

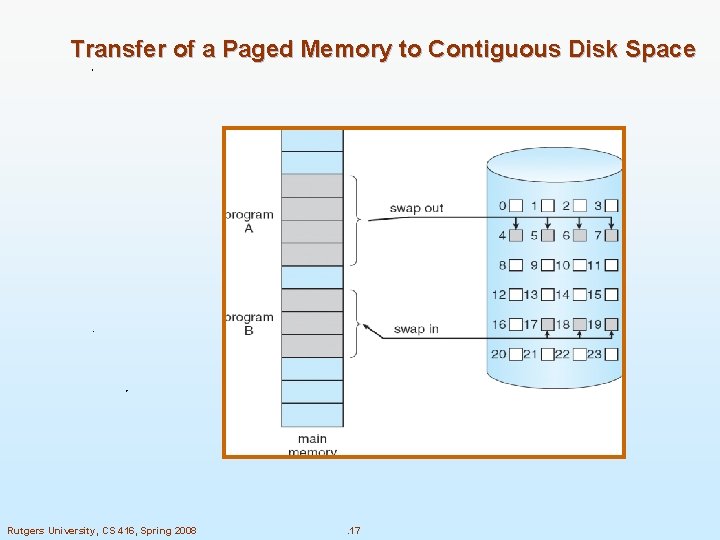

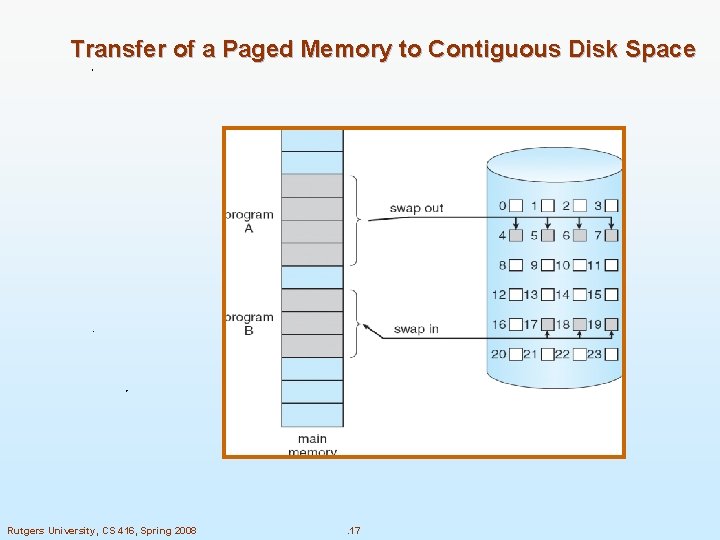

Transfer of a Paged Memory to Contiguous Disk Space Rutgers University, CS 416, Spring 2008 . 17

To replace pages or segments of data in memory. Swapping is a useful technique that enables a computer to execute programs and manipulate data files larger than main memory. When the operating system needs data from the disk, it exchanges a portion of data (called a page or segment ) in main memory with a portion of data on the disk. DOS does not perform swapping, but most other operating systems, including OS/2, Windows, and UNIX, do. Swapping is often called paging. When set of paged data sets moved from auxiliary storage to real storage during execution of any job is called swap-in. Reverse is swap out. Rutgers University, CS 416, Spring 2008 . 18

What is a process n We typically mean that a process is a running program n A better definition is that a process is the state of a running program n Now we have a really good definition of the state of a running program l A program counter l A page table l Register values Rutgers University, CS 416, Spring 2008 . 19

Address Translation Physical Memory CPU @8190 virtual addresses 0 -4095 4096 -8191 8192 -12287 12288 -16384 Process A A. 1 A. 2 A. 3 A. 4 address translation A. 1 B. 1 C. 1 A. 2 C. 4 C. 6 B. 2 B. 3 A. 4 C. 2 C. 3 C. 5. . . Rutgers University, CS 416, Spring 2008 . 20 Disk

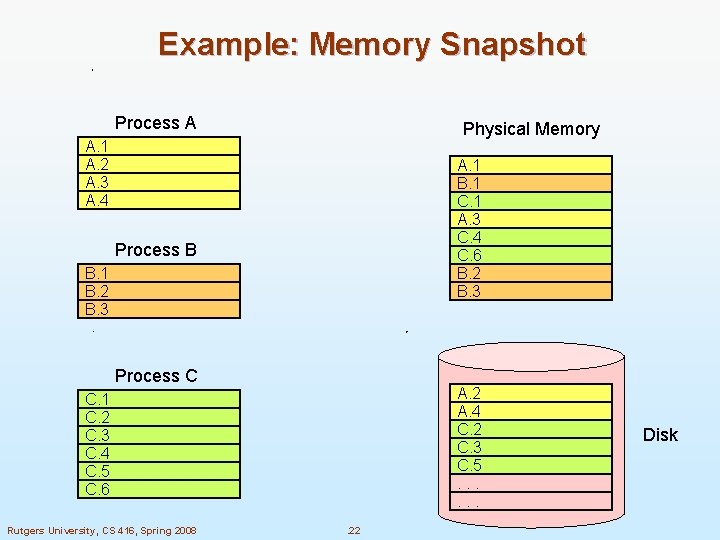

Example Process A Physical Memory A. 1 A. 2 A. 3 A. 4 Process B B. 1 B. 2 B. 3 Process C C. 1 C. 2 C. 3 C. 4 C. 5 C. 6 Rutgers University, CS 416, Spring 2008 Disk . 21

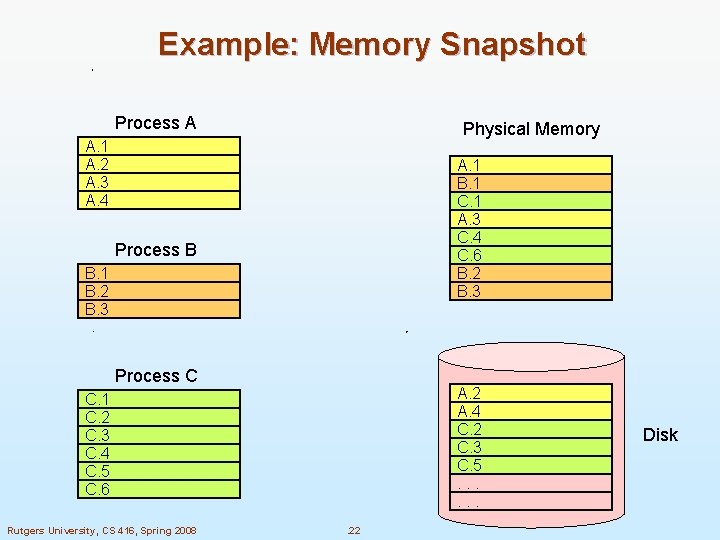

Example: Memory Snapshot Process A Physical Memory A. 1 A. 2 A. 3 A. 4 A. 1 B. 1 C. 1 A. 3 C. 4 C. 6 B. 2 B. 3 Process B B. 1 B. 2 B. 3 Process C A. 2 A. 4 C. 2 C. 3 C. 5. . . C. 1 C. 2 C. 3 C. 4 C. 5 C. 6 Rutgers University, CS 416, Spring 2008 . 22 Disk

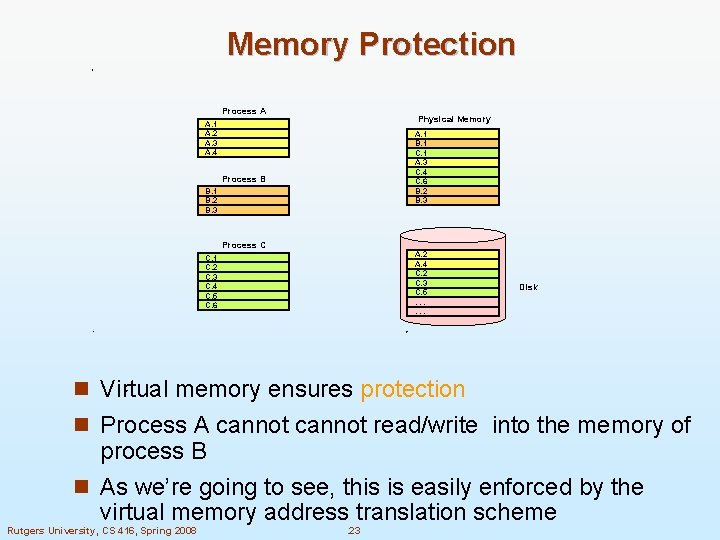

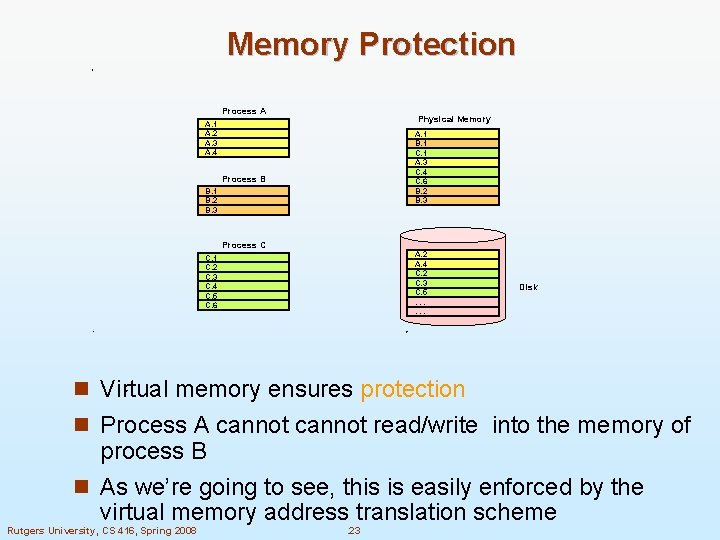

Memory Protection Process A Physical Memory A. 1 A. 2 A. 3 A. 4 A. 1 B. 1 C. 1 A. 3 C. 4 C. 6 B. 2 B. 3 Process B B. 1 B. 2 B. 3 Process C A. 2 A. 4 C. 2 C. 3 C. 5. . . C. 1 C. 2 C. 3 C. 4 C. 5 C. 6 Disk n Virtual memory ensures protection n Process A cannot read/write into the memory of process B n As we’re going to see, this is easily enforced by the virtual memory address translation scheme Rutgers University, CS 416, Spring 2008 . 23

Paging n Each process has its own page table n Each page table entry contains the frame number of the corresponding page in main memory n A bit is needed to indicate whether the page is in main memory or not 24 Rutgers University, CS 416, Spring 2008 . 24

Page Tables n The entire page table may take up too much main memory n Page tables are also stored in virtual memory n When a process is running, part of its page table is in main memory 25 Rutgers University, CS 416, Spring 2008 . 25

Page Size n Smaller page size, less amount of internal fragmentation n Smaller page size, more pages required per process n More pages per process means larger page tables n Larger page tables means large portion of page tables in virtual memory 26 Rutgers University, CS 416, Spring 2008 . 26

Page Faults n A miss in the page table is called a page fault n When the “valid” bit is not set to 1, then the page must be brought in from disk, possibly replacing another page in memory Rutgers University, CS 416, Spring 2008 . 27

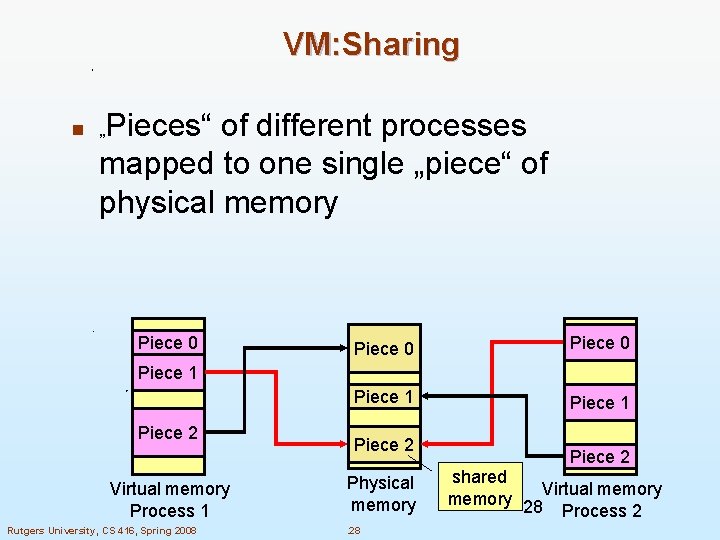

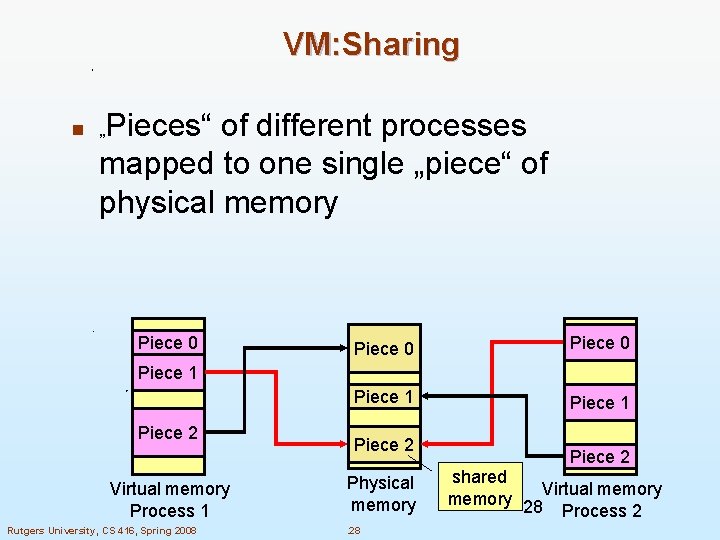

VM: Sharing Pieces“ of different processes mapped to one single „piece“ of physical memory n „ Piece 0 Piece 1 Piece 2 Virtual memory Process 1 Rutgers University, CS 416, Spring 2008 Piece 2 Physical memory. 28 Piece 2 shared Virtual memory 28 Process 2

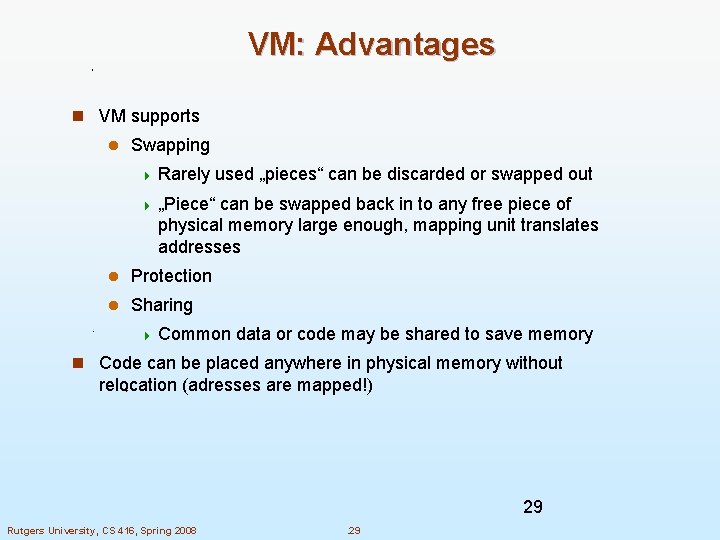

VM: Advantages n VM supports l Swapping 4 Rarely used „pieces“ can be discarded or swapped out 4 „Piece“ can be swapped back in to any free piece of physical memory large enough, mapping unit translates addresses l Protection l Sharing 4 Common data or code may be shared to save memory n Code can be placed anywhere in physical memory without relocation (adresses are mapped!) 29 Rutgers University, CS 416, Spring 2008 . 29

VM: Disadvantages n Memory requirements (mapping tables) n Longer memory access times (mapping table lookup) 30 Rutgers University, CS 416, Spring 2008 . 30

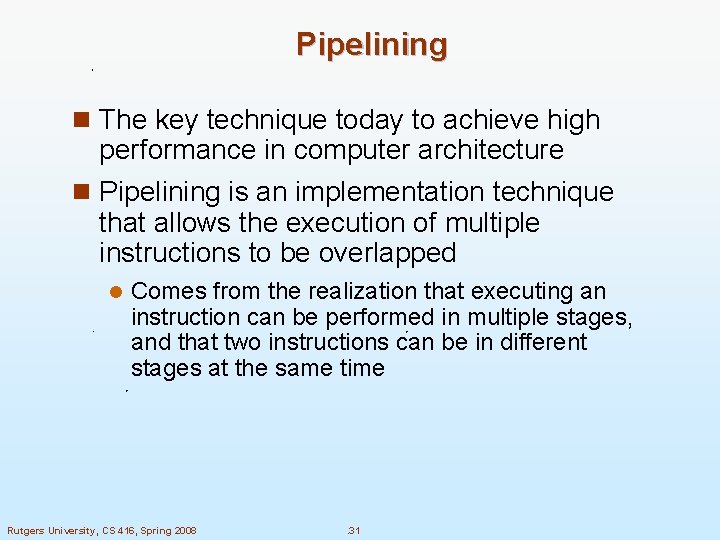

Pipelining n The key technique today to achieve high performance in computer architecture n Pipelining is an implementation technique that allows the execution of multiple instructions to be overlapped l Comes from the realization that executing an instruction can be performed in multiple stages, and that two instructions can be in different stages at the same time Rutgers University, CS 416, Spring 2008 . 31

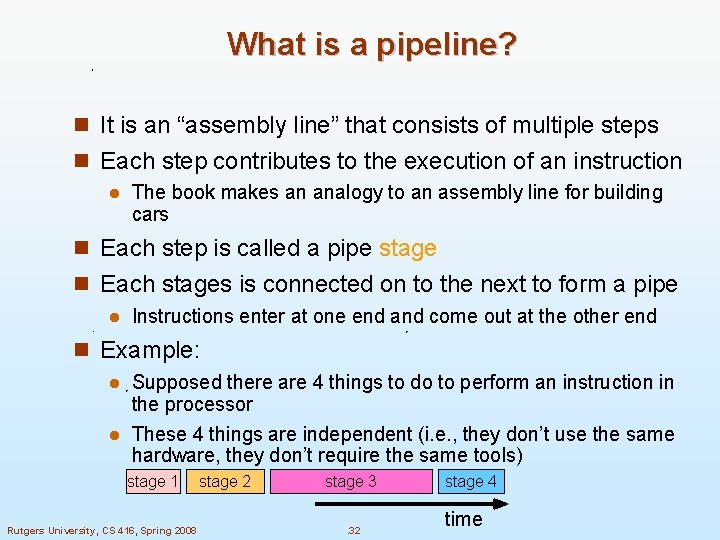

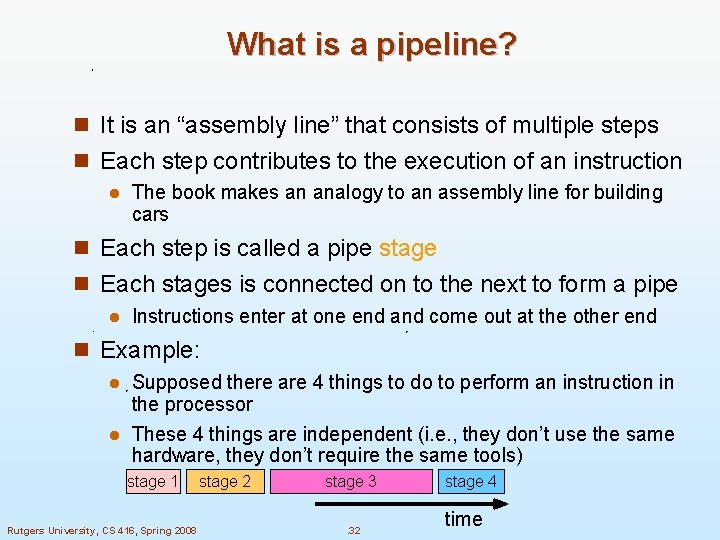

What is a pipeline? n It is an “assembly line” that consists of multiple steps n Each step contributes to the execution of an instruction l The book makes an analogy to an assembly line for building cars n Each step is called a pipe stage n Each stages is connected on to the next to form a pipe l Instructions enter at one end and come out at the other end n Example: Supposed there are 4 things to do to perform an instruction in the processor l These 4 things are independent (i. e. , they don’t use the same hardware, they don’t require the same tools) l stage 1 Rutgers University, CS 416, Spring 2008 stage 2 stage 3. 32 stage 4 time

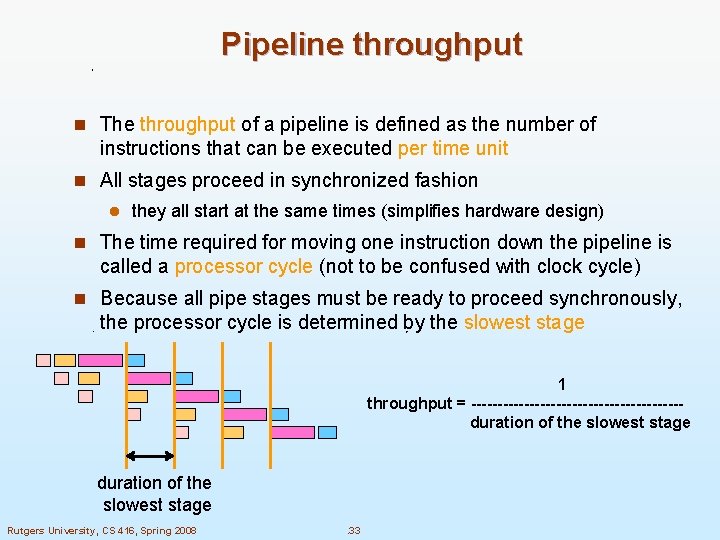

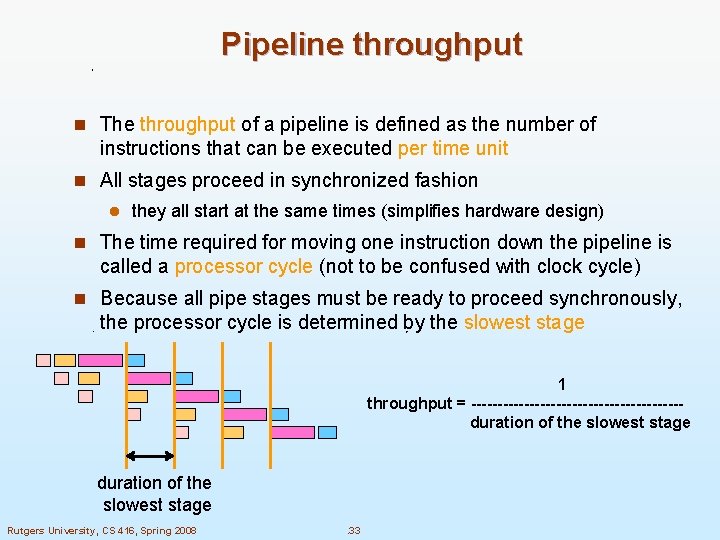

Pipeline throughput n The throughput of a pipeline is defined as the number of instructions that can be executed per time unit n All stages proceed in synchronized fashion l they all start at the same times (simplifies hardware design) n The time required for moving one instruction down the pipeline is called a processor cycle (not to be confused with clock cycle) n Because all pipe stages must be ready to proceed synchronously, the processor cycle is determined by the slowest stage 1 throughput = --------------------duration of the slowest stage Rutgers University, CS 416, Spring 2008 . 33

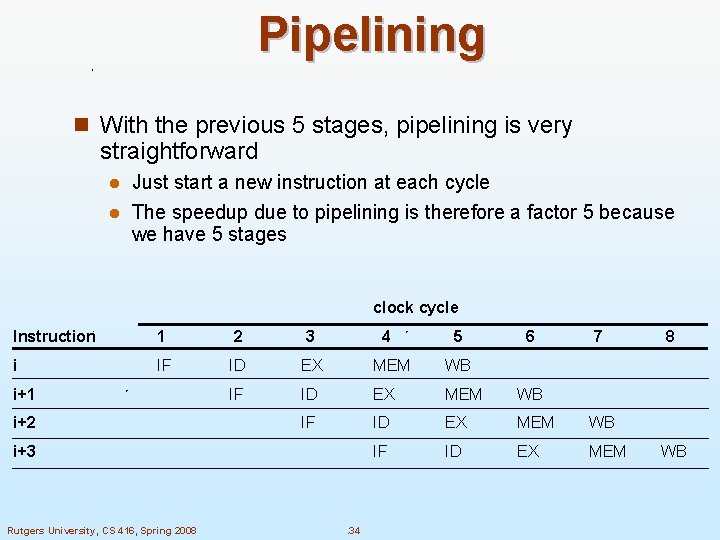

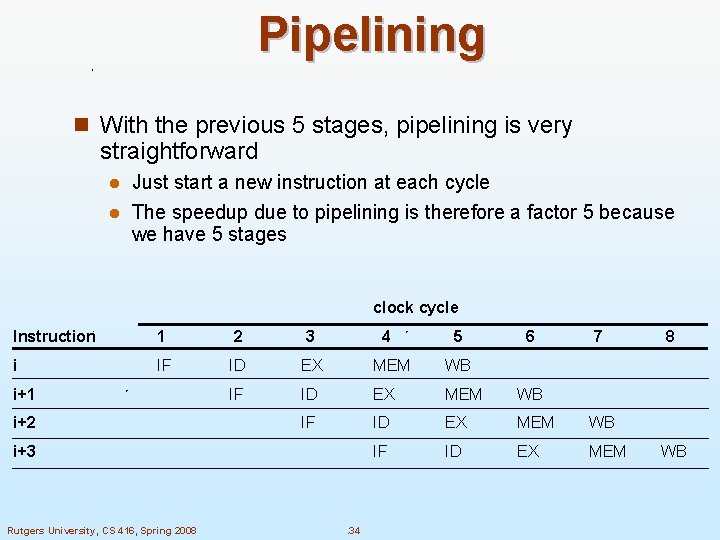

Pipelining n With the previous 5 stages, pipelining is very straightforward Just start a new instruction at each cycle l The speedup due to pipelining is therefore a factor 5 because we have 5 stages l clock cycle Instruction 1 2 3 i IF ID EX MEM WB IF ID EX MEM i+1 i+2 4 i+3 Rutgers University, CS 416, Spring 2008 . 34 5 6 7 8 WB

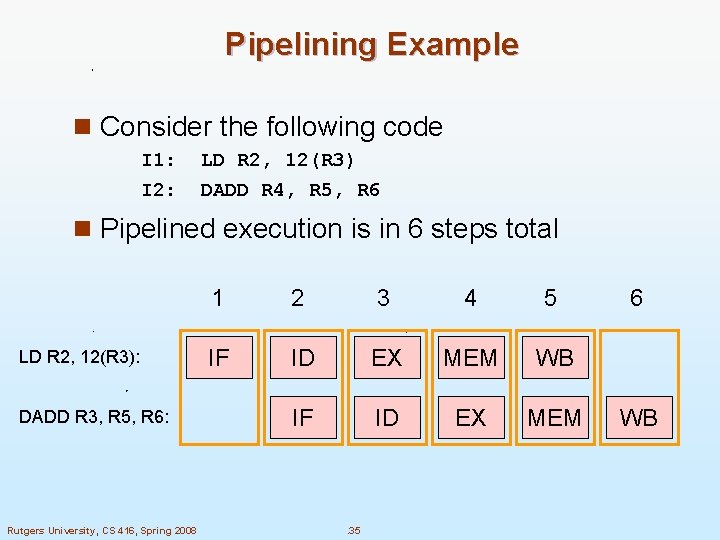

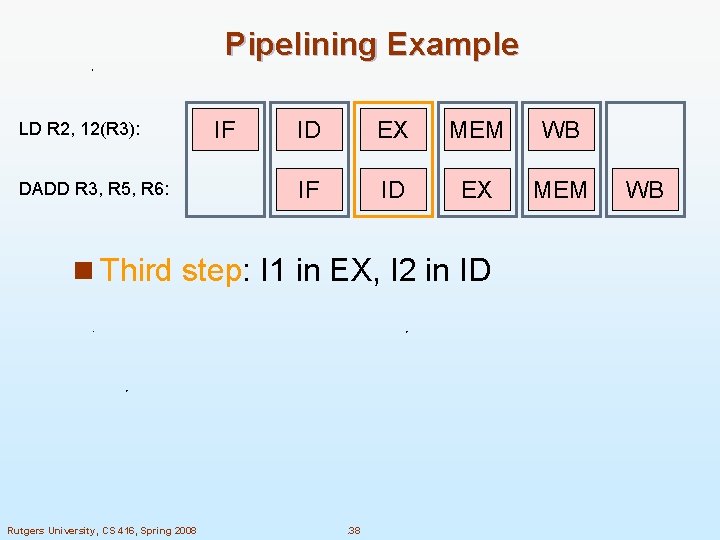

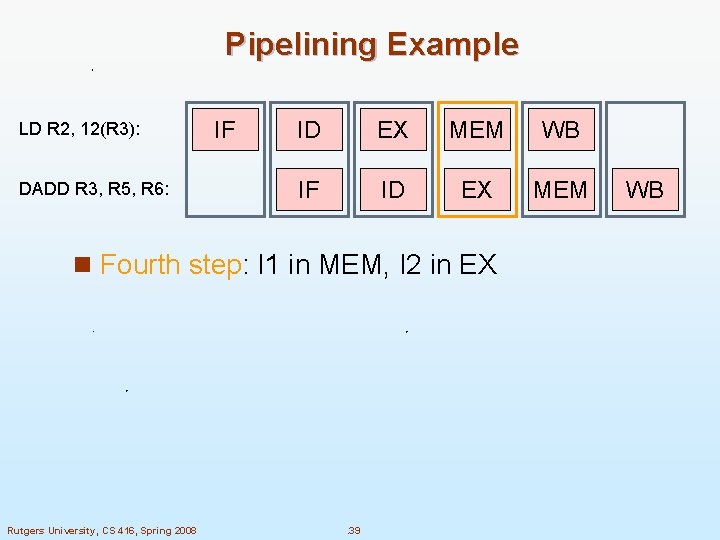

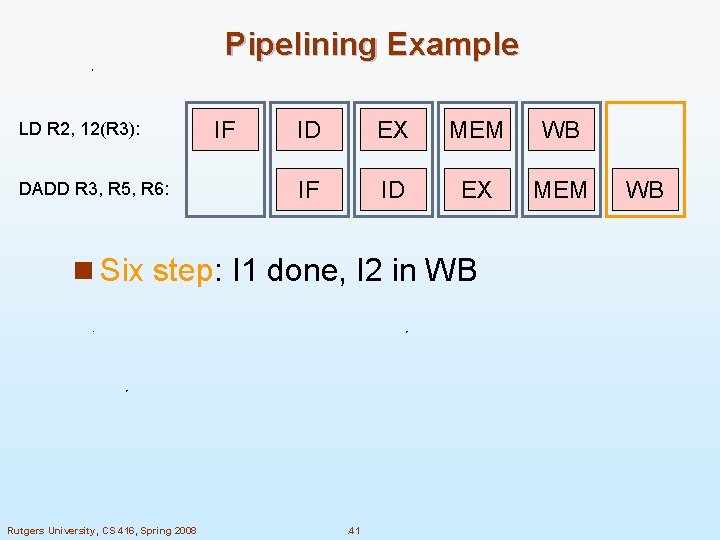

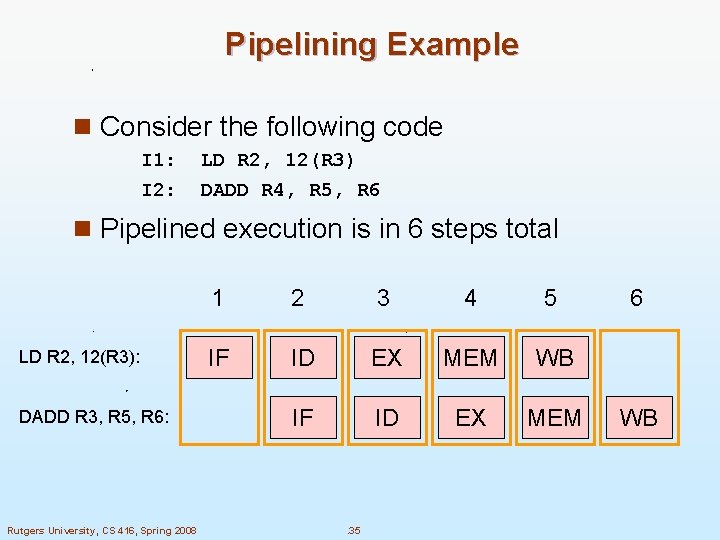

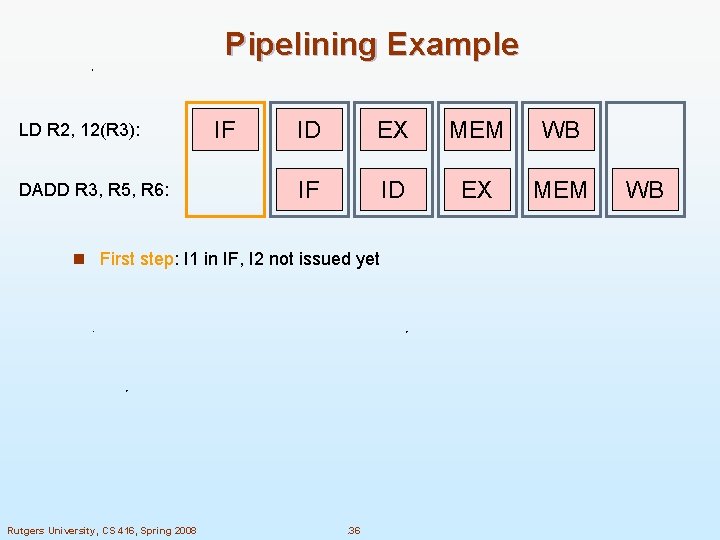

Pipelining Example n Consider the following code I 1: I 2: LD R 2, 12(R 3) DADD R 4, R 5, R 6 n Pipelined execution is in 6 steps total LD R 2, 12(R 3): DADD R 3, R 5, R 6: Rutgers University, CS 416, Spring 2008 1 2 3 4 5 IF ID EX MEM WB IF ID EX MEM . 35 6 WB

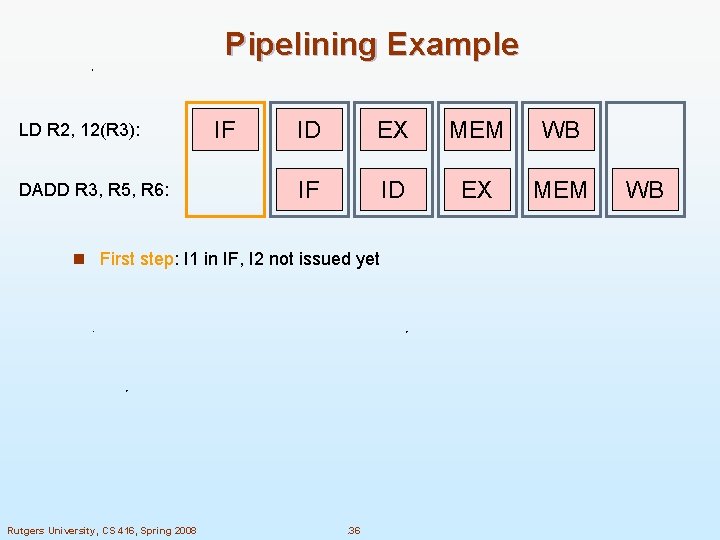

Pipelining Example LD R 2, 12(R 3): DADD R 3, R 5, R 6: IF ID EX MEM WB IF ID EX MEM n First step: I 1 in IF, I 2 not issued yet Rutgers University, CS 416, Spring 2008 . 36 WB

Pipelining Example LD R 2, 12(R 3): DADD R 3, R 5, R 6: IF ID EX MEM WB IF ID EX MEM n Second step: I 1 in ID, I 2 in IF Rutgers University, CS 416, Spring 2008 . 37 WB

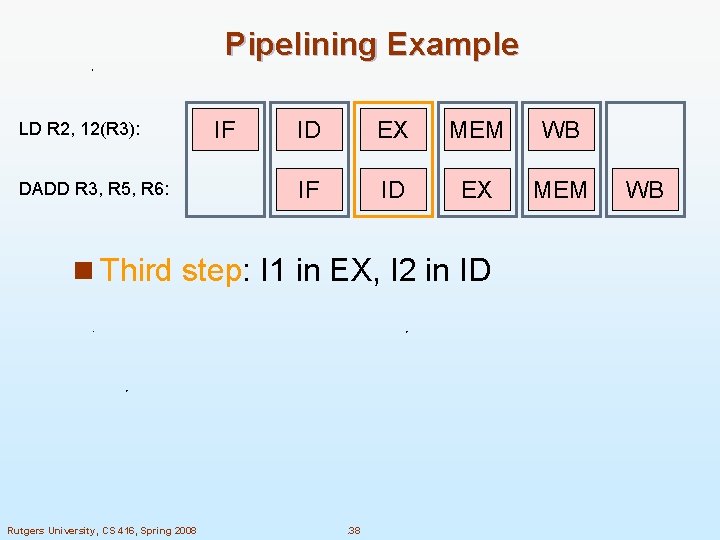

Pipelining Example LD R 2, 12(R 3): DADD R 3, R 5, R 6: IF ID EX MEM WB IF ID EX MEM n Third step: I 1 in EX, I 2 in ID Rutgers University, CS 416, Spring 2008 . 38 WB

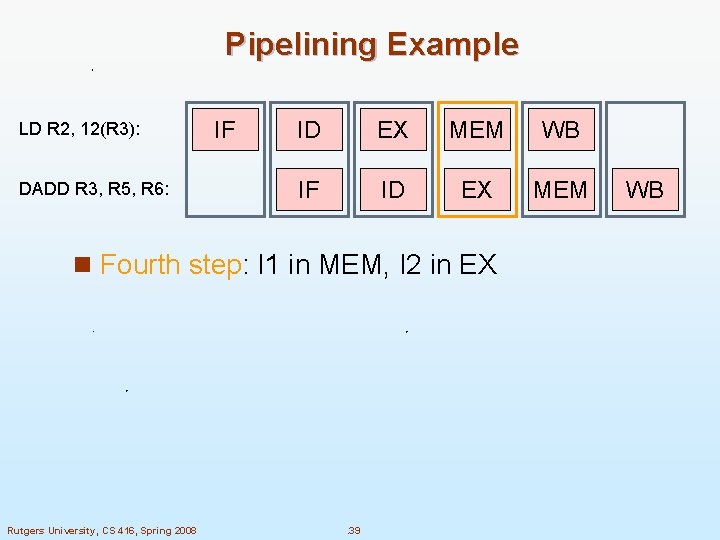

Pipelining Example LD R 2, 12(R 3): DADD R 3, R 5, R 6: IF ID EX MEM WB IF ID EX MEM n Fourth step: I 1 in MEM, I 2 in EX Rutgers University, CS 416, Spring 2008 . 39 WB

Pipelining Example LD R 2, 12(R 3): DADD R 3, R 5, R 6: IF ID EX MEM WB IF ID EX MEM n Fifth step: I 1 in WB, I 2 in MEM Rutgers University, CS 416, Spring 2008 . 40 WB

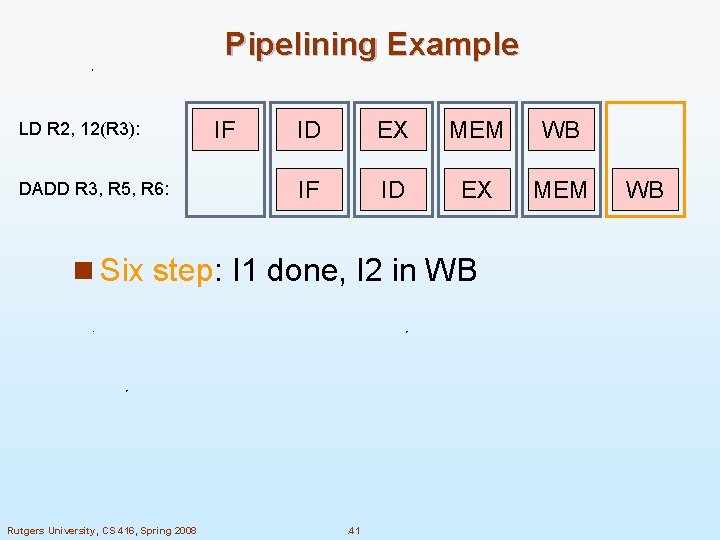

Pipelining Example LD R 2, 12(R 3): DADD R 3, R 5, R 6: IF ID EX MEM WB IF ID EX MEM n Six step: I 1 done, I 2 in WB Rutgers University, CS 416, Spring 2008 . 41 WB

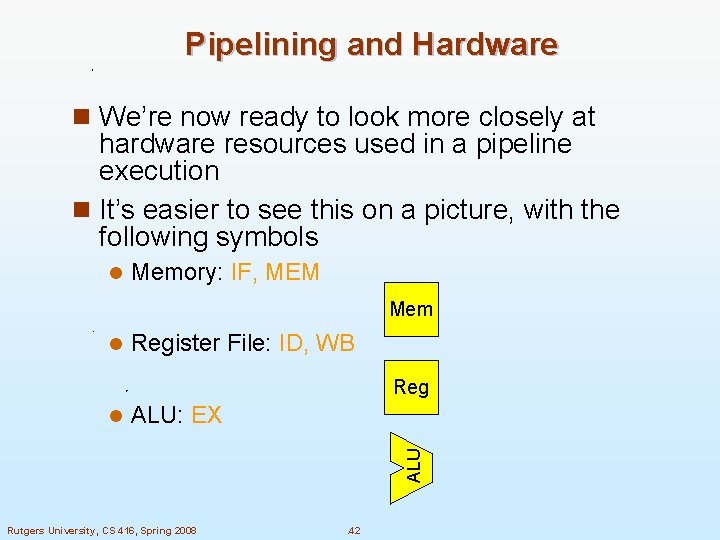

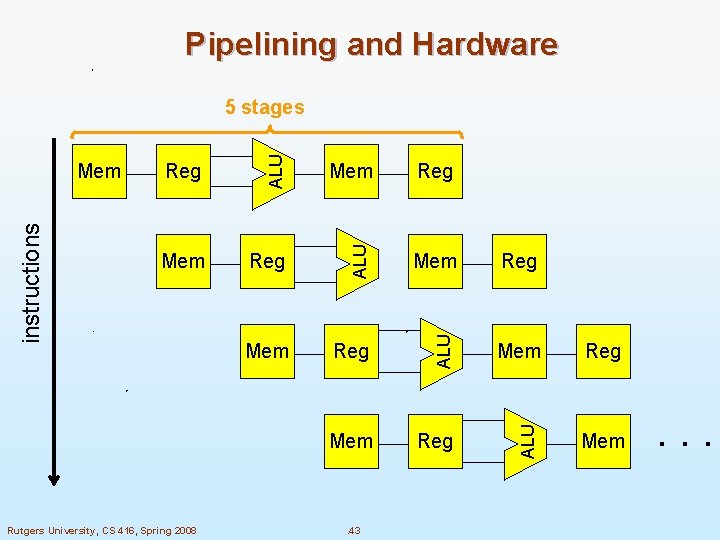

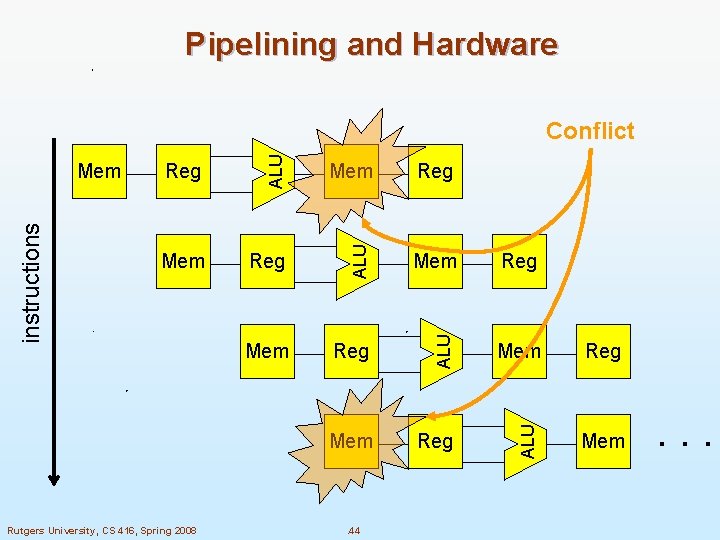

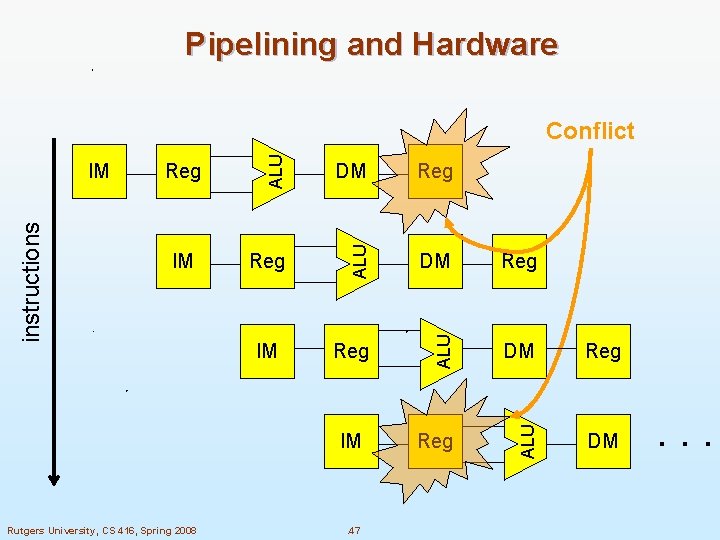

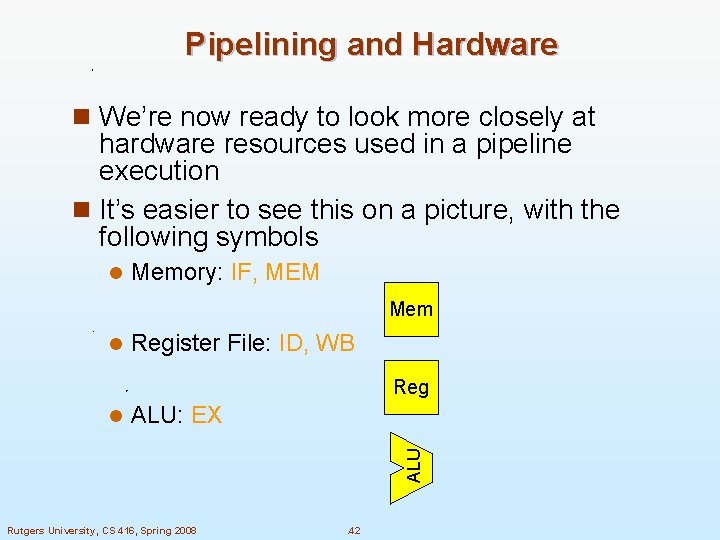

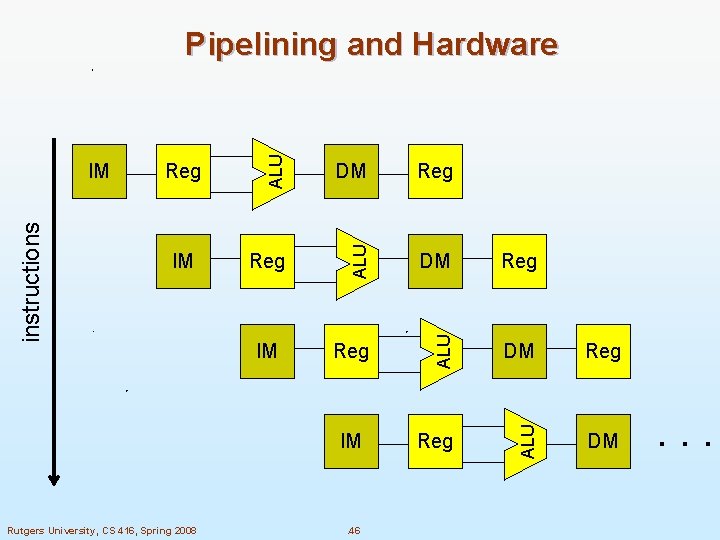

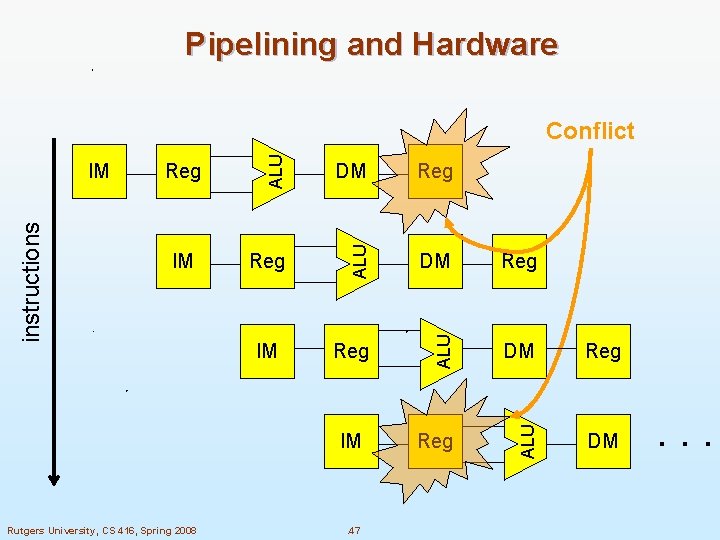

Pipelining and Hardware n We’re now ready to look more closely at hardware resources used in a pipeline execution n It’s easier to see this on a picture, with the following symbols l Memory: IF, MEM Mem l Register File: ID, WB Reg ALU: EX ALU l Rutgers University, CS 416, Spring 2008 . 42

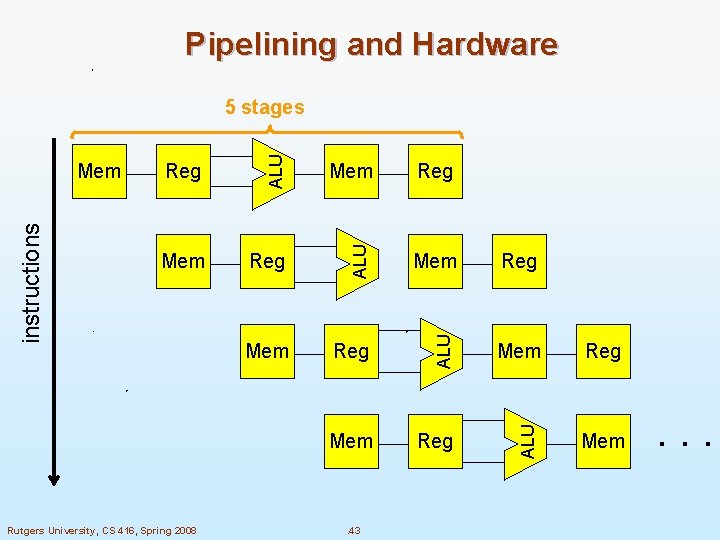

Pipelining and Hardware Rutgers University, CS 416, Spring 2008 Reg Mem Reg ALU Mem ALU Reg ALU instructions Mem ALU 5 stages Mem . 43 . . .

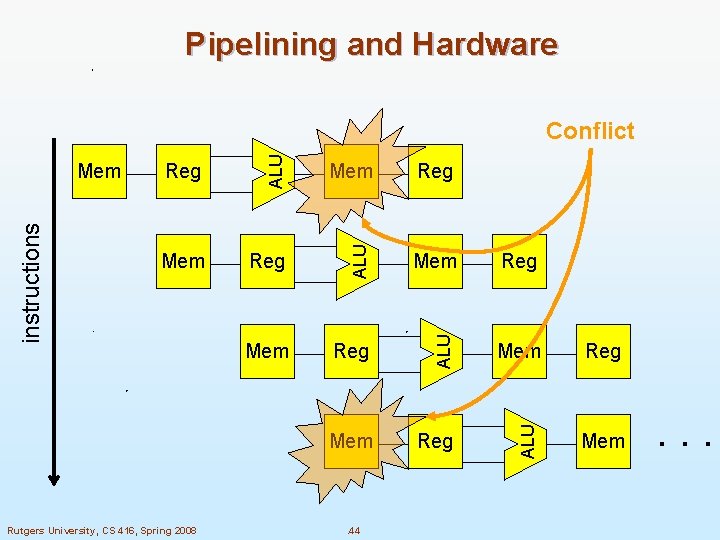

Pipelining and Hardware Rutgers University, CS 416, Spring 2008 Reg Mem Reg ALU Mem ALU Reg ALU instructions Mem ALU Conflict Mem . 44 . . .

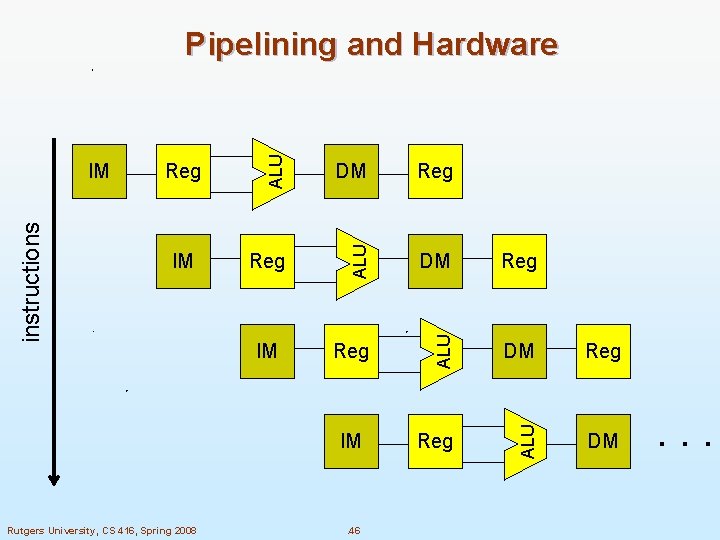

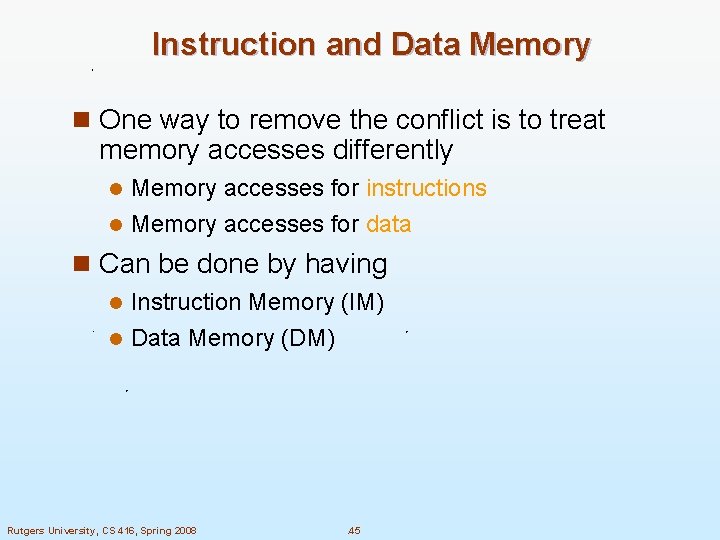

Instruction and Data Memory n One way to remove the conflict is to treat memory accesses differently Memory accesses for instructions l Memory accesses for data l n Can be done by having Instruction Memory (IM) l Data Memory (DM) l Rutgers University, CS 416, Spring 2008 . 45

Reg Reg DM Reg ALU IM DM ALU Reg ALU instructions IM ALU Pipelining and Hardware DM IM IM Rutgers University, CS 416, Spring 2008 . 46 . . .

Pipelining and Hardware Reg Reg DM Reg ALU IM DM ALU Reg ALU instructions IM ALU Conflict DM IM IM Rutgers University, CS 416, Spring 2008 . 47 . . .